1. Introduction

The interaction between a fluid and a bounding solid surface is of fundamental importance in fluid dynamics, governing a wide range of natural processes and technological applications [

1,

2]. Traditionally, the no-slip boundary condition, where the tangential component of the fluid velocity at the surface and corresponding component of wall velocity are equal, has served as a cornerstone in both theoretical and computational models of viscous flows [

3,

4]. While this assumption has been remarkably successful in describing macroscopic phenomena, growing evidence from micro and nanoscale studies suggests that it may not always hold [

3,

5]. In particular, the boundary condition may be different under conditions of strong confinement or high shear rates, or in the presence of chemically or topographically heterogeneous surfaces. In such contexts, deviations from the no-slip condition can emerge in the form of slip at the fluid–solid interface, whereby the fluid exhibits a finite tangential velocity relative to the wall. Conversely, stick conditions persist when molecular interactions enforce strong adhesion, effectively restoring the classical no-slip behavior. The transition between stick and slip regimes, as well as the parameters influencing this behavior, such as fluid properties, surface chemistry, roughness, and wettability remains a subject of intense investigation in both experimental and theoretical studies [

6,

7].

One of the most significant consequences of fluid slip is the reduction in interfacial friction. When slip occurs, the effective shear stress at the wall is diminished, substantially lowering energy dissipation in fluid transport systems [

8]. This effect is particularly relevant in engineering applications where efficiency and energy savings are critical. By controlling or enhancing slip through various mechanisms, it becomes possible to minimize viscous losses and improve performance in systems operating at both macro and nanoscales [

8,

9].

Many reported studies of the behavior of fluids confined between rigid solid walls are based on computer simulations [

4,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Molecular dynamics (MD) is typically used to describe the phenomena that occur at the nanoscale, where classical hydrodynamic equations cannot characterize the system behavior. As an illustrative example we can refer to classical studies [

2,

3,

7], where ordering and flow of the Lennard–Jones (LJ) fluid near solid walls were described with MD simulations. Other notable examples of the characterization of fluid–wall interactions, based on molecular dynamics, are the description of solidification of LJ fluid near the wall [

14], the study of the commensurability effects of nanoconfined water [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], and many others [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Even though interatomic distances are an important parameter in MD simulations of tribological systems, most of the reported studies focus on particular effects, emerging in certain lubricants and solids, without quantifying the general effect of commensurability at arbitrary solid–fluid interfaces. This is the research question that the present work is primarily aimed at.

Here we report the results of MD simulations of friction between an LJ fluid and solid walls at different conditions. We aim to study how the friction coefficient in such systems depends on the ratio of interatomic distances between fluid particles to those between wall atoms. We expect friction reduction at incommensurable interatomic distances, when the mentioned relationship is close to the golden ratio. To verify this assumption, we performed a set of numerical experiments where an LJ fluid is confined between two parallel walls with a face-centered cubic (fcc) crystal structure and different lattice parameters. Such an analysis may be useful in understanding how the atomic structure and relative interatomic distances in solid walls affect the slip conditions and, correspondingly, the friction in the system.

2. Materials and Methods

We consider a nanotribological system that consists of a Lennard–Jones fluid confined between two solid walls. The wall particles are arranged according to the

fcc lattice while each wall has a thickness of three atomic layers and an atomically flat surface. The fluid phase consists of 17,576 particles, while the number of atoms in a single wall varies from 1260 to 8112 for walls with the smallest and largest lattice parameter, respectively. The distance between inner atomic layers of the walls equals 5.73 nm in each experiment, with approximate lateral sizes of the simulation box in the

xy plane being

nm. Periodic boundary conditions were applied to the system. When choosing the simulation setup, we followed the classical configuration of MD experiments on fluid flow between solid walls [

3]. The fluid particles interact with each other and with wall particles via the Lennard–Jones potential:

where

is the distance between particles,

and

are the parameters of the LJ potential, and

is a cutoff distance. As our aim was to analyze how the commensurability of the actual interatomic distances in fluid

and walls

affects the behavior of the system, we considered several configurations with different magnitudes of the

ratio. Also, it should be noted that introducing a particular (real) fluid at the current stage of the study is not suitable for examining a wide range of

ratios, as fluid–wall interaction is computed through empirical LJ parameters in that case. Therefore, in our experiments we chose a generic LJ fluid with reference parameters

Å and

eV for all considered cases with different lattice parameters of the

fcc walls. Moreover, for each value of the lattice parameter, we also considered three different strengths of fluid–wall interactions, namely

and

, as in [

3], while

remains the same in all experiments.

In the initial configuration, fluid particles were placed in an ideal

fcc crystal lattice, with a lattice parameter equivalent to an interatomic distance of 0.3 nm. The fluid was confined between solid walls, so that initial distances between fluid and wall particles equal

. After this, the system was left to reach an equilibrium configuration during the first

time steps, with the total length of each experiment being

time steps. All simulations used our previously developed in-house code for MD simulations on the GPU [

13], which performs integration of the equations of motion and calculations of interatomic forces and corresponding particle trajectories. Simulations were performed in NVT ensemble. Equations of motion were integrated using the velocity Verlet algorithm with a time step

fs. The mentioned approach was successfully used in our earlier study of friction between nanomaterials [

13].

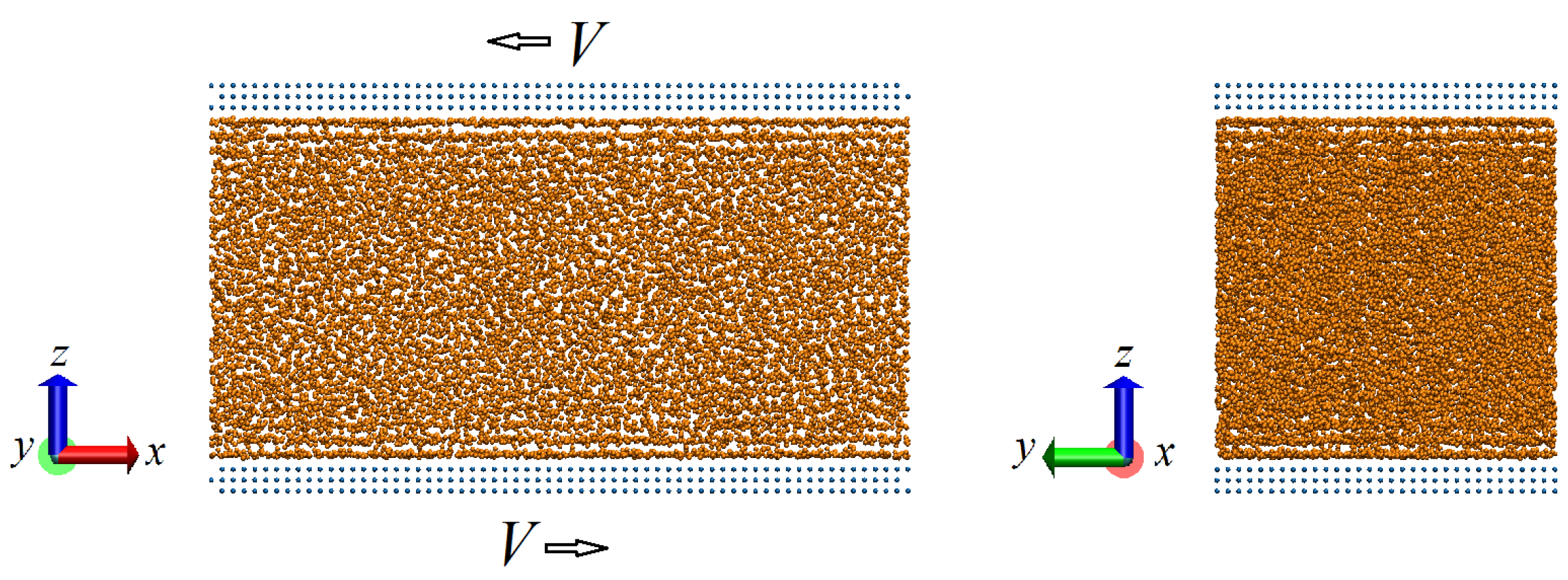

Snapshots of typical configurations of the equilibrated fluid confined between rigid walls and the schematics of the experiments are shown in

Figure 1 (all snapshots of atomistic configurations of the system were prepared with visual molecular dynamics software [

26]).

To track the process of the fluid reaching its equilibrium state, the normal components of the interaction force between fluid and walls were calculated during the equilibration of the system. Obtained time dependencies

are shown in

Figure 2a. It can be seen that the evolution of normal force on both walls is characterized by damped oscillations in the initial stages, related to the recoil of fluid atoms from the rigid walls. As expected, the dependencies obtained for each wall are characterized by almost the same magnitudes with opposite signs, due to the symmetry of the system. Also, calculated dependencies indicate that forces between fluid and wall are repulsive, considering the scheme of the experiment with respect to direction of

z axis (see

Figure 1), which may indicate slight compression of the fluid. To obtain a quantitative characterization of the system structure, radial distribution functions (RDFs)

were calculated for both confined fluid and the solid walls. It is worth noting that RDFs are a fundamental structural characteristic in molecular dynamics simulations [

27]. It provides direct insight into short- and long-range ordering within the system and is widely used to distinguish between liquid, crystalline, and amorphous states. RDFs, computed separately for the confined fluid and for the

fcc structured atoms composing the solid walls, are shown in

Figure 2b. As can be seen from the figure, the fluid RDF exhibits the typical form of a Lennard–Jones liquid: a pronounced first peak at the nearest-neighbor distance followed by damped oscillations that decay toward unity, reflecting short-range order without long-range correlations. In contrast, the RDF of the wall atoms shows the characteristic series of sharp peaks consistent with a face-centered cubic lattice. Both

are characterized by decreasing magnitude with the growth of the interatomic distance

ending with a sharp drop to zero due to the finite size of the system. Taken together, these results confirm that, after equilibration, the fluid is in a liquid state under confinement, while the walls maintain rigid crystal structure, as defined by simulation setup.

Starting from this equilibrium configuration, atoms in the bottom and top walls were shifted in x and −x directions, respectively, for another

time steps in every studied configuration, simulating constant relative motion of the rigid walls. During the simulations all important parameters needed for characterization of the system behavior were recorded.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, we present the main results of the performed molecular dynamics simulations. Our analysis focuses on several key quantities that characterize the fluid–wall interactions and the structural organization of the system. Specifically, we calculated the frictional forces between the fluid and moving walls. In each experiment, the friction force was computed as the total force exerted by fluid atoms on the confining walls, for the top and bottom walls separately. Normal components of the force acting on the walls also were calculated in order to estimate friction coefficients and normal pressure in the system. In addition, velocity distributions of the fluid particles were obtained to assess flow behavior and interfacial slip, while local atomistic configurations of the system were inspected to verify the structural states of the fluid near the crystalline walls.

As mentioned above, to examine how structural commensurability and interfacial interaction strength affects the dynamics of the confined fluid, MD simulations were performed for different lattice parameters of the solid walls, as well as for several values of the LJ energy parameter governing fluid–wall interatomic forces.

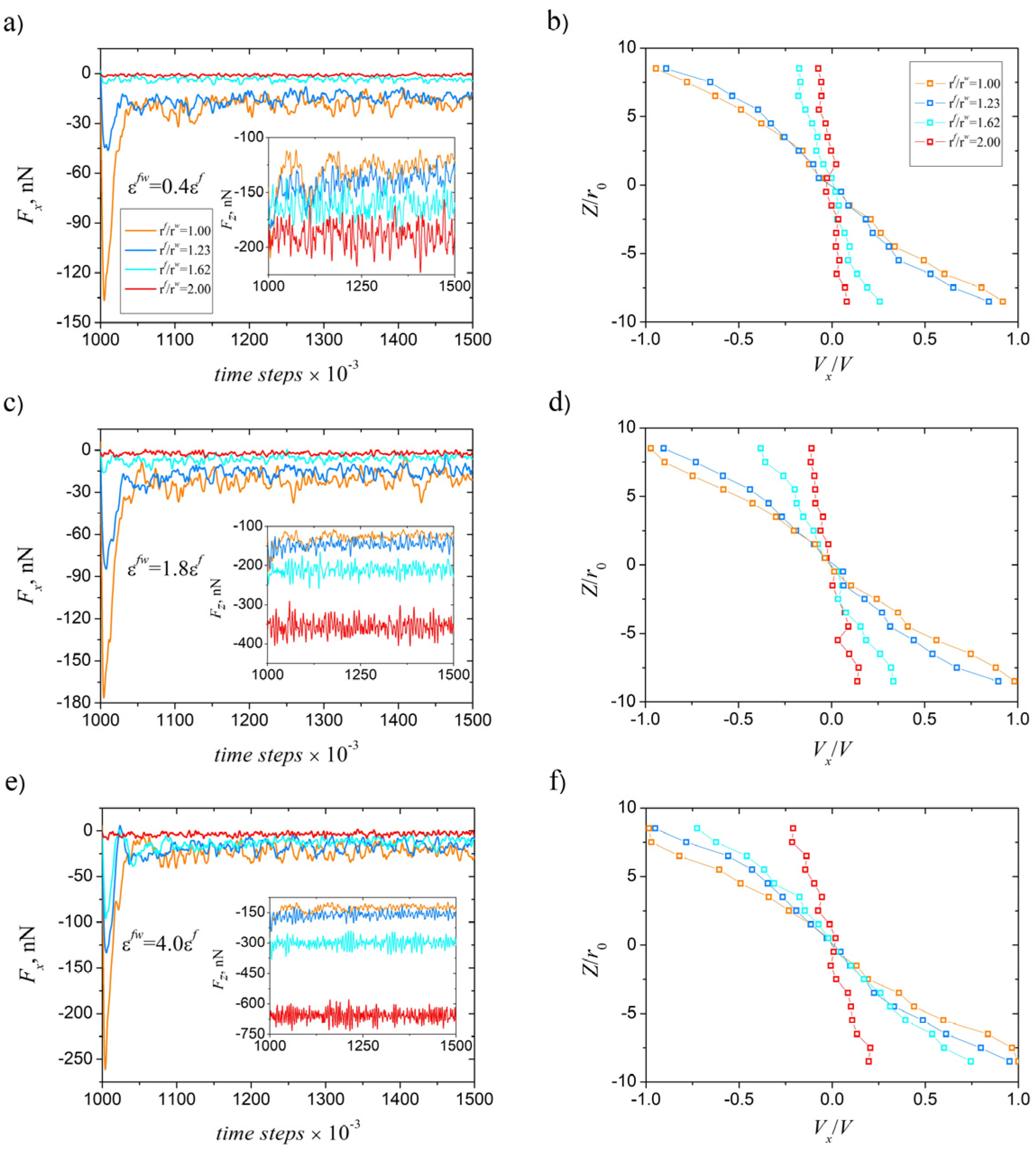

Figure 3 summarizes the time-dependent behavior of the confined system for four different ratios of the characteristic interatomic distances in the fluid and wall,

and

, with three different energy parameters for fluid–wall interaction (see previous section). The exact ratios

were chosen such that the lateral size of the system remained constant. As we intended to examine a wider range of commensurability by varying the lattice parameter of the

fcc walls while maintaining the same size of the system, the ratios

have been chosen so that some integer number of lattice units of

fcc wall provides the constant total length.

Figure 3a shows the evolution of the tangential and normal components (shown in the inset) of the force exerted by the fluid atoms on the bottom wall, while

Figure 3b presents the distributions of the

Vx components of velocities of fluid atoms along the normal coordinate

Z, within the volume between confining walls, calculated at the end of each experiment. The dependencies shown in

Figure 3a,b were obtained with

, while

Figure 3c,d together with

Figure 3e,f show similar data calculated for different values of

parameter, namely with

and

. Note that the friction force acting on the bottom wall is negative (i.e., directed opposite to its motion). Likewise, the normal component of the force is negative because it is directed toward the wall, consistent with the sign convention shown in

Figure 2a. It should be noted that the similar dependencies obtained for the top wall are virtually identical and therefore are not shown here.

In all presented experiments the largest magnitude of the friction force was observed in the configuration with

. All presented dependencies have a similar stiction spike in the initial region related to static friction, and some fluctuation near the actual value. The normal components of the forces acting on walls exhibit similar behavior, with clearly visible damped oscillations due to recoil of the fluid from rigid walls. Such behavior of friction forces is common and typically observed in MD simulations of nanotribological systems [

13]. The velocity distributions of the confined fluid for the

case displayed in

Figure 3b reveal the characteristic shear-driven flow profile imposed by the counter-moving walls. Typically, in MD simulations of confined fluids, the degree of slip at the interfaces can be inferred from the extrapolation of these profiles toward the solid boundaries and strongly depend on the energy of the fluid–wall interaction and several other factors [

3].

Furthermore, increasing the

ratio to

results in a significant decline in the initial stiction spike height, and a slight decrease in the friction force, while the normal component of the force shows a little bit stronger repulsion between the wall and fluid. A significant reduction in friction force is observed as the

ratio reaches

and above, reflecting the enhanced slip associated with increasing incommensurability. The velocity profiles in Panel 3b reveal a parallel structural trend: for

and slightly incommensurate configurations (), the velocity distribution exhibits a near-linear gradient characteristic of classical shear flow. As the ratio grows toward

, the profiles progressively flatten, approaching an almost constant distribution, indicating the strong slip and diminished shear within the fluid layer. This transition mirrors the reduction in friction and highlights the central role of interfacial commensurability in controlling flow behavior.

Increasing the LJ energy parameter of the fluid–wall interaction

leads to quantitative changes in system behavior. Thus, as may be seen from

Figure 3c,d, similar dependencies obtained at

are characterized by a higher stiction spike height for highly commensurate surfaces

00 and

, as well as much stronger repulsion for

. At the same time the velocity profile for

starts to approach linear shear flow more closely, compared to the

case. This tendency continues with further increase in the fluid–wall interaction energy, with the appearance of a prominent stiction spike for

and increased linearity in the corresponding velocity distributions at

(

Figure 3e,f). Such behavior demonstrates that stronger fluid–wall coupling can partially suppress slip and restore shear across the fluid layer despite significant incommensurability. However, the relative reduction in the friction force is still observable for

even at larger

magnitudes.

As seen in the inset panels of

Figure 3, the average magnitude of the normal force component

Fz depends on the ratio

for any given

. This behavior is caused by different numbers of wall atoms involved in the fluid–wall interaction. Therefore, a larger

Fz is observed for denser walls as expected. These forces can be equilibrated either by applying an external load to the walls, while allowing wall atoms to move in the

Z direction or by increasing the distance between walls and the corresponding volume of the simulation box. However, results obtained under such conditions may not always be comparable for different

and therefore the mentioned constraints are not considered in this study. Even though this feature and other simulation details may slightly affect calculated friction forces and velocity profiles, the obtained data are physically correct and were verified by additional simulations; therefore, we hope that it can be compared for different cases.

A detailed illustration of the changes in the shear induced velocity distribution of the fluid particles due to the incommensurability is shown in

Figure 4 through the atomistic configuration of the studied system. The presented configurations relate to the corresponding dependencies, as shown in

Figure 3b. Here the magnitude of the

Vx component of the velocity of each particle is denoted by a different color (coloring scheme and legend are shown in the figure).

The presented atomistic configuration map illustrates the above-mentioned behavior, where the incommensurability of interatomic distances destroys the shear flow, and fluid particles no longer follow the moving walls.

In the experiments presented in

Figure 3, the wall density parameter is in the range

. However, to explore the effect of incommensurability in the other direction, we also performed simulations with more sparse walls

. Moreover, to verify the assumption that reductions in friction force also can be achieved by increasing the repulsion between walls and fluid at commensurate interatomic distances, we also considered the case with a larger equilibrium distance

with

.

Figure 5 shows the comparison of the obtained time dependencies of the friction forces (Panel 5a) and velocity distributions (inset panel) with the reference configuration

.

In contrast to the pronounced friction reduction observed for incommensurate cases with

, the systems with

exhibit no significant decrease in friction force. A slight reduction is detected relative to the commensurate case (), but the magnitude of this effect remains modest and does not approach the strong reduction seen for larger ratios. This trend persists across the different values of the Lennard–Jones energy parameter

considered (see data presented below), indicating that simply increasing the spacing of the wall atoms beyond that of the fluid is insufficient to induce the large-scale interfacial slip. The velocity profiles likewise remain close to the near-linear form characteristic of classical shear flow, with only minor indications of increased slip at the walls.

The same figure also includes the results for a “hydrophobic” configuration, in which the interatomic distance ratio

is kept at unity but the equilibrium separation between wall and fluid atoms is increased by a factor of 1.67. In this case, a pronounced reduction in friction force is observed, comparable in magnitude to that of the strongly incommensurate systems (2). The velocity profile exhibits correspondingly enhanced slip, with significant flattening relative to the commensurate baseline. These findings clearly demonstrate that a stronger effective wall–fluid repulsion, achieved here by increasing the equilibrium separation

can promote interfacial slip to a degree similar to that produced by structural incommensurability.

It also should be noted that more substantial lowering of the

ratio led to a complete rearrangement of the system configuration as, starting from certain value of the wall lattice parameter, the fluid particles penetrate the walls and fill available spaces within the fcc crystal. Thus, configurations with

are not considered in this study. Nevertheless, since some reduction in friction is observed for sparser walls, additional study of such configurations may be warranted.

To quantify the slip between the wall and the fluid in the system, the slip length parameter

was calculated according to the method described in [

19] for all performed experiments. The obtained results are summarized in

Figure 5b. According to the definition in [

19], smaller slip lengths relate to the larger friction between fluid and solid walls, and, as expected, small

values were observed for the cases

2, while at increased separation and strong incommensurability, the system exhibits an extremely large slip length. This tendency was observed for all three values of

.

To further explore the system behavior at different conditions, four distinctive atomistic configurations of the fluid–wall interface at different simulation parameters are visualized below.

Figure 6a shows the bottom wall and first neighboring layer of fluid particles in the

xy plane for the commensurate case

. This is the most typical configuration, indicating partial solidification of the fluid near the interface [

14]. Here fluid particles are arranged according to the periodic wall structure due to the strong fluid–wall interaction and commensurability of interatomic distances.

Panel 6b presents the snapshots of the system with the same interatomic distances in the wall, but with a larger

parameter. In this case, the neighboring fluid layer is offset from the wall, which results in a reduction in the friction forces (see

Figure 5).

Figure 6c,d shows incommensurate cases with

and

, respectively. The latter case is similar to the configuration from

Figure 6b with prominent separation of the fluid from the wall and is also characterized by the reduction in friction. In contrast to this, in the case with sparse walls, fluid atoms stick between the nodes of the

fcc lattice; however, the characteristic interatomic distance between the fluid and walls does not change. All atomistic configurations shown in

Figure 6 are for the

case.

To obtain quantitative characteristics of the structure of the system at the fluid–wall interface, the in-plane RDF for fluid

and wall

were calculated for all presented configurations. The obtained data is shown in

Figure 6e–h. The calculated

are fully consistent with the visualized atomistic configurations. Thus, for the commensurate case

(

Figure 6h), the boundary fluid layer mirrors the crystal structure of the wall, and

, characterized by matching peaks (the third peak in

, relates to the interatomic distance between the atoms in the top and bottom plane of the wall, and therefore is absent for the single layer of fluid particles). The

calculated for the commensurate case with larger repulsion (

Figure 6f) has a typical fluid form (see

Figure 2b). The dependencies shown in

Figure 6g relate to the incommensurate case

. In this case the fluid layer also resembles the structure of the solid wall (the first peak in

relates to the interatomic distance

and is absent in

as the wall lattice parameter and corresponding distance

are larger). The

in the

case (

Figure 6h) is similar to

Figure 6f, with respect to shorter interatomic distances between the wall atoms.

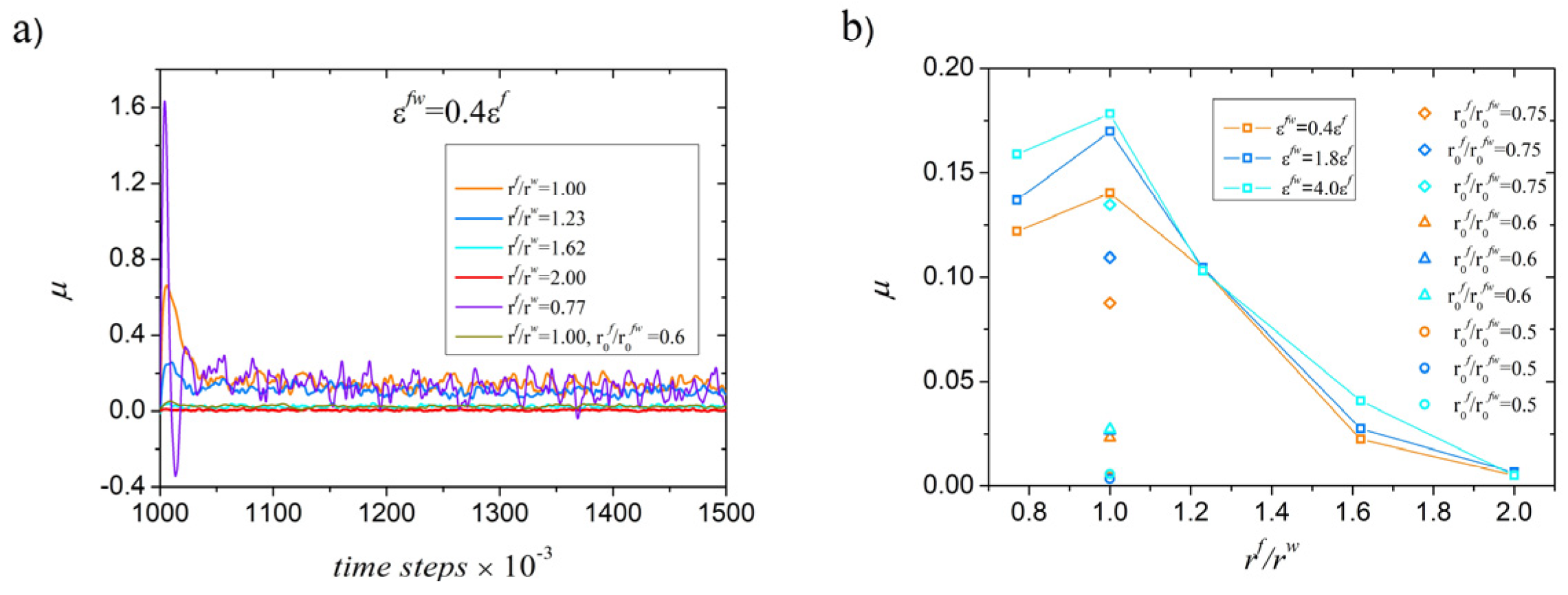

Finally, to generalize the obtained results, friction coefficients were calculated for all considered configurations.

Figure 7a shows the time dependencies of the friction coefficients

, defined as the ratio of the tangential component (friction) of the force between wall and fluid to the corresponding normal force, while

Figure 7b represents the mean values estimated through time averaging of the corresponding dependencies from

Figure 7a for the last

time steps. The resented dependencies display trends that are fully consistent with the direct force measurements described above. The highest coefficients are observed for the commensurate case (

), reflecting the strong coupling and minimal slip at the fluid–wall interface. A minor reduction in the friction coefficients is observed in cases where the commensurability ratio

moderately differs from unity in both directions. A pronounced decrease occurs as the ratio of interatomic distances increases to 1.62 and beyond, confirming the substantial friction reduction induced by structural incommensurability. The “hydrophobic” configuration, in which the equilibrium wall–fluid separation is increased while maintaining a

ratio, exhibits friction coefficients nearly as low as those of the strongly incommensurate systems, demonstrating that greater repulsion also can promote slip to a comparable extent.

Moreover, friction reduction and enhanced slip at hydrophobic surfaces in similar conditions was observed in both experiments [

29] and MD simulations [

30,

31], and the dependence

preserves its form at different values of the

parameter, thus increasing confidence in the repeatability of the obtained results.

It should be noted that, because we used arbitrary parameters of the interatomic potential, the obtained data should be seen as qualitative rather than quantitative, while the estimated numerical values of friction coefficient require further experimental [

32,

33,

34] verification. Nevertheless, we believe that the obtained results may provide valid insights into friction processes at fluid–solid interfaces that occur on the atomic level and may become useful in further studies in various areas of nanotribology. Moreover, future studies may extend these findings to more complex fluids and surfaces, which can be studied by more accurate MD simulations with precise interatomic force fields, to explore how the interplay of structure and surface chemistry can be exploited to develop novel low-friction coatings and lubricants. Solvation of surface atoms may also occur in some circumstances, depending on the molecular diameter of the fluid, thickness of the lubricant layer, surface roughness, etc. [

35,

36]. This may also be taken into account in more precise future studies.