Abstract

Grassroots and community-led initiatives are increasingly recognized as important actors of local development, yet their role of “local networkers” capable of co-designing and co-creating solutions remains insufficiently explored, particularly in post-socialist contexts. The aim of this empirical study is to evaluate the depth of participation and the patterns of co-design in the process of strategic planning in grassroots initiatives. The research draws on primary data from 106 grassroots initiatives. To examine stakeholder involvement, we construct six bipartite networks representing actor participation across distinct phases of strategic planning. These networks are analyzed using social network analysis to identify structural patterns, followed by exponential random graph models (ERGMs) to test hypotheses concerning actor-level characteristics such as income, commercial activities, community size, and experience with social innovation. The findings show that the core co-designers in all planning phases are the initiatives’ own communities and volunteers, who consistently dominate the planning, decision-making, and implementation processes. External actors—local governments, NGOs, activists, firms, and universities—participate selectively, mainly during initial information gathering, consultations, and project preparation. Overall, the study demonstrates that grassroots initiatives operate primarily as community-anchored civic networks, with external actors engaged pragmatically around specific collaborative tasks rather than across the full planning cycle.

1. Introduction

The realm of planning and policy-making has changed significantly in recent decades at the level of governments, but also in the conditions of individual development actors in territorial development. These shifts result from new planning paradigms anchored in more democratic and inclusive governance models [1]. Participatory planning is indeed not a new phenomenon—it has been developing since the 1960s, but in the last two decades it has acquired new contours, as the empowerment of local communities led to the emergence of the phenomenon of participatory plan “co-design” [2,3].

In the case of Western European countries, models of sub-local development planning have been tested for years at the level of communities that are actively involved in the creation of territorial strategic plans [4,5]. In such a case, local communities are represented by formal institutions (e.g., NGOs, community forums, neighborhood councils). In the case of the post-socialist countries of Europe, patterns of participation within spatial development planning are less intensively mapped. Results of research in the region suggest that participatory planning in post-socialist countries is still characterized by tokenism, or a low level of empowerment of actors participating in planning in the context of Arnstein’s [6] ladder [7]. It remains questionable as to what extent active local communities are involved and empowered to intervene within local development planning in V4 countries [8]. Strategic planning in the Visegrad Group (V4) countries, which include Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, exhibits varying levels of public involvement in strategic development planning. Local development plans in the region tend to be drafted with limited public involvement, which can be attributed to several factors, including the low administrative capacity of municipalities, a lack of trust and a missing tradition of participation, weak methodological support, or the politicization of decision-making processes [9,10].

The research results suggest that grassroots initiatives usually utilize approaches of co-management, co-creation, and the co-design of solutions [11,12]. These assumptions lead to the hypothesis that community-led grassroots initiatives can be a significant source of knowledge and know-how in the fields of participation management, the co-design of strategic plans, or the co-creation of innovative solutions addressing local needs [13].

In line with propositions for further research by several authors [11,14,15,16], our intention is to verify the assumptions of a high level of participation in the creation of strategic plans in grassroots initiatives and to investigate the role of “local networker” that these active local communities can play in local development. The main aim of the study is therefore to evaluate the depth of participation and the patterns of co-design in the process of strategic planning in active local grassroots communities. The expectation that grassroots communities can be considered as a source of lessons learned in the fields of co-design and the co-deployment of solutions within broad networks with other spatial actors will be examined. The depth of participation of the local community and external actors will be investigated within the individual phases of the planning process, whereas, to the best of our knowledge, the tendency to involve different actors in different planning phases [17] has not yet been analytically evaluated even in spatial planning studies. The following research questions arise:

- Q1: To what extant are the community-led initiatives a source of good practice in co-designing strategic plans?

- Q2: What position does the initiative’s own grassroots community occupy in the co-design process of strategic planning?

- Q3: What role do grassroots initiatives play in shaping networks or social clusters generating innovative solutions for local development?

2. Theory Background

The research framework for this empirical study draws on the concept of the urban commons, rooted in the work of Elinor Ostrom [18], which refers to shared resources collectively managed by a community through a common governance system. The term commoning denotes the collective practice through which local resources, capacities, and knowledge are pooled, exchanged, or, in some cases, collectively commodified [19]. Within urban development studies, urban commons are closely related to the concept of common-resource pooling [20], which can be utilized by various grassroots initiatives as a tool for the collective steering of local development and community-led change. These approaches emerge against the traditional urbandevelopment models that were historically based on the interplay between market mechanisms and public policy interventions [21]. In addition to public policy interventions, local community-led initiatives may also address market failures through projects that prioritize shared use and collaborative practices over individual ownership [11]. The interventions of community-led grassroots initiatives, such as urban farming, community gardens, repair cafés, community kitchens, or charity shops [22,23,24], demonstrate the capacity of local communities to identify new solutions through trial-and-error processes and to implement social innovations that have the nature of a commons [25]. The governance of these commons, however, requires substantial capacity building within local communities, including their ability to co-design, co-deploy, and co-manage solutions. Given the growing volume of community-led actions observable in local development in the twenty-first century, there is a clear demand for empirical insights into how grassroots communities participate in co-designing solutions within shared planning processes [26].

A participatory approach to the creation of strategic plans has been developing, mainly in the conditions of the Western world, since the 1960s. The term “participatory planning” is usually understood as the collaborative involvement of participants in the decision-making processes [27], while the participation of future users of planned interventions in the creation of the plan should support the setting of development goals and increase the value of development programs by the better optimization of these goals towards the perceived needs [28]. While in the conditions of some Western European countries, one can talk about the important roles of neighborhood or grassroots communities in the creation of local development plans [4,5,29], in the conditions of the post-socialist countries of Europe, participatory planning in local and regional development is still characterized by tokenism [7]. Tokenism in local and territorial strategic planning refers to situations where public participation is formally present but has no real influence on decision-making. It represents the symbolic involvement of stakeholders, serving more to legitimize already-made decisions than to enable the genuine co-creation of strategies [30].

Arnstein [6] already outlined in her “Ladder of participation” that the level of community empowerment in planning can vary significantly. The ability of actors within different types of communities to identify solutions and implement them collaboratively led to the development of frameworks and methodologies of co-design, co-creation, and co-deployment in strategic planning [4,31]. The co-design of strategic plans refers to the process through which local communities are invited not only to provide their views and expectations, comments, and suggestions in planning process, but to use their own creativity, knowledge, and skills for active plan preparation and the delivery of solutions [32]. The co-designing of strategic plans was observed especially in the conditions of urban development studies, in which the high level of engagement of civic platforms, active communities of interest, and the communities of marginalized residents in the creation of plans is usually associated with expectations of strengthening social cohesion in the local community, generating social capital, and creating just and sustainable responses to local challenges [33]. The creation of solutions based on the principle of co-design and co-creation is significantly supported by the development of novel, digital tools for joint communication and joint decision-making [3] that are available to development actors today.

“Grassroots” is considered to be a polysematic term that Seyfang and Smith [11] use to describe “the networks of activists and organizations generating novel bottom–up solutions for sustainable development; solutions that respond to the local situation and the interests and values of the communities involved”. In the literature, it has a kind of bi-focal understanding—in the form of a network of actors or pro-active civil organizations [12], at the same time as it refers to innovative solutions addressing social challenges that arise in the process of co-creation [13]. The idea that the success of grassroots communities stems from co-design and the co-deployment of solutions is indeed not new [12,16,34], but patterns of participatory planning in the conditions of community-led grassroots organizations have not yet been sufficiently mapped [35]. Still, it is most often assumed that the source of co-creation of solutions in community-led organizations is the “community”. The community can be an important source of financial capital, human capital, knowledge, and social capital for grassroots [36]; thus, we hypothesize that this capital becomes an input in both co-design and the co-deployment of solutions.

At the same time, the grassroots literature also provides justification for the involvement of external actors in the planning or deployment of citizen-led solutions. To a certain extent, the joint creation of solutions between active civic platforms and external actors in the territory can be seen as expected, given the fact that the eminent interest of grassroots innovators and social movements is to contribute to the solution of challenges perceived by various spatial actors [5,37]. Therefore, we further hypothesize that grassroots initiatives form rich cross-sector ties during the creation of strategic plans and involve external actors in both co-design and the co-deployment of planned solutions. The research hypotheses are formulated in accordance with the expectations that some types of actors are invited to the planning process only in selected phases of the planning cycle [38]. To better specify the potential phases of planning cycle, Slave et al. [17], we will differentiate the depths of participation in the cases of six planning stages: (1) pre-planning consultations, (2) gathering information, (3) gathering projects, (4) plan preparation, (5) plan approval, and (6) plan implementation. Due to the extensive gaps in the literature in this context, however, we cannot build hypotheses on the involvement of individual types of actors within the individual stages of the participatory planning cycle in line with the existing literature. Hypotheses demand theoretical justification for “what, how, why, who, where, and when” in the context of the tested assumption [39]. However, when the literature provides very sparse answers, some authors—e.g., Grosof and Sardy [40]—underscore the validity of using exploratory pre-research results to build hypotheses for phenomena not previously addressed in the existing literature. Our assumptions are formulated in accordance with the results of focus groups conducted with the representatives of 15 important grassroots initiatives located in Slovakia, which can be considered as a form of proof-of-concept initial pre-research. The following hypotheses emerged from the results:

H1.

Within the evaluated planning phases, I–III, there is the highest chance of grassroots initiatives including the local government in the planning process.

H2.

In phases IV–VI of the planning process, grassroots initiatives primarily include their own community.

The authors do not know about any analyses of drivers enabling the higher level of participation “depth” in the case of planning in community-led organization. However, it is generally accepted that increasing the level of participation in planning is limited by the availability of resources, especially financial resources [41]. In addition to the availability of resources, the planning of grassroots initiatives could be differentiated depending on the accumulation of experience, successfully implemented projects, and their ability to innovate, and depending on the overall degree of professionalization of the management of the organization [12,13]. We therefore hypothesize the following:

H4.

There is a positive relationship between initiative revenue growth and planning participation rates in Phases III and IV.

H5.

There is a positive relationship between the fact that the initiative has already introduced social innovation (SI) into the product or service and the level of participation in planning in phases III and IV.

H6.

There is a positive relationship between the commercialization of initiative activities and the level of planning participation in phases III and IV.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Data

The empirical study is based on the use of primary data obtained from the survey “Monitor of innovative communities in the Slovak Republic”, which was initiated by the authors and was implemented throughout the Slovak Republic and was implemented throughout the Slovak Republic. The sampling strategy followed a two-stage design combining purposive criterion-based sampling with snowball sampling. In the first stage, we aimed to identify potential grassroots initiatives within third-sector organizations. To achieve this, we manually screened more than 22,000 third-sector actors listed in the Register of Institutional Subjects of the Slovak Republic. Each organization was examined using secondary data available from public registries, official websites, and publicly accessible descriptions of activities. Grassroots initiatives were identified based on three predefined criteria:

- their declared activities addressed social, environmental, cultural, or economic issues relevant to local communities or the wider society;

- the organization explicitly described itself as community-led, or referred to an active community of supporters; and

- their mission and activities indicated the potential to generate social innovations, which led us to exclude conventional organizations such as sports clubs, hobby associations, collectors’ groups, or professional unions (this represents a deliberate design boundary of the study, reflecting the decision to focus specifically on community-led initiatives that explicitly identify themselves as such).

This stringent filtering process resulted in a core sample of 462 third-sector organizations that could be reliably classified as grassroots initiatives. In the second stage, we employed snowball sampling to capture additional grassroots actors that are often absent from formal registries (e.g., informal citizen groups and community-based initiatives operating within public institutions). Representatives of the initially identified 462 initiatives were invited to recommend other community-led actors with whom they cooperate or about whom they possess relevant knowledge. Through this chain-referral process, we identified an additional 40 initiatives, expanding the sample to include both registered and non-registered grassroots actors. To minimize the potential bias inherent to snowball sampling, we combined several sampling techniques and began with purposive sampling. We constructed a broad and highly diversified list of grassroots initiatives through purposive sampling, which ensured that referrals would not originate from a homogeneous group of initiatives. During recruitment, we continuously monitored whether referrals introduced new types of grassroots actors, particularly informal or non-registered initiatives. A total of 502 grassroots initiatives were approached, of which 106 participated in the research. In the case of 89 of them, it was possible to conduct mass guided interviews, while the remaining 17 provided their attitudes through completed questionnaires with comprehensive open answers. The questionnaire and the framework for mass interviews were pre-tested with 15 grassroots initiatives. These pilot consultations, conducted in the form of short focus groups, provided essential empirical insights that informed the refinement of the research instruments and supported the formulation of several study hypotheses. Representatives of the grassroots initiatives involved in the pre-testing stage also drew on their own practical experience to indicate in which phases specific actor groups tend to be engaged and which stages of the planning cycle might be influenced by particular determinants, thereby contributing directly to the conceptual grounding of the hypotheses.

To assess the representativeness of the sample (Table 1), 502 identified grassroots initiatives were considered the population, as they include not only entities identified through a systematic review of available databases, but also initiatives obtained via the snowball method. This set therefore represents the most complete identifiable scope of active grassroots initiatives in Slovakia. The research sample represents 21.12% of the population. From the perspective of the regional distribution of the population, the Bratislava Region holds a dominant position in the sample. As the most developed region of Slovakia, this aligns with the expectation that grassroots initiatives emerge more frequently in highly urbanized environments. The sample is broadly similar to the population in terms of regional distribution. Most of the regions are represented at proportions close to their population shares. Slight deviations are present in the case of Nitra and Žilina. While Nitra is overrepresented, Žilina appears to be slightly underrepresented. In the case of urban–rural composition, the sample contains more rural initiatives compared to the population.

Table 1.

Representativeness of the sample.

In this study, “depth of participation” is operationalized via social network analysis as the presence of ties between grassroots initiatives and stakeholders, signifying the involvement of the given stakeholder in a specific step of the planning process. By measuring the presence of ties, stakeholders who participate in and influence the planning activities are revealed; therefore, the more ties that exist between the grassroots initiative and various stakeholders, the greater the depth of participation that the initiative has in the planning process. To understand “participation depth” in grassroots strategic planning, we employed a two-step approach. First, we utilized social network analysis metrics and visualizations to identify general patterns of stakeholder involvement. This step allowed us to reveal broad patterns of participation, such as the centrality of key stakeholders and the overall density of the network. In the second step, we applied exponential random graph models (ERGMs) to systematically examine the factors shaping the involvement of stakeholders in the planning process. SNA findings provided insights for the selection of the ERGM variables, mainly to account for the skewed degree distribution and central position of certain types of stakeholders.

3.2. Social Network Analysis

We utilized social network analysis methods [42,43] to conceptualize each phase of the planning process as a network of grassroots initiatives and potentially involved stakeholders. Survey data regarding the involvement of stakeholders in the planning process was transformed into six n × m matrices, each representing one phase of the planning process. Each network consisted of n grassroots initiatives and m types of stakeholders. In the case of the involvement of the relevant type of stakeholder by the given initiative, the value was set to 1, otherwise it was set to 0. These matrices represent two-mode or bipartite networks. These are specific types of networks, as they contain two distinctive types of nodes. A tie can only exist for two nodes of different types, which affects the metrics of such networks and sets constraints for modeling the existence of such ties. Due to the nature of the networks, ties were treated as undirected.

A stakeholder involvement in the six phases of the planning process of grassroots initiatives is presented within separate networks. Undirected edges indicate the involvement of a specific type of stakeholder in the given grassroots initiative planning process phase. The size of the nodes represents degree (number of ties). The number of sides of the grassroots initiatives polygons represents the highest spatial level of its activities, with more sides reflecting a higher spatial level. In order to visualize the networks, we utilized the Gephi 0.10.1. The Force Atlas algorithm was applied to determine the node layout. High-degree nodes are placed in the center, and nodes with few ties are pushed to the periphery of the graph [44]. This visualization helped to identify the distinguishing structural features of the studied networks.

3.3. Econometric Analysis

The interdependencies in network data violate the assumption of the independence of the observations (in this case, the tie formation depends on grassroots initiatives, types of stakeholders, and their ties to others), and thus standard regression analysis is not suitable [45]. Exponential random graph models (ERGMs) address the limitations of traditional regression analysis—the assumption of independence between network ties is not required and they allow for the probability of a tie to depend on the presence or absence of other ties in the network [46]. We utilized ERGMs in order to reveal factors that influence the involvement of various types of stakeholders in specific phases of the grassroots initiative planning process.

ERGMs are the class of statistical models for relational data that model the structure of networks. This method allows for the combination of structural variables, actor characteristics, and additional variables (e.g., covariate matrices) into a single model [47]. In this case, each of the planning phase networks is conceptualized as an observed realization of a set of possible networks, given the fixed set of nodes. Model parameters reflect social processes important in the process of network formation. ERGMs are able to deal with data structured as bipartite networks if the variables are set appropriately [46].

Exponential random graph models have the following general form [48]:

where x is the studied network, understood as a single realization of all possible permutations X of the given network, zj(x) is the vector of network configurations (representing network sub-structures or actor characteristics), θi are their corresponding parameters, and k(θ) is a normalizing constant, representing the numerator value for all possible networks with a given number of nodes and ensuring that the probability is correctly defined, as it ensures a proper probability distribution. The coefficients of resulting models can be interpreted in a manner similar to those of logistic regression models. Significant network configurations significantly affect the observed network structure, with positive (negative) values meaning that their occurrence is more (less) likely than chance. The parameters of models incorporating local network configurations can be estimated by utilizing Markov chain Monte Carlo maximum likelihood estimation (MCMC MLE), in which, in an iterative process, a simulated distribution of random graphs is compared to observed data and parameter values are refined [44].

As the model (1) indicates, network structure is modeled via several types of factors—both endogenous (sub-structures of the studied network) and exogenous (actor- or dyad-specific characteristics) [46]. Network ties are interdependent and can result in a variety of local network configurations (subgraphs contained in the networks) [49]. These are considered to reflect social processes in the network, such as reciprocity or triples of interconnected actors, which form the foundations of clusters in the network. The whole network consists of these local configurations or “network statistics”. In the model, these factors are functions of the ties themselves and are hypothesized to occur more or less often than expected in a random network [50]. It is important to note that, in the case of structural variables, we only observe their presence, and we cannot say with certainty (we can only hypothesize) what caused the structure observed in the network [51].

Since network ties connect dyads of actors, their formation may be influenced by actor-specific characteristics. In the model utilizing bipartite network data, these effects are commonly expressed as sender or receiver effects [52]. For example, grassroots initiatives with specific levels of attributes may be more prone to involve stakeholders in the planning process. The variables utilized as actor covariate effects are described in Table 2. In Appendix A, an overview of the descriptive characteristics of the quantified data obtained from the guided interviews and the questionnaire survey is provided. Utilized structural and actor covariate effects are described in more detail in Table 3. In the table, the various types of effects are accompanied by their graphic representation.

Table 2.

Operationalization of variables.

Incorporating certain endogenous network statistics may lead to degeneracy issues in the models (the model produces an empty graph or a complete graph) [51], leading to convergence problems in the estimation algorithms. In the case of activity spread of grassroots initiatives, we address the degeneracy issues by utilizing the geometrically weighted term gwb1degree [50,53,54]. In the final models, the decay parameter of this term was set at 0.25 to moderately down-weight high-degree nodes and avoid overemphasizing star-like structures [55].

Estimation was performed in R using the ergm 4 function from the statnet package. The ERGM was estimated using MCMLE with the default MCMC settings: burn-in of 8192 and sampling interval of 256. The maximum number of MCMLE iterations was 60. Model convergence was evaluated using MCMC diagnostics, to ensure adequate mixing of the Markov chains. Goodness-of-fit checks were used to assess how well the model reproduced the key structural features of the observed network. Original properties of the analyzed networks were compared to 1000 networks simulated using estimated parameters. The goodness-of-fit assessment was performed using the btergm package in R 4.5.2 [56].

Table 3.

Structural and actor covariate effects included in the model.

Table 3.

Structural and actor covariate effects included in the model.

| Edges | The number of existing ties. It reflects the baseline probability of tie formation, controls network density, and conceptually corresponds to an intercept term in a linear regression model. The effect was operationalized using the edges model term. |  |

| Activity spread of grassroots initiatives | The term captures an “activity effect” or centralization of the network. It is manifested by unequally distributed degrees of nodes. In the case of a skewed distribution, the network comprises a core of highly centralized actors and a periphery of actors with little or no ties. As demonstrated by Levy [57], a negative coefficient indicates a positive effect of centralization. In addition, this statistic is used for model convergence purposes [58]. The effect was operationalized using the gwb1degree model term. Rather than counting all degree levels separately, this term summarizes the overall shape of the degree distribution using a decay parameter. This allows the model to represent centralization patterns without overfitting. Including this term also improves model stability when networks exhibit a strongly skewed degree distribution. |  |

| Actor covariate effects | ||

| Social innovator | The tendencies of grassroots initiatives with a certain categorical attribute to involve stakeholders in a phase of a planning process. The effect was operationalized using the b1factor model term. |  |

| Engages in commercial activities | ||

| Involvement in LDP | ||

| Involvement in the creation of central policy | ||

| Rurality | ||

| Strategic planning | ||

| Community size | The tendencies of grassroots initiatives with high (low) levels of a quantitative attribute to involve stakeholders in a phase of a planning process. The effect was operationalized using the b1cov model term. |  |

| Average annual income for the last 5 years | ||

| Age | ||

| Employees | ||

| Highest spatial level of activity | ||

| Degree of goal achievement | ||

| Length of the planning period | ||

| Stakeholder | The tendencies of various types of stakeholders to be involved in a phase of a planning process of a grassroots initiative. The effect was operationalized using the b2factor model term. |  |

Note: Grassroots initiatives are represented by circles and stakeholder types by squares.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Social Network Analysis

As we already explained in the Section 3, our investigation is based on data from 106 grassroots communities and their initiatives, which took on different legal forms. More specifically, up to 86% of these community-led initiatives were established in the non-profit sector. The spatial distribution of the grassroots initiatives in our sample copies the spatial distribution of the population—the overconcentration of grassroots communities can be observed in the capital of Bratislava and the center of eastern Slovakia—Košice—or in other significant growth poles within the country. Up to 19 of the 106 grassroots initiatives in our sample are located in small rural settlements in all regions of Slovakia. The distribution of the grassroots initiatives by legal form and the type of impact on local development is provided in Appendix A. In the sample, formal organizations dominate in terms of legal forms, particularly civil associations, interest groups, and non-profit organizations. Approximately 10% consist of informal citizens’ associations or informal cross-sector platforms. Around half of the informal groups are environmental social movements. Thirteen initiatives are defined as partnerships. A variety of impacts on local development were identified across the initiatives. In several cases, the impact on the creation of physical infrastructure was also identifiable, although these were usually “soft” solutions. The most common activities focused on environmental development, the development of culture, arts, and sports, as well as community development, networking, and the development of participation.

The formation of grassroots communities is a common occurrence even in the conditions of a post-socialist country, as grassroots communities arise naturally in countries with a democratic constitution, along with the development of civic society. In the conditions of Slovakia, such bottom-up initiatives already have a certain tradition—this is evidenced by the average age of the initiatives, at the level of 11 years. In order to emphasize the importance of grassroots initiatives for the development of national or, especially, local economies, only 106 initiatives in our sample employed up to 754 employees in 2022 (including seasonal ones), created their own communities of interest including a total of 12,827 residents and 6245 citizens, and provided them with voluntary work. Direct economic effects (direct expenses in the economy) reached the amount of EUR 11,835,747, while up to 66% of these expenses stayed in the local economy.

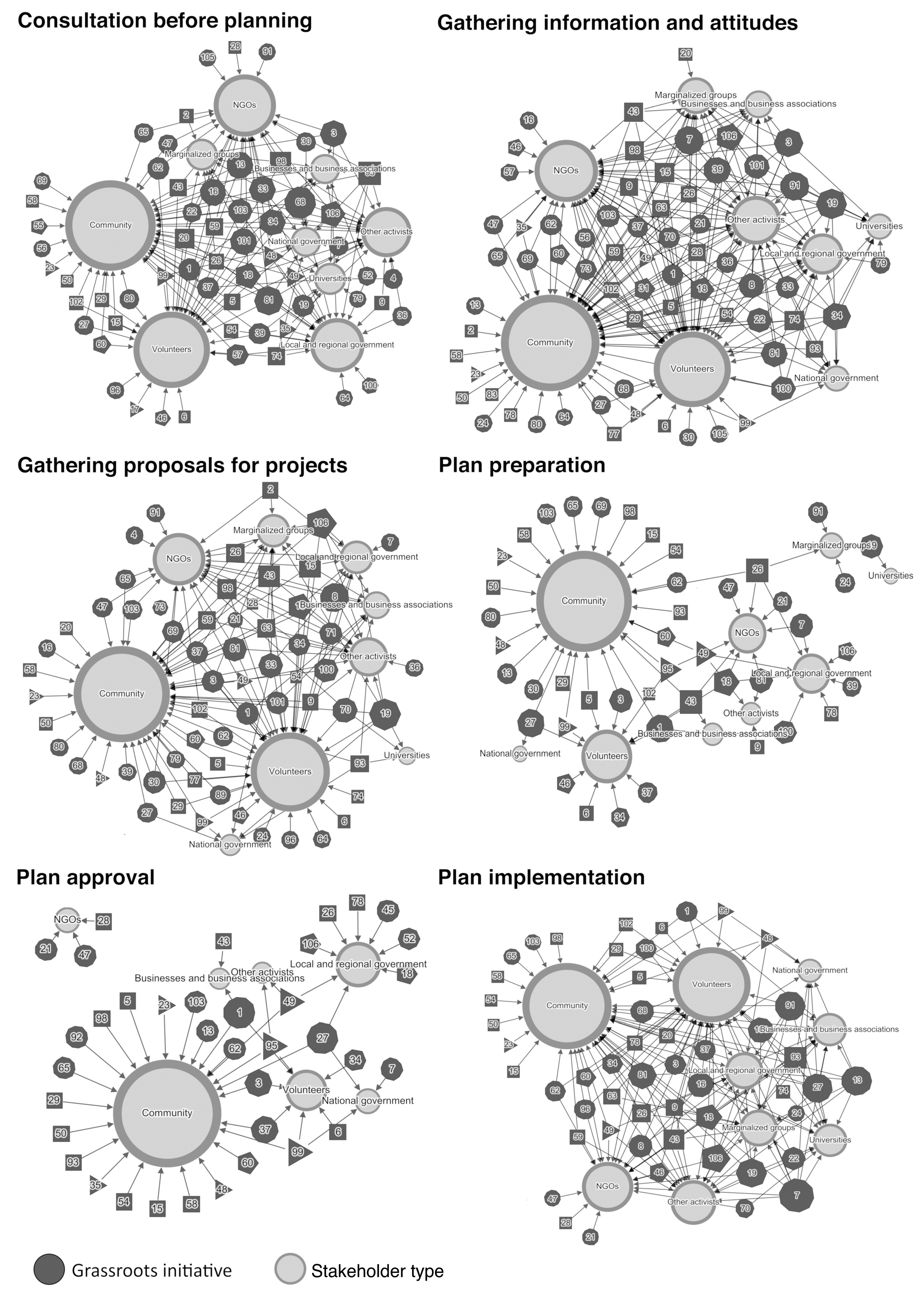

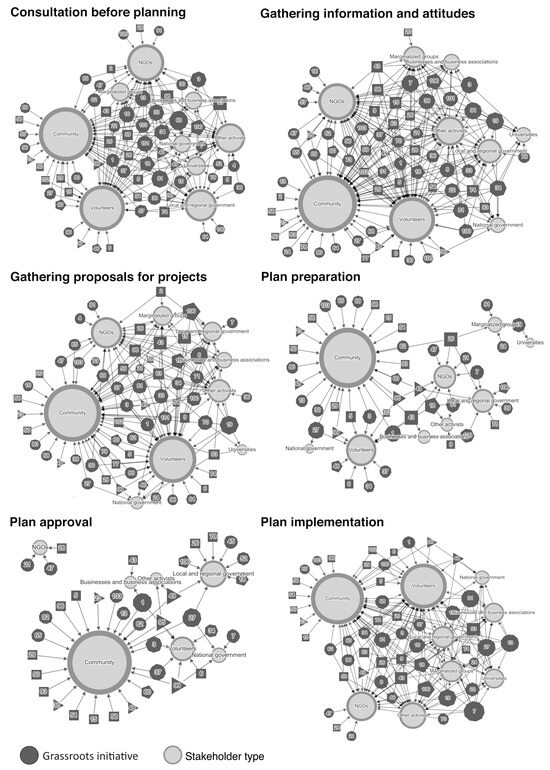

Grassroots initiatives vary widely in terms of applied planning models. We also identified differences between the researched grassroots initiatives in terms of the degree of involvement of external stakeholders in the planning process. Table 4 contains descriptive statistics of the six bipartite networks. Figure 1 depicts visualized networks of stakeholder involvement in the six phases of the planning process. Stakeholders were involved mainly in the initial stages of the planning processes and subsequently during the implementation of the plan, which is shown by the relatively higher values of network density. On the contrary, they were least involved in the processes of plan approval and plan preparation. The density of the first three networks reflects the collaborative nature of the early stages of planning, as initiatives gather input from a broad spectrum of various actors, who can provide information, expertise, resources, and legitimacy. In the plan preparation and approval stages, the low density reflects a more focused process, where decisions are made by a smaller group of key stakeholders.

Table 4.

Network-level descriptive statistics.

Figure 1.

Visualization of involvement in the phases of planning process networks. Note: The size of nodes represents degree [number of ties]; polygon sides reflect the highest spatial level of activity. Isolates are not shown but are included in the analysis.

In the individual networks, we observed different variations in the degree distribution of both grassroots initiatives (variability in the number of types of stakeholders they involved) and stakeholders (variability in the involvement of individual types of stakeholders). In the case of the grassroots initiatives’ degree, the variation was relatively high in all of the networks. At the same time, the median degree was low, even zero in the case of the last three networks. This indicates the presence of a group of centrally positioned high-degree initiatives and, at the same time, a large number of peripheral actors with a very limited level of stakeholder involvement. In the case of low-density networks, this mainly indicates a different rate of involving “any” type of stakeholder in the given planning phase, evident in the relatively high isolate rates. This is clearly shown in the visualization, as, in the networks of higher density, we observe numerous groups of actors with a central position, who involve a relatively wide spectrum of stakeholders. In the low-density networks, the choice of stakeholder involvement is often reduced to one type of stakeholder and initiatives with multiple ties are almost non-existent.

A variation in the degree distribution is also apparent in the case of individual types of stakeholders, and the visualization shows different degrees of their involvement. It is evident that, in all networks, the community and volunteers are primarily involved. This finding corresponds to our initial assumption that communities and volunteers are the main source of co-design practices within the planning processes of grassroots initiatives. In the context of H2, which proposes the involvement of the community mainly in the last three phases, the dominant position of the community is evident and goes beyond these three phases. In the case of the majority of the investigated grassroots initiatives, the local community was an important player in every phase of the planning process. It is also important to note that up to 37% of the grassroots initiatives empowered their community to be directly involved in the creation of the text of the plan and the formulation of the intervention logic, and 35% of grassroots initiatives even let community members vote on the plan’s approval. The volunteers (understood as a certain subset of the community) were empowered to act in the co-design of the plan similarly to communities, but we clearly see that the “approval of the plan” is part of the competence of the assembly of the “community”, which volunteers may or may not be a part of.

In contrast, ties to institutional actors such as local and regional governments, business associations, and universities appear to be more selective, with only a subset of initiatives engaging them at each stage. However, noticeable differences can be observed across the individual phases. A slightly higher involvement of these stakeholders is visible in the first three networks as well as in the plan implementation phase, though these are denser networks, making it difficult to identify the targeted involvement of these actors. It is important to note that the plan approval network does not contain ties with universities nor with marginalized groups. In the case of this network, these stakeholder nodes were removed, in order to proceed with the ERGM analysis in subsequent stages. In the context of H1, which expects that, in phases I–III, grassroots initiatives are most likely to include the local government, it is evident that while local and regional governments are not dominant actors, they maintain a stable position that persists in these three phases as well as in the other networks.

The participation of specific types of external actors is determined by the structure of the planned projects. As many as 29 of the 68 grassroots initiatives creating the strategic plan declared that the majority of solutions (in terms of provided products, services, realized infrastructure, interventions in the landscape, and mobiliar, etc.) are based on collaborative projects. Therefore, we hypothesize that the structure of the actors involved in planning changes dynamically and adapts to the needs of the informing authorities, such as obtaining permits, securing resources from other actors, and social capital for projects, which grassroots initiatives would often not be able to implement on their own. This hypothesis is also reflected in the high level of involvement of actors from other sectors in the process of implementing strategies. Thus, grassroots communities can potentially be considered as a form of social innovation cluster. This bold claim can again be supported by the information that up to 43 of the 106 researched grassroots initiatives produced a total of 63 social innovations between 2019 and 2022.

Although this analysis provided us with insights into the general patterns of the networks, in the context of the formulated hypotheses, it does not allow us to uncover the impact of the relevant factors on stakeholder involvement in the planning process. However, these descriptive patterns laid the foundation for the subsequent ERGM analysis, which we used to systematically examine the underlying factors influencing these participation patterns.

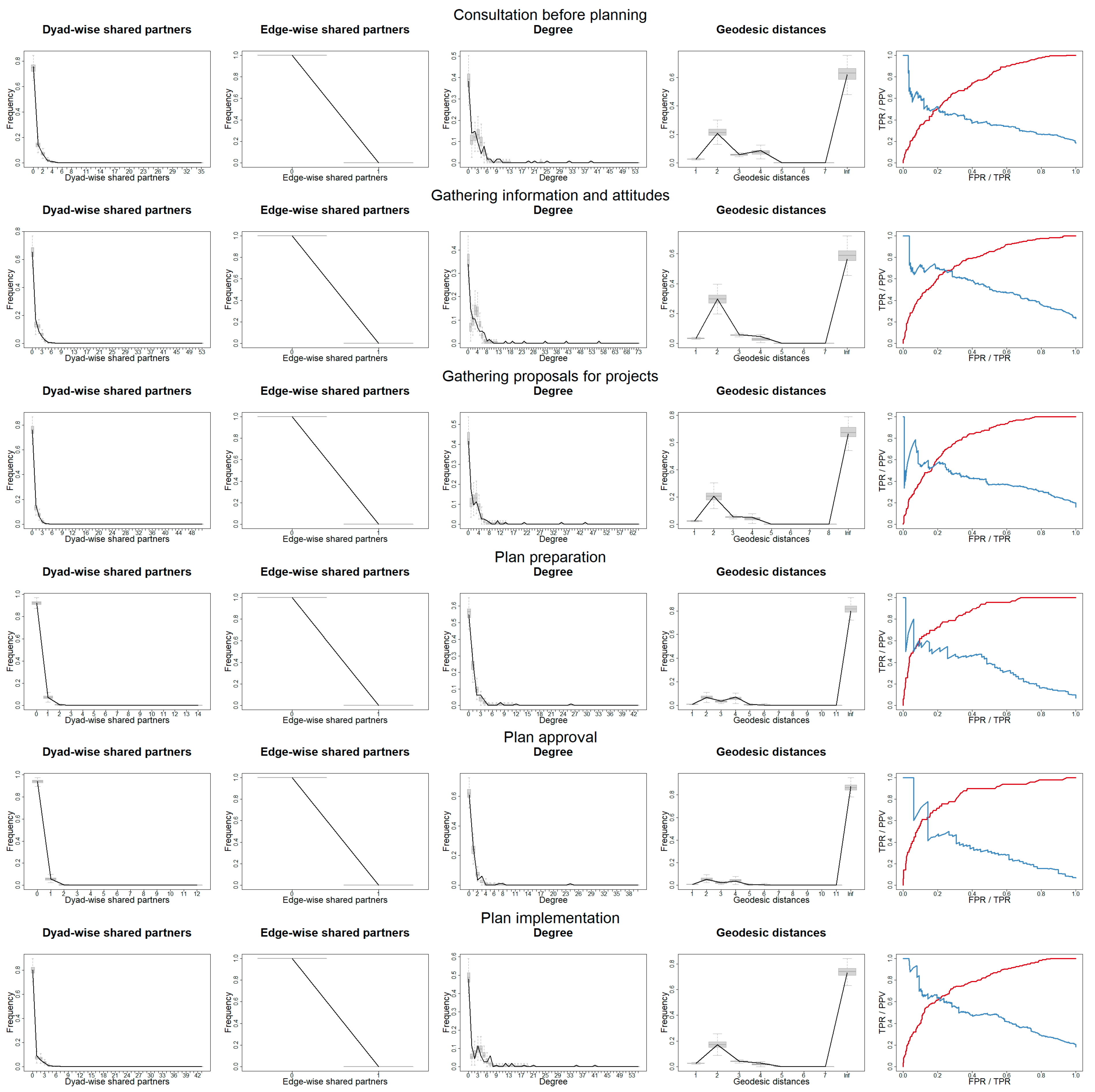

4.2. The Results of ERGM Analysis

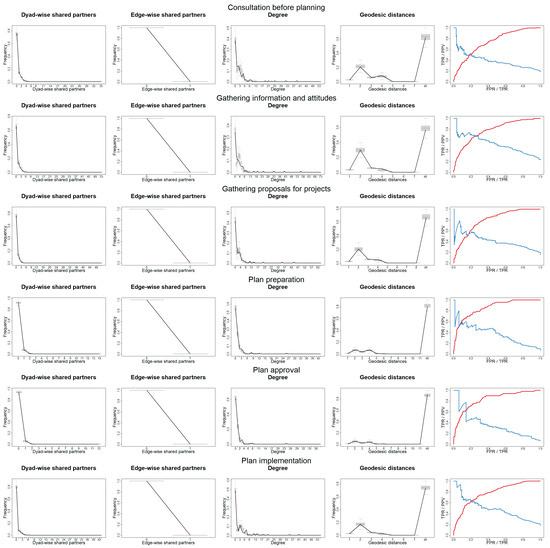

Figure 2 shows the model’s goodness-of-fit assessments based on 1000 simulations. Due to the bipartite nature of the networks, the following properties were compared: dyad-wise shared partners, edge-wise shared partners, degree, and geodesic distance. The assessments show that the values of the observed networks fall within the simulated network boxplots; thus, they fit the simulated networks. In addition to the comparison with simulated networks, we utilized receiver-operating curves. ROC curves indicate relatively good model performance. The results of the ERGM analysis are shown in Table 5. The included joint p-values indicate that the Markov chains are centered on the observed statistics and that the models are not showing signs of poor fit or degeneracy. p-values for individual model terms from the last round of the simulations are provided in Appendix A.

Figure 2.

Goodness-of-fit plots for ERGMs. Source: Authors’ own processing using the btergm package in R.

Table 5.

Results of the ERGM analysis.

Each of the models (I–VI) represents a specific phase of the grassroots initiative planning process. A single model represents a network of stakeholder involvement in a specific planning phase and the associated covariates of interest (grassroots characteristics, stakeholder characteristics, and structural variables) explaining the structure of a given network. At the network tie level (a grassroots initiative–stakeholder dyad), the model explains the probability of a tie being present (a stakeholder is involved) given the covariates and their associated coefficients (hereafter referred to as “participation propensity”). Our intention is to evaluate how the parameters of the model affect the degree of participation in individual planning phases.

First, we evaluated the “popularity” of individual types of stakeholders, which represent the tendencies of various types of stakeholders to be involved in a phase of a planning process of a grassroots initiative. The degree of individual actor involvement in the process of strategic planning could be better understood through these results. The key step for obtaining figurative, well-comparable results was the choice of a basic cooperating actor in the planning process. Both the literature [15,37] and the managers of the grassroots initiatives involved in the pre-testing of the research pointed out the extraordinary importance of the cooperation of grassroots initiatives with municipalities as local policy-makers. We proceed from the assumption that the frequency of cooperation with the local government is significantly high, especially in the planning phases, which we refer to as I–III. The activities of the grassroots initiatives implemented in public space, or implemented with financial support from the local government, often require providing the local government with information during the planning on whether to obtain a relatively wide range of permits from self-government authorities. Therefore, we arbitrarily decided to denote local self-government as the basic type of actor for the analysis.

However, the results showed that the local government is not a key partner, even in the initial stages of the participatory planning process. We reject hypothesis H1, as there is a significantly higher chance that, even in phases I–III, grassroots initiatives will primarily involve their own community. On the other hand, however, we accept hypothesis H2, as it has been proven that grassroots initiatives indeed most often involve their own community in planning phases IV–VI. Thus, grassroots initiatives’ own communities play a key role in the entire planning process, as they can play the role of planner, approver, and implementer at the same time. At the same time, these assumptions are also confirmed by the fact that in the case of volunteers, who represent one of the components of the “own community” of grassroots initiatives, there is a higher chance that they will be involved in the individual stages of planning as compared to self-government. This does not apply only in the case of the “plan approval” phase (V), as the initiatives provide this privilege to the community with all its components rather than to the volunteers “in particular”.

We provide the model results in Table 5 and the post-estimation diagnostics in Table 6. The position of the local government in the network of cooperating actors within strategic planning is still relatively significant. With the exception of the local community, self-government is most often involved in the approval of the plan. Based on the attitudes of the respondents during the guided interviews, it can be added that representatives of local governments are often invited for the plan approval process, mainly because of the need to “legitimize” the goals and planned projects of grassroots communities. In the case that there are no conflicts between the initiative and authorities of the local government, the initiative tries to build close, informal, and inter-personal ties with self-government representatives. In addition to the local government, other non-profit organizations are significantly involved in the creation of the strategic plan among external actors, except for the project approval phase. Grassroots also develop joint projects with individual activists from the external environment, when these activists take over the roles of coordinators of individual activities or provide grassroots with various services (e.g., the creation of site-specific works, production of graphics, and leadership in educational activities, etc.). This temporary cooperation mainly leads to their one-time-only involvement in the planning process—especially during the information and project gathering stages or, naturally, in the implementation stage. The state administration or private and academic sector actors generally participate in the planning of grassroots initiatives to a lower extent than local governments do. However, it turns out that cooperation with enterprises and universities is developing, mainly during the implementation of joint projects (especially the Horizon 2020 scheme), but the inclusion of private ventures and experts from universities in the early stages of planning is rather atypical.

Table 6.

Results of the post-estimation diagnostics.

Further elaboration of actor covariate effects allowed us to evaluate how different organizational and managerial attributes on the level of grassroots initiatives affect the degree of participation in individual planning stages (the tendency to include the community and external actors). Based on the literature, a set of observed and control parameters was included in the model. Conceptually, we distinguish three groups of investigated observed variables, namely (1) the effect of the growth of the initiative’s community, (2) the effects of income growth and the development of commercial and professional activities, and (3) the effect of accumulated experience within spatial planning, on the growth of the participation depth within the creation of one’s own strategic plans.

Our assumption that grassroots initiatives that are “larger” in terms of the size of their own community will have a higher level of participation was only partially supported by results. The growth of community size has a positive and statistically significant effect only on the level of participation in the phase of preparing the draft plan (IV). Grassroots initiatives therefore need to involve a wider spectrum of actors in the later phases of plan preparation. Our assumption turned out to be only partially justified; therefore, we reject hypothesis H3.

Based on the theoretical determinants of planning capacity, we initially assumed that the ability of grassroots initiatives to co-design their strategic plans would stem from their capacity to market goods and services, their prior experience with successfully introducing innovations, and the corresponding availability of internal financial resources. Participants in the focus groups similarly anticipated that these factors would primarily manifest in the design-oriented phases of strategic planning, rather than during implementation, by enabling initiatives to engage a broader spectrum of actors in later, more complex stages of the process. However, the empirical results do not support these expectations. We found that the interest of grassroots communities in adopting co-design and co-creation practices is not related to the level of income they generate. Even initiatives with limited financial resources, and those providing only non-commercial public services, routinely employ co-design approaches, an encouraging finding for the inclusiveness of bottom-up planning. Likewise, prior experience with successfully introducing social innovations does not increase the likelihood that an initiative will involve a wider range of actors during strategic planning. For these reasons, hypotheses H4, H5, and H6 are rejected.

Additionally, we integrated into our model an investigation of the relationship between the experiences of grassroots initiatives with spatial planning (active participation in designing local development plans), the experiences of grassroots initiatives with participation in the creation of legislation and central policies, and the depth of participation in the case of the creation of their own strategies. We found statistically significant relationships between active participation of grassroots communities in local development planning and depth of participation when making their own strategic plans only in the case of model VI. This indicates that grassroots initiatives with prior experience in local development planning tend to involve a wider spectrum of actors specifically in the implementation phase of their strategic plans. Thus, it appears that experience with central policy-making does not translate into an effort to steer strategic planning through co-design with a broader spectrum of actors. These experiences therefore do not serve as a source of learning in this regard.

Regarding the structural effects, the activity spread of grassroots initiatives (captured through the gwb1degree statistic) shows a strong and statistically significant negative effect in networks I–III and VI. Because a negative coefficient indicates greater centralization, these results show that in these phases of the planning process, stakeholder involvement is distributed unevenly. A small core of grassroots initiatives engaged with many different types of stakeholders, while the majority involved only a few. This reflects a pronounced “activity” centralization among initiatives: most maintain limited collaboration networks, whereas a minority function as highly connected hubs within the planning process, mainly in the early stages and again during implementation. The lack of centralization in phases IV and V reflects a contraction of participation rather than a broader or more balanced stakeholder involvement. The networks appeared to be non-centralized because almost all initiatives cooperate with only a small number of stakeholders. This shows that these stages are treated as more internally controlled parts of the process, as the initiatives may lack the capacity or motivation to involve a broad set of stakeholders.

The variables that we included in the model as controls also provide interesting information in many respects. In accordance with the results obtained for the “commercial activities” parameter, the accumulation of experience and the professionalization of the grassroots initiative (measured by its age and employment of professional staff) did not lead to a deepening of participation in the phases of preparation and formulation of the strategic document. It turned out that older and more experienced grassroots initiatives only increasingly focus on the co-deployment of solutions. At the same time, it became clear that the depth of participation in the planning processes was similar both in the case of grassroots communities in urban and rural settlements. The variable “highest spatial level of activity” was included as the hierarchical structure of grassroots initiatives often includes operational units in several locations, which can represent an obstacle in the participatory planning process. The results of the analysis confirmed this assumption.

5. Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated patterns of co-design and the co-deployment of solutions in the case of community-led grassroots organizations in the conditions of Slovakia. Firstly, we can confirm the initial assumptions [15,37] that community-led actors use participatory procedures, including co-design and co-creation, or the co-deployment of solutions, to an increased extent. The results supported the expectation that grassroots initiatives form cross-sector ties during the planning cycle, as actor networks show a clear presence of external partners in multiple phases of plan design and also in the phase of implementation. This empirical pattern strengthened the theoretical claim that grassroots innovators mobilize wider territorial actors when addressing shared local challenges [5,37].

We believe, in accordance with Crisman [14], that specific feelings of belonging, a community’s way of life and work, or the related narrower power structures in the community can be considered as the basic prerequisites for the creation of co-created solutions in the grassroots organization. The community is indeed a key asset of certain types of grassroots initiatives [11,12,16,34,59]. A grassroots initiative can extract a wide range of resources from its own community—from human labor to financial capital, material, knowledge, and know-how. The interviews and focus groups conducted clearly point to the fact that the community is a source of the diffusion of social capital, as assumed by [60]. The community is a typical source of bonding social capital. As the number of its members grows, linking social capital also accumulates, as each member of the community has dominant work ties in a certain sector. The community thus became a source of self-reinforcing processes of endogenous change thanks to the ability to accumulate knowledge, skills, and know-how within broad collaborative ties, in combination with specific models of resource utilization [61].

It has been found that in the case of the major part of grassroots initiatives, the community is directly involved in every planning phase in the process of co-designing the strategic plan of the initiative, while individual members of the community can have a strong position in managing the planning procedures. In the case of the majority of the grassroots initiatives in the sample, their own communities had the competence to approve the strategic plan. At the same time, the community was very frequently involved in the implementation of the plan, the creation of new products and services, and the co-creation of infrastructure, etc., through their own physical or managerial work. Community members also have an irreplaceable role in maintaining the created solutions.

The assumption [12,37,59] that the majority of grassroots initiative projects are not co-deployed only with the deployment of internal resources was confirmed. Thus, grassroots initiatives did not represent “closed worlds” but very actively develop collaborative projects [15]. The wide inter-sectoral participation in the planning of grassroots interventions stems mainly from the “need” for their involvement. Grassroots initiatives often created solutions that cannot be implemented without permits, premises, financial support, or services from another actor—especially municipalities, other non-profit organizations, and universities. However, these actors were more involved in the co-design of the solution than in its implementation. Still, our findings confirm that the involvement of actors varies systematically across the six planning stages, which substantiates the relevance of distinguishing planning depth, as proposed by Slave et al. [17].

The probability that a grassroots initiative will seek the implementation of collaborative solutions in cooperation with external actors is in accordance with Seyfang and Haxeltine [12], or de Vries et al., [13] growing, together with the development of the organization itself, its professionalization and accumulation of experiences. The mature and well-established grassroots, which already operate commercial products on the small markets, increasingly create collaborative solutions. External actors are also involved in the preparation of the draft plan, as long as they participate in the planned interventions. However, with the growth in the spatial level of grassroots initiative activity, the probability of “deepening” the level of participation decreased, and therefore we believe that cross-sectoral cooperation with other actors in the case of grassroots initiatives is relatively highly localized. Inter-sectoral cooperation was in accordance with expectations [17], most frequent especially in the early phases of the planning cycle, namely, in the phases of pre-planning consultations and information gathering.

We would like to call for further research in the field of applied planning models of community actors, which can be a significant source of lessons learned in the field of strategic plan co-design and the use of alternative communication methods and joint decision-making methods within planning approaches. At the same time, it is necessary to investigate how the emancipation and evolution of active civic communities contribute to the formation of “social clusters” that implement collaborative projects addressing local challenges. If it is possible to identify pro-active grassroots communities in the space that are able to effectively develop cross-sector cooperation, it is also necessary to answer the question of whether they are able to generate primarily social or commercial innovations and to investigate specific forms of the co-deployment of innovative solutions.

This study also has its limitations. These are primarily connected with the obtained sample, whose characteristics are mainly a consequence of the chosen data collection methods and the inability to specify the full population of grassroots initiatives. We consider the main conceptual limitation to be the inability to connect the assessment of the “depth” of participation with concrete, applied planning models, which were very specific in the conditions of individual grassroots initiatives, and it is necessary to properly conceptualize them first. The timing of data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic affected the willingness of grassroots initiatives to participate in the research. At the time, many grassroots initiatives were trying to adapt managerial and planning processes to the crisis. These facts may have influenced the way they described their activities and capacities. The other limitations are mainly related to the nature of the obtained data, which do not allow for us to describe specific projects and methods of cooperation between grassroots initiatives and other spatial actors.

6. Conclusions

Grassroots communities represent a form of “civic” or “inter-sectoral” network, or social clusters that are able to generate solutions that address key local challenges or global challenges locally. The success of grassroots initiatives in the effort to fulfill its social goals also lies in the application of the co-designing procedures of strategic plans, which, although not long-term, allow for the flexible involvement of actors from other sectors (especially at the local level) and lead to the delivery of co-created solutions. The involvement of external actors is motivated by mutual benefit and need, as grassroots community projects often bring absenting solutions within the competences of local governments or are complementary to the interventions of actors in the non-profit sector, the state sector, or to university projects. The strategic plans of grassroots initiatives are created in the co-design process, mainly due to the broad involvement of their own community in all phases of the planning process. The community thus becomes both a planner and implementer of grassroots projects and one of the most valuable assets of the grassroots initiative. Mature grassroots initiatives are better able to involve external actors in implementation processes and create collaborative solutions. They are thus a source of formation of imaginary social innovation clusters, active especially in conditions of local development.

Our findings suggest that post-socialist environments require participatory planning frameworks that can work with low levels of trust, fragmented networks of actors, and historically weak traditions of civic engagement. The results also suggest that strengthening co-production and co-design processes can contribute to building more stable relational structures, thereby creating the conditions for more sustainable and inclusive forms of local planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.; methodology, L.V.; software, L.V.; validation, M.H. and L.V.; formal analysis, L.V.; investigation, M.H.; resources, M.H.; data curation, L.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., L.V. and J.J.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; visualization, M.H.; supervision, J.J.; project administration, J.J.; funding acquisition, J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Slovak Research and Development Agency under Grant [APVV-21-0099].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The author’s home country has delegated the function of ethics review to individual universities and research institutions. However, the author’s university, the Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, does not conduct ethics reviews for ongoing research projects; it only reviews cases of ethical violations. Against this backdrop, the Vice-Rector for Research at the Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra reviewed the research described in this manuscript and determined that it fully complies with ethical standards and integrity requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to privacy, or ethical restrictions in informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive characteristics of the variables that are included in the analysis.

Table A1.

Descriptive characteristics of the variables that are included in the analysis.

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community size | 106 | 121.01 | 136.09 | 5 | 1000 |

| Average annual income for the last 5 years | 106 | 116,204.50 | 256,806.70 | 0 | 1,800,000 |

| Social innovator | 106 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Engages in commercial activities | 106 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Involvement in LDP | 106 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Involvement in the creation of central policy | 106 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 106 | 11.13 | 9.94 | 1 | 65 |

| Employees | 106 | 4.66 | 12.86 | 0 | 90 |

| Highest spatial level of activity | 106 | 5.48 | 2.80 | 1 | 9 |

| Rurality | 106 | 0.82 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Degree of goal achievement | 106 | 0.68 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 1 |

| Length of the planning period | 106 | 1.54 | 2.00 | 0 | 7 |

| Strategic planning | 106 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

Table A2.

Distribution of grassroots initiatives by legal form and the type of impact on local development.

Table A2.

Distribution of grassroots initiatives by legal form and the type of impact on local development.

| Percentage | |

|---|---|

| Legal form | |

| civic association | 68% |

| interest groups | 13% |

| non-profit organization | 5% |

| organization established by public sector (budgetary or contributory) | 3% |

| social enterprise | 1% |

| informal citizen groups/informal cross-sector platforms | 10% |

| Type of impact on local development | |

| environmental development | 26% |

| community development, networking, and development of participation | 19% |

| development of awareness and education | 10% |

| infrastructure and mobility development | 7% |

| culture, arts, and sports development | 22% |

| social development | 16% |

Table A3.

Model MCMC diagnostics p-values (last round of simulation).

Table A3.

Model MCMC diagnostics p-values (last round of simulation).

| Variable/Network | I | II | III | IV | V | VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder: community (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.924 | 0.238 | 0.617 | 0.051 | 0.948 | 0.982 |

| Stakeholder: volunteers (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.102 | 0.496 | 0.864 | 0.395 | 0.864 | 0.869 |

| Stakeholder: other NGOs (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.457 | 0.055 | 0.683 | 0.730 | 0.679 | 0.418 |

| Stakeholder: enterprises and their assoc. (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.623 | 0.651 | 0.252 | 0.141 | 0.177 | 0.910 |

| Stakeholder: state government (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.960 | 0.720 | 0.356 | 0.086 | 0.357 | 0.028 |

| Stakeholder: academic sector (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.564 | 0.679 | 0.506 | 0.920 | - | 0.442 |

| Stakeholder: other activists (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.418 | 0.874 | 0.416 | 0.355 | 0.270 | 0.464 |

| Stakeholder: marginalized groups (stakeholder-type covariate) | 0.645 | 0.041 | 0.129 | 0.222 | - | 0.993 |

| Community size (GI covariate) | 0.550 | 0.149 | 0.268 | 0.044 | 0.200 | 0.495 |

| Average annual income for the last 5 years (GI covariate) | 0.689 | 0.086 | 0.146 | 0.390 | 0.303 | 0.519 |

| Social innovator (GI covariate) | 0.065 | 0.070 | 0.737 | 0.076 | 0.327 | 0.741 |

| Engages in commercial activities (GI covariate) | 0.225 | 0.094 | 0.572 | 0.033 | 0.539 | 0.919 |

| Involvement in LDP (GI covariate) | 0.934 | 0.836 | 0.115 | 0.207 | 0.597 | 0.281 |

| Involvement in the creation of central policy (GI covariate) | 0.660 | 0.783 | 0.302 | 0.476 | 0.444 | 0.507 |

| Age (GI covariate) | 0.553 | 0.149 | 0.518 | 0.064 | 0.623 | 0.721 |

| Employees (GI covariate) | 0.216 | 0.089 | 0.436 | 0.300 | 0.361 | 0.324 |

| Highest spatial level of activity (GI covariate) | 0.251 | 0.433 | 0.696 | 0.082 | 0.448 | 0.562 |

| Rurality (GI covariate) | 0.413 | 0.396 | 0.332 | 0.035 | 0.766 | 0.549 |

| Degree of goal achievement (GI covariate) | 0.515 | 0.202 | 0.305 | 0.030 | 0.346 | 0.672 |

| Length of the planning period (GI covariate) | 0.446 | 0.326 | 0.178 | 0.005 | 0.125 | 0.562 |

| Strategic planning (GI covariate) | 0.578 | 0.348 | 0.481 | 0.100 | 0.186 | 0.619 |

| Activity spread of grassroots initiatives (structural covariate) | 0.337 | 0.175 | 0.318 | 0.008 | 0.821 | 0.840 |

| Edges (structural covariate) | 0.387 | 0.166 | 0.664 | 0.013 | 0.717 | 0.708 |

References

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Strategic Planning and Web-Based Community Engagement in Small Inner Towns: Case Study Municipality of Nemea—Greece. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2021, 21st International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; pp. 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Inglese, P.; Manzi, M.L. A Multi-Methodological Decision-Making Process for Cultural Landscapes Evaluation: The Green Lucania Project. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassin, T.; Ingensand, J.; Christophe, S.; Touya, G. Experiencing virtual geographic environment in urban 3D participatory e-planning: A user perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 224, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carra, M.; Levi, N.; Sgarbi, G.; Testoni, C. From community participation to co-design: “Quartiere bene comune” case study. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomkamp, E. The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, M.; Piskorek, K. The development of strategic spatial planning in Central and Eastern Europe: Between path dependence, European influence, and domestic politics. Plan. Perspect. 2018, 33, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrivnák, M.; Moritz, P.; Melichová, K.; Roháčiková, O.; Pospišová, L. Designing the Participation on Local Development Planning: From Literature Review to Adaptive Framework for Practice. Societies 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptáková, K.; Rigová, Z. Financial Assumptions of Slovak Municipalities for Their Active Participation in Regional Development. Entrepreneursh. Sustain. Issues 2021, 8, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironowicz, I.; Ciesielski, M. Collaborative Planning? Not Yet Seen in Poland: Identifying Procedural Gaps in the Planning System 2003–2023. Bull. Geogr. Socio—Econ. Ser. 2024, 64, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing Grassroots Innovations: Exploring the Role of Community-Based Initiatives in Governing Sustainable Energy Transitions. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, G.W.; Boon, W.P.C.; Peine, A. User-led innovation in civic energy communities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 19, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisman, J.J. Co-Creation from the Grassroots: Listening to Arts-Based Community Organizing in Little Tokyo. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lunenburg, M.; Geuijen, K.; Meijer, A. How and Why Do Social and Sustainable Initiatives Scale? A Systematic Review of the Literature on Social Entrepreneurship and Grassroots Innovation. Voluntas 2020, 31, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Grassroots innovation: A systematic review of two decades of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slave, A.R.; Iojă, J.-C.; Hossu, C.-A.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Petrișor, A.-J.; Hersperger, A.-M. Assessing public opinion using self-organizing maps: Lessons from urban planning in Romania. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 231, 104641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.; Schmidt, S. Enabling Urban Commons. CoDesign 2017, 13, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, D.; Cermeño, H.; Keller, C.; Moujan, C.; Belfield, A.; Koch, F.; Goff, D.; Schalk, M.; Bernhardt, F. Sharing and Space-Commoning Knowledge Through Urban Living Labs Across Different European Cities. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Common-Pool Resources and Institutions: Toward a Revised Theory. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics; Gardner, B.L., Rausser, G.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 1315–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albouy, D. Lectures on Urban Economics by Jan K. Brueckner. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gray, T.; Tracey, D.; Truong, S.; Ward, K. Community Gardens as Local Learning Environments in Social Housing Contexts: Participant Perceptions of Enhanced Wellbeing and Community Connection. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, K.; Persson, O. Community Repair in the Circular Economy—Fixing More Than Stuff. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 1321–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.J.Z.; Zapata, P.; Ordoñez, I. Urban Commoning Practices in the Repair Movement: Frontstaging the Backstage. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2020, 52, 1150–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polko, A. Governing the Urban Commons: Lessons from Ostrom’s Work and Commoning Practice in Cities. Cities 2024, 155, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfield, A.; Petrescu, D. Co-Design, Neighbourhood Sharing, and Commoning through Urban Living Labs. CoDesign 2024, 21, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, D.R.; Parham, D.W.; Porter, D.R.; Potapchuck, W.R.; Schukraft, S.W. Pulling Together: A Planning and Development Consensus-Building Manual; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cisilino, F.; Monteleone, A. Designing Rural Policies for Sustainable Innovations through a Participatory Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmendinger, P.; Haughton, G. Post-political spatial planning in England: A crisis of consensus? Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 37, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, K. Citizen Participation in Planning: Climbing a Ladder? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, M.A.; Leendertse, W.; Arts, J. Conditions for Co-Creation in Infrastructure Projects: Experiences from the Overdiepse Polder Project (The Netherlands). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, E.S.; Morell, M.F. Co-designed strategic planning and agile project management in academia: Case study of an action research group. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Horvath, C.; Spencer, B. Co-Creation as an agonistic practice in the favela of Santa Marta, Rio de Janeiro. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1906–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Schot, J.; Hoogma, R. Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: The approach of strategic niche management. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1998, 10, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Fressoli, M.; Thomas, H. Grassroots innovation movements: Challenges and contributions. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggett, C.; Aitken, M. Grassroots Energy Innovations: The Role of Community Ownership and Investment. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2015, 2, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Longhurst, N. What influences the diffusion of grassroots innovations for sustainability? Investigating community currency niches. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uittenbroek, C.J.; Mees, H.L.P.; Hegger, D.L.T.; Driessen, P.P.J. The design of public participation: Who participates, when and how? Insights in climate adaptation planning from The Netherlands. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 2529–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, D.A. What Constitutes a Theoretical Contribution? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosof, M.S.; Sardy, H. A Research Primer for the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Plan. Theory Pract. 2004, 5, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Social Network Analysis; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Galety, M.G.; Atroshi, C.A.; Balabantaray, B.K.; Mohanty, S.N. Social Network Analysis: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jacomy, M.; Venturini, T.; Heymann, S.; Bastian, M. ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, G.; Lewis, J.M.; Wang, P. Statistical Network Analysis for Analyzing Policy Networks. Policy Stud. J. 2012, 40, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusher, D.; Koskinen, J.; Robins, G. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, G.; Pattison, P.; Kalish, Y.; Lusher, D. An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, G.; Pattison, P.; Woolcock, J. Small and Other Worlds: Global Network Structures from Local Processes. Am. J. Sociol. 2005, 110, 894–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Pol, J.; Rameshkoumar, J.-P. The co-evolution of knowledge and collaboration networks: The role of the technology life-cycle. Scientometrics 2017, 114, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Handcock, M.S.; Hunter, D.R. Specification of Exponential-Family Random Graph Models: Terms and Computational Aspects. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 24, 1548–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siciliano, M.D.; Wang, W.; Medina, A. Mechanisms of Network Formation in the Public Sector: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2020, 4, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta-Paredes, M.-P.; Cronin, B. Exponential random graph models for management research: A case study of executive recruitment. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.R. Curved exponential family models for social networks. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.R.; Goodreau, S.M.; Handcock, M.S. Goodness of Fit of Social Network Models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2008, 103, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivitsky, P.N.; Hunter, D.R.; Morris, M.; Klumb, C. ergm 4: New Features for Analyzing Exponential-Family Random Graph Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 105, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, P.; Cranmer, S.J.; Desmarais, B.A. Temporal Exponential Random Graph Models with btergm: Estimation and Bootstrap Confidence Intervals. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 83, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.M. gwdegree: Improving interpretation of geometrically-weighted degree estimates in exponential random graph models. J. Open Source Softw. 2016, 1, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]