1. Introduction

Since the Salamanca Statement [

1], inclusive education has been consolidated as a fundamental principle in global education policies, recognising universal access to education as a basic right. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) [

2] defines this approach as a process that responds to the diverse needs of all learners, encouraging their participation and reducing exclusion. Inclusive education is therefore conceived as a transformative process in educational culture, policies and practices, aimed at providing equitable provision that is responsive to the diverse needs and characteristics of learners [

3].

The importance of mainstream educational institutions with an inclusive orientation should be emphasised, as they are considered the most effective means of combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, and achieving education for all [

4].

Inclusive education has been conceptualised in different ways across countries, with varying approaches, strategies and understandings of diversity. These conceptualisations have significant implications for its development, as they influence how teachers and institutions respond to learners’ needs. Depending on educational policies and practices, inclusion may either be promoted or constrained [

5].

For instance, in Austria, diversity is mainly associated with disability and linguistic difference. In Portugal, a broader perspective encompasses interculturality and citizenship. In England, diversity is framed through an extensive list of categories, including age, gender and ethnicity. In Denmark, it is linked to differentiated teaching, while in Spain it is often regarded primarily as a problem to be addressed [

6].

In Latin America, countries such as Colombia, Bolivia and Chile have faced limitations in the effectiveness and implementation of inclusive policies [

7]. The lack of robust research and policy frameworks has contributed to lower access rates and greater barriers to retention and graduation for students with disabilities [

8]. Bolivia maintains a tradition of free access to higher education [

9], while in Chile, certain universities have adopted direct access policies and support services. However, these initiatives are not always evaluated in terms of pedagogical practices and learning outcomes for the prioritised student population [

10].

One of the main challenges in implementing inclusive education lies in pedagogical practices. Variations in such practices are particularly marked across institutions and disciplinary fields, highlighting the crucial role of academic training and qualification schemes for teaching staff [

11]. In higher education, professional development in inclusive methodologies is especially important, given that professors often come from diverse disciplinary backgrounds where inclusive approaches are not systematically addressed [

12]. In both Europe and Latin America, university professors—many of whom are not trained educators—face challenges and professional pressures in developing their teaching roles [

13].

Inclusive methodologies are vital for improving the academic performance and participation of students with disabilities in higher education. These include Universal Design for Learning (UDL), supportive learning, assistive technologies and personalised formative assessment—all reflecting a commitment to equity and inclusion [

14]. Moreover, it is essential that both professors and institutional leaders embrace a diversity-oriented approach, recognising that inclusion is not restricted to students with disabilities but extends to all learners vulnerable to exclusion [

15]. Achieving this requires school leaders to work collaboratively with colleagues to foster an inclusive culture, harness student diversity and promote inclusive practices in universities [

16].

In Colombia, Law 1618 of 2013 stresses the importance of ongoing teacher training to ensure educational inclusion [

17]. Nationally, inclusive education is framed as a continuous process that seeks to respond to student diversity, supporting their development and participation in a shared educational environment without exclusion [

18]. Decree 1421 of 2017 further regulates educational provision for learners with disabilities, assigning responsibilities to various entities to guarantee quality education [

19].

Despite legislative advances, many people with disabilities continue to encounter barriers to accessing education [

20]. Among the most critical obstacles are attitudinal barriers and issues related to educational leadership. Research has highlighted strengths, such as inclusive leadership, but also weaknesses, including limited community engagement [

21]. Furthermore, studies show that future teachers often display a limited willingness to engage with diversity, despite perceiving themselves as competent [

22]. At the university level, traditional approaches to disability still persist, underscoring the urgent need to update the training of academic staff [

23].

The effectiveness of inclusive education remains a matter of debate. While some authors highlight its academic and social benefits, others argue that inclusive education is not always good practice [

24], or emphasise difficulties related to insufficient resources, inadequate infrastructure and limited specialised teacher training [

25].

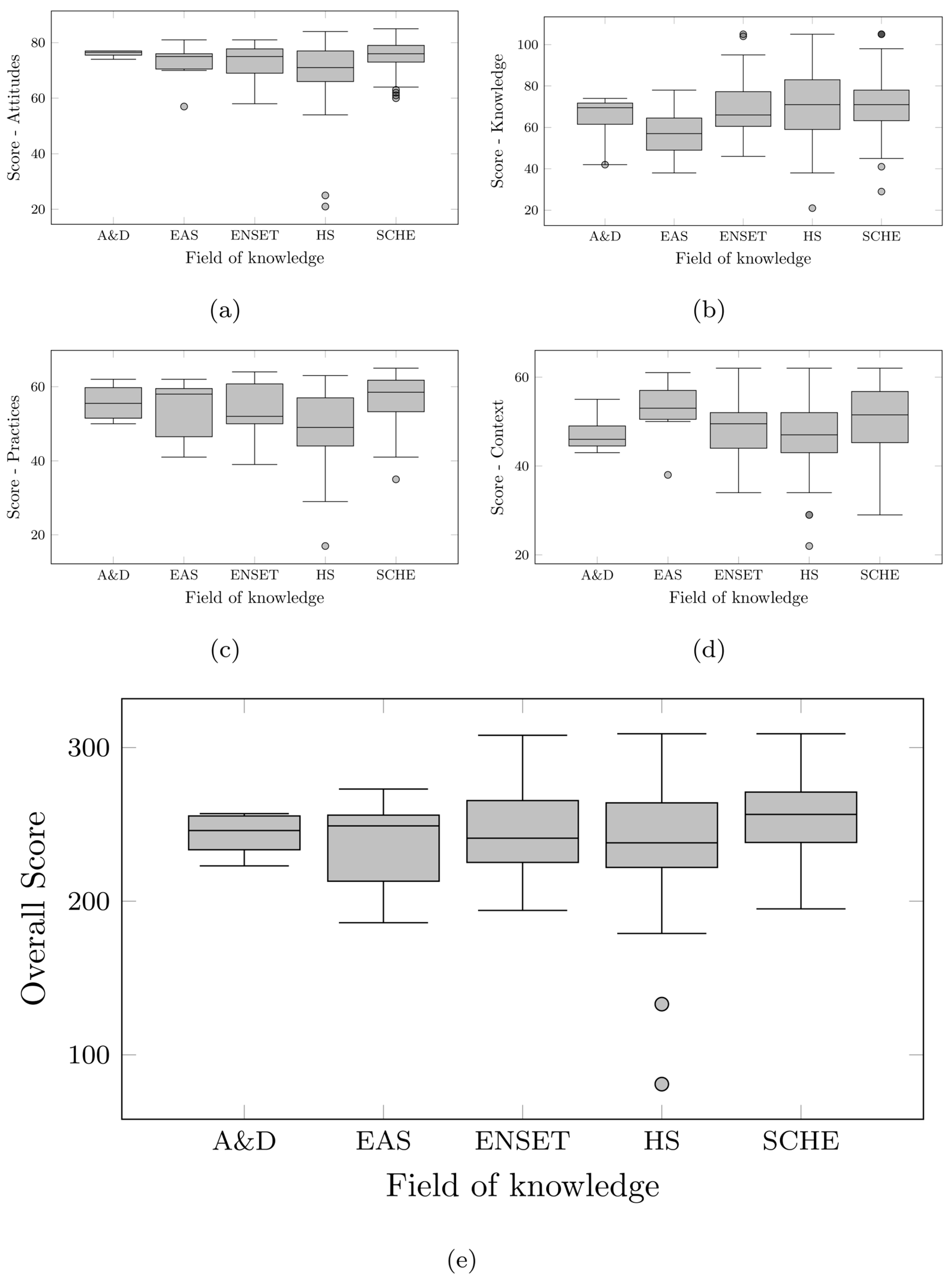

This study aims to analyse the development of inclusive education dimensions across academic and disciplinary profiles of professors from two selected Colombian higher education institutions. The aim is to identify strengths and areas for improvement, to gain a deeper understanding of the national situation of inclusive education, and to recognise international good practices that may serve as a foundation for future higher education policies.

The literature review (see

Table 1) on the dimensions of inclusive education, including teacher attitudes, reveals that although there is a positive trend towards inclusion, substantial barriers persist. Many university professors express favourable attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities but face challenges such as insufficient training and limited resources [

26]. Furthermore, professors’ beliefs and perceptions about inclusion vary considerably, affecting the effective implementation of inclusive practices [

27]. Teachers’ attitudes are critical to the success of inclusion, as their disposition and empathy can positively influence classroom climate and the development of inclusive pedagogical practices [

28].

In terms of knowledge and practice, literature highlights the importance of continuous training and professional development for teachers in the field of inclusive education. Studies suggest that teachers need to improve their digital and pedagogical competences to effectively support students with disabilities [

35]. Successful inclusive practices include the use of assistive technologies, implementation of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) frameworks and instructional differentiation [

34]. However, the lack of resources and institutional support remains a major obstacle to the implementation of these practices [

36]. Collaboration between institutions, families and agencies is also mentioned as a key strategy to promote inclusion in higher education [

20].

Inclusive education in Colombia faces significant challenges, especially in terms of teacher training and the implementation of effective pedagogical practices. Although teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion are generally positive [

37], there is a notable discrepancy between these attitudes and actual classroom practices [

38]. The lack of specific training in inclusive education contributes to this disparity, as key terms such as Individual Reasonable Adjustments Plan (PIAR) and Universal Design for Learning (DUA) are unknown to 40% of teacher [

39]. Moreover, the training offered is often legislative and encyclopaedic, which limits teachers’ ability to apply trans-formative strategies in their daily practices [

30]. To overcome these barriers, it is essential to promote flexible curricula and comprehensive training programmes that address both the theory and practice of inclusive education [

40]. This is the only way to ensure quality and equitable education for all students, regardless of their conditions and needs [

37].

Finally, affirmative actions are key strategies for the reduction in inequalities in the university and social context [

41]. These actions include the implementation of public policies that promote equal access to higher education, the elimination of architectural, communicational and pedagogical barriers, and the development of specific support programmes for students recognised from the diversity approach or prioritized [

42]. This leads to the favourability of Educational Inclusion, which in the university context refers to the degree to which educational institutions promote and facilitate the inclusion of all students, regardless of their conditions and needs.

2. Materials and Methods

The study is framed within the positivist paradigm, non-experimental, cross-sectional and descriptive–comparative design, which allowed us to observe the variables without manipulation, collect data at a single time point and compare dimensions of inclusive education according to the academic and disciplinary profiles of the teachers [

43]. This methodology favours obtaining objective, replicable and generalisable results, suitable for describing and contrasting educational phenomena in their natural context [

44].

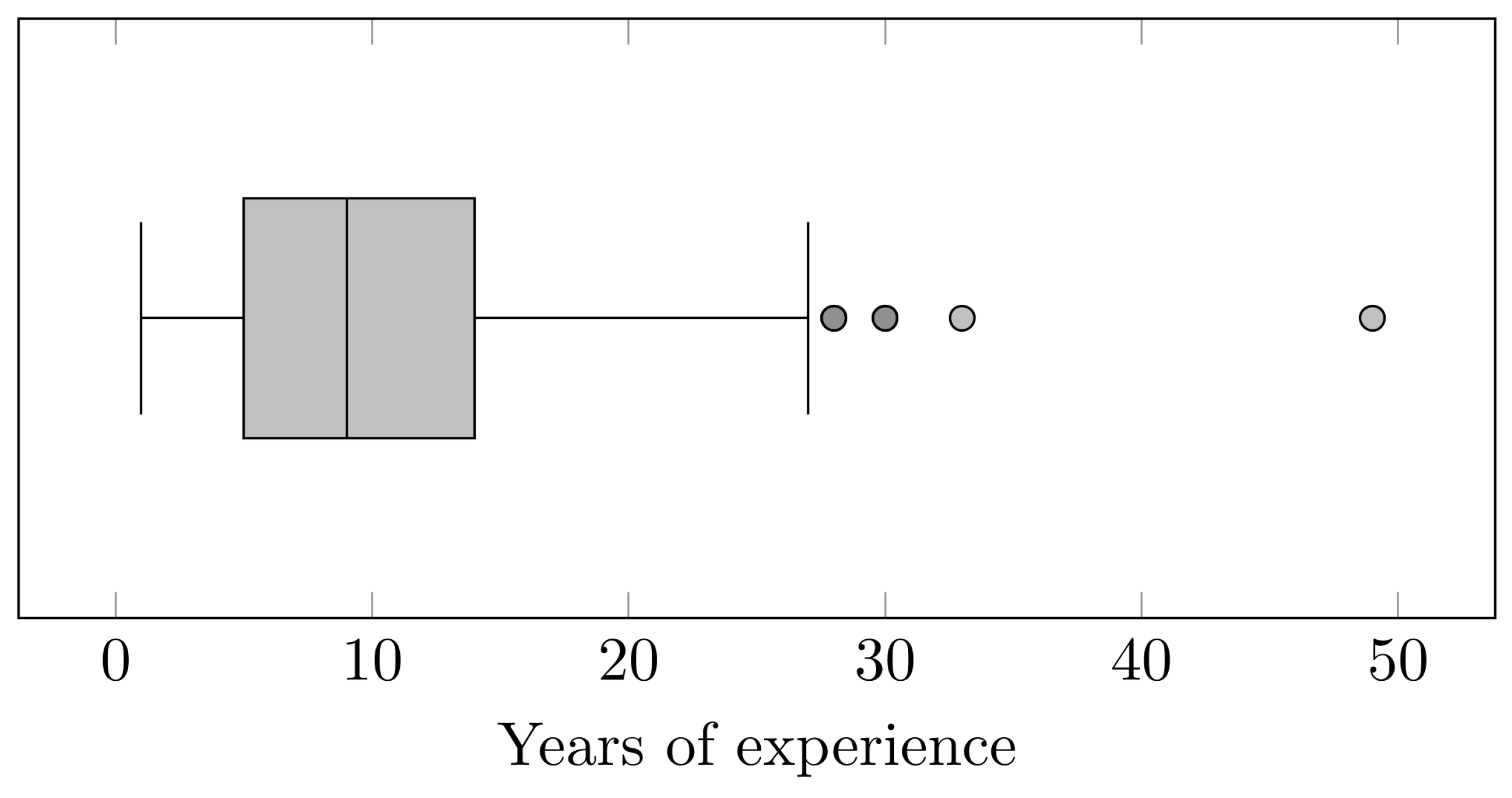

The study sample consisted of 212 teachers from two higher education institutions in Colombia, members of the Network of Universities for Disability (RedCiesd). The participants came from six cities in the country and were linked to the Faculties of Social and Legal Sciences, as well as Health Sciences. A non-probabilistic convenience sample was used, which made it possible to form a preliminary exploratory sample, made up of university professors who participated voluntarily after being called by the Pedagogy departments of the two participating universities and their respective educational centres [

45]. The inclusion criteria established were: (a) having an active contractual relationship during the year 2024 and (b) expressing willingness to participate in the study.

Data collection was carried out through the questionnaire of educational inclusion (CIE) for university contexts [

46], applied through the web-based SurveyMonkey platform (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA). The use of digital platforms such as SurveyMonkey provides logistical and methodological advantages, including geographical coverage and efficiency in data collection [

47].

The questionnaire was structured in two sections: a first one with socio-demographic data (institution, academic level, field of knowledge, among others) and a second one with the five dimensions of inclusive education contemplated in the operationalization of the CEI, which allow estimating the degree of agreement or frequency of teaching performance in inclusive university contexts (see

Table 2).

2.1. Procedure and Ethical Considerations

The procedure began with the submission of the project to an internal call for research, which enabled formal approval and authorisation for its execution to be obtained, in accordance with the guidelines established by the ethics committees of the participating institutions (Project code: 013008086-2022-311). Subsequently, a digital survey was designed based on the previously validated instrument, followed by a process of awareness-raising and coordination with the pedagogy departments of the universities involved. The questionnaire was distributed by sending institutional e-mails to teachers, within the framework of an open call.

Data collection was carried out between February and March 2024. At the end of this stage, the data were downloaded, cleaned and coded according to the dimensions established in the instrument. The anonymity and confidentiality of participants was guaranteed throughout the process, in compliance with the ethical principles of scientific research [

48] and international guidelines for good practice in research involving human subjects [

49]. Participants signed an informed consent form, in which they authorised the use of their data for scientific and educational purposes only.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

The hypotheses put forward in the study were formulated from the quantitative approach, which allows us to establish relationships between variables and contrast empirical assumptions by means of statistical analysis.

H1:

The level of academic training of teachers significantly influences the development of inclusive education dimensions.

H2:

The field of knowledge in which teachers work has a differential impact on the dimensions assessed.

H3:

The dimensions assessed in the questionnaire have an asymmetric distribution in the Colombian university context.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using R statistical software, version 4.4, widely recognised for its flexibility and power in data processing in social and educational research [

50]. The analysis was structured in four phases:

Univariate descriptive statistics, using frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations, which made it possible to characterise the socio-demographic variables and the dimensions of the instrument.

Bivariate statistics, with the application of Student’s t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Spearman correlations, selected according to the nature of the data and compliance with assumptions of normality [

51].

Multivariate statistics, where associations between variables were explored through multiple correlation analysis, to identify relational patterns between academic dimensions and profiles.

Confirmatory factor analysis, with Varimax rotation, aimed at validating the internal structure of the instrument used.

2.4. Data Availability

The data are openly available in the Mendeley Data repository: Carrillo-Sierra, S.M., Manrique-Julio, J., Cerón-Bedoya, J., Vásquez-Henao, L.C., Fornaris, Z., & Rivera-Porras, D. (2025). Inclusion in higher education: A comparative analysis of attitudes, knowledge and teaching practices in universities (V1). Universidad Simón Bolívar.

https://doi.org/10.17632/gwtc9848dj.1 [

52].

5. Conclusions

The pattern of development of inclusive education dimensions in different academic and disciplinary profiles of teachers in higher education institutions in Colombia reveals significant variations in attitudes, knowledge, practices and context. In order to identify strengths and areas of improvement for inclusive education, the importance of strengthening teacher training in inclusive methodologies and promoting flexible curricula that address both the theory and practice of inclusive education is highlighted.

The comparative analysis shows that the development of inclusion in higher education is heterogeneous in terms of the attitudes, knowledge and practices of teachers and between universities, influenced by disciplinary, institutional and formative factors. While significant progress has been made in the positive disposition towards inclusion, challenges remain in the effective implementation of inclusive practices and in the appropriation of specific knowledge.

Teacher training in inclusion should be formulated with a comprehensive and contextualised approach and consider the multidisciplinary nature of the teaching staff, as well as promoting institutional policies that guarantee adequate conditions for a truly inclusive higher education.

Despite its limitations, including the sample imbalance between the two participating universities and the potential for social desirability bias inherent to self-reported data, this study provides valuable insights into the patterns of inclusive education dimensions among faculty in selected Colombian higher education institutions. The findings underscore the need for institutional policies that promote continuous and contextualized teacher training. Future research should build on these results by employing longitudinal and mixed-methods designs to better understand the causal factors influencing the development of inclusive practices and to assess their long-term impact.