Abstract

The performance of Zr-2.5Nb alloy pressure tubes in nuclear reactors is critically dependent on the behavior of precipitated hydrides. In this study, a hydrogen-charged Zr-2.5Nb alloy pressure tube was subjected to in situ tensile testing combined with electron backscatter diffraction to elucidate microcrack evolution and microstructural adaptation. Initially, longitudinal hydride–hydride interface cracks nucleated at non-coherent interfaces of two types of hydrides due to the inherent brittleness. Subsequently, stress redistribution by a small proportion of hydride–hydride interface cracks resulted in the emergence of microcracks at the transverse hydride–matrix interfaces, accompanied by partial hydride phase transformation. Finally, under high strain conditions, increased dislocation movement in the matrix triggered a single slip system, leading to the formation of numerous low-angle grain boundaries. As strain further increased, multiple slip systems were activated, and longitudinal matrix–matrix interface cracks began to nucleate at certain grain boundary locations.

1. Introduction

Zr-2.5Nb alloys are identified as optimal materials for pressure tubes in power heavy water reactors (PHWRs) due to their low thermal neutron absorption cross-section, applicable mechanical properties, and exceptional corrosion resistance [1,2]. The pressure tube undergoes slow water-side corrosion, accompanied by hydrogen production in the high temperature and pressure hydrochemical medium [3]. Hydrides precipitate in the zirconium alloy matrix when the absorbed hydrogen exceeds the terminal solid solubility. Four kinds of hydrides characterized by different crystal structures have been identified: hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure ζ-Zr2H, face-centered tetragonal (FCT) γ-ZrH, face-centered cubic (FCC) δ-ZrH1.66, and FCT ε-ZrH2 [4,5,6]. The mismatch between the lattice of the hydride and the zirconium alloy matrix, along with the inherent brittleness of the hydride itself, leads to the formation of microcracks in the pressure tube during normal service [7,8].

It is widely known that the precipitation of hydrides can cause macroscopic brittle fractures in zirconium alloys. However, there is an argument that the hydrides themselves undergo a certain degree of plastic deformation, and only when the strain reaches a threshold value will microcracks form, rather than being purely brittle. Wang et al. noted that the δ hydride activated the {111} <110> slip mode to modulate non-uniform plastic deformation, revealing the characteristics of slip systems during the compression deformation process of hydrogenated Zircaloy-4 micro-pillars [9]. Saiedeh et al. further confirmed that significant dislocation slip was observed within the hydrides prior to the formation of microcracks, and the shear energy density on the specific slip systems served as the driving force for crack nucleation [10]. Once micro-cracks form, they will propagate towards the surrounding hydrides or the matrix. Synchrotron X-ray Laue microbeam diffraction tests revealed that during plastic deformation, hydrides co-deform with the matrix to accommodate deformation defects accompanied by plastic rotation and strain gradients in the hydrides [11]. The local shear action at the hydride–matrix interface, coupled with the enhancement and hindrance of the phase boundary on the matrix slip bands, results in non-uniform stress distribution near the interface, thereby creating stress concentration zones. The above propensity hinges on the orientation relationship between the hydride and the matrix slip planes, which can cause stress superposition at specific interfaces, serving as a precursor to material failure. In order to further study the cooperative deformation mechanism between hydrides and the zirconium alloy matrix, Wang et al. employed in situ high-resolution electron backscatter diffraction (HR-EBSD) to quantitatively assess the geometrically necessary dislocation (GND) density during the bending experiment of hydrogenated Zircaloy-4 [12]. The results revealed that the hydride–matrix interface manifested GND accumulation precipitated by hydride formation. The GND density escalated markedly in localized areas when tensile stress was applied to the material, suggesting that the synergistic effects of hydride and tensile stress can amplify strain localization, contributing to crack initiation and propagation. The stress concentration at the interface is a crucial factor affecting the mechanical properties of the material, which is typically modulated by the spatial hydride configuration, including dimensions, orientation, and intersection length.

Application of a tensile stress produces a redistribution of hydrogen between grains of different orientations, increasing hydride precipitation on the α-Zr grains, which have their c-axes stretched by the external load [13]. Colldeweih et al. [14] integrated FIB with synchrotron microbeam X-ray diffraction (XRD) to ascertain that the critical size for hydride fracture leading to delayed hydride cracking (DHC) was 5 μm, with the hydrides predominantly consisting of δ hydride. However, γ hydride precipitated adjacent to the δ hydride during the DHC, suggesting that crack propagation induced reconfiguration of the nearby stress field. Owing to the coupling effect between the stress field and hydrogen concentration, the hydrogen content at the crack tip significantly escalated, concurrently resulting in a hydrogen-depleted region in the midsection of the crack [15]. Non-uniform distribution of hydrogen concentrations contributed to the δ → γ phase transformation in the midsection of the crack. Steuwer et al. elucidated the stress-induced transformation of δ to γ hydride via a hydrogen ordering phenomenon akin to Snoek-type relaxation, which corroborates the observation of Aaron that γ hydride precipitated related to the crack, thereby further substantiating the pivotal role of the stress field in hydride phase transformation [6]. Moreover, the stress-assisted diffusion of hydrogen atoms in the vicinity of the local deformation zone was authenticated utilizing finite element models in Zr alloys, signifying that stress not only influences the morphology and orientation of hydrides but also catalyzes the diffusion of hydrogen atoms, consequently impacting the phase transformation process of hydrides [16].

Zr-2.5Nb alloy pressure tubes are the crucial structural components of heavy water reactors. The structural integrity forms the basis for the safe operation of the reactors. The precipitation of hydrides leads to irreversible degradation of the mechanical properties of the tube material, and it is a considerable safety hazard that cannot be ignored. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a systematic study on the microscopic mechanism by which hydride causes the failure of pressure tubes.

In this study, in situ tensile testing coupled with EBSD technology was employed to capture the microstructure evolution of hydrides and the matrix in hydrogenated Zr-2.5Nb alloy. The hydride distribution, phase transformation, and crack evolution at various deformation stages were systematically investigated.

2. Experimental Procedure

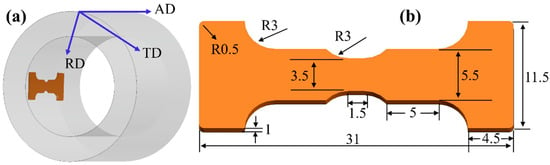

A cold-drawn Zr-2.5Nb alloy pressure tube was selected as the fresh material, with an outer diameter and wall thickness of 114 mm and 4 mm, respectively, as depicted in Figure 1. The tube was subjected to recrystallization annealing at 600 °C for 2 h to achieve an equiaxed grain structure. The hydrogen charging was carried out by the Sieverts method, during which the tube was placed in a high pressure and temperature hydrogen atmosphere for 24 h to yield a hydrogen content of ~157 ppm (by weight). The tube was heated at 400 °C for 4 h and cooled at a rate of 1.6 °C/min to ensure a uniform distribution of hydrides within the material.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the in situ tensile specimen. (a) Zr-2.5Nb alloy pressure tube; (b) tensile test specimen dimensions. Units are in millimeters.

The in situ tensile specimens were extracted from the tube via slow-feed electrical discharge machining wire-cutting, with the long axis of the sample aligned with the axial direction of the tube. The morphology and specific dimensions of the dog bone-shaped sample are demonstrated in Figure 1. AD, TD, and RD denote the axial, tangential, and radial directions of the pressure tube, respectively. The specimens were ground with silica sandpaper from 1000# to 5000#, followed by electrochemical polishing in an electrolyte composed of 90% methyl alcohol and 10% perchloric acid (volume fraction) to satisfy the EBSD testing requirements. The operating temperature was maintained at −30 °C with a voltage of 30 V and a duration of 20 s. The tensile test was conducted at a strain rate of 0.1 μm/s using a Thermo Scientific Apreo 2 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an EDAX Velocity Super ultra-fast EBSD detector (EDAX, Mahwah, NJ, USA). The view field was focused on the central area of the sample plane with an area of 35 μm × 35 μm and a scanning step size of 0.2 μm. The in situ tensile test was suspended when the strain reached 4.9%, 10.4%, 19.2%, and 24.1%. The collected data were processed and analyzed using AZtecCrystal (V6.1) and ATEX (V4.14).software to evaluate the evolution of microstructures.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Initial Microstructure

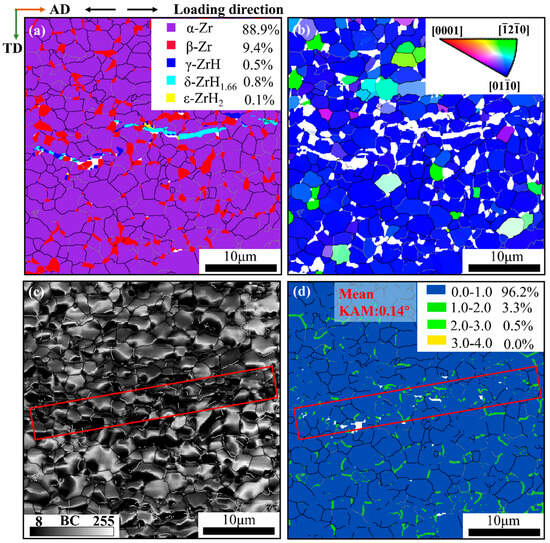

Figure 2 illustrates the microstructure of the hydrogenated Zr-2.5Nb alloy prior to tensile testing. The matrix is composed of α and β Zr phases, while three types of hydrides precipitate internally, namely, γ-ZrH (a = 4.59 Å, c = 4.95 Å, blue), δ-ZrH1.66 (a = c = 4.82 Å, green), and ε-ZrH2 (a = 3.53 Å, c = 4.42 Å, yellow), as shown in Figure 2a. The equiaxed α-grains account for the largest proportion, and the irregular β-grains are distributed along the α-grain boundaries. The statistical values of phase volume fractions are inset in Figure 2a. The δ-ZrH1.66 is the most prevalent phase among the precipitated hydrides, followed by the γ-ZrH, while the ε-ZrH2 content is minimum. Different types of hydrides interconnect with each other to form complex stringers distributed along grain or phase boundaries, while smallish hydrides are dispersed sporadically within the α-grains. Furthermore, the stringers are mainly precipitated along the AD, and only a few are distributed along the TD. The mechanical performance of the material is closely related to the distribution characteristics of the hydride, which are controlled by multiple factors, including hydrogen content, cooling rate, and texture [17,18,19]. Figure 2b employs typical triangular patterns to depict crystal orientations based on the reference inverse pole figure, where the [010] of the majority of α grains is roughly parallel to the RD (<010>//RD), indicating the initial material has a strong texture.

Figure 2.

Microstructure of hydrogenated Zr-2.5Nb alloy prior to in situ tensile testing. (a) Phase map; (b) IPF map; (c) BC map; (d) KAM map.

Figure 2c illustrates the gradient distribution of BC (band contrast) values. The red box indicates the location where the hydride is precipitated. It can be seen that the image quality in the area where the hydride is located is very poor, that is, it has a lower BC value compared to the alloy matrix. Considering the negative correlation between BC values and dislocation density, the inferior BC values in the hydride regions highlighted by the red box indicate that the areas possess a higher dislocation density [20]. The phenomenon is attributed to stress concentration and dislocation movement resulting from hydride precipitation. KAM (kernel average misorientation) denotes the value of local misorientation; thus, information about the dislocation density can be acquired from the corresponding map. The KAM distribution map of the hydrogenated specimen is exhibited in Figure 2d. Of particular interest are two regions with larger KAM values: the sub-boundaries and the hydride precipitation area. The results indicate that the precipitation of hydrides leads to lattice distortion, which is consistent with the above analysis of BC maps in Figure 2c.

3.2. Tensile Behavior

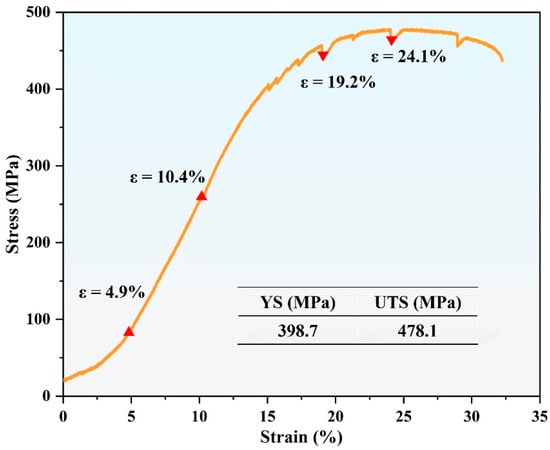

Figure 3 illustrates the engineering stress–strain curve obtained from in situ tensile testing of the hydrogenated Zr-2.5Nb alloy. The material demonstrates a yield strength (YS) of 398.7 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of 478.1 MPa. To accurately evaluate the microstructural evolution during deformation, tensile loading was interrupted at strains of 4.9%, 10.4%, 19.2%, and 24.1% to enable microstructural analysis using SEM and EBSD techniques. The four stages represent the entire process from slight plastic deformation to the formation of microcracks.

Figure 3.

Engineering stress–strain curve of hydrogenated Zr-2.5Nb alloy.

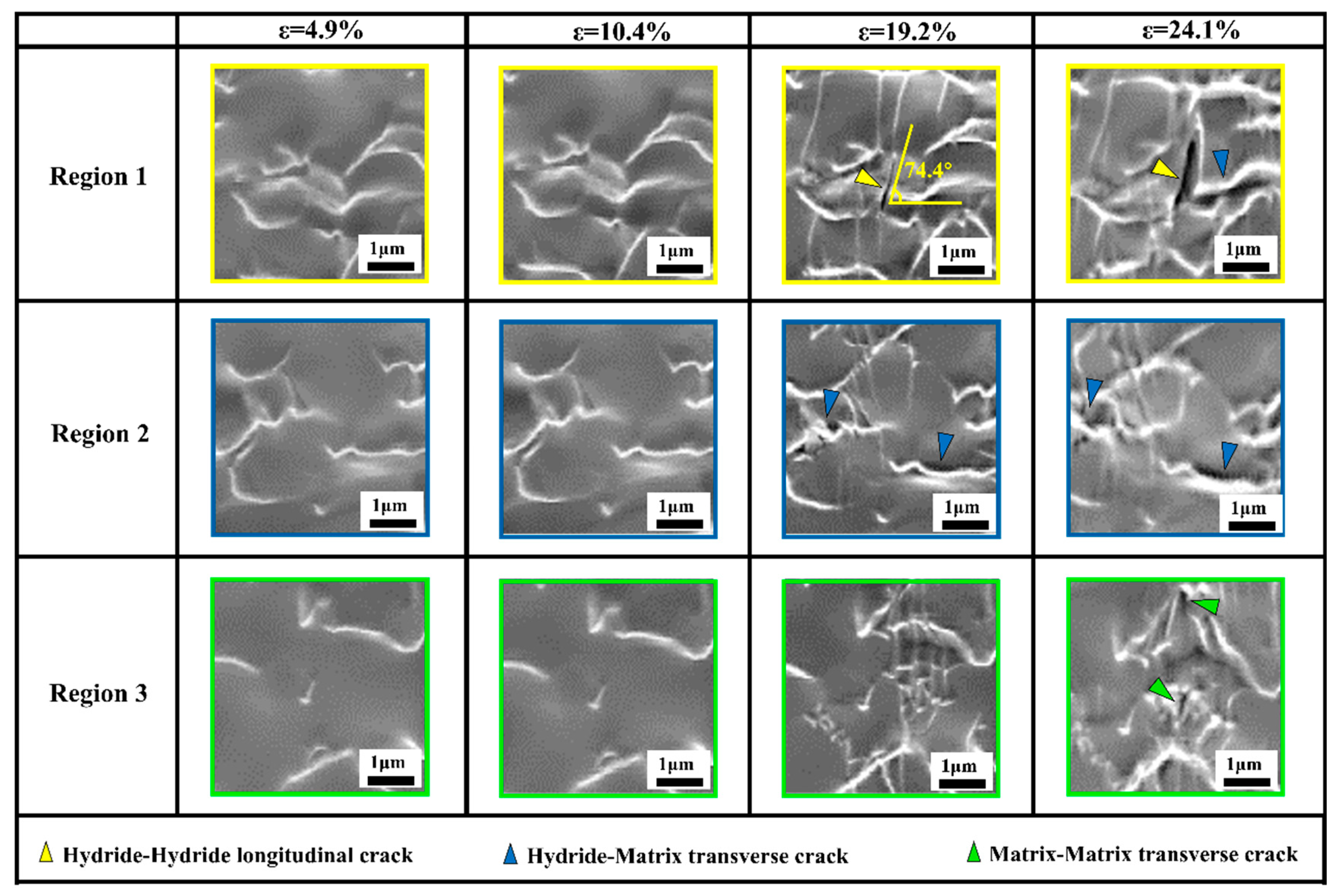

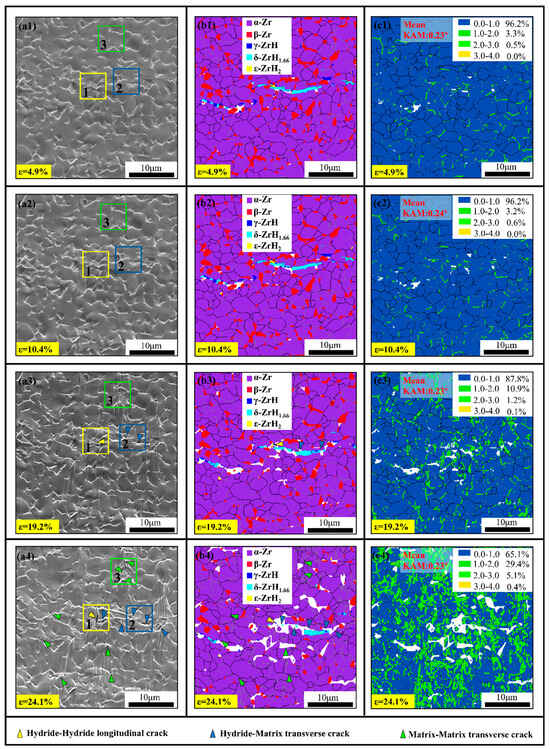

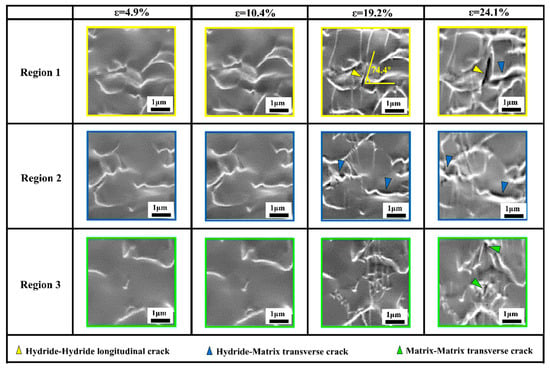

Figure 4 presents microstructural evolution images of the material at various strains. Regions 1, 2, and 3 are selected for real-time monitoring, and the corresponding local enlargement diagrams are shown in Figure 5. It is shown that no significant microstructural changes occur at strains of 4.9% and 10.4%. To quantify the evolution of dislocation density during deformation, GNDs (geometrically necessary dislocations) are calculated via the following formula [21]:

where θ represents the average local misorientation, μ is the shear modulus of the material, b is the Burgers vector, and ρGND is the density of GNDs.

Figure 4.

In situ tensile microstructural evolution of hydrogenated Zr-2.5Nb alloy: (a1–a4) SEM Images; (b1–b4) phase maps; (c1–c4) KAM maps.

Figure 5.

Enlarged views of region 1, region 2, and region 3 (in Figure 4) at different strains.

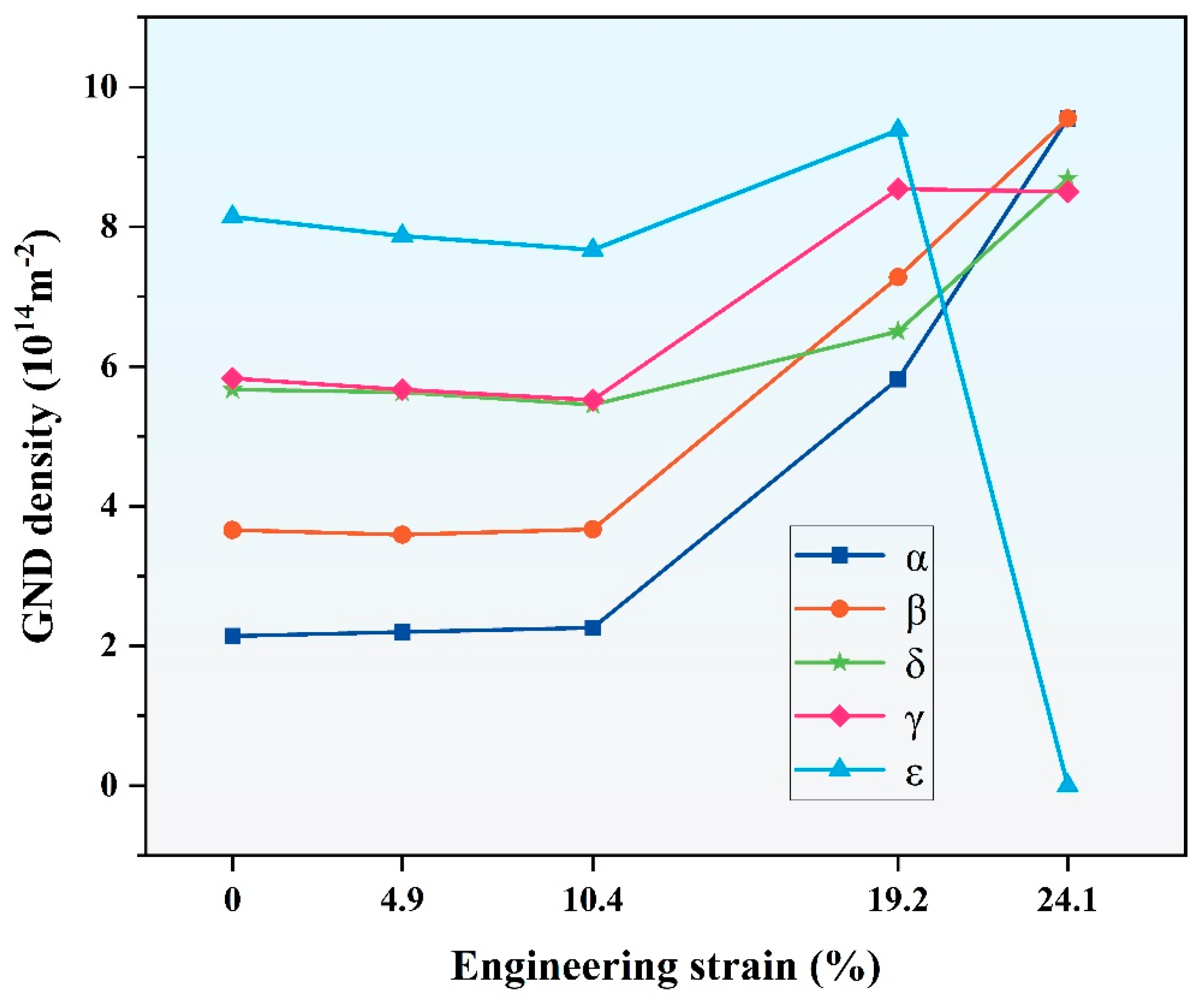

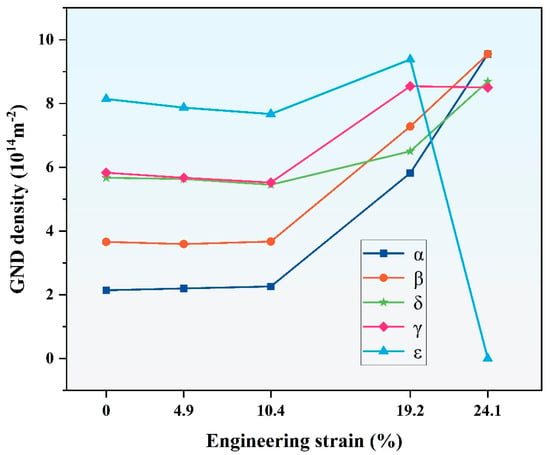

The variation tendency of GNDs is shown in Figure 6. There is very little change in dislocation density at strains of 4.9% and 10.4% compared to the initial state, and the dislocation density of hydrides is always higher than that of the matrix due to the lattice mismatch. As the strain increases to 19.2%, the grains gradually elongate along the stretching direction, as exhibited in Figure 4(a3–c3). It is worth noting that the hydride undergoes the most significant deformation, and microcracks are initially observed in region 1 (marked in yellow), forming a 74.4° angle with the stress direction. Based on the location where the cracks form, hydride–hydride longitudinal cracks, hydride–matrix transverse cracks, and matrix–matrix transverse cracks are demarcated as yellow, blue, and green triangles, respectively. Micropores indicated by blue triangles appear in region 2. The corresponding enlarged images in Figure 5 show that the micropores are actually the residual structural features of the interface cracking between the hydride and the matrix. The cracks are diminutive, and some adhesion remains within them, suggesting that they have not yet fully evolved into microcracks with smooth edges. Figure 6 indicates that compared to the matrix, the three types of hydrides display higher GND density, with the ε-hydride possessing the highest dislocation density, more than double that of the matrix, while the dislocation densities of the γ and δ hydrides are comparable. This suggests that the accumulation of dislocations within the ε-hydride enhances stress concentration, thereby promoting crack initiation and propagation. It is worth noting that due to the increase in strain and the phase transition of ε-ZrH2 to γ-ZrH, the ε-ZrH2 almost disappears at a strain of 24%. The specific transformation mechanism is discussed later. In practice, the GND of ε-ZrH2 is not included in the statistics. The variation trend between 19.2% and 24.1% is expressed by a dotted line. Additionally, shear may occur within the hydrides, enabling more dislocations to engage in the plastic deformation process, which aids in coordinating deformation between different grains or phases, thereby minimizing deformation mismatch [22].

Figure 6.

Variation tendency of GND density for five phases during in situ tensile testing of hydrogenated Zr-2.5Nb alloy.

When the strain reaches 24.1%, as depicted in Figure 4(a4–c4), the cracking in area 1 becomes more severe, and the micropores in area 2 evolve into cracks, resulting in a substantial decrease in resolution. Stress concentrates within the material as the strain increases, resulting in a decrease in the EBSD calibration, and corresponding white spaces appear in the graph. It implies that longitudinal hydride interface cracks are more likely to initiate and propagate than transverse hydride interface cracks, indicating a further deterioration in the mechanical properties at higher strains.

The location of the matrix where area 3 is situated did not show any cracks until the strain reached 24%, as shown in Figure 4(a4–c4). In contrast to the hydride cracks, these cracks are smaller and all perpendicular to the stress direction, indicating that longitudinal matrix cracks initiate after the formation of transverse hydride cracks. The emergence of these microcracks is closely associated with the alterations in dislocation density within the material. Figure 6 further indicates that at a strain of 24.1%, the GND density of the α phase attains the maximum value and increases rapidly, signifying intense dislocation activity and swift proliferation within the α grains. The cracks surrounding the hydrides can no longer effectively mitigate the stress concentration, hence the matrix assumes the role of counteracting the surplus stress.

Figure 4(c1–c4) illustrates the local distortion degree at various strains. Quantitative analysis indicates that the mean KAM value only increases from 0.23 to 0.24 at strains of 4.9% and 10.4%, suggesting that the plastic deformation degree can be almost negligible. As the strain increases, the KAM value changes more significantly, reflecting substantial changes in dislocation density within the material. The KAM value doubles to 0.57 when the strain reaches 19.2%, indicating that dislocations within the material proliferate and interact continuously under external force, leading to increased dislocation density. At a strain of 24.1%, the mean KAM value substantially increases to 0.97. The increase in KAM value is generally linked to higher dislocation density and intensified dislocation movement, resulting in changes in the material’s deformation mechanisms.

The crack formation process can be categorized into three stages. Initially, due to the inherent brittleness and lattice distortion, hydrides become focal points for stress concentration, resulting in the initiation of hydride–hydride (H-H) longitudinal cracks. However, the limited longitudinal hydride–hydride cracks are unable to accommodate the external load stress as the strain increases. Subsequently, hydride–matrix (H-M) transverse cracks are activated. Ultimately, dislocations within the matrix proliferate and move extensively when the strain achieves a threshold value, facilitating the initiation of matrix–matrix (M-M) longitudinal cracks.

3.3. Crack Evolution

3.3.1. Hydride–Hydride Longitudinal Cracks

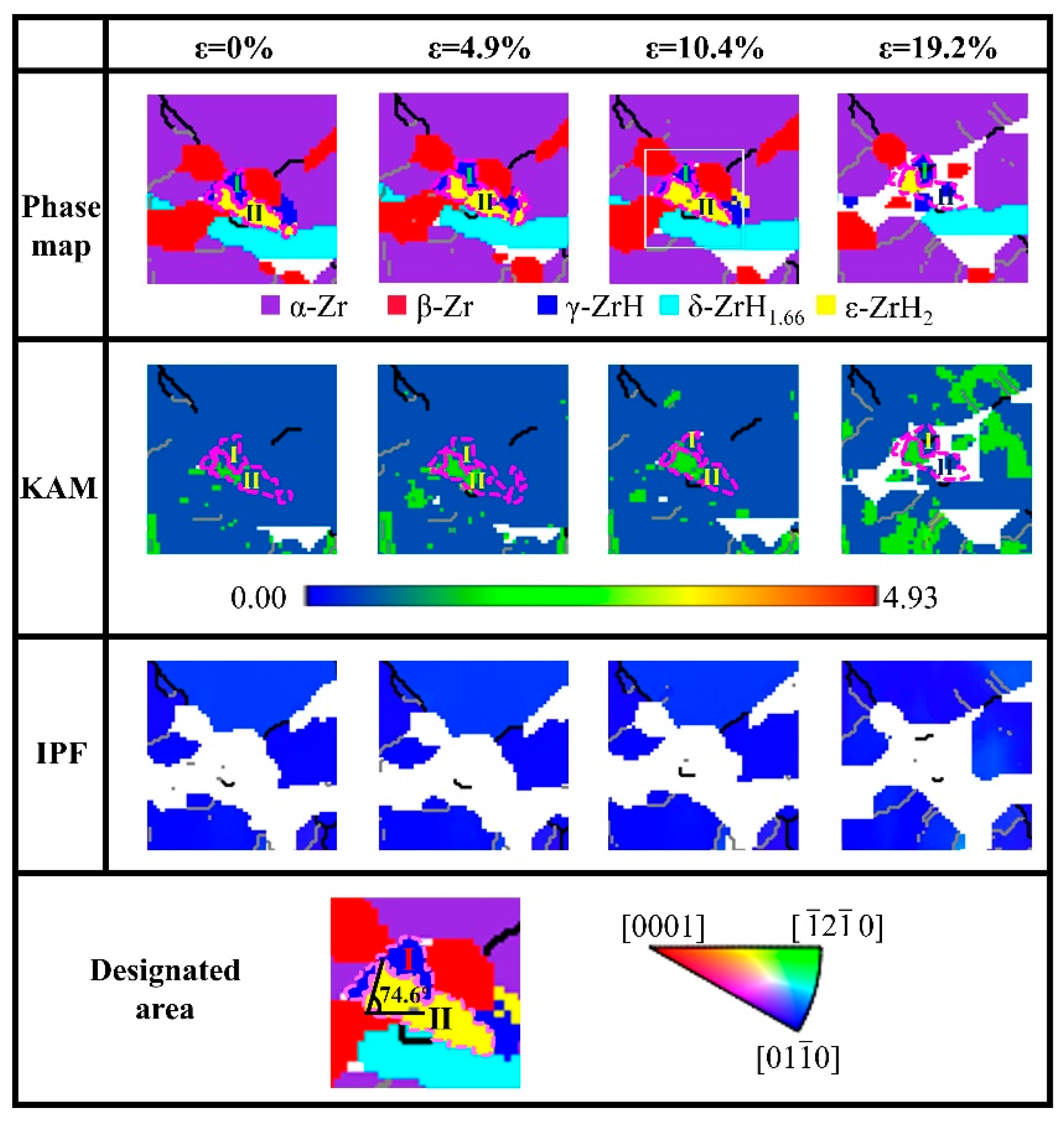

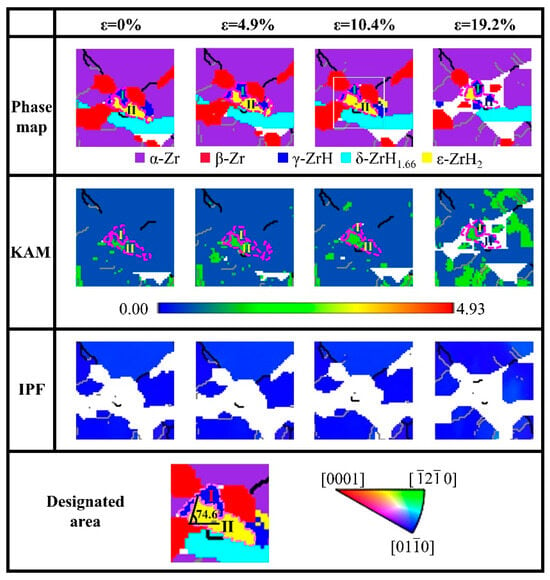

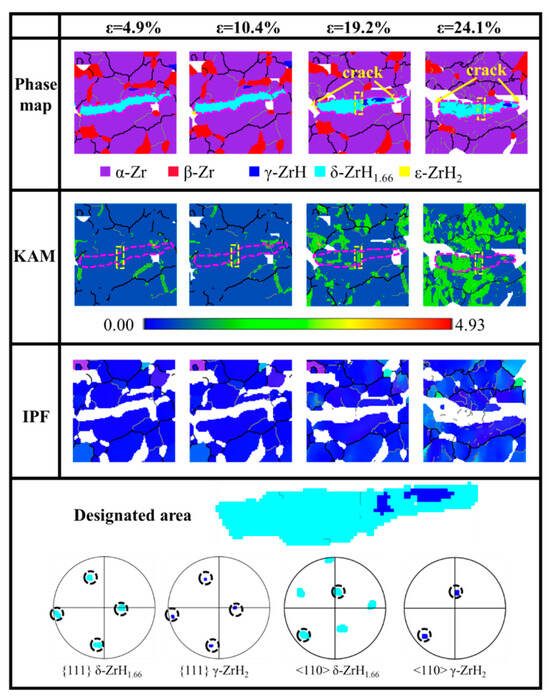

To further investigate the formation mechanism of H-H longitudinal cracks and the influence on the surrounding matrix, a detailed analysis was performed on region 1 in Figure 4. Figure 7 illustrates the microstructure evolution of region 1 during the tensile process. The phase map indicates that the interface between the γ hydride (region Ⅰ) and ε hydride (region Ⅱ) forms an angle of 74.6° with the direction of the applied stress. The angle is nearly identical to the 74.4° angle between the crack and the direction of the external force, as shown in Figure 4. It suggests that the initial crack likely originated at the interface between the γ and ε hydride.

Figure 7.

Variations of phase maps, KAM, and IPF maps for region 1 (in Figure 4) at various strains.

KAM maps provide a quantitative representation of the degree of local distortion in materials, particularly microcrack regions after deformation. During the initial tensile stage, ε hydride exhibits a higher degree of distortion compared to γ hydride and the matrix. It is attributed to the diffusion of hydrogen atoms into the matrix lattice and subsequent hydride precipitation, which leads to volume expansion and lattice distortion. The defect increases the propensity for brittle fracture in the material, making the hydride region a frequent site for microcrack initiation. As the strain increases, the material continuously adapts through dislocations to accommodate the applied stress. When the strain reaches 4.9%, the distortion degree of the two areas exhibits no significant changes. However, an increase in distortion is visible at the left end of region II, accompanied by minor distortion areas emerging at the contact points between regions I and II at a strain of 10.4%. This suggests that the presence of non-coherent interfaces reflects a crystal structure mismatch, highlighting a disparity in atomic arrangement at the interface. The phase interfaces are more prone to acting as stress concentration regions and become the preferred sites for crack initiation [23]. When the strain reaches 19.2%, the crack is observed at the interface between the γ and ε hydride, while region I is unindexed due to the deformation in the phase map of Figure 7. The IPF maps show that there is no significant change in the color of the matrix within the strain range of 1.9% to 10.4%, but at 19.2% strain, only a few grains exhibit slight color changes, indicating that the α-Zr grains adjacent to the crack alleviate stress concentration through minor grain rotation.

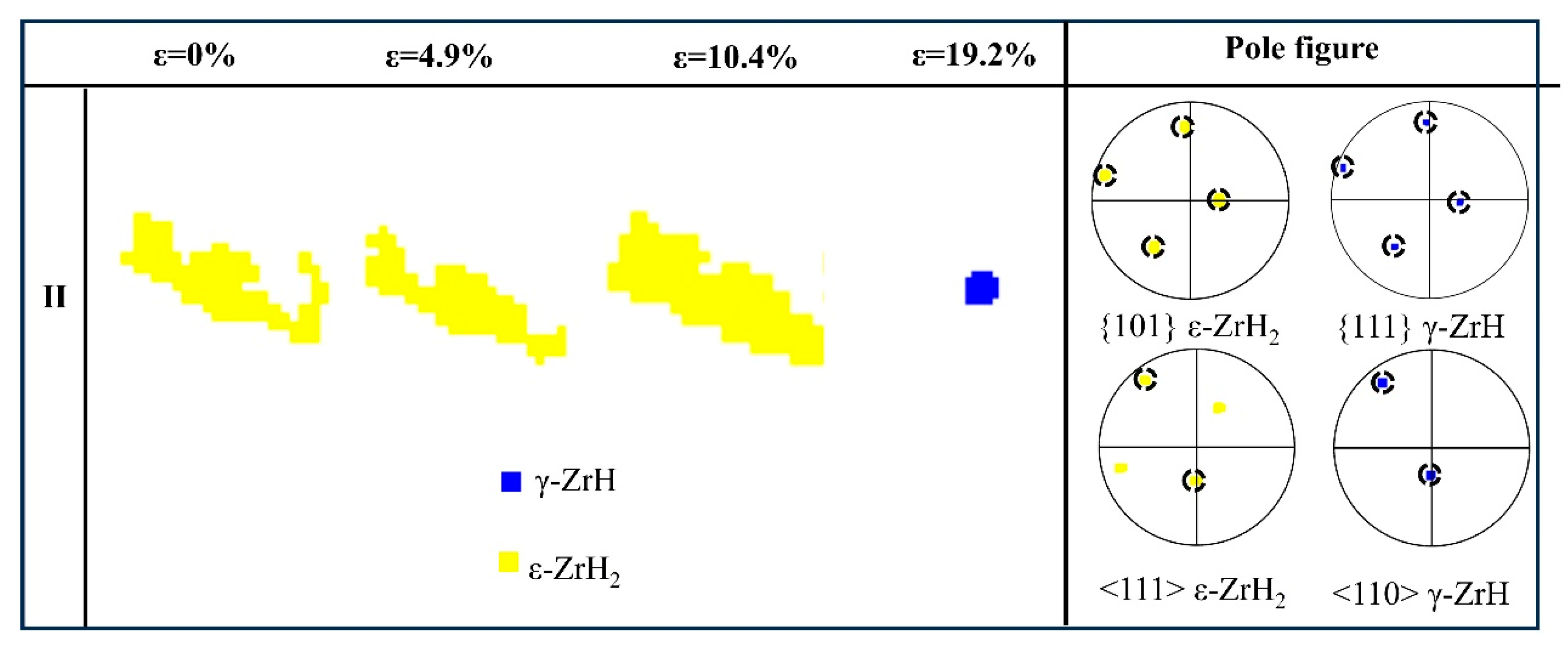

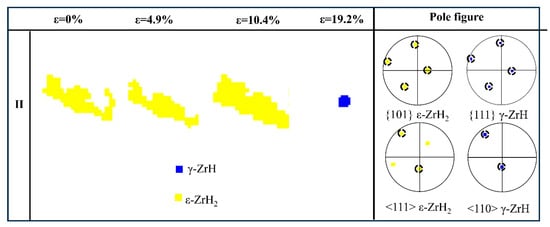

Region 2 was further analyzed to clarify the internal relations of the γ and ε hydride, as shown in Figure 8. Most of the area remains unindexed in region II, with only a few pixel areas identified as γ hydride, signifying the transformation of ε hydride into γ hydride under stress.

Figure 8.

Evolution of γ hydride and ε hydride in region 1 (in Figure 4).

Under high strain conditions, the migration behavior of hydrogen atoms undergoes substantial alterations. High strain facilitates the migration of hydrogen atoms toward defect sites, particularly microcrack areas, which are considered potent hydrogen traps due to their high energy attributes [24]. Due to the small size and high mobility, hydrogen atoms can readily penetrate the crystal structure and accumulate within the microdefects. Then, a hydrogen concentration gradient develops within the initially uniformly distributed hydrogen atoms in the ε hydride grains. In certain regions, the hydrogen content diminishes to a level that no longer satisfies the conditions for ε hydride formation, resulting in the precipitation of γ hydride. As depicted in Figure 8, γ hydride with reduced hydrogen content is observed on the right side of region II. A comparison of the phase maps of ε hydride and γ hydride reveals an orientation relationship between them: {101}ε//{111}γ and <111>ε//<110>γ.

3.3.2. Hydride–Matrix Transverse Cracks

Figure 9 presents a detailed depiction of the formation site of H-M transverse cracks in region 2 (in Figure 4), along with the changes in phase maps, KAM maps, and IPF maps of the surrounding microstructure. Phase map analysis indicates that the hydride stringers are predominantly composed of the δ hydride with a minor ε hydride. A low-angle grain boundary (LAGB, 2–10°) is detected at the right end of the stringer, with the adjacent matrix exhibiting local distortion, rendering this area a potential trigger point for crack formation. The middle position of the hydride exhibits local distortion (marked by the yellow box), which may evolve into a LAGB during subsequent tensile processes. As the strain increases from 4.9% to 10.4%, the fragmentation of ε hydrides during tensile deformation causes them to be unindexed, whereas the morphology of the δ hydride remains unchanged. The KAM value of the matrix adjacent to the right end of the hydride increases, signifying that the distortion in this area intensifies, thereby creating conditions conducive to microcrack formation.

Figure 9.

Variations in phase maps, KAM, and IPF maps of region 2 (in Figure 4) at various strains.

When the strain reaches 19.1%, microcracks emerge, especially surrounding the δ hydride with elevated GND density, suggesting that defects in this region are relatively concentrated. The elevated dislocation density promotes microcrack initiation, emphasizing its pivotal role in crack nucleation. It is noteworthy that γ hydride precipitates at the right end of the δ hydride and tends to align parallel to the stress direction. By comparing the pole figures of the γ and δ hydrides, it is confirmed that an orientation relationship exists between them: {111}δ//{111}γ and <110>δ//<110>γ. The directional diffusion of hydrogen atoms commonly occurs towards the subgrain boundaries and the microcrack defects. It leads to the formation of local areas with reduced hydrogen content within the δ hydride, where the hydrogen content fails to satisfy the conditions for the stable existence of δ hydride, thus facilitating the transformation to γ hydride with lower hydrogen content. At this juncture, the distortion region within the matrix substantially expands, primarily concentrated near grain boundaries and subgrain boundaries, whereas the distortion within the hydride is situated near the original subgrain boundaries and the left end of the newly formed hydride. When the strain reaches 24.1%, the unindexed areas near the cracks at both ends of the hydride stringer substantially expand, the left end of the hydride band further expands, and the overall tendency is to align parallel to the stress direction. Numerous sub-grain boundaries originate from the left end of the hydride stringer, and a substantial number of sub-grain boundaries are also observed within the matrix.

At a strain of 19.2%, several grains display color gradients, indicating that the orientation of the grains has changed to alleviate stress. However, within the strain range of 4.9% to 10.4%, there is no notable change in the matrix color, suggesting that the orientation variation of matrix grains is minimal at the lower strains. At a strain of 24.1%, most grains exhibit internal color gradients, demonstrating that the orientations of most matrix grains have changed along with grain sliding. The orientation variation of the matrix and sliding aid in further alleviating stress, but may also diminish the plastic deformation capacity.

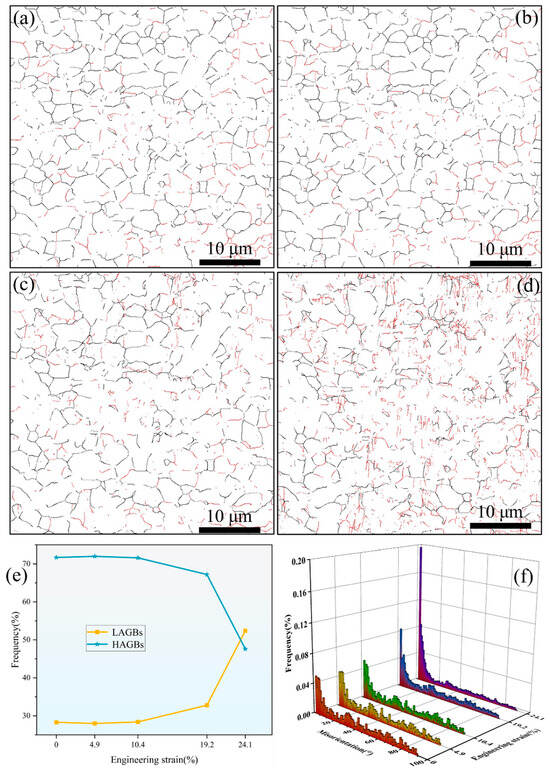

3.3.3. Matrix–Matrix Longitudinal Crack

Figure 10 illustrates the grain boundary evolution of the matrix at various strains. The distributions of grain boundaries are analyzed for samples with a strain of 4.9%–24.1%, as shown in Figure 10a–d, where black lines denote high-angle grain boundaries (HAGB, >10°), while red lines denote LAGBs. The initial microstructure is predominantly characterized by HAGBs, whereas LAGBs are less prevalent and primarily concentrated around the hydride. The number of LAGBs rises as the strain increases. Figure 10e illustrates the statistical data for HAGBs and LAGBs, while Figure 10f portrays the distribution of misorientation angles within the 0–90° range. At low strain levels, grain boundaries predominantly constitute 71.7% HAGBs and 28.3% LAGBs, with the misorientation distribution of HAGBs being relatively dispersed and exhibiting an inconspicuous trend of concentration between 30 and 40°. During the deformation process prior to the yield point, there is no notable change in the amplitude of HAGBs and LAGBs. When the strain reaches 19.2%, there is an inflection point in the proportion of LAGBs, while the proportion of HAGBs decreases correspondingly. The overall frequency distribution of misorientation angles for HAGBs diminishes without a notable decrease in any specific interval, while the misorientation angles for LAGBs exhibit a marked increase, particularly in the range of 4–6°. When the strain increases to 24.1%, the trend of change for high-angle and low-angle grain boundaries remains consistent, yet the magnitude of change intensifies. From 0.0% strain to 24.1% strain, the proportion of LAGBs rises by 85.2%, while the proportion of HAGBs diminishes by 33.6%. It is widely recognized that dislocation-mediated plastic deformation evolves through the initiation, proliferation, and accumulation of dislocations. Furthermore, dislocation arrays are susceptible to entanglement, forming various configurations such as dislocation walls, subgrain boundaries, and even microbands at higher strains, which aid in reducing stored energy [25].

Figure 10.

Grain boundary evolution of the matrix at various strains: (a) 4.9%; (b) 10.4%; (c) 19.2%; (d) 24.1%; (e) fractions of HAGBs/LAGBs; (f) distribution of misorientation angles with strain.

Strain determines the magnitude of dislocation density, and the higher the dislocation density of the sample, the greater the local misorientation. Similarly, the average local misorientation is positively correlated with dislocation density. Consequently, to quantitatively investigate the evolution of dislocation density during deformation, GNDs per area are calculated employing Formula (1).

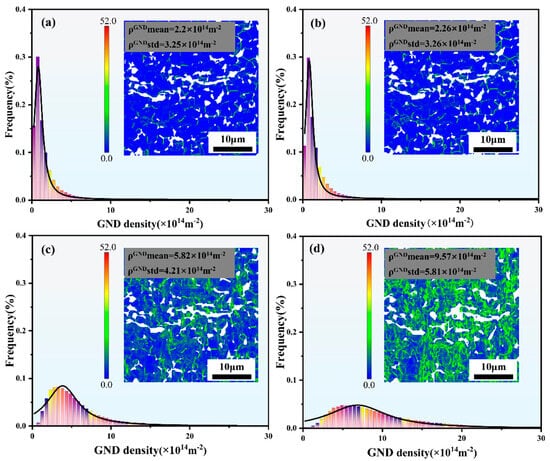

Figure 11 presents the calculated GND densities, and the KAM maps are inset in the GND variation trend graph. At strains of 4.9%, 10.4%, 19.2%, and 24.1%, the average GND densities are 2.2 × 1014 m2, 2.26 × 1014 m2, 5.82 × 1014 m2, and 9.57 × 1014 m2, respectively. It demonstrates a positive correlation between the GNDs density and strain. The positive correlation is primarily attributed to the continuous proliferation and accumulation of dislocations during the deformation process. HAGBs can effectively impede dislocation slip. However, dislocation sliding is likely to interact with non-intrinsic dislocations in LAGBs, resulting in dislocation annihilation, with dislocation density approaching zero and misorientation angles increasing to form HAGBs. When the strain reaches 24.1%, a large number of LAGBs are formed. Subsequently, the LAGBs interact with dislocations, leading to dislocation annihilation and a decrease in GND density. Concurrently, the formation of more HAGBs reduces the proportion of LAGBs.

Figure 11.

GND density histograms and corresponding distribution maps at strains of (a) 4.9%, (b) 10.4%, (c) 19.2%, and (d) 24.1%.

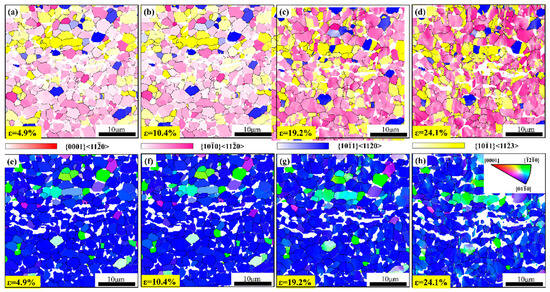

The regulation of plastic deformation encompasses dislocation slip, grain rotation, and lattice curvature, with grain rotation being a direct consequence of dislocation slip. During plastic deformation, non-uniform microstructure features are frequently observed. The features are influenced by the extent of activation of slip systems and the restrictions imposed by interactions between adjacent grains [26]. To achieve homogeneous plasticity, the activation of at least five independent slip systems is necessary [27,28]. However, plastic deformation generally involves the activation of fewer slip systems in Zr alloys, resulting in non-uniform plastic deformation. In such cases, grains are partitioned into cellular structures (cell blocks) or domains. Furthermore, the ease of rotation of different volume units within a grain varies, with the core region rotating most readily and the areas near grain boundaries being more challenging to rotate. The disparity results in the generation of lattice curvature. Consequently, under constrained conditions, grains are partitioned into multiple volume units with varying orientations, enabling the activation of different slip systems [29]. Interfaces between misoriented volume units are accommodated by the accumulation of dislocations to preserve material continuity, and the entangled dislocations constitute what are known as strain-induced boundaries. Grain splitting results from differential rotation within the grain, a process that facilitates grain refinement. The refinement of grains augments the number of grain boundaries, thereby enhancing the material’s strength and toughness. Moreover, the formation of strain-induced boundaries aids in maintaining the continuity and stability of the material.

The plastic deformation of metallic materials relies on the shear stress applied to the slip planes and directions [21]. The SF (Schmidt factor) is a crucial parameter quantifying the feasibility of slip system activation in a specific direction under shear stress, which can be formulated as

where τRSS denotes the threshold, that is, the critical resolved shear stress (CRSS), σ0.2 represents the macroscopic initial yield strength, θ and λ are respectively the angles subtended by the loading direction normal to the slip plane and that with the slip direction, and m is referred to as the SF values. Specifically, the higher the SF value of a slip system, the more readily it activates, thereby facilitating plastic deformation. The slip systems in Zr alloys mainly include basal slip {0001} <110>, prismatic slip {100} <110>, pyramidal slip <a> {101} <120>, and first-order pyramidal slip <c+a> {101} <113> [30]. The extent of activation of these slip systems dictates the plastic deformation behavior of the material. The critical resolved shear stress (CRSS) for prismatic slip is comparatively lower than that of other slip systems, rendering it the easiest to activate during the deformation process.

τRSS = σ0.2·m = σ0.2·cosθ·cosλ

In this study, a SF of 0.4 to 0.5 is designated as a soft orientation, which corresponds to the assessment of slip system activation probability in crystal plastic deformation. Figure 12 illustrates the maximum SF values of the four slip systems along the AD of the sample at various strains. Table 1 further enumerates the soft orientation percentages of the slip systems corresponding to the various strain states depicted in Figure 12, providing more detailed evidence for analyzing the predominant role of each slip system. According to Table 1, Pr<a> {100} <110> predominates throughout the in situ tensile process, followed by Py<c+a>1st {101} <113>, with Py<a> {101} <110> occurring less frequently, and Ba<a> {0001} <110> being virtually non-existent. For Pr<a> {100} <110> at various strains, the soft orientation percentage remains relatively stable, exhibiting a slight upward trend overall. It is attributed to the activation of this slip system at the onset of deformation and its lower CRSS, facilitating its sustained activity throughout the deformation process. Py<c+a>1st {101} <113> exhibits an upward trend, which may be associated with the gradual activation of the slip system as strain increases to coordinate deformation. In contrast, Py<a> {101} <110> consistently decreases, likely owing to its relatively higher CRSS and lower activity compared to other slip systems during deformation, leading to a decrease in its soft orientation percentage as strain increases. The SF and CRSS play pivotal roles in the sustained activity of slip systems. The lower CRSS of Pr<a> {100} <110> enables it to maintain activity throughout deformation, whereas the higher CRSS of Py<a> {101} <110> restricts its activation and activity, resulting in divergent trends in their soft orientation percentages.

Figure 12.

Soft orientations (SF = 0.4 to 0.5) of various slip systems at strains of (a) 4.9%, (b) 10.4%, (c) 19.2%, and (d) 24.1%. IPF maps at strains of (e) 4.9%, (f) 10.4%, (g) 19.2%, and (h) 24.1%.

Table 1.

Proportions of various slip systems at various strains during tensile deformation.

It can be observed that grains exhibit refinement or fragmentation, with some grains displaying multiple domains with orientation gradients as strain increases, by analyzing the SF and IPF maps. These indicate the heterogeneous plastic deformation characteristics within the grains. In addition to the activated slip modes, grain rotation is another vital mechanism for adapting to the strain. When the activated slip systems or slip transmission are constrained, grains rotate, causing a change in their stress state and leading to the reactivation of the slip system. Specifically, within the low strain range of 0–4.9% (Figure 12), the grain exhibits a uniform color distribution, indicating that the crystal orientation within the grain is relatively consistent. However, when the strain increases to 24.1%, the colors of multiple grains change, indicating that the grains accommodate the stress via rotation.

4. Conclusions

This study performed hydrogen absorption treatment on Zr-2.5Nb alloy pressure tubes and utilized in situ tensile testing in conjunction with EBSD technology to thoroughly investigate the initiation of cracks in hydrogen-infiltrated Zr-2.5Nb alloy, as well as the evolution of hydrides and the matrix. The conclusions of the study are as follows.

- The evolution of microcracks can be categorized into three stages: initially, the formation of longitudinal hydride–hydride interface cracks; subsequently, the emergence of transverse hydride–matrix interface cracks; and ultimately, the generation of longitudinal matrix–matrix interface cracks.

- The non-coherent interfaces of the two types of hydrides and the inherent brittleness result in the initiation of longitudinal hydride–hydride interface cracks. During crack propagation, the diffusion of hydrogen atoms induces the phase transformation ε-ZrH2 to γ-ZrH.

- The small proportion of hydride–hydride interface cracks is inadequate to absorb stress, resulting in the subsequent initiation of microcracks at the transverse hydride–matrix interface. Meanwhile, large-sized hydrides experience refinement, and phase transformation occurs in some areas, yet no rotation of hydride grains has been observed.

- Under high strain conditions, the motion of dislocations in the matrix markedly increases, resulting in the extensive formation of LAGBs. The lower CRSS of prismatic slip {100} <110> enables it to maintain activity throughout the deformation. A small portion of pyramidal slip {101} <113> activates to coordinate the deformation. As strain further increases, longitudinal matrix–matrix interface cracks begin to form at certain grain boundary locations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z.; Methodology, W.Z.; Validation, C.C.; Formal analysis, B.L. and H.S.; Investigation, H.W. and Z.F.; Resources, W.Z.; Data curation, S.S.; Writing—original draft, G.Z.; Writing—review and editing, C.C., B.L., H.S., G.Z., Z.F., and W.Z.; Supervision, H.W.; Funding acquisition, W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Talent Training Project of NIN (grant number 0701YK2418), the Qinchuangyuan Cites High-level Innovation or Entrepreneurship Talent Project (grant number: 2025RC-YJRC-032), the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2024JC-YBQN-0414), and the Qinchuangyuan Cites High-level Innovation or Entrepreneurship Talent Project (grant number: QCYRCXM-2022-164).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Changxing Cui, Huanzheng Sun, Hui Wang, Shuo Sun, Zheng Feng and Wen Zhang were employed by Northwest Institute for Non-Ferrous Metal Research. Author Bo Li was employed by Northwest Nonferrous Metal Baoji Innovation Research Institute. Author Guannan Zhao was employed by Shanghai Nuclear Engineering Research and Design Institute Co., Ltd. Besides, the authors declare that this study received funding from NIN. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Sunil, S.; Gopalan, A.; Bind, A.K.; Sharma, R.K.; Murty, T.N.; Singh, R.N. Effect of radial hydride on delayed hydride cracking behaviour of Zr-2.5Nb pressure tube material. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 542, 152457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Wang, J.X.; Zou, X.W.; Beyerlein, I.J.; Han, W.Z. Texture evolution and temperature-dependent deformation modes in ambient-and cryogenic-rolled nanolayered Zr-2.5Nb. Acta Mater. 2022, 234, 118023. [Google Scholar]

- Nouduru, S.K.; Mandapaka, K.K.; Dubey, V.; Roychowdhury, S.; Kain, V. Uniform oxidation in steam and nodular corrosion in gas phase of Zr-2.5Nb pressure tube material—Effect of nature of initial oxide. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 572, 154067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Khan, M.K.; Pathak, M.; Singh, R.N.; Chakravartty, J.K. Hydrogen in Zircaloy: Mechanism and its impacts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 5976–5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, J.; Zaeem, M.A.; Tonks, M. A review on hydride precipitation in zirconium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2015, 466, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuwer, A.; Santisteban, J.R.; Preuss, M.; Peel, M.J.; Buslaps, T.; Harada, M. Evidence of stress-induced hydrogen ordering in zirconium hydrides. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.E.; McRae, G.A.; Buyers, A.; Hanlon, S. Gamma-zirconium hydride on DHC fracture surfaces is a legitimate stable phase, not a metastable phase. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 548, 152839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, H.D.; Song, X.P. Expansion deformation behavior of zirconium alloy claddings with different hydrogen concentrations. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 554, 153082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Giuliani, F.; Britton, T.B. Slip–hydride interactions in Zircaloy-4: Multiscale mechanical testing and characterization. Acta Mater. 2020, 200, 537–550. [Google Scholar]

- Marashi, S.; Abdolvand, H. The interactions of deformation twins, zirconium hydrides, and microcracks. Int. J. Plast. 2024, 183, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekes, H.E.; Vorontsov, V.A.; Dolbnya, I.P.; Plummer, J.D.; Giuliani, F.; Britton, T.B.; Dye, D. In situ micropillar deformation of hydrides in Zircaloy-4. Acta Mater. 2015, 92, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kalácska, S.; Maeder, X.; Michler, J.; Giuliani, F.; Britton, T.B. The effect of δ-hydride on the micromechanical deformation of a Zr alloy studied by in situ high angular resolution electron backscatter diffraction. Scr. Mater. 2019, 173, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaíno, P.; Santisteban, J.R.; Vicente, A.M.A.; Banchik, A.D.; Almer, J. Effect of crystallite orientation and external stress on hydride precipitation and dissolution in Zr2.5%Nb. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 447, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colldeweih, A.W.; Makowska, M.G.; Tabai, O.; Sanchez, D.F.; Bertsch, J. Zirconium hydride phase mapping in Zircaloy-2 cladding after delayed hydride cracking. Materialia 2023, 27, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ishii, A.; Mi, S.; Ogata, S.; Li, J.; Han, W. Dislocation-Mediated Hydride Precipitation in Zirconium. Small 2022, 18, 2105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondro, A.; Taherijam, M.; Abdolvand, H. Diffusion and redistribution of hydrogen atoms in the vicinity of localized deformation zones. Mech. Mater. 2023, 177, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.H.; Beyerlein, I.J.; Han, W.Z. Annealing cracking in Zr and a Zr-alloy with low hydrogen concentration. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 182, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, S.; Yang, K.; Wang, Y. Morphology and microstructure evolution of surface hydride in zirconium alloys during hydrogen desorption process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 24247–24255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Garbe, U.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Studer, A.J.; Sun, G.; Harrison, R.P.; Liao, X.; Vicente, A.M.A.; Santisteban, J.R.; et al. Microstructure and texture analysis of δ-hydride precipitation in Zircaloy-4 materials by electron microscopy and neutron diffraction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2014, 47, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wang, Q.; El-Awady, J.A.; Raabe, D.; Zaiser, M. Strain rate dependency of dislocation plasticity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Ya, R.; Sun, M.; Ma, R.; Cui, J.; Li, Z.; Tian, W. In-situ EBSD study of deformation behavior of nickel-based superalloys during uniaxial tensile tests. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Lunt, D.; Atkinson, M.D.; Fonseca, J.Q.D.; Preuss, M.; Honniball, P.; Frankel, P. The role of hydrides and precipitates on the strain localisation behaviour in a zirconium alloy. Acta Mater. 2023, 261, 119327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, X. Interactions between dislocations and boundaries during deformation. Materials 2021, 14, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, A.T.; Capolungo, L.; Chen, L.Q.; Cinbiz, M.N.; Daymond, M.R.; Koss, D.A.; Lacroix, E.; Pastore, G.; Simon, P.C.A.; Tonks, M.R.; et al. Hydrogen in zirconium alloys: A review. J. Nucl. Mater. 2019, 518, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, S.; Jain, R.; Gurao, N.P. Microstructural characteristics governing the lattice rotation in Al-Mg alloy using in-situ EBSD. Mater. Charact. 2021, 180, 111405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Hu, L.; Baker, I. In-situ EBSD study of the active slip systems and substructure evolution in a medium-entropy alloy during tensile deformation. Mater. Charact. 2024, 217, 114405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Baker, I.; Cai, Z.; Chen, S.; Poplawsky, J.D.; Guo, W. The effect of interstitial carbon on the mechanical properties and dislocation substructure evolution in Fe40.4Ni11.3Mn34.8Al7.5Cr6 high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2016, 120, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.T. Tensile deformation of low-density Fe–Mn–Al–C austenitic steels at ambient temperature. Scr. Mater. 2013, 68, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Hughes, D.A.; Godfrey, A.W.; Chen, Q.; Hansen, N.; Wu, G. Microstructure and strength of a tantalum-tungsten alloy after cold rolling from small to large strains. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shi, H.; Lin, G.; Zhang, R.; Gui, K.; Zhou, C.; Shen, X.; Liu, H. Investigation on deformation mechanisms of Zr-1Sn-0.3Nb-0.3Fe-0.1Cr alloy using in situ EBSD/SEM. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mat. 2024, 120, 106603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.