Abstract

Existing jealousy scales often conceptualize jealousy as an undesirable or maladaptive emotion. However, jealousy is a biologically rooted emotion inherent in humans and observable in certain animal species as well. The key lies not in the elimination of this emotion, but in its appropriate regulation. In contemporary society, where exposure to social media is pervasive, the experience and expression of jealousy can become more destructive. This study was designed in response to the growing need to understand and assess jealousy. The aim of the present research was to develop a multidimensional current jealousy scale and to present preliminary findings regarding the influence of social media. Employing a quantitative research design, data were collected online from a sample of 1053 adult volunteers (aged 18 and above) in Türkiye. The resulting instrument, named the Üsküdar Jealousy Scale, comprises 25 items and 4 dimensions: Relationship-Damaging Jealousy, Destructive Jealousy, Hostile Jealousy, and Controlled Jealousy. The total scale demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.93), with subscale reliabilities ranging from 0.75 to 0.89. The scale accounted for 57.20% of the total variance. Confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the model fit indices fell within acceptable limits, supporting the structural validity of the scale. Additionally, criterion validity was supported by moderate correlations (r > 0.30 and <0.70) with the Scale of Social Media Jealousy in Romantic Relationships (SSMJRR). Initial findings revealed generally low levels of jealousy among participants. The dimension concerning relationship-damaging jealousy showed moderate levels, while destructive and controlled jealousy dimensions indicated lower levels. Notably, patterns of social media usage significantly influenced jealousy scores. Individuals exhibiting continuous engagement in social media platforms reported higher levels of jealousy. In conclusion, the Üsküdar Jealousy Scale was found to be a psychometrically sound instrument, suitable for both research and self-assessment purposes in the multidimensional evaluation of jealousy. This validated and reliable tool has the potential to distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive expressions of jealousy, offering practical utility for clinicians and individuals seeking deeper self-understanding.

1. Introduction

Jealousy is a multifaceted emotional experience that individuals frequently encounter in contemporary interpersonal relationships, and its intensity appears to be on the rise, at times reaching pathological levels. This emotion is commonly observed not only in romantic contexts but also in professional and broader social interactions. Jealousy can be characterized by an individual’s desire to possess what others have, including material assets, achievements, or physical attributes, often accompanied by unfavorable comparisons with others. Ultimately, it reflects a difficulty in accepting another person’s perceived superiority or advantage [1,2,3].

Definitions of jealousy often highlight it as a multifaceted construct comprising thoughts, emotions, and behaviors triggered by a perceived threat or loss to one’s self-esteem or the existence or quality of a romantic relationship [4]. Based on Lazarus’s emotion appraisal theory [5], this view suggests that jealousy involves cognitive assessment, emotional reaction, and behavioral expression. From this perspective, when confronted with a jealousy-inducing situation, individuals engage in a cognitive evaluation to determine the presence of a potential rival and assess the level of threat posed. Within romantic contexts, cognitive jealousy reflects concerns about a partner’s loyalty or dedication to the relationship [6]. These cognitive assessments are typically accompanied by emotional reactions. Emotional jealousy refers to the anxiety experienced in response to situations that trigger jealousy [4]. While cognitive jealousy relates to doubts about a partner’s fidelity, emotional jealousy encompasses the affective response to such doubts [7]. In contrast to these internal components, behavioral jealousy pertains to the observable expressions of jealousy through specific actions, such as monitoring or surveillance behaviors [8]. Thus, while cognitive and emotional jealousy reflect internal processes, behavioral jealousy captures how these experiences are enacted outwardly [9].

Emotional reactions, on the other hand, may arise in response to a genuine threat to romantic relationships, or as an emotional response to a perceived or imagined threat, triggered by certain situations. Thus, these three components—cognitive, emotional, and behavioral—can manifest either simultaneously or in sequence. In other words, suspicious thoughts can evolve into emotional responses, which may then lead to behavioral actions [10]. Consequently, romantic jealousy is defined as a sequence of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that emerge from the perception of potential romantic interest between a partner and a real or imagined rival, followed by a perceived threat to the relationship’s existence or quality [10,11,12].

The subject of jealousy is also examined in terms of the distinction between jealousy and envy. Accordingly, in jealousy, the individual reacts to maintain a relationship he/she has, while in envy, the individual wants a situation he/she does not have [13]. One of the main differences between jealousy and envy is that jealousy involves three people, not two like envy. An individual may envy others and target what other people have; property, beautiful eyes, personality traits, success, etc. The focus of envy is an object or property. The focus of jealousy, on the other hand, is a third person who is perceived as a threat to the current relationship [3,11]. According to Spielman, envy is the individual’s desire to have what someone else has and the feeling of unhappiness and evil that comes from someone else having what he/she wants to have. Accordingly, envy manifests itself through anger and sadness caused by not being able to possess [14].

Salovey and Rodin introduced the concepts of social relationship jealousy and social comparison jealousy, distinguishing between jealousy and envy. Social relationship jealousy refers to an individual’s reaction when another person threatens their relationship (which may also involve an object) [11]. This form of jealousy can be seen as a response to the perceived risk of losing something the individual possesses. This “something” could be a relationship, material possessions, success, or a professional position, although it is primarily understood as a response to the potential loss or disruption of an emotional relationship. On the other hand, social comparison jealousy arises when an individual desires something that another person possesses, such as a relationship, professional position, success, material possessions, or personal traits, and that person attempts to reinforce or change this situation. Although both are commonly referred to as jealousy in everyday language, it can be argued that social relationship jealousy aligns with the traditional understanding of jealousy, while social comparison jealousy is more closely related to envy [15]. From this perspective, it is evident that jealousy and envy are closely linked. One concept is associated with the desire to protect what one already owns, while the other pertains to the desire to acquire what one does not possess.

On the other hand, it is argued that for a person to be jealous, they must first have narcissistic traits [16]. Individuals who feel a sense of importance, superiority, and greatness tend to view everything as their right and evaluate their sense of entitlement in relation to themselves. In fact, jealousy is an emotion that exists within all of us and is often the one we feel most ashamed of. When a person feels jealous, they should not be ashamed of it but rather seek to understand the reasons behind their jealousy. When jealousy arises, the energy within the person can become destructive, similar to nuclear energy. If a person compares themselves to others, jealousy can begin to cause harm. However, if this energy is used for peaceful purposes, such as asking themselves “Why am I comparing myself to them?”, the energy can be redirected towards self-motivation. For example, they may realize that in order to own the car they desire, they need to make a plan, develop a project, and work towards it. Jealousy, when expressed through peaceful competition, can be beneficial [16]. The idea that the scale developed in this study can be used to assess either peaceful or destructive jealousy adds a potential innovation to the literature in terms of jealousy measurement.

1.1. Approaches to Cause of Jealousy

Although jealousy is commonly explained as a response to the potential dissolution of a relationship due to emotional dynamics, there are various perspectives regarding its underlying causes. For instance, Mead (1977) suggests that jealousy arises from cultural or individual feelings of insecurity and inadequacy [17]. In this view, jealousy is considered a sociocultural phenomenon that exists in varying degrees across all societies [18].

Researchers argue that jealousy is a complex array of emotions and is deeply painful for most individuals [13]. Other researchers suggest that the roots of jealousy lie in love, low self-esteem, fear of loss, and insecurity [19]. Freud proposed four different explanations for the basis of jealousy [3]: sadness stemming from the fear of losing a loved one, the painful realization that we cannot have everything we desire, jealousy towards successful rivals, and vanity resulting from feeling responsible for losing oneself.

The envy of successful rivals, as Freud mentioned in his definition of jealousy, along with the self-criticism that leads individuals to hold themselves responsible for losses, are significant and common dimensions of jealousy [3]. However, when control over these emotions is lost, intense and persistent jealousy can become pathological [20].

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders categorizes jealousy into two diagnostic groups: (a) other obsessive-compulsive disorders and specified related disorders (Obsessive Jealousy) and (b) delusional disorder (Jealous Type). Jealousy is also linked to various psychopathologies, including suicidal behavior, substance abuse, psychosis, and potential comorbidity with mood disorders [21].

However, pathological romantic jealousy can lead to elevated levels of violence [22,23,24] and may manifest as early as the courtship stage of a relationship [25,26]. It has been reported that intimate partner violence can take various forms, including physical, emotional, sexual, and economic violence, or a combination of these [27].

Although jealousy is traditionally considered a pathological or destructive emotion, recent studies have sought to identify more nuanced forms of it. In this context, ‘controlled jealousy’ can be defined as an individual’s awareness of their jealousy, their ability to regulate it within socially acceptable limits, and their ability to utilise it constructively within a relationship. It is closely related to self-control, self-perception, and attachment styles.

A large-scale international study conducted by the World Health Organization revealed that the physical and mental health outcomes for women who experienced spousal/partner violence during their lifetime were significantly worse than for those who were not subjected to violence. Women who experienced violence frequently sought medical attention for psychosomatic complaints such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, nightmares, dizziness, palpitations, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety. This was considered an individual reflection of domestic violence [28,29]. According to the UNFPA-TWAF Domestic Violence Report (2023), 8 out of every 10 people exposed to violence are women, 73% are married, and most are between the ages of 31 and 55. Furthermore, 90% of the perpetrators are men, with the highest percentage being spouses (63%) followed by family members (21%) [30].

On the other hand, when studies on academic jealousy were examined, Massé and Gagné found that students who successfully distinguish themselves from their peers are often envied by others (which they define as a form of jealousy corresponding to the concept of envy). They also observed that students tend to feel jealous of their peers’ social and academic achievements, which is influenced by their own academic success or intelligence [31].

Rentzsch, Schröder-Abé, and Schütz (2015) demonstrated that students develop hostility towards others, particularly in competitive environments, alongside their academic self-esteem, with envy acting as a mediating factor [23]. Similarly, González-Navarro et al. (2018) found that envy moderates interpersonal relationships in both work and competitive environments [32].

The majority of studies have concentrated on validating the evolutionary theory regarding gender differences in emotional and sexual jealousy [33,34,35]. Furthermore, research has explored various factors such as the traits of the rival that provoke this emotion [36], attachment styles [37], relationship satisfaction and commitment [38], self-esteem [39], the link between jealousy and alcohol dependence [40], as well as the role of social media in amplifying this emotion [41].

1.2. Studies on Measurement Tools for Jealousy

The need to assess the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of jealousy as a measurable construct led to the development of a dimensional jealousy scale. In a series of studies, Pfeiffer and Wong created the Multidimensional Jealousy Scale (MJS) to measure romantic jealousy within a Canadian sample. The MJS consists of 24 items, with 8 items for each subscale, based on the theoretical model. Following its development, a series of exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) were performed, resulting in a stable 3-factor solution corresponding to cognitive, emotional, and behavioral jealousy [6]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale’s dimensions and overall score was found to be 0.82. The validity and reliability of the MJS have been supported by numerous studies [8,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

A study highlighting the relative lack of research on individuals who intentionally provoke jealousy in their romantic partners developed scales to measure romantic jealousy arousal behaviors and motives. The findings showed that the Romantic Jealousy Arousal Scale was a single-factor measure with strong reliability, while the Romantic Jealousy Arousal Motives Scale contained five reliable and theoretically meaningful factors. Overall, behaviors and motives related to arousing romantic jealousy were linked to higher levels of jealousy, greater attachment avoidance and anxiety, lower relationship satisfaction and commitment, more relationship alternatives, less passionate love, and more tendencies toward gaming and obsessive love [49].

In a scale development study on romantic jealousy, Scale of Social Media Jealousy in Romantic Relationships (SSMJRR), consisting of three dimensions and 21 items, was developed by Aydın and Uzun. The scale includes the dimensions of Restrictive and Controlling Attitude, Suspicious and Observer Attitude, and Respect and Trust in the Social Media Area. The internal consistency coefficient for the entire scale was found to be 0.92, with each dimension scoring above 0.87. The study involved 417 individuals, aged 18–56, who were either currently in or had previously been in a romantic relationship [50].

The study by Martinez-Leon et al. (2018) aimed to adapt the Interpersonal Jealousy Scale (IJS) [51], originally developed by Mathes & Severa (1981), to Spanish and evaluate its psychometric properties [20]. The IJS measures negative emotions that arise from the actual or perceived loss of a loved one to a rival. The study was conducted with a Colombian sample of 603 adults (59.03% female). Confirmatory Factor Analysis was used to test the factor models, which confirmed the validity of a unidimensional structure consisting of 18 items. The results suggest that the revised Spanish version of the IJS is an effective tool for assessing romantic jealousy.

On the other hand, a scale development study was conducted to measure academic jealousy among 478 university students. The study, developed by Koçak, confirmed a 19-item, three-factor structure consisting of maturity, self-denigration, and envy. The Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency coefficient for the entire scale was 0.77, with individual factors showing the following coefficients: 0.84 for the envy factor, 0.84 for the self-denigration factor, and 0.81 for the maturity factor [15].

Other commonly used scales mentioned in the literature [52] include the Infidelity Dilemmas Questionnaire (IDQ) [33], designed to assess gender differences in jealousy; the Facebook Jealousy Scale, which evaluates the likelihood of jealousy-inducing events related to participants’ activities on Facebook [53]; and the Jealousy Scale [54], which is used to measure three types of jealousy: reactive, anxious, and preventive.

Most contemporary researchers argue that a multidimensional approach to jealousy offers a more comprehensive understanding of jealousy experiences [55,56]. However, despite consensus on the multidimensional nature of romantic jealousy, there is no uniform agreement on the specific dimensions that constitute jealousy. Proposed factor structures differ significantly across various approaches, studies, and measurement tools [57].

Moreover, a review of the literature reveals that there are few studies that use qualitative approaches to measure envy or jealousy, as well as efforts to develop quantitative measurement tools. Existing scales related to jealousy often treat jealousy as an emotion that should not be present. This study, however, views jealousy as an inherent emotion within human biology and aims to develop a contemporary multidimensional jealousy scale. The goal is to examine its psychometric properties to measure jealousy while distinguishing between peaceful and non-peaceful forms of jealousy.

2. Methodology

The research was conducted using a quantitative method, with a focus on statistical analyses during the scale development stages. Since data collection was carried out through measurement tools assessing the current state, the general survey model was employed.

2.1. Ethical Approval

This study received ethical approval from the Uskudar University Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee report number of 61351342/27 April 2021 (30 April 2021). This study was performed according to the principles set out by the Declaration of Helsinki for the use of humans in experimental research.

2.2. Participants

The study sample consisted of 1053 participants, with 82.5% identifying as female and 17.5% as male. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 73, with an average age of 29. Regarding educational background, 65% held a university degree (n = 684), 18% had a postgraduate degree (n = 190), 8.3% had a college degree (n = 87), 7.5% had a high school diploma (n = 79), and 1.2% had a primary school education (n = 13). As for their relationship status, 57.2% were single, 29.7% were married, 8.1% were engaged, and 5% were divorced or widowed. Considering that the criterion validity of the scale developed in the study was done with the social media jealousy scale, the participants were asked which social media applications they used the most and it turned out that the first three applications were as follows: 67.8% use Instagram, 11.9% use Youtube, and 9.7% use X. The study was based on a representative sample collected online, and therefore random sampling was used.

2.3. Data Collection Tools

In the study, a questionnaire form including demographic form, items of the developed scale and Social Media Jealousy in Romantic Relationships Scale was used as data collection tool.

Demographic Form: The participants were asked demographic questions including their age, gender, education level, and relationship status. Additionally, questions related to social media use were included, such as the time spent on social media, preferred platforms, number of accounts, and habits regarding checking social media.

Scale of Social Media Jealousy in Romantic Relationships (SSMJRR): The scale developed by Aydın and Uzun consists of three dimensions: Restrictive and Controlling Attitude, Skeptical and Observer Attitude, and Respect and Trust in the Social Media Area, with a total of 21 items. The internal consistency coefficient for the entire scale was found to be 0.92, and for the individual dimensions, it was above 0.87. The scale was developed with 417 individuals aged 18–56, all of whom were either in or had experienced a romantic relationship. SSMJRR was included in the data collection tool for the criterion validity study of the scale developed in this research [50].

Üsküdar Jealousy Scale (UJS): In the study, the validity and reliability phases of the Üsküdar Jealousy Scale were followed meticulously. The necessary statistical analyses were conducted in areas including content validity, structural validity, discriminant validity, internal consistency reliability, confirmatory factor analysis, and goodness of fit calculations. To begin with, an item pool was created alongside an in-depth literature review. After this, the evaluation inventory was used to assess content validity. The evaluation inventory asked experts to judge each item with one of the following options: “It is appropriate for the item to remain on the scale”, “The item may remain on the scale but is unnecessary”, and “It is not appropriate for the item to remain on the scale”. An expert group, consisting of professionals from various fields, was established to gather a wide range of evaluations. The inventory was sent to the experts via email, and the obtained markings were converted into numerical values and transferred to a spreadsheet program. The fit rates of the items were then calculated using the formula suggested by Miles and Huberman [58].

The formula mentioned above is designed to assess the agreement between researchers (coders) and aims to ensure that the obtained agreement is above 70% [58]. Calculations for content validity were performed using the data gathered from the evaluation inventory. Items with ratings between “0” and “1” in the inventory, as well as those with a compliance rate lower than 0.70, were removed from the candidate scale. As a result, 5 items were removed from the original 35-item candidate scale due to their low compliance value. Consequently, a 30-item candidate scale was finalized, and data collection was carried out using a 5-point Likert scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is a technique used to ensure construct validity during the scale development process. Before performing EFA, it is essential to test the suitability of the dataset. The appropriateness of the data for factor analysis is assessed using two tests: the Bartlett test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure [59]. It is decided whether EFA can be performed or not according to the KMO test result (>0.90 “excellent”; >0.80 <0.89 “very good”; >0.70 <0.79 “good”; >0.60 <0.69 “medium”; >0.50 <0.59 “weak”; <50 “unacceptable”) and the statistical significance of the Bartlett Sphericity test result (p < 0.05).

When factor analysis is conducted, the number of factors is determined based on the eigenvalue statistics (if the Eigenvalue is greater than or equal to 1, a factor is considered present) [60,61]. Another key result of factor analysis is the explained variance, which is also assessed to ensure it falls within an acceptable range. In social sciences, an explained variance rate between 40% and 60% is considered optimal [59].

The next validity test is discriminant validity, which assesses the scale’s ability to measure the intended feature. For this, the total scores from the scale are ranked to create a 27% upper group and a 27% lower group, and these groups are compared using an independent group t-test. In this study, two groups of 284 people each were compared from a dataset of 1053 individuals. The following validity stage is criterion validity. In this stage, data is gathered using another scale that is similar to the developed scale in terms of subject matter and has established validity and reliability in the scientific literature. The correlation (r) between the two scales is calculated to determine if there is a relationship (r < 0.30 “weak”; r > 0.30 and <0.70 “medium”; r > 0.70 “high”). Moving on to the reliability phase, the Cronbach Alpha coefficient is calculated based on the internal consistency analysis of the scale’s item variance for both the total scale and any subscales, if applicable.

The final structure of the scale is determined through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), which is used in the study to verify the accuracy of the factor structure identified during structural validity assessments—in other words, to test the proposed model. Specialized software programs such as AMOS (Version 22) are used for this purpose, and a model is created based on the factors identified in the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Subsequently, the goodness-of-fit indices obtained from this model are examined to determine whether they fall within the acceptable ranges defined in the literature.

2.4. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Participants aged 18 and over were included in the study, and those younger were considered as exclusion criteria for the study.

2.5. Procedure

The application process of the study was carried out in two stages. The first stage was the pilot application, where the survey including the scales was initially administered to 10 participants as a trial. This stage aimed to assess the clarity and comprehensibility of the questions, and no issues were identified. The second stage was the main field application. During this phase, the finalized data collection tool was distributed digitally and responses were gathered based on voluntary participation over a two-week period from 1 to 15 November 2023, following the Ethics Committee approval dated 30 April 2021.

2.6. Data Analysis and Statistical Analysis

In the validity and reliability analyses of UJS, various statistical techniques were employed, including Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Pearson Correlation Coefficient, independent samples t-test, and Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. For the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), a separate dataset of 300 participants was collected, independent from the original 1053-person dataset. Goodness-of-fit indices were calculated using structural equation modeling, including X2/df, RMSEA, NFI, NNFI, CFI, GFI, and AGFI. All analyses conducted as part of the validity and reliability studies were performed using the SPSS 26.0 statistical software, while the AMOS software package was used specifically for CFA.

3. Results

This section will include the validity and reliability analyses of the Üsküdar Jealousy Scale (UJS). First of all, it was examined whether the data set on which factor analysis would be conducted was suitable for analyses within the scope of scale development studies. In this context, the studies were initiated by applying the Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) sampling coefficient and the Bartlett Sphericity Test, which provide clues about suitability for factor analysis. Thus, the KMO coefficient value was found to be 0.94. The results of the analyses conducted with the Bartlett Sphericity Test were found to be statistically significant (X2 = 12,794.22; Sd: 300; p = 0.000). Accordingly, it was decided that the data set was suitable for factor analysis [60]. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to the data set consisting of the data collected with the 30-item candidate scale, which was obtained after the creation of the item pool in line with the literature review and expert opinions and whose content validity was ensured. In the EFA stage, Eigenvalue values greater than 1 for UJS created a factorial structure and a structure consisting of 4 factors was observed to emerge [61].

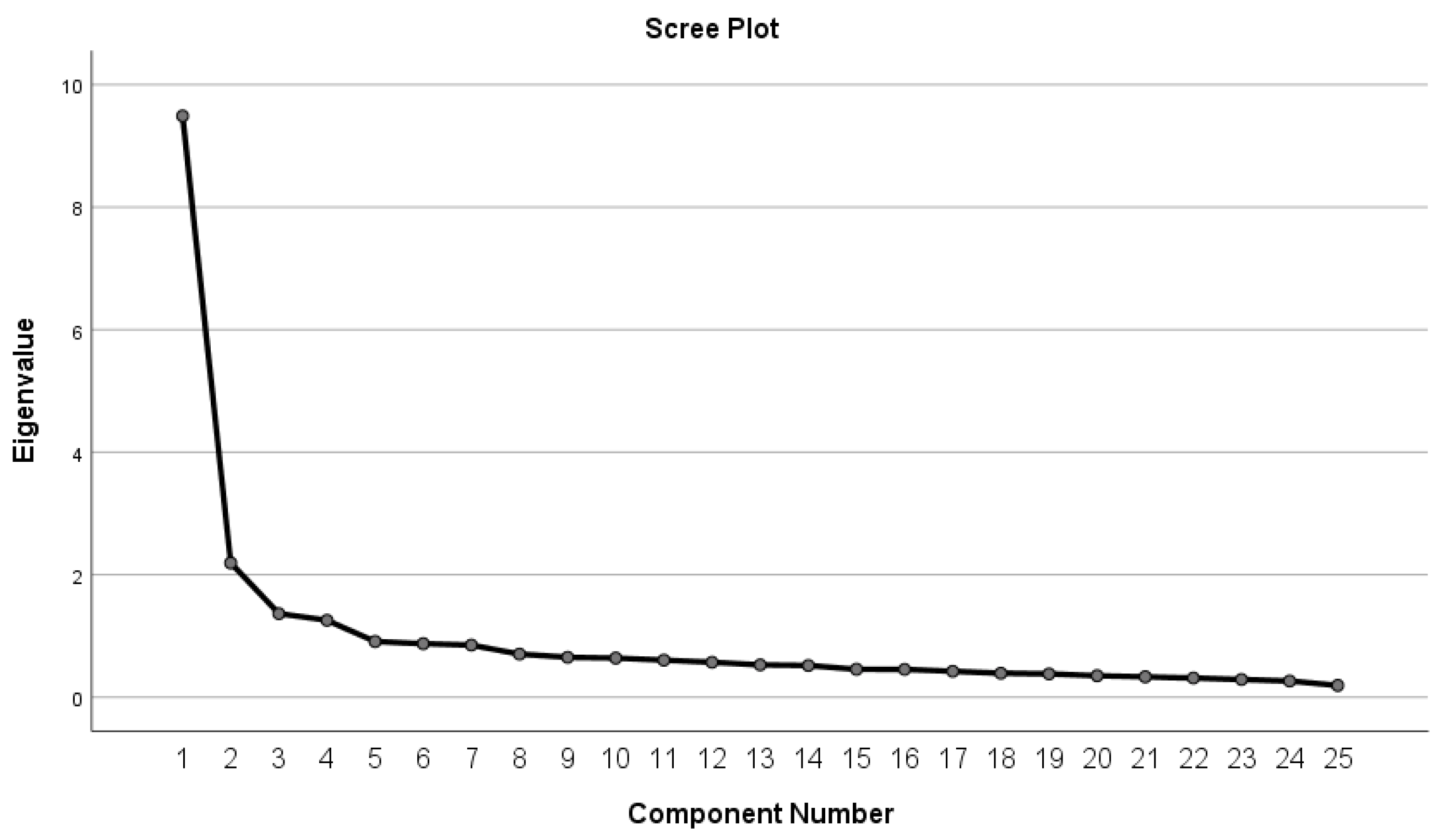

As shown in Table 1, the eigenvalues of the factors range from 9.48 to 1.25. The total variance explained by the overall scale structure is 57.20%. In determining the number of factors, item factor estimates were also reviewed, and items with overlapping or low factor estimates (items 2, 3, 12, 14, and 28) were removed from the scale. As a result, the revised scale consists of 25 items, and the factor estimates for these items are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

UJS Factor Structure and Explained Variance Ratio.

Table 2.

UJS Item Factor Estimates, Item Total Correlation and Cronbach Alpha Values.

As presented in Table 2, the factors forming the scale structure and the distribution of items within these factors were identified, after which appropriate names were assigned to each factor. Specifically, the factor names and corresponding item groupings are as follows: the first factor (items 1–8) was labeled “Relationship-Damaging Jealousy”; the second factor (items 9–14), “Destructive Jealousy”; the third factor (items 15–21), “Hostile Jealousy”; and the fourth factor (items 22–25), “Controlled Jealousy”. Additionally, item-total correlation values for all items were found to be within acceptable limits (r > 0.30), indicating satisfactory item discrimination. The internal consistency of the scale, assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha during the reliability analysis, is also provided in Table 2. The Cronbach Alpha coefficients ranged between 0.75 and 0.89 across the subscales, and the overall scale demonstrated a high reliability score (Alpha = 0.93).

To further illustrate the factor structure, a Scree Plot was used, and the graphical representation of the 4-factor structure of UJS is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

UJS Scree Plot.

With the formation of the factorial structure of UJS, the relationship between the factors and each other and the total scale was determined by the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) and the results are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

UJS and the Relationship of Factors.

According to Table 3, the factors were found to be moderately correlated with one another, with correlation coefficients ranging between r > 0.30 and <0.70, indicating a moderate level of association. In contrast, the correlations between each factor and the total scale score were found to be high (r > 0.70), demonstrating strong relationships and supporting the internal structure of the scale.

Another analysis carried out as part of the validity studies was discriminant validity. To assess this, two groups representing the top 27% and bottom 27% of the scale scores were created. From the total sample of 1053 participants, 284 individuals were selected for each group by ranking the total scores in ascending and descending order. This resulted in a new dataset of 568 participants. An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare these two groups in terms of their scores on each factor and the total scale. The results of this analysis, which were used to evaluate the scale’s ability to differentiate between individuals based on the intended construct, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity of UJS.

The differences presented in Table 4 confirmed the distinctiveness of the scale structure, with the results found to be statistically significant. This supports the scale’s ability to effectively differentiate between individuals with varying levels of the measured trait. As part of criterion validity—another key stage in which the relationship between the UJS and similar existing scales is examined—Scale of Social Media Jealousy in Romantic Relationships (SSMJRR) was selected. Since SSMJRR evaluates scores based on specific factors, the relationship between each of its factors and the total score of UJS was assessed using Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) analysis. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients of UJS and SSMJRR Dimensions.

When Table 5 is examined, it is observed that there are moderate correlations between the dimensions of UJS and those of SSMJRR (r > 0.30 and <0.70), indicating a satisfactory level of criterion-related validity. Although the correlation with the third dimension of SSMJRR is at the lower boundary of the moderate range, it still exceeds the threshold for a weak correlation and can be considered acceptable.

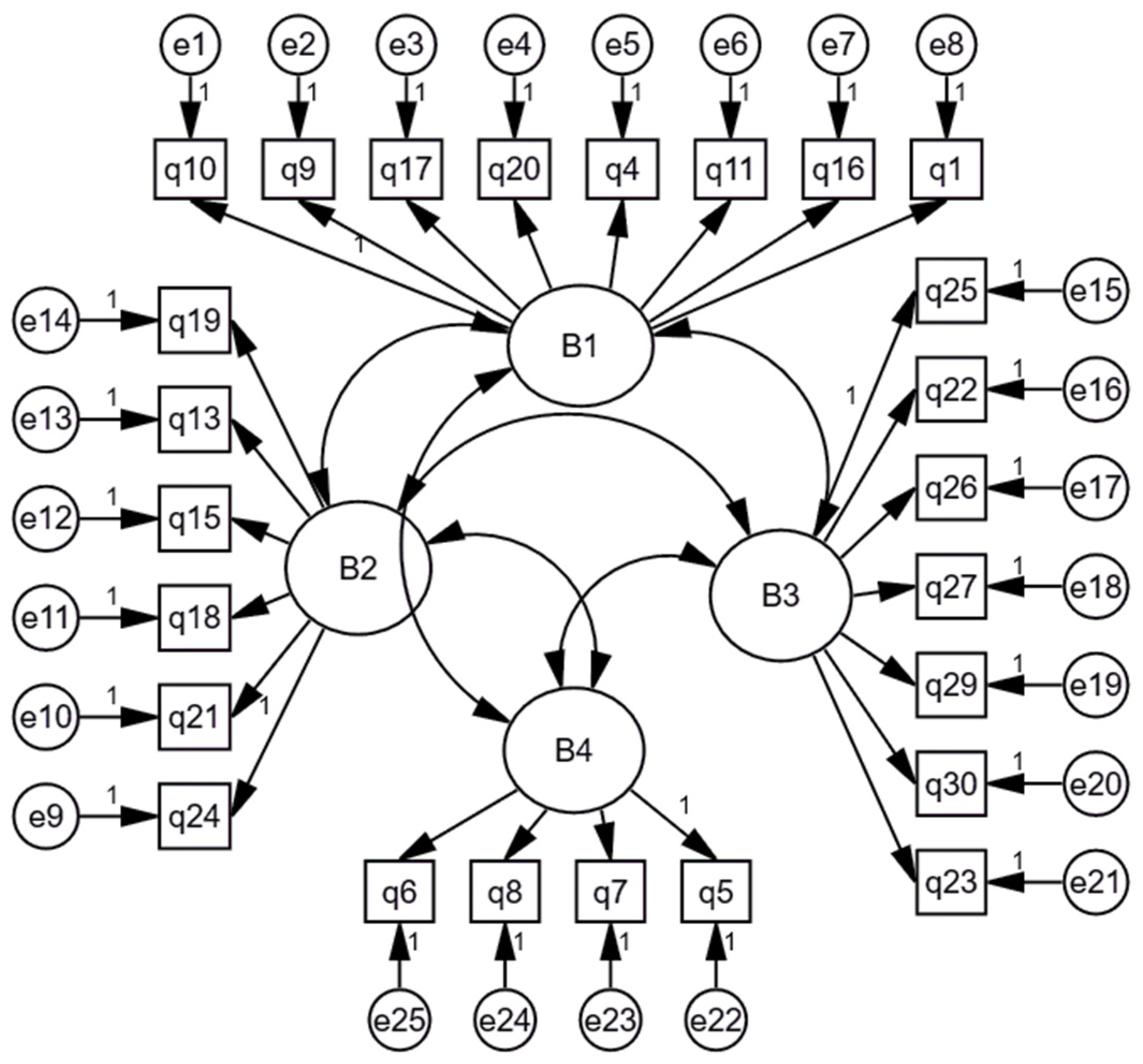

As part of the reliability analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency coefficients were calculated for each factor and the total scale. As shown in Table 2, the reliability values for each factor were within acceptable ranges, while the overall scale demonstrated high reliability with a Cronbach Alpha value of 0.93. Based on the results obtained from the validity and reliability studies, the factor structure established through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was further tested using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). For this purpose, the factorial model of UJS was constructed using AMOS with a new sample of 300 participants, as illustrated in Figure 2. The standardized factor estimates are presented in Table 6.

Figure 2.

UJS Standardized Model.

Table 6.

Standardized Factor Estimates.

The CFA results indicated that the model met acceptable fit indices, demonstrating a good model fit (X2/sd = 2.81 < 3; RMSEA = 0.07 < 0.08; NFI = 0.91 > 0.90; NNFI = 0.96 > 0.95; CFI = 0.97 > 0.95; GFI = 0.91 > 0.90; AGFI = 0.86 > 0.85) [62].

In this study, which examined the validity, reliability, and psychometric properties of the Üsküdar Jealousy Scale (UJS), initial findings based on descriptive statistical analyses from a dataset of 1053 participants revealed that the average total score obtained from the scale was 59.37. Based on the equal interval method used to define score ranges, this average indicates a low level of jealousy (see Appendix A). When broken down by dimensions: The first factor, Relationship-Damaging Jealousy had an average score of 24.90, interpreted as moderate jealousy. The second factor, Destructive Jealousy, had an average score of 12.71, indicating a low level. The third factor, Hostile Jealousy, scored an average of 11.87, which was categorized as none. The fourth factor, Controlled Jealousy, was also evaluated at a low level.

In the final stage, a test–retest reliability study was conducted with 50 participants. The scale was applied to the same group at two-week intervals. The results showed that the scale was appropriate and did not create any differences (UJS1&UJS2: n = 50; X = 59.48; Sd: 18.52; Df: 48; t = 0.45; p = 0.19; r = 0.52; p = 0.00).

Initial comparison tests were conducted at this stage using the Jealousy Scale and its factors, which demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability. The factors and scale were analysed based on gender using an independent samples t-test; the results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparisons of UJS and Factors.

As shown in Table 7, a significant difference was observed in the hostile jealousy dimension. Accordingly, men were found to exhibit higher levels of hostile jealousy than women. When a Cohen’s d effect size analysis was conducted, it was found that the magnitude of this difference was at a low level (d < 0.30). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was subsequently conducted based on the variable of relationship status.

Examining Table 8 reveals that the engaged group has the highest jealousy score. Next comes the single group. The divorced/widowed group has the lowest jealousy level. According to the results of the comparison tests and Cohen’s d effect size analysis, those who are engaged have a higher level of jealousy, with a medium-to-high effect size, compared to married and divorced or widowed individuals. Similarly, it was observed that the jealousy level of singles falls within the medium strength range and is higher than that of married individuals. Differences in the total scale were also observed for the ‘Relationship-Damaging Jealousy’, ‘Destructive Jealousy’ and ‘Controlled Jealousy factors’.

Table 8.

Average UJS Scores of Groups of Relationship Status.

Finally, the study included a series of comparisons to explore the relationship between social media behaviors and jealousy levels. The results, along with the effect sizes (Cohen’s d), are detailed in Table 9. In this context, variables such as whether participants had ever used digital flirting or friendship platforms, whether they had experienced conflicts or breakups due to social media, whether they had purchased followers and their daily social media usage time were compared using t-tests and one-way ANOVA based on UJS scores. Although results were primarily reported for the total scale score, similar significant differences (p < 0.05 *) were observed across all sub-dimensions of the scale, reinforcing the relationship between social media habits and various expressions of jealousy.

Table 9.

Social Media Usage Style and UJS.

When examining Table 9, it becomes clear that jealousy scale scores vary based on social media usage patterns. The results from the independent samples t-test applied to two-category independent variables showed significant differences (p < 0.05). Specifically, the jealousy levels of participants who had engaged in digital flirting or friendship channels at some point in their lives were higher than those who had not. Similarly, individuals who had experienced conflicts and ended relationships via social media exhibited significantly higher jealousy levels than those who had not gone through such experiences.

Additionally, those who were concerned about their follower count on social media and had purchased followers reported higher jealousy levels compared to those who had not engaged in such practices. Further analysis using variance analysis and the LSD difference test, based on daily social media usage time divided into four categories, revealed that jealousy levels significantly increased as daily social media usage increased. Notably, the group reporting being “always connected” to social media exhibited the highest jealousy levels, with a mean score of 72.28, which was significantly higher than that of the other groups (p < 0.05).

According to Cohen’s d effect size analysis, social media usage styles were found to affect jealousy levels at a moderate level (d > 0.30 < 0.70). The variable with the strongest effect was being constantly connected to social media. Participants who reported being always connected exhibited a high effect size (d > 0.70), indicating a substantial impact of this behavior on their jealousy levels.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Everyone experiences feelings of jealousy and envy, but when these feelings become excessive, they can harm social relationships [16]. While experiencing jealousy is a natural human emotion and not inherently wrong, the inability to manage it can lead to harmful or even criminal behavior. Most existing studies on jealousy awareness tend to approach emotion negatively, particularly within the contexts of academic rivalry or romantic relationships. In contrast, this study aims to highlight the necessity of jealousy as a motivating force for peaceful competition, emphasizing the importance of managing and channeling it constructively. It encourages individuals to self-reflect on their jealousy by setting personal goals and striving to surpass them, rather than competing destructively with others.

With the integration of social media into daily life, relationships on these platforms have become as significant as face-to-face communication. More importantly, in the context of romantic relationships, it has been observed that partners develop behavioral patterns such as the desire to learn each other’s social media passwords, monitoring friend lists, gathering information about places visited, and tracking whose photos are being liked. The behaviors observed between partners are frequently analyzed in academic studies within the framework of jealousy, emphasizing its connection to emotional dynamics and trust in interpersonal relationships [63,64]. A study highlights that in romantic relationships, partners often engage in insecure and controlling behaviors, such as creating fake accounts to monitor their significant other, adding individuals of the opposite sex as friends, and more frequently and extensively examining their partner’s profile. These actions reflect underlying issues of trust and control within the dynamics of such relationships [65]. These patterns reveal how social media shapes the dynamics of daily life and romantic relationships, particularly by amplifying jealousy and trust issues.

This study corroborates findings in the scientific literature, revealing that individuals who remain constantly connected to social media, place significant importance on follower counts to the extent of purchasing followers, have engaged with digital dating/friendship platforms at some point in their lives, or have experienced social media-driven conflicts leading to the termination of relationships, exhibit higher levels of jealousy. Furthermore, both the developed scale and the initial findings of the study possess the potential to guide future research endeavors.

The fact that the sample of our research, which was designed according to the accessible sample, consisted mainly of women can be seen as a limitation. It can be taken into account when referring to this research in future studies. It is believed that future studies focusing on gender balance and the application of the scale to different sample groups, particularly in clinical studies, will offer new insights. Studies such as the adaptation of the scale to different cultures and the production of a short version may be conducted in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.T. and A.T.-Ü.; Methodology, A.T.-Ü. and N.T.; Validation, A.T.-Ü.; Formal analysis, A.T.-Ü.; Investigation, A.T.-Ü. and N.T.; Data curation, A.T.-Ü.; Writing—original draft, A.T.-Ü. and N.T.; Writing—review & editing, N.T.; Supervision, N.T.; Project administration, N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed according to the principles set out by the Declaration of Helsinki for the use of humans in experimental research. This study received ethical approval from the Uskudar University Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee report number of 61351342/April 2021-27 (30 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Please contact the corresponding author to get access of data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Üsküdar Jealousy Scale

| Item No. | Items | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

| 1 | It bothers me when someone else shows interest in the person I love. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | It bothers me when the person I love shows interest in someone else. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | It bothers me when the person I love spends more time with his/her friends than with me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | I want the person I love to spend most of his/her time with me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | If the person I am jealous of is close to me, I want him/her to only care about me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | I express my jealousy as anger or resentment. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | I find it problematic when my loved one talks on the phone for long periods of time and shows excessive interest in someone else. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | I get hurt when I do not get enough attention. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | If the person I love loses interest in me, I immediately think that I am being cheated on. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | I have an imaginary fear of being cheated on, and my mind is very busy with this. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11 | From time to time, I experience storms of doubt. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | I often experience the feeling of being unloved, and I even want to know the dreams of the person I love. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | If the person I love does not do everything I say, I start to doubt him/her. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | It makes me suspicious when my loved one constantly works overtime. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15 | I sometimes wish for the person I envy to be in a bad situation. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 16 | I deal a lot with the flaws of the person who makes me jealous, and I am happy when he/she gets hurt. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 17 | I think of myself as not being a jealous person at all, but I also get sad when I see someone I do not like happy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 18 | If the person I envy is in trouble, I feel joy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 19 | I have made moves to harm someone I saw as a rival. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 20 | If the person I see as a rival treats me well, I question his/her intentions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 21 | In the face of problems, I cannot say, “Part of the blame is on me”. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 22 | I always want to be liked, if not I get angry. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 23 | I attach importance to being noticed in my environment. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 24 | I tend to overreact to situations. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 25 | I always want to be trusted; I often question loyalty. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Items 1–8 are related to the first factor “Relationship-Damaging Jealousy”; Items 9–14 are related to the second factor “Destructive Jealousy”; Items 15–21 are related to the third factor “Hostile Jealousy”; Items 22–25 are related to the fourth factor “Controlled Jealousy”. Evaluation: On the scale where 25–125 points can be obtained; 25–44 are “None”; 45–65 are “Low Level”; 66–85 are “Medium Level”; 86–105 are “High Level”; 106–125 are “Very High Level”. Relationship-Damaging Jealousy; 8–40 points can be obtained; 8–13 are “None”; 14–20 are “Low Level”; 21–27 are “Medium Level”; 28–34 are “High Level”; 35–40 are “Very High Level”. Destructive Jealousy; 6–30 points can be obtained; 6–10 are “None”; 11–15 are “Low Level”; 16–20 are “Medium Level”; 21–25 are “High Level”; 26–30 are “Very High Level”. Hostile Jealousy; 7–35 points can be obtained; 7–12 are “None”; 13–18 are “Low Level”; 19–24 are “Medium Level”; 25–30 are “High Level”; 31–35 are “Very High Level”. Controlled Jealousy; 4–20 points can be obtained; 4–6 are “None”; 7–10 are “Low Level”; 11–14 are “Medium Level”; 15–17 are “High Level”; 18–20 are “Very High Level”. Note: If the score obtained from the scale is in the “None” range, it can be evaluated as “Peaceful Jealousy”. | ||||||

References

- Kim, H.J.J.; Hupka, R.B. Comparison of associative meaning of the concepts of anger, envy, fear, romantic jealousy, and sadness between English and Korean. Cross-Cult. Res. 2002, 36, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, W.G.; Smith, R.H. Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, A.M. Romantic Jealousy: Causes, Symptoms, Cures; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.L.; Mullen, P.E. Jealousy: Theory, Research, and Clinical Strategies; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition. In Approaches to Emotion; Shearer, K.R., Ekman, P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1984; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, S.M.; Wong, P.T.P. Multidimensional jealousy. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1989, 6, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.K.; Eloy, S.V. Relational satisfaction and jealousy across marital types. Commun. Rep. 1992, 5, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.K.; Andersen, P.A.; Jorgensen, P.F.; Eloy, S.V. Coping with the greeneyed monster: Conceptualizing and measuring communicative responses to romantic jealousy. West. J. Commun. 1995, 59, 270–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.K.; Andersen, P.A. Jealousy experience and expression in romantic relationships. In Handbook of Communication and Emotion: Research, Theory, Applications, and Contexts; Andersen, P.A., Guerrero, L.K., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 155–188. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.L. A model of romantic jealousy. Motiv. Emot. 1981, 5, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P. The Psychology of Jealousy and Envy; The Gilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.L. Some correlates of romantic jealousy. J. Personal. 1981, 49, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, A.M.; Bowes, C.F. Romantic jealousy. Psychol. Today 1992, 25, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Spielman, P.M. Envy and jealousy an attempt at clarification. Psychoanal. Q. 1971, 40, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, D. Academic jealousy scale: Validity and reliability study. J. Meas. Eval. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 10, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, N. Kötülük Psikolojisi, Toksik Ilişkiler, Şeytan Nerede? Dürtüleri ve Eylemleri Tanımak [Psychology of Evil, Toxic Relationships, Where Is the Devil? Recognizing Impulses and Actions]; Timaş Publishing: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, M. Jealousy: Primitive and civilized. In Jealousy; Clanton, G., Smith, L.G., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; pp. 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B.H. Social comparison in romantic jealousy. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 14, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Pyszczynski, T. Proneness to romantic jealousy and responses to jealousy in others. J. Personal. 1985, 53, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathes, E.W. Jealousy: The Psychological Data; University Press of America: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.L.; Sophia, E.C.; Sanches, C.; Tavares, H.; Zilberman, M.L. Pathological jealousy: Romantic relationship characteristics, emotional and personality aspects, and social adjustment. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 174, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ossorio, J.J.; González-Álvarez, J.L.; Buquerín-Pascual, S.; García-Rodríguez, L.F.; Buela-Casal, G. Risk factors related to intimate partner violence police recidivism in Spain. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2017, 17, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentzsch, K.; Schröder-Abé, M.; Schütz, A. Envy mediates the relation between low academic selfesteem and hostile tendencies. J. Res. Personal. 2015, 58, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureña, J.; Romera, E.M.; Casas, J.A.; Viejo, C.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Psychometric properties of Psychological Dating Violence Questionnaire: A study with young couples. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2015, 15, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, M.; Oliva, A.; Gómez, A.H. Violencia en relaciones de pareja de jóvenes y adolescentes. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2014, 46, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penado-Abillerira, M.; Rodicio-García, M. Análisis del autoconcepto en las víctimas de violencia de género entre adolescentes. Suma Psicol. 2017, 24, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, M.; Jansen, H.A.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet 2008, 371, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köse, A.; Beşer, A. Women’s fate violence. Anadolu Hemşirelik Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2007, 10, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso, M.A.; Garcia-Linares, M.I.; Celda-Navarro, N.; Blasco-Ros, C.; Echeburúa, E.; Martinez, M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. J Womens Health 2006, 15, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFPA-TKDF. Domestic Violence Report. 2023. Available online: https://turkiye.unfpa.org/tr/news/unfpa-tkdf-ev-i%CC%87%C3%A7i-%C5%9Fiddet-raporu-a%C3%A7%C4%B1kland%C4%B1 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Massé, L.; Gagné, F. Gifts and talents as sources of envy in high school settings. Gift. Child Q. 2002, 46, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Navarro, P.; Zurriaga-Llorens, R.; Tosin-Olateju, A.; Llinares-Insa, L.I. Envy and counterproductive work behavior: The moderation role of leadership in public and private organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.; Larsen, R.; Westen, D.; Semmelroth, J. Sex differences in jealousy: Evolution, physiology, and psychology. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 3, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.M.; Vera-Villarroel, P.; Sierra, J.C.; Zubeidat, I. Distress in response to emotional and sexual infidelity: Evidence of evolved gender differences in Spanish students. J. Psychol. 2007, 14, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagarin, B.J.; Martin, A.L.; Coutinho, S.A.; Edlund, J.E.; Patel, L.; Skowronski, J.J.; Zengel, B. Sex differences in jealousy: A meta-analytic examination. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2012, 33, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, A.; Dijkstra, P. Rival characteristics that provoke jealousy: A study in Iraqi Kurdistan. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2015, 9, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miller, M.; Denes, A.; Díaz, B.; Buck, R. Attachment style predicts jealous reactions to viewing touch between a Romantic Partner and close friend: Implications for internet social communication. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2014, 38, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandurand, C.; Lafontaine, M. Jealousy and couple satisfaction: A romantic attachment perspective. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2014, 50, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBello, A.; Rodríguez, L.; Hadden, B.; Neighbors, C. The green eyed monster in the bottler: Relationship contingent self-esteem, romantic jealousy, and alcohol-related problems. Addict. Behav. 2015, 49, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, L.; DiBello, A.; Neighbors, C. Positive and negative jealousy in the association between problem drinking and IPV perpetration. J. Fam. Violence 2015, 30, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utz, S.; Muscanell, N.; Khalid, C. Snapchat elicits more jealousy than Facebook: A comparison of Snapchat and Facebook use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.; Riley, C. Sexual dimorphism in stature (SDS), jealousy and mate retention. Evol. Psychol. 2010, 8, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; DeCicco, T.L.; Navara, G. An investigation among dreams with sexual imagery, romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Int. J. Dream Res. 2010, 3, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Elphinston, R.A.; Feeney, J.A.; Noller, P. Measuring romantic jealousy: Validation of the multidimensional jealousy scale in Australian samples. Aust. J. Psychol. 2011, 63, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblach, L.K.; Solomon, D.H.; Cruz, M.G. The role of relationship development and attachment in the experience of romantic jealousy. Pers. Relatsh. 2001, 8, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C.; Pereira, H.; Esgalhado, G. Evaluation of romantic jealousy: Psychometric study of the multidimensional jealousy scale for the portuguese population. Psychol. Community Health 2012, 1, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S.; Preyss, A.V.; Voracek, M. Romantic jealousy and implicit and explicit self-esteem. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tošić-Radev, M.; Hedrih, V. Psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Jealousy Scale (MJS) on a Serbian sample. Psihologija 2017, 50, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, B.A.; Whitson, D.; Mattingly, M.J.B. Development of the Romantic Jealousy-Induction Scale and the motives for inducing Romantic Jealousy Scale. Curr. Psychol. 2012, 31, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, Y.E.; Uzun, N.B. Scale of Social Media Jealousy in Romantic Relationships (SSMJRR): A study of reliability and validity. OPUS Int. J. Soc. Res. 2021, 18, 7883–7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-León, N.C.; Mathes, E.; Avendaño, B.L.; Peña, J.J.; Sierra, J.C. Psychometric study of the Interpersonal Jealousy Scale in Colombian samples. Rev. Latinoam. De Psicol. 2018, 50, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-León, N.C.; Peña, J.J.; Salazar, H.; García, A.; Sierra, J.C. A systematic review of romantic jealousy in relationships. Ter. Psicológica 2017, 35, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muise, A.; Christofides, E.; Desmarais, S. More information than you wanted: Does Facebook bring out the green-eyed monster of jealousy? Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 13, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, A. Personality, birth order and attachment styles as related to various types of jealousy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1997, 22, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, B.P.; Dijkstra, P. Temptations and threat: Extradyadic relations and jealousy. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships; Vangelisti, A.L., Perlman, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R. Jealousy. In Encyclopedia of Human Relationships; Reis, H.T., Sprecher, S., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 937–941. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, B.K. Personality Antecedents of the Experience and Expression of Romantic Jealousy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa, IA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tavşancıl, E.; Aslan, E. Content Analysis and Application Examples for Verbal, Written and Other Materials; Epsilon: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş. Manual of Data Analysis for Social Sciences; Pegem Citation Index: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. Applied Multivariate Techniques; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley, H.; Tinsley, D. Uses of factor analysis in counseling psychology research. J. Couns. Psychol. 1987, 34, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Lawrance Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alikılıç, Ö.; Alikılıç, İ.; Özer, A. Digital romanticism: A research on the role of social media in romantic relationships of Y generation. Erciyes J. Commun. Spec. Issue Int. Symp. Commun. Digit. Age 2019, 1, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, S.R. Social networking site or social surveillance site? Understanding the use of interpersonal electronic surveillance in romantic relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. J. 2011, 27, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençer, A.G.; Karadere, M.E.; Okumuş, B.; Hocaoğlu, Ç. Diagnoses not included in DSM-5 (Compulsive Buying, Misophonia, Facebook Jealousy, Pagophagia, Cyberchondria, Internet Addiction). In New Diagnoses of DSM-5 in 2018; Hocaoğlu, Ç., Ed.; Türkiye Klinikleri: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.