Abstract

This study investigates the microstructural evolution and wear behaviour of aluminium 7075-based metal matrix composites (MMCs) reinforced with high-entropy alloy (HEA) particles and fabricated via friction stir processing (FSP). A detailed characterisation of the grain refinement in the 7075 matrix was conducted, revealing significant dynamic recrystallization and grain size reduction induced by the severe plastic deformation inherent to FSP. The interaction between the matrix and HEA particles was analysed, showing strong interfacial bonding, which was further influenced by post-processing heat treatments. These microstructural modifications were correlated with the wear performance of the composites, demonstrating enhanced resistance due to the synergistic effect of precipitates and particle reinforcement. The findings highlight the potential of FSP as a viable route for tailoring surface properties in advanced MMCs for demanding tribological applications.

1. Introduction

Metal matrix composites (MMCs) have emerged as a class of advanced materials that offer superior mechanical and functional properties compared to conventional monolithic metals [1]. Among these, aluminium matrix composites (AMCs) are particularly attractive due to their high specific strength and excellent thermal conductivity [2]. Nevertheless, traditional fabrication methods such as stir casting and powder metallurgy often suffer from limitations including poor particle dispersion, undesirable interfacial reactions, and residual porosity, which can significantly compromise the performance of the final composite [3].

Friction stir processing (FSP), a solid-state technique derived from Friction Stir Welding (FSW) [4], has gained considerable attention as a promising alternative to conventional methods. By inducing intense plastic deformation and dynamic recrystallization without melting the base material, FSP enables the homogeneous incorporation of reinforcement particles into the metal matrix [5]. This results in refined microstructures and enhanced mechanical properties. FSP is particularly well-suited for the fabrication of surface MMCs, where improved wear resistance is essential for extending the service life of components in demanding applications such as aerospace, automotive, and marine environments [6].

The tribological performance of MMCs produced via FSP has been extensively investigated. For example, the incorporation of ceramic reinforcements such as silicon carbide (SiC), aluminium oxide (Al2O3), and boron carbide (B4C) into aluminium matrices has been shown to significantly reduce both the coefficient of friction and the wear rate. These improvements are primarily attributed to the formation of a hard, wear-resistant surface layer characterised by fine, equiaxed grains and a uniform distribution of reinforcements. In one study, the addition of SiC nanoparticles to an AA7075 matrix via FSP led to a 40% reduction in specific wear rate compared to the unreinforced alloy [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Furthermore, hybrid reinforcement strategies combining different types of particles such as SiC and BN have demonstrated synergistic effects, further enhancing both wear resistance and mechanical strength. The ability of FSP to selectively modify surface properties without altering the bulk material makes it an ideal technique for producing functionally graded materials, where a tough core is complemented by a hard, wear-resistant surface [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Beyond aluminium, FSP has also been successfully applied to other metal matrices such as copper. For instance, copper matrix composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) via FSP have exhibited significantly lower friction coefficients and wear rates, attributed to the formation of a lubricating film and grain refinement in the processed zone. These findings highlight the versatility of FSP in tailoring tribological properties across a wide range of metallic systems [23,24].

High-entropy alloys (HEAs), defined by their multi-principal element composition and high configurational entropy, offer a unique combination of mechanical strength, thermal stability, and corrosion resistance [25,26,27]. These characteristics make HEAs promising candidates for wear-resistant applications when used as particulate reinforcements in MMCs. Despite their potential, research on HEA-reinforced aluminium alloys, particularly precipitation-hardenable grades like AA7075, remains limited. Most existing studies focus either on conventional ceramic reinforcements or on HEAs in bulk form, leaving a gap in understanding their behaviour when incorporated as particles via FSP [28,29,30,31]. Specifically, for AA7075-based Al–HEA composites processed via FSP, the microstructural evolution, particle distribution, interfacial diffusion, and tribological performance after post-processing heat treatments are still largely unexplored. This gap motivates the current study, which evaluates the influence of two distinct HEA particle types on the processability, microstructure, and wear behaviour of AA7075 composites fabricated via FSP. Particular attention is given to how the aluminium matrix transforms during processing and interacts with the HEA particles, as these factors govern particle dispersion, interfacial strength, and the overall tribological response.

This study aims to address this gap by evaluating the influence of two distinct types of HEA particles on the processability, microstructural evolution, and wear performance of AA7075 composites fabricated via friction stir processing. Particular emphasis is placed on understanding the transformation of the aluminium matrix and the interactions between the matrix and the HEA particles during both the fabrication process and subsequent heat treatment. These factors are critical, as they govern particle distribution, interfacial bonding, and the overall tribological behaviour of the composite. By investigating these mechanisms, the study seeks to contribute to the development of advanced aluminium-based materials optimised for wear-critical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Aluminium alloy AA7075 in T6 condition was selected as base material. The chemical composition (wt.%) of the alloy is provided in Table 1. Two different high-entropy alloy powders (HEA) were used as reinforcement particles, FeCoCrNiMn (Cantor alloy) and 40Ni20Mn20Cr20Cu (HEA modified by Basque Country University); both powders were supplied by Heeger Materials Inc. (Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Their respective chemical compositions (wt.%) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of base material and high-entropy alloy powders (wt.%).

The Cantor HEA powder exhibited D10, D50, and D90 values of 15.34 µm, 26.91 µm, and 43.60 µm, respectively, with an apparent density of 4.40 g/cm3 and a Hall flow rate of 20.80 s/50 g. In comparison, the modified HEA powder showed slightly coarser particle size characteristics (D10 = 15.77 µm, D50 = 33.60 µm, D90 = 51.08 µm), along with a similar apparent density (4.44 g/cm3) and a Hall flow rate of 20.42 s/50 g.

2.2. Fabrication of Metal Matrix Composites

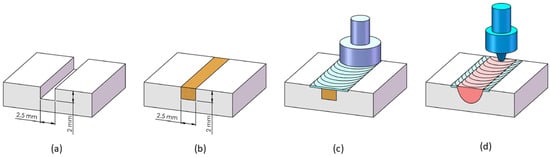

The schematic representation of the friction stir processing (FSP) route used to manufacture the metal matrix composite is presented in Figure 1. First, a continuous groove, 2 mm wide and 2.5 mm deep, was machined along the friction stir processing (FSP) path on 6 mm thick AA7075 aluminium alloy plates. The machined plates were then degreased using ethanol to remove contaminants and subsequently filled with the reinforcement particles described in Section 2.1. Then, to limit the displacement of particles outside the groove during processing, an initial sealing pass was carried out using a pinless tool with a diameter of 20 mm. Finally, four processing passes were performed using a tool with a 12 mm shoulder diameter and a cylindrical pin 2.7 mm in length. A four-pass schedule was selected to promote a more uniform distribution of the reinforcement particle. This was combined with a processing strategy in which the advancing side of each pass alternated to become the retreating side in the subsequent pass to minimise potential asymmetry in material flow. The process parameters used for both the sealing and processing passes are summarised in Table 2. The equipment used to carry out the trials was an MTS I-STIR PDS 4 friction stir processing machine (Eden Prairie, MN, USA).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the friction stir processing (FSP) route, (a) machining of grooves, (b) filling of HEA particles, (c) sealing pass, and (d) processing pass.

Table 2.

Process parameters used for both the sealing and processing passes.

Post-processing heat treatments were applied to the friction stir processed samples to evaluate the influence of thermal history on the microstructure and properties of the composites. Two post-processing thermal conditions were applied to study grain structure, precipitation, and HEA particle/matrix interfacial effects separately: (i) artificial ageing at 200 °C for 5 h, followed by water quenching to analyse the precipitation while preserving the refined microstructure, which is beneficial for wear resistance [7,21,32]; and (ii) a solution heat treatment at 480 °C for 2 h, also followed by water quenching and subsequent artificial ageing under the same conditions to re-establish precipitation and microstructure from a homogenised solution and to tune HEA/Al interfacial diffusion chemistry, consistent with established AA7075 practice [19,33] and with FSP-processed Al-HEA composites [34,35,36]. In both cases, a controlled heating rate of 16 °C/min was employed.

Table 3 summarises the samples investigated in this study and the corresponding nomenclature used throughout the manuscript.

Table 3.

Nomenclature of samples investigated in this study.

2.3. Metallographic Characterisation

The metallographic characterisation of the FSP AA7075 composites was performed on cross-sectioned samples using a stereoscopic microscope (LEICA DVM6, Wetzlar, Germany) and an optical microscope (OM, LEICA MICROSYSTEMS GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). A field emission gun scanning electron microscope (FEG-SEM ZEISS-ULTRA PLUS, Oberkochen, Germany) was employed to capture high-resolution images of the reinforcing particles. Compositional analysis and matrix–particle interaction studies (linescan and mapping analysis) were performed using an AZTEC energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector (Abingdon, UK). Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) mappings were generated at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV and collected using a CRYSTAL detector from Oxford Instruments (Abingdon, UK). The indexation of the Kikuchi lines and determination of orientations were performed using the AZTEC 2.0 version and CHANNEL 5 software, developed by HKL Technology (Oxford, UK).

2.4. Wear Testing

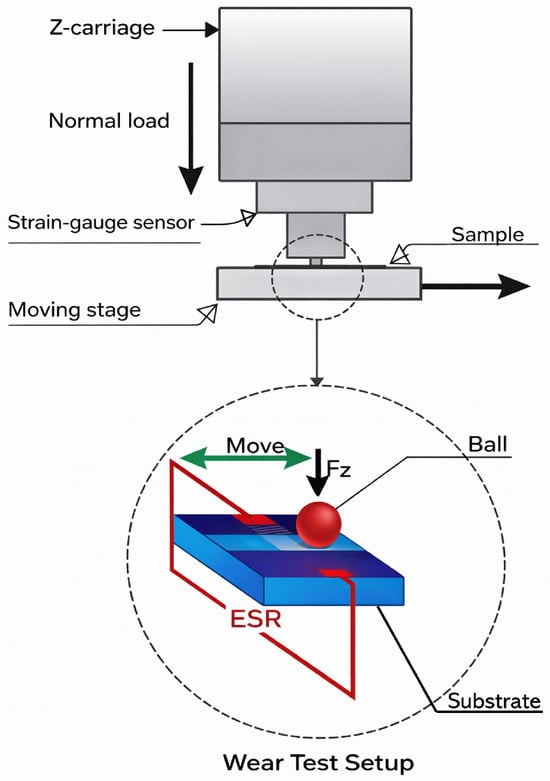

Tribological laboratory tests were carried out using a ball-on-disc unidirectional Bruker’s UMT-3 tribometer (Billerica, MA, USA) under dry conditions (see Figure 2) at room temperature. This test method consists of a 10 mm ball upper specimen (martensitic 100Cr6, Ra = 0.025 μm, 60 HRC) that slides against a flat lower specimen (FSP AA7175 composites) in a linear, back and forth sliding motion, monitoring the friction coefficient as a function of time. Wear tests were performed considering a normal load of 20 N at a constant speed of 4 mm/s and testing time t = 20 min. Wear volume was determined via optical microscopy and 3D profilometry (Olympus GX71 and Sensofar S-Neox, Terrassa, Spain) after the end of the tests. Acquired topographical data were post-processed through the metrological software Digital Surf Mountains (v 10.0) to calculate the wear volume from the 3D measurements. The specific wear rate was calculated following Equation (1).

Figure 2.

Ball-on-disc unidirectional tribological test configuration (Bruker’s UMT-3 tribometer).

Metallographic characterisation of the wear track was performed following the same methods described in Section 2.3.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of Reinforcement Particles

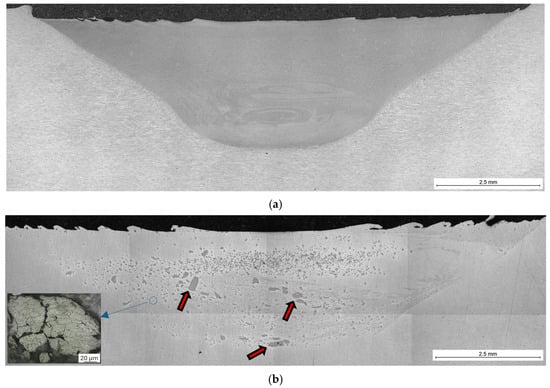

Figure 3 presents the cross-sectional macrostructure of the FSP AA7075, FSP HEA1, and FSP HEA2 samples. All specimens display a stir zone (SZ) with a trapezoidal geometry that corresponds to the tool dimensions, and none exhibit tunnels, grooves, or other macroscopic defects. Both FSP HEA1 (Figure 3b) and FSP HEA2 (Figure 3c) show a non-uniform distribution of reinforcement particles. The HEA particles appear smaller after friction stir passes, although some larger particles remain visible (indicated by red arrows). This reduction in particle size is attributed to the mechanical interaction between the tool and the particles during processing. The severe plastic deformation induced by the rotating tool during FSP imposes intense mechanical stresses on the reinforcement particles. This action promotes fragmentation of the particles, leading to a significant reduction in their size and a more homogeneous distribution within the metallic matrix. Supporting evidence is provided by a higher magnification on the left side of Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional macrostructure of the (a) FSP AA7075, (b) FSP HEA1, and (c) FSP HEA2 samples. Larger particles are indicated by red arrows.

In FSP particle-reinforced composites, the distribution of reinforcements is highly sensitive to the local flow dynamics. Studies [32,37] have shown that the shoulder region tends to accumulate particles due to its dominant surface stirring action, whereas the pin region promotes deeper dispersion through vortex-like flow patterns. Moreover, the strain rate and plastic deformation induced by the rotating tool are key drivers of dynamic recrystallization (DRX), which governs grain refinement and interfacial bonding in FSP.

The shoulder region, characterised by higher temperatures and lower strain rates, favours grain growth. In contrast, the pin region, where intense mechanical mixing occurs, is subjected to higher strain rates and localised deformation, promoting fine equiaxed grains. This spatial variation in deformation directly influences the distribution of reinforcement particles. Particles tend to accumulate near the shoulder due to radial flow and centrifugal effects, while the pin facilitates vertical and transverse dispersion, enhancing homogeneity in the stirred zone.

The interplay between thermal cycles and mechanical stirring also affects the dissolution and reprecipitation of strengthening phases, particularly in age-hardenable alloys like 7XXX series, where precipitate fragmentation and redistribution are often observed.

Fractured particles are most abundant at a depth of approximately 0.5–0.7 mm from the surface of the plate. Below this depth, in FSP HEA2, the reinforcement particles exhibit a finer size and are more homogeneous (Figure 3c), with a higher number density in the region adjacent to the FSP tool shoulder distribution than in FSP HEA1 sample (Figure 3b). This phenomenon is attributed to the distinct mechanical response of HEA particles under the intense forces and severe plastic deformation generated during FSP.

These observations are consistent with previous reports [9], in which a single FSP pass resulted in uneven particle distribution and the presence of tunnel defects, three passes produced a more uniform dispersion with defects eliminated, and five passes led to further particle fragmentation and a homogeneous distribution throughout the matrix.

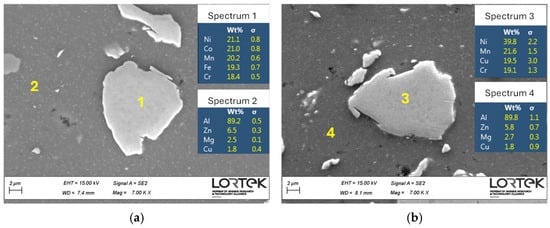

To better understand the particle–matrix interaction, Figure 4 presents FEGSEM-BSE images of the interfaces between the HEA particles and the matrix in the as-processed FSP HEA1 and FSP HEA2 samples. As described in Section 2.1, HEA1 and HEA2 differ in composition: HEA1 contains higher amounts of Fe, Co, Mn, Cr, and Ni, while HEA2 is richer in Ni, Cu, Cr, and Mn.

Figure 4.

FEGSEM-BSE images of the interfaces between the HEA particles and the matrix in the (a) FSP HEA1 and (b) FSP HEA2 samples.

EDS point analysis confirms the expected compositions for each reinforcement. Figure 4, Spectrum 1 (HEA1) shows high concentrations of Ni (21.1 wt.%), Co (21.0 wt.%), Mn (20.2 wt.%), Fe (19.3 wt.%), and Cr (18.4 wt.%), whereas Figure 4, Spectrum 3 (HEA2) displays a distinct composition with elevated Ni (39.8 wt.%) and Cu (19.5 wt.%) contents. The surrounding matrix areas (Figure 4, Spectrum 2 and 4) correspond primarily to AA7075 (≈89 wt.% Al), with minor Zn, Mg, and Cu contents.

No visible diffusion zones are observed at the particle–matrix interfaces in either case, indicating that the HEA particles remain chemically stable during friction stir processing. The sharp and well-defined interfaces suggest minimal elemental exchange and no formation of secondary phases. This behaviour is characteristic of solid-state processes such as FSP, where the peak temperature remains below the melting point of aluminium, thus limiting interdiffusion [6]. Similar observations have been reported for other HEA-reinforced aluminium composites, where clean interfaces and the absence of intermetallic phases confirm the high thermal stability of HEA reinforcements under FSP conditions [10].

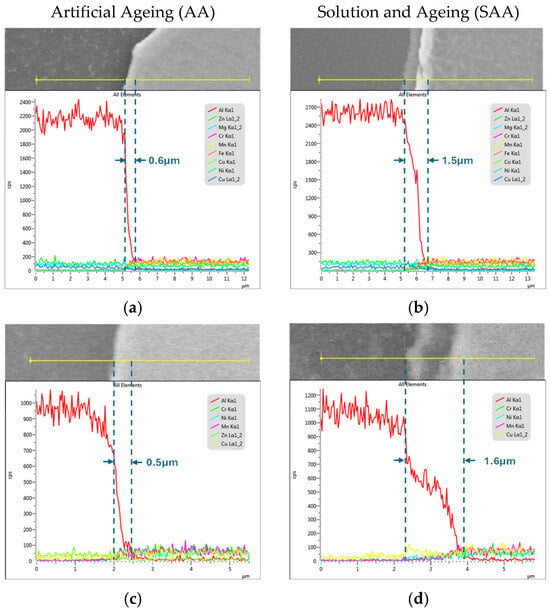

To assess elemental diffusion at the particle–matrix interfaces during the different heat treatments, Figure 5 presents FEGSEM-BSE images combined with EDS line scans for FSP HEA1 and FSP HEA2 samples after artificial ageing (AA) and solution plus artificial ageing (SAA) treatments. The compositional profiles reveal a clear gradient between the aluminium matrix (red line) and the HEA reinforcements, indicating interfacial diffusion phenomena.

Figure 5.

FEGSEM-BSE images combined with EDS line scans for both heat treatments (a) FSP HEA1_AA, (b) FSP HEA1_SAA, (c) FSP HEA2_AA, and (d) FSP HEA2_SAA.

In the FSP HEA1 sample, the aluminium signal progressively increases toward the particle, while the concentrations of transition metals (Ni, Co, Fe, Cr) decrease, suggesting partial diffusion of Al into the HEA phase. This interdiffusion becomes more pronounced under SAA conditions, likely due to the extended thermal exposure at solution treatment, with the diffusion layer thickness increasing from approximately 0.4 μm to 1.5 μm.

Similarly, in the FSP HEA2 sample, diffusion fronts are observed for both Al and Cu, reaching up to approximately 1.6 μm, indicating limited but measurable elemental exchange between the HEA2 particles and the surrounding aluminium matrix.

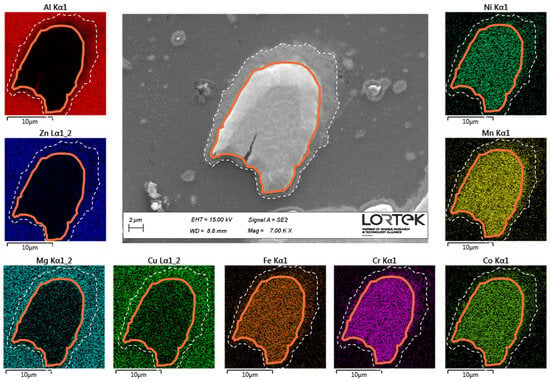

Figure 6 provides a comprehensive elemental mapping analysis of a HEA1 particle subjected to SAA treatment. In the central FEG-SEM image, the particle boundary is delineated with an orange line, while the diffusion layer between the matrix and the particle is marked with a white dashed line. The elemental maps show the distribution of Al, Zn, Mg, and Cu (originating from the matrix, left maps of Figure 6) and Ni, Mn, Co, Cr, and Fe (from the HEA1 particle, right maps of Figure 6). Notably, the interfacial diffusion zone exhibits overlapping distributions of all these elements, confirming significant interdiffusion across the interface.

Figure 6.

Elemental mapping analysis of a HEA1 particle subjected to solution treatment followed by artificial ageing (SAA).

This compositional overlap suggests that atomic mobility during SAA treatment was sufficient to promote localised diffusion, potentially leading to the formation of intermetallic phases at the interface. While such phases could enhance load transfer if they are thin and continuous, their potential brittleness must be considered. These findings align with previous studies [6,10] which report diffusion-controlled bonding in Al/HEA systems, where appropriate thermal processing enabled effective interfacial bonding while avoiding the formation of thick or brittle intermetallic layers.

3.2. Grain Structure and Precipitate Analysis of Metal Matrix

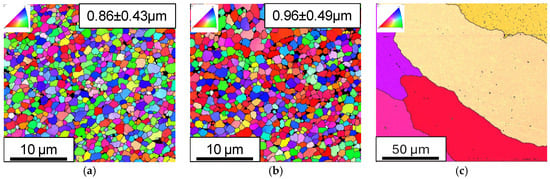

A microstructural analysis of the matrix was performed to evaluate the evolution of the grain structure before and after the applied heat treatments. As a reference, an FSP AA7075 sample without added reinforcement particles was used. Figure 7 shows the EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) maps of the FSP AA7075 reference sample and the two heat treatment conditions studied: artificial ageing (AA) and solution plus artificial ageing treatment (SAA).

Figure 7.

IPF maps of the (a) FSP AA7075 reference sample and the two heat treatment conditions studied: (b) artificial ageing (AA) and (c) solution + artificial ageing treatment (SAA).

The reference FSP AA7075 sample (Figure 7a) exhibited an equiaxed grain structure with an average size of 0.86 ± 0.43 µm, suggesting grain refinement and dynamic recrystallization during FSP. Subsequent artificial ageing at 200 °C for 5 h produced no discernible microstructural changes relative to the FSP AA7075_AA condition, as evidenced by the comparable average grain size (Figure 7b). This behaviour is consistent with the limited grain growth typically observed when thermally stable precipitates remain at grain boundaries, effectively inhibiting boundary migration [38,39].

In contrast, the SAA treatment produced a noticeably coarser grain structure (Figure 7c). At the EBSD magnification used (×3000), the grain dimensions exceeded the scan area, thereby preventing accurate grain-size quantification using this technique. Nevertheless, the grain growth appeared uniformly distributed across the processed zone. This microstructural coarsening is attributed to the dissolution of strengthening precipitates, such as MgZn2, during the solution treatment at 480 °C for 2 h. These precipitates normally exert a Zener pinning effect that inhibits grain boundary mobility and avoids extensive grain growth [11]. In this specific case, the grain size increased dramatically from 0.86 µm in the FSP condition, evolving into a markedly coarser microstructure after the full SAA treatment. This phenomenon is driven by the absence of sufficient precipitate particles to stabilise the fine-grained microstructure.

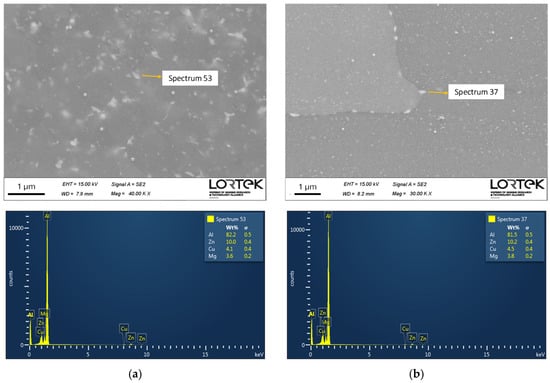

Figure 8 shows the SEM micrograph and EDS spectra of representative precipitates in both the friction stir processed (FSP) and non-processed regions of the AA7075 sample without heat treatment. The precipitates analysed in the non-processed region exhibit micrometric dimensions, approximately 0.03–0.20 µm (with some cases reaching up to 0.30 µm), and compositions enriched in Zn (≈10%), Cu (≈4.5%) and Mg (≈3.8%), consistent with the original strengthening phases of the T6 condition (η-phase: MgZn2 and S-phase: Al2CuMg). In contrast, the processed region contains smaller precipitates, approximately 0.03–0.20 µm (most concentrated below 0.08 µm), with similar chemical composition, suggesting that they correspond to the same precipitates observed in the non-processed zone. These precipitates have been partially dissolved due to the temperature reached during FSP, which has been reported to be around 480–500 °C [9,33,39].

Figure 8.

SEM micrographs and EDS spectra of representative precipitates in the AA7075 sample without heat treatment: (a) AA7075—FSP zone and (b) AA7075—non-processed zone.

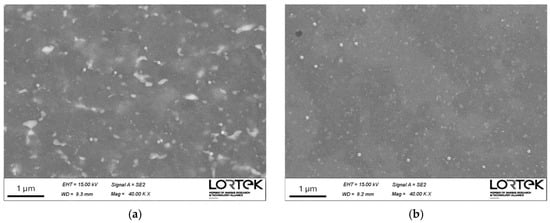

The precipitation state in HEA-reinforced samples subjected to AA and SAA heat treatments was analysed to assess the evolution induced by thermal processing. Figure 9a illustrates the microstructure of the FSP HEA2_AA sample, where precipitates similar to those observed in the untreated FSP AA7075 alloy are evident. The size of these precipitates, determined using the equivalent diameter, ranges approximately from 0.04 µm to 0.25 µm, with most values concentrated around 0.15 µm. These precipitates tend to concentrate along grain boundaries.

Figure 9.

SEM micrographs in the FSP HEA2 sample with (a) FSP HEA2_AA and (b) FSP HEA2_SAA.

In contrast, Figure 9b shows the precipitates present after the SAA treatment. These exhibit a slightly smaller size, with an approximate range of 0.02 µm to 0.09 µm, and most values below 0.06 µm. Furthermore, their distribution appears more homogeneous, extending both along grain boundaries and within the grain interior. This observation indicates that the SAA treatment promotes a finer and more uniform precipitation pattern compared to AA.

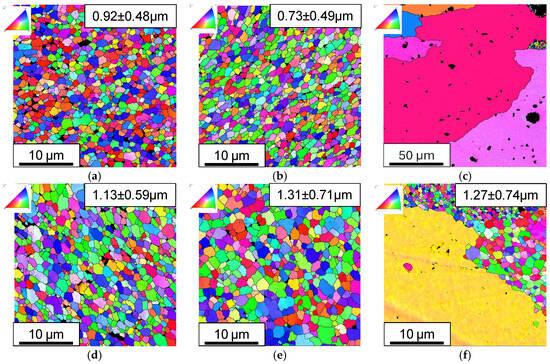

To evaluate the influence of HEA particle reinforcement on grain evolution, EBSD analysis was performed. EBSD-IPF maps with grain limits (Figure 10) show that the addition of HEA particles did not reduce grain size in the FSP condition compared to FSP AA7075, with average values of 0.92 ± 0.48 µm for FSP HEA1 and 1.13 ± 0.59 µm for FSP HEA2. A similar trend was observed after AA. Both FSP HEA1_AA (0.79 ± 0.49 µm) and FSP HEA2_AA (1.31 ± 0.71 µm) maintained a fine-grained structure comparable to that of FSP AA7075_AA. This finding can be attributed to the low temperature during the artificial ageing (AA) treatment, which was insufficient to promote grain growth. However, following SAA, FSP HEA1_SAA and FSP HEA2_SAA showed significant grain coarsening, consistent with the behaviour reported for FSP AA7075 after SAA. Nevertheless, this grain coarsening was not completely homogeneous throughout the friction stir processed (FSP) zone.

Figure 10.

IPF maps of the FSP HEA1 sample (1°row) and FSP HEA2 sample (2°row). (a) FSP HEA1, (b) FSP HEA1_AA, (c) FSP HEA1_SAA, (d) FSP HEA2, (e) FSP HEA2_AA, and (f) FSP HEA2_SAA.

The inhomogeneous grain growth observed in FSP HEA1 and FSP HEA2 after SAA can be attributed to the non-uniform distribution of reinforcement particles, which results from the different material flow patterns generated by the FSP tool in regions influenced by the tool shoulder and pin. Areas with a higher concentration of reinforcement particles are more effective at pinning grain boundaries during solution treatment compared to regions with fewer particles. In FSP HEA1_SAA, grain coarsening was more pronounced because the reinforcement particles were larger and tended to agglomerate more than in FSP HEA2_SAA, where a fine grain is observed in some areas (1.27 ± 0.74 µm) due to better particle dispersion.

This behaviour aligns with stabilisation mechanisms commonly associated with Zener-type effects, where finely dispersed HEA particles hinder grain boundary migration during thermal exposure [40]. Similar behaviours have been reported in Al-based composites reinforced with HEA phases, such as AlCoCrFeNi–5083Al processed via submerged FSP, as demonstrated by Yang et al. [41] in AlCoCrFeNi-reinforced 5083Al composites processed via submerged FSP.

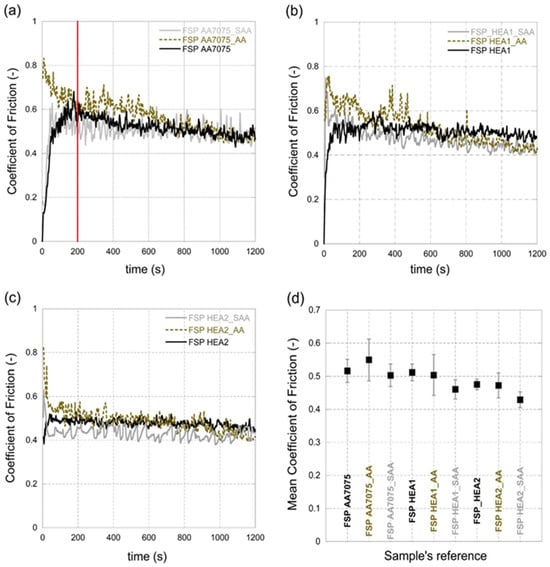

3.3. Tribological Behaviour

Figure 11 presents the evolution of the coefficients of friction (CoF-s) generated during the tribological tests carried out on each of the FSP AA7075 composites considered. The onset of the steady-state regime is indicated in Figure 11a as a red line at t = 200 s. In the case of FSP AA7075, the SAA treatment tends to reduce this transition time, providing a highly stable signal at lower testing times. A similar trend, or even a slight reduction in the CoF, is observed in the case of FSP AA7075 HEA1 and HEA2 composites (Figure 11b,c), revealing the benefits of applying this thermal treatment on the tribological material response. This behaviour can be attributed to the microstructural strengthening induced by the SAA treatment and, in the case of the composites, to the formation of a thicker HEA/Al diffusion layer, which improves load transfer and reduces localised plastic deformation during friction.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the coefficients of friction (CoF-s) generated during the tribological tests: (a) FSP AA7075, (b) FSP HEA1, (c) FSP HEA2, and (d) mean coefficient of friction vs. sample’s reference.

Figure 11d shows that the use of the HEA2 particles on the FSP composite induces a reduction in the mean friction coefficient when thermal untreated samples are considered. For thermal treated composites, the SAA samples show a reduction in the mean friction coefficient, being more significant in the case of the HEA2-based composite. Among the composites and thermal treatments considered, the FSP HEA2_SAA sample showed the lowest value of the mean friction coefficient.

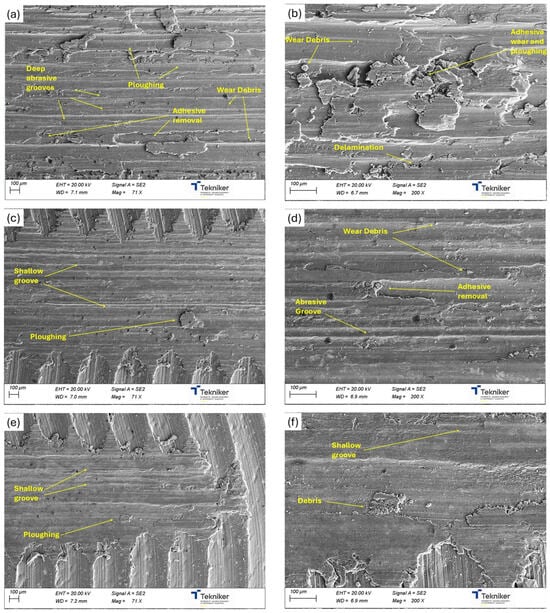

The characteristics of the wear scars were analysed via SEM to elucidate the wear mechanisms in the FSP AA7075 composites under the SAA thermal treatment (Figure 12). It is worth noting that the unreinforced FSP aluminium alloy (FSP AA7075) experienced plastic deformation, wear debris, and deep abrasive grooves formation. Additionally, severe surface damage is clearly visible in the form of adhesive wear and ploughing (Figure 12a,b). The involvement of HEA particles as a reinforcement, however, leads to the formation of smooth abrasive grooves and minor signs of adhesive wear events (Figure 12c–f). As it was reported by different authors [36,42], hard HEA particles tend to reduce the plastic deformation on the contact surface, which is connected to the reduction in the friction coefficient. In this context, HEA particles act as local load-bearing elements, reducing the real contact area between the steel counterbody and the aluminium matrix and limiting adhesive wear and ploughing mechanisms.

Figure 12.

SEM morphology of worn surfaces of (a,b) FSP AA7075_SAA, (c,d) FSP HEA1_SAA, (e,f) FSP HEA2_SAA.

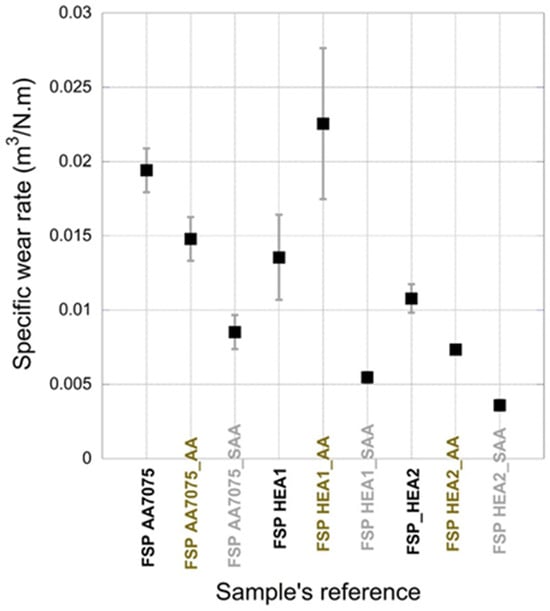

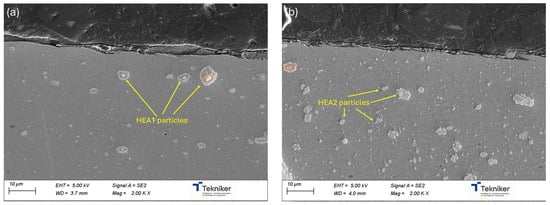

Figure 13 shows the specific wear rate obtained for each FSP AA7075 composites and thermal treatment considered. As in the case of the friction coefficient evolution, a significant reduction in the wear rate was observed for the SAA thermal treatment samples, compared with the untreated and AA-treated ones. Among the composites considered, the one containing HEA2 particles displays the minimal wear rate. This trend has been reported for AMCs with HEA particles embedded in the matrix which induce changes in the microstructure and promoting multiple hard phases, reducing the friction and improving wear resistance. According to [14], the concentration of HEA particles on the surface reduces the contact events between the steel counter body with the soft Al matrix. This effect would be more pronounced for non-agglomerated HEA particles homogeneously distributed in the matrix. Figure 14 shows the SEM characterisation of the cross-section of the FSP AA7075 composites near the surface. As it is worth noting, the density of HEA2 particles is higher and exhibits a more homogenous distribution in the Al matrix, which would contribute to better performance of this HEA2-based composite in terms of wear reduction.

Figure 13.

Specific wear rate as a function of HEA particles and thermal treatments considered as sample’s reference.

Figure 14.

SEM morphology of the cross-section of FSP AA7075 composites near the surface: (a) FSP HEA1_SAA. (b) FSP HEA2_SAA. The HEA particle and the interfacial bonding with the matrix are depicted following the same colour criteria followed in Figure 6.

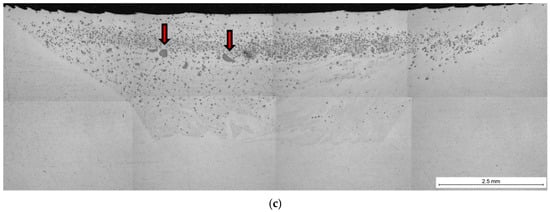

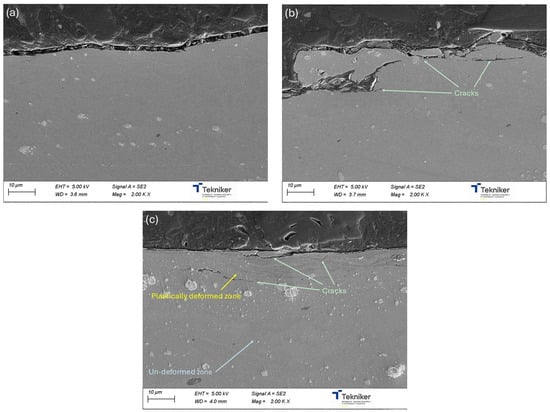

Figure 15 shows the SEM microstructural examination of the sub-surface analysis corresponding to the wear scar of the FSP AA7075_SAA without HEA particles and FSP HEA1_SAA and FSP HEA2_SAA composites. The plastically deformed zone is more relevant in the case of the FSP HEA2_SAA composite. Additionally, the onset of fatigue cracks is clearly visible in this composite, leading to surface fragmentation in some locations. These events are hardly visible in the case of the FSP HEA1 composite and the FSP AA7075 reference. According to this result, both the higher density of HEA2 particles and the weaker interfacial bonding of these reinforcements with the Al matrix induce a lower mechanical stress accommodation of this composite. Hence, a proper tune of the particle density and the interfacial bonding in the matrix is needed to obtain a trade-off between low wear rate and high mechanical response of the FSP HEA1_SAA and FSP HEA2_SAA composites.

Figure 15.

SEM morphology of the sub-surface of the wear scar of (a) the FSP AA7075_SAA reference, (b) FSP HEA1_SAA, and (c) FSP HEA2_SAA.

These results indicate that although a higher HEA particle density improves wear resistance, an adequate balance between particle distribution and interfacial bonding is required to avoid excessive sub-surface damage.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the microstructural evolution of AA7075-based metal matrix composites reinforced with high-entropy alloy (HEA) particles and processed via FSP was examined, with particular emphasis on the effects of post-processing heat treatments. Based on the obtained results, the following conclusions can be drawn.

- The distribution of HEA particles within the stir zone is strongly influenced by local flow patterns during FSP. More homogeneous dispersion is achieved through severe plastic deformation and multiple passes.

- As-processed composites exhibit sharp, well-defined particle–matrix interfaces with minimal elemental exchange, confirming the thermal stability of HEA reinforcements under FSP conditions. However, post-processing heat treatments (AA and SAA) promote interfacial diffusion, forming thin diffusion layers.

- Grain refinement achieved during FSP remains stable after AA due to precipitate pinning, but SAA induces significant grain coarsening in unreinforced samples. HEA-reinforced composites exhibit heterogeneous grain growth after SAA, as regions with higher HEA particle density retain finer grains, highlighting the critical role of particle dispersion in microstructural stability.

- The combination of HEA particle reinforcement and SAA thermal treatment significantly improves the tribological performance of AA7075 composites, reducing both the coefficient of friction and the specific wear rate compared to untreated or unreinforced samples.

- HEA particles, particularly HEA2, enhance wear resistance by promoting hard phases and reducing plastic deformation at the contact surface. This effect is amplified when thermal treatment is applied.

- Despite improved wear behaviour, excessive particle density and weak interfacial bonding in HEA-based composites can lead to sub-surface fatigue cracking. Therefore, optimising particle distribution and interface strength is essential to balance wear resistance with mechanical integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.-S. and J.V.; Methodology, L.G.-S., J.V. and I.Q.; Validation, J.V. and I.Q.; Formal Analysis, L.G.-S., J.V. and I.Q.; Investigation, L.G.-S., J.V., I.Q. and E.A.; Resources, L.G.-S., J.V. and I.Q.; Data Curation, L.G.-S., J.V. and I.Q.; Writing—Original Draft, L.G.-S.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.G.-S., J.V. and I.Q.; Visualization, J.V. and E.A.; Supervision, J.V.; Funding Acquisition, L.G.-S. and E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Industry Department of the Basque Government through the ELKARTEK-ATLANTIS (KK-2024/00061) project.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to some IPR, confidentiality issues and restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to David González Manso for his assistance in conducting the welding experiments. The authors extend their thanks to Oihan Arina and Jon Cuadrado for their expertise in preparing samples for microstructural analysis and to Nekane Paredes for the support in generating schematic images of the processing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sarmah, P.; Gupta, K. Recent Advancements in Fabrication of Metal Matrix Composites: A Systematic Review. Materials 2024, 17, 4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil, S.; Raguraman, M.; Thamarai Manalan, D. Manufacturing Processes & Recent Applications of Aluminium Metal Matrix Composite Materials: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 5934–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Mahant, D.; Upadhyay, G. Manufacturing of Metal Matrix Composites: A State of Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 26, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, J.; Fernández-Calvo, A.I.; Aldanondo, E.; Irastorza, U.; Álvarez, P. Friction Stir Weldability at High Welding Speed of Two Structural High Pressure Die Casting Aluminum Alloys. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K. Friction Stir Process: A Green Fabrication Technique for Surface Composites—A Review Paper. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Prakash, U.; Kumar, B.V.M. Surface Composites by Friction Stir Processing: A Review. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 224, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Vanitha, C. Corrosion Behaviour of Al 7075/TiC Composites Processed through Friction Stir Processing. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 15, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malopheyev, S.S.; Zuiko, I.S.; Mironov, S.Y.; Kaibyshev, R.O. Microstructural Aspects of the Fabrication of Al/Al2O3 Composite by Friction Stir Processing. Materials 2023, 16, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, D.; Kasiri Asgarani, M.; Amini, K.; Gharavi, F. Influence of Heat Treatment on Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of the Al2024/SiC Composite Produced by Multi–Pass Friction Stir Processing. Measurement 2017, 104, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanesh Prabhu, M.; Elaya Perumal, A.; Arulvel, S. Development of Multi-Pass Processed AA6082/SiCp Surface Composite Using Friction Stir Processing and Its Mechanical and Tribology Characterization. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 394, 125900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.M.; Abdullah, M.E.; Rohim, M.N.M.; Kubit, A.; Aghajani Derazkola, H. AA5754–Al2O3 Nanocomposite Prepared by Friction Stir Processing: Microstructural Evolution and Mechanical Performance. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boopathi, S.; Thillaivanan, A.; Pandian, M.; Subbiah, R.; Shanmugam, P. Friction Stir Processing of Boron Carbide Reinforced Aluminium Surface (Al-B4C) Composite: Mechanical Characteristics Analysis. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 2430–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, H.G.; Badheka, V.J.; Kumar, A. Fabrication of Al7075/B4C Surface Composite by Novel Friction Stir Processing (FSP) and Investigation on Wear Properties. Procedia Technol. 2016, 23, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenrayan, V.; Shahapurkar, K.; Natarajan, P.; Bhaviripudi, V.R.; Tirth, V.; Algahtani, A.; Petrů, J.; Bashir, M.N.; Soudagar, M.E.M. Wear Behaviour of Hybrid Ceramic Reinforced FSP Surface Composite at Varying Temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satish Kumar, T.; Shalini, S.; Krishna Kumar, K. Effect of Friction Stir Processing and Hybrid Reinforcement on Wear Behaviour of AA6082 Alloy Composite. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 026507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankachan, T.; Prakash, K.S.; Kavimani, V. Investigating the Effects of Hybrid Reinforcement Particles on the Microstructural, Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Friction Stir Processed Copper Surface Composites. Compos. B Eng. 2019, 174, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla Ramezani, N.; Davoodi, B. Evaluating the Influence of Various Friction Stir Processing Strategies on Surface Integrity of Hybrid Nanocomposite Al6061. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasava, A.; Singh, D. Comparative Analysis of Reinforcement Addition Techniques on Fabricated Hybrid Surface Composite of AA7075-T651/WC/BN through Friction Stir Processing. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 2874–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.X.; Solomon, D.; Reinbolt, M. Friction Stir Processing of Particle Reinforced Composite Materials. Materials 2010, 3, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, G.; Qu, T.; Fang, G.; Bai, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, J.; Yao, D.; et al. Simultaneously Enhancing Mechanical Properties and Electrical Conductivity of Aluminum by Using Graphene as the Reinforcement. Mater. Lett. 2020, 265, 127440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaszko, J.; Sajed, M. Technological Aspects of Producing Surface Composites by Friction Stir Processing—A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshaim, A.B.; Moustafa, E.B.; Alazwari, M.A.; Taha, M.A. An Investigation of the Mechanical, Thermal and Electrical Properties of an AA7075 Alloy Reinforced with Hybrid Ceramic Nanoparticles Using Friction Stir Processing. Metals 2023, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, J.; Givi, M.K.B.; Barmouz, M. Mechanical and Microstructural Characterization of Cu/CNT Nanocomposite Layers Fabricated via Friction Stir Processing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 78, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghian, M.; Bayat, F. Copper Matrix Surface Composites Fabricated by Friction Stir Processing: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 140, 5687–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Mangish, A.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, A.; Ahn, B.; Kumar, V. A Review on High-Temperature Applicability: A Milestone for High Entropy Alloys. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 35, 101211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Li, Y. Recent Advances in the Performance and Mechanisms of High-Entropy Alloys Under Low- and High-Temperature Conditions. Coatings 2025, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, H.; Abedi, H.R.; Zhang, Y. A Study on Outstanding High-Temperature Wear Resistance of High-Entropy Alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2201915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; Tieu, A.K.; Huynh, K.K.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Deng, G. Wear Behaviour of High Entropy Alloys CrFeNiAl0.3Ti0.3 and CrFeNiAl0.3Ti0.3–Ag Roll Bonded with Steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 7685–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünbül, S.E. A Study on the Structural, Wear, and Corrosion Properties of CoCuFeNiMo High-Entropy Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 996, 174881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Haghdadi, N.; Shamlaye, K.; Hodgson, P.; Barnett, M.; Fabijanic, D. The Sliding Wear Behaviour of CoCrFeMnNi and AlxCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloys at Elevated Temperatures. Wear 2019, 428–429, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Gao, M.C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, J. Tribological Properties of AlCrCuFeNi2 High-Entropy Alloy in Different Conditions. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47, 3312–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Wu, B.; Shang, S.; Lei, B.; Tang, H.; Xu, Z. Review: Advances in Friction Stir Processing of Aluminum Matrix Composites. J. Manuf. Sci. 2025, 60, 15421–15461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Robson, J.D.; Sanders, R.E.; Liu, Q. Microstructural Evolution of Cold-Rolled AA7075 Sheet during Solution Treatment. Materials 2020, 13, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y. Producing of FeCoNiCrAl High-Entropy Alloy Reinforced Al Composites via Friction Stir Processing Technology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 110, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Meng, X.; Wan, L.; Dong, Z.; Huang, Y. Friction Stir Processing of High-Entropy Alloy Reinforced Aluminum Matrix Composites for Mechanical Properties Enhancement. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 792, 139755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, S.A.; Anaele, J.U.; Aikulola, E.O.; Anamu, U.S.; Koko, A.; Bodunrin, M.O.; Alaneme, K.K. Aluminium Matrix Composites Reinforced with High Entropy Alloys: A Comprehensive Review on Interfacial Reactions, Mechanical, Corrosion, and Tribological Characteristics. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 8161–8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasava, A.; Singh, D. Effect of Different Polygonal Pins with Scroll Shoulder on Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Hybrid Surface Composites of AA7075–T651/BN/WC. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2025, 126, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbi, A.; Samuel, A.M.; Zedan, Y.; Songmene, V.; Samuel, F.H. Effect of Aging Treatment on the Strength and Microstructure of 7075-Based Alloys Containing 2% Li and/or 0.12% Sc. Materials 2023, 16, 7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Liu, J. Precipitation Thermodynamics in an Al–Zn–Mg Alloy with Different Grain Sizes. Metals 2024, 14, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, P.R.; Fonseca, G.S. Grain Boundary Pinning by Particles. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 638–642, 3907–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Dong, P.; Yan, Z.; Cheng, B.; Zhai, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W. AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy Particle Reinforced 5083Al Matrix Composites with Fine Grain Structure Fabricated by Submerged Friction Stir Processing. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 836, 155411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.K.; Singh, A. Mechanical and Dry Sliding Tribological Characteristics of Aluminium Matrix Composite Reinforced with High Entropy Alloy Particles. Tribol. Int. 2024, 191, 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.