Abstract

This study investigates the microstructural evolution, porosity characteristics, and mechanical behavior of LPBF-manufactured Scalmalloy®, which were investigated in the as-built conditions and after long-term exposure to direct aging of 275, 325, and 400 °C. Optical microscopy, and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analyses were employed to examine the grain morphology, pore distribution, and defect characteristics. In the as-built state, the microstructure displayed the typical fish-scale melt pool morphology with columnar grains in the melt pool centers and fine equiaxed grains along their boundaries, combined with a small number of gas pores and lack-of-fusion defects. After direct aging, coarsening of grains was revealed, accompanied by partial spheroidization of pores, though the global density remained above 99.7%, ensuring structural integrity. Grain orientation analyses revealed a reduction in crystallographic texture and local misorientation after direct aging, suggesting stress relaxation and a more homogeneous microstructure. The hardness distribution reflected this transition: in the as-built state, higher hardness values were found at melt pool edges, while coarser central grains exhibited lower hardness. After direct aging, the hardness differences between these regions decreased, and the average hardness increased from (104 ± 7) HV0.025 to (170 ± 10) HV0.025 due to precipitation of Al3(Sc,Zr) phases. Long-term aging studies confirmed the stability of mechanical performance at 325 °C, whereas aging at 400 °C induced overaging and hardness loss due to precipitate coarsening. Electrical conductivities increased monotonically at all tested temperatures from ~11.7 MS/m, highlighting the interplay between solute depletion and precipitate evolution.

1. Introduction

In several industrial sectors, such as aerospace and automotive, the performance of metal alloys depends on their density and microstructure. The use of lightweight alloys like aluminum or titanium contributes to weight reduction and can be optimized by structural design optimization of the component. The laser powder bed fusion process is able to fulfill both requirements. As a matter of fact, complex- and final-net-shaped structures can be achieved through a layer-by-layer manufacturing process exceeding the limits of the conventional manufacturing process. At the same time, the fine microstructure promoted by the rapid solidification rates confers high ultimate tensile strength and yield strength values [1].

State-of-the-art in laser powder bed fusion of aluminum mainly refers to AlSi12 [2,3], AlSi7Mg or AlSi10Mg [4] which satisfy a wide range of industrial applications due to their high specific strength and corrosion resistance. The hypoeutectic composition of AlSi7Mg and AlSi10Mg facilitates the laser-based manufacturing process due to the narrow solidification temperature range which lowers the percentage of shrinkage and the risk of cracking. Several studies [5,6,7,8] have demonstrated that direct aging heat treatments improved the tensile strength of these age-hardenable alloys. Conversely, the precipitation phenomena that occurred within the α-Al cells and the high amount of fine columnar grains lowered their ductility.

To overcome this problem together with the limited heat stability, Sc- and Zr-modified 5xxx alloy (Scalmalloy®) are successfully manufactured by laser powder bed fusion and used to replace the near-eutectic Al-Si-Mg alloys. In fact, the bi-modal microstructure of columnar and equiaxed grains (coarse and fine grains, respectively) conferred by the formation of the peritectic Al3Sc primary phase, enhances ductility also in the as-built conditions [9,10,11]. The L12-Al3Sc primary phases formed during the melt pool solidification serve as nucleation sites for the formation of fine equiaxed α-Al grains. Due to the same element additions, Al-Mg-Sc-Zr system can also be age-hardened by the formation of the uniformly dispersed Al3(ScxZr1−x) precipitates within the α-Al matrix [12,13,14]. Davydov et al. [15] have demonstrated that no crystallographic variations or loss of lattice coherence with the Al matrix were observed over a wide range of aging temperatures. As a matter of fact, diffusion of Zr atoms into Al3Sc precipitates can reduce their coarsening kinetics [16,17].

A recent review on the main heat-treatments applied on Scalmalloy® (Al-4.45Mg-0.7Sc-0.35Zr-0.65Mn) [11] summarized that exposure to 325 °C is the most effective to enhance strength during industrially sustainable treatment (2–5 h). At this temperature, several studies [13,18,19] concluded that the as-built yield strength increased from (270 ± 30) to (475 ± 25) MPa and ultimate tensile strength from (400 ± 50) to (530 ± 30) MPa. Li et al. [20] showed halved strength values of peak-aged Al-3.02Mg-0.2Sc-0.1Zr alloy by reducing Sc and Zr elements by one third with respect to Scalmalloy®. The Sc-dependent properties of the as-built samples due to the influence of the process parameters are investigated in [21]. High values of volume energy density (VED) extended the region of equiaxed grains due to the variations in thermal gradients [22,23,24]. The close relationship between thermal gradients and cooling rates implies a variation in Sc amount that diffuses within the α-Al lattice with the consequent influence on precipitation behavior.

Churyumov et al. [25] have investigated a novel Al-4.5Mg-0.32Sc-0.1Zr alloy in which optimum strength-ductility combination was obtained by a double aging heat treatment. These heat-treatment conditions improved sample’s ductility of 6% by maintaining high strength values (UTS of 478 MPa and YS of 435 MPa).

Mohebbi et al. [14] have demonstrated that direct aging at 400 °C/1 h promoted the formation of larger and more faceted coherent-Al3Sc precipitates than those investigated in as-built Scalmalloy® samples, as well as a more uniform distribution of Mg element. These microstructural features increased microhardness by approximately 50%. No evidence of discontinuous precipitation was reported by [14,26] during the exposure to 400 °C, unlike those reported in Al-0.2Sc alloy by [27].

Shen et al. [28] concluded that homogenization at 500 °C did not increase the solubility of alloying elements in Al lattice but increased precipitation kinetics of Sc- and Zr-contained precipitates. Additionally, grains underwent a recrystallization and coarsening phenomena. These conditions can be limited by the pinning effects of the intermetallic phases present at the grain boundaries.

This work aims to elucidate the behavior of LPBF Scalmalloy® exposed to different aging temperatures (275–400 °C) for long times by investigating its electrical conductivity (EC) and static mechanical properties. Furthermore, the characteristic microstructure of the alloy is presented and investigated through EBSD technique to provide a comprehensive microstructure characterization.

2. Materials and Methods

Scalmalloy® bars of 150 mm height (and base of 15 × 15 mm) were built from gas-atomized powders within a SLM®280 (SLM Solution, Lübeck, Germany) machine equipped with a IPG fiber laser. The gas-atomized powders, whose chemical composition is reported in Table 1, had diameters in the range 20–60 µm. The volume energy density used was 69.4 J/mm3 and the layer thickness was 30 µm. Other process parameters are proprietary. An Argon flux was employed inside the system to avoid oxidation considering that the oxygen content was maintained below 0.1%. The build platform was heated to 150 °C during the entire LPBF process to prevent deformation and to limit the degree of residual stress.

Table 1.

Nominal chemical composition (wt. %) of gas-atomized powder particles as supplied by manufacturer (Tekna®).

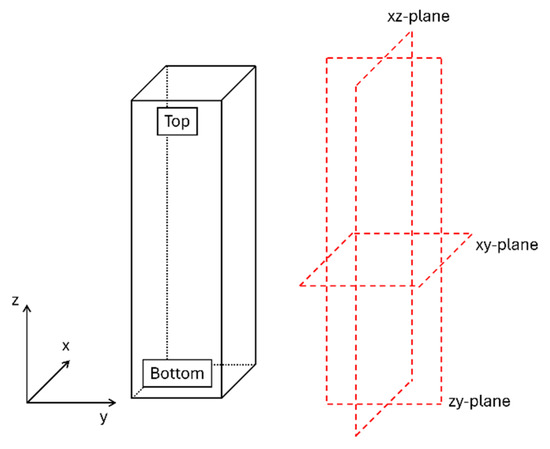

Several cube-shaped samples were cut from both the bottom region (closest to the heated platform, Figure 1) and the top region (farthest from the heated platform) to evaluate the possible effects of the build platform temperature on the microstructure, Vickers hardness, and EC along the bar height. The xz-, xy-, and zy-planes correspond to the planes on which measurements and investigations were performed.

Figure 1.

Schematization of LPBF-manufactured bars where “top” and “bottom” labels represent the position of plates on which microstructure was observed, and Vickers microhardness and EC were measured. The xz-, xy-, and zy-planes indicated the planes on which investigations were made.

Considering the high degree of isotropy between the top and the bottom regions, several plates (15 × 15 × 5 mm) were extracted from the as-built bar, regardless of the position, to evaluate the microstructure and to perform both Vickers microhardness and EC measurements after direct aging (DA) temperatures.

Post-process heat treatments were carried out in a muffle furnace (Nabertherm, Lilienthal, Germany) at 275 °C, 325 °C and 400 °C for soaking times between 5 min and 256 h. The exposure to 325 °C for 4 h was selected as reference condition (reference DA), according to both the aims of the paper and those discussed in the Section 1. In fact, the reference DA at 325 °C is that suggested by the manufacturer companies of LPBF machines.

The microstructure was investigated by a DMi8 optical microscope (OM, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an image analysis software (Las-X 5.3.1, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), along the coordinate planes (xz, zy, xy) in three-dimensional space (see Figure 1). Before the microstructural analysis, the samples were mechanically ground with SiC papers (from P80 to P4000), polished with silica colloidal suspension, and then chemically etched with Keller’s reagent.

For EBSD observations, the final surface finishing was carried out by ion milling (SEMPrep2 by TechnoorgLinda at 10 kV, 3.5 mA current for 15 min). EBSD maps were acquired with a Tescan Mira3 FE-SEM (TESCAN Group, Brno, Czech Republic) system equipped with EBSD probe Bruker Quantax EBSD System (Bruker Nano GmbH, Berlin, Germany) working at 20 KV, with an exposure time of 7 ms and a step size of 0.27 μm.

Pore analysis was conducted before and after exposure to reference DA on a population of at least 1500 objects identified in optical micrographs of polished and unetched samples, acquired at 100× and 1000× magnification. The analysis was performed on both xy- and xz-planes.

The ECs were measured on xy- and xz-planes of as-built and heat-treated samples in accordance with ASTM E1004 [29], using a calibrated SIGMATEST 2.070 instrument (Insitut Dr. Foerster GmbH & Co. KG, Reutling, Germany) operating at 60 kHz. The mean EC values were calculated from five measurements per condition.

Vickers microhardness was measured using a VMHT Leica microhardness tester (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a load of 500 gf and 15 s of dwell time, following the UNI EN ISO 6507-1:2018 standard [30]. Indentations were carried out on polished as-built and heat-treated samples on both xz- and xy-planes. Each microhardness value represents an average of 9 indentations. To investigate the contribution of the bimodal microstructure of Scalmalloy® to the microhardness, Vickers microhardness profiles were measured using a load of 25 gf.

3. Results and Discussion

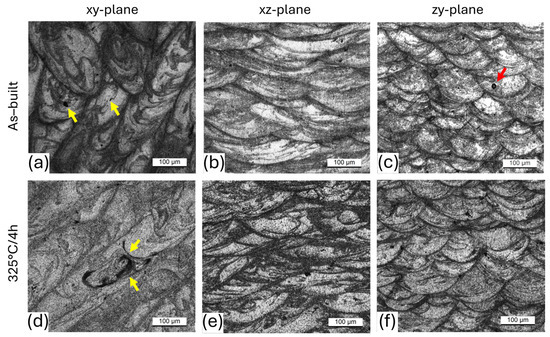

Figure 2 depicts the microstructures of LPBF-manufactured Scalmalloy® in as-built conditions (Figure 2a–c) and after the reference DA (Figure 2d–f). In the as-built (Figure 2a), laser scanning tracks (ellipsoidal-shaped in xy-plane) with a rotation angle of 67° are also visible, while coarsening phenomena of the microstructure in the aged samples is detectable in Figure 2d. The typical fish-scale molten pool morphology, resulting from the layer-by-layer LPBF manufacturing process, can be observed on both the xz-planes (Figure 2b,e) and zy-planes (Figure 2c,f), with an apparent coarsening of the finest microstructure features after the refence DA (Figure 2e,f). In addition, the yellow arrows in Figure 2a,c indicate the presence of defects that are supposed to be lack-of-fusion defects due to their irregular morphology [31]. Contrary, the red arrow in Figure 2c points a spherical-shaped gas pore.

Figure 2.

Low magnified OM micrographs of as-built bottom samples (a–c) and direct aged samples (d–f) at reference DA, acquired on xy-plane (a,d), xz-plane (b,e), and zy-plane (c,f). The yellow arrows indicate the lack-of-fusion pores (a,d), the red arrow points the spherical-shaped gas pore (c).

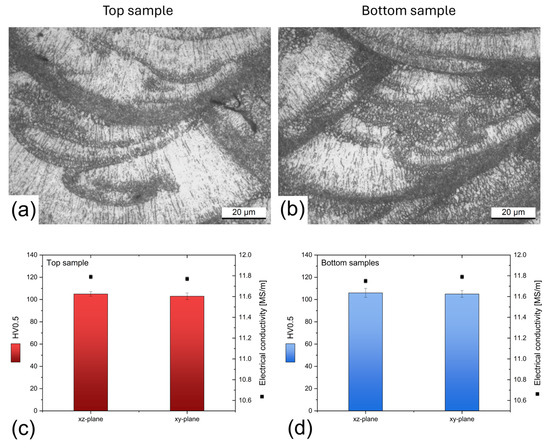

Figure 3 shows the microstructure of the as-built bar in both top (Figure 3a) and bottom (Figure 3b) regions, along with the Vickers microhardness and the EC measured on xz-plane and xy-plane. No microstructural differences were revealed at 1000× magnification. In both regions, columnar grains were visible within the melt pool centers, while fine equiaxed grains were present along the boundaries. This microstructural homogeneity is reflected in the Vickers microhardness and EC measurements shown in Figure 3c,d. Specifically, Vickers microhardness values remained constant at approximately (104 ± 2) HV0.5, while EC values were stable at (11.76 ± 0.02) MS/m between top (Figure 3c) and bottom (Figure 3d) samples. A similar degree of isotropy was confirmed by the measurements performed on xz-plane and xy-plane of both top and bottom samples.

Figure 3.

(a,b) OM micrographs of top (a) and bottom (b) samples. (c,d) Variations in both Vickers microhardness and EC values along both xz-plane and xy-plane in top (c) and bottom (d) samples.

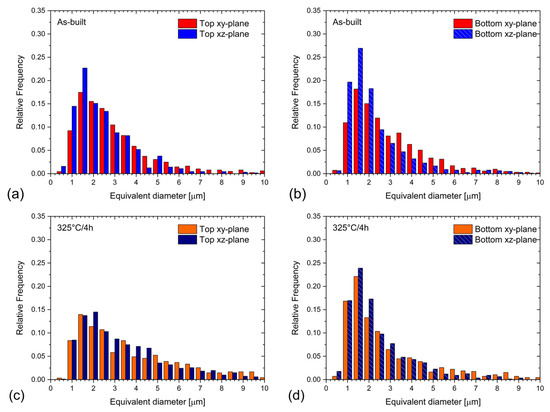

Figure 4 illustrates the statistical analysis of pore diameters in the as-built conditions (Figure 4a,b) and after exposure to reference DA (Figure 4c,d). The diameters were measured at the top (Figure 4a,c) and at the bottom (Figure 4b,d) regions and on the xy- and xz-planes, respectively. Values lower than 1 μm were excluded from statistical analysis due to the resolution of the optical microscope and the consequent ambiguity in pore identifying. A high degree of density homogeneity was exhibited by the as-built samples, both at the top (Figure 4a) and at the bottom (Figure 4b), on both investigated planes (xy and xz), as demonstrated by the similar pore distributions. As regards the samples DA at reference temperature and time (Figure 4c,d), the frequency of small pore diameters (<2 µm) has decreased, especially in the top sample probably because the analyzed sample was characterized by a better stability of melt pool during the LPBF process [32,33]. The mean pore equivalent diameters and standard deviations are reported in Table 2 where the density calculation was derived from the porosity measurements as the ratio between porosity and investigated area in each sample. From the pore’s analysis, the as-built top samples were characterized by a density of 99.66% on xy-plane and 99.93% on xz-plane, while the bottom samples by a density of 99.81% on xy-plane and 99.90% on xz-plane. After the exposure to the reference DA, the calculation of density gave, at the top, 99.75% on xy-plane and 99.82% on xz-plane, while in the bottom samples it gave 99.84% and 99.82% on xy-plane and xz-plane, respectively. For each density value, the associated errors are equal to 0.01%, which was calculated according to [34]. Table 2 shows that the densities, calculated as the average of densities between the xy- and xz-planes in each condition, remain similar before and after the exposure to reference DA.

Figure 4.

Distributions of pore’s diameter measured on xy-plane and xz-plane of each top and bottom samples in as-built (a,b) and DA (reference temperature and time, (c,d)) conditions.

Table 2.

Mean equivalent diameters and standard deviation of porosity in As-Built (AB) and Direct Aged (DA) samples.

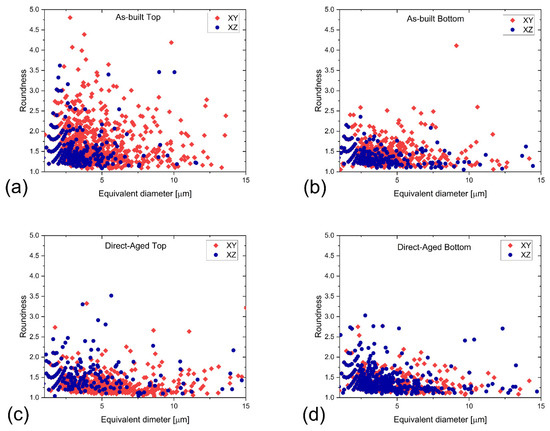

Another useful piece of information is the Roundness parameter (R) of the pores (Figure 4) (related to the manufacturing process) which is calculated as follows:

where A [µm2] is the single porosity area and P [µm] is the perimeter of the pore with area A. Figure 5 illustrates the roundness parameter as function of their equivalent diameter for top and bottom regions of as-built samples and those direct aged at reference temperature and time.

Figure 5.

Roundness parameter (R) versus equivalent diameter for as-built (a,b) top (a) and bottom (b) samples, and DA (c,d) at reference temperature and time for top (c) and bottom (d) samples.

Figure 5 (top as-built samples) can be considered as the porosity roundness distribution at the time t = 0 since the permanence of the top region on the manufacturing table preheated to 150 °C is very short (few minutes). In this case, the roundness parameter fluctuates between 1 and 5 over the pore equivalent diameter axis. In the bottom as-built sample (Figure 5b) and in the direct aged samples (top in Figure 5c and bottom in Figure 5d) the roundness parameter distributions are very similar with fluctuations between 1 and 2.5, regardless of the average equivalent diameters. The reduction in roundness (R), which means a tendency towards spheroidization of the porosities, is probably linked: to the low repeatably characterizing the LPBF process. The challenge is to understand how and if these porosities can or not influence the mechanical properties of the alloy. The fact that the distributions are similar on the xy-plane and xz-plane expresses an isotropy in the defects that can be considered non-negative, as well as the good density shown by the as-built and DA samples (Table 2). In this latter case, the absence of big pores (gas or especially lack-of-fusion) will not alter or influence the resistance and elongation of these high-quality samples [34,35].

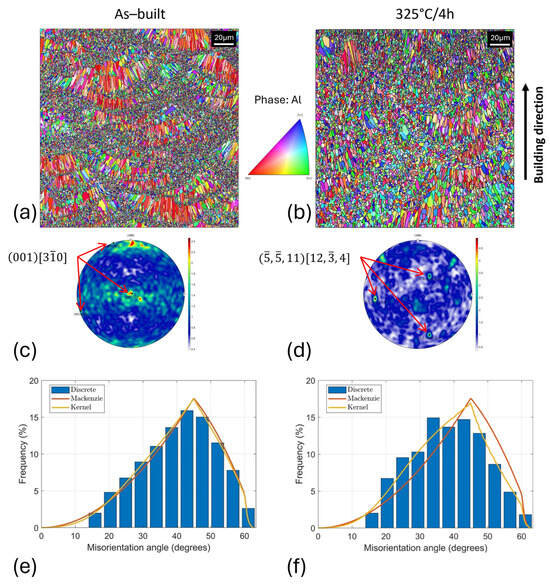

Figure 6 shows SEM-EBSD micrographs taken in the xz-plane of the as-built (Figure 6a,c,e) and DA (Figure 6b,d,f) samples. In Figure 6a, the as-built bimodal microstructure is observed, with fine grains surrounding coarse elongated grains in the xz-plane, generally disposed along the melt pool boundaries. Figure 6b depicts coarser and more massive grains than in the as-built samples. Moreover, in Figure 6a the columnar grains mainly have a <001> orientation approximately parallel to the Building direction (z-axis) [36]; in Figure 6b columnar grains show a more random orientation. The different orientation of the grain in as-built and DA samples is confirmed by the inverse polar figure (IPF) maps (Figure 6c,d).

Figure 6.

Microstructures and local orientations for the as-built (a,c,e) and DA (b,d,f) at reference temperature and time samples: (a,b) EBSD microstructures, (c,d) [001] pole figures, (e,f) frequency of misorientation angles.

Concerning the local grain misorientations, the measurements (Figure 6e,f) show that after reference DA, the misorientation frequency shift to lower angles compared to the as-built sample. The population of grains with a misorientation angle < 35° has increased statistically of 10% at least after aging.

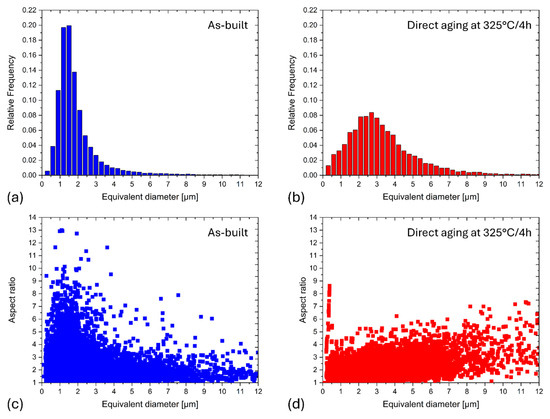

The exposure to reference DA caused modification in the grain size and aspect ratio. The mean equivalent diameter of grains increased from (1.8 ± 1.6) µm in the as-built (Figure 7a) to (3.3 ± 2.3) µm in the DA sample (Figure 7b), as illustrated by the shift in relative frequency distributions towards larger grain sizes. The exposure to reference temperature also affected the grain aspect ratio compared to the as-built conditions. As shown in Figure 7c, the as-built sample exhibits high aspect ratio values, reaching up to 10 especially for fine grains with equivalent diameter < 3 µm. After aging, the aspect ratio does not exceed the value of 5 (Figure 7b) regardless of grain dimension, except for very few grains (smaller than 0.25 µm). This phenomenon results in a microstructure characterized by fewer elongated grains and a higher proportion of equiaxed ones, leading to the disappearance of the bimodal microstructure. The reduction or loss of the bimodal microstructure may lead to a decrease in ductility, because of the loss of the original microstructure’s heterogeneity (elongated and equiaxed grains) producing different deformation zones that contributed to enhance the ductility of the material [37].

Figure 7.

Total grain size distributions (a,b) and aspect ratio distributions (c,d) of as-built (a,c) and reference DA (b,d) samples.

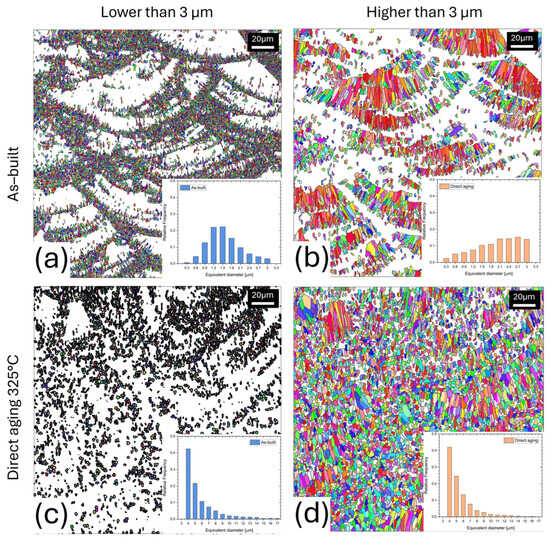

For a more in depth analysis of fine and coarse grain growth, the population was divided into two subsets: fine grains (with equivalent diameters smaller than 3 µm) and coarse grains (with diameters greater than 3 µm), for both the as-built and direct aged samples (Figure 8). EBSD images of the two different populations are shown in Figure 8a,b for the as-built sample and in Figure 8c,d for the direct aged ones, together with their frequency distributions. The results show that the population of fine grains increases its mean diameter of 30% after exposure to reference DA (from 1.43 ± 0.56 to 1.85 ± 0.74 µm), while the population of coarse grains show only a slight change (from 5.35 ± 3.01 to 4.95 ± 2.44 µm) within the standard deviation and with stable relative frequency distributions.

Figure 8.

EBSD images of fine (a,c) and coarse (b,d) grains in the as-built sample (a,c) and after exposure to reference DA (b,d). Each panel shows the distributions of the equivalent diameters.

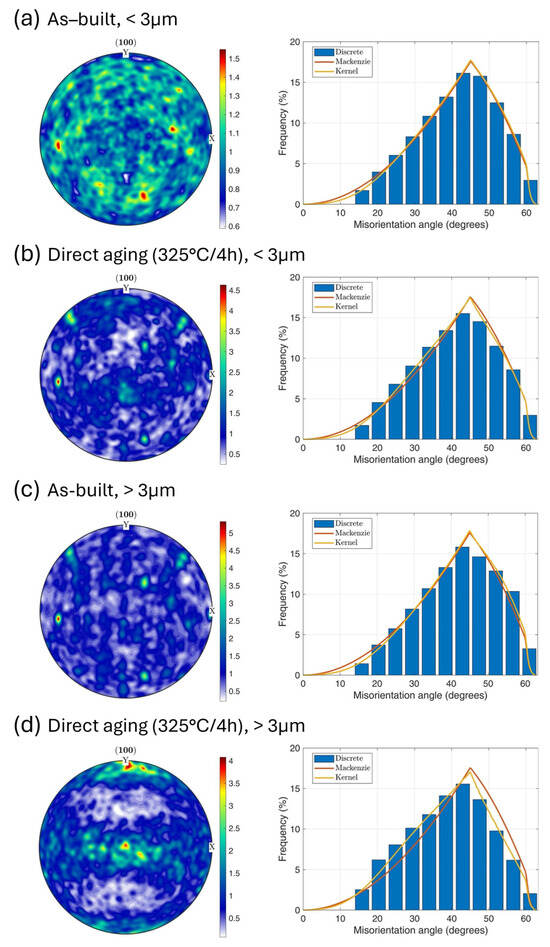

For the EBSD analysis of fine and coarse grains too, it is used misorientation angles and polar figures which are illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Polar figures and frequency distributions of misorientation angles of fine (a,c) and coarse (b,d) grains in both as-built samples (a,b) and those of DA at reference temperature and time (c,d).

Based on the Pole Figures (PF) shown in Figure 9, a clear qualitative difference can be observed between grains smaller and larger than 3 μm. Below this threshold, the grains tend to align along a specific preferential orientation, as highlighted by the peaks in the orientation distribution function, which reach values of 1.5 in Figure 9a and 3 in Figure 9b. Conversely, in Figure 9c,d, the onset of a crystallographic fiber can be noticed, as the orientations tend to cluster around an almost constant zenith angle.

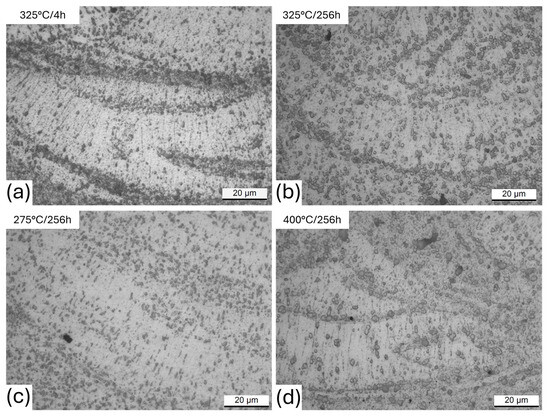

Figure 10a shows the OM micrograph of Scalmalloy® after exposure at 325 °C for 4 h. As discussed through EBSD analysis, the bimodal microstructure (fine-grain and coarse-grain zones) undergoes coarsening phenomena compared with the as-built alloy (Figure 3a,b). The corroded areas, which can be associated with the equiaxed grains of the fine-grain zone, exhibit a coarser morphology. This effect becomes more pronounced with prolonged exposure up to 325 °C for 256 h (Figure 10b). In this condition, larger equiaxed grains are also present within the coarse zone of the melt pool. The exposure to 275 °C/256 h did not confer significant grain coarsening (Figure 10c). Finally, exposure at 400 °C for 256 h, shown in Figure 10d, reveals coarsened regions that do not differ significantly from those observed in Figure 10b.

Figure 10.

OM micrographs of Scalmalloy® microstructures DA at: (a) 325 °C/4 h, (b) 325 °C/256 h, (c) 275 °C/256 h, (d) 400 °C/256 h.

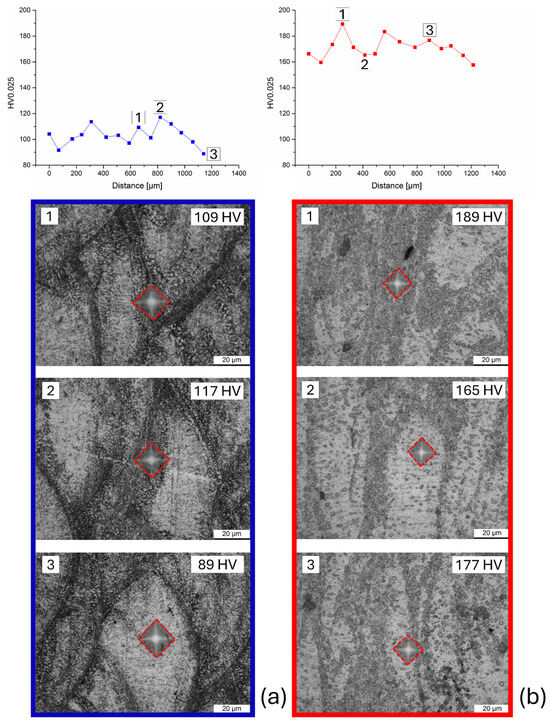

To assess local mechanical properties, Vickers microhardness measurements were performed on the xz-plane of the as-built samples and of bars before the exposure to the reference DA, using a load of 25 gf. As expected, the hardness values of the aged samples are higher than that of as-built ones, due to precipitation strengthening phenomena. Nevertheless, the minimum (and maximum) values in the two hardness profiles correspond to areas of similar grain morphology, as illustrated in Figure 11. In particular, the lowest Vickers microhardness values were always measured in the center of the molten pool where coarse elongated grains are usually present (point 3 in Figure 11a and point 2 in Figure 11b), while the highest microhardness values are measured at the edge of the molten pool and are characterized by fine grains (point 2 in Figure 11a and point 1 in Figure 11b). This difference in hardness was primarily conferred by grain size variations (Figure 7). In fact, hardness decreased from finer to coarser grains. In addition, based on EBSD analyses, the border regions of the melt pool may exhibit a higher amount of dislocation density [38]. Finally, it may also be observed that the higher hardness of fine grain zone is associated with a greater amount of primary Al3Sc particles, as extensively investigated in [39]. These primary particles act as nucleating agents, promoting the formation of the fine grain zone. Moreover, the hardness gaps between fine and coarse regions are +30% in the as-built conditions and +15% in the DA samples, respectively, taking as reference the hardness of the coarsest zones (average of the lowest points). Accordingly, the application of the reference DA reduces the hardness gap initially present in the as-built between the edges and the central zones of the melting pools due to the grain growth as observed in Figure 6, even if precipitation phenomena are active. The average Vickers microhardness values along the 1200 mm are (104 ± 7) HV0.025 in the as-built conditions and (170 ± 10) HV0.025 in the DA samples. This increment in the Vickers microhardness was surely conferred by the precipitation of small Al3(Sc,Zr) phases, as widely discussed in [11,40].

Figure 11.

Vickers microhardness profiles obtained along the build direction (xz-plane) for both the as-built (a) and DA (b) samples. OM micrographs (1–3) contained in the blue and red squares underline the correlation between the Vickers imprints and the microstructure morphology.

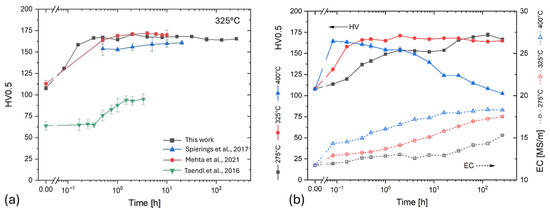

Long term aging curves are presented in Figure 12. Figure 12a shows the aging curves at 325 °C of samples analyzed in the present work, alongside data reported in [26,41,42]. The graphs show that, even though the LPBF manufacturing conditions were different in terms of fabricating device, but comparable in process parameters, the aging curves at 325 °C show similar trends, with the exception of the as cast alloy which displays different behavior due to its different microstructure. For the LPBF-manufactured Scalmalloy®, the Vickers microhardness stability may be conferred by: (i) limited grain coarsening phenomena (Figure 10), due to Al3(Sc,Zr) particles that act as pinning points, (ii) the absence of formation of other precipitates after 1–2 h of exposure to 325 °C, as demonstrated in [42], and (iii) the slight tendency of Al3(Sc,Zr) precipitates to become coarse at the reference temperature [43]. Future work will be focused on these microstructural aspects.

Figure 12.

(a) Aging curves of Scalmalloy® direct aged at 325 °C and compared to those obtained by [26,41,42]. (b) Comparison between aging curves and EC values of Scalmalloy® aged at 275, 325, and 400 °C. The Brinell hardness values of [26] were converted in Vickers microhardness by using the conversion equations discussed in [44]. (Adapted from Refs. [26,41,42,44]).

Figure 12b illustrates aging profiles and EC measured after exposure to the reference temperature of 325 °C, as well as the effects of varying the temperatures to 275 and 400 °C. During aging at 275 °C, hardness linearly increases from (106 ± 4) HV0.5 to peak-aged condition (172 ± 2) HV0.5 after 128 h due to slower precipitation kinetics than those that are triggered by the refence DA [45]. When direct aging temperature is performed at 325 °C, peak-aging moved to shorter times (2 h) due to accelerated precipitation kinetics of the Al3(Sc,Zr) phases. After peak-aging, the hardness remained stable between 165 and 171 HV0.50, therefore confirming the high-temperature stability of Scalmalloy®, as previously discussed. For aging at 400 °C, the peak hardness of (165 ± 2) HV0.5 is reached after 5 min soaking time, followed by a monotonic decrease to (100 ± 2) HV0.5 after 256 h aging, due the Al3(Sc,Zr) precipitate coarsening and grain growth [28]. Figure 12b also shows the EC evolution during aging time up to 256 h. The EC continuously increases with time at 275 °C from the as-built value of (11.74 ± 0.01) MS/m to (15.28 ± 0.01) MS/m. During DA at 325 °C EC reaches the value of (17.51 ± 0.01) MS/m and at 400 °C it increases to (18.28 ± 0.01) MS/m. The increase in EC during aging results from different concurrent phenomena. At the beginning of aging, the decomposition of the supersaturated solid solution of the as-built samples into precipitates surely increases the EC values, with different kinetics depending on the aging temperature. In conventional precipitation-hardened aluminum alloys produced by rolling or extrusion, a decrease in Vickers microhardness (overaging) usually corresponds to an increase in EC. In LPBF-produced Scalmalloy®, this correlation is observed only during aging at 400 °C. At 275 °C and 325° C, EC always increases even when the Vickers microhardness remains constant or increases. During the exposure to 275 °C, the monotonic increment in EC values may be related to the continuous depletion of alloying elements from the Al crystal lattice. During the exposure at 325 °C, the EC increase may be related to the possible variation in precipitates morphology and in the mismatch between Al matrix and the precipitate lattice [43]. At 400 °C, the increment in EC is probably further promoted by precipitate coarsening phenomena [43,46].

4. Conclusions

The microstructural characterization and Vickers microhardness variations in LPBF-manufactured Scalmalloy® in as-built and direct-aged (DA) conditions provide the following conclusions:

- As-built Scalmalloy® shows a bimodal microstructure composed of fine equiaxed and coarse columnar grains arranged in a layered melt pool architecture. After DA at 325 °C/4 h, clear grain coarsening occurs. EBSD analysis confirmed an increase in mean grain size from ~1.8 µm to ~3.3 µm, accompanied by a reduction in grain aspect ratio Fine grains coarsen by ~30% after DA, while coarse grains remain essentially unchanged.

- Aging reduced the overall crystallographic texture, with columnar grains adopting more random orientations, and increased the fraction of grains with misorientation angles below 35°, indicating lower internal strain and a more uniform grain orientation.

- No significant differences were observed between top and bottom regions or between xy- and xz-planes for hardness, conductivity, porosity, or grain structure, confirming the high isotropy of LPBF-manufactured Scalmalloy®.

- Both as-built and DA conditions exhibited very high relative densities (>99.7%) with isotropic pore distributions. No large lack-of-fusion or gas pores detected, meaning porosity is not expected to limit mechanical performance.

- Vickers microhardness mapping showed higher values at fine-grained melt pool edges compared to coarse-grained centers. After DA, this gap decreased due to grain homogenization. Overall hardness increased from (104 ± 7) HV0.025 in the as-built condition to (170 ± 10) HV0.025 after DA, mainly due to precipitation of Al3(Sc,Zr) particles.

- Aging at 325 °C led to rapid peak-aging within 2 h, with hardness stability maintained up to 256 h, demonstrating excellent thermal stability of the strengthening precipitates. At 275 °C, slower precipitation kinetics were observed, while 400 °C caused rapid hardening followed by overaging likely due to precipitate coarsening and grain growth. Electrical conductivity increased continuously with temperature and exposure time, reflecting solute depletion and precipitate evolution.

The direct aging at 325 °C for 2 h provides an optimal balance of mechanical strength, suggesting that the standard heat treatment of 325 °C for 4 h could be effectively replaced by a shorter 2 h process. This adjustment has the potential to reduce processing costs and furnace time, thereby enhancing industrial productivity. Regarding electrical conductivity, which is critical for high-performance electrical and electronic components such as lightweight enclosures, connectors, and heat sinks in aerospace, automotive, and electronic industries, the 2 h aging treatment yields a conductivity (14.13 ± 0.01 MS/m) comparable to that of the 4 h process (14.67 ± 0.01 MS/m). This indicates that the shorter heat treatment does not compromise electrical performance, offering a more efficient processing route.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G., E.C. and A.M.; software, D.C., E.G. and L.C.; validation, D.C. and L.C.; formal analysis, E.G., D.C. and L.C.; investigation, D.C. and L.C.; resources, E.G., A.M. and E.C.; data curation, E.G., D.C. and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C., E.C., A.M. and D.C.; writing—review and editing, E.G., E.C., A.M. and D.C.; visualization, E.G., D.C. and L.C.; supervision, E.G. and A.M.; project administration, E.G., A.M., E.C. and D.C.; funding acquisition, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was granted by the University of Parma through the action Bando di Ateneo 2025 per la ricerca, co-founded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investement 1.5.—Call for tender No. 3277 of December 2021 of the Italian Ministry of University and Research founded by European Union-NextGenerationEU.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leary, M. Design for Additive Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9780128167212. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, A.; Miyasaka, T.; Takata, N.; Kobashi, M.; Kato, M. Control of Microstructural Characteristics and Mechanical Properties of AlSi12 Alloy by Processing Conditions of Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheysen, J.; Marteleur, M.; van der Rest, C.; Simar, A. Efficient Optimization Methodology for Laser Powder Bed Fusion Parameters to Manufacture Dense and Mechanically Sound Parts Validated on AlSi12 Alloy. Mater. Des. 2021, 199, 109433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, R.; Coduri, M.; Checchia, S.; Vedani, M. Insight into the Effect of Different Thermal Treatment Routes on the Microstructure of AlSi7Mg Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Mater. Charact. 2021, 172, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Egidio, G.; Ceschini, L.; Morri, A.; Martini, C.; Merlin, M. A Novel T6 Rapid Heat Treatment for AlSi10Mg Alloy Produced by Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion: Comparison with T5 and Conventional T6 Heat Treatments. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2022, 53, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, E.; Ghio, E. Change in Mechanical Properties of Laser Powder Bed Fused AlSi7Mg Alloy during Long-Term Exposure at Warm Operating Temperatures. Materials 2023, 16, 7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.P.; Wang, X.J.; Saunders, M.; Suvorova, A.; Zhang, L.C.; Liu, Y.J.; Fang, M.H.; Huang, Z.H.; Sercombe, T.B. A Selective Laser Melting and Solution Heat Treatment Refined Al–12Si Alloy with a Controllable Ultrafine Eutectic Microstructure and 25% Tensile Ductility. Acta Mater. 2015, 95, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeshima, T.; Oh-ishi, K.; Kadoura, H. Microstructural Evolution and Hardening Phenomenon Caused by Aging of AlSi10Mg Alloy by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røyset, J.; Ryum, N. Scandium in Aluminium Alloys. Int. Mater. Rev. 2005, 50, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, V.G.; Rostova, T.D.; Zakharov, V.V.; Filatov, Y.A.; Yelagin, V.I. Scientific Principles of Making an Alloying Addition of Scandium to Aluminium Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 280, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, E.; Curti, L.; Ghio, E. Main Heat Treatments Currently Applied on Laser Powder Bed-Fused Scalmalloy®: A Review. Crystals 2024, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ren, X. A Systematic Study of Interface Properties for L12-Al3Sc/Al Based on the First-Principles Calculation. Results Phys. 2020, 19, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Chen, Z.; Lu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Le, W.; Naseem, S. Nucleation and Growth of Al3Sc Precipitates during Isothermal Aging of Al-0.55 Wt% Sc Alloy. Mater. Charact. 2021, 179, 111331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, M.S.; Nagy, S.; Hájovská, Z.; Nosko, M.; Ploshikhin, V. Understanding Precipitation during In-Situ and Post-Heat Treatments of Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloys Processed by Powder-Bed Fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 90, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, V.G.; Elagin, V.I.; Zakharov, V.V.; Rostoval, D. Alloying Aluminum Alloys with Scandium and Zirconium Additives. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 1996, 38, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, E.A.; Seidman, D.N. Coarsening Kinetics of Nanoscale Al3Sc Precipitates in an Al–Mg–Sc Alloy. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 4259–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.B.; Seidman, D.N.; Dunand, D.C. Mechanical Properties of Al(Sc,Zr) Alloys at Ambient and Elevated Temperatures. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 4803–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, A.; Aversa, A.; Manfredi, D.; Bondioli, F.; Biamino, S.; Ugues, D.; Lombardi, M.; Fino, P. Low-Power Laser Powder Bed Fusion Processing of Scalmalloy®. Materials 2022, 15, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierings, A.B.; Dawson, K.; Dumitraschkewitz, P.; Pogatscher, S.; Wegener, K. Microstructure Characterization of SLM-Processed Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloy in the Heat Treated and HIPed Condition. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 20, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, H.; Zhu, H.; Wang, M.; Chen, C.; Yuan, T. Effect of Aging Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al-3.02Mg-0.2Sc-0.1Zr Alloy Printed by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Des. 2019, 168, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumy, D.; Kan, W.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, A. The Latest Development of Sc-Strengthened Aluminum Alloys by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 149, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.V.; Shi, Y.; Palm, F.; Wu, X.; Rometsch, P. Columnar to Equiaxed Transition in Al-Mg(-Sc)-Zr Alloys Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Scr. Mater. 2018, 145, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, D. Parametric Analysis of Thermal Behavior during Selective Laser Melting Additive Manufacturing of Aluminum Alloy Powder. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Rometsch, P.; Yang, K.; Palm, F.; Wu, X. Characterisation of a Novel Sc and Zr Modified Al–Mg Alloy Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Lett. 2017, 196, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churyumov, A.Y.; Pozdniakov, A.V.; Prosviryakov, A.S.; Loginova, I.S.; Daubarayte, D.K.; Ryabov, D.K.; Korolev, V.A.; Solonin, A.N.; Pavlov, M.D.; Valchuk, S. V Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a Novel Selective Laser Melted Al–Mg Alloy with Low Sc Content. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 126595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierings, A.B.; Dawson, K.; Kern, K.; Palm, F.; Wegener, K. SLM-Processed Sc- and Zr- Modified Al-Mg Alloy: Mechanical Properties and Microstructural Effects of Heat Treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 701, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røyset, J.; Ryum, N. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Precipitation in an Al–0.2wt.% Sc Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 396, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.F.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Wang, C.G.; Wu, H.F.; Yang, Q.; Wang, G.W.; Huang, S.K. Effect of Heat Treatments on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloy Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 143, 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E1004; Standard Test Method for Determining Electrical Conductivity Using the Electromagnetic (Eddy-Current) Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- UNI EN ISO 6507-1:2018; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Nudelis, N.; Mayr, P. A Novel Classification Method for Pores in Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2021, 11, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Understanding Melt Pool Characteristics in Laser Powder Bed Fusion: An Overview of Single- and Multi-Track Melt Pools for Process Optimization. Adv. Powder Mater. 2023, 2, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, P.A.; Sivo, A.; Calignano, F.; Bassini, E.; Biamino, S.; Ugues, D. Parameters Optimization and Repeatability Study on Low-Weldable Nickel-Based Superalloy René 80 Processed via Laser Powder–Bed Fusion (L-PBF). Metals 2023, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, E.; Ghio, E.; Bolelli, G. Defect-Correlated Vickers Microhardness of Al-Si-Mg Alloy Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Post-Process Heat Treatments. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 8047–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, E.; Ghio, E. Metallurgical Analysis of Laser Powder Bed-Fused Al–Si–Mg Alloys: Main Causes of Premature Failure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 881, 145402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, S.I.; González-Rovira, L.; Cabrera-Correa, L.; de Dios López-Castro, J.; Castillo-Rodríguez, M.; Botana, F.J.; Haghshenas, M. Insights into Laser Powder Bed Fused Scalmalloy®: Investigating the Correlation between Micromechanical and Macroscale Properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 4409–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimbäck, D.; Kaserer, L.; Mair, P.; Palm, F.; Leichtfried, G.; Pogatscher, S.; Hohenwarter, A. Deformation and Fatigue Behaviour of Additively Manufactured Scalmalloy® with Bimodal Microstructure. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 172, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, K.; Jarzębska, A.; Wójcik, A.; Garbacz-Klempka, A.; Piekło, J.; Terlicka, S.; Piękoś, M.; Sobczak, J.J.; Krasa, O.; Krawczyk, Ł. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Scalmalloy® Produced by Selective Laser Melting in Term of Long-Term Applications. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2025, 25, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gu, D.; Yang, J.; Dai, D.; Zhao, T.; Hong, C.; Gasser, A.; Poprawe, R. Selective Laser Melting of Rare Earth Element Sc Modified Aluminum Alloy: Thermodynamics of Precipitation Behavior and Its Influence on Mechanical Properties. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rovira, L.; Cabrera-Correa, L.; de Dios López-Castro, J.; Ojeda-López, A.; Botana, F.J. AlMgScZr Alloys for Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. A Review. Mater. Des. 2025, 254, 114080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, B.; Svanberg, A.; Nyborg, L. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of an Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloy: Manufacturing, Peak Hardening Response and Thermal Stability at Peak Hardness. Metals 2021, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taendl, J.; Orthacker, A.; Amenitsch, H.; Kothleitner, G.; Poletti, C. Influence of the Degree of Scandium Supersaturation on the Precipitation Kinetics of Rapidly Solidified Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloys. Acta Mater. 2016, 117, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, E.A.; Seidman, D.N. Nanoscale Structural Evolution of Al3Sc Precipitates in Al(Sc) Alloys. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, E.; Ghio, E. AlSi10Mg Alloy Produced by Selective Laser Melting: Relationships between Vickers Microhardness, Rockwell Hardness and Mechanical Properties. Metall. Ital. 2020, 112, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Puybras, M.; Massardier, V.; Fabregue, D.; Perez, M.; Dorin, T. Influence of Sc and Zr on Mg Precipitation and Sensitization Resistance in Al-Mg-(Sc-Zr) Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1021, 179555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taendl, J.; Poletti, C. Influence of Al3(Sc,Zr) Precipitates on Deformability and Friction Stir Welding Behavior of Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloys. BHM Berg-Und Hüttenmänn. Monatshefte 2016, 161, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).