Abstract

This study evaluated the damage behavior of 321 austenitic stainless steel under tensile loading by measuring its magnetic properties. The results indicate that, at room temperature, the magnetic properties of 321 stainless steel respond distinctly to mechanical loading. Changes under external stress are primarily attributed to the phase transformation from austenite to martensite. Both coercive force and magnetic Barkhausen noise effectively characterize this material’s deformation and phase transformation processes: the coercive force dynamics curve exhibits an initial rise, followed by a decline with a decrease during the specimen’s necking stage. Magnetic Barkhausen noise is highly sensitive to stress changes, especially during the elastic stage. In situ measurements show that, at a stress of 300 MPa, the magnetic Barkhausen noise peak voltage signal reaches 0.060 V, which is a 100.0% increase compared to the original specimen (0.030 V). Therefore, when assessing the stress state and damage of stainless steel using coercive force and magnetic Barkhausen noise techniques, attention should be paid to the inflection characteristics of the coercive force dynamic curve and the inflection points in the peak values of the magnetic Barkhausen noise voltage signal. These features can be used to effectively monitor crack initiation and propagation in austenitic stainless steel.

1. Introduction

Steel is an indispensable material that has played a vital role in human civilization for millennia. As a fundamental material for modern industry, the steel sector will continue to be a critical foundation for societal development in the foreseeable future [1,2]. 321 stainless steel is a representative Ni-Cr-Ti austenitic stainless steel. Due to its excellent corrosion resistance, exceptional high-temperature strength and oxidation resistance, as well as excellent machinability and weldability, it is widely used in critical sectors vital to the national economy, people’s livelihoods, and strategic security. These sectors include energy, chemical engineering, aerospace, and nuclear industries [3,4,5].

As a critical engineering material, 321 stainless steel components frequently endure cyclic and static loads, as well as the combined effects of these loads, during service. This leads to continuous microstructural evolution and degradation of mechanical properties, resulting in the gradual accumulation of damage. Failure to promptly identify and assess such damage may trigger plastic instability, fatigue crack initiation, or sudden fracture, which can lead to severe safety incidents and economic losses [6,7]. When applied loads exceed the material’s yield strength, components undergo plastic deformation, which is manifested as elongation, compression, bending, or torsion. This irreversible deformation is a critical mechanism for potential failure. Therefore, given the extensive use of 321 stainless steel in critical equipment, investigating its damage evolution mechanisms in depth and establishing effective damage assessment methods are of significant engineering importance for the timely detection of potential risks and ensuring structural safety.

Research indicates that the accumulation of damage invariably accompanies crack initiation and propagation processes, primarily manifesting as fatigue fracture and tensile fracture, and is unaffected by load type [8]. The initiation stage of fatigue cracks can be analogized to the localized instability phenomenon that occurs when material enters the “necking” stage during tensile loading. Because material evolution induced by mechanical loading is irreversible and persists after unloading, a stress–damage correlation model based on coercive force and magnetic Barkhausen noise signals can be constructed by integrating microstructural characterization with non-destructive testing methods.

Early damage detection in austenitic stainless steel is challenging because damage often originates and evolves at the microscopic scale. Meanwhile, macroscopic mechanical properties (such as yield and tensile strength) exhibit minimal change during the initial stages of damage, making them poor indicators of the material’s “health status” [9]. By the time macroscopic properties show noticeable degradation, substantial damage has typically accumulated within the material, often rendering intervention too late. Traditional non-destructive testing techniques (NDTs), such as ultrasonic, radiographic, and penetrant testing, primarily target millimeter-scale defects and have limited capability to identify damage at the micrometer or nanometer scale (e.g., dislocation cells, slip bands, and microvoids) [10,11]. Therefore, exploring physical parameters sensitive to microdamage evolution that enable early warning and establishing quantitative correlations between these parameters and macroscopic performance degradation or structural state has become a key research direction in this field [8,12].

The macroscopic mechanical behavior of materials is essentially an external manifestation of their microstructural evolution. Austenitic stainless steel initially has a metastable face-centered cubic structure. When subjected to external loading, particularly plastic deformation, the microstructure undergoes a series of complex transformations, including dislocation proliferation, migration, and entanglement. These transformations lead to the formation of dislocation walls and cellular structures. Further deformation may induce a martensitic transformation, in which the formation of strain-induced martensite is a critical turning point in the evolution of material properties. Concurrently, significant changes occur in grain morphology, texture, and grain boundary distribution [13,14]. These microstructural evolutions directly govern the material’s hardening behavior, ductile-to-brittle transition characteristics, and crack resistance. Therefore, systematically investigating the dynamic microstructural evolution of austenitic stainless steel under loading is essential for understanding its damage mechanisms, such as pit and crack initiation.

Of the many physical properties sensitive to micro-damage, the magnetic characteristics of materials are particularly notable. By detecting minute changes in the magnetic field at the surface of a material, one can effectively reflect its internal stress distribution state [13,15]. Coercive force (Hc, A/cm) and magnetic Barkhausen noise are key magnetic response parameters that exhibit high sensitivity to microstructural obstacles in steel, such as dislocation density, precipitation phases, grain boundaries, and microstresses [16,17]. For example, Shen et al. [15] employed coercivity and magnetic Barkhausen noise as core diagnostic parameters to investigate the evolution of microstructures, including dislocations, precipitates, and voids, in 12Cr1MoVG steel. This confirmed that these magnetic signatures can effectively assess material damage levels. Mitra et al. [17] employed hysteresis loop and magnetic Barkhausen noise techniques to analyze the creep behavior of modified 9Cr-1Mo steel deeply, achieving correlation modeling between microstructure and magnetic parameters across different creep stages. This magnetic signal-based detection method identifies early-stage stress accumulation and enables qualitative and quantitative defect analysis, demonstrating significant potential for engineering applications [8,18].

Pure austenitic stainless steel is theoretically paramagnetic with very low magnetic permeability. However, martensite, which is typically a ferromagnetic phase induced by plastic deformation, significantly alters the material’s magnetic response. As deformation increases, the martensite content rises continuously, resulting in a fundamental shift in the material’s overall magnetization behavior. Coercive force, a magnetic parameter highly sensitive to internal stresses and defects, varies with the volume fraction of ferromagnetic phases (e.g., martensite) and depends on the pinning effect of microdefects (e.g., dislocations, grain boundaries, and phase interfaces) on domain wall motion [13,19]. Even during the early stage of plastic deformation without a pronounced martensitic phase transformation, an increased dislocation density and the formation of dislocation cell structures strongly impede the irreversible motion of magnetic domain walls. This leads to a significant enhancement in both coercive force and magnetic Barkhausen noise signals. Therefore, coercive force and magnetic Barkhausen noise are expected to constitute a highly sensitive “damage indicator” capable of tracking the entire damage evolution process, from dislocation accumulation and phase transformation to microcrack nucleation.

Previous studies have established corresponding magneto-mechanical models [20,21] based on the characteristic of austenitic stainless steel to induce magnetization due to martensitic phase transformation during deformation [22,23,24]. These models achieve quantitative correlations between stress and magnetic signals. Further investigations indicate that quantitative relationships can be established between changes in coercive force within deformed materials and both static loading stress [25] and cyclic stress [26,27] by systematically analyzing these changes. Wang et al. [1] further revealed the intrinsic connection between coercive force and dislocation density during the plastic deformation of low-carbon steel. However, this work remains qualitative and has not yet achieved a quantitative description.

The objective of this study is to establish a quantitative correlation between stress state, microscopic magnetic signals, and microstructural damage in metastable austenitic stainless steel 321 under tensile loading. This study integrates online monitoring techniques for coercive force and magnetic Barkhausen noise with scanning electron microscopy (SEM)/energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EBSD) microstructural characterization to systematically analyze the evolution of magnetic signals and microstructural damage during different stress stages. Different stresses are applied to detect and analyze the magnetic signal response of austenitic stainless steel and correlate it with its damage state. These findings lay the groundwork for magnetism-based non-destructive testing and in-service condition monitoring of structural components.

2. Testing Process

2.1. Test Materials and Equipment

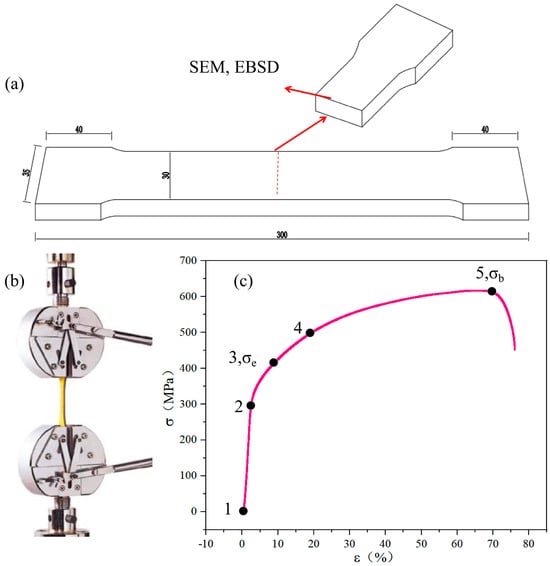

This study used commercially available 321 austenitic stainless steel for the experiment. Its specific chemical composition and measured tensile properties are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. The tensile specimens were prepared and tested strictly in accordance with the ASTM E8/E8M—Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA) [28]. The tensile specimens were fabricated into plate-like structures with an effective gauge length of 210 mm × 30 mm × 5 mm, as illustrated in Figure 1a. Tensile testing was conducted on a universal testing machine (Figure 1b), yielding the engineering stress–strain curves shown in Figure 1c. To systematically investigate how different stress levels influence the material’s magnetic response, multi-level tensile loads were applied to the specimens. Magnetic signal measurements were conducted synchronously at each predetermined load level; the specific stress values applied are listed in Table 3. To ensure data reliability, the magnetic signals at each stress state underwent three repeated measurements, and the average value was taken.

Table 1.

The chemical composition of 321 stainless steel.

Table 2.

The tensile properties of 321 stainless steel.

Figure 1.

Schematic of tensile test: (a) Tensile specimen, mm; (b) Tensile testing machine; (c) Stress–strain curve and load corresponding to magnetic signal measurement points.

Table 3.

Values of stress corresponding to Magnetic Signal Measurements.

2.2. Microstructural Observation

To investigate the damage evolution mechanism of 321 stainless steel, we sampled, ground, polished, and etched it. The specimens were then etched using a corrosion solution consisting of 20 vol% HNO3, 10 vol% HCl, and 70 vol% H2O. We examined the microstructure of the specimen cross-sections using metallographic and scanning electron microscopy. Then, electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) testing was performed using a field emission scanning electron microscope.

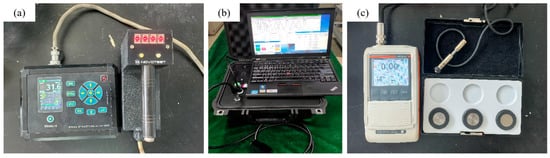

2.3. Non-Destructive Evaluation

As shown in Figure 2, this study used a coercive force tester (MA-WF-05, Novotest, Kharkov, Ukraine) and a multifunctional, non-destructive, micro-magnetic testing instrument (DYM-N2, Central Iron & Steel Research Institute, Beijing, China) to characterize the material’s magnetic properties. The coercive force tester system includes hardware and software components. The hardware includes a current source, an analog-to-digital converter, and a microcontroller integrated with a measurement unit containing a magnetizing coil and an induction sensor. The multifunctional micro-magnetic non-destructive testing instrument primarily comprises a system host, micro-magnetic detection sensors, and a control computer. The volume fraction variation of the ferromagnetic phase (α-Fe) in austenitic steel was also determined using a ferrite measurement instrument (Feritscope-FMP30, Helmut Fischer, Bad Säckingen, Germany).

Figure 2.

Magnetic measurement instruments: (a) coercive force Tester; (b) Multifunctional Micro-Magnetic Non-Destructive Testing Instrument; (c) Ferrite Tester.

3. Results and Analysis

At room temperature, 321 stainless steel has a face-centered cubic crystal structure and a microstructure consisting primarily of paramagnetic austenite. Under external loading, however, austenite may undergo a strain-induced martensitic transformation, forming a ferromagnetic, body-centered cubic α′ martensite structure. This irreversible transformation process causes the material’s overall magnetic properties to gradually shift from paramagnetic to ferromagnetic [8]. Thus, when analyzing damage evolution in localized regions of materials during operation, the intrinsic relationship between magnetic properties and damage accumulation in austenitic stainless steel can be systematically investigated by measuring magnetic parameters such as martensite content, coercive force, and magnetic Barkhausen noise.

3.1. Effect of Stress on the Microstructure of 321 Stainless Steel

3.1.1. Metallographic Analysis

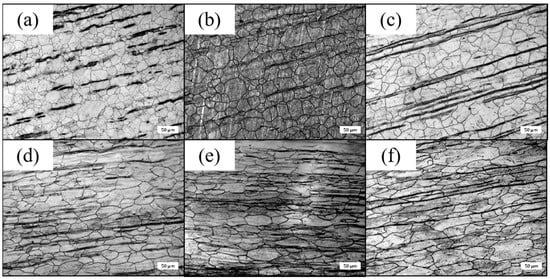

Figure 3 shows the microstructure of 321 stainless steel under different tensile stress stages. Figure 3a shows that the initial state exhibits a relatively uniform distribution of austenite grain sizes that present irregular polygonal shapes. During elastic deformation, the grain morphology shows no significant change and maintains its original geometric characteristics (Figure 3b). Once the yield strength is exceeded and the plastic stage is reached, significant plastic flow traces appear within the grains. The grains elongate or flatten along the tensile direction and are segmented by slip bands, forming fine substructures. This phenomenon originates from the proliferation and slip motion of dislocations during plastic deformation. This prompts grains to adjust their shapes to accommodate external loads (Figure 3d). Additionally, martensitic phases with different orientations are observable in the specimen after plastic deformation. As stress increases, the deformation-induced martensitic transformation intensifies. During the necking stage, grains undergo extreme elongation and take on a more “fibrous” or “streamlined” appearance. This indicates that the material has entered a significant hardening phase and is approaching instability [18], as shown in Figure 3e. Ultimately, fracture occurs at the point of most severe necking. Near the fracture surface, the microstructure exhibits extreme elongation, as shown in Figure 3f.

Figure 3.

Metallographic microstructure of 321 stainless steel after unloading from different tensile stresses: (a) 0 MPa; (b) 300 MPa; (c) 430 MPa; (d) 610 MPa; (e) necking stage; (f) fracture stage.

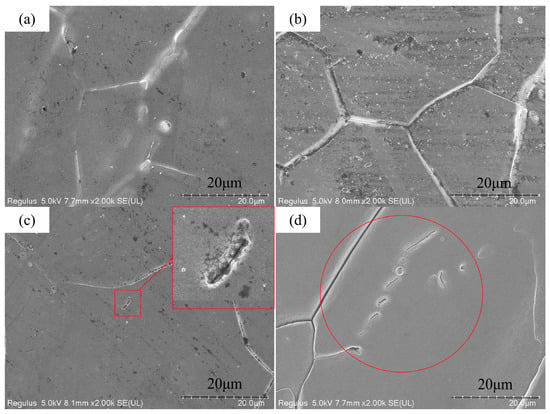

3.1.2. Microstructures Observation by SEM

Figure 4 shows the scanning electron microscope (SEM) microstructure of the 321 stainless steel specimen at different stages of tensile stress. As tensile deformation progresses, observations reveal that grain boundaries exhibit increased contrast due to differential corrosion (Figure 4b). This is accompanied by the nucleation (Figure 4c) and subsequent expansion (Figure 4d) of micro-pores. Under tensile stress, numerous dislocations within grains move along slip systems. Because grain boundaries are regions of abrupt crystal orientation change, they impede dislocation slip. This causes dislocations to pile up before the boundaries and form “dislocation pile-ups.” During plastic deformation, these pile-ups increase stored energy and localize strain in these regions. This makes them more susceptible to subsequent corrosion, which manifests as significantly widened grain boundary contrast in SEM images. These phenomena suggest that intragranular dislocation slip is activated early in the plastic deformation process.

Figure 4.

SEM observations of 321 stainless steel after unloading from different tensile stresses: (a) 0 MPa; (b) 300 MPa; (c) 430 MPa; (d) 610 MPa.

Additionally, austenitic stainless steel has a face-centered cubic structure and many active slip systems, which gives it excellent plasticity. Under tensile stress, dislocation motion and packing can create microvoids within grains, especially around second-phase particles, such as inclusions, or dislocation tangles. As deformation continues, these microvoids gradually grow and interconnect, ultimately resulting in material fracture.

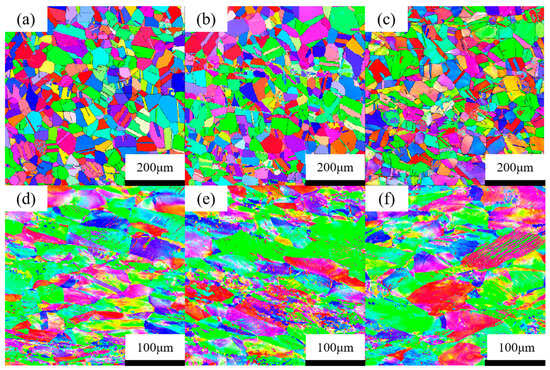

3.1.3. Microstructures Observation by EBSD

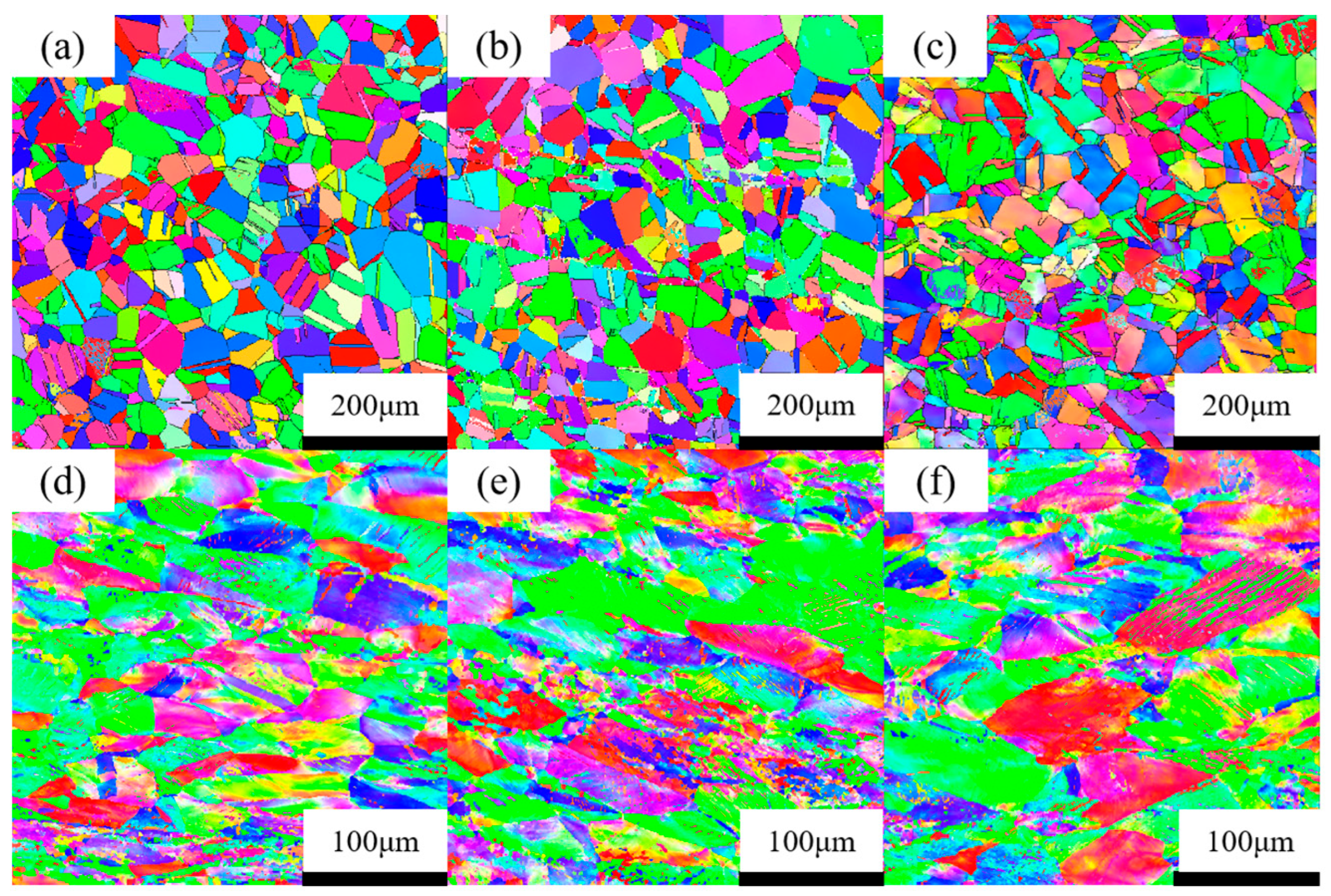

EBSD testing was performed on the as-received specimen, as well as on specimens subjected to varying tensile stresses. The resulting inverse polar figures (IPFs) are shown in Figure 5. When 321 stainless steel was stretched into the plastic stage (Figure 5c), a distinct color gradient appeared within the grains compared to the as-received specimen (Figure 5a), indicating an increase in local orientation gradients. This trend became more pronounced as strain increased. The continuous color transition within grains reflects the fact that, as plastic damage accumulates, the orientation distribution within grains tends to diverge. Local regions undergo lattice rotation, forming substructures and introducing orientation differences.

Figure 5.

Inverse Polarization Figure (IPF) of 321 stainless steel after unloading from different tensile stresses: (a) 0 MPa; (b) 300 MPa; (c) 430 MPa; (d) 610 MPa; (e) necking stage; (f) fracture stage.

Additionally, as tensile stress increases, the image quality of IPF maps obtained via EBSD gradually declines, a phenomenon evident even during the initial stage of plastic deformation (Figure 5c). As tensile stress approaches the material’s ultimate tensile strength (610 MPa, Figure 5d), the EBSD calibration rate decreases significantly. This is primarily due to the generation of microdefects (e.g., microvoids and microcracks), which degrade crystal diffraction signals and increase the difficulty of orientation calibration. These results are consistent with those reported in the literature [1,16].

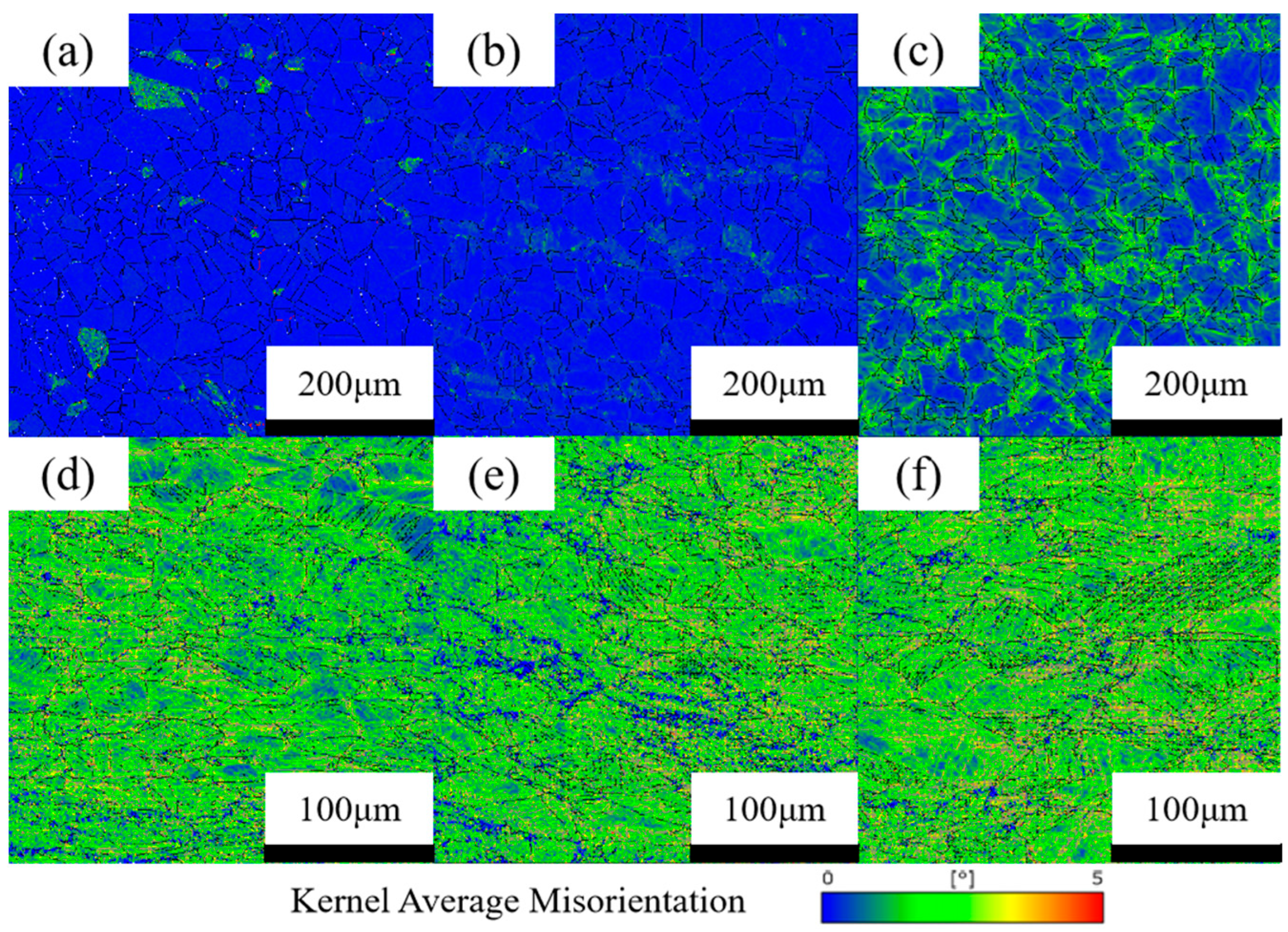

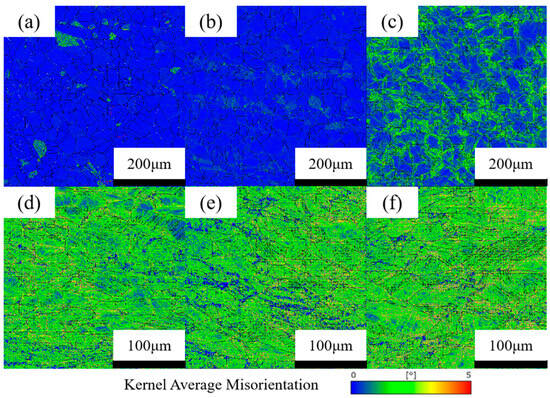

Figure 6 shows the kernel average misorientation (KAM) distribution of the original specimen and specimens subjected to different tensile stresses. KAM effectively characterizes the degree of local lattice distortion [29]. As shown in Figure 6c, when tensile stress reaches the yield strength of 430 MPa, the KAM value increases significantly. This indicates the formation of distinct local orientation gradients within grains; i.e., lattice rotation has occurred. KAM values are generally recognized as being closely related to dislocation density. Higher KAM values reflect stronger local plastic strain and correspond to increased dislocation density within grains and intensified lattice bending.

Figure 6.

Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) of 321 stainless steel after unloading from different tensile stresses: (a) 0 MPa; (b) 300 MPa; (c) 430 MPa; (d) 610 MPa; (e) necking stage; (f) fracture stage.

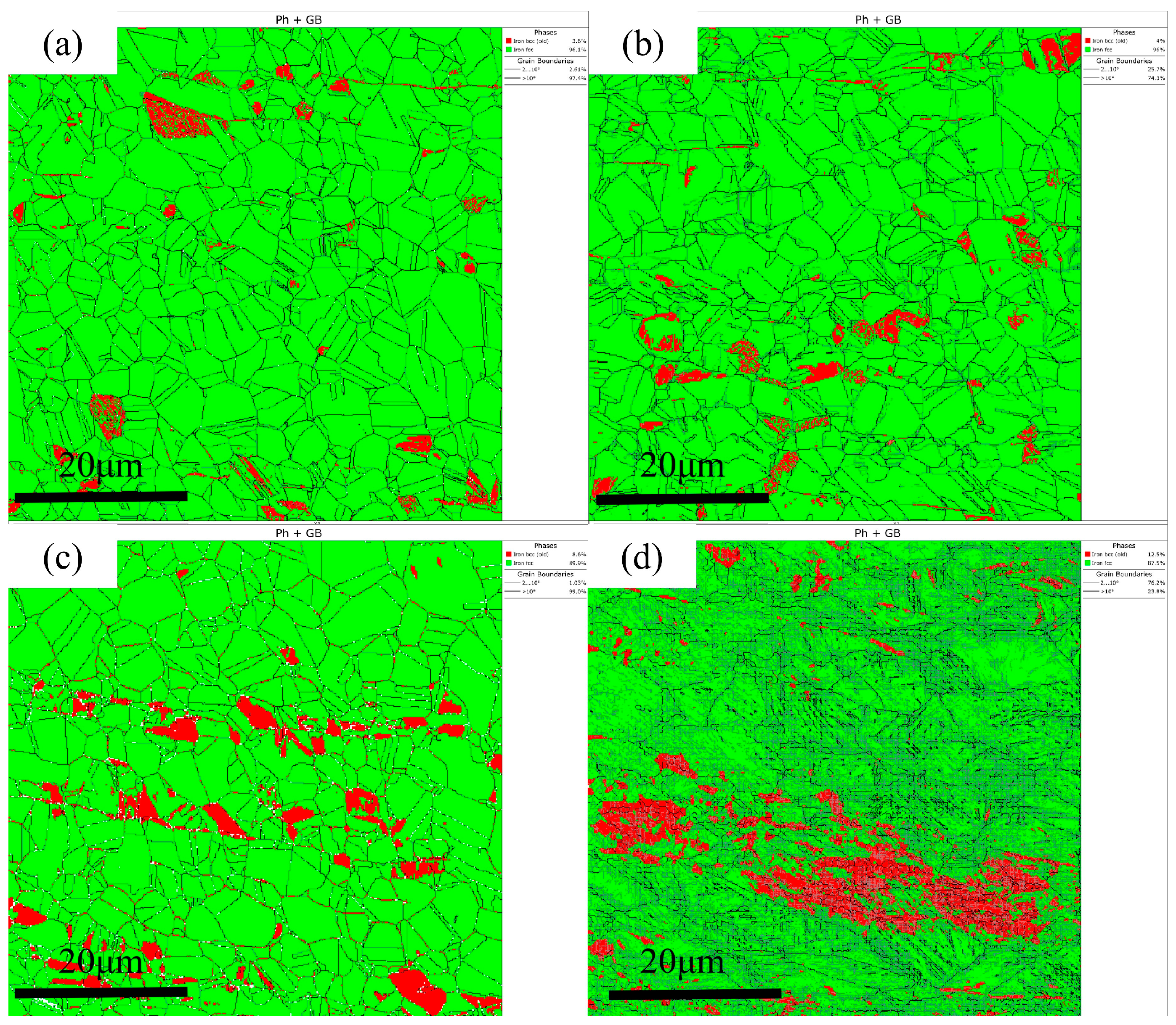

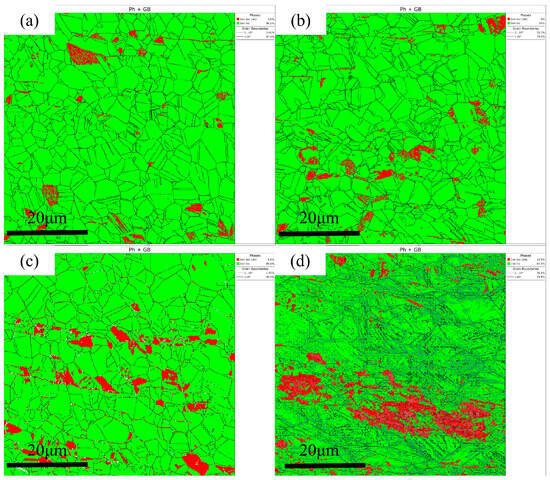

Figure 7 shows the Ph + GB diagram of 321 stainless steel under different tensile stresses (between 0 MPa and 610 MPa). It reveals a clear trend in martensite content. Even without applied tensile stress (0 MPa), a small amount of martensite (3.6%) is present in the material, likely originating from localized strain in the original microstructure or processing history. As the tensile stress increased to 300 MPa, the martensite content increased slightly, reaching 4%. This indicates that, at this stage, stress had not yet triggered significant phase transformations; deformation was likely still dominated by slip and twinning. When the stress increased further to 430 MPa, the martensite content increased markedly to 8.6%, indicating that the stress had exceeded the critical threshold for inducing martensitic transformation. Strain-induced martensitic transformation (SIMT) then began to occur significantly. This phenomenon is closely related to the metastable characteristics of austenitic stainless steel. Under stress, a portion of the austenite transforms into α′-martensite via a shear mechanism, which enhances the material’s strength and hardening capacity. When the stress reached 610 MPa, the martensite content increased further to 12.5%. At room temperature, the formation of additional martensite resulting from sustained plastic deformation induced by tensile stress has a more pronounced strengthening effect on the phase transformation.

Figure 7.

Ph + GB diagrams of 321 stainless steel after unloading from different tensile stresses: (a) 0 MPa; (b) 300 MPa; (c) 430 MPa; (d) 610 MPa.

In summary, this study uses multi-scale characterization, including metallography, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD)-based IPF, KAM, and Ph + GB analyses, to systematically elucidate the microstructural evolution and damage mechanisms in 321 stainless steel during tensile deformation. As loading increases, the material exhibits the following features: During the initial plastic deformation stage, dislocation slip and stacking faults dominate grain deformation, slip band formation, and strain localization at grain boundaries. Further loading induces a martensitic phase transformation in the deformed structure concurrently with the nucleation and propagation of microvoids within the grains, particularly at interstitial phases or dislocation entanglements. EBSD, IPF, and KAM analyses collectively indicate that increasing strain leads to a significant rise in local orientation gradients within grains, a continuous increase in dislocation density, and intensified lattice distortion. The decline in image quality and calibration rate visually reflects the accumulation of microdefects. These multi-scale findings demonstrate that plastic damage and ultimate failure in 321 stainless steel result from the interaction of multiple mechanisms—dislocation slip, deformation-induced martensitic transformation, microvoid evolution, and connectivity—across macro-, micro-, and nanoscales.

3.2. Effect of Stress on the Magnetic Properties of 321 Stainless Steel

3.2.1. Effect of Stress on the Ferromagnetic Phase in 321 Stainless Steel

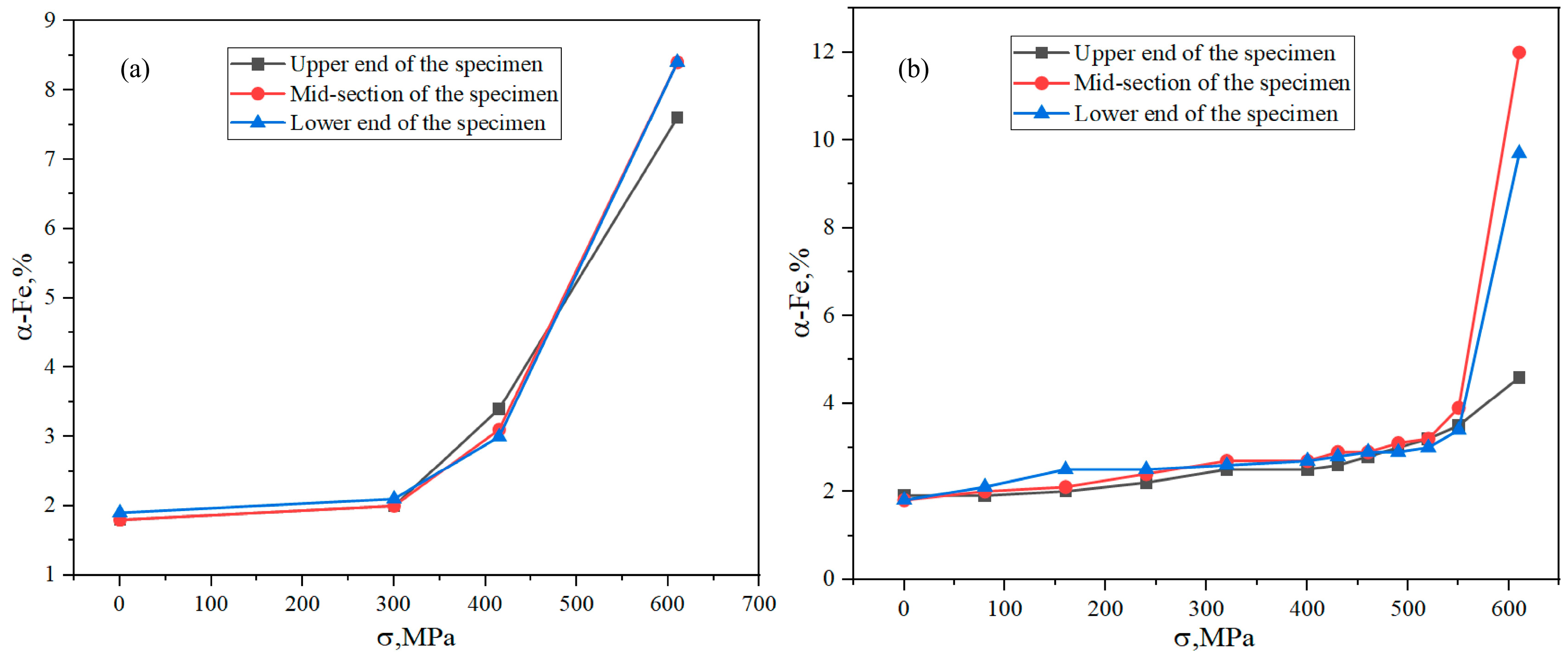

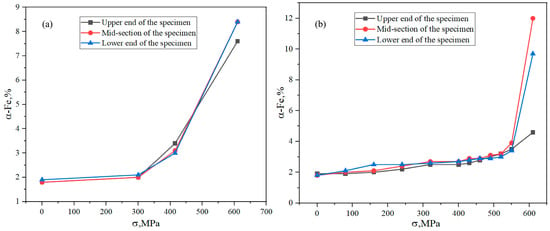

Figure 8 illustrates the variation in ferromagnetic phase (α′ martensite) content in specimens subjected to different tensile stresses. Figure 8a shows measurements taken after unloading, while Figure 8b shows in situ measurements taken during loading. Under both conditions, the ferromagnetic phase fraction increases with rising tensile stress. These results indicate that a pronounced strain-induced martensitic transformation occurs in 321 stainless steel under tensile loading, leading to a gradual increase in ferromagnetic phase content. These findings provide direct microstructural evidence for damage assessment based on magnetic signals.

Figure 8.

Variation in ferromagnetic phase percentage under different stresses: (a) unloading measurement; (b) in situ measurement.

As shown in Figure 8, when tensile stress remains below the yield strength of 430 MPa, the ferrite phase content undergoes gradual changes. Once stress reaches the yield strength, the ferrite phase content increases significantly, indicating that deformation-induced martensitic transformation has entered an active stage. After unloading, the ferrite phase content in the specimen increased from 1.8% to 2.8%, a relative increase of approximately 55.6%. Meanwhile, the ferromagnetic phase content reached 3.1% under in situ loading conditions, further validating the stress-promoted effect on phase transformation. This trend aligns with the phase distribution results from EBSD (Ph + GB) analysis in Figure 7. Additionally, the martensitic transformation volume was notably higher in the middle and lower regions of the specimen, indicating non-uniform plastic strain distribution spatially during tensile loading.

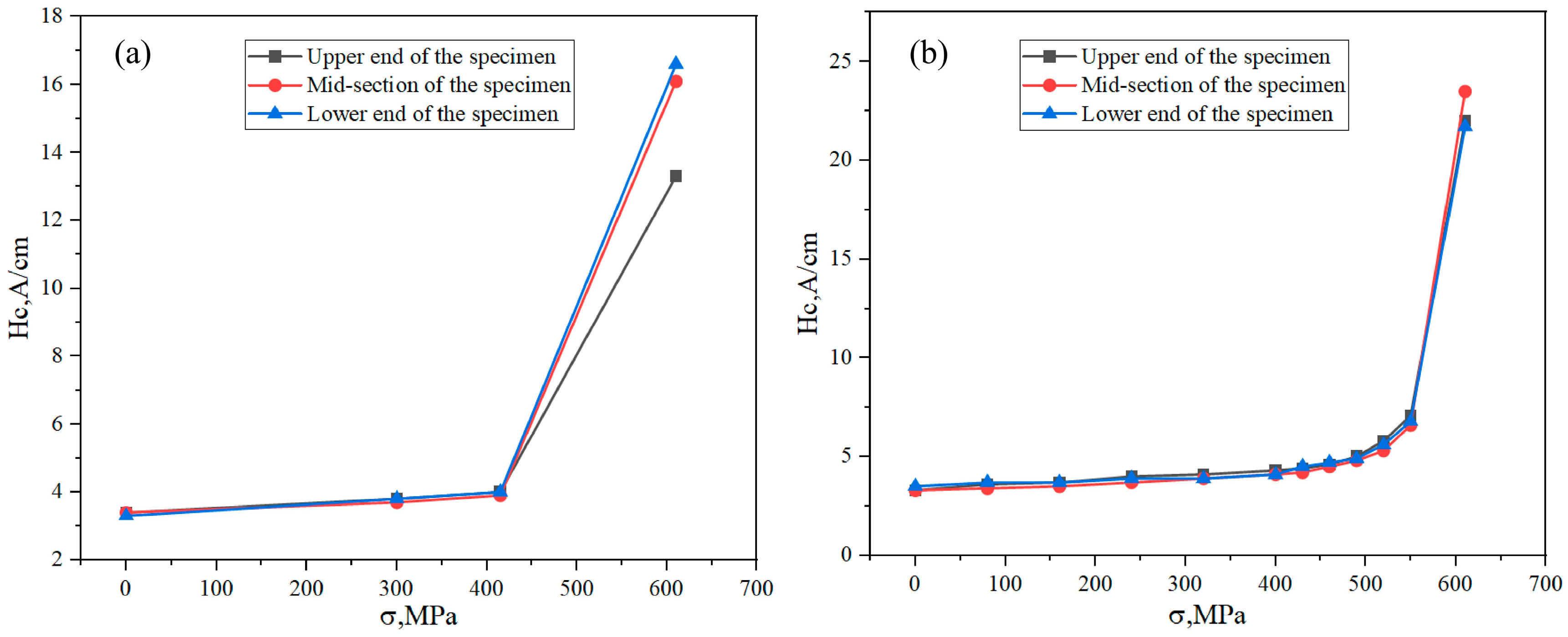

3.2.2. Effect of Stress on the Coercive Force (Hc) of 321 Stainless Steel

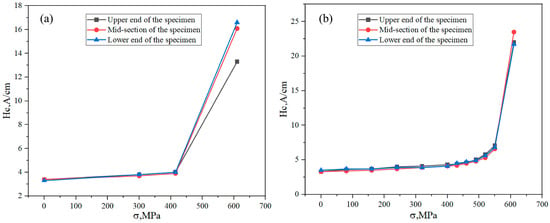

Figure 9 shows how the hardness of 321 austenitic stainless steel changes with different tensile stresses. It includes results from in situ testing during loading and unloading. The hardness change trends are consistent under both conditions and align with the α′-martensite (ferromagnetic phase) evolution pattern (Figure 8). Within the material’s tensile strength range, coercive force increases monotonically with rising tensile stress, with a particularly significant increase observed beyond the yield strength. When tensile stress reaches 300 MPa under loading conditions, the hardness increases to approximately 4.0 A/cm. This represents a 21.2% increase from the initial state of 3.3 A/cm. As stress increases to the yield strength of 430 MPa, hardness further increases to approximately 4.4 A/cm, which is a cumulative increase of 33.3%. These changes indicate that, as plastic deformation progresses, the increase in defect density (e.g., dislocations) within the material, coupled with the martensitic phase transformation, enhances the pinning effect of magnetic domain walls.

Figure 9.

Variation in coercive force under different stress conditions: (a) unloading measurement; (b) in situ measurement.

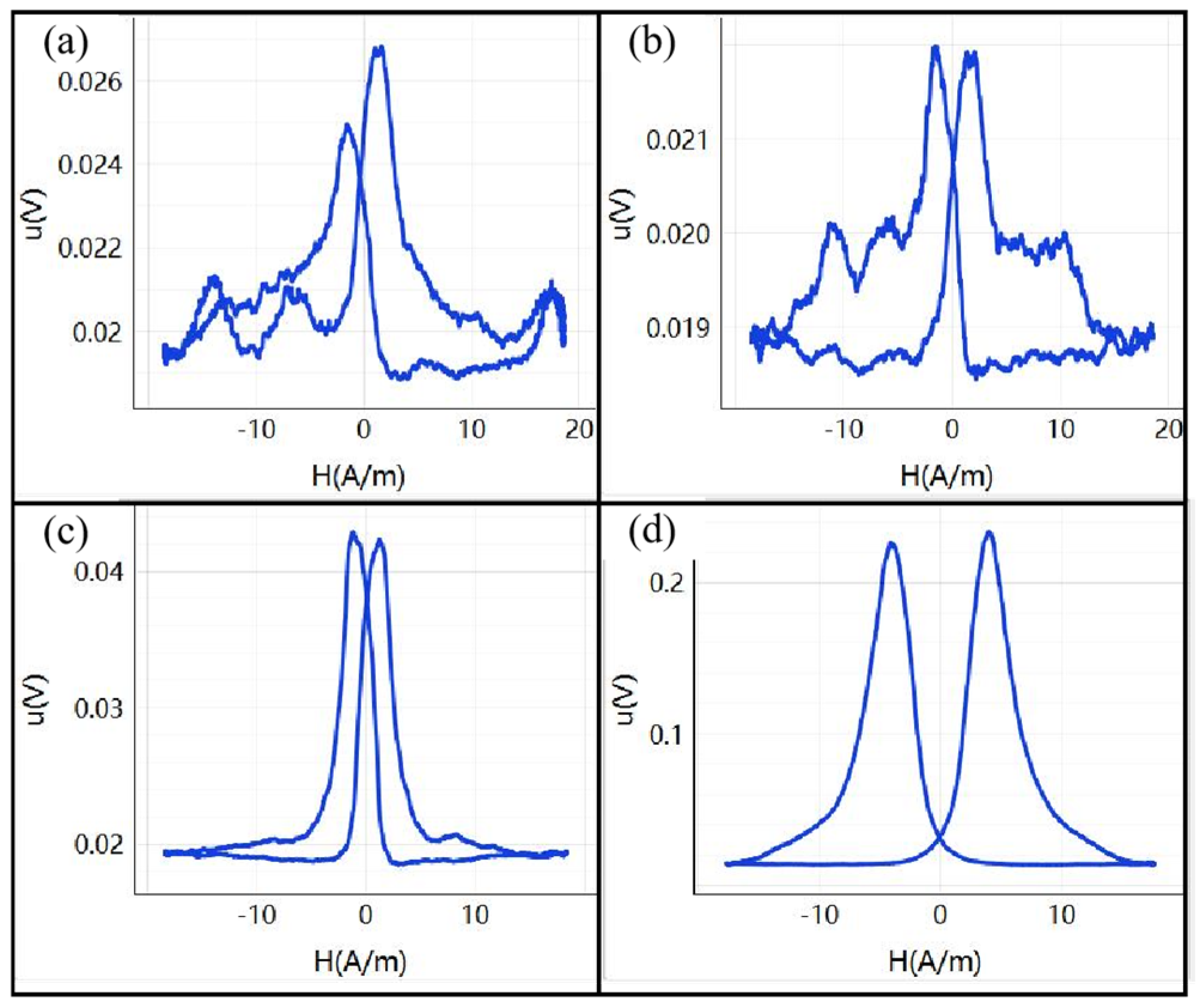

3.2.3. Effect of Stress on Magnetic Barkhausen Noise (MBN)

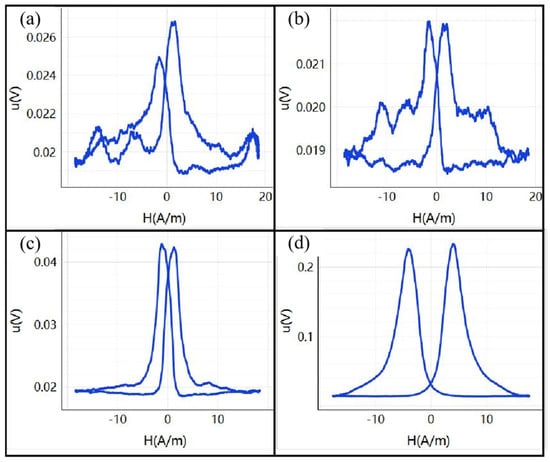

Figure 10 shows the magnetic Barkhausen noise (MBN) and tangential magnetic field strength versus voltage signals for 321 stainless steel specimens after unloading at various tensile stress levels. During the elastic stage, which occurs below the yield strength of 430 MPa, the MBN voltage amplitude varies minimally compared to the original specimen. Upon reaching the yield strength of 430 MPa, the maximum MBN voltage amplitude increased to 0.042 V (Figure 10c), which is approximately 55.6% higher than the original specimen’s amplitude of 0.027 V (Figure 10a). As loading continued to the tensile strength (610 MPa), the voltage amplitude increased sharply to 0.230 V (Figure 10d), which is approximately 8.5 times the original amplitude. As plastic strain accumulated, the MBN signal amplitude increased significantly, and its distribution characteristics underwent noticeable changes. These changes reflect enhanced magnetic domain pinning behavior within the material driven by increased dislocation density, deformation-induced martensitic phase transformation, and the resulting evolution of magnetic properties. An increased dislocation density due to tensile deformation enhances the pinning of magnetic domain walls. This shifts the material’s magnetic properties toward a “harder magnetic” state, causing an increase in coercivity, a decrease in magnetic permeability, and a rise in hysteresis loss.

Figure 10.

MBN tangential magnetic field strength versus voltage signal for 321 stainless steel after unloading from different stress levels during tensile testing: (a) 0 MPa; (b) 300 MPa; (c) 430 MPa; (d) 610 MPa.

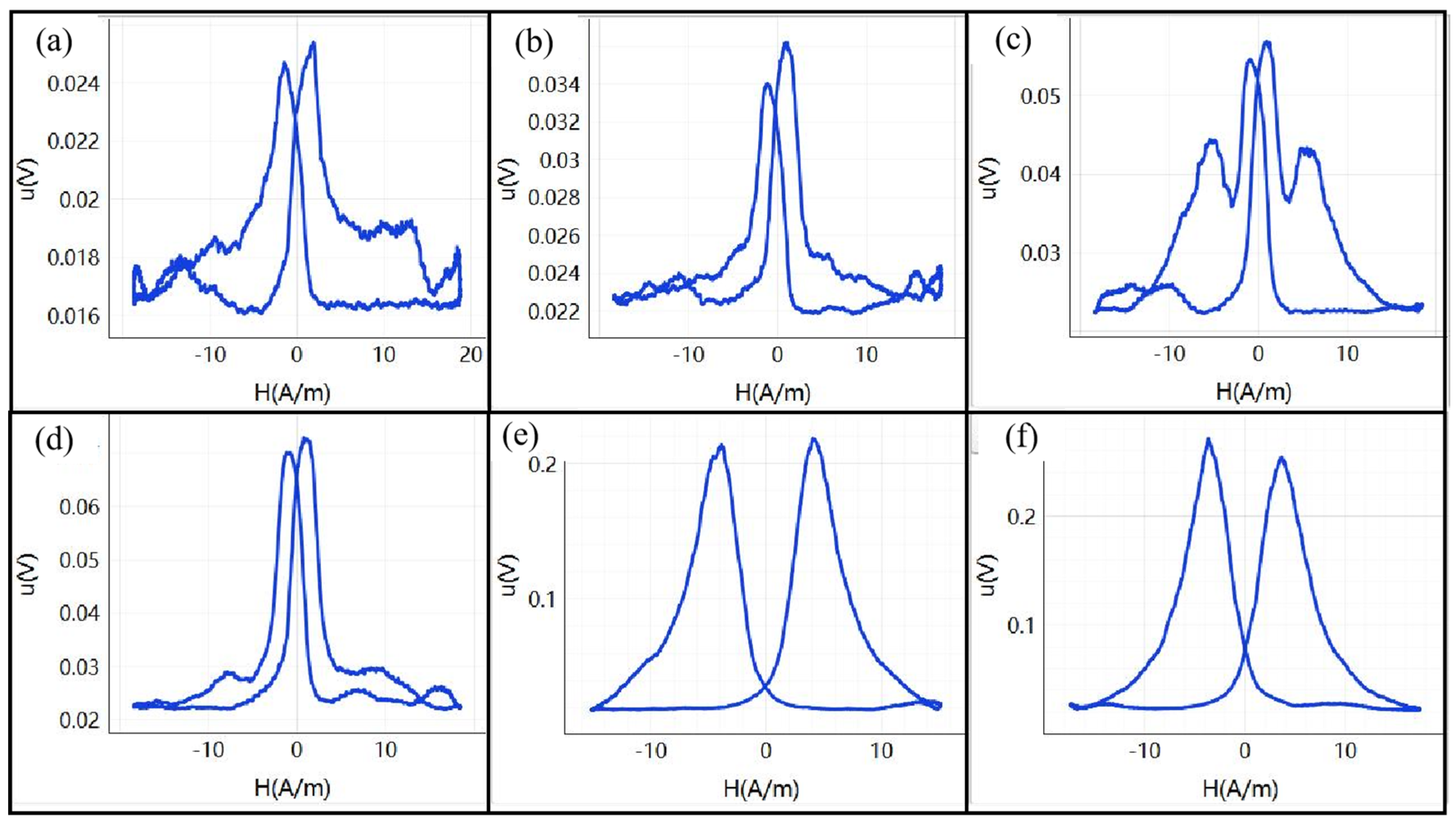

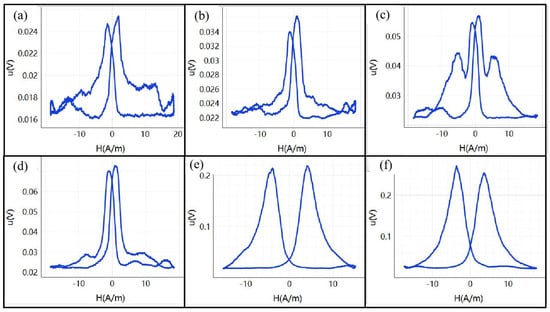

To compare the correlation between the magnetic response under in situ loading and unloading conditions, magnetic resonance signals (MBN) were measured on specimens subjected to tensile loading. The results are shown in Figure 11. As tensile stress increased, the amplitude of the specimen’s MBN signal grew gradually, and the corresponding tangential magnetic field strength-voltage hysteresis loop became more regular. Compared to the unloading state, the MBN signal under in situ loading conditions was stronger overall and exhibited noticeable changes even during the elastic stage. For example, at a stress of 300 MPa, the MBN signal amplitude was 0.060 V (Figure 11c), which is approximately 100% higher than the original specimen’s amplitude of 0.030 V (Figure 11a).

Figure 11.

MBN Tangential Magnetic Field Strength-Voltage Signal of 321 Stainless Steel Under Different Tensile Stresses: (a) 0 MPa; (b) 180 MPa; (c) 3000 MPa; (d) 4300 MPa; (e) 500 MPa; (f) 610 MPa.

As the tensile load increases, the magnetic Barkhausen noise (MBN) voltage signal of 321 austenitic stainless steel shows an upward trend overall. This is primarily due to the introduction of high dislocation density, stacking faults, and other crystalline defects by plastic deformation, which induce a phase transformation from austenite to martensite. These defects and the new phase act as strong pinning points that significantly impede irreversible magnetic domain wall jumping. While the amplitude of individual domain wall jump events may decrease due to pinning resistance, the increased number of pinning points results in greater localized magnetic energy accumulation. Once pinning is released, stronger magnetoelastic properties are often unleashed, which manifests in the detection signal as an increase in voltage amplitude.

Meanwhile, the butterfly-shaped curve of the tangential magnetic field strength tends toward a “fuller” form. This is due to an increase in residual stress and micro-defect density within the material, which requires more energy to complete the magnetization process. In order to drive domain rotation and overcome stronger pinning effects, a stronger external magnetic field must be applied. This shifts both the magnetization and demagnetization curves toward higher fields and broadens them, ultimately resulting in an increased spread of the butterfly curve and a more pronounced morphology.

The experimental results indicate that the magnetic Barkhausen noise (MBN) voltage signal is significantly more sensitive to the stress state of 321 stainless steel than coercivity or ferromagnetic phase content. Specifically, at a stress level of 300 MPa (below the yield strength), the peak MBN voltage signal increased from 0.030 V in the baseline state to 0.060 V, a 100% increase, as shown in Figure 11c. These results confirm the outstanding potential of MBN technology for early-stage damage detection in materials.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism Analysis

Analyzing Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 together shows that, as damage evolves in 321 stainless steel, the ferromagnetic phase (α′-martensite), coercive force, and magnetic Barkhausen noise (MBN) voltage signal all increase monotonically with stress (damage). This pattern holds true regardless of whether measurements are taken in situ during loading or post-unloading. Therefore, for in-service 321 austenitic stainless steel components, the damage level at different loading stages can be assessed by monitoring the percentage increase in ferromagnetic phase content, coercive force, and MBN signal relative to the initial state. This method remains effective even when the component is unloaded, offering a feasible approach for non-destructive monitoring and damage assessment of in-service structures.

During the plastic deformation of austenitic steel, a phase transformation occurs from paramagnetic austenite to ferromagnetic martensite. Once the stress exceeds the material’s yield strength, the transformation process is significantly activated, increasing the ferromagnetic phase content. This alters the relative proportions of the paramagnetic and ferromagnetic phases, which ultimately affects the material’s macroscopic magnetic response. Therefore, detecting the distribution and changes in surface magnetic signals (e.g., coercive force and magnetic Barkhausen noise) effectively assesses the component’s damage state.

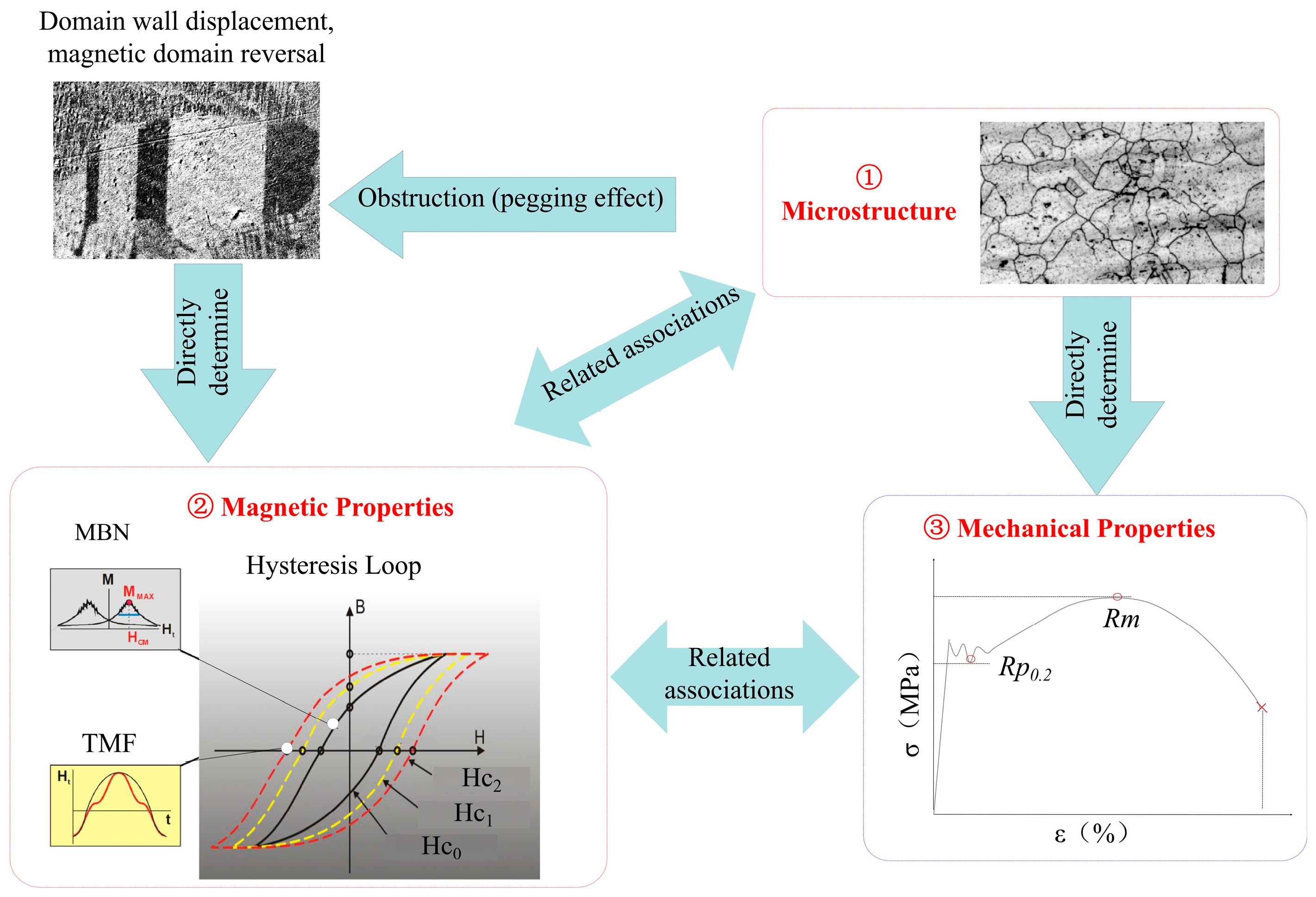

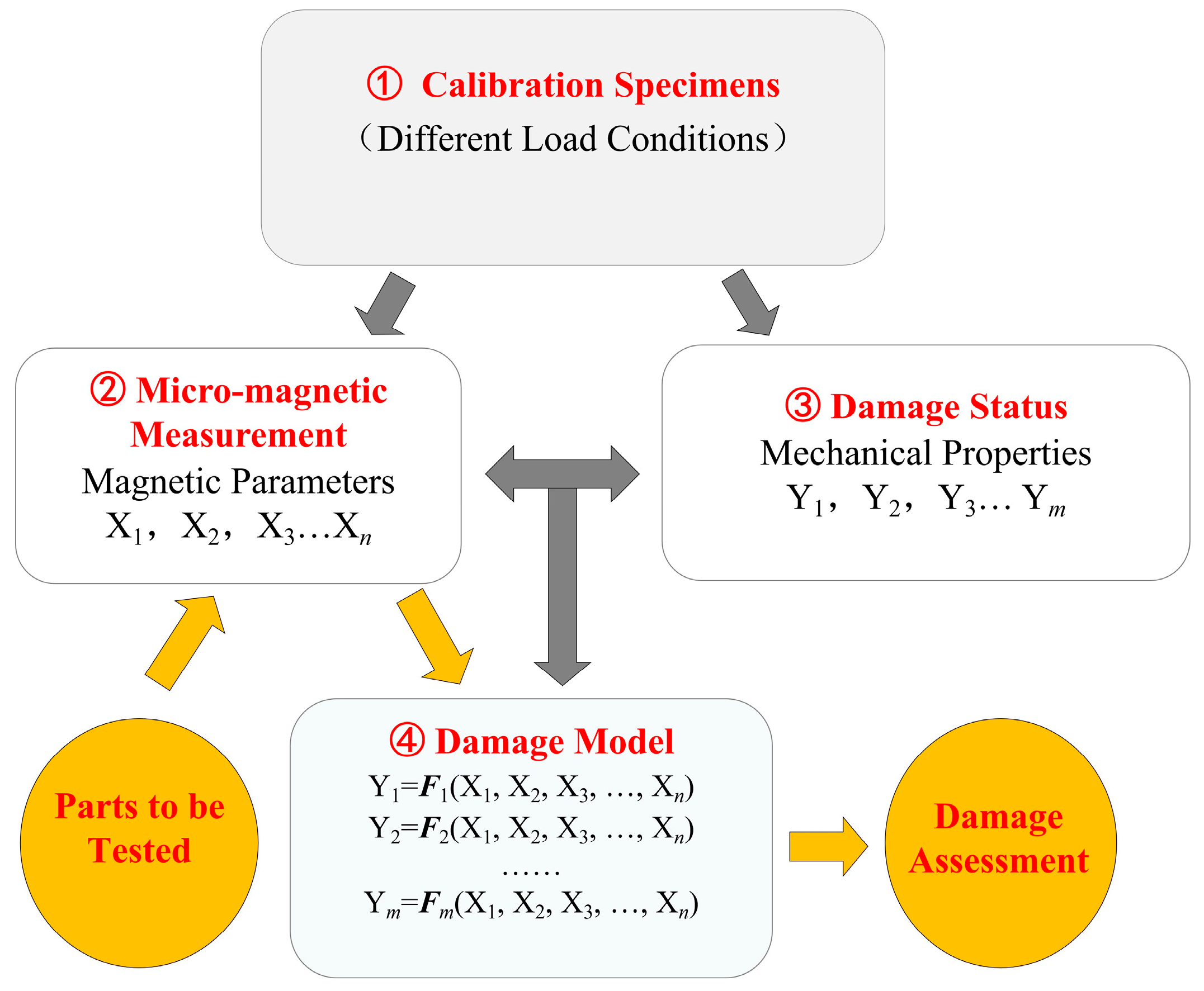

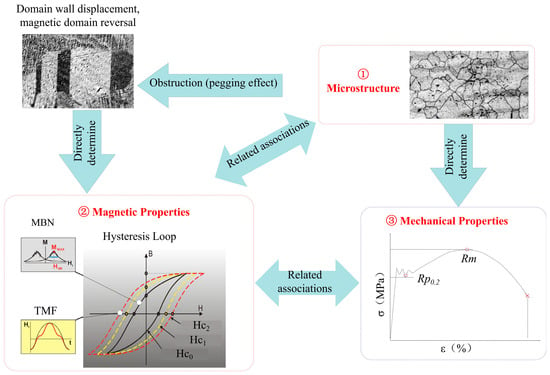

As described in Reference [1], the microstructure of materials exerts a critical influence on magnetic domain wall mobility. Specifically, during their motion, magnetic domain walls are pinned by various crystal defects such as dislocations, grain boundaries, and second phases. The strength of this pinning effect is directly determined by the density of microdefects: higher defect density imposes stronger constraints on domain wall motion, significantly affecting the material’s macroscopic magnetization behavior and corresponding mechanical response. Micro-magnetic non-destructive testing technology is precisely based on this magnetic–mechanical coupling mechanism, with the relationship between its operating principle and mechanical properties illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Diagram of the Relationship Between the Principle of Micro-Magnetic Non-Destructive Testing Technology and Mechanical Properties.

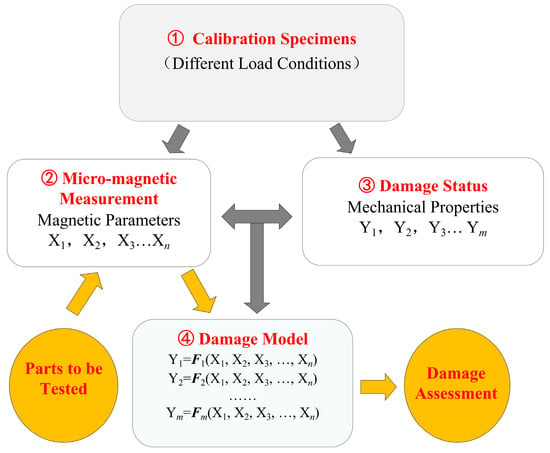

4.2. Damage Assessment

Using micro-magnetic measurement techniques (such as magnetic Barkhausen noise and coercive force), a correlation model can be established that links the macroscopic mechanical properties of 321 stainless steel with its magnetic parameters based on the aforementioned magneto-mechanical coupling mechanism. The specific steps are as follows: First, acquire multiple magnetic signals from the test specimen using micro-magnetic sensors. Second, apply varying degrees of damage to the material through conventional mechanical tests, such as tensile and fatigue testing, and measure the corresponding magnetic characteristic values. Finally, analyze the data to establish quantitative relationships between magnetic parameters and mechanical performance indicators, expressed as calibration equations, thus constructing a mechanical property evaluation model based on magnetic signals. In practical applications, substituting magnetic parameters measured on actual components into this model enables indirect assessment of material damage states. Figure 13 illustrates the corresponding damage assessment workflow.

Figure 13.

Damage Assessment Model for 321 Stainless Steel.

5. Conclusions

At room temperature, a systematic investigation of the evolution of magnetic responses corresponding to damage states under varying stress levels was conducted through tensile testing of 321 stainless steel. This investigation encompassed in situ measurements during loading and post-unloading measurements. The primary conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Void is the primary form of damage in 321 stainless steel under increasing stress. The accumulation and coalescence of these voids leads to the formation of microcracks. These microcracks then propagate and connect to form larger cracks, ultimately causing the specimen to fracture.

- (2)

- As stress increases (between 0 MPa and 610 MPa), particularly after exceeding the yield strength and entering the plastic deformation stage, the distribution of grain orientations within 321 stainless steel grains becomes significantly dispersed. Local lattice rotations occur, creating differences in orientation that markedly degrade the quality of IPF images. Concurrently, the Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) value continues to rise. Higher KAM values correspond to stronger local plastic strain, reflecting increased intra-grain dislocation density and intensified lattice distortion. Ph + GB analysis results indicate that deformation-induced martensite content increased from 3.6% in the original specimen to 12.5% during the necking stage. This confirms that plastic deformation significantly promotes the phase transformation process.

- (3)

- At a stress of 300 MPa (below the 430 MPa yield strength), the ferromagnetic phase content increased from 1.8% to 2.5%, a 38.9% increase. The coercivity increased from 3.3 A/cm to 4.0 A/cm (a 21.2% increase). Under in situ loading conditions, the peak voltage signal of the magnetic Barkhausen noise (MBN) increased significantly, from 0.030 V to 0.060 V—a 100% increase.

- (4)

- In condition monitoring of 321 stainless steel components, micro-magnetic parameters such as magnetic Barkhausen noise (MBN), coercive force (Hc), and ferromagnetic phase content can identify regions with stress concentration and damage. Changes in the magnetic field gradient reflect the extent of the martensitic transformation in austenitic stainless steel. Near the fracture stage, significant changes in magnetic field characteristic peaks indirectly indicate impending fracture, making them suitable for monitoring the condition of engineering structures. During operation, noticeable alterations in magnetic parameters typically indicate the onset of damage in 321 stainless steel. These alterations allow for an assessment of the component’s stress state and damage severity, which enables an inference of its overall health condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and W.L.; methodology, Y.L.; validation, W.L.; formal analysis, S.H. and F.G.; investigation, W.L. and Y.L.; resources, S.H.; data curation, W.L. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H. and W.L.; writing—review and editing, W.L. and F.G.; visualization, W.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, W.L.; funding acquisition, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Program (2025A1515010837).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shengzhong Hu was employed by the company Zhongke (Guangdong) Refining and Chemical Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Su, G.; Li, H.-Y.; Wang, C. Plastic damage evolution in structural steel and its non-destructive evaluation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Wang, M.; Bai, Y.; Wang, F.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y. Experimental and modeling study of high-strength structural steel under cyclic loading. Eng. Struct. 2012, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hou, S.; Tang, S.; Chen, S.; Lu, G.; Zhuang, X.; Cao, P.; Dong, Y.; Peng, X.; Yi, K.; et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of explosively welded joints between 06Cr18Ni11Ti stainless steel tube and Ti-4Al-2V alloy rod. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, A.; Shanmugam, N.; Sanjeeviprakash, K.; Palguna, Y.; Korla, R.; Lee, W.; Jeong, Y.; Yoon, J. Room and high-temperature tensile properties of austenitic stainless steel 321 fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 3996–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anilkumar, V.; Wanjura, S.; Kulawinski, D.; Palmert, F.; Ahlström, J.; Nyborg, L.; Cao, Y. Hydrogen embrittlement at elevated temperature during low cycle fatigue of AISI 321 stainless steel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2026, 184, 110307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, T.; Mock, W.; Mota, A.; Fraternali, F.; Ortiz, M. Computational assessment of ballistic impact on a high strength structural steel/polyurea composite plate. Comput. Mech. 2009, 43, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Yan, X.; Mei, Y. Ductile/brittle transition condition in Charpy V-notch impact test in structural steel. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1993, 46, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopkalo, O.; Bezlyudko, G.; Nekhotiashchiy, V.; Kurash, Y. Damage evaluation for AISI 304 steel under cyclic loading based on coercive force measurements. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 139, 105752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Cho, Y.; Jang, H. Numerical modeling of stress-state dependent damage evolution and ductile fracture of austenitic stainless steel. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2025, 318, 113439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, W. Evaluation of thermal damage and mechanical properties of P91 steel in service using nonlinear ultrasonic waves. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2025, 216, 105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, D.; Chen, J.; Yin, L. Research on non-destructive testing of stress in ferromagnetic components based on metal magnetic memory and the Barkhausen effect. NDT E Int. 2023, 138, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Gu, Z.; Cao, G.; Liu, J. A modified fatigue model for life prediction of austenitic stainless steel corrugated plate structures under cryogenic conditions considering martensitic transformation effects. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 201, 109190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Zhao, P.; Xuan, F. Cyclic behavior and damage mechanism of 304 austenitic stainless steel under different control modes. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, L.; Fan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, K. A study on fatigue life evaluation of 42CrMo steel under cyclic loading based on metal magnetic memory method. NDT E Int. 2025, 151, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, G.-R.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Niu, Y.-P.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Wang, Q. Diagnosis of early creep degradation in 12Cr1MoVG steel based on a hybrid magnetic NDE approach. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 161, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Jovicevic-Klug, M.; Tian, G.; Wu, G.; McCord, J. Correlation of magnetic field and stress-induced magnetic domain reorientation with Barkhausen Noise. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 523, 167588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Mohapatra, J.; Swaminathan, J.; Ghosh, M.; Panda, A. Magnetic evaluation of creep in modified 9Cr-1Mo steel. Scr. Mater. 2007, 57, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, B.; Zhang, H.; Xu, K.; Gao, G.; Liu, J. Research on the evolution law of magnetic memory field for defects in Q245R/321 steel under tensile load. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2025, 635, 173596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonchar, A.; Mishakin, V.; Klyushnikov, V. The effect of phase transformations induced by cyclic loading on the elastic properties and plastic hysteresis of austenitic stainless steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2018, 106, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiamiyu, A.; Eduok, U.; Szpunar, J.; Odeshi, A.G. Corrosion behavior of metastable AISI 321 austenitic stainless steel: Investigating the effect of grain size and prior plastic deformation on its degradation pattern in saline media. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, Y.; Yu, R. Numerical Simulation on magnetic-mechanical behaviors of 304 austenite stainless steel. Measurement 2019, 151, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, L.; Chmielewski, M.; Kowalewski, Z. The dominant influence of plastic deformation induced residual stress on the Barkhausen effect signal in martensitic steels. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2017, 36, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskosz, M.; Fryczowski, K.; Tuz, L.; Wu, J.; Schabowicz, K.; Logoń, D. Analysis of the possibility of plastic deformation characterisation in X2CrNi18-9 steel using measurements of electromagnetic parameters. Materials 2021, 14, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C. Nondestructive evaluation of strain-induced phase transformation and damage accumulation in austenitic stainless steel subjected to cyclic loading. Metals 2018, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Hu, B.; Cheng, H.; Luo, W.; Wang, S. Quantitative study on the effect of stress magnetization of martensite in 304 austenitic stainless steel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 138, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMakarov, A.; Gorkunov, E.; Savrai, R.; Kogan, L.K.; Yurovskikh, A.S.; Kolobylin, Y.M.; Malygina, I.Y.; Davydova, N.A. The influence of a combined strain-heat treatment on the features of electromagnetic testing of fatigue degradation of quenched constructional steel. Russ. J. Nondestruct. 2013, 49, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gorkunov, E.; Savrai, R.; Makarov, A.; Zadvorkin, S.M.; Malygina, I.Y. Magnetic inspection of fatigue degradation of a high-carbon pearlitic steel. Russ. J. Nondestruct. 2011, 47, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8/E8M-22; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Yoda, R.; Yokomaku, T.; Tsuji, N. Plastic deformation and creep damage evaluations of type 316 austenitic stainless steels by EBSD. Mater. Charact. 2010, 61, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.