Abstract

Mass production in product design typically relies on standardized geometries and dimensions to accommodate a broad user population. However, when products are required to interface directly with the human body, such generalized design approaches often result in inadequate fit and reduced user comfort. This limitation highlights the necessity of fully personalized design methodologies based on individual anthropometric characteristics. This paper presents a novel application that automates the design of custom-fit sunglasses through the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Computational Design. The system is implemented using both textual (Python™ version 3.10.11) and visual (Grasshopper 3D™ version 1.0.0007) programming environments. The proposed workflow consists of the following four main stages: (a) acquisition of user facial images, (b) AI-based detection of facial landmarks, (c) three-dimensional reconstruction of facial features via an optimization process, and (d) generation of a personalized sunglass frame, exported as a three-dimensional model. The application demonstrates a robust performance across a diverse set of test images, consistently generating geometries that conformed closely to each user’s facial morphology. The accurate recognition of facial features enables the successful generation of customized sunglass frame designs. The system is further validated through the fabrication of a physical prototype using additive manufacturing, which confirms both the manufacturability and the fit of the final design. Overall, the results indicate that the combined use of AI-driven feature extraction and parametric Computational Design constitutes a powerful framework for the automated development of personalized wearable products.

1. Introduction

Technological developments in recent years have brought wearable products into the discussion. Safety, improvement of lifestyle, and product life are three of the most important characteristics of these products [1,2]. The application of wearable products is found in the fields of medicine, security, and entertainment [3]. A key purpose of wearables is to combine aesthetics and usability [4]. Computational Design is a process that combines design with programming tools. The role of a designer is not simply to develop a product, but to program the steps needed to make it again [5,6,7]. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has significantly changed the way computer science operates. According to the literature, AI is referred to as the science and engineering of building intelligent machines and, by extension, intelligent software [8]. A large part of the way AI operates is based on the way the human brain works in relation to its environment (e.g., understanding and solving a problem, learning from mistakes, making decisions based on external data, etc.) [9,10]. Machine Learning (ML) is one of the fundamental pillars of AI. More specifically, ML searches for complex patterns and relationships within the data given. Other fundamental pillars are Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Deep Learning (DL), Generative Design (GD), Genetic Algorithms (GAs), etc. [11,12].

In the field of product design, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly being integrated into both the design and production stages. In industries such as automotive manufacturing and fashion, AI is incorporated across all stages of the product lifecycle, including design, production, inventory management, customer service, and sales [13]. Chikwendu and Emeka examine the benefits of integrating AI into product design processes that support mass customization [14]. Witkowski and Wodecki analyze the challenges, applications, and success factors associated with the integration of AI into product design. Their research is based on interviews with twelve experts from the information technology sector. The findings indicate that AI is predominantly used as a daily support tool, while emphasizing the importance of data security and privacy considerations. Furthermore, the quality of the development team and the availability of appropriate data have been identified as critical factors influencing the successful integration of AI into product development processes [15]. In graph-based design models, designers can incorporate fundamental design principles such as color harmony, balance, and symmetry. Rather than replacing the designer’s role, AI acts as an assistive tool that enhances and extends human creativity throughout the design process [16,17].

Computational Design is employed to automate a series of repetitive steps within the design process. Parametric design, as an integral component of Computational Design, addresses the challenge of generating multiple design solutions through a unified programming framework [18,19]. Research on eyeglass design using Computational Design focuses on managing data that describes the unique characteristics of each individual’s facial geometry and incorporating this information into the design process. Such data can be acquired through various methods, including direct dimensional measurements, facial photography, and three-dimensional (3D) facial scanning [20,21,22]. Zhou et al. develop a Computational Design system that analyzes facial proportions to automate the eyeglass design process [23]. Huang et al. introduce an application that enables users to modify eyeglass shape parameters, while visualizing the frames on their own faces in real time using AR technology [24]. Additive manufacturing represents one of the most common methods for evaluation and physical testing. The most widely adopted 3D printing techniques for this purpose are Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA) [25,26,27,28]. There has been a lot of discussion in recent years about the reinforcement of thermoplastic polymers with fibers of various materials. These fibers can be composed of natural materials, resulting in the creation of more sustainable and ecological composite materials. Ahmad et al. analyze the mechanical, thermal, and physical properties of composite materials after the addition of natural fibers [29].

Optimization techniques such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can be employed to optimize geometries or datasets that underpin product development processes [30]. One significant improvement that can be introduced during product development is shape alignment. Numerous studies in the literature have focused on the development of algorithms for aligning digital facial representations generated from user data [31,32,33,34].

In the present study, an application for the automated design of customized eyeglasses was developed by integrating Artificial Intelligence techniques with Computational Design methodologies. The application processes user-provided facial images and employs AI-based feature detection to identify key anthropometric landmarks, which are subsequently stored as three-dimensional spatial coordinates. A Genetic Algorithm (GA) is then utilized to optimize the correspondence of feature points across multiple images, ensuring a robust reconstruction of the user’s facial geometry. This paper fills the research gap found in the literature review regarding the product automation framework for sunglasses. The innovation of this study is the combination of AI and computational design for the development of a new product. The result of this framework is reductions in cost and time in combination with mass customization, which are important features of modern Industry 4.0. The resulting sunglass frame design was evaluated both digitally (via virtual fitting) and physically through 3D-printed prototypes. The implementation was carried out using textual and visual programming (Python™ and Grasshopper 3D™). This work contributes a novel AI-driven, parametric design pipeline that automates the full cycle of personalized eyewear generation—from anthropometric data acquisition and multi-view facial reconstruction to frame optimization and prototype validation.

2. Materials and Methods

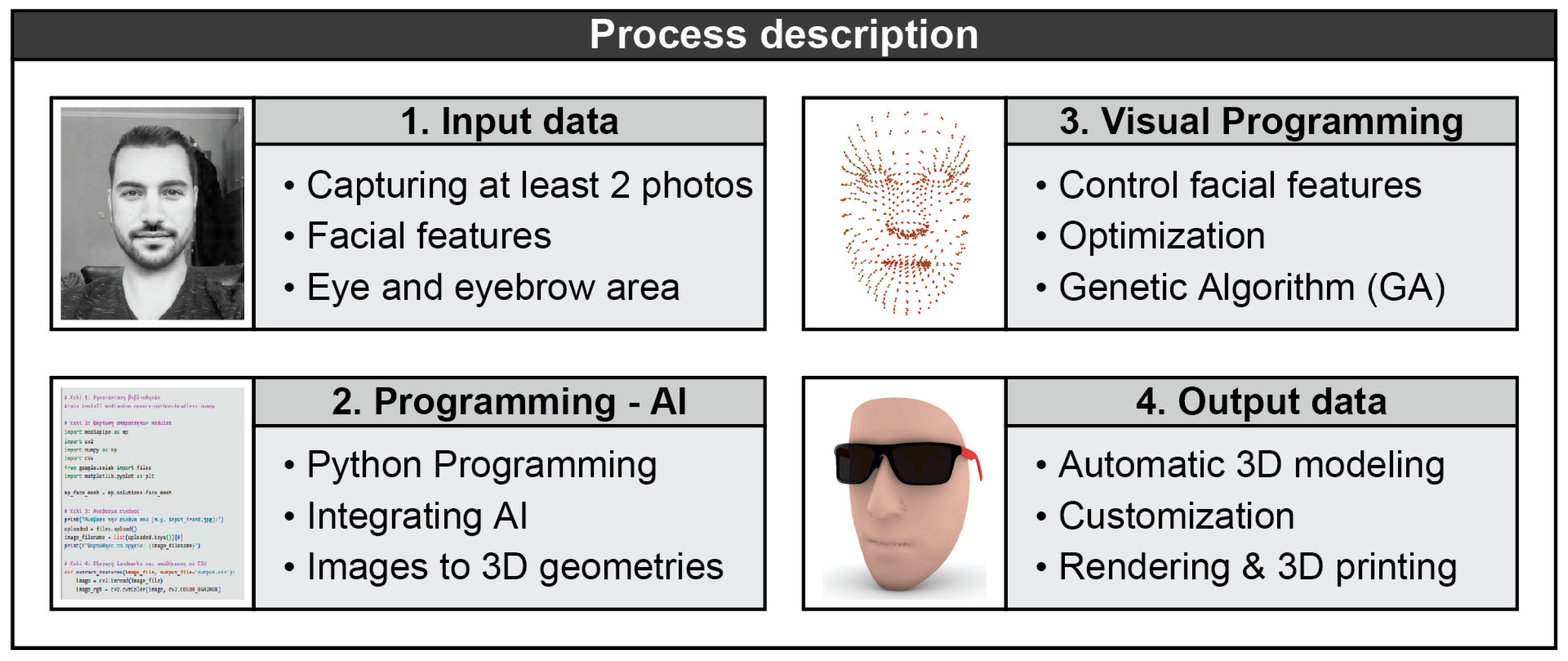

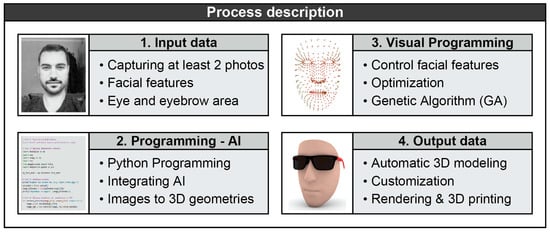

The primary objective of this study is the development of a custom sunglasses design application. The proposed application integrates Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Computational Design tools to automate the various stages of the design process. The system is structured into the following four main levels: (1) Input Data, (2) Programming–AI, (3) Visual Programming, and (4) Output Data. At the first level, the user captures between one and five selfie-type photographs. These images must focus on the facial region and clearly display key facial features. Slight variations in the viewing angle between photographs are required, as they enhance the accuracy of the design process. At the second level, facial features are identified using AI-based methods. Feature recognition is performed simultaneously across all input images. Facial features are represented as sets of points in three-dimensional (3D) space, with each set corresponding to an individual photograph. At the third level, alignment is carried out among all point sets. This alignment is achieved through an optimization-based algorithm, which is described in detail in the following section. At the fourth level, the sunglasses design process is fully automated. The geometry of the frames is generated based on the proportions of the user’s facial features. In parallel, rendering processes—including material assignment, texturing, and lighting—are applied, and a digital fitting of the sunglasses onto the reconstructed 3D facial model is performed. Figure 1 illustrates the four stages of the proposed design application, along with representative images corresponding to each stage.

Figure 1.

Design process development.

2.1. Workflow

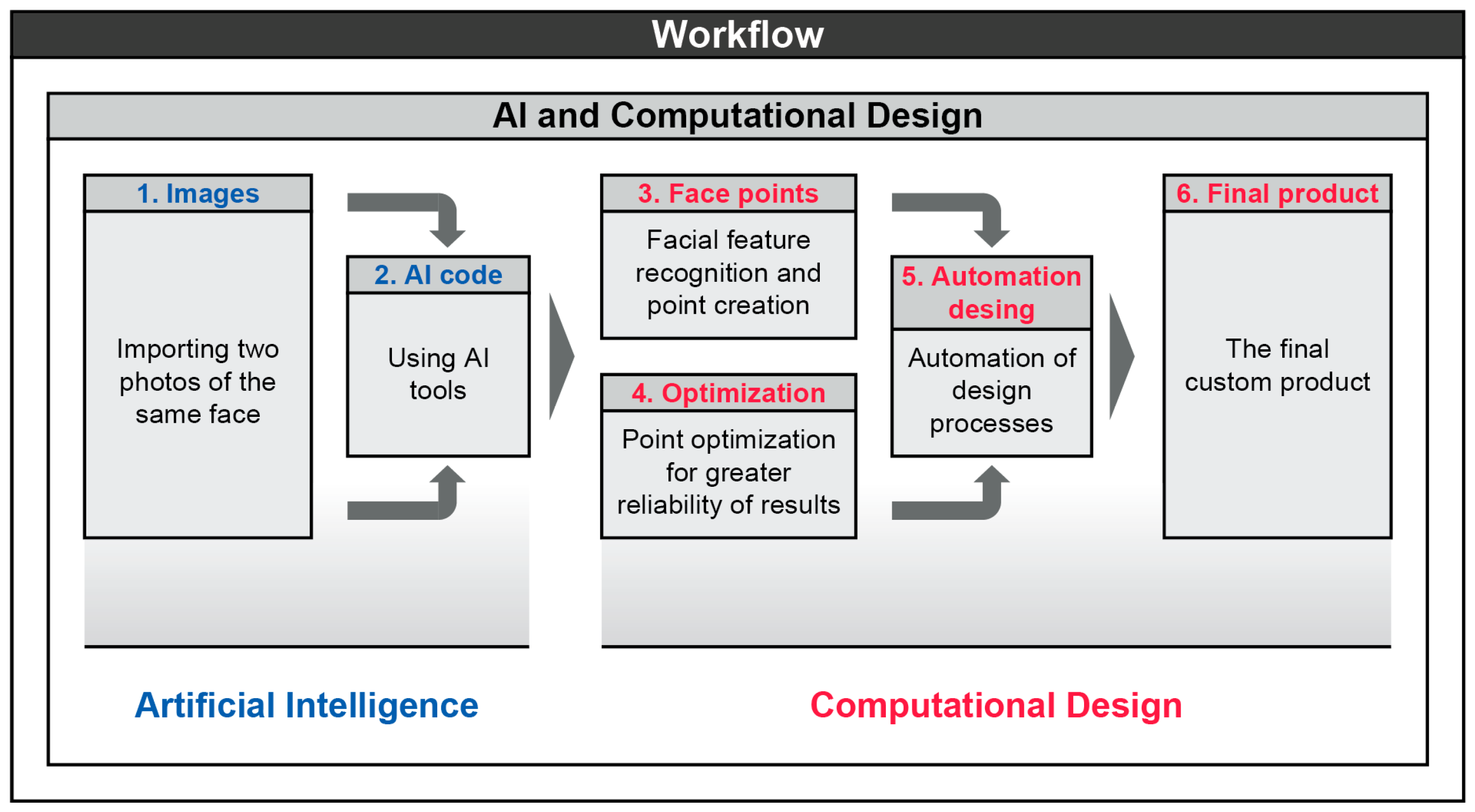

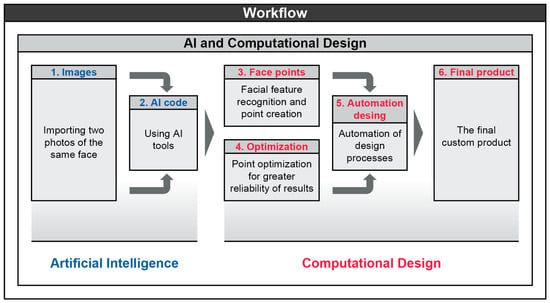

At this stage, the tools and workflow of the proposed design application are described. The operation of the application is structured around two main pillars. The first pillar is based on Artificial Intelligence (AI) implemented through Python™, while the second pillar relies on Computational Design using Grasshopper 3D™. Within the first pillar, the Python™-based AI module processes facial images and converts them into three-dimensional (3D) point representations. Once the generation of 3D point data is completed, the workflow transitions to the second pillar. The extracted 3D point coordinates are imported into Grasshopper 3D™ as a list of spatial coordinates and reconstructed as points within the parametric design environment. An optimization algorithm is then applied to align the point sets obtained from the different images. Through this optimization process, the individual point sets converge, resulting in a single consolidated set of points that integrates information from all input photographs. This final point cloud accurately represents the user’s facial features and is subsequently classified according to anatomical regions. Through this classification and filtering process, points corresponding to critical facial areas that approach or come into contact with the eyeglass frame are identified and isolated. Based on these filtered facial features, the eyeglass frame is generated using parametric design tools in Grasshopper 3D™, enabling the fully automated design of the final product. Figure 2 illustrates the two main pillars (AI and Computational Design) and the six stages of the workflow, as follows: image acquisition, AI processing, facial point generation, optimization, automated design, and final product output.

Figure 2.

Artificial Intelligence and Computational Design workflow.

The PythonTM code (v 3.10.11) was developed in ThonnyTM (v 4.1.7), which is a free Integrated Development Environment (IDE). The code used the libraries mediapipeTM (v 0.10.21), cv2TM (v 4.11.0), numpyTM (v 1.26.4), csvTM (v 1.0), matplotlib.pyplotTM (v 3.10.7), tkinterTM (v 8.6), and osTM (v 3.10.11). The algorithm developed consists of the following four main stages:

- Image input: In the first stage, the application user is required to provide the images into the algorithm. The supported images are in JPG and PNG format.

- Facial feature recognition: Through the MediaPipeTM library (v 0.10.21), the algorithm identifies facial features according to landmarks such as eyes, nose, etc.

- Three-dimensional point extraction: The first result of the algorithm is the extraction of the points in X, Y, Z coordinates in CSV file format, saving them locally on the computer.

- Grid visualization: The second result of the algorithm is the appearance of the 3D grid on the user’s face in image format. These images are a way of performing preliminary evaluation of the recognition of facial features. If the result is not correct, the user must repeat the process of taking photography and importing the process.

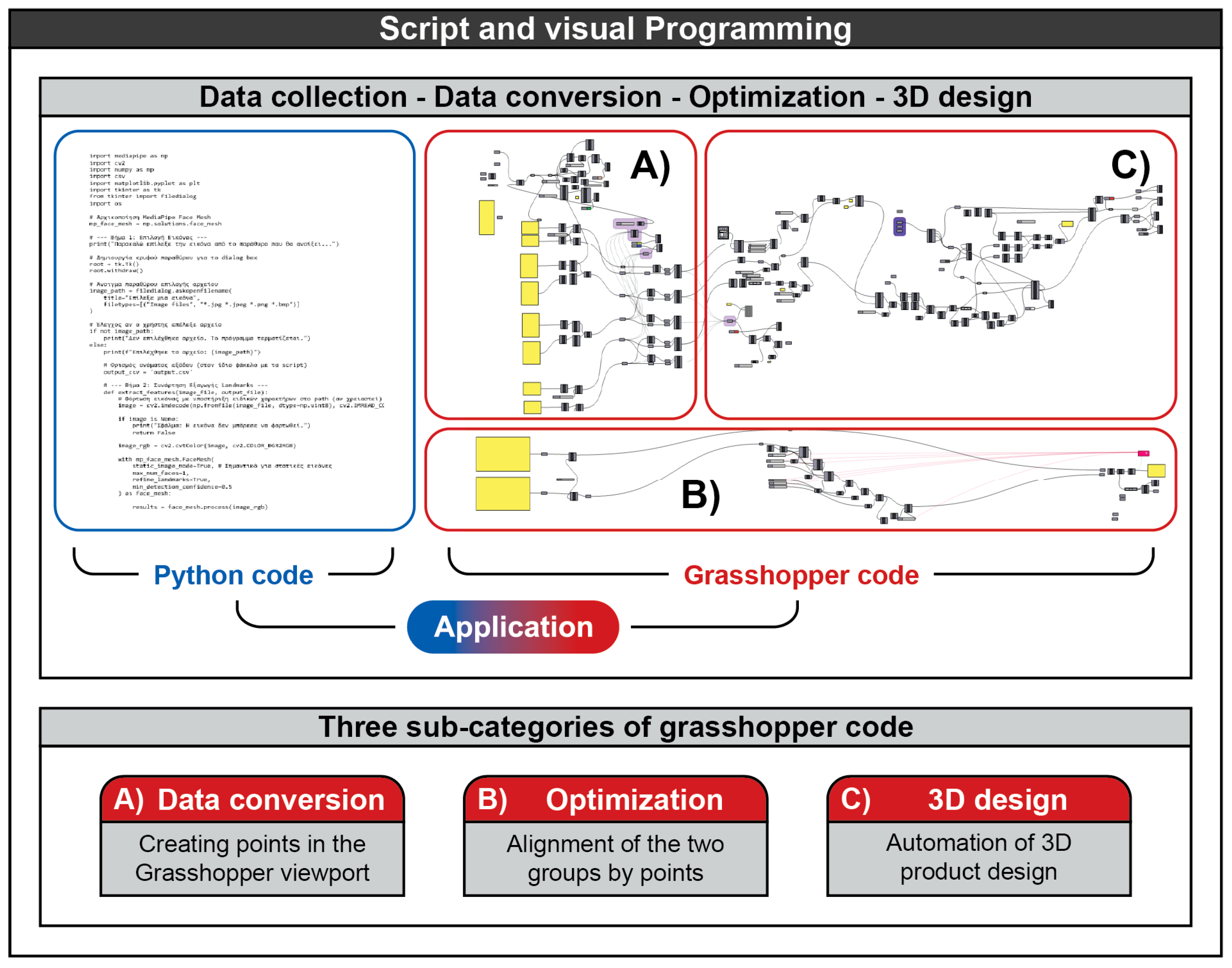

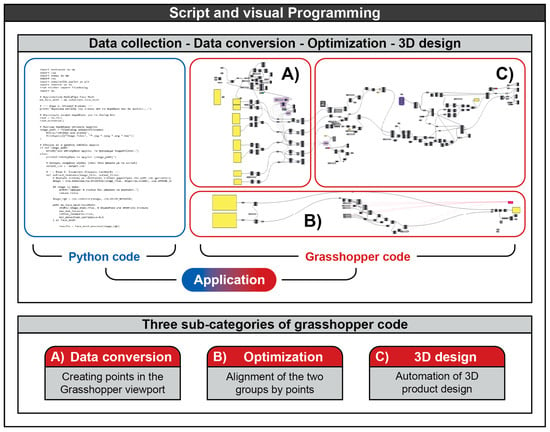

The result of the points in CSV format is the data from which the use of Grasshopper 3DTM (v 1.0.0007) starts. The visual programming in Grasshopper 3DTM consists of a total of 117 nodes and the following three subcategories:

- (A)

- Data conversion: The first subcategory focuses on converting the csv file into 3D points in the software environment. The points are organized into groups corresponding to each original photo.

- (B)

- Optimization: The second subcategory moves the organized sets of points so as to match the visual angles of the face with each other. The movement process includes movements and rotations of each set of points in X, Y, and Z axes. Using an optimization algorithm, the optimal position of the sets is obtained, from which a final single set of points is obtained. The final set of points describes the proportions and curves of the real face as best as possible.

- (C)

- Three-dimensional design: The third subcategory aims to custom design the sunglasses based on the dimensions and proportions of the face.

Figure 3 shows the text code and the visual code, as well as their subcategories.

Figure 3.

Overview of two programming codes.

2.2. Facial Feature Recognition

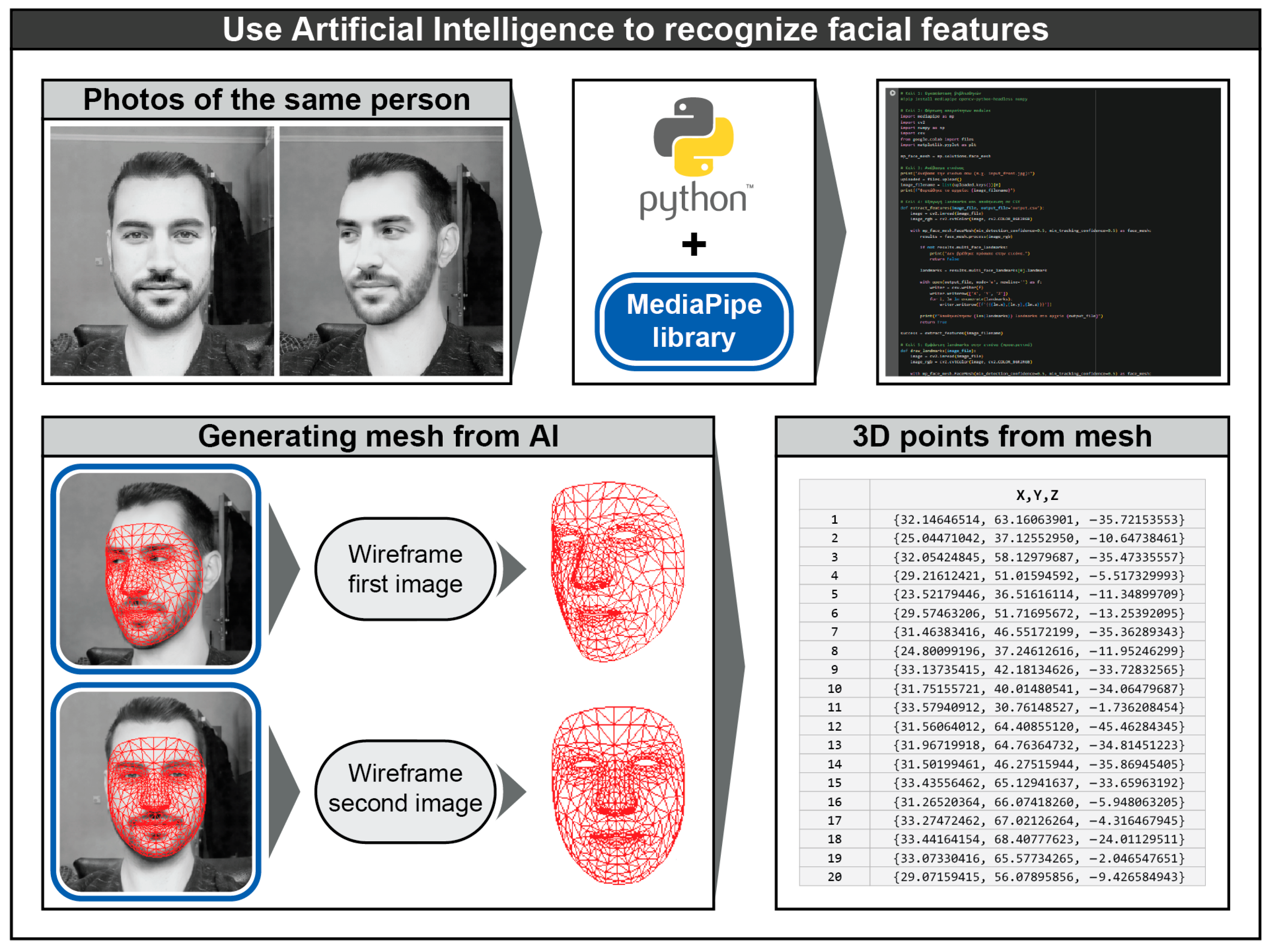

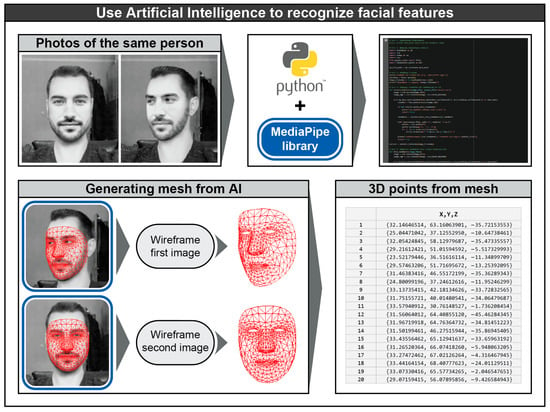

This section presents the PythonTM code and the input data in detail. Photographs of a real user were used to evaluate the design application. As mentioned above, the photographs had to clearly contain facial features. Figure 4 shows the two photographs of the user from different angles. Image processing and feature recognition were based on the MediaPipeTM library. MediaPipeTM is an open-source library from GoogleTM [35]. Some of the functions of MediaPipeTM are face, expression, posture, hand, object recognition, and real-time usage. In most functions, a grid is developed that describes the recognized feature [36,37,38,39]. The PythonTM code handles user input through a file selection window; this process is performed using the tkinterTM library commands. Each file is checked for validity so that the process can continue. If the file has a problem, the file selection window is displayed again. The main part of the code is executed through the recognize_features() function. This function includes the MediaPipeTM Face Mesh model configured to recognize the face through landmark points. If face recognition is successful, the data extraction process begins. However, if the recognition is not successful, the process starts again from the file selection window. The last step before data extraction is the execution of the draw_landmarks function. Through this function, the original photo is displayed with the 3D mesh overlay (using the OpenCVTM version 4.11.0 and MatplotlibTM version 3.10.7 libraries). At this point, the user can qualitatively evaluate the success of the recognition of the facial features and is given the option to continue or repeat the process. At the end of the code, the coordinates of the points are exported in CSV format according to a specific formatting. The formatting is presented through three examples (1).

Figure 4.

Processing input data with Artificial Intelligence.

Figure 4 shows the two initial photos that were entered into the code. It also shows the result of the 3D mesh overlay, which is qualitatively evaluated by the user, and an indicative portion of the total 3D points that are extracted.

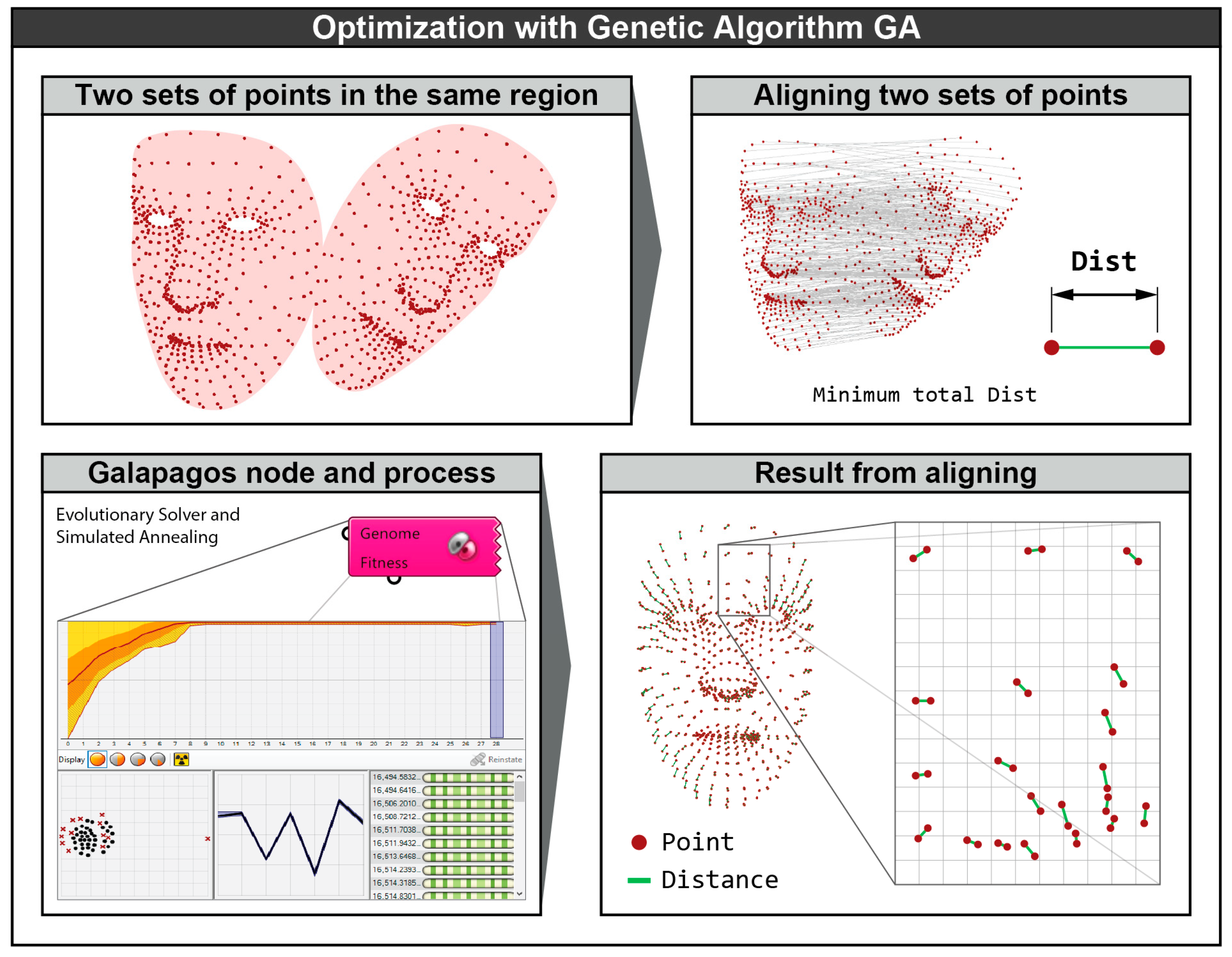

2.3. Point Optimization

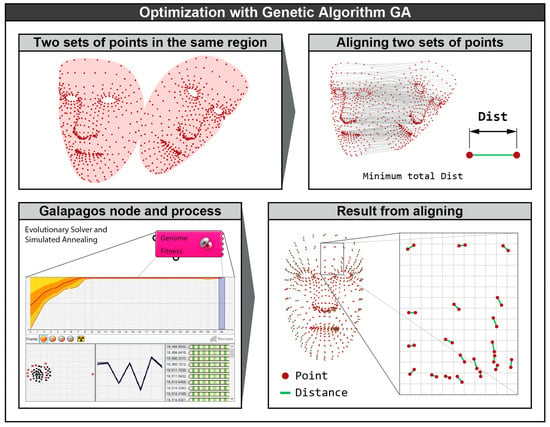

The remaining stages of the workflow are implemented through Computational Design in Grasshopper 3D™. The coordinate sets obtained from the previous stage are converted into three-dimensional (3D) points and visualized in the Rhino™ 3D viewport. Initially, the point sets are positioned irregularly in space, as the facial recognition process does not provide spatial orientation information. Figure 5 illustrates the initial spatial configuration of two point sets. The indexing order of the points is preserved within each set, ensuring that every point in the first set corresponds directly to its counterpart in the second set. For each corresponding pair of points, a connecting line is generated, and its length is defined as Dist. The value of Dist is influenced by the relative translation, rotation, and scaling of one point set with respect to the other. Consequently, the following seven transformation variables are introduced: (1) translation along the X-axis (mx), (2) translation along the Y-axis (my), (3) translation along the Z-axis (mz), (4) rotation about the X-axis (rx), (5) rotation about the Y-axis (ry), (6) rotation about the Z-axis (rz), and (7) uniform scaling (sxyz). Scaling is constrained to be uniform to prevent distortion of the point set, which would otherwise alter the proportional relationships between facial features. Uniform scaling preserves these proportions while allowing the overall size to be adjusted, as final dimensional calibration is performed in later stages of the process. The objective of the alignment procedure is to minimize the sum Σ of all Dist values after the transformation of the point sets. To solve this optimization problem, the Galapagos™ solver within Grasshopper was employed. Galapagos™ is an optimization engine that iteratively modifies input variables and evaluates their effect on a predefined objective function, which can be either maximized or minimized depending on the problem formulation. In the present case, the objective function is the minimization of Σ(Dist). Galapagos™ repeatedly evaluates new combinations of transformation variables until convergence toward an optimal solution is achieved. In the example presented, Galapagos™ required 3 min and 12 s to determine the optimal values for the seven transformation variables. Notably, within the first 40 s, the solution had already converged to 98.87% of the final optimal value. The optimization was performed using a Genetic Algorithm (GA), which is inspired by the principles of natural selection and biological evolution. For comparison, a Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm was also tested, but it required significantly longer computation times to reach a comparable solution [40]. Figure 5 presents the Galapagos™ interface during execution, along with the resulting alignment of the two point sets. The green lines represent the Dist values, whose midpoints are retained as representative points to describe facial geometry with increased accuracy. When additional photographs are available and multiple point sets are generated, the alignment procedure is repeated for each set, keeping the first set fixed while sequentially aligning all others to it.

Figure 5.

Point location optimization algorithm.

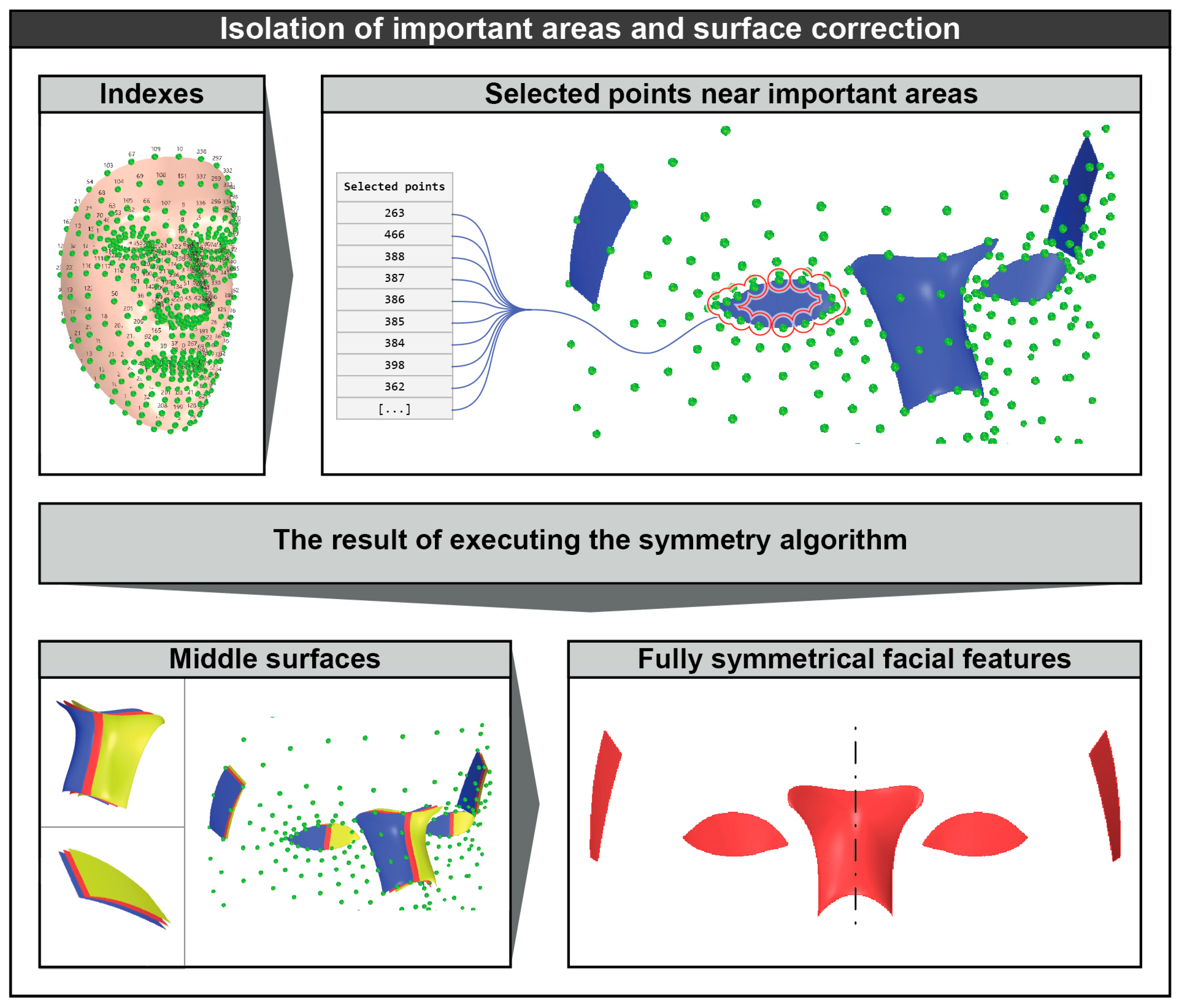

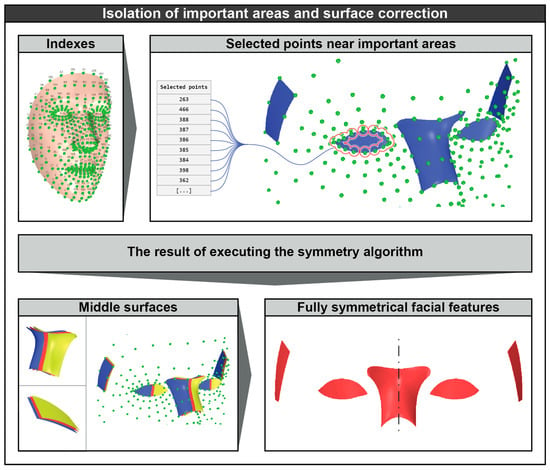

2.4. Managing Significant Areas

The outcome of the optimization process is a single consolidated point set, in which each point represents the average position derived from the corresponding points of the aligned sets. Each point in the final set retains a specific and fixed index, as illustrated in Figure 6. For the design of sunglasses based on facial features, it is necessary to identify and isolate geometrically significant facial regions. In this study, the key regions are defined as follows: (a) the nasion, corresponding to the curvature of the upper part of the nose; (b) the eye region, including the outline and curvature of the eye; and (c) the temple region, located adjacent to the eye where the eyeglass frame makes contact with the face. The point indices describing these significant regions remain constant, as they are generated by MediaPipe™. Figure 6 presents the separation of significant and non-significant facial regions. Specifically, the indices 263, 466, 388, 387, 386, 385, 384, 398, 362, 249, 390, 373, 374, 380, 381, and 382 correspond to the outline of the right eye, while other critical facial regions are defined in an analogous manner. A common challenge in user-centered product design is the treatment of symmetry. When a product is intended to fit an individual user, strict symmetry is difficult to apply, as the human body inherently exhibits asymmetries and imperfections between corresponding features (e.g., left and right ears). In the case of eyeglasses, the product must remain geometrically symmetrical for design consistency, manufacturability, and aesthetic considerations, while simultaneously achieving a close fit to the user’s unique facial morphology. In this study, the eyeglasses were designed to be fully symmetrical; however, geometric information from both sides of the face was preserved during the design process. Specifically, all facial features were symmetrized by generating mid-surfaces, resulting in a unified dataset that represents both sides of the face. In Figure 6, the blue surfaces correspond to the left facial features, the yellow surfaces to the right facial features, and the red surfaces represent the generated mid-surfaces.

Figure 6.

Refinement of important surfaces.

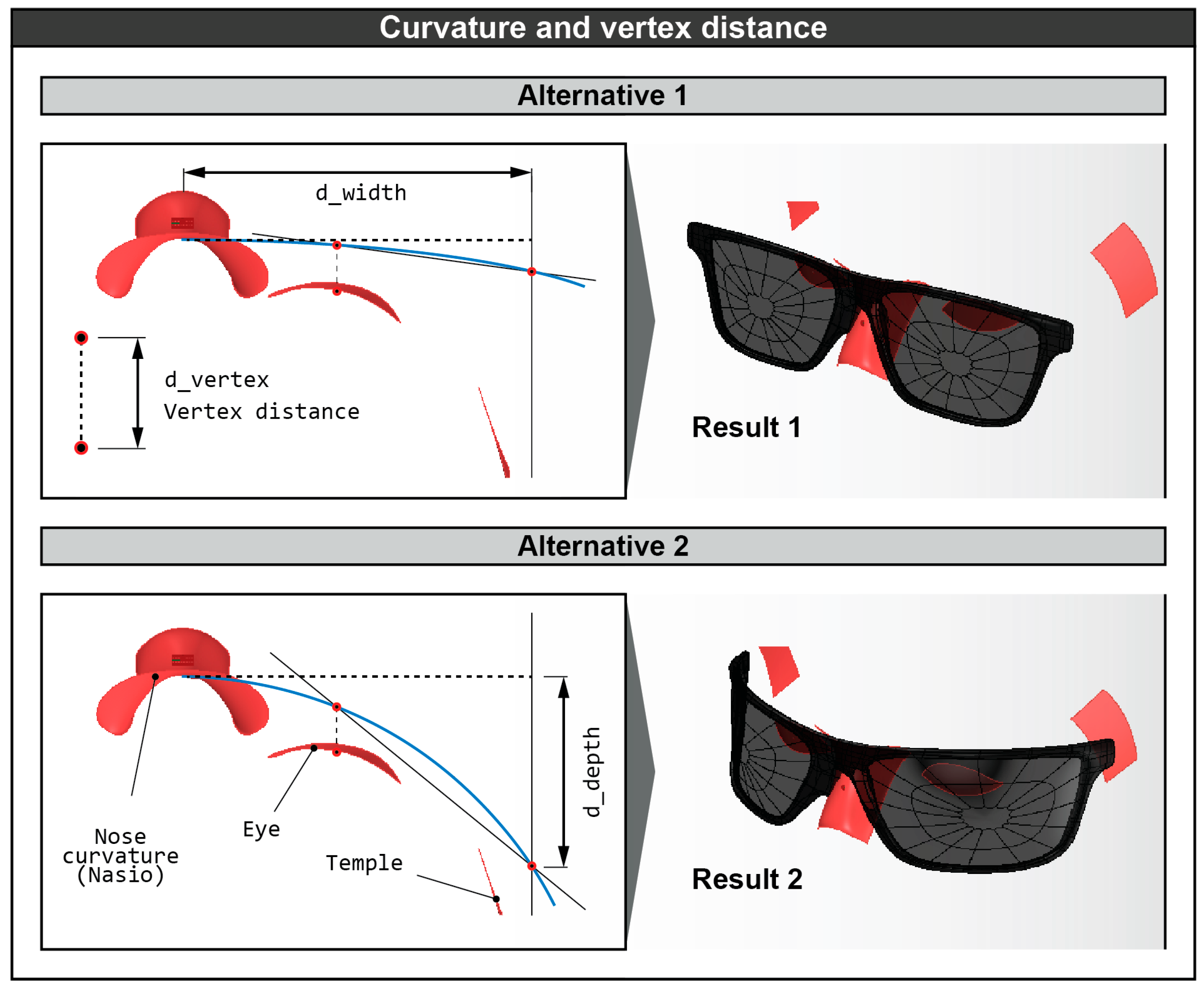

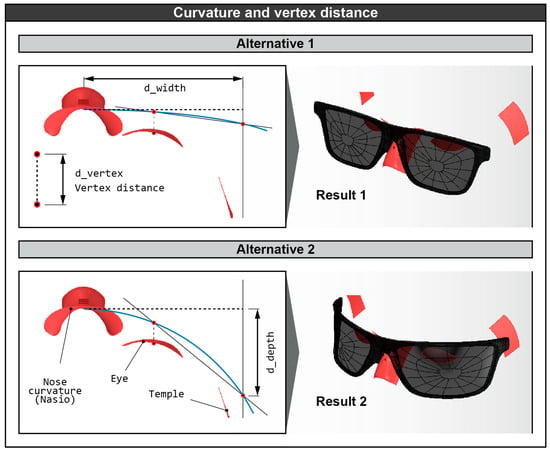

2.5. Definition of Variable Dimensions

The study continued using half of the facial features, as they were made symmetrical. There is a 3D geometry from which the design process starts, as follows: d_width, d_vertex, and d_depth. The d_width dimension describes the distance from the top of the nose to the temple area, which is outside the eye. The d_vertex dimension describes the distance between the eye and the lens of the glasses. The d_depth dimension describes the vertical distance between the top of the nose and the corner of the glasses frame. The d_vertex dimension is the only fixed dimension, with a value of 12 mm, as according to the literature, 12 mm is the average and most common dimension used in glasses design [41]. Based on the fixed d_vertex and the use of an arc, d_depth is calculated. The result of this process is that if the depth of the eye or the width of the face changes, then the algorithm will adapt to the new data. The curve of the arc is the result of this process with which the design continues. Figure 7 shows the dimensions d_width, d_vertex, d_depth, and the curve of the arc with two variations. In each variation, a different depth of the eye is used in relation to the reference point (upper part of the nose). At the same time, the 3D result of the geometry of the glasses of each variation is presented.

Figure 7.

Automatic design mechanism based on distances and points.

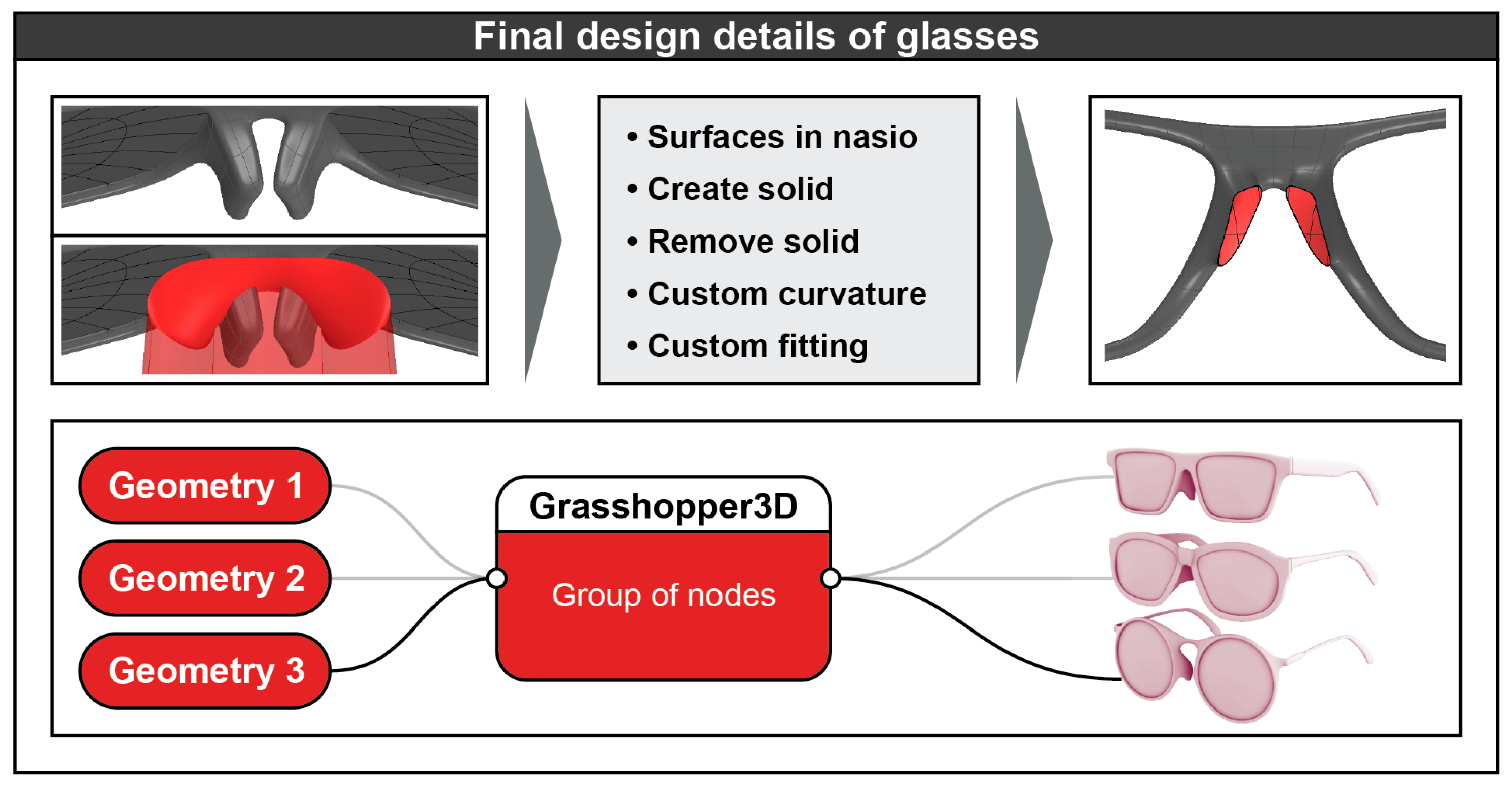

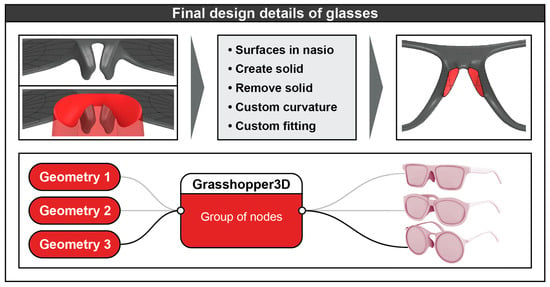

2.6. Sunglasses Design

The design of the sunglasses geometry was carried out through Computational Design in Grasshopper 3DTM. Computational Design helps automate the design process through the execution of predefined commands. The geometry was based on the variable dimensions d_width, d_vertex, and d_depth and was developed with 3D modeling tools. It was necessary to perform joints, sections, and subtractions between volumes to develop the final result. In the area where the glasses frame touched the upper part of the nose, volume subtraction had to be performed. This specific subtraction concerns the curvature of the nose surface so that the glasses touch (fit) exactly on the face of each user. In parallel with the design process, the user can choose between different styles of glasses frames. The choice of use is automatically parameterized by the algorithm and produced as a 3D file in STEP format. Figure 8 shows the creation of a custom surface in the contact area of the glasses with the nose, as well as the assorted styles of glasses frames.

Figure 8.

Glasses design completion and alternatives.

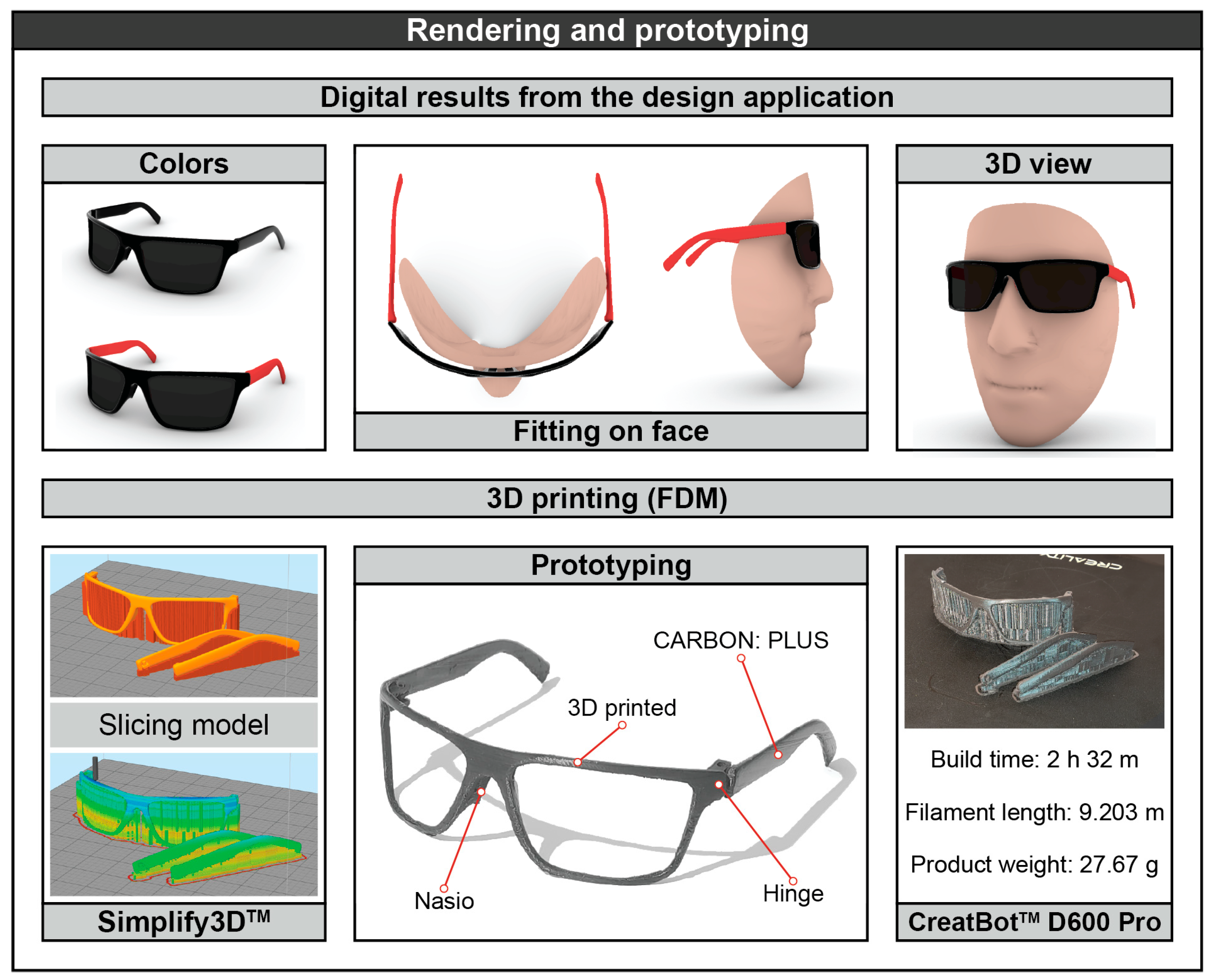

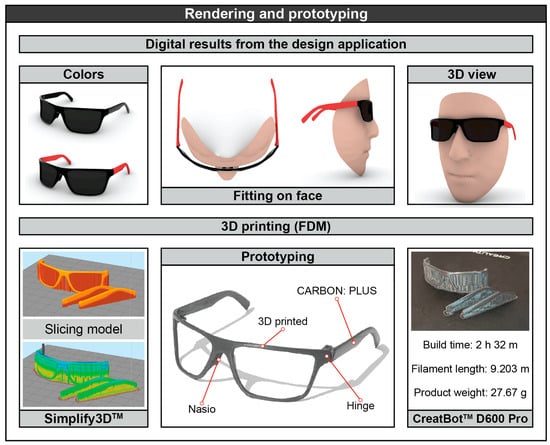

In the last stage of the design application, the sunglasses are placed in a digital studio and photorealization is performed. Using textures and lighting, various photographs of the final product are automatically produced. Figure 9 shows the digital results of the design application. To complete the present study, a prototype is manufactured using additive manufacturing. The 3D printer used is the CreatBotTM D600 Pro (Henan Creatbot Technology Limited, Zhengzhou, China). This printer is an FDM type with dimensions of 600 mm × 600 mm × 600 mm. The material chosen is CARBON: PLUS (NEEMA3D™, Athens, Greece), which is a composite material made of PET-G (Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol) reinforced with 20% carbon fiber (Table 1). The printing settings are set according to Table 2. The carbon fibers contained in this material, combined with the optimal printing settings, result in an increase in the strength of the printed product. More specifically, under specific printing conditions, the tensile stress can reach up to 98.48 MPa. Its high strength and ease of printing are both significant advantages of this material compared to other high-strength filaments. The settings were selected according to the investigation of the optimal settings that cause the maximum tensile strength of a printed specimen [42,43].

Figure 9.

Visualization and additive manufacturing (3D printing).

Table 1.

Specifications of the material “CARBON: PLUS”.

Table 2.

Printer settings and description.

3. Results

The slicing software used to generate the G-code is Simplify3DTM version 5.1. In Figure 9, images from the 3D printing prototyping of the sunglasses using the CARBON: PLUS composite material are shown. The design application was tested on four different users. The users’ faces had significant differences between them. No errors occurred when importing the photos. Five photos were captured from each user, with slight differences in the perspective of the face. Using 3D printing, prototype eyeglass frames were manufactured. Each frame was tested by its user with successful application to the face.

A technical difficulty that arose after the prototype was built is in the hinge area. The friction of the material is high, which may require changes either in terms of design or in terms of different materials in the area. The final prototype was photographed in a studio with appropriate lighting, as shown below. Each prototype took 2 h and 32 min to print and 9.2 m of filament was used. The weight of the printed skeleton was estimated at 27.67 g.

The final stage of this study involved a preliminary user evaluation. Four participants were asked to assess five characteristics after using the customized eyeglass frames. The evaluated characteristics were (a) anatomical fit, (b) stability, (c) perceived weight, (d) visual satisfaction, and (e) ease of use. Each characteristic was rated using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 represents the lowest rating and 5 the highest. The results indicate that the application of the eyeglasses to the users’ faces did not cause any discomfort or functional issues. Participants perceived the frames as lightweight, which is a critical attribute for products intended for prolonged use. Table 3 summarizes the evaluation scores for each participant, along with the corresponding average values for each evaluated characteristic.

Table 3.

Early evaluation results.

4. Conclusions

This study presents the development of a custom eyewear design application leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools. The application accepts a set of user facial photographs as input and subsequently performs the design process automatically. This process includes facial feature recognition, generation of 3D points corresponding to facial features, optimization of these points, and automated product design tailored to the user’s facial geometry. The system was implemented using textual programming in Python™ and visual programming in Grasshopper 3D™, with point optimization performed using Galapagos™. Galapagos™ employs Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Simulated Annealing (SA) techniques to solve the optimization problem.

The proposed approach addresses limitations commonly associated with mass production. Personalized design overcomes these challenges by enabling the creation of products that fit individual users precisely. Moreover, the integration of AI enhances both the speed and reliability of applications that automate aspects of product development. The role of the designer is consequently transformed, evolving from manual modeling to oversight and guidance of AI-driven design processes.

Testing of the application with diverse photographic inputs revealed no significant operational difficulties. It was noted, however, that low lighting conditions negatively affected the initial recognition of facial features. Conversely, the use of multiple images captured from different angles improved measurement reliability, as point positions were triangulated across the input dataset.

The contribution of this study to society is the use of mass customization and inclusivity, as the design focuses on human and accessibility. People with deformities or special needs are often not satisfied with the glasses frames that most manufacturers provide. The contribution to the environment directly affects the sustainability of the product. Zero Waste and on-demand production are two important advantages of this study, as it includes 3D printing. Finally, this study contributes to reductions in design time and extension cost, which are two important characteristics of the industry.

Further development of this work will integrate advanced Artificial Intelligence techniques to enable the extraction of additional anthropometric features, such as ear position and curvature. Incorporating a richer set of data will allow the sunglasses design process to represent the full spectrum of the product more accurately, including user interaction. A limitation of the present study is the small sample size of people who tested the glasses. In future studies, the number of participants for testing the application will increase, as more facial features will need to be analyzed and evaluated. A promising direction for future research is the implementation of AI-based facial-shape classification, which would enable the system to recommend appropriate frame styles tailored to a user’s facial morphology. Finally, the use of Augmented Reality (AR) technologies could facilitate pre-prototype geometric evaluation, thereby reducing both the cost and the overall duration of the design and development process. This application combines the requirements of modern industry with mass customization. The symmetry of the product both in terms of construction and aesthetics plays an important role. In the future, the design application could also evolve into the design of asymmetrical products for very specialized cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M., A.T., K.D. and P.K.; Methodology, P.M., A.T., K.D. and P.K.; Software, P.M., A.T., K.D. and P.K.; Validation, P.M., A.T. and P.K.; Formal analysis, P.M., K.D. and P.K.; Investigation, P.M., A.T. and P.K.; Resources, P.K.; Data curation, P.M., A.T., K.D. and P.K.; Writing—original draft, P.M. and P.K.; Writing—review & editing, A.T. and P.K.; Visualization, P.M., A.T., K.D. and P.K.; Supervision, P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Minaoglou, P.; Efkolidis, N.; Manavis, A.; Kyratsis, P. A review on wearable product design and applications. Machines 2024, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Chien, C.F.; Kerh, R. UNISON framework of data-driven innovation for extracting user experience of product design of wearable devices. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 99, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, V.G.; Caine, K. Human factors considerations in the design of wearable devices. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2014, Adelaide, Australia, 17–19 November 2014; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 58, pp. 1820–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Pateman, M.; Harrison, D.; Marshall, P.; Cecchinato, M.E. The role of aesthetics and design: Wearables in situ. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Manavis, A.; Kakoulis, K.; Kyratsis, P. A brief review of computational product design: A brand identity approach. Machines 2023, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Jiang, P.; Zang, T.; Liu, Y. Data-driven intelligent computational design for products: Method, techniques, and applications. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2023, 10, 1561–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaoglou, P.; Kakoulis, K.; Manavis, A.; Kyratsis, P. Computational wearables design: Shoe sole modeling and prototyping. Int. J. Mod. Manuf. Technol. (IJMMT) 2023, 15, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. What Is Artificial Intelligence. 2007. Available online: https://cse.unl.edu/~choueiry/S09-476-876/Documents/whatisai.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Boucher, P. Artificial Intelligence: How Does It Work, Why Does It Matter, and What Can We Do about It? 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/641547/EPRS_STU(2020)641547_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Russell, S.J.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haenlein, M.; Kaplan, A. A brief history of artificial intelligence: On the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, V.; Cascella, M.; Cutugno, F.; Russo, M.; Lanza, R.; Compagnone, C.; Bignami, E. Understanding basic principles of artificial intelligence: A practical guide for intensivists. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2022, 93, e2022297. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A. Product Design and Development Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) Techniques: A Review. engrXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikwendu, O.C.; Emeka, U.C. Artificial Intelligence Applications for Customized Products Design in Manufacturing. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 2025, 6, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski, A.; Wodecki, A. An exploration of the applications, challenges, and success factors in AI-driven product development and management. Found. Manag. 2024, 16, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingwen, W. Research on personalized art design and customized product development driven by artificial intelligence. Int. J. High Speed Electron. Syst. 2025, 35, 2540502. [Google Scholar]

- Minaoglou, P.; Tzotzis, A.; Efkolidis, N.; Kyratsis, P. Integrating Artificial Intelligence into the Shoe Design Process. Eng. Proc. 2024, 72, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, I.; Santos, L.; Leitão, A. Computational design in architecture: Defining parametric, generative, and algorithmic design. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenders, J.L. Next generation parametric design. J. Int. Assoc. Shell Spat. Struct. 2021, 62, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.H.; Wang, I.J.; Wang, J.B.; Luh, Y.P. 3D parametric human face modeling for personalized product design: Eyeglasses frame design case. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 32, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbatón, C.R.; Fernández-Vicente, M.; Conejero, A. Design and 3D printing of custom-fit products with free online software and low cost technologies. A study of viability for product design student projects. In Proceedings of the International Technology, Education and Development Conference 2016, Valencia, Spain, 7–9 March 2016; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2016; pp. 3906–3910. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Huerta, O.; Unver, E.; Allen, J.; Clayton, J.E. A parametric product design framework for the development of mass customized head/face (eyewear) products. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xing, E.; Huang, J. Human-Computer Interaction for the Mass Customization of 3D-Printed Eyewear: Designing an Aesthetically Fitting System and Its Co-creation Services. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2025, Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.H.; Yang, Y.I.; Chu, C.H. Human-centric design personalization of 3D glasses frame in markerless augmented reality. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2012, 26, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, K. Digital design and evaluation for additive manufacturing of personalized myopic glasses. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. 3D Printed Sports Glasses Based on Digital Custom Production. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Intelligent Design (ICID) 2024, Xi’an, China, 25–27 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tsegay, F.; Ghannam, R.; Daniel, N.; Butt, H. 3D printing smart eyeglass frames: A review. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2023, 1, 1142–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Xie, L.; Wang, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X. Producing myopia glasses by 3D printing. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Ishak, M.R.; Yasir, A.S.H.M. Mechanical, thermal and physical properties of natural fiber reinforced composites for 3D printer-fused deposition modeling: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 4063–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Sun, X. Optimizing product design using genetic algorithms and artificial intelligence techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 151460–151475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shen, T.; Huang, X. Approximately global optimization for robust alignment of generalized shapes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 33, 1116–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, W.; Mo, H.; Wang, T.; Yin, S.; Shi, Y.; Wei, S. A face alignment accelerator based on optimized coarse-to-fine shape searching. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 29, 2467–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Liu, L.; Zhu, W.; Yin, S.; Wei, S. Face alignment with expression-and pose-based adaptive initialization. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018, 21, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zeng, D.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, X. Joint face alignment and 3d face reconstruction. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 545–560. [Google Scholar]

- Lugaresi, C.; Tang, J.; Nash, H.; McClanahan, C.; Uboweja, E.; Hays, M.; Zhang, F.; Chang, C.-L.; Yong, M.G.; Lee, J. Mediapipe: A framework for building perception pipelines. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.08172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MediaPipe Team. Getting Started with Python. MediaPipe Documentation. Available online: https://mediapipe.readthedocs.io/en/latest/getting_started/python.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Zhang, F.; Bazarevsky, V.; Vakunov, A.; Tkachenka, A.; Sung, G.; Chang, C.L.; Grundmann, M. MediaPipe Hands: On-Device Real-Time Hand Tracking. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10214. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Choi, J.Y.; Ha, E.J.; Choi, J.H. Human pose estimation using mediapipe pose and optimization method based on a humanoid model. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Brizuela, G.; Cisnal, A.; de la Fuente-Lopez, E.; Fraile, J.C.; Perez-Turiel, J. Lightweight real-time hand segmentation leveraging MediaPipe landmark detection. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 3125–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, T. Genetic evolution vs. function approximation: Benchmarking algorithms for architectural design optimization. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2019, 6, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ball, R. Parametric design for custom-fit eyewear frames. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaoglou, P.; Tzotzis, A.; Efkolidis, N.; Kyratsis, P. Influence of the 3D Printing Fabrication Parameters on the Tensile Properties of Carbon-Based Composite Filament. Appl. Mech. 2024, 5, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaoglou, P.; Tzotzis, A.; George, S.D.B.; Kyratsis, P. Testing the degree of influence on tensile strength of 3D printing parameters in carbon fiber reinforced PETG. Int. J. Mod. Manuf. Technol. (IJMMT) 2025, 17, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.