Abstract

The silicon content in steel is the key to the quality control of hot-dip galvanizing. Its fluctuation will directly restrict the application of galvanized steel by altering the interface reaction and structural stability. This study systematically explored the comprehensive effects of high silicon content in the steel substrate on the microstructure, interface reactions, defect distribution, and mechanical properties of the hot-dip galvanized coating through both experimental and theoretical calculations. Results indicate significant Si segregation at the coating/interface, with co-enrichment of P, leading to uncontrolled Fe-Zn reactions, destabilization of the δ-phase, and abnormal thickening of the ζ-phase (FeZn13), manifesting as the typical “Sandelin Effect.” CT analysis shows defect volumes distributed within 10−6–10−5 mm3, predominantly concentrated at the interface, which serve as primary channels for corrosion initiation and spalling failure. Mechanical tests demonstrate that high Si content weakens coating/substrate adhesion, reduces ductility, and accelerates the transition from ductile to brittle fracture under elevated temperatures. This study reveals that high Si content significantly degrades coating reliability through the coupled effects of “abnormal phase growth–element segregation–defect enrichment.” These findings provide theoretical and practical insights into interfacial instability mechanisms and coating optimization strategies for high-Si steel hot-dip galvanizing.

1. Introduction

Steel materials are widely used in construction, machinery, transportation, energy, aerospace, medical, and electronics due to their superior properties (e.g., high strength, weldability, and processability). However, they undergo varying degrees of corrosion in atmospheric, marine, soil, and construction environments. To ensure longevity and service performance, anti-corrosion technologies remain a key pursuit. Hot-dip galvanizing is an effective technique to protect steel against atmospheric corrosion [,]. Galvanized steel, characterized by low cost, high quality, and minimal environmental impact, is extensively applied in industrial production [,,]. Low-carbon steels (0.04–0.25 wt.% C) are typically used as substrates due to their good ductility, cold-formability, and forgeability [].

Industrial practice shows that strengthening elements added to steel substrates significantly influence coating microstructure and properties. Among common elements, C and Si exert the most pronounced effects, while Mn, P, and S exhibit lesser impacts. The form and content of C in steel alter Fe-Zn reactions []; increased C content intensifies Fe-Zn reactions, thickening intermetallic compounds (IMCs) and degrading mechanical properties. Si, an attractive strengthening element, enhances hardness without sacrificing ductility. In advanced high-strength steels (AHSS), Si concentrations reach 2 wt.% in Quenching and Partitioning (Q&P) steels to suppress cementite precipitation and retain austenite [,]. However, Si detrimentally affects galvanized coatings. At low Si content, dense δ-phase layers form, whereas higher Si content (>0.3 wt.%) promotes coarse, loosely packed crystals []. Elevated Si triggers abnormal growth of the brittle ζ-phase (FeZn13), increasing coating thickness, forming poorly adherent dark coatings, and deteriorating appearance, microstructure, and performance—termed the “Sandelin Effect” []. Studies on liquid metal embrittlement (LME) susceptibility reveal that Si inhibits IMC formation at the AHSS/liquid Zn interface []. Si enrichment at the interface impedes Fe-Zn reactions, attributed to Si insolubility in liquid Zn causing “inverse diffusion.” This enrichment exacerbates LME by hindering protective IMC formation and delaying substrate dissolution, allowing more free Zn to penetrate grain boundaries. Additionally, Si oxidizes during pre-annealing, forming surface oxides that suppress interfacial interactions []. Si dissolution in α-Fe alters steel properties [,] and modifies Fe-Zn reaction kinetics. Si solubility in Fe-Zn IMCs critically governs the appearance and performance of galvanized AHSS coatings [,]. A typical hot-dip galvanized coating comprises five phases: Γ (Fe3Zn10), Γ1 (Fe11Zn40), δₗₖ (FeZn7), δ1ₚ (Fe13Zn126), and ζ (FeZn13), arranged sequentially from the steel/coating interface to the surface with decreasing Fe content [,], reflecting interfacial reaction and diffusion processes.

Although comparing coatings with different Si levels could further illustrate the influence of Si on interfacial bonding, deformation behavior, and fracture mechanisms—as also suggested by the reviewer—the present work focuses on a representative high-Si steel (0.1885 wt.% Si). This Si level lies within the Sandelin–Sebisty transition zone, where δ-phase instability, ζ-phase abnormal growth, and interfacial embrittlement are most severe in industrial production. Therefore, instead of varying Si content, this study concentrates on elucidating the intrinsic mechanisms governing coating instability under this typical high-Si condition. By integrating multiscale characterization with first-principles calculations, the study reveals how Si enrichment drives δ-phase destabilization, ζ-phase thickening, defect accumulation, and mechanical degradation, providing a mechanistic basis for optimizing coating reliability in high-Si steels.

This study employs experimental characterization and theoretical calculations to systematically elucidate the effects of high solute Si on the microstructure and properties of hot-dip galvanized coatings. Although the influence of Si on galvanizing reactions has been widely reported, most existing studies focus on low-Si regimes and the classical Sandelin phenomenon, whereas a systematic understanding of interfacial instability, defect formation, and failure behavior in high-Si steels (>0.15 wt.%) under industrial galvanizing conditions remains limited. Here, by integrating CT-based 3D reconstruction with first-principles calculations, this work reveals—both experimentally and at the electronic-structure level—how Si segregation and oxidation weaken Fe-Zn interfacial bonding and accelerate coating degradation, providing new mechanistic insight into coating reliability for high-Si steels. SEM and LSCM analyze coating microstructure and 3D morphology to clarify Si’s role in spangle formation, surface roughness, and crack initiation. XRD and XPS determine phase composition and elemental valence states, combined with Fe-Zn-Si ternary phase diagrams, to reveal δ-phase instability and ζ-phase abnormal growth mechanisms. CT reconstructs 3D defect distributions to analyze pore/crack concentration at interfaces. DFT calculations model Fe(Si)/Zn and Fe(Si)/Zn@O interfaces to examine electronic structures, density of states, and diffusion energy barriers, elucidating how Si segregation and oxidation compromise interfacial stability. Finally, tensile tests at room and intermediate temperatures uncover Si-induced interfacial instability and defect evolution on mechanical properties and fracture modes. These results provide new micro-scale insights into the Sandelin Effect and theoretical guidance for optimizing galvanizing processes and enhancing coating reliability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Steel Substrate and Specimen Preparation

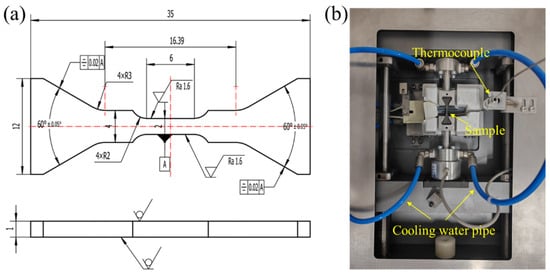

Commercial galvanized steel sheets (1.00 ± 0.02 mm) supplied by the Carbon Steel Sheet Plant of JISCO (Jiayuguan, China) were used in this study. The substrate composition was 0.0465 C, 0.1885 Si, 0.1428 Mn, 0.0036 P (wt.%), with the remainder Fe, and all materials originated from a single production heat to ensure compositional consistency. Dog-bone specimens for tensile and in situ cyclic loading experiments were machined by electrical discharge machining (EDM), as shown in Figure 1a. A representative high-Si low-carbon steel containing approximately 0.19 wt.% Si was intentionally selected because it falls within the classic Sandelin range (0.12–0.25 wt.% Si), where excessive coating growth, interfacial brittleness, and delamination commonly occur during industrial galvanizing. Rather than conducting statistical comparisons among various Si levels, this study focuses on this typical high-Si composition to elucidate Si-induced interfacial reaction instability, coating growth behavior, and defect evolution mechanisms. Moreover, choosing this Si content ensures consistency between experimental conditions and the Fe(Si)/Zn interface model adopted in the accompanying DFT calculations, thereby enabling a coherent interpretation of both experimental and theoretical results.

Figure 1.

(a) Geometric Dimensions of In Situ cyclic loading Specimen (unit: mm, letter A is the tolerance); (b) In Situ cyclic loading Testing Setup.

2.2. Industrial Pretreatment and Hot-Dip Galvanizing

Specimens were processed on a full-scale continuous hot-dip galvanizing line. Pretreatment included alkaline cleaning (25–35 g/L NaOH, 65 ± 3 °C, 3 min), double rinsing, and acid pickling (8 ± 1 wt.% HCl, 30 ± 2 °C, 90 s) with 0.1 wt.% surfactant. Fluxing was carried out in a NH4Cl/ZnCl2 double-salt bath (2:1 mass ratio, 180–220 g/L total salts, pH 4.6–5.0, 65 ± 3 °C). The sheets were then dried and annealed at 800 ± 10 °C under a N2–H2 protective atmosphere (H2 ≈ 5%).

Hot-dip galvanizing was conducted in a high-purity Zn bath (460 ± 3 °C, 0.15–0.20 wt.% Al, <0.20 wt.% Fe) for 5 ± 1 s. Nitrogen gas-wiping (0.20 ± 0.02 MPa) controlled the coating mass, yielding 60–70 g/m2 (two sides) corresponding to an η-layer of ~10 µm. No passivation treatment was applied to avoid modifying surface chemistry.

2.3. Metallographic Preparation

Coating cross-sections were cold-mounted, ground using P320–P1200 SiC papers, polished with 3 µm and 1 µm diamond suspensions, and finished using 0.05 µm colloidal silica. Samples were ultrasonically cleaned in ethanol and dried. Surface morphology analyses used the as-deposited coating without mechanical abrasion.

2.4. Mechanical Testing

Tensile and in situ tests were performed on an Mtest5000-K-H system (Sinotest Equipment, Changchun, China) at 25 °C and 300 °C, as shown in Figure 1b. High-temperature tests included a 0.5 h hold prior to loading. A constant displacement rate of 0.2 mm/min was applied. Load–unload–reload cycles were used to quantify back-stress evolution, following ISO 6892-1 [] specimen geometry and gripping requirements.

2.5. Microstructural and Surface Characterization

Microstructure and fracture morphology were examined using FE-SEM (FEI QUANTA FEG450, Hillsboro, OR, USA, 10–15 kV) coupled with EDS (Oxford X-Max80, Abingdon, UK). Three-dimensional surface topography and roughness were measured using a laser scanning confocal microscope (ZEISS LSM800, Oberkochen, Germany) over a 1.0 × 1.0 mm2 area with a 20× objective.

Phase identification used XRD (Bruker D8 ADVANCE, Billerica, MA, USA, Cu Kα, 20–90°, 0.02° step). XPS (Shimadzu AXIS SUPRA, Kyoto, Japan, Al Kα) was employed to assess surface chemistry and valence states without ion sputtering. Internal pores and cracks were visualized using micro-focus X-ray CT (Shimadzu SMX-225CT, Kyoto, Japan, voxel size 2.0–2.5 µm). Thermal properties were measured using an LW-9389 interface thermal analyzer (LongWin, Taichung, Taiwan), with triplicate tests for reproducibility.

2.6. First-Principles Calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using CASTEP. Interface models consisted of α-Fe(001) slabs with partial substitution of surface Fe by Si (3–5 at.%), overlain by hcp-Zn(0001). An additional Fe(Si)/Zn@O model was constructed by introducing interstitial O atoms to mimic oxidized/Si-rich interfaces. A 15 Å vacuum layer prevented spurious interactions.

The PBE-GGA functional and ultrasoft pseudopotentials were used with a 500 eV cutoff and a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack grid. Energy and force convergence criteria were 1 × 10−6 eV/atom and 0.02 eV/Å. DOS, electron localization functions, and differential charge densities were extracted from optimized structures. Si diffusion barriers were computed via climbing-image NEB (CI-NEB) with a maximum force threshold of 0.05 eV/Å. Visualization was performed using VESTA (ver. 3.90.5a, 31 January 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Surface Morphology and 3D Topography of the Coating

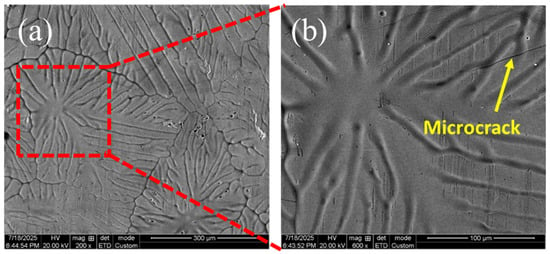

Figure 2 shows the surface morphology of the galvanized coating obtained from the high-Si steel substrate. The coating exhibits distinct spangle structures with grain radii of approximately 300–350 μm, indicating strong dependence of Zn solidification behavior on local substrate composition. At higher magnification (Figure 2b), multiple microcracks are observed within the coating surface, typically located at grain boundaries or between spangle regions. These cracks reflect mechanical mismatches between solidified Zn and underlying intermetallic layers, and they correspond well to the crack features noted during galvanizing.

Figure 2.

SEM Photographs of Coating Microstructure: (a) Spangle Morphology; (b) Magnified View of Boxed Region in (a), with Surface Microcracks in Galvanized Coating Indicated by Yellow Arrows.

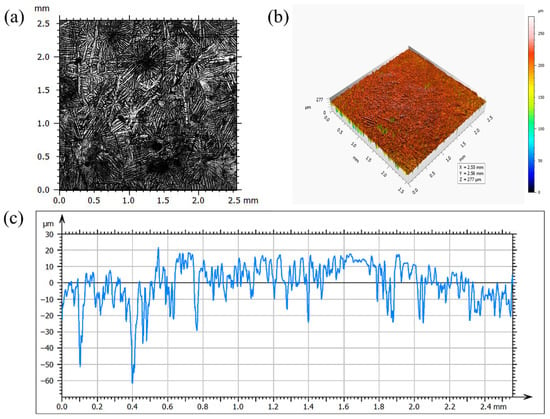

Three-dimensional confocal topography (Figure 3) further demonstrates that the surface is highly uneven, with peak-to-valley variations up to 131 μm. The majority of the surface undulations fall within ±20 μm, but several regions show significantly higher asperities attributable to coarse ζ-phase outgrowths beneath the η-phase. Line-scan profiles yield an average surface roughness (Ra) of 9.7 μm, confirming that the coating formed on high-Si steel possesses considerable roughness. These observations collectively indicate that high Si content leads to the formation of a rough, crack-containing, and morphologically heterogeneous coating surface.

Figure 3.

Confocal Characterization of Zn Coating: (a) Microscopic Morphology; (b) Three-Dimensional Topography; (c) Line-Scanning Profile.

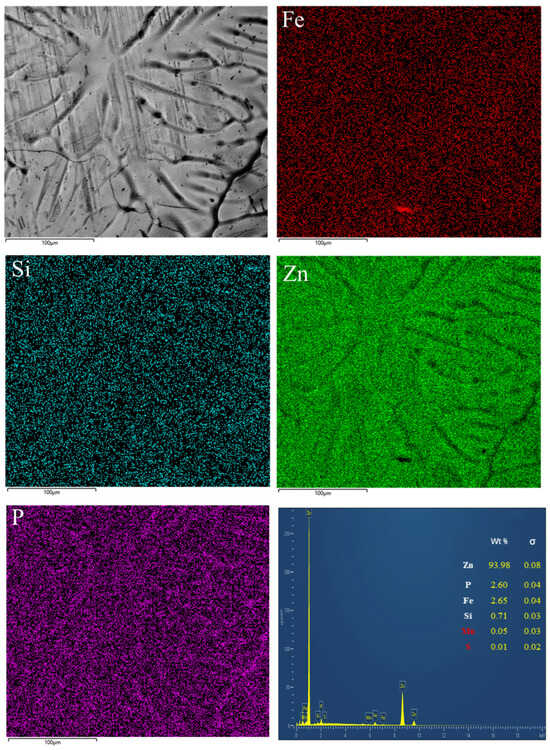

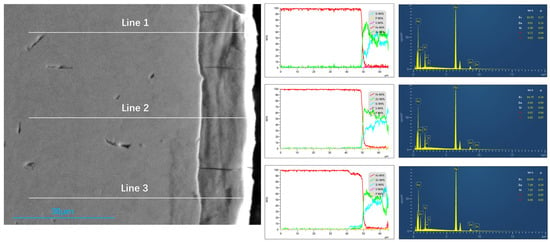

3.2. Surface and Cross-Sectional Elemental Distribution

Figure 4 presents the surface elemental distribution of the coating. Zn is uniformly distributed across the surface, while localized enrichment of P is observed within surface depressions. The P originates from substrate impurities or trace bath components and tends to accumulate at regions where Zn wetting or Fe-Zn reactions were hindered.

Figure 4.

Elemental Surface Distribution in Coating.

Cross-sectional EDS line-scans (Figure 5) provide further insight into element distribution across the coating-substrate interface. While Si remains relatively constant within the steel substrate, its concentration increases sharply within the alloy layer, demonstrating strong Si segregation during galvanizing. These results are consistent across repeated measurements. Additionally, microcracks propagating from the coating through to the steel substrate are clearly visible, consistent with the surface cracks shown in Figure 2. Such cracks introduce pathways for corrosive penetration and weaken coating adhesion. The line-scan also shows local Fe enrichment at crack-affected regions, indicating partial coating spallation consistent with regions of Zn loss. These results establish that Si migration, P segregation, and microcrack development collectively modify the interfacial chemistry and integrity of the galvanized coating.

Figure 5.

Elemental Line Distribution at Coating Cross-Section.

3.3. Phase Composition and Valence State Characterization

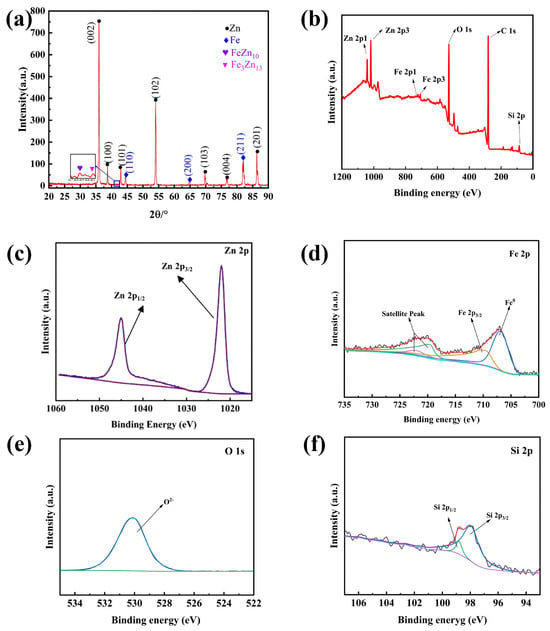

XRD analysis (Figure 6a) confirms the presence of strong η-Zn peaks, along with α-Fe signals originating from the thin nature of the coating. Weak peaks corresponding to δ(FeZn10) and ζ(FeZn13) phases are also visible, demonstrating the formation of Fe-Zn intermetallic compounds. The relatively weak intensity of these peaks corresponds to thin intermetallic layers expected from short dipping times in the industrial galvanizing process.

Figure 6.

Analysis of Phase Composition and Elemental Valence States in Zn Coating. (a) XRD pattern; (b) XPS survey spectrum; (c) Zn 2p spectrum; (d) Fe 2p spectrum; (e) O 1s spectrum; (f) Si 2p spectrum.

XPS spectra (Figure 6b–f) provide further information on elemental states. Zn exists largely as metallic Zn along with surface oxides (ZnO), while Fe is present in both metallic (Fe0) and oxidized (Fe3+) forms, indicating partial exposure of the substrate at microcracked or thin coating regions. Si is detected predominantly as SiO2, suggesting oxidation of segregated Si at or near the interface. Thermo-Calc modeling of the Fe-Zn-Si ternary system (Figure 7) shows that under high-Si conditions, δ-phase stability is reduced and multiphase fields containing ζ-phase and FeSi become favored. This aligns with the experimentally detected δ/ζ intermetallics and supports the conclusion that high Si content significantly alters alloy layer stability and phase evolution.

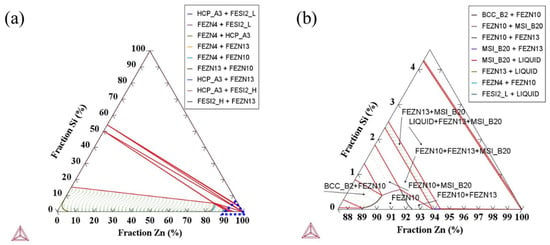

Figure 7.

Fe-Zn-Si Ternary Phase Diagram at 460 °C. (a) Isothermal section of the Fe-Zn-Si ternary system; (b) Magnified view of the low-Si region within the dotted triangular area in (a).

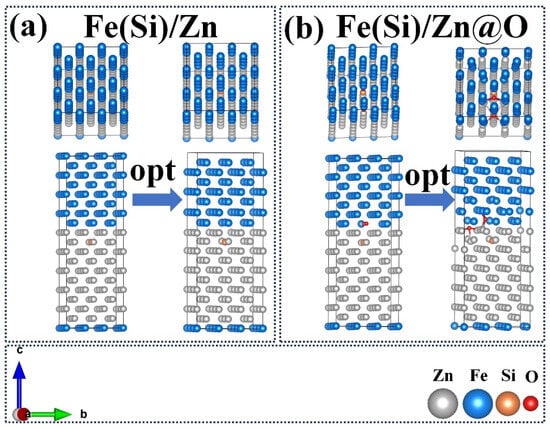

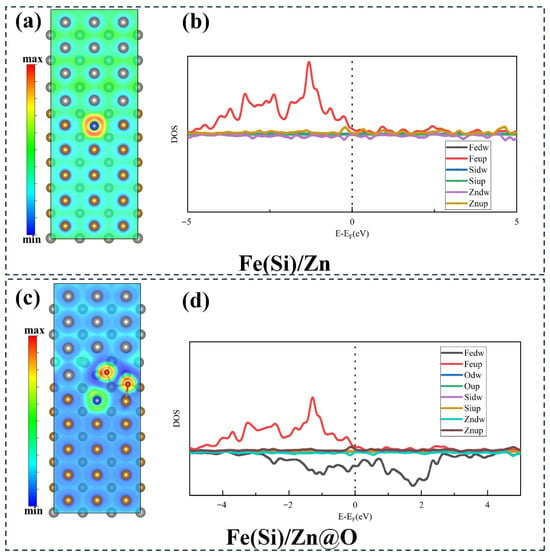

3.4. DFT Simulation of Fe(Si)/Zn Interfaces

First-principles calculations were performed to evaluate the atomic-scale interaction between Fe(Si) and Zn under oxygen-free and oxygen-rich conditions (Figure 8). In the Fe(Si)/Zn interface model, electron density is shared predominantly through metallic bonding, indicating moderate interfacial stability. However, when oxygen is introduced (Fe(Si)/Zn@O), the interfacial electronic distribution changes significantly; O atoms form strong Fe-O and Zn-O localized bonding, modifying charge distribution and altering interface characteristics.

Figure 8.

Top/Front Views of Interface Structure Models and Geometric Optimization Models. (a) Fe(Si)/Zn interface structure; (b) Fe(Si)/Zn@O interface structure.

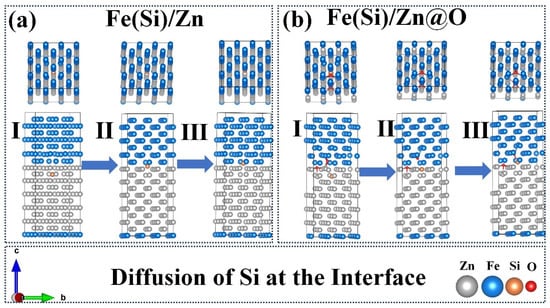

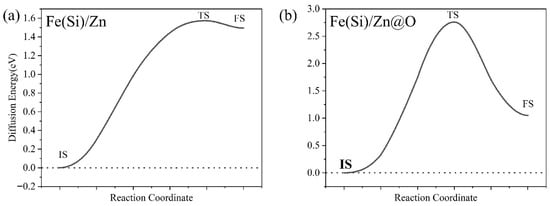

Electron localization function (ELF) and density of states (DOS) analyses (Figure 9) reveal that oxygen markedly increases interfacial electron localization, weakening long-range metallic bonding and introducing states that trap diffusing species. Diffusion pathway analysis (Figure 10) demonstrates that Si atoms experience relatively open diffusion channels in the oxygen-free interface, whereas oxygen constricts these channels. Corresponding energy barrier calculations (Figure 11) show that Si migration barriers increase dramatically from 1.5 eV (Fe(Si)/Zn) to 2.6 eV (Fe(Si)/Zn@O), indicating that oxygen-rich interfaces strongly inhibit Si diffusion. These atomistic results provide theoretical support for the experimentally observed accumulation of Si in specific interfacial zones and its limited redistribution once trapped.

Figure 9.

Electron Localization Function and Partial Density of States of Interface Structure Models. (a,b) Fe(Si)/Zn interface structure; (c,d) Fe(Si)/Zn@O interface structure.

Figure 10.

Diffusion of Si in Two Interface Structures. (a) Fe(Si)/Zn interface structure; (b) Fe(Si)/Zn@O interface structure (I, II, III denote initial diffusion state, transition state, and terminal state, respectively).

Figure 11.

Diffusion Energy Barrier Profiles of Si in Two Interface Structures. (a) Fe(Si)/Zn interface structure; (b) Fe(Si)/Zn@O interface structure.

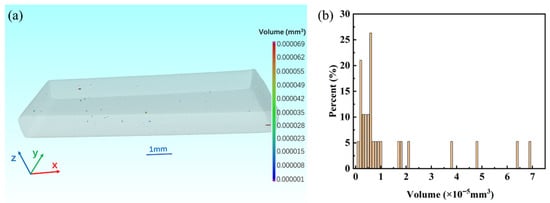

3.5. Coating Defect Characterization

Three-dimensional CT analysis (Figure 12) reveals defect volumes ranging from 1 × 10−6 to 6.9 × 10−5 mm3. These defects are not uniformly distributed but instead concentrate near the coating/substrate interface, forming defect clusters that often exceed 10−5 mm3 in volume. Smaller defects appear as microvoids along grain boundaries, while larger voids correspond to incomplete bonding or shrinkage during solidification. The presence of larger interfacial voids indicates potential local bath wetting issues or accelerated Fe-Zn reactions that disrupted uniform alloy layer formation.

Figure 12.

CT-Based Defect Analysis of Zn Coating. (a) Three-dimensional defect distribution in the coating sample; (b) Volume fraction of three-dimensional defects in the coating sample.

The coincidence of CT-detected voids with EDS-identified segregation zones suggests a strong correlation between compositional inhomogeneity and defect formation. Defects of this magnitude are known to significantly reduce coating adhesion and can act as crack-initiation sites during mechanical loading or corrosion processes.

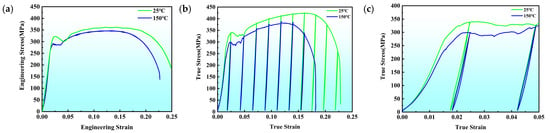

3.6. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Morphology

Engineering stress–strain curves (Figure 13a and Table 1) show that at 150 °C, the coated steel exhibits reduced yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation compared with room temperature, demonstrating classical thermal softening behavior. Load–unload–reload results (Figure 13b,c) reveal pronounced hysteresis loops at 25 °C, indicating significant back-stress hardening produced by constraints between the coating and substrate. At 150 °C, these hysteresis loops diminish due to increased atomic mobility, decreased interfacial strength, and reduced dislocation storage.

Figure 13.

Mechanical Properties of Zn-Coated Specimens. (a) Engineering stress–strain curves at 25 °C and 150 °C; (b) Back-stress curves at 25 °C and 250 °C; (c) Magnified view of dotted box region in (b).

Table 1.

Tensile properties of the specimen at 25 °C and 150 °C.

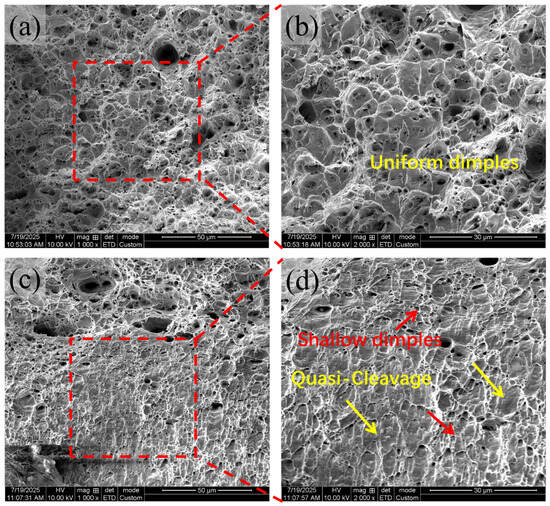

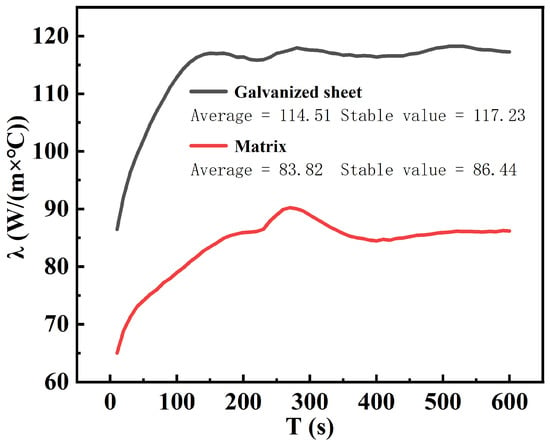

Fracture morphology (Figure 14) further highlights temperature effects. At 25 °C, fracture surfaces are dominated by deep, uniformly distributed dimples characteristic of ductile rupture. At 150 °C, dimples become shallower and less uniform, and quasi-cleavage facets appear, indicating reduced plasticity and a transition toward mixed-mode fracture. Despite interfacial instability, thermal conductivity measurements (Figure 15) reveal that the galvanized sheet demonstrates significantly improved thermal conductivity (117.23 W/(m·K)) compared to the steel substrate (86.44 W/(m·K)) [], attributed to the high conductivity of the Zn layer.

Figure 14.

Tensile Fracture Morphologies at Different Temperatures. (a) 25 °C; (b) Magnified view of boxed region in (a); (c) 150 °C; (d) Magnified view of boxed region in (c).

Figure 15.

Thermal Conductivity of Iron Substrate and Galvanized Sheet.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Si on Surface Morphology, Spangle Features, and Alloy Layer Growth

The surface features observed in Figure 2 and Figure 3—coarse spangle structures, significant height variation, and microcrack formation—are direct consequences of elevated Si content in the steel substrate. High Si disrupts the stability of the Fe2Al5/FeAl3 inhibition layer, which normally suppresses excessive Fe dissolution during galvanizing. When this inhibition layer becomes unstable, Fe-Zn reactions intensify, promoting abnormal growth of the ζ-phase (FeZn13), which has inherently coarse, porous morphology []. The protrusion of ζ-phase grains through the η-phase results in the observed high roughness (Ra ≈ 9.7 μm). Additionally, thermal contraction mismatch and local intermetallic embrittlement contribute to surface microcracking. These results are consistent with earlier reports on the Sandelin and Sebisty ranges, where Si contents of 0.12–0.25 wt.% dramatically increase coating reactivity [,,,].

4.2. Si/P Co-Segregation, Interfacial Chemistry, and Phase Evolution

The elemental mapping results (Figure 4 and Figure 5) clearly demonstrate strong Si enrichment within the coating and localized P accumulation. Both Si and P are known to segregate to grain boundaries and interfacial regions due to their high grain boundary diffusion coefficients. Their co-segregation inhibits uniform formation of Fe-Zn intermetallic compounds by altering diffusion pathways and creating reaction barriers []. As shown in the Fe-Zn-Si phase diagram (Figure 7), high Si reduces δ-phase stability and shifts the system toward ζ-phase and FeSi-containing multiphase fields. The formation of FeSi—one of the hardest and most brittle intermetallics in this system—contributes to porous alloy layer formation and explains the interfacial brittleness observed in the coating.

Furthermore, the presence of SiO2 at the interface, detected via XPS, suggests that Si oxidation occurs during galvanizing. These oxides inhibit wetting and Fe-Zn reaction kinetics, leading to discontinuous intermetallic layers and microcrack formation. Thus, Si/P co-segregation, phase destabilization, and interfacial oxidation work synergistically to degrade coating continuity and bonding strength.

4.3. Atomic-Scale Mechanisms of Segregation and Interfacial Embrittlement

The DFT analysis provides mechanistic insight into the experimentally observed segregation behavior. Oxygen-rich Fe(Si)/Zn interfaces exhibit substantially increased electron localization around O atoms, producing stronger local bonding that suppresses Si mobility. This leads to Si entrapment at oxidized interfacial sites, consistent with EDS and XPS observations of localized Si accumulation. Energy barrier calculations show that Si diffusion is significantly hindered in oxygen-rich environments, suggesting that once Si reaches oxidized regions, its ability to redistribute becomes severely restricted.

Because Si reduces δ-phase stability and promotes ζ-phase formation, such trapped Si yields regions with excessive ζ-phase outgrowth and brittle FeSi formation. This provides an atomistic explanation for the δ-phase fragmentation and porous ζ-phase morphology observed experimentally. The DFT results therefore strongly support the notion that Si segregation and oxidation directly drive interfacial embrittlement and microdefect accumulation.

4.4. Defect Formation, Mechanical Response, and the Integrated Failure Mechanism

CT analysis (Figure 12) reveals concentrated interfacial defects that coincide with Si- and P-segregated regions. These structural and chemical discontinuities create weak areas prone to crack initiation. During mechanical loading, these defects promote early debonding and reduce the ability of the coating to withstand stress. The diminished hysteresis loops at 150 °C (Figure 13) indicate that elevated temperature reduces back-stress hardening, likely due to thermal activation enabling dislocation bypass of interfacial constraints and local weakening of the brittle alloy layers.

Fractography results (Figure 14) further confirm that high Si content induces a clear transition from ductile fracture to a mixed brittle–ductile failure mode, consistent with interfacial embrittlement and the formation of porous intermetallic structures. Integrating these observations across multiple scales, it becomes evident that the degradation of coating integrity arises from a coupled deterioration process in which abnormal ζ-phase growth roughens the surface and generates local stress concentrations, while δ-phase destabilization yields porous and discontinuous alloy layers that are inherently fragile [,,]. Simultaneously, Si/P co-segregation and interfacial oxidation weaken metallurgical bonding and disrupt the uniform development of Fe-Zn intermetallics, and atomic-scale diffusion suppression caused by oxygen-rich interfaces further traps Si at vulnerable sites, amplifying local chemical and structural inhomogeneity. These effects collectively promote the accumulation of interfacial defects, accelerate crack initiation, and facilitate coating delamination under mechanical or thermal loading. Through these synergistic mechanisms, high Si content significantly compromises the mechanical stability and interfacial reliability of hot-dip galvanized coatings.

5. Conclusions

Through systematic analysis of elemental distribution, phase diagram calculations, and mechanical properties of the galvanized coating, the following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- In the steel substrate with 0.1885% Si, the galvanized coating exhibits typical “Sandelin Effect”: the ζ-phase (FeZn13) grows rapidly and non-uniformly, forming a thick, porous alloy layer with a dull, rough surface accompanied by microcracks. Simultaneously, Si significantly enriches in the coating and interfacial regions, co-segregating with P, which weakens the coating-substrate adhesion and promotes the precipitation of hard brittle phases such as FeSi. This destabilizes the δ-phase, transforming the alloy layer from dense and continuous to loose and heterogeneous.

- (2)

- CT-based 3D reconstruction and fracture-surface SEM consistently show that defects are predominantly concentrated at the coating/substrate interface, with typical volumes of 10−6–10−5 mm3. These voids and microcracks spatially coincide with Si-P co-segregation and oxide-enriched regions, serving as preferential pathways for corrosive penetration and crack initiation. δ-phase destabilization induced by high Si further weakens interfacial bonding and accelerates defect accumulation, ultimately promoting early coating delamination and mechanical failure.

- (3)

- Mechanical tests indicate that elevated temperatures diminish the back-stress effect, and the fracture mode transitions from dimple-dominated ductile fracture at room temperature to quasi-brittle and dimple mixed mode at high temperatures. This reflects the detrimental impact of interfacial defects and Si segregation on material plasticity and reliability. Despite interfacial instability, the coating’s high thermal conductivity offers positive value for applications in heat-dissipation-sensitive fields.

- (4)

- First-principles calculations show that Si strongly segregates to the Fe/Zn interface and further enhances interfacial bonding under oxidizing conditions by forming electronically localized Fe-O and Zn-O bond networks. This electronic localization suppresses atomic diffusion, destabilizes the δ phase, and promotes abnormal ζ-phase growth. The DFT results provide atomistic insight into how Si-induced modifications in electronic structure hinder interfacial reactions and enhance embrittlement, offering a theoretical basis for understanding coating failure in high-Si steels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and X.T.; methodology, J.R. and D.Q.; software, P.P. and J.R.; validation, J.S. and D.Q.; formal analysis, J.S.; investigation, X.L. and J.H.; data curation, J.S. and J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Q.; writing—review and editing, P.P.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, P.P. and X.T.; project administration, X.T.; funding acquisition, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is financially supported by the Gansu Province science and technology plan project (25CXGA049), the Jiayuguan City major science and technology special fund (23-01), Jiayuguan City key research and development plan (24-11).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Degao Qiao and Peng Peng were employed by Carbon Steel Sheet Factory, Jiuquan Iron and Steel (Group) Co., Ltd. Author Junfei Huang was employed by the company Shimadzu (China) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Arianpouya, N.; Shishesaz, M.; Arianpouya, M.; Nematollahi, M. Evaluation of synergistic effect of nanozinc/nanoclay additives on the corrosion performance of zinc-rich polyurethane nanocomposite coatings using electrochemical properties and salt spray testing. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 216, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepperta, T.A.; Luckenederb, G.; Stellnbergerb, K.H.; Moria, G.; Antrekowitsch, H. Investigation of the corrosion behavior of Zn-Al-Mg hot-dip galvanized steel in alternating climate tests. Corrosion 2014, 70, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyei, S.; Sekyere, K.O.; Kwofie, J.J. Tensile strength and micro-hardness properties of common roofing sheets in Ghana Diyala. J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 15, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- de Azevedo Alvarenga, E.; Lins, V.D.F.C. Atmospheric corrosion evaluation of electrogalvanized, hot-dip galvanized and galvannealed interstitial free steels using accelerated fi eld and cyclic tests. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 306, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewa, R.E.; Afolalu, S.A.; Fayomi, O.S.I. Overview production process and properties of galvanized roofing sheets. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1378, 022069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coni, N.; Gipiela, M.L.; D’Oliveira, A.S.C.M.; Marcondes, P.V.P. Study of the mechanical properties of the hot dip galvanized steel galvalume. J. Brazil Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2009, 31, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, J.G.; Assunção, F.C.; Matlock, D.K.; Edmonds, D.V. The ‘quenching and partitioning’ process: Background and recent progress. Mater. Res. 2005, 8, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlock, D.K.; Speer, J.G. Third generation of AHSS: Microstructure design concepts. In Microstructure and Texture in Steels: And Other Materials; Springer: London, UK, 2009; pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Matlock, D.K.; Speer, J.G. Processing opportunities for new advanced high-strength sheet steels. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2010, 25, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto, A.; Inagaki, J.; Nakaoka, K. Effects of surface microstructure and chemical compositions of steels on formation of Fe-Zn compounds during continuous galvanizing. Trans. Iron Steel Inst. jpn 1986, 26, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.D.; Uwakweh, O.N.C. Verification of Sandelin phenomena in mechanically alloyed Fe-Zn and Fe-Zn-Si. Mater. Trans. 1997, 38, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Cho, L.; Colburn, J.; van der Aa, E.; Pichler, A.; Pottore, N.; Ghassemi-Armaki, H.; Findley, K.O.; Speer, J.G. Silicon effect on retardation of Fe-Zn alloying behavior: Towards an explanation of liquid zinc embrittlement susceptibility of third generation advanced high strength steels. Corros. Sci. 2024, 235, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minenkov, A.; Arndt, M.; Knapp, J.; Hesser, G.; Gierl-Mayer, C.; Mörtlbauer, T.; Angeli, G.; Groiss, H. Interaction and evolution of phases at the coating/substrate interface in galvannealed 3rd Gen AHSS with high Si content. Mater. Des. 2024, 237, 112597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.Y. Control of silicon reactivity in general galvanizing. J. Phs. Eqil. Diff. 2008, 29, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, N.; Hayano, K.; Suzuki, A.; Kobashi, M. Enhanced interfacial reaction of Fe-Si alloy sheets hot-dipped in Zn melt at 460 °C. ISIJ Int. 2018, 58, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S. Effects of Si solid solution in Fe substrate on the alloying reaction between Fe substrate and liquid Zn. ISIJ Int. 2017, 57, 2214–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko-Chun, L.I.N.; Chao-Sung, L.I.N. Effect of silicon in dual phase steel on the alloy reaction in continuous hot-dip galvanizing and galvannealing. ISIJ Int. 2014, 54, 2380–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, N.L.; Tanaka, K.; Yasuhara, A.; Inui, H. Structure refinement of the δ1p phase in the Fe-Zn system by single-crystal X-ray diffraction combined with scanning transmission electron microscopy. Acta Cryst. 2014, B70, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, N.L.; Yasuhara, A.; Inui, H. Order–disorder structure of the δ1k phase in the Fe-Zn system determined by scanning transmission electron microscopy. Acta Mater. 2014, 81, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6892-1:2019; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Alghamdi, A.; Alharthi, H.; Alanazi, A.; Halawani, M. Effects of Metal Fasteners of Ventilated Building Facade on the Thermal Performances of Building Envelopes. Buildings 2021, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F. The Thermodynamic Analysis of Alloy Systems Used in ZincBath of Hot-Dipping Galvanizing and Its Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Che, C. Study on the Mechanism of Sandelineffect and Its Solutions. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abeln, B.; Pinger, T.; Richter, C.; Feldmann, M. Adhesion of batch hot-dip galvanized components. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 5197–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Study on High-Temperature (520–600 °C) Hot-Dip Galvanized Steel. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Cao, S.; Wan, G. Analysis on Brittle Fracture of 20Mn2 Steel Ring Chains. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2009, 4, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Su, X.; He, Y. Growth of intermetallic compounds in solid Zn/Fe andZn/Fe-Si diffusion couples. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2008, 18, 1639–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, M.A.; Mishra, A.; Benson, D.J. Mechanical properties of nanocrystalline materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2006, 51, 427–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Liu, X.; Jiang, S. Influence of Substrate Temperature on the Microstructure and Properties of Zinc Coatings Deposited by Vacuum Thermal Evaporation. Chin. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 946–951. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, S.; Lu, H. Microstructure and properties of laser spiral spot welding and resistance spot welding DC06 galvanized steel joints. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2023, 44, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).