Comparing Microstructure and Corrosion Performance of Laser Powder Bed Fusion 316L Stainless Steel Reinforced with Varied Ceramic Particles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

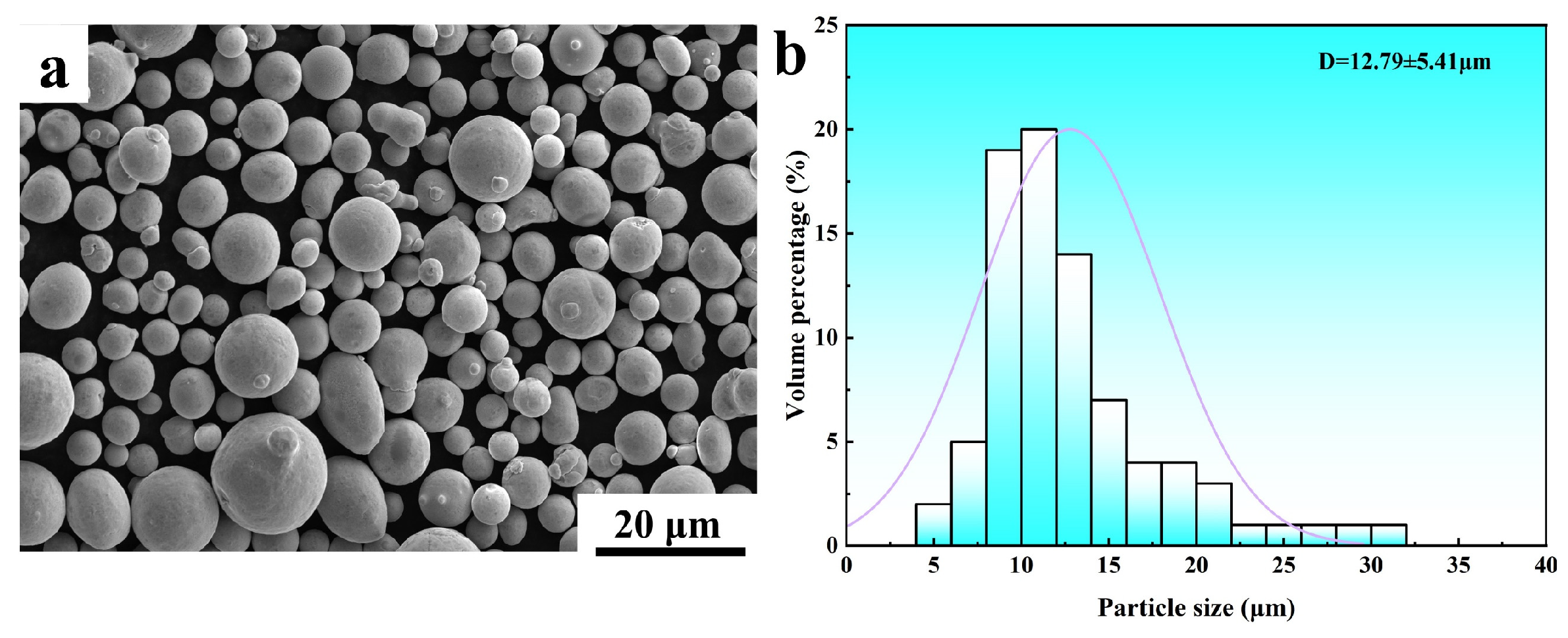

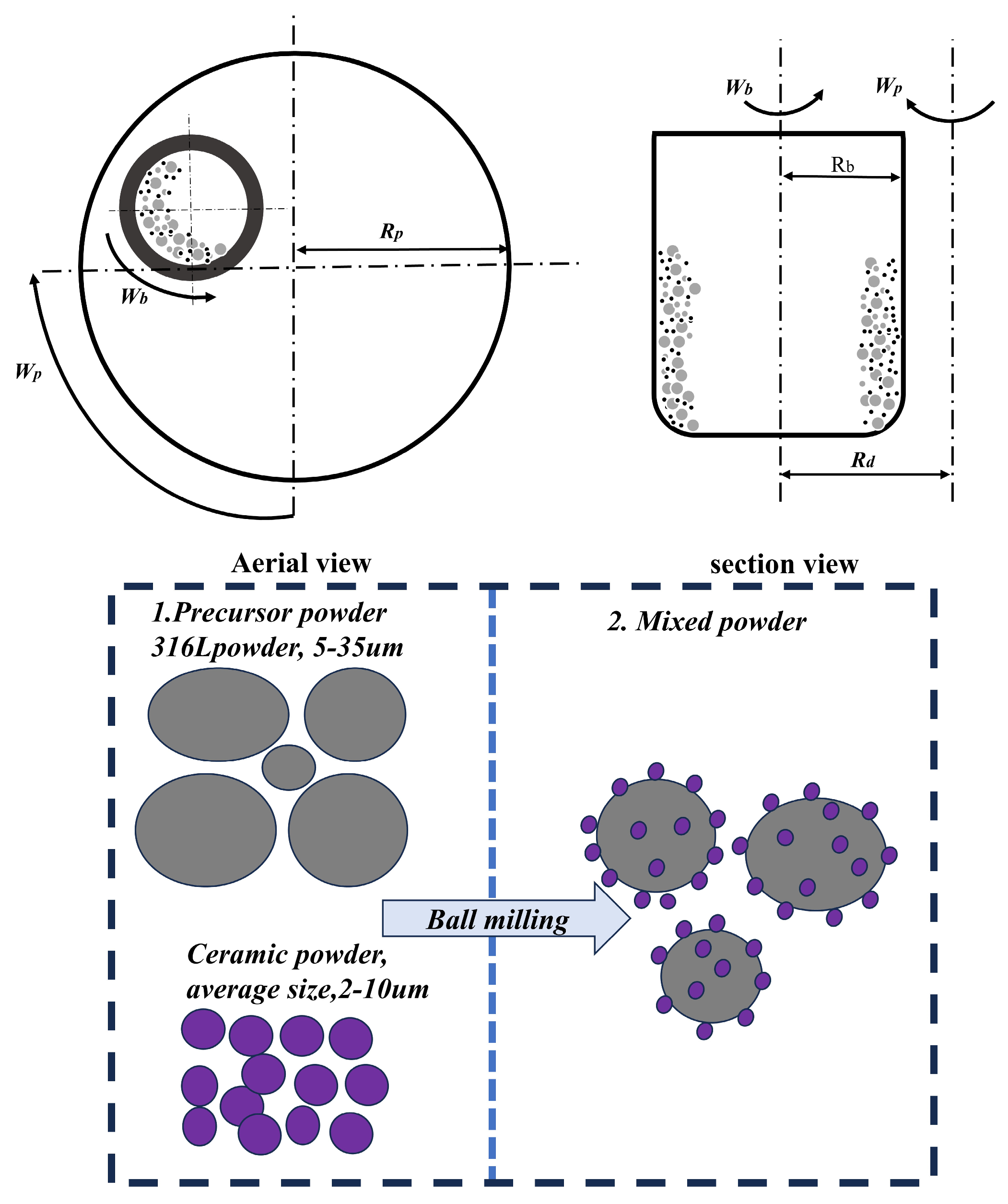

2.1. Preparation of Materials

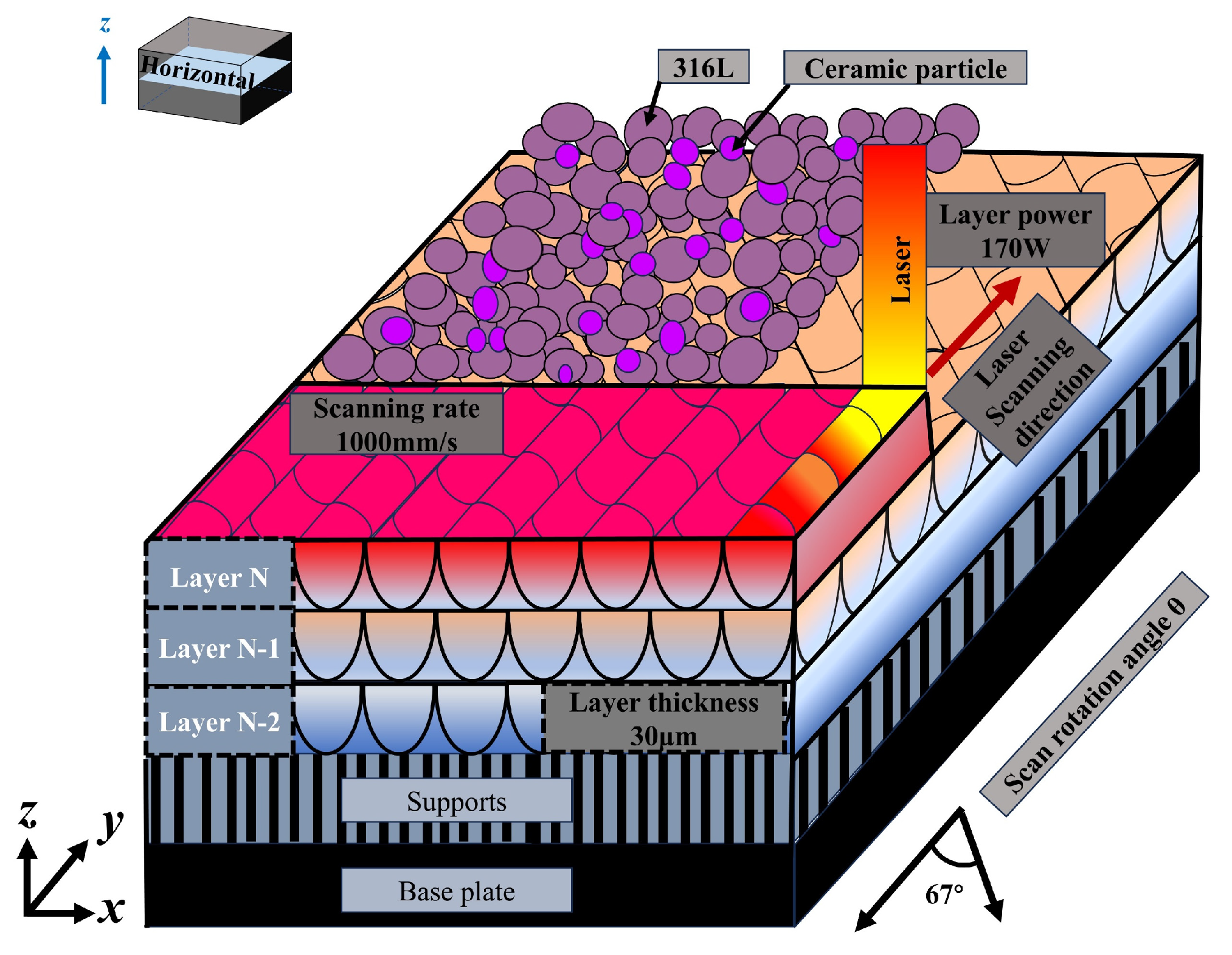

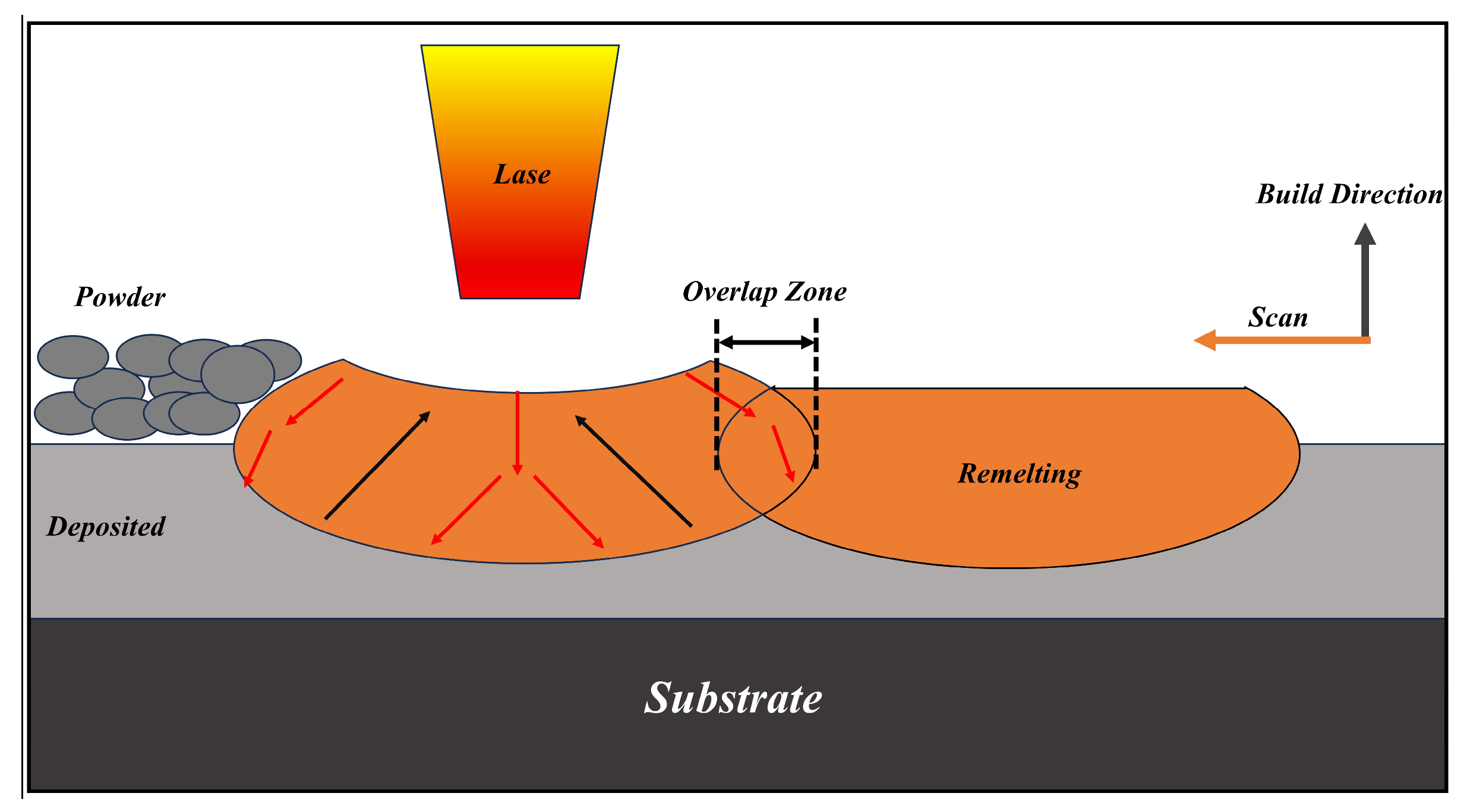

2.2. Laser Powder Bed Fusion Technology

2.3. Porosity and Microstructural Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Measurement

3. Results and Discussion

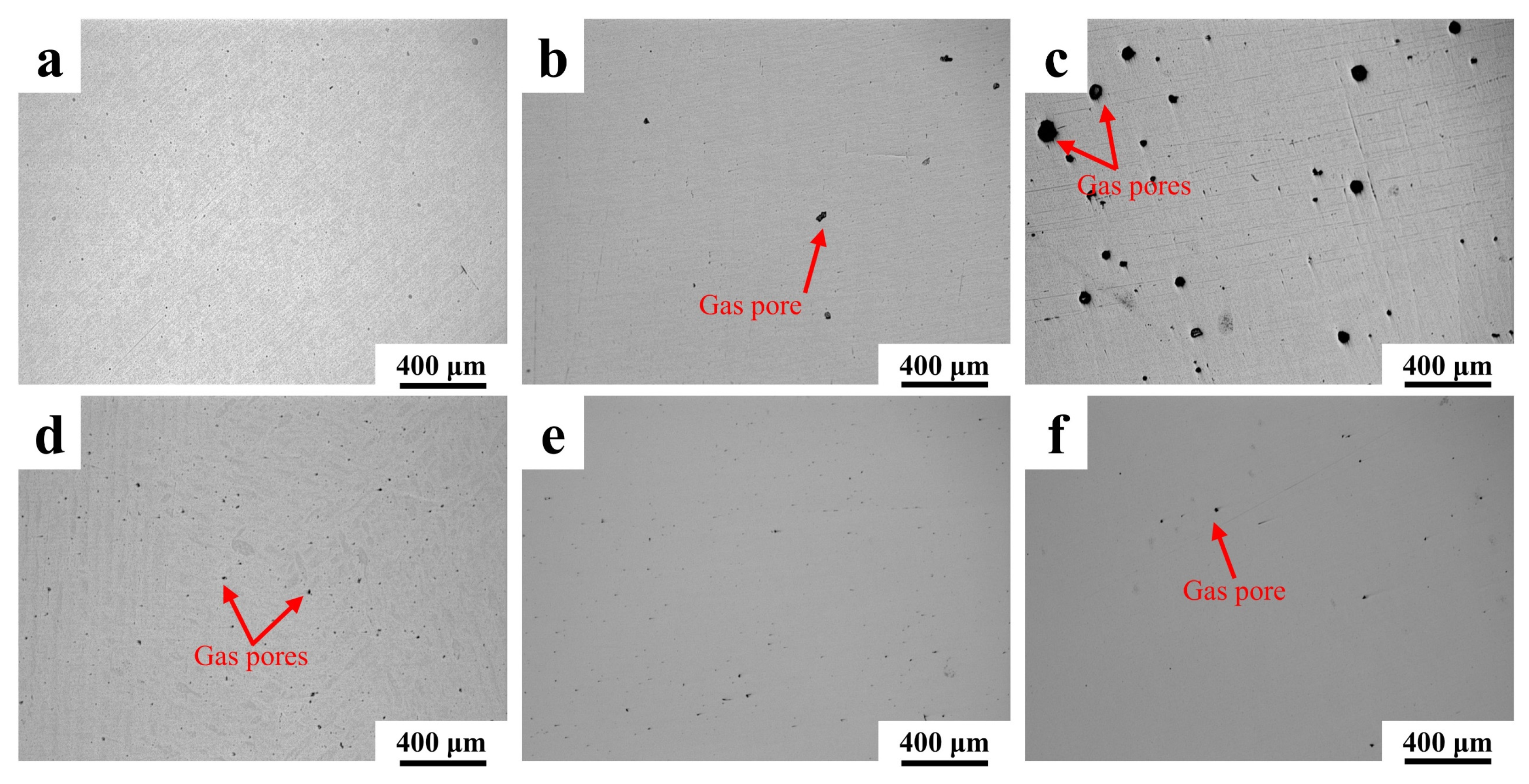

3.1. Porosity of 316L Stainless Steel with Different Ceramic Particles

3.2. Phase Analysis

3.3. Microstructure

3.4. Electrochemical Testing

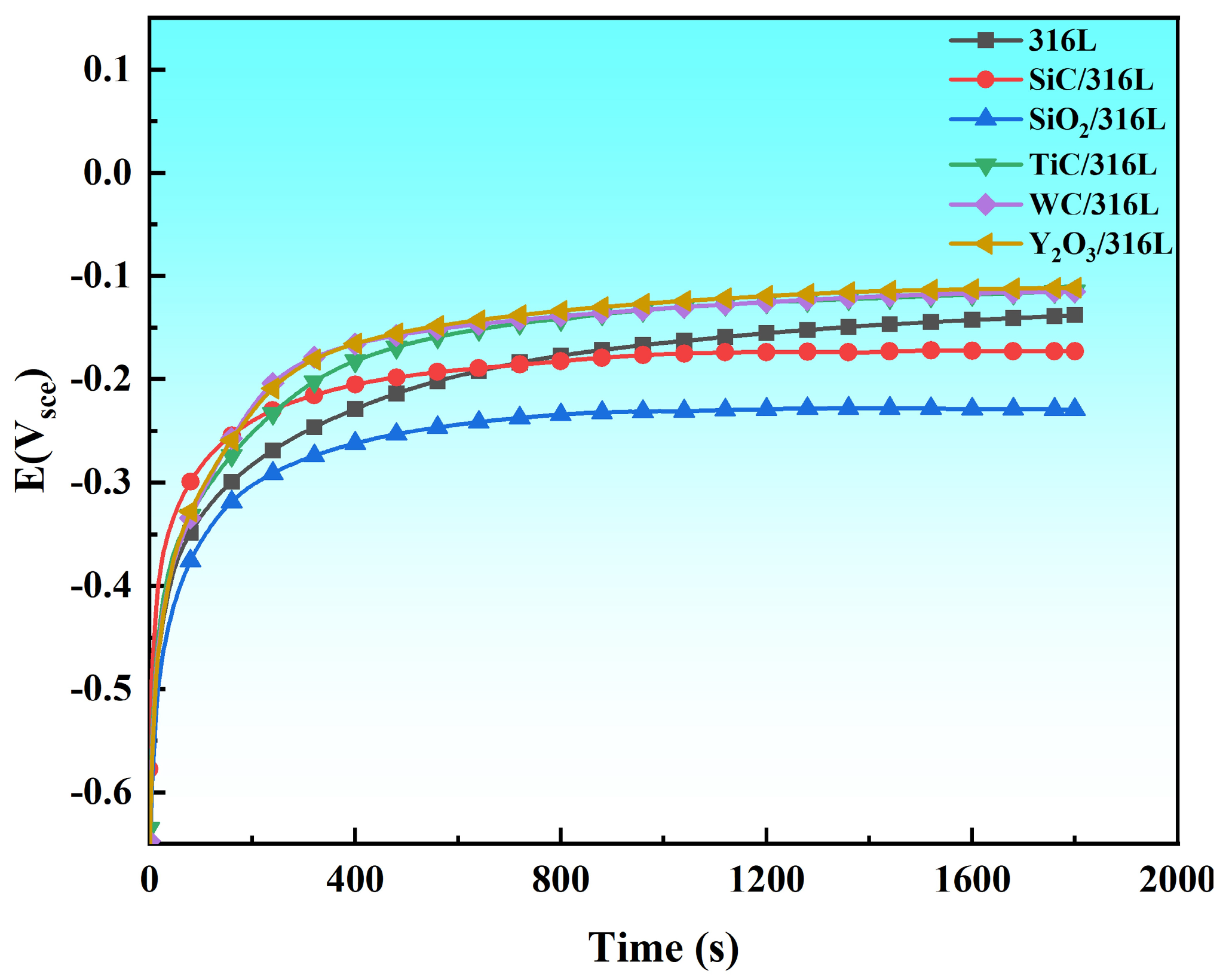

3.4.1. Open Circuit Potential

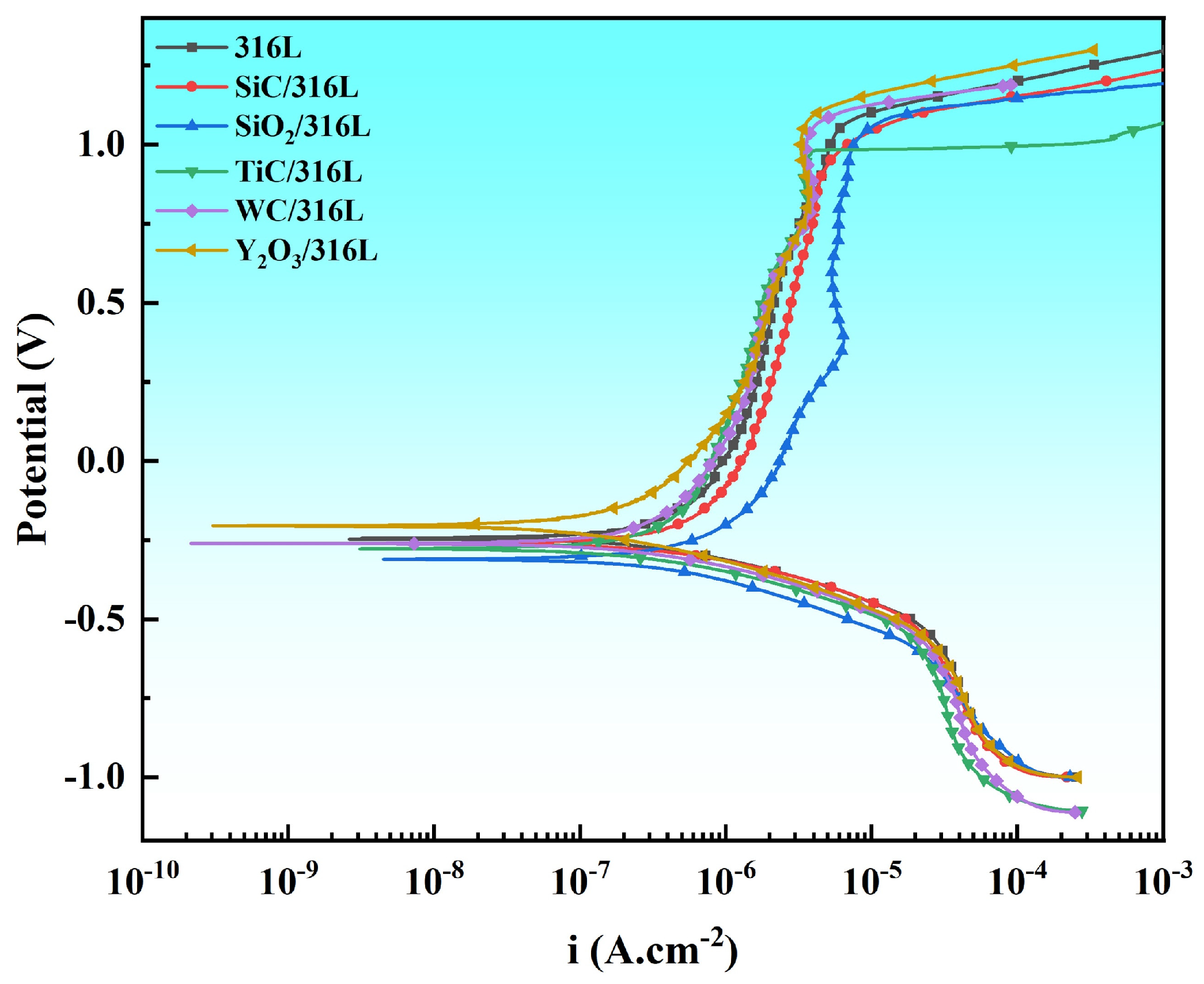

3.4.2. Potentiodynamic Polarization

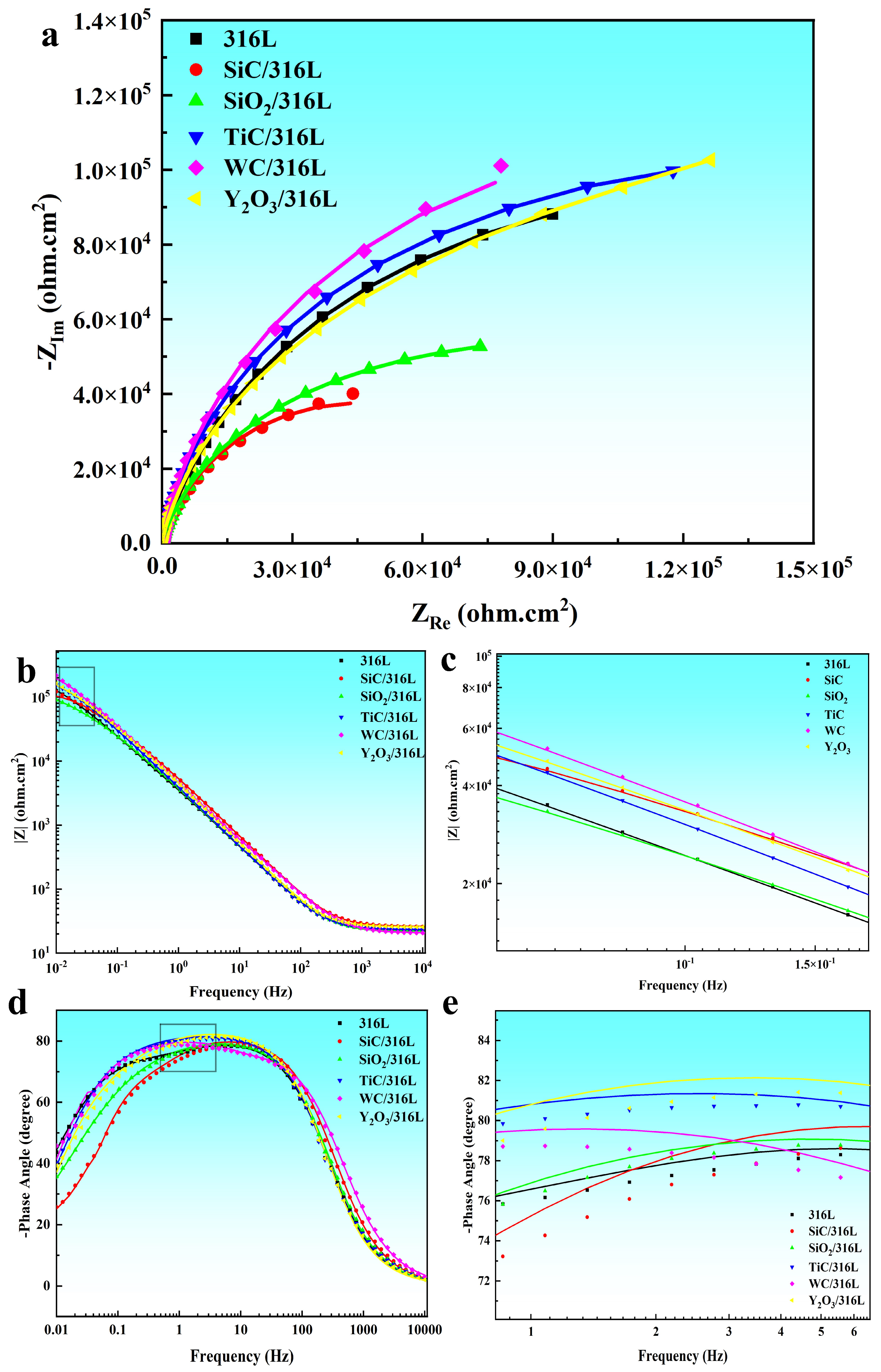

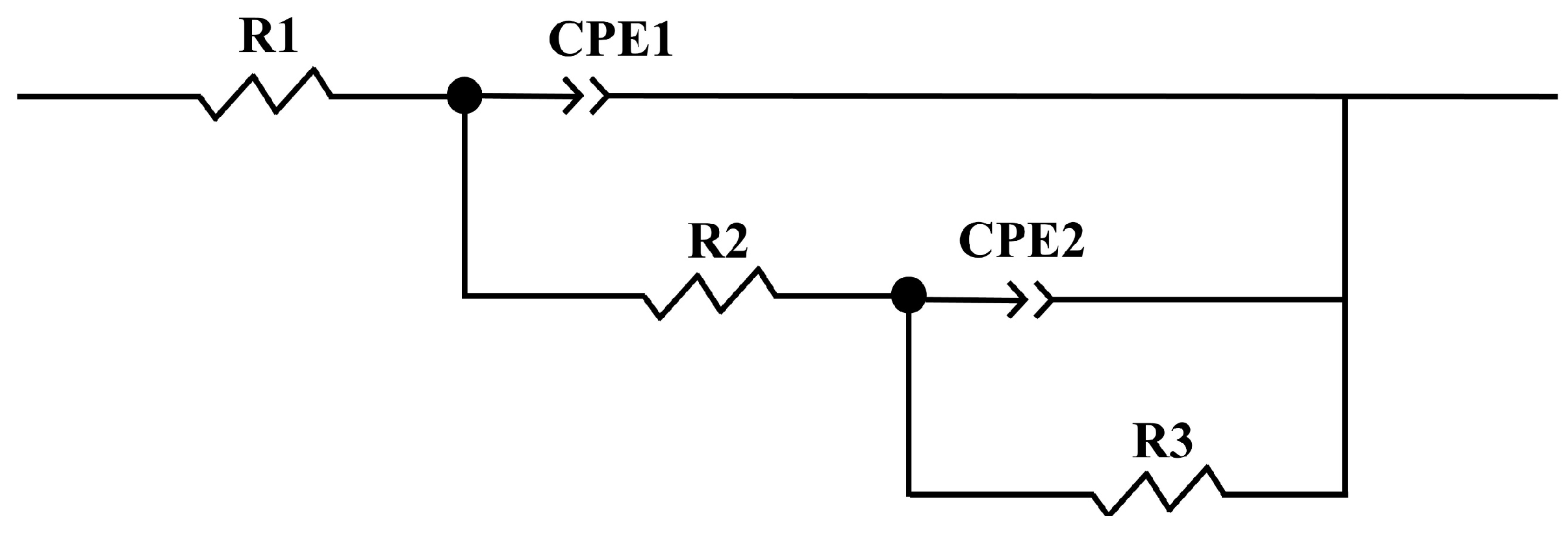

3.4.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectra

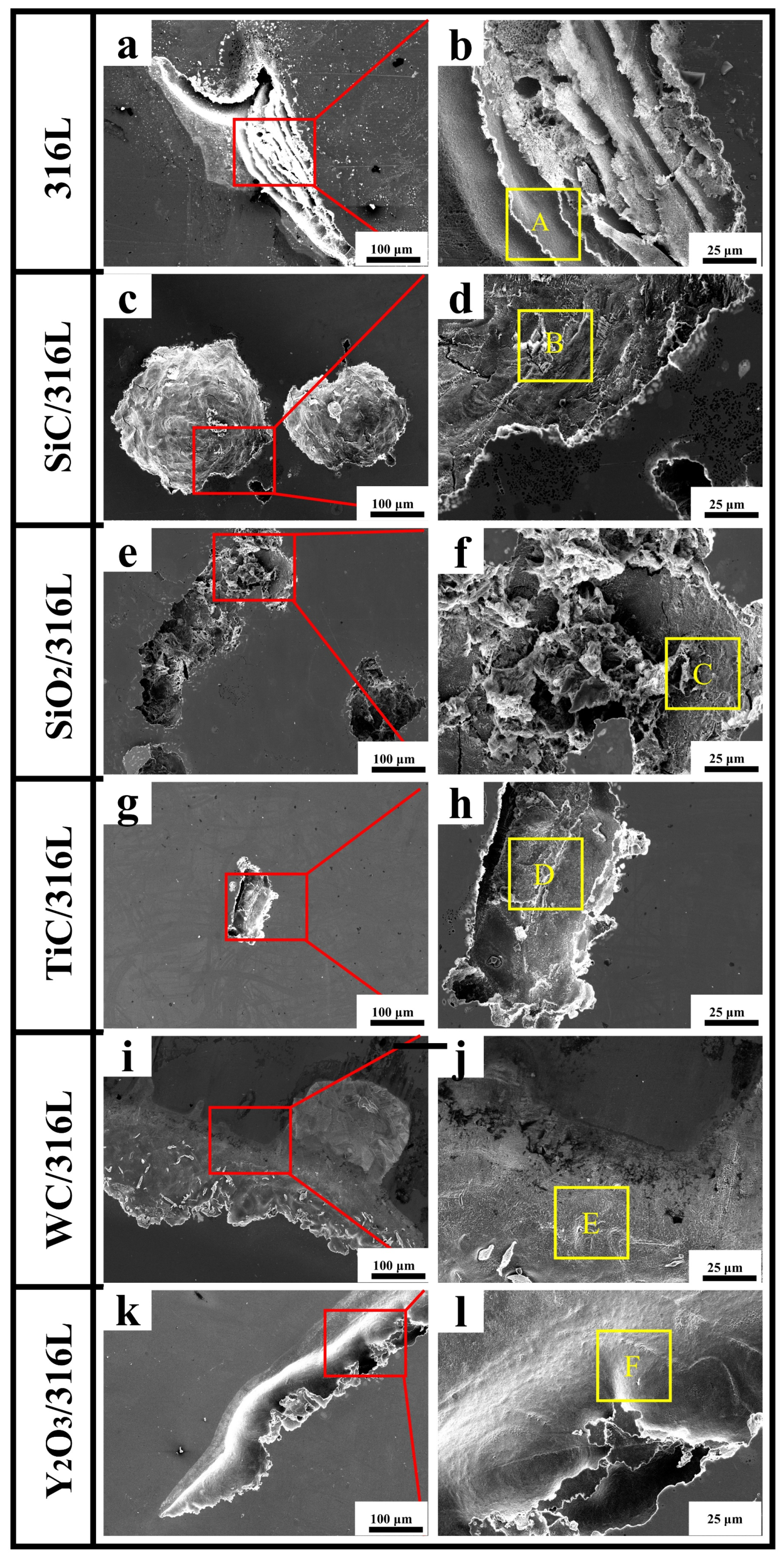

3.4.4. Corrosion Morphologies

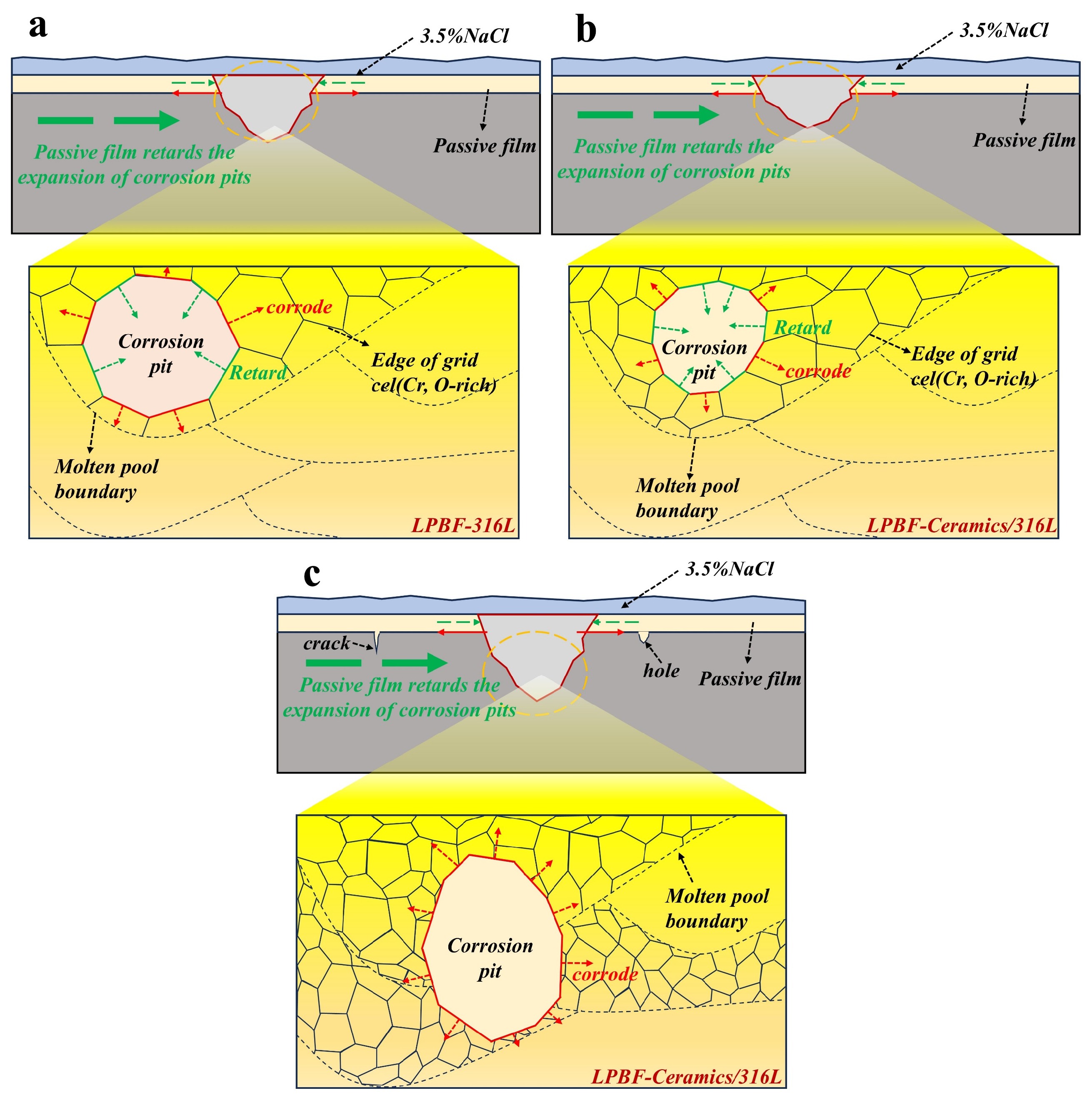

3.4.5. Corrosion Mechanism

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Five ceramic-reinforced 316L composites (1 wt.% TiC, SiC, SiO2, WC, Y2O3) were fabricated via laser powder bed fusion (LPBF). An increase in porosity within the range of 0.24–1.396% was induced by ceramic additions, among which minimal porosity (0.132%) was exhibited by Y2O3/316L. Macro-cracking was developed in SiO2/316L due to thermal stress and interface reactions, resulting in a peak porosity of 1.396%. Porosity generation was primarily attributed to three factors: unmelted particles, reduced powder flowability, and coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatch.

- (2)

- The surface micro-morphology of laser powder bed fusion (LPBF)-fabricated composites is characterized by a cellular grain structure with distinctly delineated melt pool boundaries. Following ceramic reinforcement incorporation, refinement of subgrain structures is achieved across composites to varying degrees, accompanied by increased subgrain boundary density. Grain refinement and dislocation pinning appear to be promoted by TiC, WC, and Y2O3 additions, potentially resulting in reduced cell size and elevated cell density within subgrain boundary networks of Y2O3/316L, TiC/316L, and WC/316L—with Y2O3/316L exhibiting the most pronounced refinement. Despite the apparent subgrain refinement observed in SiC/316L and SiO2/316L, localized cracking is induced by SiC and SiO2 reinforcements due to decomposition reactions and brittle interphase formation.

- (3)

- Electrochemical testing results suggested that among all evaluated composites, Y2O3/316L exhibited optimal corrosion resistance, wherein its passive film was suggested to possess superior stability. Suboptimal performance was observed in TiC/316L and WC/316L, which manifested moderate passive film stability coupled with relatively low corrosion current density, while simultaneously exhibiting comparatively elevated breakdown potentials. Conversely, the poorest corrosion resistance was displayed by SiC/316L and SiO2/316L, manifesting not only increased icorr but also reduced Ebrk values. The systematic comparison in this study suggests that Y2O3 and TiC are the most effective reinforcements for improving the corrosion resistance of the as-built L-BPF 316L.

- (4)

- Corrosion propagation in laser powder bed fusion (LPBF)-processed 316L is preferentially localized along melt pool boundaries. This mechanistic pathway remains operative in TiC/316L, WC/316L, and Y2O3/316L composites post-ceramic reinforcement; however, grain refinement accompanied by the formation of finer subgrain networks is proposed to be through particulate additions, potentially providing augmented nucleation sites for passive oxide layers. Consequently, enhanced stability and continuity may be imparted to these protective films, potentially elevating corrosion resistance. In contrast, SiC/316L and SiO2/316L exhibit elevated defect densities where degradation is predominantly governed by cracking and pitting mechanisms, resulting in corrosion resistance inferior to that of the as-built L-BPF 316L.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morgan, R.; Sutcliffe, C.J. Density analysis of direct metal laser re-melted 316L stainless steel cubic primitives. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, M.; Tuck, C.; Aboulkhair, N.T.; Maskery, I.; Ashcroft, I.; Wildman, R.D.; Hague, R. A study on the laser spatter and the oxidation reactions during selective laser melting of 316L stainless steel, Al-Si10-Mg, and Ti-6Al-4V. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2015, 46, 3842–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaei, N.; Fatemi, A. Defects in additive manufactured metals and their effect on fatigue performance: A state-of-the-art review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 117, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gu, D.; Dai, D.; Ma, C.; Xia, M. Microstructure and composition homogeneity, tensile property, and underlying thermal physical mechanism of selective laser melting tool steel parts. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukwaththa, J.; Herath, S.; Meddage, D.P.P. A review of machine learning (ML) and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) methods in additive manufacturing (3D Printing). Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zaman, L.; Cao, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhou, Z. Hardening and sensitization of conventional 316 L stainless steel and Selective Laser Melted 316 L stainless steel by cold rolling. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 47, 113271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.S. Effects of sintering conditions on the mechanical properties of metal injection molded 316l stainless steel. ISIJ Int. 2003, 43, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMangour, B.; Grzesiak, D.; Yang, J.M. In-situ formation of novel TiC-particle-reinforced 316L stainless steel bulk-form composites by selective laser melting. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 706, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Shi, W.; Li, K.; Lu, C.; An, F.; Lin, L.; Gou, F. Effects of rare earth oxides on wear resistance and corrosion resistance of 316L/TiC composite coating by laser cladding. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, B. Changing the future of additive manufacturing. Metal. Powder Rep. 2014, 69, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Barsoum, I.; Haidemenopoulos, G.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. Process parameter selection and optimization of laser powder bed fusion for 316L stainless steel: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 75, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zou, J.; Yang, H. Wear performance of metal parts fabricated by selective laser melting: A literature review. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2018, 19, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsse, S.; Hutchinson, C.; Gouné, M.; Banerjee, R. Additive manufacturing of metals: A brief review of the characteristic microstructures and properties of steels, Ti-6A1-4V and high-entropy alloys. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2017, 18, 584–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, B.M.; Etienne, A.; Baustert, E.; Rose, G.; Pareige, C.; Pareige, P.; Radiguet, B. Multiscale characterisation study on the effect of heat treatment on the microstructure of additively manufactured 316L stainless steel. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, B.; Kruth, J.P. Selective laser melting of biocompatible metals for rapid manufacturing of medical parts. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2007, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, P.; Rashid, R.A.R.; Masood, S.H.; Ruan, D.; Palanisamy, S. Mechanical properties of slm-printed aluminium alloys: A review. Materials 2020, 13, 4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaprakash, N.; Prabu, G.; Yang, C.H. Inclusion of nano silicon particle in SS316L through LPBF and its responses on corrosion behaviour. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 26450–26468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandaghi, M.R.; Pouraliakbar, H.; Shim, S.H.; Fallan, V.; Hong, S.I.; Pavese, M. In-situ alloying of stainless steel 316L by co-inoculation of Ti and Mn using LPBF additive manufacturing: Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 857, 144114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, H.; Tao, N. High-precision laser powder bed fusion of 316L stainless steel and its SiC reinforcement composite materials. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 190, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Zhou, W.; Yu, Y.; Nai, S.M.L. Additive manufacturing of TiB2 particles enabled high-performance 316L with a unique core-shell melt pool structure. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 139, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Guo, A.; Sheng, X.; Tang, R.; Qu, P.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Yin, L.; Sui, S.; Guo, S. Preparation of 316L stainless steel/WC gradient layered structures with excellent strength-elongation synergy using laser powder bed fusion. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 133, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhai, W.; Liu, Y.; Wei, W.; Chen, Y.; He, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, F. Temperature-dependent mechanical properties of La2O3-reinforced 316L stainless steel fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 925, 147884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Zhou, W.; Yu, Y.; Nai, S.M.L. Direct evidence of melting and decomposition of TiC particles in laser powder bed fusion processed 316L-TiC composite. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 198, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanlou, S.I.; Ghazanlou, S.I.; Ghazanlou, S.I.; Mohammadzadeh, R. The multifunctional performance of the laser powder bed fusion 316L stainless steel matrix composite reinforced with the CNT-ZrO2 nanohybrid. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 313, 128693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, M.J.; Hosseini, S.M.; Khodabakhshi, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Orovcik, L.; Trembošová, V.N.; Nagy, Š.; Nosko, M. Laser powder bed fusion of 316L stainless steel/Al2O3 nanocomposites: Taguchi analysis and material characterization. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaeri Karimi, M.H.; Yeganeh, M.; Alavi Zaree, S.R.; Eskandari, M. Corrosion behavior of 316L stainless steel manufactured by laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) in an alkaline solution. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 138, 106918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, L.; Wei, B.; Xu, J.; Wu, T.; Sun, C. Corrosion characterization in SLM-manufactured and wrought 316 L Stainless Steel induced by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 470, 140602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, F.; Tang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J. Effect of subcritical-temperature heat treatment on corrosion of SLM SS316L with different process parameters. Corros. Sci. 2023, 218, 111214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yin, J.; He, J.; Zhu, X.; Wu, Z.; Luo, K.; Luo, F. Effect of grain boundary engineering on electrochemical and intergranular corrosion of 316 L stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 2025, 254, 113050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ho, H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of (Ti, Nb) C ceramic-reinforced 316L stainless steel coating by laser cladding. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Peng, J.; Li, M.; Miao, X.; Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Lu, D. Anisotropy of Mechanical Property and Fracture Mechanism for SLM 316L Stainless Steel under Quasi-uniaxial and Biaxial Tensile Loadings. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 926, 147960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E407-07; Standard Practice for Microetching Metals and Alloys. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007.

- Yusuf, S.; Nie, M.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S.; Gao, N. Microstructure and corrosion performance of 316L stainless steel fabricated by Selective Laser Melting and processed through high-pressure torsion. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 763, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruth, J.; Levy, G.; Klocke, F.; Childs, T.H.C. Consolidation phenomena in laser and powder-bed based layered manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2007, 56, 730–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W. Balling behavior of stainless steel and nickel powder during selective laser melting process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 59, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Dai, Q.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, C. Insight into the Enhancing Mechanical Strength of CoCrNi/TiC Composites Fabricated by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 924, 147786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yang, Q.; Li, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of in situ synthesized ceramic reinforced 316L/IN718 matrix composites. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 93, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Han, R.; Peng, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, X. Investigating the microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L/TiB2 composites fabricated by laser cladding additive manufacturing. J. Mate. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Zhou, W.; Nai, S.M.L. In-situ formation of TiC nanoparticles in selective laser melting of 316L with addition of micronsized TiC particles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 829, 142179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiN/Inconel 718 composites fabricated by selective laser melting. Acta Metall. Sin. 2021, 57, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Liverani, E.; Toschi, S.; Ceschini, L.; Fortunato, A. Effect of selective laser melting (SLM) process parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L austenitic stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 249, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Shen, Y. Balling phenomena in direct laser sintering of stainless steel powder: Metallurgical mechanisms and control methods. Mater. Des. 2009, 30, 2903–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMangour, B.; Grzesiak, D.; Cheng, J.; Ertas, Y. Thermal behavior of the molten pool, microstructural evolution, and tribological performance during selective laser melting of TiC/316L stainless steel nanocomposites: Experimental and simulation methods. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 257, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, S.; Anderson, A.; Rubenchik, A.; King, W. Laser powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing: Physics of complex melt flow and formation mechanisms of pores, spatter, and denudation zones. Acta Mater. 2016, 108, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, P.; Lu, C.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, R. Microstructure and tensile properties of selective laser melting forming 316L stainless steel. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2018, 39, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Suryawanshi, J.; Prashanth, K.G.; Ramamurty, U. Mechanical behavior of selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 696, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Liu, L.; Zou, J.; Li, X.; Cui, D.; Shen, Z. Oxide dispersion strengthened stainless steel 316L with superior strength and ductility by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 42, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, C.; Landolt, D. Passive films on stainless steels—Chemistry, structure and growth. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xiong, Z.; Qiu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Macdonald, D. Corrosion behavior of carbon steel in dilute ammonia solution. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 364, 137295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuir-Torres, J.; Al-Mahdy, A.; Sharp, M.; Opoz, T.; Zhu, G.; Bashir, M.; Kotadia, H. The influence of texture density and free surface energy on the corrosion resistance of laser-textured 316L stainless steel. npj Mater. Degrad. 2025, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R. Pitting corrosion of metals. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2010, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laleh, M.; Hughes, A.; Xu, W.; Cizek, P.; Tan, M. Unanticipated drastic decline in pitting corrosion resistance of additively manufactured 316L stainless steel after high-temperature post-processing. Corros. Sci. 2020, 165, 108412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Huang, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X. Microstructural evolution and corrosion behaviors of Inconel 718 alloy produced by selective laser melting following different heat treatments. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Chen, F.; Zheng, L. Microstructure and corrosion resistance of NiCrMoSi-SiC coatings via laser alloyed on Ti6Al4V surfaces. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1020, 179358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Bai, P.; Qu, H.; Liang, M.; Liao, H.; Wu, L.; Huo, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiC-reinforced 316L stainless steel composites fabricated using selective laser melting. Metals 2019, 9, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Shen, X.; Lu, Z.; Qian, Y.; Yang, L.; Lu, D.; Zou, J.; Xu, J. Corrosion behaviors of selective laser melted inconel 718 alloy in naoh solution. Acta Metall. Sin. 2022, 58, 324. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Tan, X.; Tor, S.; Yeong, W. Selective laser melting of stainless steel 316L with low porosity and high build rates. Mater. Des. 2016, 104, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuir-Torres, J.; Yang, X.; West, G.; Kotadia, H.R. Corrosion behaviour of SiC particulate reinforced AZ31 magnesium matrix composite in 3.5% NaCl with and without heat treatment. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 320, 129467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szummer, A.; Janik-Czachor, M.; Hofmann, S. Discontinuity of the passivating film at nonmetallic stainless steels. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1993, 34, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J. Effect of grain size on mechanical property and corrosion resistance of the ni-based alloy 690. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhi, M.; Deen, K.; Greenlee-Wacker, M.; Haider, W. Additively manufactured 316L stainless steel with improved corrosion resistance and biological response for biomedical applications. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, H.; Dai, J.; Han, Y.; Qu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T. Why CoCrFeMnNi HEA could not passivate in chloride solution—A novel strategy to significantly improve corrosion resistance of CoCrFeMnNi HEA by n-alloying. Corros. Sci. 2022, 204, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanier, C.; Venugopalan, R.; Pelton, A.R. Corrosion resistance and biocompatibility of passivated NiTi. In Shape Memory Implants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.K.; Arya, S.B.; Nayak, J. Meltpool Characteristics, Microstructure, and Corrosion Performance of Laser-Directed Energy Deposition Cladded 316 L SS/X70 Steel for Oilfield Applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, K.D.; Birbilis, N. Effect of grain size on corrosion. Corrosion 2010, 66, 075005-1–075005-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Burstein, G.T. The generation of surface roughness during slurry erosion corrosion and its effect on the pitting potential. Corros. Sci. 1996, 38, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhao, T.; Akiyama, E.J.; Ramamurty, U. Corrosion and stress corrosion cracking resistances of laser powder bed fused and binder jetted 316L austenitic stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 2025, 252, 112968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprouster, D.J.; Cunningham, W.S.; Halada, G.P.; Yan, H.; Pattammattel, A.; Huang, X.J.; Olds, D.; Tilton, M.; Chu, Y.S.; Dooryhee, E.; et al. Dislocation microstructure and its influence on corrosion behavior in laser additively manufactured 316L stainless steel. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiong, H.; Li, X.; Qi, W.; Wang, J.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. Improved corrosion performance of selective laser melted stainless steel 316L in the deep-sea environment. Corros. Commun. 2021, 2, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godec, M.; Zaefferer, S.; Podgornik, B.; Podgornik, B.; Šinko, M. Quantitative multiscale correlative microstructure analysis of additive manufacturing of stainless steel 316L processed by selective laser melting. Mater. Charact. 2020, 160, 110074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, M.; Appiah, A.; Woźniak, A.; Nuckowski, P. Impact of titanium addition on microstructure, corrosion resistance, and hardness of As-Cast Al+ 6% Li alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 316L Chemical Composition (wt.%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Mn | P | S | Si | Cr | Ni | Mo | N | Fe |

| 0.03 | 2 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.075 | 16–18 | 10–14 | 2–3 | 0.10 | tolerance |

| Alloy | Ecorr (mVSCE) | icorr (A·cm−2) | Ebrk (mVSCE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 316L | −308 | 9.12 × 10−7 | 1021 |

| SiC/316L | −337 | 1.69 × 10−6 | 935 |

| SiO2/316L | −440 | 2.93 × 10−6 | 996 |

| TiC/316L | −327 | 5.51 × 10−7 | 981 |

| WC/316L | −311 | 5.69 × 10−7 | 1048 |

| Y2O3/316L | −279 | 4.47 × 10−7 | 1081 |

| R1, Ω·cm2 | Q1, Ω−1Sncm2 | n1 | R2, Ω·cm2 | Q2 | n2 | R3, Ω·cm2 | x2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 316L | 23.02 | 4.91 × 10−5 | 0.91 | 1.94 × 104 | 1.52 × 10−5 | 0.71 | 2.11 × 105 | 8.1 × 10−4 |

| SiC/316L | 26.07 | 3.29 × 10−5 | 0.91 | 3.65 × 104 | 2.18 × 10−5 | 0.88 | 5.16 × 104 | 1.2 × 10−3 |

| SiO2/316L | 22.05 | 4.86 × 10−5 | 0.91 | 2.11 × 104 | 1.96 × 10−5 | 0.45 | 1.74 × 105 | 9.8 × 10−4 |

| TiC/316L | 23.31 | 4.65 × 10−5 | 0.92 | 8.68 × 104 | 9.79 × 10−6 | 0.55 | 1.58 × 105 | 7.5 × 10−4 |

| WC/316L | 20.65 | 3.87 × 10−5 | 0.89 | 5.41 × 104 | 2.42 × 10−6 | 1 | 2.42 × 105 | 1.5 × 10−3 |

| Y2O3/316L | 25.82 | 3.89 × 10−5 | 0.93 | 7.50 × 104 | 2.04 × 10−5 | 0.71 | 1.62 × 105 | 5.3 × 10−5 |

| Area | Cr | Mo | Mn | O | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 20.33 | 2.47 | 1.11 | 1.22 | 74.87 |

| B | 20.19 | 2.55 | 1.16 | 1.31 | 74.79 |

| C | 24.63 | 0 | 1.71 | 3.11 | 70.55 |

| D | 22.03 | 3.91 | 1.19 | 2.83 | 70.04 |

| E | 20.52 | 0 | 0.98 | 1.49 | 77.01 |

| F | 20.76 | 0 | 1.37 | 0.93 | 76.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, J.; Yan, J.; Li, C.; Yang, Y. Comparing Microstructure and Corrosion Performance of Laser Powder Bed Fusion 316L Stainless Steel Reinforced with Varied Ceramic Particles. Metals 2026, 16, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020173

Liang J, Yan J, Li C, Yang Y. Comparing Microstructure and Corrosion Performance of Laser Powder Bed Fusion 316L Stainless Steel Reinforced with Varied Ceramic Particles. Metals. 2026; 16(2):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020173

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Jingyang, Jin Yan, Chuanqiang Li, and Yang Yang. 2026. "Comparing Microstructure and Corrosion Performance of Laser Powder Bed Fusion 316L Stainless Steel Reinforced with Varied Ceramic Particles" Metals 16, no. 2: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020173

APA StyleLiang, J., Yan, J., Li, C., & Yang, Y. (2026). Comparing Microstructure and Corrosion Performance of Laser Powder Bed Fusion 316L Stainless Steel Reinforced with Varied Ceramic Particles. Metals, 16(2), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020173