Abstract

The area of robot autonomous navigation has become essential for reducing labor-intensive tasks. These robots’ current navigation systems are based on sensed geometrical structures of the environment, with the engagement of an array of sensor units such as laser scanners, range-finders, and light detection and ranging (LiDAR) in order to obtain the environment layout. Scene understanding is an important task in the development of robots that need to act autonomously. Hence, this paper presents an efficient semantic mapping system that integrates LiDAR, RGB-D, and odometry data to generate precise and information-rich maps. The proposed system enables the automatic detection and labeling of critical infrastructure components, while preserving high spatial accuracy. As a case study, the system was applied to a desalination plant, where it interactively labeled key entities by integrating Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) with vision-based techniques in order to determine the location of installed pipes. The developed system was validated using an efficient development environment known as Robot Operating System (ROS) and a two-wheel-drive robot platform. Several simulations and real-world experiments were conducted to validate the efficiency of the developed semantic mapping system. The obtained results are promising, as the developed semantic map generation system achieves an average object detection accuracy of 84.97% and an average localization error of 1.79 m.

1. Introduction

Robots have become widespread in daily life, and they are widely used in factories and many industrial places, where they perform dangerous tasks that humans cannot [1]. Social, medical, and guidance robots provide various services to improve quality of life [2,3,4].

For mobile robots, their ability to navigate the environment is important. This involves avoiding hazardous situations such as collisions with obstacles, as well as exposure to extreme environmental conditions such as high temperatures, radiation, or adverse weather [5]. Automated navigation is a robot’s ability to determine its location in its frame of reference and then plan a path toward its destination. In order to navigate its environment, a robot requires a representation, for instance, a map of the environment, and the ability to interpret this representation [6,7].

Grid maps obtained by geometric-based navigation systems are efficient in collecting geometry information about the area of interest [8]. However, when a robot needs to understand the navigation environments, grid maps lack necessary semantic information. Modeling and recognizing the scene structure of the environment is an essential component of all intelligent systems, such as mobile robots, to fully understand and perceive a complex environment in the same way as a human [9].

Autonomous robots are useful across a diverse range of applications [10,11], including desalination plants. These facilities subtract salt and other impurities from seawater to produce fresh water that is suitable for human consumption and agricultural use. These plants typically contain a massive number of long-range, connected pipes; when these pipes leak, it harms the water piping system by increasing energy consumption and reducing the production rate.

Regular desalination plant inspections are essential for ensuring operational efficiency, maintaining water quality, complying with regulations, ensuring safety and security, conserving resources, and managing risks effectively. By prioritizing inspection and maintenance efforts, desalination plants can function consistently and sustainably, and continue to provide a vital source of clean water to communities around the world. The task of leak detection in desalination plants has received considerable attention recently, driven by the requirement to efficiently detect and localize leaks. Doing so with an autonomous robot requires a constructed map of the desalination plant environment. Therefore, developing an efficient map construction system via semantic information is a requirement to recognize and classify pipes in the desalination plant [12,13].

This paper therefore focuses on robot semantic navigation in desalination plants for the purpose of constructing a semantic map with rich plant information that can detect and locate water pipes in order to facilitate leak inspection. To achieve this, the research project employs a sensor fusion approach that integrates LiDAR-based technology, wheel odometry, and vision-based systems to enhance perception accuracy and environmental understanding. The research objectives are as follows:

- Investigate and analyze the limitations of existing semantic navigation frameworks.

- Design and construct a specialized multimodal dataset representing real desalination plant conditions.

- Develop an intelligent semantic mapping system that fuses LiDAR-based geometry, RGB-D vision, and odometry data to automatically detect, label, and localize critical elements within desalination facilities.

- Implement and validate the proposed system within the ROS environment, demonstrating its ability to perform semantic mapping in support of industrial monitoring.

The remainder of this paper is presented as follows: Section 2 discusses recent robot semantic navigation systems, whereas Section 3 discusses the proposed semantic map production system. Section 4 presents the experiment testbed and results. In Section 5, the results are discussed and analyzed. Finally, Section 6 concludes the work presented in this paper and suggests future research.

2. Related Work

Existing robot semantic navigation systems can be categorized into three main categories, based on the employed sensing technology: LiDAR, vision, and hybrid systems [14]. LiDAR-based systems employ LiDAR sensing technology to classify the environment based on a collection of LiDAR data frames, whereas vision-based systems adopt digital cameras to capture images from the field and then classify the objects in that field. Finally, hybrid systems integrate vision methods with LiDAR information to enhance overall semantic map accuracy.

2.1. LiDAR-Based Systems

Data obtained from a LiDAR unit can be used to classify objects and places in the environment, and hence obtain semantic information. However, the use of LiDAR sensor data alone restricts the range of objects that can be effectively classified. For instance, a LiDAR-based classification system was proposed [15] that involved classifying forest environment characteristics using LiDAR sensor information. In [16], a two-stage framework for ground-plane detection was introduced, where the first stage applied a local, height-based filtering method [17] to eliminate a large portion of non-ground points, whereas the second stage employed eight geometric features within a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier to distinguish between ground and non-ground data.

Another research [18] involves the development of a single-LiDAR-based system capable of continuously identifying and tracking human motion in space and time, effectively detecting leg movements in complex environments. Similarly, a deep neural network approach was proposed in [19] to classify LiDAR data into three motion categories: static, movable, and dynamic for improved environmental understanding. Furthermore, the study in [20] developed a machine-learning-based indoor classification framework capable of recognizing four types of environments: doors, halls, corridors, and rooms, in order to enhance semantic awareness and navigation within indoor settings.

2.2. Vision-Based Systems

RGB images obtained from digital cameras can be used to classify objects and places in the environment and, hence, offer rich semantic information for robot navigation applications. This approach requires the employment of a vision system (an RGB camera, for instance) and a classification method to classify objects and places in the obtained RGB images. Vision-based systems have received considerable attention due to their ability to obtain high-resolution semantic maps.

Joo et al. [21] proposed a neuro-inspired cognitive navigation system with three main components: Semantic Modeling Framework (SMF), Semantic Information Processing (SIP), and Semantic Autonomous Navigation (SAN). The experiment showed that the framework can be applied to real-world scenarios. On the other hand, Zhang et al. [22] proposed an indoor social navigation system based on an object semantic network and topological map, which combined two main modules: automatic navigation target selection and segmented global path planning. The proposed system was tested in a real office and home environment using a FABO robot, and the experimental results showed that mobility goals better satisfy the social rules of the FABO robot.

Another study [23] included an architecture for making a robot capable of navigating the indoor environment through semantic decision-making. Applying an object detection algorithm to the scene helped the robot detect four classes of objects: (a) target objects, (b) relational objects, (c) obstacles, and (d) extensions of the general scene. This approach was tested in simulation and real indoor settings.

Qi et al. [24] proposed semantic network mapping for local automated navigation, which relies on improving the occupancy network map with the semantics of objects and places, allowing robots to increase both the accuracy of their navigation skills and their semantic knowledge of the environments. Semantic mapping and navigation experiments were conducted using a FABO robot in a home environment. Experimental results showed that the mapping method had satisfactory accuracy for representing the environment and made the robot capable of accomplishing local navigation tasks in a human-friendly manner.

Wei et al. [25] proposed a semantic information based on an optimized Visual Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (VSLAM) algorithm for dynamic environments. The developed system included four crucial modules: a tracking module, a motion detection module, a semantic segmentation module, and a map-building module. The evaluation of this algorithm was accomplished using the TUM RGB-D dataset and real dynamic scenes.

Liang et al. [26] proposed a method for robot navigation using laser sensors and monocular vision to create a semantic map. The mobile robot could automatically search each office room’s door plate using its monocular vision to identify the room number, which served as an ambient semantic identifier. The experiment was conducted in a laboratory building’s corridor using a mobile robot equipped with a 360-laser sensor that scanned at a frequency of 40 Hz. The outcomes demonstrated that the robot was capable of navigating to a specified destination on the intended floor.

Crespo et al. [27] proposed a semantic information representation for robot navigation tasks, enhancing autonomy by managing high-level abstraction information. The semantic system was tested using a TurtleBot indoor robot, achieving a processing time of 22 ms. Results showed the capacity to approach targets using user-provided semantic information, enabling a more natural connection between humans and robots.

In other research [28], the authors developed an Optical Flow combining MASK-RCNN SLAM (OFM-SLAM), a novel visual SLAM for semantic mapping in dynamic indoor environments. The developed system employed a Mask-RCNN network to detect moving objects; an optical flow method was then applied to detect dynamic feature points. The semantic labels obtained from the Mask-RCNN model were mapped onto the point cloud to create a 3D semantic map containing only static parts of the environment and their semantic information. The developed system has been validated using a 2WD robot and TUM dataset, where the obtained results demonstrated the efficiency of the developed OFM-SLAM system.

In other work [29], the authors presented an efficient semantic perception solution for indoor mobile robot navigation applications. The developed system offered both semantic mappings and could divide the environment area into clusters that represented singular object instances. The presented work improved the robot’s ability to interact with the environment, by using a mask-RCNN approach for image segmentation tasks. The developed indoor navigation system was trained on the SUN-RGBD dataset, which contains 10,335 images with 37 different objects. The obtained results proved the efficiency of the developed system with a mean average precision equal to 0.414.

A different study [30] proposed a practical approach to implement autonomous indoor navigation based on semantic image segmentation using Mobile DeepLabv3. The development was validated using the ADE20K dataset, which consists of 150 classes reduced to 20 classes to easily classify obstacles and roads. The obtained results proved that employing the MobilenetV2 was three times faster than using the exception in training time and 20 times faster at inference time.

Dang et al. [31] developed a binary semantic segmentation classification system to avoid obstacles by designing a multi-scale fully convolutional network (FCN) using the VGG16 model. The dataset’s real environment (Ta Quang Buu library) includes 1470 fully annotated images classified into two categories: ground and nonground. Deng et al. [32] proposed a framework that combined a SLAM and RGB-D camera dataset to train semantic segmentation convolutional neural network (CNN) for rescue robot in a real-world competition environment Rescue-Robot-League (RRL). The Inception-v3 model achieved a performance of 98.99% mean accuracy, 98.93% mean recall, and 96.87% Mean Intersection over Union (IoU) in the testing set.

2.3. Hybrid Systems

Hybrid robot semantic systems employ both LiDAR and vision methods to construct their semantic map. In [3], a semantic grid mapping approach was proposed that integrates data obtained from 2D LiDAR and RGB-D cameras to improve environmental understanding for robot navigation. The LiDAR sensor was used to perform SLAM and generate an occupancy grid map, while object detection on RGB images provided semantic information about surrounding objects. These semantic features were then fused using joint interpolation to produce a high-level, object-aware map for navigation tasks. The developed system was validated using a FABO robot platform in an indoor environment; the average precision was 68.42%, whereas the average recall was 65%.

Each category (LiDAR and vision) has its advantages and drawbacks. For instance, LiDAR-based systems offer low overhead processing requirements and minimum cost. However, LiDAR-based classification systems can only categorize a few environments or objects of interest. On the other hand, vision-based systems require intensive processing capabilities for processing the array of images received from the vision systems. However, vision-based systems allow for more classification types, compared to the LiDAR-based semantic navigation systems.

The work presented in [33] involves an object-oriented SLAM framework that emphasizes data-association, object modeling, and semantic map construction for high-level robot tasks. In [34], Rollo et al. introduced a multi-modal semantic mapping system combining RGB-D camera with LiDAR for object detection and localization within a map. Zhao et al. [35] presented a semi-autonomous navigation system for mobile robots using a local semantic map, enabling mobile robot navigating in unknown indoor environments. On the other hand, Maggio et al. [36] presented a real-time method for building open vocabulary 3D scene graphs that dynamically adjust map granularity based on the task context in order to enhance robot semantic mapping and planning in unstructured environments.

According to the conducted research study, no existing approaches have solely addressed semantic mapping in desalination plant environments. For instance, one study [37] offered a survey of SLAM-enabled robotic systems developed for applications in water and sewer pipe networks. The study presented valuable visions into the design of robotic platforms capable of operating in highly constrained and hazardous pipeline environments. However, its primary focus lies on the navigation problem, particularly a robot’s ability to traverse complex pipe structures. Although this is an essential aspect of SLAM deployment in such domains, this particular study delivered limited discussion of other critical challenges, including the accuracy and reliability of map construction, the robustness of sensor fusion in environments with degraded signals, and the adaptability of algorithms to varying pipe geometries or conditions.

3. Semantic Map Production System

Unlike conventional indoor or outdoor settings, desalination plants present domain-specific challenges due to their dense networks of interconnected pipes, and pump motors. These structural and functional components create complex geometries, reflective surfaces, and occlusions that complicate perception, feature extraction, and data association, thereby necessitating tailored methodologies for precise semantic map construction. Addressing these challenges requires tailored methodologies that leverage advanced sensing modalities such as LiDAR for structural mapping, depth cameras for capturing fine-grained geometry, and multi-modal sensor fusion (e.g., LiDAR, RGB, and odometry) to improve semantic map construction.

This project aims to develop an efficient robot semantic navigation system to recognize and map the location of the pipes in the desalination area and then construct a semantic map. The developed system consists of a set of perception units: vision, geometry, and wheel odometry. The former employs an efficient vision system to gather scene information from the area of interest and then analyze the necessary information, whereas the geometry unit employs a LiDAR system, for instance to collect the geometry information of the area of interest and obtain a geometric map. Finally, the wheel odometry subsystem is integrated with the vision system for the purpose of estimating the robot’s position, and then providing an effective location for the object of interest. The overall concept of the developed system semantic map construction system is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The overall concept of the desalination plant inspection system.

3.1. Operational Stages of the Developed System

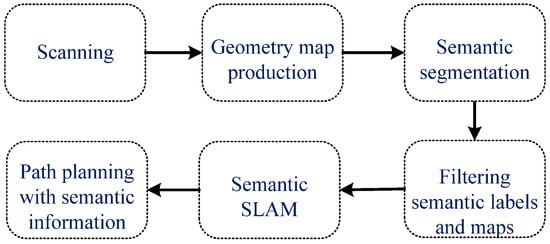

The developed robot semantic navigation system consists of six main phases as presented in Figure 2. Phase 1 involves the scanning function through the adoption of three different units: LiDAR for obtaining geometry details, a vision unit for object detection and classification, and a wheel odometry unit for estimating the traveled distance by the robot. The LiDAR A1 unit has been employed to construct the map with geometry information, whereas the RGB-D camera has been adopted to obtain semantic information along with the data received from odometry subsystem.

Figure 2.

The main phases of the presented robot semantic navigation system.

The geometry map is constructed in Phase 2, where the data collected from the LiDAR unit is fed to the ROS SLAM package for the purpose of constructing a 2D geometry map. The LiDAR unit is able to identify the static and dynamic obstacles that exist within the area of interest.

The semantic segmentation function takes place in Phase 3, where the RGB-D camera is integrated to obtain object detection and classification, and then estimates the distance to the detected object in order to construct a semantic map with rich semantic information. Object detection is an essential task to obtain an efficient semantic map for the environment of interest; therefore, it is important to employ a reliable object detection model to enhance the semantic map accuracy. For this purpose, this paper investigated the efficiency of two YOLO (v5 and v8) object detection models to detect objects in a desalination plant environment, through the processing of input frames received from RGB-D camera unit in the robot platform. In recent research works [38,39], the YOLO object detection model has achieved significant results in the area of robot semantic navigation.

The employment of YOLO v5 and v8 models requires the integration of suitable vision dataset that consist of objects that potentially exist in desalination plant environments. Unfortunately, for desalination plant environments, no publicly available dataset currently includes the specific objects and equipment typically found in such facilities. Therefore, it is essential to construct a dedicated vision dataset that accurately represents the relevant objects and spatial configurations encountered in desalination plants.

The fourth phase involves labeling the detected objects in the robot navigation area, where the RGB-D camera collects images from the environment, then processes, analyzes, and detects objects using the pretrained YOLO model. Moreover, the robot has the capability to estimate the distance to the detected object using the RGB-D camera, where depth information is available.

The fifth phase involves building a semantic (visual) SLAM that consists of rich information, including the recognized objects and the paths between these objects. Finally, the sixth phase involves determining the possible paths between the recognized objects according to the semantic information.

3.2. Sensor Fusion-Based System for Semantic Mapping

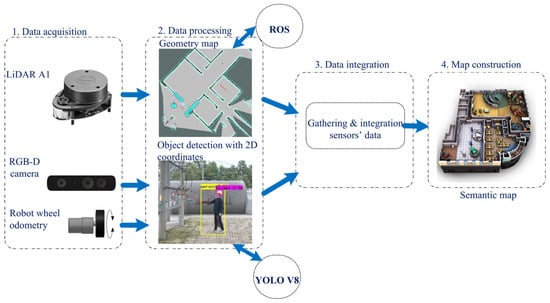

The developed semantic mapping system is based on sensor fusion, which integrates data from multiple sensors to achieve a more reliable, accurate, comprehneisve, and robust understanding of the desalination plant environment. This process minimizes noise and uncertainty, and improves the overall performance of the obtained semantic map. Figure 3 presents the sensor fusion architecture of the developed semantic mapping system.

Figure 3.

Sensor fusion architecture of the developed semantic mapping system.

To construct an accurate semantic map of the desalination plant, a feature-level sensor fusion mechanism was implemented to combine data from the LiDAR unit, RGB camera, and odometry sensors. The fusion process begins with the LiDAR and odometry data, which are integrated through a 2D SLAM algorithm to generate an occupancy grid map and continuously estimate the robot’s pose within the environment. This layer offers the geometric foundation of the semantic map. The fusion system operates in four stages: data from the LiDAR A1, RGB-D camera, and wheel odometry are collected, processed, and fused to form a geometric map. Using YOLOv8, the RGB-D camera detects and localizes pipeline structures, with depth data aligned to the LiDAR frame. The integrated information is then used to generate a semantic map that accurately represents the environment.

Finally, the fused data are represented in a semantic layer that overlays object labels (e.g., pipes, and pumps) onto the geometric map. This integration combines the structural accuracy of LiDAR and odometry with the semantic and depth perception of the RGB-D camera, resulting in a robust and precise semantic mapping system suitable for inspection and navigation in complex desalination plant environments.

The developed sensor fusion system combines complementary information from several sensors to construct a representation that is more accurate and robust than any single sensor alone [19,20,21,22,23]. This enhances scene understanding (semantic labeling, object localization, and mapping) in environments where a single modality may fail (e.g., low texture for vision, reflective surfaces for LiDAR).

3.3. Desalination Plant Dataset

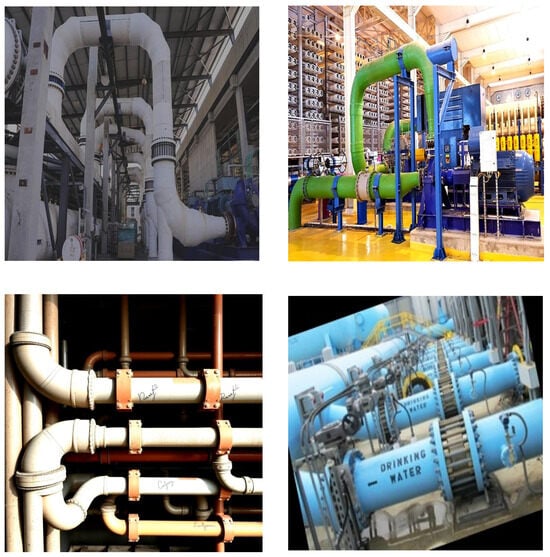

This paper’s primary objective is to identify the position of pipes within desalination plant environments to assess potential leaks through the employment of an effective semantic mapping approach. However, widely used datasets such as COCO and PASCAL do not contain relevant objects like pipes, or water pumps, which are key components in such settings. The dataset should encompass key components such as horizontal and vertical pipes, and water pumps. Therefore, this subsection introduces a new, dedicated dataset that effectively includes images of horizontal and vertical pipes as well as water pumps.

The desalination plant dataset was constructed using 197 images gathered from diverse sources, including real-world photographs, Google image searches, and simulation environments. However, for the purpose of enhancing the dataset, several data augmentation techniques were applied, generating new variations for each original image, resulting in a total of 765 images. The applied transformations included image rotation, brightness and contrast adjustment, cropping/zooming, noise addition, background color alteration, and grayscale conversion, where all images were saved in JPG format. Table 1 presents general details about the constructed dataset, whereas Figure 4 shows several sample images from the constructed dataset.

Table 1.

Summary of key attributes of the constructed desalination plant dataset.

Figure 4.

Sample images from the constructed dataset.

Subsequently, the labeling process was conducted, during which a dedicated annotation tool was used to manually label the objects in the constructed dataset, including vertical, horizontal, and pump components. The Roboflow platform was employed to perform this task efficiently and ensure consistent annotations across all samples. Finally, a quality assurance procedure was implemented to review and validate the annotations, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the labeling process before proceeding to the training phase.

The gathered dataset has been made publicly available on Kaggle, providing open access for research and development purposes, consisting of 9409 annotated objects. Table 2 summarizes the distribution of these annotated objects within the desalination plant dataset, detailing the number of instances for each object category.

Table 2.

Distribution of annotated objects within the desalination dataset.

The training, validation, and testing processes were conducted to develop a robust object detection model specifically designed for desalination plant environments. As summarized in Table 3, the dataset was divided into three subsets (training, validation, and testing) in order to ensure balanced representation and to accurately assess the model’s generalization capability. The training phase involved optimizing the model parameters and learning weights using the hyperparameters listed in Table 4, which were carefully selected to achieve optimal convergence and detection accuracy. During this phase, the model iteratively learned the visual characteristics of key objects (e.g., vertical, horizontal, and pump components) from the annotated dataset, while the validation subset was used to fine-tune the model and prevent overfitting. Finally, the testing subset was employed to objectively assess the model’s performance under unseen conditions, ensuring its reliability for real-world deployment in desalination plant monitoring and inspection tasks.

Table 3.

Distribution of training, validation, and testing subsets.

Table 4.

Training parameters for training YOLO v5 and v8 models.

Table 5 presents a detailed breakdown of the number of annotated instances for each object class (vertical pipes, horizontal pipes, and pumps), across the training, testing, and validation subsets. This distribution reflects how the dataset was structured to ensure sufficient representation of each class during model development and evaluation. As presented, the majority of samples were allocated to the training subset, providing the model with adequate exposure to varied object appearances and environmental conditions. The testing and validation subsets were constructed to include a balanced proportion of examples for each class, enabling a reliable assessment of the model’s generalization capability and its performance on unseen data.

Table 5.

Detailed breakdown of annotated instance counts for each object class.

However, the class distribution reveals a notable imbalance, with the vertical and pump classes containing substantially more samples than the horizontal class. This disparity can bias the detector toward the majority classes, leading to higher precision and recall for vertical and pump objects while reducing the model’s ability to reliably recognize the underrepresented horizontal class. Consequently, this imbalance also propagates to the localization stage, where majority classes typically exhibit more stable bounding-box predictions and lower localization error, whereas minority classes tend to show increased variability and reduced positional accuracy due to limited training exposure. Therefore, special consideration was given during dataset splitting and training to mitigate the effects of class imbalance.

3.4. Object Detection Subsystem

The developed semantic mapping framework relies on an efficient object detection model to enhance environmental understanding. Therefore, in this section, the efficiency of two YOLO object classification models: YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, were studied and analyzed. For both object detection models, the training process involved 100 epochs, allowing both models to achieve optimal performance in detecting and differentiating between objects. The results showcased the model’s precision and reliability, proving its effectiveness in challenging detection tasks.

The employed YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models were pre-trained on the COCO dataset, and then trained again using the constructed desalination plant dataset. The training process was conducted using the Ultralytics framework and leveraged the pretrained weights. Algorithm 1 presents the pseudo-code for the developed semantic map production system.

| Algorithm 1: Semantic map production |

| 01: Define w, h as the 2D navigation area with width = w and height = h 02: Define mr as the mobile robot in the desalination plant environment 03: Define mr(x, y) as the current 2D location of mr obtained from wheel odometry 04: Define mr_maxX as the farthest visited point along the x-axis 05: Define mr_maxY as the farthest visited point along the y-axis 06: Define yoloD as the custom-trained object detection model (desalination dataset) 07: Define depth_to_object(k) as the depth distance (in meters) to detected object k 08: Define navigation_fun() as the navigation function in the area of interest 09: Define semantic_table as a data structure storing objects and their 2D coordinates 10: while (h< mr_maxX < w): 11: while (obs_dist > 100): //ensure safe distance from obstacles 12: if object_detected(yoloD, depth_to_object(k)) == True: 13: semantic_table.add(detected_object, mr(x, y)) 14: Else navigation_fun() 15: end while 16: end while |

4. Experimental Results

This section discusses the experimental testbed areas designed to assess the efficiency of the developed robot semantic navigation system for desalination plants. Moreover, it discusses the results obtained from simulation and real-world experiments that were conducted using ROS development environment and a real robot platform.

4.1. Development Environment

For the purpose of validating the developed semantic mapping approach, the proposed system was first validated through simulation experiments, followed by real-world experiments, to assess its efficiency and practical applicability.

Gazebo v11 simulator was adopted to simulate the desalination plant environment. This is a 3D dynamic simulator with the capabilities to accurately and efficiency simulate different types of robots in complex indoor and outdoor environments. Moreover, Gazebo offers physics simulation at a higher degree of fidelity, a suite of sensors, and interfaces for both users and programs. The designed environment consists of units and tools that mimic real desalination plants, including: a set of pipes, workers, tables, and signs, as presented in Figure 5. The robot platform needs to navigate the desalination plant environment using the LiDAR unit and a vision subsystem in order to construct a semantic map, which helps the robots interact effectively with the desalination plant environment.

Figure 5.

The simulated desalination plant environment using Gazebo.

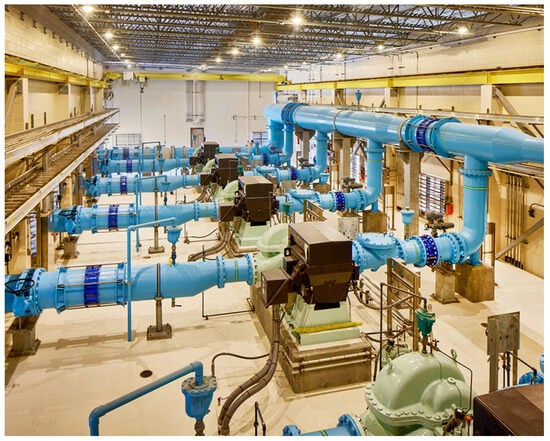

Furthermore, the developed system was validated through real-world experiments conducted within an indoor area of the Duba Desalination Plant, located in the northwestern region of Saudi Arabia. This environment was selected because it mirrors realistic operational conditions, including the presence of critical infrastructure such as interconnected pipes, as well as dynamic elements such as human operators. Conducting experiments in such a setting ensured that the evaluation captured both the structural complexity and the practical challenges typically encountered in desalination facilities. An example of the test area is shown in Figure 6 with a dimension of (36 19) meter (m), where it consists of eight horizontal pipes, six vertical pipes, and two individuals. A list of objects that exist in the simulated and real environments is presented in Table 6.

Figure 6.

Top view of a section within the Duba desalination plant.

Table 6.

List of objects present in the desalination environments (both simulated and real).

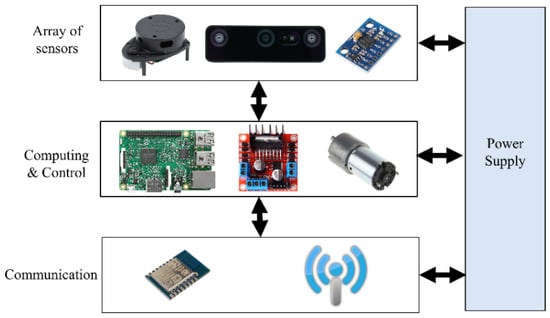

The developed system was validated using a real-robot platform simulated in Gazebo. A two-wheel drive robot that has been adopted recently in several studies [20,39] was adopted for this task and achieved an efficient navigation function. the platform, including onboard sensors, is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Rover two-wheel drive robot platform with onboard sensors.

The adopted robot platform consists of an array of sensors (LiDAR A1, RGB-D camera, and wheel odometry) to perceive its environment. A Raspberry Pi 4 (Cambridge, UK) computer is responsible for processing the data collected from the onboard sensors (LiDAR, RGB-D, and odometry) and generating the corresponding semantic map. All computational tasks, including sensor data fusion and map construction, are executed locally on the Raspberry Pi 4, enabling efficient, real-time operation without reliance on external processing resources. The robot platform has the capability to communicate with other nodes and computers through the available WI-FI communication protocol onboard. Finally, the overall components are powered by a 11.1v Lithium battery with 3200 mAh capacity. Figure 8 shows the robot architecture, whereas Table 7 presents the specifications of the deployed hardware units.

Figure 8.

The architecture of the developed robot platform.

Table 7.

Specifications of the deployed hardware units.

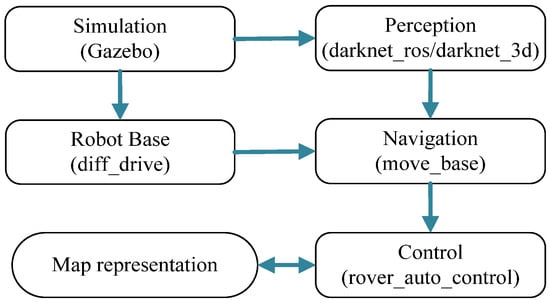

The robot semantic mapping system was implemented using the Robot Operating System (ROS) Noetic framework, running on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS (Focal Fossa). This configuration offers a steady and flexible development environment for integrating sensor data, executing mapping algorithms, and managing communication between the robot’s functional nodes. ROS provides a modular development environment composed of packages, each containing runtime nodes, libraries, and configuration files that communicate and exchange data.

The developed semantic mapping system incorporated several essential ROS packages and third-party libraries to enable simultaneous localization and mapping, visual perception, and data fusion. The mapping and navigation modules were implemented using slam_gmapping, cartographer, and move_base, while sensor data from the LiDAR A1, RGB-D camera, and odometry were handled through rplidar_ros, realsense2_camera, and robot_localization. Visual and depth information were processed using OpenCV and PCL via cv_bridge, image_transport, and pcl_ros, with object detection performed by YOLOv8 (Ultralytics). Spatial alignment between modalities was maintained using the TF and TF2 libraries. Additional utilities such as rviz, rqt, and plotjuggler supported system visualization and debugging. Table 8 presents the main ROS packages and libraries utilized in the developed semantic mapping system.

Table 8.

Main ROS packages and libraries utilized in the developed semantic mapping system.

To generate an accurate semantic map, a custom ROS package named map representation was developed, consisting of several runtime nodes as presented in Figure 9. The rover5_car package controls the robot’s movement by collecting data from onboard sensors, performing obstacle avoidance, and managing navigation. Meanwhile, the perception package integrates nodes and services responsible for executing the YOLO-based object detection and labeling processes, while the robot base package constructs the geometric map using data from the LiDAR A1 sensor.

Figure 9.

The architecture of the developed ROS-based map construction system.

Moreover, for the purpose of allowing the mobile robot to move from its current location to a specified goal location while avoiding obstacles, the move_base package was employed, which integrated global and local planning by connecting a global planner that computes the optimal path across the map, and using the local planner that generates safe velocity commands in real time. This package continuously monitors data from LiDAR, wheel odometry, and the depth camera to dynamically updates the robot’s path to handle unexpected obstacles.

4.2. Results

For both development environments, a set of evaluation metrics was adopted from a recent study [28]; these are essential for assessing the effectiveness of the developed semantic map production system in the context of robotic navigation. These validation parameters include:

- Model classification efficiency: This refers to the evaluation of object classification models based on key performance metrics, including precision, recall, accuracy, and mean average precision (mAP). Precision measures how many times the model correctly detected objects. Recall refers to how many of the actual objects present in the images were correctly detected by the model. The classification accuracy refers to how often the classification model assigns the correct class label to the object it detects. Finally, the Mean Average Precision (mAP) is used to measure the performance of the implemented object detection models.

- Recognized objects ratio (): This refers to the ratio of the overall number of objects that has been correctly classified in the desalination plant environment with comparison to the total existing objects in the same area, as presented below:where j is the index number of a certain class, y is the total number of detected objects in the kth class, m is the total number of existing objects in the kth class, and n is the total number of objects in the simulated environment.

- Localization Error (LE) of detected objects: This estimates the average localization error between the estimated 2D location of an object and the real 2D position of that object, using the Euclidian distance formula.

- Map construction accuracy: This refers to the accuracy of the semantic map generated by integrating LiDAR data with object detection outputs. Hence, by combining geometric information from LiDAR with identified objects and their locations, a comprehensive semantic map is produced that precisely represents both the environment’s structure and its semantic elements.

The results reported in this study are structured into three main components: (i) the evaluation of classification accuracy for the employed models (YOLOv5 and YOLOv8), (ii) the outcomes derived from the simulation-based experiments, and (iii) the findings obtained from real-world experimental validations. For the first component, model performance was assessed using classification efficiency as the primary evaluation metric. In contrast, the second and third components were evaluated using three additional metrics: recognized object ratio, localization error, and map construction accuracy.

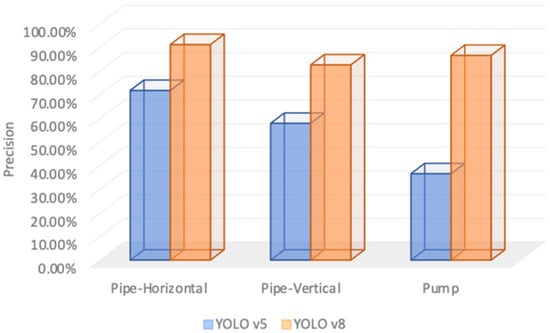

First, the evaluation of classification accuracy for the employed models are considered, including: precision, recall, classification accuracy, and mAP@0.5 for each object detection model. Table 9 presents the precision, recall, classification accuracy, and mAP for each class. For instance, the YOLOv5 model achieved the highest precision of 71.70% for detecting horizontal pipes, followed by 57.80% for vertical pipes, and the lowest precision results of 36.50% for the water pumps. As a result, the robot system could not clearly detect the vertical pipes and water pumps, leading to reduced precision in the results.

Table 9.

The classification results of the YOLOv5 model with the new dataset.

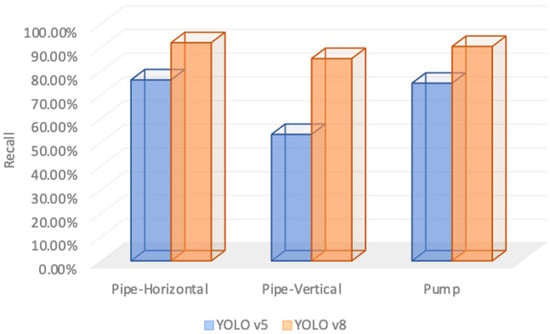

The recall parameter was also evaluated for each class. According to the obtained results, the horizontal pipes received the best recall value with a percentage of 76.40%, whereas the recall value for the pump class was around 75.00%, and the vertical pipe class received the lowest recall result of 53.40%. In addition, the classification accuracy value was also considered for each class. Again, the horizontal pipe class obtained the best classification accuracy with a percentage of 70.53%, whereas the pump class gained the classification accuracy of 57.37%, and the vertical pipe class achieved the minimum classification accuracy value of 52.97%. In addition, the mAP@0.5 for horizontal pipe, pump, and vertical pipe were 63.50%, 60,00%, and 47.70%, respectively.

Table 10 shows the classification results obtained using the YOLOv8 object detection model. For instance, the precision score for the horizontal pipe class was around 90.00%, whereas the precision score for the pump class was around 84.00%. However, the vertical pipe class achieved a reasonable precision score of 80.00%. In addition, the recall score was estimated for each class, and, again, the horizontal pipe obtained the best recall score with a value of 91.10%, whereas the pump achieved a recall score of 88.50%, and finally, the vertical pipe obtained a recall score of 83.00%.

Table 10.

The classification results of the YOLOv8 model with the new dataset.

Moreover, the classification accuracy was analyzed for each class, where the horizontal pipe class acquired a classification accuracy of 91.00%, the pump class obtained an accuracy score of 86.00%, and finally the vertical pipe achieved a classification score of 81.00%. Additionally, the mAP@0.5 value was estimated for each class in the desalination plant environment. The YOLOv8 model achieved 90.00% mAP@0.5 for the vertical pipe class, whereas the horizontal pipe class obtained a mAP@0.5 value of 88.00%, and finally, the pump class achieved a mAP@0.5 of 84.70%.

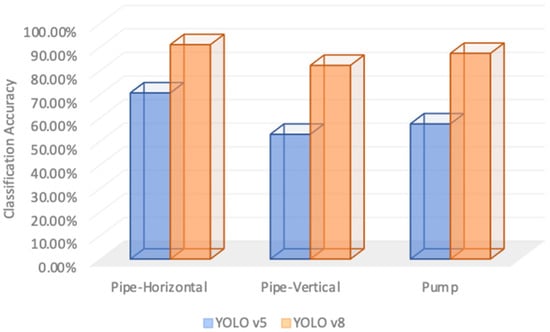

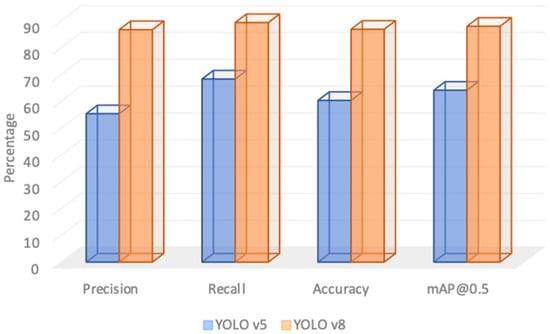

Additionally, a performance comparison was conducted between the YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models. As shown in Figure 10, the precision scores for each class are presented for both models, which indicate that the YOLOv8 model consistently achieves higher precision across all three classes compared to YOLOv5. Figure 11 illustrates the recall scores for each class using both models. As shown, the YOLOv8 model outperforms YOLOv5 by achieving higher recall across all three classes.

Figure 10.

Precision scores for the three object classes using YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models.

Figure 11.

Recall scores for the three object classes using YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models.

Classification accuracy was also evaluated for both the YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models across all three object classes. Classification accuracy reflects the overall effectiveness of the object detection model in correctly identifying and classifying objects. Based on the obtained results, the YOLOv8 model demonstrates superior classification accuracy for all three classes. This reveals that YOLOv8 is more reliable in correctly detecting and categorizing objects within the dataset, reinforcing its improved performance over its predecessor. Figure 12 presents the classification accuracy for the three classes using the two object detection models.

Figure 12.

Classification accuracy for the three object classes using YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models.

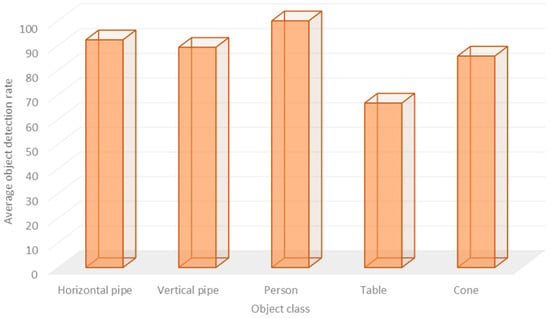

The second component of this experiment involves analyzing the results obtained from simulation experiments using the three-evaluation metrics (recognized objects ratio, localization error, and map construction accuracy). The recognized objects ratio is considered first, where the robot platform traveled in the desalination plant environment and detected the objects of interest using YOLOv8 model. According to the obtained results, the developed system was able to detect almost 88.70% of the total objects in the area of interest. The recognized objects ratio for the horizontal pipes was around 92.30%, whereas the recognized objects ratio for the vertical pipes was around 89.28%.

Of note, the recognized objects ratio for the person class was 100%, meaning that the robot was able to recognize all the workers in the desalination plant environment. However, the detection ratio for the table class was almost 66.66%, since the robot platform was unable to detect the table present in the simulation environment, where this limitation can be attributed to the constraints of the installed camera unit, as its low mounting position restricted the field of view, preventing the camera from detecting all objects within the environment. on the other hand, the recognized object ratio for the cone class was equal to 85.71%, where the robot was able to monitor and detect the presence of a high percentage of the existing cones. Table 11 presents the ratio of recognized objects, whereas Figure 13 depicts the ratio of each recognized object in the desalination plant scenario. These results suggest that the developed semantic map production system offers efficient classification accuracy for the main desalination plant’s components.

Table 11.

Classification results of the YOLOv8 model in the simulated testbed.

Figure 13.

The objects detection ratios for five classes.

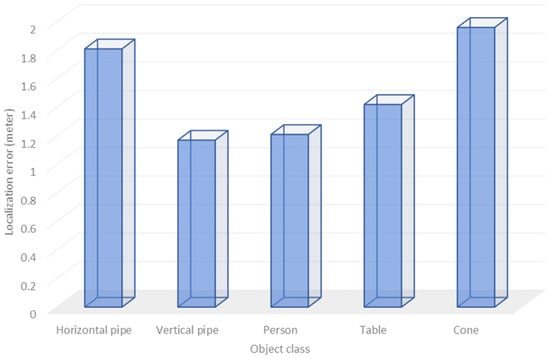

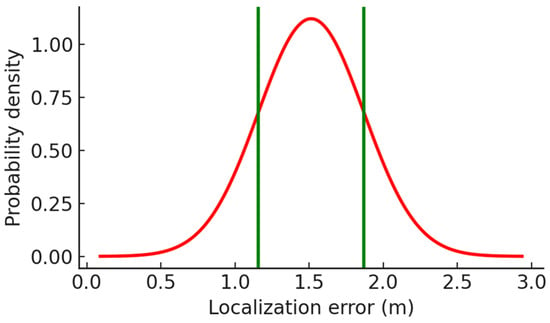

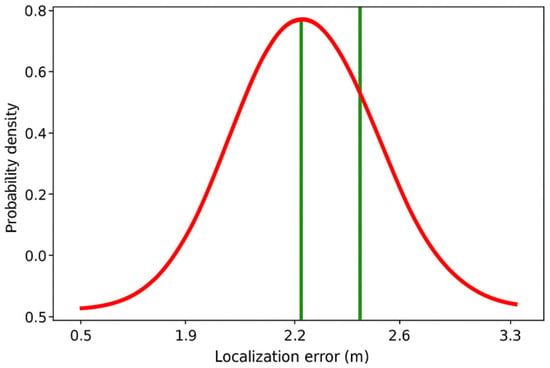

Next, the localization error for positioning the objects in the navigation area was also assessed. Hence, to construct a reliable semantic map, it is essential to accurately determine the positions of objects containing relevant information, enabling the robot to perform actions with precision. Based on the results obtained from multiple experimental trials, the average localization error was approximately 1.51 m, indicating a consistent level of positional accuracy across the evaluated scenarios, demonstrating that the developed system could effectively identify and localize target objects within an acceptable margin of error. Figure 14 illustrates the localization errors obtained for five object classes within the simulated environment. The standard deviation of the localization errors of detected objects within the simulated testbed environment is presented in Figure 15.

Figure 14.

Average localization error for five object classes in the simulated testbed.

Figure 15.

Standard deviation of the localization errors of detected objects within the simulated testbed environment. The green lines represent the acceptable localization error bounds around the mean error.

Finally, the accuracy of map production was evaluated. Hence, this paper first evaluated the effectiveness of the object detection model by analyzing its classification accuracy, which is the ratio of correctly detected objects. Next, the localization error was estimated by calculating the distance between the actual and predicted positions of each detected object using the Euclidean distance formula, as described earlier. Table 12 presents the semantic mapping results for the simulated desalination plant environment. As presented below, the average detection ratio of the existing objects is equal to 88.70% with an average mean LE of 1.51 m. In addition, the standard deviation values in Table 12 reflect the variability in localization error across object classes in the simulated desalination environment. As presented, the overall SD is 0.18 m demonstrating that the developed system maintains reliable localization performance across the simulated testbed.

Table 12.

The semantic mapping results for the simulated desalination environment.

The third component of this paper’s results involves assessing the efficiency of the developed semantic map using real experiment testbed, through analyzing three evaluation metrics: recognized object ratio, localization error, and the map construction accuracy. The real-world experiments conducted in the desalination plant environment yielded an average recognized object ratio of 81.25% as shown in Table 13, which presents a slight reduction compared to the simulated testbed. This performance gap can be attributed to two main factors: first, the robot platform was unable to fully detect horizontal and vertical pipes, as parts of them remained outside its field of view; and second, several areas of the testbed were unreachable due to physical obstacles. In addition, the uneven distribution of samples may introduce bias during training, as the model tends to learn majority classes more effectively than minority ones. This imbalance can negatively affect the model’s ability to generalize and may result in reduced classification accuracy for underrepresented classes.

Table 13.

Classification results of the YOLOv8 model in the real-world testbed.

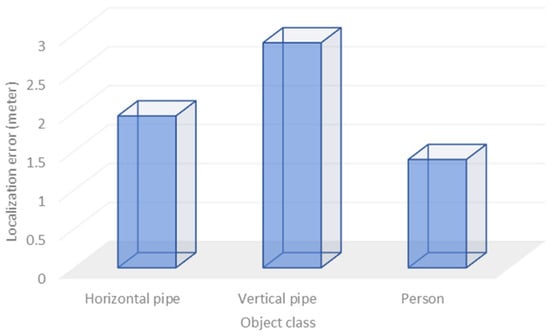

The development of an effective semantic map for desalination plants mostly depends on how accurately the system can position both horizontal and vertical pipes. To evaluate this capability, this paper considered the localization error for each detected object using Equation (2), with the outcomes illustrated in Figure 16. The analysis showed an average localization error of 2.07 m across three object categories: horizontal pipes, vertical pipes, and persons. Among them, the person class exhibited the highest accuracy, achieving the lowest localization error, followed by the horizontal pipes. However, the vertical pipes recorded the largest error, mainly because of their physical placement within the plant, which made it difficult for the robot to detect and localize them reliably. The standard deviation of the localization errors of detected objects within the real-world testbed environment is presented in Figure 17.

Figure 16.

Average localization error for three object classes in the real-world testbed.

Figure 17.

Standard deviation of the localization errors of detected objects within the teal-world testbed. The green lines represent the acceptable localization error bounds around the mean error.

The final evaluation metric pertains to the effectiveness of the semantic map generation process, which is primarily determined by the performance of the object detection model and the localization accuracy of the detected objects. Table 14 reports the overall outcomes obtained from the real-world testbed. The results indicate that the proposed semantic mapping framework achieved an object detection success rate of 81.25% and an average localization error of 2.07 m. These findings highlight the challenges of transferring from simulation to real-world conditions and suggest the need for enhanced perception capabilities and improved navigation strategies to increase detection accuracy and environmental coverage. Moreover, the standard deviation values indicate the variability in localization error for each object class in the real-world environment. Higher variation for horizontal pipes (0.36 m) reflects the impact of occlusions and structural complexity, while lower values for vertical pipes (0.24 m) and persons (0.06 m) demonstrate more consistent localization. However, the overall SD of 0.22 m proves that the system maintains stable performance across different object types.

Table 14.

The semantic mapping results for the real-world desalination plant environment.

5. Discussion

Robot semantic navigation has gained significant attention in recent years due to its increasing importance across various applications [40]. Autonomous inspection and monitoring of desalination plants are increasingly recognized as critical tasks for ensuring the continuous and efficient operation of these facilities. Hence, this paper presents a case study focused on a desalination plant, with the aim of developing an effective semantic mapping production approach to support autonomous and continuous inspection and monitoring.

Therefore, the system developed in this study relies on sensor fusion by integrating three perception subsystems to construct an efficient semantic map. The first one involves the employment of LiDAR technology for constructing the geometry map, whereas the second one adopts a depth-based vision system to recognize an object of interest and estimate the distance to the recognized object. Finally, the robot’s wheel odometry system is capable of estimating the traveled distance and hence calculate the robot’s 2D coordinates in the desalination plant environment. The integration of these three subsystems offers an efficient semantic map with rich information about the area of interest, which can assist in an autonomous remote monitoring and inspection. For instance, the developed semantic map construction system facilitates the detection of leaks in pipes by first recognizing these components and accurately localizing their coordinates.

Based on the available object detection datasets, there is no reliable vision dataset for desalination plants environments. Therefore, this work constructed a dataset tailored to the unique visual and structural characteristics of desalination plant environments that consists of the most popular objects in the desalination plant (vertical pipes, horizontal pipes, and pumps). In addition, this paper applied extensive data augmentation techniques for the purpose of enhancing its robustness and support deep learning applications. The YOLOv8 model was adopted to customize the system to be able to detect and recognize objects of interest in the desalination plant environment.

Therefore, this work provides significant contributions by addressing the need for customized object detection in industrial and public safety domains. It demonstrates how artificial intelligence can enhance operational efficiency and ensure safety, even when the available data are limited.

Moreover, this study investigated the performance of two different YOLO models (YOLOv5 and YOLOv8) to detect and recognize objects of interest in a desalination facility environment. Based on the obtained results, YOLOv8 achieved better object detection results in terms of precision, recall, classification accuracy, and mAP@0.5 scores, as presented in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Comparison of object detection efficiency between YOLOv5 and YOLOv8.

As presented earlier, the experimental results showed that YOLOv8 significantly outperforms YOLOv5 in terms of classification accuracy, precision, recall, and mAP@0.5. This improvement can be attributed to several factors. First, YOLOv8 presents architectural enhancements, including a more efficient backbone network and a decoupled detection head, which enhance feature representation and object localization accuracy. Second, YOLOv8 benefits from more advanced training strategies and data augmentation techniques, such as refined mosaic augmentation and anchor-free detection, which contribute to better generalization. Finally, the features of the desalination plant dataset itself, such as the presence of small, elongated pipe structures, low light, and visually cluttered backgrounds, further highlight YOLOv8’s robustness compared to YOLOv5. These elements collectively clarify the observed performance gap and validate the suitability of YOLOv8 for semantic mapping and pipe detection in desalination plant environments.

LiDAR data can be effectively employed to construct geometric maps due to its high-precision distance measurements and ability to capture structural details of the environment. However, relying solely on LiDAR data for semantic map construction is often ineffective, as it delivers partial information about object appearance, texture, and class-specific features. This limitation decreases the overall accuracy and richness of semantic maps, making it difficult to reliably discriminate between objects with similar geometric properties but different semantic meanings (e.g., pipes versus surrounding structural elements) [15,16,18,19,20]. Therefore, while LiDAR is well-suited for geometry-based mapping, additional sensing modalities such as RGB cameras, are essential to achieve accurate and meaningful semantic representations.

On the other hand, relying solely on RGB cameras [21,22,23,24,25] to construct semantic maps can deliver reasonable accuracy, mainly when combined with DL approaches that allow robust object detection and classification. RGB data offer rich visual information, including color, texture, and object-specific features, which are essential for distinguishing between different semantic classes. However, the absence of geometric information limits this method’s capacity to precisely estimate object dimensions, spatial relationships, and precise localization within the environment. As a result, the generated semantic map may contain detailed object-level information but will lack the structural and spatial context necessary for reliable navigation and inspection tasks.

Therefore, integrating RGB images and robot odometry with LiDAR data enables the construction of more efficient semantic maps, where objects can be correctly classified while preserving detailed geometric information. Moreover, the use of an RGB-D camera further enhances this process by delivering depth information alongside visual cues, which increases the precision of object localization. As a result, the combined sensing modalities yield highly accurate semantic maps that are both semantically rich and geometrically reliable.

According to the obtained results, the developed map construction system achieves efficient accuracy in map production by providing a reasonable classification accuracy and an efficient object localization accuracy. Hence, the developed system was able to classify most of the existing objects in the desalination plant environment with reasonable classification accuracy. In addition, the developed system offers a low localization error due to the employment of depth information that can be used to estimate the distance to an object. Therefore, the obtained map production system offers efficient map construction accuracy with rich semantic information.

6. Conclusions & Future Work

This paper designed and developed a real-time semantic map production system for indoor robot navigation. The developed system was validated through both simulated and real-world experiment testbeds. The developed system is based on the integration of a LiDAR unit, the vision subsystem, and a wheel odometry unit. The first was able to obtain a geometry map, whereas the vision subsystem was able to offer object detection with reasonable classification accuracy using the localization information obtained from the wheel odometry unit. For evaluation purposes, this paper assessed the efficiency of the developed system by considering four evaluation metrics. The obtained findings demonstrate that the developed framework is capable of producing reliable semantic maps with reasonably classification accuracy, although further improvements in localization precision would enhance its overall effectiveness in complex environments. Future work should aim to collect a more efficient dataset for desalination plant environment in order to allow for better object classification and hence offer better map production accuracy. Moreover, future studies may focus on integrating additional lightweight detectors to further improve robustness and generalization.

Author Contributions

H.A., L.D., A.B. and A.A.-Q. surveyed the relevant recently developed systems in the field. A.A., R.A. and T.A. designed and developed the robot semantic navigation system. L.D. and H.A. designed the simulation environment, and H.A. and T.A. performed several real experiments and discussed the obtained results. All authors actively participated in drafting and reviewing the entire manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This brochure article is derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA)-Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—with grant number 13010-Tabuk-2023-UT-R-3-1-SE.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the findings of this study has been made publicly available on Kaggle and can be accessed at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/tareqalhmiedat/water-pipes-dataset accessed on 10 October 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liang, C.J.; Cheng, M.H. Trends in robotics research in occupational safety and health: A scientometric analysis and review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.K.; Song, W.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J. Usability test of KNRC self-feeding robot. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 13th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR), Seattle, WA, USA, 24–26 June 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bemelmans, R.; Gelderblom, G.J.; Jonker, P.; de Witte, L. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: A systematic review into effects and electiveness. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Shiomi, M.; Miyashita, Z.; Ishiguro, H.; Hagita, N. An active guide robot in a shopping mall. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, HRI’09, La Jolla, CA, USA, 11–13 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, R.; Willms, I. A mobile security robot equipped with UWB-radar for super-resolution indoor positioning and localisation applications. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, IPIN 2012—Conference Proceedings, Sydney, Australia, 13–15 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, S.; Sünderhauf, N.; Newman, P.; Leonard, J.J.; Cox, D.; Corke, P.; Milford, M.J. Visual place recognition: A survey. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterovitz, R.; Koenig, S.; Likhachev, M. Robot planning in the real world: Research challenges and opportunities. AI Mag. 2016, 37, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Gueaieb, W. A state-of-the-art review on topology and differential geometry-based robotic path planning—Part I: Planning under static constraints. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2024, 8, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, S.D.; Andersen, H.; Du, X.; Shen, X.; Meghjani, M.; Eng, Y.H.; Rus, D.; Ang, M.H. Perception, planning, control, and coordination for autonomous vehicles. Machines 2017, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea, C.; Kern, J. Recent Advances and Challenges in Industrial Robotics: A Systematic Review of Technological Trends and Emerging Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczna-Fuławka, M.; Koval, A.; Nikolakopoulos, G.; Fumagalli, M.; Santas Moreu, L.; Vigara-Puche, V.; Müller, J.; Prenner, M. Autonomous mobile inspection robots in deep underground mining—The current state of the art and future perspectives. Sensors 2025, 25, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretschneider, L.; Bollmann, S.; Houssin-Agbomson, D.; Shaw, J.; Howes, N.; Nguyen, L.; Robinson, R.; Helmore, J.; Lichtenstern, M.; Nwaboh, J.; et al. Concepts for drone based pipeline leak detection. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11, 1426206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Cao, S.; Rao, F.; Fu, Q.; Leng, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, X. Research and experiment of a novel leak detection robot. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2025, 52, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqobali, R.; Alshmrani, M.; Alnasser, R.; Rashidi, A.; Alhmiedat, T.; Alia, O.M.D. A survey on robot semantic navigation systems for indoor environments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, C.; Chasmer, L.; Gynan, C.; Mahoney, C.; Sitar, M. Multisensor and multispectral lidar characterization and classification of a forest environment. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 42, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, M.W.; Nishihata, T.; Brooks, C.A.; Iagnemma, K. Ground plane identification using LIDAR in forested environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 3831–3836. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N.; Yang, E.; Corney, J.; Chen, Y. Semantic path planning for indoor navigation and household tasks. In Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems: 20th Annual Conference, TAROS 2019, London, UK, 3–5 July 2019, Proceedings, Part II 20; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Aparicio, C.; Guerrero-Higueras, A.M.; Rodríguez-Lera, F.J.; Ginés Clavero, J.; Martín Rico, F.; Matellán, V. People detection and tracking using LIDAR sensors. Robotics 2019, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, A.; Oliveira, G.L.; Burgard, W. Deep semantic classification for 3d lidar data. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; pp. 3544–3549. [Google Scholar]

- Alenzi, Z.; Alenzi, E.; Alqasir, M.; Alruwaili, M.; Alhmiedat, T.; Alia, O.M.D. A Semantic Classification Approach for Indoor Robot Navigation. Electronics 2022, 11, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.H.; Manzoor, S.; Rocha, Y.G.; Bae, S.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kuc, T.Y.; Kim, M. Autonomous navigation framework for intelligent robots based on a semantic environment modeling. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Qi, X.; Liao, Z. Social and robust navigation for indoor robots based on object semantic grid and topological map. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Bhowmick, B.; Roychoudhury, R.D. Object goal navigation based on semantics and rgb ego view. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.11543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wang, W.; Yuan, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Xue, L.; Sun, Y. Building semantic grid maps for domestic robot navigation. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17, 1729881419900066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Yang, T.; Liu, C. A Semantic Information-Based Optimized vSLAM in Indoor Dynamic Environments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Song, W.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Y. Indoor semantic map building for robot navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 8th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC), Chongqing, China, 24–26 May 2019; pp. 794–798. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, J.; Barber, R.; Mozos, O.M. Relational model for robotic semantic navigation in indoor environments. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 86, 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zuo, T.; Hu, X. OFM-SLAM: A visual semantic SLAM for dynamic indoor environments. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5538840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, S.; Maurin, A.L.; Andersen, J.C. Semantic mapping and object detection for indoor mobile robots. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 517, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Seok, J. Indoor semantic segmentation for robot navigating on mobile. In Proceedings of the 2018 Tenth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Prague, Czech Republic, 3–6 July 2018; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, T.V.; Bui, N.T. Multi-scale fully convolutional network-based semantic segmentation for mobile robot navigation. Electronics 2023, 12, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Huang, K.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, C.; Guo, R.; Zhang, H. Semantic RGB-D SLAM for rescue robot navigation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 221320–221329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Deng, Z.; Sun, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J. An object slam framework for association, mapping, and high-level tasks. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 2912–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollo, F.; Raiola, G.; Zunino, A.; Tsagarakis, N.; Ajoudani, A. Artifacts mapping: Multi-modal semantic mapping for object detection and 3d localization. In Proceedings of the 2023 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR), Coimbra, Portugal, 4–7 September 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiao, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, R. Semi-Autonomous Navigation Based on Local Semantic Map for Mobile Robot. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. Sci. 2025, 30, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, D.; Chang, Y.; Hughes, N.; Trang, M.; Griffith, D.; Dougherty, C.; Cristofalo, E.; Schmid, L.; Carlone, L. Clio: Real-time task-driven open-set 3d scene graphs. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 8921–8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, J.M.; Evans, M.H.; Worley, R.; Edwards, S.; Zhang, R.; Dodd, T.; Mihaylova, L.; Anderson, S.R. Simultaneous localization and mapping for inspection robots in water and sewer pipe networks: A review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 140173–140198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.; Alatawi, H.; Binnouh, A.; Duwayriat, L.; Alhmiedat, T.; Alia, O.M.D. Deep Learning-Based Vision Systems for Robot Semantic Navigation: An Experimental Study. Technologies 2024, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqobali, R.; Alnasser, R.; Rashidi, A.; Alshmrani, M.; Alhmiedat, T. A Real-Time Semantic Map Production System for Indoor Robot Navigation. Sensors 2024, 24, 6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmiedat, T.; Alia, O.M.D. Utilizing a deep neural network for robot semantic classification in indoor environments. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).