Optimizing Cutting Fluid Use via Machine Learning in Smart Manufacturing for Enhanced Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Material

2.3. Cutting Tool

2.4. Cutting Fluid

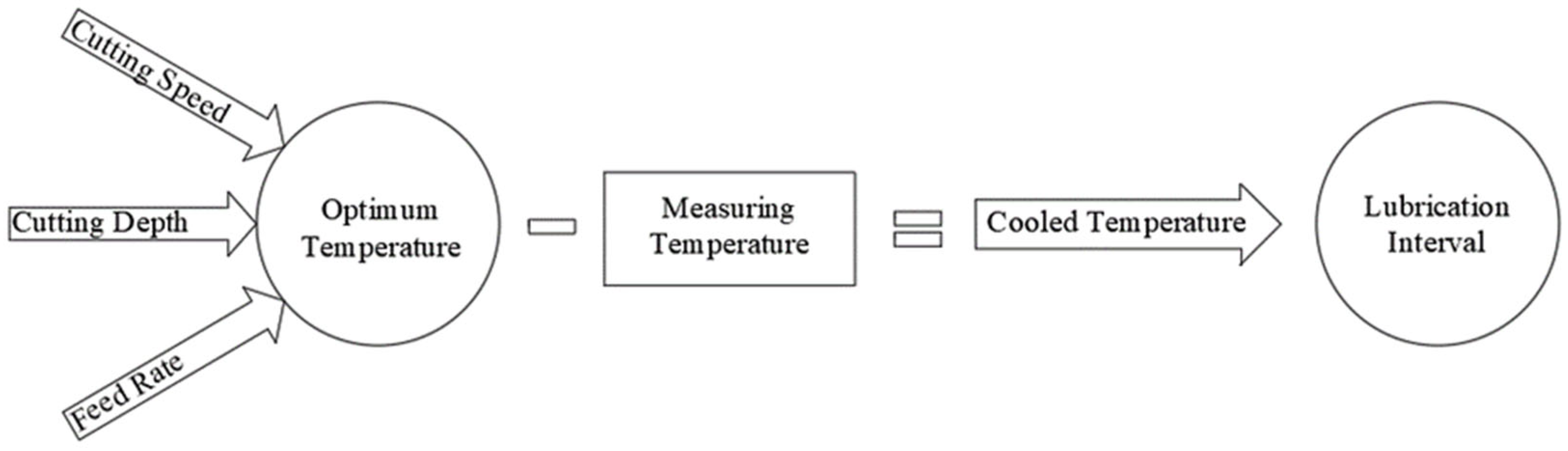

2.5. Machine Learning Procedures

3. Results

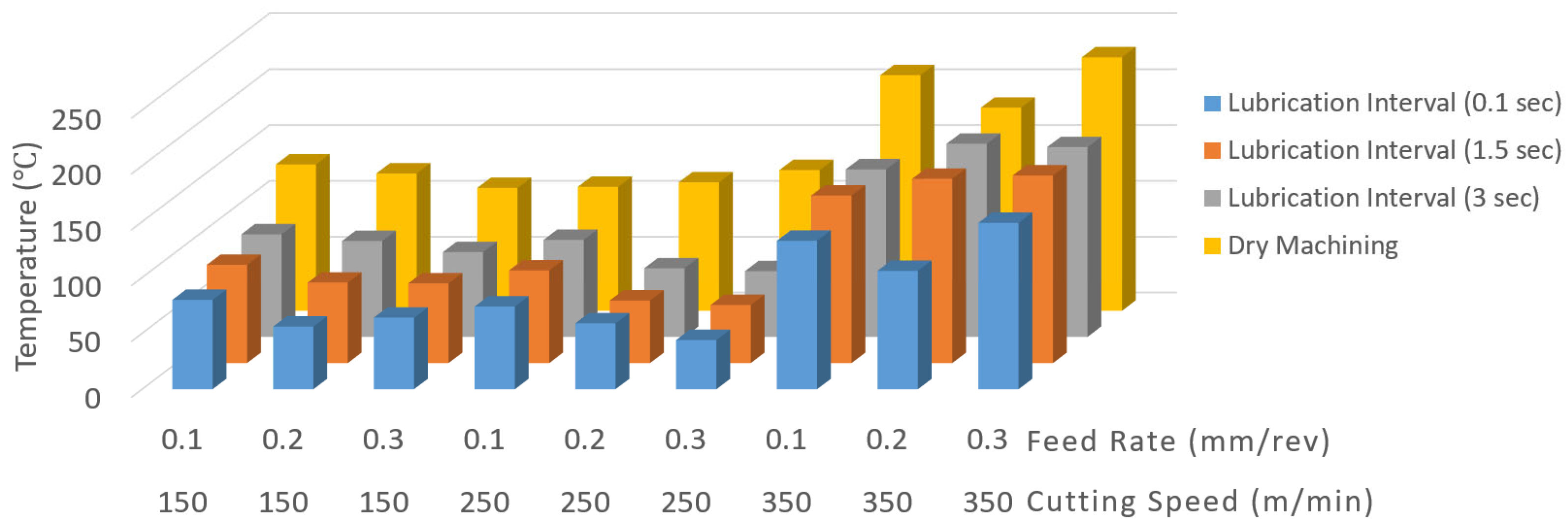

3.1. Experimental Observations

3.2. Machine Learning Model Performance

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Cooling Strategies

3.4. Environmental Evaluation

4. Conclusions

- The proposed system enables machining at the optimum temperature, eliminating the need for high-temperature cutting. This reduces tool wear, extends tool life, and improves the surface quality of the workpiece.

- The most important feature of the system is its ability to prevent both excessive and unnecessary cooling. When the temperature difference between the measured and optimum machining temperature is below 0 °C, the system automatically stops cooling, thereby avoiding energy loss and unnecessary coolant use.

- Maintaining the optimum temperature also allows higher cutting speeds, feed rates, and depths of cut, increasing process efficiency without reducing tool life.

- Although all three models exhibited comparable error levels, the Random Forest Regression model consistently delivered the lowest RMSE and the most reliable temperature-to-lubrication interval mapping, indicating that it offers the highest practical utility for the implementation of the automatic cooling system.

- Comparative analysis shows that the developed system saves 22.5 mL of coolant per minute compared with conventional cooling and 2.5 mL per minute compared with MQL. These savings provide both environmental and economic advantages.

- The system supports sustainable production by reducing coolant consumption, water use, and energy demand, achieving an estimated annual reduction of about 12.3 T of CO2 emissions.

- By minimizing the amount of coolant used, the system helps limit the environmental and health effects commonly associated with cutting fluids.

- The integration of machine learning enables automatic adjustment of lubrication intervals, reducing the need for operator intervention and contributing to more reliable manufacturing processes.

- Future studies should expand the dataset and include a wider range of machining parameters such as tool geometry, material type, and cutting fluid composition to improve model accuracy.

- Further experimental work and life-cycle assessment (LCA) studies are recommended to evaluate the environmental benefits of the system in greater detail.

- Challenges encountered in this study included the limited amount of experimental data available for training and validating the machine learning models, fluctuations in temperature measurements due to sensor response time, and the difficulty of maintaining stable cutting conditions during long-duration tests. Additionally, balancing model complexity with interpretability and ensuring consistent coolant delivery under dynamic operating conditions posed practical difficulties. These challenges provided valuable insights for refining the system design and improving the robustness of the predictive models in future work.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chetan, N.; Narasimhulu, A.; Ghosh, S.; Rao, P.V. Application of sustainable techniques in metal cutting for enhanced machinability: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 100, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junankar, A.A.; Purohit, J.K.; Sayed, A.R. Minimum Quantity Lubrication System for Metal-Cutting Process: Sustainable Manufacturing Process. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 5264–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Dong, Z.; Yuan, S.; Bao, Y.; Kang, R. Effects of Cutting Force on Formation of Subsurface Damage During Nano-Cutting of Single-Crystal Tungsten. ASME. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Novemb. 2022, 144, 111008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Mia, M.; Pruncu, C.I.; Kapłonek, W.; Nadolny, K.; Patra, K.; Mikolajczyk, T.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Sarikaya, M.; Sharma, V.S. Parametric optimization and process capability analysis for machining of nickel-based superalloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 3995–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolczyk, G.M.; Maruda, R.W.; Krolczyk, J.B.; Wojciechowski, S.; Mia, M.; Nieslony, P.; Budzik, G. Ecological trends in machining as a key factor in sustainable production—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addona, D.M.; Di Nardo, A. Feasibility study of using microorganisms as lubricant component in cutting fluids. Procedia CIRP 2020, 88, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbededo, M.A.; Liyanage, K.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. The analysis of key technologies for sustainable machine tools design. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.; Hurtado Carreon, A.; DePaiva, J.M.; Veldhuis, S.C. Influence of Cutting Parameters and MQL on Surface Finish and Work Hardening of Inconel 617. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, F. Investigation of the effect of Al2O3 nanoparticle-added MQL lubricant on sustainable and clean manufacturing. Lubricants 2024, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, O. Tornalamada kriyojenik soğutma ve minimum miktarda yağlamanın kesici takım aşınması ve titreşimine etkilerinin araştırılması. Ph.D. Thesis, Düzce University, Düzce, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, A.R.; Silva, L.R.R.; Pimenov, Y.D.; Souza, F.C.R.; Kuntoğlu, M.; Paiva, R.L. Comprehensive review of advanced methods for improving the parameters of machining steels. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 125, 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.; Tariq, J.B.; Morshed, S.M.; Shawon, S.H.; Hasan, A.; Prakash, C.; Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Nirsanametla, Y.; Pruncu, C.I. Environmental, Economical and Technological Analysis of MQL-Assisted Machining of Al-Mg-Zr Alloy Using PCD Tool. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, R. A review on cutting fluids used in machining processes. Eng. Res. Express 2021, 3, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C. State-of-the-art on minimum quantity lubrication in green machining. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhanapu, M.; Chaganti, P.K.; Tarigopula, P. Characterization and machine learning-based parameter estimation in MQL machining of a superalloy for developed green nano-metalworking fluids. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.S.; To, S. A review: Insight into smart and sustainable ultra-precision machining augmented by intelligent IoT. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, P.K.; Sahai, R.S.N. Sustainable machining of AISI4140 steel: A Taguchi-ANN perspective on eco-friendly metal cutting parameters. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2024, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Ross, N.S.; Sheeba, P.T.; Shibi, C.S.; Korkmaz, M.E.; Sharma, V.S. A novel approach of tool condition monitoring in sustainable machining of Ni alloy with transfer learning models. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Królczyk, G.M.; Sharma, V.S.; Korkmaz, M.E.; Yılmaz, H.; Şirin, Ş. Real-time monitoring and measurement of energy characteristics in sustainable machining of titanium alloys. Measurement 2024, 224, 113937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preez, A.; Afonso, P. Machine learning in cutting processes as enabler for smart sustainable manufacturing. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 33, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.; Razi, M.H.; Ahmad, I.; Mostafa, R.; Rahman, S.M.S.; Dhar, N.R. Predictive modeling of turning operations under different cooling-lubricating conditions for sustainable manufacturing with machine learning techniques. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 20, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paturi, U.M.R.; Cheruku, S. Application and performance of machine learning techniques in manufacturing sector from the past two decades: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 38, 2392–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Hynes, N.R.J.; Kumar, J.S.; Sujana, J.A.J. Random decision forest based sustainable green machining using Citrullus lanatus extract as bio-cutting fluid. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 68, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillinger, M.; Diestel, O. Energy prediction for CNC machining with machine learning. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, K.; Anjum, I.; Pruncu, C.I.; Amjad, M.; Kumar, M.S.; Maqsood, M.A. Progressing towards sustainable machining of steels: A detailed review. Materials 2021, 14, 5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, V.; Sharma, A.K.; Pimenov, D.Y. Prediction of surface roughness using machine learning approach in MQL turning of AISI 304 steel by varying nanoparticle size in the cutting fluid. Lubricants 2022, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeem, R.A.; Fadare, D.A.; Ikumapayi, O.M.; Adediran, A.A.; Aliyu, S.J.; Akinlabi, S.A.; Jen, T.-C.; Akinlabi, E.T. Advances in the application of vegetable-oil-based cutting fluids to sustainable machining operations—A review. Lubricants 2022, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outeiro, J.; Cheng, W.; Chinesta, F.; Ammar, A. Modelling and optimization of machining of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy using machine learning and design of experiments methods. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıkaya, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Tomaz, I.; Krolczyk, G. Resource savings by sustainability assessment and energy modelling methods in mechanical machining process: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagan, S.C.; Leksycki, K. Analysis of surface roughness after ball burnishing of pure titanium under environmentally friendly conditions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Multi-objective optimisation of machining process parameters using deep learning-based data-driven genetic algorithm and TOPSIS. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.; Hegab, H.; Rahnamayan, S.; Kishawy, H.A. Multi-objective optimization and innovization-based knowledge discovery of sustainable machining process. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Di, Y. Thematic analysis of sustainable ultra-precision machining by using text mining and unsupervised learning method. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.E.; Gupta, M.K.; Niesłony, P.; Sarikaya, M.; Kuntoğlu, M. Implementation of green cooling-lubrication strategies in metal cutting industries: A state of the art towards sustainable future and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 123, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.E.; Gupta, M.K.; Kuntoğlu, M.; Patange, A.D.; Ross, N.S.; Yılmaz, H.; Vashishtha, G. Prediction and classification of tool wear and its state in sustainable machining of Bohler steel with different machine learning models. Measurement 2023, 223, 113825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walk, J.; Kühl, N.; Saidani, M.; Schatte, J. Artificial intelligence for sustainability: Facilitating sustainable smart product-service systems with computer vision. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.U.; Kumar, R.; Khan, A.; Singh, J.; Anwar, S.; Haber, R. Sustainable machining of Inconel 718 using minimum quantity lubrication: Artificial intelligence-based process modelling. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 310, 127463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Meurer, M.; Bergs, T. Modeling and Monitoring of the Tool Temperature During Continuous and Interrupted Turning with Cutting Fluid. Metals 2024, 14, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichosz, P.; Karolczak, P.; Waszczuk, K. Review of cutting temperature measurement methods. Materials 2023, 16, 6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurina, F.; Peterka, J.; Vozar, M.; Patoprsty, B.; Vopat, T. Design of real-time monitoring system for cutting fluids. Designs 2023, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Yu, C.; Lin, K.; Lu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Fu, G. A review of machine learning-based thermal error modeling methods for CNC machine tools. Machines 2025, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghoolizadeh, M.; Nasajpour-Esfahani, N.; Pirmoradian, M.; Toghraie, D. Using different machine learning algorithms to predict the rheological behavior of oil SAE40-based nano-lubricant in the presence of MWCNT and MgO nanoparticles. Tribol. Int. 2023, 187, 108759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, R.; Verma, S.; Rafighi, M. Review of lubrication and cooling in computer numerical control (CNC) machine tools: A content and visualization analysis, research hotspots and gaps. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, R.; Gamage, J.; Karunathilake, H. Sustainable machining: Environmental performance analysis of turning. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2022, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, H.; Desmira, N.; Fujimoto, H. Environmental Burden Analysis for Machining Operation Using LCA Method. In Manufacturing Systems and Technologies for the New Frontier; Mitsuishi, M., Ueda, K., Kimura, F., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIVM Report 2016-0104. ReCiPe 2016, A Harmonized Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method at Midpoint and Endpoint Level. Report I: Characterization. National Institute for Public Healthand the Environment of Netherlands. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/2016-0104.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; Van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A harmonized life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exp. No | Vc (m/min) | f (mm/rev) | ap (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 250 | 0.2 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 350 | 0.3 | 1 |

| Property Type | Characteristic | Value/Range (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| I. Chemical Composition | Carbon (C) | 0.14−0.19% |

| Manganese (Mn) | 1.00−1.30% | |

| Chromium (Cr) | 0.80−1.10% | |

| Silicon (Si) | ≤0.40% | |

| Phosphorus (P) | ≤0.025% | |

| Sulfur (S) | ≤0.035% | |

| II. Mechanical Properties | Tensile Strength (Rm) | 800−1100 MPa |

| Yield Strength (Rp0.2) | ≥600 MPa | |

| Hardness | ≤207 HBW | |

| Elongation (A) | ≥21% (Soft Annealed) | |

| III. Physical Properties | Density | 7.85 g/cm3 |

| Modulus of Elasticity (E) | ≈210 GPa | |

| Thermal Conductivity | ≈41 W/(m⋅K) | |

| Key Application | Gears, Shafts, Pinions, Pins |

| Property | Value/Range |

|---|---|

| Color (Concentrate) | Light yellow to amber |

| Color (Working Solution) | Opaque white |

| Odor (Concentrate) | Mild amine |

| Form (Concentrate) | Liquid |

| Flash Point (Concentrate) (ASTM D93-08) | >212 °F |

| pH (Concentrate as Range) | 8.7–9.7 |

| pH (Typical Operating as Range) | 9.3–10.3 |

| Coolant Refractometer Factor | 1.0 |

| Titration Factor (CGF-1 Titration Kit) | 1.22 |

| Digital Titration Factor | 380 |

| V.O.C. Content (ASTM E1868-10) | 8 g/l |

| Model | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| Random Forest Regression (RFR) | n_estimators = 100; max_depth = None; min_samples_split = 2; min_samples_leaf = 1; random_state = 10 |

| KNN Regression (KNNR) | k = 3; metric = Minkowski (p = 2); weights = uniform |

| LASSO Regression | alpha = 1; max_iter = 10,000 |

| Cutting Speed (m/min) | Cutting Depth (mm) | Feed Rate (mm/rev) | Dry Machining- Temp. (°C) | Lubrication Interval (0.1 s) Temp. (°C) | Lubrication Interval (1.5 s) Temp. (°C) | Lubrication Interval (3 s) Temp. (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 131 | 80 | 88 | 92 |

| 2 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.1 | 188 | 103 | 123 | 179 |

| 3 | 150 | 1 | 0.1 | 214 | 112 | 154 | 197 |

| 4 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 123 | 56 | 72 | 86 |

| 5 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 176 | 73 | 80 | 96 |

| 6 | 150 | 1 | 0.2 | 184 | 84 | 88 | 97 |

| 7 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 110 | 64 | 71.4 | 76 |

| 8 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 244 | 58 | 70 | 72 |

| 9 | 150 | 1 | 0.3 | 200 | 74 | 76 | 83,4 |

| 10 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 111 | 74 | 83 | 87 |

| 11 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.1 | 142 | 106 | 130 | 135 |

| 12 | 250 | 1 | 0.1 | 218 | 87 | 123 | 141 |

| 13 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 115 | 58.9 | 56 | 61.5 |

| 14 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 132 | 56 | 59.8 | 67 |

| 15 | 250 | 1 | 0.2 | 120 | 63 | 74 | 87 |

| 16 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 126 | 44 | 52 | 59 |

| 17 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 205 | 48.9 | 52 | 58.2 |

| 18 | 250 | 1 | 0.3 | 258 | 68.7 | 70 | 76 |

| 19 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 211 | 133 | 150 | 150 |

| 20 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.1 | 346 | 114 | 175 | 240 |

| 21 | 350 | 1 | 0.1 | 258 | 230 | 238 | 233 |

| 22 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 182 | 106 | 165 | 173 |

| 23 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 245 | 116 | 134 | 188 |

| 24 | 350 | 1 | 0.2 | 189 | 171 | 172 | 180 |

| 25 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 227 | 149 | 168 | 170 |

| 26 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 284 | 189 | 218 | 269 |

| 27 | 350 | 1 | 0.3 | 296 | 106 | 258 | 292 |

| Cutting Variables | Required Cooling | Cooling Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutting Speed (m/min) | Cutting Depth (mm) | Feed Rate (mm/rev) | Dry Machining Control Deviation (°C) | Lubrication Interval (0.1 s) Control Deviation (°C) | Lubrication Interval (1.5 s) Control Deviation (°C) | Lubrication Interval (3 s) Control Deviation (°C) | |

| 1 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.1 | −19 | −70 | −62 | −58 |

| 2 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.1 | 38 | −47 | −27 | 29 |

| 3 | 150 | 1 | 0.1 | 64 | −38 | 4 | 47 |

| 4 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.2 | −27 | −94 | −78 | −64 |

| 5 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 26 | −77 | −70 | −54 |

| 6 | 150 | 1 | 0.2 | 34 | −66 | −62 | −53 |

| 7 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.3 | −40 | −86 | −78.6 | −74 |

| 8 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 94 | −92 | −80 | −78 |

| 9 | 150 | 1 | 0.3 | 50 | −76 | −74 | −66.6 |

| 10 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.1 | −39 | −76 | −67 | −63 |

| 11 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.1 | −8 | −44 | −20 | −15 |

| 12 | 250 | 1 | 0.1 | 68 | −63 | −27 | −9 |

| 13 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.2 | −35 | −91.1 | −94 | −88.5 |

| 14 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.2 | −18 | −94 | −90.2 | −83 |

| 15 | 250 | 1 | 0.2 | −30 | −87 | −76 | −63 |

| 16 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.3 | −24 | −106 | −98 | −91 |

| 17 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 55 | −101.1 | −98 | −91.8 |

| 18 | 250 | 1 | 0.3 | 108 | −81.3 | −80 | −74 |

| 19 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 61 | −17 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.1 | 196 | −36 | 25 | 90 |

| 21 | 350 | 1 | 0.1 | 108 | 80 | 88 | 83 |

| 22 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 32 | −44 | 15 | 23 |

| 23 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 95 | −34 | −16 | 38 |

| 24 | 350 | 1 | 0.2 | 39 | 21 | 22 | 30 |

| 25 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 77 | −1 | 18 | 20 |

| 26 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 134 | 39 | 68 | 119 |

| 27 | 350 | 1 | 0.3 | 146 | −44 | 108 | 142 |

| Cutting Variables | Required Cooling | Lubrication Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutting Speed (m/min) | Cutting Depth (mm) | Feed Rate (mm/rev) | Dry Machining Control Deviation (°C) | Estimated Lubrication Interval (s) RFR | Estimated Lubrication Interval (s) KNNR | Estimated Lubrication Interval (s) LASSO | |

| 1 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.1 | −19 | No need | No need | No need |

| 2 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.1 | 38 | 0.1875 | 1.0666 | 1.321 |

| 3 | 150 | 1 | 0.1 | 64 | 0.44 | 1.0666 | 1.530 |

| 4 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.2 | −27 | No need | No need | No need |

| 5 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 26 | 0.2225 | 1.0666 | 1.225 |

| 6 | 150 | 1 | 0.2 | 34 | 0.24 | 1.0666 | 1.7088 |

| 7 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.3 | −40 | No need | No need | No need |

| 8 | 150 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 94 | 2.7587 | 1.0666 | 1.771 |

| 9 | 150 | 1 | 0.3 | 50 | 0.3112 | 1.0666 | 1418 |

| 10 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.1 | −39 | No need | No need | No need |

| 11 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.1 | −8 | No need | No need | No need |

| 12 | 250 | 1 | 0.1 | 68 | 0.6212 | 2.0333 | 1.166 |

| 13 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.2 | −35 | No need | No need | No need |

| 14 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.2 | −18 | No need | No need | No need |

| 15 | 250 | 1 | 0.2 | −30 | No need | No need | No need |

| 16 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.3 | −24 | No need | No need | No need |

| 17 | 250 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 55 | 0.6962 | 2.0333 | 1.062 |

| 18 | 250 | 1 | 0.3 | 108 | 1.3462 | 2.5000 | 1.487 |

| 19 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 61 | 1.3062 | 1.0666 | 0.714 |

| 20 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.1 | 196 | 1.4237 | 1.5333 | 1.797 |

| 21 | 350 | 1 | 0.1 | 108 | 0.19 | 0.5666 | 1.091 |

| 22 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 32 | 0.505 | 1.0666 | 0.481 |

| 23 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 95 | 1.69 | 0.5666 | 0.9871 |

| 24 | 350 | 1 | 0.2 | 39 | 0.2225 | 1.0666 | 0.537 |

| 25 | 350 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 77 | 1.4487 | 0.5666 | 0.842 |

| 26 | 350 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 134 | 0.8575 | 0.5666 | 1.300 |

| 27 | 350 | 1 | 0.3 | 146 | 0.78325 | 1.5333 | 1.396 |

| Component | Description | Annual CO2 Savings (kg) | Annual CO2 Savings (tons) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutting fluid production + Disposal | 1.35 L/h × 4.251 kg-CO2/L × 8 h/day × 250 days/year | 11,478 | 11.48 |

| Water usage reduction | Based on 95% water content in cutting fluid | 484.7 | 0.485 |

| Electricity savings | Assuming 0.4 kWh/hour reduction in power consumption | 304.75 | 0.305 |

| TOTAL | 12,267.45 | 12.27 |

| System | Cutting Fluid Usage (L/h) | Water Content (L/h) | Electricity Use (kWh/h) | Total CO2 Emission (kg/h) | CO2 Breakdown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | 1.5 | 1.425 (95%) | 1.2 | 21.56 | Fluid prod. and disposal: 6.38 + 7.73 = 14.11 kg Water: 1.425 × 0.189 = 0.27 kg Electricity: 1.2 × 0.381 = 0.457 kg |

| MQL | 0.2 | 0.1425 (95%) | 1.0 | 3.76 | Fluid: 0.85 + 1.03 = 1.88 kg Water: 0.036 kg Electricity: 0.381 kg |

| Innovative | 0.15 | 0.1425 (95%) | 0.8 | 2.94 | Fluid: 0.638 + 0.77 = 1.41 kg Water: 0.027 kg Electricity: 0.305 kg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özdüzgün, H.S.; Er, A.O. Optimizing Cutting Fluid Use via Machine Learning in Smart Manufacturing for Enhanced Sustainability. Lubricants 2025, 13, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120519

Özdüzgün HS, Er AO. Optimizing Cutting Fluid Use via Machine Learning in Smart Manufacturing for Enhanced Sustainability. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120519

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzdüzgün, Halit Süleyman, and Ali Osman Er. 2025. "Optimizing Cutting Fluid Use via Machine Learning in Smart Manufacturing for Enhanced Sustainability" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120519

APA StyleÖzdüzgün, H. S., & Er, A. O. (2025). Optimizing Cutting Fluid Use via Machine Learning in Smart Manufacturing for Enhanced Sustainability. Lubricants, 13(12), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120519