Abstract

The article examines the effect of different types of two-layer nanostructured coatings (cVIc and nACVIc) deposited on three types of steel substrates, 45S20, C45E, and 42CrMo4, to determine the resistance to adhesive wear of the substrate/coating system. The samples underwent different heat treatments, including normalising, quenching, and quenching and tempering, followed by PVD (physical vapour deposition) treatment at temperatures of 450 °C (cVIc) and 460 °C (nACVIc). The thickness of the cVIc layers for all three steels ranged from 0.9 to 3.4 μm, while the thickness of the nACVIc layers on all steels was slightly greater, ranging from 1.9 to 3.1 μm. Tribological tests were conducted using the pin-on-disc method, and the results were statistically analysed. Results indicate that steel grade, heat treatment, and PVD coating significantly affect adhesive wear resistance, with the type of PVD coating showing the strongest influence. For all three steels, quenched and uncoated samples exhibited the lowest adhesion wear index values. Normalised and quenched with or without tempering steels coated with cVIc layer exhibit higher resistance to adhesive wear due to better adhesion of the layer compared to the nACVIc coating.

1. Introduction

Improving the performance of tools and machine parts and reducing wear has long been achieved by selecting a suitable material [1,2,3,4]. However, to change the performance characteristics, it is not always necessary to change the properties of the base material, but rather the surface properties, which are often decisive for the technical usability of the chosen material.

The two basic methods of surface treatments are modification and coating [5]. In modification, the surface layer grows from the surface towards the core of the treated material, while in coating, the surface layer is formed exclusively on the material surface [6]. One of the surface coating techniques is physical vapour deposition (PVD), which produces a surface layer that differs in composition from the base material and does not diffuse into the substrate [7].

PVD coatings are particularly valued for their high hardness, wear and oxidation resistance, thermal stability and lubricity and are therefore ideal for improving the performance of various components [8,9]. It is important to emphasise that the process is conducted at lower temperatures (below 500 °C), which prevents any microstructural changes in the base material, ensuring that the pre-existing properties are preserved and that shape and dimensions remain stable. Therefore, steels that are tempered at temperatures higher than 500 °C are also suitable for this process (e.g., high-speed steels, hot-work steels, steels for quenching and tempering) [10].

In recent years, various deposition methods with different coatings and substrate materials have been investigated in detail, and promising results have been achieved. Coatings such as TiN, TiCN, TiAlN, and diamond-like carbon (DLC) significantly improve surface microhardness, physical and chemical properties and contribute to a longer lifetime and better performance of the treated parts. By using multilayer coatings, these properties can be further optimised through synergy effects. The combination of different layers improves hardness, toughness, oxidation resistance and thermal stability [11,12,13,14].

In the study [9], the erosion, abrasion and impact wear resistance of five coatings (TiN, TiCN, TiAlN-ML, AlTiN-G, nc-AlTiN/a-Si3N4) applied to carbide were tested. The results showed a correlation between hardness and wear resistance, with nc-AlTiN/a-Si3N4 exhibiting the best relative material performance. Compared to the Al-containing coatings, TiN showed the lowest impact resistance but the best erosion resistance.

Bilek et al. investigated the microhardness and modulus of elasticity of TiCN and AlTiN (produced by PVD) and of TiCN + TiC + Al2O3 multilayers (produced by moderate temperature chemical vapour deposition, MT-CVD). TiCN coating exhibited the highest overall hardness and modulus of elasticity (2857 HV and 649 GPa, respectively), and the best ratio between hardness and elasticity [14].

The study [10] is the first application of the MgGd alloy concept to a TiAlN matrix. To investigate the influence of Al content on the properties of TiAlMgGdN coatings on 100Cr steel, Ulrich et al. varied the Al/Mg ratio from 15/48 at.% to 63/0 at.%. The results showed that increasing the Al content led to a decrease in crystallite size (from 15.2 to 4.8 nm) and an increase in hardness (from 13.5 to 18.5 GPa) and corrosion resistance, confirming the synergistic effect of Al and rare earths.

The results of the study [1] confirm the superiority of the PVD coating. In this study, graphite-containing GG25 grey cast iron and GGG60 nodular cast iron were used as the base material, and the samples were subjected to various surface treatments (freckle casting, induction hardening and PVD-CrN coating). The abrasion resistance of the obtained coatings was tested using HS10.4-3-10 high-speed steel as a counter body, and the test results showed that PVD-coated samples significantly outperformed the other surface treatments.

Siow et al. investigated the influence of carbon content and coating composition on the properties of TiCxN1−x coatings on WC-6Co cemented carbide. Both the substrate and the coatings were prepared in-house: the substrate samples by powder metallurgy and the coatings by cathodic arc PVD. Although the deposition of TiCxN1−x coatings significantly increased the surface roughness, the friction factor was reduced, resulting in improved surface lubricity. The results indicated that the coating properties are influenced by the carbon content. Specifically, a higher percentage of carbon leads to improvements in microhardness, lubricity, the friction factor, and the modulus of elasticity. However, it also results in a decrease in thermal conductivity [15].

Feng et al. compared different coatings (TiN, TiNC, CrN/TiNC, and TiN/TiNC) on 9Cr18 steel. The ball-on-disc method with a GCr15 ball was used to test the friction and wear resistance. The TiN coating demonstrated the highest hardness and the friction factor (~0.73), while also exhibiting the lowest adhesion to the substrate. TiN/TiNC had the lowest friction factor (~0.25) and better wear resistance [16].

Liu et al. compared the properties of TiAlN (obtained by PVD), TiN-Al2O3-TiCN-TiN multilayer (by CVD) and diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings (by plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition, PECVD) on cermet inserts. The highest adhesion strength and hardness were achieved with TiN-Al2O3-TiCN-TiN coatings, while these values were lowest for DLC coatings. The best wear resistance for all three coatings was found at the cutting parameters of 1100 rpm, 0.2 mm depth and 0.1 mm/rev feed rate, with TiN-Al2O3-TiCN-TiN having the worst and DLC the best wear resistance [17].

Previous research on the properties and applications of PVD coatings mostly relates to tools and moulds that are exposed to adhesive wear. This process, often referred to as solid-state welding, occurs when the adhesive forces between the materials overcome the inherent properties of the materials. It is particularly common in metal-to-metal contact when lubrication is inadequate. Adhesive wear is also favoured by difficult working conditions, which include high temperatures and high loads, as well as rapid movements of the elements in contact. For this reason, this type of wear is often found in gears and bearings, where it can lead to rapid surface damage due to the appearance of pits or the accumulation of material on a surface, and result in functional failure. The specified parts are manufactured of structural steels that are often used in the hardened and tempered state, but also as normalised and quenched (without tempering). The aforementioned heat treatments achieve high values of yield strength and tensile strength, along with high toughness and dynamic resistance. Consequently, so treated steels are used for mechanical, especially dynamically, highly loaded parts of machines and devices that are not subject to heavy wear [18]. For applications requiring high wear resistance, these steels require surface modification or coating with some of the available technologies.

In the recent literature, there are very few studies on PVD coatings for this group of heat-treatable steels, which are important for the production of movable machine parts. Therefore, intensive research on the influence of PVD coatings on their properties is crucial because these steels are currently facing increasingly complex and often contradictory exploitation requirements, which demand modifications and optimisation of their mechanical and tribological properties. The mechanical properties of the base material are achieved through appropriate bulk heat treatment; however, for adhesion resistance, appropriate coatings are most often crucial. This article focuses on PVD coating technology because the process temperatures are lower than the tempering temperature of the steel, which does not change the properties of the base material, but only modifies its surface. In order to gain a more detailed insight into the impact of PVD coatings, this study includes three heat treatable structural steels (45S20, C45E, and 42CrMo4) subjected to different heat treatments (normalising, quenching without and with tempering) with the intention of selecting the optimal combination of steel, heat treatment and coating type that will show the best tribological response in terms of reducing adhesive wear.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was carried out on three steel grades for quenching and tempering at high temperatures: 45S20, C45E, and 42CrMo4, supplier Strojopromet d.o.o., Zagreb, Croatia. The 45S20 steel is a structural steel with improved machinability intended for processing on automatic machines with high cutting speeds. C45E non-alloy steel is suitable for diametres up to 40 mm due to its low hardenability. Exceptionally, it is also used in the normalised condition for diametres up to 100 mm and less stressed parts. Alloy steel 42CrMo4 in the normalised, quenched and tempered, or only quenched or state is intended for parts with larger dimensions, diametres up to 100 mm, and for higher working loads [19,20].

The chemical composition of the tested steels was analysed by the spectrometric method on the Belec Compact Port device, manufactured by Belec Spektrometrie Opto-Elektronik GmbH, Georgsmarienhütte, Germany.

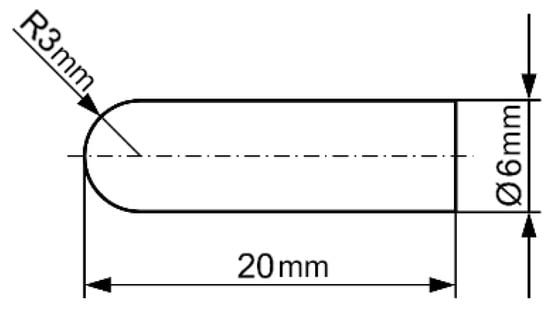

To evaluate resistance to adhesive wear, 54 samples (18 samples from each steel grade) were prepared according to Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Shape and dimensions of the specimens for the adhesive wear resistance test.

Before the PVD process, the samples of each steel type were heat-treated according to the parameters specified in Table 1. Specifically, 6 samples underwent normalising, 6 samples were treated by quenching and tempering, and 6 samples were subjected to quenching only (without subsequent tempering).

Table 1.

Heat treatment parameters: ϑN—normalising temperature; ϑa—austenitising temperature; ϑP—tempering temperature, t—heating time.

After heat treatment, 4 of the 6 identically heat-treated samples of a certain steel were PVD-coated (two with cVIc coating, two with nACVIc coating), while 2 samples were tested without coating. The PVD coatings cVIc and nACVIc (Table 2) were selected due to the requirements for high surface hardness and low friction factor. The application temperatures of these coatings are in the range of the use of structural steels for quenching and tempering. The cVIc is a two-layer coating featuring a nanostructure composed of a combination of titanium carbonitride (TiCN) and carbon-based coating (CBC). The TiCN coating is a conventional ceramic coating with a characteristic dark grey colour. This coating is created by the substitution of N atoms by C atoms in the crystal lattice of TiN. TiC and TiN have the same crystal structure, so that they are completely soluble in each other, and the positions of the N and C atoms can be easily exchanged. TiCN coating combines the advantages of single-layer TiC and TiN coatings and has a higher hardness and a lower friction factor than TiN, as well as greater chemical inertness than TiC coating. The outer CBC coating is a basic carbon coating that is used as a dry lubricant to reduce the friction factor. The nACVIc is also a two-layer nanostructured coating created by the combination of nACRo + CBC layers. nACRo (nc AlCrN/a-Si3N4) is a nanocomposite coating that requires an additional titanium layer on the base material to improve adhesion. It is based on a CrN adhesion layer, has a central AlTiCrN layer for toughness, and an upper AlCrSiN layer that ensures thermal stability and wear resistance. CBC is an external carbon coating designed to reduce friction [21].

Table 2.

Nominal properties of cVIc and nACVIc PVD coatings.

Cathodic arc deposition with sample rotation was carried out at the Gazela-Platit company (Krško, Slovenia). For the cVIc and nACVIc coating, the process temperature was 450 °C and 460 °C, respectively. The coating was applied in several phases. The first phase was heating up to the coating temperature (for 1 h). In the second phase, electronic cleaning was performed in a vacuum chamber using a plasma etching process for 15 min. Ion bombardment serves to remove impurities and activate the surface for better coating adhesion. The third phase included a coating process lasting 3 h. After the PVD process, the samples were cooled to 100 °C for 1 h.

Surface characterisation included chemical composition analysis and coating thickness measurement using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Tescan Vega Easy Probe 3, Brno-Kohoutovice, Czech Republic, additionally equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS), Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK. The coating thickness was measured at a minimum of three positions.

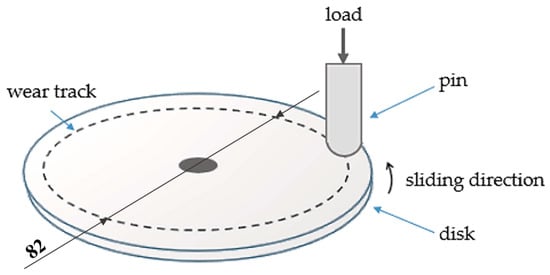

Tribological tests were performed at room temperature under dry sliding conditions using the pin-on-disc method (Figure 2). The experiments were conducted using a laboratory tribometer, Taber Abraser (Model 503, Teledyne Taber, North Tonawanda, NY, USA).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of tests on the Taber Abraser device.

A test specimen slides on a disc made of ductile cast iron EN-GJS-400-12S. Ductile cast iron was chosen because it is the optimum material for the manufacture of parts subject to adhesive wear, as shown in the study [22]. Ductile cast iron has high dynamic strength and tensile strength, good wear resistance, self-lubrication, vibration damping and good machinability due to particle deposition [19]. All samples initially showed the same roughness level as reported in [23]. The test was performed on two specimens for each state by measuring the diametre of the calotte on the specimen using a Leica DM 2500 M optical microscope (Leica AG, Wetzlar, Germany) and calculating the average volume loss. For each specimen, the counterplate was sanded with 320 grit sandpaper (corresponding to roughness class N4, i.e., Ra from 0.1 to 0.2 µm) and cleaned with alcohol to remove the influence of the previous test. At each revolution, the specimen travelled a distance of 257.6 mm (the circumference of a circle with a diametre of 82 mm), and after 1000 revolutions, the wear (friction) path was 257.6 m. In accordance with ASTM G99-23, the specimen was loaded with a force of 9.81 N, and the volume loss (ΔV) of the pin was calculated using Equation (1) [24]:

where d is the wear scar diametre (mm); R is the sphere radius on the test specimen (mm), R = 3 mm.

The influence of heat treatment, steel grade and coating type on the adhesive wear of 45S20, C45E and 42 CrMo4 steels was also statistically analysed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the significance of each input factor (and their interactions) on the output variable. The F-statistic and the p-value are generally used to evaluate the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis states that the input variables have no influence on the output at a certain level of significance. The alternative hypothesis, on the other hand, states that there is a correlation between the input and output variables. A confidence level of 95% (which corresponds to a p-value of 0.05) is used to test statistical significance. If the p-value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected in favour of the alternative hypothesis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Substrate Chemical Composition

Table 3 shows a comparison of the chemical composition of steel substrates according to the manufacturer’s data (MD) and the results obtained by chemical analysis on a Belec Compact Port device (BD) [25]. These steels generally contain between 0.2 and 0.6% C and belong to the quality and stainless steels according to their chemical composition.

Table 3.

The chemical composition of selected steels, wt.%.

3.2. Characterisation of Surface Layers

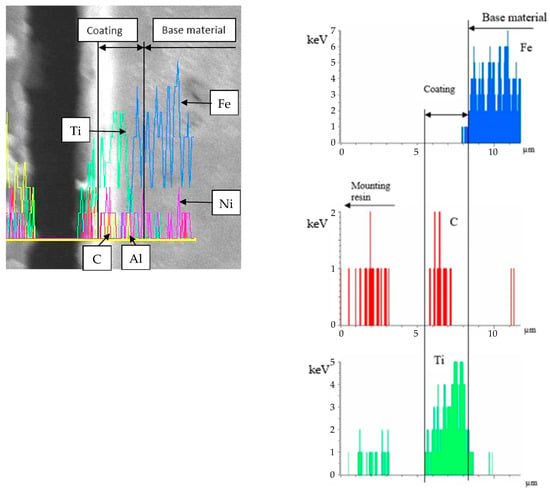

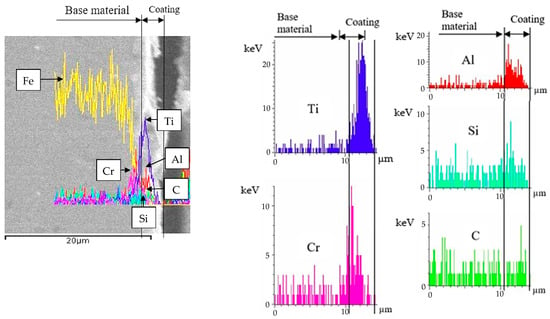

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the elemental distribution in the cVIc coating on 45S20 steel and in the nACVIc coating on C45E substrate, respectively.

Figure 3.

Line scan result of the cVIc coating on 45S20 substrate.

Figure 4.

Line scan result of the nACVIc coating on C45E substrate.

Figure 3 shows the presence of Ti and C in the coating in the range from 5.5 to 8.5 µm. Elements transferred to the mounting resin during polishing are visible up to 3 µm away. The range from 3 to 5.5 µm is the gap between the mounting resin and the coating. Titanium is the basic element in the coating, and its bond with the substrate, where the most abundant element is iron, is evident in the range from 8 to 8.5 µm.

The distribution of Ti, Cr, Al, Si, and C in the range from 10.5 to 14 µm characterises complex nACVIc layer. The coating bond with the substrate is illustrated in the range from 10 to 11 µm.

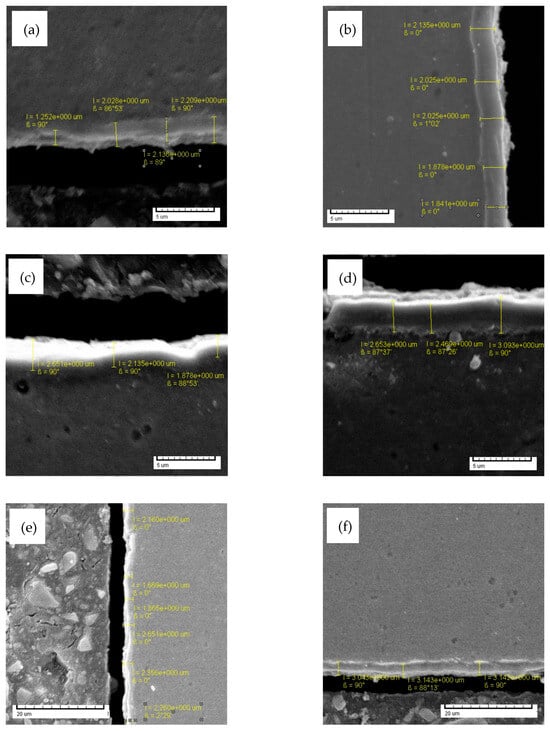

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate SEM micrographs with measured coating thicknesses for each steel grade, applied heat treatment, and coating type.

Figure 5.

The thickness of cVIc and nACVIc coating on 45S20 steel: normalised (a,b), quenched and tempered (c,d), and quenched (e,f).

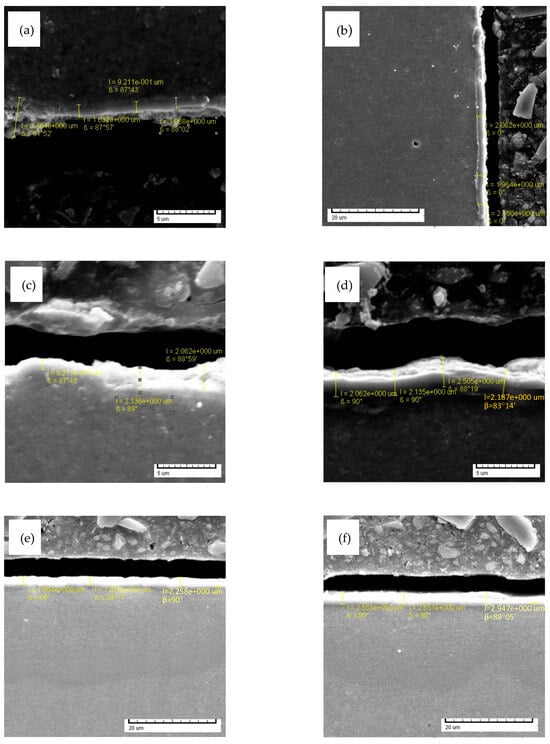

Figure 6.

The thickness of cVIc and nACVIc coating on C45E steel: normalised (a,b), quenched and tempered (c,d), and quenched (e,f).

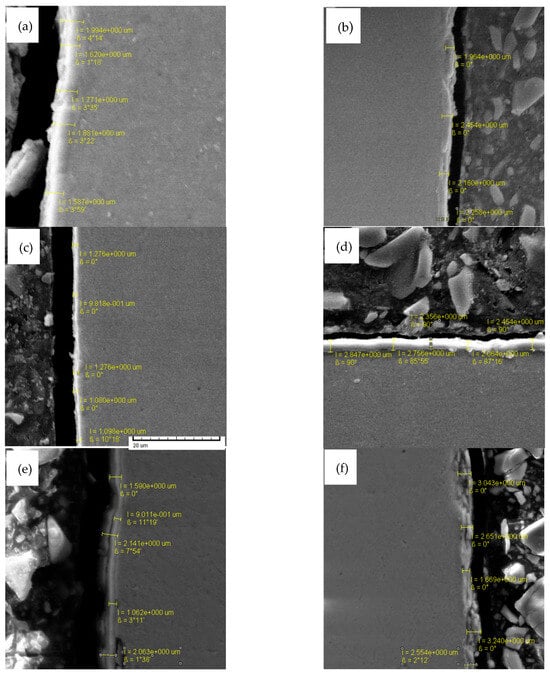

Figure 7.

The thickness of cVIc and nACVIc coating on 42CrMo4 steel: normalised (a,b), quenched and tempered (c,d), and quenched (e,f).

The thickness of the cVIc layers for tested steels ranged from 0.9 to 3.4 μm, while the thickness of the nACVIc coatings on these steels was slightly greater, ranging from 1.9 to 3.1 μm. The reason is that the coating process for the nACVIc layer involves a slightly higher temperature than that used for cVIc coatings. At elevated temperatures, the diffusion of atoms and chemical reactions occur more rapidly, which enhances the growth of the nACVIc layer. Moreover, variations in coating thickness occur due to the different distances of the samples from the evaporation source (target), with parts that are closer receiving a thicker layer.

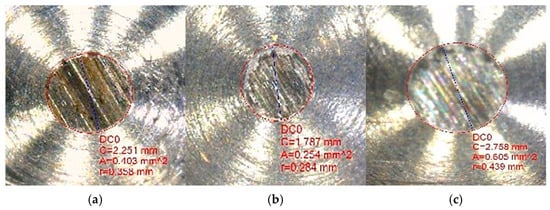

3.3. Wear Index

The diametre of the wear surface d used in Equation (1) was calculated on the basis of the wear radii measured on all samples after 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, and 1000 revolutions. An example of the determination of the wear radius is shown in Figure 8, which shows the wear surfaces on samples of quenched and tempered 42CrMo4 steel after 1000 revolutions. In Figure 8, C is the circumference of the wear surface (mm), A is the wear surface (mm2), and r is the radius of the wear surface (mm).

Figure 8.

Wear marks on quenched and tempered 42CrMo4 steel after 1000 revolutions: (a) without coating; (b) cVIc coating; (c) nACVIc coating.

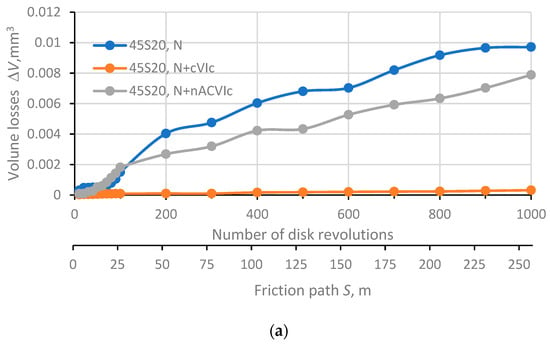

The mean values of the calculated volume losses for two repeated measurements (in the range from 0 to 1000 revolutions) for 45S20 steel in the normalised (N), quenched and tempered (Q and T), and quenched (Q) condition, with cVIc and nACVIc coating and without coating, are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Volume losses of 45S20 steel with cVIc and nACVIc layer and without coating: (a) normalised; (b) quenched and tempered; (c) quenched.

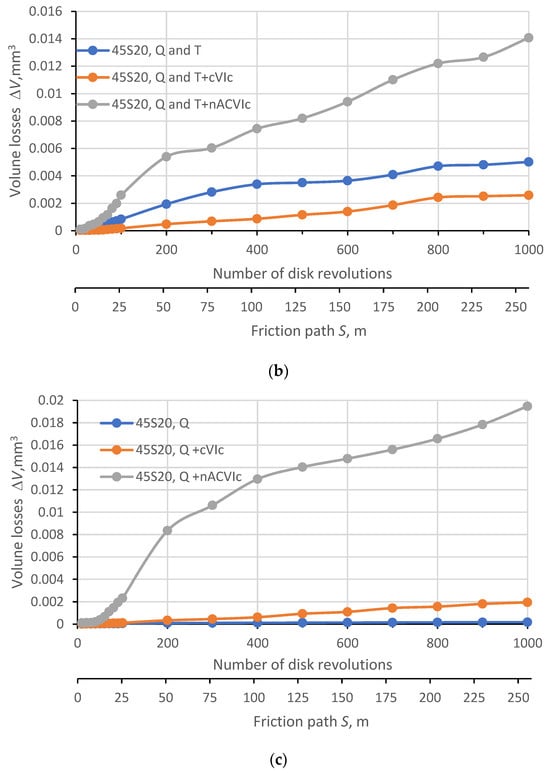

The average values of the calculated volume losses for C45E steel under all heat treatment conditions, with cVIc and nACVIc coating and without coating, are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Volume losses of C45E steel with cVIc and nACVIc layer and without coating: (a) normalised; (b) quenched and tempered; (c) quenched.

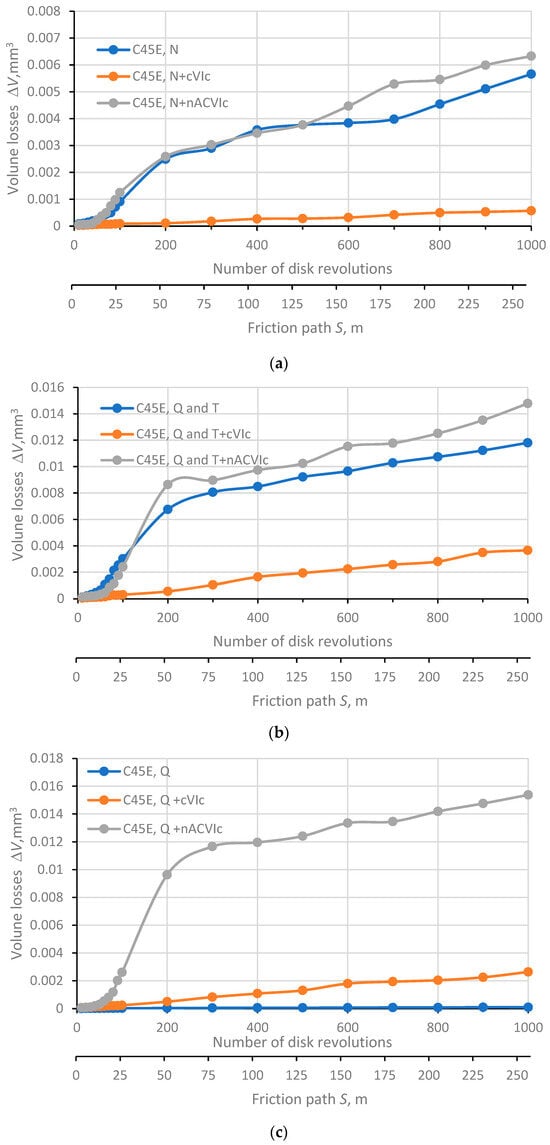

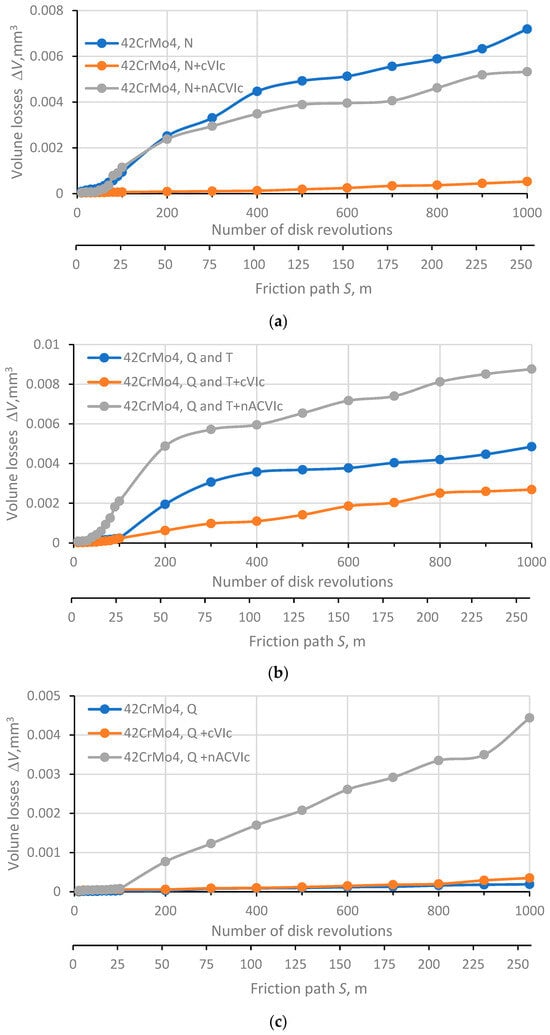

Graphical illustrations of the average volume losses for uncoated and coated samples of differently heat-treated 42CrMo4 steel are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Volume losses of 42CrMo4 steel with cVIc and nACVIc layer and without coating: (a) normalised; (b) quenched and tempered; (c) quenched.

The influence of cVIc and nACVIc PVD coatings on the adhesive wear resistance of normalised, quenched and tempered and quenched structural steels 45S20, C45E and 42CrMo4 was analysed by comparing the wear index. Wear index is used to quantify the wear resistance of different materials; materials with a lower wear index have better wear resistance. The wear index was calculated using the volume loss method after 1000 revolutions. The volume wear index is determined according to Equation (2) [23]:

where iΔV is the wear index of volume loss, ΔVf is the volume loss of the pin after 1000 revolutions of the disc (mm3), and n is the number of rotations of the disc.

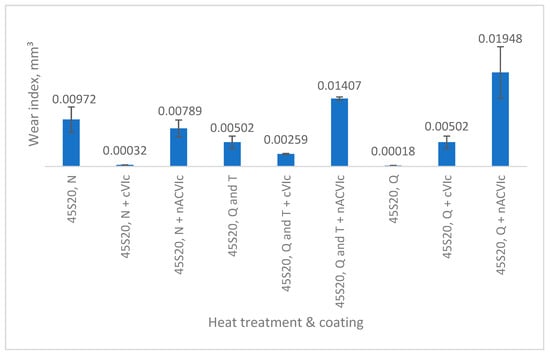

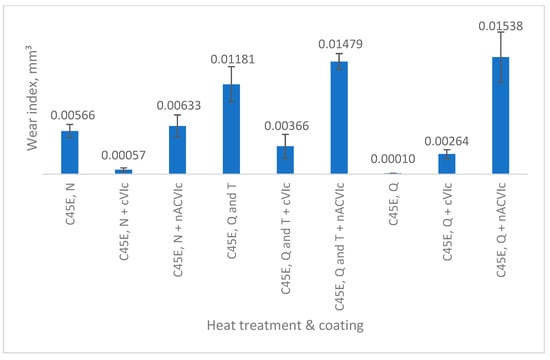

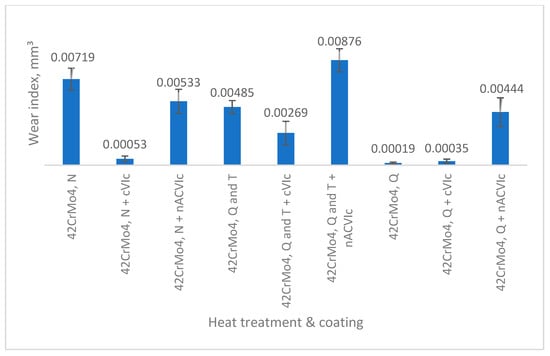

The mean wear index values, determined based on two repeated measurements for 45S20, C45E, and 42CrMo4 steels in normalised (N), quenched and tempered (Q and T), and quenched (Q) states, with cVIc and nACVIc coatings, and without a layer, are shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 12.

Wear index of 45S20 steel.

Figure 13.

Wear index of C45E steel.

Figure 14.

Wear index of 42CrMo4 steel.

A detailed comparison of the results revealed a significant difference in wear for all three types of heat-treatable structural steels, depending on the type of coating. All three steels have the lowest wear index in the quenched condition without coating, but they are very brittle and subject to mechanical fatigue, which is unfavourable for moving machine parts. The reason for the lowest wear in the quenched state without coating is that the hard PVD coating cannot peel off during adhesive wear, which would then lead to abrasive wear, as the deposited particles act as an abrasive.

The steels 45S20 and C45E presented a slightly higher wear index in the normalised condition with cVIc coating (iΔV = 0.00032 and iΔV = 0.00057, respectively). For 42CrMo4 steel, the wear index in the normalised condition with cVIc coating (iΔV = 0.00053) was slightly higher than the wear index in the quenched condition with cVIc coating (iΔV = 0.00035).

For 45S20 steel, the quenched samples with cVic coating (iΔV = 0.01407), and nACVIc layer (iΔV= 0.01948) exhibited the highest wear indices. The same applies to samples made of C45E steel, where the highest wear indices were also determined for samples in the quenched state with cVIc layer (iΔV = 0.01479) and with nACVIc coating (iΔV = 0.01538). The highest wear index for 42CrMo4 substrate was obtained from samples in the quenched and tempered condition with nACVIc coating (iΔV = 0.00876) and normalised samples without coating (iΔV = 0.00719).

If the wear indices for the individual heat treatment states are compared, it can be noted that the lowest wear occurs in the normalised steels with a cVIc coating. Non-coated samples of 45S20 and 42CrMo4 steel in the normalised condition without coating have a higher wear index than the same samples with an nACVIc coating. Samples of C45E steel with an nACVIc coating have a higher wear index than the same samples without coating. In the quenched and tempered condition, the steels with a cVIc coating characterise the lowest wear index values. Samples with nACVIc coating generally have a higher wear index than the non-coated samples or ones with cVic coating.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The results of the wear index were statistically analysed. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the influence of heat treatment, coating type and steel grade on the adhesive wear. The ANOVA was performed for two replicates per experimental design condition, and the results of the analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance of the wear index of the volume loss.

To draw conclusions about the influence of steel grade, heat treatment, and type of coating on wear resistance, a statistical analysis of the wear index after 1000 revolutions was conducted. The results are presented in Table 4. A p-value above 0.05 supports the null hypothesis that there is no effect of the input variable on the result (i.e., the variable is not significant), while a p-value below 0.05 supports the alternative hypothesis that the input variable has an effect on the result (i.e., it is significant). Analysing the variance of the wear index of volume loss of the structural steels 45S20, C45E and 42CrMo4 in Table 4, it can be concluded with 95% confidence (alpha level of 0.05) that the steel grade, heat treatment and coating type have a significant effect on the resistance to adhesive wear (all p-values are less than 0.05). Among the interactions between the input variables, the interactions between steel and coating type and between coating type and heat treatment also have a significant influence on the resistance to adhesive wear. On the other hand, the interaction between the steel grade and the heat treatment has no significant influence on the resistance to adhesive wear, with a p-value of more than 0.05.

4. Conclusions

Increased wear resistance is one of the reasons for using PVD coatings. Analysing the results of the adhesive wear resistance test revealed a significant difference in wear for all three types of heat-treated structural steels, depending on the type of coating.

For all three types of coated steels in the normalised condition and quenched with or without tempering, the least wear was observed after coating with a cVIc coating. The wear index of cVIc coatings is significantly lower than the wear index of naCVIc layer, by 82%, 90% and 96%, for quenched and tempered, quenched without tempering, and normalised steel 45S20, respectively. A similar trend can be observed in the remaining two steels, which in the normalised state show a 90% lower wear index of the cVIc layer compared to the nACVIc coating, while for the quenched and tempered state, the difference is 69% (42CrMo4) and 75% (C45E). In the case of quenched C45E steel, the cVIc coating is characterised by an 83% lower wear index than the nACVIc coating, while in the same treated 42CrMo4 steel, this difference is even greater (92%) in favour of the cVIc coating. The reason for this can be found in the better adhesion of cVIc to all steels, which, due to its chemical composition, contributes to stronger mechanical and chemical bonds between the coating and the substrate, which is not the case with the nACVIc coating, as indicated by previous research [21].

For all three tested steel grades in the quenched state, wear was lowest without a coating and highest with an nACVIc coating. Quenched samples with cVIc coating wore more than uncoated samples. Specifically, 42CrMo4 steel with cVIc coating exhibited 1.8 times higher wear than the uncoated sample, while C45E showed an even more pronounced difference, with wear increasing by 26 times. The reason for the lowest wear in the quenched state without coating is that the hard PVD coating cannot peel off during adhesive wear, which would then lead to abrasive wear, as the deposited particles act as an abrasive.

The results showed that the adhesive wear resistance of PVD coatings depends on the heat treatment, type of coating, and the steel grade, as well as on their interaction (with the exception of interaction between type of steel and the heat treatment).

It should be noted that this article refers exclusively to the results of the preliminary research. A comprehensive study within the project that is being carried out will result in a more detailed insight into the behaviour of PVD coatings on structural steels for quenching and tempering by establishing a correlation with substrates and coatings hardnesses, substrate microstructures, coatings morphology, and surface roughness before and after coating, which is currently not possible and represents a potential limitation in terms of validation and analysis of the obtained results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, I.K. and D.Ć.; methodology, I.K. and S.G.; software, A.M.; validation, I.K. and A.M.; formal analysis, I.K. and S.G.; investigation, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K., S.G. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, I.K. and D.Ć.; visualisation, I.K., S.G., D.Ć. and A.M.; supervision, I.K. and D.Ć. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research paper was funded by the University of Slavonski Brod through the institutional research project Advanced modelling and optimization of compact heat exchangers for integration into renewable energy systems (MOKIT), financed by the EuropeanUnion–NextGenerationEU. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arslanbulut, E.; Bulut, M.; Selçuk, B. Wear resistance of cams made of lamellar and spheroidal graphite cast iron with different surface treatments. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 065907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Gyurika, I.G.; Korim, T.; Jakab, M. Comparison of the wear and friction properties of titanium nitride-based coatings. Hung. J. Industy Chem. 2024, 52, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Tang, X. Research on Anti-Wear Properties of Nano-Lubricated High-Speed Rolling Bearings under Various Working Conditions. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2023, 30, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Milojević, S.; Savić, S.; Mitrović, S.; Marić, D.; Krstić, B.; Stojanović, B.; Popović, V. Solving the Problem of Friction and Wear in Auxiliary Devices of Internal Combustion Engines on the Example of Reciprocating Air Compressor for Vehicles. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2023, 30, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Filetin, T.; Grilec, K. Postupci Modificiranja i Prevlačenja Površina, 1st ed.; HDMT: Zagreb, Croatia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mphasha, N.P.; Rabothata, M.S. Advanced Surface Modification Techniques, Materials Science; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pastrafidou, M.; Binas, V.; Kartsonakis, I.A. Designing the Next Generation: A Physical Chemistry Approach to Surface Coating Materials. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, S.; Easwaramoorthi, M.; Meikandan, M. Different types of PVD coatings and their demands—A review. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2014, 9, 26417–26430. [Google Scholar]

- Antonov, M.; Hussainova, I.; Sergejev, F.; Kulu, P.; Gregor, A. Assessment of gradient and nanogradient PVD coatings behaviour under erosive, abrasive and impact wear conditions. Wear 2009, 267, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, T.; Hoche, H.; Polcik, P.; Kaestner, P.; Oechsner, M. Enhancement of the corrosion properties by alloying ternary TiAlN coatings with MgGd. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 509, 132210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mei, H.; Hua, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yi, G.; Deng, X. High-Temperature Oxidation and Wear Resistance of TiAlSiN/AlCrN Multilayer Coatings Prepared by Multi-Arc Ion Plating. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moganapriya, C.; Vigneshwaran, M.; Abbas, G.; Ragavendran, A.; Harissh Ragavendra, V.C.; Rajasekar, R. Technical performance of nano-layered CNC cutting tool inserts—An extensive review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.F.; Caicedo, J.; Aperador, W. Comparison of Structural and Electrochemical properties among TiCN, BCN, and CrAlN Coatings under Aggressive Environments. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 3586–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilek, O.; Knedlova, J.; Audyova, A. Microhardness and elastic modulus of thin coatings applied via PVD and CVD techniques. MM Sci. J. 2025, 2, 8322–8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow, P.C.; Ghani, J.A.; Rizal, M.; Jaafar, T.R.; Ghazali, M.; Che Haron, C.H. The study on the properties of TiCxN1−x coatings processed by cathodic arc physical vapour deposition. Tribol.-Mater. Surf. Interfaces 2019, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, H. Comparison of mechanical behavior of TiN, TiNC, CrN/TiNC, TiN/TiNC films on 9Cr18 steel by PVD. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 422, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiong, J.; Zhou, L.; Guo, Z.; Wen, H.; You, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, W. Properties of TiN–Al2O3–TiCN–TiN, TiAlN, and DLC-coated Ti(C,N)-based cermets and their wear behaviors during dry cutting of 7075 aluminum alloys. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2021, 18, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, S.; Zhao, J.; Lin, F.; Li, A.; Liu, S. Optimization of Forged 42CrMo4 Steel Piston Pin Hole Profile Using Finite Element Method. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2023, 30, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Imdad, A.; Arniella, V.; Zafra, A.; Belzunce, J. Tensile behaviour of 42CrMo4 steel submitted to annealed, normalized, and quench and tempering heat treatments with in-situ hydrogen charging. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 50, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakare, A.S.; Butee, S.P.; Kamble, K.R. Improvement in Mechanical Properties of 42CrMo4 Steel Through Novel Thermomechanical Processing Treatment. Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal. 2020, 9, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubić, S.; Kladarić, I.; Samardžić, I.; Jakovljević, S. The Adhesiveness of the PVD Coatings on Heat Treated Structural Steels. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2021, 28, 410–415. [Google Scholar]

- Golubić, S. Primjena Triboloških Prevlaka na Dijelovima Vijčanih Pumpi. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Naval Architecture, Zagreb, Croatia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Golubić, S. Utjecaj Nanošenja PVD Prevlaka na Svojstva Konstrukcijskih Čelika za Poboljšavanje. Doctoral Dissertation, Mechanical Enhineering Faculty, Slavonski Brod, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM G99-17; Standard Test Method for Wear Testing with a Pin-on-Disk Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Wegst, C.W. Stahlschlüssel: Key to Steel, 17th ed.; Stahlschlüssel Wegst GmbH: Marbach, Germany, 1995; pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.