Study on Formation Mechanism of Edge Cracks and Targeted Improvement in Hot-Rolled Sheets of Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

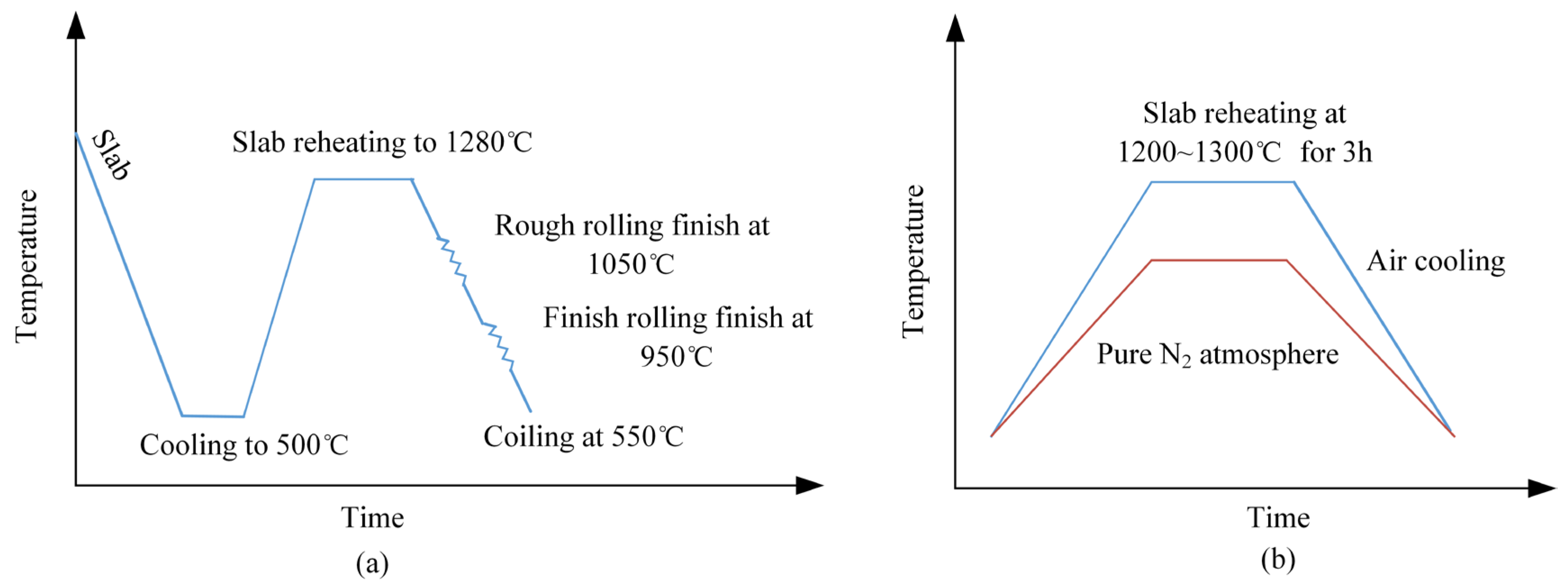

2. Materials and Experimental Methods

3. Formation Mechanism of Edge Crack

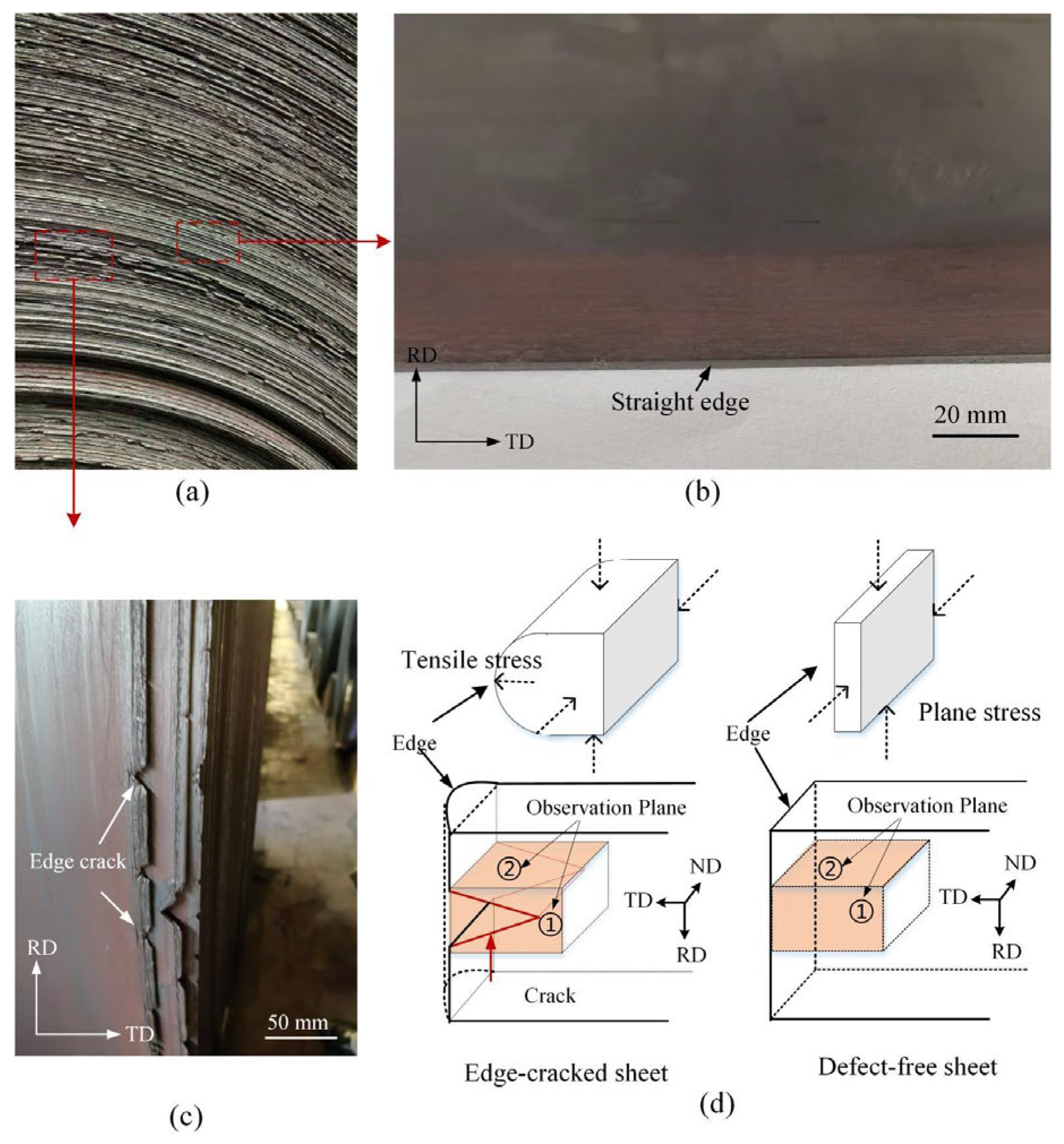

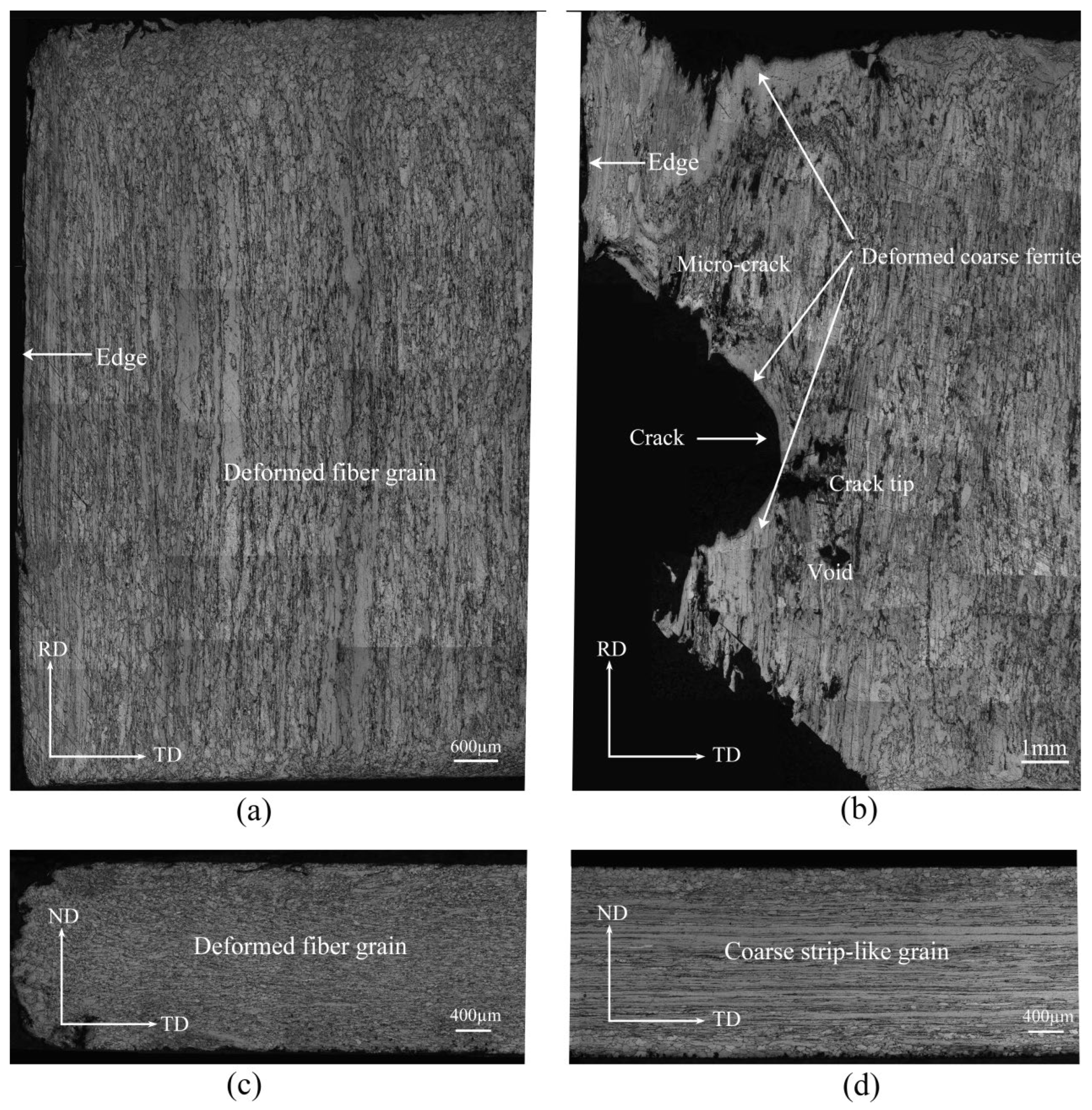

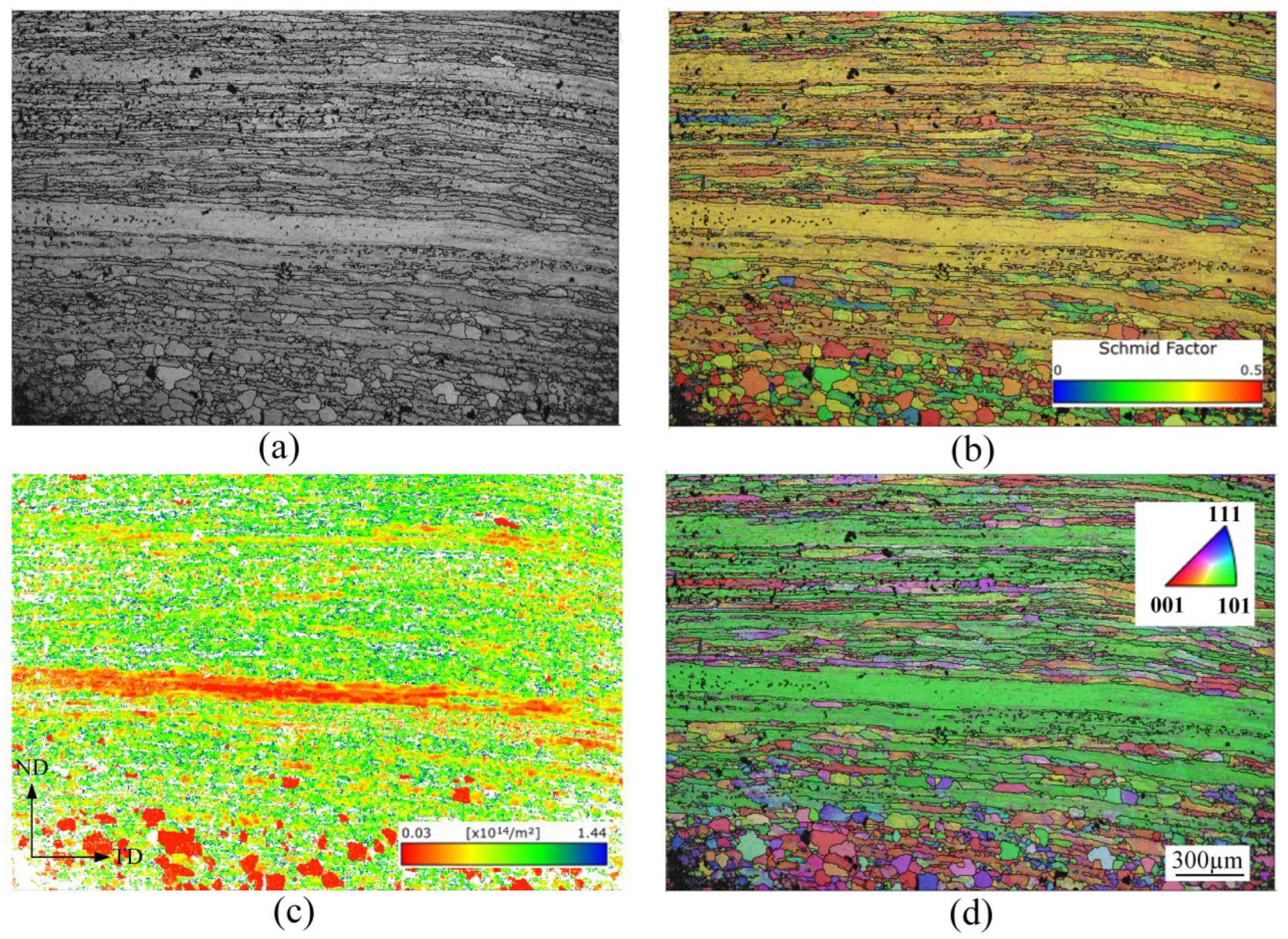

3.1. Macroscopic Characteristics and Microstructure of Edge Crack

3.2. Evolution of Coarse Grain at Slab Edge During Reheating and Rough Rolling

4. Effect of Hot-Rolling Process on Edge Microstructure of Hot-Rolled Sheet

4.1. Effect of Rough Rolling Pass on Microstructure of Hot-Rolled Sheet

4.2. Improvement Measures for Edge Crack of Hot-Rolled Sheet

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Hot-rolled sheets with edge cracks display inhomogeneous microstructures consisting of coarse strip-like grains and deformed fiber grains. The former exhibits a low dislocation density and high Schmid factor, along with numerous microcracks and voids. The latter is sandwiched between coarse strip-like grains and demonstrates a higher dislocation density and a lower Schmid factor.

- (2)

- The bulge-induced internal stress at the slab edge promotes the abnormal growth of columnar grains during high-temperature reheating. The coarse grains would deform preferentially and further elongate during hot rolling, ultimately developing into elongated coarse grains and edge cracks.

- (3)

- Increasing total width reduction and increasing rough rolling passes can enhance recrystallized grain proportion and refine the strip-like grain. Combining these measures can effectively eliminate edge defects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ram, B.S.; Paul, A.K.; Kulkarni, S.V. Soft magnetic materials and their applications in transformers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 537, 168210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.C.; Zook, E.E. A desirable material for transformer cores. J. Mater. Eng. 1989, 11, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, N.J.; Lee, K.J.; Chung, T.; Byun, G. Analysis and prevention of edge cracking phenomenon during hot rolling of non-oriented electrical steel sheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1999, 264, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Guo, H.; Li, H.; Emi, T. Formation of edge crack in 1.4% Si non-oriented electrical steel during hot rolling. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2014, 21, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, W.; Lyu, P.; Yue, C.; Qian, H.; Li, H. Formation mechanism of edge crack during hot rolling process of high-grade non-oriented electrical steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 332, 118577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochinaga, K.; Ichimura, K.; Shibao, S.; Kitahara, S.; Ichikawa, S. Hot Rolling Continuously Cast Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel Slab Reduces Edge Cracking from Redn. Edge Rolling and Increases Continuous Casting Productivity. U.S. Patent 5074931-A, 24 December 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Billen, B.; Feldkamp, J.; Zimmermann, U. Preheating Concast Slab in Two Stages Prior to Hot Rolling to Prevent Edge Cracking in Final Strip. Germany Patent DE4311150-C1, 23 December 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gittins, A. Fracture in hot working of steel. J. Aust. Inst. Met. Incl. Met. Forum 1975, 4, 184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Schey, J.A. Prevention of edge cracking in rolling by means of edge restraint. INST Met. J. 1966, 94, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Littmann, M.F. Development of improved cube-on-edge texture from strand cast 3pct silicon-iron. Metall. Trans. A 1975, 6, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, H.C. The relation between carbon content and hot rolling temperature in developing high induction in boron silicon–iron. J. Appl. Phys. 1982, 53, 8302–8304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, M.; Ikeda, S.; Ito, I.; Suzuki, T. Production of Grain-Oriented Silicon Steel Sheet Having Excellent Surface Characteristic and Magnetic Characteristic. Japanese Patent 59219412-A, 10 December 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, L.N.; Field, D.P.; Merriman, C.C. Mapping and assessing plastic deformation using EBSD. In Electron Backscatter Diffraction in Materials Science; Schwartz, A., Kumar, M., Adams, B., Field, D., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Shi, Q.; Dan, C.; You, X.; Zong, S.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. Resolving localized geometrically necessary dislocation densities in Al-Mg polycrystal via in situ EBSD. Acta Mater. 2024, 279, 120290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shang, X.; Liu, M.; Zhao, S.; Cui, Z. A multiscale investigation on the preferential deformation mechanism of coarse grains in the mixed-grain structure of 316LN steel. Int. J. Plast. 2022, 152, 103244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi, Y.; Shizawa, K. Multiscale crystal plasticity modeling based on geometrically necessary crystal defects and simulation on fine-graining for polycrystal. Int. J. Plast. 2007, 23, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Li, Q.; Yan, Y.; Huang, X.; Yasmeen, T. Study of plastic deformation mechanisms in TA15 titanium alloy by combination of geometrically necessary and statistically-stored dislocations. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2016, 107, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guiu, F. Subcritical fatigue crack growth in alumina—I. Effects of grain size, specimen size and loading mode. Acta Metall. Mater. 1995, 43, 1859–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasaiah, N.; Ray, K.K. Small crack formation in a low carbon steel with banded ferrite–pearlite structure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 392, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Jiang, Z.; Yuen, W.Y.D. Analysis of microstructure effects on edge crack of thin strip during cold rolling. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2011, 42, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Zhang, H.; Cui, Z.; Fu, M.W.; Shao, J. A multiscale investigation into the effect of grain size on void evolution and ductile fracture: Experiments and crystal plasticity modeling. Int. J. Plast. 2020, 125, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, J.; Marko, L.; Kugi, A.; Steinboeck, A. Mathematical modeling and system analysis for preventing unsteady bulging in continuous slab casting machines. J. Process Control 2024, 139, 103232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Song, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C.; Wang, Y. Early interlaminar cracks and tensile fractures in Non-oriented electrical sheets caused by uncoordinated deformations during cold rolling. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 127, 105573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wei, L.; Fu, B.; Tao, B. Analysis on mechanism of edge crack of high grade 3.28% Si steel cold-rolled sheet and process improvement. Spec. Steel 2018, 39, 13. [Google Scholar]

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Als | N | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.030~0.042 | 3.05~3.30 | 0.19~0.22 | ≤0.016 | 0.004~0.009 | 0.016~0.024 | 0.0075~0.0108 | 0.48~0.52 |

| Total Reduction in Rough Rolling | Passes of Rough Rolling | |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental group 1 | A | D |

| Experimental group 2 | B | D |

| Experimental group 3 | C | D |

| Experimental group 4 | C | E |

| Yield Strength/Mpa | Tensile Strength/Mpa | |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental group 1 | 438 | 557 |

| Experimental group 2 | 460 | 584 |

| Experimental group 3 | 477 | 601 |

| Experimental group 4 | 481 | 627 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, W.; Tang, H.; Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Piao, Z.; Dai, F. Study on Formation Mechanism of Edge Cracks and Targeted Improvement in Hot-Rolled Sheets of Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel. Metals 2026, 16, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010096

Zeng W, Tang H, Tang X, Wang J, Piao Z, Dai F. Study on Formation Mechanism of Edge Cracks and Targeted Improvement in Hot-Rolled Sheets of Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel. Metals. 2026; 16(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Weidong, Hui Tang, Xiaoyong Tang, Jiaming Wang, Zhongyu Piao, and Fangqin Dai. 2026. "Study on Formation Mechanism of Edge Cracks and Targeted Improvement in Hot-Rolled Sheets of Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel" Metals 16, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010096

APA StyleZeng, W., Tang, H., Tang, X., Wang, J., Piao, Z., & Dai, F. (2026). Study on Formation Mechanism of Edge Cracks and Targeted Improvement in Hot-Rolled Sheets of Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel. Metals, 16(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010096