Abstract

Advances in distributed electric propulsion and urban air mobility technologies have spurred a surge of research on electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL) aircraft. Distributed Multi-Propeller Tilting-Wing (DMT) eVTOL configurations offer higher forward flight speed and efficiency. However, aerodynamic challenges during the transition phase have limited their practical application. This study develops a high-fidelity body-fitted mesh CFD numerical simulation method for flow field calculations of DMT aircraft. Using the reverse overset assembly method and CPU-GPU collaborative acceleration technology, the accuracy and efficiency of flow field simulations are enhanced. Using the established method, the influence of dynamic tilting speeds on the flow field of this configuration is investigated. This paper presents the variations in the aerodynamic characteristics of the tandem propellers and tilt-wings throughout the full tilt process under different tilting speeds, analyzes the mechanisms behind reductions in the propeller’s aerodynamic performance and tilt-wing lift overshoot, and conducts a detailed comparison of flow field distribution characteristics under fixed-angle tilting, slow tilting, and fast tilting conditions. The study explores the influence mechanism of tilting speed on blade tip vortex-lifting surface interactions and interference between tandem propellers and tilt-wings, providing valuable conclusions for the aerodynamic design and safe transition implementation of DMT aircraft.

1. Introduction

In the field of low-altitude flight, rotorcraft have been widely used in various scenarios due to their unique vertical take-off and landing capability, flexible maneuverability, and broad adaptability to operational environments. However, the maximum forward flight speed and efficiency of traditional rotorcraft, such as single-rotor helicopters with tail rotors, are limited by their configurations. Efforts have been devoted to developing new high-speed, high-efficiency rotorcraft configurations. Examples like the X2 coaxial rigid rotor helicopter [1] and the V-22 tiltrotor [2] have improved maximum flight speeds; however, drag from large rotors and power attenuation in transmission systems keep their forward speed and cruise efficiency significantly lower than those of fixed-wing aircraft.

In recent years, advances in aviation electric drive technology have greatly enhanced the flexibility of aircraft configuration design. eVTOL aircraft, which adopt Distributed Electric Propulsion (DEP) instead of carbon-based fuels, have become a key carrier of the low-altitude economy [3]. By combining the vertical take-off and landing capability of helicopters with the efficient cruising of electric aircraft, eVTOL aircraft demonstrate advantages in environmental friendliness, comfort, and cost-effectiveness, making them an important development direction for rotorcraft [4]. The Disturbed Multi-Propeller Tilting-Wing (DMT) aircraft is a new evolution of the traditional tiltrotor configuration, integrating DEP technology with a tilt-wing layout [5]. It features two tandem tiltable wings, with multiple small motor-driven propellers mounted on the leading edges of both wings, tilting synchronously with the wings. The wings of the DMT aircraft are positioned in the wake of the multiple propellers, which increases the effective inflow velocity of the wings and maintains high lift during low-speed flight. At large tilt angles/angles of attack, the propeller slipstream reduces the wing angle of attack, delaying wing stall and ensuring good flight stability. During the tilting process, the direction of the propeller wake remains parallel to the wing chord line, minimizing propeller–wing aerodynamic interference and effectively reducing downwash loads. The DMT aircraft not only possesses vertical take-off, landing, and hovering capabilities but also achieves faster forward flight speed and higher flight efficiency [6].

However, the complex configuration, high-degree-of-freedom component motion, and multi-flight modes of the DMT aircraft give rise to more severe aerodynamic interference challenges compared to traditional rotorcraft [7], specifically manifested in three key aspects: (1) Strong aerodynamic interference among multiple static and dynamic components, encompassing interactions between multiple propellers, between propellers and tilting wings, and across the tandem tilting wings. (2) Severe wing stall occurs at large tilt angles/angles of attack, and flow separation induces unsteady flow field development. (3) During dynamic transition flight, the tilting speeds of propellers and wings introduced by the tilting motion exacerbate unsteady aerodynamic effects, making the variation in the overall aircraft’s aerodynamic characteristics difficult to predict. Without in-depth research on the unsteady interference characteristics and flow mechanisms between components across all flight modes, safe transition cannot be achieved, nor can the design advantages of the new configuration be fully exploited. Thus, investigating the unsteady aerodynamic characteristics of DMT aircraft holds significant academic significance and practical application value.

With advances in computer technology and the increasing maturity of numerical methods, numerical simulation has gradually replaced costly wind tunnel testing as the primary approach for rotorcraft flow field research. Early flow field solution methods, typically engineering-simplified blade element momentum theory and medium-accuracy vortex methods, have commonly been used for performance evaluation [8] and overall aircraft design [9]. However, the accuracy of these methods is limited by simplified governing equations and a lack of spatial flow field details, making them inadequate for calculating the aerodynamic characteristics of aircraft under complex interference and highly unsteady conditions—especially dynamic tilting and post-stall states.

The high-fidelity CFD method based on the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations [10] can accurately capture detailed flow features from rotor tip vortices to boundary layers. It has become a key tool for studying the aerodynamic interference mechanisms of rotorcraft and has been effectively applied in simulating the rotor tip vortex wake flow fields [11], full helicopter flow fields [12], and unsteady flow fields of modern complex-configured rotors [13]. For simulating moving components, the overset mesh CFD method enables unsteady numerical simulation by independently generating body-fitted meshes for all components and transferring flow field variables through boundary interpolation. It offers the advantages of accurate boundary description and precise capture of near-wall flow fields and has been widely applied in numerical simulations of rotor–wing aerodynamic interference for tiltrotor aircraft in hovering [14], transition [15], and forward flight [16] phases, with its accuracy validated through wind tunnel tests [17]. Despite these advances, few studies have focused on the aerodynamic interference characteristics of tilt-wing aircraft during dynamic transition. The variation laws of the aerodynamic characteristics of each component under different flight states have not been systematically analyzed, and an in-depth exploration of the interaction mechanisms between key components remains to be carried out.

When traditional CFD methods are applied to DMT aircraft numerical simulations, the unique aerodynamic characteristics—including unsteady component motion, complex aerodynamic interference between parallel propellers/tandem wings, and highly unsteady flow fields during transition—lead to issues such as inaccurate motion description, low computational efficiency, and poor algorithm stability. The aerodynamic performance of distributed multi-propellers was calculated using the vortex lattice method and the steady momentum source CFD method, respectively [18]. However, the results for unsteady rotating blades deviated by over 10% from ground test data [19]. In 2018, Droandi et al. [20] from Airbus conducted an aerodynamic modeling and interference analysis of the Vahana configuration under different flight states using a RANS solver with the Spalart–Allmaras (S-A) turbulence model. Due to excessive computational resource consumption, only steady-state simulations were performed. Stoll and Mikic [21] performed quasi-steady full-aircraft numerical simulations of the Joby aircraft using the body-fitted mesh CFD method. Given that high-fidelity simulations inherently require substantial mesh resources, precise simulation of the aircraft’s numerous propellers demanded approximately 200 million mesh cells—even with a symmetric plane boundary—resulting in enormous computational resource consumption. Notably, few studies have employed high-fidelity CFD methods to investigate the dynamic transition phase involving co-tilting wings and rotors, and the interference mechanism between parallel propellers and serial wings during this critical phase remains unclear.

In terms of flow field simulation acceleration technologies, as the growth rate of computational demands has outpaced the improvement in the computing capacity of a single Central Processing Unit (CPU), research in this field has focused on the design of parallel algorithms capable of utilizing multiple processing units simultaneously. Duvigneau et al. parallelized the UM3SIS code using the Message Passing Interface (MPI) tool, achieving multi-level parallel acceleration in the transonic airfoil optimization of commercial aircraft and improving computational efficiency [22]. However, the speedup ratio gradually decreased with the increase in the number of CPU cores. Currently, CPU parallel acceleration methods are limited by inter-core communication processes, and their acceleration effect has reached a growth bottleneck [23]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop Graphics Processing Unit (GPU)-based acceleration technology and integrate it with the CPU for heterogeneous parallel acceleration, thereby further improving the computational efficiency of flow field simulations [24].

This study develops a high-fidelity overset mesh CFD method applicable to DMT aircraft. It constructs an overset mesh system for distributed multi-propellers and tandem tiltable wings and integrates CPU-GPU heterogeneous parallel acceleration technology. This integration enables an accurate description of the full-aircraft multi-component motion and an efficient numerical simulation of its flow fields. By using the established high-fidelity method, in-depth numerical simulations of the unsteady flow field for DMT aircraft during dynamic transition are carried out. This study captures the detailed flow features during dynamic tilting. It clarifies the variation laws of propeller/wing aerodynamic characteristics throughout the dynamic tilting process, analyzes the influence of different tilting speeds on the interference flow field between parallel propellers and tandem tilt-wings, and reveals the interference mechanism between serial propellers/wings of DMT aircraft in dynamic transition states.

2. Model and Numerical Method

2.1. Geometric Modeling of the DMT Aircraft

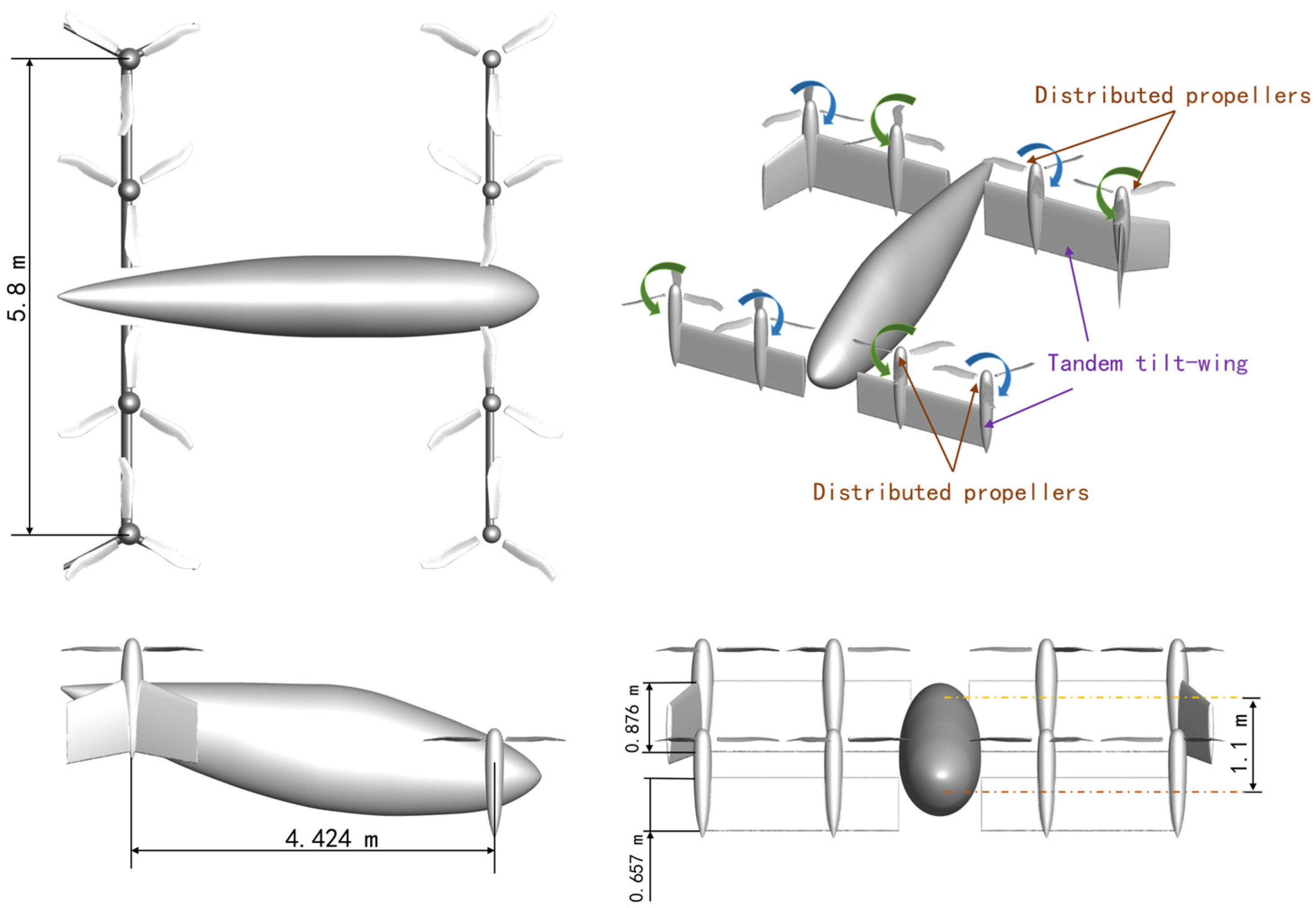

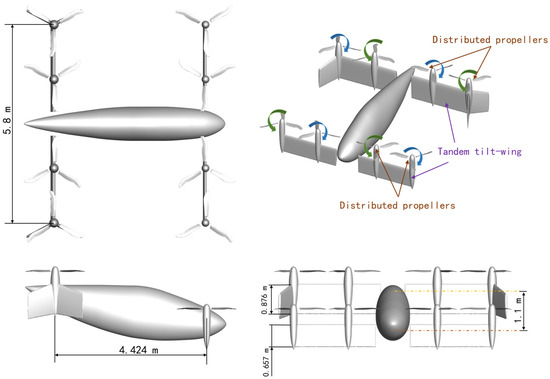

The DMT aircraft selected in this study is an eVTOL aircraft designated as the Vahana, which is under development by the Advanced Projects Outpost of Airbus in Silicon Valley [25]. This aircraft is configured with two tilt-wings, each equipped with four propellers that can tilt synchronously with the tilt-wings. A dedicated computational model for the aircraft was independently established based on the geometric dimensions of the Airbus A3 Vahana [26] and relevant data retrieved from evtol.news, as illustrated in Figure 1. It should be noted that the core focus of this study is on the overall aerodynamic characteristics of the tandem propellers and tilting wings during dynamic tilt transition maneuvers, as well as the effects of the tilting rate on these characteristics. Therefore, complex components such as landing gear, transmission mechanisms, and control flaps were simplified during model establishment to avoid unnecessary computational complexity and ensure that the analysis remains focused on the key research objectives. The front and rear tilting surfaces are designated as the canard and wing, respectively. Each tilt-wing is equipped with two parallel propellers rotating in opposite directions. The airfoils of the canard and wings of the Vahana aircraft adopt the NACA 4415 airfoil. Both the canard and wing have an installation angle, twist angle, and sweep angle of 0°. The half span of both the canard and wing is equal, with Lc = Lw = 2.9 m. And the chord lengths of the canard and wing are cc = 0.657 m and cw = 0.876 m, respectively. The tilt axes of both the canard and wing are located at the 1/4 chord line of the root section airfoil. The horizontal distance between the tilt axes of the canard and wing is 4.424 m, and the vertical distance is 1.1 m.

Figure 1.

DMT aircraft model.

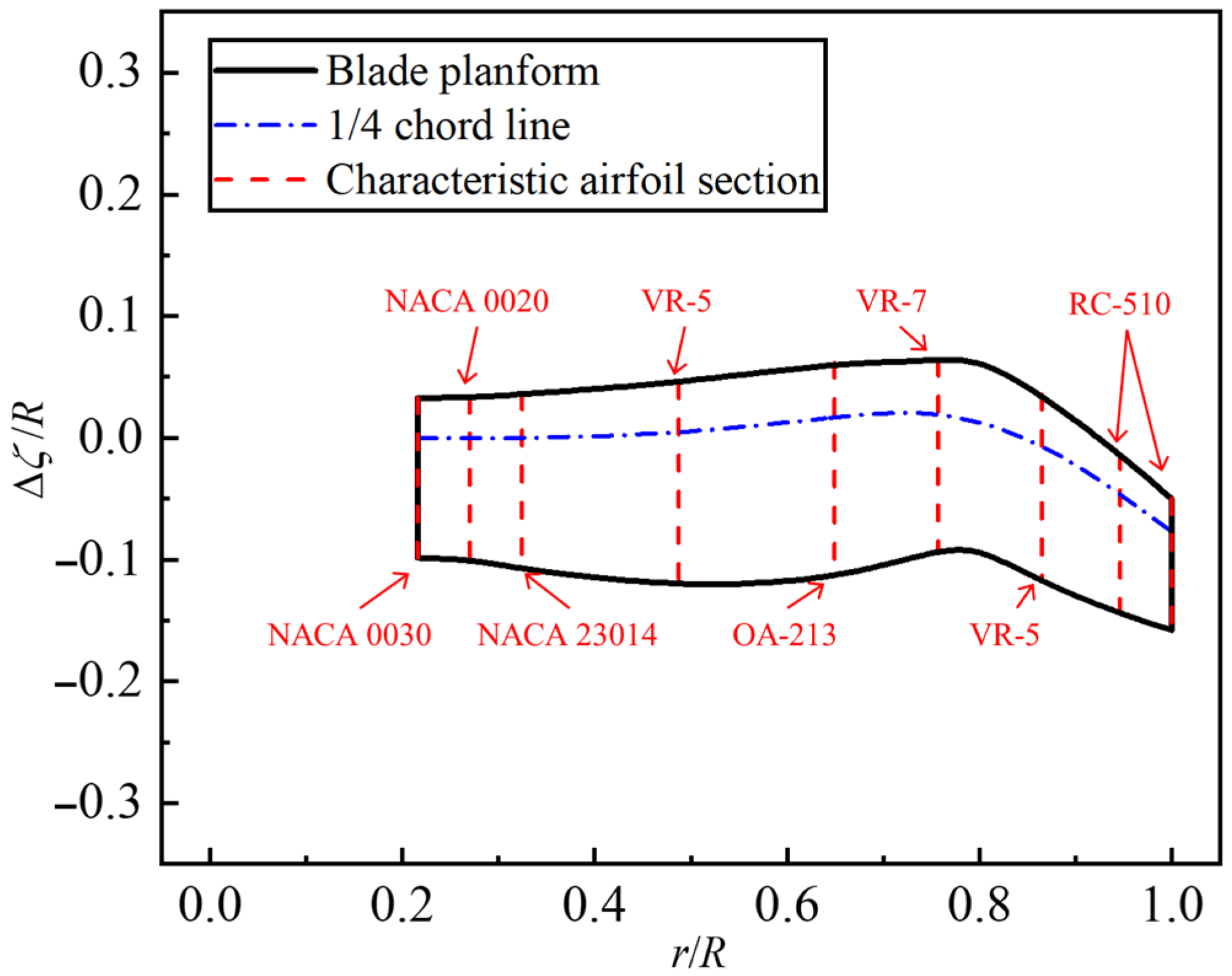

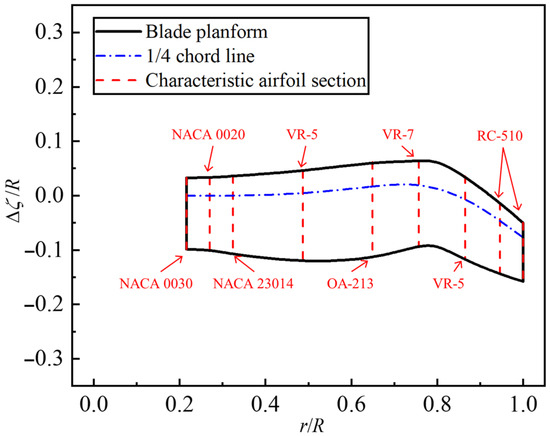

Since the aerodynamic profile of the propeller blades has not been publicly disclosed, an alternative propeller blade configuration was adopted for the computational simulations. In this study, the tiltrotor aircraft blades optimized by Droandi and Gibertini were implemented for the DMT aircraft, as this configuration achieves a favorable balance of aerodynamic efficiency across the hovering, climbing, and cruising flight phases [27]. For the present study, each individual propeller of the target aircraft is configured with three blades, features a radius of R = 0.75 m, and operates at a rotational speed of 2000 rpm. The planform of the blades is shown in Figure 2, and the specific parameters are given in Table 1, where R denotes the propeller radius; r is the distance from a certain section to the rotation axis; c represents the chord length; θ stands for the airfoil installation angle; and ζ indicates the 1/4 chord position.

Figure 2.

Planform of DMT aircraft propeller blades.

Table 1.

Parameters of the DMT aircraft propeller blades.

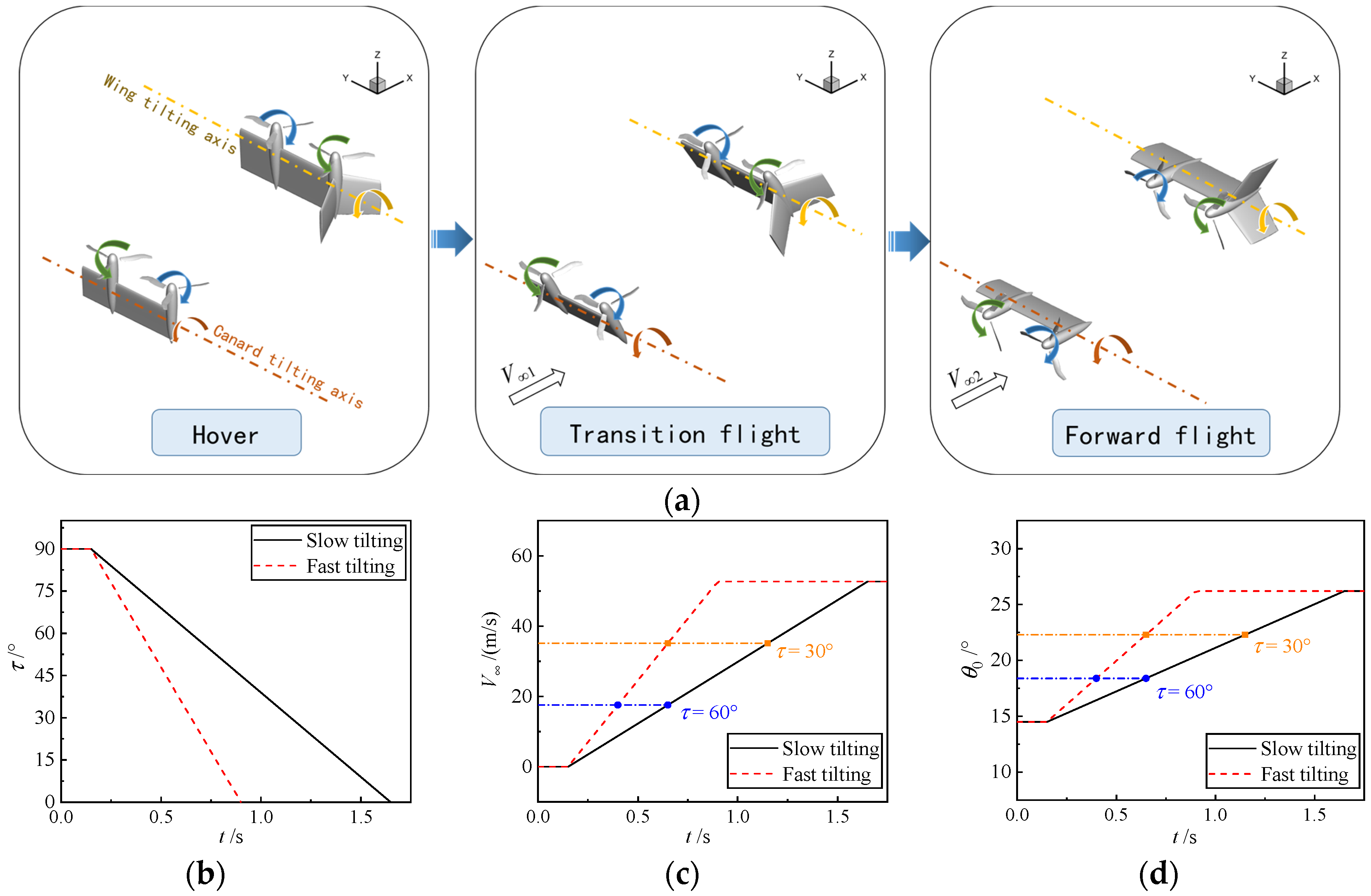

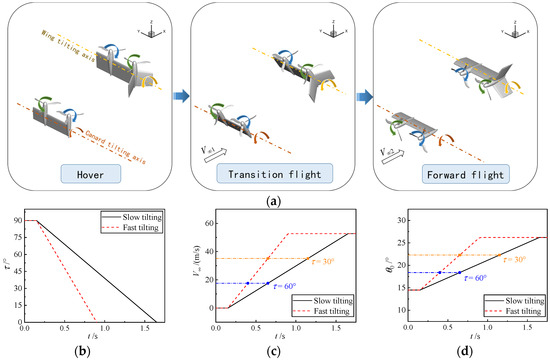

In the motion simulation and flow field calculation of the full dynamic transition state, considering the symmetry of the DMT aircraft configuration and flow field environment, a single-sided tandem multi-propeller/wing is selected as the research object to improve computational efficiency. To ensure the accuracy of the flow field simulation, the time scale of the iterative time step is the azimuth angle of blade rotation. However, the entire tilting process during actual flight is relatively long, making direct numerical simulation impractical. Therefore, this study assumes that the dynamic tilting process is completed when the propellers rotate 50 cycles and 25 cycles to investigate the influence of different tilting speeds on the flow field.

The transition strategy is as follows: the airframe undergoes uniformly accelerated motion while the tilting speed remains constant, with the speed accelerating from 0 m/s to 52.7 m/s as the tilt angle changes from 90° (hover) to 0° (forward flight); the canard and wing tilt synchronously with the same propeller control inputs; and the angle of attack α is maintained at 0°. Initially, the propellers rotate 5 cycles in hover to ensure the computational stability and accuracy of the flow field at the start of tilting. The computational model and variation curves of tilting angle τ, forward flight speed V∞, and collective pitch θ0 with computational time throughout the tilting process are shown in Figure 3. The ground coordinate system, the tilt axes of the canard and wing, and the rotation direction of each propeller are marked in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

Computational model and parameter variation curves of the tilting process. (a) Multi-propellers and tilting-wings model; (b) Tilting angle τ; (c) Forward flight speed V∞; (d) Collective pitch θ0.

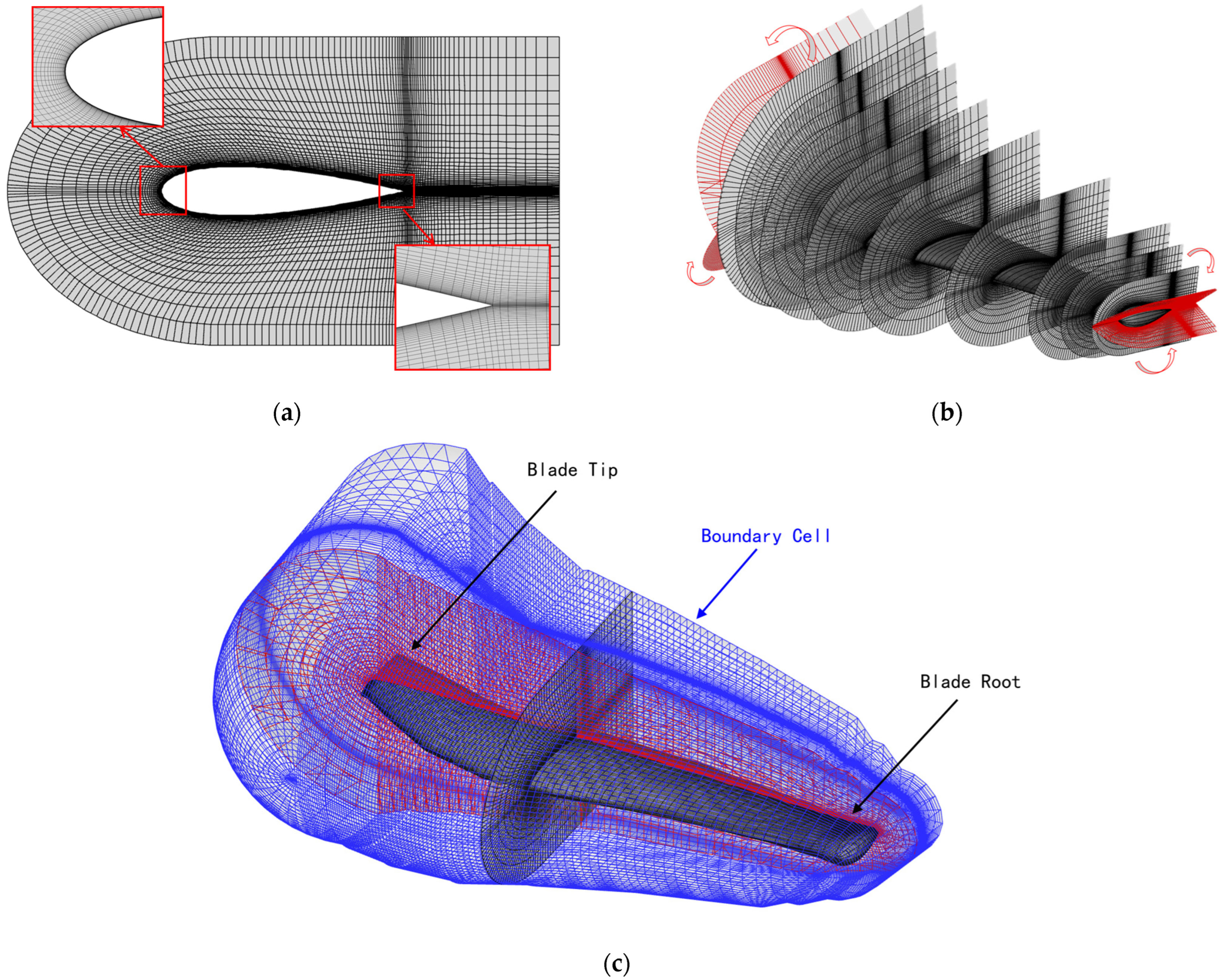

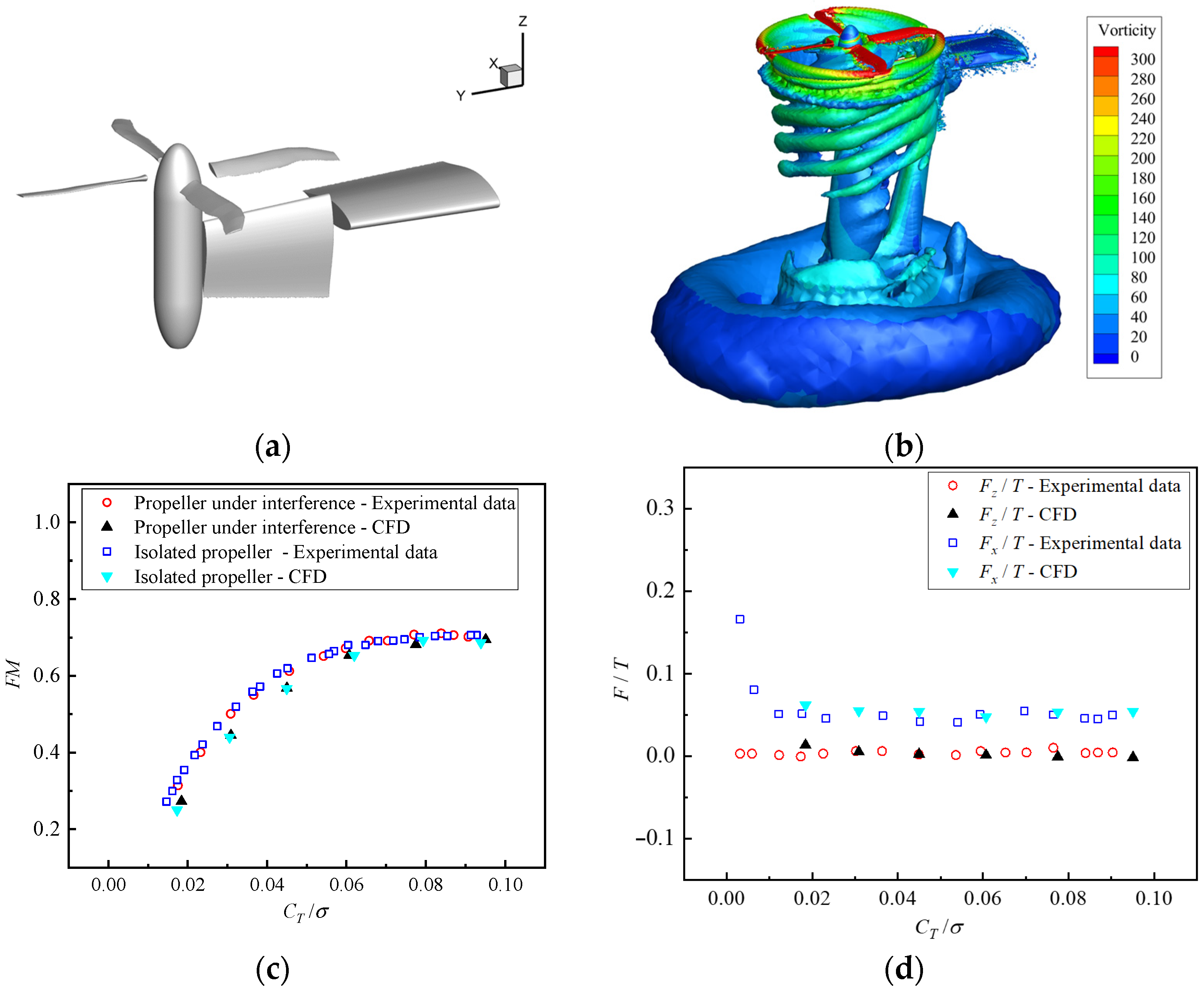

2.2. Construction of the Overset Mesh System

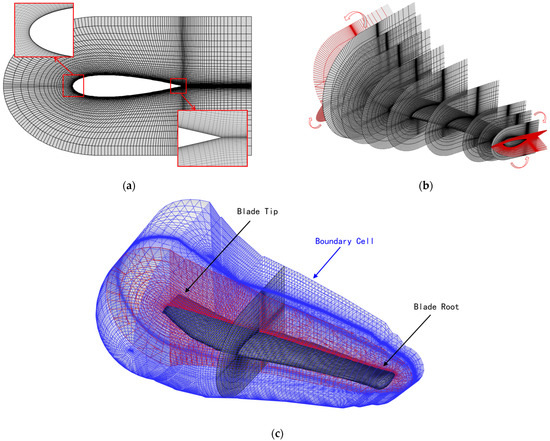

In the numerical simulation based on the overset mesh system, mesh quality and overset assembly methods significantly affect the accuracy of unsteady flow field calculations. To improve the precision of blade tip vortex capture, the structured mesh of the propeller blades in this study adopts the C-O type mesh generation method. The structured mesh surrounding the 2D airfoil of the blades is generated using the elliptic equation mesh generation method [28]. The 3D blade section mesh is obtained from the 2D airfoil according to parameters such as twist angle, chord length, and 1/4 chord position distribution. The tip airfoil mesh is folded around the airfoil camber line to form the 3D propeller blade mesh. Figure 4 presents the C-O type 3D mesh of the DMT aircraft propeller blades generated in this study. Figure 4a presents the structured mesh of the two-dimensional airfoil NACA0020, and the process of generating the blade mesh from each airfoil via the folding method is illustrated in Figure 4b. Figure 4c shows the final generated C-O type blade mesh.

Figure 4.

C-O type 3D mesh of the DMT aircraft blades. (a) Airfoil structured mesh; (b) blade mesh generation process; (c) blade mesh generated by the folding approach.

When solving the dynamic boundary problem in the unsteady motion simulation of the DMT aircraft, the traditional overset assembly method faces stability and efficiency issues when dealing with complex oversets among multiple components. This study adopts a reverse overset mesh method, which we developed previously, combining hole-cutting and donor cell search in reverse order [29]. This approach first performs a donor cell search to determine the existence and location of donor cells, then classifies the mesh based on the classification criteria parameter, and finally defines the chimera boundary using the maximum hole method. Through the aforementioned method, it is ensured that donor cells for boundary meshes always exist and are not the meshes themselves, thereby avoiding the problem of isolated points in the interpolation boundary. Compared with the potential multiple donor cell searches in traditional overset methods, this approach only requires one hole-cutting operation to determine the accurate overset boundary, improving the computational accuracy and efficiency of mesh overset assembly among the multiple propellers, canard, wing, and background of the DMT aircraft.

Based on the established C-O type blade meshes and the tilt-wing meshes generated via ANSYS MESH 2023 R1, the overset mesh system for the DMT aircraft was established. Table 2 presents the thrust coefficient (CT) of the propeller and lift coefficient (CL) of the canard calculated using the CFD method in this study across three distinct mesh resolutions. The propeller was simulated under a hovering condition with 10 revolutions, while the canard was calculated in a steady forward flight state (V∞ = 52.7 m/s, α = 0°). The results confirm mesh resolution convergence for the key aerodynamic coefficients. To balance computational efficiency and accuracy, a medium-sized mesh was selected for this work. Due to the similarity in structure and dimensions between the wing and the canard, the wing mesh was generated using the same element size as that of the canard. Owing to the large chord length of the wing and the extended mesh refinement region, the total number of mesh elements amounted to 13,515,746. Mesh quality was validated using the mesh quality analysis module in ANSYS MESH. The results show that the average cell quality of the canard and wing meshes is 0.8469 and 0.8434, respectively, both of which satisfy the quality criteria for high-fidelity CFD simulations.

Table 2.

The convergence of the mesh resolution.

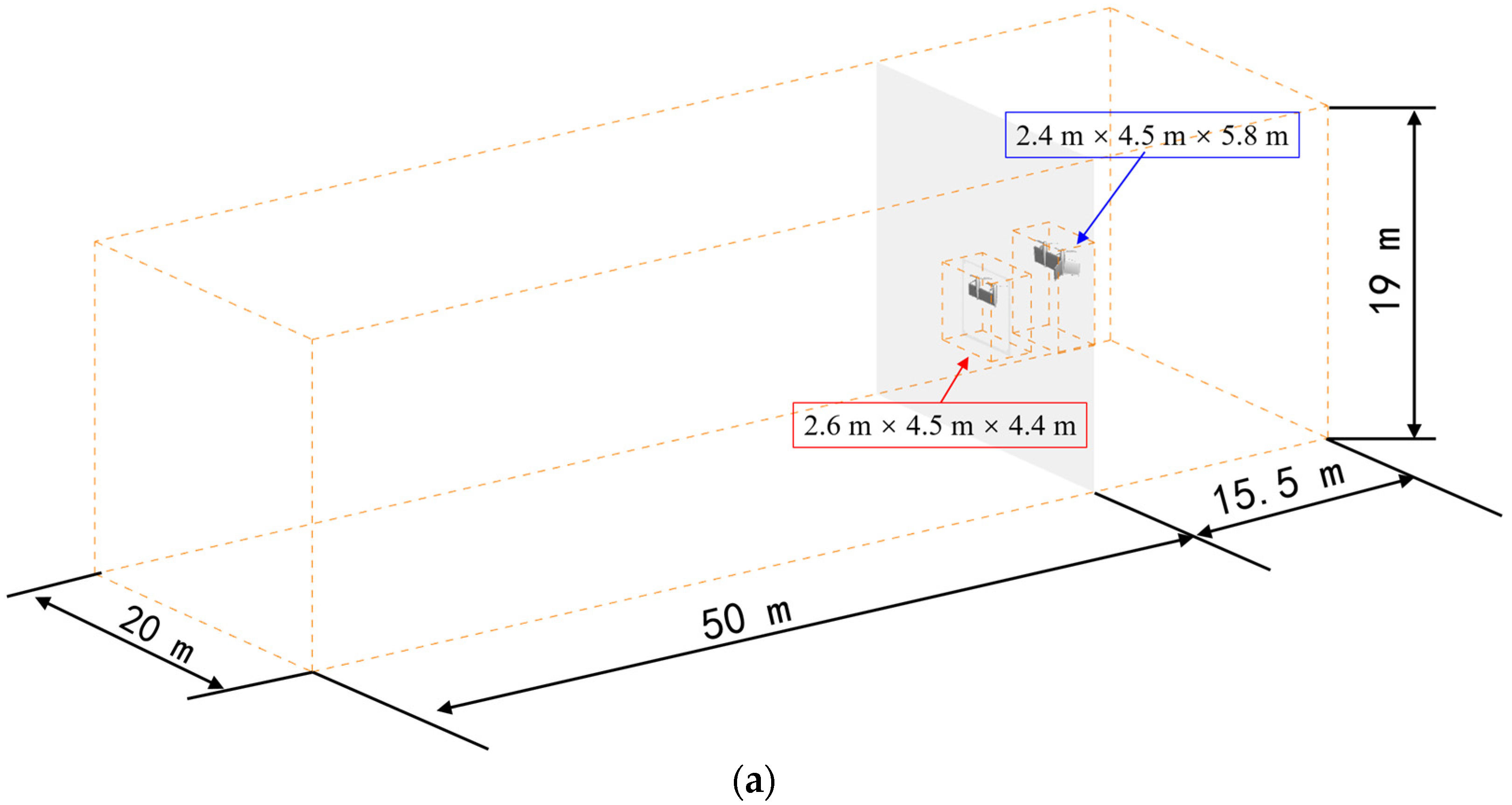

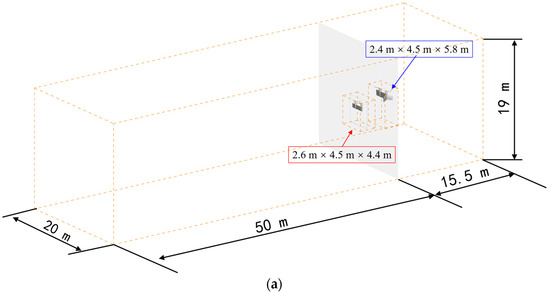

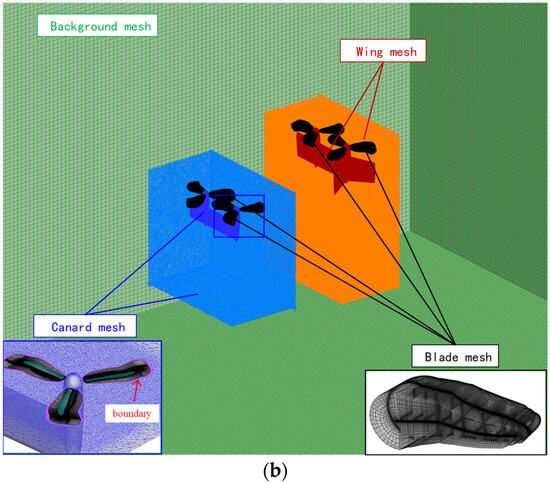

The multi-layer overset mesh system constructed for the DMT aircraft in this paper is shown in Figure 5. Figure 5a illustrates the size of the computational domain and the initial position of the tandem tilt-wing. Given that the tilt-wings move forward during the tilt transition, the longitudinal length of the computational domain is set to be relatively large. Details of the initial mesh are presented in Figure 5b. It can be seen from the figure that the propeller blade meshes are overset in the corresponding canard and wing meshes, which are further overset in the outer background mesh. All overset blocks can be set with unsteady motion to achieve the simulation of the full-aircraft dynamic tilt transition state. To ensure computational accuracy, mesh refinement is performed at the overset boundaries of the canard and wing, as well as in the propeller wake development regions. The total number of mesh cells is approximately 37 million.

Figure 5.

Body-fitted mesh of tandem multi-propeller and tilt-wing (initial computational state). (a) Computational domain and tilt-wings position; (b) Initial computational mesh details.

2.3. Flow Field Solver

To accurately simulate an unsteady flow field and investigate the interference mechanisms between components, this study employs the in-house Rotorcraft Aerodynamics and Aeroacoustics Solver (RADAS) [30] for numerical simulation. Our research group has extensively applied this solver to the aerodynamic characteristic calculation of coaxial rigid rotors [31] and the unsteady flow field simulation of rotor blades during tiltrotor aircraft transition flight [32].

The governing equations of the flow field adopt the three-dimensional unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes equations in the inertial coordinate system:

where V and S denote the volume and surface area of the control volume, respectively; n is the unit vector of the outward normal to the cell surface; W denotes the vector of conserved variables; Fc denotes the vector of convective fluxes; and Fv denotes the vector of viscous fluxes, as follows:

where ρ, p, E, and H, respectively, represent the density, pressure, total energy per unit volume and total enthalpy per unit volume; q = [u, v, w] and qω = [uω, vω, wω] denote the absolute velocity and relative motion velocity of the cell; i, j, k are the unit vectors in the x, y, and z directions of the coordinate system; τij (where i, j = x, y, z) is the viscous stresses tensor; and Θx, Θy, Θz denotes the work of the viscous force and heat conduction on the fluid. Based on Stokes’ hypothesis for the bulk viscosity coefficient, τij, Θx, Θy, and Θz can be explicitly expressed as follows [33]:

where T is the temperature, and μ and K represent the fluid viscosity and thermal conductivity, respectively, which can be derived from the turbulence model. This physical model is a compressible model, which is suitable for the numerical simulation of aircraft operating under high Mach and Reynolds number conditions.

The S-A turbulence model [34] was employed to account for turbulent flow effects. This model required us to solve only one additional transport equation to capture the effects of viscosity and wake vortices, representing a favorable trade-off between computational accuracy and efficiency. Moreover, the S-A turbulence model has been widely validated and applied to the flow field simulation of tiltrotor aircraft during their transition flight states [17,35], confirming its suitability for unsteady rotor–wing interference problems. The ROE-MUSCL spatial discretization scheme was adopted to obtain a high shock resolution, and the implicit LU-SGS temporal discretization [36] was used to accelerate the convergence step. The boundaries of the computational domain (background domain) in this study adopt the pressure-far-field boundary conditions for subsonic flow, with non-reflecting conditions considered to ensure the physical authenticity of the flow field. The propeller blades and wings were assigned no-slip wall boundary conditions, enforcing zero relative velocity between the fluid and solid surfaces. All simulations were conducted under standard atmospheric pressure and sea-level environment, with no change in altitude during the simulation.

For the simulation of rotating components, the solver implements the handling of moving overset meshes based on the Arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian (ALE) equations [37]. The conservation equations with body forces neglected are given as follows:

where U denotes the mesh surface velocity. In this manner, the additional flux generated by the conservative variables during motion is calculated.

2.4. CPU-GPU Coordinated Acceleration Technology

In unsteady simulations of the dynamic tilting process of the DMT aircraft using the overset mesh method, ensuring computational accuracy requires 180 time steps for one propeller rotation, with each time step containing 20 pseudo-time steps. This results in a large number of total iterations for the entire tilting process. Additionally, the overset mesh system contains over 37 million mesh cells, leading to substantial computational resource consumption. Therefore, this study develops a CPU-GPU coordinated heterogeneous acceleration technology to enhance CFD computational efficiency.

Parallel acceleration strategies on CPUs typically involve task parallelism, where independent, large-scale task loads are distributed across different threads for parallel computation to improve speed. Key methods include work task allocation, parallel algorithms based on Open Multi-Processing (OpenMP) [38], and parallel communication via MPI.

- The work task allocation parallel method involves creating distinct task loads for various work tasks and distributing them to different threads for parallel processing. In this study, independent tasks within the three CFD solving processes—mesh motion assembly, numerical flow field solving, and result post-processing—are parallelized using work task allocation.

- OpenMP is a multi-threaded programming model based on shared memory architectures. The core principle underlying parallelization via OpenMP lies in the parallelization of individual loop computations within the process. In the CFD solver program of this study, the multi-loop structure in the flux calculation part of the flow field solving process is processed in parallel using OpenMP.

- MPI is a communication protocol standard for parallel computing. Using MPI-based communication methods, meshes can be partitioned for parallel acceleration. By distributing the number of mesh volume cells, the task load across each computing node is balanced as much as possible. Independent point-to-point communication is adopted for information transmission, which does not rely on forwarding via a central node, thus improving communication efficiency.

While CPU parallelization has enhanced the computational speed of CFD numerical simulations, its acceleration effect is constrained by inter-core communication processes, which still fail to meet the computational efficiency requirements for simulating the dynamic transition of the DMT aircraft in this study. GPUs adopt a data-parallel model based on a single-instruction-multiple-thread architecture (fine-grained thread-level parallelism), which can decompose a single task into tens of thousands of threads, significantly enhancing the acceleration effect [39]. Therefore, this study further develops a CPU-GPU coordinated heterogeneous parallel acceleration technology. The solver consists of C language code for the CPU host port and CUDA C code [40] for the GPU device port, where the CPU is responsible for logical control and the GPU handles data-parallel tasks. Cooperative computing is achieved through mutual information transmission between CPU memory and GPU memory.

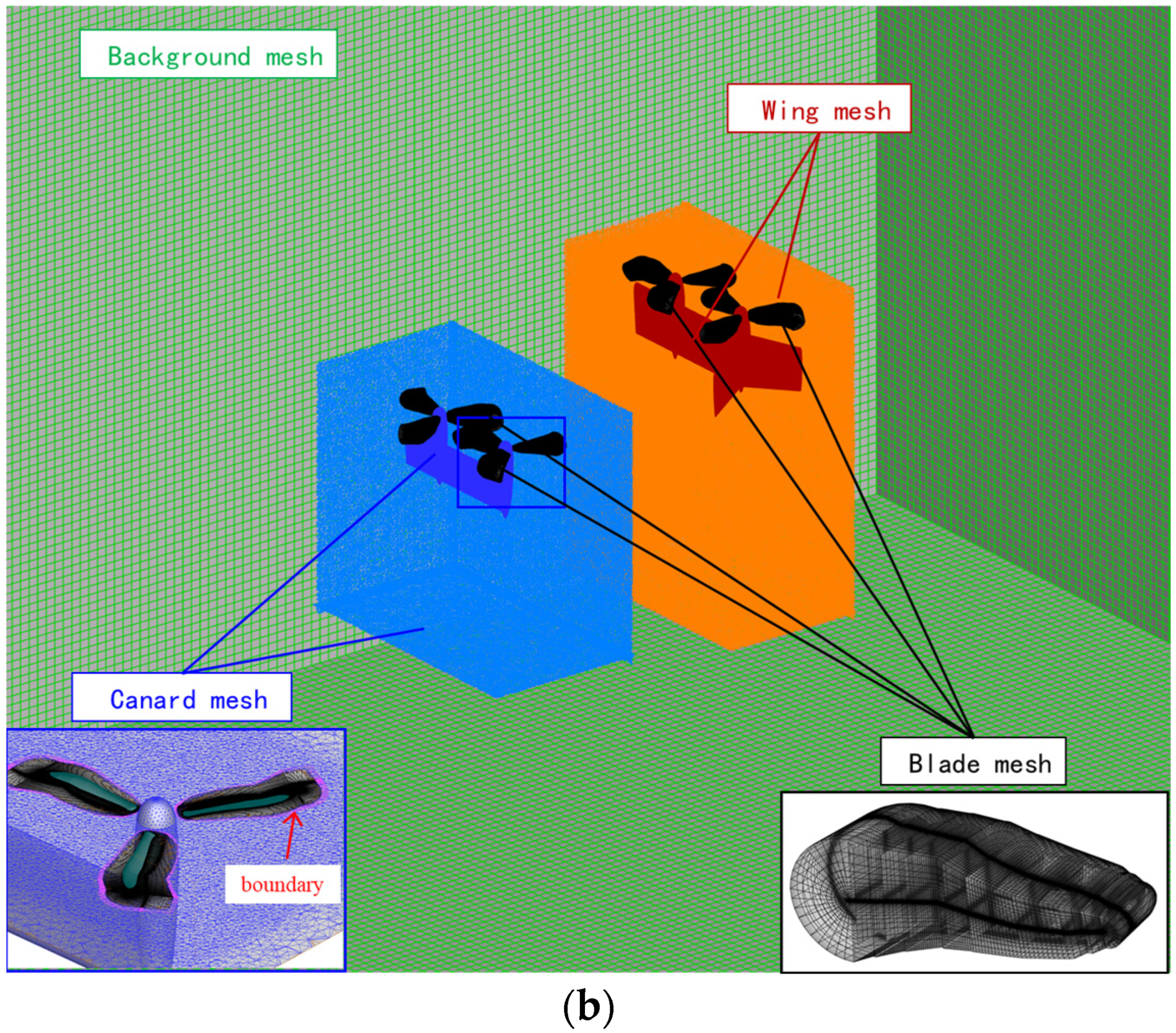

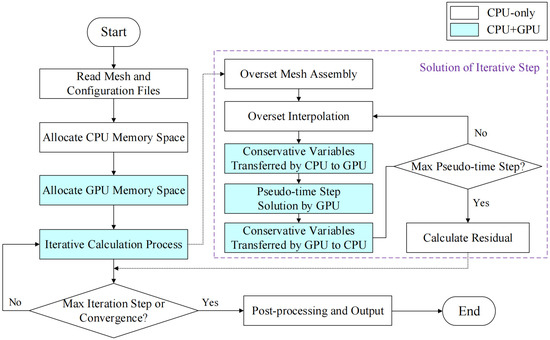

Considering that the core algorithm of overset mesh assembly relies on logical judgment and branch prediction, which yields poor performance when directly ported to the GPU, this study executes mesh motion and overset assembly on the CPU, while flow field simulations at given motion positions are computed on the GPU. Figure 6 presents the CPU-GPU coordinated acceleration framework of the self-compiled solver in this study. The computational processes involving GPU participation are marked with a blue background in the figure, while those without a background color are executed by the CPU. Specifically, the GPU is primarily used for numerical flow field solving in each iteration step, including the calculation of conservative variables, gradient solving, flux calculation, and time discretization of pseudo-iteration steps; in contrast, mesh assembly, interpolation processes, and logical judgments are executed on the CPU.

Figure 6.

CPU-GPU coordinated acceleration framework.

Based on the body-fitted CFD computational mesh of the DMT aircraft established in this study, the computational times with and without GPU parallel acceleration were compared. The computing hardware consists of an AMD EPYC 9554 64-Core Processor (CPU) (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 D (GPU) (Santa Clara, CA, USA). According to the number of overset mesh blocks and the memory limit of a single GPU, the full-aircraft computational mesh was distributed across 4 GPUs for parallel computing. In the same computational case, 50 time-step iterations were performed using CPU-only computing and CPU-GPU coordinated acceleration computing, respectively. The results are presented in Table 3. It can be observed that the CPU-only computing consumes enormous amounts of time, making it difficult to implement numerical simulations of the full transition state. In contrast, the coordinated acceleration method using multiple GPUs requires significantly less runtime, achieving a speedup ratio of 14.37. This verifies that the parallel acceleration method can substantially reduce the computational time.

Table 3.

Comparison of computational time between CPU and CPU-GPU coordinated acceleration.

2.5. Simulation Validation

Based on the numerical simulation methodology established in the preceding subsections, the in-house RADAS coupled with CPU-GPU acceleration technology was employed to conduct case validations for propeller–wing interference under both hovering and forward flight conditions, thereby verifying the effectiveness of the proposed computational approach.

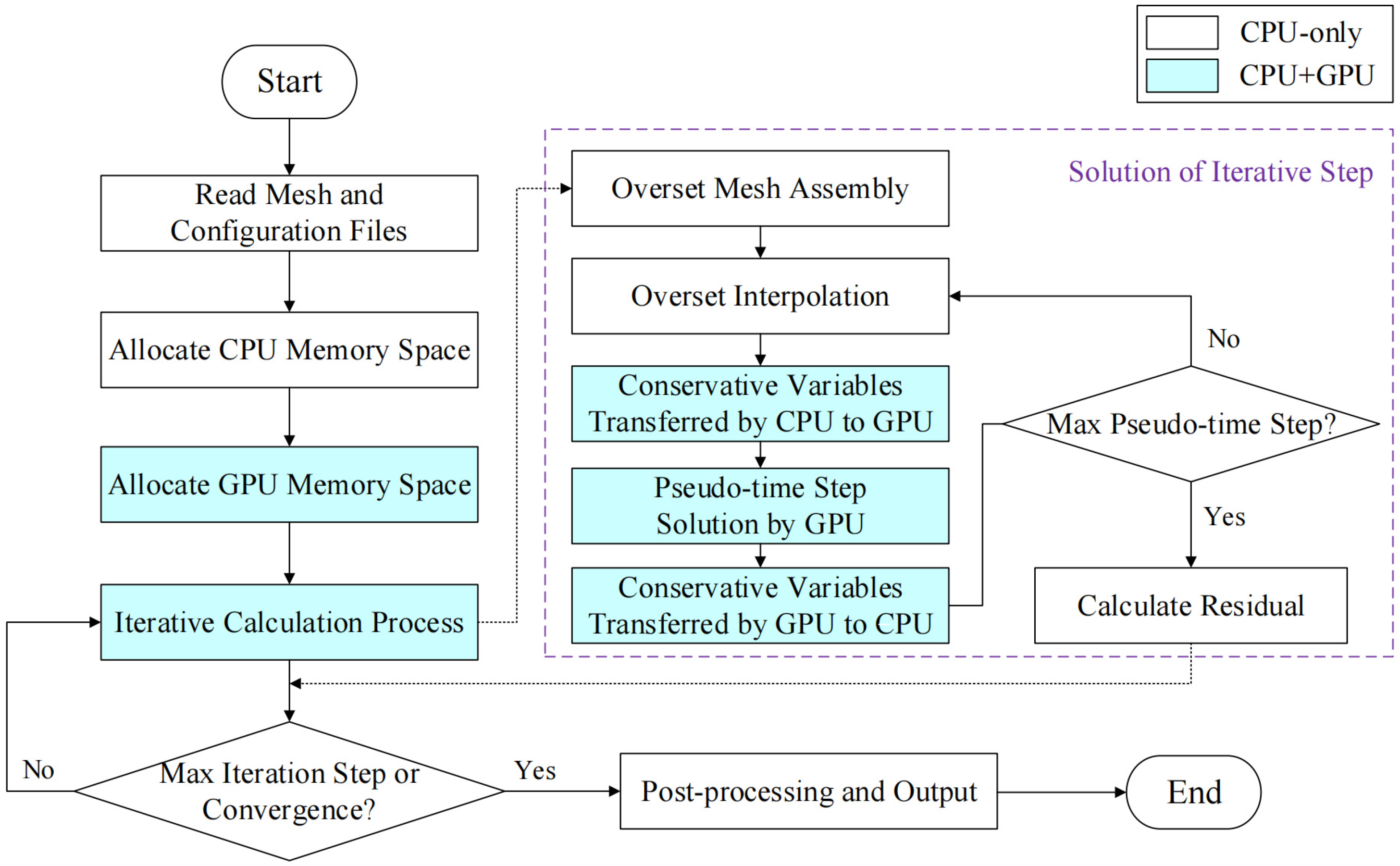

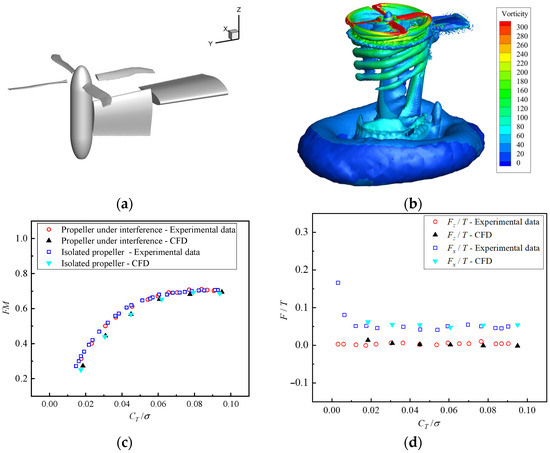

Firstly, computational and experimental validations were conducted for the optimized propellers of the DMT aircraft. The experimental model for propeller–tilt-wing interference [41] is shown in Figure 7a. This model consists of two wing segments: an inner fixed segment and an outer tiltable segment, which is placed vertically during the experiment. The overset mesh CFD method established in this study is employed to calculate the aerodynamic performance of the isolated propeller and the propeller-tilt-wing interference system in hover, respectively. Figure 7b presents the Q-criterion vorticity contour plot (with Q = 50) obtained from numerical simulations under the interference flow condition. The computational results are compared with the experimental data, as presented in Figure 7c,d. FM denotes the propeller figure of merit, and σ represents the propeller solidity. In hover, the wing aerodynamic forces are induced by the downwash interference of the propeller, including the axial force Fx and vertical force Fz. It can be observed from the figures that the computational results agree well with the experimental data, both in the isolated propeller state and the propeller–wing interference state. According to the specific data, the difference in the propeller figure of merit between the isolated state and the interference state is minimal, indicating that the wing has little impact on the propeller for this configuration. The wing generates a certain axial force under propeller interference, while the vertical force is very small, demonstrating that the wing of this configuration is subjected to minimal vertical loads from the propeller and the propeller-wing interference is weak.

Figure 7.

Validation of the propeller–tilt-wing interference example. (a) Experimental model; (b) Vorticity contours (CT/σ = 0.095, Q = 50); (c) Propeller FM; (d) Wing loads.

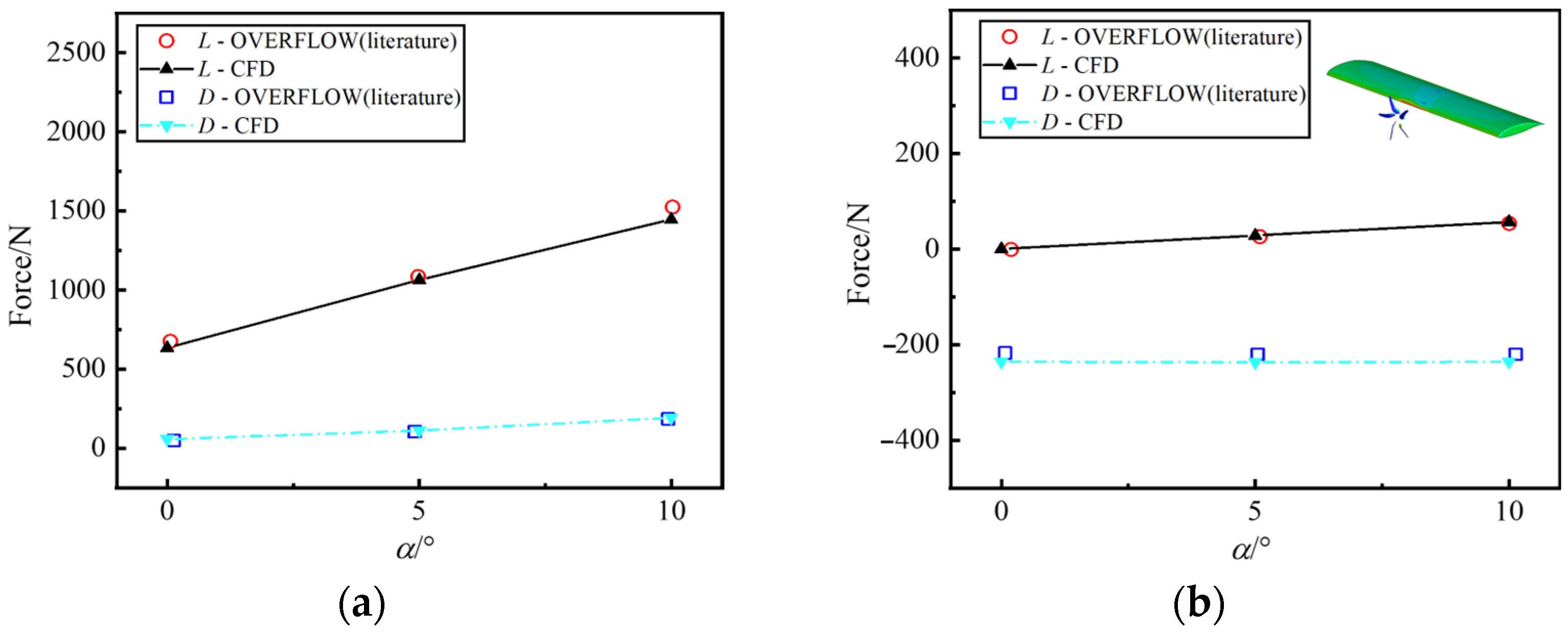

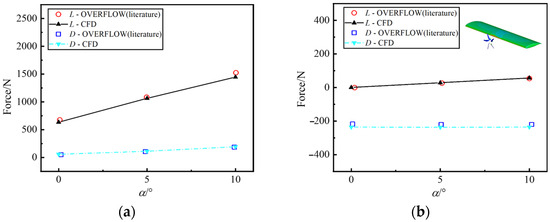

Then, for validating the unsteady flow field of axial-flow propeller-wing interference in forward flight, the X-57 propeller-wing interference case [42] is selected, with the propeller mounted at the mid-span of the wing. The CFD method established in this study is used to calculate the propeller-wing interference flow field at different angles of attack. The calculated lift L and drag D of the propeller and wing are compared with the data from the literature [43], as shown in Figure 8. It can be observed from the figure that the calculated L and D of the propeller and wing using the proposed method agree well with the literature data, verifying the accurate prediction of the aerodynamic characteristics under propeller-wing interference. Additionally, the results indicate that as the angle of attack increases, the propeller lift increases slightly while the drag changes minimally. In contrast, both the lift and drag of the wing increase, with the lift showing a significant increment. This demonstrates that the wing is the primary lift-generating component in forward flight. Meanwhile, the propeller thrust mainly serves to balance the drag.

Figure 8.

Validation of the X-57 propeller-wing interference example. (a) Propeller loads; (b) Wing loads.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Aerodynamic Characteristics of Multi-Propeller/Tilt-Wing During Dynamic Transition

The established numerical flow field simulation method is used to conduct unsteady numerical simulations of the full dynamic transition process of the tandem tilt-wing with parallel propellers from hover to cruise flight. The specific flight and control parameters of the different tilt speeds have been provided in Section 2.1. The computational resources employed in this study are consistent with the CPU-GPU heterogeneous acceleration configuration described in Section 2.4, utilizing one AMD EPYC 9554 64-Core Processor (CPU) and four NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 D (GPUs) for collaborative computing. For the full transition process simulation, the total computational time under the slow tilting condition is 196.6 h, while that for fast tilting is 105.9 h.

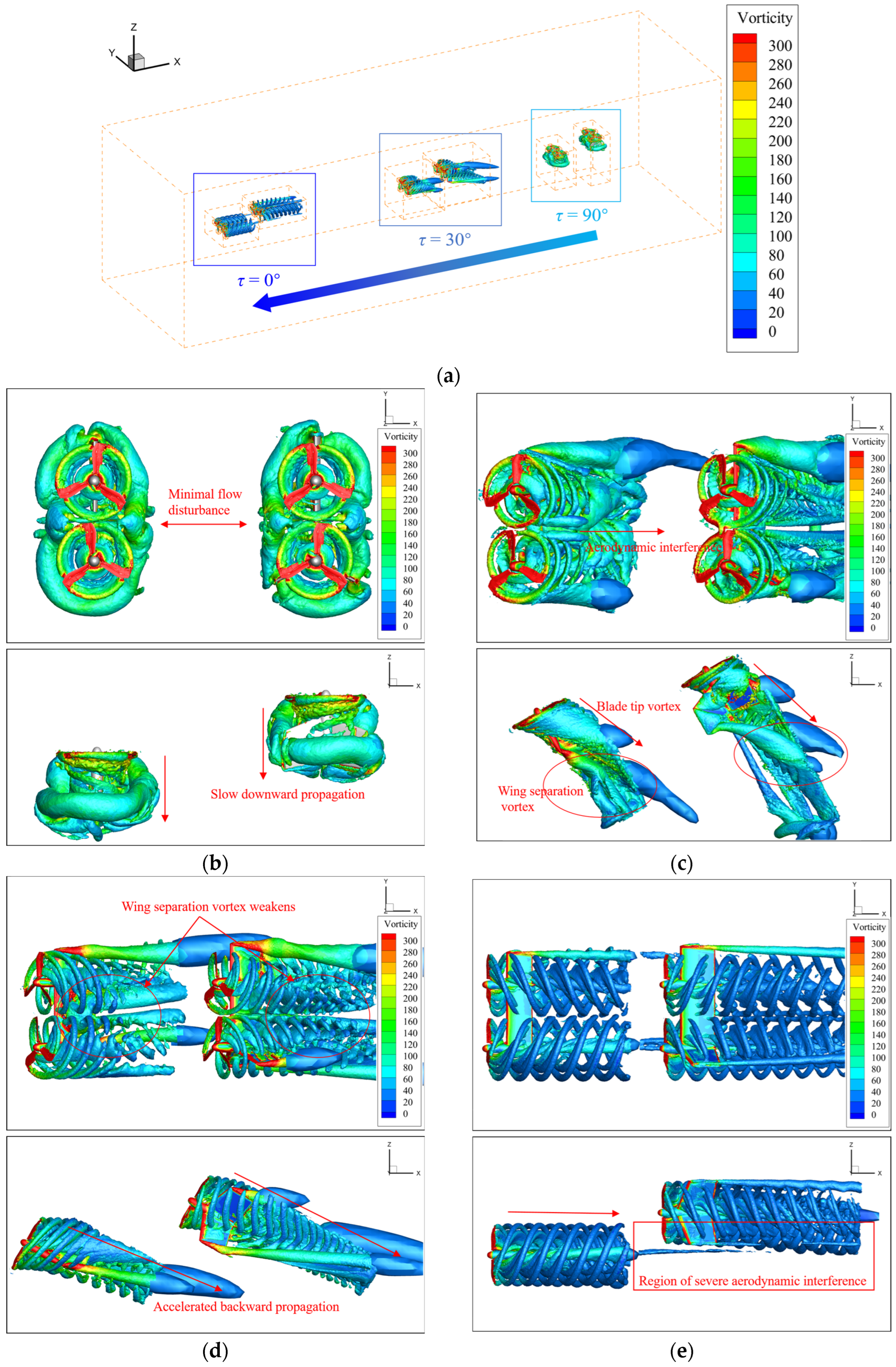

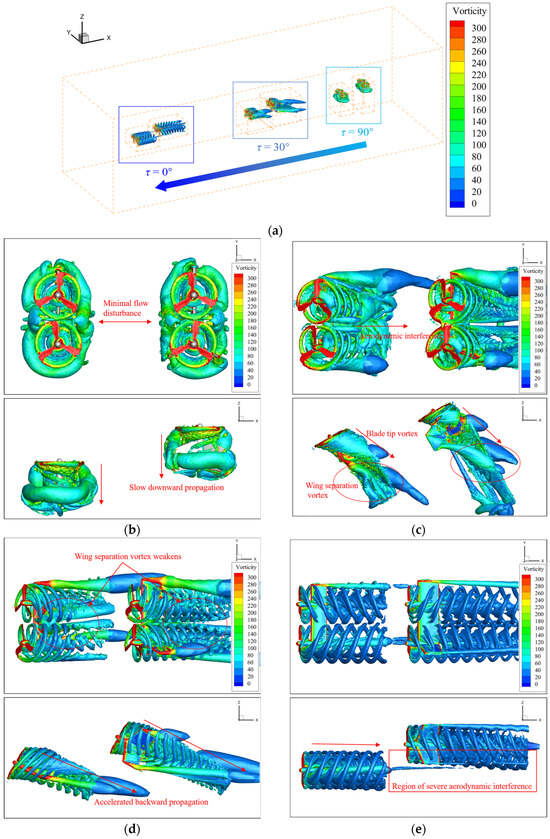

The vorticity contours of the flow field calculated during the slow dynamic tilt transition are shown in Figure 9. As the tilting proceeds, the cruise speed and propeller collective pitch gradually increase. Specifically, Figure 9b–e present detailed Q-criterion vorticity plots at different tilt angles, which characterize the flow evolution features throughout the tilt process. It can be observed from the figures that, at large tilt angles, the propeller wake exhibits sluggish development, and the aerodynamic interference between the fore and aft propellers and the tilt-wing is negligible. However, the high angle of attack induced by the large tilt angles generates substantial separation vortices on the tilt-wing, resulting in degraded aerodynamic performance by the tilt-wing. As the tilt angle decreases, the tilt-wing separation vortices attenuate, the aerodynamic performance of the tilt-wing recovers, and the interference of the wake from the front propeller on the rear tilting wing intensifies. This amplifies the influence of the wake from the front propellers and canard on the rear propellers and wing. The proposed numerical method can accurately simulate the component motion and flow field characteristics during the full dynamic tilting process, providing an effective tool for the analysis of the aerodynamic characteristics of the multi-propeller and tilt-wings, as well as research on flow field evolution.

Figure 9.

Vorticity contours of flow field during slow dynamic tilting transition. (a) Entire tilt transition process; (b) τ = 90°, Q = 500; (c) τ = 60°, Q = 200; (d) τ = 30°, Q = 200; (e) Tilting angle τ = 0°, Q = 100.

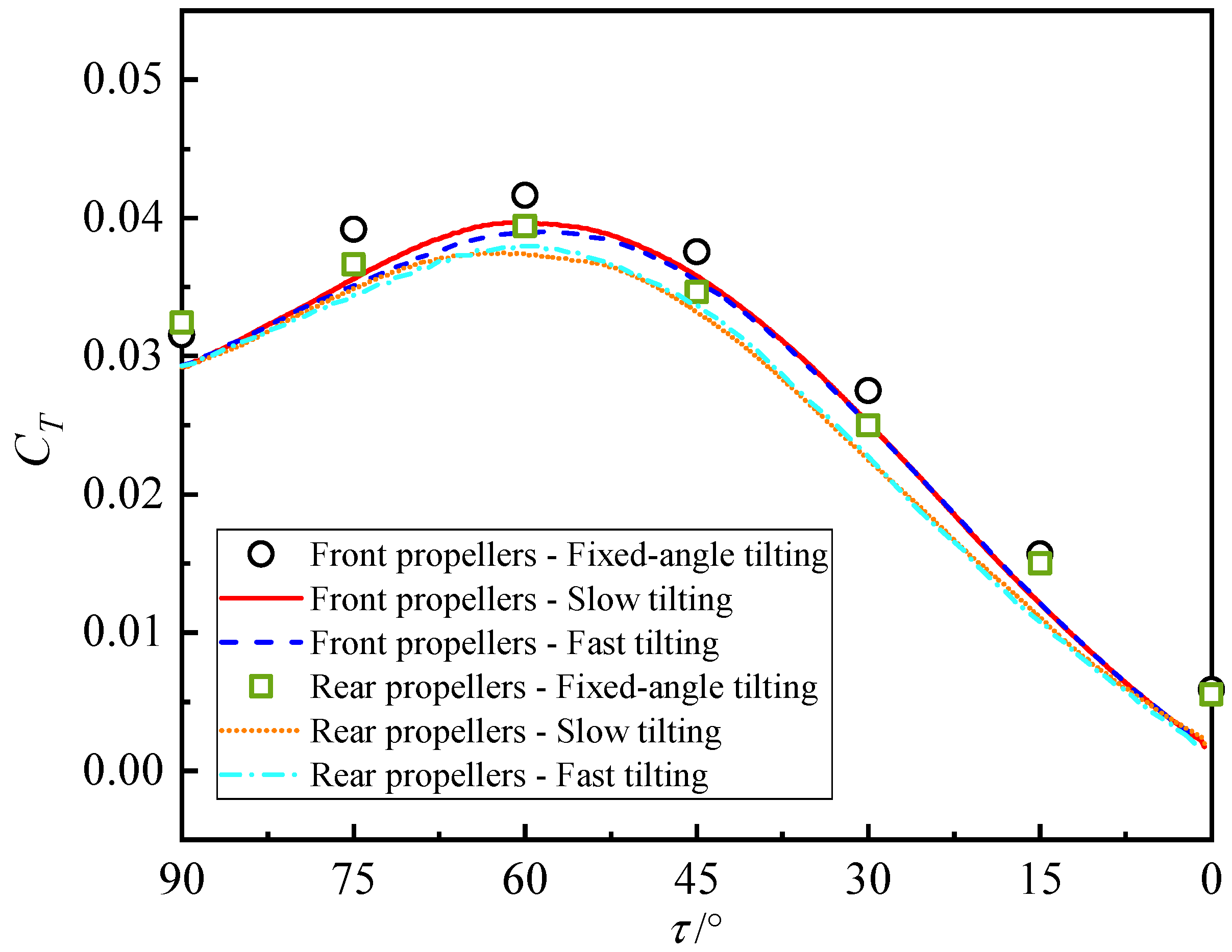

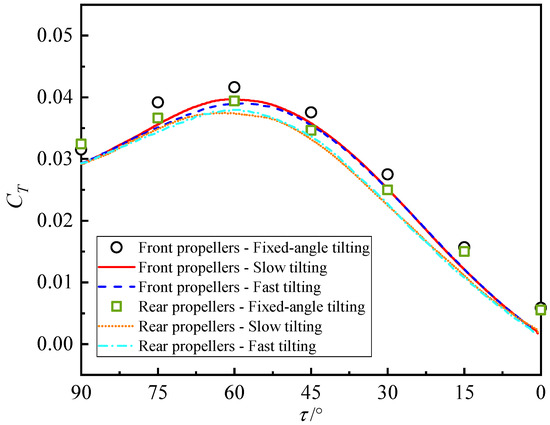

First, a detailed comparison is conducted on the aerodynamic performance variations in the front and rear parallel propellers, canard, and wing at different tilting speeds during the dynamic tilting transition. The average CT variation curves of the parallel propellers mounted on the canard and wing under different tilting speeds are shown in Figure 10 and compared with the calculated values of fixed-angle tilting. It can be observed from the figure that as the tilting transition proceeds, the propeller CT exhibits a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, eventually reducing to a relatively small value. The difference in propeller thrust between the initial state and cruise flight stems from the distinct roles of the propeller in different flight conditions. In hover, the aircraft’s lift is entirely provided by the propellers, whereas during cruise flight, the propeller thrust is mainly used to balance the drag, and its magnitude is much smaller than the aircraft’s weight.

Figure 10.

Average CT of parallel propellers during dynamic tilting transition.

A comparison of the parallel propellers on the canard and wing reveals consistent CT variation trends from Figure 10. However, in terms of numerical magnitude, the CT of the propellers on the main wing is slightly lower than that of the propellers on the canard, which reflects the aerodynamic interference induced by the forward tilting wing. Furthermore, during dynamic tilting, the CT of the parallel propellers on both the canard and wing is smaller than that under fixed-angle tilting conditions, with a more significant reduction in CT at higher tilting speeds. The superposition of the tilting speed increases the inflow velocity of the propeller disk.

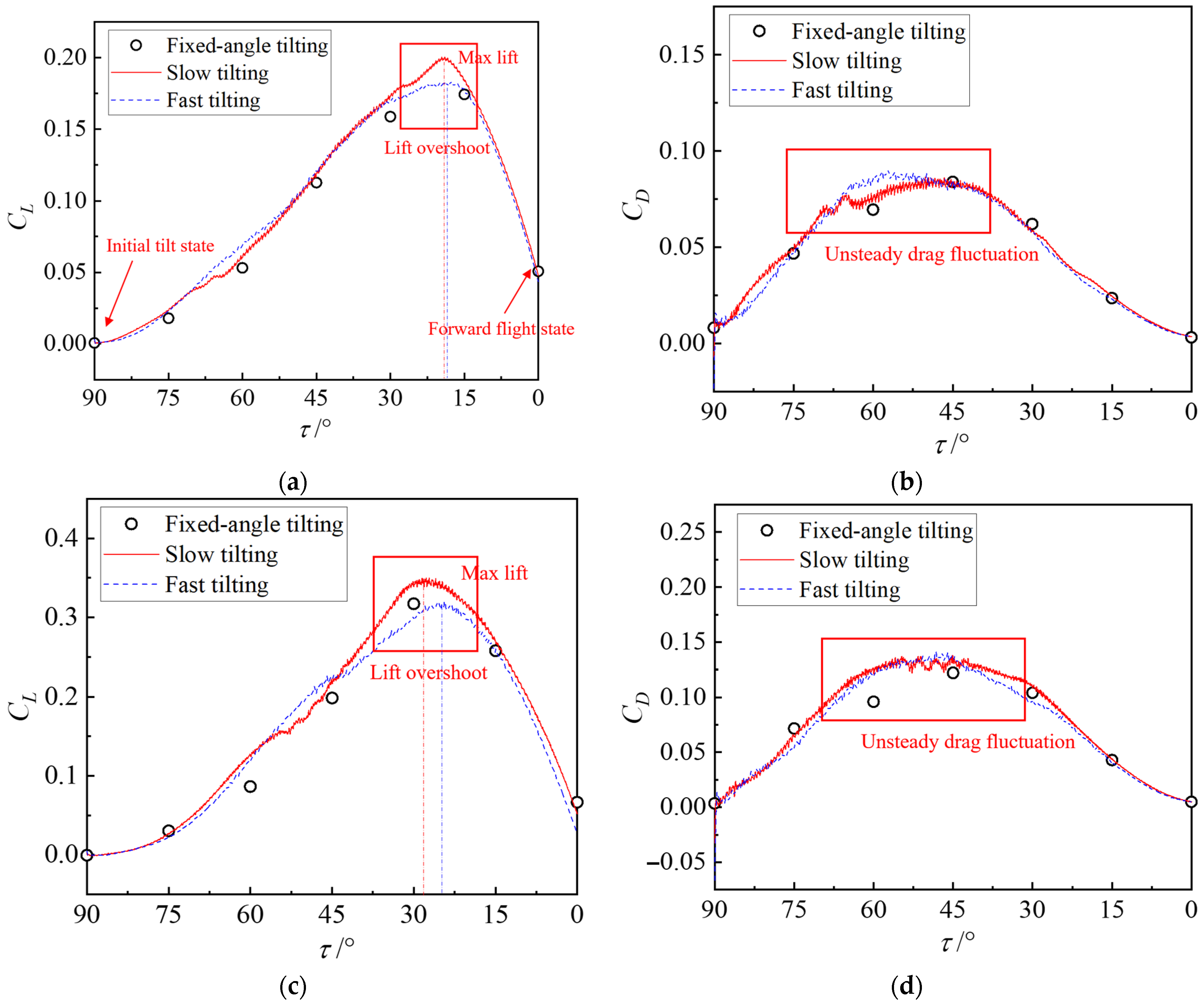

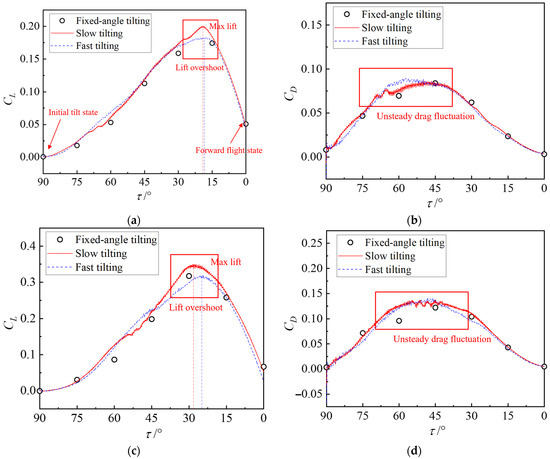

The variation curves of the lift and drag coefficients of the canard and wing under different tilting speeds are presented in Figure 11. It can be observed that during the tilting process, the CL and drag coefficient (CD) of the canard and wing undergo a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. The initial state of the tilting process is hovering, wherein the tilt-wings’ forces are induced by the interference of the parallel propellers, and the vertical load is very small. Although the CD exhibits the same variation trend as CL, the positions of its extreme points differ. In the hovering state, propeller interference generates a certain axial force. The CD undergoes significant unsteady fluctuations near its maximum value, which indicates severe flow separation at this operating condition.

Figure 11.

Aerodynamic characteristics of tilt-wings during dynamic tilting transition. (a) Canard CL; (b) Canard CD; (c) Wing CL; (d) Wing CD.

The tilting speed has a significant impact on the wing lift and drag coefficients, and the impact varies across different wings and tilting angles. From Figure 11a, the CL of slow tilting is greater than that of fast tilting for the canard at most tilting angles. In contrast, at low flow separation and high incoming flow speed, the high tilting speed instead reduces the aerodynamic force. To further contrast, Figure 11c illustrates that the tilting angle corresponding to the maximum lift and the position of the most severe flow separation in the wing differ from those of the canard due to the interference of the front propellers and canard. This results in different tilting angle ranges where the lift of slow tilting is smaller than that of fast tilting. Notably, the tilting angles corresponding to the maximum CL of the wing during slow and fast tilting are different. This is because fast tilting has a significant impact on the incoming flow speed and direction; coupled with the interference of the front propellers and canard, the reduction in CL caused by the decrease in the actual angle of attack is smaller than the increase induced by the rise in incoming flow speed.

Figure 11b,d show that the CD of tilt-wings during slow tilting is also greater than that during fast tilting at most tilting angles, with the opposite trend only occurring in regions where the CD fluctuates significantly. In those regions, the tilt-wings are in a state of severe flow separation, and the tilting speed exhibits a flow straightening effect.

3.2. Influence of Dynamic Tilting Speed on Flow Field Evolution

Building on the analysis of the aerodynamic characteristics of propellers and tilt-wings during the transition process, this section elaborates on the flow field distributions and aerodynamic performance of the parallel propellers, canard, and wing under different tilting speeds. The primary objective of this analysis is to investigate the influence of dynamic tilting speed on flow field evolution. The tilt angle directly determines the contribution ratio of tilt-wing lift and propeller thrust to the total lift of the aircraft. Previous studies on the transition state of tiltrotor aircraft have conducted flow simulations at a fixed tilt angle of 30° [16], where the wing contributes a substantial portion of the total lift. However, as the tilt angle increases, tilt-wing stall is initiated, and the propellers gradually become the primary providers of lift. Meanwhile, existing research has shown that at a tilt angle of 75°, the rear propellers experience minimal aerodynamic interference from the front propellers [17]. Therefore, this study selects the flow fields at instantaneous tilt angles of 60° and 30° for in-depth analysis. This selection not only covers the aerodynamic phenomena dominated by two distinct components (tilting wings and propellers) but also includes scenarios with significant inter-component aerodynamic interactions [36], ensuring comprehensive coverage of key transition-phase flow characteristics.

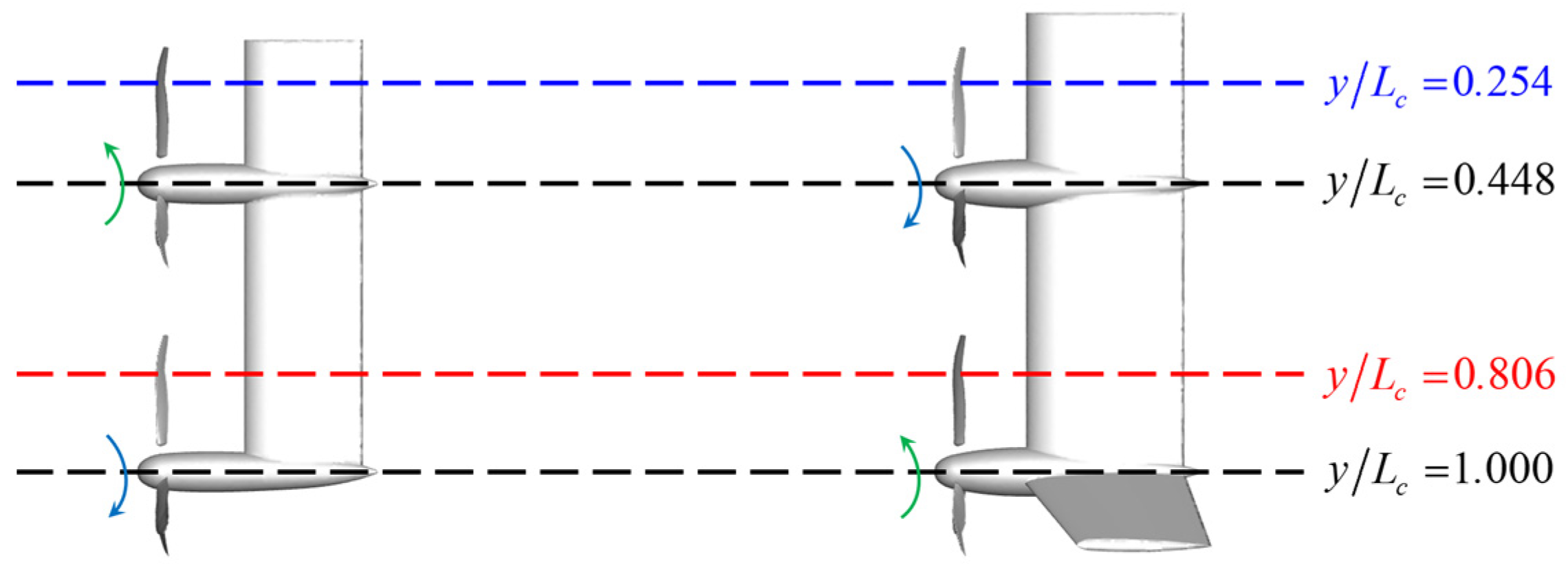

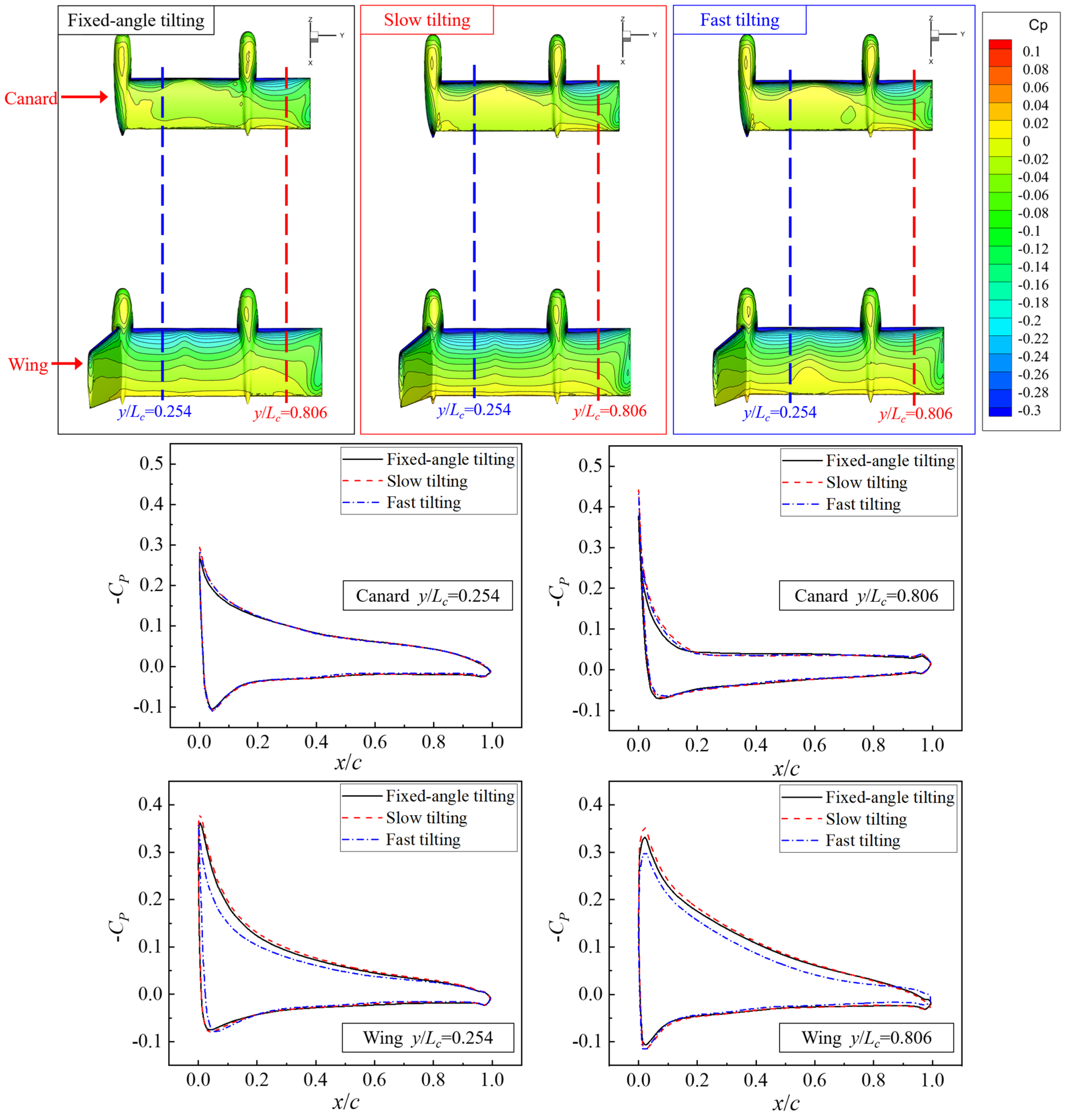

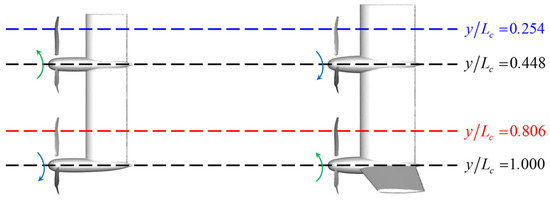

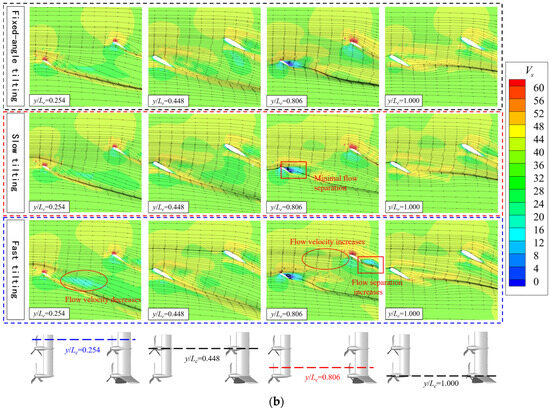

Different rotation directions of parallel propellers, radial load differences on the propeller disk, and varying wake velocities at different positions result in distinct interference effects on different spanwise positions of the wings. Four characteristic tilt-wing sections were selected as the research objects, as shown in Figure 12. Due to the different rotation directions of the propellers, the interference effects on the sections are opposite. By analyzing the vorticity and velocity distributions of the four sections and conducting a detailed comparison of the pressure coefficient distributions of the wing sections behind the propellers, the detailed variations in propeller–wing interference during the dynamic tilting transition state are explored.

Figure 12.

Four characteristic tilt-wing sections.

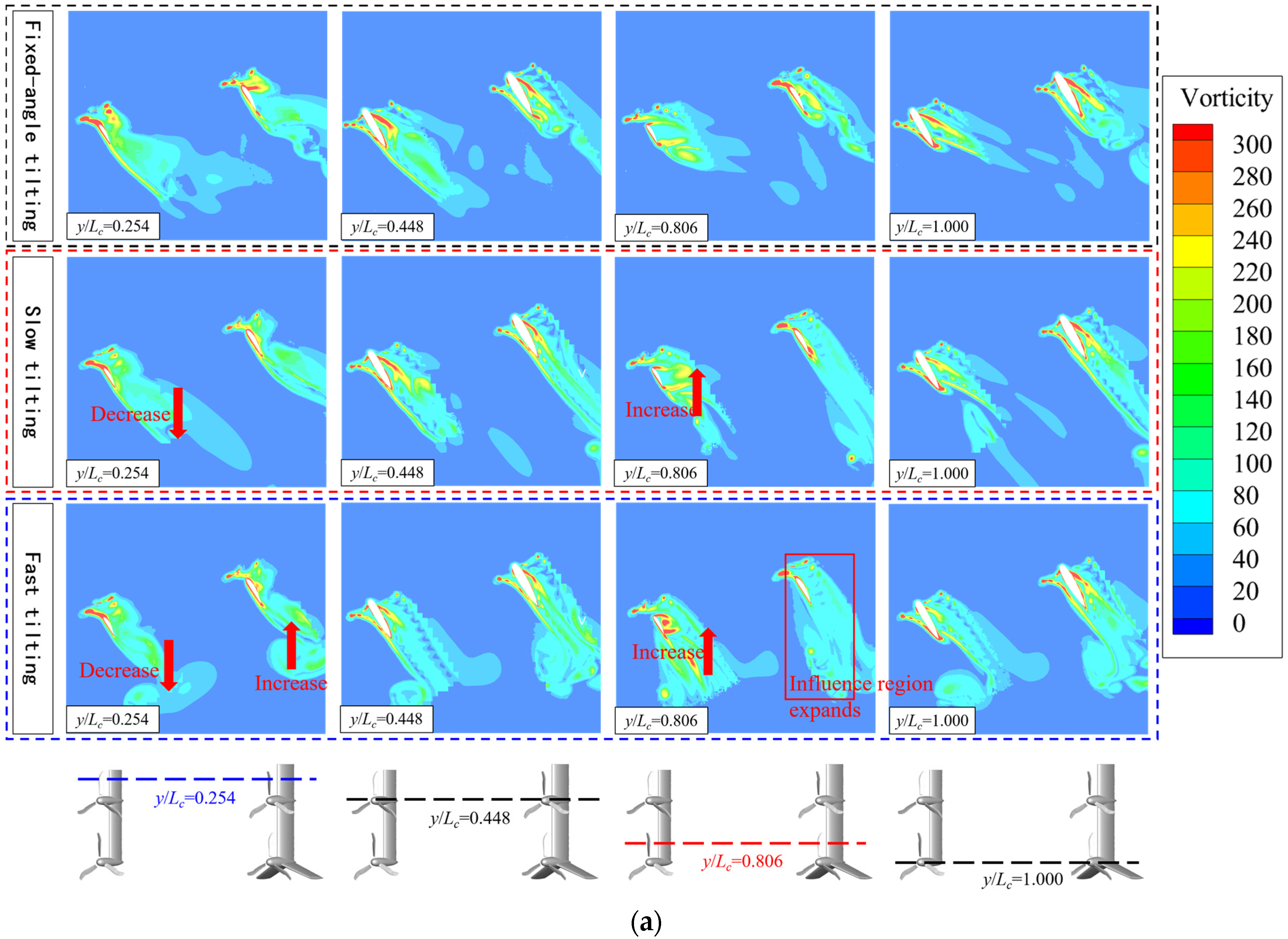

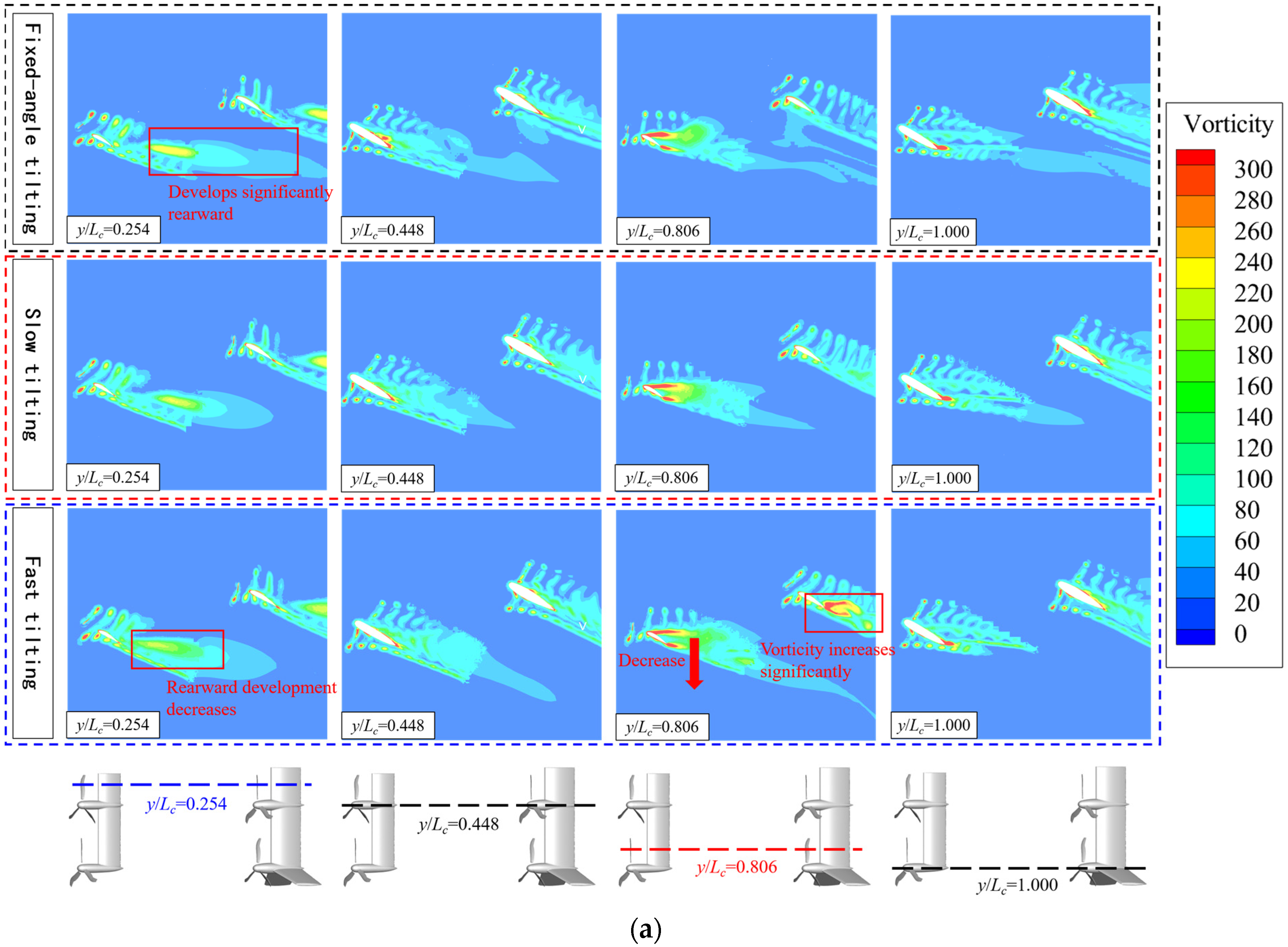

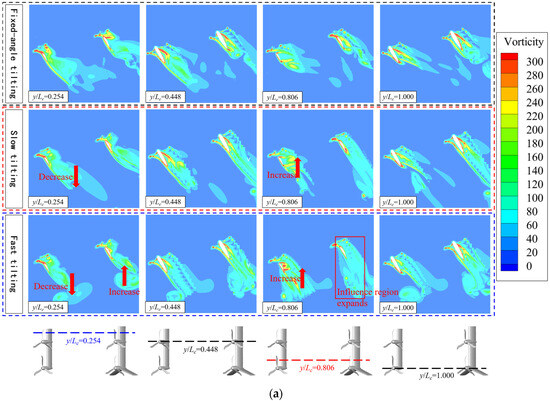

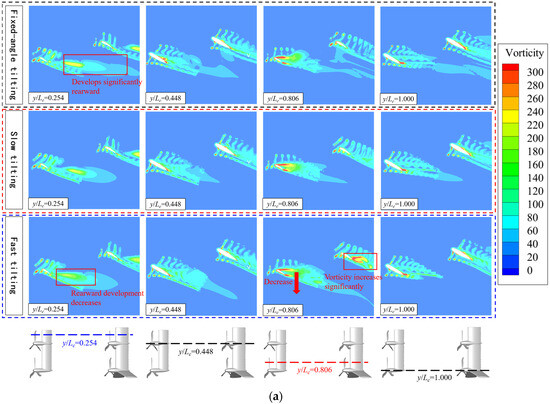

Figure 13 presents the flow field distribution diagrams of the tilt-wing’s characteristic sections at a 60° tilting angle under different tilting speeds. From the comparison of vorticity contours in Figure 13a, it can be observed that on each nacelle section, the higher the tilting speed, the more the propeller wake vortices develop below the wing, with a wider influence range. As the tilting speed increases, the vorticity of the canard y/Lc = 0.254 sections decreases, reducing the favorable propeller–wing interference. In contrast, the vorticity of the y/Lc = 0.806 sections increases, enhancing the impact of the propeller wake on the canard, indicating that the tilting speed exerts opposite effects on the aerodynamic performance of the canard behind propellers with different rotation directions. However, the vorticity of the wing sections shows distinct variations: being affected by the front multi-propellers and wings, the chordwise development area of the propeller vorticity on the wing expands as the tilting speed increases.

Figure 13.

Flow field distribution diagrams of tilt-wing’s characteristic sections at 60° tilting angle with different tilting speeds. (a) Vorticity Contours. (b) Velocity Streamlines.

A comparison of the velocity distributions and streamlines of the nacelle sections in Figure 13b reveals that an increase in tilting speed intensifies the downward deflection of the streamlines behind the nacelles and reduces the flow velocity along the incoming flow direction. The high-velocity regions near the leading edges of the canard and wing also diminish. For the y/Lc = 0.254 sections of the canard, the front propellers rotate from the upper to the lower surface of the canard, resulting in a small effective angle of attack of the sections under propeller interference. The tilting speed deflects the streamlines at the canard’s trailing edge toward the horizontal direction, increasing flow separation. In contrast, the propellers ahead of the y/Lc = 0.806 sections rotate in the opposite direction, increasing the effective angle of attack of the sections and leading to severe flow separation. At this point, the tilting speed weakens the vortices at the wing trailing edge, and the peak value of the low-velocity region increases and approaches the wing surface, reducing flow separation. It can be clearly observed from the streamlines that the wake of the front propellers and wings interferes with the rear wing. Flow separation occurs on both sections of the wing under fixed-angle conditions, while the tilting speed mitigates this flow separation.

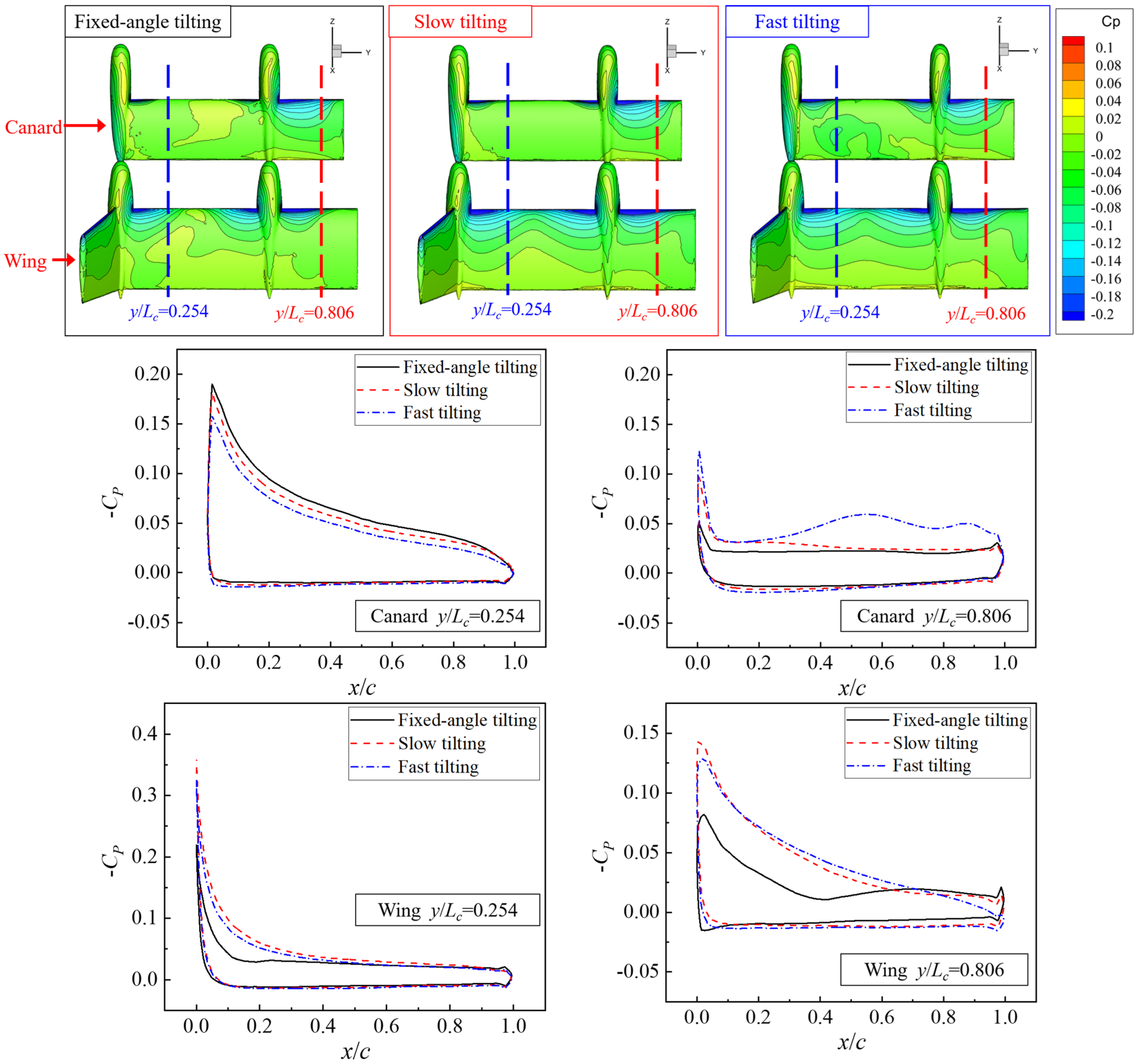

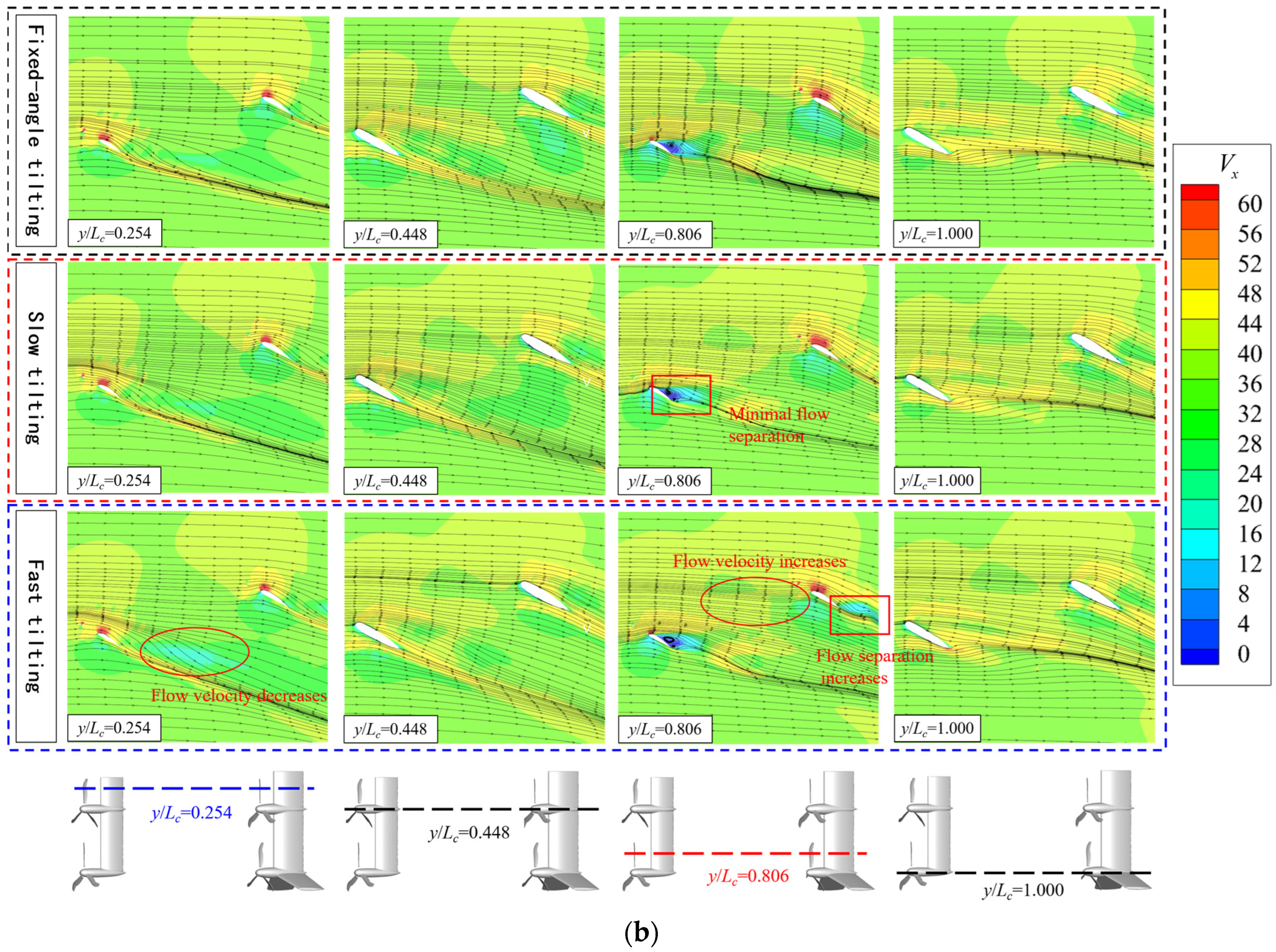

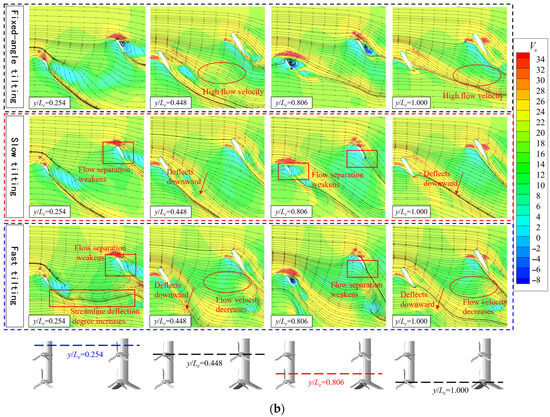

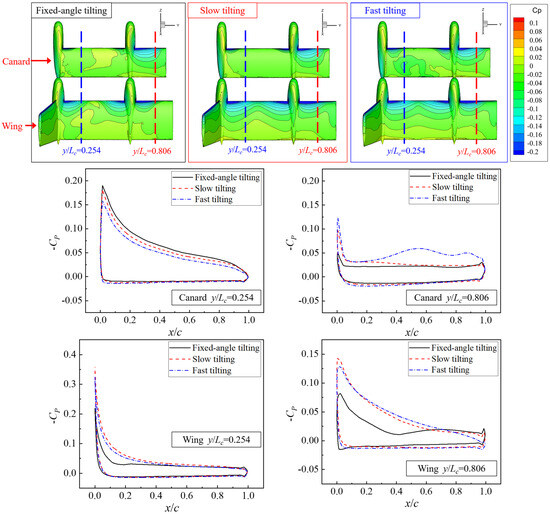

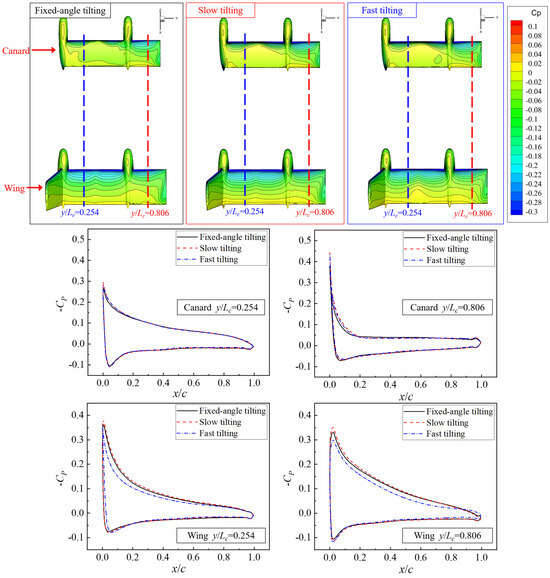

As can be observed from the wing section pressure coefficient (CP) distribution diagrams presented in Figure 14, at a 60° tilting angle, the pressure difference between the two tilt-wing sections is significant, indicating a strong interference effect of the propellers on the tilt-wings. For the canard y/Lc = 0.254 section, the peak negative pressure is relatively large. An increase in tilting speed reduces the negative pressure on the upper surface. In contrast, the y/Lc = 0.806 section exhibits a small pressure difference due to severe stall, and dynamic tilting speed enhances the pressure difference between the upper and lower surfaces. Especially during fast tilting, where the negative pressure at the wing trailing edge increases substantially. The CP variations in the two wing sections differ from those of the canard. Tilting speed increases the maximum negative pressure coefficient of both sections, with a greater increment observed under slow tilting compared to fast tilting. Thus, tilting speed effectively improves the aerodynamic force of the wing in this section.

Figure 14.

CP of tilt-wing’s characteristic sections at 60° tilting angle with different tilting speeds.

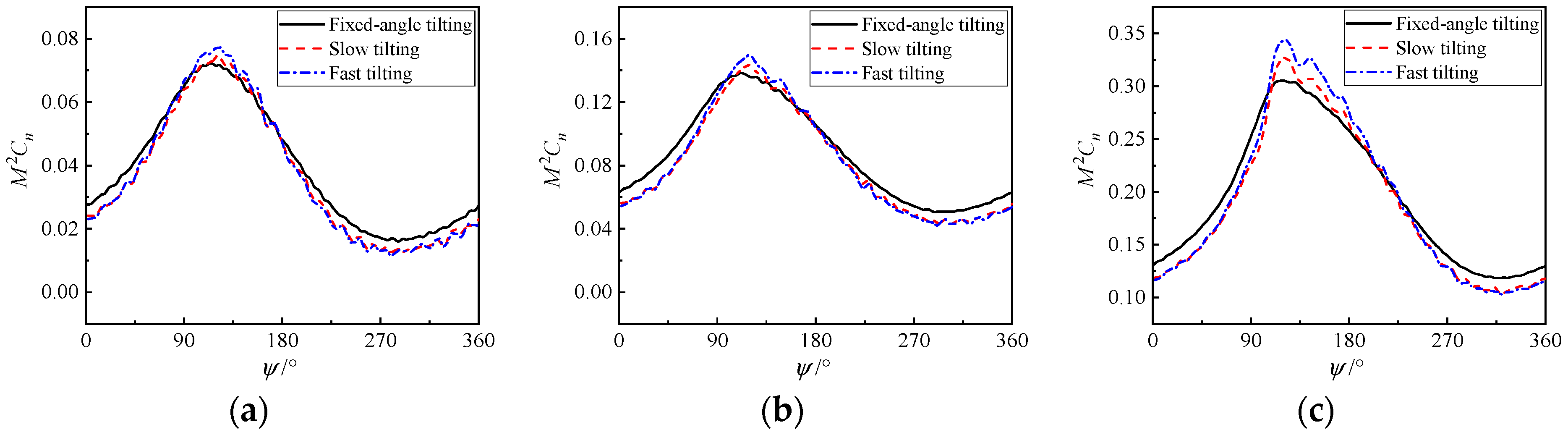

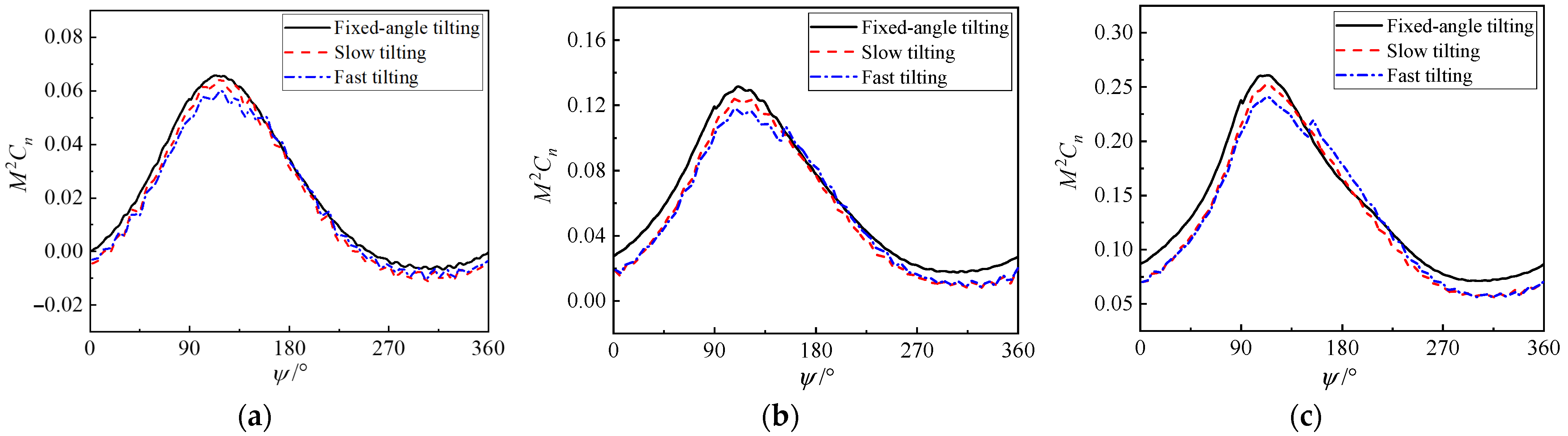

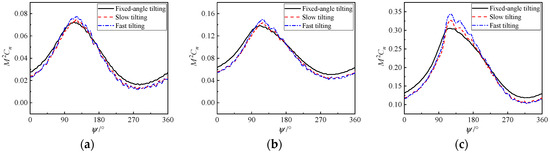

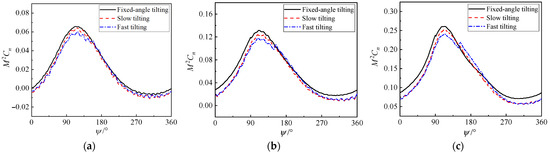

In transition flight, the aerodynamic performance of the rear propellers is jointly influenced by the front propellers, canard, wings, and tilting speed. Taking the rear outer propeller as an example, Figure 15 presents the variation curves of vertical load during one rotation of different blade sections. In this figure, the ordinate M2Cn = N/(1/2ρMa2c) (N is normal force; Ma denotes Mach number; c is chord) denotes the normal force coefficient of the propeller blade section. It can be observed from the figure that the load variation law of each section with tilting speed is similar: tilting speed increases the load near the azimuth angle range of 120–180°, while reducing the propeller disk load at all other azimuth angles. The maximum propeller disk load increases significantly under fast tilting, whereas the loads at other azimuth angles are basically the same as those under slow tilting. The aerodynamic load on the blade’s near-tip cross-sections is notably substantial, and among all operational parameters, the tilting speed exerts the most significant influence on the variation in this load. As illustrated in Figure 15c, the maximum aerodynamic load on the blade’s near-tip cross-sections increases by more than 30% under specific tilting speed conditions.

Figure 15.

Blade section load distribution at 60° tilting angle with different tilting speeds. (a) r/R = 0.49; (b) r/R = 0.75; (c) r/R = 0.99.

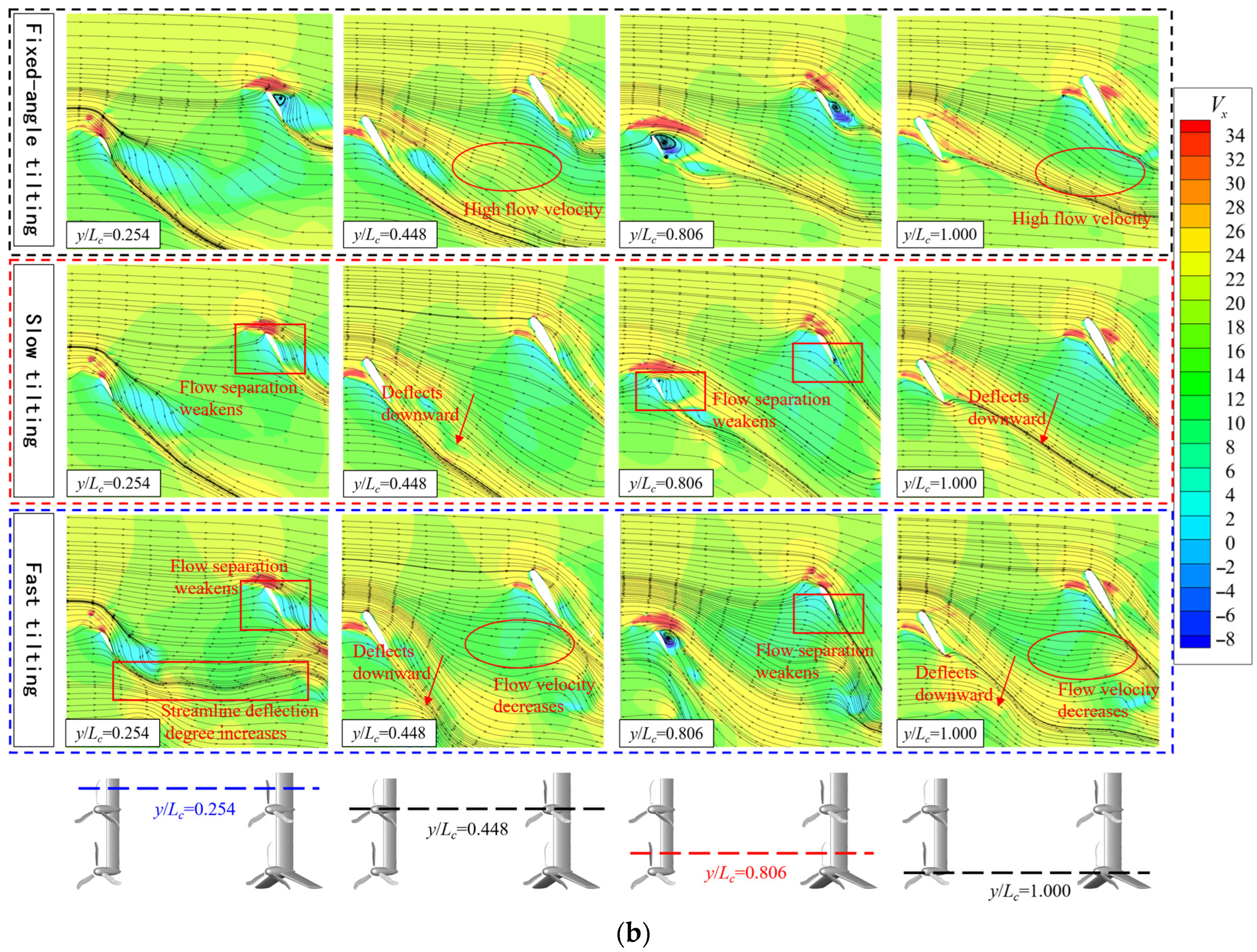

Then, Figure 16 presents the flow fields of each tilt-wing section under different tilting speeds at a 30° tilting angle. From Figure 16a’s vorticity contours, it can be observed that the propeller wake has developed relatively completely at a 30° tilting angle. Tilting speed reduces the horizontal development of the wake while enhancing its chord-wise development along the tilt-wings. On the sections behind the propellers, tilting speed makes the wake vortex development direction closer to the tilt-wings, increasing the propeller–wing interference. On the wing y/Lc = 0.806 section, the vorticity of rapid tilting concentrates at the wing trailing edge, leading to a slight decrease in aerodynamic performance. As shown in Figure 16b, a comparison of the velocity distributions reveals that tilting speed has a minor impact on the velocity streamlines of each section, mainly increasing the flow velocity above the tilt-wings. At this tilting angle, the canard section most affected by tilting speed is the y/Lc = 0.806 section. This section experiences flow separation due to propeller interference, while the canard with slow tilting exhibits the smallest vorticity on the upper surface and the least flow separation. In contrast, no significant flow separation is observed on all wing sections. Tilting speed also has a relatively large impact on the y/Lc = 0.806 section, with the trailing edge velocity of the fast-tilting wing decreasing significantly.

Figure 16.

Flow field distribution diagrams of tilt-wing’s characteristic sections at 30° tilting angle with different tilting speeds. (a) Vorticity Contours. (b) Velocity Streamlines.

As can be observed from the wing section CP distribution diagrams at a 30° tilting angle in Figure 17, the tilt-wing’s aerodynamic force has largely recovered at this angle, and the propeller’s influence on the sections has weakened. However, the pressure difference in the tilt-wing’s sections with a reduced angle of attack (due to propeller interference) is still greater than that of the sections with an increased angle of attack. Dynamic tilting speed has little impact on the pressure coefficient of y/Lc = 0.254 section, mainly altering the negative pressure at the front part of the y/Lc = 0.806 section. Notably, tilting speed increases the negative pressure of the y/Lc = 0.806 section on the canard, with a higher negative pressure observed under slow tilting compared to fast tilting. For the wing, tilting speed exerts distinct effects on the y/Lc = 0.806 section: slow tilting increases the maximum negative pressure, while fast tilting reduces it.

Figure 17.

CP of tilt-wings characteristic sections at 30° tilting angle with different tilting speeds.

Figure 18 presents the loads of different sections of the rear propeller at a 30° tilting angle. It can be observed that tilting speed reduces the propeller load of each section, and the reduction in propeller disk load increases with the increase in tilting speed. The load variations in each section at different azimuth angles are similar, but the aerodynamic load of the section near the propeller tip is relatively large. As shown in Figure 18c, fast tilting reduces the load by 34% near the azimuth angle of 310°.

Figure 18.

Blade section load distribution at 30° tilting angle with different tilting speeds. (a) r/R = 0.49; (b) r/R = 0.75; (c) r/R = 0.99.

4. Conclusions

In the current study, a CFD numerical simulation method suitable for flow field analysis during the dynamic tilting process of DMT aircraft is developed. The aerodynamic characteristic variation laws and flow field evolution characteristics of multi-propellers and tilt-wings during the dynamic tilting process are investigated, and the main conclusions are drawn as follows:

- This paper establishes an overset mesh system and flow field numerical method applicable to DMT aircraft. Case study validation demonstrates that the body-fitted CFD method achieves high computational accuracy for aerodynamic characteristics under various disturbances. The proposed method enables the simulation of unsteady aerodynamic characteristics during the dynamic flight of DMT aircraft.

- The developed CPU-GPU parallel acceleration method effectively improves the flow field numerical simulation speed of the CFD method. It achieves a speedup ratio of 14.37 in the full-aircraft body-fitted mesh CFD calculation of DMT aircraft.

- During the full dynamic tilting process, the aerodynamic force of the propellers exhibits a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, gradually transitioning from vertical force to forward force. The lift and drag of the tilt-wings also follow a similar trend, but the tilting angles corresponding to their extreme points differ. In dynamic tilt conditions, the CT of both the forward and aft propellers is lower than that in fixed-angle conditions, and the value is similar. However, the tilting speed exerts distinct positive or negative effects on the lift and drag of the canard and wing at different tilting angles. Compared with fast tilting, the wing under slow tilting can achieve a higher peak lift coefficient when the drag is similar.

- Dynamic tilting speed affects the aerodynamic performance of multi-propeller and tilt-wings by altering the local airflow velocity and vortex-lift surface interference. The effect of tilt speed differs between the forward and rear sections of the tilting axis of the canard and wing. It facilitates lift generation under significant flow separation, while high tilting speed conversely reduces aerodynamic force when flow separation is slight. Fast tilting greatly modifies the wake of the front propellers and canard, leading to varying effects on the aerodynamic force of the wing at different tilting angles.

In the future, experimental research will be conducted on the aerodynamic characteristics and flow mechanisms of this configuration of aircraft to further verify the computational accuracy of the method proposed in this paper, and to conduct a more in-depth exploration of the flow impacts caused by dynamic tilting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and Y.S.; methodology, J.Z. and Z.H.; software, T.M. and Z.H.; validation, J.Z. and T.M.; formal analysis, J.Z. and Y.S.; investigation, Y.S. and G.X.; data curation, J.Z. and T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and T.M.; writing—review and editing, Z.H. and G.X.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, G.X.; funding acquisition, G.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China: 12572300.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers for their insights and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| eVTOL | electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing |

| DMT | Distributed multi-propeller tilting-wing |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CPU | Central processing unit |

| GPU | Graphics processing unit |

| DEP | Distributed Electric Propulsion |

| RANS | Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes |

| S-A | Spalart–Allmaras |

| MPI | Message passing interface |

| RADAS | Rotorcraft Aerodynamics and Aeroacoustics Solver |

| LU-SGS | Lower-Upper Symmetric Gauss-Seidel |

| OpenMP | Open Multi-Processing |

| A | = Propeller disk area, πR2 (m2) |

| α | = Angle of Attack (°) |

| c | = Chord length (m) |

| CD | = Drag coefficient, D/(1/2ρVtip2S) (non-dimensional) |

| CL | = Lift coefficient, L/(1/2ρVtip2 S) (non-dimensional) |

| CT | = Trust coefficient, Trust/(1/2ρVtip2A) (non-dimensional) |

| CP | = Pressure coefficient, (p-p0)/(1/2ρVtip2) (non-dimensional) |

| Cpower | = Power coefficient, P/(1/2ρVtip2AΩ) (non-dimensional) |

| D | = Drag (N) |

| FM | (non-dimensional) |

| K | = Thermal conductivity (W/(m·K)) |

| L | = Lift (N) |

| Lc | = Canard semi-span (m) |

| Lw | = Wing semi-span (m) |

| M2Cn | = Normal force coefficient, N/(1/2ρMa2c) (non-dimensional) |

| Ma | = Mach number (non-dimensional) |

| N | = Normal force (N) |

| Ω | = Propeller rotational speed (rad/s) |

| P | = Power (W) |

| p | = Absolute pressure (Pa) |

| p0 | = Atmospheric pressure (Pa) |

| R | = Propeller Radius (m) |

| ρ | = Air density (kg/m3) |

| S | = Tilt-wings Reference Area (m2) |

| σ | = Rotor solidity (non-dimensional) |

| T | = Temperature (K) |

| τ | = Tilting angle (°) |

| θ | = Twist angle (°) |

| θ0 | = Pitch angle (°) |

| μ | = Fluid viscosity (Pa·s) |

| V∞ | = Flight speed (m/s) |

| Vtip | = Propeller tip speed, ΩR (m/s) |

| Δζ | = Local displaced section (m) |

References

- Wang, M.; Cao, Y. A Review of Coaxial Compound Helicopters: Aerodynamics and Flight Dynamics. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 4001–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, T.C. Simulation and Analysis of V-22 Tiltrotor Aircraft Forward-Flight Flowfield. J. Aircr. 1996, 33, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Zhang, T.; Barakos, G.N. Numerical Simulation of Distributed Propulsion Systems Using CFD. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Aerial E-Mobility Perspective: Anticipated Designs and Operational Capabilities of eVTOL Urban Air Mobility (UAM) Aircraft. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 9, 413–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, P.; Wei, P. Energy Optimal Speed Profile for Arrival of Tandem Tilt-Wing eVTOL Aircraft with RTA Constraint. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE CSAA Guidance Navigation and Control Conference, Xiamen, China, 10–12 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchini, A.; Cestino, E. Electric VTOL Configurations Comparison. Aerospace 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wan, Z.; Chen, J. Aerodynamic Interference of a Variable-Radius Rotor/Wing During Transition Flight. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3126, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmuddin, F. Rotor Blade Performance Analysis with Blade Element Momentum Theory. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.; Milz, D.; Armanini, S.; Looye, G. Transition Strategies for Tilt-Wing Aircraft. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2025, 48, 2326–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Ning, C. Investigation of Blade Root Clearance Flow Effects on Pressure Fluctuations in an Axial Flow Pump. Machines 2025, 13, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, K.; Hall, K.C.; Dowell, E.H. Computationally Fast Harmonic Balance Methods for Unsteady Aerodynamic Predictions of Helicopter Rotors. J. Comput. Phys. 2008, 227, 6206–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomin, H.; Wagner, S. Navier-Stokes Analysis of Helicopter Rotor Aerodynamics in Hover and Forward Flight. J. Aircr. 2002, 39, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, G.R.; Raghavan, V.; Duque, E.P.N.; McCroskey, W.J. Flowfield Analysis of Modern Helicopter Rotors in Hover by Navier-Stokes Method. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 1993, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poling, D.R.; Rosenstein, H.; Rajagopalan, G. Use of a Navier-Stokes Code in Understanding Tiltrotor Flowfields in Hover. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 1998, 43, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, M.A.; Grauer, W.K.; Paisley, D.J. Rotor/Airframe Interactions on Tiltrotor Aircraft. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 1990, 35, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.J.; Barakos, G.N. Numerical Simulations on the ERICA Tiltrotor. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 64, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Narramore, J.C. Computational Simulation and Analysis of Bell Boeing Quad Tiltrotor Aero Interaction. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2009, 54, 42002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Zhao, X.; Kyprianidis, K. A Review of Concepts, Benefits, and Challenges for Future Electrical Propulsion-Based Aircraft. Aerospace 2020, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, O.; Aprovitola, A.; de Rosa, D.; Pezzella, G.; Viviani, A. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analyses of a Wing with Distributed Electric Propulsion. Aerospace 2023, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni, D.; Monica, S.; Geoffrey, B. Tiltwing Multi-Rotor Aerodynamic Modeling in Hover, Transition and Cruise Flight Conditions. In Proceedings of the AHS International 74th Annual Forum & Technology Display, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 14–17 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, A.; Mikic, G. Transition Performance of Tilt Propeller Aircraft. In Proceedings of the 78th Annual Forum & Technology Display of the Vertical Flight Society (VFS), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 10–12 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvigneau, R.; Kloczko, T.; Praveen, C. A Three-Level Parallelization Strategy for Robust Design in Aerodynamics. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Parallel Computational Fluid Dynamics, Lyon, France, 19–22 May 2008; Available online: https://math.tifrbng.res.in/~praveen/doc/parcfd_duvigneau.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Wan, Y.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H. An Efficient Communication Strategy for Massively Parallel Computation in CFD. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 7560–7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, A.; Camelli, F.F.; Löhner, R.; Wallin, J. Running Unstructured Grid-Based CFD Solvers on Modern Graphics Hardware. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2011, 66, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.S.; Martins, J.R.R.A. Tilt-Wing eVTOL Takeoff Trajectory Optimization. J. Aircr. 2020, 57, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.H.; Lee, K.; Hwang, J.T. Large-Scale Design and Economics Optimization of eVTOL Concepts for Urban Air Mobility. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droandi, G.; Gibertini, G. Aerodynamic Blade Design with Multi-Objective Optimization for a Tiltrotor Aircraft. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2015, 87, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekreijse, S.P. Elliptic Grid Generation Based on Laplace Equations and Algebraic Transformations. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 118, 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, G.; Shi, Y. A Robust Overset Assembly Method for Multiple Overlapping Bodies. Numer. Methods Fluids 2021, 93, 653–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, G.; Shi, Y.; Xia, R. Airfoil–Vortex Interaction Noise Control Mechanism Based on Active Flap Control. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2022, 35, 04021111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, G.; Shi, Y.; Hu, Z. Analysis of the Aeroacoustic Characteristics of a Rigid Coaxial Rotor in Forward Flight Based on the CFD/VVPM Hybrid Method. Aerospace 2023, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yu, P.; Xu, G.; Shi, Y.; Gu, F.; Zou, A. Comparative Study of Soft In-Plane and Stiff In-Plane Tiltrotor Blade Aerodynamics in Conversion Flight, Using CFD-CSD Coupling Approach. Aerospace 2024, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Kwon, O.J. Unstructured Mesh Navier-Stokes Calculations of the Flowfield of a Helicopter in Hover. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2002, 47, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R. Two-Equation Eddy-Viscosity Turbulence Models for Engineering Applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, Q. CFD Calculations on the Unsteady Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Tilt-Rotor in a Conversion Mode. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2015, 28, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Jameson, A. Lower-Upper Symmetric-Gauss-Seidel Method for the Euler and Navier-Stokes Equations. AIAA J. 1988, 26, 1025–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, C.W.; Amsden, A.A.; Cook, J.L. An arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian Computing Method for All Flow Speeds. J. Comput. Phys. 1974, 14, 227–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagum, L.; Enon, R. OpenMP: An Industry Standard API for Shared-Memory Programming. IEEE Comput. Sci. Eng. 1998, 5, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldini, P.C.; Hirai, R.; Costa, P.; Peeters, J.W.R.; Pecnik, R. CUBENS: A GPU-Accelerated High-Order Solver for Wall-Bounded Flows with Non-Ideal Fluids. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2025, 309, 109507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalay, P.G.; Muller, T.; Gidofalvi, G.; Lischka, H.; Shepard, R. Multiconfiguration Self-Consistent Field and Multireference Configuration Interaction Methods and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 108–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droandi, G.; Zanotti, A.; Gibertini, G. Aerodynamic Interaction Between Rotor and Tilting Wing in Hovering Flight Condition. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2015, 60, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C.D.; Pham, D.V.; Whiteside, S.S. Evaluation of VSPAERO Analysis Capabilities for Conceptual Design of Aircraft with Propeller-Blown Wings. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION Forum, Virtual, 2–6 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Litherland, B.L.; German, B.J. Development of an Unsteady Vortex Lattice Method to Model Propellers at Incidence. AIAA J. 2022, 60, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).