Digital Media and Political Engagement: Shaping Youth Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors in Four European Societies

Abstract

1. Introduction

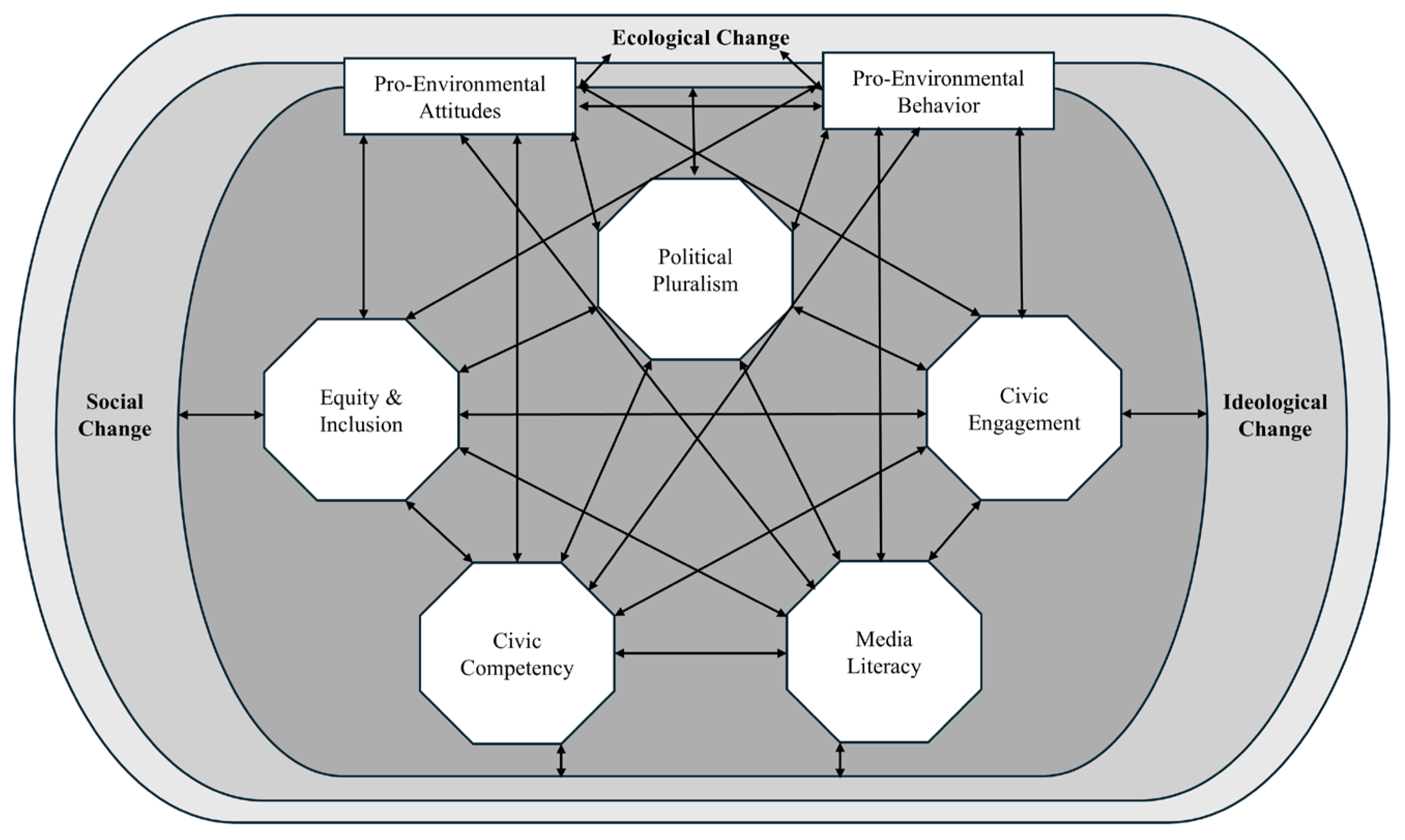

2. Conceptual Framework

“…the problem of anthropogenic climate change is political, not scientific. The science of climate change is information about the systems of the Earth and how they work; the politics of climate change is discourse and deliberation about what to do with information about how the systems of the Earth work. Thus, the problem of anthropogenic climate change is social; it is squarely in the domain of social studies education, even if the field has largely failed to acknowledge this reality”.(p. 4)

3. Literature Review

3.1. Pro-Environmental Attitudes

3.2. Pro-Environmental Behaviors

3.3. Civic Engagement and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors

3.3.1. Socioeconomic Status

3.3.2. Gender

3.3.3. Digital Media

4. Methods

4.1. Source of Data for Secondary Analysis

4.2. Participants

4.3. Measures

4.4. Students’ Positive Attitudes Toward Environmental Protection

Students’ Critical Views of the Political System

4.5. Students’ Reports on Expected Participation in Environmental Protection Activities

4.5.1. Students’ Citizenship Self-Efficacy

4.5.2. Students’ Engagement with Political or Social Issues Using Digital Media

4.6. Individual Factors Impacting Participants

4.6.1. National Index of Socioeconomic Background (SES)

4.6.2. Civic Knowledge—1st PV

4.6.3. Student Gender

5. Data Analysis

Multilevel Modeling

6. Results

6.1. Pro-Environmental Attitudes (PEA)

6.2. Pro-Environmental Behaviors (PEB)

7. Discussion

7.1. Context Matters

7.1.1. Digital Engagement

7.1.2. Socioeconomic Status

7.1.3. Critical Views and Spheres of Action

7.2. Directions for Future Research

7.3. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.M. Science and environmental education: Pious hopes, self praise and disciplinary chauvinism. Stud. Sci. Educ. 1980, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, J.A.; O’Connor, M. Environmental education and attitudes: Emotions and beliefs are what is needed. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Cooper, C.B.; Stedman, R.C.; Decker, D.J.; Gagnon, R.J. Place-based pathways to proenvironmental behavior: Empirical evidence for a conservation–recreation model. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E. Advancing Environmental Education Practice; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, S.M.; Sparkman, G.; Kraft-Todd, G.T.; Bicchieri, C.; Centola, D.; Shell-Duncan, B.; Vogt, S.; Weber, E.U. Scaling up change: A critical review and practical guide to harnessing social norms for climate action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2022, 23, 50–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zummo, L.; Gargroetzi, E.; Garcia, A. Youth voice on climate change: Using factor analysis to understand the intersection of science, politics, and emotion. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1207–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, T.P.; LeBlanc, R.J. Media education and the limits of “literacy”: Ecological orientations to performative platforms. Curric. Inq. 2021, 51, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestness, E.; McGinnis, J.R.; Breslyn, W. Examining the relationship between middle school students’ sociocultural participation and their ideas about climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.T.; Camicia, S.; Nelson, L. Education for democracy in the social media century. Res. Soc. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, H.; Lindtner, S.; Ytre-Arne, B. Polarisation and echo chambers? Making sense of the climate issue with social media in everyday life. Nord. Rev. 2023, 44, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calibeo, D.L.; Hindmarsh, R. From fake news to echo-chambers: On the limitations of new media for environmental activism in Australia, and “activist-responsive adaptation”. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, W.; Ainley, J.; Fraillon, J.; Losito, B.; Agrusti, G.; Damiani, V.; Friedman, T. Education for Citizenship in Times of Global Challenge: IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2022 International Report; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.nl/sites/default/files/2024-02/ICCS-2022-International-Report-Revised.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Mikuła, A.; Raczkowska, M.; Utzig, M. Pro-environmental behaviour in the European Union countries. Energies 2021, 14, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.L.; Busey, C.L.; Cuenca, A.; Evans, R.W.; Halvorsen, A.L.; Ho, L.C.; Kahne, J.; Kissling, M.T.; Lo, J.C.; McAvoy, P.; et al. Social studies education research for sustainable democratic societies: Addressing persistent civic challenges. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 2023, 51, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.T.; Torney-Purta, J.; Barber, C. Enhancing citizenship learning with international comparative research: Analyses of IEA civic education datasets. Citizsh. Teach. Learn. 2018, 13, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, M.; Rottman, J. The burden of climate action: How environmental responsibility is impacted by socioeconomic status. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 77, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.B.; Rice, R.E.; Gustafson, A.; Goldberg, M.H. Relationships among environmental attitudes, environmental efficacy, and pro-environmental behaviors across and within 11 countries. Environ. Behav. 2022, 54, 1063–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.-J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C. Analyzing differences between different types of pro-environmental behaviors: Do attitude intensity and type of knowledge matter? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, M.D.; Givens, J.E.; Hazboun, S.O.; Krannich, R.S. At home, in public, and in between: Gender differences in public, private and transportation pro-environmental behaviors in the US intermountain west. Environ. Sociol. 2019, 5, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Ng, P.; Kan, H.-K.; Fong, S.C. Does gender matter? Attitude towards waste charging policy and pro-environmental behaviours. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 1100–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Li, L.M.W. Societal gender role beliefs moderate the pattern of gender differences in public-and private-sphere pro-environmental behaviors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Bondell, H.D. The influence of personal beliefs, friends, and family in building climate change concern among adolescents. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 25, 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.; Oakley, J. Engaging the emotional dimensions of environmental education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Kiers, H.A. Measuring values in environmental research: A test of an environmental portrait value questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, F.X. Environmental values (2-MEV) and appreciation of nature. Sustainability 2018, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Szuster, B.W. The new environmental paradigm scale: Reassessing the operationalization of contemporary environmentalism. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 50, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma-Michilena, I.J.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Gil-Saura, I.; Belda-Miquel, S. Pro-environmental behaviours of generation Z: A cross-cultural approach. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2024, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Bhatti, W.A.; Glowik, M. The influence of cultural values on pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Vu, H.T.; Thaker, J.; Verner, M.; Goldberg, M.H.; Carman, J.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Leiserowitz, A. Variations in climate change belief systems across 110 geographic areas. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayne, K. Buds of collectivity: Student collaborative and system-oriented action towards greater socioenvironmental sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Ohnuma, S.; Blöbaum, A.; Matthies, E.; Sugiura, J. Determinants of individual and collective pro-environmental behaviors: Comparing Germany and Japan. J. Environ. Inf. Sci. 2010, 38, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Van der Werff, E.; Bouman, T.; Harder, M.K.; Steg, L. I am vs. we are: How biospheric values and environmental identity of individuals and groups can influence pro-environmental behaviour. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 618956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, J.D.; Gilderbloom, J.I. Who’s greener? Comparing urban and suburban residents’ environmental behaviour and concern. Local Environ. 2014, 20, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Fornara, F.; Carrus, G. Predicting pro-environmental behaviors in the urban context: The direct or moderated effect of urban stress, city identity, and worldviews. Cities 2019, 88, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkle, K.A.; Monroe, M.C. Cultural cognition and climate change education in the US: Why consensus is not enough. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 633–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.M. The relationships of political ideology and party affiliation with environmental concern: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Albanesi, C.; Pietrantoni, L. The interplay among environmental attitudes, pro-environmental behavior, social identity, and pro-environmental institutional climate. A longitudinal study. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, F.; Ruane, B.; Oberman, R.; Morris, S. Geographical process or global injustice? Contrasting educational perspectives on climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurow, A.S.; Shea, M. Learning in equity-oriented scale-making projects. J. Learn. Sci. 2015, 24, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, J.; Schwichow, M.; Breitenmoser, P.; Niebert, K. The (Un)political perspective on climate change in education—A systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Herder and Herder: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, S.R. A case for climate justice education: American youth connecting to intragenerational climate injustice in Bangladesh. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. A systematic mixed studies review of civic engagement outcomes in environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, K.; Hayward, B.; Aoyagi, M.; Burningham, K.; Hasan, M.M.; Jackson, T.; Jha, V.; Kuroki, L.; Loukianov, A.; Mattar, H.; et al. Youth attitudes and participation in climate protest: An international cities comparison frontiers in political science special issue: Youth activism in environmental politics. Front. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 696105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, K.; Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K. Social class, control, and action: Socioeconomic status differences in antecedents of support for pro-environmental action. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 77, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, S.J. Gender differences in Attitudes Toward Environmental Science. Sch. Sci. Math. 2010, 107, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amriwijaya, J.; Trirahardjo, S. Analyzing the influence of social media on pro-environmental behavior via the mediation of pro-environmental knowledge and attitudes among middle school students in Bandung Regency, Indonesia. Open Access Indones. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Wei, L.; Ghani, U. The use of social networking sites and pro-environmental behaviors: A mediation and moderation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Vandenbosch, L.; Rousseau, A. A panel study of the relationships between social media interactions and adolescents’ pro-environmental cognitions and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östman, J. The influence of media use on environmental engagement: A political socialization approach. Environ. Commun. 2014, 8, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schradie, J. The Revolution That Wasn’t: How Digital Activism Favors Conservatives; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kinol, A.; Si, Y.; Kinol, J.; Stephens, J.C. Networks of climate obstruction: Discourses of denial and delay in US fossil energy, plastic, and agrichemical industries. PLoS Clim. 2025, 4, e0000370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.J. Heterogeneity in the association between environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior: A multilevel regression approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaimool, P.; Khajohnmanee, S. Roles of environmental system knowledge in promoting university students’ environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charry, K.; Parguel, B. Educating children to environmental behaviours with nudges: The effectiveness of social labelling and moderating role of age. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, P.; Doran, C.; Williams, I.D.; Kus, M. The role of intergenerational influence in waste education programmes: The THAW project. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2590–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, V.; Losito, B.; Agrusti, G.; Schulz, W. Young Citizens’ Views and Engagement in Changing Europe: IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2022 European Report; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.nl/sites/default/files/2024-02/ICCS%202022%20European%20Report.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- StataCorp LLC. Stata Statistical Software: Release 19; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.stata.com (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Afana, Y.; Brese, F.; Kowolik, H.; Cortes, D.; Schulz, W. ICCS 2022 User Guide for the International Database (Appendices); International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecina, M.L.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; López-García, L.; Díaz-Silveira, C. Eco-anxiety and trust in science in Spain: Two paths to connect climate change perceptions and general willingness for environmental behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulman, S.R.; Dobay, K.M. Environmental protection in Romania: Perceptions versus active participation. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2020, 19, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dîrțu, M.C.; Prundeanu, O. Narcissism and pro-environmental behaviors: The mediating role of self-monitoring, environmental control and attitudes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kenis, A.; Mathijs, E. Beyond individual behaviour change: The role of power, knowledge and strategy in tackling climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Denmark | Sweden | Spain | Romania | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Min | Max | Mean (SD) | Min | Max | Mean (SD) | Min | Max | Mean (SD) | Min | Max |

| Sustainable behaviours | 49.11 (9.08) | 17.67 | 77.94 | 48.48 (10.17) | 17.67 | 77.94 | 51.71 (8.46) | 17.67 | 77.94 | 49.84 (8.41) | 17.67 | 77.94 |

| Positive attitudes | 47.98 (9.02) | 16.78 | 68.88 | 50.10 (10.32) | 16.78 | 68.88 | 52.53 (10.11) | 16.78 | 68.88 | 49.04 (8.99) | 16.78 | 68.88 |

| Critical views | 45.72 (7.50) | 20.05 | 72.52 | 45.44 (18.54) | 20.05 | 72.52 | 51.97 (9.35) | 20.05 | 72.52 | 54.34 (10.45) | 20.05 | 72.52 |

| Self-efficacy | 50.15 (9.81) | 18.73 | 77.18 | 51.13 (11.68) | 18.73 | 77.18 | 51.24 (10.17) | 18.73 | 77.18 | 54.13 (9.86) | 18.73 | 77.18 |

| Digital media | 49.37 (8.86) | 41.17 | 91.03 | 50.15 (8.98) | 42.05 | 88.57 | 49.85 (9.82) | 41.17 | 91.03 | 51.59 (10.14) | 41.17 | 91.03 |

| SES | 0.02 (1.01) | −3.18 | 2.09 | 0.04 (1.01) | −3.31 | 1.90 | 0.01 (1.00) | −2.39 | 1.95 | −0.13 (0.98) | −2.29 | 2.09 |

| Civic knowledge | 555.07 (106.29) | 211.26 | 888.31 | 567.02 (110.56) | 182.95 | 893.20 | 512.30 (90.13) | 166.88 | 838.71 | 461.03 (99.31) | 171.17 | 818.21 |

| Gender | 0.51 (0.50) | 0 | 1 | 0.50 (0.50) | 0 | 1 | 0.50 (0.50) | 0 | 1 | 0.51 (0.50) | 0 | 1 |

| Denmark | Sweden | Spain | Romania | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PEA | PEB | PEA | PEB | PEA | PEB | PEA | PEB | ||||||||

| B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | |

| Critical views | 0.38 * | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.68 ** | 0.18 | 0.60 * | 0.19 | 1.18 ** | 0.18 | 0.35 * | 0.15 | 1.25 ** | 0.17 | −0.46 * | 0.17 |

| Self-efficacy | 1.70 ** | 0.15 | 1.20 ** | 0.15 | 2.00 ** | 0.18 | 1.24 ** | 0.19 | 1.52 ** | 0.18 | 0.91 ** | 0.15 | 1.97 ** | 0.17 | 1.15 ** | 0.16 |

| Digital media | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.69 ** | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 1.05 ** | 0.18 | −0.78 ** | 0.18 | 0.65 ** | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 1.04 ** | 0.16 |

| SES | 0.80 ** | 0.15 | 0.89 ** | 0.16 | 0.67 ** | 0.20 | 0.44 * | 0.20 | −0.17 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.19 | −0.21 | 0.19 |

| Civic Knowledge | 1.06 ** | 0.16 | 0.76 ** | 0.16 | 2.07 ** | 0.21 | 1.49 ** | 0.21 | 1.23 ** | 0.20 | 0.73 ** | 0.17 | 1.27 ** | 0.20 | 0.99 ** | 0.19 |

| Gender | 2.49 ** | 0.28 | 3.94 ** | 0.28 | 3.05 ** | 0.35 | 2.57 ** | 0.36 | 1.88 ** | 0.34 | 1.50 ** | 0.29 | 0.83 * | 0.33 | 1.87 ** | 0.32 |

| Constant | 46.73 ** | 0.23 | 47.20 ** | 0.23 | 48.46 ** | 0.27 | 47.15 ** | 0.28 | 51.57 ** | 0.26 | 50.97 ** | 0.23 | 48.57 ** | 0.28 | 48.94 ** | 0.28 |

| ICC | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Proportion of Variance Explained | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| Level 1 N | 3764 | 3544 | 3006 | 2983 | 3082 | 3073 | 2673 | 2654 | ||||||||

| Level 2 N | 141 | 141 | 215 | 215 | 160 | 160 | 158 | 158 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hansen, T.; Taylor, C.K.; Knowles, R.T. Digital Media and Political Engagement: Shaping Youth Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors in Four European Societies. Societies 2025, 15, 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110300

Hansen T, Taylor CK, Knowles RT. Digital Media and Political Engagement: Shaping Youth Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors in Four European Societies. Societies. 2025; 15(11):300. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110300

Chicago/Turabian StyleHansen, Tyler, Chloe K. Taylor, and Ryan T. Knowles. 2025. "Digital Media and Political Engagement: Shaping Youth Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors in Four European Societies" Societies 15, no. 11: 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110300

APA StyleHansen, T., Taylor, C. K., & Knowles, R. T. (2025). Digital Media and Political Engagement: Shaping Youth Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors in Four European Societies. Societies, 15(11), 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110300