Abstract

Inclusive graphic design has emerged as a relevant approach within contemporary visual communication studies, driven by the need to ensure that graphic messages can be understood and used by diverse groups of users. Within this context, the present study conducted a systematic literature review with the aim of identifying the advances, trends, and recommendations that support the development of inclusive practices in graphic design. Using the PRISMA methodology, 85 primary studies were selected and analyzed, providing evidence to address the proposed research questions. The findings indicate a concentration of applications in digital interface design and visual communication, alongside the recurrent use of perceptual, cognitive, and semiotic theories, as well as principles of universal design. The analysis also reveals emerging trends related to new technologies, participatory approaches, and multisensory interactions, in addition to strategies that prioritize legibility, contrast, diverse representation, and user-centered design. Altogether, these findings depict a consolidating field that integrates technical, cultural, and social dimensions, highlighting the importance of continuing to develop research and tools that strengthen accessibility and inclusion in visual communication.

1. Introduction

Graphic design is undergoing a continuous process of redefinition and interdisciplinary expansion, with increasingly blurred boundaries between professional profiles and multiple connections to other subdisciplines. As a strategic tool in contemporary society, design assumes ethical, social and cultural responsibilities, adapting to the real needs of users and transforming problems into innovative solutions. In this context, recent laws and regulations aim to promote a more inclusive society by guiding design practice toward greater accessibility and inclusion [1].

The ratification of the United Nations Rights Treaty has driven significant transformations in policies and practices related to accessibility in audiovisual media. This shift has encouraged the adoption of international standards and the development of technologies that ensure access for people with disabilities, increasing awareness and commitment to creating accessible content such as subtitles, sign language interpretation and audio descriptions, which enable equitable participation for all citizens [2].

Inclusive design emerges as a collaborative approach that actively integrates individuals who have traditionally been marginalized or excluded from conventional design processes. Its purpose is to generate accessible and useful solutions for a diverse audience, including those at the extremes of the usability spectrum such as older adults or people with disabilities. In this scenario, graphic design plays a key role by facilitating the visual understanding and communication of complex solutions, strengthening collaboration and ensuring that final products reflect the needs and aspirations of all users [3].

According to Wang [4], visual communication presents six fundamental characteristics: its ability to convey information intuitively and rapidly, its potential to overcome linguistic and cultural barriers, its expressive and emotional strength, its effectiveness in capturing attention, its flexibility to adapt to different purposes and its artistic and creative dimension. These properties make it a powerful tool in fields such as advertising, art and design.

Within this framework, accessibility and inclusion are essential principles of visual communication. They ensure that all individuals, including those with color blindness, visual impairments or neurodivergence, can access and understand information. To achieve this, strategies such as accessible color palettes, adequate contrast, clear visual structures and the use of alternative text are employed, which promote equality and guarantee universal access [5].

The approach to design oriented toward vulnerable populations prioritizes users’ needs, preferences and experiences. This perspective seeks to eliminate physical, cognitive, sensory and emotional barriers, ensuring that resulting solutions are intuitive, clear and functional for a wide variety of individuals [6]. However, important challenges remain. As noted by Cornish et al. [7], both designers and clients often underestimate visual accessibility, partly due to the lack of specific tools and ineffective communication. This limitation restricts the effective integration of accessibility practices within design processes.

Inclusive graphic design responds to contemporary legal and ethical demands and reshapes design practice by placing accessibility at the center of visual communication. Understanding the trends and approaches identified in specialized literature is essential for strengthening professional practices that ensure full participation for all individuals.

Background

The specialized literature on inclusive graphic design has evolved toward an interdisciplinary approach that integrates foundations from cognitive psychology, visual theories and digital technologies. Li [8] highlights the relevance of applying principles derived from cognitive psychology, perceptual laws and Gestalt theory to optimize the perception and recognition of signs and symbols. Elements such as the use of highly recognizable colors, clear typefaces and comprehensible graphics allow visual messages to be adapted to different physiological and cultural limitations, including those of people with visual disabilities. Li also emphasizes the trend toward multidisciplinary integration and the use of digital technologies to reduce communication barriers, particularly in public spaces, strengthening more accessible and universal design solutions.

Along similar lines, Spina [9] stresses that accessibility should be incorporated from the initial stages of the design process to ensure clear, legible and universally accessible visual materials. Among her recommendations are the use of high contrast, reduced glare, appropriate spatial arrangement and the provision of materials in multiple formats adapted to different environments and users.

Collaborative and multidisciplinary design represents another key dimension identified by Massacesi [10], who underscores the value of integrating various design specialties through visual tools such as illustrations, comics, maps, wordless experiences and digital resources. These strategies facilitate comprehension and engagement among diverse audiences, promoting inclusion through simple, clear and shared visual interfaces. This approach improves accessibility and fosters a sense of belonging and social responsibility within graphic design.

Physical environments have also been an important focus of research. Campos et al. [11] highlight the role of graphic design in inclusive wayfinding projects in universities and shopping centers. Universal design applied to these spaces seeks to create products usable by the greatest number of people without requiring special adaptations, considering differences in age, physical abilities and cultural contexts. Karki et al. [12] complement this perspective by proposing that accessible design should be simple, intuitive and user centered, with large and recognizable symbols, soft color palettes, minimalist interfaces and reduced text to facilitate interaction for people with diverse abilities.

Legibility is another essential component. Bigat [13] notes that legibility involves more than the typographic form; it also depends on the relationship with margins, columns, materials and color. A legible design reduces perceptual effort and improves comprehension. Complementarily, Lewandowska et al. [14] warn that design decisions must balance accessibility standards with marketing objectives, as the need to attract attention may sometimes conflict with clarity and inclusion. The expansion of design into social media further requires the creation of more subtle, adaptable and culturally sensitive visual messages.

In the context of digital interface design, Wook et al. [15] develop a conceptual model to improve website usability and accessibility through user centered approaches. Through hierarchical task analyses, focus groups and prototype testing, they identified common issues such as cognitive overload and lack of strategic visual organization. Their findings highlight the importance of applying coherent visual principles, clear hierarchies, relevant multimedia elements and consistent information structures to reduce cognitive stress and ensure a universal experience.

Information design also plays a key role. Ramos [16] proposes enhancing accessibility through appropriate typographic choices, clear visual hierarchy, segmented content with subtitles and responsive adaptations for different devices and screen sizes. These practices contribute to efficient comprehension and visual continuity.

From an intercultural perspective, Batova [17] argues that the meanings and preferences associated with color vary across cultures. Although some colors have more universal meanings, their interpretation differs depending on cultural context, making it advisable to use color in a contextualized and respectful manner. Williams et al. [18] add that accessibility must go beyond technical considerations by incorporating cultural and social knowledge that prevents stereotypes and promotes communicative equity.

As noted in previous studies, graphic design today cannot be limited to traditional aesthetic or functional criteria. It must explicitly integrate principles of accessibility, inclusion and universal usability. Contemporary design plays a fundamental social role by ensuring that information, services and communication environments are understandable and usable by as many people as possible, regardless of their physical, cognitive or cultural characteristics.

Despite theoretical and practical progress, the scientific and technical literature on inclusive graphic design remains fragmented and dispersed across multiple disciplines. This reveals a gap regarding the trends, models and strategies applied specifically to the graphic and visual domain. Such fragmentation hinders the consolidation of robust professional practices and limits the development of policies, standards and tools that can clearly guide designers, institutions and communication professionals.

Furthermore, although various studies have addressed accessibility principles in specific contexts such as digital environments, urban wayfinding, interfaces or intercultural communication, few have offered a transversal and comparative analysis that allows a broader understanding of these practices, identifies gaps in knowledge and establishes directions for future research. In a global context where inclusion has become a central axis of social and technological innovation, conducting this type of review is both relevant and strategic for guiding the development of design policies and practices.

In response to this need, this study presents a systematic literature review that identifies the advances, trends and recommendations supporting the development of inclusive graphic design. The purpose is to offer a structured knowledge base that contributes to academic research and professional practice, promoting design aligned with principles of equity, accessibility and social justice.

To achieve this objective, the study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1. In which areas of design is inclusive design applied with greater emphasis?

- RQ2. What theories, models or principles support inclusive design in the graphic and visual domain?

- RQ3. What advances and trends are observed in research on inclusive graphic design?

- RQ4. What strategies or recommendations are presented for inclusive graphic design?

This analysis will make it possible to illuminate the current state of knowledge, identify emerging patterns and provide a structured perspective to guide future research and design practices centered on inclusion.

2. Materials and Methods

The present research corresponds to a systematic literature review aimed at identifying, analyzing and synthesizing the available evidence on strategies, approaches and trends in inclusive graphic design. The study followed the PRISMA guidelines, which ensured a transparent and reproducible process [19]. The PRISMA checklist can be found in the Supplementary Material Table S1. The full review process has been archived and made publicly accessible through the OSF Records at the following link: https://osf.io/j5e96, accessed on 25 November 2025. And in the Supplementary Materials repository (see Supplementary Material: Table S2).

The methodology was developed in four phases: search, using specific descriptors in academic databases; selection, applying inclusion and exclusion criteria; critical appraisal, considering methodological quality and thematic relevance; and synthesis, organizing the information into emerging thematic axes. This approach provided an integrative and updated view of the current state of knowledge on the subject.

2.1. Information Sources and Eligibility Criteria

For the selection of information, the scientific databases Scopus and Web of Science were used, given their wide coverage and consolidation of relevant scientific content at the international level. Regarding eligibility criteria, studies published in the last ten years (2015–2025) were selected because they capture the most recent and relevant advances in inclusive graphic design, reflect contemporary digital contexts and accessibility standards, and ensure updated and comparable evidence for analysis. No language restrictions were applied in order to provide a global and up-to-date perspective. Given that the authors are proficient in both Spanish and English, studies published in these languages were reviewed directly. Articles written in other languages were translated using technological translation tools during both the title, abstract and keywords screening phase and the full text evaluation phase. Scientific articles, conference papers, systematic or narrative reviews and book chapters were included, as these types of documents allow for a detailed and specific examination of topics related to inclusive graphic design and its application strategies.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy began in the Scopus database using a block-based approach with keywords related to graphic design and inclusion. The preliminary results were analyzed in RStudio (version 4.4.2) through the biblioshiny tool, which made it possible to identify additional relevant terms that might not have been considered in the initial search. The same procedure was subsequently replicated in Web of Science. The final search was conducted on 21 October 2025, and repeated twice to ensure the inclusion of the most pertinent terms. In both databases, filters were applied according to the defined eligibility criteria, restricting the search to titles, abstracts and keywords, and considering only publications from the last ten years. This strategy ensured the relevance, currency and academic quality of the studies included in the analysis (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strings and results obtained.

2.3. Study Selection Process

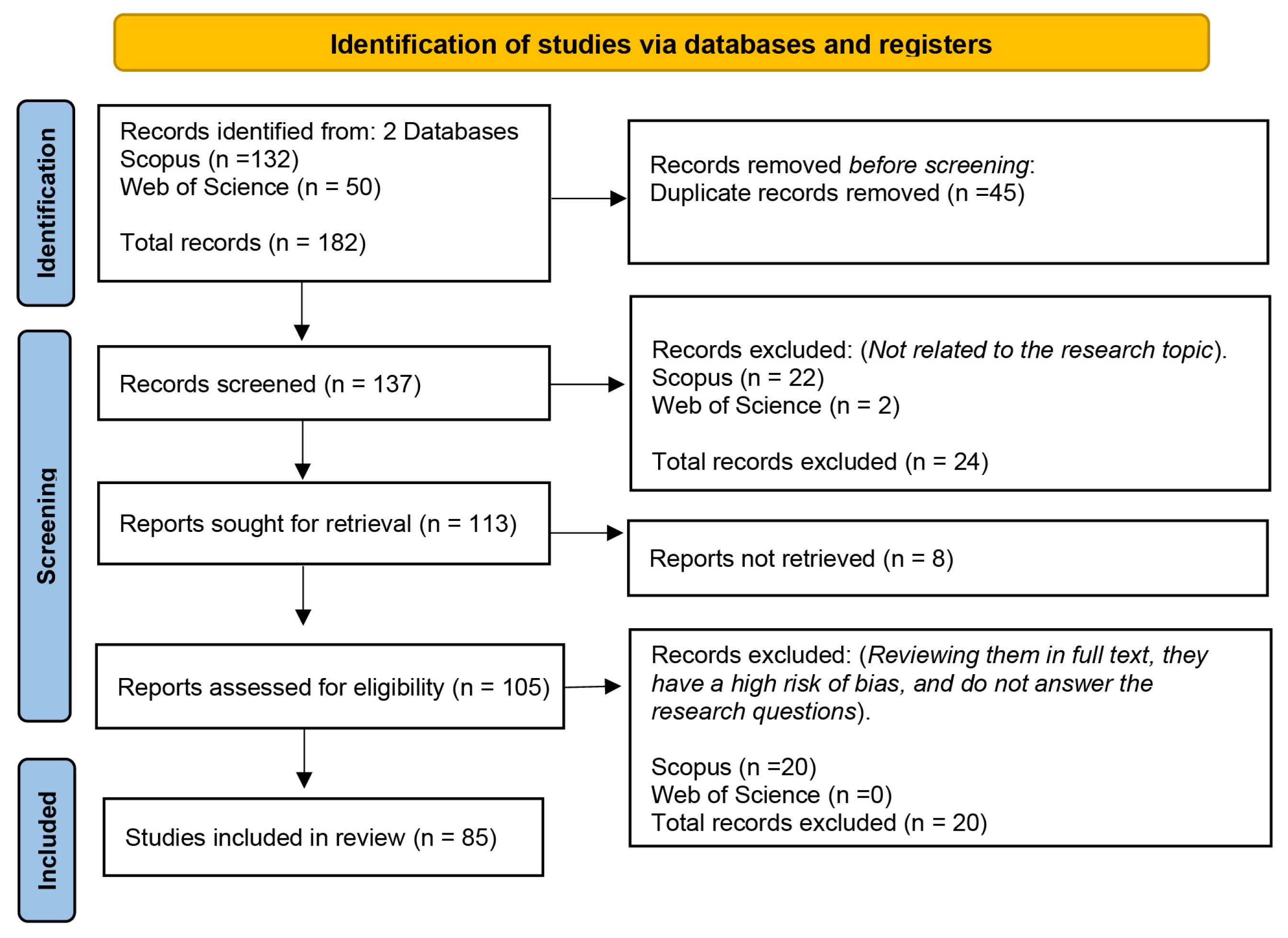

The study selection process was carried out according to the stages established in the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1), ensuring methodological rigor and transparency. In the identification phase, a total of 182 records were retrieved from two scientific databases: Scopus (n = 132) and Web of Science (n = 50). Subsequently, 45 duplicate records were removed, leaving 137 for initial screening.

Figure 1.

PRISMA process diagram.

During the screening phase, 24 records were excluded (22 from Scopus and 2 from Web of Science) because they were excluded because, despite containing related keywords, they did not address inclusive graphic design or contribute to the research questions, focusing instead on unrelated topics such as design history, general education programs, or other non-relevant fields. Of the remaining 113 documents, 8 could not be retrieved for full-text assessment. Ultimately, 105 studies were examined in detail to determine their eligibility, with 20 excluded due to presenting a high risk of bias or failing to address the proposed research questions.

As a result, 85 studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the systematic review, thereby ensuring thematic relevance, methodological quality and the validity of the synthesized evidence.

2.4. Bias Risk Assessment

For the risk of bias assessment, a collaborative approach was adopted in which the authors actively participated as reviewers, evaluators, and independent arbiters for each of the preselected studies. This procedure enabled a more rigorous and consistent evaluation, allowing the exclusion of documents that lacked a clearly defined methodology, did not present a direct connection to the research topic, showed conceptual ambiguity, or did not contribute substantively to the study’s objectives. In this way, the final set of included studies met minimum standards of methodological quality and thematic relevance, thereby reducing potential biases in the interpretation of the results.

2.5. Synthesis Methods

For the synthesis of information, key excerpts and responses were extracted from each of the studies included in the review, prioritizing those that directly addressed the proposed research questions. This process was organized using a systematization matrix developed in Microsoft Excel, which facilitated the structured organization of relevant information. A thematic categorization was then carried out, grouping the extracted content into common conceptual axes to consolidate findings and support comparative analysis. This methodological strategy ensured a clearer, more coherent and comprehensible presentation of the collected evidence, enabling the identification of patterns, trends and gaps in the literature on inclusive graphic design.

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometric Data

The analysis of publication volume shows an upward trend in the scientific output related to inclusive graphic design during the period 2015–2025. As illustrated in Figure 2, although there are year-to-year fluctuations, a sustained increase is evident from 2019 onward, reaching its peak in 2024. This pattern reflects a growing interest in accessibility, inclusion and user-centered design. The evolution of the field suggests its consolidation as an emerging and strategically relevant area of research, driven by technological advances, social demands and new international regulations.

Figure 2.

Distribution of studies by year.

Figure 3 shows the geographic distribution of the studies analyzed, revealing that scientific production on inclusive graphic design is concentrated primarily in countries with high research activity and strong technological development. The United States and China stand out as the territories with the largest number of publications, followed by European and Asian nations such as the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, South Korea, and India. This distribution indicates that research on accessibility and inclusive design is more consolidated in contexts with advanced regulatory frameworks, robust digital infrastructure, and a growing concern for equity in visual communication. At the same time, it suggests opportunities to strengthen the participation of regions with lower representation and to expand cultural diversity in academic production on inclusive design.

Figure 3.

Distribution of studies by country.

3.2. Areas of Application of Inclusive Graphic Design

The literature review identified several domains in which inclusive graphic design has gained particular relevance, reflecting its expansion into increasingly complex digital, communicational, and spatial environments. These applications demonstrate how principles of accessibility, usability, and visual equity are progressively integrated into a wide range of professional and academic practices. Figure 4 presents the main application areas identified, which help illustrate the interdisciplinary scope and growing impact of inclusive design across different contexts.

Figure 4.

Main areas and applications of inclusive graphic design.

One of the fields addressed in the specialized literature on inclusive design applications corresponds to user interface and user experience design (UX/UI) [20]. This domain encompasses the development of web interfaces, mobile applications, interactive environments, and digital platforms that prioritize accessibility and usability for diverse audiences [1,4,14,20,21]. It also includes multisensory experiences, interactive 3D prototypes, and applications in specific sectors such as education and health [12,22,23,24,25,26,27]. This focus responds to the need to ensure more equitable and inclusive digital experiences.

Another area discussed is information design and visual communication, a field that applies accessibility principles to the organization and presentation of data in a clear, structured, and comprehensible manner [5,8,17,28,29,30]. This category includes data visualization, the creation of infographics, scientific and environmental communication, public health campaigns, and communication in crisis contexts [16,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. These applications enable information to be effectively interpreted by audiences with different levels of visual literacy and diverse sensory conditions.

Graphic design, editorial design, and branding are also topics mentioned in the implementation of inclusive design. This domain comprises traditional graphic design practices, visual identity, branding, advertising, iconography, and typography [9,38,39,40,41,42]. In this context, inclusion is expressed through the selection of culturally appropriate, accessible, and recognizable visual elements, as well as the development of visual narratives that reflect social diversity [18,43]. Additionally, the intercultural adaptation of messages and the application of universal design principles in printed and digital materials reinforce communicative effectiveness and promote more equitable representation of target audiences.

Another domain with presence is Environmental or Experiential Graphic Design (EGD/XGD). This area extends beyond wayfinding and navigation systems to encompass the graphic communication of information across physical environments, including advertising, promotion, visual identity, exhibitions, and experiential components integrated into architectural and spatial contexts [13,44,45,46,47]. Its primary objective is to shape inclusive, intuitive, and meaningful interactions between people and spaces, ensuring that users can orient themselves, interpret information, and engage with their surroundings autonomously and safely. To this end, inclusive EGD/XGD practices employ universal pictograms, high-contrast color schemes, legible typography, clear visual compositions, and multisensory resources—such as tactile, auditory, and interactive elements—to enhance accessibility and support diverse perceptual, cognitive, and physical abilities [11,48,49,50].

Audiovisual and multimedia design also holds an important role within this landscape. This category includes the production of motion graphics, visual narratives, interactive audiovisual performances, digital content for social media, and public communication materials [2,6,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Research highlights a growth in the use of accessible animations, automated subtitling, audio description, and immersive technologies that enable multisensory visual experiences responsive to diverse sensory, linguistic, and cognitive profiles.

3.3. Theories and Principles That Could Guide the Creation of Inclusive Graphic Design

The analysis of the reviewed studies shows that inclusive graphic design is grounded in a set of theories, models, and principles that guide the creation of accessible and equitable visual solutions. These conceptual foundations help explain how perception, usability, cognition, and cultural diversity interact within design processes. Table 2 presents a synthesis of the main theoretical approaches and principles identified across the studies, providing an overview of their contribution and relevance within the field of inclusive design.

Table 2.

Theories and principles applied in inclusive graphic design.

The reviewed studies show that perceptual and cognitive theories and principles form an essential foundation for understanding how people process, interpret, and organize visual information. In this regard, approaches such as Gestalt Theory, cognitive models of perception, cognitive load theory, and frameworks related to attention and color differentiation help inform clearer and more accessible visual compositions, particularly for users with diverse sensory or cognitive needs.

Principles and models associated with universal design and digital accessibility also occupy a central position in the literature. Standards such as WCAG, WAI-ARIA, and UNE regulations, together with methodologies such as user-centered design and co-design, guide the creation of visual products that can be used by the widest possible range of people.

Another important contribution comes from theories related to semiotics, visual communication, and culture. Models such as Peircean semiotics, the visual disability discourse framework, and principles of intercultural communication demonstrate that inclusion requires understanding how signs acquire meaning within different sociocultural contexts.

Visual and typographic design principles complement this landscape by integrating the technical and aesthetic criteria needed to ensure clarity, legibility, and ease of navigation. Elements such as contrast, visual hierarchy, color theory, informational coherence, and accessible typographic guidelines contribute to a practical framework for producing comprehensible and functional visual materials. However, text legibility cannot be attributed solely to typographic hierarchy or layout decisions. It is also strongly influenced by the formal and structural characteristics of typefaces themselves, including letterforms, spacing, proportions, and stroke modulation. These aspects, which are primarily addressed within the field of typeface design, play a crucial role in inclusive reading experiences and highlight the need to consider typographic design as a specialized and integral component of inclusive graphic design.

3.4. Trends Applied to Inclusive Graphic Design

The trends applied to inclusive graphic design reflect the diversity of approaches and solutions proposed in the current literature to address the needs of users with distinct sensory, cognitive, and cultural characteristics. This field has progressively incorporated technologies, methodologies, and criteria aimed at expanding accessibility and participation across different communicative and digital environments. Table 3 provides a synthesized overview of the main trends identified, offering insights into how the contemporary landscape of inclusive design is taking shape.

Table 3.

Technological, participatory, and multisensory trends in inclusive graphic design.

The most prominent trends in inclusive graphic design reveal a convergence of technology, social participation, and attention to sensory and cultural diversity. In the technological domain, there is sustained progress in the use of artificial intelligence, automated analysis, immersive technologies and multimodal systems, which enable the development of more adaptive and accessible solutions.

In parallel, participatory and community-based approaches are becoming increasingly solidified, with a growing incorporation of users throughout the design and evaluation process. This shift acknowledges the importance of integrating diverse perspectives including vulnerable or traditionally underrepresented communities and promotes co-creation practices that ensure greater cultural and functional relevance in visual solutions. There is also renewed interest in the semiotic and cultural dimensions of design, which motivates the development of new pictograms, contextualized visual narratives and representations that more sensitively reflect social diversity.

Another set of trends focuses on multisensory interaction, where the combination of visual, tactile, auditory and haptic inputs aims to enhance accessibility and enrich user experience. Immersive experiences, tactile resources and real-time interactive technologies broaden the understanding and participation of audiences with different perceptual abilities, thereby strengthening a more holistic approach to inclusive design. Taken together, these trends illustrate a dynamic field that continues to explore new ways of ensuring more equitable and universal visual communication.

3.5. Strategies and Recommendations for Inclusive Design

One of the strategies mentioned in the literature is the prioritization of legibility, contrast and visual hierarchy. Researchers emphasize the importance of using high-contrast color palettes, clear and readable typefaces with large text sizes and visually structured layouts that facilitate scanning and rapid comprehension [14,41,63,70,71,75,82]. Inclusive design should avoid visual overload, limiting content to essential elements to reduce cognitive demands [16]. International accessibility standards such as the WCAGs [1,14,63,64], are recommended from the earliest stages of the design process so that accessibility becomes a foundational principle rather than a later addition [2,9].

Cultural adaptation and contextual sensitivity also appear as strategies. Inclusive design must consider the cultural specificities of its audiences, adapting symbols, typographies, color palettes and visual narratives to local meanings [17,18,47,68,69]. This includes the use of universal pictograms, motivated signs and culturally relevant representations [42,68,83]. Communication becomes more effective when visual materials reflect users’ identities, values and cultural codes, reducing the risk of ambiguous or exclusionary interpretations [39,43].

Simplicity and minimalism are likewise positioned as essential principles for achieving accessibility [12,35,84,85]. Inclusive design should prioritize essential content, reduce visual complexity and eliminate decorative elements that hinder interpretation [6,16]. Clear, modular and hierarchical structures help individuals with varying levels of visual literacy understand information with less cognitive effort [24,31,46], particularly in environments characterized by high sensory and cognitive diversity.

The literature also stresses the importance of active participation and co-design with users. Direct involvement of target audiences including people with disabilities and culturally diverse groups during early design stages enables the identification of access barriers and the adaptation of solutions more effectively [6,54,59]. Usability testing, prototype review and iterative feedback not only enhance technical accessibility but also reinforce the social ownership and cultural relevance of the final product [1,17,31,59].

Another recurrent recommendation is the integration of technical accessibility and multisensory design elements. This includes the use of captions, alternative text, audio descriptions, compatibility with screen readers and ARIA technologies, as well as the inclusion of tactile and auditory components [11,20,75,81]. Designing experiences that can be accessed through multiple sensory channels ensures accessibility for people with visual, auditory or cognitive disabilities [48,53,59]. Furthermore, visual stimuli should be carefully controlled to avoid triggering photosensitivity or epilepsy in susceptible individuals [82].

Complementing these strategies, the use of inclusive language and diverse representation is identified as a cross-cutting priority [17,43]. Inclusive graphic design must not only ensure technical accessibility but also depict different social groups fairly and respectfully. This involves employing clear and neutral language, avoiding stereotypes, representing marginalized identities and ensuring linguistic and cultural diversity. Approaches informed by feminist and norm-critical perspectives strengthen the potential of design as a tool for equity and social justice [3,78].

4. Discussion

The literature review shows that inclusive graphic design has become established as an interdisciplinary field, focusing on diverse areas, including interface design and user experience. This aligns with the observations of Alcaraz-Martínez and Massaguer [1], who note that regulatory advances and international policies such as those promoted by the United Nations human rights treaty have reinforced the need for digital accessibility in web and audiovisual platforms. Complementarily, the usability issues, cognitive overload and visual organization challenges identified in the results correspond to the findings of Wook et al. [15] and Lewandowska et al. [14], who warn that many digital environments still lack clear hierarchies and effective perceptual strategies to ensure universal experiences. Likewise, the emphasis placed by the literature on information design and visual communication supports the claims of Li [8] and Heggli et al. [5], for whom accessibility largely depends on graphic clarity, color contrast and structured data presentation, especially in public campaigns, scientific communication and information crisis contexts.

The findings also indicate that graphic, editorial and branding design remains a significant space for inclusion. This is consistent with the proposals of Spina [9] and Williams et al. [18], who emphasize that accessibility should not be treated as a technical add-on, but as an ethical component that underpins visual identity, typographic choices and the construction of representative narratives. At the same time, the relevance of signage and spatial design confirms the observations of Campos et al. [11] and Karki et al. [12] regarding the importance of universal design applied to urban, educational, commercial and mobility environments, where the use of pictograms, high contrast and multisensory resources is decisive for ensuring autonomous orientation and safety.

The predominance of perceptual, cognitive and semiotic theories in the reviewed studies reinforces Li’s [8] assertion that understanding how people process and organize visual information is essential. The presence of Gestalt, cognitive principles, visuo-haptic models and color theories indicates that inclusive design is grounded in robust principles that allow designers to anticipate users’ comprehension, attention and mental load. Likewise, the integration of standards such as WCAG, Universal Design and usability heuristics confirms the claims of Spina [9] and You et al. [48], who argue that accessibility must be incorporated from the earliest stages of the design process rather than as a later correction, since doing so helps identify barriers before they materialize in the final product.

Regarding trends, the results reveal an expansion of inclusive design toward advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, generative models, augmented reality, multimodal systems and automated accessibility tools. These developments align with observations by Karki et al. [12] and Tetu et al. [63], who indicate that such technologies contribute to content personalization, objective measurement of perceptual patterns through eye-tracking and the facilitation of automated creative processes. Likewise, the growing presence of multisensory experiences, tactile interaction, spatial audio and interactive installations corresponds to what is described by Campos et al. [11] and Dundure and Apele [81], illustrating an evolution toward inclusive environments that transcend the visual and promote simultaneous access through multiple sensory channels. In parallel, the tendency toward co-design and community participation confirms what Cabim et al. [3] and Massacesi [10] propose: inclusion can only be guaranteed when users actively participate in the creation, evaluation and refinement of visual solutions.

The strategies identified—including prioritization of legibility, contrast, simplicity and visual hierarchy—align with the recommendations of Figueiredo et al. [42], Ramos et al. [16] and Lewandowska et al. [14], reaffirming that perceptual clarity is essential for reducing cognitive overload and improving the experience of people with diverse sensory capacities. In this regard, typographic legibility should not be understood solely as a matter of hierarchy, but also as a result of the formal and structural characteristics of typefaces. Authors such as Perondi emphasize that inclusive typography emerges from careful design decisions related to letterforms, spacing, and reading rhythm, rather than from the pursuit of a single “high-legibility” typeface [86]. Similarly, Piscitelli highlights the social and educational dimension of typography, stressing that inclusive text design must consider context, audience, and cultural diversity [87]. From a complementary perspective, Bilak argues that legibility is a dynamic and contextual phenomenon, shaped by use, environment, and user interaction, which reinforces the need to integrate typographic design into broader inclusive design strategies [88].

Regarding packaging design, the works focused on promoting inclusion through diverse visual representations and inclusive language, the use of frameworks such as the Inclusive Communication Design Framework (ICDF) in packaging and marketing, and semiotic approaches that preserve cultural elements and employ motivated visual signs [43,68]. Together, they emphasize the role of intercultural communication in ensuring that product information can be interpreted by diverse audiences.

Similarly, the importance of cultural adaptation identified in the studies aligns with Batova [17] and Williams et al. [18], who argue that colors, symbols and narratives must be adjusted to cultural contexts to avoid misinterpretation or exclusion. Finally, the results emphasizing inclusive language, diverse representation and intercultural sensitivity reinforce the proposals of Tham [78] and Connory and Tyagi [44], who conceive inclusive design as a practice that must incorporate social justice, equity and plurality of voices to construct visual messages that are more ethical and culturally meaningful.

4.1. Limitations

The main limitations identified in the literature on inclusive graphic design are, first, related to methodological weaknesses. Several studies rely on small samples, offer limited validation with real users—particularly persons with disabilities—and present a general lack of empirical research capable of demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed strategies [6,21,56,70]. In addition, the limited availability of protocols, guidelines and unified standards leads to inconsistencies in the practical application of inclusive design [29,89].

A significant gap is also observed in cultural integration, due to the difficulty of representing symbols, color and visual elements in ways that are universal and free of bias [8]. Most studies do not address how different cultural contexts, levels of visual literacy or sensory conditions influence the comprehension of graphic messages.

The literature also shows limited exploration of multisensory solutions and insufficient research on deep visual accessibility (typography, safe color, perception without vision) [7,59,60]. This highlights the need to develop more empirical studies, inclusive tools and solid methodological frameworks to advance toward truly inclusive and universal graphic design.

4.2. Future Research

Future research on inclusive graphic design should prioritize more robust empirical studies, including larger and more diverse samples with the systematic participation of people with different disabilities, in order to validate the actual effectiveness of accessibility strategies. Advancing toward standardized methodological frameworks and evaluation protocols is also essential to ensure consistent assessment of visual accessibility across interfaces, signage, graphic materials, and other design outputs.

Additionally, future studies would benefit from adopting more focused approaches on specific domains of graphic design, such as experiential or environmental graphic design, packaging design, and branding contexts, which remain underexplored despite their relevance for inclusive communication. Deepening the intercultural dimension of design by examining how diverse groups interpret colors, symbols, and visual structures is likewise necessary to develop culturally sensitive and bias-aware graphic systems.

Finally, expanding research on multisensory solutions including tactile, auditory, and haptic elements as well as developing AI-based tools capable of detecting accessibility barriers and suggesting automated improvements, may significantly enhance the practical implementation of inclusive design across varied professional contexts.

5. Conclusions

The analysis indicates that inclusive design is applied across multiple domains of graphic design, particularly within digital interfaces, where accessibility and usability are essential to support equitable experiences in websites, mobile applications, and interactive platforms. This orientation reflects contemporary technological transformations and the need to address diverse user abilities in highly digitalized environments. Alongside digital contexts, areas such as information design, signage, editorial design, and audiovisual design also play a significant role, illustrating how inclusion is progressively integrated as a transversal principle across different design practices.

This development is supported by perceptual, cognitive, and semiotic theories, as well as by universal accessibility frameworks that inform the structure and evaluation of visual messages. The integration of cognitive psychology, Gestalt theory, principles of universal design, and international standards such as the WCAG shows that inclusive design is grounded in robust conceptual models rather than intuitive decision making. These foundations emphasize the importance of understanding how people perceive, process, and use visual information in diverse social, cultural, and sensory contexts.

Current trends describe a field shaped by the incorporation of emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence, augmented reality, multimodal systems, and measurement tools such as eye tracking, which contribute to the creation of experiences sensitive to users’ abilities, emotions, and cultural backgrounds. At the same time, participatory approaches, co-design practices, and interdisciplinary collaboration reinforce sociocultural relevance and encourage the inclusion of diverse perspectives within the design process, reflecting an ongoing evolution of inclusive design practices.

The recommendations identified in the literature consistently emphasize legibility, appropriate contrast, and visual simplicity, together with cultural adaptation, non-stereotypical representation, and early usability validation. Attention is also directed toward the integration of multisensory resources and assistive technologies, as well as the adoption of clear and accessible communication respectful of individual differences. Taken together, these considerations frame inclusive graphic design as a practice that extends beyond technical requirements and is closely linked to ethical responsibility, social equity, and meaningful participation in visual communication.

Study Limitation

A limitation of the present study lies in its broad approach to inclusive graphic design, which is addressed from a general and cross-cutting perspective. Although this approach enabled the identification of shared trends, theories, and strategies within the literature, some studies focused on highly specific areas of graphic design may not have been included if they did not explicitly use the keywords defined in the search strategy. In addition, the review was restricted to documents indexed in Scopus and Web of Science; therefore, relevant research published in other repositories, specialized books, or non-indexed sources may not be represented. These limitations indicate that the findings should be interpreted as a representative synthesis of the indexed international literature, rather than as an exhaustive mapping of all existing contributions on the topic.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc16010025/s1, Table S1: PRISMA_checklist; Table S2: PRISMA_Process GD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.B.-F. and M.V.S.-L.; methodology, L.M.V.-C. and I.F.B.-O.; software, I.F.B.-O.; validation, S.F.B.-F., M.V.S.-L., L.M.V.-C. and I.F.B.-O.; formal analysis, S.F.B.-F. and M.V.S.-L.; investigation, S.F.B.-F., M.V.S.-L., L.M.V.-C. and I.F.B.-O.; resources, S.F.B.-F.; data curation, M.V.S.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.V.-C.; writing—review and editing, I.F.B.-O.; visualization, L.M.V.-C.; supervision, S.F.B.-F.; project administration, M.V.S.-L.; funding acquisition, S.F.B.-F., M.V.S.-L., L.M.V.-C. and I.F.B.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alcaraz-Martínez, R.; Massaguer, L. What role does graphic design play in web accessibility? Grafica 2021, 9, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. Introduction to accessibility to visual media; a new perspective and direction required by the ratification of the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Kyokai Joho Imeji Zasshi/J. Inst. Image Inf. Telev. Eng. 2015, 69, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabim, L.F.; Taura, T.; Nagai, Y.; Chakrabarti, A. How the Visual Communication Skills of Graphic Design and Inclusive Design’s Co-Design Methodology Can Help Sheltered Workshops Create Viable Busineb Models. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Design Creativity; The Design Society, Bangalore, India, 12–14 January 2015; pp. 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Visual Communication Design of Mobile App Interface Based on Digital. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Supply Chain. Manag. 2024, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggli, A.; Hatchett, B.; Tolby, Z.; Lambrecht, K.; Collins, M.; Olman, L.; Jeglum, M. Visual Communication of Probabilistic Information to Enhance Decision Support. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1533–E1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, A.; Hansopaheluwakan-Edward, N.; Li, D. Visualizing Invisible Information: A Scoping Review of Present Findings, Challenges and Opportunities on Tactile Graphics Design. Vis. Commun. 2025, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Goodman-Deane, J.A.L.; Ruggeri, K.; Clarkson, P.J. Visual Accessibility in Graphic Design: A Client-Designer Communication Failure. Des. Stud. 2015, 40, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Research on Universality Recognition of Public Information Design; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, C. Accessible and Engaging Graphic Design. Public Serv. Q. 2020, 16, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massacesi, R. Applied Arts and Communication Design for Inclusion; Shin, C.S., Di Bucchianico, G., Fukuda, S., Ghim, Y., Montagna, G., Carvalho, C., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 260, pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, L.B.; Maia, I.; Rocha, L.; Rosa, L. Redesign and Improvement of the System of Signaling and Visual Communication for the Rectory of the Federal Institute of Maranhão That Meets the Needs of Visually Impaired People; Rebelo, F., Soares, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 777, pp. 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Karki, A.; Namitha, K.; Singh, K.; Agrawal, R. A Personalized Visual Communication App for Children with Autism; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bigat, E.Ç. Exploring Guidance And Signing Systems. In Environmental Graphic Design as Informational Design: A Study Using Graphic Design Examples; Kašiković, N., Pavlović, Z., Dedijer, S., Vladić, G., Eds.; University of Novi Sad–Faculty of Technical Sciences, Department of Graphic Engineering and Design: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, A.; Olejnik-Krugly, A.; Jankowski, J.; Dziśko, M. Subjective and Objective User Behavior Disparity: Towards Balanced Visual Design and Color Adjustment. Sensors 2021, 21, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wook, T.S.M.T.; Noor, H.A.M.; Judi, H.M. Conceptual Model of Visual Design Publishing Website Interface Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) for Farmers. Asia-Pac. J. Inf. Technol. Multimed. 2025, 14, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.K.L.G.; Miranda, E.R.; Soares, M.F.L.R. Science Popularization on Instagram: An Initial Study Based on Information Design Analysis. InfoDesign 2025, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batova, T. Commentary on the Visual Design Challenges for Cross-Cultural Users of Business Data Visualizations. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Harris, R.; Allison, C. Effective Visual Communication in Higher Education: Intercultural and Cross-Cultural Design. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2025. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.; Sumilang, G.; Providenti, M.; Cho, S.; Reichler, D. Accountability for the Hidden Codes Toward a Better User Experience: Case Study of HRsimple Communication Design for Web Accessibility and SEO; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos Lonsdale, M.; Lonsdale, D.J.; Lim, H.-W. The Impact of Neglecting User-Centered Information Design Principles When Delivering Online Information: Cyber Security Awareness Websites as a Case Study. Inf. Des. J. 2018, 24, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; MacHulla, T. Pressing a Button You Cannot See: Evaluating Visual Designs to Assist Persons with Low Vision Through Augmented Reality; Spencer, S.N., Ed.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, J.P.C.; Maia, I.M.O.; Ferreira, A.V.M.; Rosa, L. Graphic Design of Interactive Tools for People with Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2019, 776, 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Drumeva, K. Graphic Design of Interactive Interfaces; Filjar, R., Iliev, I., Eds.; American Institute of Physics Inc.: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2570. [Google Scholar]

- Ghai, A. Aesthetics, Visual Design, Usability, and Credibility as Antecedent of E-Learning; a Theoretical Framework. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 10903–10909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Hanim, R.N. Enhancing Learning Experiences through Interactive Visual Communication Design in Online Education. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2024, 2024, 134–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wolosiuk, D.; Hofstätter, H.; Pont, U.; Maringer, M.; Schuß, M.; Hauck, N.; Mahdavi, A. Supporting Visual Design for All: The Videa Approach. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference of the International Building Performance Simulation Association, Hyderabad, India, 7–9 December 2015; International Building Performance Simulation Association: Verona, WI, USA, 2015; pp. 1488–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W. A Study of Big-Data-Driven Data Visualization and Visual Communication Design Patterns. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 6704937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragelli, T.B.O.; de Oliveira, J.A.C.; Machado, V.P.; Garcia, K.R.; Pereira, L.C.; Karnikowski, M.G.O.; Areda, C.A. Information design challenges for digital inclusion of older adults from the perspective of health literacy: A scoping review. InfoDesign 2024, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kessel, S. What Do You See? Research on Visual Communication Design to Promote Positive Change for Unorganized Workers in Karnataka, India; Chakrabarti, A., Ed.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 35, pp. 641–651. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen, M.; Heiss, L.; McGee, T.; Bawden, G. The Future Is Participatory: Collaborative Communication Design for Global Health Initiatives. Visible Lang. 2023, 57, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikhil, R.S.; Pranav, S.; Harithas, P.; Shivani, S.; Shruthi, M.L.J. Kannada Subtitle Generation with Speaker Diarization: A Comprehensive Solution for Regional Language Visual Media Accessibility; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 727–733. [Google Scholar]

- Aryana, B.; Osvalder, A.-L.; Stark, E. Universal Crisis Information Design: A Multi-Case Study; Fuglerud, K.S., Fuglerud, K.S., Leister, W.V., Vidal, J.C.T., Eds.; IOS Press BV: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2024; Volume 320, pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mont’Alvão, C.; Clemente, L.; Ribeiro, T. Information Design and Plain Language: An Inclusive Approach for Government Health Campaigns; Black, N.L., Neumann, W.P., Noy, I., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 220, pp. 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.L.; Amaral, I.; Daniel, F. The Contribution of Information Design to Age-Friendly Cities: A Case Study on Coimbra and Public Transport; Rebelo, F., Soares, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 777, pp. 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Ramirez-Andreotta, M.D. Communicating the Environmental Health Risk Assessment Process: Formative Evaluation and Increasing Comprehension through Visual Design. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires Dos Santos, C.; Neves, M.; Costa, D. Illustration as a Key to Understanding Data in Information Design; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Salvendy, G., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 2528 CCIS, pp. 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, P.C.; Choy, C.S.-T. Metaphorical Parametric Model for Brand Mark Design: Towards a Universal Model of Computational Visual Communication Design; Knowledge Systems Institute Graduate School, KSI Research Inc.: Skokie, IL, USA, 2019; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo, D.; Neves, J.; de Fátima Peres, M.; Paiva, T.; Amaral, M.; Silva, J.; da Silva, F.M. Visual Identity Design as a Cultural Interface of a Territory; Rebelo, F., Soares, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1203 AISC, pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sandi, L.Á.; González, T.Q. Visual guidelines of editorial design for a dictionary of graphic design and typography. VISUAL Review. Int. Vis. Cult. Rev. Rev. Int. Cult. 2022, 9, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, B.; Santos, I.; Garcia, J.; Borges, J.; Cruz, S.; Teixeira, A.; Brito-Costa, S.; Almeida, H. The Power of Colors to Maximize Attention and Readability in Visual Communication: Insights from an Eye-Tracking Behavioural Study; Benedicenti, L., Ed.; Avestia Publishing: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Edilson, U. Visual Communication of Sustainability: A Study on the Efficacy of SDG Icons; Zeng, Y., Wang, S., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Connory, J.; Tyagi, S. Helping to Destigmatise the Use of Period Products for Trans, Masculine Presenting, Non-Binary and Gender Diverse (TMNG) Consumers through an Inclusive Communication Design Framework. Cult. Health Sex. 2025, 27, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akili, V.P.A.R.; Srilatha, M.; Sai Charan, B.; Manikanta, B.; Lathigara, A. Sign View: Visual Communication Using LabVIEW; Gunjan, V.K., Zurada, J.M., Kumar, A., Singh, S.N., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 1400 LNEE, pp. 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Villalobos, N.; Rodríguez-Fernández, C.; Fernández-Raga, S.; Zelli, F. Inclusive Information Design in Heritage Landscapes: Experimental Proposals for the Archaeological Site of Tiermes, Spain. Heritage 2024, 7, 4403–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Han, E.J.; Min, J.H.; Park, Y.K. Color Coding Strategy Utilizing Stripe Patterns for Hierarchical Environmental Information Design. Arch. Des. Res. 2021, 34, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Kim, M.-S.; Lim, Y.-K. Value of Culturally Oriented Information Design. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2016, 15, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.L.; Amaral, I. Communication Design and Space Narratives. In Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 103–113, ISSN 26618184, 26618192. [Google Scholar]

- Wille, B.; Allen, T.; van Lierde, K.; van Herreweghe, M. Using the Adapted Flemish Sign Language Visual Communication and Sign Language Checklist. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 2020, 25, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta, R. The Intervention of Graphic Design in Museums. “Dechados” (Paragons) Project Case; La Intervenció del Disseny Gràfic en els Museus. Cas Projecte Dechados. Grafica 2023, 12, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Haapio-Kirk, L. Emotion Work via Digital Visual Communication: A Comparative Study between China and Japan. Glob. Media China 2021, 6, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcıoğlu, Y.S.; Özkoçak, Y.; Gümüşboğa, Y.; Altindağ, E. From Symbols to Emojis: Analyzing Visual Communication Trends on Social Media. Stud. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C. Echo-Space: Inclusive Orchestral Performance Space with Visual Media; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Salvendy, G., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 2524 CCIS, pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. Netizen A11y: Engaging Internet Users in Making Visual Media Accessible; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, J.G.; Toomre, T.; To, C.; Olatunde, P.F.; Cooper, L.; Glick, J.L.; Park, J.N. Communicative Appeals and Messaging Frames in Visual Media for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Promotion to Cisgender and Transgender Women. Cult. Health Sex. 2023, 25, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucia-Mulas, M.J.; Revuelta, P.; Garciá, Á.; Ruiz, B.; Vergaz, R.; Cerdán-Martínez, V.; Ortiz, T. Vibrotactile Captioning of Musical Effects in Audio-Visual Media as an Alternative for Deaf and Hard of Hearing People: An EEG Study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 190873–190881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Design and Research on Visual Communication Under the Influence of Digital Media; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Akwukwuma, V.V.N.; Chete, F.O.; Okpako, A.E.; Irabor, F.E. Improving User Interface Design and Efficiency Using Graphic Design and Animation Techniques. NIPES J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2024, 6, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, I.M.; Felicio, G.; da Silva, E.T.; Villani, E.; Krus, P.; Pereira, L. Mental Imagery for Multisensory Designers: Insights for Non-Visual Design Cognition; Chakrabarti, A., Poovaiah, R., Bokil, P., Kant, V., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 221, pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeersch, P.-W.; Heylighen, A. Involving Blind User/Experts in Architectural Design: Conception and Use of More-than-Visual Design Artefacts. CoDesign 2021, 17, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, K. Visual Design as a Holistic Experience: How Students’ Emotional Responses to the Visual Design of Instructional Materials Are Formed. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2022, 70, 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetu, I.C.; Doan, S.; Potts, L.; McArdle, C. Emerging Practices in A11y Communication Design: Building Accessible Programs Through Accessible Design; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, I.; Lee, E. Effects of Visual Communication Design Accessibility (VCDA) Guidelines for Low Vision on Public and Open Government Health Data. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaguer, L.; Alcaraz-Martínez, R. Analysis of Web Accessibility Skills Required in Graphic Design and Visual Communication Job Offers in Spain; Flores, J., Taboada, J.A., Catala, A., Condori-Fernandez, N., Reyes-Lecuona, A., Eds.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, C.J.; Russo, A. Visual Design Checklist for Glucose Monitor App User Interface Usability Evaluation; Marcus, A., Rosenzweig, E., Soares, M.M., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 14034 LNCS, pp. 454–464. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, A.; Edward, N.H.; Li, D. From Vulnerability to Accessibility, and Expansion Possibilities A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Implications of Information Design for Vulnerable Populations. Inf. Des. J. 2024, 29, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, I.P.; Rosa, C.; Almeida, F. Information Design and Semiology: A Visual Study on Deconstructing Musical Notation for Improving First-Grade Children’s Learning. In Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 35, pp. 639–650. ISSN 26618184/26618192. [Google Scholar]

- Celhay, F.; Cheng, P.; Masson, J.; Li, W. Package Graphic Design and Communication across Cultures: An Investigation of Chinese Consumers’ Interpretation of Imported Wine Labels. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Adaptive Fusion of Multi-Cultural Visual Elements Using Deep Learning in Cross-Cultural Visual Communication Design. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soedirdjo, R.B.; Kusumo, A.H.; Hartono, M. Improvements to Visual Design on the Online News Portal ABC.Com by Employing Usability and Eye Tracking Methods. Eng. Proc. 2025, 84, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, M.; Pavel, A. DesignChecker: Visual Design Support for Blind and Low Vision Web Developers; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Xu, B.; Liu, A. Research and Extraction on Intelligent Generation Rules of Posters in Graphic Design; Rau, P.-L.P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 11576 LNCS, pp. 570–582. [Google Scholar]

- Visescu, I.D. The Impact of Culture on Visual Design Perception; Ardito, C., Lanzilotti, R., Malizia, A., Malizia, A., Petrie, H., Piccinno, A., Desolda, G., Inkpen, K., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 12936 LNCS, pp. 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Spennato, A. Graphic Design as a Universal Language: Symbols and Codes in the Vision of Gio Ponti. Disegno 2025, 16, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-H.; Wu, J.; Bigham, J.; Pavel, A. Diffscriber: Describing Visual Design Changes to Support Mixed-Ability Collaborative Presentation Authoring; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, F. Inclusive Visual Design to Support People with Physical Impairments; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, P.S.; Yeo, S.L.; Koran, L. Advocating for a Dementia-Inclusive Visual Communication. Dementia 2023, 22, 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, J.C. Feminist Design Thinking: A Norm-Creative Approach to Communication Design; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Özmen, M. Sikisma: An Alternative Information Design Project for Ihlamur Pavilions Istanbul; Swallow, D., Sandoval, L., Lewis, A., Darzentas, J., Petrie, H., Walsh, T., Power, C., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 229, pp. 416–418. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ge, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X. Actively Viewing the Audio-Visual Media: An Eye-Controlled Application for Experience and Learning in Traditional Chinese Painting Exhibitions. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 5926–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundure, I.; Apele, D. Graphic design opportunities for integrated approach in museums in reproduction of art treasures. Society Integration Education. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Rezekne, Latvia, 25–26 May 2018; Volume 4, pp. 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, L.; Yildirim, C.; Pavel, A.; Borkin, M.A. Design Considerations for Photosensitivity Warnings in Visual Media; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brod, M.; de Macedo Guimarães, L.B. Contribution of graphic design and ergonomics to an inclusive industrial language; Contribuição do design gráfico e da ergonomia para uma linguagem de produção inclusiva. Rev. Conhecimento Online 2021, 2, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.; Brandão, D.; Guimarães, L.; Penedos-Santiago, E.; Brandão, E. The Importance of Communication Design in the Process of Disseminating Community Practices in Social Neighbourhoods: The Balteiro. Comun. E Soc. 2023, 43, e023010. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, V.G.; Sanjuán, B.C. Graphic design and visual models in the circular economy. Grafica 2024, 13, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perondi, L. L’alta Leggibilità (Non) Esiste?: Cosa Significa Progettare un Testo Graficamente Inclusivo; Nomos Edizioni: Busto Arsizio, Italy, 2024; ISBN 979-12-5958-179-2. [Google Scholar]

- Piscitelli, D.; Cianniello, R.; Angari, R. Type for Peace a Development and International Cooperation Project; University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli: Campania, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Storozynsky, S. How Fonts Can Preserve Culture: An Interview with Peter Bi’lak of Typotheque. Available online: https://www.extensis.com/blog/how-typography-can-preserve-endangered-languages (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Raoufi, K.; Taylor, C.; Laurin, L.; Haapala, K.R. Visual Communication Methods and Tools for Sustainability Performance Assessment: Linking Academic and Industry Perspectives; Zhao, F., Sutherland, J.W., Skerlos, S.J., Eds.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 80, pp. 215–220. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.