Simple Summary

Endosymbiotic bacteria—microbes that live inside insect cells—play important roles in shaping the biology and evolution of their hosts. In this study, we examined more than 1000 insects from 14 different orders across Korea to explore how three representative endosymbionts (Wolbachia, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma) are distributed among hosts living in different environments. Single infections predominated, while co-infections were infrequent among the infected insects. Overall associations among symbiont pairs were weak, but varied among insect orders, with significant associations concentrated in Coleoptera and Hemiptera. Infection rates were broadly similar across most host orders, although Spiroplasma displayed detectable order-level differences. In addition, Wolbachia infections were more frequently detected in terrestrial than in aquatic insects. These findings indicate that endosymbiont infection patterns might be shaped by multiple factors operating at different biological scales. This study provides baseline data on endosymbiont distributions in Korean insects, offering additional context for understanding regional variation in these host–microbe associations.

Abstract

Endosymbiotic bacteria influence the ecology and evolution of insects through complex associations within host cells. To explore how these relationships vary among environments and taxa, we examined 1028 insect specimens from 14 orders across Korea for infections by three representative endosymbionts (Wolbachia, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma). Overall, 33.8% of specimens were infected, with single infections predominating and co-infections remaining relatively less common. Weak-to-modest but statistically significant associations were detected between several symbiont pairs (Rickettsia–Spiroplasma, Wolbachia–Spiroplasma, and Wolbachia–Rickettsia). Infection rates exhibited no significant variation among host orders except for Spiroplasma, and Wolbachia infections were more frequently detected in terrestrial than in aquatic insects. These results indicate that endosymbiont infection patterns might be shaped by factors operating at multiple biological scales, including host taxonomy and habitat types. As this study relied on polymerase chain reaction detection, infection frequencies should be interpreted as comparative rather than absolute measures. This survey provides baseline data that might help characterize regional patterns of endosymbiont distributions and their variation across taxonomic and ecological contexts.

1. Introduction

Organisms exist not as isolated entities but as a holobiont that comprises a host as well as its associated microbiota [1]. These microbial consortia exert broad influences on host physiology, ecology, and evolution [2,3]. Among these associations, intracellular endosymbionts represent the most intimate form of symbiosis, directly shaping host reproductive systems and patterns of genetic inheritance [4]. Representative endosymbionts include Wolbachia, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma, with Wolbachia particularly well known for manipulating host reproduction through cytoplasmic incompatibility, parthenogenesis induction, male killing, and feminization, thereby enhancing maternal transmission [5,6]. Such reproductive alterations can influence host sex ratios and have been proposed as contributors to evolutionary processes such as speciation [5].

Due to these striking reproductive effects, endosymbionts have attracted broad attention across arthropods, especially insects, where numerous surveys have been conducted. Wolbachia is estimated to infect roughly 40–60% of arthropod species [7,8] and has become the most intensively studied endosymbiont owing to its applications in biological control and suppression of vector-borne diseases [9,10]. In contrast, broad-scale comparative surveys that simultaneously screen multiple reproductive manipulators, including Rickettsia and Spiroplasma, remain relatively limited [5]. Many previous investigations have been motivated by applied objectives, concentrating on particular insect groups (e.g., pest or vector species) or on Wolbachia alone [11]. Similar tendencies appear in Korea, where endosymbiont screening has largely been confined to a few taxa such as ants, beetles, or mosquitoes, generally targeting Wolbachia or other single symbionts [12,13,14]. To date, little coordinated effort has been directed toward characterizing the distribution and co-occurrence (co-infection) patterns of multiple endosymbionts across diverse insect orders or ecological contexts in Korea.

Multiple factors are likely to shape the observed infection patterns. Most endosymbionts rely primarily on vertical (maternal) transmission via the host’s egg cytoplasm [15], although horizontal transmission across phylogenetically distant hosts has also been documented for several symbionts including Wolbachia [16,17] and Spiroplasma [18]. The establishment and maintenance of endosymbiont infections likely involve factors operating at different biological scales, ranging from ecological contexts to host taxonomic affiliations, suggesting that infection patterns observed in nature emerge from multilevel processes. Yet, most prior studies have focused on specific mechanisms or laboratory models, rarely integrating ecological or habitat-level variables into broad-scale analyses [8,19].

In this context, comparative analyses that span broad taxonomic and ecological diversity can provide important insight into the eco-evolutionary processes underlying endosymbiont transmission and establishment. The Korean insect fauna, which encompasses more than 20 orders and a wide range of habitat types, therefore presents an effective setting for exploring ecological and phylogenetic factors influencing endosymbiont infections. The presence of distinct habitat guilds within a shared geographic region offers a direct opportunity to examine how environmental conditions shape symbiont persistence and transmission dynamics.

In this study, we screened three major reproductive endosymbionts, i.e., Wolbachia, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma, across insect specimens collected throughout Korea. Infection and co-infection patterns were compared across insect orders and across habitat types (aquatic and terrestrial). Our specific goals were to (1) characterize taxon-specific infection profiles of each symbiont, (2) evaluate co-occurrence and potential associations among symbionts, and (3) examine ecological differentiation in infection prevalence between aquatic and terrestrial insects. However, instead of testing specific mechanistic hypotheses, this study aims to provide a comprehensive baseline dataset that highlights potential multilevel ecological and evolutionary drivers of endosymbiont infection patterns and establishes a foundation for future hypothesis-driven research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Extraction of Genomic DNA

Insects inhabiting Korea were collected randomly throughout the year, regardless of region. The collected specimens were initially identified to the species or genus level based on their morphological characteristics; species and family names followed the National List of Species of Korea [20]. In this study, we collected a total of 1028 individuals representing approximately 230 species (with an additional 19 taxa identified only to the genus level) across 14 insect orders. The original infection records used in this analysis were derived from the National Institute of Ecology’s 2020 annual report, which compiled survey data collected between 2017 and 2020 [21]. Species identification results and detailed sampling information are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). Specimens were classified as aquatic or terrestrial based on the primary habitat of their immature stages, regardless of the life stage at collection. After collection and morphological identification, specimens were preserved in 100% ethanol and stored at −20 °C until genomic DNA extraction. For DNA extraction, the insect exoskeleton was thoroughly crushed with a pestle. Smaller specimens were processed whole, whereas legs or other body parts were used for larger specimens. DNA was then extracted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol for the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

2.2. Host Identification

To complement this morphology-based identification at the genetic level, the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene region of approximately 650 bp was amplified from 727 individuals out of the 1028 total specimens. COI analysis served as a supplementary step to verify the initial morphological identification and to confirm species identity. For amplification, the universal primer pair LCO1490–HCO2198 [22] was primarily used, applying polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions of 95 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 48 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; followed by 72 °C for 5 min. For samples that did not amplify successfully, the dgLCO–dgHCO primer pair [23] was used under revised conditions of 95 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; followed by 72 °C for 5 min [23,24]. Sequencing yielded fragments of roughly 618 bp, which were used to construct interspecific phylogenetic trees for internal verification but were not incorporated into this paper. The obtained sequences were edited using MEGA X (version 10.2.6) [25], and molecular species identification was carried out by comparison with the GenBank database using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) during the course of the study for internal species identification.

2.3. Endosymbiont Detection and Validation

Infection status was confirmed for three endosymbionts (i.e., Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, and Rickettsia). PCR was performed using specific primers for each endosymbiont [14,26], and infection was detected based on PCR amplification results. Each PCR run included a negative control (nuclease-free water) and a positive control (a previously validated PCR-positive sample for each target endosymbiont). The PCR conditions for Wolbachia were 94 °C for 2 min; 38 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 90 s; followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. For Spiroplasma and Rickettsia, PCR conditions were 94 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; followed by 72 °C for 5 min. Since the purpose of this study was to confirm infection status, we did not perform further sequencing of PCR products. Primer information used for all PCR is provided in Table S2.

To verify detection accuracy, a subset of PCR-positive samples representing diverse insect orders was subjected to Sanger sequencing. A total of 55 sequences were obtained: 24 Wolbachia sequences amplified using ftsZ gene primers [27], which is commonly used for multi locus sequence typing (MLST) of Wolbachia; 22 Spiroplasma 16S rDNA sequences; and 9 Rickettsia 16S rDNA sequences. PCR conditions for ftsZ amplification were 94 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; followed by 72 °C for 10 min. Sequence identity was confirmed by BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 22 December 2025) analysis against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank database. All sequences showed ≥97.7% identity to their respective target genera, confirming the specificity of the detection primers. Validated sequences have been deposited in GenBank, and detailed validation results including accession numbers are provided in Table S3.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

We quantitatively examined infection patterns of three sex-manipulating endosymbiotic bacteria, i.e., Spiroplasma, Rickettsia, and Wolbachia, across 1028 insect specimens representing 14 orders. To do so, pairwise associations among symbiont infections were evaluated using a Phi coefficient (φ) to measure co-occurrence strength. Subsequently, Chi-square tests (χ2) were used to assess statistical independence among infection pairs. Phi coefficients range from −1 to +1, with values near 0 indicating independence.

Differences in infection prevalence among insect orders were tested using Kruskal–Wallis tests. For each symbiont, we included only orders with detectable infections to assess infection intensity among susceptible host lineages. When significant differences were found, we further performed Dunn’s post hoc multiple comparisons using Holm-adjusted p-values (<0.05).

Next, we evaluated differences in infection rates between ecological traits (e.g., aquatic and terrestrial) using the Mann–Whitney U test with Holm correction. Unlike the order-level analysis, this comparison included all sampled orders to evaluate ecological effects on endosymbiont establishment.

All statistical analyses were performed in Python 3.12.4 using a Jupyter Notebook (version 7.0.8) within the Anaconda environment. We used the following packages: scipy.stats (version 1.16.3 for Kruskal–Wallis, Mann–Whitney U, and Chi-square tests), scikit-posthocs (version 0.11.4 for Dunn’s post hoc comparisons), pandas (version 2.3.3) and NumPy (version 1.26.4 for data manipulation), and Matplotlib (version 3.10.6 for visualization). Code development was assisted by ChatGPT 5.0 (OpenAI).

3. Results

3.1. Infection Prevalence Across Insect Orders

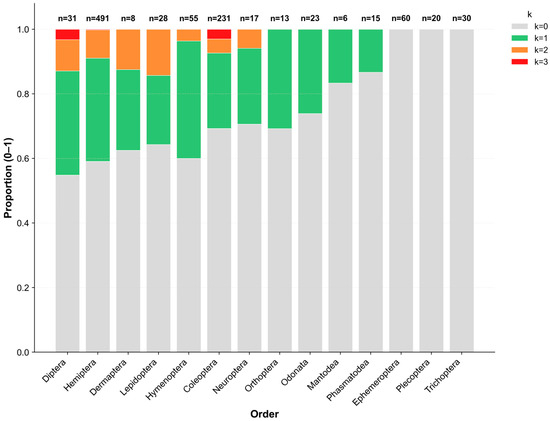

A total of 1028 insect specimens representing 14 taxonomic orders were screened for infections by three endosymbiotic bacteria, e.g., Spiroplasma, Wolbachia, and Rickettsia. Among these bacteria, 347 individuals (33.8%) carried at least one endosymbiont, whereas 681 individuals (66.2%) showed no detectable infections. Single infections predominated, while co-infections were comparatively uncommon: 70 individuals (6.8%) harbored two symbionts, and 11 individuals (1.1%) harbored three symbionts simultaneously (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportional distribution of co-infection counts (k = 0–3) across 14 insect orders. Bars represent the proportion of individuals within each order carrying 0, 1, 2, or 3 sex-manipulating endosymbiont species, respectively. Color intensity indicates the number of co-infected symbionts. The numbers above the bars show the number of individuals analyzed per order (n).

Infection prevalence varied noticeably among insect orders, although the sample sizes differed considerably (range: 6–491 individuals per order). Diptera and Hemiptera exhibited the highest infection rates (45.2% and 42.6%, respectively), with Diptera showing the largest proportion of co-infections (12.9%). Conversely, several other orders showed comparatively low infection frequencies, largely dominated by single infections. Notably, among aquatic insects, all 110 individuals of the EPT orders (i.e., Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera) were uninfected. In contrast, Odonata species displayed a moderate infection prevalence of 26.1%.

3.2. Patterns of Symbiont Co-Infection

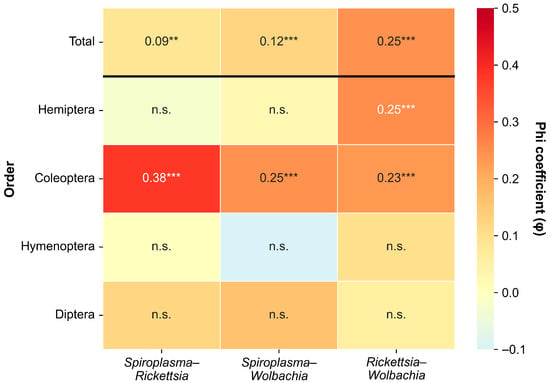

The associations among the three endosymbionts were weak but statistically significant (Figure 2, Table 1). The Rickettsia–Wolbachia combination showed the highest association (φ = 0.25, χ2 = 62.35, p < 0.001), followed by Spiroplasma–Wolbachia (φ = 0.12, χ2 = 15.37, p < 0.001) and Spiroplasma–Rickettsia (φ = 0.09, χ2 = 7.67, p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Phi coefficient (φ) matrix showing pairwise co-infection associations among three endosymbionts (Spiroplasma, Rickettsia, and Wolbachia) for total samples and by insect order. Only orders with n ≥ 30 and at least one detected infection are shown. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n.s. = not significant.

Table 1.

Pairwise associations among endosymbionts based on Chi-square tests. φ indicates the strength of association; −log10(p) indicates statistical significance.

However, at the order level, co-infection patterns varied among insect orders. In Coleoptera, the Spiroplasma–Rickettsia association was moderate (φ = 0.38, χ2 = 33.56, p < 0.001). Coleoptera showed significant positive associations across all three symbiont pairs (all p < 0.001). Hemiptera showed a different pattern, with only the Rickettsia–Wolbachia combination showing a significant association (φ = 0.25, p < 0.001); Spiroplasma-related pairs were not significant. Diptera and Hymenoptera showed no significant associations for any symbiont pair (all p > 0.05).

3.3. Prevalence of Individual Symbiont Infection Among Insect Orders

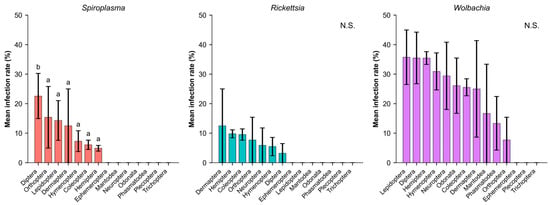

Infection prevalence showed diverse patterns across insect orders and endosymbionts (Figure 3). Since each symbiont displayed distinct host range patterns, with many orders showing no detectable infections for individual symbionts, statistical comparisons were conducted separately for each symbiont and limited to the orders in which infections were detected. Spiroplasma exhibited significant differences among the seven orders where it occurred, and Holm-corrected Dunn’s post hoc tests indicated that Diptera (22.6%) had significantly higher infection rates than most other infected orders. Within these seven orders, Diptera formed a distinct group, whereas the remaining six orders showed broadly similar infection levels (6.1–15.4%). Wolbachia was detected in 11 orders, with infection rates ranging from 7.7% to 35.7%; however, no significant differences were identified among the orders where it occurred (H = 14.63, p = 0.146).

Figure 3.

Infection prevalence of three endosymbionts across insect orders. Different letters indicate significant differences based on Holm-corrected Dunn’s post hoc tests (p < 0.05). N.S. denotes cases with no significant differences among orders. Bars represent mean ± SE. Statistical comparisons for each symbiont include only the orders in which that symbiont was detected.

3.4. Differences in Symbiont Infection Prevalence Between Aquatic and Terrestrial Insects

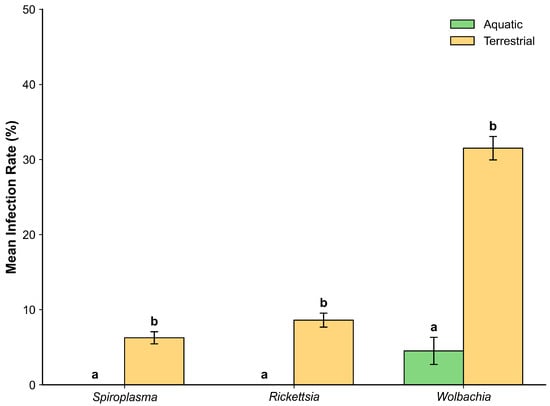

Next, to examine ecological differentiation in infection prevalence between aquatic and terrestrial insects, we compared endosymbiont infection rates between the two habitat types. Mann–Whitney U tests with Holm correction revealed significant differences for all three symbionts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of infection prevalence for three endosymbionts (e.g., Spiroplasma, Rickettsia, and Wolbachia) between aquatic and terrestrial insect groups (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 0.05).

Wolbachia showed the strongest pattern (U = 43,449.5, p < 0.001), with terrestrial insects (31.5% ± 1.6%) exhibiting markedly higher infection rates than aquatic insects (4.5 ± 1.8%). Rickettsia (U = 54,397, p < 0.01) and Spiroplasma (U = 55,793, p < 0.01) were also significantly more frequent in terrestrial insects (8.6 ± 0.9% and 6.3 ± 0.8%, respectively), while being entirely absent in aquatic insects (0%). Taken together, these results quantitatively reinforce the complete absence of endosymbionts observed in the EPT orders (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Infection rates of three endosymbionts in aquatic (green) and terrestrial (yellow) insects. Different letters indicate significant differences based on Holm-corrected Mann–Whitney U tests (p < 0.05). Bars represent mean ± SE.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the infection status of three representative endosymbionts (Wolbachia, Rickettsia, Spiroplasma) across 14 insect orders in Korea and compared infection patterns according to taxonomic groups and habitat types. Infections were mainly observed as single infections, while co-infections involving two or more endosymbionts appeared relatively limited. Pairwise analyses revealed weak but significant positive associations among Wolbachia, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma. Among host orders, only Spiroplasma exhibited significant variation in infection rates. Distinct differences in infection rates were observed between aquatic and terrestrial habitats, particularly for Wolbachia. These patterns suggest that endosymbiont infections might be shaped by factors operating at multiple biological scales.

Co-infections were relatively uncommon, with most infected insects harboring only a single symbiont. Among the observed co-infections, weak-to-modest positive associations were detected for Rickettsia–Spiroplasma, Wolbachia–Spiroplasma, and Wolbachia–Rickettsia pairs. Similar co-infection patterns among these symbionts have been reported only occasionally in arthropods, including beetles, mites, and aphids [28,29,30]. Overall, these findings suggest that detectable co-infection occurs mainly among a few symbiont pairs and remains infrequent across natural insect taxa.

Weinert et al. [7] reported significant order-level differences in infection prevalence for several endosymbionts, although their analysis did not include Spiroplasma. Conversely, Wolbachia and Rickettsia displayed no significant order-level differences across the 14 sampled insect orders in this study, whereas only Spiroplasma exhibited detectable variation. This contrast might reflect differences in geographic scope, sampling coverage, and taxonomic representation between global meta-analyses and region-focused surveys. Spiroplasma’s order-specific variation is notable given that this symbiont was not included in previous large-scale comparative studies, although strain-level analysis was beyond the scope of this study. Overall, these findings suggest that regional datasets can complement global summaries by providing additional context on variations in endosymbiont distributions across taxonomic groups and spatial scales.

Notable differences in infection patterns were observed between terrestrial and aquatic habitat types, with terrestrial insects exhibiting higher infection frequencies, particularly for Wolbachia. In our dataset, the specimen-level prevalence of Wolbachia in aquatic insects (Odonata + EPT) was 4.5%. This value is not directly comparable to the species-level incidence of approximately 52% estimated by Sazama et al. [31], as the two studies used different analytical units (specimens vs. species). Notably, none of the three endosymbionts was detected in any of the 110 EPT specimens examined, and the observed aquatic Wolbachia infections were restricted to Odonata. This EPT-specific absence is broadly consistent with the findings of Ayayee et al. [32], who similarly detected no Wolbachia in Ephemeroptera using PCR-based screening targeting wsp, although low-level signals were suggested in their microbiome-based analyses. Sazama et al. [31] likewise highlighted persistent uncertainty for EPT orders due to limited sampling and low infection rates. The discrepancy between our low aquatic infection rate and higher values reported in other studies likely reflects differences in taxonomic coverage: our aquatic sampling included only Odonata and EPT, whereas studies reporting higher prevalence often included aquatic Diptera, Coleoptera, or Hemiptera. The consistent absence or minimal detection of endosymbionts in EPT across multiple studies, now reinforced by our examination of 110 EPT specimens, suggests that these orders might face constraints that limit symbiont establishment. Collectively, these findings underscore that habitat type and host order jointly influence endosymbiont distribution patterns.

Several methodological limitations should be noted. Sampling was uneven across insect orders, which might have reduced statistical power for detecting low-prevalence infections or subtle taxonomic differences. Standard PCR-based screening can also underestimate low-titer infections or symbionts with divergent sequences, a limitation noted in previous studies of heritable bacterial symbionts [5,30]. DNA extraction from legs or other body parts for larger specimens may have reduced detection sensitivity, as some endosymbionts exhibit tissue-specific distributions. While leg-derived DNA has been shown to be sufficient for detecting Wolbachia [33], detection efficiency for other endosymbionts such as Spiroplasma and Rickettsia may be more limited. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of this survey precluded temporal or seasonal inference regarding infection dynamics. Consequently, the patterns presented in this study should be viewed as comparative indicators rather than precise estimates of true infection prevalence.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that endosymbiont infection patterns in Korean insects might be shaped by multiple interacting factors, as suggested by the relative infrequency of co-infections among symbionts, the presence of order-level variation only in Spiroplasma, and the notable differences associated with habitat types. These multilevel patterns may suggest that no single determinant alone can fully explain the distribution of infections across taxa and environments and that both taxonomic and ecological contexts merit consideration when interpreting broad-scale symbiont prevalence structures.

Despite methodological limitations discussed above, this study provides several important contributions. First, it increased the relatively small number of multi-order regional surveys in East Asia that simultaneously screened three major endosymbionts, thereby expanding geographic representation in global endosymbiont datasets. Second, it included aquatic insect orders (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera) that have been historically underrepresented in prevalence surveys, offering new baseline data for groups noted as difficult to sample in previous large-scale work [31]. Third, it incorporated Spiroplasma into a multi-symbiont framework, adding comparative data that were absent from earlier global summaries such as Weinert et al. [7]. Together, these dataset-level contributions have broadened the empirical basis for understanding regional variation in endosymbiont communities and provided opportunities for generating hypotheses about the relative roles of ecological and taxonomic factors in shaping infection patterns. Future research that integrates quantitative assays, strain-level characterization, and expanded temporal and spatial sampling across Asian ecosystems might help further clarify the processes underlying these multilevel patterns.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects17010071/s1. Table S1: Sample information for all 1028 insect specimens, including taxonomic identification, collection data, habitat classification, life stage, and infection status. Table S2: Primer sets used for PCR amplification of three endosymbionts (Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, and Rickettsia) and host COI gene, including target loci, primer sequences, expected amplicon sizes, and references. Table S3: Sequence validation results for 55 PCR-positive samples, including BLAST identity scores, query coverage, and GenBank accession numbers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P.; Formal Analysis and Visualization, J.-Y.K.; Writing—Original Draft and Review, S.P., J.-Y.K. and G.J.; Investigation (molecular experiments), I.J.A. and K.K.; Equal Contribution, I.J.A. and K.K.; Investigation, S.-h.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute of Ecology (NIE) research program, NIE-B-2025-38 and NIE-B-2026-18.

Data Availability Statement

The species identification results and detailed sampling information supporting the reported results are available in the Supplementary Materials, which are publicly accessible at [http://doi.or.kr/10.22756/GEO.20250000000992] (accessed on 26 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used several generative AI tools, including ChatGPT (OpenAI GPT-5), Claude (Anthropic Claude Sonnet 4.5), and Perplexity AI (Perplexity Labs, version 2025) to assist with language editing and improve clarity, coherence, and readability. All AI tools were used under the direct supervision of the authors. AI tools were not used to generate, analyze, or interpret data, nor to contribute to any scientific reasoning or conclusions. They served solely as linguistic and workflow support utilities. All conceptual development, data analyses, and scientific interpretations were conceived, verified, and finalized by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| COI | Cytochrome oxidase I |

| EPT | Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| MLST | multilocus sequence typing |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

References

- Zilber-Rosenberg, I.; Rosenberg, E. Role of Microorganisms in the Evolution of Animals and Plants: The Hologenome Theory of Evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, N.A.; McCutcheon, J.P.; Nakabachi, A. Genomics and Evolution of Heritable Bacterial Symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFall-Ngai, M.; Hadfield, M.G.; Bosch, T.C.G.; Carey, H.V.; Domazet-Lošo, T.; Douglas, A.E.; Dubilier, N.; Eberl, G.; Fukami, T.; Gilbert, S.F.; et al. Animals in a Bacterial World, a New Imperative for the Life Sciences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3229–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.M.; Degnan, P.H.; Burke, G.R.; Moran, N.A. Facultative Symbionts in Aphids and the Horizontal Transfer of Ecologically Important Traits. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duron, O.; Bouchon, D.; Boutin, S.; Bellamy, L.; Zhou, L.; Engelstädter, J.; Hurst, G.D. The Diversity of Reproductive Parasites among Arthropods: Wolbachia do Not Walk Alone. BMC Biol. 2008, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werren, J.H.; Baldo, L.; Clark, M.E. Wolbachia: Master Manipulators of Invertebrate Biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, L.A.; Araujo-Jnr, E.V.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Welch, J.J. The Incidence of Bacterial Endosymbionts in Terrestrial Arthropods. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20150249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordenstein, S.R.; Bordenstein, S.R. Eukaryotic Association Module in Phage WO Genomes from Wolbachia. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.A.; Montgomery, B.L.; Popovici, J.; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; Johnson, P.H.; Muzzi, F.; Greenfield, M.; Durkan, M.; Leong, Y.S.; Dong, Y. Successful Establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes Populations to Suppress Dengue Transmission. Nature 2011, 476, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourtzis, K.; Dobson, S.L.; Xi, Z.; Rasgon, J.L.; Calvitti, M.; Moreira, L.A.; Bossin, H.C.; Moretti, R.; Baton, L.A.; Hughes, G.L. Harnessing Mosquito–Wolbachia Symbiosis for Vector and Disease Control. Acta Trop. 2014, 132, S150–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Funaro, C.F.; Giraldo, Y.M.; Goldman-Huertas, B.; Suh, D.; Kronauer, D.J.; Moreau, C.S.; Pierce, N.E. A Veritable Menagerie of Heritable Bacteria from Ants, Butterflies, and beyond: Broad Molecular Surveys and a Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintola, A.A.; Kim, G.; Adeniyi, K.A.; Hwang, U.W. Prevalence of Wolbachia Endosymbiont in Culex molestus Mosquitoes from South Korea. Entomol. Res. 2024, 54, e12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Noh, P.; Kang, J.-Y. Endosymbionts and Phage WO Infections in Korean Ant Species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proc. Natl. Inst. Ecol. Repub. Korea 2020, 1, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.; Han, T.; Park, H.; Park, S.; Noh, P. Distribution and Recombination of Wolbachia Endosymbionts in Korean Coleopteran Insects. J. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 43, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaenike, J. Population Genetics of Beneficial Heritable Symbionts. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavre, F.; Fleury, F.; Lepetit, D.; Fouillet, P.; Boulétreau, M. Phylogenetic Evidence for Horizontal Transmission of Wolbachia in Host-Parasitoid Associations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raychoudhury, R.; Baldo, L.; Oliveira, D.C.; Werren, J.H. Modes of Acquisition of Wolbachia: Horizontal Transfer, Hybrid Introgression, and Codivergence in the Nasonia Species Complex. Evolution 2009, 63, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regassa, L.B.; Gasparich, G.E. Spiroplasmas: Evolutionary Relationships and Biodiversity. Front. Biosci. 2006, 11, 2983–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-Y.; Kwon, Y.-S.; Jeong, G.; An, I.; Park, S. Characteristics of Microbial Communities of Pachygrontha antennata (Hemiptera: Pachygronthidae) in Relation to Habitat Variables. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR). National List of Species of Korea; NIBR: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2024. Available online: https://species.nibr.go.kr (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, S.S.; Jeong, S.E. Characteristics of Microbial Communities of Insects (Hemiptera) in Relation to Habitat Variables; National Institute of Ecology: Seocheon-gun, Republic of Korea, 2020; ISBN 979-11-912068-8-3. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA Primers for Amplification of Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I from Diverse Metazoan Invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C.P. Molecular Systematics of Cowries (Gastropoda: Cypraeidae) and Diversification Patterns in the Tropics. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2003, 79, 401–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leray, M.; Yang, J.Y.; Meyer, C.P.; Mills, S.C.; Agudelo, N.; Ranwez, V.; Boehm, J.T.; Machida, R.J. A New Versatile Primer Set Targeting a Short Fragment of the Mitochondrial COI Region for Metabarcoding Metazoan Diversity: Application for Characterizing Coral Reef Fish Gut Contents. Front. Zool. 2013, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, D.; Anbutsu, H.; Watada, M.; Hosokawa, T.; Shimada, M.; Fukatsu, T. Prevalence of a Non-Male-Killing Spiroplasma in Natural Populations of Drosophila hydei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 6667–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, L.; Dunning Hotopp, J.C.; Jolley, K.A.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Biber, S.A.; Choudhury, R.R.; Hayashi, C.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Tettelin, H.; Werren, J.H. Multilocus Sequence Typing System for the Endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7098–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolasa, M.; Kubisz, D.; Gutowski, J.M.; Ścibior, R.; Mazur, M.A.; Holecova, M.; Kajtoch, Ł. Infection by Endosymbiotic. Folia Biol. 2018, 66, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-K.; Chen, Y.-T.; Yang, K.; Qiao, G.-X.; Hong, X.-Y. Screening of Spider Mites (Acari: Tetranychidae) for Reproductive Endosymbionts Reveals Links between Co-Infection and Evolutionary History. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanov, D.A.; Zakharov, I.A.; Shaikevich, E.V. Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, and Rickettsia Symbiotic Bacteria in Aphids (Aphidoidea). Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2020, 24, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazama, E.J.; Bosch, M.J.; Shouldis, C.S.; Ouellette, S.P.; Wesner, J.S. Incidence of Wolbachia in Aquatic Insects. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 1165–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayayee, P.A.; Wesner, J.S.; Ouellette, S.P. Geography, Taxonomy, and Ecological Guild: Factors Impacting Freshwater Macroinvertebrate Gut Microbiomes. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Bertrand, C.; Crosby, K.; Eveleigh, E.S.; Fernandez-Triana, J.; Fisher, B.L.; Gibbs, J.; Hajibabaei, M.; Hallwachs, W.; Hind, K.; et al. Wolbachia and DNA Barcoding Insects: Patterns, Potential, and Problems. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.