Synergistic Effects in Separation of Cobalt(II) and Lithium(I) from Chloride Solutions by Cyphos IL-101 and TBP

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ▪

- Exhibit the minimal solubility in the aqueous phase,

- ▪

- Extract selectively,

- ▪

- Enable repeated use,

- ▪

- Be stable in organic solvents or act as a solvent,

- ▪

- Ensure an appropriate extraction and re-extraction rate,

- ▪

- Not form stable emulsions,

- ▪

- Show low production cost,

- ▪

- Be non-toxic, non-flammable, non-carcinogenic, and biodegradable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

- ▪

- Trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium chloride (Cyphos IL 101, Cytec Industries Inc., Woodland, NJ, USA),

- ▪

- Tributylphosphate (TBP, 97%, Fluka, Everett, WA, USA),

- ▪

- The aqueous solution of 0.01 mol∙dm−3 CoCl2 ∙ 6H2O (cobalt(II) chloride, purity = 99%, POCh, Gliwice, Poland) and 0.01 mol∙dm−3 LiCl (lithium chloride, purity = 99%, POCh, Gliwice, Poland) (due to the preliminary nature of this study, a synthetic solution was used. Subsequently, the extraction studies will be conducted using the real solution after LiBs leaching).

- ▪

- Solutions of hydrochloric acid (HCl), sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and nitric acid (HNO3) (POCh, Gliwice, Poland). All reagents were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

2.2. Solvent Extraction

2.3. Stripping Experiments

3. Results

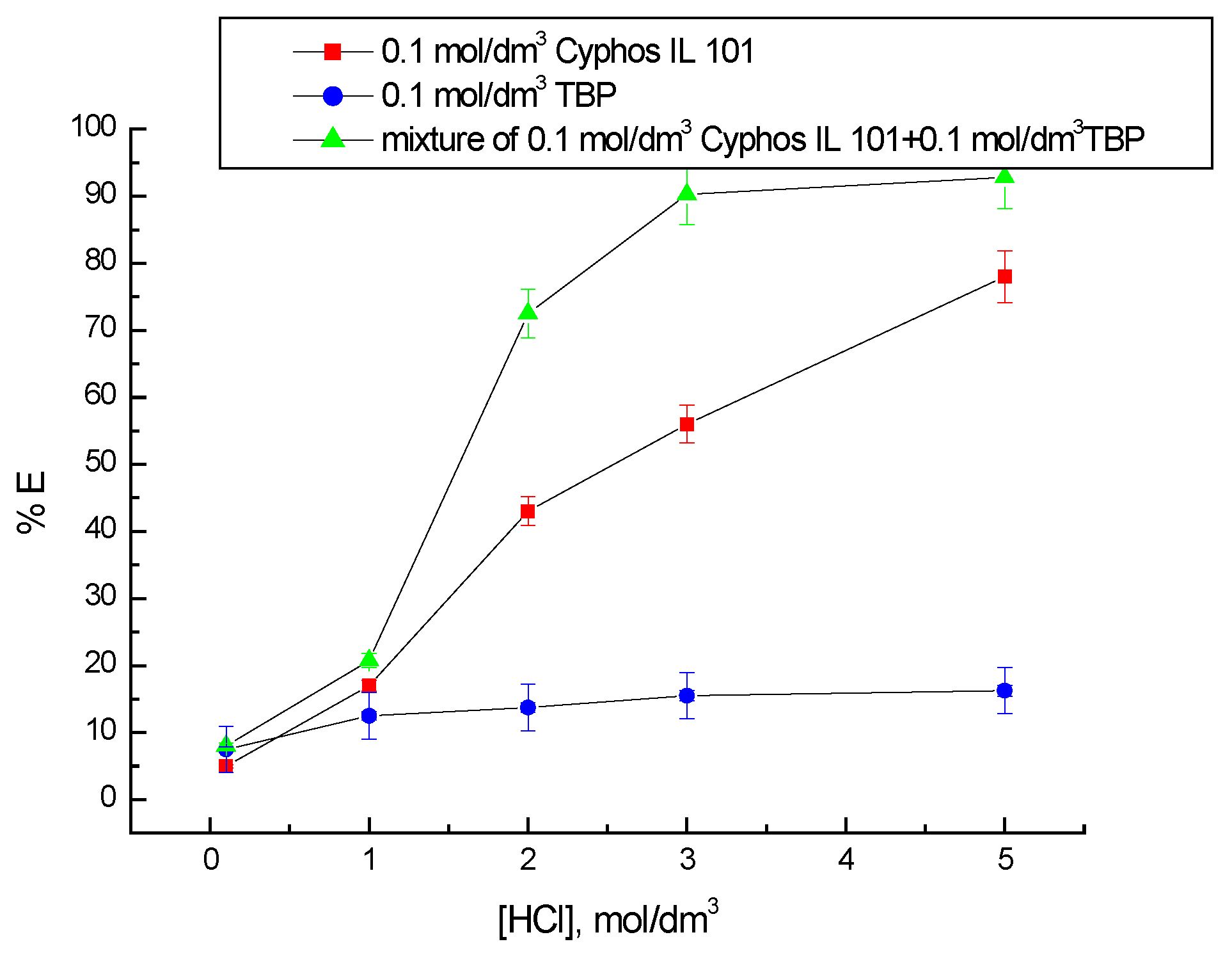

3.1. Cobalt(II) and Lithium(I) Extraction

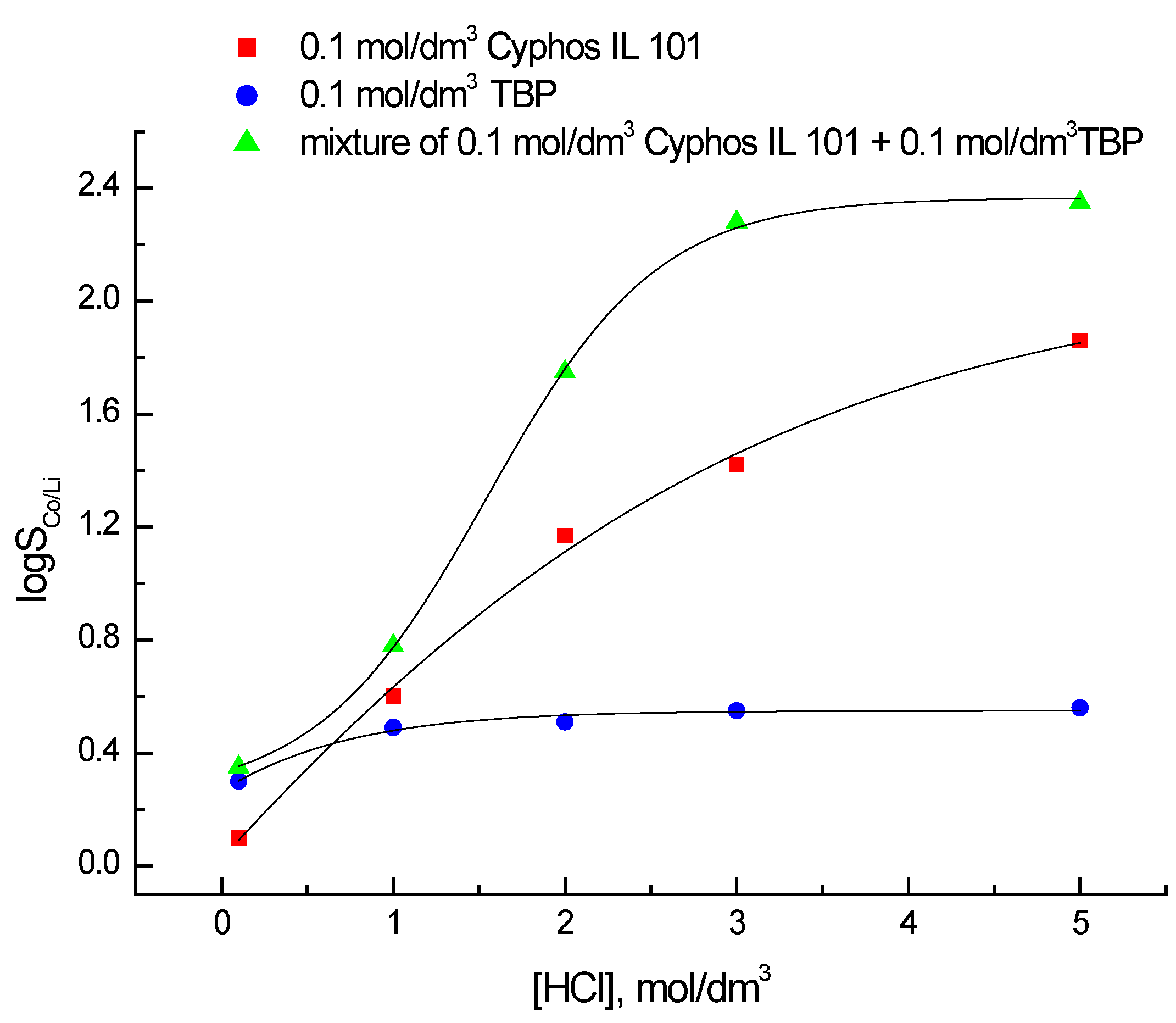

3.2. Selectivity of Co(II) and Li(I) Extraction with 0.1 M Cyphos IL 101 and 0.1 M TBP

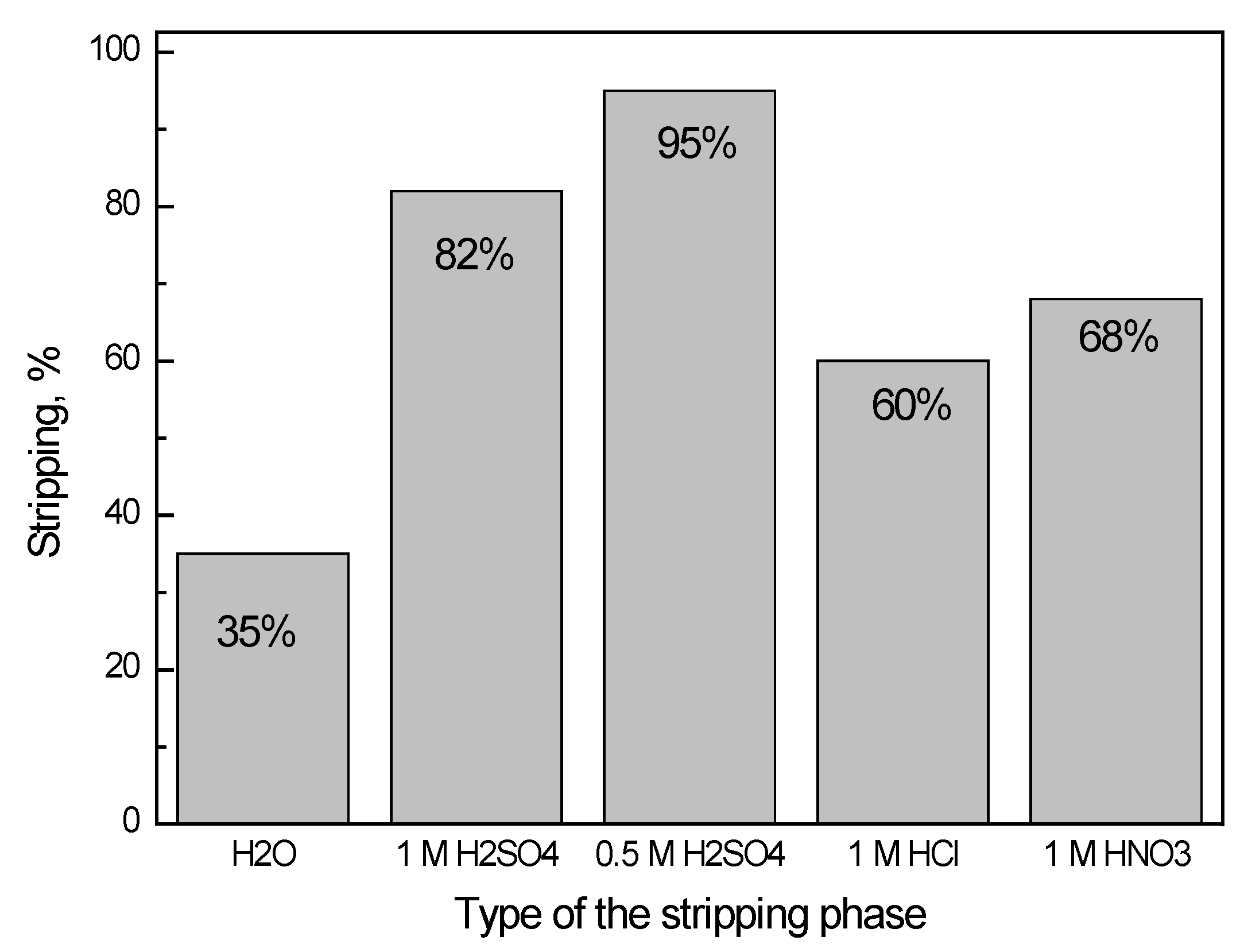

3.3. Stripping of Co(II) from Organic Phase

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cyphos IL 104 | Trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium bis-2,4,4(trimethylpentyl)phosphinate |

| Cyphos IL 101 | Trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium chloride |

| ILs | Ionic liquids |

| LIBs | Lithium-ion batteries |

| SX | Solvent extraction |

| TBP | Tributylphosphate |

References

- Dalini, F.A.; Karimi, G.H.; Goodarzi, M. A Review on environmental, economic and hydrometallurgical processes of recycling spent lithium-ion batteries. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2021, 42, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyawirawan, S.A.; Catrall, R.W.; Kolev, S.; Ines, M.; Almeida, G.S. Improving Co(II) separation from Ni(II) by solvent extraction using phosphonium-based ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 386, 121764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagnes, A.; Pospiech, B. A brief review on hydrometallurgical technologies for recycling spent lithium ion batteries. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 88, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giza, K.; Pospiech, B.; Gega, J. Future technologies for recycling spent lithium-ion batteries (libs) from electric vehicles—Overview of latest trends and challenges. Energies 2023, 16, 5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandl, M.M.; Lerchbammer, R.; Gerold, E. Bioleaching of lithium-ion battery black mass: A comparative study on gluconobacter oxydans and acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. Metals 2025, 15, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brožová, S.; Lisińska, M.; Saternus, M.; Gajda, B.; Martynková, G.S.; Slíva, A. Hydrometallurgical recycling process for mobile phone printed circuit boards using ozone. Metals 2021, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regel-Rosocka, M.; Alguacil, F.J. Recent trends in metals extraction. Rev. Metal. 2013, 49, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Senanayake, G.; Sohn, J.; Shin, S.M. Recovery of cobalt sulfate from spent lithium ion batteries by reductive leaching and solvent extraction with Cyanex 272. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 100, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olushola, S.A.; Folahan, A.A.; Alafara, A.B.; Bhekumusa, J.X.; Olalekan, S.F. Application of Cyanex extractant in cobalt/nickel separation process by solvent extraction. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2023, 8, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, P.K.; Panigrahi, S.; Sarangi, K.; Nathsarma, K.C. Separation of cobalt and nickel from ammoniacal sulphate solution using Cyanex 272. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 59, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Mohapatra, D. Process for cobalt separation and recovery in the presence of nickel from sulphate solutions by Cyanex 272. Met. Mater. Int. 2006, 12, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.N.; Deorkar, N.V.; Khopkar, S.M. Solvent extraction separation of cobalt(II) from nickel(II) and other metals with Cyanex 272. Talanta 1993, 40, 1535–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, B.K. Cobalt-nickel separation: The extraction of cobalt(II) and nickel(II) by Cyanex 301, Cyanex 302 and Cyanex 272. Hydrometallurgy 1993, 32, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickelton, W.A. Novel uses for thiophosphinic acids in solvent-extraction. JOM 1992, 44, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, J.S. Solvent extraction of cobalt and nickel by organophosphorus acids. Comparison of phosphoric, phosphonic and phosphinic acid systems. Hydrometallurgy 1982, 9, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreisinger, D.B.; Cooper, W.C. The solvent-extraction separation of cobalt and nickel using 2-ethylhexylphosphonic acid mono-2-ethylhexyl ester. Hydrometallurgy 1984, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, P.; Agarwal, N.; Abhilash. A review on assessment of ionic liquids in extraction of lithium, nickel, and cobalt vis-a-vis conventional methods. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 8321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.P.; Singh, R.K.; Chandra, S. Ionic liquids confined in porous matrices: Physicochemical properties and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 64, 73–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospiech, B.; Kujawski, W. Ionic liquids as selective extractants and ion carriers of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions utilized in extraction and membrane separation. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2015, 31, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybka, P.; Regel-Rosocka, M. Nickel(II) and cobalt(II) extraction from chloride solutions with quaternary phosphonium salts. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, M.; Markiewicz, A.; Regel-Rosocka, M. Hydrometallurgical separation of Co(II) from Ni(II) from model and real waste solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chen, C.; Fu, M.L. Separation of cobalt and lithium from spent lithium-ion battery leach liquors by ionic liquid extraction using Cyphos IL-101. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 197, 105439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospiech, B.; Chagnes, A. Highly selective solvent extraction of Zn(II) and Cu(II) from acidic aqueous chloride solutions with mixture of Cyanex 272 and Aliquat 336. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1302–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholico-Gonzales, D.; Chagnes, A.; Cote, G.; Avila-Rodriguez, M. Separation of Co(II) and Ni(II) from aqueous solutions by bis(2,4,4,-trimethylpentyl)phosphinic acid (Cyanex 272) using trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium chloride (Cyphos IL 101) as solvent. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 209, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospiech, B. Synergistic solvent extraction of Co(II) and Li(I) from aqueous chloride solutions with mixture of Cyanex 272 and TBP. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2016, 52, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, K.; Reddy, B.R.; Das, R.P. Extraction studies of cobalt(II) and nickel(II) from chloride solutions using Na-Cyanex 272. Separation of Co(II)/Ni(II) by the sodium salts of D2EHPA, PC88A and Cyanex 272 and their mixtures. Hydrometallurgy 1999, 52, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yokoyama, T.; Suzuki, T.M.; Inoue, K. The synergistic extraction of nickel and cobalt with a mixture of di(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid and 5-dodecylsalicylaldoxyme. Hydrometallurgy 2001, 61, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.B.; Nathsarma, K.C.; Chakravortty, V. Sodium salts of D2EHPA, PC-88A and Cyanex 272 and their mixtures as extractants for cobalt(II). Hydrometallurgy 1994, 34, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianowska, K.; Benke, G.; Goc, K.; Malarz, J.; Kowalik, P.; Leszczynska-Sejda, K.; Kopyto, D. Production of perrhenic acid by solvent extraction. Separations 2024, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, J.; Perrson, I. A study of the hydration of the alkali metal ions in aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lv, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, B.; Tang, S. Extraction performance and mechanism of TBP in the separation of Fe3+ from wet-processing phosphoric acid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 272, 118822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J.D.; Cox, M. Science and Practice of Liquid-Liquid Extraction; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Regel-Rosocka, M. Extractive removal of zinc(II) from chloride liquors with phosphonium ionic liquids/toluene mixtures as novel extractants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 66, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extractant | Full Chemical Name | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanex 272 | (bis(2,4,4,-trimethylpentyl)phosphinic acid) | [8,9,10,11,12,13,14] |

| Cyanex 301 | (bis(2,4,4,-trimethylpentyl)dithiophosphinic acid | [12,13,14] |

| Cyanex 302 | ((bis(2,4,4,-trimethylpentyl)monothiophosphinic acid | [12,13,14] |

| D2EHPA | (di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid | [15] |

| PC 88A | (2-ethylhexyl) phosphonic acid mono-2-ethylhexyl ester | [16] |

| Name of Compound | Abbreviation | Structural Formula |

|---|---|---|

| bis(2,4,4,-trimethylpentyl)phosphinic acid | Cyanex 272 |  |

| bis(2,4,4,-trimethylpentyl)dithiophosphinic acid | Cyanex 301 |  |

| bis(2,4,4,-trimethylpentyl)monothiophosphinic acid | Cyanex 302 |  |

| di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid | D2EHPA |  |

| 2-ethylhexyl phosphonic acid mono-2-ethylhexyl ester | PC88A |  |

| ILs | Full Chemical Name | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Cyphos IL 101 | trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium chloride [R4PCl], | [14,15,17] |

| Cyphos IL 104 | trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium bis 2,4,4(trimethylpentyl)phosphinate[R4PA] | [14,15] |

| [Cl−], mol∙dm−3 | Co2+ | CoCl+ | CoCl2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 27.4 | 33.0 | 6.97 | 1.33 | 31.30 |

| 2.0 | 4.28 | 10.4 | 4.28 | 1.90 | 79.14 |

| 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.46 | 1.42 | 1.96 | 96.16 |

| 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 99.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pospiech, B. Synergistic Effects in Separation of Cobalt(II) and Lithium(I) from Chloride Solutions by Cyphos IL-101 and TBP. Metals 2026, 16, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020165

Pospiech B. Synergistic Effects in Separation of Cobalt(II) and Lithium(I) from Chloride Solutions by Cyphos IL-101 and TBP. Metals. 2026; 16(2):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020165

Chicago/Turabian StylePospiech, Beata. 2026. "Synergistic Effects in Separation of Cobalt(II) and Lithium(I) from Chloride Solutions by Cyphos IL-101 and TBP" Metals 16, no. 2: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020165

APA StylePospiech, B. (2026). Synergistic Effects in Separation of Cobalt(II) and Lithium(I) from Chloride Solutions by Cyphos IL-101 and TBP. Metals, 16(2), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020165