Factors Associated with Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis (D2T-RA): Real-World Evidence from a Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Study Design

2.4. Collected Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nagy, G.; Roodenrijs, N.M.T.; Welsing, P.M.J.; Kedves, M.; Hamar, A.; Van Der Goes, M.C.; Kent, A.; Bakkers, M.; Blaas, E.; Senolt, L.; et al. EULAR definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodenrijs, N.M.T.; De Hair, M.J.H.; Van Der Goes, M.C.; Jacobs, J.W.G.; Welsing, P.M.J.; Van Der Heijde, D.; van Laar, J.; Nagy, G. Characteristics of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: Results of an international survey. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 1705–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hair, M.J.H.; Jacobs, J.W.G.; Schoneveld, J.L.M.; Van Laar, J.M. Difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: An area of unmet clinical need. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, R.; Hashimoto, M.; Murata, K.; Murakami, K.; Tanaka, M.; Ohmura, K.; Tanaka, M.; Ohmura, K.; Ito, H.; Matsuda, S. Prevalence and predictive factors of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: The KURAMA cohort. Immunol. Med. 2022, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batko, B.; Urbański, K.; Świerkot, J.; Wiland, P.; Raciborski, F.; Jędrzejewski, M.; Koziej, M.; Cześnikiewicz-Guzik, M.; Guzik, T.J.; Stajszczyk, M. Comorbidity burden and clinical characteristics of patients with difficult-to-control rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roodenrijs, N.M.T.; Welsing, P.M.J.; Van Roon, J.; Schoneveld, J.L.M.; Van Der Goes, M.C.; Nagy, G.; Townsend, M.J.; van Laar, J.M. Mechanisms underlying DMARD inefficacy in difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: A narrative review with systematic literature search. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 3552–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giollo, A.; Zen, M.; Larosa, M.; Astorri, D.; Salvato, M.; Calligaro, A.; Botsios, L.; Bernardi, C.; Bianchi, G.; Doria, A. Early characterization of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis by suboptimal initial management: A multicentre cohort study. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 2083–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodenrijs, N.M.T.; Kedves, M.; Hamar, A.; Nagy, G.; Van Laar, J.M.; Van Der Heijde, D.; Welsing, P.M. Diagnostic issues in difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open 2021, 7, e001511. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, N.; Barone, E.; Timilsina, S.; Gershwin, M.E.; Selmi, C. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors and cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 65, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Nagy, G.; Nikiphorou, E. Comorbidities or extra-articular manifestations: Time to reconsider the terminology? Rheumatology 2022, 61, 3881–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messelink, M.A.; Roodenrijs, N.M.T.; van Es, B.; Hulsbergen-Veelken, C.A.R.; Jong, S.; Overmars, L.M.; Reteig, L.C.; Tan, S.C.; Tauber, T.; van Laar, J.M.; et al. Identification and prediction of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis patients in structured and unstructured routine care data. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecquet, S.; Combier, A.; Steelandt, A.; Pons, M.; Wendling, D.; Molto, A.; Miceli-Richard, C.; Allanore, Y.; Avouac, J. Characteristics of patients with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis in a French single-centre hospital. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 3866–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novella-Navarro, M.; Plasencia, C.; Tornero, C.; Navarro-Compán, V.; Cabrera-Alarcón, J.L.; Peiteado-López, D.; Nuño, L.; Monjo-Henry, I.; Franco-Gómez, K.; Villalba, A.; et al. Clinical predictors of multiple failure to biological therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Benucci, M.; Gobbi, F.L.; Cassarà, E.A.M.; Marigliano, A.L.; Mannoni, A.; Benvenuti, E. Single-center cross-sectional analysis of patients with RA, SpA, and PsA: Data from the prescription database. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Birnbaum, N.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An ACR/EULAR collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, R.; Okano, T.; Gon, T.; Yoshida, N.; Fukumoto, K.; Yamada, S.; Hashimoto, M. Difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: Current concept and unsolved problems. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1049875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanashi, S.; Kaneko, Y. Unmet needs and current challenges of rheumatoid arthritis: Difficult-to-treat and late-onset RA. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, Y.; Beran, A.; Ghazaleh, S.; Lee-Smith, W.; Altorok, N. Predictors of remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with biologics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 41, 3615–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawaheer, D.; Maranian, P.; Park, G.; Lahiff, M.; Amjadi, S.S.; Paulus, H.E. Disease progression and treatment responses in a prospective DMARD-naive seropositive early RA cohort: Does gender matter? J. Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 2475–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iikuni, N.; Sato, E.; Hoshi, M.; Inoue, E.; Taniguchi, A.; Hara, M.; Tomatsu, T.; Kamatani, N.; Yamanaka, H. The influence of sex on patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a large observational cohort. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 36, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanashi, S.; Kaneko, Y.; Takeuchi, T. Characteristics of patients with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 5247–5256. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lee, E.; Kim, J.W.; Suh, C.H.; Shin, K.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.A. Unveiling difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: Long-term impact of biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs from the KOBIO registry. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, N.; Barone, E.; Brunetta, E.; D’Isanto, A.; De Santis, M.; Ceribelli, A.; Caprioli, M.; Guidelli, G.M.; Renna, D.; Selmi, C. Obesity and fibromyalgia are associated with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis independent of age and gender. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2025, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togashi, T.; Ishihara, R.; Watanabe, R.; Shiomi, M.; Yano, Y.; Fujisawa, Y.; Katsushima, M.; Fukumoto, K.; Yamada, S.; Hashimoto, M. Rheumatoid factor: Diagnostic and prognostic performance and therapeutic implications in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooles, F.A.H.; Tarn, J.; Lendrem, D.W.; Naamane, N.; Lin, C.M.; Millar, B.; Maney, N.J.; E Anderson, A.; Thalayasingam, N.; Diboll, J.; et al. Interferon-α-mediated therapeutic resistance in early rheumatoid arthritis implicates epigenetic reprogramming. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, T.; Watanabe, R.; Ito, H.; Fujii, T.; Okuma, K.; Oku, T.; Hirayama, Y.; Ohmura, K.; Murata, K.; Murakami, K.; et al. Dynamics of type I and type II interferon signature determines responsiveness to anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 901437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Salinas, R.; Sanchez-Prado, E.; Mareco, J.; Ronald, P.; Ruta, S.; Gomez, R.; Magri, S. Difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis in a comprehensive evaluation program: Frequency according to different objective evaluations. Rheumatol. Int. 2023, 43, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, I.; Sawada, N.; Chijiwa, T. Clinical characteristics and variants that predict prognosis of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2022, 42, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Limón, P.; Mena-Vázquez, N.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Lisbona-Montañez, J.M.; Mucientes, A.; Manrique-Arija, S.; Redondo-Rodriguez, R.; Cano-García, L.; Tinahones, F.J.; Fernández-Nebro, A. Gut dysbiosis is associated with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1497756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, L.; Madrid-Garcia, A.; Lopez-Viejo, P.; González-Álvaro, I.; Novella-Navarro, M.; Freites Nuñez, D.; Rosales, Z.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, B.; Abasolo, L. Difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical issues at early stages of disease. RMD Open 2023, 9, e002842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanashi, S.; Takeuchi, T.; Kaneko, Y. Five-year follow-up of patients with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 2487–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, S.; Sonomoto, K.; Nakayamada, S.; Tanaka, Y. Preferable outcome of Janus kinase inhibitors for a group of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis patients: From the FIRST Registry. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, R.; Miyazaki, Y.; Nakayamada, S.; Fukuyo, S.; Kubo, S.; Miyagawa, I.; Yamaguchi, A.; Satoh-Kanda, Y.; Ohkubo, N.; Todoroki, Y.; et al. Effective second-line b/tsDMARDs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis unresponsive to first-line therapy: Data from the FIRST Registry. Rheumatol. Ther. 2025, 12, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | NO D2T (n = 180; 52%) | D2T (n = 164; 48%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70 (60.5–79) | 69 (57–78) | NS |

| Female, n (%) | 128 (71%) | 143 (87%) | NS |

| Male, n (%) | 52 (29%) | 21 (13%) | 0.004 |

| Disease duration (months) | 60 (20–114) | 108 (84–120) | 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 (26–28) | 28 (26–29) | NS |

| Active smokers, n (%) | 10 (5.5%) | 6 (3.6%) | NS |

| Ex-smokers, n (%) | 15 (8.3%) | 11 (6.7%) | NS |

| RF (IU/mL) | 46 (20–98) | 64 (20–156) | 0.031 |

| ACPA (IU/mL) | 108 (20–360) | 178 (20–1600) | 0.0053 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 9 (6–19) | 18 (13–20) | 0.018 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.24 (0.09–0.56) | 0.23 (0.05–0.7) | NS |

| DAS28-ESR | 1.56 (1.5–3.1) | 1.67 (1.5–3.2) | NS |

| CDAI | 3 (3–3.5) | 3 (3–3.5) | NS |

| HAQ | 0.5 (0.5–0.75) | 0.75 (0.5–0.75) | NS |

| PGA | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | NS |

| PhGA | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | NS |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 63 (35%) | 61 (37%) | NS |

| CV disease, n (%) | 66 (36%) | 51 (31%) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 16 (8.8%) | 12 (7.3%) | NS |

| Fibromyalgia, n (%) | 13 (7.2%) | 10 (6%) | NS |

| Depression, n (%) | 15 (8.3%) | 14 (8.5%) | NS |

| Interstitial lung disease, n (%) | 10 (5.5%) | 13 (7.9%) | NS |

| COPD, n (%) | 9 (5%) | 0 | NS |

| Osteoporosis, n (%) | 36 (20%) | 40 (24.4%) | NS |

| CKD, n (%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (1.2%) | NS |

| Steroid treatment, n (%) | 16 (8.8%) | 28 (17%) | 0.028 |

| Prednisone dose (mg/day) | 5 (2.5–5) | 5 (3.7–5) | NS |

| Methotrexate treatment, n (%) | 63 (35%) | 33 (20%) | 0.02 |

| Methotrexate dose (mg/week) | 10 (10–10) | 10 (5–10) | NS |

| Monotherapy, n (%) | 97 (53.8%) | 107 (65%) | NS |

| Advanced therapy (b/tsDMARDs), n (%) | 135 (75%) | 163 (99.3%) | 0.0001 |

| Current DMARD, n (%) | 45 (25%) | 27 (16%) | NS |

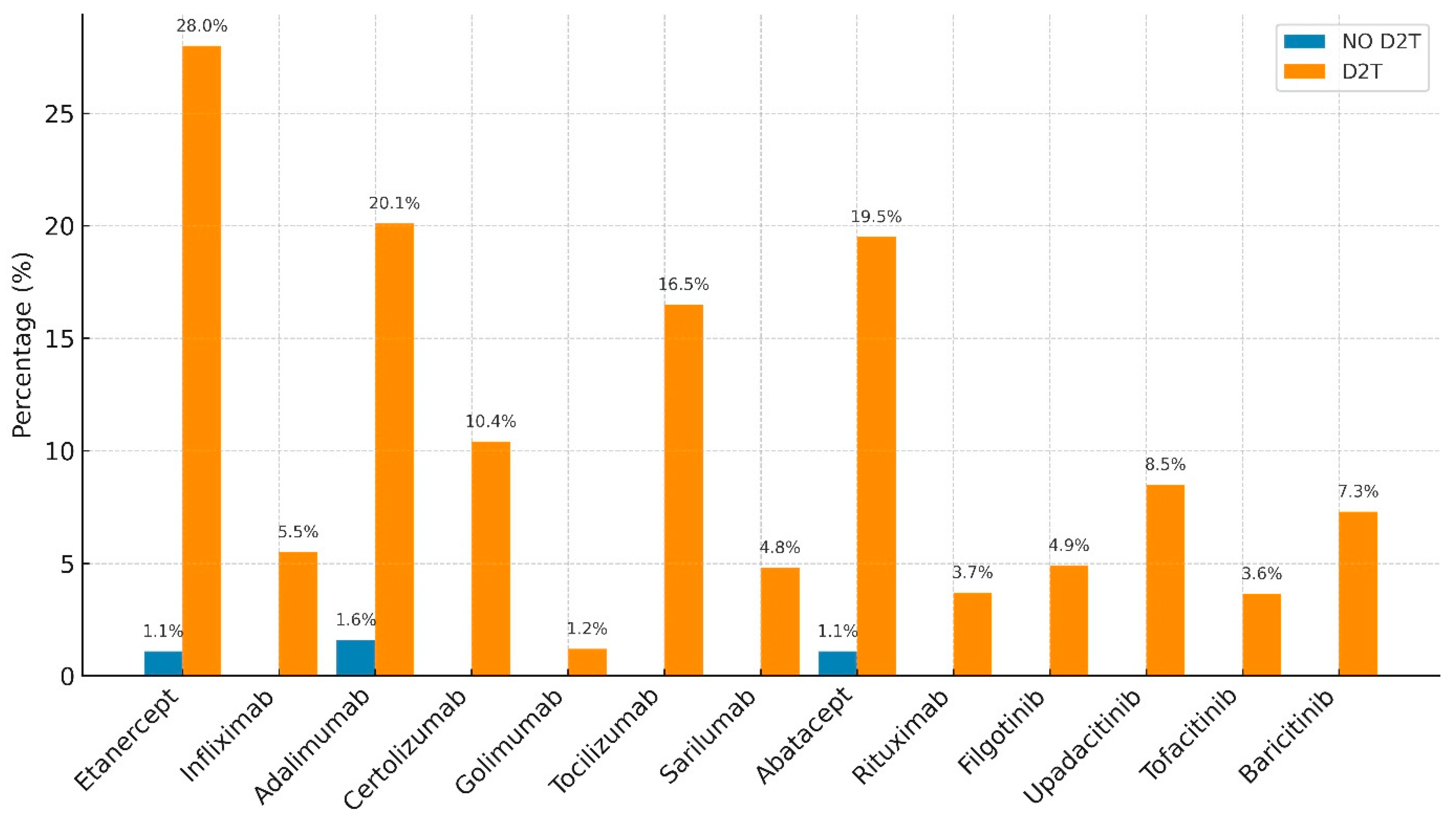

| Advanced Therapy Failure | NO D2T | D2T | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etanercept | 1.10% | 28% | 0.00001 |

| Infliximab | 0 | 5.50% | 0.0014 |

| Adalimumab | 1.60% | 20.10% | 0.00001 |

| Certolizumab | 0 | 10.40% | 0.0001 |

| Golimumab | 0 | 1.20% | NS |

| Tocilizumab | 0 | 16.50% | 0.00001 |

| Sarilumab | 0 | 4.80% | 0.0029 |

| Abatacept | 1.10% | 19.50% | 0.00001 |

| Rituximab | 0 | 3.70% | 0.012 |

| Filgotinib | 0 | 4.90% | 0.0029 |

| Upadacitinib | 0 | 8.50% | 0.00043 |

| Tofacitinib | 0 | 3.65% | 0.012 |

| Baricitinib | 0 | 7.30% | 0.00017 |

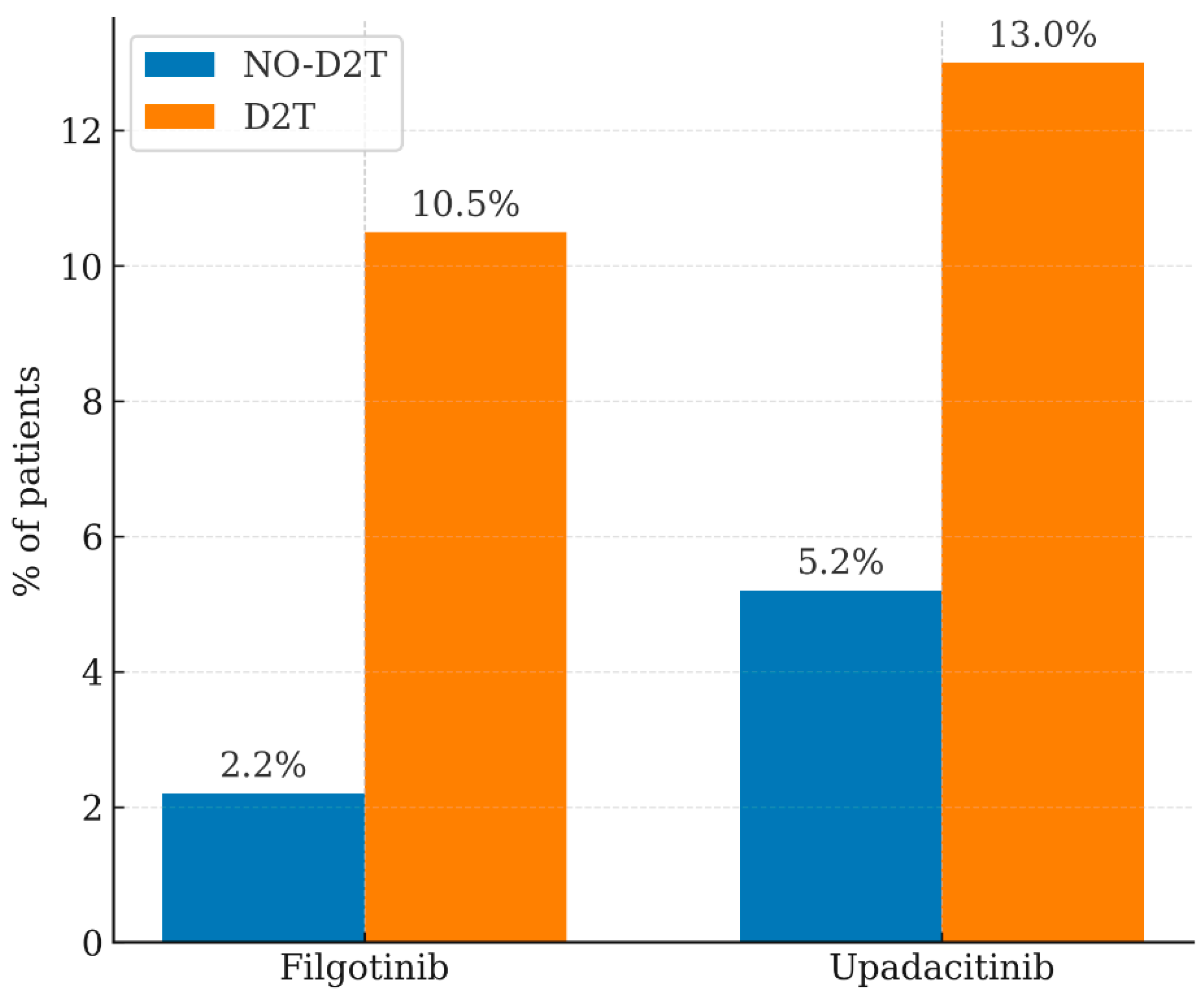

| Advanced Therapy Failure | NO D2T | D2T | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abatacept | 14.00% | 8.60% | NS |

| Adalimumab | 4.00% | 7.40% | NS |

| Baricitinib | 2.20% | 1.78% | NS |

| Certolizumab | 4.40% | 2.70% | NS |

| Etanercept | 25.00% | 14.70% | NS |

| Filgotinib | 2.20% | 10.50% | 0.015 |

| Sarilumab | 13.00% | 8.00% | NS |

| Tocilizumab | 26.00% | 28.00% | NS |

| Tofacitinib | 3.00% | 4.00% | NS |

| Upadacitinib | 5.20% | 13.00% | 0.0053 |

| Golimumab | 0.00% | 1.22% | NS |

| Rituximab | 0.00% | 0.60% | NS |

| Variable | p | Odds Ratio (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender M/F | 0.0017 | 0.377 (0.18–0.47) |

| Disease duration | 0.0001 | 1.0065 (0.63–1.58) |

| ACPA | 0.0009 | 1.0007 (0.64–1.69) |

| ESR | 0.0157 | 1.02 (0.75–1.26) |

| R2 = 0.68 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | t | p |

| Gender M/F | 3.27 | 0.012 |

| Disease duration | 4 | 0.0001 |

| ACPA | 2.9 | 0.036 |

| ESR | 2.38 | 0.017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Benucci, M.; Li Gobbi, F.; Cassarà, E.A.M.; Terenzi, R.; Cioffi, E.; D’Elia, C.; Aliberti, S.; Guiducci, S.; Russo, E.; Lari, B.; et al. Factors Associated with Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis (D2T-RA): Real-World Evidence from a Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020065

Benucci M, Li Gobbi F, Cassarà EAM, Terenzi R, Cioffi E, D’Elia C, Aliberti S, Guiducci S, Russo E, Lari B, et al. Factors Associated with Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis (D2T-RA): Real-World Evidence from a Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(2):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020065

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenucci, Maurizio, Francesca Li Gobbi, Emanuele Antonio Maria Cassarà, Riccardo Terenzi, Elisa Cioffi, Christian D’Elia, Sabrina Aliberti, Serena Guiducci, Edda Russo, Barbara Lari, and et al. 2026. "Factors Associated with Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis (D2T-RA): Real-World Evidence from a Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 2: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020065

APA StyleBenucci, M., Li Gobbi, F., Cassarà, E. A. M., Terenzi, R., Cioffi, E., D’Elia, C., Aliberti, S., Guiducci, S., Russo, E., Lari, B., Grossi, V., Infantino, M., & Manfredi, M. (2026). Factors Associated with Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis (D2T-RA): Real-World Evidence from a Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(2), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020065