Abstract

Digital and green energy transitions are driving an unprecedented demand for Strategic and Critical Raw Materials (S-CRMs), necessitating the identification of alternative sources such as secondary raw materials from exploration and mining residues. This study investigates an integrated, multi-scale approach to map and recover S-CRMs from an abandoned exploration stockpile in Zlatá Baňa, Slovak Republic. A key aspect of the methodology is comprehensive chemical and mineralogical characterization (XRF, PXRD, FTIR, LIBS, and SEM-EDS), which provided scientific validation for the diagnostic absorption features observed in laboratory reflectance spectra. These laboratory-acquired signatures were then used as endmembers to classify Sentinel-2 imagery via the Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) algorithm. This integration enabled the identification of three distinct residue classes, with classA (jarosite-rich residues) emerging as the most reactive facies. Subsequent bioleaching experiments using Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans demonstrated that microbial activity more than doubled Zn mobilization compared to abiotic controls. This cross-disciplinary strategy confirms that the synergy between advanced analytical characterization and remote sensing provides a robust, cost-effective pathway for the sustainable recovery of S-CRMs in regions affected by historical and mining activities.

1. Introduction

Raw materials (RMs) are the cornerstones of modern society and the global economy. The European Union (EU) has established an ambitious mandate to become the first carbon-neutral continent by 2050 [1], a goal that critically necessitates secure and sustainable access to Strategic and Critical Raw Materials (S-CRMs). Recent global disruptions—including the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions in Ukraine and the Middle East—have underscored the urgent need for Europe to diversify its supply chains, enhance domestic sourcing, and develop resilient value chains [2]. To maintain economic competitiveness and mitigate external risks, the EU must foster a responsible RMs sector, establish sustainable material cycles, and expand capacities within a circular economy [2]. Consequently, strengthening domestic supply chains through the recovery of S-CRMs from extractive and processing residues has become a priority [1,2,3,4].

Abandoned exploration and mine sites often host significant mineralized residues in tailings, stockpiles, and waste rocks. While historically overlooked or deemed sub-economic, these residues frequently contain valuable resources that were not targeted during initial extraction activities. Developing national exploration programs is therefore essential to unlock the potential of these so-called ‘anthropogenic ores’ [4]. This approach aligns with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the European Green Deal, promoting the transformation of historical residues and mining waste from an environmental liability into a potential economic resource [1,5].

The Zlatá Baňa (‘Gold Mine’) region has a long mining tradition dating back to 1431 [6]. Despite extensive investments in gold extraction between 1600 and 1860, operations remained largely unprofitable [7]. Subsequent exploitation focused on complex mineralization, including copper–molybdenum, gold–polymetallic, antimony, and mercury [6]. Although exploration ceased in 1991 under Slovakia’s mining attenuation program, previous surveying and drilling works generated substantial heterogeneous stockpiles of ore and tailings. Today, these deposits are subject to natural chemical and biological weathering, leading to the leaching of toxic elements into the environment [8,9].

Although these residues represent a significant environmental concern, technological advances and evolving market demands increasingly support their re-evaluation as potential secondary sources of RMs. To this end, Earth Observation (EO) data acquired from satellite platforms (e.g., Sentinel-2, PRISMA) are being progressively adopted to investigate abandoned stockpile areas and to support mineral mapping [9]. Remote sensing provides a rapid, cost-effective, and non-invasive tool to optimize in situ sampling strategies and to guide resource assessment. Within this framework, the present study develops a cross-disciplinary approach that integrates Sentinel-2 imagery with multi-analytical mineralogical characterization and innovative bio-hydrometallurgical processes (bioleaching and bioprecipitation) to assess the recovery potential of S-CRMs. Bioleaching, driven by iron- and sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms, is particularly promising for the solubilization of metals from low-grade and weathered exploration residues.

In this study, the Zlatá Baňa residues are investigated as secondary raw materials and anthropogenic ores [10]. Although characterized by relatively low-grade metal concentrations, the large volumes of accumulated stockpile materials represent a potentially significant secondary resource [10]. Furthermore, this work proposes an integrated decision support workflow consistent with the objectives of the European Critical Raw Materials Act (2024) [2], addressing the urgent need for domestic sourcing strategies and innovative recycling solutions to strengthen European autonomy [1,2,3,4].

Specifically, the study follows a four-stage sequential workflow: (i) field sampling of selected exploration stockpile; (ii) multi-analytical chemical and mineralogical characterization to establish a robust baseline; (iii) acquisition of laboratory hyperspectral signatures as endmembers and the classification of stockpile materials using Sentinel-2 imagery to map jarosite-rich residues (classA); and (iv) application of bio-hydrometallurgical leaching to the most promising material (classA) to evaluate metal recovery efficiency for Zn, Fe, and Al.

2. Materials and Methods

The cross-disciplinary approach is articulated in complementary activities to boost the knowledge about mining residues produced in Zlatá Baňa.

2.1. Study Area and Field Sampling Strategy

The study focuses on an exploration stockpile from the abandoned Zlatá Baňa site (“Golden Mine”), located in the Eastern Carpathians in the northern part of the Slanské Vrchy Mountains (Prešov District, Prešov Region, Slovakia, Europe) (Figure 1) [11].

Figure 1.

Study area of ZlatáBaňa (“Golden Mine”), located in the Eastern Carpathians in the northern part of the Slanskévrchy Mountains (Prešov District, Prešov Region, Slovakia).

The study area belongs to the northern sector of the Neogene Eastern Slovak Volcanic Field and is associated with the central zone of the Zlatá Baňa andesite stratovolcano (12.2–10.0 Ma), which is predominantly composed of extensive effusive andesite complexes [12,13]. This central volcanic zone comprises extrusive and intrusive bodies of pyroxene andesite and diorite porphyry, locally affected by K-metasomatic alteration and minor disseminated Cu stockwork mineralization at depth. Structurally, the area is characterized by a cauldron-shaped depression with a complex horst-and-graben architecture, controlled by NE–SW and NW–SE trending fault systems [14].

The stockpile was created because of geological exploration work conducted between 1960 and 1990 and does not originate from full-scale industrial mining. This heterogeneous material, consisting of excavated and host rock samples, is subject to various natural chemical and biological transformation processes. Effluents from the stockpile contain iron (Fe), lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), aluminum (Al), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), and antimony (Sb), and mainly contaminate the water and sediments of the Delňa stream and the Sigord reservoir [7] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

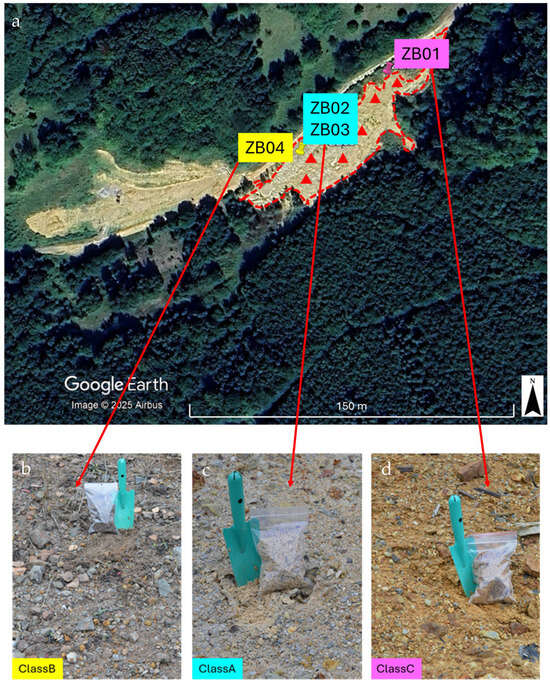

Outline of the exploration stockpile and spatial distribution of the sampling points. Boundaries were delineated via photointerpretation and historical data (a). Pushpins (ZB01–ZB04) represent the 2022 campaign points used for laboratory characterization and as spectral endmembers (b–d); red triangles represent the six targeted points collected in 2024 for the independent validation of the Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) classification. Pictures were acquired during the 2022 and 2024 campaigns.

The sampling strategy was designed to capture representative materials from the exploration stockpile maximizing the representation of its internal heterogeneity. The initial delineation of the stockpile was based on photointerpretation supported by information from local authorities and published sources [7]. During the first field campaign in November 2022, four representative samples (ZB01-ZB04) were collected across the deposit (Figure 2).

Samples for laboratory reflectance measurements were analyzed without pretreatment to preserve their natural surface textures. In contrast, for chemical and mineralogical analyses, as well as for the bioleaching experiments, the materials were air-dried and pulverized using an agate mortar to a fine grain size (approximately < 100 μm). This standardization was performed to eliminate the effects of the heap’s inherent physical heterogeneity, ensuring a high specific surface area to facilitate both microbial interaction and chemical dissolution during the assays.

Following the satellite mapping, a second field campaign was conducted in August 2024 (red triangles in Figure 2), during which six additional samples were collected. This follow-up sampling aimed to validate the satellite-derived classification.

2.2. Integrated Multi-Technique Characterization

2.2.1. Chemical Composition: X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) and Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)

Concentrations of elements in solid phases were determined by the XRF method (SPECRO XEPO 3, range of elements Na (11)-U (92), scattering targets: Mo, Co, Al2O3, Pd, HOPG-crystal, X-ray lamp (type VF50): Pd with Be window, resolution: 15 keV online Kα Mn). For the XRF analysis, 5 g of homogenized sample with 1 g of Clarinet micro powder C (CEREOX BM-0002-1) was used and then pressed under 15 t to a pellet with a 32 mm diameter. The analytical precision was monitored using certified reference materials, ensuring a relative standard deviation (RSD) below 2% for major oxides and 10% for trace elements.

LIBS measurements were performed at IESL-FORTH using a prototype micro-LIBS workstation equipped with a Q-switched nanosecond Nd:YAG laser (λ = 1064 nm, pulse energy 15 mJ, repetition rate 10 Hz). The laser beam is focused onto the sample surface through an objective lens to a spot size of approximately 40 μm. Sample positioning and mapping are achieved with XYZ motorized stages, while a CCD camera enables visualization of the surface and selection of analysis areas. Plasma emission is collected via three different optical fibers connected to two different detection systems: a dual spectrometer unit (AvaSpec-2048-2-USB2, 195–660 nm, resolution 0.2–0.3 nm) and a Czerny–Turner spectrometer (Jobin Yvon TRIAX 320) coupled with an ICCD camera (Andor DH734–18F). The latter was used to detect Li emission lines at 670.776 and 670.791 nm, which lie outside the spectral range of the Avantes spectrometers. Soil samples were milled and pressed into 8 mm pellets (0.2 g each) under 8 tons cm−2 for 5 min before analysis. A total of 256 positions per pellet were analyzed (200 μm spacing), averaging ten spectra per position. As a result, 256 LIBS spectra per pellet were acquired.

2.2.2. Mineralogical Composition: Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

PXRD analyses were performed using a Rigaku SmartLab SE diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source (40 kV, 30 mA) and a silicon strip Rigaku D/teX Ultra 250 detector. Data were collected over a 2θ range of 5–80°, with a step size of 0.01° and a scan rate of 1° min−1. Qualitative phase identification was carried out using SmartLab Studio II software (version 4.6.426.0, released February 2023) in combination with the POW_COD database.

To further support the mineralogical characterization, additional X-ray diffraction analyses were conducted using a Bruker D2 Phaser diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Diffractograms were processed with Diffrac.EVA v.2.1 software, and crystalline phases were identified using the ICDD PDF-2 database (Release 2009).

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to identify functional groups and molecular vibrations within the mine waste samples. Measurements were performed using a Bruker Alpha Platinum-ATR spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, Germany), which allows direct analysis of powdered samples without KBr pellet preparation. Spectra were collected in transmittance mode over the 400–4000 cm−1 range with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.2.3. Microscopic Analysis: Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

The microscopic elemental distribution was investigated using SEM combined with back-scattered electron (BSE) imaging, EDS, and X-ray elemental mapping. Analyses were performed on selected areas of the samples, which were coated with a ~200 Å thick conductive graphite layer to ensure proper imaging conditions. Data acquisition was carried out using a ZEISS EVO MA10 SEM quipped with an Oxford X-Max EDS detector (SEMTech Solutions, Inc., North Billerica, MA, USA). The system operated at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and employed a LaB6 electron source, enabling high-resolution imaging alongside semi-quantitative elemental analysis.

2.3. Multi-Scale Spectral Analysis: Field and Satellite Integration

Hyperspectral data were utilized for two main purposes: (i) the identification of RMs present in the mine waste, and (ii) the evaluation of their spatial distribution across the study area. Material identification was conducted through laboratory spectral measurements on collected samples, whereas spatial mapping relied on satellite-based remote sensing imagery.

Reflectance spectroscopy, a non-destructive analytical technique, was employed to measure the relative photon absorption of minerals over a defined wavelength range, compared to a calibrated reflectance standard [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Hyperspectral signatures provide detailed diagnostic information across the visible to shortwave infrared (VNIR–SWIR) spectral range, which is particularly sensitive to mineralogical features. Within this range, minerals exhibit distinctive absorption, reflection, or transmission patterns that are characteristic of their molecular structure and chemical composition.

Laboratory spectral measurements were performed on air-dried mining residue samples collected during two field campaigns. Data acquisition was carried out using a portable hyperspectral spectroradiometer (FieldSpec3, Analytical Spectral Devices—ASD, Boulder, CO, USA), covering the 350–2500 nm spectral domain. The instrument offers a spectral resolution of approximately 1.4 nm in the visible region and 2 nm in the SWIR region. Absorption features observed in this domain are primarily attributable to electronic transitions (350–1300 nm) and vibrational overtones and combinations (>900 nm) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Measurements were conducted using a 25° field-of-view bare fiber-optic probe positioned approximately 10 cm above the sample surface, targeting an area of ~15 cm2. Illumination was provided by an ASD-Lowel Pro-Lamp halogen light source placed at a 45° angle and ~35 cm from the sample. For each specimen, fifty individual spectra were acquired and averaged to produce a representative reflectance profile. A Spectralon® white reference panel (Lambertian reflector) was used as a calibration standard, measured at the beginning and end of each session, resulting in an estimated absolute reflectance error of ~2%. To mitigate anisotropic scattering and shadowing effects, samples were rotated in 90° increments, collecting ten spectra per orientation. Final spectra were averaged and pre-processed using a Savitzky–Golay smoothing filter and continuum removal to enhance the visibility of diagnostic absorption features [21,22,23].

To support spectral classification, laboratory spectra were compared with mineral spectral libraries from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) [24] and Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) [25].

For spatial mapping, a Sentinel-2 image acquired on 13 October 2022 was selected for its proximity to the field survey date. The image was obtained from the Copernicus Sentinel Missions portal (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu, accessed on 17 April 2024), atmospherically corrected, and processed using ENVI 5.6.3. [23].

To mitigate the spectral limitations of the multispectral sensor, laboratory-acquired spectra were resampled to the Sentinel-2 spectral resolution [23]. The resulting spectral classes were subsequently compared with chemical and mineralogical characterization data, to ensure a robust multi-scale integration of remotely sensed and ground-based information.

Spectral classification was performed via the Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) algorithm, which determines similarity by measuring the angle between image pixel vectors and reference spectra in multi-dimensional space [18,23,26]. A threshold of 0.03 radians was applied.

The accuracy of SAM classification was performed using samples from the 2024 campaign. Specifically, two independent ground-truth points were strategically selected for each of the identified spectral classes. Despite the compact dimensions of the site (approximately 112 m by 33 m), this targeted approach ensured that each validation point was representative of its respective class, minimizing spectral mixing.

2.4. Bio-Hydrometallurgical Process

Based on the integration of characterization data and satellite mapping, a representative mine waste sample (ZB03) was selected for the bioleaching experiments. This sample was specifically chosen as the representative endmember for classA, the spectral class identified by SAM analysis. Chemically, ZB03 exhibited the most favorable characteristics for bioprocessing, including elevated Fe2O3 and SO3 concentrations and the jarosite-rich mineral assembly.

Prior to the experiments, the sample was air-dried and pulverized to a particle size of <100 μm. Bioleaching was conducted in 250 mL shake flasks under aerobiotic conditions using an acidic 9 K nutrient medium (composition per litter: 0.4 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.1 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.04 g K2HPO4, and 33.4 g FeSO4 7H2O). The initial pH was adjusted to 2.0 with H2SO4. Each flask contained a 4% pulp density and was inoculated with a 20% bacterial culture, reaching a total liquid volume of 100 mL. Experiments were performed at 30 °C with shaking at 150 rpm. The solid mining waste was not sterilized before bioleaching.

For comparison, abiotic controls (ZB03-DW) were prepared by replacing the inoculum and nutrient medium with deionized water; in these controls, the pH was not adjusted to 2.0, allowing for the evaluation of natural leaching processes.

The amount of the liquid phase taken for chemical analysis (6 mL) was supplemented by the nutrient medium (deionized water for ZB-3-DW). Experiments were completed in duplicate for 60 days. Leachate samples for the following chemical analysis were obtained by 0.2 μm syringe filters. The concentration of metals in leachates was determined by atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) using a Varian 240FS/240 Z spectrometer (Varian, Australia) and sulfates by ion chromatography (IC) using Dionex ICS 5000 (Sunnyvale, CA, USA), equipped with an IonPac AS11-HC anion column and suppressed conductivity detector. pH values were determined by pH meter PHM210 (Radiometer Analytical SAS, Villeurbanne, France). The concentration of metals in solid phases was determined by XRF using SPECTRO iQ II (Ametek, Kleve, Germany) and by an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) using Agilent 7700ICP (PerkinElmer, CT, USA).

Microorganisms’ Chemolithotrophic, Iron- and Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria

Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (Af) was used in the bioleaching experiments. Bacterial culture was isolated from the acid mine drainage effluent from the Pech shaft, the Smolnik deposit, Slovakia [27]. A selective nutrient medium 9 K containing ferrous iron was applied for the isolation and cultivation of bacteria [28]. For the preparation of active bacterial culture, bacteria were maintained in medium 9 K at 30 °C. Upon reaching the late exponential phase of growth, the cultures were transferred into sterile shake flasks.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Chemical and Mineralogical Composition of Mining Residues

XRF analyses revealed that the bulk chemical composition of the samples is relatively homogeneous regarding major lithogenic elements (Table 1). The SiO2 and Al2O3 contents varied within narrow ranges (49.8–57 wt% and 18.4–23 wt%, respectively), indicating a consistent abundance of silicate phases across the exploration stockpile. In contrast, the Fe2O3 concentrations displayed variability: samples ZB02 (6.50 wt%) and ZB03 (6.56 wt%) contained higher iron oxide levels than ZB01 (5.60 wt%) and ZB04 (4.10 wt%). Elevated SO3 contents were also detected in ZB02 (6.20 wt%) and ZB03 (6.30 wt%), suggesting a significant presence of sulfate-bearing minerals.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the exploration stockpile samples from Zlatá Baňa (not detected: -).

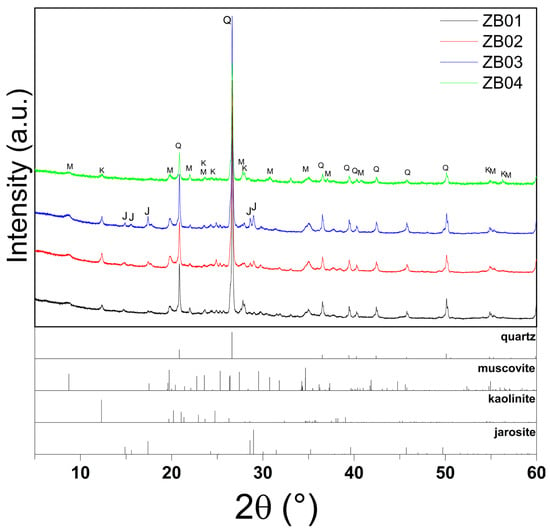

These geochemical trends were corroborated by XRPD data (Table 2, Figure 3). In ZB01, diffraction patterns confirmed the presence of Fe3+-bearing oxyhydroxides (goethite) and AlOH phyllosilicates (muscovite). Samples ZB02 and ZB03 exhibited mineral assemblages dominated by jarosite, muscovite, and kaolinite, consistent with their higher SO3 and Fe oxide contents. Sample ZB04 showed a mineralogical profile with quartz, muscovite, and kaolinite. This composition correlates with its lower Fe and sulfate concentrations compared to other samples, although the presence of iron-bearing phases and quartz is consistent with chemical and geological data.

Table 2.

Presence of the main minerals obtained by XRPD (not detected: -).

Figure 3.

XRPD patterns of samples ZB01–ZB04, highlighting quartz (Q), muscovite (M), kaolinite (K), and jarosite (J) peaks in ZB02–ZB03, the absence of jarosite in ZB01, and the exclusive presence of muscovite and kaolinite in ZB04.

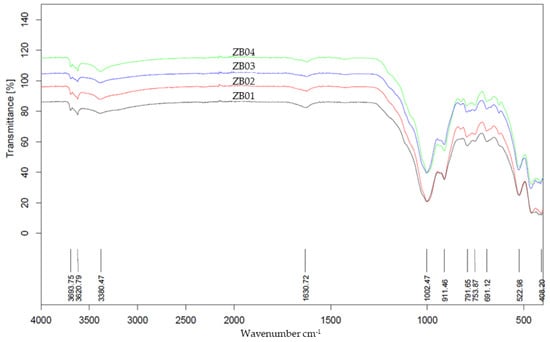

FTIR spectroscopy further identified the principal functional groups and molecular vibrations (Figure 4). The spectra exhibit diagnostic features of silicate and phyllosilicates; specifically, a broad band between 3378 and 3620 cm−1 (O–H stretching) and a peak at ~1624 cm−1 (H–O–H bending) reflect structural hydroxyl groups and adsorbed water.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of samples ZB01–ZB04, showing the characteristic absorption bands of silicate and aluminosilicate minerals (Si–O, Al–OH, and Si–O–Al vibrations), structural and adsorbed O–H groups, and metal–oxygen linkages. Variations in band intensities reflect differences in mineralogical composition among the samples.

Prominent absorptions in the 1000–1100 cm−1 region (centered near 1004 cm−1) are assigned to Si–O stretching in quartz and aluminosilicate clays. Furthermore, peaks at ~912 cm−1 (Al–OH bending) and ~791 cm−1 (Si–O–Al vibrations) confirm the presence of kaolinite. Additional bands at 694 cm−1 and 522 cm−1 correspond to Si–O–Si bending and metal–oxygen (Fe–O, Al–O) vibrations, consistent with phyllosilicates and iron oxides, while the weak band at ~422 cm−1 further indicates metal–oxygen linkages within silicate frameworks.

Overall, the spectra reveal that both the soil and mineral waste samples contain mixtures of silicate minerals (e.g., quartz) and aluminosilicates (e.g., kaolinite, muscovite), with contributions from iron oxides and hydroxides. Variations in band intensities among the samples suggest differences in the mineralogical composition and hydration state.

From an overall perspective, the combined XRF-XRPD-FTIR results do not indicate the presence of mineral phases associated with historically exploited ore deposits (e.g., Cu–Mo systems, Au–polymetallic mineralization, precious opal, Sb, Hg, or Cu–Pb–Zn ore types). Instead, the samples are dominated by silicate and secondary Fe–sulfate minerals typical of weathered exploration residues.

Regarding trace elements such as Hg, the low concentrations detected by XRF (0.01–0.03 wt%) are considered semi-quantitative due to the inherent sensitivity limits of the technique for volatile elements in pelletized samples. These values confirm the absence of major Hg-bearing mineral phases rather than providing an absolute geochemical quantification.

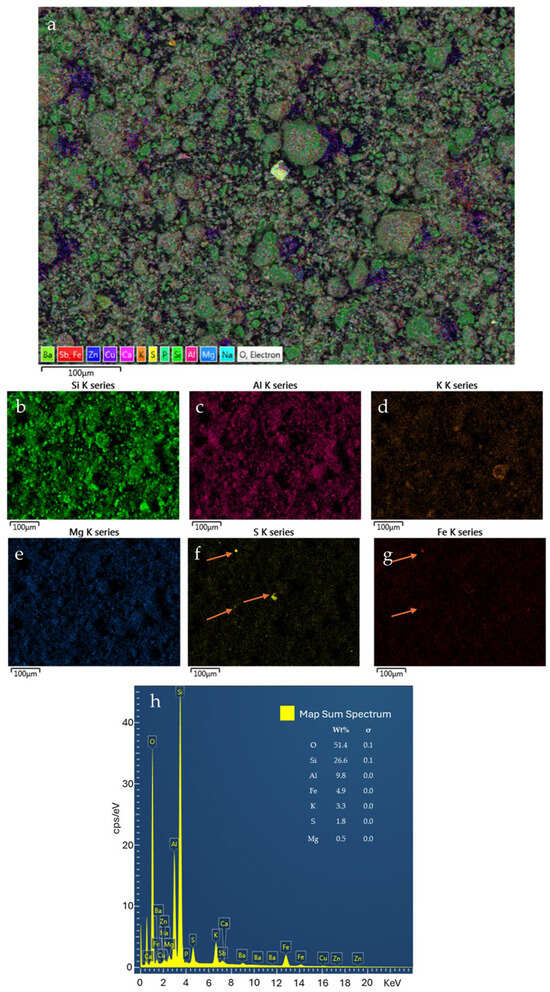

SEM–EDS analyses (Figure 5) provide essential textural evidence that complements the bulk chemical and mineralogical data. The elemental mapping confirms that the phyllosilicate matrix is dominated by muscovite, as evidenced by the consistent spatial association of Si, Al, and K (with concentrations of 26.6 wt%, 9.8 wt%, and 3.3 wt%, respectively). Furthermore, the localized presence of Fe and S hotspots (arrows in Figure 5f,g) indicates the occurrence of secondary iron–sulfate mineral aggregates (e.g., jarosite) or sulfide relics. These hotspots show concentrations of Fe (4.9 wt%) and S (1.8 wt%), with a high analytical precision reflected by slow sigma values (0.1 for Fe and S, respectively). The detection of these phases is further supported by the FeS2 factory standard used for calibration. These textural observations are crucial for ground-truthing the mineralogical interpretations, ensuring that the detected phases are physically present as distinct mineral associations rather than just chemical averages.

Figure 5.

Example of SEM-EDS results for a ZB2 sample. Combined elemental map (a); single element pattern (b–g); abundance plot (h). (The arrows indicate the localized presence of Fe and S hotspots).

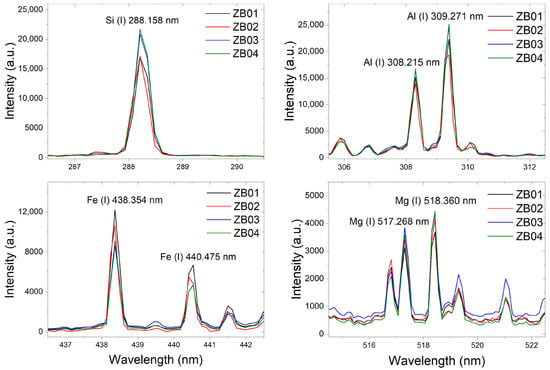

All LIBS spectra consistently displayed the characteristic emission lines of Si (288.158 nm), Al (309.284 nm), Fe (438.354 nm), and Mg (518.360 nm) (Figure 6), further confirming the elemental composition previously determined by XRF and SEM–EDS analyses. The detection of these emission lines is fully consistent with the mineralogical assemblage identified in the solid samples, reflecting the dominance of silicate and aluminosilicate phases (e.g., muscovite and kaolinite) and the presence of Fe-bearing minerals such as jarosite and goethite.

Figure 6.

Example of LIBS results, where the Si, Al, Fe, and Mg occurrence is confirmed.

In this study, LIBS is employed to validate a multi-sensor analytical framework, demonstrating that optical techniques can deliver robust geochemical proxies consistent with laboratory-grade instrumentation, thereby supporting their application in the real-time monitoring and assessment of abandoned mining districts.

Although the concentrations of several critical and strategic elements detected in the Zlatá Baňa residues (e.g., Zn, Sb, Rb, Sr, As) are lower than typical cut-off grades of primary ore deposits, their relevance should be evaluated within the conceptual framework of secondary raw materials and anthropogenic ores rather than primary mining benchmarks [10]. Recent regional-scale assessments of mining and metallurgical wastes in the West Balkan region have demonstrated that large volumes of low-grade tailings can collectively represent a significant secondary resource, even when individual metal concentrations are modest [10]. In such systems, resource potential is not solely governed by metal grade, but by a combination of factors including material availability, prior excavation and comminution, mineralogical reactivity, and the feasibility of low-energy recovery technologies [10]. Sajn et al. [10] emphasized that future metal supply in Europe will increasingly rely on the exploitation of tailings and low-grade residues, particularly in regions characterized by long mining histories, where historical processing inefficiencies resulted in the residual enrichment of valuable and critical elements. Within this context, the Zlatá Baňa residues fall within the compositional range reported for polymetallic tailings considered suitable for experimental recovery studies, supporting their classification as a potential secondary resource rather than an uneconomic waste material [10].

3.2. Reflectance Analysis and Satellite-Based Interpretation

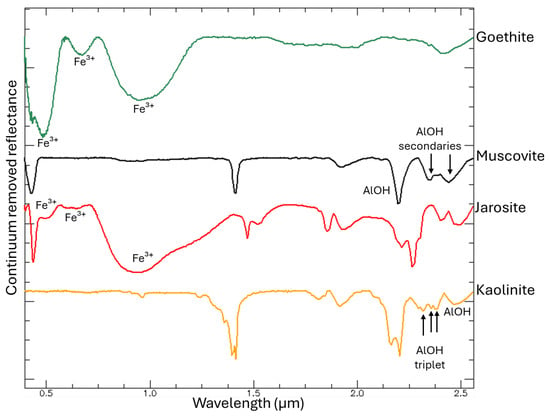

Laboratory reflectance spectra were integrated with chemical and mineralogical data to assess spectral variability across the mine waste samples. To isolate and enhance the diagnostic absorption features, hyperspectral data were processed using continuum removal and compared against USGS [24] and JPL [25] reference libraries (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Continuum removed hyperspectral signatures of the main minerals present in the mining residues, derived from the USGS spectral libraries. The principal absorption features for each mineral are highlighted to emphasize their diagnostic wavelengths.

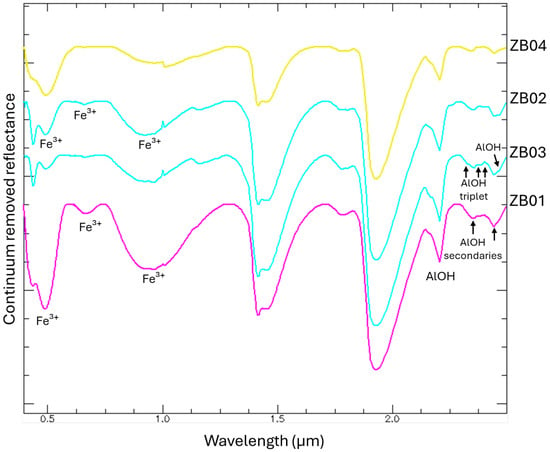

All samples exhibit well-defined shortwave infrared (SWIR) features characteristic of muscovite, including the AlOH combination band near ~2.195–2.205 μm and AlOH secondaries at 2.348 and 2.435 μm (Figure 8) [10].

Figure 8.

Hyperspectral signatures of samples ZB01, ZB02, ZB03, and ZB04 acquired with the hyperspectral spectroradiometer. Continuum removed spectra are shown to emphasize the principal absorption features associated with the main minerals present in the residues.

Notably, samples ZB02 and ZB03 displayed pronounced jarosite-related absorption in the visible–near-infrared (VNIR) domain associated with Fe3+ (at 0.437 μm, 650–660 μm, and 900–925 μm) [29]. These samples also showed distinct kaolinite diagnostic absorptions in the SWIR region, particularly those corresponding to the AlOH (AlOH triplet at 2.312 μm, 2.350 μm, 2.380 μm; AlOH at 2.440 μm) [10]. In contrast, sample ZB01 was characterized by broad Fe3+ crystal field transitions in the ~0.43–0.95 μm range, diagnostic of goethite [10]. Sample ZB04 lacked iron-bearing mineral signatures in the VNIR showing only Al-rich phyllosilicate features (muscovite and kaolinite) [16].

Despite high SiO2 concentrations (~49.8% to ~57%), quartz was negligible due to the absence of diagnostic absorption features in the VNIR–SWIR range [16]. Consequently, quartz spectra are not further discussed in this section.

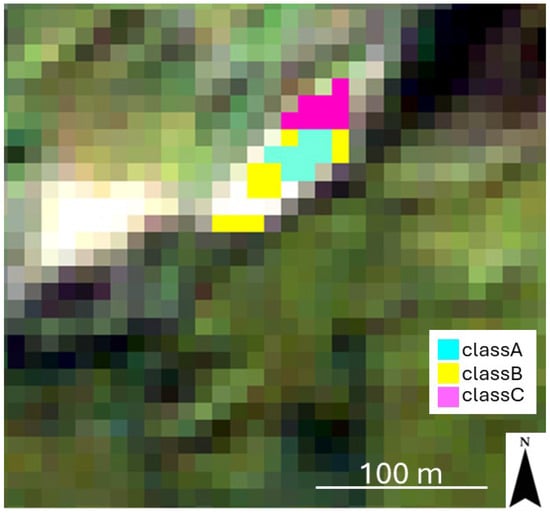

Of the thirteen spectral bands available on Sentinel-2, ten were selected for this study: eight bands within the VNIR region (ranging from 0.443 to 0.865 µm), which are highly effective for identifying Fe-rich minerals [29,30], and two bands within the SWIR region, specifically B11 (1.610 µm) and B12 (2.190 µm). Despite the presence of a characteristic muscovite absorption peak near 2.195 μm (falling within band B12), the limited number of SWIR bands makes it difficult to distinguish between different Al–OH-bearing minerals. To address this, the integration of hyperspectral signatures and characterization analyses was employed to optimize the discrimination of Sentinel-2 spectral signatures. Three distinct classes of exploration residues were identified, each characterized by a unique spectral response associated with specific mineralogical assemblages: classA (ZB02, ZB03; jarosite-, muscovite-, and kaolinite-rich), classB (ZB04; phyllosilicate-dominated), and classC (ZB01; goethite- and muscovite-dominated) (Figure 2).

These classes served as endmembers for the SAM classification of Sentinel-2 imagery. By quantifying the angular distance between pixel vectors and reference spectra, the SAM algorithm (threshold 0.03 radians) provided a spatial distribution of the different residues in the study area (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Mining residues map shows the spatial distribution of the classes. The classes have been overlaid on the Sentinel-2 image in true colors (Red: Band04; Green: Band03; Blue: Band02; spatial resolution: 10 m).

The confusion matrix yielded an overall accuracy of 91.91% and a kappa coefficient of 0.834. While classA showed perfect discrimination (producer accuracy and user accuracy of 100%), a slight spectral overlap was observed between the other categories (Table 3). Specifically, the user accuracy for classB (87.47%) and the producer accuracy for classC (81.44%) indicate a minor degree of misclassification between these two units. This is consistent with the transitional mineralogical composition of mine tailings, where secondary sulfates and phyllosilicates often coexist. Despite the overall high classification performance, some degree of uncertainty is inherent in the use of multispectral Sentinel-2 data for mineral discrimination, particularly in the SWIR domain. The limited number and bandwidth of Sentinel-2 SWIR bands (B11 and B12) restrict the ability to fully resolve overlapping absorption features of Al–OH-bearing phyllosilicates and sulfate minerals, which are more clearly distinguishable in laboratory hyperspectral measurements. This limitation is reflected in the partial misclassification observed between classes B and C, as indicated by reduced producer and user accuracy values. Such spectral overlaps are expected in heterogeneous mine waste environments, where transitional mineralogical assemblages commonly coexist at sub-pixel scales. Nevertheless, the high overall accuracy (91.91%) and kappa coefficient (0.834) demonstrate that the integration of site-specific laboratory endmembers substantially mitigates the spectral resolution constraints of Sentinel-2, enabling the reliable discrimination of the most reactive jarosite-rich residues (classA).

Table 3.

Accuracy metrics of the SAM classification based on the 2024 independent validation campaign.

The high overall user accuracy (95.82%) suggests that the integration of site-specific laboratory-derived endmembers may help to mitigate the spectral resolution limitations of Sentinel-2, thereby providing a robust approach for the exploration of residue mapping.

The successful identification of jarosite-rich residues (classA) using Sentinel-2 and the SAM algorithm aligns with recent findings [30], which demonstrated that multispectral data can effectively discriminate secondary mineral phases in abandoned mining districts. Furthermore, our results confirm that despite the lower spectral resolution compared to hyperspectral sensors, Sentinel-2 remains a robust and cost-effective tool for the screening of Fe-rich minerals [24].

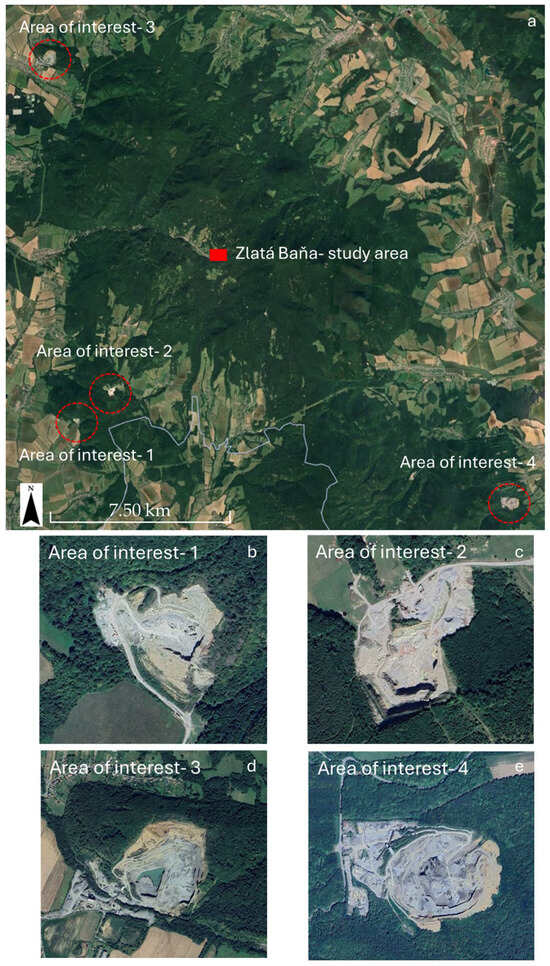

Beyond the primary study site, the classification identified additional areas of interest. Subsequent validation via Google Earth photointerpretation and field inspections confirmed these zones as other mine sites (Figure 10). This result underscores the efficacy of the proposed approach for the large-scale detection and characterization of mining residues.

Figure 10.

Examples of areas of interest identified by the Sentinel- 2 classification (a). Photointerpretation with Google Earth and field inspections confirmed that these areas of interest correspond to other mining areas (b–e) (Google Earth Pro- Image © Airbus 2025, acquired on 8 September 2025).

3.3. Bio-Hydrometallurgical Experiments

Sample ZB03 was selected as the representative material for the bio-hydrometallurgical assays because it typifies the jarosite-rich residues classified as classA. Given the strong geochemical and mineralogical similarity between ZB02 and ZB03 (Table 1 and Table 2), ZB03 can be considered a reliable proxy for this waste category. Their nearly identical Fe and SO3 contents support the assumption that ZB02 would exhibit comparable bioleaching behavior under equivalent experimental conditions. However, while ZB03 represents the most abundant and reactive residue class at the site, the exclusion of other classes characterized by lower iron and sulfide contents implies that the reported results reflect a best-case scenario for microbial metal mobilization. The extent to which lower-grade classes can sustain comparable microbial kinetics remains to be evaluated in future studies.

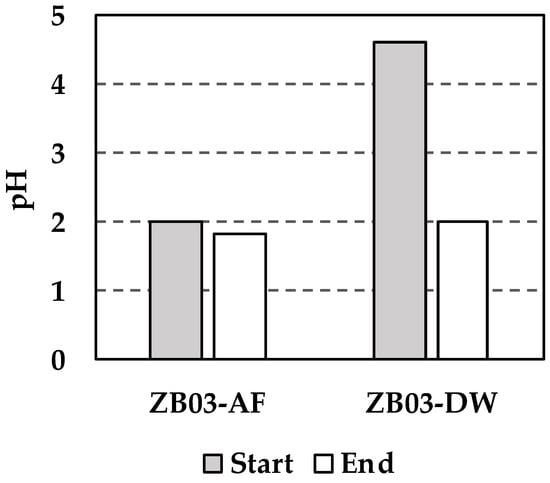

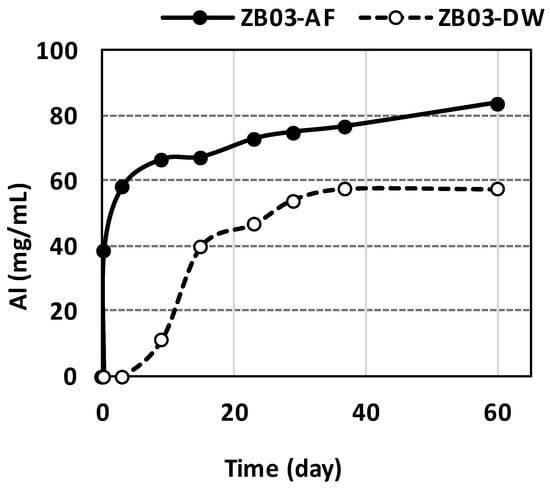

Figure 11 and Figure 12 summarize the temporal evolution of pH and sulfate concentrations during the bioleaching assays. In the inoculated system (ZB03-AF), pH decreased slightly from 2.0 to 1.84 over the 60-day period. This limited acidification suggests a potential buffering effect caused by the concomitant dissolution of silicate minerals, as evidenced by the steady release of Al which likely buffered the system due to their inherent reactivity. This buffering mechanism, driven by the consumption of protons (H+) during the breakdown of aluminosilicate frameworks, is a well-documented geochemical process in weathered mine waste environments [31]. The gradual release of Al3+ into the solution serves as a proxy for the acid-neutralizing capacity of the gangue minerals [31], explaining the observed pH stabilization. While direct microbial population data were not collected, this decline in pH, coupled with the iron and sulfate dynamics, is consistent with the active microbial oxidation of Fe2+, a hallmark of bioleaching processes driven by acidophilic consortia.

Figure 11.

Changes in the liquid phase pH during the experiments.

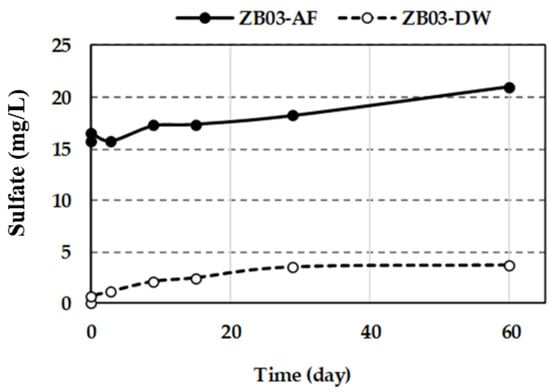

Figure 12.

Sulfate concentration in liquid phases during the experiments.

Sulfate concentrations in ZB03-AF increased progressively from 15.67 to 20.97 mg/L reflecting both initial abiotic sulfide oxidation and subsequent biologically mediated pathways. Recent studies on complex polymetallic residues confirm that the activation of thiosulfate and polysulfide oxidation pathways by iron- and sulfur-oxidizing consortia is essential for maintaining leaching kinetics [31,32]. The initial slow increase (days 1–3) is attributed to acid-driven dissolution, whereas the subsequent steady rise suggests the activation of thiosulfate and polysulfide oxidation pathways by the iron- and sulfur-oxidizing consortium. In contrast, the abiotic control (ZB03-DW) showed a decline in pH (from 4.6 to 2.0) and a more moderate sulfate increase (0.67 to 3.90 mg/L), consistent with the natural weathering of acid-generating phases.

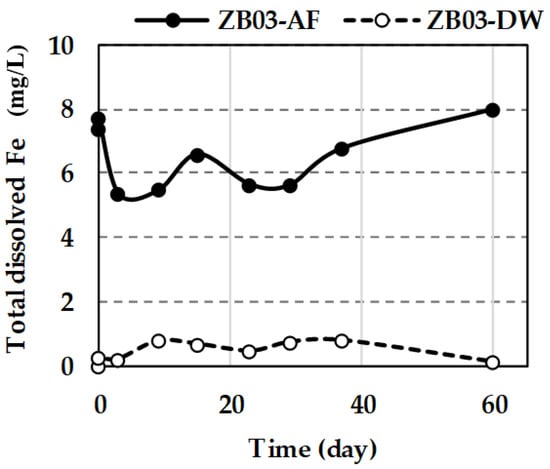

Dissolved iron dynamics further underscore the microbial influence. In ZB03-AF, Fe concentrations initially dropped from 7.7 to 5.2 mg/L (first 4 days), likely due to rapid microbial oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, which was subsequently consumed during sulfide oxidation. Fe levels then fluctuated, reaching 8.0 mg/L by day 60 (Figure 13), reflecting the continuous cycle of iron regeneration and its role as an oxidant. In the abiotic control, Fe release remained minimal (0.1–0.8 mg/L), confirming that significant Fe mobilization is biologically driven. These concentration levels (expressed in mg/L) are geochemically consistent with the initial solid-phase composition of the waste (6.60 wt% Fe2O3, as determined by XRF analysis). The observed iron dynamics reflect a controlled mobilization from the mineral matrix, where the biogenic acid promotes the progressive dissolution of iron-bearing phases without exceeding the theoretical mass balance limits of the system.

Figure 13.

Total dissolved Fe in liquid phases during the tests.

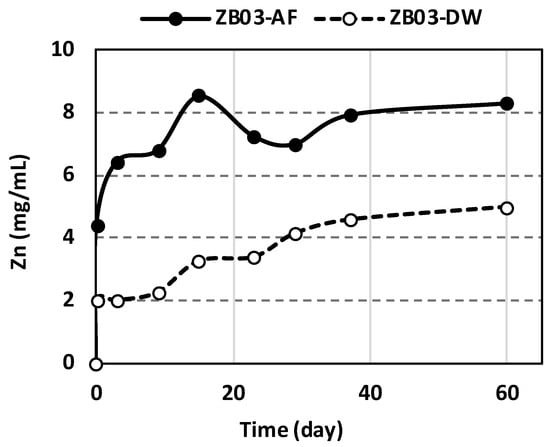

Microbial activity markedly enhanced metal solubilization, particularly for zinc. Zn mobilization in ZB03-AF was detectable from day 1, reaching a maximum of 8.3 mg/mL by day 60 (Figure 14) [33]. Crucially, Zn concentrations in the abiotic controls reached only ~50% of the biotic values, underscoring the catalytic role of the bacterial consortium. In ZB03-DW, Zn release was attributable to intrinsic acid-generating minerals.

Figure 14.

Concentration of Zn in liquid phases during the tests.

Metal recovery yields for Zn and Al were calculated based on the initial solid-phase concentrations determined by XRF and the total dissolved metal content measured in the leachate. Under biotic conditions, Zn bioleaching achieved a maximum recovery of 82.04% after 60 days, confirming the effectiveness of the microbial consortium in enhancing metal mobilization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Metal concentrations in solid phase before/after bioleaching and calculated recovery efficiencies.

In contrast, Fe showed an apparent increase in the solid phase. After bioleaching, its concentration in the solid phase increased from 42,430 g/kg to 85,440 g/kg and 65.170 g/kg in ZB03-AF and ZB03-DW, respectively. It is attributed to the microbial oxidation of Fe2+ supplied by the 9 K nutrient medium and subsequent precipitation of Fe3+ phases. The pulp density was maintained at 4% (4 g of sample ZB03 per 100 mL of solution), consistent with standard bioleaching protocols.

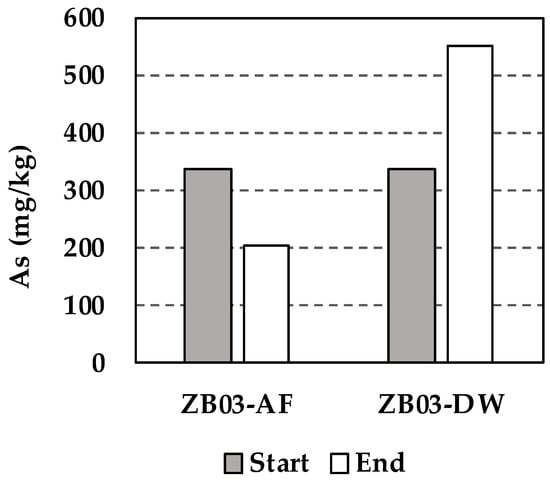

Regarding arsenic (As), XRF analysis of the solid residues showed a decrease in all biotic systems. Meanwhile, the abiotic control (ZB03-DW) exhibited a slight relative increase in As (Figure 15). In the abiotic system, the increase can be attributed to a concentration effect following the dissolution of soluble phases, combined with the lack of active biogenic precipitation. Conversely, in the biotic system (ZB03-AF), the microbial oxidation of iron leads to the formation of secondary Fe oxyhydroxides. These minerals effectively act as ‘scavengers’ through co-precipitation or adsorption, limiting the net release of As into the solution. Consequently, while the biotic pathway facilitates the breakdown of As-bearing minerals, the concurrent formation of secondary biogenic phases governs the final concentration of arsenic in the leachate, a critical factor for environmental waste management.

Figure 15.

Concentration of As in solid phase before and after tests (PXRD analysis).

Silicate dissolution, evidenced by Al release, occurred in both systems. In ZB03-AF, Al solubilization reached 83.8 mg/mL at day 60 compared to 57.5 mg/mL in the abiotic control (Figure 16). This dissolution likely contributed to the observed pH stabilization throughout the experiment.

Figure 16.

Concentration of Al in the liquid phases during the 60-day bioleaching and abiotic experiments.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluates historical exploration stockpiles from the Zlatá Baňa district within the framework of secondary raw materials and anthropogenic ores. A multi-analytical characterization (XRF, XRPD, FTIR, SEM–EDS, LIBS, and laboratory reflectance spectroscopy) indicates that the investigated residues are dominated by silicate and aluminosilicate phases, with variable proportions of Fe- and sulfate-bearing minerals controlling their geochemical reactivity. Samples ZB02 and ZB03 exhibit the highest Fe2O3 and SO3 contents and are characterized by jarosite-rich mineral assemblages, identifying them as the most reactive facies and the most suitable candidates for bio-hydrometallurgical processing.

The integration of laboratory spectroscopic data with Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery, using Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) classification, enabled the identification and spatial delineation of three distinct classes of exploration residues. This approach confirms the applicability of remote sensing as an efficient tool for the large-scale screening and preliminary assessment of heterogeneous mining stockpile deposits supporting targeted sampling strategies and the prioritization of residues with higher secondary resource potential.

Bioleaching experiments conducted on the representative jarosite-rich sample ZB03 demonstrate the technical feasibility of biologically mediated metal mobilization from low-grade, weathered residues. Despite modest bulk concentrations of critical and strategic elements, microbial activity significantly enhanced metal solubilization, particularly for zinc, with dissolved concentrations exceeding those observed under abiotic conditions by more than a factor of two. These results indicate that, in such systems, recoverability is governed primarily by mineralogical reactivity, prior comminution, and process accessibility rather than by bulk metal grade alone.

In parallel, bioleaching promoted the partial immobilization of environmentally relevant elements, notably arsenic, through secondary iron oxyhydroxide formation, thereby limiting its net release into solution. This coupled recovery–stabilization behavior highlights the potential of bio-hydrometallurgical approaches for the integrated management of low-grade historical residues. However, the same processes are intrinsically associated with acid generation and metal-rich leachates, which may pose environmental risks if not adequately controlled. Accordingly, the environmental sustainability of bioleaching-based recovery from abandoned exploration sites depends on the management of the secondary waste streams, including acidic solutions, iron-rich precipitates, and process waters requiring treatment prior to discharge or reuse.

Future investigations should address scaling up to additional residue classes, optimize operating conditions to minimize acid generation and secondary residues, and integrate life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis to evaluate sustainability. The proposed cross-disciplinary approach provides a transferable framework for the identification, mapping, and experimental evaluation of secondary raw materials in regions affected by historical exploration and mining activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.; methodology, D.G. and A.L.; validation, D.G., A.L., E.M., D.C., R.G.T., V.P., M.B., A.E., M.P., R.S., I.N., S.U. and M.L.; formal analysis, D.G., A.L., E.M., D.C., R.G.T., V.P., M.B., A.E., M.P., R.S., I.N., S.U. and M.L.; investigation, D.G., A.L., E.M., D.C., R.G.T., V.P., M.B., A.E., M.P., R.S., I.N., S.U. and M.L.; resources, D.G., A.L., E.M., D.C., R.G.T., V.P., M.B., A.E., M.P. and R.S.; data curation, D.G., A.L., E.M., D.C., R.G.T., V.P., M.B., A.E. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, D.G., A.L., E.M., D.C., R.G.T., V.P., M.B., A.E., M.P., R.S., I.N., S.U. and M.L.; visualization, D.G., A.L., E.M., D.C., R.G.T., V.P., M.B., A.E., M.P., R.S., I.N., S.U. and M.L.; project administration, D.G. and A.L.; funding acquisition, A.L. and S.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Slovak Grant Agency for Science Grant No. 2/0108/23, Grant 1/0213/22, by Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract APVV-20-0140 and Joint Project of the CNR/SAS (2020/2022). LIBS measurements were carried out in the frame of ReMade@ARI, funded by the European Union as part of the Horizon Europe call HORIZON-INFRA-2021-SERV-01 under grant agreement number 101058414 and co-funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) under the UK government’s Horizon Europe funding guarantee (grant number 10039728) and by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number 22.00187. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council or the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI). Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. The European Green Deal Brussels, 11.12.2019 COM (2019) 640 Fina. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2024/1252 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024 Establishing a Framework for Ensuring a Secure and Sustainable Supply of Critical Raw Materials (Critical Raw Materials Act). Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, 2024/1252, 1–67. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1252/oj (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Gauß, R.; Calleja, I.; Lamm, L.; Nadoll, P.; Zimmermann, D.; Klossek, A.; Schäfer, B. EIT Raw Materials Lighthouses: Responsible Sourcing, Sustainable Materials, Circular Societies; EIT RawMaterials: Budapest, Hungary, 2022; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU 2023—Final Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-92-1-101425-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bakos, F.; Chovan, M.; Žitňan, P.; Bačo, P.; Bahna, B.; Bednárová, S.; Bednár, R.; Ferenc, Š.; Finka, O.; Gargulák, M.; et al. Gold in Slovakia, 2nd ed.; LÚČ: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2017; pp. 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenker, V.A.; Jelen, S.; Genkin, A.D.; Duda, R.; Sandomirskaja, S.M.; Malov, V.S.; Kotulak, P. Metallic minerals of productive assemblages of the ZlatáBaňa deposit (Eastern Slovakia); specialities of chemical composition. Miner. Slov. 1988, 20, 481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Junáková, N.; Bálintová, M.; Junák, J.; Demčák, Š. The Impact of Anthropogenic Activity on the Quality of Bottom Sediments in the Watershed of the Delňa Creek. Eng. Proc. 2023, 57, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demková, L.; Árvay, J.; Bobuľská, L.; Hauptvogl, M.; Hrstková, M. Open mining pits and heaps of waste material as the source of undesirable substances: Biomonitoring of air and soil pollution in former mining area (Dubnik, Slovakia). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 5227–35239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šajn, R.; Ristović, I.; Čeplak, B. Mining and Metallurgical Waste as Potential Secondary Sources of Metals—A Case Study for the West Balkan Region. Minerals 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koděra, P.; Mathur, R.; Zhai, D.; Milovsky, R.; Baco, P.; Majzlan, J. Coupled antimony and sulfur isotopic composition of stibnite as a window to the origin of Sb mineralization in epithermal systems (examples from the Kremnica and Zlatá Baňa deposits, Slovakia). Min. Depos. 2025, 60, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaličiak, M.; Repčok, I. Reconstruction of temporal evolution of volcanoes in the northern part of the Slanske Vrchy Mts. Miner. Slov. 1987, 19, 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Štohl, J.; Lexa, J.; Kaličiak, M.; Bacso, Z. Metallogeny of stockwork base metal mineralizations in Neogene volcanics of Western Carpathians. Miner. Slov. 1994, 26, 75–117, (In Slovak with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, F.; Nagymarosy, A.; Jeleň, S.; Bačo, P. Minerals and wines: Tokaj Mts., Hungary and Slanské vrchy Mts., Slovakia. Acta Miner.-Petrogr. Field Guide Ser. 2010, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Peyghambari, S.; Zhang, Y. Hyperspectral remote sensing in lithological mapping, mineral exploration, and environmental geology: An updated review. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2021, 15, 031501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Fernandes, J.; Silva, J.; Perrotta, M.M.; Lima, A.; Teodoro, A.C.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Dias, F.; Barrès, O.; Cauzid, J.; Roda-Robles, E. Interpretation of the Reflectance Spectra of Lithium (Li) Minerals and Pegmatites: A Case Study for Mineralogical and Lithological Identification in the Fregeneda Almendra Area. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.N.; King, T.V.V.; Klejwa, M.; Swayze, G.A.; Vergo, N. High spectral resolution reflectance spectroscopy of minerals. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 12653–12680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, V.C. The Infrared Spectra of Minerals; Mineralogical Society: London, UK, 1974; pp. 1–539. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, G.R. Spectral signatures of particulate minerals in the visible and near infrared. Geophysics 1977, 42, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.N. Spectroscopy of Rocks and Minerals, and Principles of Spectroscopy. In Remote Sensing for the Earth Sciences: Manual of Remote Sensing, 3rd ed.; Rencz, A.M., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Chapter 1; Volume 3, pp. 1–728. [Google Scholar]

- Swayze, G.A.; Clark, R.N.; Goetz, A.F.; Livo, K.E.; Breit, G.N.; Kruse, F.A.; Sutley, S.J.; Snee, L.W.; Lowers, H.A.; Post, J.L.; et al. Mapping Advanced Argillic Alteration at Cuprite, Nevada, Using Imaging Spectroscopy. Econ. Geol. 2014, 109, 1179–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lööw, J.; Johansson, J. Eight Conditions That Will Change Mining Work in Mining 4.0. Mining 2024, 4, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglietta, D.; Conte, A.M.; Paciucci, M.; Passeri, D.; Trapasso, F.; Salvatori, R. Mining Residues Characterization and Sentinel-2A Mapping for the Valorization and Efficient Resource Use by Multidisciplinary Strategy. Minerals 2022, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokaly, R.F.; Clark, R.N.; Swayze, G.A.; Livo, K.E.; Hoefen, T.M.; Pearson, N.C.; Wise, R.A.; Benzel, W.M.; Lowers, H.A.; Driscoll, R.L.; et al. USGS Spectral Library Version 7. U.S. Geol. Surv. Data Ser. 2017, 1035, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, C.I.; Hook, S.J.; Paylor, E.D. Laboratory reflectance spectra for 160 minerals 0.4–2.5 micrometers. Bull. US Geol. Surv. 1992, 92, 1–401. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2014/40148 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Kruse, F.A.; Lefkoff, A.B.; Boardman, J.B.; Heidebrecht, K.B.; Shapiro, A.T.; Barloon, P.J.; Goetz, A.F.H. The Spectral Image Processing System (SIPS)—Interactive Visualization and Analysis of Imaging spectrometer Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1993, 44, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartova, Z. Identification of Microbial Communities in Environmental Matrices by Non-Cultivation Methods. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Geotechnics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, Kosice, Slovakia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karavajko, G.I.; Rossi, G.; Agate, A.D.; Groudev, S.N.; Avakyan, Z.A. Biogeotechnology of Metals; Centre of Projects GKNT: Moscow, Russia, 1988; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J.L.; Murad, E. The visible and infrared spectral properties of jarosite and alunite. Am. Min. 2005, 90, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Rodríguez, P.; Tapia Guerra, F. Synergetic use of the Sentinel-2, ASTER, and Landsat-9 data for the identification of hydrothermal alteration and minerals in the Coastal Cordillera, between 28°57′20″ and 29°13′25″ S, northern Chile. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2026, 169, 105883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henne, A.; Craw, D.; Vasconcelos, P.; Southam, G. Bioleaching of waste material from the Salobo mine, Brazil: Recovery of refractory copper from Cu hosted in silicate minerals. Chem. Geol. 2018, 498, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, C.B.; Blannin, R.; Ebert, D.; Frenzel, M.; Pollmann, K.; Kutschke, S. Bioleaching of metal(loid)s from sulfidic mine tailings and waste rock from the Neves Corvo mine, Portugal, by an acidophilic consortium. Miner. Eng. 2022, 188, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, W.L.S.; McParland, D.; Jones, T.R.; Power, I.M.; Langendam, A.; Southam, G.; McCutcheon, J. Microbial mobilization and reprecipitation of transition metals in waste rock from an abandoned pyrite mine: Implications for metal recovery. Can. J. Mineral. Petrol. 2024, 62, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.