Abstract

A knowledge of the process–structure–property correlation and underlying deformation mechanisms of material under a coupled electro-thermal–mechanical field is crucial for developing novel electrically assisted forming techniques. In this work, numerical simulation and experimental analyses were carried out to study the non-uniform deformation behaviors and microstructure evolution of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panels in different characteristic deformation regions during electrically assisted press bending (EAPB). The quantitative relationships between electro-thermal–mechanical routes, microstructural features, and mechanical properties of EAPBed stiffened panels were initially established, and the underlying mechanisms of electrically induced phase transformation and morphological transformation were unveiled. Results show that the temperature of the panel first increases then deceases with forming time in most regions, but it increases monotonically and reaches its peak value of 720.1 °C in the web region close to the central transverse rib. The higher accumulated strain and precipitation of the acicular O phase at mild temperature leads to strengthening of the longitudinal ribs at near blank holder regions, resulting in an ideal microstructure of 3~4% blocky α2 phase + a dual-scale O structure in a B2 matrix with a maximal hardness of 389.4 ± 7.2 HV0.3. While the dissolution of the α2 phase and the spheroidization and coarsening of the O phase bring about softening (up to 9.29%) of the lateral ribs and web near the center region, the differentiated evolution of microstructure and the mechanical property in EAPB results in better deformation coordination and resistance to wrinkling and thickness variation in the rib–web structure. The present work will provide valuable references for achieving shape-performance coordinated manufacturing of Ti2AlNb-based stiffened panels.

1. Introduction

A Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel is a key heat-resistant and load-bearing component in aerospace launch vehicle equipment. However, the undesirable room temperature formability of the Ti2AlNb alloy and the complex rib–web structure make the high-performance lightweight manufacturing of this panel challenging. Therefore, novel forming processes are urgently demanded to break through the conventional forming limit.

The electrically assisted press bending (EAPB), which integrates an electric pulse generator, segmented conductive fixtures, and insulating die systems into conventional press bending process, is a promising process for precision forming of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panels, due to the extensively proved formability enhancement and comprehensive performance amelioration of material under a coupled electro-thermo-mechanical field.

However, the EAPB process is a non-uniform elastoplastic deformation process of a hard-to-deform structure under a spatio-temporally varying electro-thermo-mechanical field. The microstructure evolution and structural responses of the Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel are highly sensitive to the thermo-mechanical route and the corresponding processing window is quite narrow. Therefore, it is profoundly challenging to attain accurate control of both the shape and performance of the Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel during EAPB. The present gap lies on that the process–microstructure–property correlation and underlying deformation and microstructure evolution mechanisms of this stiffened panel under spatio-temporally non-uniform coupled field.

The phase composition and morphology of Ti2AlNb-based alloys exhibit significant variation under different thermo-mechanical routes [1]. As the most important strengthening phase, the O phase was initially discovered by Banerjee [2] during experimental studies on the compositional and microstructural modification of Ti3Al alloys for the sake of strengthening and toughening. The pioneering research provided fundamental insights into the formation mechanisms, transformation routes and mechanisms, and activable slip systems of the O phase. Du et al. [3] mentioned that the O phase had a wide range of precipitation which could form distinct morphologies including spherical (or blocky), acicular, lamellar, and rod-like ones under different heat treatment schemes. Moreover, the formation temperature range for the band-like or needle-like O phase was determined as 550~700 °C, with the precipitated O phase with an average size of ~10 μm being a mildly deformed variant of the α2-phase. Kazantseva et al. [4] identified that the (110), (001), and (221) crystallographic planes served as twinning planes for the O phase. The BCC structured B2/β phase existed as a soft residual phase which could coordinate the deformation of multiphase alloys. The primary slip systems of the B2/β phase include {110}<111> and {112}<111>. Erinosho et al. [5] discovered that B2 phase also undergoes {112}<111> twinning deformation during warm deformation. Wei et al. [6] found the formation of equiaxed O bands was accompanied by the continuous formation of [00] 65° and [00] 55° annealing twins. Zhang et al. [7] discovered that the fracture toughness of Ti−22Al−26Nb alloy differed significantly with its microstructure. The maximum fracture toughness of 78 MPa·m1/2 was achieved at 1020 °C with 60% height reduction, which was 41.7% higher than the original one.

Moreover, deformation textures have also been observed in the B2/β phase during the rolling process, which alters the alloy’s formability notably. Dey et al. [8] reported similar findings, noting that a more pronounced B2 texture emerged after dynamic recrystallization during the rolling deformation of Ti-22Al-25Nb at 900~1100 °C. Li et al. [9] discovered that the B2 + O two-phase region deformation promoted the coarsening and spheroidization of the O phase while investigating the influence of hot deformation parameters on microstructure evolution of Ti2AlNb-based alloys with initial lamellar structure. The critical deformation strain for O phase spheroidization ranges between 0.3 and 0.5, with the spheroidization rate increasing approximately linearly as deformation strain rises. Additionally, the O phase gradually coarsens with increasing temperature and prolonged holding time.

In summary, extensive research has been conducted by domestic and international scholars on the deformation mechanisms of Ti2AlNb-based alloys at elevated temperatures. The formation mechanisms of the constituent phases mentioned above, along with their coordination behavior during hot deformation, provide a solid theoretical foundation for this study.

In the field of integrated shape–microstructure–performance control during multi-field coupled plastic forming of Ti2AlNb-based alloy components, Wu et al. [10] studied the microstructure evolution of Ti-22Al-24.5Nb alloy sheets during high-temperature gas bulging. They found that the biaxial tensile stress state during bulging promotes coordinated deformation of O, α2, and B2 phases. The formation of the B2(111)<0–11> texture and precipitation of α2 and O phases effectively inhibits grain growth, significantly enhancing the superplastic forming performance. Jeong et al. [11] found that the simultaneously formed γ-like intermetallic matrix phase and γ′-like (α2-based) intermetallic precipitates led to a remarkably high tensile strength of 0.5~1.7 GPa in a functionally graded structure manufactured by hybrid laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) and directed energy deposition (DED) with the aid of CNC milling. Xue et al. [12] discovered that the lath O phase gradually spheroidized during the O + B2 forging of Ti-22Al-25Nb alloy, which led to notable softening. The underlying mechanism was determined as shearing fragmentation. With deformation temperature increasing, the primary O lamellae transformed into B2 phase. At lower strain rates, the lamellar O phase tended to undergo bending fracture with more pronounced interfacial tearing failure. After thermo-mechanical processing in the three-phase region, rim-O structure formed through peritectic reaction between α2 and B2 phases, which improved the deformability of equiaxed particles and overall formability of the material. These studies demonstrate that through optimized matching of local deformation parameters, the viz. strain rate, temperature, size distribution, and morphology of the constituent phases can be actively controlled, thereby potentially achieving optimal microstructures that simultaneously enhance both service performance and press bending formability limits. However, research on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panels after electrically assisted press bending formation remains lacking.

Therefore, this study first conducted finite element (FE) simulation of the electrically assisted press bending of Ti2AlNb-based alloy integrally stiffened panels with the aid of our previously established FE model [13]. FE simulations were performed using ABAQUS/Standard (Version 2022, Dassault Systèmes, Providence, RI, USA) with an academic license. Then, the electrically assisted press bending (EAPB) experiments were conducted and the equivalent strain and thermal history in characteristic regions were investigated. Correspondingly, the mechanical property tests were performed, and microstructure evolution was analyzed. Finally, the forming mechanisms in characteristic regions of the formed panels were systematically analyzed, providing critical references for achieving synergistic formability–property manufacturing of stiffened panels.

2. Materials and Experimental Procedures

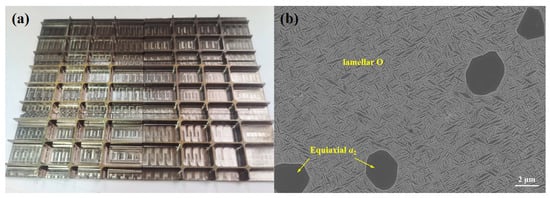

The Ti2AlNb-based alloy blank used in this paper was a 20 mm hot rolled plate. The thermo-mechanical processing of the Ti2AlNb-based alloy thick plate consisted of holding at 960 °C for 2 h after multi-pass hot rolling in the B2 + O two-phase zone. Figure 1 shows the Ti2AlNb-based alloy blank and its scanning electron microscope (SEM) diagram. In the SEM image, the shallow contrast is B2 phase, and the deep contrast is O phase and α2 phase. The figure shows that the initial structure is mainly composed of matrix B2 phase, a large number of secondary lamellar O phase, and massive α2 phase. The average length of the secondary O phase is about 631.6 ± 25.8 nm, the average width of the middle of the strip is about 125.0 ± 8.6 nm, and the average axial ratio is 4.5 ± 0.3, accounting for 51.5 ± 3.6% of the whole content. The bulk α2 phase has a volume fraction of 8.58 ± 1.1% and a size of 3.51 ± 0.13 μm.

Figure 1.

The original Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel: (a) the as-milled flat blank; (b) SEM image of the as-received microstructure.

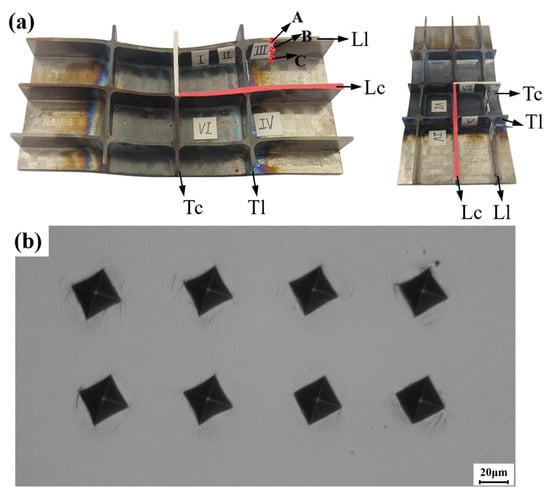

The EAPB experiment of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel was conducted on a EAPB process prototyping platform developed by the authors’ research group in the School of Materials Science and Engineering, Hefei University of Technology. The platform was composed by a RZU200HF universal press (provided by Hefei Metalforming Equipment Co., Ltd., Hefei, China), a 10 kA/160 kV one-way power generation (provide by Ningbo Yueyang Power Equipment Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China), and customized tooling fixtures and die systems. The detailed procedures are as follows: First, the stiffened panel is clamped by the blank holder, and the pulse current generator is connected through the copper electrode. Then, the high frequency pulse current was loaded, and the full-field temperature of the panel was recorded by Fluke TiX640 infrared imager (Fortive Corporation, Everett, Unites States). When the surface of the blank is heated to a certain temperature, the punch begins to move downward, while keeping the pulse current continuously loaded until the punch faces downward to the target position. After bending, turn off the pulse current generator and keep the punch fixed for 60 s. During the whole bending process, a rectangular wave pulsed current with a current frequency of 500 Hz, a pulse width of 100 μs, a nominal current density of 10 A/mm2, and a downward speed of the punch of 0.2 mm/s were utilized. Figure 2 shows the forming process and the panel after forming. It can be seen that there are no obvious cracking and buckling defects in the EAPBed panel.

Figure 2.

The through-process simulation scheme and experimental setup of electrically assisted press bending process of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel.

The characteristic regions (labeled as region I~VII) after bending were sampled to characterize their mechanical properties and microstructure after EAPB. Figure 3 shows the sampling positions of I~VII. The X direction and Y direction are marked by red and white, respectively. As is seen from Figure 3, the longitudinal-center and side ribs of the panel are named the longitudinal-center (Lc) and longitudinal-lateral (Ll) rib, respectively. The lateral center and side ribs of the siding are named the transversal-center (Tc) and transversal-lateral (Tl) rib, respectively. Sample I~III are taken from the Ll ribs (5 × 1 × 10 mm along XYZ direction). Sample IV and VI are taken from the web (the dimensions are 5 × 5 × 2 mm along the XYZ direction), and sample V and VII are taken from the Tl and Tc ribs (the dimensions are 1 × 5 × 10 mm along the XYZ direction), respectively. Moreover, the top, middle, and web of the rib samples are represented by A, B, and C, respectively.

Figure 3.

Sampling positions of I~VII characteristic specimens (a) and typical Vickers indentation (b) of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel for microstructure observation. A, B, C denote the top, mid and bottom positions of the rib.

After EAPB, the metallographic characterization test and scanning electron microscope (SEM) test for each characteristic region were carried out. The sample preparation procedure mainly comprised coarse grinding with 80~2000# polishing sandpaper, refined polishing with 0.5 μm silica sol, and then Argon ion beam polishing with the aid of Leica RES102 cross section polisher (Leica Geosystems AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland). JM-5000 inverted metallographic microscope (Jiangnan Novel Optics Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used to observe the metallographic structure. A Zeiss Gemini 300 field emission SEM (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to examine the surface morphology and microstructure of the samples; the acceleration voltage was set at 20 kV and the probe was set in-lens. The sample for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) investigation was prepared by a standard twin-jet electro-polishing technique. Sample slices with a thickness 0.3 mm were cut and mechanically polished to 50 μm in thickness. Disks with a diameter of 3 mm were punched-off from the slice and then thinned by electro-polishing at 25 V and −40 °C with a solution of 10% perchloric acid + 90% methanol. TEM investigations were implemented on a JEOLJEM-F200 equipment (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and the accelerating voltage was set as 200 kV.

The Vickers microhardness test equipment is the MH-3 microhardness tester (Shanghai Yanrun Optical Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Before the test, the Vickers hardness samples were prepared according to the operating steps of metallographic samples. The load is set to 300 g and the pressure holding time is 15 s. The diagonal length of the diamond indentation on the surface of the sample is manually measured to calculate the hardness value at the measurement point. The interval between each measuring point is 1 mm. After measuring 8 points in each region, the average hardness value is calculated.

3. Results

3.1. Strain Distribution

The equivalent strain distribution of sample I~VII are listed in Table 1. The results are derived from the previously published finite element simulation research [13]. It can be seen from the table that the equivalent strain of region I and II is in the range of 0.024~0.108, while the equivalent strain of region III is much higher than that of region I and II. And it increases gradually from A to C, reaching 0.223 at the web. The equivalent strain in region IV is 0.086, and there is no equivalent strain in region VI. The TD directional ribs are almost not involved in deformation, and only have 0.004 strain at the web position of zone V.

Table 1.

Equivalent strain distribution of different positions of the EAPBed Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel.

3.2. Temperature History

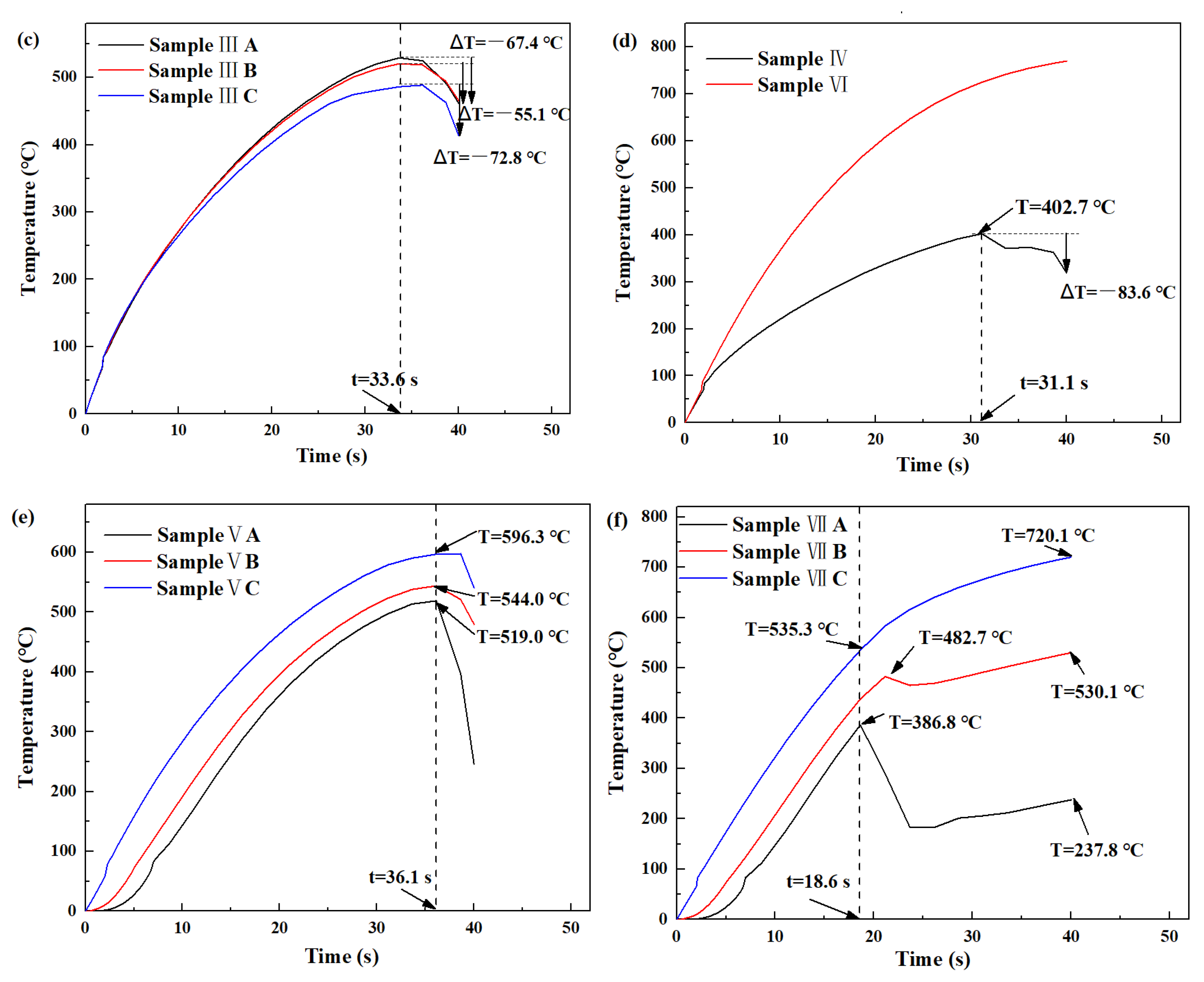

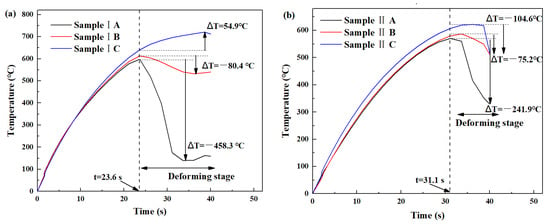

Figure 4 shows the temperature history of the I~VII regions of the Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel during the EAPB process. It can be seen that the temperature at these regions first linearly increases and then decreases, and the rib temperature begins to drop while the top of the rib begins to contact the punch. TA < TB < TC was maintained in region I and II, while TA > TB > TC was maintained in region III; the temperatures at A, B, and C were similar before the deformation began. In region I, at the beginning of deformation (t = 23.6 s), the temperature at the top of the rib is 597.7 °C, the temperature at middle of is 612.9 °C, and the temperature at web is 640.7 °C.

Figure 4.

Temperature history at different positions of the EAPBed Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel: (a) I; (b) II; (c) III; (d) IV and VI; (e) V; and (f) VII.

With the progress of deformation, the temperature at the top of the rib decreases rapidly, the middle decreases slowly, while the web increases slowly. The overall temperature trend of region II is similar to region I; the deformation started at 31.1 s, and the temperature at the beginning of deformation is 607.3 °C at A, 579.6 °C at B, and 570.6 °C at C. The temperature drop in region II is lower than that in region I because the deformation time is short.

Region III begins to participate in plastic deformation at 33.6 s, and the temperature at the beginning of deformation is 529.7 °C at A, 520.9 °C at B, and 486.7 °C at C, and the temperature drops less than 72.8 °C during the deformation process.

Before the deformation, the highest temperature of region IV is 402.7 °C, and the temperature drops by 83.6 °C during the whole deformation process. The temperature of region VI continued to rise during the whole process, up to 769.6 °C.

Region V and VII maintained TA < TB < TC throughout the whole process, and the temperature of region V continued to rise before 36.1 s (596.3 °C at A, 544.0 °C at B, and 519.0 °C at C), then dropped rapidly after 36.1 s, and the cooling rate of A was the fastest while C was the lowest. Before 18.6 s, the temperature of VII A continued to rise to 386.8 °C, then dropped rapidly and slowly rose to 237.8 °C; the temperature of VII B quickly rose to 482.7 °C and then slowly rose to 530.1 °C; and the temperature of VII C kept rising until the maximum temperature of 720.1 °C.

3.3. Mechanical Behaviors

Table 2 shows the microhardness (HV0.3) of the initial material and different locations in regions I to VII. It can be seen from the table that after deformation, the Vickers hardness values of region I~III have the same distribution law along the height direction of the rib, with the highest at the web, and the lowest at the top of the rib. The hardness values of region I and II decreased after deformation, while region III increased significantly. The hardness value of region IV is slightly higher than that of the initial state while region V~VII is slightly lower than the initial state. Combined with the equivalent strain distribution in Table 1, it can be found that the hardness changes significantly in the region with larger equivalent strain. In the region V~VII, there is almost no deformation distribution, and the hardness value fluctuates less.

Table 2.

Microhardness (HV0.3) of initial state and different positions of the EAPBed Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel.

3.4. Microstructure Evolution

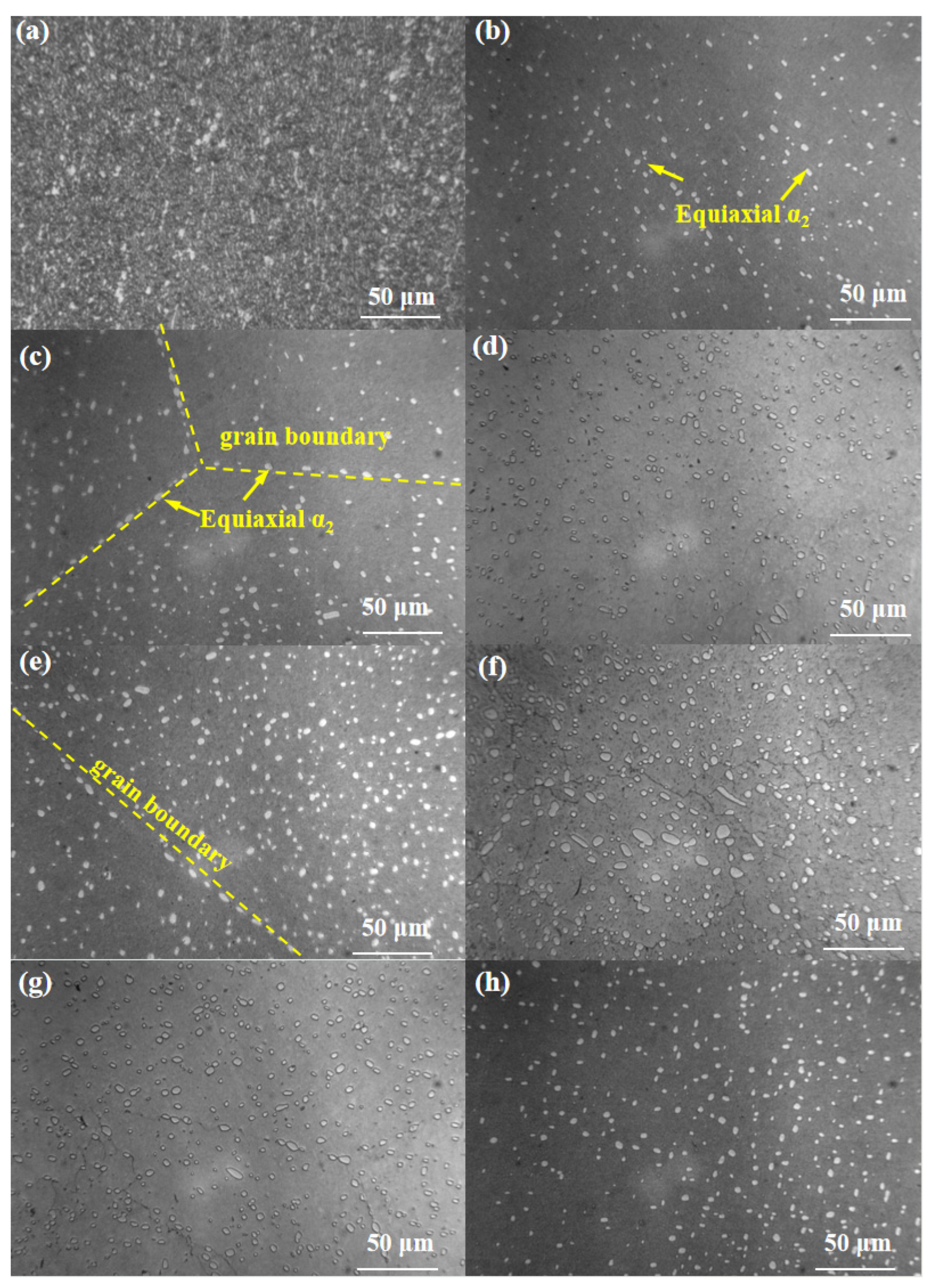

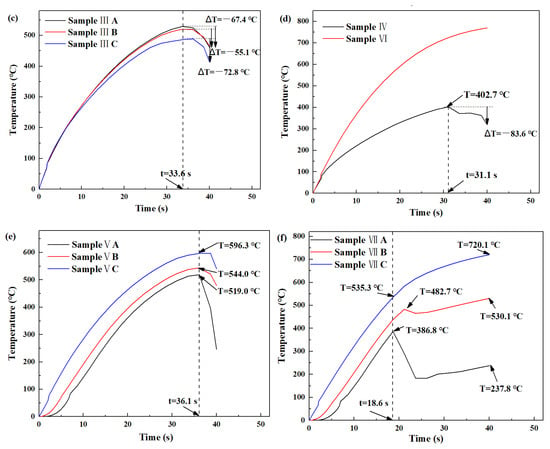

Figure 5 shows the metallographs of region I~VII. In the metallograph, the equiaxial structure with high contrast is the bulk α2 phase, while the structures with low contrast are the B2 phase and the O phase. It is not easy to distinguish the B2 phase and the O phase in the metallographs due to the magnification. As can be seen from Figure 5, equiaxed block α2 phase in region I~VII is distributed uniformly inside the B2 phase matrix and regularly at the grain boundaries. The volume fractions of α2 phase in region I, II, and III are 3.7 ± 0.5%, 4.0 ± 0.4%, and 3.9 ± 0.5%, and the size is 3.21 ± 0.11 μm, 3.37 ± 0.21 μm, and 3.35 ± 0.17 μm, respectively. Compared with the initial structure, the volume fraction of the α2 phase in region I~III decreased significantly, and the size decreased by 3.9~8.5%. The volume fractions of the α2 phase in region IV~VII are 8.61 ± 1.1%, 8.47 ± 0.5%, 8.63 ± 0.4%, and 8.52 ± 0.5%, respectively. The dimensions are 3.57 ± 0.12 μm, 3.49 ± 0.08 μm, 3.62 ± 0.11 μm, and 3.50 ± 0.13 μm, respectively. Compared with the initial structure, the volume fraction and size of the α2 phase in region IV~VII have no significant change.

Figure 5.

Metallographs of I~VII positions of EAPBed Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel: (a) initial; (b) I; (c) II; (d) III; (e) IV; (f) V; (g) VI; and (h) VII.

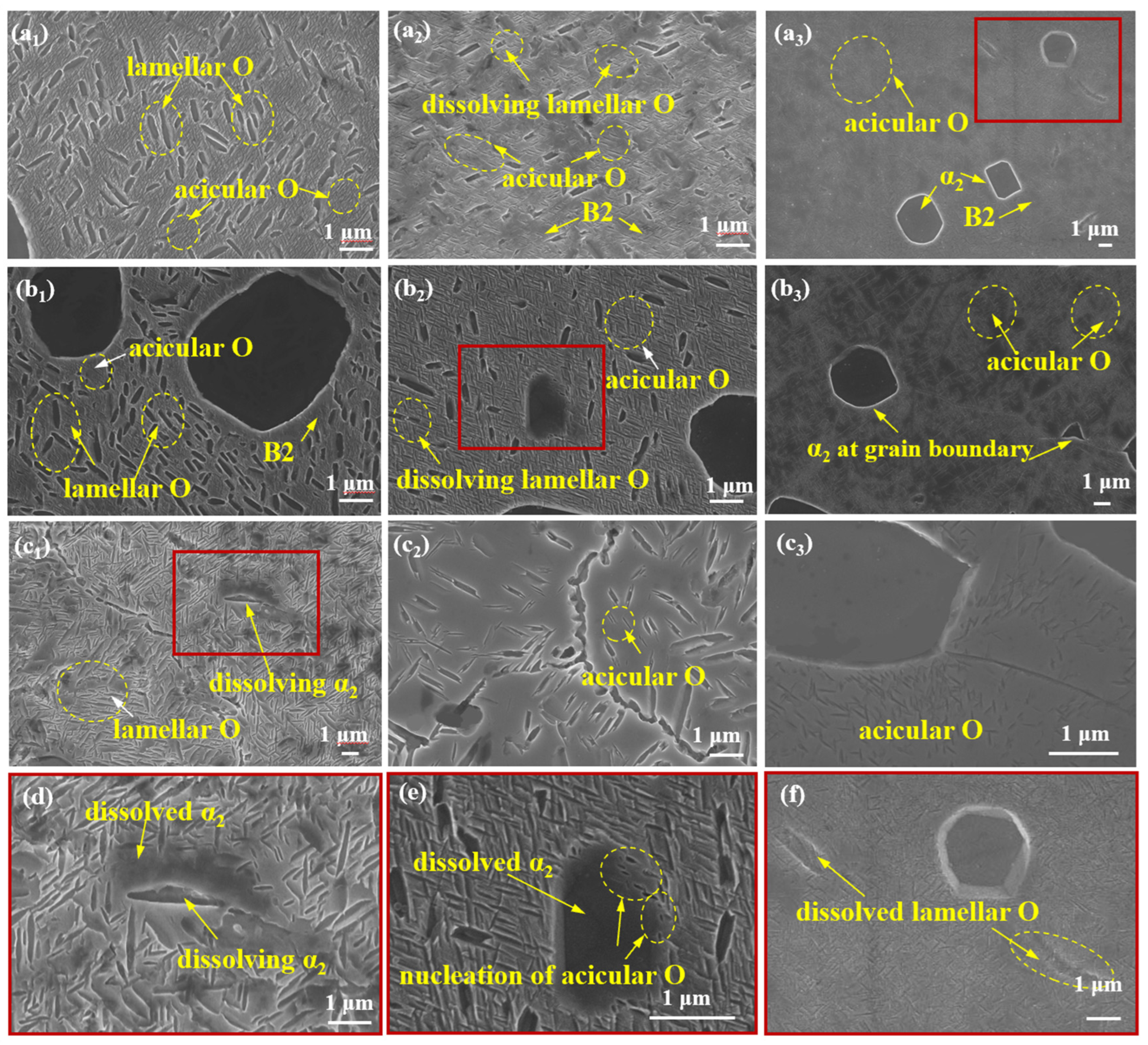

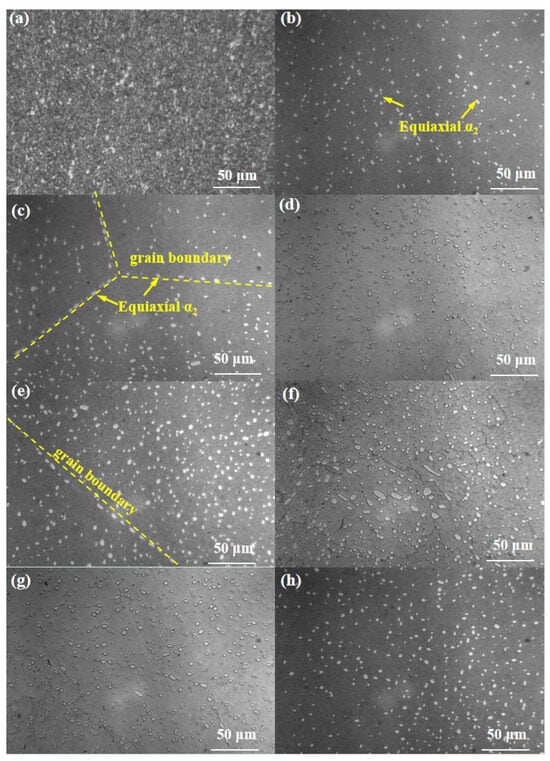

Figure 6 shows the SEM images of different positions in region I~III. As described by He et al. [14], the α2 phase has the lowest contrast and the B2 phase has the highest contrast in the SEM images. It can be seen that for position I to III, region A consists of the matrix B2 phase, many lath O phase, bulk α2 phase, and acicular O phase. The content of the lath O phase at region B was significantly reduced compared with that at region A, and the acicular O phase was significantly increased. The web is composed of the matrix B2 phase, bulk α2 phase, and a large number of acicular O phase, and the lath O phase completely disappears. Except for the position IIIA, the curvature of both ends of the O phase of the rest of the deformed region is significantly reduced, and the length of the O phase is shorter and the content is reduced along the height direction. It is worth noting that in the area marked by the red frame at the region IC, traces of the lath O dissolved into the matrix B2 phase can be found, and many secondary acicular O phase is observed in the residue B2 matrix. In the red box marked area at the region IIB, obvious traces of bulk α2 phase decomposition can be found, and secondary acicular O phase nucleation can be seen in the adjacent regions. In addition, in the region marked by the red box of region IIIA, the obvious traces of massive α2 phase decomposition can also be observed, and irregular residual α2 phase can be observed in the center of the traces.

Figure 6.

SEM images of region I~III of EAPBed Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel: (a1) IA; (a2) IB; (a3) IC; (b1) IIA; (b2) IIB; (b3) IIC; (c1) IIIA; (c2) IIIB; (c3) IIIC; (d) enlarged image of red frame in IIIA; (e) enlarged image of red frame in IIB; and (f) enlarged image of red frame in IC.

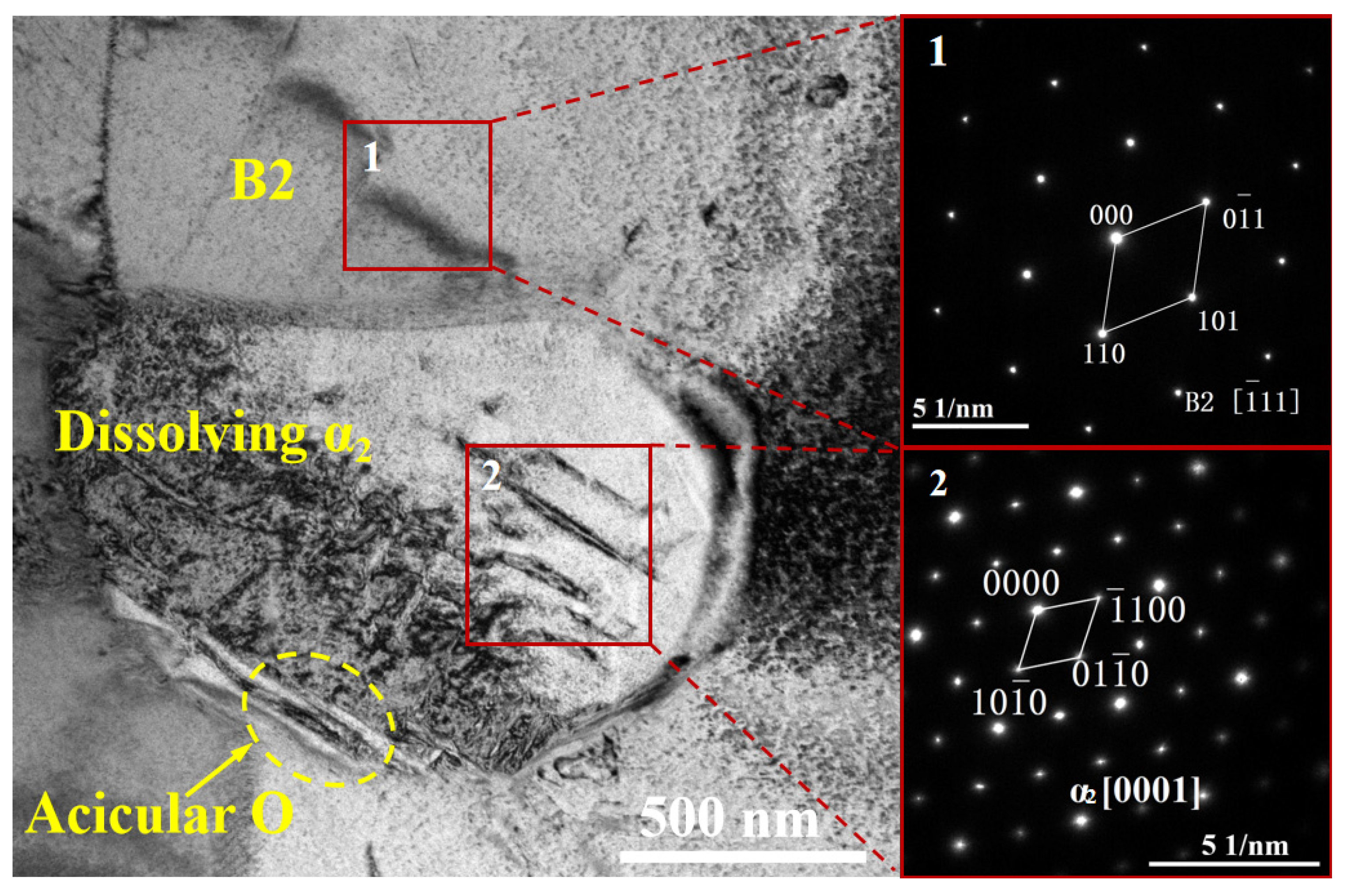

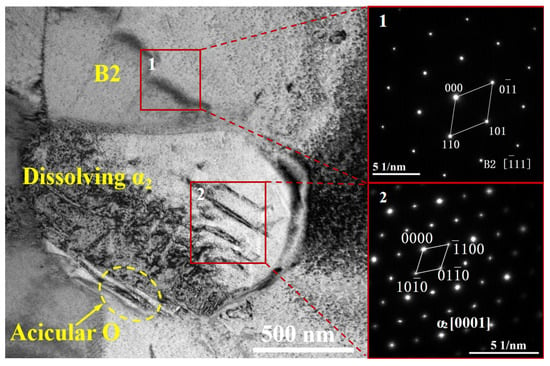

To verify the α2 phase decomposition observed in the SEM images, Figure 7 shows the transmitted bright field of region IIB, with the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns presented for area 1 and area 2, respectively. Area 1 corresponds to the matrix B2 phase, area 2 is the decomposing α2 phase, and the nucleation of the acicular O phase can be observed as well in the lower left corner of the α2 phase.

Figure 7.

The TEM bright field graph of region IIB in Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel with diffraction patterns of B2 and α2 phase in the regions marked as 1 and 2.

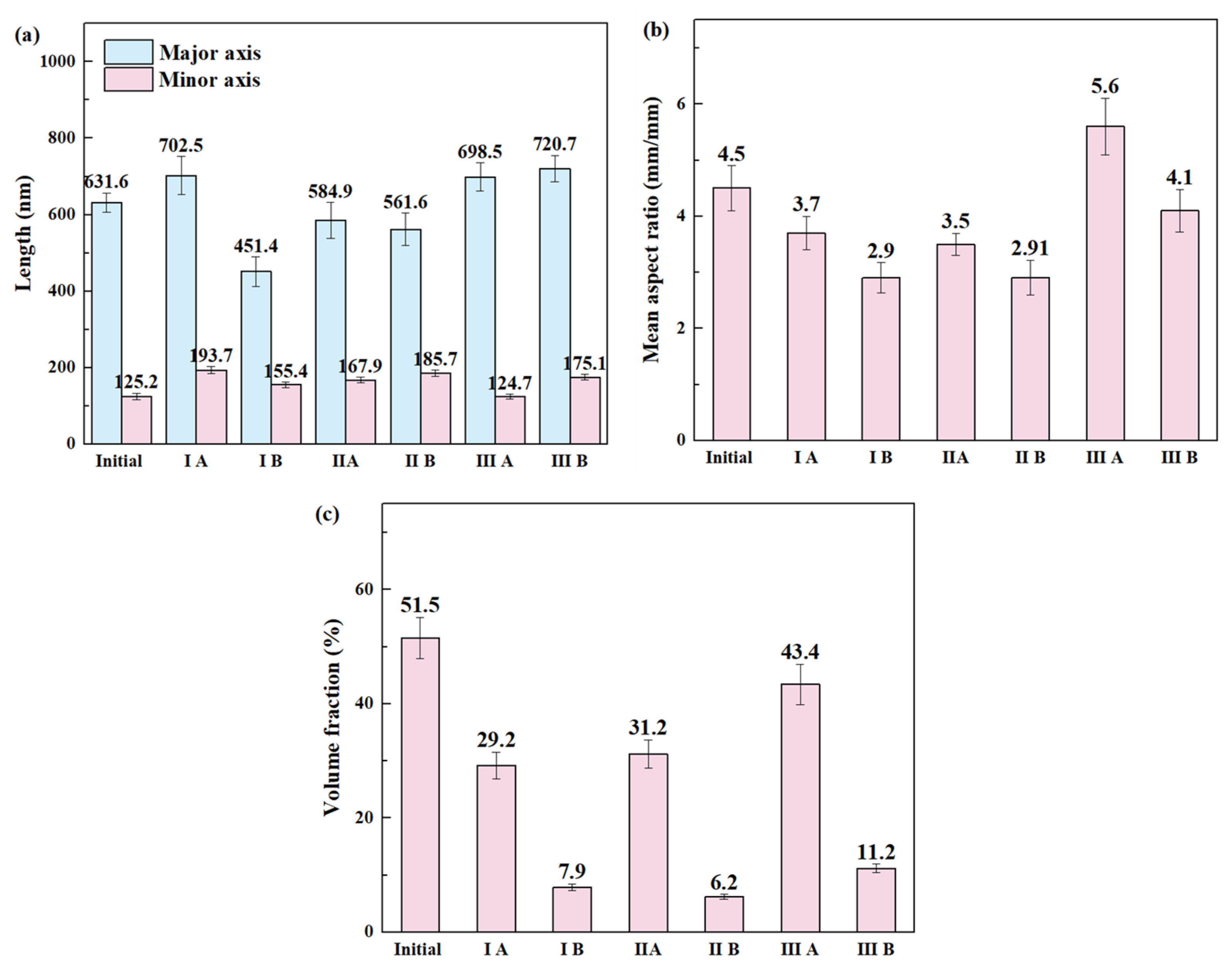

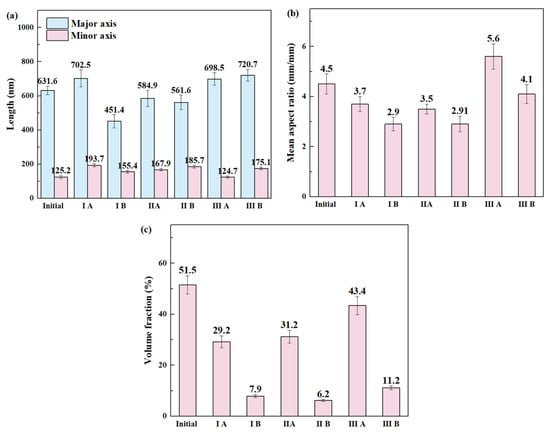

Figure 8 shows the quantitative statistics of the size, aspect, and volume fraction distribution of the lamellar O phase of region I~III. The length-major axis and length-minor axis refers to the long axis and short axis dimensions of the minimal envelope quadrilateral bounding the O lamella, which correspond to the lamellar length and thickness, respectively. As can be seen from Figure 8, compared with the initial state, the length of the lamellar O phase at region IA increased by 11.2%, while at other areas in region I and II it became shorter to varying degrees.

Figure 8.

The size, aspect ratio, and volume fraction distribution of lamellar O phase of sample I~III: (a) major axis and minor axis length; (b) mean aspect ratio; and (c) volume fraction.

Moreover, the length of the lamellar O phase at area B was significantly shorter than that at area A. The size of the long axis of the O phase in region IIIA and B increased by 10.6% and 14.1%, respectively. The size of the short axis in A slightly decreased, and the size of the short axis in B increased significantly. Compared with the initial state, the average axial ratio and the content of lamellar O phase in regions I and II are significantly decreased after deformation, and the average axial ratio and volume fraction at B are lower than that at A. The aspect ratio in region IIIA was abnormally elevated, and was significantly higher than that in region IIIB. At the same time, the content of the lamellar phase in region IIIA decreased slightly compared with the initial structure, while that in region IIIB decreased significantly.

4. Discussion

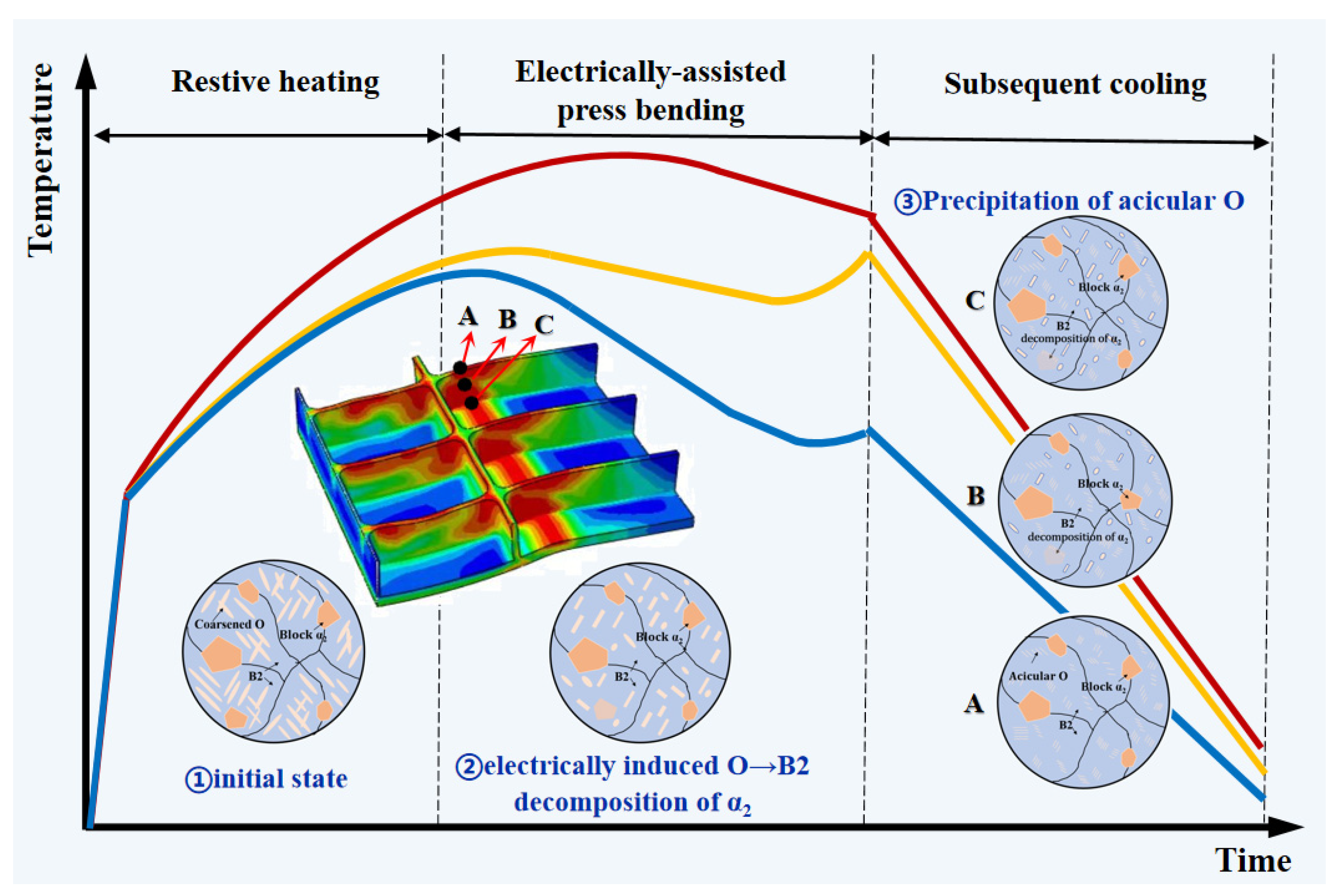

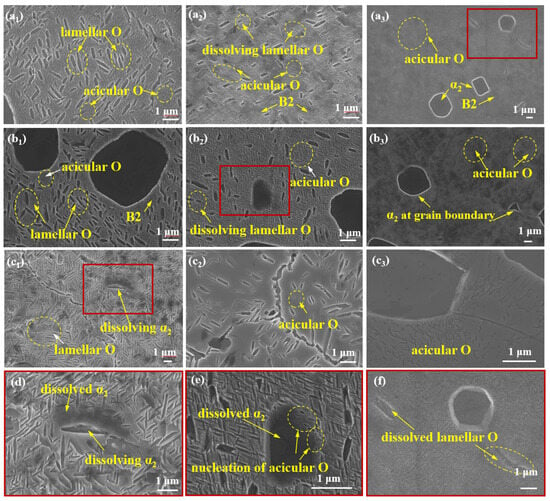

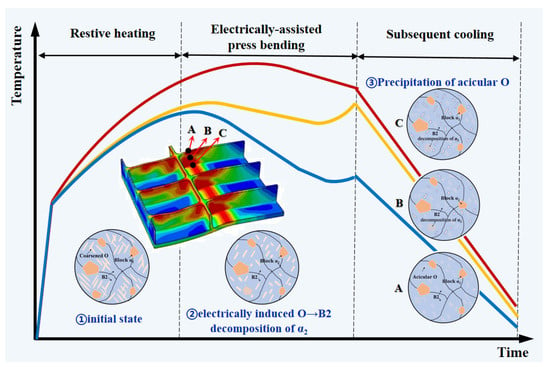

Due to almost no strain distribution for position V~VII, the whole EAPB process is equivalent to a short-term aging process. The content and size of the α2 phase do not change significantly because the transition point of the α2 phase is much higher than the aging temperature and the structure is stable so can exist in the heat preservation process for a long time. The lamellar O phase grows along the length direction during the electrical treatment, and the phase content and morphology change little which is consistent with the microstructure obtained by Wang et al. [15] and Li et al. [16]. In their research, the microstructure for the B2 + O two-phase Ti2AlNb-based alloy with an initial microstructure of a fully annealed state after both low density current (6.70 A/mm2) electric heating and furnace temperature heating at 780 °C are similar. After electric treatment, the phase content and O phase morphology of region V~VII did not change much, and the length of the lamellar O phase increased, which was due to the fact that there was no strain in the deformation process and the initial structure of the panel was annealed, high-energy defects were not introduced in these three regions, and the driving force and free energy of the phase transformation were lacking. At low current density, the floating electrons do not significantly change the composition, size, and morphology of the O phase. According to the research of Gogia et al. [17], the increase in the lamellar O phase size will lead to a decrease in the strength, which is the main reason for the slight hardness decrease in region V~VII after the deformation. For region IV, although defects (equivalent strain 0.086) are introduced in the deformation process, no significant phase transition occurs due to the low temperature (maximum temperature 402.7 °C) in the deformation process, which is much lower than the O→B2 + O phase transition temperature. The change in the long axis and short axis of the O phase in this region is mainly related to tension. The work hardening caused by defects introduced by deformation is the main reason that the hardness value of this region is higher than that of the initial material. Figure 9 summarizes the microstructure evolution mechanism of region I~III in the EAPB process. Results show that the decomposition of the α2 phase in the middle area of the rib of region II and the web of region III is primarily driven by the cumulative deformation energy and local Joule heating at the B2-α2 phase boundaries during the electrically assisted deformation process [18]. In the EAPB forming process, local Joule heat, transient thermal expansion and resultant distortion energy accumulate significantly at the α2-B2 phase boundary. Then the Nb element in the B2 matrix tends to diffuse through the B2-α2 phase boundary in short range, which further leads to the formation of interphase Nb-poor regions and Nb-rich regions at the edge of the primary α2 phase. Hence, the O phase can be generated at the expense of α2 phase consumption by α2→α2 (poor Nb phase) + O (rich Nb phase) transformation in a lower temperature (O + B2) phase region. This phenomenon was also found in the process of quenching and aging of the Ti2AlNb-based alloy at 900 °C +700 °C by Khadzhieva et al. [19]. In this study, the α2 phase could not be completely decomposed into the α2 + O lamellae mixed structure because the short forming process would lead to insufficient element diffusion, although the deformation energy accumulated in the primary α2 phase during EAPB in region I~III.

Figure 9.

Microstructure evolution mechanisms of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel during EAPB process. A, B, C denote the top, mid and bottom positions of the rib.

According to the research of Wu et al. [20,21,22], the fine lamellar O phase of Ti-24Al-14Nb-3V-0.5Mo alloy can be directly transformed from the α2 phase, distributed around the primary α2 phase in the early aging period, and grows inside the α2 phase during the aging process. The nucleation and growth of the O phase on α2 phase matrix is controlled by the atomic diffusion process. Therefore, the decrease in primary α2 phase content in region I~III after EAPB of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel can be explained as follows: In the forming process, the distortion energy accumulates significantly at the phase boundary between α2 and B2 phase. Under the action of the Joule heating effect, the Nb element in the B2 matrix diffused through the α2/B2 phase boundary in a short range, which further leads to the formation of interphase Nb-poor and Nb-rich regions at the edge of the primary α2 phase. The secondary fine acicular O phase nucleates around the α2 phase and grows inside the α2 phase. The α2 phase is a brittle phase with poor plasticity and a small amount of independent slip systems [23]. The decrease in α2 phase content will lead to the increase in plasticity of region I~III.

The content of the secondary/acicular O phase in region I~III increases, which brings the precipitation strengthening and further leads to the strengthening of the material at both room temperature and high temperature. According to the research of Wang et al. [15,24,25], the secondary O phase can be obtained when aging at 760~840 °C, and the content of the secondary acicular O phase obtained by aging at 760 °C is the highest. Xue et al. [26] pointed out that the thickness of the lamellar O phase would coarsen with the increase in aging temperature or time (the thickness of the lamellar O phase after solid solution at 980 °C + aging at 760 °C for 1 h was 0.16 μm), and this transition process was controlled by diffusion. Furthermore, the generation secondary acicular O phase is driven by electrically induced multisite nucleation, enhanced diffusivity, and subsequent precipitation transformation within the matrix B2 phase. The lowered supersaturation of the Nb element and the release of distortion energy in the matrix B2 phase are the driving force of this process. Moreover, the growth of the acicular O phase stops after contact with other phases, which is consistent with the research results of Meng et al. [27]. It believes that under the fast cooling rate, the secondary phase induced nucleation nucleates from the grain boundary/phase boundary, grows, and stops after contact with the new phase growing in the relative direction. The secondary acicular O phase is hard and brittle [28,29], which can effectively improve the strength of the material, and that is the reason why the hardness value at the web of region I~III is higher than that at the ribs.

In region I~III, the lengths of the lath O phase were shortened to varying degrees, while the minor axes became thicker, which is related to the spheroidization of the lath O phase. According to research by Li et al. [10], during the deformation of Ti2AlNb-based alloys in the two-phase region (930~970 °C), as the deformation temperature increases, the primary O lath transforms into the B2 matrix, thus the O phase content decreases and the spheroidization rate increases. The length of the primary lath O phase shortens, while its thickness increases. In region I~III, the temperature during the entire deformation process mainly ranges between 300 and 600 °C; rapid spheroidization cannot occur if only the effects of deformation and temperature are considered.

Under a pulsed electric current, the current exhibits a concentration effect at tips/defects (non-uniform Joule heating effect) [30]. Under compressive stress, a large number of dislocations and high-energy defects accumulate at the lath O/B2 phase boundaries in region I~III. These high-energy defects generate localized Joule heating under the influence of a pulsed current, forming “hot spots” at defect-rich sites. This promotes the O→B2 + O phase transformation at temperatures below the phase transition point, leading to the shortening of the lath O phase’s major axis, which is consistent with previous research findings [31,32]. The detailed reason is as follows. The “hot spots” can be formed in regions with high defect density during the EAPB process due to the local Joule heating effect, intense local lattice distortion, and microstress field due to the severe transient thermal expansion and defect interactions. The local “hot spots” and intense microstress/distortion are beneficial to lowering the energy barrier for phase transformation by creating a localized high-temperature condition and short-circuit pathways for diffusion. Simultaneously, under the localized high-temperature field induced by Joule heating, the current also facilitates the spheroidization of the O phase, resulting in the elongation of the minor axis. However, due to the short deformation time, elemental diffusion cannot fully proceed, leading to a limited degree of spheroidization of the lath O phase.

According to the study by Xing et al. [33] on the heat treatment process of Ti-22Al-25Nb alloy forgings, it can be obtained that increased solution temperature significantly reduces the content of the primary lath O phase and increases the content of the secondary acicular O phase precipitated during cooling. For region I~II, the temperature gradually increases from the top of the ribs to the web. The rib top exhibits the highest content of lath O phase, whereas the lath O phase completely disappears in the web area.

During deformation, as the top of the rib first contacts the punch, its cooling rate can reach 49.6 °C/s. This rapid temperature drop prevents the O phase laths from O→B2 + O phase transformation, resulting only in a reduction in curvature at the ends. In contrast, the cooling rate in the middle of the rib is significantly lower than at the top, allowing for a longer duration of the O→B2 + O phase transformation. Consequently, this region exhibits a greater degree of phase transformation, with shorter and fewer laths. As for the web area, the average temperature becomes the highest and cooling is not significant during the whole EAPB process. In this region, the O laths completely dissolute into the B2 matrix. As for region III, plastic deformation begins at 33.6s (10 s later than region I). Defects at the top of the rib just start to accumulate while the temperature drops rapidly, the lath O phase does not have enough time to undergo phase transformation, retaining the lamellar morphology of the initial structure. The elongation of the laths is attributed to short-term low-temperature aging under electropulsing, during which the lath O phase primarily grows in length but does not have sufficient time to thicken.

Therefore, the variation in hardness of the deformed longitudinal ribs after deformation is primarily attributed to the competition among multiple mechanisms: work hardening caused by deformation-induced defects such as dislocations, Hall–Petch strengthening from the precipitation of the secondary acicular O phase, softening effects due to the O→B2 + O phase transformation and spheroidization of the O phase, and dynamic recovery. For region I and region II, due to the higher temperature during deformation (within the range of 570.6~640.7 °C), the O→B2 + O phase transformation and dynamic recovery mechanisms predominated, resulting in a decrease in hardness. In region III, the plastic deformation began last, which experienced the highest deformation and the shortest aging time. The work hardening effect caused by deformation could not be completely eliminated by dynamic recovery, leading to an increase in hardness relative to the initial microstructure.

During service, stiffened panels must operate complex alternating loads for prolonged periods, which impose stringent requirements for high thermal strength and creep resistance. For the deformed Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel, the microstructure in the deformation zone of the longitudinal stiffeners consists of 3~4% blocky α2 phase + a dual-scale microstructure (fine acicular O phase + B2 matrix phase + lamellar O phase).

According to the findings of Xue and Wang et al. [12,34,35], the Ti2AlNb-based alloy with a dual-scale O phase microstructure (lamellar O phase + fine acicular O phase + B2 matrix phase) exhibits significantly higher yield strength and enhanced creep resistance compared to the alloy with a single-scale O phase distribution (lamellar O phase + B2 matrix phase). Analysis of the hardness distribution reveals that pulse current-assisted press bending enables coordinated plastic deformation of the stiffeners with only a minor reduction in strength/hardness. This process effectively overcomes buckling of the longitudinal stiffeners and excessive wall thickness variation, and the slight spheroidization of the lamellar O phase occurring enhances the toughness of the stiffeners. Furthermore, under the action of the pulse current, the abundant precipitation of fine acicular O phase during the high-temperature thermal cycling in the web region increases the strength and hardness. For the inherently thin-walled, low-stiffness web structure, this effectively enhances its structural strength and load-bearing capacity.

These results provide valuable insights for actively leveraging the non-uniform spatiotemporal characteristics of the electro-thermo-mechanical coupled field during electrically assisted forming. This approach enables coordinating the inhomogeneous deformation between the longitudinal/transverse stiffeners and the web, directional control of the content and morphological distribution of the microconstituents within the panel, and ultimately achieving coordinated manufacturing of both the geometry and properties of the stiffened panel.

5. Conclusions

The variation rules of microstructure and mechanical property of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel subjected to electrically assisted press bending (EAPB) and their correlations with electro-thermo-mechanical routes were investigated by multi-physics coupled simulation and experiments. Moreover, the corresponding mechanisms of electrically induced phase transformation and microstructure morphological transitions were revealed. The detailed conclusions are as follows.

- (1)

- After EAPB, the α2 phase content in the deformation zone of the longitudinal stiffeners of the Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened integral panel significantly decreased, primarily due to direct decomposition of the α2 phase. Secondary fine acicular O phase particles nucleated around the α2 phase and grew inward into it. Along the height direction of the stiffeners, the length and content of the lamellar O phase decreased progressively, completely disappearing upon reaching the web region. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the electrically induced O→B2 + O phase transformation.

- (2)

- In the deformation zone of the longitudinal stiffeners, the post-deformation hardness variation is primarily governed by competing mechanisms: work hardening induced by deformation introduced defects such as dislocations, Hall–Petch strengthening from the precipitation of the secondary acicular O phase, softening effects arising from the O→B2 + O phase transformation and O phase spheroidization, and dynamic recovery. Within the inner compressive zone of the longitudinal stiffeners, the O→B2 + O phase transformation and dynamic recovery mechanisms predominate, resulting in a decrease in hardness compared to the initial microstructure. Conversely, in the outer tensile zone, which experienced the highest deformation magnitude and shortest aging time, the work hardening effect caused by deformation could not be eliminated in time by dynamic recovery, leading to an increase in hardness relative to the initial microstructure.

- (3)

- Pulse current-assisted press bending enables coordinated plastic deformation of the stiffeners with only a minor sacrifice in strength/hardness, effectively overcoming buckling of longitudinal stiffeners and excessive wall thickness variation. Concurrently, the slight spheroidization of the lamellar O phase enhances the toughness of the stiffeners. Furthermore, under the pulse current, the abundant precipitation of fine acicular O phase during high-temperature thermal cycling in the web region increases the strength and hardness of the web material. This effectively enhances the structural strength and load-bearing capacity of the inherently thin-walled, low-stiffness web.

These results provide valuable insights into the non-uniform spatio-temporal characteristics of the electro-thermo-mechanical coupled field during electrically assisted forming to coordinate the inhomogeneous deformation between longitudinal/transverse stiffeners and the web, and to further directionally control the content and morphological distribution of the constituent phases and ultimately achieve coordinated manufacturing of both forming precision and mechanical properties of the Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-L.Z. and S.-L.Y.; methodology, X.-L.Z.; software, Z.-L.L.; validation, X.-L.Z., Y.-H.G. and M.M.; formal analysis, X.-L.Z.; investigation, X.-L.Z., Z.-L.L. and Y.-H.G.; resources, S.-L.Y.; data curation, S.-L.Y. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-L.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.-L.Y. and M.M.; visualization, X.-L.Z.; supervision, S.-L.Y. and M.M.; project administration, S.-L.Y.; funding acquisition, S.-L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52375330, U24B2054, U23B20100, 52475342), Research Project of State Key Laboratory of Mechanical System and Vibration (Grant No. MSV202520), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. PA2025GDGP0025).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the technical assistance from CAS-Tech (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EAPB | Electrically assisted press bending |

| FE | Finite element |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| Lc | Longitudinal-center |

| Ll | Longitudinal-lateral |

| Tc | Transversal-center |

| Tl | Transversal-lateral |

References

- Zhang, H.Y.; Yan, N.; Liang, H.Y.; Liu, Y.C. Phase transformation and microstructure control of Ti2AlNb-based alloys: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 80, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Gogia, A.K.; Nandi, T.K.; Joshi, V.A. A new ordered orthorhombic phase in a Ti3Al Nb alloy. Acta Metall. 1988, 36, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.H.; Ma, S.B.; Han, G.Q.; Wei, X.; Han, J.C.; Zhang, K.F. The parameter optimization and mechanical property of the honeycomb structure for Ti2AlNb based alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 65, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantseva, N.V.; Demakov, S.L.; Popov, A.A. Microstructure and plastic deformation of orthorhombic titanium aluminides Ti2AlNb. IV. Formation of the transformation twins upon the α2 → O phase transformation. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2007, 103, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinosho, T.O.; Cocks, A.C.F.; Dunne, F.P.E. Texture, hardening and non-proportionality of strain in BCC polycrystal deformation. Int. J. Plast. 2013, 50, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Tang, B.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Dai, J.; Ma, B.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, J. Formation of equiaxed O bands at the interface of TiAl/Ti2AlNb heterostructures: Abnormal growth of O variants and novel annealed twins. Compos. Commun. 2025, 53, 102243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xue, K.; Meng, M.; Yan, S.; Li, P. High-temperature fracture behavior of Ti−22Al−26Nb with different featured microstructures. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2025, 35, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.R.; Roy, S.; Suwas, S.; Fundenberger, J.J.; Ray, R.K. Annealing response of the intermetallic alloy Ti–22Al–25Nb. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Zeng, W.D.; Xue, C. Effects of hot deformation parameters on lamellar microstructure evolution of Ti2AlNb based alloy. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2014, 24, 1998–2002. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wang, B. Formability and microstructure of Ti22Al24.5Nb0.5Mo rolled sheet within hot gas bulging tests at constant equivalent strain rate. Mater. Des. 2016, 108, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.; Yang, J.; Choi, J.P.; Hwang, J.Y.; Kim, Y.W.; Park, S.J.; Choi, J.W.; Heogh, W.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; et al. Al-based functionally graded super-intermetallic compounds for the turbine blade of a high-performance jet engine. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zeng, W.D.; Wang, W.; Liang, X.B.; Zhang, J.W. The enhanced tensile property by introducing bimodal size distribution of lamellar O for O + B2 Ti2AlNb based alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2013, 587, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, X.; Meng, M.; Fang, X. Spatio-temporal distribution characteristics of coupled field and formation mechanisms of forming defects in electrically-assisted press bending of Ti2AlNb-based alloy stiffened panel. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 122, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hu, R.; Luo, W.; He, T.; Liu, X. Oxidation behavior of a novel multi-element alloyed Ti2AlNb-based alloy in temperature range of 650–850 °C. Rare Met. 2018, 37, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.F.; Li, X.; Li, D.F.; Gu, Y.B.; Fang, H. Temperature distribution and effect of low-density electric current on B2 + O lamellar microstructure of Ti2AlNb alloy sheet during resistance heating. J. Cent. South Univ. 2019, 26, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. Investigation on Electrically Assisted Superplastic Forming/Diffusion Bonding and Its Mechanism of Ti2AlNb Alloy; Harbin Institute of Technology: Harbin, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gogia, A.K.; Nandy, T.K.; Banerjee, D.; Carisey, T.; Strudel, J.L.; Franchet, J.M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of orthorhombic alloys in the Ti-Al-Nb system. Intermetallics 1998, 6, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Research on Three Typical Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Ti-22Al-25Nb Alloy; Northwestern Polytechnical University: Xi’an, China, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Khadzhieva, O.G.; Illarionov, A.G.; Popov, A.A. Effect of aging on structure and properties of quenched alloy based on orthorhombic titanium aluminide Ti2AlNb. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2014, 115, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhen, L.; Yang, D.Z.; Mao, J.F. TEM observation of the α2O interface in a Ti3Al-Nb alloy. Mater. Lett. 1997, 32, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, D.Z.; Song, G.M. The formation mechanism of the O phase in a Ti3Al–Nb alloy. Intermetallics 2000, 8, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hwang, S.K. The effect of aging on microstructure of the O phase in Ti–24Al–14Nb–3V–0.5Mo alloy. Mater. Lett. 2001, 49, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Anand, L. Plasticity of initially textured hexagonal polycrystals at high homologous temperatures: Application to titanium. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Shan, D.; Guo, B.; Zong, Y. Plastic deformation mechanism and interaction of B2, α2, and O phases in Ti–22Al–25Nb alloy at room temperature. Int. J. Plast. 2019, 113, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zeng, W.; Jiang, Y.; Li, D.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, X. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Ti2AlNb Alloy. Titan. Ind. Prog. 2015, 32, 16–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C. Research on the Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Property of the Isothermally Forged Ti-22Al-25Nb Alloys; Northwestern Polytechnical University: Xi’an, China, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Meng, M. Forming Mechanism Study of Tri-Modal Microstructure During Near-Isothermal Local Loading Forming of Large-Scale Component of Titanium Alloys; Northwestern Polytechnical University: Xi’an, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.B.; Cheng, Y.J.; Zhang, J.W.; Li, S.Q. Effects of heat treatment on microstructure and properties of β-forged Ti-22Al-25Nb alloy. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2010, 20, 611–615. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shao, B.; Tang, W.; Guo, S.; Zong, Y.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Investigation of the O phase in the Ti–22Al–25Nb alloy during deformation at elevated temperatures: Plastic deformation mechanism and effect on B2 grain boundary embrittlement. Acta Mater. 2023, 242, 118467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, G.; Yang, J.; Kim, H.S. Electroplasticity mechanism of Ti2AlNb alloys under hot compression with the application of a lower electric current. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 914, 147134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Yan, S.L.; Meng, M.; Li, P. Macro-micro behaviors of Ti-22Al-26Nb alloy during warm tension. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 850, 143580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Yan, S.L.; Meng, M.; Fang, X.G.; Li, P. Macro-micro behaviors of Ti-22Al-26Nb alloy under near iso thermal electrically-assisted tension. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 864, 144573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.C.; Shi, J.D.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.W.; Liang, X.B.; Zhang, J.W. Effects of Heat Treatment Process on Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Ti2AlNb Alloy Forging. Hot Work. Technol. 2022, 51, 119–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zeng, W.D.; Xue, C.; Liang, X.B.; Zhang, J.W. Designed bimodal size lamellar O microstructures in Ti2AlNb based alloy: Microstructural evolution, tensile and creep properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2014, 618, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zeng, W.D.; Xue, C.; Liang, X.B.; Zhang, J.W. Microstructure control and mechanical properties from isothermal forging and heat treatment of Ti–22Al–25Nb (at.%) orthorhombic alloy. Intermetallics 2015, 56, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.