Abstract

In Diabetes Mellitus (DM), a metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose due to impaired insulin action, platelet function is dysregulated and contributes to the pathological progression of the disease. In type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation impair endothelial function and platelet regulation, promoting a prothrombotic state. Platelet hyperreactivity is associated with T2DM cardiovascular complications, a leading cause of mortality in patients. Antiplatelet therapies often prove ineffective for a subset of T2DM patients due to aspirin resistance, necessitating alternative therapeutic strategies. Resveratrol, a natural polyphenol, is a potential therapeutic agent for T2DM, including inhibition of platelet aggregation. One of the pleiotropic actions of resveratrol is to modulate the FoF1-ATP synthase rotational catalysis. Platelet chemical energy demand during the activation phase is achieved through oxidative phosphorylation. Both mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation drive aerobic energy production in activated platelets, utilizing fatty acids and glucose, respectively. Hyperglycemia can cause an overwork of the oxidative phosphorylation, producing oxidative stress. Targeting FoF1-ATP synthase with resveratrol may reduce platelet hyperreactivity in aspirin-resistant cases. This paper reviews the implications of resveratrol ability to inhibit platelet FoF1-ATP synthase on its potential as a novel alternative or synergistic antiplatelet strategy for aspirin-resistant T2DM patients.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is classified into type 1 and type 2. Type 1 DM (T1DM) is an autoimmune disorder defined by the destruction of pancreatic β-cells by autoreactive T lymphocytes, leading to absolute insulin deficiency [1]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a metabolic disorder that presents with chronic hyperglycemia and an inadequate response to circulating insulin by peripheral tissues (insulin resistance), accounts for approximately 90% of global cases [2]. The growing prevalence of T2DM and its complications worldwide, both in high-income and low-income countries, is a significant public health challenge [2,3]. The global number of people with diabetes (primarily T2DM) is projected to exceed 1.3 billion by 2050 [3]. According to a system dynamics modelling study using national survey data, the population with diabetes in China, which has the highest number of patients with DM worldwide, is projected to face a dramatic growth in individuals with both DM (202.84 million by 2050) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (122.88 million by 2050), representing a substantial future economic burden [4]. Unhealthy lifestyle choices and genetic predisposition are the primary causes of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which is marked by the progressive loss of pancreatic β-cell function, leading to hyperglycemia [5]. Chronic oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation activate kinases, including NF-κB, thereby worsening insulin resistance and promoting β-cell apoptosis [6]. Impaired insulin signaling is driven by defects in the insulin receptor substrate (IRS)–phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway in tissues (skeletal muscle, liver, and adipose tissue) and by mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic-reticulum stress [7,8]. T2DM predisposes to both microvascular (diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy) and macrovascular (peripheral, coronary, and cerebral artery disease, atherosclerosis, and kidney disease) complications [9]. Cardiovascular complications are the leading cause of T2DM morbidity and mortality [5]. Increased cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is associated with structural platelet abnormalities and the presence of circulating immature platelets with mitochondrial dysfunction [10]. In T2DM, there is suppression of anticoagulant molecules, such as thrombomodulin, and impaired fibrinolysis, resulting in increased levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6), pro-coagulant factors (von Willebrand factor, VWF), plasma fibrinogen, and thrombin [11]. Hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, low-grade inflammation, and oxidative stress contribute to platelet hyperreactivity, promoting a pro-thrombotic state in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The inflammatory, pro-thrombotic environment heightens the cardiovascular risk observed in T2DM [12]. Therefore, in clinical practice, glucose-lowering, lipid-lowering drugs, and antiplatelet agents are employed [13,14]. By modulating platelet aggregation, it is possible to lower the risk of CVD [15].

Resveratrol (RSV) (3,4′,5-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a polyphenolic phytoalexin structurally related to stilbenes consisting of two phenolic rings bonded by a double styrene bond [16] RSV is synthesized in considerable amounts in grapes, peanuts, berry fruits, and a variety of medicinal and edible plants in response to stress conditions [17]. The low RSV solubility affects absorption, which differs depending on the dietary source. After oral intake, RSV is rapidly absorbed in the small intestine through passive diffusion and binding to transporters. These include multidrug resistance–associated proteins MRP2 and MRP3, members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, as well as integrins and others [18]. In humans, more than 70% of orally administered RSV is absorbed and rapidly metabolized (in less than 30 min). Its half-life is about 10 h [19]. RSV undergoes considerable phase I and phase II metabolism in the liver, resulting in the formation of glucuronic acid and sulfate conjugates, found in the b Szym loodstream, that preserve biological function [16]. Phase II sulfation and glucuronidation are catalyzed by sulfotransferase and uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes, respectively [20]. RSV phase I hydroxylation by CYP1B1 produces piceatannol, characterized by higher antioxidant properties [20]. In human studies using a single oral dose (25 mg), the free RSV blood peak was around 10 ng/mL within 2 h. Metabolite concentrations reached 500 ng/mL, suggesting that also conjugates have biological effects [21]. Free RSV is about 90% bound to plasma proteins, representing a reservoir [18]. RSV administration is generally well tolerated by healthy individuals, and its use in humans is considered safe in vivo [22].

2. Platelet Hyperactivation and Aspirin Resistance in T2DM

Platelets are anucleate cell fragments abundant in the bloodstream (150–400 × 109/L), generated by the megakaryocyte in the bone marrow [23]. Platelets express diverse receptors and ligands and contain several organelles (mitochondria, lysosomes, and alpha and dense granules) and specialized canalicular systems. As key players in hemostasis, upon vascular injury, platelets transition from a quiescent to an activated state and adhere to the exposed subendothelial matrix through a multistep process related to the shear conditions of blood flow [24]. Under high shear conditions, platelets are initially captured by VWF through GPIb binding, which enables subsequent firm adhesion to collagen via GPVI and integrin α2β1 [24]. RSV has been reported to interfere with both VWF-mediated platelet tethering and collagen-dependent stable adhesion [21]. Following adhesion, inside-out signaling triggered by agonists such as thrombin, ADP, and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) or adhesive proteins drives platelet aggregation by the conformational activation of GPIIb/IIIa (integrin αIIbβ3) [25]. Upon activation, αIIbβ3 shifts from a low- to high-affinity state that binds fibrinogen, VWF, and other ligands (e.g., vitronectin, fibronectin). Activated platelets become cross-linked via fibrinogen and VWF, linking GPIIb/IIIa receptors, leading to aggregate formation. The activated platelet surface promotes the assembly of coagulation factors, stabilizing the developing thrombus [24]. Alterations in platelet indices such as mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet distribution width (PDW), platelet-large cell ratio (P-LCR), and plateletcrit (PCT) have been reported in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), where they have been proposed as potential biomarkers of poor glycemic control [26]. In T2DM, platelets are hyperreactive, compared to controls [27,28]. Basal platelet activation is similar; however, the stimulated activation is significantly enhanced, which limits the effectiveness of aspirin [29,30]. Aspirin irreversibly blocks cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) by acetylating its serine-529 [14] preventing the conversion of arachidonic acid (AA) to thromboxane A2 (TXA2), a potent platelet aggregation agonist. Aspirin resistance (AR) in patients with diabetes is a clinical phenomenon empirically defined as a condition where the conventional dose of aspirin does not sufficiently suppress platelet aggregation [29]. Although AR can be due to other factors, such as lack of adherence to therapy, reduced bioavailability, or interactions with medications, a systematic review discussed AR prevalence in diabetic patients, which is higher than in other populations at cardiovascular risk [29]. AR has been studied more in T2DM than in T1DM. A classic ambulatory study characterized platelets in T1DM patients and found a lab-defined AR phenotype in T1DM associated with female sex, corresponding to a maladaptive phenotype with increased basal activity and hyperactivation upon stimulation [31]. Different direct and indirect laboratory assays are utilized to measure platelet functional AR. Serum thromboxane B2 (sTXB2) is the most specific pharmacodynamic marker of platelet COX-1 activity. High serum sTXB2 levels suggest inadequate platelet inhibition [32]. Test of urinary 11-dehydro-TXB2 reflects TXA2 but is less specific. Point-of-care test VerifyNow® Aspirin measures platelet response to aspirin using an arachidonic acid agonist to measure their ability to aggregate (results are expressed in Aspirin Reaction Units) [33]. The PFA-100 Indirect assay is another point-of-care assay that evaluates platelet reactivity in high-shear flow by measuring the time it takes for a platelet plug to occlude a small aperture in a membrane-coated cartridge (Closure Time CT) [34]. The concordance between assays is low due to a lack of standardization. Therefore, it is recommended to use at least one direct test and one functional test to investigate AR in T2DM [35]. Several features of T2DM can impair aspirin ability to suppress platelet aggregation. A systematic review comparing the characteristics of AR versus non-AR T2DM patients revealed that AR patients tend to be younger, have higher fasting glucose and HbA1c levels, higher rates of dyslipidemia, and a higher body mass index (BMI). However, no significant differences were observed in gender, comorbidities, or concurrent medications between the two groups [29]. Hyperglycemia induces nonenzymatic glycation of surface platelet proteins, decreasing membrane fluidity, and increasing protein kinase C activation [36]. In T2DM, inflammation enhances platelet phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure, thereby promoting increase expression of the surface glycoproteins Ib and IIb/IIIa [28], of Fcγ receptor type IIa (FcγRIIa) and factor Va binding [37]. Diabetes is associated with systemic inflammation and oxidative stress that may contribute to increased platelet reactivity [38]. Patients with T2DM exhibit constitutively activated P2Y12 receptor expression, causing ADP-induced platelet hyperreactivity [39]. Hypertriglyceridemia due to elevated VLDL (common in T2DM) correlates with AR, partly linked to apolipoprotein E. Guidelines still recommend low-dose aspirin (75–100 mg daily) for secondary prevention in diabetes, but individualized use for primary prevention. Routine twice-daily (BID) dosing for T2DM patients is not recommended, due to a lack of evidence (Diabetes Care 2024 guidelines) [40]. A small pharmacodynamic (PD) study trial on T2DM patients without CVD randomized in a three-way crossover design to a two-week treatment showed that 100 mg BID low-dose aspirin reduced platelet reactivity better than 100 mg once a day (QD) and numerically more than 200 mg QD. Clinical outcome trials evaluating primary CVD prevention with aspirin in Type 2 diabetes may need to consider using a more frequent dosing schedule [41]. No outcomes from large, randomized trials yet demonstrate that BID (or higher dose) improves CVD in T2DM compared with standard QD dosing. The Ongoing ANDAMAN trial on adult (type 1 or type 2) patients with DM or AR admitted to the intensive cardiac care unit plans to evaluate the superiority of twice-daily compared to once-daily aspirin in patients with DM or AR during a follow-up of 18 months after acute coronary syndrome [42]. The ADAPTABLE study, a large open label, multicentric trial, enrolled patients with DM and concomitant CVD and randomized them to 81 mg or 325 mg of daily aspirin. No difference was found for the daily aspirin dosing strategies for patients with DM in the primary outcomes (death, myocardial infarction, or hospitalization for stroke) or safety outcomes (major bleeding) [43].

Endothelial Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes

In T2DM, AR results from a combination of internal platelet changes and external factors that increase the risk of thrombosis [12,23]. In the T2DM dysmetabolic and pro-oxidant milieu, hyperreactive platelets establish a crosstalk with endothelial cells [30], contributing to endothelial dysfunction, a hallmark of T2DM. The intact endothelium, a monolayer lining the inner surface of the vascular lumen, maintains an antithrombotic condition by producing nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGI2), which retard platelet activation by increasing intraplatelet concentrations of cyclic guanosine- and adenosine-monophosphate [44]. Vascular oxidative stress reduces NO and PGI2 availability [45]. Contributing to platelet hyperreactivity and endothelial activation [46], increasing the release of VWF, which promotes platelet adhesion and enhanced platelet consumption and turnover. The latter in turn causes newly formed immature platelets with uninhibited COX-1 to enter the circulation [29]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA), which provides the current clinical practice recommendations for DM care [40], recommends standard low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention, but individualized use for primary prevention, as the bleeding risk may outweigh the cardiovascular benefit of aspirin, and because T2DM patient platelets may not respond adequately to aspirin therapy [47]. Antiplatelet bioactive compounds in food may represent an early intervention to prevent AR and thus may prevent T2DM, significantly impacting T2DM complications [48].

3. Clinical Use of Resveratrol in Diabetes

RSV displays antibacterial effects against various pathogens (Campylobacter, Staphylococcus aureus, and others), related to its ability to inhibit the ATP synthase, decreasing the bacterial cellular energy [49]. In humans RSV has numerous promising therapeutic properties, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, endothelial protective, antitumor, anti-adipogenic, and antidiabetic, and has been suggested to be able to modulate AR states [16,50,51,52]. RSV inhibits platelet aggregation by suppressing thromboxane A2 (TXA2) synthesis through COX-1 inhibition, improves glucose homeostasis, decreases insulin resistance, diminishes AR, protects pancreatic β-cells, and increases GLUT4 and GLUT2 levels [51]. RSV improves glycemic control and insulin resistance in DM by enhancing glucose uptake, promoting GLUT4 expression and translocation, and activating the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase Silent Information Regulator 1 (Sirtuin1), which inhibits Forkhead transcription factor O1 (FOXO1) expression, exerting protective effects on mitochondrial dysfunction, one of the main drivers of T2DM [50,51]. By attenuating oxidative stress, RSV exerts protective effects in diabetic retinopathy and DM macrovascular complications [53]. RSV modulates several dysregulated metabolic and signaling pathways, such as 5′ AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK) and Sirtuin1, protecting pancreatic β-cells and lowering the levels of circulating free fatty acids (FFAs), reducing FFA-induced lipotoxicity. At the platelet level, RSV preserved their ability to aggregate, reducing post-storage prothrombotic action [54]. Ex vivo studies on platelets demonstrated that RSV reduces platelet oxygen consumption, aggregation, and TXA2 release, reflecting inhibition of platelet metabolic hyperactivity [55]. RSV acts on several intracellular signaling cascades implicated in platelet activation, including PI3K/Akt, PKC, and MAPK pathways, and promotes NO and cyclic GMP (cGMP) signaling, modulating calcium mobilization and granule secretion [56,57]. Studies on the beneficial effects of RSV on diabetes in DM have been mostly conducted on animal models or in vitro (reviewed in [50]). Some clinical studies confirm the notion that RSV supplementation reduces systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, improving lipid and endothelial profiles in DM, while others do not find significant results (see Table 1) [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Table 1.

Clinical Studies of Resveratrol in T2DM (Human Trials) Randomized or controlled clinical trial, including study type, study population, sample size, and potential efficacy.

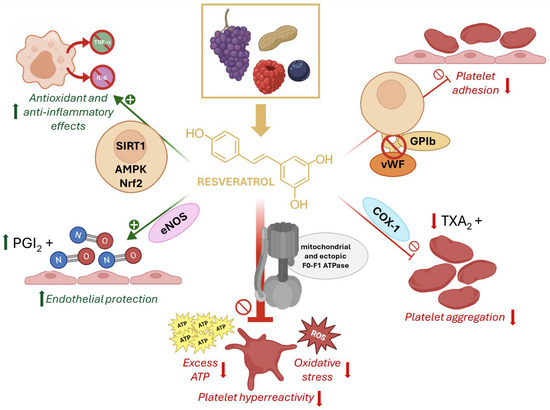

Nonetheless, a randomized meta-analysis on patients with T2DM concluded that RSV supplementation led to reductions in C-reactive protein levels, lipid peroxidation markers, and oxidative stress [68]. Additionally, RSV improved resistance to oxidative stress by promoting the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase and catalase, thereby exerting beneficial effects on inflammation and oxidative stress [68]. A single-blind, randomized controlled clinical trial on elderly T2DM patients, assessing a 6-month treatment period with RSV, reported improved blood glucose control, inflammation, insulin resistance, and renal function [69]. The modulation of the same molecular targets, including also endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) exerts protective effects of RSV on the endothelium [57]. Specifically, RSV may modulate VWF binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib (GPIb), a critical interaction under high shear stress that initiates platelet adhesion to the endothelium, and thrombus formation [55]. As antiplatelet drugs like aspirin are not recommended for primary prevention, RSV may be a viable alternative to prevent AR, particularly in patients with T2DM. RSV pleiotropic actions can favorably affect AR (Figure 1) [50].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure and mechanisms of resveratrol in platelet hyperactivation. Resveratrol (RSV), a natural polyphenol found in grapes, peanuts, and berries, exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects through activation of SIRT1, AMPK, and Nrf2 pathways. It enhances endothelial protection by stimulating nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and prostacyclin (PGI2) release. RSV inhibits platelet adhesion by interfering with von Willebrand factor (vWF) binding to GPIb, and reduces platelet aggregation by suppressing cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1)–mediated thromboxane A2 (TXA2) formation. Importantly, RSV directly modulates mitochondrial and ectopic F0F1-ATP synthase, reducing excess ATP production and oxidative stress, thereby attenuating platelet hyperreactivity.

4. The F1Fo-ATP Synthase

The F1Fo-ATP synthase (ATP synthase), or Complex V, is a protein complex that couples the proton gradient generated by the ETC Complexes I–IV to ATP production [70]. The ATP synthase is a key enzyme of the oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) pathway [71]; it employs a transmembrane protonmotive force as a source of energy to drive a mechanical rotary catalytic mechanism that synthesizes ATP from ADP and phosphate. The ATP synthase structure comprises a Fo moiety, constituted by a membrane-embedded rotor ring (8–14 c-subunits) and the a-subunit that allows protons to flow down their electrochemical gradient, and a catalytic F1 moiety protruding into the matrix (α3β3 hexamer with central γ, δ, ε subunits). The F1 can hydrolyze ATP. The inhibitory factor 1 (IF1) binds the F1 domain to prevent ATP waste when the mitochondrial membrane potential collapses [72]. Genetic defects in the ATP synthase are associated with mitochondrial disorders, a group of genetic conditions that impair the OxPhos [73]. The ATP synthase is found in the membranes of mitochondria, bacteria, and chloroplasts; however, biochemical, proteomic, and imaging studies have shown that it is also present in ectopic locations [74]. An ectopic ATP synthase is expressed on the plasma membrane (in this case, defined ecto-ATP synthase) of many cancer cells [75,76,77,78]. The ectopic ATP synthases not only carry out the synthesis of extracellular ATP, such as on the neuronal surface [79], human umbilical vein endothelial (HUVEC) cells [79,80] and hepatocytes [81], but also participate in numerous cellular functions [82]. Citreoviridin, an ATP synthase inhibitor, showed cytotoxic effects on NSCLC cells expressing an ecto-ATP synthase [76]. The ectopic ETC complexes coupled to the synthase carry out an OxPhos in rod outer segment (OS) disks and myelin sheath [83], exosomes and microvesicles [84,85], and platelets [86,87]. Our previous data showed that human platelets exhibit an extra-mitochondrial OxPhos, representing an additional source of the chemical energy needed to support activation [86,87]. Immunofluorescence analysis showed the co-localization with calnexin (a marker of endoplasmic reticulum, ER) of subunit II of Cytochrome c Oxidase (COXII) encoded by mitochondrial DNA and ATP synthase, but not TIM, suggesting that in platelets, the extra-mitochondrial OxPhos could occur in the inner membranes, such as the ER [86]. Western Blot analysis of platelets revealed that the ratio of ATP synthase to TIM (Translocase of the Inner Mitochondrial membrane) signal was approximately two-fold higher in platelets compared with mitochondria [86]. The communication system between organelles, known as mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs), may be involved in the putative transfer of the OxPhos machinery to ectopic locations, primarily the ER [88]. Several proteins tether the mitochondria to the ER, creating dynamic regions that regulate various biological processes, including mitochondrial dynamics. Interestingly, dysregulation of MAMs is associated with the progression of several disorders, particularly diabetes mellitus [88]. A hallmark of platelets is their remarkable metabolic flexibility [87,89,90,91], enabling them to adapt to the continually varying environmental and functional conditions, from a resting state mostly relying on glycolysis to an activated state characterized by a shift to oxidative metabolism [90,91]. Platelet activation triggers an increase in OxPhos sustained enhanced glucose uptake (mediated primarily by glucose transporter 3, GLUT3), which glycolysis alone cannot support [90]. The remarkable ability of platelets to shift their use of substrates, specifically glucose and fatty acids, upon activation could depend on the subcellular compartmentalization of metabolic pathways and the timely redirection of resources [87,90]. The extra-mitochondrial OxPhos capacity of platelets would represent a compartment able to utilize glucose to fuel an oxidative metabolism outside the mitochondria that would readily supply ATP to the cell [87]. However, the extra-mitochondrial OxPhos can have both beneficial and detrimental effects, being the primary source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [92]. Hyperglycemia can enhance OxPhos and contribute to platelet hyperactivation in T2DM [93]. When platelets become hyperactivated in T2DM, increased glucose uptake can overstimulate the extra-mitochondrial OxPhos, leading to a dangerous increase in ROS in the cytosol. In this context, in addition to the numerous beneficial effects of RSV [55], the action of RSV binding to the ectopic ATP synthase Fo moiety in the platelets is noteworthy, justifying the use of RSV as an effective antiplatelet therapy. In a streptozotocin-induced T2DM rat model, platelet hyperactivation was associated with increased OxPhos, not observed in the hepatocyte mitochondria [94]. RSV specific antioxidant modulatory action on the ectopic ATP synthase could limit the detrimental oxidative stress production in the platelet cytosol. In fact, the modulation of the ATP synthase by polyphenols has been shown to reduce ROS production by the ectopic ETC [95].

5. Resveratrol Inhibition of ATP Synthase and Its Relevance in AR

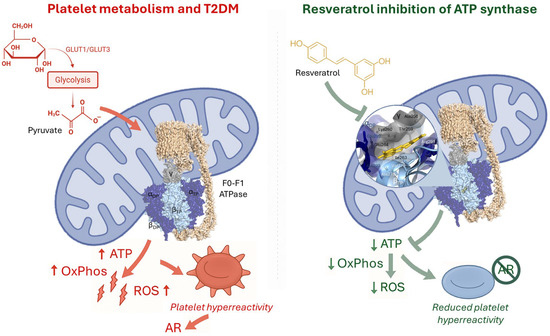

RSV binds and inhibits the mitochondrial ATP synthase, as shown by structural studies [80] that showed a direct interaction of the polyphenol with its F1 moiety, which may underlie some of its bioenergetic and signaling effects. The modulation of the ectopic OxPhos by RSV which can bind ATP synthase in the platelets may play a pivotal role in alleviating the ROS production, ultimately counteracting AR. The mitochondrial dysfunction in AR may include the extra-mitochondrial OxPhos. The platelet metabolic microenvironment influences multiple physiological and pathological conditions [86]. Platelets exhibit a distinct metabolic flexibility that allows them to adapt to varying conditions regarding substrate availability and metabolic capacity [87]. While resting platelets mainly utilize anaerobic glycolysis, activated platelets would rely on an extra-mitochondrial OxPhos that utilizes glucose and a mitochondrial OxPhos that utilizes fatty acids [87]. OxPhos over-functioning, such as in the case of chronic hyperglycemia, can lead to excess ROS generation. Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in the development of diabetes complications [96]. Intraplatelet glucose concentration mirrors the blood concentrations, and hyperglycemia is an AR cause factor. Upon activation, platelets undergo a rapid uptake of glucose through GLUT3 and switch to an oxidative metabolism, which relies on the ETC, the primary source of ROS [97]. Extra-mitochondrial OxPhos overfunctioning, driven by excess glucose availability, can lead to increased ROS production in the cytosol, which could be a primary contributor to the platelet oxidative stress and AR. Excessive OxPhos activity can lead to increased ROS production, both inside the mitochondrial matrix and in the cytosol, due to extra-mitochondrial OxPhos, which contributes to oxidative stress. Elevated ROS and inflammation determine a pro-thrombotic environment. The modulation of platelet ectopic OxPhos by RSV may play a pivotal role in counteracting oxidative stress, ultimately alleviating AR [98]. This hypothesis is consistent with the data showing that the ATP synthase as the molecular target of Chromium (III), a nontoxic form of chromium. In hepatic cells (HepG2), Cr3+ binds the ATP synthase β subunit, the catalytic subunit of the ATP synthase, abolishing its catalytic activity in a dose-dependent manner, which ameliorates hyperglycemia [99]. Also, it was proposed that elevated serum IF1 levels, protective against CVD may act by inhibiting the ecto-ATP synthase [100]. These data suggest that the inhibition of ATP synthase by RSV might be important in its action against AR (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Platelet metabolism in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and resveratrol inhibition of ATP synthase. (Left panel) In T2DM, increased glucose uptake and glycolysis lead to excessive pyruvate availability, fueling mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) via the F0F1-ATPase complex. This results in excessive ATP and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, contributing to platelet hyperreactivity and aspirin resistance (AR). (Right panel) Resveratrol directly interacts with the ATP synthase complex, reducing OxPhos activity, ATP output, and ROS generation. This inhibition attenuates platelet hyperreactivity and counteracts AR, highlighting its potential as an adjunct antiplatelet therapy in diabetes. The structural model of ATP synthase (PDB: 2JIZ) is shown, with a magnified view illustrating key amino acid residues predicted to interact with resveratrol.

6. Conclusions

RSV exhibits strong mechanistic rationale and preclinical evidence as a potential adjunctive therapy for T2DM. However, its clinical application as an antiplatelet treatment for patients with AR is still in the early stages. To fully understand the protective effects of RSV, its inhibitory action on the platelet extra-mitochondrial ATP synthase, as well as the ectopic ATP synthase found in the plasma membrane of endothelial cells, should be taken into account. Modulating these components, along with the ETC associated with them, can lead to a reduction in AR, endothelial activation, and ultimately inflammation. Future randomized controlled trials involving T2DM patients with confirmed AR may help clarify optimal dosages and treatment duration. There are some limitations to the clinical implementation of RSV for AR. These include its poor bioavailability due to rapid metabolism, the lack of sufficient data regarding AR in T2DM patients, uncertainties surrounding dose–response relationships, and the potential for interactions with antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapies that could increase the risk of bleeding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, writing—original draft preparation, I.P., writing—review and editing, I.P. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| ETC | Electron Trasport Chain |

| RSV | Resveratrol |

| AR | Aspirin Resistance |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes mellitus |

| TXA2 | Thromboxane A2 |

References

- Atkinson, M.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Michels, A.W. Type 1 Diabetes. Lancet 2014, 383, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.B.; Hashim, M.J.; King, J.K.; Govender, R.D.; Mustafa, H.; Kaabi, J. Al Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes—Global Burden of Disease and Forecasted Trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chang, G.Y.; Jiang, Y.H.; Xu, L.; Shen, L.; Gu, Z.C.; Lin, H.W.; Shi, F.H. System Dynamic Model Simulates the Growth Trend of Diabetes Mellitus in Chinese Population: Implications for Future Urban Public Health Governance. Int. J. Public. Health 2022, 67, 1605064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global Aetiology and Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Sathyapalan, T.; Atkin, S.L.; Sahebkar, A. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Oxidative Stress and Diabetes Mellitus. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 609213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Colon-Negron, K.; Papa, F.R. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Degeneration of Pancreatic Islet β-Cells, and Therapeutic Modulation of the Unfolded Protein Response in Diabetes. Mol. Metab. 2019, 27, S60–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Xie, M.; Liu, Q.; Li, S. Vascular Complications of Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Medicine 2023, 102, E35285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Souza, L.F.; Oliveira, M.F. Mitochondria: Biological Roles in Platelet Physiology and Pathology. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 50, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczyńska, M.; Bryk, A.H.; Malinowski, K.P.; Draga, K.; Undas, A. Interplay between Elevated Cellular Fibronectin and Plasma Fibrin Clot Properties in Type 2 Diabetes. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretorius, E. Platelets as Potent Signaling Entities in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.X.; Ma, X.N.; Guan, C.H.; Li, Y.D.; Mauricio, D.; Fu, S.B. Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Progress toward Personalized Management. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodanno, D.; Angiolillo, D.J. Aspirin for Primary Cardiovascular Risk Prevention and Beyond in Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2016, 134, 1579–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zong, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Platelets and Diseases: Signal Transduction and Advances in Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Li, C.X.; Kakar, M.U.; Khan, M.S.; Wu, P.F.; Amir, R.M.; Dai, D.F.; Naveed, M.; Li, Q.Y.; Saeed, M.; et al. Resveratrol (RV): A Pharmacological Review and Call for Further Research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camont, L.; Cottart, C.H.; Rhayem, Y.; Nivet-Antoine, V.; Djelidi, R.; Collin, F.; Beaudeux, J.L.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D. Simple Spectrophotometric Assessment of the Trans-/Cis-Resveratrol Ratio in Aqueous Solutions. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 634, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier-Salamon, A.; Böhmdorfer, M.; Riha, J.; Thalhammer, T.; Szekeres, T.; Jaeger, W. Interplay between Metabolism and Transport of Resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1290, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaglione, P.; Sforza, S.; Galaverna, G.; Ghidini, C.; Caporaso, N.; Vescovi, P.P.; Fogliano, V.; Marchelli, R. Bioavailability of Trans-Resveratrol from Red Wine in Humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak, I.; Marcinkowska, J.; Kucinska, M.; Regulski, M.; Murias, M. Resveratrol Bioavailability After Oral Administration: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trial Data. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambini, J.; Inglés, M.; Olaso, G.; Lopez-Grueso, R.; Bonet-Costa, V.; Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Abdelaziz, K.M.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Vina, J.; et al. Properties of Resveratrol: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies about Metabolism, Bioavailability, and Biological Effects in Animal Models and Humans. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2015, 2015, 837042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Porte, C.; Voduc, N.; Zhang, G.; Seguin, I.; Tardiff, D.; Singhal, N.; Cameron, D.W. Steady-State Pharmacokinetics and Tolerability of Trans-Resveratrol 2000 Mg Twice Daily with Food, Quercetin and Alcohol (Ethanol) in Healthy Human Subjects. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010, 49, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.T.; Corken, A.; Ware, J. Platelets at the Interface of Thrombosis, Inflammation, and Cancer. Blood 2015, 126, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broos, K.; Feys, H.B.; De Meyer, S.F.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; Deckmyn, H. Platelets at Work in Primary Hemostasis. Blood Rev. 2011, 25, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordan, R.; Tsoupras, A.; Zabetakis, I. Platelet Activation and Prothrombotic Mediators at the Nexus of Inflammation and Atherosclerosis: Potential Role of Antiplatelet Agents. Blood Rev. 2021, 45, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.; Raizada, N.; Kalra, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Platelet Indices as Predictors of Glycaemic Status and Complications in Diabetes Mellitus. Apollo Med. 2025, 22, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, V.; De Berardis, G.; Totani, L.; Avanzini, F.; Giorda, C.B.; Brero, L.; Levantesi, G.; Marelli, G.; Pupillo, M.; Iacuitti, G.; et al. Persistent Platelet Activation in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Treated with Low Doses of Aspirin. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 2197–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, L.; Thomson, G.J.A.; Adams, R.C.M.; Nell, T.A.; Laubscher, W.A.; Pretorius, E. Platelet Activity and Hypercoagulation in Type 2 Diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zheng, H. Clinical Predictors of Aspirin Resistance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 26009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, M.; Singh, J. Endothelial Dysfunction and Platelet Hyperactivity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Strategies. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, R.C.; Yates, D.M.; Pearson, S.M.; Kietsiriroje, N.; Hindle, M.S.; Cheah, L.T.; Webb, B.A.; Ajjan, R.A.; Naseem, K.M. Insulin Resistance in Type 1 Diabetes Is a Key Modulator of Platelet Hyperreactivity. Diabetologia 2025, 68, 1544–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, G.; Rizzi, A.; Bellavia, S.; Dentali, F.; Frisullo, G.; Pitocco, D.; Ranalli, P.; Rizzo, P.A.; Scala, I.; Silingardi, M.; et al. Stability of the Thromboxane B2 Biomarker of Low-Dose Aspirin Pharmacodynamics in Human Whole Blood and in Long-Term Stored Serum Samples. Res. Pr. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 8, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, H.L.; Kristensen, S.D.; Hvas, A.-M. Is the New Point-of-Care Test VerifyNow® Aspirin Able To Identify Aspirin Resistance Using the Recommended Cut-Off? Blood 2007, 110, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reny, J.L.; De Moerloose, P.; Dauzat, M.; Fontana, P. Use of the PFA-100TM Closure Time to Predict Cardiovascular Events in Aspirin-Treated Cardiovascular Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008, 6, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renda, G.; Zurro, M.; Malatesta, G.; Ruggieri, B.; de Caterina, R. Inconsistency of Different Methods for Assessing Ex Vivo Platelet Function: Relevance for the Detection of Aspirin Resistance. Haematologica 2010, 95, 2095–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouros, N.; Rade, J.J.; Kourliouros, A.; Resar, J.R. Platelet Function in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: From a Theoretical to a Practical Perspective. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 2011, 742719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmara, M.; Hjemdahl, P.; Östenson, C.G.; Li, N. Platelet Hyperprocoagulant Activity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Attenuation by Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibition. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008, 6, 2186–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Pignatelli, P. Platelet Oxidative Stress and Thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 2012, 129, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Chang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, S.; Qi, Z.; Yan, H.; Yan, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, S.; et al. Platelets Express Activated P2Y12 Receptor in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2017, 136, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, A.D.A.P.P.; ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Bannuru, R.R.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Das, S.R.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S179–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethel, M.A.; Harrison, P.; Sourij, H.; Sun, Y.; Tucker, L.; Kennedy, I.; White, S.; Hill, L.; Oulhaj, A.; Coleman, R.L.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Impact on Platelet Reactivity of Twice-Daily with Once-Daily Aspirin in People with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2016, 33, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillinger, J.-G.; Pezel, T.; Batias, L.; Angoulvant, D.; Goralski, M.; Ferrari, E.; Cayla, G.; Silvain, J.; Gilard, M.; Lemesle, G.; et al. Twice-a-Day Administration of Aspirin in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus or Aspirin Resistance after Acute Coronary Syndrome: Rationale and Design of the Randomized ANDAMAN Trial. Am. Heart J. 2025, 288, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narcisse, D.I.; Kim, H.; Wruck, L.M.; Stebbins, A.L.; Muñoz, D.; Kripalani, S.; Effron, M.B.; Gupta, K.; Anderson, R.D.; Jain, S.K.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Aspirin Dosing in Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Mellitus: A Subgroup Analysis of the ADAPTABLE Trial. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger-Genge, A.; Blocki, A.; Franke, R.P.; Jung, F. Vascular Endothelial Cell Biology: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, A.R.; Wolska, N.; Vara, D.; Mailer, R.K.; Schröder, K.; Pula, G. Diabetes and Thrombosis: A Central Role for Vascular Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, H.; Roebuck, K.A. Oxidant Stress and Endothelial Cell Dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001, 280, C719–C741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sofiani, M.E.; Yanek, L.R.; Faraday, N.; Kral, B.G.; Mathias, R.; Becker, L.C.; Becker, D.M.; Vaidya, D.; Kalyani, R.R. Diabetes and Platelet Response to Low-Dose Aspirin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 4599–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttaroy, A.K. Functional Foods in Preventing Human Blood Platelet Hyperactivity-Mediated Diseases-An Updated Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, F.; Duan, G.; Chen, S.; Long, J.; Jin, Y.; Yang, H. Recent Advances in the Use of Resveratrol against Staphylococcus Aureus Infections (Review). Med. Int. 2024, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Zhao, W.; Xu, S.; Weng, J. Resveratrol in Treating Diabetes and Its Cardiovascular Complications: A Review of Its Mechanisms of Action. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushki, M.; Farahani, M.; Yekta, R.F.; Frazizadeh, N.; Bahari, P.; Parsamanesh, N.; Chiti, H.; Chahkandi, S.; Fridoni, M.; Amiri-Dashatan, N. Potential Role of Resveratrol in Prevention and Therapy of Diabetic Complications: A Critical Review. Food Nutr. Res. 2024, 68, 9731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Roh, G.S.; Choi, W.S.; Cho, G.J. Resveratrol Blocks Diabetes-Induced Early Vascular Lesions and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Induction in Mouse Retinas. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012, 90, e31–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaštelan, S.; Konjevoda, S.; Sarić, A.; Urlić, I.; Lovrić, I.; Čanović, S.; Matejić, T.; Šešelja Perišin, A. Resveratrol as a Novel Therapeutic Approach for Diabetic Retinopathy: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Potential, and Future Challenges. Molecules 2025, 30, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lannan, K.L.; Refaai, M.A.; Ture, S.K.; Morrell, C.N.; Blumberg, N.; Phipps, R.P.; Spinelli, S.L. Resveratrol Preserves the Function of Human Platelets Stored for Transfusion. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 172, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michno, A.; Grużewska, K.; Ronowska, A.; Gul-Hinc, S.; Zyśk, M.; Jankowska-Kulawy, A. Resveratrol Inhibits Metabolism and Affects Blood Platelet Function in Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubatka, P.; Mazurakova, A.; Koklesova, L.; Samec, M.; Sokol, J.; Samuel, S.M.; Kudela, E.; Biringer, K.; Bugos, O.; Pec, M.; et al. Antithrombotic and Antiplatelet Effects of Plant-Derived Compounds: A Great Utility Potential for Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Care in the Framework of 3P Medicine. EPMA J. 2022, 13, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsamanesh, N.; Asghari, A.; Sardari, S.; Tasbandi, A.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Xu, S.; Sahebkar, A. Resveratrol and Endothelial Function: A Literature Review. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 170, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Ponzo, V.; Ciccone, G.; Evangelista, A.; Saba, F.; Goitre, I.; Procopio, M.; Pagano, G.F.; Cassader, M.; Gambino, R. Six Months of Resveratrol Supplementation Has No Measurable Effect in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 111, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjabeen, W.; Khan, D.A.; Mirza, S.A. Role of Resveratrol Supplementation in Regulation of Glucose Hemostasis, Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2022, 66, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Ponzo, V.; Evangelista, A.; Ciccone, G.; Goitre, I.; Saba, F.; Procopio, M.; Cassader, M.; Gambino, R. Effects of 6 Months of Resveratrol versus Placebo on Pentraxin 3 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Acta Diabetol. 2017, 54, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmers, S.; De Ligt, M.; Phielix, E.; Van De Weijer, T.; Hansen, J.; Moonen-Kornips, E.; Schaart, G.; Kunz, I.; Hesselink, M.K.C.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B.; et al. Resveratrol as Add-on Therapy in Subjects with Well-Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2211–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thazhath, S.S.; Wu, T.; Bound, M.J.; Checklin, H.L.; Standfield, S.; Jones, K.L.; Horowitz, M.; Rayner, C.K. Administration of Resveratrol for 5 Wk Has No Effect on Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Secretion, Gastric Emptying, or Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, S.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Toupchian, O.; Sheikhha, M.H.; Fallahzadeh, H.; Rahmanian, M.; Tabatabaie, M.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H. The Effect of Resveratrol Supplementation on Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 3153–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyyedebrahimi, S.S.; Khodabandehloo, H.; Nasli Esfahani, E.; Meshkani, R. Correction to: The Effects of Resveratrol on Markers of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseini, A.; Namazi, G.; Farrokhian, A.; Reiner, Ž.; Aghadavod, E.; Bahmani, F.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Resveratrol on Metabolic Status in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Coronary Heart Disease. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 6042–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, B.I.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Effect of Resveratrol on Markers of Oxidative Stress and Sirtuin 1 in Elderly Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, B.I.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Influence of Age and Dose on the Effect of Resveratrol for Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Molecules 2022, 27, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Jin, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhou, X. The Efficacy of Resveratrol Supplementation on Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 15, 1463027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Resveratrol Therapy on Glucose Metabolism, Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Renal Function in the Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Protocol. Medicine 2022, 101, E30049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.E. The ATP Synthase: The Understood, the Uncertain and the Unknown. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, P.D. The ATP Synthase—A Splendid Molecular Machine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997, 66, 717–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, M.; Casswell, E.; Chong, S.; Farah, Z.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Abramov, A.Y.; Tinker, A.; Duchen, M.R. Regulation of Mitochondrial Structure and Function by the F1Fo-ATPase Inhibitor Protein, IF1. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino Gomes, T.M.; Ng, Y.S.; Pickett, S.J.; Turnbull, D.M.; Vincent, A.E. Mitochondrial DNA Disorders: From Pathogenic Variants to Preventing Transmission. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, R245–R253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfoli, I.; Ravera, S.; Bruschi, M.; Candiano, G.; Morelli, A. Proteomics Unravels the Exportability of Mitochondrial Respiratory Chains. Expert. Rev. Proteomics 2011, 8, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, L.O.; Jacquet, S.; Esteve, J.P.; Rolland, C.; Cabezon, E.; Champagne, E.; Pineau, T.; Georgeaud, V.; Walker, J.E.; Terce, F.; et al. Ectopic Beta-Chain of ATP Synthase Is an Apolipoprotein A-I Receptor in Hepatic HDL Endocytosis. Nature 2003, 421, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.W.; Hsu, C.L.; Tang, C.W.; Chen, X.J.; Huang, H.C.; Juan, H.F. Multiomics Reveals Ectopic ATP Synthase Blockade Induces Cancer Cell Death via a LncRNA-Mediated Phospho-Signaling Network. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2020, 19, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.-H.; Song, S.-H.; Paik, J.-Y.; Koh, B.-H.; Choe, Y.S.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, B.-T.; Lee, K.-H. Direct Targeting of Tumor Cell F(1)F(0) ATP-Synthase by Radioiodine Angiostatin In Vitro and In Vivo. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2007, 22, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwin, L.H.; Blonder, J.; Bumke, M.A.; Lucas, D.A.; Chan, K.C.; Conrads, T.P.; Issaq, H.J.; Veenstra, T.D.; Newton, D.L.; Rybak, S.M. Proteomic Analysis of Plasma Membrane from Hypoxia-Adapted Malignant Melanoma. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 2996–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Shimizu, N.; Obi, S.; Kumagaya, S.; Taketani, Y.; Kamiya, A.; Ando, J. Involvement of Cell Surface ATP Synthase in Flow-Induced ATP Release by Vascular Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H1646–H1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakaki, N.; Nagao, T.; Niki, R.; Toyofuku, A.; Tanaka, H.; Kuramoto, Y.; Emoto, Y.; Shibata, H.; Magota, K.; Higuti, T. Possible Role of Cell Surface H+ -ATP Synthase in the Extracellular ATP Synthesis and Proliferation of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2003, 1, 931–939. [Google Scholar]

- Mangiullo, R.; Gnoni, A.; Leone, A.; Gnoni, G.V.; Papa, S.; Zanotti, F. Structural and Functional Characterization of FoF1-ATP Synthase on the Extracellular Surface of Rat Hepatocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2008, 1777, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.-L.; Yan, J.; Yu, Z.-H.; Zhu, C.-Q. Neuronal Cell Surface ATP Synthase Mediates Synthesis of Extracellular ATP and Regulation of Intracellular PH. Cell Biol. Int. 2011, 35, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravera, S.; Bartolucci, M.; Calzia, D.; Morelli, A.M.; Panfoli, I. Efficient Extra-Mitochondrial Aerobic ATP Synthesis in Neuronal Membrane Systems. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 2250–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panfoli, I.; Ravera, S.; Podestà, M.; Cossu, C.; Santucci, L.; Bartolucci, M.; Bruschi, M.; Calzia, D.; Sabatini, F.; Bruschettini, M.; et al. Exosomes from Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Conduct Aerobic Metabolism in Term and Preterm Newborn Infants. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschi, M.; Santucci, L.; Ravera, S.; Bartolucci, M.; Petretto, A.; Calzia, D.; Ghiggeri, G.M.; Ramenghi, L.A.; Candiano, G.; Panfoli, I. Metabolic Signature of Microvesicles from Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells of Preterm and Term Infants. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2018, 12, 1700082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, S.; Signorello, M.G.; Bartolucci, M.; Ferrando, S.; Manni, L.; Caicci, F.; Calzia, D.; Panfoli, I.; Morelli, A.; Leoncini, G. Extramitochondrial Energy Production in Platelets. Biol. Cell 2018, 110, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, S.; Signorello, M.G.; Panfoli, I. Platelet Metabolic Flexibility: A Matter of Substrate and Location. Cells 2023, 12, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Xi, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. The Role of Mitochondria-Associated ER Membranes in Disease Pathology: Protein Complex and Therapeutic Targets. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1629568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.P.; Tiwari, A.; Singh, N.; Gautam, D.; Sonkar, V.K.; Agarwal, V.; Dash, D. Aerobic Glycolysis Fuels Platelet Activation: Small-Molecule Modulators of Platelet Metabolism as Anti-Thrombotic Agents. Haematologica 2019, 104, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.P.; Ekhlak, M.; Dash, D. Energy Metabolism in Platelets Fuels Thrombus Formation: Halting the Thrombosis Engine with Small-Molecule Modulators of Platelet Metabolism. Metabolism 2023, 145, 155596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibibula, M.; Naseem, K.M.; Sturmey, R.G. Glucose Metabolism and Metabolic Flexibility in Blood Platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 2300–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, S.; Bartolucci, M.; Cuccarolo, P.; Litamè, E.; Illarcio, M.; Calzia, D.; Degan, P.; Morelli, A.; Panfoli, I. Oxidative Stress in Myelin Sheath: The Other Face of the Extramitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation Ability. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 1050962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.I.; Edelstein, D.; Du, X.L.; Brownlee, M. Hyperglycemia Potentiates Collagen-Induced Platelet Activation through Mitochondrial Superoxide Overproduction. Diabetes 2001, 50, 1491–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewiera, K.; Kassassir, H.; Talar, M.; Wieteska, L.; Watala, C. Higher Mitochondrial Potential and Elevated Mitochondrial Respiration Are Associated with Excessive Activation of Blood Platelets in Diabetic Rats. Life Sci. 2016, 148, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, L.; Tancreda, G.; Iobbi, V.; Caicci, F.; Bruno, S.; Esposito, A.; Calzia, D.; Benini, S.; Bisio, A.; Manni, L.; et al. The Flavone Cirsiliol from Salvia x Jamensis Binds the F1 Moiety of ATP Synthase, Modulating Free Radical Production. Cells 2022, 11, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmat, U.; Abad, K.; Ismail, K. Diabetes Mellitus and Oxidative Stress—A Concise Review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.D. Mitochondrial Generation of Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide as the Source of Mitochondrial Redox Signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 100, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, L.; Li, H.; Lai, Y.T.; Wei, X.; Xu, X.; Cao, Z.; Cao, H.; Wan, Q.; Chang, Y.Y.; et al. Mitochondrial ATP Synthase as a Direct Molecular Target of Chromium(III) to Ameliorate Hyperglycaemia Stress. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.O.; Genoux, A.; Ferrières, J.; Duparc, T.; Perret, B. Serum Inhibitory Factor 1, High-Density Lipoprotein and Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2017, 28, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).