Abstract

The effect of Ni content on the improvement of low-temperature impact toughness and microstructure refinement in a simulated coarse-grained heat-affected zone (CGHAZ) of high-strength steel was studied. The impact toughness tests revealed that as the heat input increased from 20 to 50 kJ/cm, both low-nickel (L-Ni) steel and high-nickel (H-Ni) steel exhibited a rapid decline in the impact toughness of their coarse-grained heat-affected zones (CGHAZ), though the H-Ni steel consistently demonstrated significantly higher impact toughness than the L-Ni steel. Microstructural characterization showed that the microstructure of L-Ni steel gradually transitioned from lath bainite (LB) to granular bainite (GB) with increasing heat input, which accounted for its reduced impact toughness. Conversely, H-Ni steel underwent a phase transformation from lath martensite (LM) to LB with increasing heat input, showing an unexpected trend opposite to the conventional understanding of toughness enhancement. Notably, the martensitic structure obtained in H-Ni steel at 20 kJ/cm exhibited substantially higher impact energy (59.6 J) than both the LB structures of L-Ni steel (44.6 J) and those of H-Ni steel (37.8 J) observed at 20 and 50 kJ/cm heat inputs. This phenomenon is attributed to the increased Ni content significantly refining the packet of LM, thereby enhancing its resistance to brittle crack propagation. Although LB structures obtained under different conditions exhibited refined blocks, their parallel arrangement within coarse packets resulted in less effective obstruction of brittle crack propagation compared to the refined packet with interlocking arrangement.

1. Introduction

To enhance strength and toughness, high-strength steels typically incorporate a certain amount of Ni, which stabilizes austenite and lowers the ferrite phase transformation temperature [1,2,3]. Research [4] indicates that a 1 wt.% increase in Ni content reduces the impact transition temperature by approximately 20 °C. Another study [5] has demonstrated that increasing Ni content from 0.92 wt.% to 2.94% can lower the ductile-brittle transition temperature (DBTT) of 1000 MPa-grade hydropower steel from −35 °C to −80 °C. Elevated Ni levels can enhance the density of high-angle grain boundaries, promoting refinement of block and packet structures [6,7,8]. Additionally, stacking fault energy (SFE) increases with higher Ni content, facilitating cross-slip of screw dislocations at low temperatures and thereby improving low-temperature plasticity [5,9,10].

Investigations into the effects of increased Ni content on weld microstructure and properties reveal that Ni can suppress the formation of grain boundary ferrite (GBF) in weld metal while refining acicular ferrite (AF), consequently enhancing both strength and toughness [11]. Ni also can promote bainitic transformation while inhibiting the formation of brittle martensite in M/A (martensite/austenite) constituents, effectively toughening M/A components in the intercritically coarse-grained heat-affected zone (ICCGHAZ) and improving its low-temperature toughness [12]. Furthermore, in the coarse-grained heat-affected zone (CGHAZ), Ni facilitates the formation of AF, significantly enhancing crack tip opening displacement (CTOD) performance [13,14]. However, the addition of Ni may also enhance the propensity for martensite formation [15], and its impact on the low-temperature impact toughness of the CGHAZ remains incompletely understood. Furthermore, the coupled effects of Ni content and welding heat input on the variant selection mechanisms and crystallographic characteristics of bainite/martensite in the CGHAZ require further in-depth investigation.

Therefore, this study takes 800 MPa grade high-strength steel for engineering machinery as the research object, designs two types of experimental steels with different nickel (Ni) contents (1.15 wt.% and 3.2 wt.%), and conducts welding simulation experiments under different heat input conditions. The purpose is to simulate the action laws of heat input and nickel content on the microstructure and low-temperature impact toughness of the CGHAZ under the submerged arc welding (SAW) process (with relatively high heat input). Combined with the analysis of microstructure crystallography and the interpretation of phase transformation mechanisms, the coupled action mechanism of Ni content and heat input on the phase transformation of the CGHAZ microstructure was determined.

2. Materials and Methods

Two types of high-strength steels with different Ni contents were adopted in this study, with Ni contents of 1.15 wt.% and 3.2 wt.%, respectively. These steels were sourced from BAOSTEEL (Shanghai, China) and fabricated via the quenching and tempering (QT) process. Their chemical compositions are presented in Table 1, and the two steel plates with thickness of 50 mm are designated as L-Ni steel and H-Ni steel, respectively. Gleeble-3500 thermal-mechanical simulator (GTC, Dynamic Systems Inc., Poestenkill, NY, USA) was employed to conduct simulation experiments of the CGHAZ. The heat input parameters were set at 20, 30 and 50 kJ/cm, respectively. Based on the thermal cycle curves, the average cooling rates in the critical phase transformation zone (Δt8/5, cooling rate from 800 to 500 °C) corresponding to the above heat input conditions were calculated to be approximately 15.3, 6.8 and 2.4 °C/s. Considering that this type of high-strength steel is typically joined by submerged arc welding (SAW), and based on welding simulation calculations as well as numerous previous studies on simulated CGHAZ [16,17], the heating rate of the thermal cycle process was designed to be 130 °C/s, with a peak temperature of 1350 °C and a holding time of 1 s. The simulated samples with dimension of 60 mm × 11 mm × 11 mm (without a notch) were cut along the transverse direction of steel plate. After thermal simulation, standard impact specimens with the size of 10 mm × 10 mm × 55 mm were prepared to evaluate Charpy V-notch (CVN) impact toughness at −20 °C, according to ASTM E2298 [18]. The V-notch of the impact specimen was located at the center of the thermally simulated sample. After the impact test was completed, the morphology of the impact fracture was characterized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic), and metallographic specimens were sectioned from the heat-treated zone for metallographic microstructure characterization.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of experimental steels (wt.%).

For microstructure and secondary crack characterization, metallographic specimens were subjected to mechanical grinding and polishing and etched with 4% nital for SEM observation. Electron back-scattering diffraction (EBSD) was subsequently employed for crystallographic analysis of the microstructure and crack propagation paths. EBSD scanning was performed at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV, working distance of 17 mm, and step size of 0.15 μm. For EBSD examination, the samples were re-prepared by mechanical grinding, polishing, and subsequent electrolytic polishing in a solution of glycerol, ethyl alcohol and perchloric acid (5:85:10, volume fraction) under 20 V for 20 s. Channel 5 software from Oxford-HKL (6.1, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) was employed for post-processing orientation data. Through variant selection calculations and crystallographic structure visualization method [16], the combined effects of Ni content and heat input on phase transformation mechanisms and impact toughness in CGHAZ were systematically elucidated. Furthermore, to clarify the effect of Ni content on the cooling phase transformation of the experimental steels, JMatPro software (V12.1) was employed to calculate the continuous cooling transformation (CCT) curves of the two experimental steels.

3. Results

3.1. Impact Toughness and Fractographs of the Simulated Samples

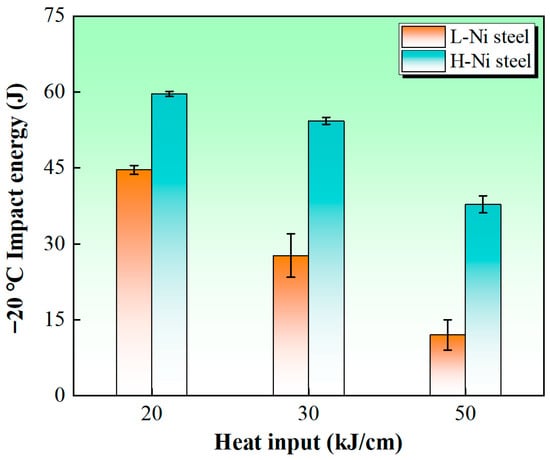

Figure 1 first presents the impact toughness characteristics of the simulated CGHAZ of experimental steels with different Ni contents at −20 °C. It can be observed that the impact energy of both steels gradually decreases with increasing heat input, but the H-Ni steel consistently maintains superior toughness performance with a relatively weaker downward trend in impact energy. The decreasing trend of impact energy with increasing heat input is associated with the reduced Δt8/5 cooling rate caused by higher heat input [17,19,20]. Specifically, a slower cooling rate promotes the formation of coarser intermediate-temperature transformation products, which are known to impair low-temperature toughness. Conversely, excessively low heat input can also increase the tendency for martensite formation, similarly deteriorating low-temperature impact toughness [17,21]. However, the increase in Ni content is found to significantly enhance the low-temperature impact toughness of the CGHAZ. Even under relatively high heat input conditions, the CGHAZ can still achieve relatively high impact toughness. This should be related to Ni promoting the low-temperature bainite transformation. Increased Ni content can inhibit the formation of brittle microstructures such as M/A constituents, facilitating a more complete low-temperature bainite transformation [12]. This refines the transformed microstructure and improves crack propagation resistance.

Figure 1.

Charpy impact toughness of the simulated CGHAZ with different Ni content.

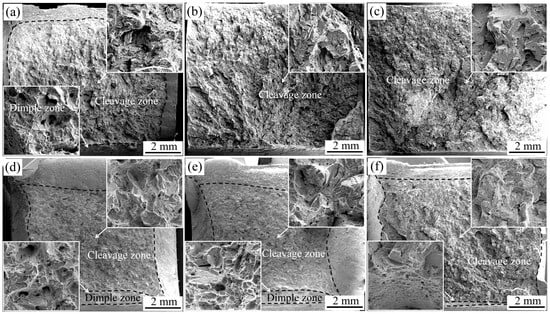

Figure 2 further presents the SEM images of impact fracture morphologies of the two experimental steels under different heat input conditions. It can be observed that with the increase in heat input, the proportion of the ductile fracture zone gradually decreases, replaced by the cleavage zone. Unlike the L-Ni steel, the impact fractures of the H-Ni steel exhibit certain ductile fracture characteristics under all three heat input conditions, showing a typical dimple morphology. In addition, its cleavage zone does not present the feature of large-sized complete cleavage facets as shown in Figure 2c, but rather a complex distribution of dimples, tear ridges, and cleavage facets. This is also the key reason for ensuring relatively excellent impact toughness even under relatively high heat input conditions. It can thus be seen that the increase in Ni can refine the cleavage units of the impact fracture, which is closely related to its decisive effect on the transformed microstructure.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs showing the fracture surface after Charpy impact tests for the simulated CGHZ with (a–c) low and (d–f) high Ni content under (a,d) 20, (b,e) 30 and (c,f) 50 kJ/cm.

3.2. Microstructure Evolution in Base Metal and Simulated Samples and Phase Transformation Mechanisms

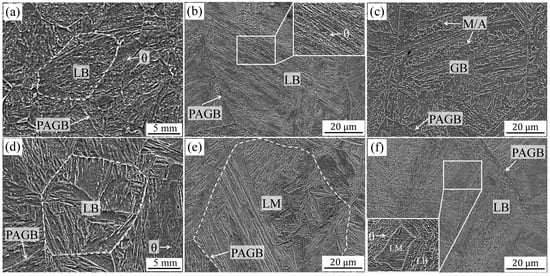

Figure 3 presents the initial microstructures of the two experimental steels after the same heat treatment (holding at 880 °C for 1 h followed by quenching), as well as the SEM images of the simulated CGHAZ microstructures after heat inputs of 20 and 50 kJ/cm. First, a comparison of the initial microstructures of the two experimental steels (Figure 3a,d) shows that compared with the L-Ni steel (average diameter: ~9.7 μm), the H-Ni steel has coarser prior austenite grains (average diameter: ~15 μm) but finer lath bainite (LB) structures, with a lower precipitation content of cementite (θ). This phenomenon originates from the dual effects of nickel: first, enhancing the stability of high-temperature austenite, and second, promoting low-temperature phase transformation [1,5,12].

Figure 3.

SEM images showing the microstructure of the (a,d) base metal and (b,c,e,f) simulated CGHAZ with heat input of (b,e) 20 and (c,f) 50 kJ/cm: (a–c) L-Ni steel and (d–f) H-Ni steel.

Based on the nearly linear decreasing trend of impact energy with increasing heat input, Figure 3b, Figure 3c, Figure 3e, and Figure 3f comparatively analyze the SEM microstructures of the CGHAZ of the two experimental steels under heat inputs of 20 and 50 kJ/cm, respectively. Significant differences are observed in the microstructural evolution after thermal simulation: the H-Ni steel forms typical lath martensite (LM) at 20 kJ/cm (Figure 3e), and transforms into a structure dominated by LB with a small amount of LM at 50 kJ/cm (Figure 3f); in contrast, the L-Ni steel consists of LB at 20 kJ/cm (Figure 3b), and converts to granular bainite (GB) accompanied by coarse M/A constituents at 50 kJ/cm (Figure 3c). Previous studies [17,19,21] have indicated that excessively high heat input leads to coarse GB structure, which significantly reduces low-temperature toughness, while LB structure exhibit superior toughness; however, excessively low heat input promotes martensite formation, which also deteriorates toughness. The changes in the microstructure and impact toughness of the CGHAZ in the L-Ni steel exactly conform to this law. Notably, the impact energy of the LM structure in the H-Ni steel at 20 kJ/cm is not only higher than that of its own LB structure at 50 kJ/cm but also superior to the LB structure of the L-Ni steel under the same heat input. This contradicts the conventional understanding [22,23,24] that “low-carbon bainite typically outperforms lath martensite in low-temperature toughness.” To clarify this abnormal phenomenon, the grain boundary distribution characteristics of the corresponding structures, as well as the visualized crystallographic packet and block morphologies, are further analyzed.

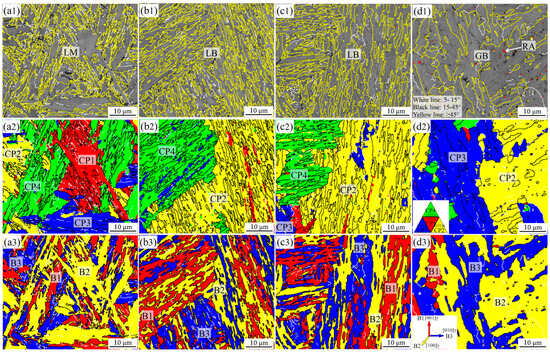

Figure 4 further characterizes the crystallographic structures of the four simulated CGHAZ microstructures described in Figure 3 using EBSD. Figure 4(a1–d1) present the grain boundary density distribution maps of the four microstructures, where yellow lines represent grain boundaries with misorientation greater than 45°, black lines denote those with misorientation between 15° and 45°, and white lines correspond to those with misorientation between 5° and 15°. Comparative analysis reveals that the LB structure obtained in the two experimental steels under different heat input conditions exhibit the highest density of high-angle grain boundaries (yellow lines, Figure 4(b1,c1)). In contrast, the GB structure (Figure 4(d1)), where retained austenite (RA) serves as part of the M/A constituents, has the lowest high-angle grain boundary density, while the LM structure (Figure 4(a1)) shows an intermediate high-angle grain boundary density. This is generally consistent with previous research findings [17,21]: the block boundaries of LB structure formed at the nose temperature of the bainite transformation curve are entirely composed of high-angle grain boundaries, with a density significantly higher than that of GB and LM structures. Block boundaries are typically composed of grain boundaries with misorientation greater than 45°, which play a crucial role in hindering the propagation of brittle cracks [25,26,27].

Figure 4.

EBSD maps showing the (a1–d1) grain boundaries distribution, (a2–d2) packet and (a3–d3) block morphology of simulated CGHAZ with heat input of (a1–a3,b1–b3) 20 and (c1–c3,d1–d3) 50 kJ/cm (corresponding to LM, LB and GB structures in Figure 3b,c,e,f): (a1–a3,c1–c3) H-Ni steel and (b1–b3,d1–d3) L-Ni steel.

However, the impact toughness results shown in Figure 1 indicate that the LM structure in the H-Ni steel achieves the highest impact energy, which seems contradictory to its relatively low high-angle grain boundary density. Further analysis combined with the visualized results of packets (Figure 4(a2–d2)) and blocks (Figure 4(a3–d3)) reveals that the packets in the LM (Figure 4(a2)) structure exhibit an interlaced distribution and relatively small size, whereas the LB (Figure 4(b2,c2)) and GB (Figure 4(d2)) structures are dominated by typical large-sized packets. Additionally, regarding the block distribution characteristics, the differently colored block units in the LM (Figure 4(a3)) structure have a certain thickness size effect and exhibit an interspersed and interlaced arrangement, which is significantly different from the elongated and directionally distributed blocks in the LB structure (Figure 4(b3,c3)). This unique morphology may be one of the reasons for its superior low-temperature toughness compared to LB structure. Previous studies [16,28] have also shown that when bainite or martensite lath bundles are arranged in parallel, their resistance to crack propagation parallel to these lath bundles is relatively low. The increase in Ni promotes the refinement and irregular distribution of martensite packets, thereby exerting a positive effect on improving low-temperature impact toughness. This should be mainly attributed to nickel enhancing the driving force of martensitic transformation.

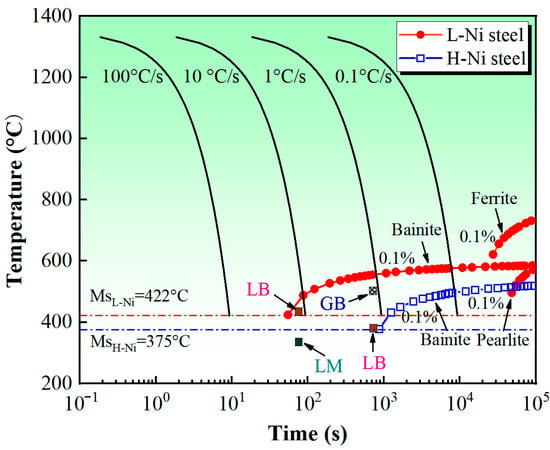

Figure 5 presents the continuous cooling transformation (CCT) curves of the two experimental steels calculated based on their chemical compositions. It can be observed that as the Ni content increases from 1.15 wt.% to 3.2 wt.%, the start temperatures of both bainite and martensite transformations decrease significantly, with a temperature drop of nearly 50 °C. This enables the formation of LB structure in the H-Ni steel at a lower cooling rate, further confirming that it can obtain the LB structure and relatively excellent impact energy under the heat input condition of 50 kJ/cm. In contrast, under the same cooling rate, the L-Ni steel can only form the GB structure. Naturally, at a relatively high cooling rate, the L-Ni steel can also obtain the LB structure, while the H-Ni steel will form the LM structure. This can be further confirmed by the phase transformation driving force calculation results in Figure 6a. The increase in Ni content significantly enhances the phase transformation driving forces of both bainite and martensite while lowering their formation temperatures. Of course, previous studies have shown [29,30] that during isothermal quenching, the addition of Ni reduces the bainite phase transformation driving force. This is because Ni is an austenite-stabilizing element that enhances the stability of austenite, thereby decreasing the chemical driving force for the transformation of austenite to bainite. Obviously, the present study involves continuous cooling rather than isothermal transformation.

Figure 5.

CCT diagram of the two studied steels.

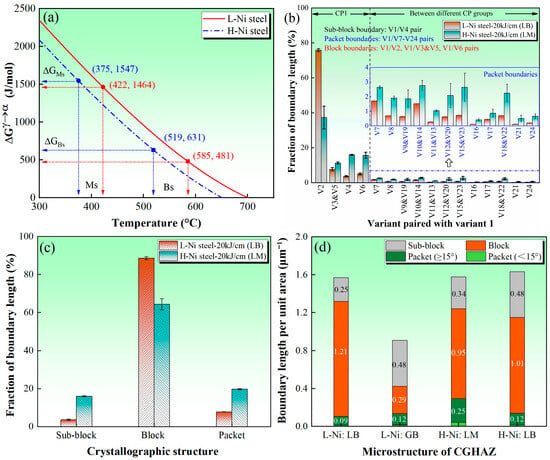

Figure 6.

(a) Driving force of two studied steel, (b,c) density of intervariant boundaries obtained in LM and LB structure (20 kJ/cm), (d) boundary length per unit area obtained in the four structures.

To further clarify why the refinement effect of crystallographic structure units in the LM structure of the H-Ni steel is more significant, microscopic structure digitization and quantitative calculation methods [16,17] were used to compare and present the quantitative results of the CGHAZ microstructures of the H-Ni steel and L-Ni steel under the heat input of 20 kJ/cm, as shown in Figure 6b,c. Under the heat input of 20 kJ/cm, the L-Ni steel is more prone to promoting the formation of V1/V2 variant pairs (block boundary); in contrast, the H-Ni steel tends to form other variant pairs, namely V1/V5 and V1/V6 (block boundaries), V1/V4 (sub-block boundary), and V1/V7-V24 (packet boundaries). This indicates that the LM structure in the H-Ni steel has a weaker tendency for variant selection. Figure 6c further presents the statistical results of the proportion of three typical crystallographic structure boundaries in the two microstructures. It can be seen that the LB structure obtained in the L-Ni steel is dominated by block boundaries, while the LM structure obtained in the H-Ni steel has significantly higher proportions of packet and sub-block boundaries than the L-Ni steel. Furthermore, Figure 6d shows the statistical results of the density of various boundaries per unit area for the four CGHAZ microstructures. It is observed that the GB structure has the lowest block boundary density due to its coarser crystallographic structure; the LB structure has the highest density of block boundaries; and the LM structure possesses a higher density of packet boundaries.

Previous studies [25,31] have confirmed that both packet and block boundaries make significant contributions to impact toughness, especially when their misorientation exceeds 15°. Although the block boundary density of the LM structure in the H-Ni steel is lower than that of the LB structure in the L-Ni steel, the difference in their high-angle grain boundary densities is not significant. This indicates that the fundamental reason for the difference in impact toughness between the two is not attributed to the difference in grain boundary density, but rather to the type and distribution characteristics of grain boundaries. Due to the higher density of packet boundaries and their irregular interlaced arrangement, the LM structure exhibits superior low-temperature impact toughness compared to the LB structure. To further validate this conclusion, the propagation behavior of brittle cracks in the three microstructures during the impact process is presented in Figure 7.

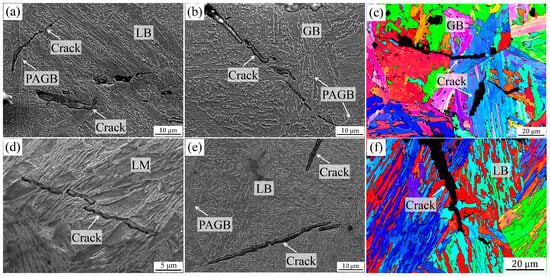

Figure 7.

Relationship of secondary crack propagation path and crystallographic structure obtained from the impact fracture sample of CGHAZ with heat input of (a,d) 20 and (b,c,e,f) 50 kJ/cm: (a–c) L-Ni steel and (d–f) H-Ni steel.

3.3. Crack Propagation Mechanisms in Simulated Samples

Figure 7 presents the brittle crack propagation behavior in the four simulated CGHAZ microstructures using SEM and EBSD, respectively. As shown in Figure 7a, when the brittle crack propagation direction is perpendicular to the LB lath bundles or when it needs to cross the prior austenite grain boundaries (PAGBs), the crack encounters significant resistance, undergoes obvious deflection, and exhibits a small size. In contrast, when the brittle crack propagates in the GB structure (Figure 7b,c), due to the low density of high-angle grain boundaries and the coarse crystallographic structure units, the crack propagation resistance is weak, resulting in a relatively straight morphology and a longer propagation distance. For the LM structure obtained in the H-Ni steel (Figure 7d), the brittle crack also encounters considerable resistance when propagating within different lath bundle structure units. The crack undergoes significant deflection or dislocation, leading to discontinuous propagation, which plays a positive role in improving the impact energy absorption. On the contrary, in the LB structure with an approximately parallel arrangement, the brittle crack propagates at an angle of nearly 45° to the lath bundles. Due to the small size (thickness) of the lath bundles, the deflection and hindrance effect on crack propagation is reduced, resulting in a relatively straight and large-sized brittle crack morphology. It can thus be concluded that to achieve excellent low-temperature impact toughness in the CGHAZ, in addition to refining the microstructure and crystallographic structure units, attention should also be paid to the arrangement of various crystallographic units. Ni appears to play a positive role in regulating martensitic crystallographic structure units and weakening variant selection.

3.4. Overall Discussion

The aforementioned studies demonstrate that an increase in Ni content can indeed enhance the low-temperature impact toughness of the simulated welded CGHAZ of low-alloy high-strength steels. Although higher Ni content facilitates the formation of the LM structure in the CGHAZ under lower heat input conditions, its regulatory effect on the phase transformation of the crystallographic structure weakens variant selection. This leads to the refinement and staggered arrangement of packets, which significantly improves the resistance to brittle crack propagation, thereby resulting in excellent macroscopic low-temperature impact toughness.

A previous study [7] on Ni have demonstrated that increasing the Ni content from 0.92 wt.% to 2.94 wt.% can significantly enhance the hardenability of low-alloy steels, reduce the start and finish temperatures of phase transformation at the same cooling rate, and facilitate the formation of lath bainite instead of granular bainite in H-Ni steel even at relatively low cooling rates. This is consistent with the findings of the present study. Another studies [3,32] have also indicated that Ni can lower the free energy barrier of bainitic transformation, refine the bainite/martensite microstructure, and increase the dislocation density. The material is thereby strengthened and toughened through the combined effects of high-angle grain boundary strengthening and solid solution strengthening. Furthermore, recent study has [5] also indicated that increasing the Ni content can enhance the grain boundary density on the {110} crystal planes, thereby increasing the number of dislocation pile-up sites and improving the ability to resist reaching the fracture strength. H-Ni steel is more prone to plastic deformation at low temperatures, with higher mobile dislocation density and stacking fault energy, which is also one of the key reasons why H-Ni steels can achieve superior low-temperature toughness.

Regarding the effect of increased Ni content on the low-temperature impact toughness of the simulated CGHAZ, study [33] on low-carbon martensitic steels has indicated that the simulated CGHAZ of steels containing 7 wt.% Ni exhibits significantly superior low-temperature impact toughness in a liquid nitrogen environment compared to that of steels with 9 wt.% Ni. This is mainly attributed to the higher density of high-angle grain boundaries achieved in the former. In low-alloy steels [12], increasing the Ni content from 0.81 wt.% to 3.74 wt.% can not only further refine the microstructure of the simulated CGHAZ but also effectively promote the complete transformation of M/A constituents, thereby reducing their size. In the present study, the increase in Ni content also exerted a considerable influence on the phase transformation behavior of the CGHAZ microstructure. This enables high-strength steels to obtain the LB structure under higher heat input conditions (lower Δt8/5 cooling rate), which also ensures the CGHAZ achieves superior low-temperature impact toughness. These findings provide a reasonable compositional design approach for high-strength steels to adapt to high-efficiency welding (with high heat input), and hold profound developmental significance especially for welding projects involving thick or extra-thick plates.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Increasing Ni content (from 1.15 wt.% to 3.2 wt.%) significantly enhances the low-temperature (−20 °C) impact toughness of the simulated welded CGHAZ of low-alloy high-strength steels, enabling the CGHAZ to maintain excellent toughness even under relatively high heat input conditions. For the H-Ni steel, the simulated CGHAZ achieved average impact energy values of 59.6, 54.3 and 37.8 J under the heat input conditions of 20, 30 and 50 kJ/cm, respectively. In contrast, the average impact energy values of the L-Ni steel under the same heat input conditions were 44.6, 27.7 and 12 J, respectively.

- (2)

- Ni regulates the phase transformation and crystallographic structure of the CGHAZ: it weakens martensite variant selection, leading to refined and staggered packet arrangements in the LM structure, and promotes low-temperature bainite transformation to form LB structure at lower cooling rates, both improving brittle crack propagation resistance.

- (3)

- The superior low-temperature impact toughness of the H-Ni steel’s CGHAZ is attributed to the higher density of packet boundaries in its microstructure, as well as the irregular interlaced distribution of crystallographic units, rather than just grain boundary density, providing a reasonable compositional design for high-strength steels in high-efficiency (high heat input) welding of thick/extra-thick plates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z., Z.L. and X.W.; methodology, Z.L. and L.L.; validation, Y.L. and Y.Y.; data curation, Y.L. and Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.W.; visualization, L.L.; supervision, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of CITIC Group (No. 2022zxkya06100), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52001023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Xuelin Wang from University of Science and Technology Beijing for his guidance and support on the simulated welding process in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Guodong Zhang and Zhongzhu Liu were employed by the company CITIC Metal Co., Ltd. Authors Lixia Li, Yuanyuan Li and Yanli Yang were employed by the company CITIC Heavy Industries Co., Ltd. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Morris, J.W., Jr.; Guo, Z.; Krenn, C.R.; Kim, Y.-H. The limits of strength and toughness in steel. ISIJ Int. 2001, 41, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, A.H.; Anijdan, S.M.; Abbasi, S. The effect of increasing Cu and Ni on a significant enhancement of mechanical properties of high strength low alloy, low carbon steels of HSLA-100 type. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 746, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.Y.; Hu, C.Y.; Wu, G.H.; Wu, K.M.; Misra, R.D.K. Effect of nickel on hardening behavior and mechanical properties of nanostructured bainite-austenite steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 817, 141410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norström, L.Å.; Vingsbo, O. Influence of nickel on toughness and ductile-brittle transition in low-carbon martensite steels. Met. Sci. 1979, 13, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.Q.; Zhao, J.X.; Wang, X.L.; Shang, C.J.; Zhou, W.H. New insights from crystallography into the effect of Ni content on ductile-brittle transition temperature of 1000 MPa grade high-strength low-alloy steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, S.C.; Chai, F.; Luo, X.B.; Ma, S.; Shi, Z.R.; Chai, X.Y.; Wang, Z.M. Effect of the Ni content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Cu-bearing high-strength steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 943, 148762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Han, P.; Yang, S.W.; Wang, H.; Jin, Y.H.; Shang, C.J. Crystallographic understanding of the effect of Ni content on the hardenability of high-strength low-alloy steel. Acta Metall. Sin. 2024, 60, 789–801. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, W.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Geng, R.M.; Cao, Y.X.; Han, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.X.; Zheng, L.J. Microstructures and mechanical properties of novel 2.3 GPa secondary hardening steels with different Ni contents. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.L.; Ji, Y.F.; Wang, P.J.; Wu, S.W.; Cao, G.M.; Liu, Z.Y. Cryogenic impact toughness of 5.5% Ni steel at 196 °C: Synergy of a dual-phase heterogeneous lamellar structure and the stability of reversed austenite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 943, 148740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.Z.; Xu, T.F.; Xu, J.K.; Li, W.J.; Zhang, H.L.; Hou, J.P. Effect of microstructural homogeneity on ultra-low temperature impact fracture mechanism of high-strength 9%Ni steel. Mater. Des. 2025, 256, 114318. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Dong, L.M.; Yang, W.W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.M.; Shang, C.J. Effect of Mn, Ni, Mo proportion on microstructure and mechanical properties of weld metal of K65 pipeline steel. Acta Metall. Sin. 2016, 52, 649–660. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.; Shang, C.J.; Subramanian, S. Effect of Ni addition on toughness and microstructure evolution in coarse grain heat affected zone. Met. Mater. Int. 2014, 20, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Lee, D.H.; Sohn, S.S.; Kim, W.G.; Um, K.K.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, S. Effects of Ni and Mn addition on critical crack tip opening displacement (CTOD) of weld-simulated heat-affected zones of three high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 697, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.L.; Jia, S.J.; Liu, Q.Y.; Shang, C.J. Effects of Cr and Ni addition on critical crack tip opening displacement (CTOD) and supercritical CO2 low-alloy steel (HSLAs). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 908, 146772. [Google Scholar]

- Mohrbacher, H.; Kern, A. Nickel alloying in carbon steel: Fundamentals and applications. Alloys 2023, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Xie, Z.J.; Li, X.C.; Shang, C.J. Recent progress in visualization and digitization of coherent transformation structures and application in high-strength steel. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 1298–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, Z.Q.; Dong, L.L.; Shang, C.J.; Ma, X.P.; Subramanian, S.V. New insights into the mechanism of cooling rate on the impact toughness of coarse grained heat affected zone from the aspect of variant selection. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 704, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E2298-18; Standard Test Method for Instrumented Impact Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Yang, X.C.; Di, X.J.; Liu, X.G.; Wang, D.P.; Li, C.N. Effects of heat input on microstructure and fracture toughness of simulated coarse-grained heat affected zone for HSLA steels. Mater. Charact. 2019, 155, 109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.L.; An, T.B.; Cao, Z.L.; Zuo, Y.; Ma, C.Y.; Kang, J. Effect of heat input on microstructure, variant pairing, and impact toughness of CGHAZ in 1000 MPa-grade marine engineering steel. Structures 2025, 77, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.N.; Huan, P.C.; Wang, X.N.; Di, H.S.; Shen, X.J.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Z.G.; He, J.R. Study on the mechanism of heat input on the grain boundary distribution and impact toughness in CGHAZ of X100 pipeline steel from the aspect of variant. Mater. Charact. 2021, 179, 111344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Nie, P.L.; Qu, Z.X.; Ojo, O.A.; Xia, L.Q.; Li, Z.G.; Huang, J. Influence of heat input on the changes in the microstructure and fracture behavior of laser welded 800MPa grade high-strength low-alloy steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 50, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, S.Z.; Yu, H.; Mao, X.P. Achieving enhanced cryogenic toughness in a 1 GPa grade HSLA steel through reverse transformation of martensite. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 6696–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.Y.; Yang, R.X.; Sun, D.Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.C.; Yang, Z.N.; Li, Y.G. Roles of cooling rate of undercooled austenite on isothermal transformation kinetics, microstructure, and impact toughness of bainitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 870, 144821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morito, S.; Yoshida, H.; Maki, T.; Huang, X. Effect of block size on the strength of lath martensite in low carbon steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 438–440, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgues, A.-F.; Flower, H.M.; Lindley, T.C. Electron backscattering diffraction study of acicular ferrite, bainite, and martensite steel microstructures. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2000, 16, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Argon, A.S. Cleavage cracking resistance of high angle grain boundaries in Fe-3%Si alloy. Mech. Mater. 2003, 35, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, Z.Q.; Ma, X.P.; Subramanian, S.V.; Xie, Z.J.; Shang, C.J.; Li, X.C. Analysis of impact toughness scatter in simulated coarse-grained HAZ of E550 grade offshore engineering steel from the aspect of crystallographic structure. Mater. Charact. 2018, 140, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.Y.; Xu, G.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Hu, H.J.; Zhou, M.M. Effect of Ni addition on bainite transformation and properties in a 2000 MPa grade ultrahigh strength bainitic steel. Met. Mater. Int. 2018, 24, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Van Der Wolk, P.J.; Van Der Zwaag, S. On the influence of alloying elements on the bainite reaction in low alloy steels during continuous cooling. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 4393–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancel, L.; Gómez, M.; Medina, S.F.; Gutierrez, I. Measurement of bainite packet size and its influence on cleavage fracture in a medium carbon bainitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 530, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.T.; Liu, W.S.; Ma, Y.Z.; Cai, Q.S.; Zhu, W.T.; Li, J. Effect of Ni addition upon microstructure and mechanical properties of hot isostatic pressed 30CrMnSiNi2A ultrahigh strength steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 850, 143599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Cai, Y.; Wang, B.S.; Mu, W.D.; Xin, D.Q. Effect of microstructure synergism on cryogenic toughness for CGHAZ of low-carbon martensitic steel containing nickel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 830, 142240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).