Abstract

During the service life of bearings in ship systems, they operate under discrete constant operating conditions involving load levels, rotational speeds, and ambient vibrations. Traditional research mostly relies on idealized laboratory conditions of single constant load and constant speed, leading to significant discrepancies between the derived performance degradation patterns and actual on-site scenarios of marine bearings. In view of this, this study integrates the maximum entropy method (MEM) and Poisson counting principle (PCP) to analyze the variation law of the bearing performance degradation parameter—degradation probability—with changes in load ratio and rotational speed. Temperature gradients and impact vibrations are excluded to align with the actual experimental scope. The research results show that (1) the degradation probability of the optimal vibration performance state of the test bearings exhibits an overall nonlinear increasing trend during operation. (2) For the same time series, the degradation probability increases with the rise in load ratio and enters the non-zero phase earlier (indicating earlier degradation initiation). (3) Except for the 3rd–6th time series at 6000 r/min, the degradation probability within the same time series decreases with increasing rotational speed under discrete constant speed conditions.

1. Introduction

Marine rolling bearings serve as the “critical link” in ship power and transmission systems (e.g., main engines and propeller shafts), directly determining navigation safety and mission execution efficiency [1]. However, their service environment is uniquely harsh: cyclic dynamic loads (wave-induced fluctuations up to ±40% of rated load), intermittent speed changes (e.g., 4000–6000 r/min during berthing/maneuvering), high humidity (>90%), and salt spray corrosion (3.5 wt% NaCl concentration) [2]. According to the 2023 Marine Machinery Reliability Report by the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS), bearings account for 35% of all mechanical failures in marine transmission systems, and 60% of these failures originate from performance degradation under discrete variable conditions (i.e., constant load/speed for periods before switching) [3]. The economic impact is substantial: unplanned maintenance due to bearing degradation causes an average of 12–18 days of ship downtime yearly, with direct losses exceeding $2 million per vessel [4]. Accurately characterizing bearing degradation under marine-specific discrete conditions is therefore urgent for optimizing preventive maintenance and reducing operational risks [5,6,7].

Bearing performance degradation under discrete variable conditions is governed by “multi-physical field coupling” (contact stress, elastohydrodynamic lubrication, and adhesive wear), where load and rotational speed dynamically alter degradation mechanisms. Traditional research, however, often relies on idealized single-constant conditions (e.g., fixed load/speed) or linear assumptions, leading to limited applicability to real marine scenarios. Below is a critical review of existing studies, focusing on load- and speed-related degradation, and their gaps in the marine context.

1.1. Research on Load-Induced Degradation

Load is a primary driver of bearing fatigue and wear. Harris [8] established the classic contact stress model, quantifying the relationship between static load and fatigue life (L10 life). This model, however, assumes constant load and fails to capture the dynamic stress concentration in marine bearings, for example, wave-induced instantaneous stress overshoots (up to 1.5 times rated stress) accelerate subsurface crack initiation [9]. Later, Xu et al. [10] extended this to offshore wind turbine bearings (semi-marine environment) using the rainflow counting method to analyze load-induced fatigue. While relevant to cyclic loads, their study ignored the synergistic effect of load and speed (e.g., high load + low speed exacerbating oil film failure), which is prevalent in ship operations.

In marine-specific research, Zhao et al. [11] investigated corrosion-wear of bearing steel under salt spray but only under constant load/speed, leaving unaddressed how discrete load ratios (e.g., P/C = 0.25 vs. 0.35) quantitatively affect degradation probability. More recently, Wen et al. [12] studied marine bearing load degradation using a Wiener process model, but it required predefined degradation thresholds—unrealistic for marine bearings, where healthy-state boundaries are ambiguous due to environmental noise.

1.2. Research on Speed-Induced Degradation

Rotational speed directly influences lubrication performance and centrifugal forces. He et al. [13] proposed a mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) model which shows that oil film thickness is proportional to the 0.7th power of speed. This model is valid for steady speed but fails under discrete speed changes: a sudden drop from 6000 to 4000 r/min can reduce oil film thickness to <0.1 μm, causing metal-to-metal contact and adhesive wear [14]—a common scenario during ship speed adjustments.

Data-driven methods have been applied to speed-related degradation: Wang et al. [15] used a gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural network to predict land-based bearing degradation under variable speed, but it required 10,000+ labeled data points—scarce for marine bearings (service life up to 5 years, limited failure data). For marine applications, Abboud et al. [16] developed envelope analysis for variable-speed bearing vibration but focused on fault diagnosis (not degradation prognosis) and did not account for the “small-sample” challenge of marine bearings.

1.3. Gaps in Existing Research

Three critical gaps persist for marine bearing degradation under discrete variable conditions:

Scenario mismatch: Most studies target continuous variable conditions (e.g., linearly increasing load), while marine bearings operate in discrete constant states (e.g., 4000 r/min for 2 h, then 6000 r/min) [17].

Method limitations: Mechanistic models (e.g., Harris model) rely on linear assumptions; data-driven models (e.g., GRU) need large datasets; neither adapts to marine “small-sample, high-noise” data [18].

Marine-specific coupling: Few studies quantify how load-speed coupling (e.g., P/C = 0.30 + 6000 r/min vs. 4000 r/min) affects degradation—critical for ships, where load and speed often change in tandem.

1.4. Novelty of This Study

To address these gaps, this study integrates the maximum entropy method (MEM) and Poisson counting principle (PCP) into a novel framework—maximum entropy Poisson counting method (MEPCM)—for marine bearing degradation analysis. The novelty lies in three aspects:

Method adaptability for marine data: MEM requires no prior assumptions about data distribution (unlike Weibull/Normal models) and maximizes utilization of small samples [19]—ideal for marine bearings, where degradation data is scarce. Wang et al. [20] validated MEM for land-based bearing vibration analysis, but this study extends it to define “healthy-state envelopes” for discrete marine conditions.

Degradation probability quantification: PCP effectively models discrete abnormal events (e.g., vibration data outside the MEM healthy envelope) [21]. Unlike traditional threshold-based methods, PCP counts outliers to calculate degradation probability (λₙ), avoiding arbitrary threshold settings.

Focus on discrete marine conditions: Unlike previous studies on continuous variable conditions, this work targets the discrete constant states (P/C = 0.25, 0.30, 0.35; 4000, 5000, 6000 r/min) that dominate marine operations, filling the gap in scenario-specific degradation analysis.

The specific objectives are (1) to collect vibration data of marine-relevant 6008 bearings under discrete load/speed conditions; (2) to use MEPCM to calculate degradation probability; and (3) to reveal how load ratio and rotational speed quantitatively affect degradation trends, providing a theoretical basis for marine bearing health management.

2. Performance Degradation Model

2.1. Definition of Intrinsic Sequence

The intrinsic sequence is defined as the vibration acceleration data collected during the optimal operational period of the bearing, i.e., the phase where the root mean square (RMS) of vibration remains stably low (coefficient of variation <5%) and no wear debris or abnormal noise is detected [22]. This sequence represents the healthy baseline and is expressed as X1.

where x1(k) is the kth RMS value of vibration acceleration in X1, and N is the number of data points; w stands for the order number of time series Xw; r is the number of time series; xw(k) is the kth performance data in time series Xw. Subsequent time series (X2 to Xr) are collected at regular intervals to track degradation.

2.2. Solving PDF Using MEM

Information entropy quantifies the “disorder” of a system; for bearings, increasing entropy indicates growing uncertainty in performance degradation [23]. Based on MEM, the PDF of a sequence is most unbiased when its information entropy is maximized.

For the wth time series Xw, the information entropy Ew(x) is

where Ωw represents the feasible region of the w-th data sequence Xw; Ωw = [xwmin,xwmax]; xwmin and xwmax are the minimum and maximum values of the data in the w-th data sequence Xw, respectively; fw(x) is the maximum entropy probability density function of the w-th data sequence Xw; lnfw(x) is the natural logarithm of the maximum entropy probability density function fw(x).

To maximize Ew(x) under constraints of normalized probability and known origin moments, the PDF is expressed as [22]

where c0w and ciw represent the first Lagrange multiplier and the (i + 1)-th Lagrange multiplier, respectively, for the w-th data sequence Xw of the bearing; i is the order of the raw moment of the bearing sample, where i = 1, 2, …, j; j is the order of the highest-order raw moment of the bearing sample, typically taken as j = 5.

Normalization:

Origin moment matching:

Here, miw denotes the ith order raw moment of the wth data sequence Xw of the bearing, and j = 5 (selected based on convergence tests [19]).

The Lagrangian function for the w-th data sequence Xw of the bearing can be represented as Lw(x) [22].

The first Lagrange multiplier c0w should satisfy the following condition:

The remaining Lagrange multipliers must satisfy the following conditions:

To ensure solution convergence, the original data interval is mapped to interval [−e, e] by the substitution of variable. Let

where aw and bw are mapping parameters for the data sample of the time series Xw; t ∈ [−e, e] and e has a value of 2.71828.

Based on the mapping of the original data in the interval [−e, e], the PDF can be obtained as [22]

In order to be more adaptable to researchers’ habits, the variable t is replaced by the variable x.

Based on the principle of maximum entropy and integral interval mapping, the probability density function of X1 is derived as f1(x).

2.3. Solving Degradation Probability Using Poisson Counting Principle (PCP)

The PCP models degradation as a random counting process, where the number of “abnormal” events (vibration data outside the healthy envelope) follows a Poisson distribution [22].

Define the MEM healthy envelope. Set a significant level α, α ∈ [0, 1], so the confidence level P is given by

The MEM estimated interval is [XL, XU] for a given confidence level P, and the lower bound value XL should meet that XL = Xα/2.

And

The upper boundary value should meet that XU =X(1 − α)/2. And

So, the MEM estimated interval for continuous variable x can be given by

According to Equation (15), the MEM estimated interval [XL1, XU1] can be calculated for the intrinsic time series, where XL1 is the lower bound value and XU1 is the upper bound value of the MEM estimated interval of the intrinsic series.

According to the time series, the degradation process of accuracy is defined as a Poisson process, and the degradation probability is taken as a parameter of the counting process [22]. Based on the Poisson counting principle, record the number Nn that performance data of the nth time series is outside the estimated interval [XL1, XU1]. Then the variation frequency λn (frequency of abnormal events) can be given as Equation (17) for the nth time series.

where Nn1 is the number that performance data is less than XL1 for the nth time series; Nn2 is the number that performance data is more than XU1 for the nth time series; n is the sequence number of time series, n = 1, 2, 3, …, r.

Then, the specific patterns of how the degradation probability of characteristic parameters changes with load and speed variations can be analyzed for rolling bearings under discrete constant conditions.

3. Experimental Verification

3.1. Experimental Setup and Bearing Specifications

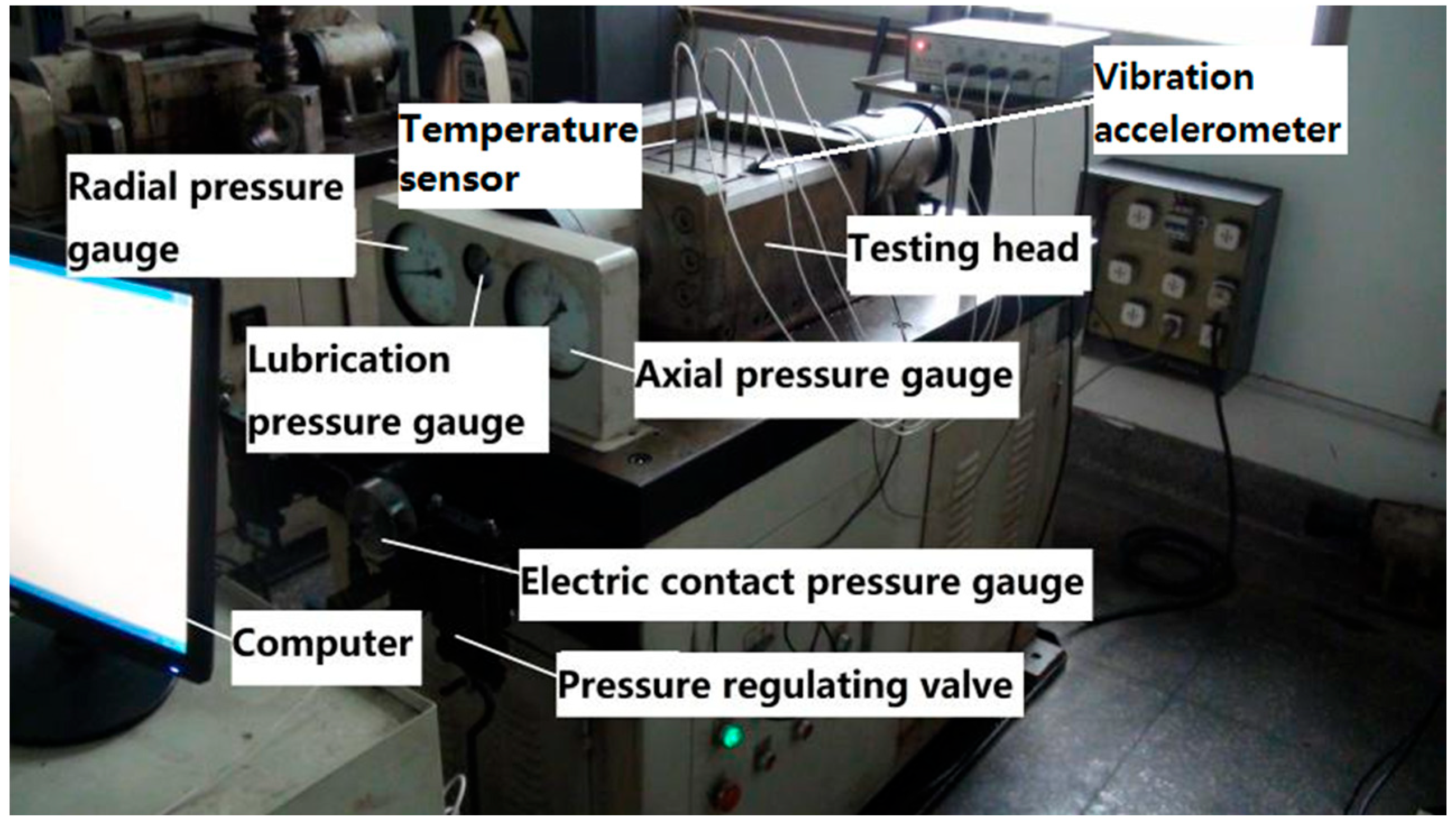

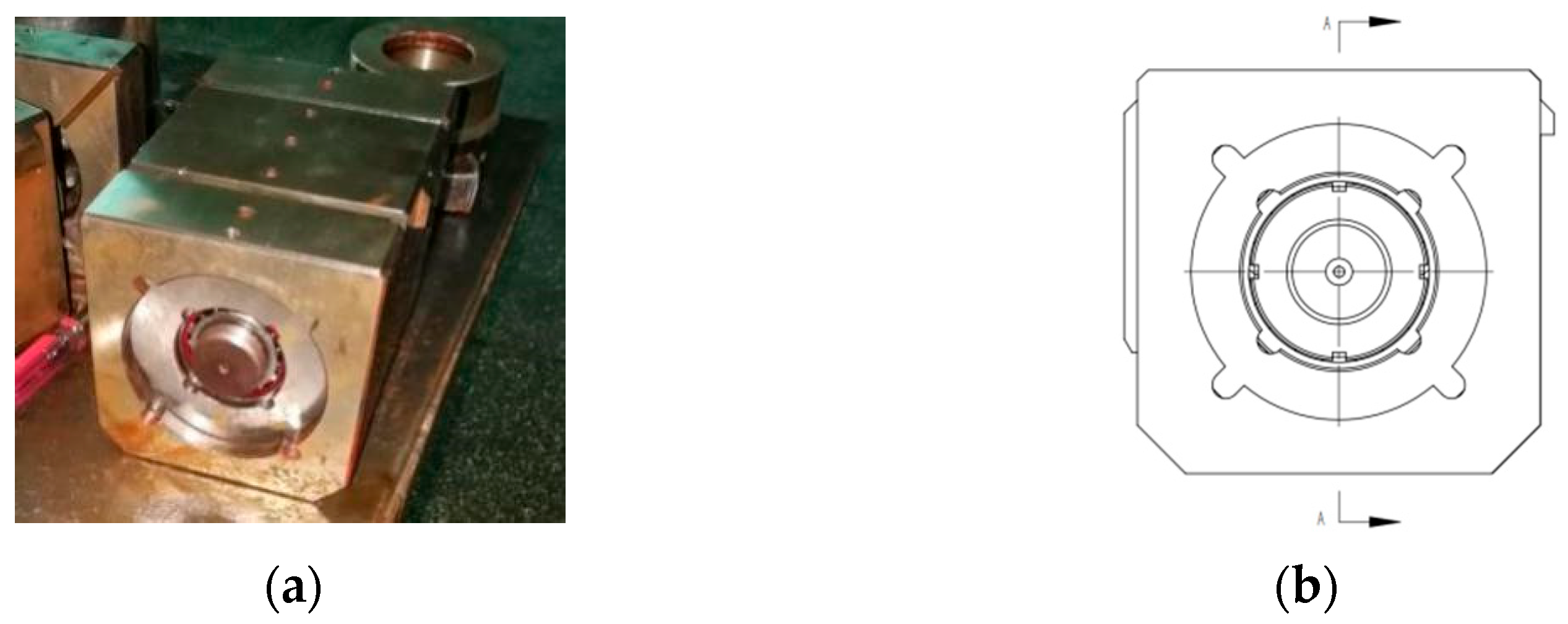

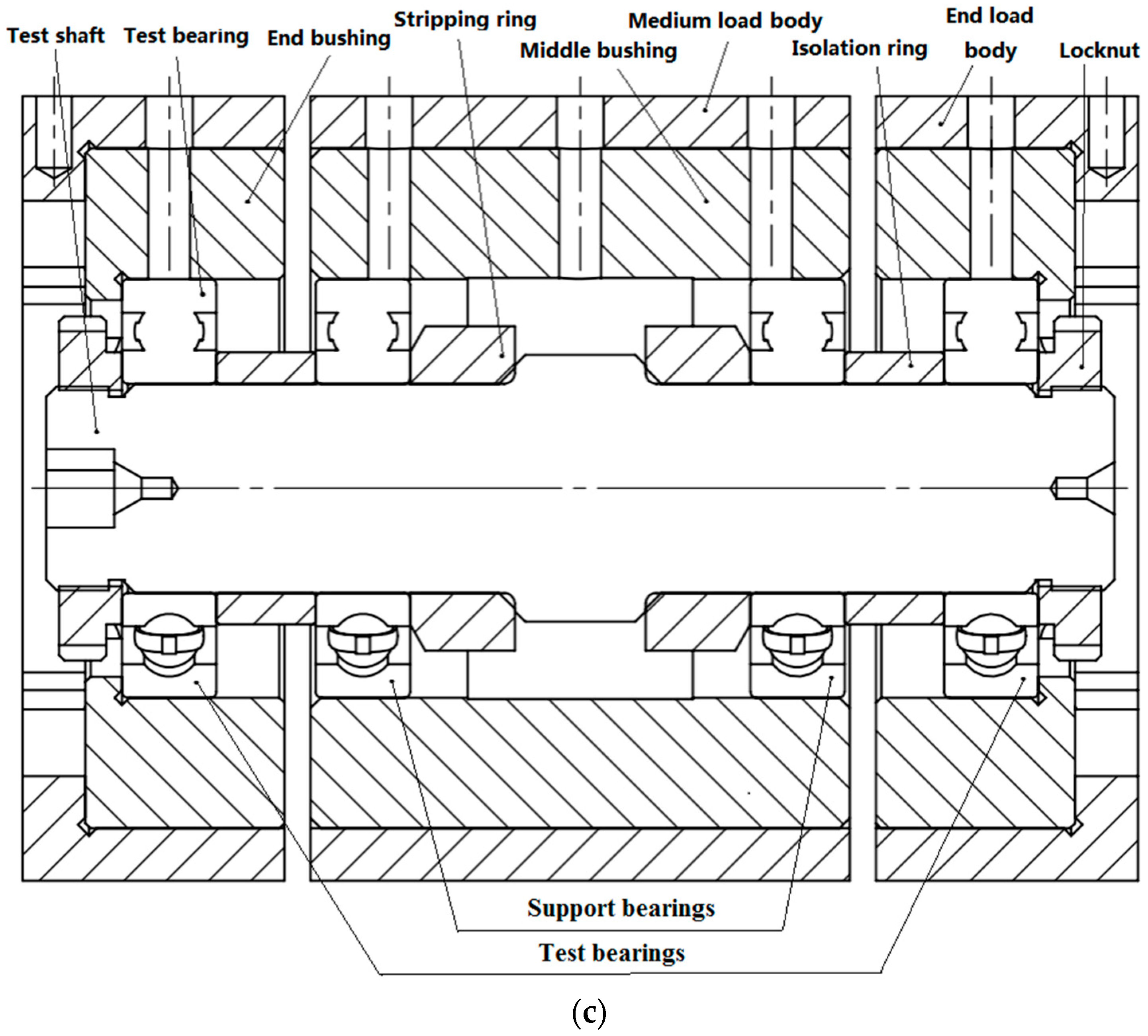

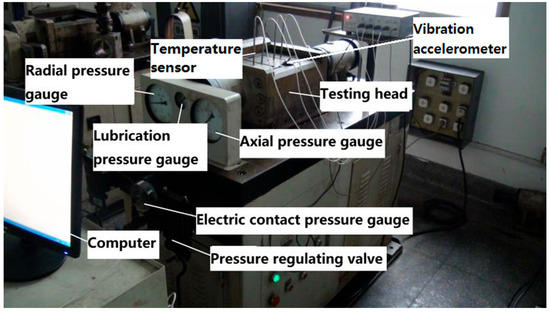

The experimental data are collected in Hangzhou Bearing Test and Research Center. This is a strength lifetime test on the vibration performance of rolling bearings. The test machine model is an ABLT-1A. This machine mainly consists of a test head seat, test head, transmission system, loading system, lubrication system, and computer control system. The physical drawings of the testing machine and test head are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2a–c [22].

Figure 1.

Physical drawing of testing machine.

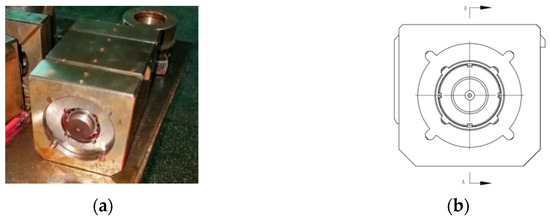

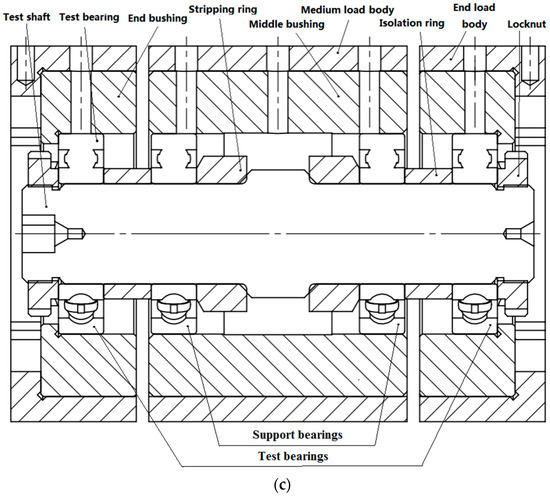

Figure 2.

Testing head. (a) Physical drawing, (b) main view, (c) section view.

The vibration data were acquired using a YD-1 piezoelectric accelerometer (Far East Vibration System Engineering Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) with a measuring range of ±2000 g and a resolution of 0.0001 g. The sensor was mounted on the test head housing using magnetic adhesion at the 12 o’clock position to ensure direct measurement of radial vibration. Signals were conditioned and digitized using a PCI-1711U data acquisition (DAQ) board at a sampling frequency of 20 kHz, which adequately captures bearing characteristic frequencies (typically < 5 kHz). The bearing vibration signal is defined as a time series of root mean square (RMS) values, where each data point represents the RMS of the vibration amplitude measured over a one-minute window, and is expressed in m/s2.

The number and information of the bearings used in the test are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of angular contact ball bearings with type 6008.

3.2. Experimental Design

The experiments focused on discrete constant conditions (load/speed held constant), simulating typical marine operating scenarios (e.g., steady cruising at constant speed/load). Two sets of tests were conducted:

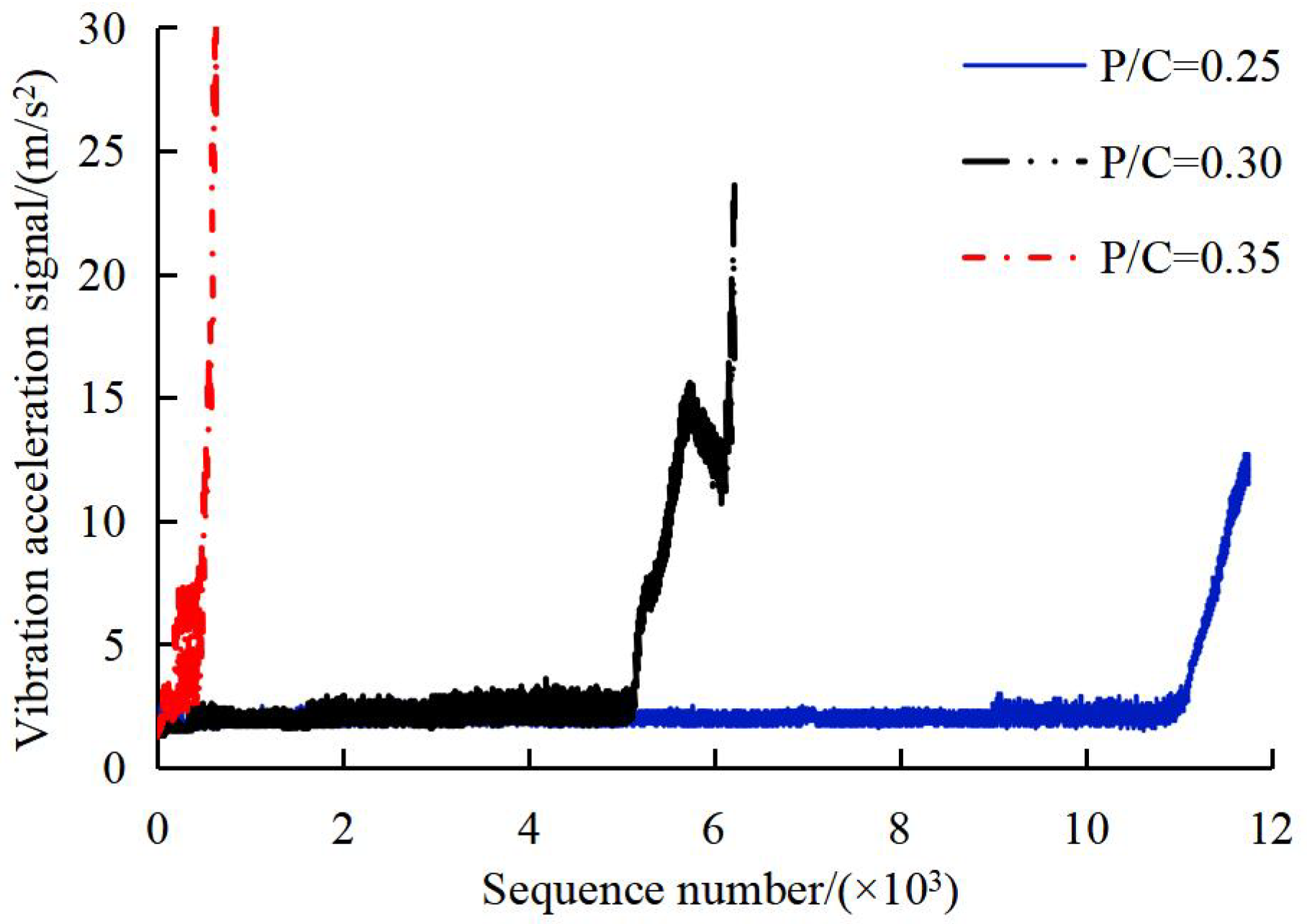

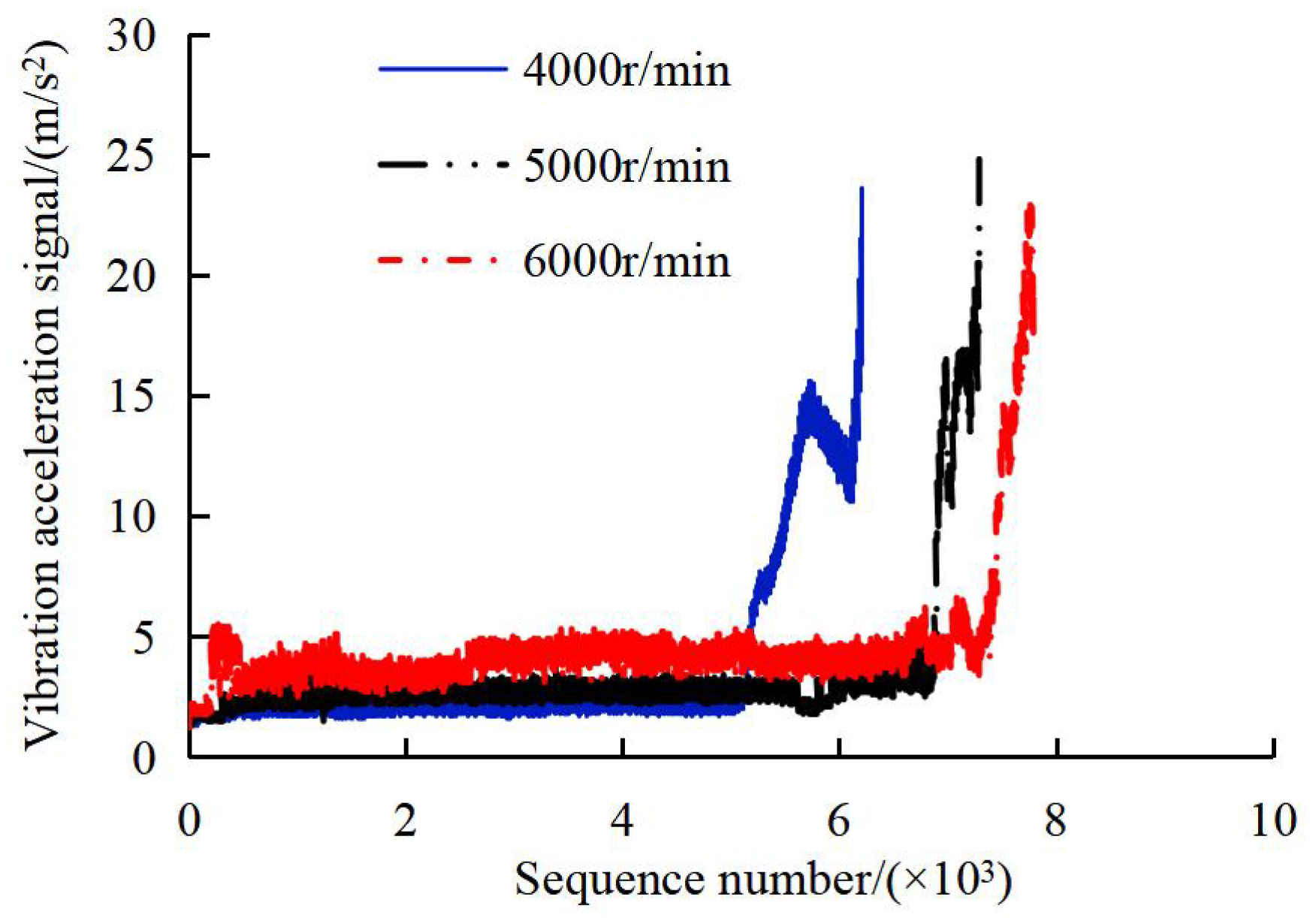

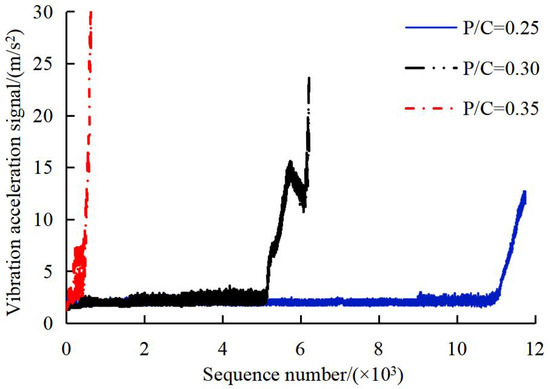

(1) Constant speed tests: Rotational speed was maintained at 4000 r/min (selected to avoid extreme centrifugal forces while representing medium-load marine operation [22]), with load ratios of P/C = 0.25 (Fr = 3.5 kN, Fa = 3.85 kN), 0.30 (Fr = 4.18 kN, Fa = 4.58 kN), and 0.35 (Fr = 4.87 kN, Fa = 5.35 kN) applied successively. The experiments lasted for 11,761, 6216, and 640 min, during which 11,761, 6216, and 640 data signals were collected, respectively. For each load condition, vibration acceleration RMS values were recorded throughout the bearing service life, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The bearing vibration acceleration signal under different load conditions.

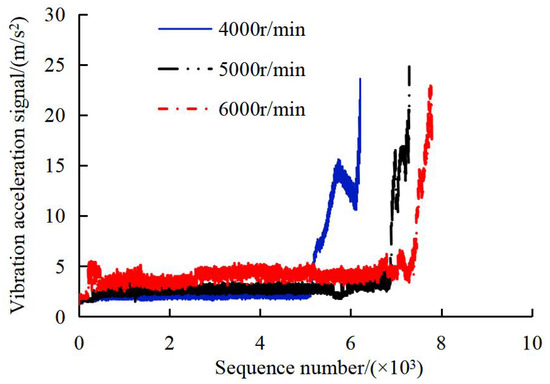

(2) Constant load tests: Load was fixed at P/C = 0.30 (Fr = 4.18 kN, Fa = 4.58 kN) for all speed conditions, with rotational speeds of 4000, 5000, and 6000 r/min. The experiments lasted for 6216, 7299, and 7793 min, during which 6216, 7299, and 7793 data signals were collected, respectively. Vibration data sequences are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Bearing vibration acceleration signal under different rotational speeds.

3.3. Signal Preprocessing

To address MEM’s sensitivity to environmental noise, vibration signals were preprocessed using wavelet denoising and band-pass filtering.

Symlet 8 wavelet [24] (level 5 decomposition) and 10–1000 Hz band-pass filter [25] were used to remove high-frequency electrical noise (>2000 Hz) and isolate bearing-related vibration (excluding low-frequency structural resonance and high-frequency sensor noise).

In the relationship between the physical data and Equation (1), each data point is represented by the root mean square (RMS) value derived from a one-minute vibration acceleration sample. For explanation, the filtered data sequence acquired under conditions of 4000 r/min and a load ratio of P/C = 0.30 was utilized. The sequence of 6216 data points was partitioned into ten sub-series, designated as X1 to X10, with the following ranges: X1(x1(1)–x1(630)), X2(x2(361)–x2(1260)), X3(x3(1261)–x3(1890)), X4(x4(1891)–x4(2520)), X5(x5(2521)–x5(3150)), X6(x6(3151)–x6(3780)), X7(x7(3781)–x7(4410)), X8(x8(4411)–x8(5040)), X9(x9(5041)–x9(5670)), and X10(x10(5671)–x10(6216)).

3.3.1. Degradation Probability Under Varying Load Ratios

Table 2 and Table 3 present the MEM-derived origin moments, Lagrange multipliers, and mapping parameters for the intrinsic sequence under different load ratios. The MEM estimated intervals (Table 4) widen with increasing load, indicating greater uncertainty in the healthy state.

Table 2.

Original moments of intrinsic sequences under different load ratios.

Table 3.

Lagrange multipliers and mapping parameters of intrinsic sequences under different load ratios.

Table 4.

MEM estimated intervals of intrinsic sequences under different load ratios.

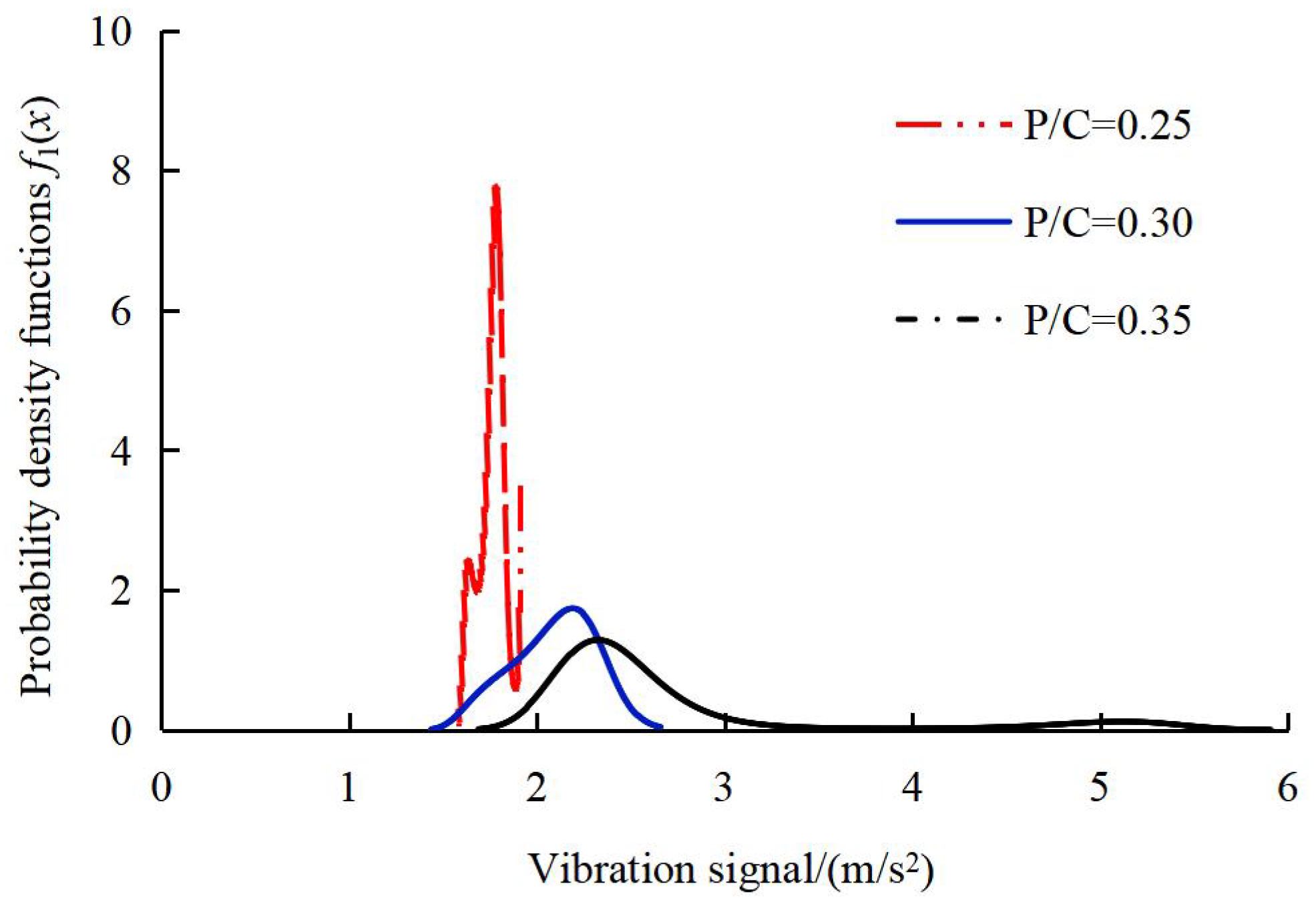

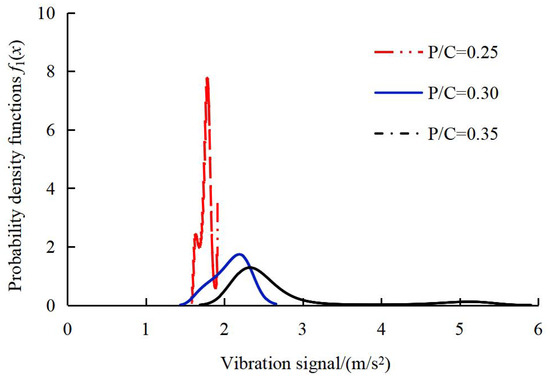

The PDF f1(x) of the intrinsic sequences under different load conditions was calculated, with the results shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Probability density functions of intrinsic sequences under different load conditions. The black dashed line represents the PDF f1(x) of the intrinsic sequences X1 in the vibration acceleration signal when P/C = 0.35.

With the significance level set to 0, the estimated intervals [XL, XU] for X1 under different load conditions were determined using the maximum entropy method, as presented in Table 4.

Under varying load conditions, the number of vibration sequences falling outside the maximum entropy estimated intervals [XL, XU] of intrinsic sequences (i.e., outlier counts) was recorded, with results summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Outlier counts of vibration sequences under different load ratios.

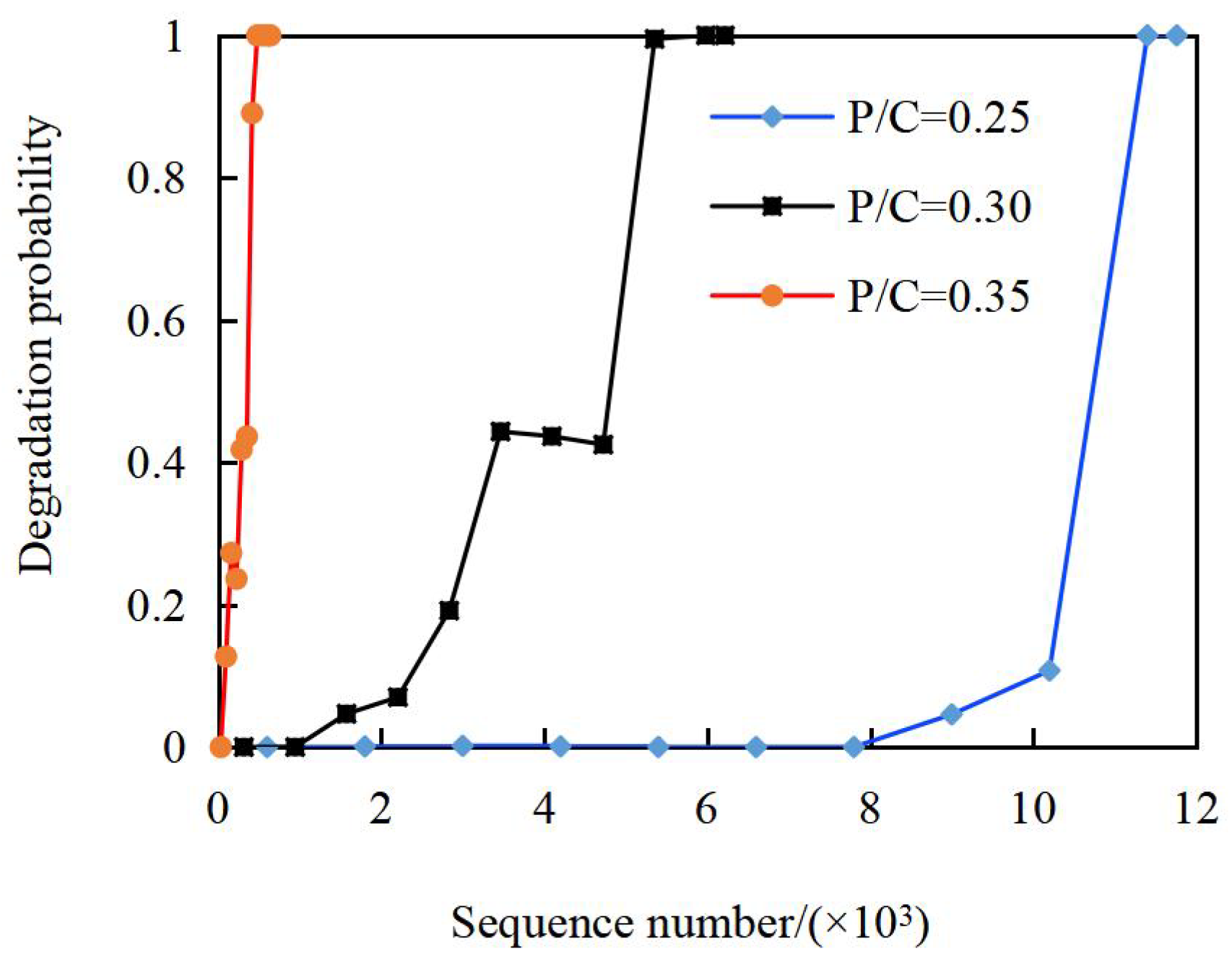

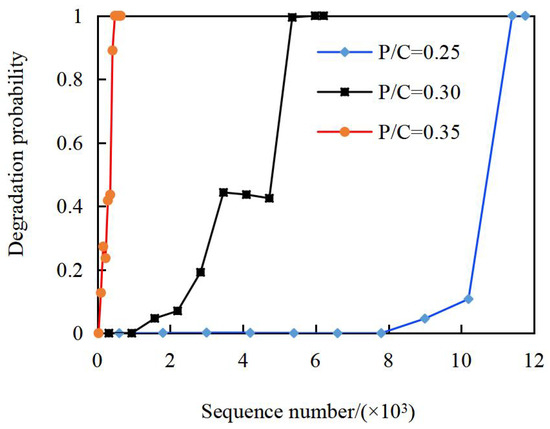

Based on the Poisson counting principle, the frequencies of sample data falling outside the ten maximum entropy estimation intervals [XL, XU] under different load conditions were calculated, yielding the results [λ1, λ2, λ3, λ4, λ5, λ6, λ7, λ8, λ9, λ10] as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Degradation probability under different load ratios.

Figure 6 presents the combined vibration data sequences and degradation probability curves under different load ratios, enabling direct comparison of raw vibration trends with computed degradation probabilities. This integrated visualization reveals how increasing load ratios accelerate both vibration growth and probabilistic degradation. Outlier counts (Table 5) and degradation probability curves (Figure 6) show three key trends:

- (1)

- For all load ratios, degradation probability exhibits an overall nonlinear increasing trend (consistent with cumulative wear).

- (2)

- Higher load ratios accelerate degradation: At P/C = 0.35, the probability enters the non-zero phase at the 2nd sequence; at P/C = 0.25, this occurs at the 7th sequence.

- (3)

- At P/C = 0.35, the probability reaches 1.00 (full degradation) by the 8th sequence, compared to the 10th sequence at P/C = 0.25.

3.3.2. Degradation Probability Under Varying Rotational Speeds

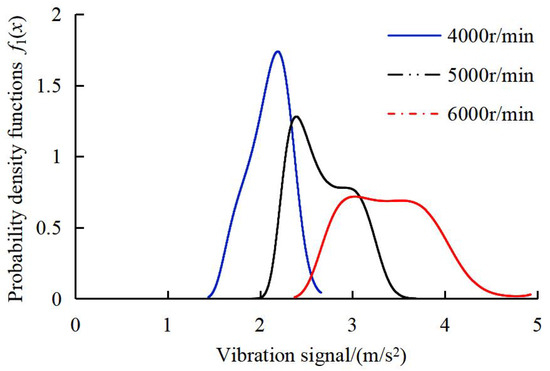

Table 6 and Table 7 present the MEM-derived origin moments, Lagrange multipliers, and mapping parameters for the intrinsic sequence under different speeds. The MEM estimated intervals (Table 8) widen with increasing speed, indicating greater uncertainty in the healthy state.

Table 6.

Original moments of intrinsic sequences under varying rotational speeds.

Table 7.

Lagrange multipliers and mapping parameters of intrinsic sequences under varying rotational speeds.

Table 8.

MEM estimation intervals of intrinsic sequences under different rotational speeds.

Using the maximum entropy method with a significance level of α = 0, the estimation intervals [XL, XU] for intrinsic sequences under different rotational speeds were derived, as shown in Table 8.

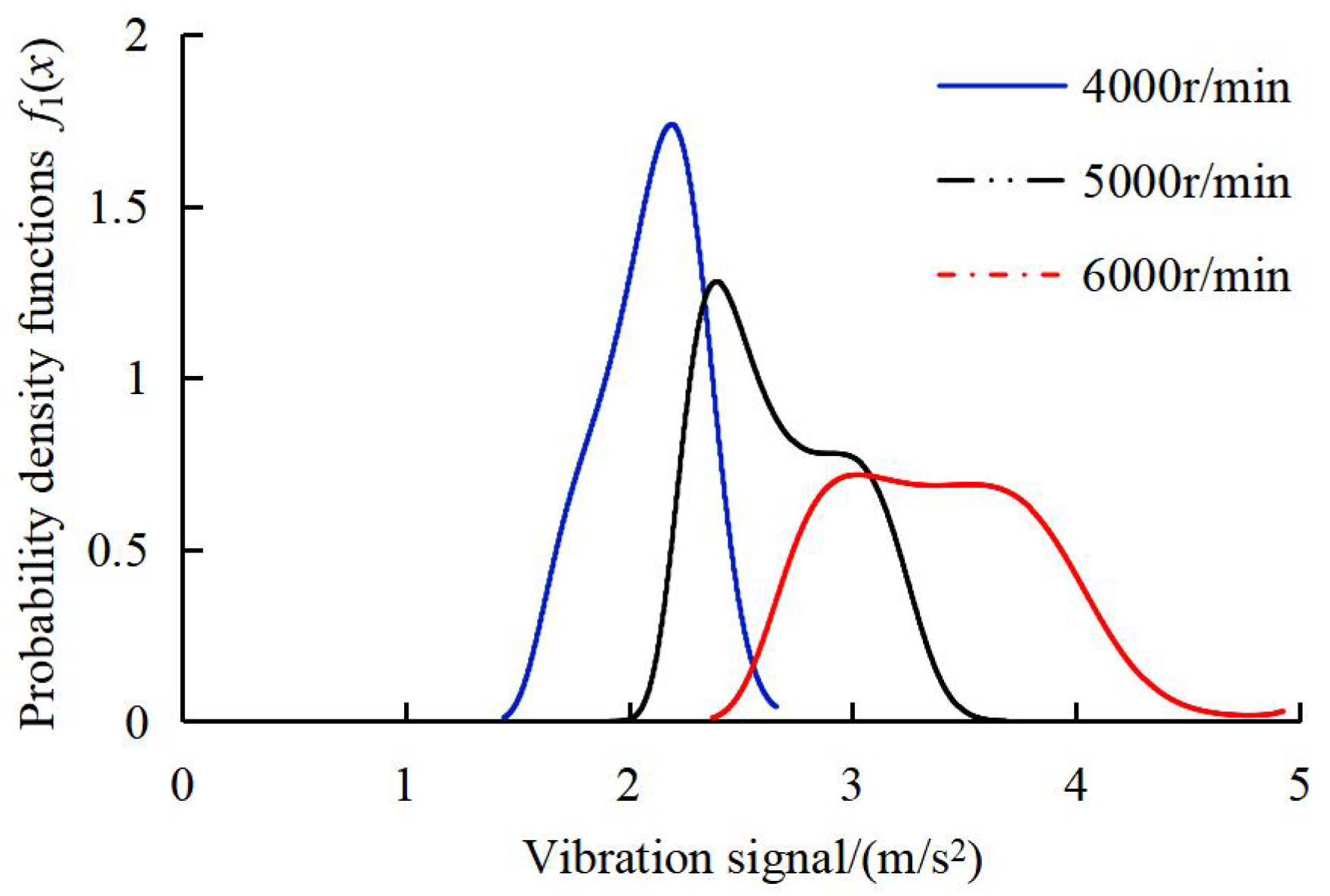

The probability density functions of intrinsic sequences, denoted as f1(x), were computed under different rotational speeds, with results visualized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

PDFs of intrinsic sequences under different rotational speeds.

Under varying rotational speeds, the number of vibration sequences falling outside the MEM estimation interval [XL, XU] of intrinsic sequences (i.e., outlier counts) was recorded, with results presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Outlier counts of vibration sequences under different rotational speeds.

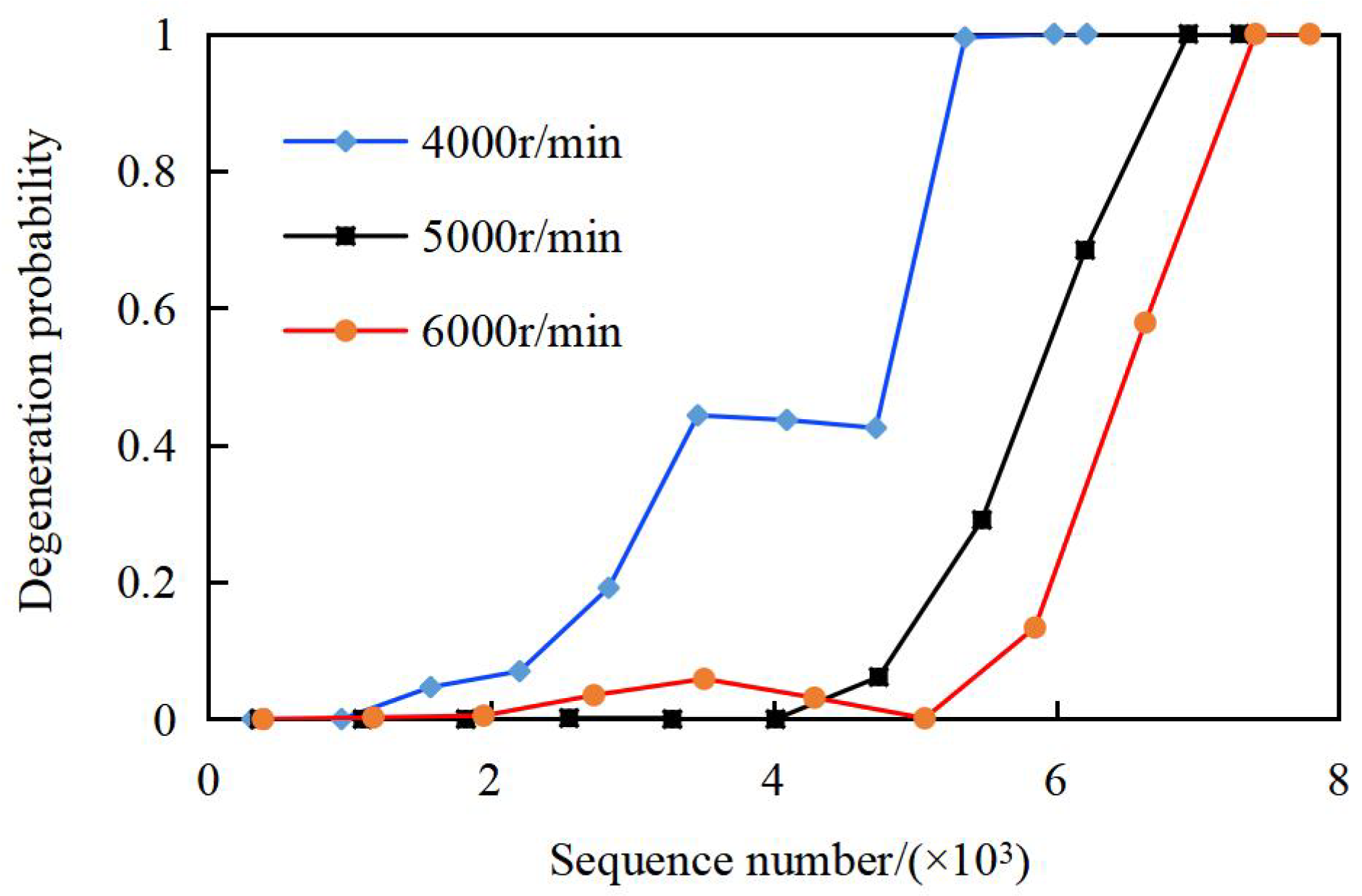

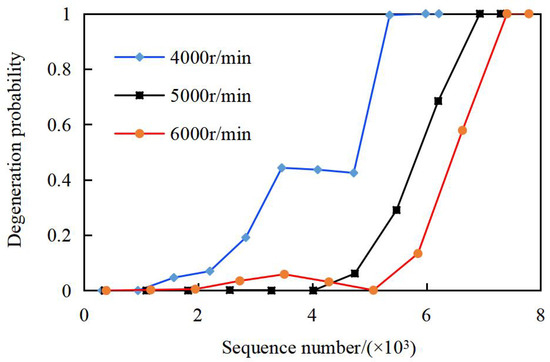

Based on PCP, the frequencies [λ1, λ2, λ3, λ4, λ5, λ6, λ7, λ8, λ9, λ10] of sample data points falling outside the ten MEM estimation intervals [XL, XU] under varying rotational speeds were calculated, with results presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Degradation probability under different rotational speeds.

Similarly, Figure 8 combines the original vibration data with degradation probability curves under different rotational speeds, facilitating explicit joint analysis of speed effects on both vibration characteristics and degradation progression. Outlier counts and degradation probability curves show the following:

- (1)

- Except for the 3rd–6th sequences at 6000 r/min, degradation probability decreases with increasing speed for the same time sequence. For example, at the 8th sequence, λ8 = 0.85 (4000 r/min), 0.63 (5000 r/min), and 0.36 (6000 r/min).

- (2)

- Higher speeds delay the onset of non-zero degradation: At 6000 r/min, the probability remains near zero until the 3rd sequence; at 4000 r/min, this occurs at the 2nd sequence.

- (3)

- The temporary probability decrease (5th–7th sequences at 6000 r/min) is attributed to data variability (not “self-healing” as physical wear is cumulative [26]). This fluctuation likely stems from transient lubrication improvements (e.g., temporary oil film thickening) or measurement noise, highlighting the need for repeated tests.

3.3.3. Online Implementation Feasibility

Regarding practical implementation, the MEPCM technique can be adapted for online bearing monitoring with certain considerations. The computational load is relatively low; processing one 1 min sample requires approximately 1.5 s on a standard embedded system (ARM Cortex-A53, 1.2 GHz), enabling near-real-time analysis. For continuous monitoring, data storage requirements are manageable: vibration RMS values (double precision, 8 bytes each) accumulated at 10 min intervals would consume only ~42 KB per day per bearing.

The main limitations for online deployment include (1) the need for initial baseline data to establish healthy state parameters; (2) sensitivity to significant operational condition changes requiring model recalibration; and (3) the current method’s validation under constant conditions rather than highly transient operations.

Optimization strategies include (1) implementing adaptive thresholding based on operational history; (2) developing condition-triggered analysis rather than continuous monitoring; and (3) incorporating multivariate analysis with temperature and acoustic data for improved robustness. These aspects will be addressed in our subsequent research focused on field deployment.

3.3.4. Practical Implications

The results provide actionable insights for marine bearing maintenance:

- (1)

- Load optimization: Limiting load ratios to <0.30 can delay degradation onset by 5+ time sequences (in this study), reducing unplanned downtime.

- (2)

- Speed adaptation: For discrete speed changes, operating at higher speeds (e.g., 5000–6000 r/min instead of 4000 r/min) under constant load can lower short-term degradation probability, provided lubrication is maintained.

- (3)

- Monitoring guidance: The MEPCM enables real-time degradation assessment using simple vibration RMS data, requiring minimal computational resources (suitable for on-board monitoring systems with limited storage/processing power).

4. Conclusions

This study proposes the maximum entropy Poisson counting method (MEPCM) to analyze rolling bearing degradation under discrete constant conditions (marine-relevant scenarios). Key conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The degradation probability of the optimal vibration state exhibits an overall nonlinear increasing trend with operation time, driven by cumulative wear and lubrication degradation.

- (2)

- For the same time sequence, degradation probability increases with load ratio (P/C = 0.35 > 0.30 > 0.25) and enters the non-zero phase earlier, confirming that higher loads accelerate degradation.

- (3)

- Except for transient fluctuations (attributed to data variability), degradation probability decreases with increasing rotational speed (6000 > 5000 > 4000 r/min) for the same time sequence, as higher speeds improve lubrication (thicker oil film) and reduce contact stress.

This study focuses on load and speed, without considering salt spray corrosion or humidity—key marine factors. Future work will integrate corrosion-wear models into the MEPCM and validate it using on-board ship data. Additionally, multi-criteria assessment (e.g., combining degradation probability with wear debris concentration) will be explored to enhance robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.; Methodology, L.Y.; Validation, J.P.; Supervision, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Bo Liang and Jingxuan Pei were employed by the company SINOMACH Academy of Science and Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| w | order number of time series |

| r | number of time series |

| N | number of original data |

| i | order number of origin moment |

| j | highest order number of origin moment |

| xw(k) | kth performance data in time series |

| Xw | wth time series |

| fw(x) | probability density function of time series |

| ciw | Lagrange multiplier |

| Ew(x) | information entropy of time series |

| Ωw | feasible domain for the data sample of time series |

| lnfw(x) | logarithmic value of fw(x) |

| miw | order origin moment |

| aw; bw | mapping parameters |

| c0w | first Lagrange multiplier |

| ciw | (i + 1)th Lagrange multiplier |

| Lw(x) | Lagrangian function |

| XL1; XU1 | lower and upper bound values of the maximum entropy estimated interval of the intrinsic time series |

| Nn | performance data of the nth time series outside the estimated interval [XL1, XU1] |

| Nn1; Nn2 | numbers that performance data less than and more than XL1 for the nth time series |

| λn | degradation probability of the nth time series |

| probability density function | |

| MEM | maximum entropy method |

| PCP | Poisson counting principle |

| MEPCM | maximum entropy Poisson counting method |

References

- Chen, S.A.; Cai, J.L.; Xiang, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Fillon, M. Tribo-dynamic-wear coupling analysis for water-lubricated bearings with journal surface imperfection under repeated start-stop cycles. Tribol. Int. 2024, 200, 110093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.L.; Ouyang, W.; Li, R.Q.; Jin, Y.; He, T. Experimental research on lubrication and vibration characteristics of water-lubricated stern bearing for underwater vehicles under extreme working conditions. Wear 2023, 523, 204778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IACS. Economic Impact of Marine Equipment Failures 2023; IACS: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Karatug, C.; Ceylan, B.O.; Ceylan, B.O. A hybrid predictive maintenance approach for ship machinery systems: A case of main engine bearings. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 24, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, G.; Tang, G. Long short-term memory network with multi-resolution singular value decomposition for prediction of bearing performance degradation. Measurement 2020, 156, 107582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, R.; Ikizoglu, S.; Seker, S. Statistical Wiener process model for vibration signals in accelerated aging processes of electric motors. J. Vibroeng. 2014, 16, 800–807. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Tsui, K.-L. Statistical modeling of bearing degradation signals. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2017, 66, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.A. Rolling Bearing Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hidle, E.L.; Hestmo, R.H.; Adsen, O.S.; Lange, H.; Vinogradov, A. Early detection of subsurface fatigue cracks in rolling element bearings by the knowledge-based analysis of acoustic emission. Sensors 2022, 22, 5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.W.; Benson, S.; Wetenhall, B. Comparative analysis of fatigue life of a wind turbine yaw bearing with different support foundations. Ocean Eng. 2021, 235, 109293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ying, L.X.; Nie, C.Y.; Zhu, T.; Tang, R.; Liu, R. Investigation of the corrosion-wear interaction behavior of 8cr4mo4v bearing steel at various corrosion intervals. Coatings 2024, 14, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Gao, H.L.; Zhang, J.Q. Bearing Remaining useful life prediction based on a nonlinear wiener process model. Shock Vib. 2018, 2018, 4068431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zhu, D.; Yu, C.J.; Wang, Q.J. Mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication model for finite roller-coated half ctmck for space interfaces. Tribol. Int. 2019, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landen, E.W. Slow speed wear of steel surfaces lubricated by thin oil films. Tribol. T. 1968, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. A bearing fault diagnosis method based on a residual network and a gated recurrent unit under time-varying working conditions. Sensors 2023, 23, 6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, D.; Antoni, J.; Sieg-Zieba, S.; Eltabach, M. Envelope analysis of rotating machine vibrations in variable speed conditions: A comprehensive treatment. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 84, 200–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matania, O.; Heletz, S.; Klein, R.; Groper, M.; Bortman, J. Toward diagnostics of water-lubricated bearings of naval vessels by vibration analysis. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 2565–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, Y.T.; Hu, Y.F.; Xiang, S.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, D.; Liang, Y. MCI-GRU: Stock prediction model based on multi-head cross-attention and improved GRU. Neurocomputing 2025, 638, 130168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Hu, Y.S.; Deng, S.E.; Zhang, W.; Cui, Y.; Xu, J. A novel model for evaluating the operation performance status of rolling bearings based on hierarchical maximum entropy bayesian method. Lubricants 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Zhou, W.H.; Dong, D.F.; Wang, Z. Estimation of random vibration signals with small samples using bootstrap maximum entropy method. Measurement 2017, 105, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.T.; Meng, Y.Y.; Qiu, M. Forecasting for variation process of reliability of rolling bearing vibration performance using grey bootstrap Poisson method. J. Mech. Eng. 2015, 51, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Zhang, W.H.; Cui, Y.C.; Deng, S. Dynamic evaluation of the degradation process of vibration performance for machine tool spindle bearings. Sensors 2023, 23, 5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Zhou, S.Y. Statistical process monitoring based on maximum entropy density approximation and level set principle. IIE Trans. 2015, 3, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.F.; Guo, K.; Yuan, X.X.; Fu, W.; Xun, Z. Wavelet Denoising of Well Logs and its Geological Performance. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2010, 28, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiakojouri, A.; Lu, Z.D.; Mirring, P.; Powrie, H.; Wang, L. A novel hybrid technique combining improved cepstrum pre-whitening and high-pass filtering for effective bearing fault diagnosis using vibration data. Sensors 2023, 23, 9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.L.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.Q.; Jiang, H. Remaining useful life prediction of rolling element bearings based on simulated performance degradation dictionary. Mech. Mach. Theory 2020, 153, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).