A New Generation of Eco-Designed Embolic Agents: Towards Sustainable and Personalized Interventional Radiology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Preparation

2.2. Laparotomy and Splenic Preparation

2.3. Endovascular Preparation

2.4. Splenic Injury and Embolization

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Homogeneity and Hemorrhagic Model Validation

3.2. Embolization Procedure

3.3. Blood Loss

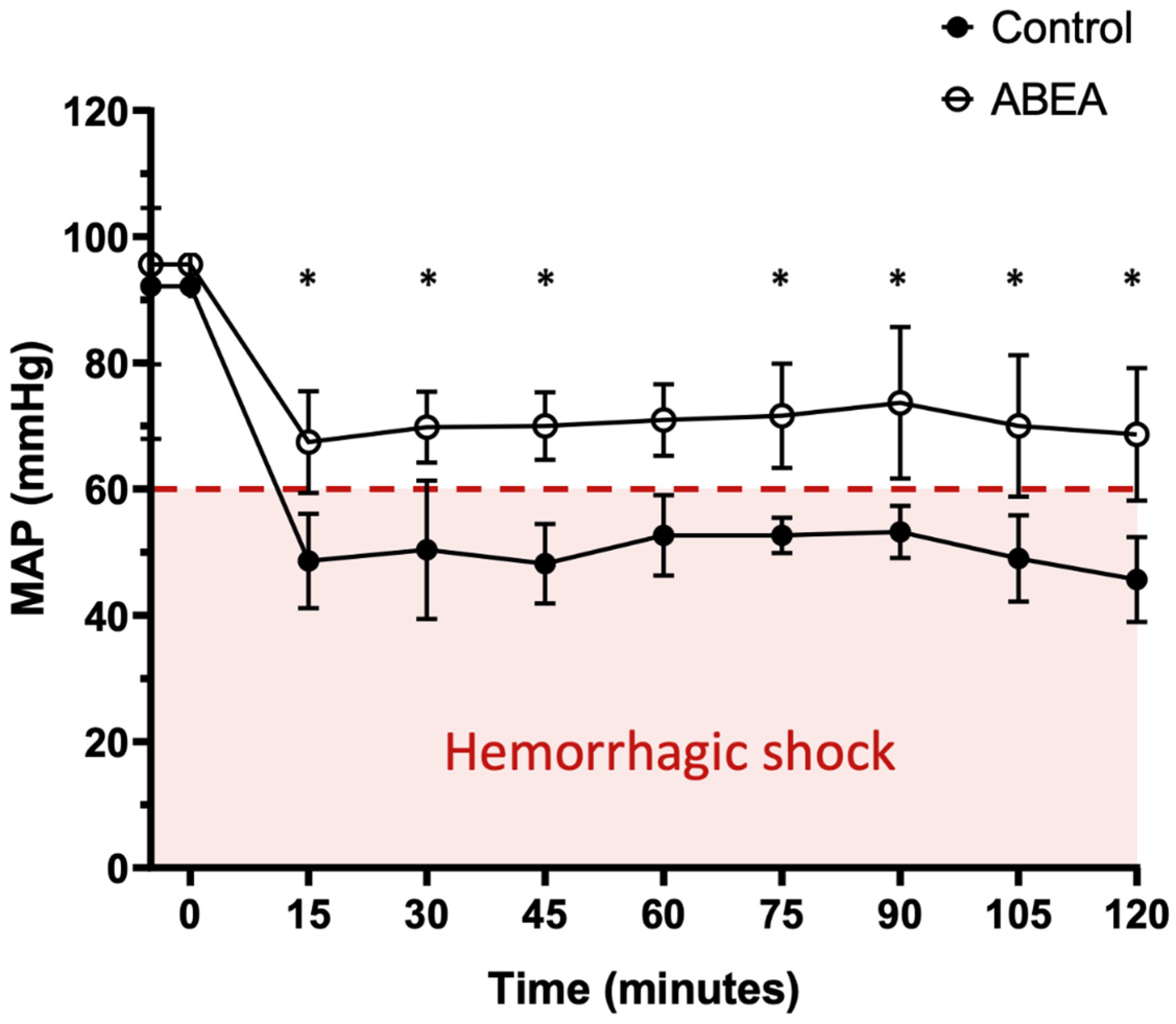

3.4. Blood Pressure

3.5. Cardiac Frequency

3.6. Post-Mortem Macroscopic Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABEA | Agar Based Embolization Agent |

| IR | Interventional Radiology |

References

- Baum, R.A.; Baum, S. Interventional Radiology: A Half Century of Innovation. Radiology 2014, 273, S75–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teuben, M.; Spijkerman, R.; Pfeifer, R.; Blokhuis, T.; Huige, J.; Pape, H.-C.; Leenen, L. Selective Non-Operative Management for Penetrating Splenic Trauma: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 2019, 45, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimbanassi, S.; Chiara, O.; Leppaniemi, A.; Henry, S.; Scalea, T.M.; Shanmuganathan, K.; Biffl, W.; Catena, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Tugnoli, G.; et al. Nonoperative Management of Abdominal Solid-Organ Injuries Following Blunt Trauma in Adults: Results from an International Consensus Conference. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2018, 84, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Blanzy, J.; Gómez, K.J.R.; Preul, M.C.; Vernon, B.L. Liquid Embolic Agents for Endovascular Embolization: A Review. Gels 2023, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyon, J.J.; Littlehales, T.; Rangarajan, B.; Hoey, E.T.; Ganeshan, A. Endovascular Embolization: Review of Currently Available Embolization Agents. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2014, 43, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Albadawi, H.; Chong, B.W.; Deipolyi, A.R.; Sheth, R.A.; Khademhosseini, A.; Oklu, R. Advances in Biomaterials and Technologies for Vascular Embolization. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopera, J. Embolization in Trauma: Principles and Techniques. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2010, 27, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agripnidis, T.; Ruimy, A.; Panneau, J.; Nguyen, J.; Nail, V.; Tradi, F.; Marx, T.; Haffner, A.; Brige, P.; Haumont, R.; et al. In Vivo Feasibility of Arterial Embolization with a New Permanent Agar–Agar-Based Agent. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 48, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauvar, D.S.; Schechtman, D.W.; Thomas, S.B.; Polykratis, I.A.; De Guzman, R.; Prince, M.D.; Voelker, A.; Kheirabadi, B.S.; Dubick, M.A. Endovascular Embolization Techniques in a Novel Swine Model of Fatal Uncontrolled Solid Organ Hemorrhage and Coagulopathy. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 70, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauvar, D.S.; Polykratis, I.A.; De Guzman, R.; Prince, M.D.; Voelker, A.; Kheirabadi, B.S.; Dubick, M.A. Evaluation of a Novel Hydrogel Intravascular Embolization Agent in a Swine Model of Fatal Uncontrolled Solid Organ Hemorrhage and Coagulopathy. JVS-Vasc. Sci. 2021, 2, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondeen, J.L.; Prince, M.D.; Kheirabadi, B.S.; Wade, C.E.; Polykratis, I.A.; De Guzman, R.; Dubick, M.A. Initial Resuscitation with Plasma and Other Blood Components Reduced Bleeding Compared to Hetastarch in Anesthetized Swine with Uncontrolled Splenic Hemorrhage. Transfusion 2011, 51, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siskin, G. In Vivo Feasibility of Arterial Embolization with a New Permanent Agar–Agar-Based Agent: Cause for Excitement and Restraint. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 48, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beni, B.H.; Falahati, M.; Rostamabadi, M.M.; Navid, S.; Rostamabadi, H. Agar as a Natural Polymer: From Culture Media to Cutting-Edge Biomedical Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 368, 124100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, M.; Di-Rocco, C.; Panneau, J.; Nguyen, J.; Marx, T.; Haumont, R.; Brige, P.; Guillet, B.; Tradi, F.; Vidal, V. Additional In Vivo Study of Arterial Embolization with a Novel Agar-Based Embolic Agent: Feasibility and Efficacy of New-Size Implants for Improved Microcatheter Injectability. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 49, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novy, E.; Levy, B. Choc hémorragique: Aspects physiopathologiques et prise en charge hémodynamique. Réanimation 2015, 24, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruimy, A.; Agripnidis, T.; Panneau, J.; Nguyen, J.; Tradi, F.; Marx, T.; Haumont, R.; Brige, P.; Guillet, B.; Vidal, V. A New Generation of Eco-Designed Embolic Agents: Towards Sustainable and Personalized Interventional Radiology. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020064

Ruimy A, Agripnidis T, Panneau J, Nguyen J, Tradi F, Marx T, Haumont R, Brige P, Guillet B, Vidal V. A New Generation of Eco-Designed Embolic Agents: Towards Sustainable and Personalized Interventional Radiology. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(2):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020064

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuimy, Alexis, Thibault Agripnidis, Julien Panneau, Johanna Nguyen, Farouk Tradi, Thierry Marx, Raphaël Haumont, Pauline Brige, Benjamin Guillet, and Vincent Vidal. 2026. "A New Generation of Eco-Designed Embolic Agents: Towards Sustainable and Personalized Interventional Radiology" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 2: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020064

APA StyleRuimy, A., Agripnidis, T., Panneau, J., Nguyen, J., Tradi, F., Marx, T., Haumont, R., Brige, P., Guillet, B., & Vidal, V. (2026). A New Generation of Eco-Designed Embolic Agents: Towards Sustainable and Personalized Interventional Radiology. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(2), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020064