1. Introduction

The core concept emerging in 2004 is that mixing multiple metallic elements in equiatomic ratios creates high-entropy alloys (HEAs) [

1,

2]. The high configurational entropy of mixing stabilizes bcc/fcc solid solution by lowering the Gibbs free energy [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], endowing these materials with unique, in-demand properties [

3,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. While initially investigated as alternatives to conventional structural alloys [

10,

11,

12,

13,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], research has increasingly pivoted toward their functional applications [

14,

21,

22,

23]. Catalysis has emerged as a particularly promising area, as HEAs can facilitate reactions that are impossible with other materials [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. A significant advantage of HEA-derived catalysts is the ability to engineer surfaces with a diverse composition, placing different types of catalytically active sites in immediate proximity. HEAs are promising catalysts for various gas-phase [

28,

29], liquid-phase [

30], and electrocatalytic [

24,

31,

32] reactions, but their effectiveness is often limited by their low specific surface area, which restricts reagent access. Strategies to overcome this include converting bulk HEAs into nanoscale form [

33,

34,

35], synthesizing them directly onto porous supports like oxides and carbon nanotubes, and applying etching techniques that either preserve the original composition [

35] or alter it while maintaining the crystal structure [

28].

Our group pioneered the synthesis of cast HEAs using combined centrifugal casting and the SHS process [

36] and proposed creating catalytic versions by adding and subsequently leaching excess aluminum. In [

37], this precursor-leaching approach was applied to the preparation of catalysts using multicomponent SHS-derived intermetallic precursors. Through these works, we proved that the precursor phase composition is the key factor controlling the resulting catalyst activity and stability. In addition, the distribution of aluminum is important. In these catalyst precursors, aluminum serves as a sacrificial additive rather than a catalytically active component. Its removal generates the catalyst surface texture and porosity and permeability of particles. However, if removal is incomplete, the surface area is low; if it is too thorough, the catalyst loses mechanical strength and can disintegrate.

The catalytic properties of 3D metal-based HEAs can be significantly improved by introducing a wider array of components, notably Ce and La, which are known to exert a beneficial influence on the resulting material’s catalytic activity. Regarding CO oxidation, Co and Cu are recognized as active base metals [

38,

39]. Beyond Co and Cu, Mn, Fe, and Ni are also subjects of intensive study for their application in the deep oxidation of hydrocarbons [

40,

41,

42].

The efficacy of HEA-based catalysts in CO and propane deep oxidation, alongside CO

2 hydrogenation, was established in our previous study [

37]. The FeCoNiCuCr catalyst attained optimal deep oxidation performance, reaching 100% CO conversion at 250 °C and 100% propane conversion at 450 °C. Notably, the FeCoNiCuCr catalyst utilized in [

37] contained 4.24 wt % Cr, representing 50% of the chromium content present in the samples under investigation in the current study (see the text below). Furthermore, we observe a gap in the existing literature regarding HEA catalysts for the deep oxidation of CO and propane.

In this work, we aimed (i) to synthesize catalytically active FeCoNiCu-based HEAs with Cr, Mn, La, and Ce additives via a combined centrifugal casting–SHS process; (ii) to characterize their structure and phase composition; and (iii) to evaluate their catalytic properties after leaching.

2. Materials and Methods

A combined centrifugal casting and SHS process presents a highly cost-effective and efficient route for producing cast alloys compared with traditional melting techniques. Its economic advantage stems from using inexpensive oxide raw materials and its energy efficiency, as the process is driven entirely by the internal chemical energy of a self-sustaining, thermite-type combustion reaction. The method also ensures high product quality. The extreme synthesis temperatures (>2300 °C) lead to full homogenization of the alloy, while the applied centrifugal forces guarantee a complete metallothermic reduction and a clean separation of the molten alloy from oxide byproducts [

36,

43].

In this study, we examined five compositions: FeCoNiCuAl, FeCoNiCuCrAl, FeCoNiCuCrMnAl, FeCoNiCuCrLaAl, and FeCoNiCuCrCeAl (see

Table 1). SHS was performed using thermite-type mixtures containing metal oxide powders, Al as a reducing agent, and La chips (

Table 2).

The green mixture composition was determined using the following basic stoichiometric reactions:

The chemical synthesis reaction can be represented by the following general equation:

The powders were dried at 90 °C for 1 h, weighed stoichiometrically, and then mixed in a 5 L planetary mixer for 15–20 min. An amount of 1000 g of the resulting green mixture was poured into a pre-dried (at 90 °C for 1 h) refractory mold of 80 mm in diameter and 170 mm in height and subsequently compacted on a vibrating table. The mixture-filled mold was placed in the reaction chamber of the centrifugal SHS setup, the details of which were previously described in [

43]. The synthesis was conducted at atmospheric pressure. After setting the desired centrifugal acceleration (

g) via the rotor speed control system, the reaction was initiated by focusing a short-pulse laser onto the sample surface. The entire combustion process was recorded by a video-monitoring system mounted on the central part of the rotor.

In our studies [

43], the optimal range of centrifugal acceleration (overload) to produce HEAs was established as 30–55

g. The application of artificial gravity during synthesis suppresses the splashing of reactants and ensures intensive mixing of the high-temperature melt. This promotes high conversion within the combustion front. Subsequently, the high-

g conditions facilitate gravitational separation during cooling, which increases the metallic phase yield, removes gaseous byproducts, and ensures chemical homogeneity throughout the final ingot.

Following combustion, the molten alloy and slag, being mutually insoluble, were separated by centrifugal forces. This resulted in a two-layer ingot upon crystallization, with the target alloy forming the lower layer and the Al2O3 slag the upper layer.

In order to prepare catalysts, HEA ingots were crushed, and a 0.1–0.3 mm fraction was sieved out, leached with a 20% NaOH solution (spontaneous reaction for 1 h, boiling for 1 h, and holding at room temperature for 24 h; a tenfold excess of alkali relative to Al content in the sample was used), and washed with distilled water until neutral reaction. Then, the samples were stabilized in a 10% H2O2 solution (for 0.5 h) and washed again with distilled water. The stabilization process is essential for oxidizing surface hydrogen generated during leaching. This involves the catalytic decomposition of H2O2, which releases oxygen that adsorbs onto the surface, forming a protective layer to prevent further oxidation. After stabilization, the samples were dried at a temperature of 90 °C for 8 h.

Deep oxidation was performed in a laboratory-scale quartz flow reactor with a diameter of 8.5 mm at a gas hour space velocity (GHSV) of 120,000 h−1 in the temperature range of 150–400 °C. The catalyst loading was 1 cm3. During the experiment, the sample was continuously purged with a gas mixture. The appropriate value was set on the temperature controller, and when it was reached, the sample was kept for 15 min, and then the exhaust gas was supplied for analysis. The next temperature value was then set. The tested gaseous mixtures contained (vol %) 0.2 propane, 0.6 CO, and 2 O2, with N2 being the rest. The gas mixture’s composition was analyzed using an Avtotest 02.03P gas analyzer (META, Zhigulevsk, Russia).

The experimental results were processed as follows.

CO conversion in the oxidation reaction at temperature T was calculated using the following formula: XCO,T = [(CCO,0 − CCO,T)/CCO,0] · 100%, where CCO,0 is the initial concentration of CO in the gas mixture (vol %), and CCO,T is the concentration of CO in the reaction products at temperature T (vol %).

The propane conversion in the oxidation reaction at temperature T was calculated using the following formula: XC3H8,T = [(CC3H8,0 − CC3H8,T)/CC3H8,0]·100%, where CC3H8,0 is the initial concentration of propane in the gas mixture (vol %), and CC3H8,T is the concentration of propane in the reaction products at temperature T (vol %).

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out with a DRON-3 diffractometer with Fe Kα radiation (NPAO Nauchpribor, Orel, Russia). The XRD patterns were recorded in the step scanning mode in the range of angles 2θ from 30° to 120° with a 2θ step of 0.02°. The morphology and elemental composition of the surface were studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with a Zeiss Ultra plus instrument (Karl Zeiss, Jena, Germany,) equipped with an INCA Energy 350 XT energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK).

3. Results

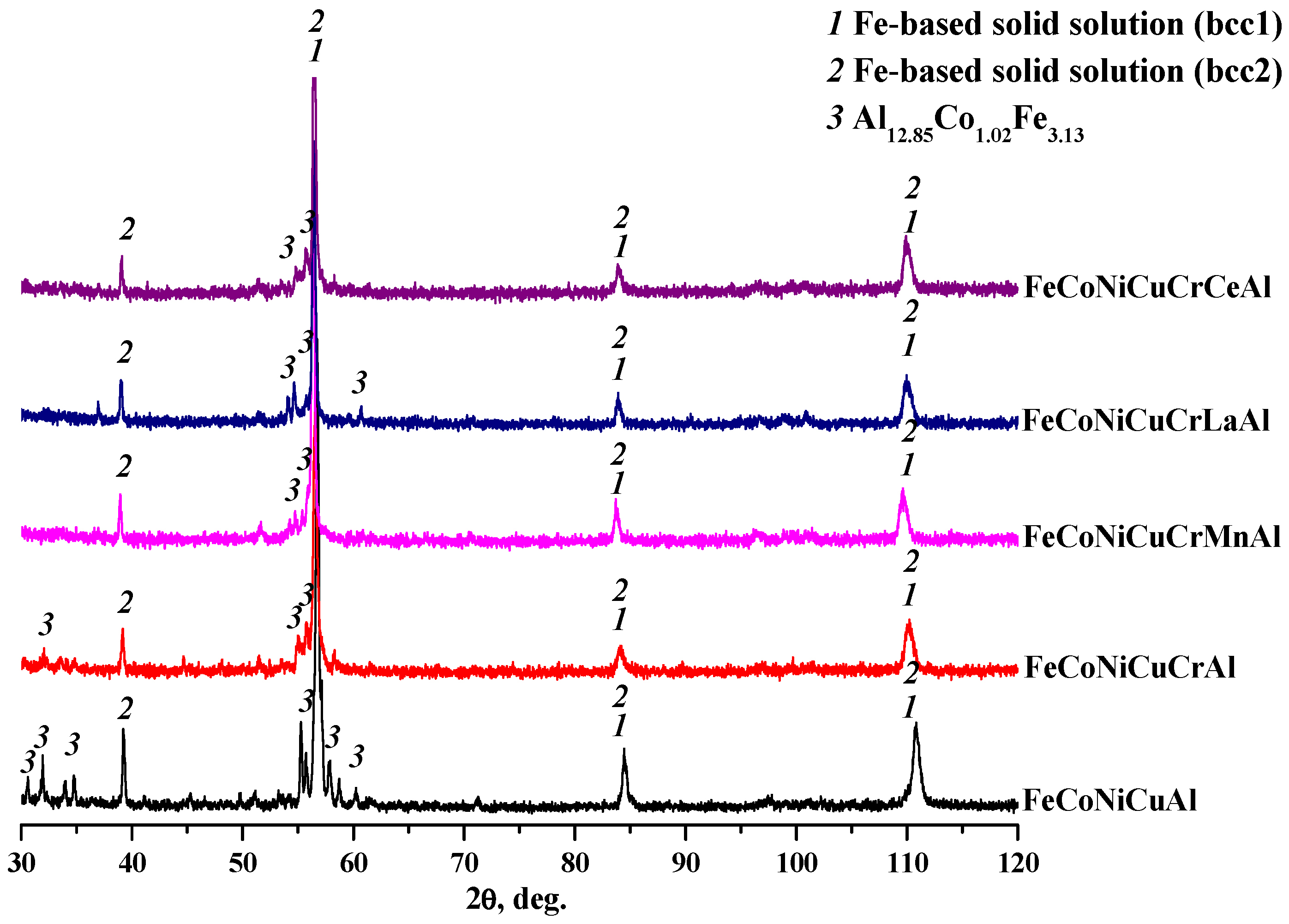

The XRD patterns presented in

Figure 1 indicate that all synthesized alloys, from the base FeCoNiCuAl to the doped variants, shared a similar phase composition. The alloys consisted primarily of two Fe-based solid solutions (lattice parameter

a = 2.886 Å for bcc1 and

a = 2.889 Å for bcc2) along with monoclinic aluminide (Al

12.85Co

1.02Fe

3.13) and trace metal aluminide impurities.

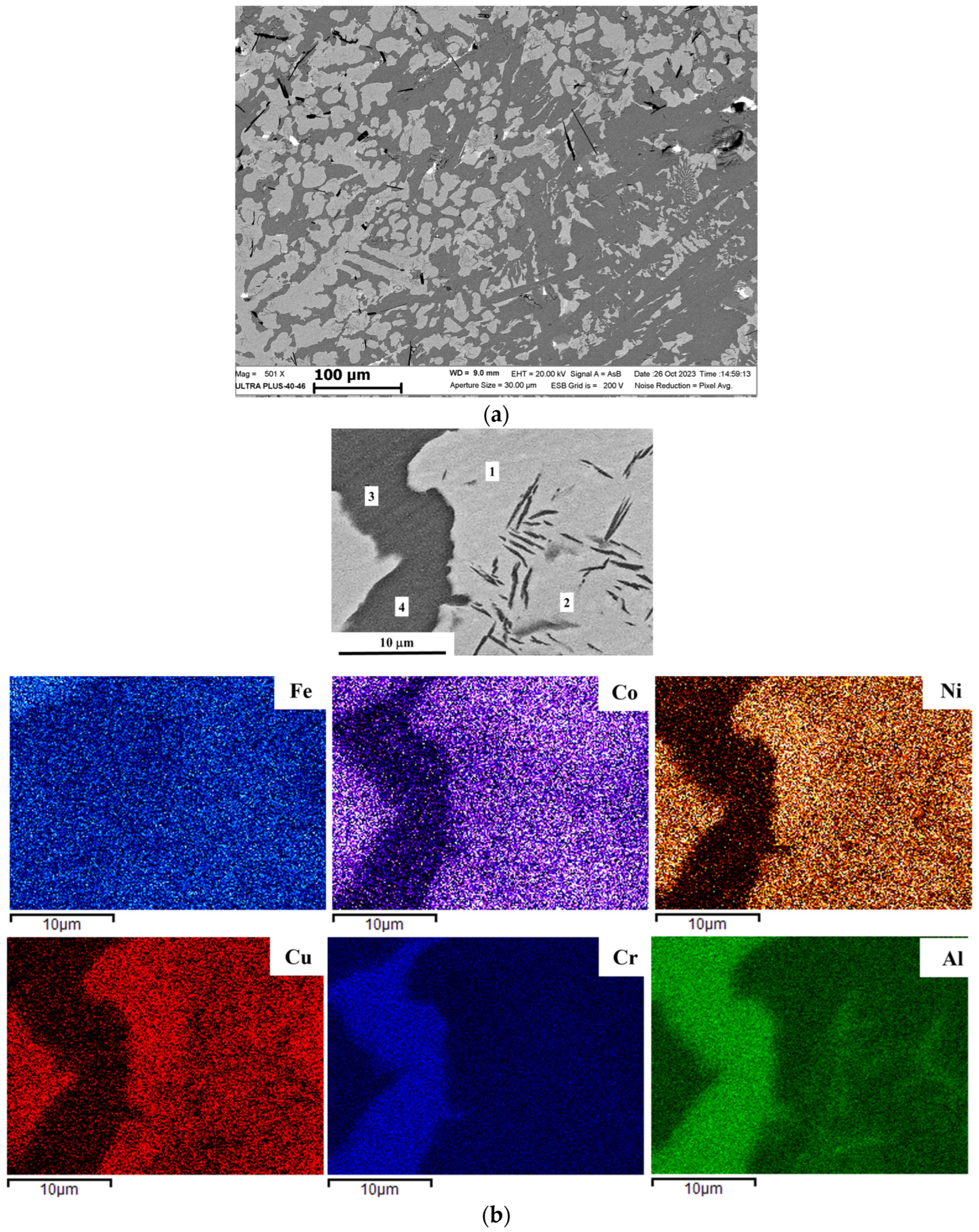

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 depict the SEM images and corresponding EDS maps for the synthesized alloys. As shown in

Figure 2 and supported by the data in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the undoped FeCoNiCuAl alloy possessed a two-phase microstructure. It was composed of a Ni–Cu-rich phase, which manifested as a mixture of globular grains and dendritic branches, embedded in an Fe–Al-rich continuous matrix. Co was found to be almost evenly distributed, with only 3 wt % depletion observed in the matrix. The presence of these two distinct phases was validated by the corresponding XRD data. The dendrites/grains were seen to contain randomly oriented thin, needle-like particles. Their precipitation was attributed to the formation of a solid solution that became supersaturated with Al, as shown in its EDS map in

Figure 2b, due to the extremely high temperatures (2200–2500 °C) inherent to the SHS process. The overall alloy composition was confirmed via EDS to be in good agreement with the nominal values (

Table 3).

Adding Cr resulted in large gas pores (~0.2–0.5 mm), as seen in

Figure 3a. This porosity was a consequence of a reduced combustion temperature, stemming from the lower exothermicity of the (Cr

2O

3 + Al) reduction reaction compared with the other oxides. Despite this structural feature, the material remains suitable for its intended use as a catalyst precursor. The microstructure of the FeCoNiCuCrAl alloy featured a semi-continuous network of coarse, irregularly shaped Ni–Cu-rich grains, which exhibited a rounded and elongated morphology, all set within a Cr–Al-rich matrix (

Figure 3 and

Table 5 and

Table 6). Intragranular needle-like particles were also present, as in the base alloy, but their volume fraction was significantly lower. Notably, Fe, Co, and Ni exhibited an uneven distribution and compositional variations within each phase.

The average alloy compositions measured in the three distinct pore-free regions of

Figure 3a are summarized in

Table 6. The minimal variation in the elemental content across these regions confirmed the absence of significant compositional inhomogeneities within the alloy.

Upon analysis of the Cr–Mn co-doped alloy’s overall elemental composition across the entirety of

Figure 4a, remarkable consistency with its calculated nominal values was observed (

Table 7). Moreover, its microstructure was found to be highly similar to that of the FeCoNiCuCrAl alloy (

Figure 4a). However, irregularly shaped grains were notably coarser (by a factor of ~1.5) and had a more globular morphology. A significant distinction was that these grains were monolithic, lacking the internal needle-like particles observed previously. As shown by EDS point and mapping analysis (

Table 8 and

Figure 4b, respectively), the sub-rounded grains enriched in Ni, Cu, and Co were surrounded by a Cr-, Mn-, and Al-containing matrix. Fe exhibited an even distribution across the alloy. The alloy was nearly fully dense; the porosity was negligible, with individual pores not exceeding 8 μm in diameter.

Addition of La to the FeCoNiCuCrAl alloy significantly refined its microstructure (

Figure 5a). As depicted in

Figure 5, the phase surrounded by a Cr–Al-rich matrix exhibited elevated Co, Ni, and Cu contents and presented a complex and varied morphology: (

i) coarse, rounded, or globular grains containing needle-like particles and (

ii) a fine, interconnected network forming a dendritic or eutectic structure (particularly evident on the right side). However, surface elemental analysis (

Figure 5 and

Table 9 and

Table 10) revealed a much lower La content than calculated (no more than 5 wt %;

Table 1). This discrepancy was likely due to La being introduced as metal shavings. Metallic La has a strong affinity for oxygen. During the high-temperature oxidation–reduction reactions in the combustion front, La, similar to Al, participates in the metallothermic reduction of other metal oxides, consequently migrating largely into the oxide (slag) phase.

The experimental results indicate that introducing La as a pure metal does not guarantee the formation of an alloy with the intended composition during SHS. For subsequent investigations, it is recommended to introduce La in the form of master alloys, such as Ni–La (30/70). La, in a bound state, is expected to react less vigorously with metal oxides.

The FeCoNiCuCrCeAl alloy produced by adding CeO2 to the green mixture exhibited a microstructure comparable to that of the Mn-containing alloy (

Figure 6 and

Table 11 and

Table 12 and

Figures S1–S4 in Supplementary Materials). According to the elemental composition (

Table 12), as with La, Ce was not detected here. Consequently, the concentrations of the other elements were higher than calculated. However, local elemental analysis at a specific point in

Figure 6b indicated that Ce formed intermetallic grains where its content was three times higher than calculated (points 7, 8, and 9 in

Table 12). These grains also contained approximately 43 wt % Al, 11.6 wt % Cr, and 24.4 wt % Cu, while being nearly devoid of Fe, Co, and Ni. This suggests that, much like with La, Ce was preferably incorporated into the HEA precursors through a master alloy. Furthermore, the micrograph (

Figure 6b) shows fiber-like precipitates consisting mainly of chromium aluminide. Their size did not allow for an accurate composition assessment.

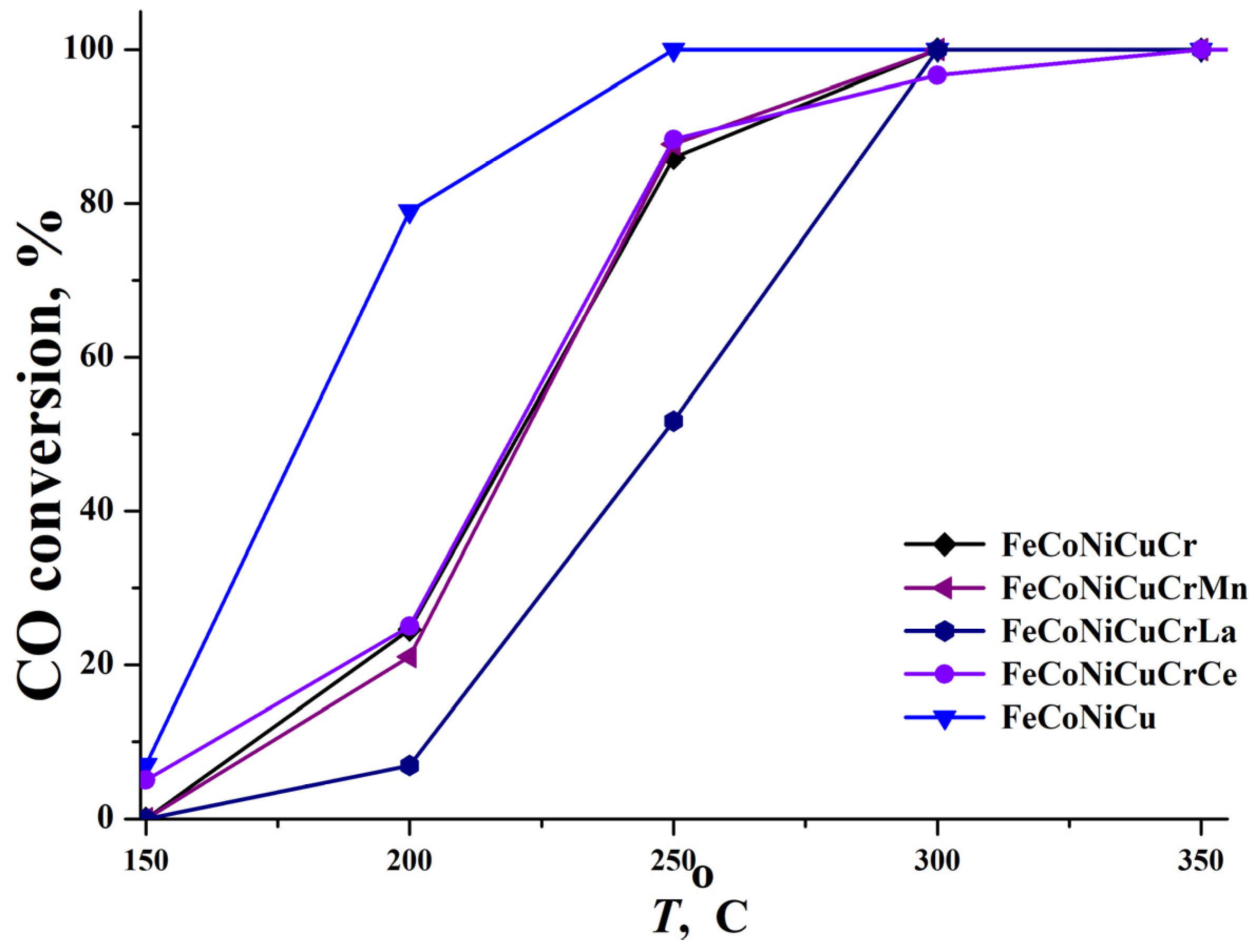

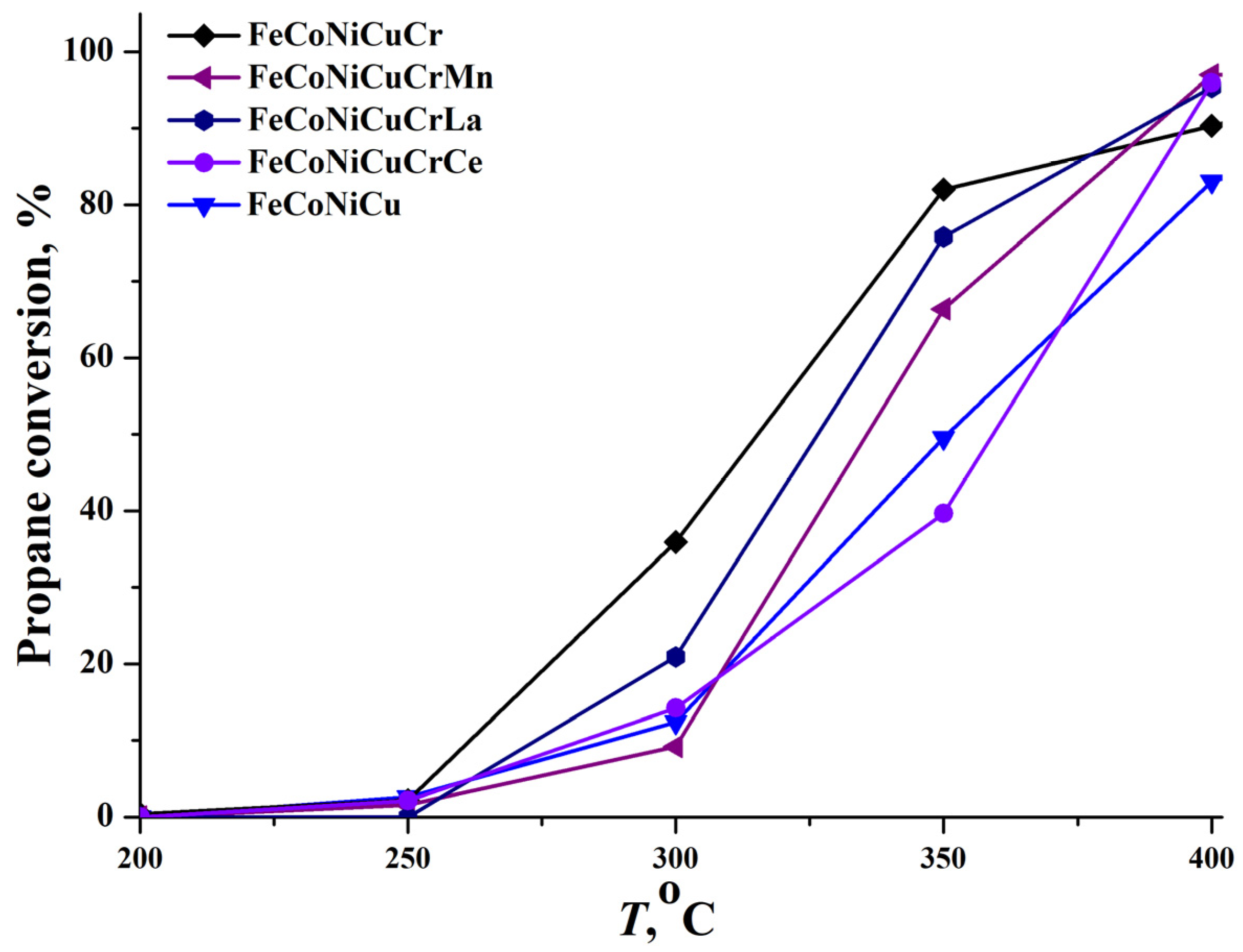

Five studied HEA precursors were converted into catalysts—FeCoNiCu, FeCoNiCuCr, FeCoNiCuCrMn, FeCoNiCuCrLa, and FeCoNiCuCrCe—for CO and propane deep oxidation through aluminum leaching and stabilization with a hydrogen peroxide solution. The results are presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 and

Table 13 (also

Figures S5–S9 in Supplementary Materials). For CO oxidation, the FeCoNiCu and FeCoNiCuCrCe catalysts became active above 100 °C, reaching 7 and 5% conversion at 150 °C, respectively (

Figure 7). All other catalysts commenced CO oxidation only after 150 °C. Notably, the FeCoNiCuCr, FeCoNiCuCrMn, and FeCoNiCuCrLa catalysts displayed similar levels of activity, reflected in their almost equal

T50 CO values (

Table 13). The FeCoNiCuCrLa sample, despite exhibiting rather low activity in the 150–250 °C range and a

T50 CO of 248 °C, ultimately reached 100% conversion at 300 °C, a performance mirrored by the FeCoNiCuCr and FeCoNiCuCrMn samples. Overall, the FeCoNiCu catalyst yielded the most favorable outcome for CO oxidation, achieving full (100%) CO conversion at 250 °C.

The propane conversion behavior across these catalysts showed marked temperature dependence variations. The FeCoNiCu catalyst, for instance, failed to achieve complete (100%) propane conversion within the experimental temperature range, reaching a maximum of 83% at 400 °C. Interestingly, despite significant differences in the T50 propane values, the conversion results became more similar as the temperature rose. The FeCoNiCuCrMn sample yielded the highest conversion at 400 °C, achieving 97%.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the influence of doping elements (Cr, Mn, La, and Ce) on the microstructural and phase evolution of FeCoNiCuAl-based high-entropy alloys synthesized via combined centrifugal casting and SHS, as well as their performance as catalysts after leaching. While all doped and undoped alloys exhibited a consistent phase composition (primarily two Fe-based solid solutions with minor aluminide phases), the dopants engendered pronounced alterations in microstructure, porosity, and elemental distribution.

The undoped FeCoNiCuAl alloy exhibited a two-phase microstructure with Ni–Cu-rich globular grains/dendritic branches, which contained thin, needle-like precipitates, within a Fe–Al-rich matrix. Cr doping (FeCoNiCuCrAl) introduced significant gas porosity due to lower combustion temperatures, but the material remained suitable for catalyst precursor use. The microstructure featured a Ni–Cu-rich grain network in a Cr–Al-rich matrix with a reduced volume fraction of internal needle-like particles. Fe, Co, and Ni showed uneven distributions and compositional variations within phases. Cr–Mn co-doping resulted in an analogous microstructure for the Cr-doped alloy, but with coarser, more globular, and monolithic Ni–Cu-rich grains that lacked internal needle-like particles. This alloy was nearly fully dense with negligible porosity, and Fe was evenly distributed. Introducing La as metal shavings significantly refined the microstructure, creating a complex morphology of Ni–Cu–Co-rich grains and a fine dendritic/eutectic network within a Cr–Al-rich matrix. However, introduced as metal shavings, La largely migrated to the oxide/slag phase, resulting in much lower detected surface content than the calculated one. This indicates a preference for La incorporation into the HEA through master alloys for better compositional control. Similar to La, Ce integration into the HEA matrix was inefficient; the FeCoNiCuCrCeAl’s microstructure was comparable to that of the Mn-containing alloy, with bulk Ce undetected.

Our work introduces, for the first time, the synthesis and characterization of HEA precursors designed for catalysts. These precursors feature an expanded active element composition, incorporating rare earth elements, and an exceptionally high aluminum content, reaching up to 50%, compositions entirely new to the existing literature. Notably, even with this elevated aluminum content, all precursors consistently maintained the bcc structure typical of HEAs. To develop catalysts with an increased specific surface area, a novel method is proposed: alkaline removal of excess aluminum, followed by surface stabilization of the highly dispersed active phase via hydrogen peroxide treatment.

It was found that catalysts leached from the FeCoNiCuAl precursor demonstrated superior performance in CO oxidation, achieving complete CO conversion at a lower temperature (250 °C), and in propane deep oxidation, higher conversion (up to 97%) was achieved on the FeCoNiCuCrMn catalyst.