Diversity of Aedes Mosquito Breeding Sites and the Epidemic Risk of Arboviral Diseases in Benin

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

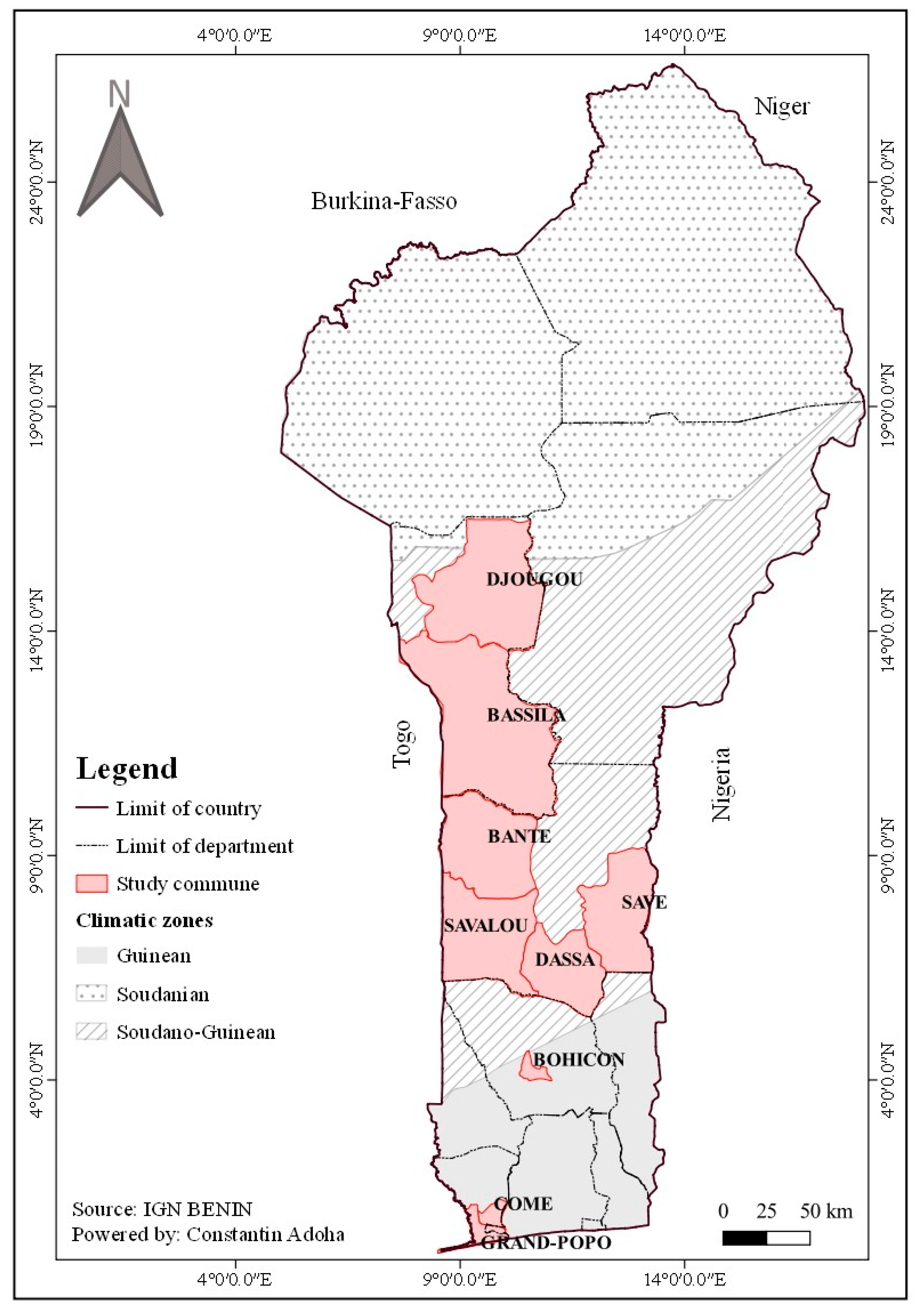

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Contact and Consent of Heads of Households and Villages

2.3. Sampling of Immatures of Mosquito

2.4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

2.4.1. Assessment of the Epidemic Risk of Occurrence of Arboviral Diseases

- Container Index (CI): percentage of water-holding containers infested with Aedes larvae or pupae.

- Breteau Index (BI): number of positive containers per 100 houses inspected.

- House Index (HI): percentage of houses infested with Aedes larvae or pupae.

2.4.2. Diversity of Mosquito Breeding Sites

- Container index (CI) = number of breeding sites infested with Aedes larvae and pupae × 100∕number of breeding sites inspected. It is interpreted as follows:

- CI < 3, low epidemic risk;

- 3 ≤ CI ≤ 20, moderate epidemic risk;

- CI > 20, high epidemic risk.

- Breteau index (BI) = number of positive breeding sites found in 100 inspected houses. This index is interpreted as follows:

- BI < 5, low epidemic risk;

- 5 ≤ BI ≤50, moderate epidemic risk;

- If BI > 50, high epidemic risk.

- House index (HI) = number of houses with positive breeding sites for Aedes larvae × 100∕number of houses inspected. The following ranges are used to interpret this index:

- HI < 4, low epidemic risk;

- If 4 ≤ HI ≤ 35, moderate epidemic risk;

- If HI > 35, high epidemic risk.

3. Results

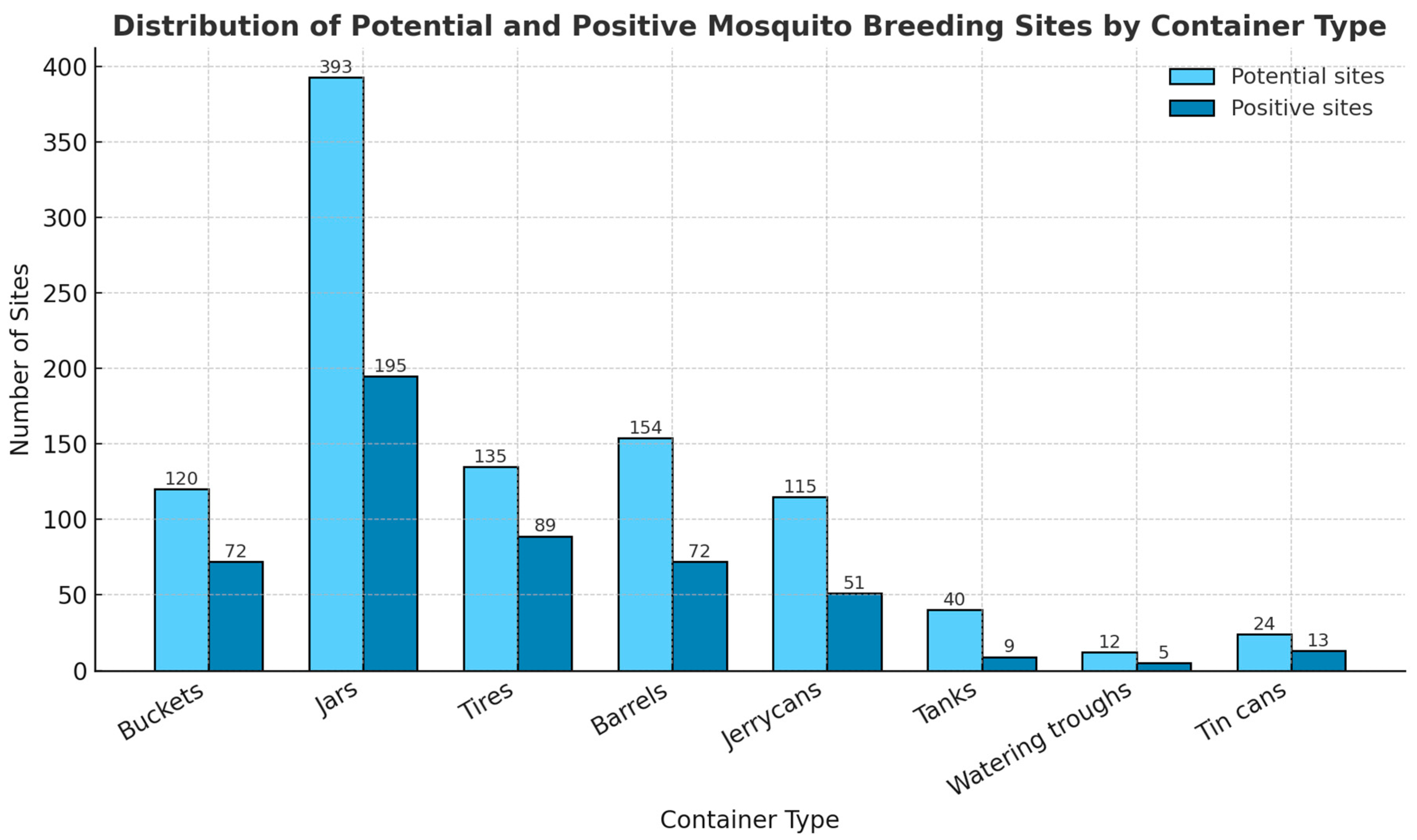

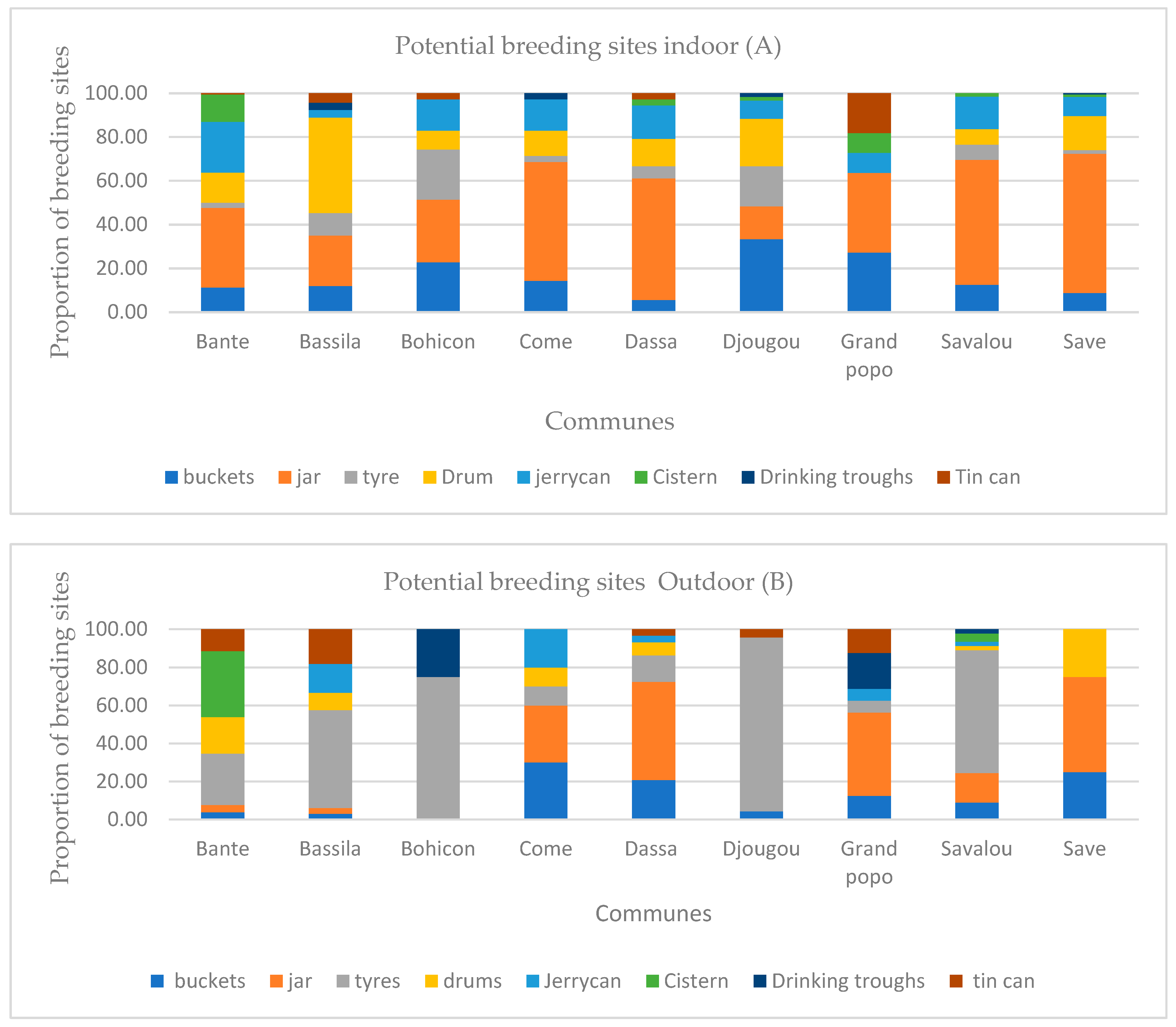

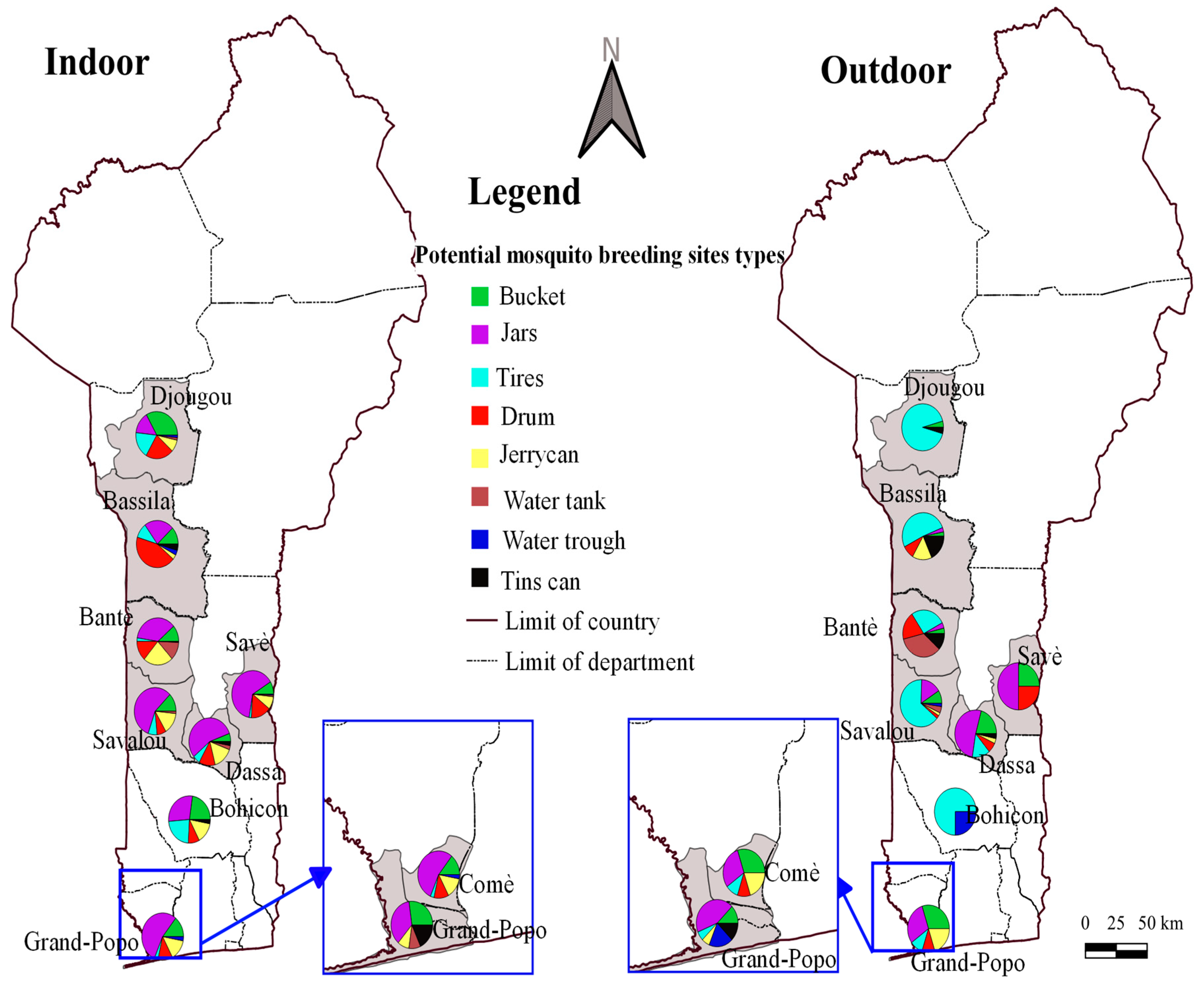

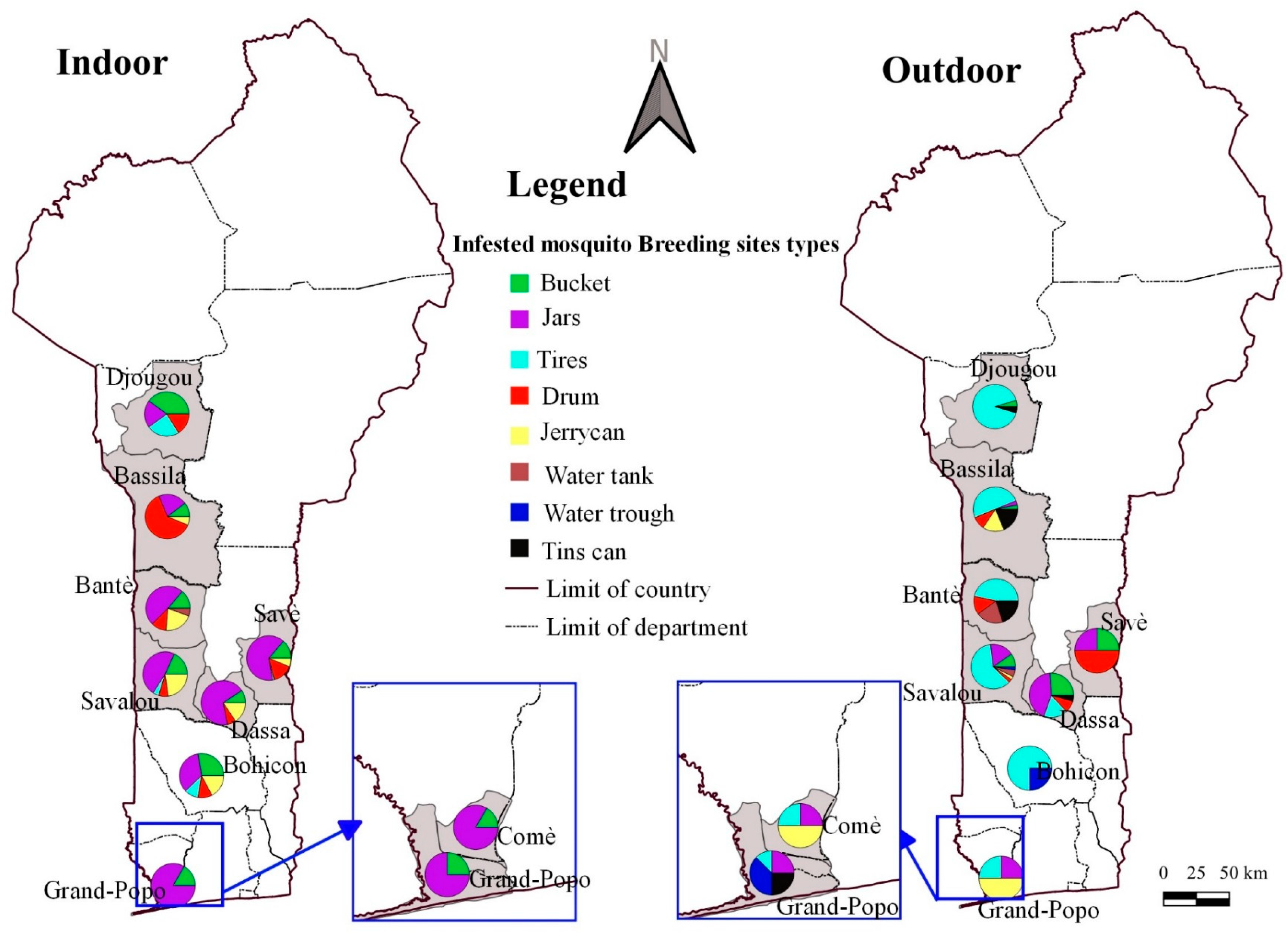

3.1. Main Mosquito Breeding Sites

3.2. Mosquito Species Composition

3.3. Diversity and Frequency of Breeding Sites

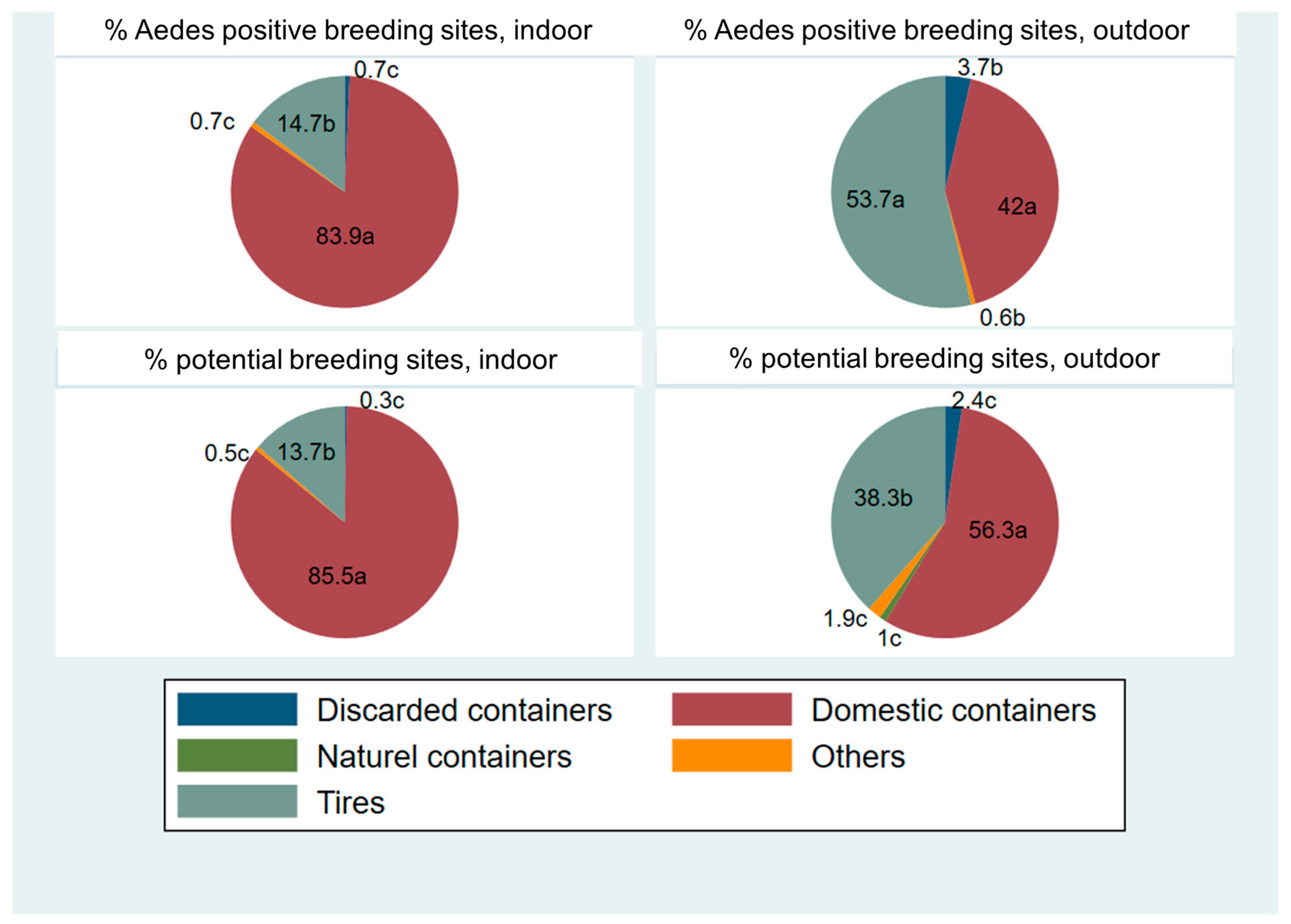

3.4. Classification of Potential and Infested Mosquito Breeding Sites

3.5. Assessment of the Epidemic Risk of Arboviral Disease Occurrence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ae | Aedes |

| An. | Anopheles |

| Cx | Culex |

| CREC | Centre de Recherche Entomologique de Cotonou |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

References

- Singh, N.; Shukla, M.; Chand, G.; Barde, P.V.; Singh, M.P. Vector-borne diseases in central India, with reference to malaria, filaria, dengue and chikungunya. WHO South-East Asia J. Public Health 2014, 3, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hery, L.; Boullis, A.; Vega-Rúa, A. Les propriétés biotiques et abiotiques des gîtes larvaires d’Aedes aegypti et leur influence sur les traits de vie des adultes (synthèse bibliographique). Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2021, 25, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. Maladies à Transmission Vectorielle. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- OMS. Dengue—Situation Mondiale. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/fr/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON498 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- OMS. Alerte Vectorielle: Invasion et Propagation d’Anopheles Stephensi en Afrique et à Sri Lanka. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/fr/publications-detail/9789240067714 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Padane, A.; Tegally, H.; Ramphal, Y.; Seyni, N.; Sarr, M.; Diop, M.M.; Diedhiou, C.K.; Mboup, A.; Diouf, N.D.; Souaré, A.; et al. An emerging clade of Chikungunya West African genotype discovered in real-time during 2023 outbreak in Senegal. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangoura, S.T.; Keita, A.; Diaby, M.; Sidibé, S.; Le-Marcis, F.; Camara, S.C.; Touré, A. Les épidémies d’arbovirus comme impératif de santé mondiale, Afrique, 2023. Mal. Infect. Émerg. 2025, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, O.; de Lourdes Monteiro, M.; Vrancken, B.; Prot, M.; Lequime, S.; Diarra, M.; Ndiaye, O.; Valdez, T.; Tavarez, S.; Ramos, J.; et al. Genomic Epidemiology of 2015–2016 Zika Virus Outbreak in Cape Verde. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercy, K.; Youm, E.; Aliddeki, D.; Faria, N.R.; Kebede, Y.; Ndembi, N. The looming threat of dengue fever: The Africa context. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allanonto, V.; Yanogo, P.; Sawadogo, B.; Akpo, Y.; Noudeke, N.D.; Saka, B.; Sourakatou, S. Investigation des cas de Dengue dans les Départements de l’Atlantique, du Littoral et de l’Ouémé, Bénin, Avril-Juillet 2019. J. Interv. Epidemiol. Public Health 2021, 4, 5. Available online: https://www.afenet-journal.net/content/series/4/3/5/full (accessed on 6 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Tchibozo, C.; Hounkanrin, G.; Yadouleton, A.; Bialonski, A.; Agboli, E.; Lühken, R.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Hanna, J. Surveillance of arthropod-borne viruses in Benin, West Africa 2020–2021: Detection of dengue virus 3 in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Mil. Med. Res. 2022, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padonou, G.G.; Konkon, A.K.; Zoungbédji, D.M.; Salako, A.S.; Sovi, A.; Oussou, O.; Sidick, A.; Ahouandjinou, J.; Towakinou, L.; Ossé, R.; et al. Detection of DENV-1, DENV-3, and DENV-4 Serotypes in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, and Epidemic Risk in the Departments of Oueme and Plateau, South-Eastern Benin. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2024, 24, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, T.T.; Schallig, H.D.F.H.; Kurmane, Z.M.; Danquah, J.B. Increasing prevalence of malaria and acute dengue virus coinfection in Africa: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of cross-sectional studies. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, S.; Ho, S.H.; Seah, A.; Ong, J.; Dickens, B.S.; Tan, K.W.; Koo, J.R.; Cook, A.R.; Tan, K.B.; Sim, S.; et al. Economic impact of dengue in Singapore from 2010 to 2020 and the cost-effectiveness of Wolbachia interventions. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2021, 1, e0000024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, D.; Laurince Yapo, M.; Koné, M.; Gertrude Akpess, E.; Valery Ozoukou, E.P.; Tuo, Y. Caractérisation des Gîtes Larvaires de Moustiques en Saison des Pluies à L’intérieur et Autour du Périmètre Universitaire de KORHOGO (Côte d’Ivoire). Entomol. Faun.—Faun. Entomol. 2023, 76, 111–125. Available online: https://popups.uliege.be/2030-6318/index.php?id=6177 (accessed on 13 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Paz-Bailey, G.; Adams, L.E.; Deen, J.; Anderson, K.B.; Katzelnick, L.C. Dengue. Lancet 2024, 403, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, H.L.C.; Marshall, D.J.; Comerford, B.; McNulty, B.P.; Diaz, A.M.; Jones, M.J.; Mejia, A.J.; Bjornstad, O.N.; McGraw, E.A. Larval crowding enhances dengue virus loads in Aedes aegypti, a relationship that might increase transmission in urban environments. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, E. Global expansion of Aedes mosquitoes and their role in the transboundary spread of emerging arboviral diseases: A comprehensive review. IJID One Health 2025, 6, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessou-Djossou, D.; Djègbè, I.; Ahadji-Dabla, K.M.; Nonfodji, O.M.; Tchigossou, G.; Djouaka, R.; Cornelie, S.; Djogbenou, L.; Akogbeto, M.; Chandre, F. Diversity of larval habitats of Anopheles mosquitoes in urban areas of Benin and influence of their physicochemical and bacteriological characteristics on larval density. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhissen, S.; Habbachi, W.; Rebbas, K.; Masna, F. Entomological and typological studies of larval breeding sites of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Bousaâda area (Algeria). Bull. Soc. Roy. Sci. Liège 2018, 87, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djogbénou, L. Vector control methods against malaria and vector resistance to insecticides in Africa. Med. Trop. 2009, 69, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gnanglè, C.P.; Kakaï, R.G.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Vodounnon, S.; Yabi, J.A.; Sokpon, N. Tendances climatiques passées, modélisation, perceptions et adaptations locales au Benin. Climatologie 2011, 8, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/fr/c/LEX-FAOC214301 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Imam, H.; Zarnigar; Sofi, G.; Seikh, A. The basic rules and methods of mosquito rearing (Aedes aegypti). Trop. Parasitol. 2014, 4, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coluzzi, M. Maintenance of laboratory colonies of Anopheles mosquitos. Bull. World Health Organ. 1964, 31, 441–443. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, F.W. Mosquitoes of the Ethiopian Region. III.-Culicine Adults and Pupae; British Museum (Natural History): London, UK, 1941; viii+499pp. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.M. The subgenus Stegomyia of Aedes in the Afrotropical Region with keys to the species (Diptera: Culicidae). Zootaxa 2004, 700, 1–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar. J. 2020, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control: New Edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK143157/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- WHO. Global Vector Control Response 2017–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/218621 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Weetman, D.; Kamgang, B.; Badolo, A.; Moyes, C.L.; Shearer, F.M.; Coulibaly, M.; Pinto, J.; Lambrechts, L.; McCall, P.J.; Ferguson, H.M.; et al. Aedes mosquitoes and Aedes-borne arboviruses in Africa: Current and future threats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Rapid Field Entomological Assessment During Yellow Fever Outbreaks in Africa; Yactayo, S., Perea, W., Millot, V., Eds.; Biotext Pty Ltd.: Bruce, Australia, 2014; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, A.B.B.; Wilk-da-Silva, R.; Marrelli, M.T. Microclimatic aspects of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus breeding sites. Insects 2020, 11, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamgang, B.; Ngoagouni, C.; Manirakiza, A.; Nakouné, E.; Paupy, C.; Kazanji, M. Temporal patterns of abundance of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) and mitochondrial DNA analysis of Ae. albopictus in the Central African Republic. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konan, Y.L.; Diallo, M.; Dia, I.; Diarrassouba, S. Entomological indices of Aedes aegypti in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Acta Trop. 2013, 127, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenille, D.; Toto, J.C. Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse), a potential new Dengue vector in southern Cameroon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001, 7, 1066–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ngugi, H.N.; Mutuku, F.M.; Ndenga, B.A.; Musunzaji, P.S.; Mbakaya, J.O.; Aswani, P.; Kitron, U. Characterization and productivity profiles of Aedes aegypti (L.) breeding habitats across rural and urban landscapes in western Kenya. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, D. Review: Artificial container-breeding mosquitoes and cemeteries: A perfect match. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2007, 12, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, A.; Owusu-Asenso, C.M.; Haizel, C.; Mensah, S.K.E.; Sraku, I.K.; Mohammed, A.R.; Akuamoah-Boateng, Y.; Forson, A.O.; Afrane, Y.A. The Role of Car Tyres in the Ecology of Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes in Ghana. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2024, 5, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferede, G.; Tiruneh, M.; Abate, E.; Kassa, W.J.; Wondimeneh, Y.; Damtie, D.; Tessema, B. Distribution and larval breeding habitats of Aedes mosquito species in residential areas of northwest Ethiopia. Epidemiol. Health 2018, 40, e2018015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, N.; Tyagi, B.K.; Samuel, M.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Manavalan, R.; Tewari, S.C.; Kroeger, A. Community-based control of Aedes aegypti by adoption of eco-health methods in Chennai City, India. Pathog. Glob. Health 2012, 106, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, L.R.; Donegan, S.; McCall, P.J. Is dengue vector control deficient in effectiveness or evidence?: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidance for Integrated Vector Management; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleke, M.A.; Adebimpe, W.O.; Hassan, A.O.; Sam-Wobo, S.O. Habitats larvaires des moustiques dans la métropole d’Osogbo, au sud-ouest du Nigéria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appawu, M.; Dadzie, S.; Baffoe-Wilmot, A.; Wilson, M.D. Surveillance of Aedes mosquitoes and dengue vectors in some selected communities in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. Ghana Med. J. 2006, 40, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Egid, B.R.; Coulibaly, M.; Dadzie, S.K.; Kamgang, B.; McCall, P.J.; Sedda, L.; Toe, K.H.; Wilson, A.L. Review of the ecology and behaviour of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Western Africa and implications for vector control. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2022, 2, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control, 2012–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Kamal, S.; Patnaik, S.K.; Sharma, R.C. Breeding habitats and larval indices of Aedes aegypti (L.) in residential areas of Rajahmundry town Andhra Pradesh. J. Commun. Dis. 2002, 34, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Oduola, A.O.; Obembe, A.; Adelaja, O.J.; Ande, A.T.; Awolola, T.S. Surveillance of Aedes aegypti in relation to dengue transmission in Nigeria. J. Vector Ecol. 2016, 41, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamgang, B.; Happi, J.Y.; Boisier, P.; Njiokou, F.; Hervé, J.P.; Simard, F.; Paupy, C. Geographic and ecological distribution of the dengue and chikungunya virus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in three major Cameroonian towns. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2010, 24, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categories of Breeding Sites | Breeding Sites | N of Emerged Mosquitoes | Ae. Aegypti (%) | Ae. albopictus (%) | Ae. vittatus (%) | An. gambiae (%) | Cx. nebulosus (%) | Cx. tigripes (%) | Cx. quinquefasciatus (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic containers | Drinking troughs | 2 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| jerrycans | 287 | 83.97 a | 1.05 b | 2.79 b | 0.70 b | 1.05 b | 10.45 c | <0.0001 | ||

| Kettle | 11 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Canaries | 57 | 91.23 a | - | - | - | - | - | 8.77 b | <0.0001 | |

| Jar | 436 | 71.33 a | - | 0.69 b | 3.21 b | 0.46 b | 1.83 b | 22.48 c | <0.0001 | |

| Bucket | 342 | 86.55 a | 0.58 b | - | 0.58 b | - | - | 12.28 c | <0.0001 | |

| Cistern | 126 | 72.22 a | - | - | 2.38 b | - | - | 25.4 c | <0.0001 | |

| Drum | 162 | 91.36 a | - | - | 1.85 b | - | - | 6.79 c | <0.0001 | |

| Discarded container | Tin can | 128 | 50 a | - | - | 0.78 b | - | 0.78 b | 48.44 a | <0.0001 |

| Tyres | Tyres | 394 | 41.11 a | 0.25 b | 2.79 b | 1.02 b | 1.02 b | 0.5 b | 53.3 c | <0.0001 |

| Other breeding sites | Mortar | 43 | 62.79 a | - | - | - | 9.30 b | - | 27.91 c | <0.0001 |

| Position | Discarded Containers | Domestic Containers | Naturel Containers | Others | Tyres | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| potential breeding sites | Indoor | 0.32 c | 85.46 a | 0 | 0.53 c | 13.7 b | <0.0001 |

| Outdoor | 2.43 c | 56.31 a | 0.97 c | 1.94 c | 38.35 b | <0.0001 | |

| Aedes positive breeding sites | Indoor | 0.72 c | 83.86 a | 0 | 0.72 c | 14.7 b | <0.0001 |

| Outdoor | 3.7 b | 41.98 a | 0 | 0.62 b | 53.7 a | <0.0001 |

| Commune | N Breeding Sites | Positive Breeding Sites | N Houses | Positive Houses | House Index 95% CI | Risk Level | Container Index 95% CI | Risk Level | Breteau Index 95% CI | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bante | 181 | 87 | 37 | 20 | 54.05 [38.4–69] | High | 48.06 [40.9–55.3] | High | 235.1 [185.7–284.5] | High |

| Bassila | 122 | 80 | 35 | 19 | 54.28 [38.2–69.5] | High | 65.57 [56.8–73.4] | High | 228.6 [178.5–278.7] | High |

| Bohicon | 39 | 33 | 12 | 8 | 66.66 [39.1–86.2] | High | 84.61 [70.3–92.8] | High | 275 [181.2–368.8] | High |

| Comé | 46 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 90 [59.6–98.2] | High | 47.82 [34.1–61.9] | High | 220 [128.1–311.9] | High |

| Dassa-Zounmé | 60 | 55 | 24 | 10 | 41.66 [24.5–61.2] | High | 91.66 [81.9–96.4] | High | 229.2 [168.6–289.7] | High |

| Djougou | 60 | 47 | 37 | 10 | 27.02 [15.4–43] | Medium | 78.33 [66.4–86.9] | High | 127 [90.7–163.3] | High |

| Grand Popo | 29 | 12 | 20 | 7 | 35 [18.1–56.7] | Medium | 41.37 [25.5–59.3] | High | 60 [26.1–93.9] | High |

| Savalou | 142 | 85 | 38 | 19 | 50 [34.8–65.2] | High | 59.85 [51.6–67.6] | High | 223.7 [176.1–271.2] | High |

| Savè | 192 | 86 | 53 | 24 | 45.28 [32.7–58.5] | High | 44.79 [37.9–51.9] | High | 162.3 [128–196.6] | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Padonou, G.G.; Hoyochi, I.; Sovi, A.; Konkon, A.K.; Zoungbédji, D.M.; Salako, A.S.; Adoha, C.J.; Fassinou, A.; Koukpo, C.Z.; Chitou, S.; et al. Diversity of Aedes Mosquito Breeding Sites and the Epidemic Risk of Arboviral Diseases in Benin. Insects 2025, 16, 1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121215

Padonou GG, Hoyochi I, Sovi A, Konkon AK, Zoungbédji DM, Salako AS, Adoha CJ, Fassinou A, Koukpo CZ, Chitou S, et al. Diversity of Aedes Mosquito Breeding Sites and the Epidemic Risk of Arboviral Diseases in Benin. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121215

Chicago/Turabian StylePadonou, Germain Gil, Isidore Hoyochi, Arthur Sovi, Alphonse Keller Konkon, David Mahouton Zoungbédji, Albert Sourou Salako, Constantin Jésukèdè Adoha, Arsène Fassinou, Come Z. Koukpo, Saïd Chitou, and et al. 2025. "Diversity of Aedes Mosquito Breeding Sites and the Epidemic Risk of Arboviral Diseases in Benin" Insects 16, no. 12: 1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121215

APA StylePadonou, G. G., Hoyochi, I., Sovi, A., Konkon, A. K., Zoungbédji, D. M., Salako, A. S., Adoha, C. J., Fassinou, A., Koukpo, C. Z., Chitou, S., Nwangwu, U., Yadouleton, A., Baba-Moussa, L., & Akogbéto, M. C. (2025). Diversity of Aedes Mosquito Breeding Sites and the Epidemic Risk of Arboviral Diseases in Benin. Insects, 16(12), 1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121215