1. Introduction

Permanent magnet machines (PMMs) are expensive to manufacture due to fluctuating rare-earth permanent magnet (PM) cost [

1]. Additionally, the application of permanent magnet machines (PMMs) is limited by their low flux-weakening capability, susceptibility to demagnetization from faulty currents, and low efficiency at low speeds. Alternatively, an induction machine (IM) is a preferred choice, with its low manufacturing cost, inherent line-start mechanism, robust structure for hazardous environments, etc. [

2]. However, it has a low starting torque, low efficiency at low loading, low torque per volume density, low power factor, etc. [

3]. Some of these problems are addressed in switched reluctance machines (SRMs) and synchronous reluctance machines (SynRMs), which have high efficiency due to the elimination of copper losses in their rotors; they have extremely high achievable speeds, since the main source of heat in this type of machine is the stator, which can be easily cooled. However, the PM-less alternatives lack flux controllability and have scaling problems. This issue is addressed by employing wound-field synchronous machines (WFSMs) which have a dedicated flux source on the rotor [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In this case, a dc or excitation current is supplied through the brushes and slip-ring assembly to the rotor field winding coil and rotor flux is generated. The advantage of WFSMs is their ability to adjust the excitation current without drawing reactive power. This ability helps the WFSM to adjust the power factor and torque even when the inverter voltage source is unable to do so, unlike PM machines which have a constant source of excitation, creating problems in designs for traction applications. The efficiency of WFSMs is marginally less than PM machines because of the additional losses in the field winding of WFSMs. However, WFSMs can adjust the field excitation, which allows the WFSM to have an extra degree of freedom to optimize the efficiency of the WFSM above and below the rated load conditions using three control variables: direct-axis current (i

d), quadrature-axis current (i

q), and field current (i

f) [

8,

9,

10]. The flexible control with three variables makes WFSMs more suitable for numerous applications, such as traction, power generation, industrial tools, etc. On the other hand, the disadvantages of WFSMs are the malfunction of the brushes and slip ring in the long run, excitation loss of the rotor, rotor copper loss, and increased cost due to the additional field exciter. To eliminate the disadvantages associated with a conventional WFSMs, several brushless topologies have been proposed in the literature.

Dual-inverter topologies have been widely adopted in synchronous machine drive systems to enable independent and flexible control of multiple winding sets or excitation channels. Typically implemented using two conventional three-phase voltage source inverters supplied from a common or split dc link, dual-inverter configurations provide full voltage utilization, decoupled modulation, and a high control bandwidth. In the literature, such topologies have been applied to brushless excitation of synchronous machines, dual-stator and open-end winding structures, and harmonic current injection schemes aimed at torque ripple reduction and efficiency enhancement. Several studies have reported improved torque quality and reduced current harmonics when dual inverters are used for simultaneous fundamental and harmonic excitation, highlighting their effectiveness as a benchmark solution for high-performance synchronous machine drives [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

However, dual-inverter systems offer superior modulation freedom and simpler control implementation at the expense of increased hardware complexity, switching losses, and cost, compared with reduced-switch alternatives.

Therefore, the nine-switch inverter (NSI) topology has been extensively investigated as a reduced-switch alternative to conventional dual three-phase voltage source inverters for synchronous machine drive systems. By sharing one inverter leg between two three-phase outputs, the NSI reduces the number of power switches, gate drivers, and associated losses while maintaining independent control capability for multiple AC ports. Various modulation strategies, including space-vector and carrier-based PWM schemes, have been proposed to address inherent constraints of the NSI, such as limited voltage utilization and coupling between output phases. Furthermore, comparative analyses have shown that, despite a slight reduction in voltage margin, the NSI can achieve performance comparable to conventional dual-inverter systems in terms of torque control, harmonic distortion, and efficiency, making it an attractive solution for cost- and space-constrained synchronous machine drives [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

In the context of synchronous machines, prior studies have demonstrated the suitability of NSI configurations for applications such as brushless excitation, dual-stator windings, and multi-port power conversion, where both fundamental and auxiliary harmonic currents are required.

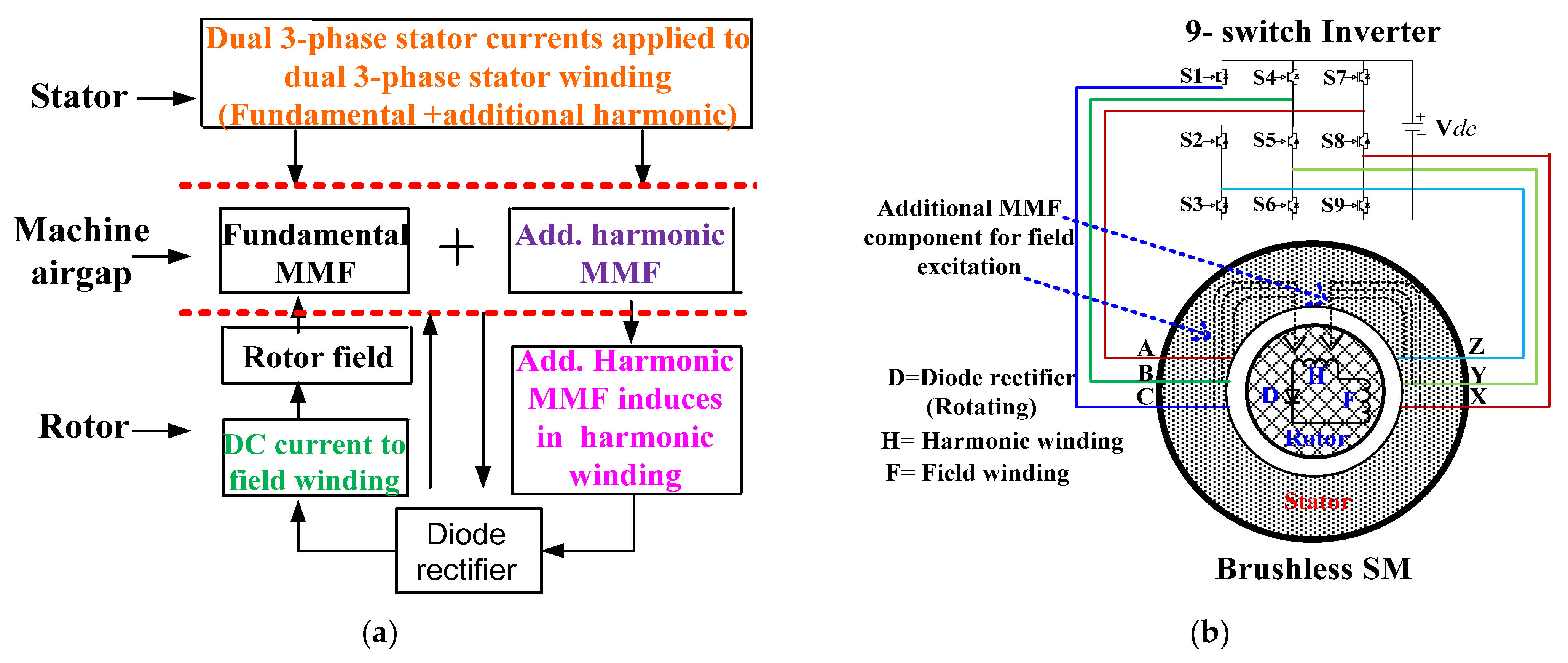

The brushless topologies [

7,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] given in

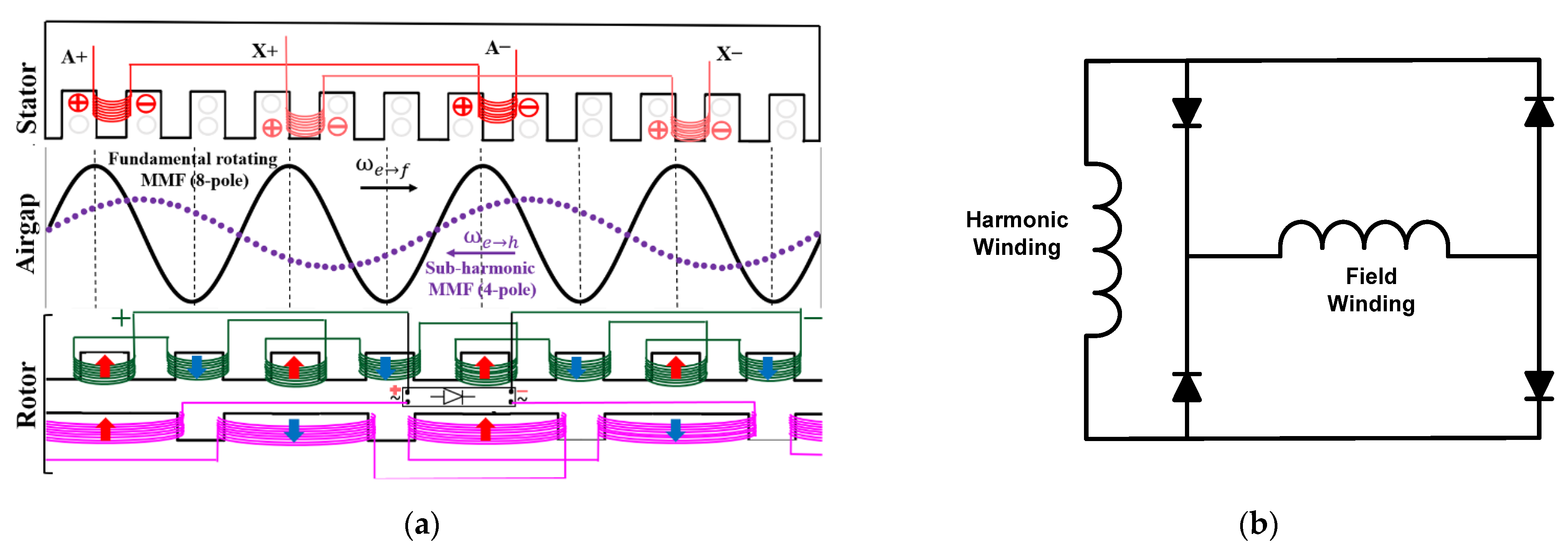

Figure 1a replaced the brushes, slip rings, and exciter assembly found in conventional WFSMs. Normally, in brushless (BL)-WFSM topologies, the power is transferred from the stator side to excite the rotor field by an additional harmonic excitation technique (see

Figure 1b). In

Figure 1b, the nine-switch inverter topology shows nine IGBT switches S1~S9 and the stator of the machine is wound with two sets of armature windings, namely ABC and XYZ. On the rotor side, H is harmonic winding, F is field winding, and D is the bridge rectifier. In the harmonic excitation technique, several orders of MMF harmonics are generated and utilized for rotor field excitation, namely fifth, third, and sub-harmonics [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The main problem with the available BL-WFSM topologies is that they are either dual-inverter topologies, which increases the cost, or single-inverter topologies with a low flux regulation capability due to an uncontrollable inducted rotor field current [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

This paper proposes the utilization of a nine-switch inverter topology which not only realizes the brushless operation of a WFSM, but also has excellent rotor flux regulation freedom.

Table 1 shows a comparison of the advantages of the proposed nine-switch topology in terms of various parameters with the conventional PM and wound-field excitation brushless synchronous machines. This paper discusses the operation principles of a nine-switch inverter topology, generating desired currents from the inverter topology. A 12-slot and 8-pole BL-WFSM is then simulated through a 2D finite-element method by applying the currents with the nine-switch inverter. The rotor flux regulation freedom is also analyzed through 2D FE analysis.

2. Proposed Nine-Switch Inverter Topology and Working Principle

The nine-switch inverter can produce dual three-phase voltage sets, namely A, B, C, and X, Y, Z. These three-phase voltage sets can be of different amplitudes and can be phase-shifted between each other.

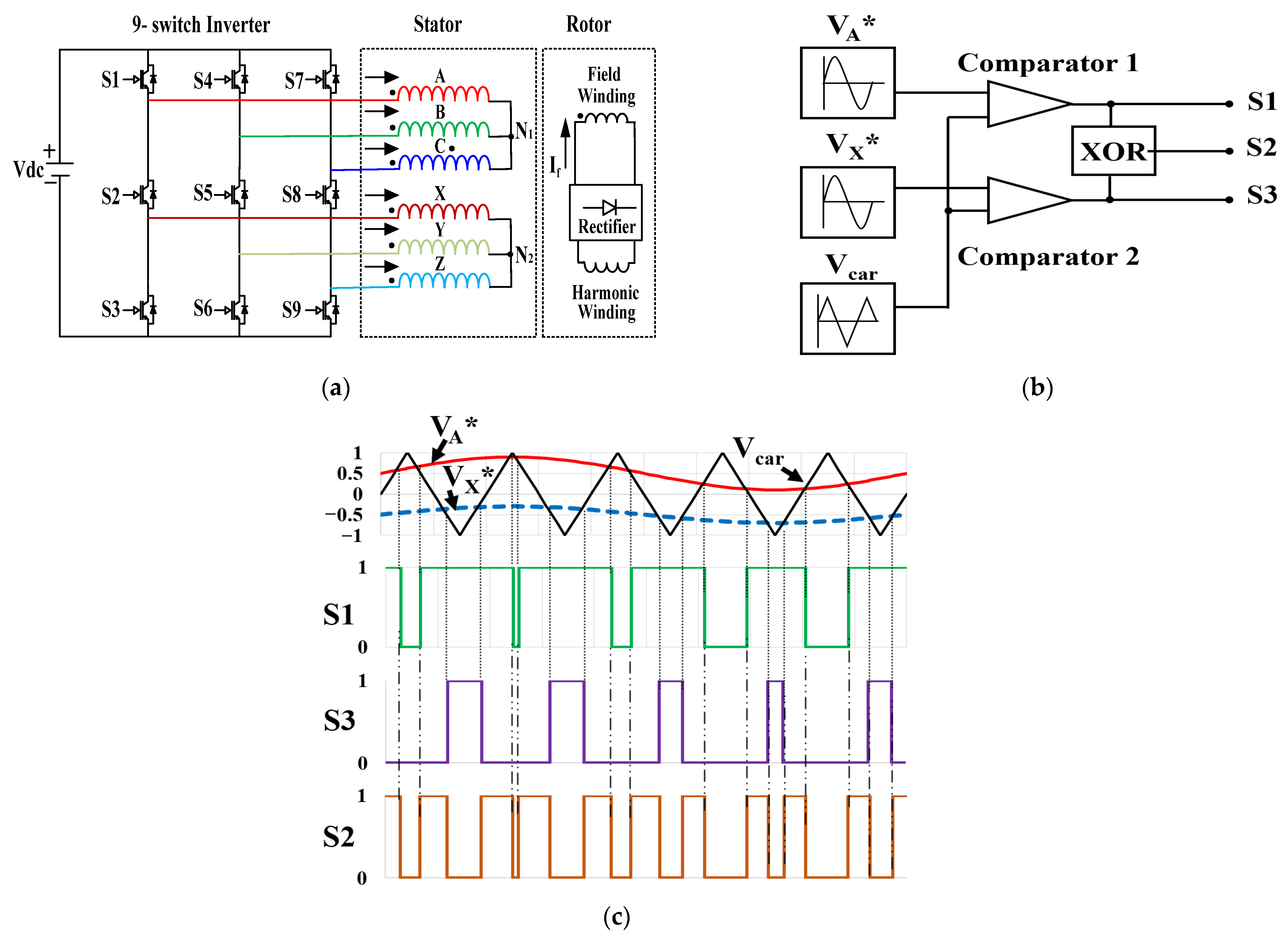

The nine-switch inverter circuit used in the BL-WFSM is shown in

Figure 2a, where S1–S9 are IGBT switches, N

1 and N

2 are the two neutral points for the two stator winding sets, and I

f is the inducted field current. The circuit consists of three legs. The switches S1, S4, and S7 control output A, B, and C and switches S3, S6, and S9 control output X, Y, and Z, respectively. The switches S2, S5, and S8 are common for A, B, C, and X, Y, Z. This can be represented as two three-phase inverters merging, one on top of the other. In this case, the currents in coils A, B, and C are in phase with the corresponding coils X, Y, and Z, respectively, calculated as

where

I1 and

I2 are the peak current values in the windings ABC and XYZ, respectively. In this work, we used sine pulse width modulation (SPWM) for the nine-switch inverter. The block diagram of the modulation circuit for the first leg is shown in

Figure 2b. In this figure, two normalized voltage reference signals, V

A* and V

x*, with an offset of 0.5 and −0.5, respectively, are compared with the triangle carrier signals (V

car) through two comparators. The triangle carrier wave typically has a frequency several times larger than the reference signals. The outputs of comparators 1 and 2 are the signals for switches S1 and S3, respectively. The logic operation exclusive OR (XOR) between the outputs of the comparators gives gating signals for the middle switch S2.

The generation of gating signals with modulation logic is shown in

Figure 2c, the solid line represents the reference for phase A, while the dashed line is for phase X. As we can see, when the reference V

A* ≤ V

car, switch S1 is on, and vice versa. In the modulation logic, the gating signals of S3 are generated similarly. The switch S3 should be turned on when both of the outputs of S1 and S2 have different values. The logic operation XOR, which can be written as

Satisfies this condition. In this equation,

z is the output signal,

x and

y are the operands, and the line above the operand stands for logical inversion. The reference signals for the SPWM were produced by the PI current controller in a dual synchronous reference frame. The control method of the unbalanced dual three-phase synchronous machine was presented in [

24,

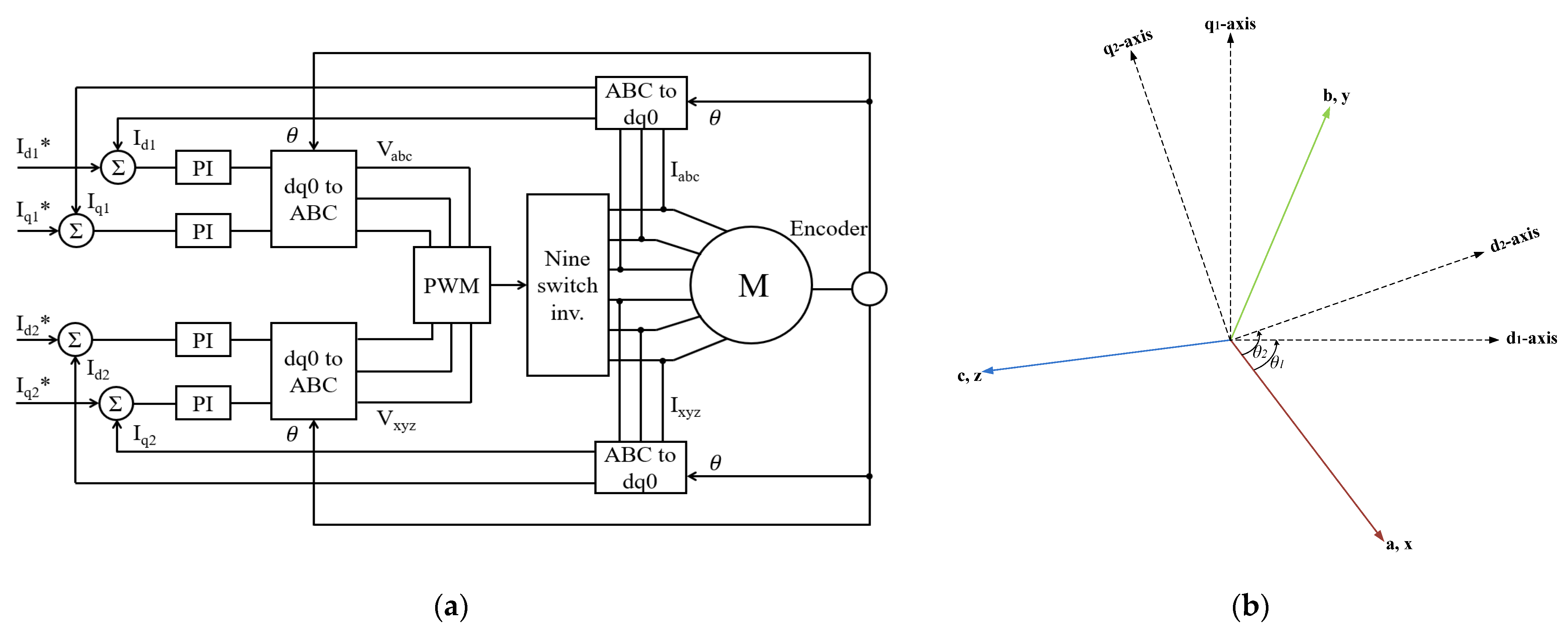

25]. However, because the detailed analysis of this method is beyond the scope of our paper, we will only briefly explain the underlying principle. To determine the control and state vectors, the dual three-phase quantities are transformed into the dq0 reference frame, as illustrated in

Figure 3b, with the help of transformation matrix T. Therefore, the currents in the dq reference frame will be

where

θ1 is the angle of the d1-axis with respect to the stator ABC frame a-axis and

θ2 is the angle of the d1-axis with respect to the stator XYZ frame

x-axis. Therefore, the voltage in the dual dq reference frame will be

where

Rs is the stator resistance;

Vd2, Vq2,

Vd1, and

Vq1 are the voltages in the first and second

dq0 reference frame, respectively; similar notation is used for the currents;

Ld and

Lq are the self-inductances of the d- and q-axes, respectively;

Ldd and

Lqq are the mutual inductances between the

d1- and

d2-axis, and

q1- and

q2-axis; ω is the angular frequency; ψ is the magnet flux.

Denoting the feed-forward as

We can decouple the voltage equations as follows

Thus, the control of the machine was simplified. The block diagram of the current controller is shown in

Figure 3a; the basic configuration of the current controller is given in [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In the proposed configuration, we can see that the implementation of decoupling feed-forward terms simplifies the control to two parallel independent

dq0 frames. The machine currents

Iabc are transformed into

Idq1 and the currents

Ixyz are transformed into

Idq2. The error between the referenced values and actual values is regulated by the PI gains and their outputs are then subtracted from the feed-forward terms. Next, the

Vdq1 and

Vdq2 voltages are transformed back to the

abc coordinate frame. The

Vabc and

Vxyz are normalized and modulated, and the gating signals are fed to the inverter.

3. Machine Configuration and Working Principle

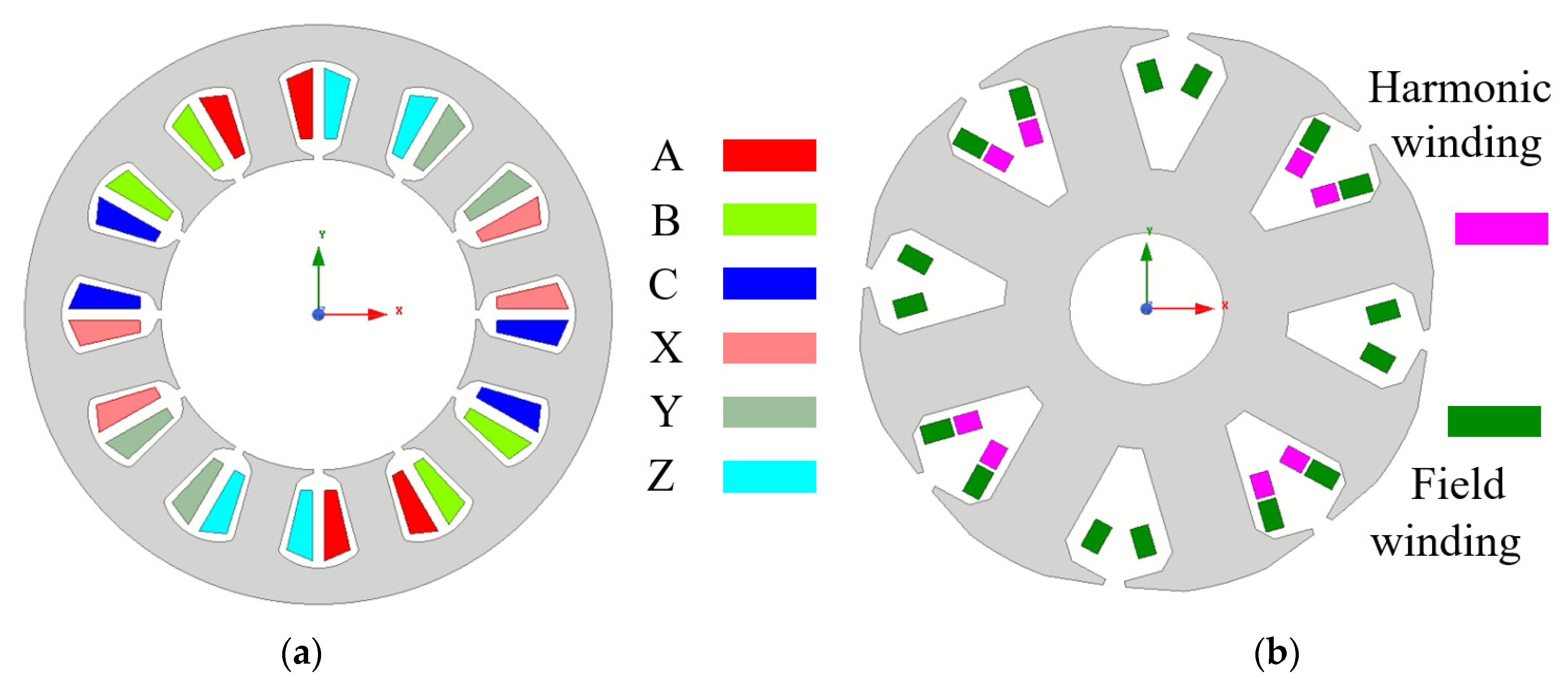

The nine-switch inverter with the BL-WFSM winding configuration is shown in

Figure 2a, where the connection of the machine coils with the nine-switch inverter is shown. As the rotor does not have brushes or a slip ring assembly, two windings are mounted on the rotor: an eight-pole field winding and an additional four-pole harmonic winding. An eight-pole and twelve-slot WFSM, as shown in

Figure 4, is analyzed with the proposed nine-switch inverter topology for brushless operation. The detailed design parameters are given in

Table 2. The block diagram of the BL-WFSM with its winding configuration is shown in

Figure 5a, where the rotor and stator winding configuration of the BL-WFSM is shown linearly. In the figure: on the stator, the red line represents the Phase A and X coils, while on the rotor, the green line denotes the 8-pole field winding, and the pink line indicates the 4-pole harmonic winding. Similarly in the air gap, the black sinusoidal waveform depicts the positive-sequence fundamental 8-pole rotating MMF, whereas the purple dotted waveform represents the negative-sequence sub-harmonic 4-pole MMF. The rotor does not have a source of its own; therefore, to excite the rotor field winding, an additional four-pole harmonic winding is placed on the rotor and a single-phase diode rectifier connects them, as shown in

Figure 5b. The rotor harmonic winding induces a four-pole sub-harmonic MMF, generated due to the difference in the currents of winding coils ABC and XYZ; the induced alternating current was rectified using a rotary diode bridge rectifier, which establishes a stable dc in the rotor field winding [

9]. The working principle of the BL-WFSM with the setup proposed in this work is the same as that shown in

Figure 1, where the additional sub-harmonic is produced due to the difference in the stator coil currents. The additional sub-harmonic, which is a four-pole MMF, induces voltages in the four-pole rotor harmonic winding. Since the speed of the four-pole sub-harmonic MMF is different from the rotor four-pole harmonic winding speed, an induction process occurs. Once the induction starts in the rotor harmonic winding, a rotary diode rectifier mounted on the rotor periphery rectifies the voltages and a dc is established in the rotor field winding. Consequently, an eight-pole rotor field is generated, which interacts with the eight-pole stator fundamental MMF harmonic and torque is produced.

With the diode forward voltage V

D being constant for the semiconductor material used, the voltage across the field winding can be calculated as

where V

h(RMS) is the rms value of the voltage across the harmonic winding and it can be calculated from the instantaneous harmonic winding voltage which is given as

where

K is the sub-harmonic coupling factor and

is the flux linkage of the harmonic winding with the sub-harmonic airgap magnetic field.

4. Fe-Based 2D Model Performance Analysis

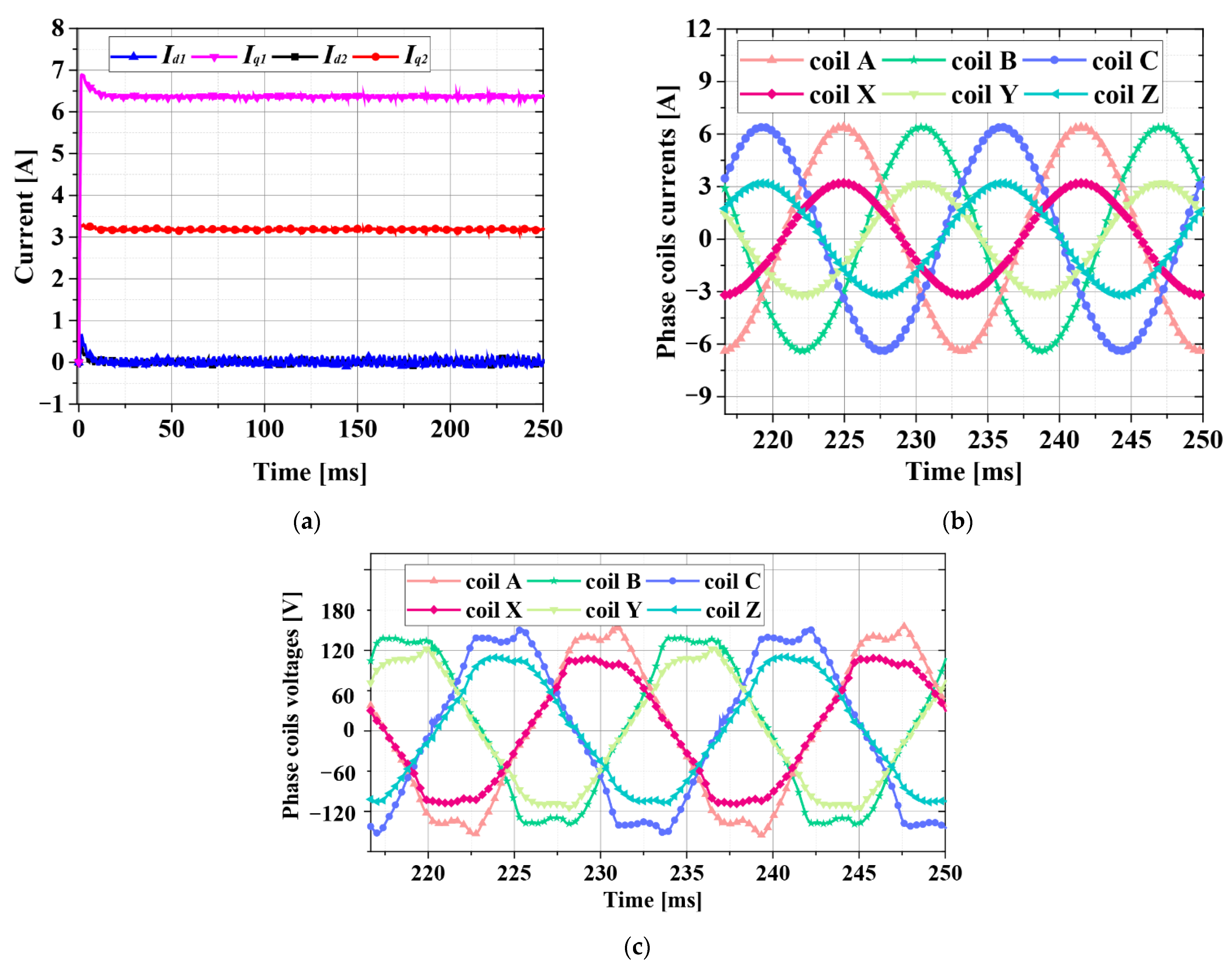

In the previous section the topology and working principles of both a nine-switch inverter and an eight-pole and twelve-slot BL-WFSM were explained. This section describes a co-simulation, wherein a nine-switch inverter was designed in Ansys Simplorer v2018.0 with 2D model of a BL-WFSM in Ansys Maxwell v19.0.0 for FE analysis to verify the operation principles of the nine-switch inverter with the BL-WFSM. The inverter i

d and i

q synchronous frame currents for both channels are shown in

Figure 6a, where it is shown that the inverter supplied rated currents to the ABC machine stator coils and half of the rated current to the XYZ machine stator coils. The corresponding FE-based currents of coils ABC and XYZ are also shown in a more natural frame of reference

Figure 6b. In load conditions, the FE-based balanced phase voltages of the stator coils are depicted in

Figure 6c.

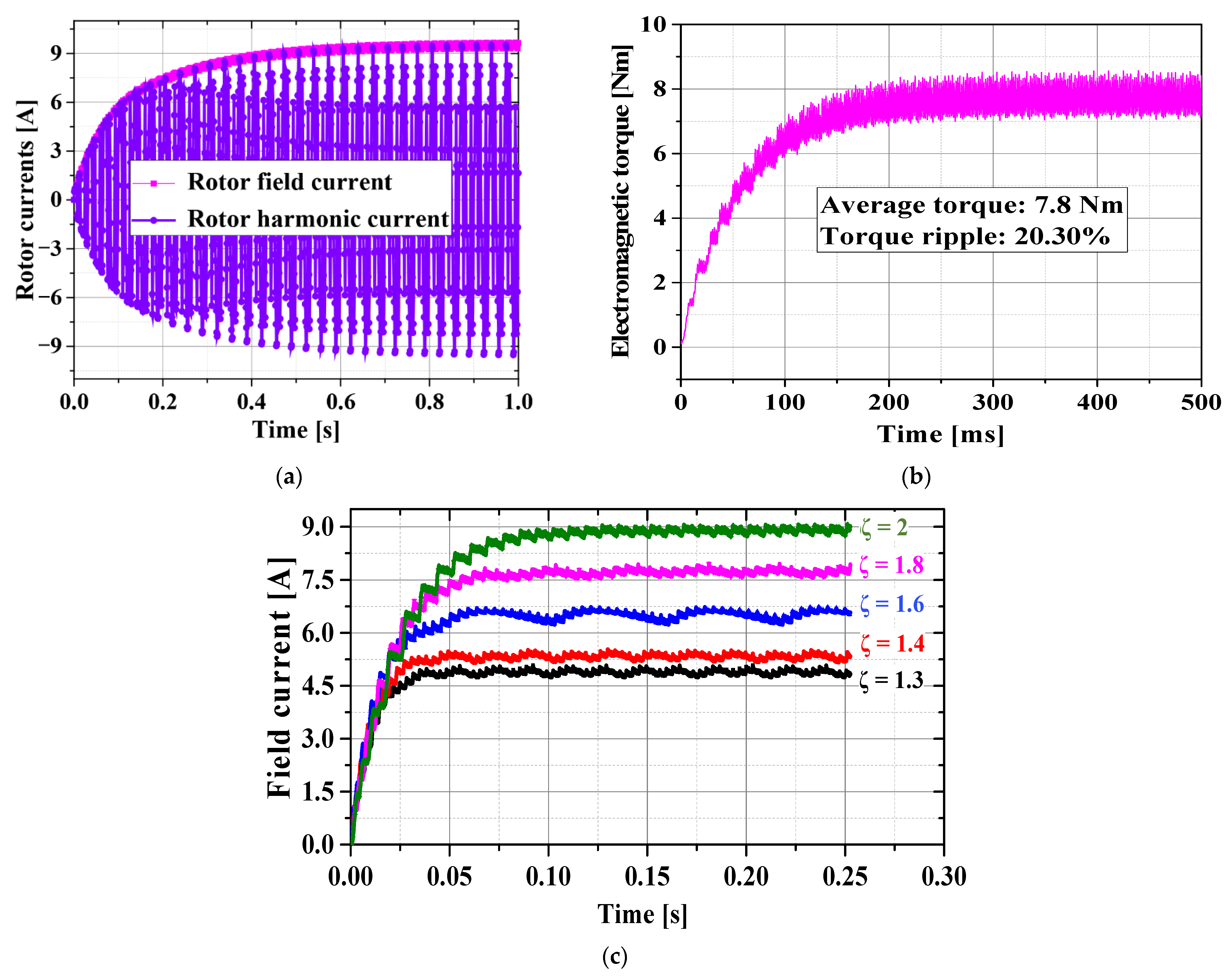

The machine model given in

Figure 4 was supplied with nine-switch inverter currents at a rated speed. As per the inverter and machine topologies and their working principles, the current difference between the ABC and XYZ coils produced an additional four-pole sub-harmonic MMF in the airgap alongside an eight-pole fundamental MMF (see

Figure 5a). The sub-harmonic MMF induced current in the rotor harmonic winding. The induced rotor harmonic winding current is shown in

Figure 7a; a 5.1 A rms current was established in the rotor harmonic winding. The induced alternating current was rectified by a rotary diode bridge rectifier (see the rotor in

Figure 2a and

Figure 5a). The output of the rectifier produced dc which was supplied to the rotor field winding and an eight-pole rotor flux was produced. The rotor field winding formed a 9.15 A dc in the steady-state region as shown in

Figure 7a. The eight-pole rotor flux interacted with the eight-pole fundamental stator MMF and torque was produced. The electromagnetic torque profile closely follows the rotor field winding current profile. The electromagnetic torque is shown in

Figure 7b, where in the steady-state region the torque was 7.8 Nm with a torque ripple of 20.30%.

For rotor flux regulation, the rotor field current was controlled by the stator ABC and XYZ coils’ current ratio ζ. Different values of ζ were used and the rotor field winding current variation was observed, as shown in

Figure 7c. Starting from ζ = 2, which is a rated condition, the induced rotor field winding current was 9.15 A dc at 900 rpm. When the ratio decreased to 1.8, the induced rotor field current decreased to 7.85 A dc. Similarly, when the ratio ζ was decreased to 1.6, 1.4, and 1.3, the corresponding induced rotor field winding currents were 6.53 A dc, 5.23 A dc, and 4.8 A dc, respectively, at the rated speed of 900 rpm. The variation in the rotor field winding currents at a rated speed with the variation in ratio ζ clearly showed the excellent rotor flux regulation freedom in the proposed work. This flux regulation freedom was absent in the single-inverter BL-WFSM topologies, whereas, in dual-inverter BL-WFSMs, the additional inverter/switches and additional dc source increases the cost of the system. So, considering cost and rotor flux regulation freedom, the nine-switch inverter topology is a better option.

5. Discussion of Practical Implementations

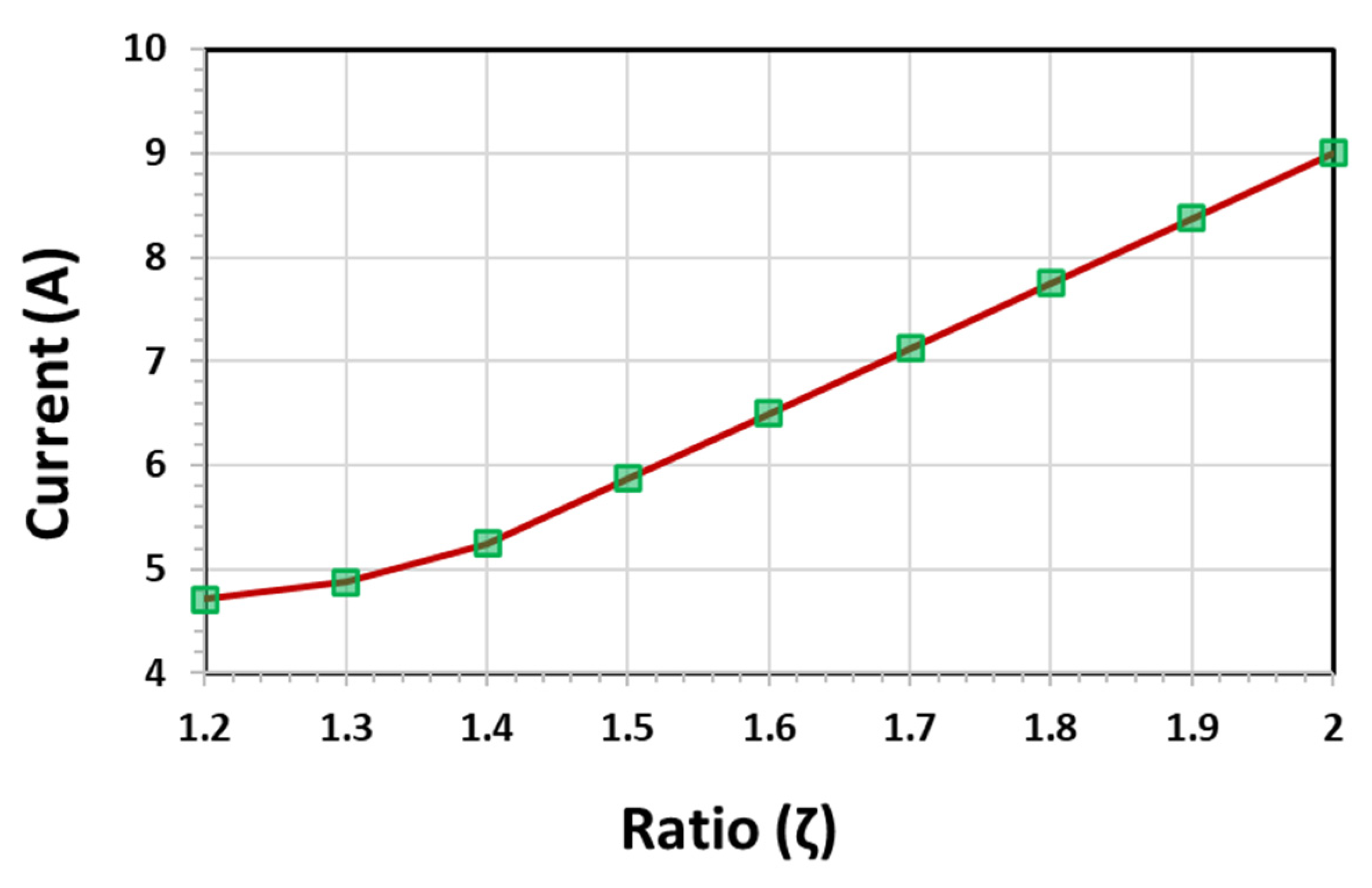

It can be observed from

Figure 8 that as the ratio of the two armature currents decreases beyond a certain point, the induced field current does not decrease accordingly. This can be seen as a non-linear behavior of field current generation.

The variation in the current ratio ζ directly affects electromagnetic torque through the corresponding change in rotor field current, as shown in

Figure 7. In addition, the induced voltage in the harmonic winding follows the sub-harmonic MMF magnitude, which is governed by the same ζ ratio. A detailed quantitative loss and efficiency analysis is beyond the scope of this work and will be addressed in future studies focusing on machine design optimization.

From a practical perspective, the implementation of harmonic injection using reduced-switch inverter topologies, such as the nine-switch inverter, introduces several challenges that must be carefully addressed. One important aspect is control performance under nonlinear operating conditions, including magnetic saturation, inverter dead-time effects, and switching nonidealities. These non-linearities can distort the injected harmonic currents and deteriorate the intended MMF sub-harmonic profile, particularly at high load or during transient operation. Advanced current control strategies and compensation techniques are therefore required to maintain stable and accurate excitation in practical drive systems.

The quality of the generated MMF sub-harmonic is also strongly influenced by machine parameters such as slot geometry, stator winding distribution, and magnetic material characteristics. Variations in leakage inductance, mutual coupling, and saturation levels can lead to deviations between the commanded and actual harmonic MMF components. As reported in the literature, these effects may reduce the effectiveness of torque ripple suppression or excitation control, highlighting the importance of accurate parameter identification and machine-specific design optimization when implementing harmonic injection schemes.

In addition, the use of a nine-switch inverter raises potential electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) concerns due to the shared inverter legs and increased switching interactions between the two three-phase outputs. Coupled switching transitions can result in higher common-mode voltages and current ripple, which may exacerbate conducted and radiated emissions. Appropriate PWM design, switching frequency selection, and the use of passive or active filtering techniques are therefore essential to ensure compliance with EMC requirements while preserving the benefits of reduced switch count.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a nine-switch inverter topology was proposed for BL-WFSM operation with excellent flux regulation capability by controlling the sub-harmonic component using inverter PWM-modulated signals. Contrary to existing brushless WFSM topology, the proposed work reduced cost by utilizing nine switches instead of twelve switches, a 25% reduction of the switch count, and utilizing a single dc source instead of two dc sources. On the operation side, the proposed topology was able to regulate the rotor field with more freedom by controlling the machine stator current ratio (ζ) between the ABC and XYZ coils. Based on the stator ABC and XYZ coil current ratio ζ, field regulation was demonstrated as follows: changing ζ from 2 to 1.3 decreased the induced rotor field current from 9.15 A dc to 4.8 A dc. This validates the suggested nine-switch topology’s capacity to effectively regulate rotor flux in brushless WFSMs. The proposed topology combined with 12-slot concentrated armature winding offers high core utilization with self-excited brushless operation for wound-field synchronous machines. Additionally, sub-harmonic flux generation reduces core loss due to low-frequency power transfer. The brushless WFSM’s suggested topology produced 7.8 N·m. of torque with a 20.30% torque ripple. A detailed comparative analysis of torque ripples with other brushless and conventional topologies will be considered in future work. This study has presented the basic concept of using a nine-switch inverter topology for the operation of a brushless WFSM. As a result, additional research might be conducted with machine design optimization in mind for better torque characteristics. The proposed concept, offering low cost, robustness, and rotor flux regulation freedom, can be applied to electric and hybrid vehicles, aerospace starter–generators, renewable energy systems, industrial drives, and marine propulsion, where a wide speed range, high efficiency, and brushless reliability are essential.