The Effect of the Rolling Reduction Ratio on the Superelastic Properties of Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn (wt%)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Zain, Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Hosoda, H.; Nam, T.H.; Miyazaki, S. Shape memory properties of Ti-Nb-Mo biomedical alloys. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 4212–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Miyazaki, S. Several Issues in the Development of Ti–Nb-Based Shape Memory Alloys. Shape Mem. Superelast. 2016, 2, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Miyazaki, S. Martensitic Transformation and Superelastic Properties of Ti-Nb Base Alloys. Mater. Trans. 2015, 56, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.F.; Kim, H.Y.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Superelastic properties of biomedical (Ti-Zr)-Mo-Sn alloys. Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. 2015, 48, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Karaman, I.; Maier, H.J.; Chumlyakov, Y.I. Superelastic cycling and room temperature recovery of Ti74Nb26 shape memory alloy. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 2216–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Ikehara, Y.; Kim, J.I.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Martensitic transformation, shape memory effect and superelasticity of Ti-Nb binary alloys. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 2419–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerig, T.W.; Melton, K.N.; Stöckel, D.; Wayman, C.M. Engineering Aspects of Shape Memory Alloys; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jani, J.M.; Leary, M.; Subic, A.; Gibson, M.A. A review of shape memory alloy research, applications and opportunities. Mater. Design 2014, 56, 1078–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.L.; Li, S.J.; Sun, S.Y.; Yang, R. Effect of Zr and Sn on Young’s modulus and superelasticity of Ti-Nb-based alloys. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 441, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.F.; Kim, H.Y.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Effect of Sn addition on stress hysteresis and superelastic properties of a Ti-15Nb-3Mo alloy. Scr. Mater. 2014, 72, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Tobe, H.; Kim, J.; Miyazaki, S. Crystal Structure, Transformation Strain, and Superelastic Property of Ti–Nb–Zr and Ti–Nb–Ta Alloys. Shape Mem. Superelast. 2015, 1, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Kim, J.I.; Inamura, T.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Effect of Ta addition on shape memory behavior of Ti-22Nb alloy. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 417, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Kim, H.Y.; Inamura, T.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Shape memory characteristics of Ti-22Nb-(2-8)Zr(at.%) biomedical alloys. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 403, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Watanabe, S.; Hanada, S. Beta TiNbSn alloys with low young’s modulus and high strength. Mater. Trans. 2005, 46, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavon, L.L.; Kim, H.Y.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Effect of Nb content and heat treatment temperature on superelastic properties of Ti-24Zr-(8-12)Nb-2Sn alloys. Scr. Mater. 2015, 95, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Koyano, T.; Miyazaki, S. Effects of oxygen concentration and temperature on deformation behavior of Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta-O alloys. Scr. Mater. 2016, 123, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, N.L.; Talbot, C.E.P.; Fairclough, S.M.; Jones, N.G. The total stress approach to martensitic transformations in Ti–Nb-based alloys. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, N.L.; Talbot, C.E.P.; Jones, N.G. On the Influence of Thermal History on the Martensitic Transformation in Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn (wt%). Shape Mem. Superelast. 2021, 7, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Kim, J.I.; Inamura, T.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Effect of thermo-mechanical treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory behavior of Ti-(26-28) at.% Nb alloys. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 438, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, N.L.; Hildyard, E.M.; Jones, N.G. The influence of grain size on the onset of the superelastic transformation in Ti-24Nb-4Sn-8Zr (wt%). Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 828, 142072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Castany, P.; Cornen, M.; Thibon, I.; Prima, F.; Gloriant, T. Texture investigation of the superelastic Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2014, 591, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, F.J. Recrystallization and Related Annealing Phenomena; Elsevier: Kidlington, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.B.; Liu, W.C.; Xiang, S.; Zhao, F.; Liang, Y.L. Effect of Grain Size on Stress-Induced Martensitic Transformation in Solution-Treated 51.1Zr-40.2Ti-4.5Al-4.2V Alloy. Met. Mater. Trans. A. 2018, 49, 6040–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.J.; Zhao, H.T.; Han, R.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ma, M.Z.; Liu, R.P. Grain refinement and tensile properties of a metastable TiZrAl alloy fabricated by stress-induced martensite and its reverse transformation. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 722, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.C.; Lin, J.G.; Wen, C. Influences of recovery and recrystallization on the superelastic behavior of a β titanium alloy made by suction casting. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 5972–5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, E.; Sakurai, T.; Watanabe, S.; Masahashi, N.; Hanada, S. Effect of heat treatment and sn content on superelasticity in biocompatible TiNbSn alloys. Mater. Trans. 2002, 43, 2978–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Wayman, C.M. Shape Memory Materials, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J.R.; Cohen, M. Criterion for the action of applied stress in the martensitic transformation. Acta Met. Mater. 1953, 1, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, E.N.D.; Chagnon, G.; de Oliveira, H.M.R.; Favier, D. Anisotropy and Clausius-Clapeyron relation for forward and reverse stress-induced martensitic transformations in polycrystalline NiTi thin walled tubes. Mech. Mater. 2020, 146, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkan, S.; Sehitoglu, H. Prediction of transformation stresses in NiTi shape memory alloy. Acta Mater. 2019, 175, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidharth, R.; Celebi, T.B.; Sehitoglu, H. Origins of functional fatigue and reversible transformation of precipitates in NiTi shape memory alloy. Acta Mater. 2024, 274, 119990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.J.; Wang, B.; Meng, X.L.; Gao, Z.Y. Texture evolution, microstructure, and superelastic properties of different cold-rolled Ti-Zr-Nb-Sn strain glass alloys. Mater. Charact. 2022, 193, 112309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitas, V.I. Phase-field theory for martensitic phase transformations at large strains. Int. J. Plast. 2013, 49, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakopoulos, M.; Connolley, T.; Reinhard, C.; Atwood, R.; Magdysyuk, O.; Vo, N.; Hart, M.; Connor, L.; Humphreys, B.; Howell, G.; et al. I12: The Joint Engineering, Environment and Processing (JEEP) beamline at Diamond Light Source. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2015, 22, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, D.S.; Donath, T.; Magdysyuk, O.; Bednarcik, J. High-energy X-ray applications: Current status and new opportunities. Powder. Diffr. 2017, 32, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.L.; Drakopoulos, M.; Reinhard, C.; Connolley, T. Complete elliptical ring geometry provides energy and instrument calibration for synchrotron-based two-dimensional X-ray diffraction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2013, 46, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basham, M.; Filik, J.; Wharmby, M.T.; Chang, P.C.Y.; El Kassaby, B.; Gerring, M.; Aishima, J.; Levik, K.; Pulford, B.C.A.; Sikharulidze, I.; et al. Data Analysis WorkbeNch (DAWN). J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2015, 22, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filik, J.; Ashton, A.W.; Chang, P.C.Y.; Chater, P.A.; Day, S.J.; Drakopoulos, M.; Gerring, M.W.; Hart, M.L.; Magdysyuk, O.V.; Michalik, S.; et al. Processing two-dimensional X-ray diffraction and small-angle scattering data in DAWN 2. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2017, 50, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, N.L.; James, I.C.; Martin, N.; Jones, N.G. The effect of heat treatment temperature on the mechanical properties of TIMETAL® 575. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 890, 145991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Hao, Y.L.; Nowak, S.; Gloriant, T.; Laheurte, P.; Prima, F. A thermo-mechanical treatment to improve the superelastic performances of biomedical Ti-26Nb and Ti-20Nb-6Zr (at.%) alloys. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2011, 4, 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, N.L.; Talbot, C.E.P.; Connor, L.; Michalik, S.; Jones, N.G. In Situ Studies of ɑ Evolution During Cyclic Testing of Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn. In Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Titanium (Ti-2023), Edinburgh, UK, 12–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Church, N.L.; Jones, N.G. The influence of stress on subsequent superelastic behaviour in Ti2448 (Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn, wt%). Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 833, 142530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.J.; Thibon, I.; Castany, P.; Gloriant, T. Effect of grain size on the recovery strain in a new Ti-20Zr-12Nb-2Sn superelastic alloy. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 793, 139878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Sasaki, T.; Okutsu, K.; Kim, J.I.; Inamura, T.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Texture and shape memory behavior of Ti-22Nb-6Ta alloy. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Chen, T.H.; Lin, C.F.; Luo, W.Z. Dynamic Mechanical Response of Biomedical 316L Stainless Steel as Function of Strain Rate and Temperature. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2011, 2011, 173782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamura, T.; Shimizu, R.; Kim, H.; Miyazaki, S.; Hosoda, H. Optimum rolling ratio for obtaining {001} < 110 > recrystallization texture in Ti–Nb–Al biomedical shape memory alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 61, 499–505. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.F.; Shang, X.K.; Hou, J.H.; Li, Y.Y.; He, B.B. Role of stress-induced martensite on damage behavior in a metastable β titanium alloy. Int. J. Plast. 2021, 142, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Tan, Y.; Hou, H.; Ren, G.; Wang, N.; Zhao, Y. Stress-Induced α″ Martensite and Its Variant Selection in a Metastable β Titanium Alloy under an Uniaxial Compression. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 1795–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, B.; Raabe, D. Texture inhomogeneity in a Ti–Nb-based β-titanium alloy after warm rolling and recrystallization. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 479, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, O.G.; Church, N.L.; Talbot, C.E.P.; Connor, L.; Michalik, S.; Jones, N.G. The degredation mechanism of Ti-Nb-Zr-Sn alloys during cyclic testing. In Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Titanium (Ti-2023), Edinburgh, UK, 12–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, D.S.; Wechsler, M.S.; Read, T.A. Cubic to Orthorhombic Diffusionless Phase Change-Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Aucd. J. Appl. Phys. 1955, 26, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.Z.; He, B.B. A Review on Deformation Mechanisms of Metastable β Titanium Alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 14981–15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Initial Thickness/mm | Final Thickness/mm | CR Ratio/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR50 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 50 |

| CR60 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 60 |

| CR70 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 70 |

| CR80 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 80 |

| CR90 | 7 | 0.7 | 90 |

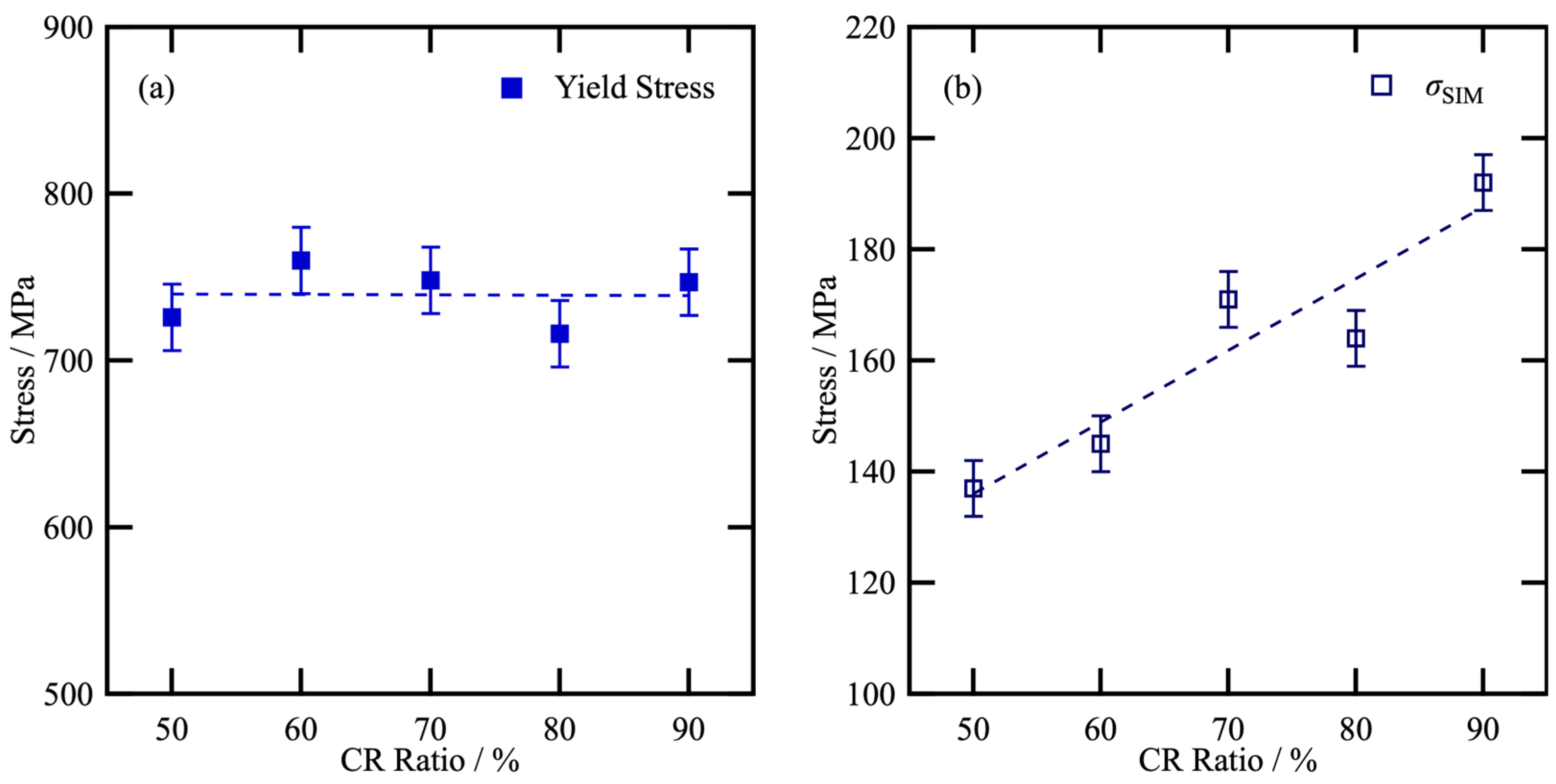

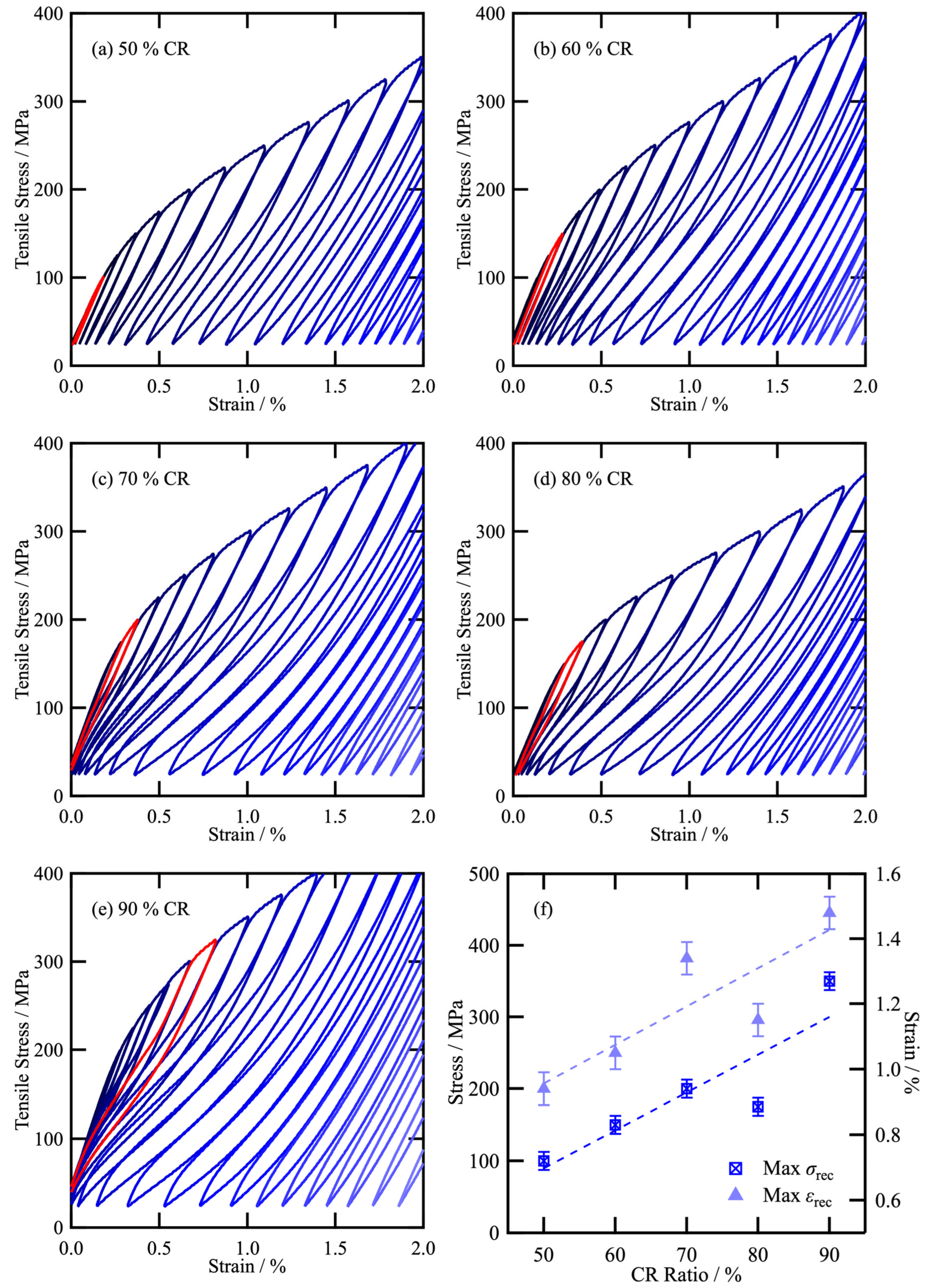

| Sample | σy/MPa | σSIM/MPa |

|---|---|---|

| CR50 | 726 | 137 |

| CR60 | 760 | 145 |

| CR70 | 748 | 171 |

| CR80 | 716 | 164 |

| CR90 | 747 | 192 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reed, O.G.; Desson, B.T.; Church, N.L.; Jones, N.G. The Effect of the Rolling Reduction Ratio on the Superelastic Properties of Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn (wt%). Metals 2025, 15, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121323

Reed OG, Desson BT, Church NL, Jones NG. The Effect of the Rolling Reduction Ratio on the Superelastic Properties of Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn (wt%). Metals. 2025; 15(12):1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121323

Chicago/Turabian StyleReed, Oliver G., Benjamin T. Desson, Nicole L. Church, and Nicholas G. Jones. 2025. "The Effect of the Rolling Reduction Ratio on the Superelastic Properties of Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn (wt%)" Metals 15, no. 12: 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121323

APA StyleReed, O. G., Desson, B. T., Church, N. L., & Jones, N. G. (2025). The Effect of the Rolling Reduction Ratio on the Superelastic Properties of Ti-24Nb-4Zr-8Sn (wt%). Metals, 15(12), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121323