The Experience of Internal Exclusion Within the Context of Education in Africa: A Scoping Review of the Views of Philosophers of Education and Educationists

Abstract

1. Introduction

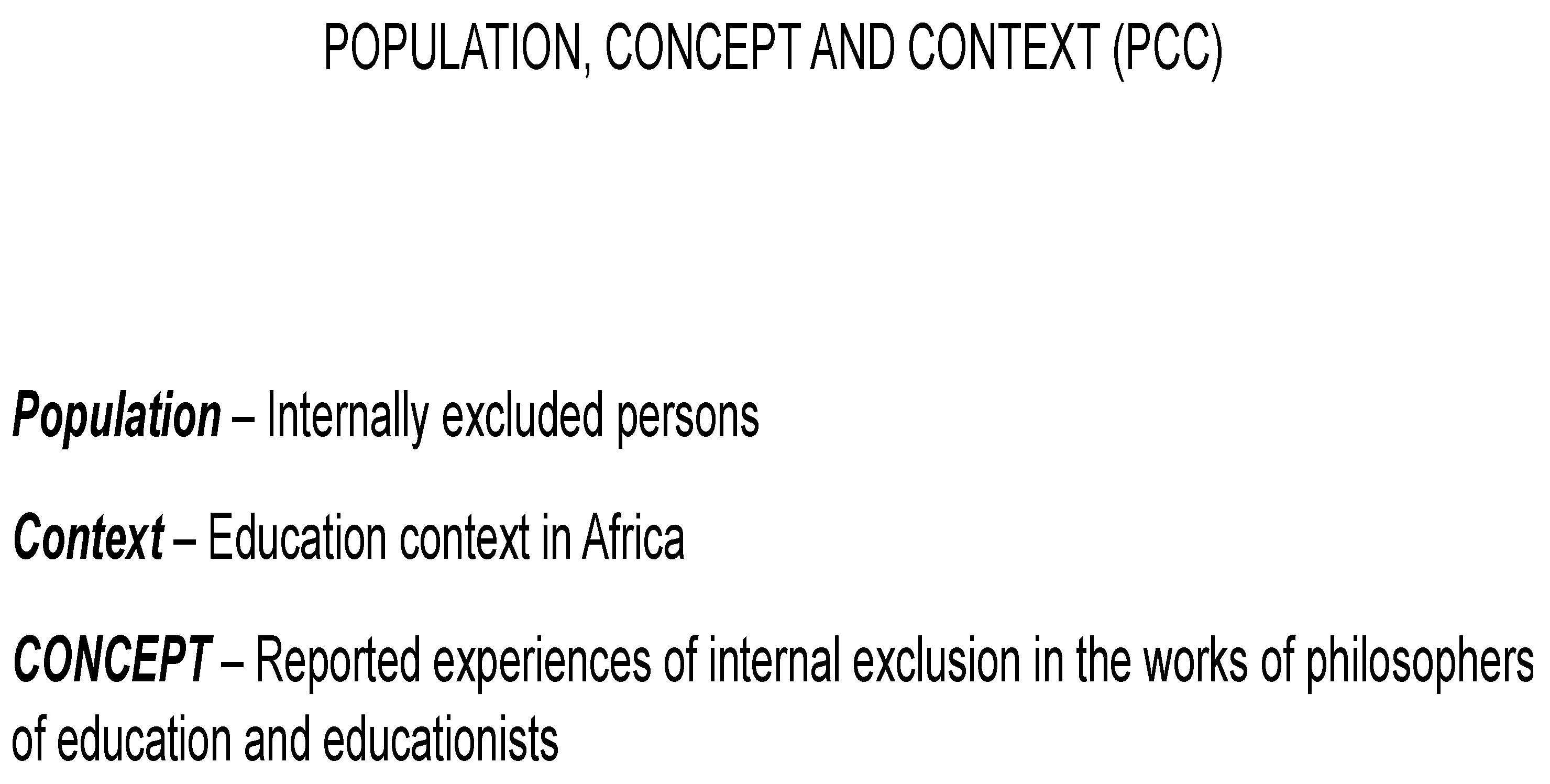

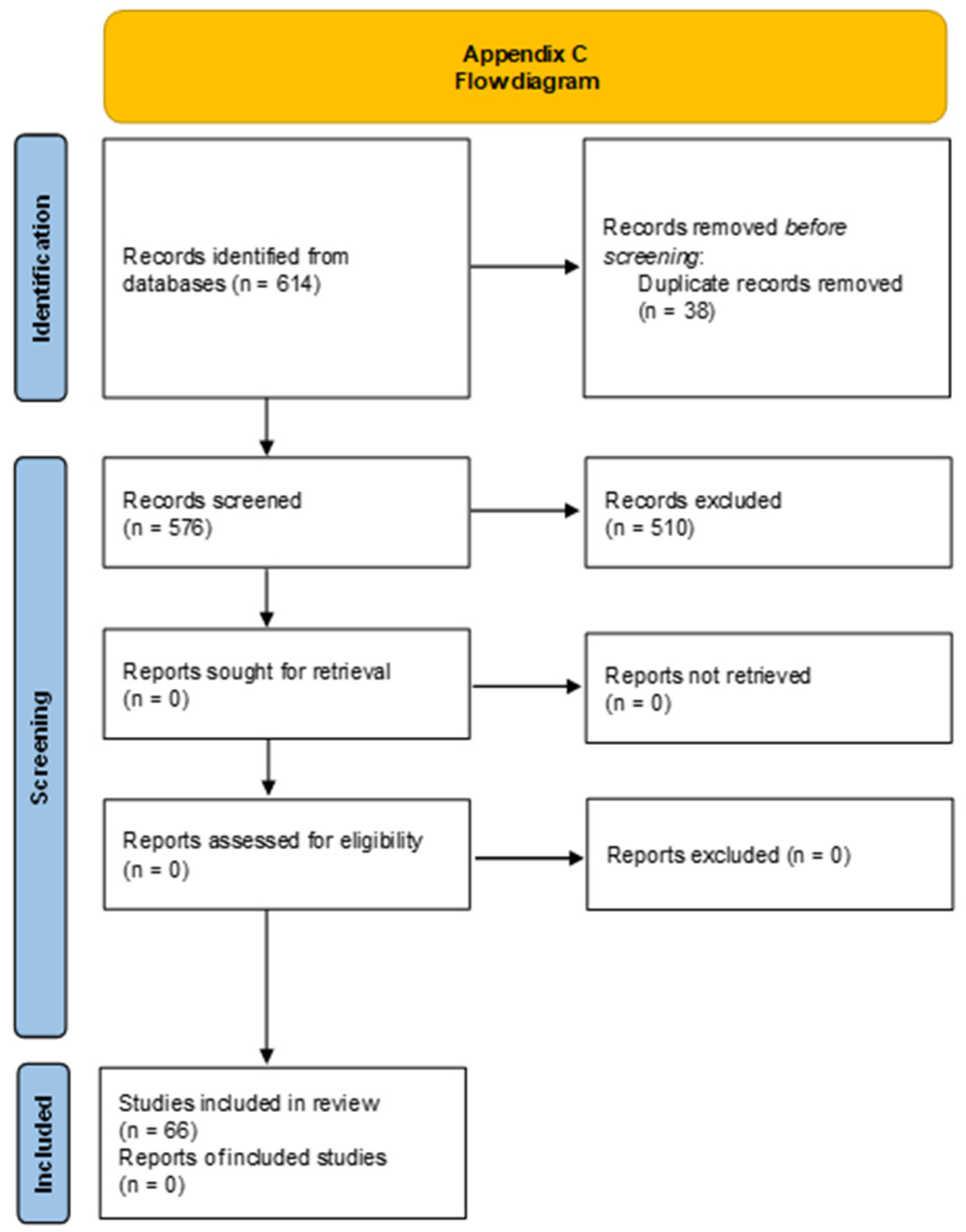

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Process

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

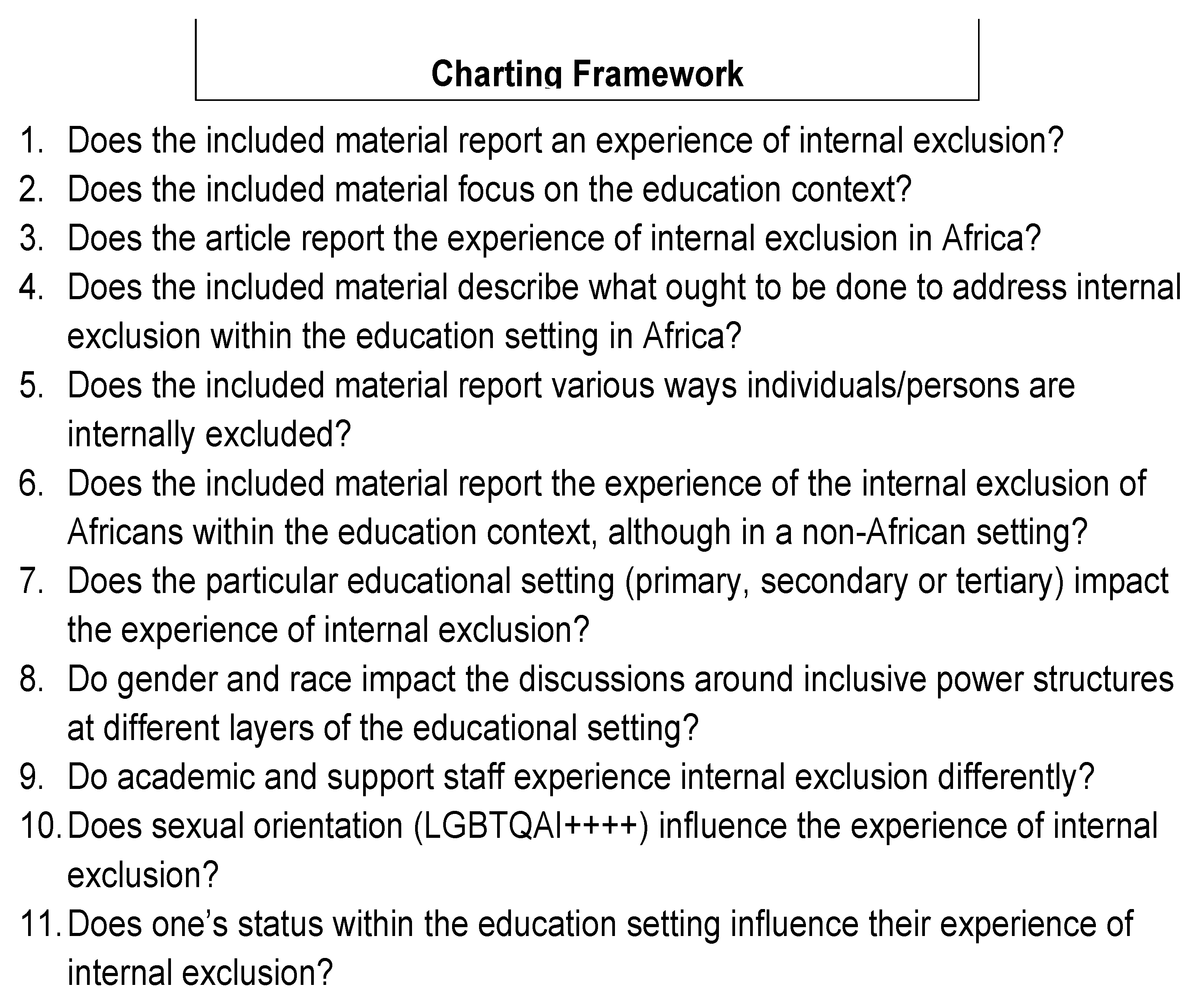

2.3. Data Organization, Extraction, and Content Analyses

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Internal Exclusion, External Inclusion and External Exclusion

3.3. Sites of Internal Exclusion

3.4. Physical Activities

3.5. Othering

3.6. Epistemic De-Rooting

3.7. Language of Competence and Standard

3.8. Policies as a Site of Internal Exclusion

3.9. Space as a Site of Internal Exclusion

3.10. Antidotes to Internal Exclusion

3.11. Addressing Policy as a Site of Internal Exclusion

3.12. How to Address Epistemological De-Rooting

3.13. The Antidote to the Language of Competence and Standard

3.14. Countering Other Forms of Internal Exclusion: Agency

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Literature Search | |

|---|---|

| PubMed | 1st Search |

| Search Date: 12 August 2022 Selected Restrictions: no restriction selected Filters selected: Best Match Search String:

Selected after title and abstract screening: 61 Selected: 48 | |

| PubMed | Additional Search |

| Search date: 12 July 2024 Selected Restrictions: no restriction selected Filters selected: Best Match Search string: (((Inclusive OR inclusivity OR inclusion) AND (exclusive OR exclusivity OR exclusion OR “internal exclusion”)) AND (education)) AND (African OR Africa OR ubuntu) Hits: 45 Selected after title and abstract screening: 2 | |

| PhilPapers | 1st Search |

| Search Date: 18 August 2022 Selected Restrictions: no restriction selected Search Mode: Default mode: sort by relevance Search String: ((Internal exclusion) AND (education)) AND (Africa) Hits: 4 Selected after the title and abstract reading: 2 | |

| PhilPapers | 2nd Search |

| Search Date: 18 August 2022 Selected Restrictions: no restriction selected Search Mode: Default mode: sort by relevance Search String: ((exclusion) AND (education)) AND (Africa) Hits: 13 Selected after title and abstract reading: 2 | |

| PhilPapers | Additional search |

| Search Date: 12 July 2024 Selected Restrictions: no restriction selected Search Mode: Default mode: sort by relevance Search String: ((exclusion) AND (education)) AND (Africa) Hits: 22 Selected after title and abstract reading: 3 | |

| Google Scholar | 1st Search |

| Search Date: 22 August 2022 Selected Restrictions: no restriction selected Search Mode: Best Match Search String: ((Internal exclusion OR inclusion) AND (education)) AND (Africa) Hits: 310 Selected after title and abstract reading: 47 | |

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

| No. | Names of Authors | Year | Study Type | Study Description | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joseph Agbenyega | 2007 | Journal article | Qualitative | Examining teachers’ concerns and attitudes to inclusive education in Ghana |

| 2 | Simplice Asongu and Nicholas Odhiambo | 2021 | Journal article | Qualitative | Thresholds of income inequality that mitigate the role of gender inclusive education in promoting gender economic inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa |

| 3 | Jason Bantjes and colleagues | 2015 | Journal article | Qualitative | “There is soccer but we have to watch”: The embodied consequences of rhetorics of inclusion for South African children with cerebral palsy |

| 4 | Gia Elise Barboza | 2015 | Journal article | Qualitative | The association between school exclusion, delinquency and subtypes of cyber- and F2F-victimizations: Identifying and predicting risk profiles and subtypes using latent class analysis |

| 5 | Eugene Baron | 2020 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Mission studies at South African higher education institutions: An ethical and decolonial perspective in the quest to colour the discipline |

| 6 | Diane Bell and Estelle Swart | 2018 | Journal article | Qualitative | Learning experiences of students who are hard of hearing in higher education: Case study of a South Africa university |

| 7 | Edvina Besic and colleagues | 2020 | Journal article | Qualitative | Refugee students’ perspectives on inclusive and exclusive school experiences in Austria |

| 8 | Micheal Breen and colleagues | 2022 | Journal article | Qualitative | Diversity, equity and inclusion: A survey of pediatric radiology fellowship graduates from 1996–2020 |

| 9 | Melissa Brottman and colleagues | 2020 | Journal article | Qualitative | Toward cultural competency in Health care: A scoping review of the diversity and inclusion education literature |

| 10 | Johan Buitendag | 2020 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Ecodomy as education in tertiary institutions. Teaching theology and religion in a globalized world: African perspectives |

| 11 | Desire Chiwandire and Louise Vincent | 2017 | Journal article | Qualitative | Wheelchair users, access and exclusion in South African higher education |

| 12 | Svjetlana Curcic | 2009 | Journal article | Qualitative and quantitative | Inclusion in PK-12: An international perspective |

| 13 | Elizabeth Dalton and colleagues | 2012 | Journal article | Qualitative | The implementation of inclusive education in South Africa: Reflections arising from a workshop for teachers and therapists to introduce universal design for learning |

| 14 | Fionnuala Darby | 2018 | Journal article | Qualitative | Belonging at ITB: The use of photovoice methodology (PVM) to investigate inclusion and exclusion at ITB based on ethnicity and nationality from a student perspective |

| 15 | Nuraan Davids and Yusef Waghid | 2019 | Book chapter | Conceptual work | Teacher exclusion in post-apartheid schools: On being competently (un)qualified to teach |

| 16 | Nuuran Davids | 2019 | Journal article | Conceptual work | You are not like us: on teacher exclusion, imagination and disruption perception |

| 17 | Curtiland Deville and colleagues | 2020 | Journal article | Qualitative | I can’t breath: The continued disproportionate exclusion of black physicians in the United States radiation oncology workforce |

| 18 | Nina du Toit | 2018 | Journal article | Qualitative | Designing a model for facilitating the inclusion of higher education international students with disabilities in South Africa |

| 19 | Ikenna Ebuenyi and colleagues | 2020 | Journal article | Qualitative | Challenges of inclusion: A qualitative study exploring barriers and pathways to inclusion of persons with mental disabilities in technical and vocational education and training programmes in East Africa |

| 20 | Paul Emong and Lawrence Eron | 2016 | Journal article | Qualitative | Disability inclusion in higher education in Uganda: Status and strategies |

| 21 | Petra Engelbrecht and colleagues | 2015 | Journal article | Qualitative | Enacting understanding of inclusion in complex contexts: Classroom practices of South African teachers |

| 22 | A.J Greyling | 2009 | Journal article | Qualitative | Reaching for the dream: Quality education for all |

| 23 | Suchitra Gururaj and colleagues | 2021 | Journal article | Qualitative | Affirmative action policy: Inclusion, exclusion and the global public good |

| 24 | Rob Higham | 2012 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Place, race and exclusion: University student voices in post-apartheid South Africa |

| 25 | Timothy Hodgson | 2018 | Journal article | Conceptual work | The right to inclusive education in South Africa: Recreating disability apartheid through failed inclusion policies |

| 26 | Emma Jolley and colleagues | 2018 | Journal article | Qualitative | Education and social inclusion of people with disabilities in five countries in West Africa: A literature review |

| 27 | Leila Kajee | 2010 | Journal article | Qualitative | Disability, social inclusion and technological positioning in a South African higher education institution: Carmen’s story |

| 28 | Gubela Mji and colleagues | 2017 | Book chapter | Conceptual work | Indigenous knowledge exclusion in education systems of Africans: Impact of beingness and becoming an African |

| 29 | Shirley Key | 2000 | Journal article | Conceptual work | To what extent is cultural inclusion an integral element in South Africa’s new education initiative? |

| 30 | Kimberly King | 2001 | Journal article | Conceptual work | From numerical to comprehensive inclusion: utilizing experiences in the USA and South Africa to conceptualize a multicultural environment |

| 31 | Anthony Lemon | 2005 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Shifting geographies of social inclusion and exclusion: Secondary education in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa |

| 32 | S. Liccardo | Journal article | Qualitative | A symbol of infinite (be)longing: Psychosocial rhythms of inclusion and exclusion at South African universities | |

| 33 | Tawanda Majoko | 2016 | Journal article | Qualitative | Inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorders: Listening and hearing to voices from the grassroots |

| 34 | T.M Makoelle and M.J Malindi | 2014 | Journal article | Qualitative | Multi-grade teaching and inclusion: Selected cases in the Free State province of South Africa |

| 35 | Thaddeus Metz | 2019 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Neither parochial nor cosmopolitan: Cultural instruction in the light of an African communal ethic |

| 36 | Robert Morrell | 2016 | Journal article | Qualitative | Making southern theory? Gender researchers in South Africa |

| 37 | Macdelyn Mosalagae and Tanya Bekker | 2021 | Journal article | Qualitative | Education of students with intellectual disabilities at technical vocational education and training institutions in Botswana: inclusion or exclusion? |

| 38 | Lincolyn Moyo and Lillie Hadebe | 2018 | Journal article | Qualitative | Inclusion of African philosophy in contemporary African education systems as a key philosophical orientation in teacher training and educational ideology |

| 39 | Proscovia Nantongo | 2019 | Journal article | Qualitative | Framing heuristics in inclusive education: The case of Uganda’s preservice teacher education programme |

| 40 | Amasa Ndofirepi and Ephrain Gwaravanda | 2020 | Book chapter | Conceptual | Inclusion and social justice |

| 41 | Patrao Neves and J P Batista | 2021 | Journal article | Conceptual | Biomedical ethics and regulatory capacity building partnership for Portuguese-speaking African countries (BERC-Luso): A pioneering project |

| 42 | Jabulani Ngcobo and Nithi Muthukrishna | 2011 | Journal article | Qualitative | The geographies of inclusion of students with disabilities in an ordinary school |

| 43 | Shirley Pendlebury and Penny Enslin | 2004 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Social justice and inclusion in education and politics: The South African case |

| 44 | Michelle Pentecost and colleagues | 2018 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Critical orientations for humanizing health sciences education in South Africa |

| 45 | Jace Pillay | 2020 | Book chapter | Conceptual work | The education, inclusion, and development of orphans and vulnerable children: Crucial aspects for governance in Africa |

| 46 | Louise Postma and colleagues | 2013 | Journal article | Qualitative | Reflections on the use of grounded theory to uncover patterns of exclusion in an online discussion forum at an institution of higher education |

| 47 | Richard Rose and colleagues | 2019 | Book chapter | Conceptual work | Developing inclusive education policy in Sierra Leone: A research informed approach |

| 48 | Yusuf Sayed and Crain Soudien | 2005 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Decentralization and the construction of inclusion education policy in South Africa |

| 49 | Rachel Shanyanana | 2016 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Reconceptualizing Ubuntu as inclusion in African higher education: Towards equalization of voice |

| 50 | Paul Smeyers and colleagues | 2014 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Publish yet perish: On the pitfalls of philosophy of education in an age of impact factors |

| 51 | Crain Soudien and Yusuf Sayed | 2004 | Journal article | Conceptual work | A new racial state? Exclusion and inclusion in education policy and practice in South Africa |

| 52 | Sharlene Swartz and colleagues | 2022 | Journal article | Qualitative | Cultivating moral eyes: Bridging the knowledge-action gap of privilege and injustice among students in African universities |

| 53 | JoAnn Trejo | 2020 | Journal article | Conceptual work | The burden of service for faculty of colour to achieve diversity and inclusion: The minority tax |

| 54 | Carla Tsampiras | 2018 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Walking up hills, through history and in-between disciplines: MHH and health sciences education at the tip of Africa |

| 55 | Samson Tsegay | 2016 | Journal article | Qualitative | ICT for post-2015 education: An analysis of access and inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa |

| 56 | Shelley wally and Katherine Troisi | 2020 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Impact of gender bias on women surgeons: A South African perspective |

| 57 | Elizabeth Walton and colleagues | 2009 | Journal article | Qualitative and quantitative | The extent and practice of inclusion in independent schools in South Africa |

| 58 | Elizabeth Walton | 2011 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Getting inclusion right in South Africa |

| 59 | Emnet Woldegiorgis | 2021 | Journal article | Conceptual work | Decolonizing a higher education system which has never been colonized |

| 60 | Tsion Yohannes and colleagues | 2021 | Journal article | Qualitative | A gender and diversity inclusion audit at the university of global health equity, Rwanda |

| 61 | Roderick Zimba | 2010 | Conference paper | Conceptual | Review of current educational policies and practices on the inclusion-exclusion paradigm: The case of the Namibian education system |

| 62 | Jaysson Brooks and colleagues | 2024 | Journal article | Qualitative | The majority of black orthopaedic surgeons report experiencing racial microaggressions during their residency |

| 63 | Nuraan Davids | 2023 | Journal article | Conceptual | Governance as subversion of democratization in South African schools |

| 64 | Nuraan Davids | 2024 | Journal article | Conceptual | Decolonization in South Africa universities: Storytelling as subversion and reclamation |

| 65 | Helen Church | 2023 | Journal article | Qualitative | Beyond the bedside: Protocol for a scoping review exploring the experiences of non-practicing healthcare professionals within health professions education |

| 66 | Brian Watermeyer and colleagues | 2024 | Journal article | Conceptual | Visual impairment, inclusion and citizenship in South Africa |

References

- Atuire, C.; Rutazibwa, O. An African Reading of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Stakes of Decolonization. In An African Reading of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Stakes of Decolonization; Yale Law School: New Haven, CT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ewuoso, C. Decolonial health literature can increase our thinking about ethics dumping. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2023, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic justice as a condition of political freedom? Synthese 2013, 190, 1317–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambra, G.K. Decolonizing Critical Theory? Epistemological Justice, Progress, Reparations. Crit. Times 2021, 4, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, G.R.; FireMoon, P.; Anastario, M.P.; Ricker, A.; Thunder, R.E.-G.; Baldwin, J.A.; Rink, E. Indigenous standpoint theory as a theoretical framework for decolonizing social science health research with American Indian communities. AlterNative (Nga Pae Maramatanga (Organ)) 2021, 17, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamnjoh, A.-N.; Ewuoso, C. What type of inclusion does epistemic injustice require? J. Med. Ethics 2023, 2023, 109091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.S.; Gracia, J.N. Addressing health and health-care disparities: The role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129 (Suppl. S2), 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, S.M.; Haider, S.; Williams, C.R.; Mazumder, Y.; Ibisomi, L.; Alonge, O.; Theobald, S.; Bärnighausen, T.; Escallon, J.V.; Vahedi, M.; et al. Diversifying Implementation Science: A Global Perspective. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2022, 10, e2100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.L. From numerical to comprehensive inclusion: Utilizing experiences in the USA and South Africa to conceptualize a multicultural environment. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2001, 5, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantjes, J.; Swartz, L.; Conchar, L.; Derman, W. “There is soccer but we have to watch”: The embodied consequences of rhetorics of inclusion for South African children with cerebral palsy. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 25, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, R. Place, race and exclusion: University student voices in post-apartheid South Africa. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2012, 16, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, T. Neither parochial nor cosmopolitan: Cultural instruction in the light of an African communal ethic. Educ. Change 2019, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davids, N. You are not like us: On teacher exclusion, imagination and disrupting perception. J. Philos. Educ. 2019, 53, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, M. Inclusion/exclusion: Educational closure and social differentiation in world society. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 20, 758–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, M.; Hormel, U. Unequal inclusion: The production of social differences in education systems. Soc. Incl. 2021, 9, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Collins, J.; Benjamin, S.; Nind, M.; Sheehy, K. SATurated models of pupildom: Assessment and inclusion/exclusion. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2004, 30, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damianidou, E. Curriculum and the power to ex(in)clude disabled students. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2024, 28, 1435–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Miranda, J.M.; Madariaga, M.N. La voz de los estudiantes en riesgo de abandono escolar Su visión sobre el profesorado. Perfiles Educ. 2020, 42, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, R.O.; Little, S. Caste and control in schools: A systematic review of the pathways, rates and correlates of exclusion due to school discipline. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 94, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, S.A.; Schneider, S. Excluding students from school: A re-examination from a children’s rights perspective. Int. J. Child. Rights 2013, 21, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndimande, B.S. Persistent Exclusions in Postapartheid Education: Experiences of Black Parents. In Beyond Pedagogies of Exclusion in Diverse Childhood Contexts: Transnational Challenges; Mitakidou, S., Tressou, E., Swadener, B., Grant, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, Y.; Soudien, C. Decentralisation and the construction of inclusion education policy in South Africa. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2005, 35, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešić, E.; Paleczek, L.; Krammer, M.; Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. Inclusive practices at the teacher and class level: The experts’ view. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajee, L. Disability, social inclusion and technological positioning in a South African higher education institution: Carmen’s story. Lang. Learn. J. 2010, 38, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudien, C.; Sayed, Y. A new racial state? Exclusion and inclusion in education policy and practice in South Africa: Conversations. Perspect. Educ. 2004, 22, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Straus, S.E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Emmanuel, P. Formulating a researchable question: A critical step for facilitating good clinical research. Indian. J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS 2010, 31, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.R.; Morales, C. Approximation to the concept of responsibility in Lévinas: Educational implications. Bordon 2012, 64, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, M.; Camicia, S. Transnational civic education and emergent bilinguals in a dual language setting. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhena, F.C.; Bencivenga, R.; Belloso, M.L.; Leone, C.; Taramasso, A.C. Participatory Strategies to Integrate Gender+ Into Teaching and Research. Int. Conf. Gend. Res. 2024, 7, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gururaj, S.; Somers, P.; Fry, J.; Watson, D.; Cicero, F.; Morosini, M.; Zamora, J. Affirmative action policy: Inclusion, exclusion, and the global public good. Policy Futures Educ. 2021, 19, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcic, S. Inclusion in PK-12: An international perspective. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2009, 13, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, F. Belonging at ITB: The use of photovoice methodology (PVM) to investigate inclusion and exclusion at ITB based on ethnicity and nationality from a student perspective. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2018, 256, 611–623. [Google Scholar]

- Bešić, E.; Gasteiger-Klicpera, B.; Buchart, C.; Hafner, J.; Stefitz, E. Refugee students’ perspectives on inclusive and exclusive school experiences in Austria. Int. J. Psychol. 2020, 55, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, M.A.; Melvin, P.; Choura, J.; Tennermann, N.; Ward, V.L. Diversity, equity and inclusion: A survey of pediatric radiology fellowship graduates from 1996 to 2020. Pediatr. Radiol. 2022, 52, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deville, C., Jr.; Cruickshank, I.; Chapman, C.H.; Hwang, W.-T.; Wyse, R.; Ahmed, A.A.; Winkfield, K.M.; Thomas, C.R.; Gibbs, I.C. I Can’t Breathe: The Continued Disproportionate Exclusion of Black Physicians in the United States Radiation Oncology Workforce. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 108, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo, J. The burden of service for faculty of color to achieve diversity and inclusion: The minority tax. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 2752–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanyanana, R.; Waghid, Y. Reconceptualizing ubuntu as inclusion in African higher education: Towards equalization of voice. Knowl. Cult. 2016, 4, 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Davids, N.; Waghid, Y. Teacher exclusion in post-apartheid schools: On being competently (un) qualified to teach. In Handbook of Innovative Career Counselling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ngcobo, J.; Muthukrishna, N. The geographies of inclusion of students with disabilities in an ordinary school. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2011, 31, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantongo, P.S. Framing heuristics in inclusive education: The case of Uganda’s preservice teacher education programme. Afr. J. Disabil. 2019, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, S.; Enslin, P. Social justice and inclusion in education and politics: The South African case. J. Educ. 2004, 34, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, L.; Blignaut, A.S.; Swan, K.; Sutinen, E.A. Reflections on the use of grounded theory to uncover patterns of exclusion in an online discussion forum at an institution of higher education. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, P.; Nel, M.; Nel, N.; Tlale, D. Enacting understanding of inclusion in complex contexts: Classroom practices of South African teachers. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2015, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosalagae, M.; Bekker, T.L. Education of students with intellectual disabilities at Technical Vocational Education and Training institutions in Botswana: Inclusion or exclusion? Afr. J. Disabil. 2021, 10, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mji, G.; Kalenga, R.; Ned, L.; Alperstein, M.; Banda, D. Indigenous knowledge exclusion in education systems of africans: Impact of beingness and becoming an African. In African Studies: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice; IGI Global: Hershey, PN, USA, 2020; pp. 510–533. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, L.; Hadebe, L.B. Inclusion of African philosophy in contemporary African education systems as a key philosophical orientation in teacher training and educational ideology. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2018, 4, 1154939. [Google Scholar]

- Liccardo, S. A symbol of infinite (be) longing: Psychosocial rhythms of inclusion and exclusion at South African universities. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2018, 32, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, E. Mission studies at South African higher education institutions: An ethical and decolonial perspective in the quest to ‘colour’ the discipline. HTS Teol. Stud./Theol. Stud. 2020, 2020, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyling, A.J. Reaching for the dream: Quality education for all. Educ. Stud. 2009, 35, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeyers, P.; de Ruyter, D.J.; Waghid, Y.; Strand, T. Publish Yet Perish: On the Pitfalls of Philosophy of Education in an Age of Impact Factors. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2014, 33, 647–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pentecost, M.; Gerber, B.; Wainwright, M.; Cousins, T. Critical orientations for humanising health sciences education in South Africa. Med. Humanit. 2018, 44, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldegiorgis, E.T. Decolonising a higher education system which has never been colonised’. Educ. Philos. Theory 2021, 53, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsampiras, C. Walking up hills, through history and in-between disciplines: MHH and Health Sciences Education at the tip of Africa. Med. Humanit. 2018, 44, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D.; Swart, E. Learning experiences of students who are hard of hearing in higher education: Case study of a South African university. Soc. Incl. 2018, 6, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwandire, D.; Vincent, L. Wheelchair users, access and exclusion in South African higher education. Afr. J. Disabil. 2017, 6, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsegay, S.M. ICT for post-2015 education: An analysis of access and inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. Technol. 2016, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, S.; Nyamnjoh, A.; Arogundade, E.; Breakey, J.; Bockarie, A.; Osezua, O.C. Cultivating moral eyes: Bridging the knowledge-action gap of privilege and injustice among students in African universities. J. Moral. Educ. 2022, 51, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, S.L.; Troisi, K. Impact of gender bias on women surgeons: A South African perspective. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 46, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.; Odhiambo, N. Thresholds of income inequality that mitigate the role of gender inclusive education in promoting gender economic inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2012; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Zimba, R.F. Review of Current Educational Policies and Practices on the Inclusion-Exclusion Paradigm: The Case of the Namibian Education System. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Inclusive Education in Higher Education, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon, 26–29 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yohannes, T.; Umucyo, D.; Binagwaho, A. A gender and diversity inclusion audit at the University of Global Health Equity, Rwanda. J. Gend. Stud. 2022, 31, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brottman, M.R.; Char, D.M.; Hattori, R.A.; Heeb, R.; Taff, S.D. Toward Cultural Competency in Health Care: A Scoping Review of the Diversity and Inclusion Education Literature. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, S.G. To What Extent is Cultural Inclusion an Integral Element in South Africa’s New Education Initiative? Int. J. Educ. Reform. 2000, 9, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndofirepi, A.; Gwaravanda, E.T. Inclusion and Social Justice: Creating Space for African Epistemologies in the African University. In Inclusion as Social Justice; Brill Sense: Paderborn, Germany, 2020; pp. 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Buitendag, J.; Simu, C.C. Ecodomy as education in tertiary institutions. Teaching theology and religion in a globalised world: African perspectives. HTS Theol. Stud. 2020, 76, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalwamba, K.M.B.; Buitendag, J. Vital force as a triangulated concept of nature and s(S)pirit. HTS Theol. Stud. 2017, 73, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, G. The association between school exclusion, delinquency and subtypes of cyber- and F2F-victimizations: Identifying and predicting risk profiles and subtypes using latent class analysis. Child Abuse Negl. J. 2015, 39, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbenyega, J. Examining Teachers’ Concerns and Attitudes to Inclusive Education in Ghana. Int. J. Whole Sch. 2007, 3, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Makoelle, T.M.; Malindi, M.J. Multi-Grade Teaching and Inclusion: Selected Cases in the Free State Province of South Africa. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2014, 7, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Odongo, C.O.; Talbert-Slagle, K. Training the next generation of Africa’s doctors: Why medical schools should embrace the team-based learning pedagogy. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, K.G. Towards an Indigenous African Bioethics. S. Afr. J. Bioeth. Law. 2013, 6, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebuenyi, I.D.; Smith, E.M.; Munthali, A.; Msowoya, S.W.; Kafumba, J.; Jamali, M.Z.; MacLachlan, M. Exploring equity and inclusion in Malawi’s National Disability Mainstreaming Strategy and Implementation Plan. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union African; UNICEF. Transforming Education in Africa: An Evidence-Based Overview and Recommendations for Long-Term Improvements; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; African Union: Durban, South Africa, 2021; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ewuoso, C.; Ogundiran, T. The Experience of Internal Exclusion Within the Context of Education in Africa: A Scoping Review of the Views of Philosophers of Education and Educationists. Societies 2025, 15, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050116

Ewuoso C, Ogundiran T. The Experience of Internal Exclusion Within the Context of Education in Africa: A Scoping Review of the Views of Philosophers of Education and Educationists. Societies. 2025; 15(5):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050116

Chicago/Turabian StyleEwuoso, Cornelius, and Temidayo Ogundiran. 2025. "The Experience of Internal Exclusion Within the Context of Education in Africa: A Scoping Review of the Views of Philosophers of Education and Educationists" Societies 15, no. 5: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050116

APA StyleEwuoso, C., & Ogundiran, T. (2025). The Experience of Internal Exclusion Within the Context of Education in Africa: A Scoping Review of the Views of Philosophers of Education and Educationists. Societies, 15(5), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050116