Abstract

This study introduces the Product Variety Costing Method (PVCM), a data-driven framework that addresses the limitations of existing costing approaches, which fail to accurately present the cost of product and part variety, thereby constraining cost-informed decision-making in modular product development. Traditional cost allocation methods often lack one or more of the following: a full life-cycle perspective, a lower level of granularity according to the product structure, or a combined integration of qualitative and quantitative data. The PVCM bridges these gaps by combining Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) with hierarchical product structures and empirical enterprise data, enabling the quantification of variety-induced resource consumption across components, subsystems, and complete products. An industrial application demonstrates that the PVCM enhances cost accuracy and transparency by linking resource use directly to specific product abstraction levels, thereby highlighting the true cost impact of product variety. In this case, results revealed deviations of up to 60% in the adjusted contribution margin ratio relative to traditional overhead-based methods, clearly indicating the influence of product variety on cost assessments. The method supports design and managerial decision-making by allowing evaluation of modularization based on detailed cost insights. While the study’s scope is limited to selected life-cycle phases and a single company case, the findings highlight the method’s future potential as a generalizable tool for evaluating economic benefits of modularization. Ultimately, the PVCM contributes to a more transparent and analytically grounded understanding of the cost of variety in complex product portfolios.

1. Introduction

Manufacturers in today’s industry must balance the rising demands for external product variety to satisfy customer-specific requirements with the need to constrain internal variety in parts and processes [1,2]. This trade-off drives competitiveness, but through the growing number of product variants, it also increases product complexity [3]. However, the potential benefits of reducing internal variety can substantially improve the economic performance of the product [4] and influence decision-making in design [5,6]. Since most product costs are determined during the early stages of product development through decisions on functionality, concepts, and architectures, designers exert their greatest influence at this stage. These early design choices are difficult and costly to reverse later in the product life cycle [7,8]. Consequently, product cost serves as a governing metric in product development [8], yet the complex interplay between product variety, modular architecture, and both direct and indirect costs represents a critical management challenge [9].

Modular product architectures have long been recognized as a means to address this challenge by enabling the systematic reuse of components and subsystems while maintaining external variety [10,11,12]. A modular approach enables manufacturers to deliver customized products cost-effectively by leveraging standardized interfaces and interchangeable components [13,14,15]. However, the indirect economic effects of modular product architectures are often not fully captured by existing costing methods. Traditional costing methods primarily capture direct costs, neglecting indirect or variance-related costs that arise from product variety [16,17,18]. This lack of transparency can lead to suboptimal design decisions and an incomplete understanding of how variety propagates through the product life cycle [19,20,21]. As indirect costs may represent up to 50% of the total cost in specialized industries [8], the inability to accurately trace and allocate them restricts modular product development and complexity management [6,22,23]. A recent study by Nørgaard et al. [24] revealed that current costing approaches inadequately capture the impact of modularity across the product life cycle, as costs are largely assessed at the product level despite being incurred at lower abstraction levels, known as the decomposition of product structures on a component, subsystem (assembly), and product level [24], underscoring the need for more refined, multi-level cost models. Related work in hierarchical modelling and intelligent manufacturing highlights a growing need for cost-aware, data-driven methods capable of handling structural complexity [25,26]. A new structured approach is therefore needed, one that integrates quantitative data from enterprise systems, product data extracted from industrial companies, with qualitative insights from operational experts, and that can represent costs consistently across multiple levels of abstraction throughout the product life cycle phases [20,24,27].

To address this gap, this paper introduces the Product Variety Costing Method (PVCM), a structured approach for evaluating the cost implications of product variance across a product portfolio. The method builds on the principles of Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) [26]. Unlike existing methods, the PVCM does not take its starting point at the product variant level. Instead, it assesses activities across three abstraction levels of the product structure as defined by Nørgaard et al. [24]: component, subsystem, and product by combining quantitative data related to the different levels with qualitative knowledge provided by domain experts. Thereby, enabling a less resource-intensive approach than the traditional Activity-Based Costing (ABC) [9], which has historically been used to evaluate variety-related costs in modular product structures [16] or cost modularization [21].

The PVCM is demonstrated through its application in an industrial waste compactor manufacturer, where it is used to analyze how product variance influences cost distribution and to compare these findings with traditional allocation methods. The study shows that including variance-induced resource consumption, expressed as a time measure, alters the perceived economic performance of product platforms and orders, highlighting both under- and over-costed products compared to conventional approaches. In doing so, the paper contributes to a deeper understanding of the cost of variety, particularly in terms of indirect costs, providing design engineers and managers with data-driven tools to more accurately evaluate the economic impacts of introducing product variants, modules, or components. This can ultimately serve as decision support for modular product development and other design decisions related to addressing the challenges of increased demand for personalized products [28,29]. The methodology is particularly relevant for manufacturing companies operating in engineer-to-order (ETO) or configure-to-order (CTO) environments [30,31], where frequent customization leads to a high number of unique components and limited reuse [32,33]. For such firms, the PVCM supports more transparent cost allocation, enabling better-informed design, sourcing, and platform decisions [34,35].

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the State of the Art within existing cost allocation methods related to product variety and modular design. Section 3 outlines the proposed methodology, comprising six stages. Section 4 demonstrates the application of the PVCM in an industrial context. Section 5 discusses the results, implications, and limitations of the study, while outlining potential future directions of research. Lastly, Section 6 concludes by highlighting the overall contribution of the study.

2. State of the Art

Existing costing systems, traditionally developed for stable, low-variety product environments, struggle to allocate indirect costs to specific products accurately in settings characterized by high product variety [3,36]. This makes it challenging to exhibit the economic benefits of a modular product architecture, since the benefits of this design are rarely realized in the development phase, but in the later life cycle phases as indirect cost savings by restricting internal variety [5,16,24]. Several methods have been developed for evaluating the economic and organizational benefits of modular product architectures with either qualitative or quantitative measures. However, existing methods exhibit limitations in scope, depth of quantification, and applicability to broader industrial settings.

ABC was identified in early research as a potential method for evaluating the benefits of modularization. Thyssen et al. [16] used it to compare the cost competitiveness of modular product alternatives with different product variants, it was later extended to include product families and product platforms, with the framework: Cost Modularization proposed by [21,37]. Most recently, Tay & Chen [38] have highlighted the potential of using ABC to restructure activity costs around modular design decisions. While these studies provide a method for relating specific activities to design decisions, their scope is limited to particular phases of the product life cycle, such as effects within inventory management and production, respectively. Furthermore, the resource-intensive nature of the ABC limits its applicability in many industrial contexts [36,39].

To address these challenges, TDABC, recognized for its simplicity and accuracy, was integrated into modularization frameworks by Mertens et al. and Ripperda & Krause [17,40] to quantify process-related costs. This integration represents a fundamental element of the extended Impact Model of Modular Product Families (IMF) [9], which builds upon the earlier work of Hackl et al. and Hackl & Krause [19,41]. Their studies identify more than 70 effect chains of modularization across the product life cycle, systematically linking them to strategic impacts such as time, cost, quality, and flexibility. The resulting IMF framework serves as a knowledge-based decision-support tool capable of dynamically assessing quantifiable effects across life-cycle phases, which, within this area of research, often are divided into sales, engineering, production, procurement, and after-sales and service phases [9,42]. However, the framework does not account for the integration of company processes and activities across different levels of the product structure (e.g., components, subassemblies, or complete products), limiting the model’s flexibility when evaluating modular product solutions at the module or part level.

Maisenbacher et al. [43], who adopted a comprehensive life-cycle costing perspective and applied it to platform alternatives, similarly fall short of achieving a sufficient level of granularity, which is an indication of the degree of detail in the decomposition of a product’s structure, to accurately capture the effects of product variety across different abstraction levels. In contrast, Altavilla & Montagna [20] address several of these shortcomings by combining case-based reasoning, ABC, and parametric cost estimation relationships to assess the impact of design choices on product life-cycle costs. Their model emphasizes the importance of abstraction levels within a complete life-cycle perspective. However, it is explicitly tailored to standardized assembled systems and products characterized by extensive part and module commonality across product variants. This focus limits its applicability to portfolios with high product variety, elevated product and process complexity, and high degrees of customization.

Across the reviewed studies, it is evident that few costing approaches effectively integrate both qualitative and quantitative data within a unified model, often resulting in insufficient information for conducting comprehensive life-cycle analyses. Consequently, this state-of-the-art review, aligned with the future research directions identified by Nørgaard et al. [24] and supported by similar observations in Altavilla & Montagna and Xu et al. [20,44], highlights three principal research gaps for assessing the cost of variety in non-standardized portfolios with product and part variety:

- Lack of comprehensive models with a life-cycle perspective capable of managing large volumes of empirical data from all stages of the product life cycle.

- Absence of cost allocation methods that operate at lower abstraction levels with increased granularity for customized, high-variety products.

- Insufficient integration of qualitative and quantitative data in cost estimation models.

Building on these identified gaps, this study introduces a method that integrates TDABC with hierarchical product structures and variety analysis to quantify the cost of product variants, thereby enhancing cost-informed decision-making in modular design.

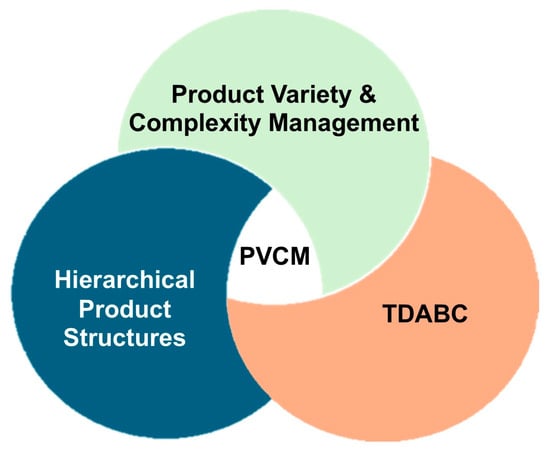

3. A Method for Estimating the Product Variety Costs

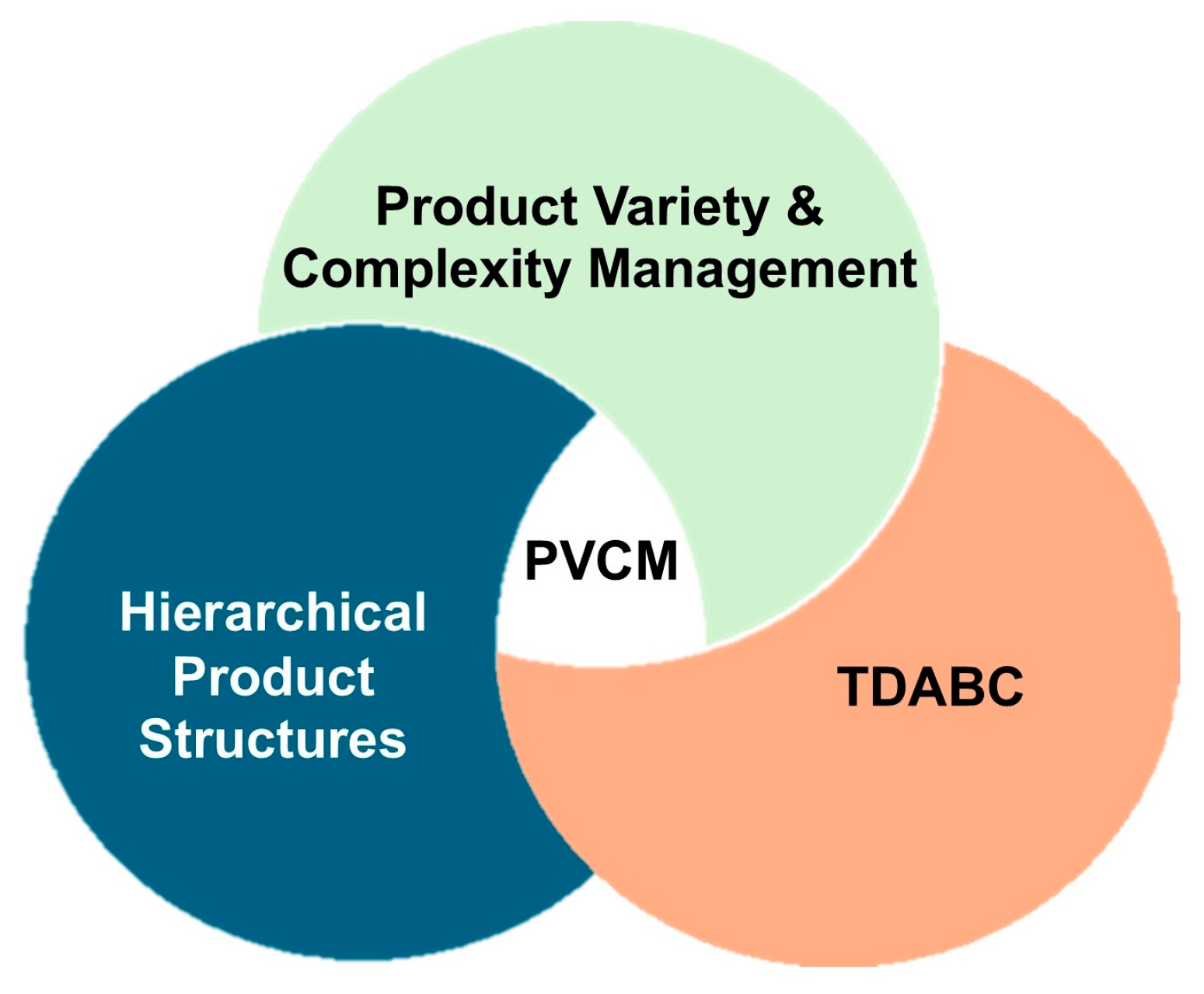

In this section, a methodology for assessing the cost of variance across a product portfolio is proposed through a structured framework. The developed PVCM differs from existing approaches, which often start the assessment at the product variant level [45]. Instead, it assesses activities across the three abstraction levels: component, subsystem, and product, as suggested by Nørgaard et al. [24], combining quantitative data from enterprise systems with qualitative process knowledge from employees. This integration of the two methods allows their respective strengths to be utilized [46], and enables the identification of how and where activities are influenced by product variance within the product portfolio. An illustration of the three primary conceptual elements of the PVCM using a three-circle Venn diagram can be viewed in Figure 1. Each circle represents one of the method’s core inputs:

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview of the PVCM. A three-domain Venn diagram illustrating how Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC), hierarchical product structures, and product variety and complexity management intersect to form the PVCM framework.

- TDABC—providing activity times, capacity cost rates, and the logic for time-based resource allocation.

- Hierarchical Product Structures—representing the multilevel parent–child product structure, determining how variety propagates from components to products.

- Product Variety and Complexity Management—focusing on identifying, measuring, and evaluating the effects of product variety, including unique parts, and variant-driven activities.

The intersection of these three domains forms the PVCM core: a data-driven framework for allocating resource consumption and estimating variety-induced costs across product abstraction levels and emphasizing how PVCM synthesizes structural information, costing logic, and complexity insights to support cost-informed design and modularization decisions.

Improved accuracy is achieved by linking data from multiple sources to the different abstraction levels [47], thereby enhancing the granularity with which specific cost activities can be traced and allocated. In turn, this enables the aggregation of product variance effects from the lowest level (component) to the highest (product), providing novel insights into variance costing allocation [20,24]. Generally, in case research, the study will contain a phase of data collection, followed by the construction of a model or hypothesis, which must be tested or validated, and finally provide results for possible interpretation [48]. This method takes these principal elements and refines them into six stages for this case research, as shown in Figure 2 and briefly described below. Each stage will be elaborated in greater detail in Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5, Section 3.6 and Section 3.7.

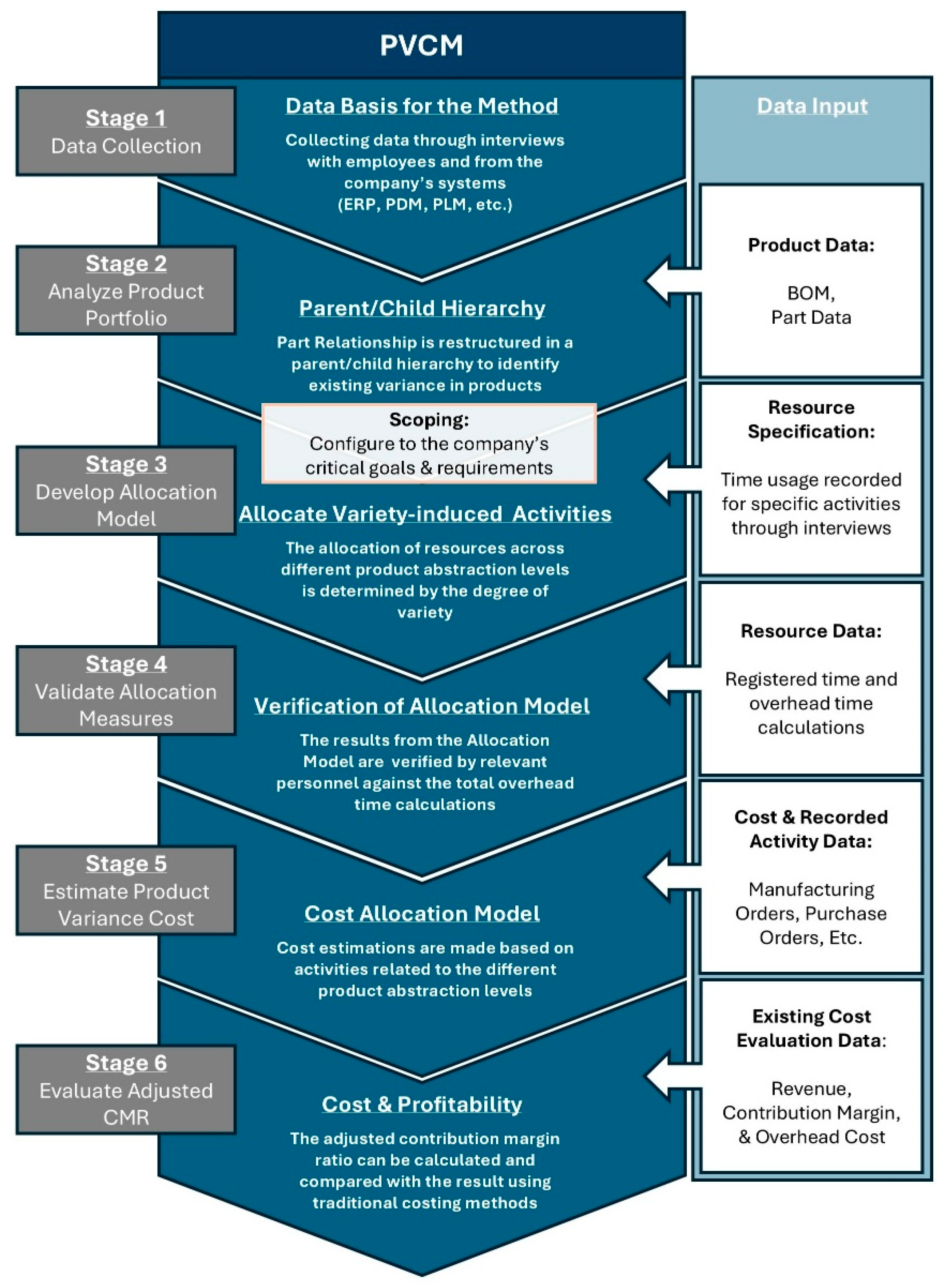

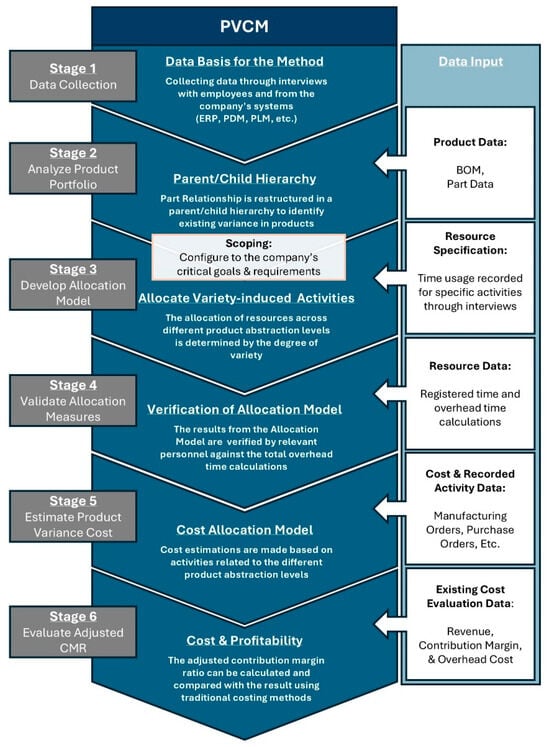

Figure 2.

Process diagram including all stages of the developed Product Variety Costing Method (PVCM), illustrating the step-by-step workflow from data collection to the evaluation of the contribution margin ratio (CMR) after adjusting for the cost of variety. The diagram visualizes inputs, transformations, and outputs for each stage of the method.

PVCM consists of six sequential stages:

- Data Collection: where qualitative insights from domain experts and quantitative transactional data from enterprise systems (ERP, SQL, PDM) are gathered and structured.

- Analysis of Product Portfolio: in which product structures are transformed into hierarchical parent–child relationships to identify abstraction levels and unique parts.

- Development of the Allocation Model: where TDABC-based resource measures are linked to part-level activities and aggregated through the product hierarchy.

- Validation of Allocation Measures: ensuring feasibility and alignment with departmental capacities and, when available, time-logged activities.

- Estimation of Product Variance Costs: integrating direct cost elements with allocated resource use to compute adjusted variable costs.

- Evaluation of the Adjusted Contribution Margin Ratio (CMR): enabling assessment of the financial effects of product variety compared with traditional overhead-based allocation.

This step-by-step structure supports a transparent and replicable workflow that can be adapted to different industrial contexts while maintaining methodological coherence across abstraction levels of the product structure.

3.1. Stage 1—Data Collection

The data collection process begins with mapping the company’s product portfolio and identifying relevant data sources. Qualitative insights are obtained through semi-structured interviews [49] with stakeholders at every stage of the product life cycle, including sales, engineering, procurement, production, service, and after-sales [9,19,41]. Having multiple investigators conducting the interviews will strengthen and increase the coherence of findings [48]. The interviews are structured to collect information regarding the following:

- Order-fulfillment workflows and activity sequences from the perspective of TDABC [39];

- Data inputs and outputs at each process step of the product life cycle;

- Time estimates for recurring tasks and activities.

This provides the foundation for identifying where product or part variety influences the process through customization, as detailed further in the coming sections. The operational insights gained at this stage are subsequently aligned with transactional and master data from the company’s information systems.

The quantitative data sources are extracted from a Structured Query Language (SQL) database underpinning the company’s Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) and Product Data Management (PDM) systems, including data tables such as sales transactions, manufacturing orders, purchase orders, Bill-of-Materials (BOM) structures, and master data. The collected data are transformed into fact and dimension tables [50], forming the foundation for a relational model that enables both detailed analysis and portfolio-level aggregation. The structuring of data tables can thus be described as a relational data warehouse, where each data element is linked similarly to the construct of a star-, snowflake, or starflake schema [51,52].

3.2. Stage 2—Analyze Product Portfolio

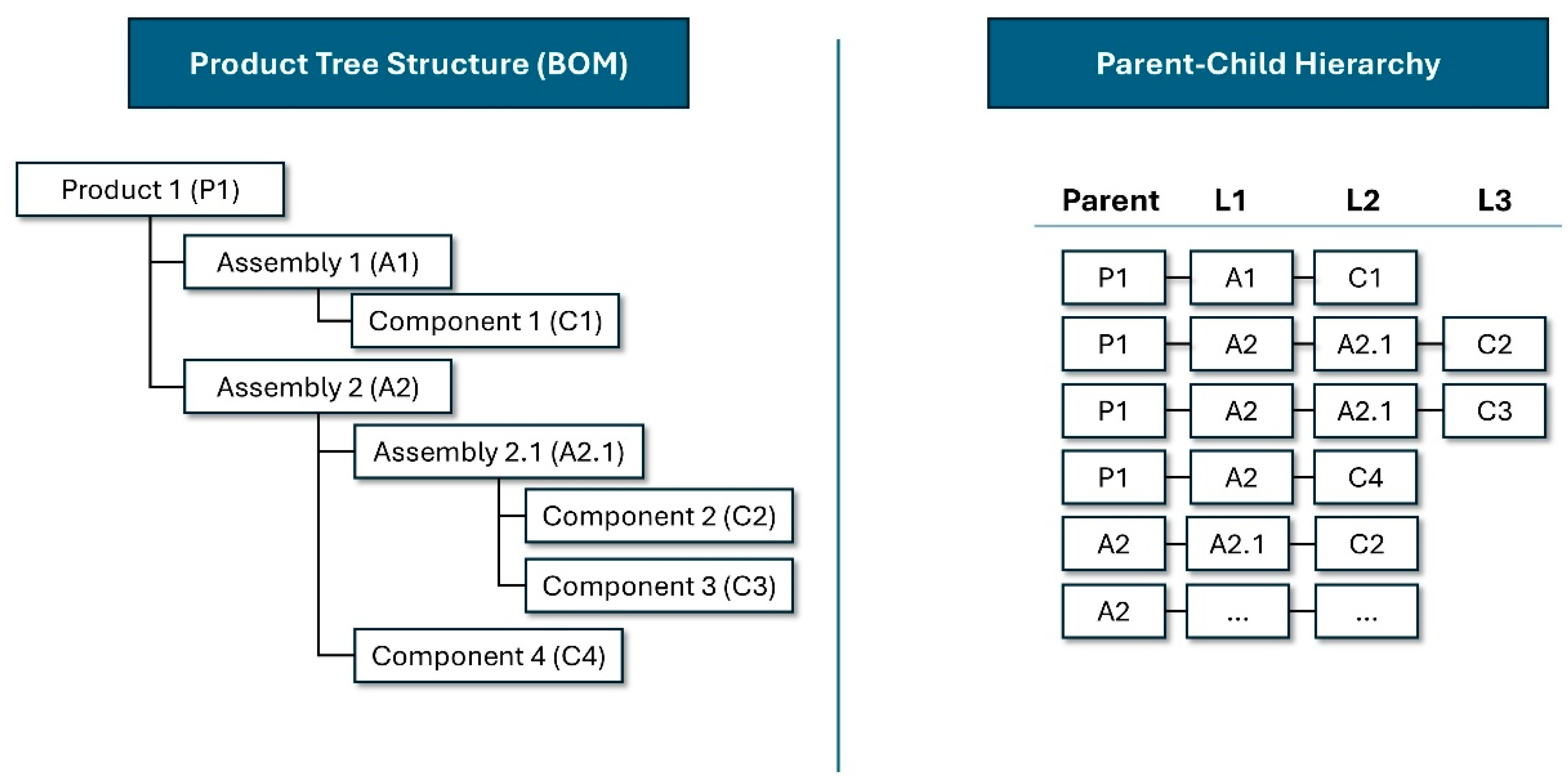

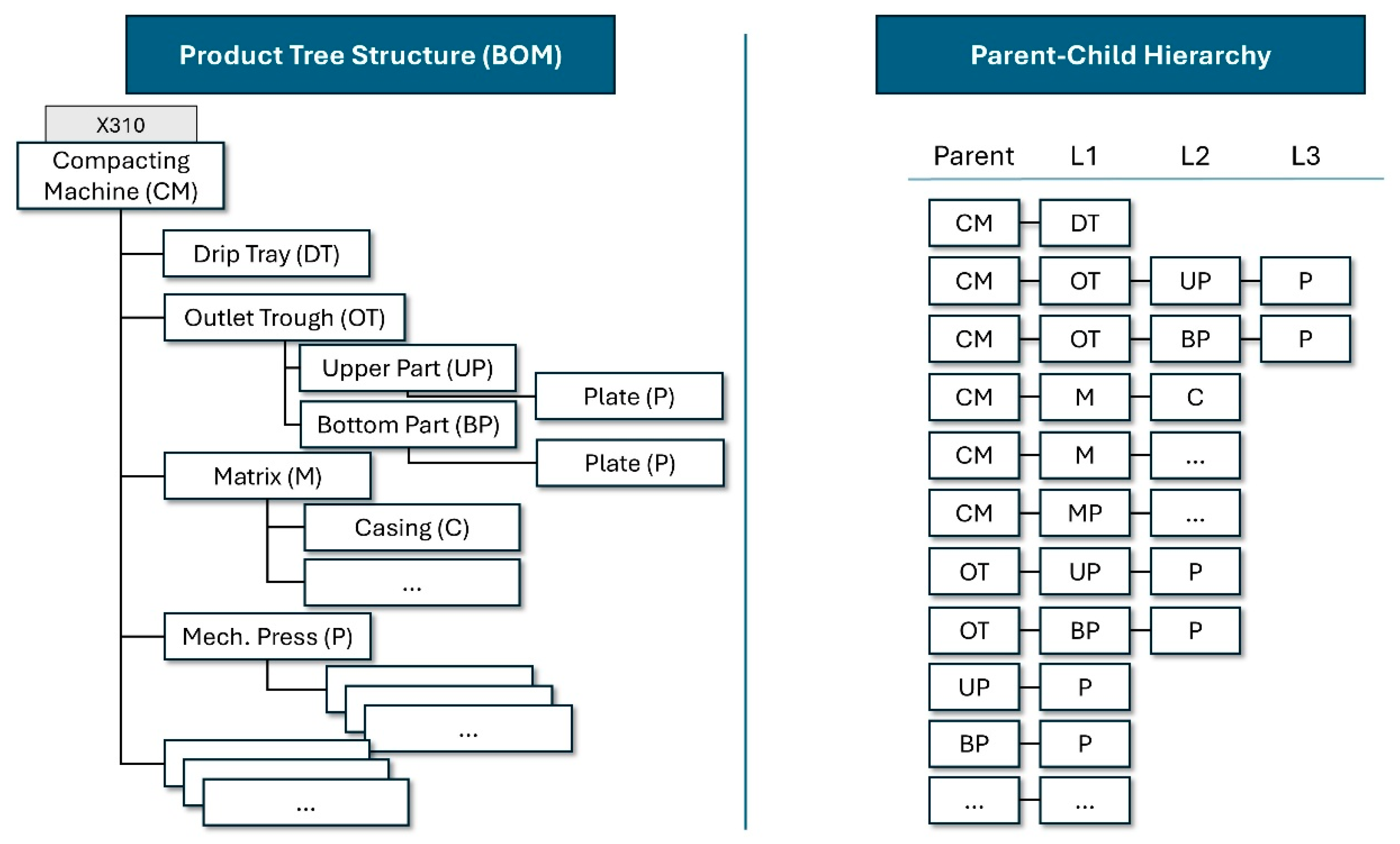

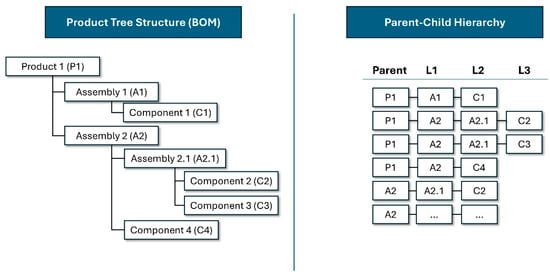

Product structures are represented as parent–child hierarchies derived from BOM relationships, enabling identification of abstraction levels (component, subsystem, product) as suggested in Nørgaard et al. [24] for improved accuracy of cost allocations. This stage provides the basis for detecting unique parts and understanding how variety propagates through the product portfolio. The product structure is the physical and hierarchical representation of all parts and assemblies that make up the product, essentially, the product BOM [53]. The part relationships, which correspond to the BOM for each product, are represented as extended strings that display the complete chain of links between part numbers across the entire product portfolio in the parent–child hierarchy, revealing the full extent of relations between part numbers without duplicates. This structure enables the identification of the abstraction level of each part number, whether at the product, subsystem (assembly), or component level. A generic example of the transformation is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Generic overview of the transformation of a BOM structure to the parent–child hierarchy. The different levels of the hierarchy are detailed by the horizontal axis identifiers (L1, L2, …, etc.).

This will increase the granularity of the analysis and ultimately deepen the accuracy of the allocation estimates based on these findings, where data availability permits [20,24]. Additionally, the parent–child hierarchy can reveal the number of relationships associated with each part number, including the number of different BOMs it appears in. More importantly, the method can determine whether a part number occurs in only one BOM, in which case it is regarded as unique to that product solution. The mathematical formula used for determining this in the model is written in Equation (1).

It is defined as, let i be the current item (child), and R the set of parent–child relations.

Equation (1): The Part Relations formula used in the model for identifying whether a part number is unique to a product solution based on the parent–child hierarchy.

The function returns the number of relations in which part occurs as a child; if does not appear in any relation, neither as a child nor as a parent, the value is 0.

3.3. Stage 3—Develop Allocation Model

Building on the principles of TDABC [3,39], allocation measures are developed to link variety-induced activities to departmental resource use in line with the scope of the company’s critical goals and requirements. Expert estimates of activity times are combined with transactional records, enabling time-based resource consumption to be attributed to individual part numbers and aggregated from the bottom up to subsystem and product levels.

Product life cycle activities are mapped across departments, forming the basis for developing a resource allocation index. Estimates are derived from domain experts with daily operational experience, and, following the principles of TDABC, time-based resource measures are assigned to each activity. By linking the identification of unique parts with the estimated effort required for their creation, the model allocates resources across abstraction levels in proportion to the degree of variety introduced into the portfolio. A mathematical formula is used in the allocation model for allocating resources to each department. The formula is listed in Equation (2).

Equation (2): The formula for allocating resources from different departments to specific part numbers based on the abstraction level and activities performed.

Where the definitions are

- : allocated resource measure for department d associated with item i.

- : number of direct parent–child relations in which part i occurs (must equal 1 for allocation).

- : set of abstraction levels (e.g., part, assembly, product).

- : constant for department at level (e.g., hours per activity).

- : indicator function, 1 if item i belongs to level ℓ, 0 otherwise.

The formulation assigns time measures to specific items or part numbers based on departmental estimates. These allocated measures can then be aggregated to the assembly or product level by traversing the parent–child hierarchy. The abstraction level of the part numbers is determined based on the parent–child hierarchy. A value is only assigned to a part number, , if it is unique in the product solutions denoted by the function . Otherwise, the cell is left denoted as a 0-value.

3.4. Stage 4—Validate Allocation Measures

Validation of the calculated resource allocations is essential to ensure the reliability and credibility of the model’s results. The objective is to confirm that the estimated resource distributions reflect actual operational patterns and remain within feasible organizational limits. Validation can be performed at multiple levels.

At the activity or product level, model predictions can be compared with empirical data such as logged hours or recorded task durations. Deviations between the modeled and reported values may indicate over- or under-allocation, prompting recalibration of time estimates [54]. Furthermore, outliers, inconsistencies, or items with no recorded activity can be excluded to improve the robustness of the benchmark dataset. Validation must occur at a consistent level of abstraction: product, subsystem, or component to ensure comparability across items and departments.

At the departmental level, validation involves comparing the total modeled allocation of time estimates against available personnel capacity. This step confirms that the aggregate resource use predicted by the model is feasible within organizational constraints, thereby strengthening confidence in subsequent cost estimations [54].

When applied in different industrial contexts, the model should be adapted to reflect company-specific processes, data structures, and operational priorities [9]. Using multiple sources of evidence, such as time logs, departmental records, and expert assessments, enhances construct validity and reduces the risk of bias in interpretation [48]. Collectively, this multi-level validation framework increases both the internal and external validity of the resource allocation model, ensuring that the estimated cost effects of product variety are empirically grounded and transferable across contexts.

3.5. Stage 5—Estimate Product Variance Cost

A cost perspective is integrated into the variety-induced resource allocation. This is further extended by incorporating direct cost layers such as materials, labor, freight, claims, and similar cost elements specific to the company data. The aggregation of these costs will result in an adjustment of the total cost, or Expanded Variable Cost (EVC), which can be expressed as Equation (3):

Equation (3): The Expanded Variable Cost, where the cost of the allocated resources to item i (part number) is included

The expanded variable cost for item is defined as the sum of department-specific resource allocations, weighted by their personnel costs, plus the direct costs of material, labor, freight, and claims. Where the definitions are

- : total adjusted cost associated with item

- : personnel cost rate for department (Currency defined by the system).

- : departmental resource allocated to item (e.g., time or activity measure).

- : set of departments (e.g., Engineering, Procurement, etc.).

- : Material, labor, freight, and claims costs for item i.

- Other cost pools specific to the company context (e.g., service and after-sales)

The rates found in the EVC(i) formulation were calibrated using a combination of (1) departmental payroll and financial records to determine the cost of supplying one hour of capacity, (2) semi-structured interviews with domain experts to estimate the time required for recurring activities, and (3) time equations reflecting variation across abstraction levels (component, subsystem, product). Variability in activity duration was handled by assigning separate time parameters to each abstraction level.

Together, the elements of EVC(i) provide a comprehensive estimate of the costs attributable to product, module, or part variety, forming the basis for calculating an adjusted contribution margin ratio.

3.6. Stage 6—Evaluate Adjusted Contribution Margin Ratio

In the final stage, the model enables the calculation of the adjusted contribution margin ratio (CMRV), which incorporates the cost of variety for each item . More specifically, CMRV is defined as the total revenue of item , , minus its expanded variable cost, , normalized by total revenue. The formula can be seen in Equation (4):

Equation (4): The contribution margin ratio when the cost of Variety is included, based on the resource allocations. The adjusted contribution margin ratio (CMRV)

Finally, the CMRV can be compared against both the regular contribution margin ratio (CMR) [55,56] as a benchmark value and the traditional overhead-based allocation methods, where the overhead costs are typically spread evenly across all products [3,56]. This comparison highlights deviations attributable to variety, providing insights into the true financial consequences of product customization and complexity.

3.7. Summary of the Six-Stage Product Variety Costing Method

The proposed method directly addresses the identified gaps by integrating TDABC with hierarchical product structures and empirical company data to quantify the cost of variety across abstraction levels. Unlike existing approaches that primarily assess costs at the product or variant level, PVCM establishes a structured, bottom-up framework that links activities and resource consumption to components, subsystems, and products. By combining qualitative process knowledge with quantitative transactional data, the method enhances both the granularity and validity of cost allocations. This integration enables the identification of variety-induced resource use across the value chain, offering a transparent foundation for evaluating the financial impact of design and modularization decisions. In doing so, PVCM contributes a generalizable and empirically grounded approach to cost estimation in high-variety, customization-driven product environments. In the next section, the proposed method will be applied in an industrial case.

4. Application in a Case Company

This section applies the six stages of the PVCM in an industrial setting. The aim is to demonstrate how the method can be operationalized in practice, from data collection and analysis of product architectures, through resource allocation and validation, to the estimation of product variance costs and the evaluation of adjusted contribution margins. Each subsection outlines one stage of the method and concludes with its contribution toward assessing the cost of product variance.

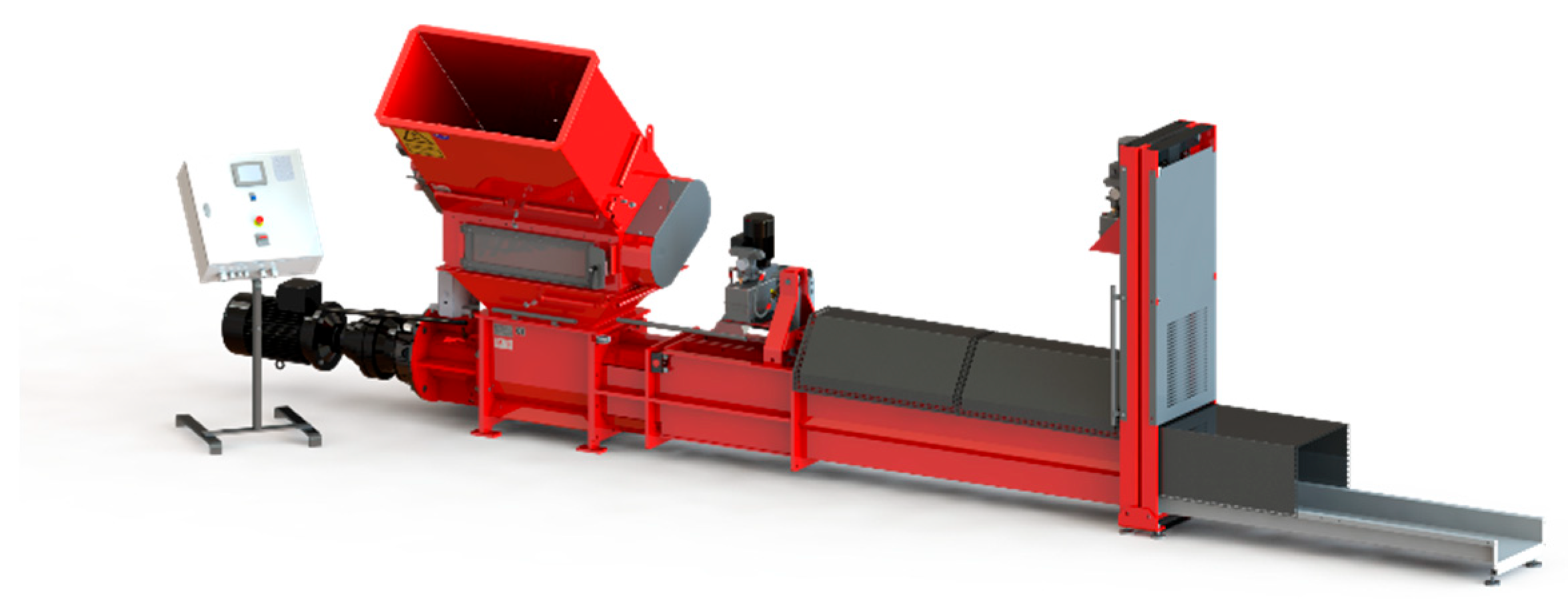

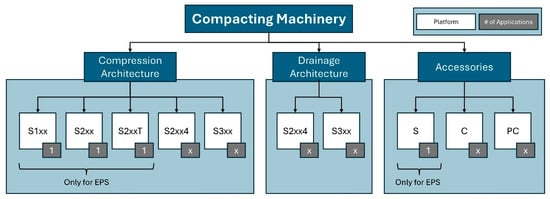

The proposed methodology was implemented in a company operating in the waste management sector, specializing in the design and manufacture of heavy machinery for waste compaction and dewatering. Following several years of growth, the company sought deeper insight into its product portfolio performance, internal variety, and related cost implications. Its main products are mechanical waste compactors, supported by accessory equipment such as silos, shredders, and conveyors. In operation, waste materials (e.g., expanded polystyrene (EPS), plastic bottles, paint buckets, etc.) are shredded and compressed to reduce volume, remove moisture, or separate liquids from solids, enhancing recyclability, lowering transport costs, and improving waste handling efficiency. The company’s machinery follows a partly modular architecture, sharing core elements across multiple application areas. It employs both CTO and MTS production strategies: low-capacity EPS machines are produced to stock, while higher-capacity models rely on modular subassemblies to maintain flexibility and short lead times. Customization typically occurs in design units such as the hopper, shredder, and outlet, which are adapted to customer-specific requirements. An EPS compactor is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

A waste compression machine from the case company.

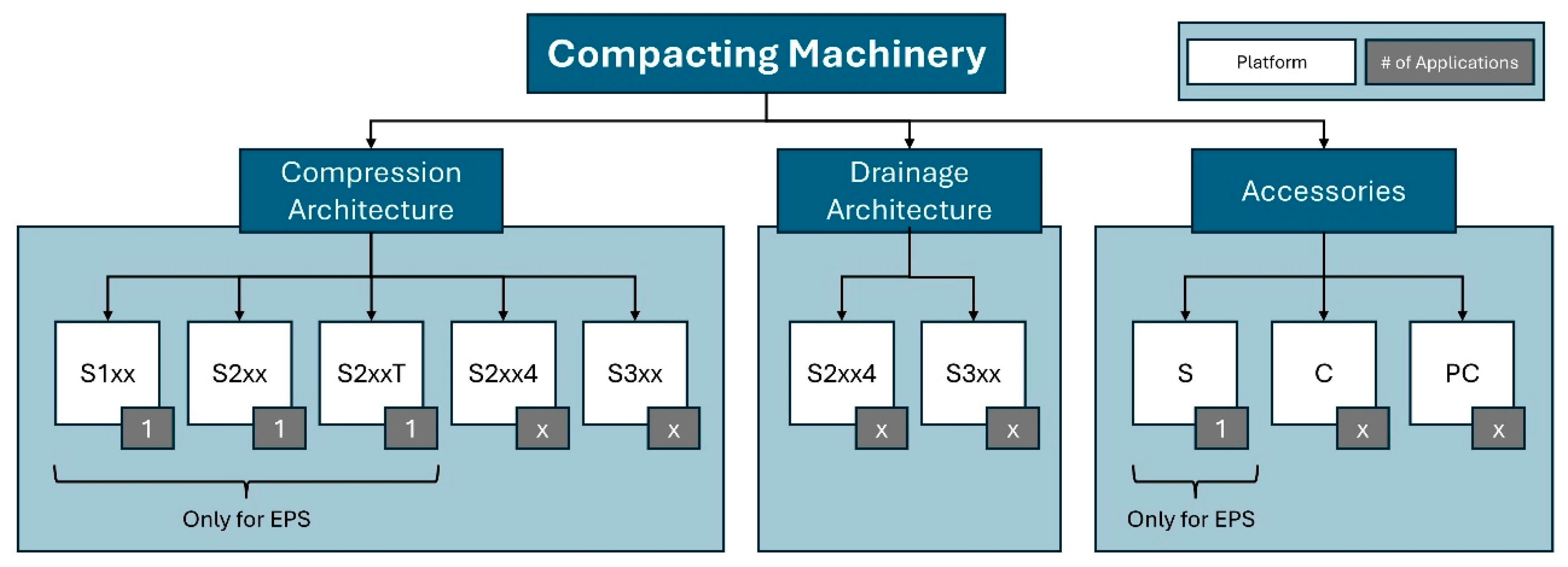

Two main product architectures define the portfolio, one for material compression and one for drainage, distinguished primarily by their outlet design. Each architecture encompasses several product platforms, some of which are shared across architectures, contributing to increased internal variety when existing solutions are adapted to new applications. Accessory products are offered separately to support integration into customer production lines. A hierarchy of the product platforms and architectures is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

An overview of the case company’s product architecture, product platforms (white squares), and the number (#) of application areas (grey square). Certain names and numbers have been partly anonymized to ensure confidentiality.

The company’s key engineering objectives are to extend the applicability of its machinery to new waste types while maintaining the core architecture, and to customize existing variants for customer-specific needs. Such flexibility is vital for competitiveness against manufacturers offering lower-cost, standardized solutions. Depending on customer requirements, the machines may operate as standalone units or as integrated systems within broader production environments. These conditions foster a high degree of product variety, particularly in components interfacing with external systems, where opportunities for reuse are limited.

In this study, the proposed method is applied to quantify the resource and cost implications of product variety across the company’s products and orders. To ensure both accuracy and practical relevance, all data interpretations and results were validated in close collaboration with company stakeholders.

4.1. Data Collection

In the first stage of the method, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected to construct an integrated model for the analysis. Data was obtained from two primary sources: (1) semi-structured interviews with personnel representing all departments involved in the product life cycle (e.g., sales, engineering, production, procurement, spare parts, service, and accounting), and (2) SQL databases containing the core data tables of the company’s ERP system. The latter included information on sales, production, production planning, supply chain activities, service, price forecasting, and procurement. Additionally, the company’s PDM system was utilized to visually identify and compare product-related data from these sources, thereby enhancing the overall understanding of the dataset. In total, 17 interviews were conducted with 13 participants spanning upper, middle, and operational levels. The interviews lasted between 40 and 60 min. Table 1 presents the distribution of participants by role and number of interviews.

Table 1.

Overview of the interviews conducted for the study.

The data extracted from the SQL database were categorized as either fact tables or dimension tables, the latter in the form of transactional data. The fact tables were linked to multiple transactional sheets within the model, with some comprising several tables originally separated in SQL. Table 2 summarizes the categories of data tables included in the model and specifies the number of SQL tables contributing to each category.

Table 2.

Overview of the data extracted from the SQL databases used in the model.

All data tables were formatted and transformed through queries before being incorporated into the data model. As the company transitioned to a new ERP system in late 2021, the data used in this analysis covers the period from 2022 to 2024, except for dimension tables, which continuously store the complete set of master and historical records imported into the system, also from before the transition.

Several challenges were encountered during the extraction and processing of the SQL databases. In some cases, the collected data were incomplete or lacked sufficient detail, particularly with respect to product group categorization, direct cost data, and the distinction between different application areas. These limitations constrained the extent to which the model could present results in relation to the defined product architecture and product platforms. This will be detailed further in the coming sections, when results based on this data are presented. The data collected in this stage form the foundation for the analysis conducted in the remaining five stages of the PVCM.

4.2. Analyze Product Portfolio

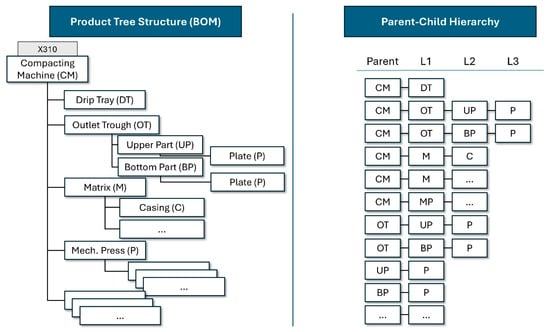

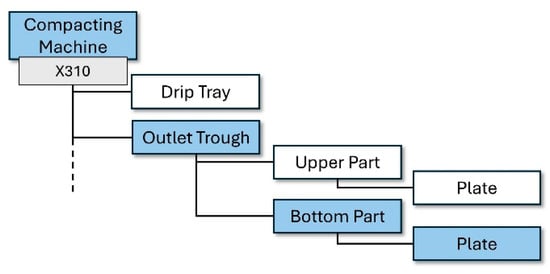

In the second stage of the method, based on the data collected regarding the relationships among parts in the SQL database, a parent–child hierarchy has been constructed following the description in Section 3.1. Detailing every part number relationship with each other across the product portfolio, dispersed across the three levels of abstraction. In Figure 6, a small example of a product from the case company (X310) is divided into a product tree based on the BOM structure, indicating the different abstraction levels such as product, assembly, and component.

Figure 6.

An excerpt of the first levels of the X310 BOM and parent–child hierarchy. The different levels of the hierarchy are detailed by the horizontal axis identifiers (L1, L2, …, etc.).

On the right side of the figure, the product structure is represented as a parent–child hierarchy, detailing the relationships between part numbers through a chain of links. Notice that not only part numbers on a product level, but also assembly level part numbers occur as parents in the hierarchy. The identification of abstraction levels and unique parts provides the necessary input for allocating resources in the next stage.

4.3. Develop Allocation Model

In the third stage, an allocation model is developed, following the description in Section 4.3, to capture the variety-induced activities based on the identification of unique part numbers in the previous stage. This allocation is ultimately determined by the degree of variety introduced into the product portfolio in the recorded time period. An example follows below:

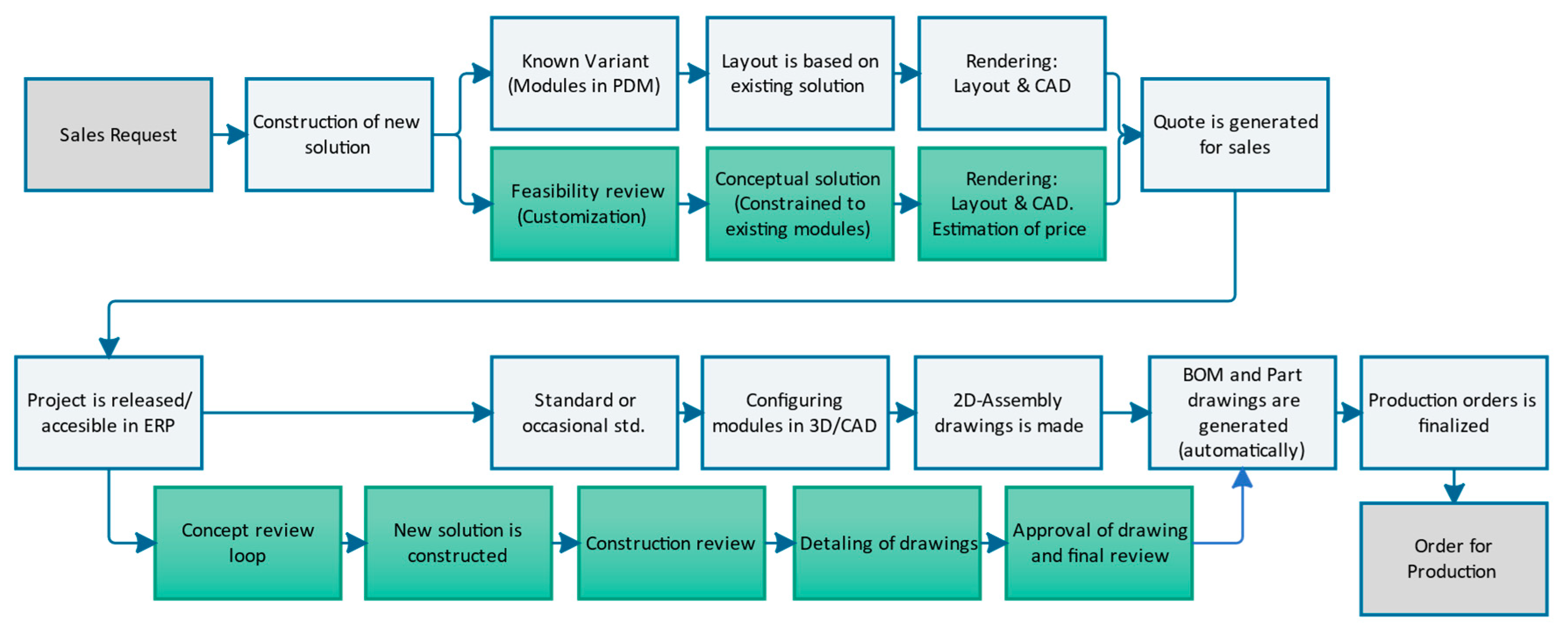

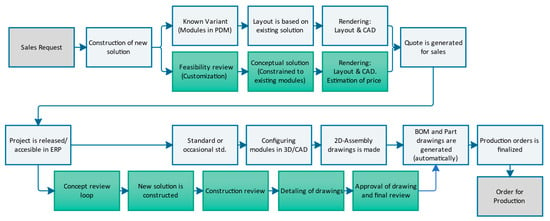

The activities associated with the product design process in the case company, from receiving an inquiry to processing an order, are illustrated in Figure 7. MTS solutions or only slightly customized products follow the process steps marked in white, whereas highly customized solutions follow a slightly different process highlighted in green. Time estimates for each activity were collected and recorded at the product, subsystem, and component levels, where applicable. Based on a list of already constructed and sold products from different platforms, with varying degrees of customization.

Figure 7.

A mapping of the engineering process activities in the case company.

The product design process for X310, a customized solution for an application area different from the standard EPS, will begin with an order request from the sales department to the engineering department. If a similar solution exists, a product layout and Computer-Aided Design (CAD) model will be constructed using modular parts from their PDM system. No new part numbers would be created. A consumption of time will be ascribed at a product level based on the activities. However, if none of the existing solutions satisfy the requirements, a feasibility review and a conceptual solution are made to provide an estimated price of the product. Similarly to before, time consumption can be ascribed on a product level. After a sales order has been confirmed by the sales department, the project is released to the engineering department. The construction phase of the product will begin by passing through several reviews before the CAD parts and drawings are finalized. Here, it is possible to ascribe a time consumption to each newly created part number on either a component, subsystem, or product level. After a final validation of the solution with the sales department, BOM and technical drawings are generated and passed on to production planning.

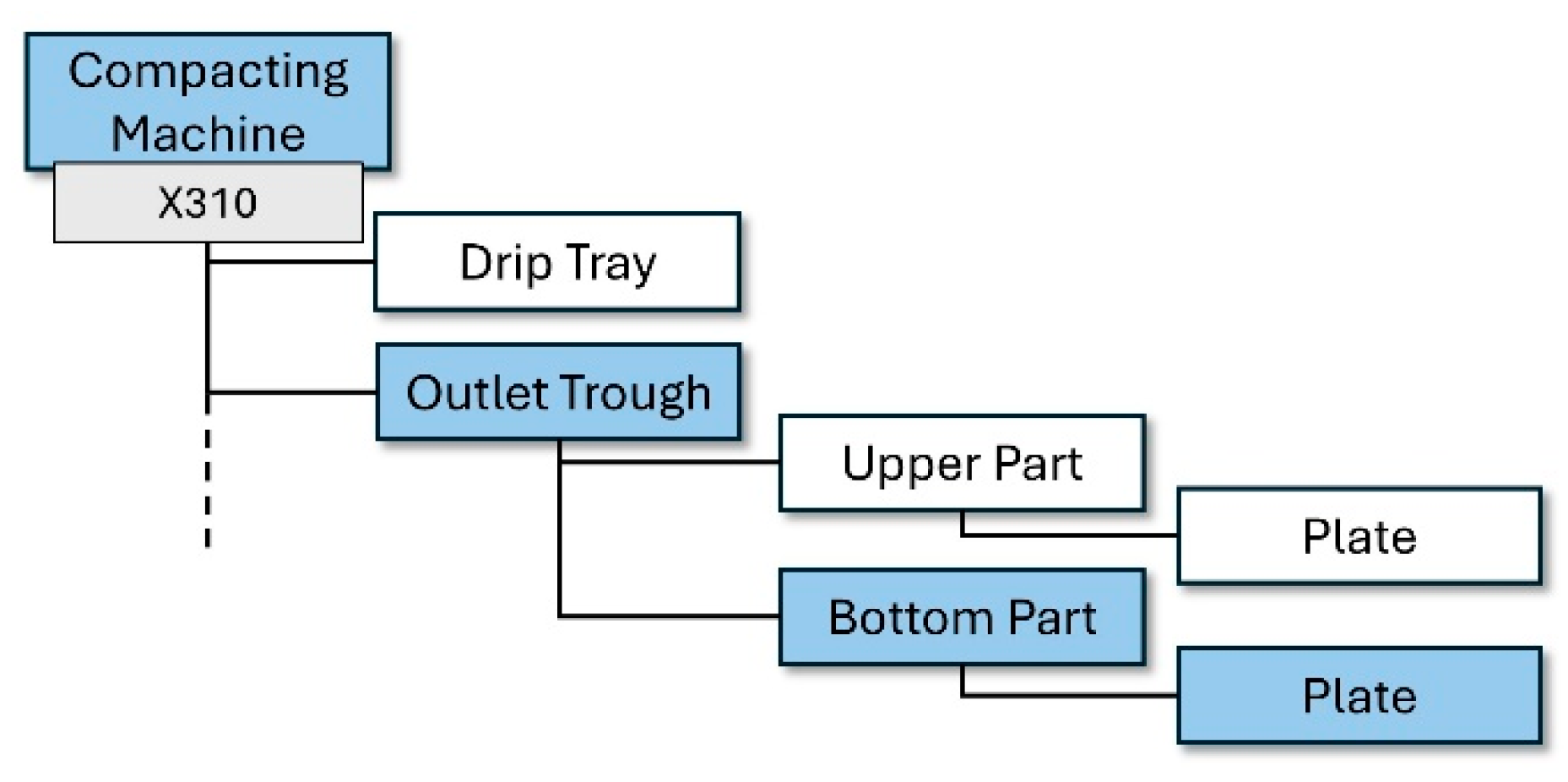

We can relate this to our example product, X310, product structure, when altering or customizing one part, e.g., a plate, a resource usage occurs, requiring the allocation of time for constructing the new part, along with additional resources for its assembly in a subsystem. This is recognized in the model by the creation of new part numbers in the system. The incurred time for each alteration or creation of the different abstraction levels (components and assembly) will be summed up to the product level. This is shown in Figure 8, where the affected parts of the product are highlighted in blue when a new part number is added.

Figure 8.

The figure illustrates the related effects of altering or adding a new part to a product, in this case, a plate component to X310. These activities can be aggregated at the subsystem level and at the product level.

Having described how resources are allocated to individual products during the design or engineering phase, the same procedure can be extended to the remaining life cycle phases. In the case company, resources were allocated from sales, engineering, production planning, and procurement processes. More specifically, the time measures applied in this case for the departments were

- Estimated hours used in sales based solely on finished sales orders;

- Estimated engineering hours in product development and design;

- Estimated production planning hours;

- Estimated procurement hours based on purchase lines.

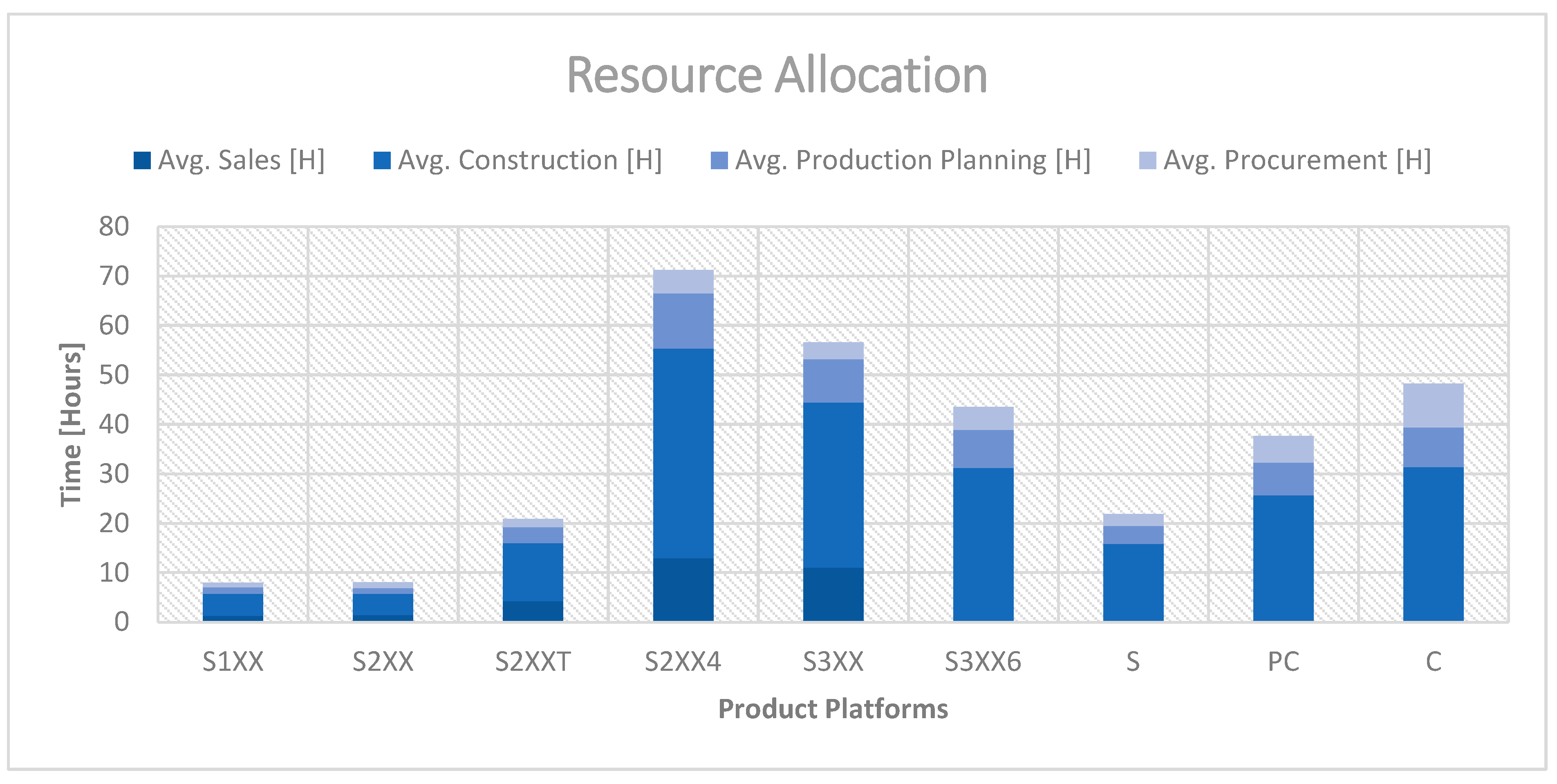

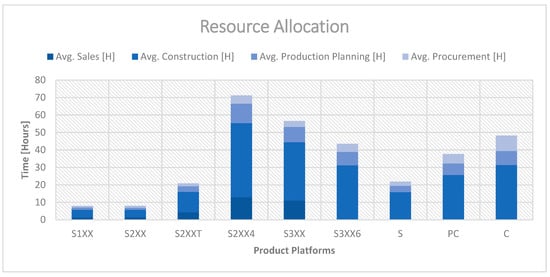

This allows for an aggregated overview of the average resource consumption for each department across the different product platforms. It should be noted, however, that due to limitations in data categorization, the platforms could not be further distinguished between compression and drainage architectures. The resource allocation for each product platform is illustrated in Figure 9 and spans the sold products from 2022 to 2024.

Figure 9.

Average resource allocation from life cycle phases is dependent on the level of variety found in the product platforms based on sold products in the period from 2022 to 2024.

Assessing the allocation of average departmental hours across the different product platforms provides a clear indication of where resources are most affected by added variety. This should not necessarily be interpreted negatively, as much of the variety is created within product platforms where customization constitutes a key competitive parameter for the company. This is particularly evident in the three product platforms (S2XX4, S3XX, S3XX6), which are often produced on a CTO basis. By contrast, the three platforms on the left of the chart (S1XX, S2XX, and S2XXT) are typically MTS and focus exclusively on a single market segment: EPS. Finally, the accessory platforms on the right (S, PC, C) also demand a substantial amount of resources. This can be attributed to their predominant sale as customized solutions and the relatively less developed maturity of these platforms, which increases the engineering effort required to adapt them for integration with the primary products.

Through the first three stages of the method, the allocation model has been developed, and the results have been illustrated by linking the variety-induced activities to resource use. Thereby establishing a basis for extending the analysis to other life cycle phases and cost layers.

4.4. Validate Allocation Measures

In the fourth phase, the allocation of resources across all products is verified to ensure feasibility. Since the case company does not systematically record time spent on specific projects, products, subsystems, or components, validation at these levels is challenging. However, resource use can be assessed at the departmental level by considering the number of personnel in each department and their average available working capacity over the same time period as the collected data [54]. Table 3 presents the percentage of available hours allocated by this method.

Table 3.

Percentage of the available hours in each department that were possible to allocate through the method.

The allocation to the sales department is relatively low because hours were assigned only at the product level and were limited to products sold, excluding time spent on lost sales, which represents a substantial share. By contrast, engineering and production planning are almost fully allocated relative to their available hours. A significant portion of the procurement department’s hours has been allocated, with room for further refinement. While the overall estimation could be improved, particularly in sales and procurement, some activities cannot be directly linked to specific products sold, as is the case with some materials in procurement, affecting the proportion of time allocated. As such, the model cannot fully capture all variety-induced costs across the value chain in this specific case study due to limitations in the format and availability of the data in the case company. The validation of allocated resources ensures that the model reflects a feasible use of available departmental resources. Thus, strengthening the reliability of the cost estimations for the remaining stages. The results have been presented to and validated by the case company.

4.5. Estimate Product Variance Cost

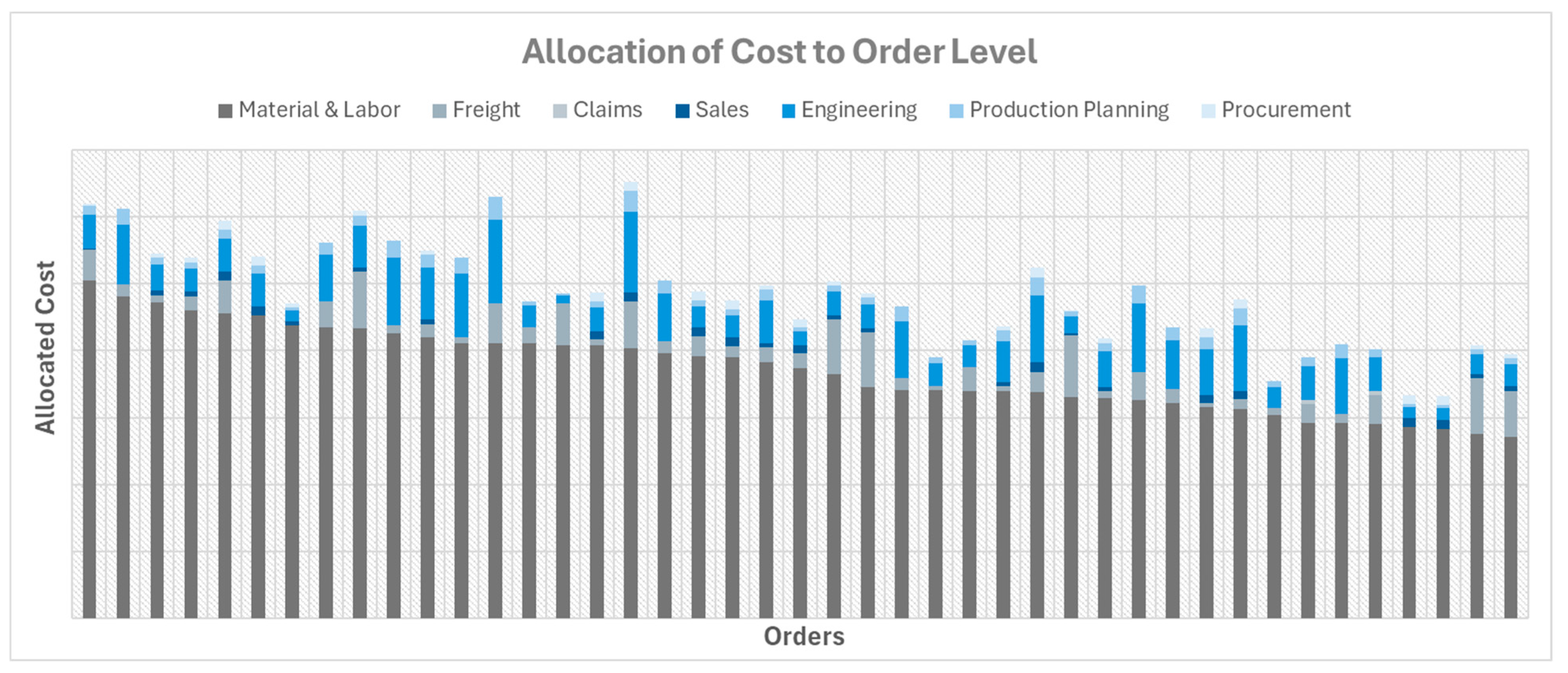

In the fifth phase, a cost perspective is incorporated into the model to assess how the variety-induced resource allocation can be the basis for estimating costs related to specific products and orders. Several layers of cost are considered, including material and labor, freight, and claims, as well as resource-based costs derived from the allocation of departmental activities across sales, construction, production planning, and procurement.

In Figure 10, an excerpt of invoiced orders illustrates the layering of costs that can be allocated to the different orders. By integrating these cost components, it becomes possible to calculate the contribution margin ratio with variance cost included that reflects the impact of product variety. This step enables a more comprehensive evaluation of the financial consequences of variance by linking direct costs with the resource allocations established in earlier phases. To avoid uncertainty in cost-driver estimation, the PVCM triangulates expert-based time and resource inputs with multiple internal data sources, including departmental capacity, historical cost records, and order-level profitability data. Although cost drivers are inherently company-specific and may involve subjective judgment, aligning them with the company’s actual cost structure and revenue patterns reduces bias and strengthens the reliability of the resulting cost allocations. By integrating multiple cost layers, this stage establishes the link between resource allocation and financial performance, thereby providing the basis for evaluating the CMRV.

Figure 10.

A small excerpt of invoiced orders from the case company. The different layers of cost are allocated to an order level.

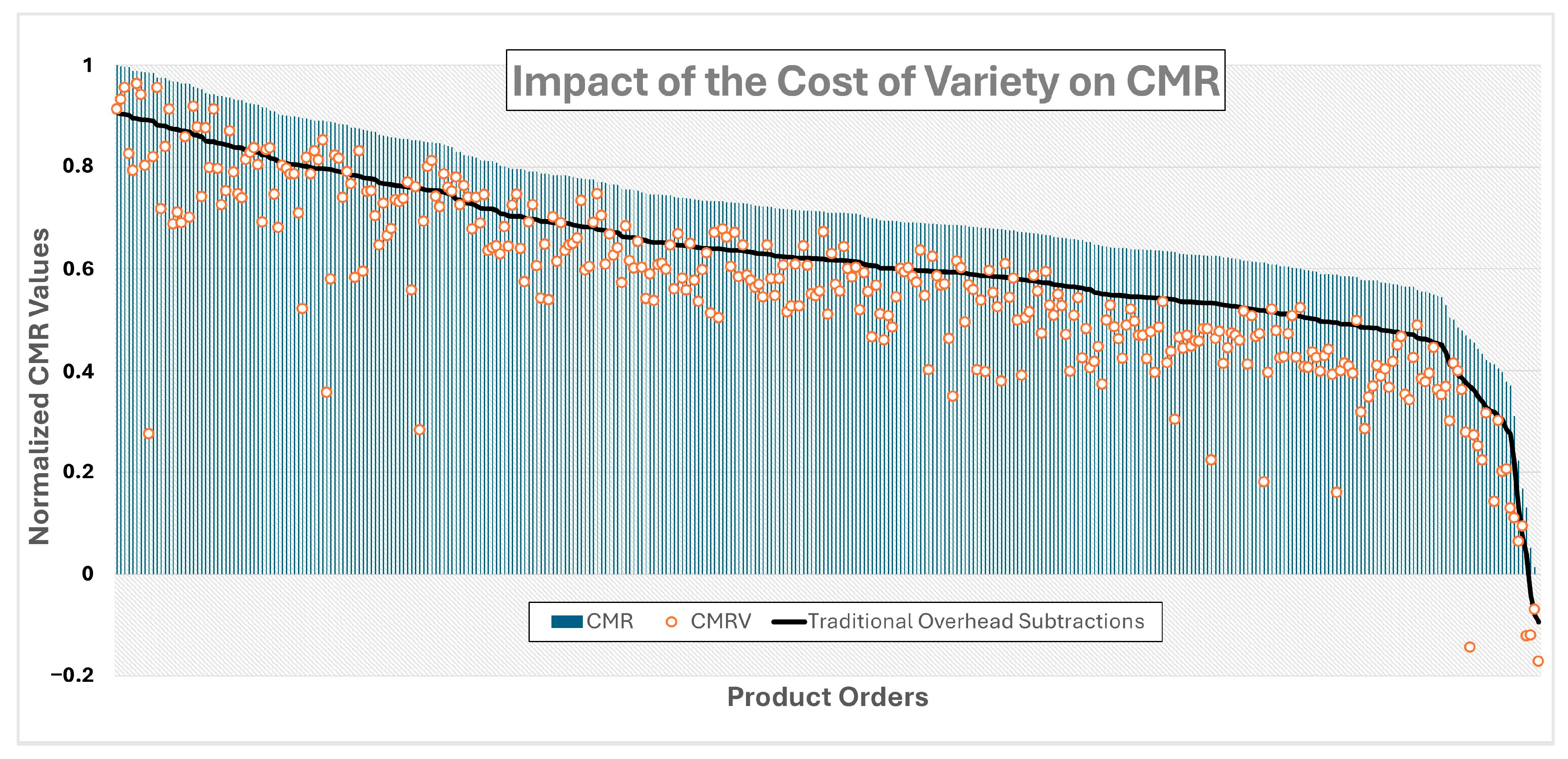

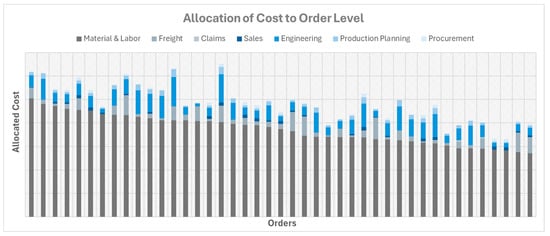

4.6. Evaluate Adjusted Contribution Margin Ratio

In the sixth phase, the final results are computed by applying the full method. Building on the previous stages, where resource-based costs were allocated relative to product variety, it is now possible to calculate and evaluate the contribution margin ratio for each invoiced order of the case company presented in Figure 11. The CMR considers only revenue and direct costs, illustrated by the blue bars in the chart. In addition, the adjusted measure, CMRV, is calculated by incorporating the cost of variety [4], represented by the orange dots in the figure. Finally, this value can be compared to the traditional approach of applying overhead costs as an average percentage of revenue [3], shown as the black line. In this case, only the overhead costs from the departments included in the model are considered. For confidentiality, the results in Figure 11 have been normalized, with a min-max normalization, and outliers removed.

Figure 11.

An overview of the model output when evaluating the adjusted contribution margin ratio (CMRV), with the CMR and the traditional approach of allocating overhead costs. The values are normalized and outliers removed for confidentiality reasons.

The graph demonstrates that including the cost of variety in the calculation of CMRV produces highly variable results across individual orders. In many cases, the outcomes are close to those generated by the traditional overhead allocation approach; however, in several other cases, they deviate considerably due to the influence of variety, as calculated by the model. The most significant deviation observed was 61.7% below and 7.3% above the traditional calculation of the CMRV. This variation illustrates how the cost of variety can significantly distort the evaluation of financial performance when relying on conventional overhead allocation methods. Furthermore, PVCM highlights the importance of considering product variety costs when making informed decisions about product design, thereby creating transparency on some of the potential economic benefits of introducing a modular product architecture. Examples could include highlighting the financial effects of commonality between specific products or the carry-over of specific modules and parts [57,58].

4.7. Summary of Findings

The application of the PVCM in the case company has demonstrated how the six stages can be operationalized in an industrial context. Through the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data, the product portfolio was analyzed and transformed into a parent–child hierarchy, allowing for the identification of unique parts and their corresponding abstraction levels. This provided the foundation for developing an allocation model that links resource use to variety-induced activities across sales, engineering, production planning, and procurement. Validation at the departmental level confirmed that the allocations were broadly consistent with available capacity, despite limitations in the data’s granularity in some departments.

By extending the allocation model with additional cost layers such as materials, labor, freight, and claims, it was possible to aggregate estimated costs at the order level and compute an adjusted contribution margin ratio that included the cost of variance. The comparison of CMRV with both traditional CMR and overhead-based methods revealed that product variety can significantly influence profitability assessments, with deviations exceeding 60% in some cases. These findings illustrate how this novel approach provides deeper insights into the cost of product and part variety, by increasing the granularity and accuracy of the cost allocation method and supporting design and managerial decisions by making the resource and cost implications of product variance explicit. Thus, improving cost transparency and supporting design decisions in the modular product development phase. This will be discussed in greater detail in the coming section.

5. Discussion

The findings from the industrial application demonstrate that the PVCM provides a more accurate and detailed estimation of variety-induced costs by linking resource consumption directly to components, subsystems, and complete products. This approach enables the aggregation of costs across the product portfolio and structure, revealing the costs associated with added product and part variety. In doing so, the method provides a quantifiable measure of the cost of variety, addressing key gaps in prior research by integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches to enhance transparency in assessing product and part variety costs [9,20,24].

From a design and engineering perspective, the PVCM enhances decision-making by allowing product developers to assess design alternatives at multiple levels of abstraction. Rather than evaluating cost performance solely at the product level, design engineers can now identify how individual components and modules contribute to or mitigate added product variety costs. This capability supports decisions on carry-over and reuse of existing solutions, providing a more detailed cost perspective for making modular product development decisions [10,19]. If applied in early-stage design, the PVCM relies on preliminary product structures, expert-based time estimates, and anticipated part variety when empirical data are incomplete. Prior work shows that activity-based approaches can support early product platform decisions by using estimated cost drivers, as illustrated by Park & Simpson [21], or by considering life-cycle costs for structurally related products, as discussed by Salonen et al. [7]. As more transactional data becomes available, the model can be progressively refined, increasing accuracy throughout the development process.

On an operational level, the method provides valuable insights to different levels of an organization. Design engineers can compare design alternatives and derive the actual cost impact of introducing or removing variety, which will act as decision support. Managers can visualize resource use across the product portfolio and assess the cost of introducing or phasing out product variants [59,60]. Upper-level management is equipped with a data-driven foundation for managing product portfolio complexity and investment focus for future product development.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. The current application focuses on selected life-cycle phases specific to this case, solely based on the availability of case company data, excluding later stages such as service, spare parts, and after-sales, which could further enrich the model [41]. Including additional cost layers from these phases would enhance the model’s robustness and strengthen its decision-support potential. Moreover, TDABC may involve a degree of subjectivity in its time estimates [36]; however, the underlying model is conceptually robust [61] and has been shown to outperform traditional costing methods in evaluating product profitability [36]. Moreover, it has been successfully implemented in numerous companies, leading to significant improvements in cost evaluation [39]. And the qualitative estimates that remain subject to uncertainty, potentially projecting less accurate results of the TDABC [54], can be mitigated by triangulating multiple data sources [48]. Regarding the dynamic nature of variety effects, the PVCM should be viewed as a partially dynamic model. The time-based activity estimates underlying the capacity cost rates are static, reflecting stable departmental assumptions. However, the transactional and structural data to which these estimates are applied are fully dynamic. As BOM structures change, new part numbers are introduced, or product variety evolves, the model automatically updates its resource allocations and cost propagation. Thus, while the time estimates remain fixed, the cost outcomes continuously adapt to real product-structure developments captured through live enterprise data.

Additionally, the method has so far been demonstrated in a single company, and future studies should explore its application in diverse industrial settings to assess its broader validity and generalizability, including the later stages of the value chain to provide a full life cycle cost analysis. Thus, confirming the method’s applicability, usefulness, and robustness across different industrial contexts. In larger, more complex manufacturing firms, where indirect costs represent a greater share of total costs and profit margins are typically lower, deviations in cost distribution could be even more pronounced than those observed in the case company. Moreover, including several new cases with different operating strategies might reveal varying cost implications [62]. Finally, the method can serve as a framework for model-based simulations aimed at identifying where modular product alternatives may yield greater cost and time savings across life-cycle phases. Future case studies should test its capability to evaluate the economic benefits of modularization in real industrial contexts. In addition, future work should explore whether PVCM can be adapted for scenario planning under uncertainty, such as variant proliferation or changing market requirements. While the method’s structure suggests this potential, its use for evaluating uncertain futures remains untested.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the proposed PVCM provides a comprehensive, data-driven framework for quantifying the cost of product variety across different levels of product abstraction. By integrating TDABC with hierarchical product structures and empirical enterprise data, the method addresses key limitations in existing cost allocation approaches, which are often restricted to specific life-cycle phases, lack sufficient granularity in representing product structures, and seldom integrate both qualitative and quantitative data within a unified model. The PVCM establishes a structured, bottom-up approach that links activities and variety-induced resource consumption across multiple abstraction levels throughout the life cycle phases, enhancing transparency in indirect costs and allowing for a more accurate economic evaluation of product design decisions.

Its application in an industrial case demonstrates that the method can effectively operationalize these principles in practice. Through the transformation of product structures into parent–child hierarchies and the development of a time-based resource allocation model, it was possible to identify unique components, quantify variety-induced resource use, and link departmental costs to specific activities in the value chain. When extended with the direct cost layers such as materials, labor, freight, and claims, the model enabled the calculation of an adjusted contribution margin ratio that revealed significant deviations, up to 60%, from conventional overhead-based assessments. These results demonstrate that product variety has a significantly greater impact on the evaluation of actual cost distribution than traditional costing systems can reveal.

Ultimately, the PVCM advances the field by providing a combined quantitative and qualitative method for assessing the true cost of product variety in high-customization contexts. It enhances the accuracy of cost allocation, increases transparency in indirect cost drivers, and supports both design engineers and decision-makers in balancing customization, modularity, and internal product variety. It serves as a critical step toward data-informed, economically grounded modular product development, addressing the critical challenge of balancing the cost of internal and external product variety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N., J.M.G., C.K.F.C., and N.H.M.; Review, M.N., J.M.G., C.K.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.N., J.M.G., C.K.F.C., and N.H.M.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, C.K.F.C. and N.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the development and validation of this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Thomas B. Thriges Foundation and the Industriens Foundation as part of the AI Supported Modular Design and Implementation project (AIMO).

Institutional Review Board

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the aforementioned foundations, as well as the Technical University of Denmark, for providing the funding and facilities necessary to carry out this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The foundations had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kwapisz, J.; Infante, V.; Cameron, B.G. Commonality opportunity search in industrial product portfolios Virginia Infante. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2019, 81, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMaraghy, H.; Schuh, G.; Elmaraghy, W.; Piller, F.; Schönsleben, P.; Tseng, M.; Bernard, A. Product variety management. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 62, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.A.; Perumal, A. Waging War on Complexity Costs: Reshape Your Cost Structure, Free Up Cash Flows, and Boost Productivity by Attacking Process, Product and Organizational Complexity; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hvam, L.; Hansen, C.L.; Forza, C.; Mortensen, N.H.; Haug, A. The reduction of product and process complexity based on the quantification of product complexity costs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windheim, M.; Hackl, J.; Gebhardt, N.; Krause, D. Assessing Impacts of Modular Product Architectures on The Firm: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 14th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 16–19 May 2016; p. 1445. [Google Scholar]

- Israelsen, P.; Jørgensen, B. Decentralizing decision making in modularization strategies: Overcoming barriers from dysfunctional accounting systems. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, M.; Otto, K.H.; Otto, K. Effecting Product Reliability and Life Cycle Costs with Early Design Phase Product Architecture Decisions. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2008, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlenspiel, K.; Kiewert, A.; Lindemann, U. Cost-Efficient Design; ASME International: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, E.; Fuchs, C.; Hamraz, B.; Windheim, M.; Rennpferdt, C.; Schwede, L.-N.; Krause, D. Knowledge-Based Decision Support for Concept Evaluation Using the Extended Impact Model of Modular Product Families. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windheim, M.; Gebhardt, N.; Krause, D. Towards a Decision-Making Framework for Multi-Criteria Product Modularization in Cooperative Environments. Procedia CIRP 2018, 70, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, K.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Simpson, T.W.; Krause, D.; Ripperda, S.; Ki Moon, S. Global Views on Modular Design Research: Linking Alternative Methods to Support Modular Product Family Concept Development. J. Mech. Des. 2016, 138, 071101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, E.; Fuchs, C.; Hamraz, B.; Windheim, M.; Schwede, L.-N.; Krause, D. Investigating the effects of modular product structures to support design decisions in modularization projects. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Singapore, 14–17 December 2020; Volume 2020, pp. 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.A.; Abdul-Nour, G. Integrating Modular Design Concepts for Enhanced Efficiency in Digital and Sustainable Manufacturing: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, E.; Krause, D. Long-term effects of modular product architectures: An empirical follow-up study. In Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 84, pp. 731–736. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen, N.H.; Bertram, C.A.; Lundgaard, R. Achieving long-term modularization benefits: A small- and medium-sized enterprise study. Concurr. Eng. Res. Appl. 2019, 27, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, J.; Israelsen, P.; Jørgensen, B. Activity-based costing as a method for assessing the economics of modularization-A case study and beyond. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 103, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripperda, S.; Krause, D. Cost Effects of Modular Product Family Structures: Methods and Quantification of Impacts to Support Decision Making. J. Mech. Des. Trans. ASME 2017, 139, 021103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtherr, F.; Wouters, M. Extending target costing to include targets for R&D costs and production investments for a modular product portfolio—A case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 231, 107871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackl, J.; Krause, D.; Otto, K.; Windheim, M.; Moon, S.K.; Bursac, N.; Lachmayer, R. Impact of Modularity Decisions on a Firm’s Economic Objectives. J. Mech. Des. Trans. ASME 2020, 142, 041403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altavilla, S.; Montagna, F. A Product Architecture-Based Framework for a Data-Driven Estimation of Lifecycle Cost. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2019, 141, 051007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Simpson, T.W. Toward an activity-based costing system for product families and product platforms in the early stages of development. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Simpson, T.W.; Siddique, Z. Product family design and platform-based product development: A state-of-the-art review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2007, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, T.W.; Marion, T.; De Weck, O.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Kokkolaras, M.; Shooter, S.B. Platform-based Design and Development: Current Trends and Needs in Industry. In Proceedings of the ASME 2006 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences & Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 10–13 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nørgaard, M.; Grønvald, J.M.; Christensen, C.K.F.; Mortensen, N.H. How Traditional Costing Methods Hinder the Development of Modular Product Architectures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, J.; Bao, H.; Xia, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, G. Cost-Sensitive Neighborhood Granularity Selection for Hierarchical Classification. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 4471–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gu, W.; Shang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, G. Research on dynamic job shop scheduling problem with AGV based on DQN. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altavilla, S.; Montagna, F.; Cantamessa, M. A Multilayer Taxonomy of Cost Estimation Techniques, Looking at the Whole Product Lifecycle. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2018, 140, 030801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sang, H.; Meng, L.; Jiang, X.; Lu, C. Knowledge- and data-driven hybrid method for lot streaming scheduling in hybrid flowshop with dynamic order arrivals. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 184, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Meng, L.; Sang, H.; Jiang, X. Multi-objective scheduling for surface mount technology workshop: Automatic design of two-layer decomposition-based approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 7570–7590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.L. Development of Industrial Variant Specification Systems; IKON Tekst & Tryk A/S; Technical University of Denmark: Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rudberg, M.; Wikner, J. Mass customization in terms of the customer order decoupling point. Prod. Plan. Control 2004, 15, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvam, L.; Mortensen, N.H.; Riis, J. Product Customization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, F.; Forza, C.; Rungtusanatham, M. Modularity, product variety, production volume, and component sourcing: Theorizing beyond generic prescriptions. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 549–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørgaard, M.; Grønvald, J.M.; Christensen, C.K.F.; Mortensen, N.H. Challenges in product variant costing—A case study. In Proceedings of the Design Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024; Volume 4, pp. 3003–3012. [Google Scholar]

- Fadeyi, J.A.; Monplaisir, L. Instilling lifecycle costs into modular product development for improved remanufacturing-product service system enterprise. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 246, 108404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguenza-Guzman, L.; Van Den Abbeele, A.; Vandewalle, J.; Verhaaren, H.; Cattrysse, D. Recent Evolutions in Costing Systems: A Literature Review of Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing. Review of Business and Economic Literature 2013. Available online: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/275810 (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Park, J.; Simpson, T.W. Development of a production cost estimation framework to support product family design. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2005, 43, 731–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.K.; Chen, S.L. Cost estimation of a service family based on modularity. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 3059–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Anderson, S.R. Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing; Harvard Business Review: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, K.G.; Schmidt, M.; Yildiz, T.; Meyer, M. Introducing a framework to generate and evaluate the cost effects of product (family) concepts. In Proceedings of the Design Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1907–1916. [Google Scholar]

- Hackl, J.; Krause, D. Towards an Impact Model of Modular Product. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Schwede, L.N.; Greve, E.; Krause, D.; Otto, K.; Moon, S.K.; Albers, A.; Kirchner, E.; Lachmayer, R.; Bursac, N.; Inkermann, D.; et al. How to Use the Levers of Modularity Properly-Linking Modularization to Economic Targets. J. Mech. Des. Trans. ASME 2022, 144, 071401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisenbacher, S.; Goevert, K.; Lindemann, U.; Moertl, M. Supporting Product Platform Decisions with Lifecycle Costing. In Proceedings of the IEEM2016: 2016 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Bali, Indonesia, 4–7 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Elgh, F.; Erkoyuncu, J.A.; Bankole, O.; Goh, Y.; Cheung, W.M.; Baguley, P.; Wang, Q.; Arundachawat, P.; Shehab, E.; et al. Cost engineering for manufacturing: Current and future research. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2012, 25, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, M.; Stadtherr, F. Cost management and modular product design strategies. In The Routledge Companion to Performance Management and Control; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 54–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, T. Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches: Some Arguments for Mixed Methods Research. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 56, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigsgaard, K.V.; Agergaard, J.K.; Bertram, C.A.; Mortensen, N.H.; Soleymani, I.; Khalid, W.; Hansen, K.B.; Mueller, G.O. Structuring and Contextualizing Historical Data for Decision Making in Early Development. In Proceedings of the Design Society: DESIGN Conference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, C. Research Methods for Operations Management, 2nd ed.; Karlsson, C., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, A.K.; Agarwal, R. Dimensional modeling for a data warehouse. ACM SIGSOFT Softw. Eng. Notes 2001, 26, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kourik, J.L. Data Warehouse Snowflake Design and Performance Considerations in Business Analytics. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2015, 6, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisman, A.; Zimányi, E. Conceptual Data Warehouse Design. In Data Warehouse Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Harlou, U. Developing Product Families Based on Architectures Contribution to a Theory of Product Families. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Anderson, S.R. Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing: A Simpler and More Powerful Path to Higher Profits; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Plenborg, T.; Kinserdal, F. Financial Statement Analysis: Valuation, Credit Analysis, Performance Evaluation, 2nd ed.; Fagbokforlaget: Bergen, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Horngren, C.T.; Datar, S.M.; Rajan, M.V. Cost Accounting a Managerial Emphasis, 13th ed.; Pearson Internation Edition: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, R.; Cameron, B.G.; Crawley, E.F. Divergence and lifecycle offsets in product families with commonality. Syst. Eng. 2013, 16, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, B.G.; Rhodes, R.; Boas, R.; Crawley, E.F. Divergence in Platform Commonality: Examination of Potential Cost Implications. In Proceedings of the 11th International Design Conference—Design 2010, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 17–20 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trattner, A.; Hvam, L.; Forza, C.; Nadja Lee Herbert-Hansen, Z. Product complexity and operational performance: A systematic literature review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2019, 25, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.L.; Mortensen, N.H.; Hvam, L. Calculation of complexity costs—An approach for rationalizing a product program. In NordDesign 2012, Proceedings of the 9th NordDesign Conference, Aalborg, Denmark, 22–24 August 2012; Aalborg University: Aalborg, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, T.; Madsen, D.Ø. The historical evolution and popularity of activity-based thinking in management accounting. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2020, 16, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, S.M.; Hvam, L. Understanding the impact of non-standard customisations in an engineer-to-order context: A case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 6780–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).