Abstract

The construction of a high-order shape function is a key and difficulty for unstructured grid mesh and sliding boundary problems. In this paper, a construction method of space-time absolute nodal coordinate formulation quadrilateral cable (SACQ) is proposed, and the accuracy of the SACQ element is studied and verified with three different applications. First, the shape function of SACQ is constructed with spatiotemporal reduction coordinates, and the action integral of SACQ is composed with the Lagrangian function and discrete with perspective transformation. Second, the numerical convergence region is discussed and determined with the Courant number. Furthermore, a space-time nodal dislocation and its relation with the Courant number are studied. The simulation and verification are focusing on some realistic problems. Finally, a one-sided impact, a free-flexible pendulum, a taut string with a sliding boundary and a deployable guyed mast under an impact transverse wave are simulated. In these problems, an unstructured grid meshed with SACQ has similar energy convergence and accuracy to a structured grid but shows better efficiency.

1. Introduction

The dynamic system composed of flexible cable components is a common type of nonlinear dynamic system of flexible bodies, which has a wide range of applications in aerospace [1,2,3], communication [4] and transmission lines [5]. The nonlinear dynamic phenomena exhibited by flexible cable components, especially in high-rise structures, may cause severe issues in current research [6]. The dynamic systems composed of flexible body components usually have geometric nonlinearity, and for flexible body components made of special materials, they also have material nonlinearity characteristics [7,8]. This makes the dynamic characteristics of flexible bodies complex and usually makes it difficult to obtain analytical results. Therefore, simulating the involved flexible bodies can reduce design costs and detect design defects as early as possible.

The dynamic simulation of flexible cable components often uses the finite element method (FEM) to spatially discretize their dynamic equations. In the finite element discretization format, absolute nodal coordinate formulation (ANCF) is an effective method of describing large displacement [9], large deformation [10,11], and large rotation of flexible bodies by introducing gradients [12]. Different deformation assumptions can be used to distinguish the types of ANCF beams. The ANCF-cable element uses the Euler–Bernoulli beam assumption, while the ANCF-beam element uses the Green-Lagrange strain tensor to describe the displacement field of the element. Since the cable element only considers motion on the axis, it can describe axial deformation and bending deformation and has good solution efficiency. The beam element allows the element to describe torsion and shear problems [13]. The cable element was first proposed by Gerstmayr [14], which abstracts the beam as a curve and determines the displacement field function of the beam through the material coordinates of the curve and its corresponding curvature. Cable elements have undergone several modifications to produce some variant elements, but these elements are also collectively referred to as cable elements. Gerstmayr and Sugiyama corrected its curvature term [15] to improve its ability to describe bending deformation; Zhang improved the simple stress continuity of the element by increasing the order of generalized coordinate derivatives along the axis [16].

In dynamic discrete formulation, ANCF usually appears as a spatial discrete formulation, and differential methods are often used in the time direction, such as the generalized method or a semi-implicit method [17]. Since the discrete methods used in the time direction and the spatial direction are inconsistent, these methods are collectively referred to as semi-spacetime finite element methods. Differential methods focus on the system characteristics of each time frame. Using finite element discretization both in time and space directions can focus on changes in system characteristics between two time frames [18]. This makes it advantageous in describing slip problems of spatiotemporal grids, local grid densification problems, and nonlinear materials. Research on the space-time finite element method (ST-FEM) mainly includes research on discrete methods and function construction. Early ST-FEM used Galerkin discretization uniformly in the spacetime direction to solve heat conduction equations [19] and dynamic equations [20]. With the development of Hamiltonian mechanics and differential geometry, spacetime discrete formats based on Hamiltonian laws [21] have been proposed due to their excellent energy conservation properties. Furthermore, Gao [22,23,24], Mergel [25], Sanchez [26], etc., introduced the Hamiltonian law of varying action to introduce non-conservative forces into natural variation methods to improve the universality of spacetime finite elements. In terms of function research, low-order spacetime functions were also proposed with the proposal of ST-FEM. Bajer developed spacetime triangles and tetrahedrons [27], which can describe time-varying boundaries and space-time asynchronous solutions through spacetime unstructured grids [28,29]. Recently, Dumont et al. proposed a three-dimensional tetrahedron that can be used to construct spacetime grid redivision processes [30], and Langer et al. also proposed an optimized method for hyperbolic equations using unstructured spacetime finite elements [31].

Usually, the dynamic solution of ANCF can be described as a spatiotemporal dynamic problem by considering the velocity in the displacement field as a time gradient. The main difficulty in considering gradients in space and time direction is how to construct high-order space-time functions. Chen et al. [32] proposed a method of constructing Lagrange family high-order space-time element functions using the direct product method and discretizing dynamics based on Hamiltonian varying action law. High-order space-time elements constructed by the direct product method can only use structured grids in the time direction, which makes it difficult for time finite elements to solve the problem of spatiotemporal grid slip and local densification. Therefore, this requires a new way to construct high-order space-time shape functions, which is one of the focal points of this paper.

This paper proposes a method of constructing high-order space-time functions based on the inverse method and applies it to the establishment process of space-time quadrilateral elements, which can be meshed with an unstructured grid (UG) for space-time asynchronous solutions and time-varying boundaries. The specific implementation of the inverse method is proposed in Section 2 for constructing the shape function of SACQ. In Section 3, the integration method of space-time quadrilateral elements is given. The influence of nodal dislocation accuracy on structural response is studied in Section 4. In Section 5, different practical examples are used to demonstrate its response under variable stiffness and the flexible model, the slip boundary example, and the response of the mast tower frame in large-scale space deployment with the basic vibration process.

2. The Shape Function of Space-Time ANCF Quadrilateral Cable Element

Basically, space-time ANCF cable elements have a definitive manner of construction by establishing a shape function and setting nodal general coordinates to construct a displacement field. Then we construct the velocity field of the beam based on the displacement field and establish the strain distribution law of the beam element using the Euler–Bernoulli equation or the Timoshenko equation. The key problem for establishing a space-time ANCF quadrilateral (SACQ) cable element is the shape function construction.

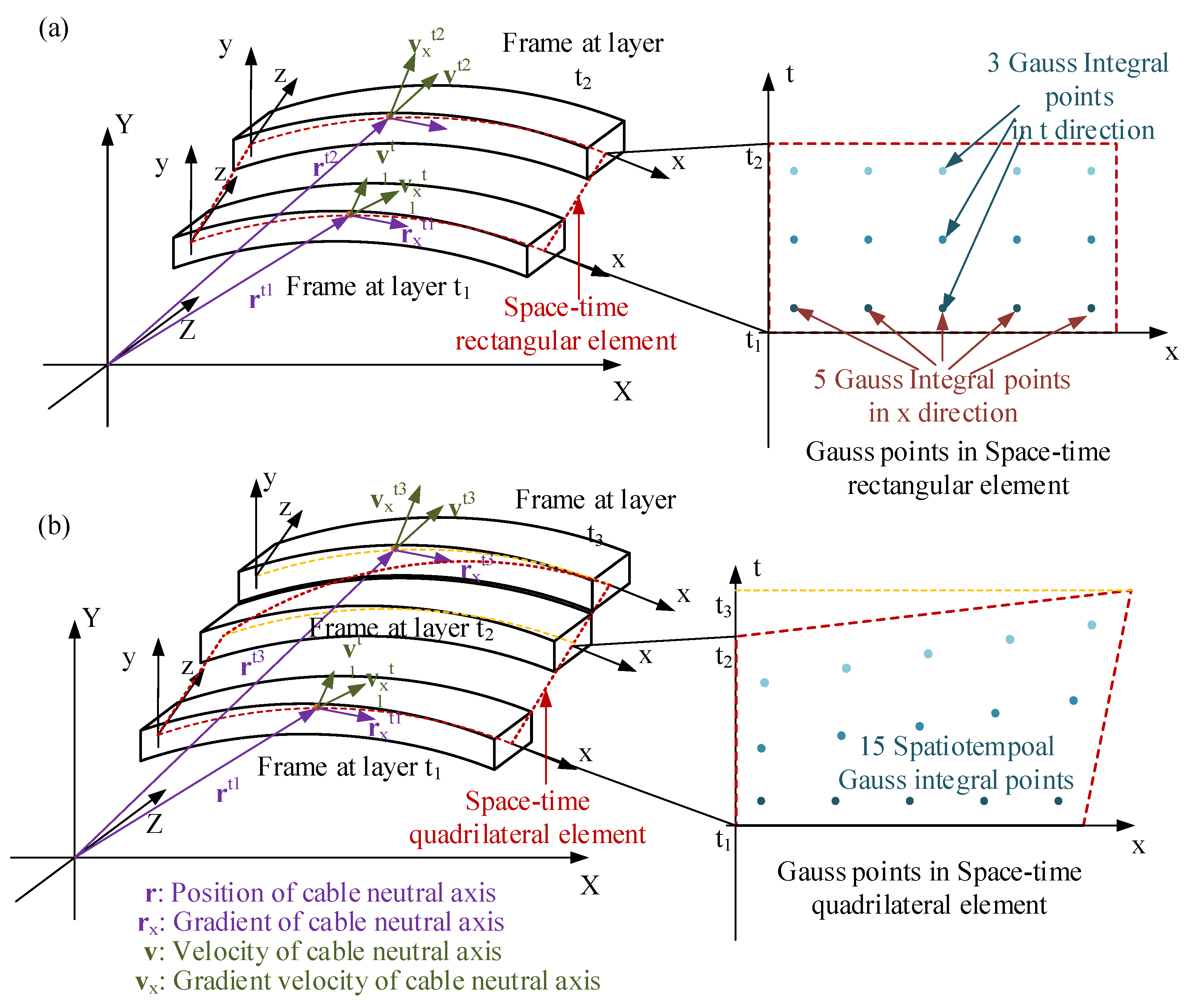

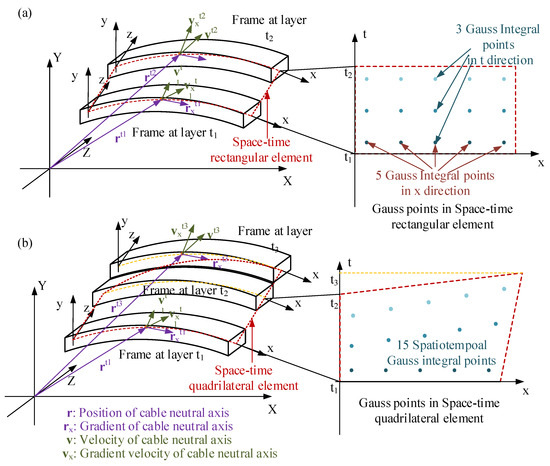

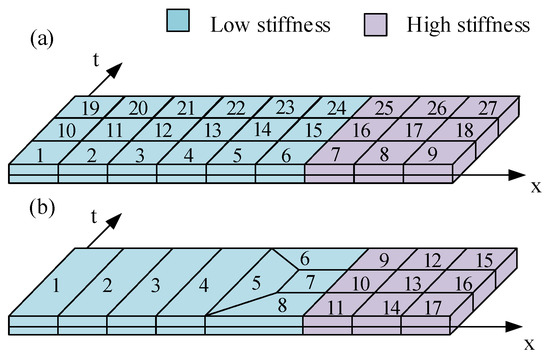

There are two typical methods for element construction. First, the Lagrangian method, in which the shape function is based on the direct product of spatial and temporal Hermite interpolation functions. The advantage of the Lagrangian method is that the original ANCF cable (OAC) element can be transformed into an SAC element easily just by direct product with a temporal function. With this method, the perspective of the SAC element has four spatiotemporal nodes on two different time layers and forms into a rectangle as shown in Figure 1a. The major limitation of the SAC element is it can only be used in structured grid mesh and leads to its limitation in usage scenarios when an asynchronous solution or grid sliding is needed.

Figure 1.

The comparison between the SAC element and the SACQ element. (a) The spatiotemporal frame and the Gauss points distribution of SAC element. (b) The spatiotemporal frame and the Gauss points distribution of SACQ element.

Second, the inverse method, which establishes a Lagrangian basis using Pascal’s triangle, then constructs the functional by performing inversions at specified nodes. This method enables the creation of elements suitable for unstructured grids to address the aforementioned issues of asynchronous solutions or grid sliding. This approach enables the establishment of SACQ element. The structure of SACQ is shown in Figure 1b. It consists of three time layers (–), where there are two nodes at the time layer and only one node at the and layers. The material coordinate length of the layer is changed from the layer to the layer and finally reduces the material coordinate length to 0. The SACQ element means that the topology of the SAC element can be changed, and the arrangement of integral points in the element has changed from the regular arrangement along the material and time coordinates to the non-uniform arrangement in space-time.

The shape function of SACQ is constructed via base function by Equation (1)

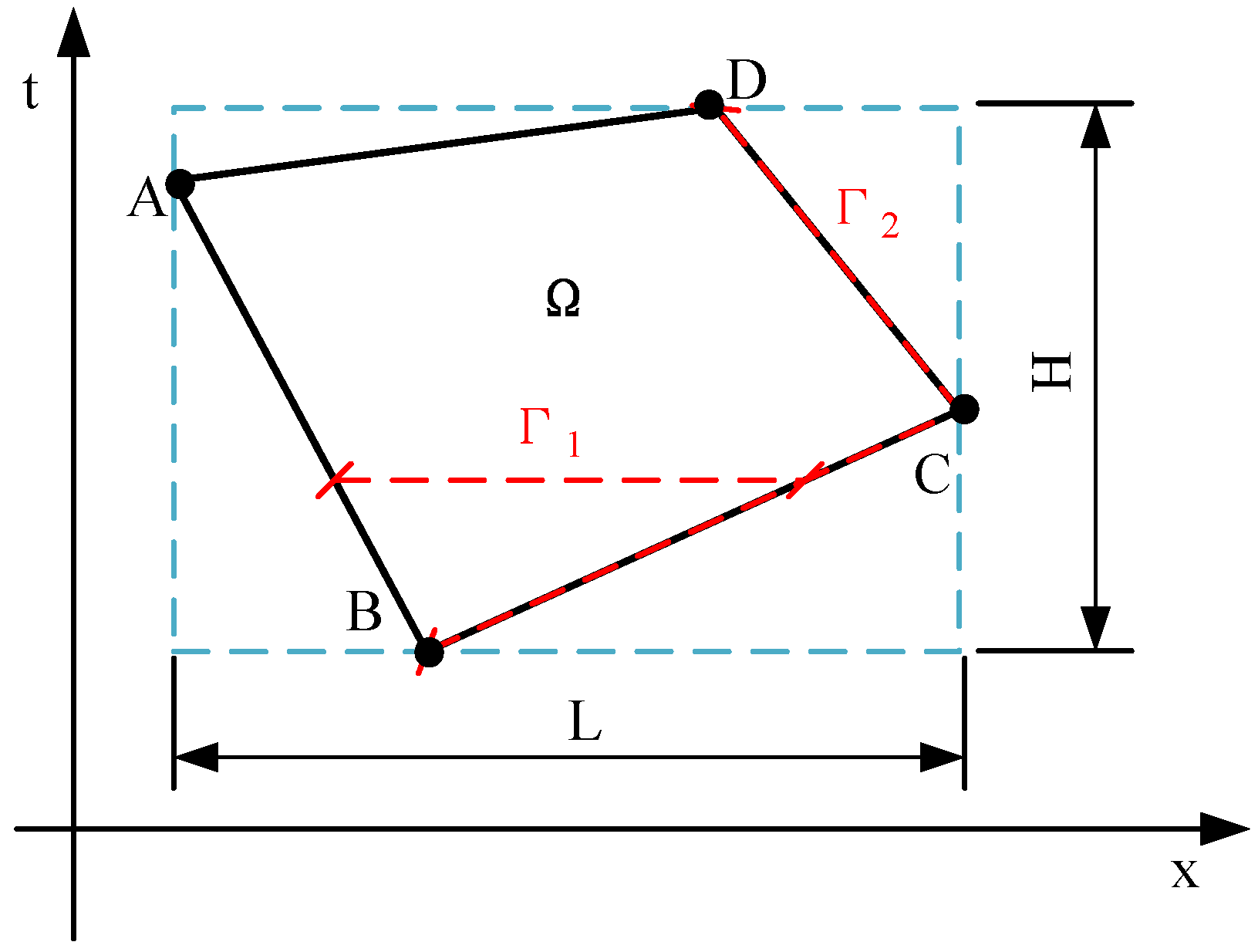

Because the space-time quadrilateral has a difference between the two directional scales, it is necessary to reduce the material coordinates x and time t into reduction coordinate and .

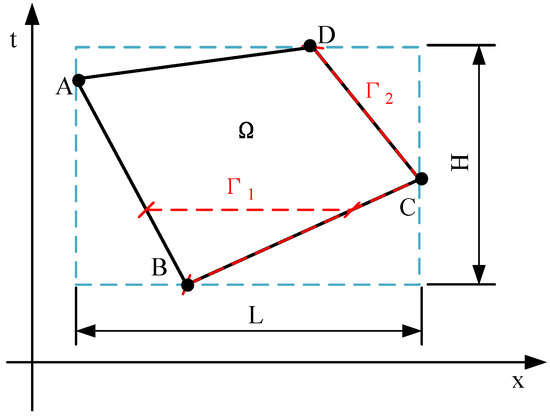

As shown in Figure 2, a convex quadrilateral ABCD is inscribed in a rectangle with a spatial length of L and a time length of H. The reduction coordinate of ABCD is normalized to its outer rectangle without changing its shape. The global node is compressed into the variable shown in Equation (2)

Figure 2.

The spatiotemporal quadrilateral and its external connection rectangular.

The advantage of this reduction coordinate is that the reduced coordinates correspond to the material coordinates, respectively. The disadvantage of using this reduction method is that the shape function constructed by this method cannot be expressed explicitly.

Row vector is the base function shown in Equation (3)

Because the selection of the base significantly impacts the continuity between elements, for the SACQ element, continuity must be maintained with other elements along each edge to ensure continuity of the velocity field, where it is the Lagrangian family base function according to the Pascal triangle. The base function has 16 components. For establishing the three-dimensional SACQ element, it needs 4 nodes and 48 generalized coordinates, including the position vector and velocity vector.

The matrix A in Equation (1) can be written as in Equation (4)

Matrix A is a nodal vector consisting of the derivatives of the base function matrix at four nodes, and subscript i represents the four nodes numbered 1–4. Since the element is not an isoparametric element, this reduction avoids the problem in mixed derivatives. The relationship between the derivatives of the derivative shape function in reduced coordinates is given by the chain derivation rule in Equation (5)

In practice, it is found that the shape function constructed by this method requires that its two diagonals should not be parallel to the x-axis and t-axis at the same time, which causes singularity in matrix .

The interpolation of the element on the boundary is determined only by the corresponding degrees of freedom (DOFs) and their velocities of the nodes on the boundary, which shows that the element is a non-isoparametric space-time conforming element. Because the cubic interpolation is used in both directions, the continuity of the element both in the spatiotemporal direction and the continuity of the stress are ensured.

3. The Hamiltonian Varying Action and Energy Integral of SACQ

Similarly to the SAC element, the SACQ element uses the Hamiltonian law of varying action to construct the dynamic function. The element action is given in Equation (6), which is the time integral of the Lagrangian function ,

ANCF cable elements obey the Euler–Bernoulli assumption. So, the Lagrangian function consists of three parts: kinetic energy ,

where is the element linear density, is the element velocity; elastic potential energy ,

where E is the Young’s modulus, A is the sectional area, J is the polar moment of inertia, is the strain of the centerline, and is the curvature radius of the centerline. The work generated by external forces, which can be further divided into the work of volume force ,

and the work of surface force ,

where is the volume force, and is the surface force.

The integral of action usually uses a numerical integration algorithm because of its nonlinearity. The kinetic energy, potential energy, volume, and nodal forces work have the same Equations (7)–(10) between SAC and SACQ. The integration intervals and the algorithm are the major differences between the SAC element and the SACQ element.

The SACQ element includes three different numerical integration intervals. As Figure 2 indicates, the first is the element’s space-time integration, which describes the integration of kinetic energy, potential energy and volume force and some parameters in Lagrangian formulation. The integral interval of this type is the entire quadrilateral region . The second integral of intervals, the path, is only in the direction of space. This kind of integration interval is usually used to calculate the element’s mass matrix of a certain time layer. The third type of interval is the integration along the space-time boundary of the element as shown in the path. This type of integration is usually used to calculate the work performed by the nodal force in a certain period of time.

First, the interval , which is the only space-time surface integration interval, is discussed. Gauss integrals are achieved by placing Gauss points in each direction of the rectangle and integrating it using Equation (11)

where is the Jacobian matrix of the mapping between the quadrilateral domain and the rectangular domain.

The integration accuracy is associated with the location of Gauss points. The arrangement of Gauss integration points that achieves the highest integration accuracy depends on the rectangular layout scheme. Thus, the transformation between the spatiotemporal quadrilateral domain and the reduction rectangle domain is realized by the perspective transformation in Equation (12)

In this equation, and are rectangular coordinates, while and are the physical and time coordinates of the quadrilateral domain. The transformation coefficient of is usually set to 1, and the other transformation coefficients can be solved by Equation (13)

and the Jacobian matrix by Equation (14)

The subscript in the formula represents the node number of the corresponding quadrilateral.

Second is the mass matrix integration of the entry time and the exit time required by the solver. The integration interval is only in the direction of length but not in the direction of time. It is consistent with the mass matrix integral scheme of OAC without considering the change in element size. Only the coordinates of the end points of the elements under the time slice are required in the integration region to generate the integration and assembly schemes.

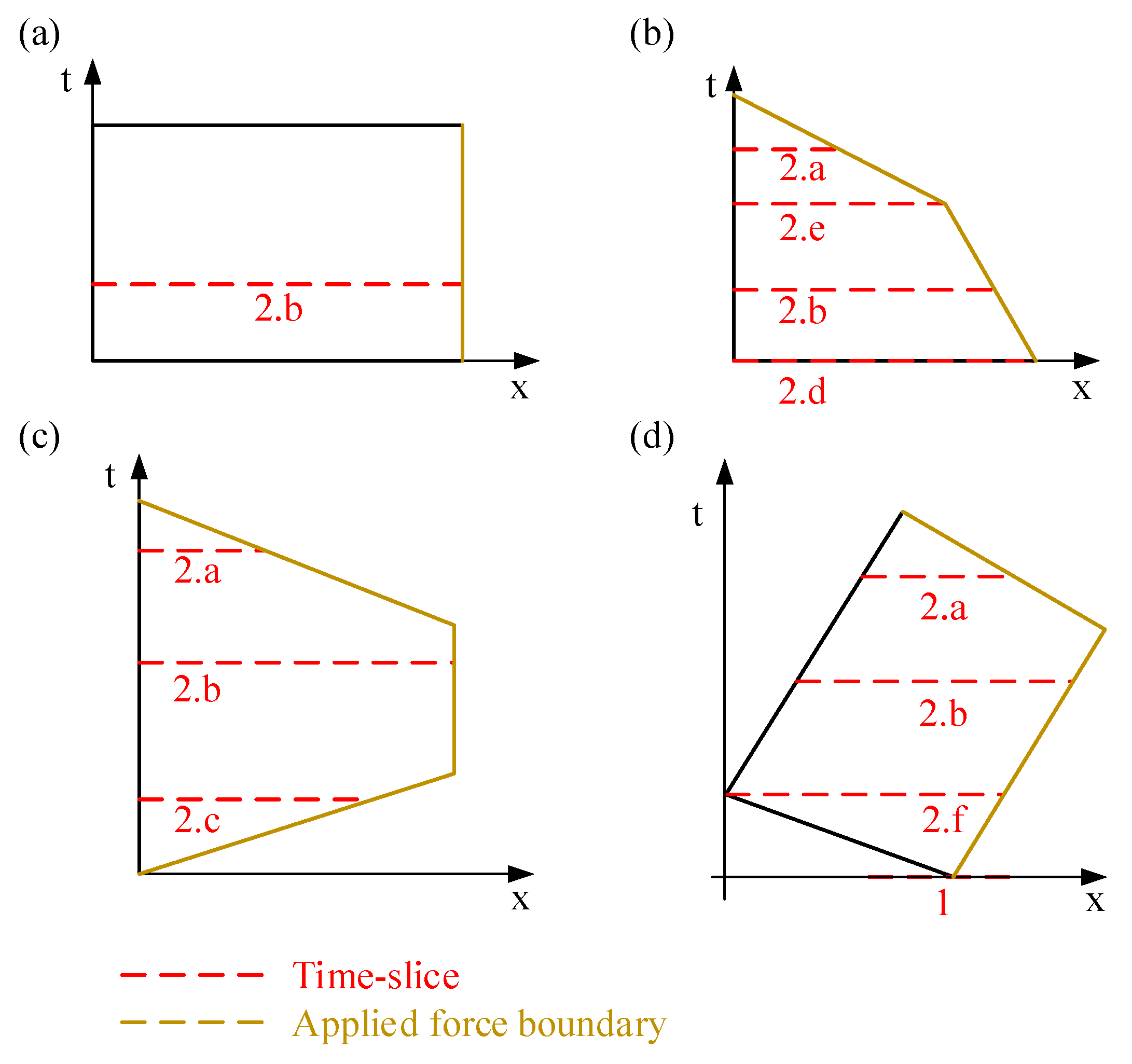

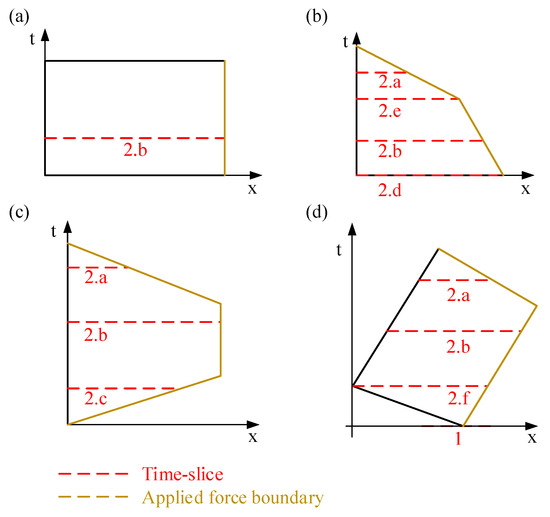

Normally, there are four spatiotemporal nodal distributions. The time slice of each quadrilateral is shown in Figure 3. The mass matrix of the spatiotemporal quadrilateral is defined in each time slice as a spatial concept. The definition of SACQ is the spatial ANCF cable mass matrix of spatiotemporal boundary points. One time slice has the following two major boundary point possibilities:

Figure 3.

The time slice and the applied force boundary of 4 different types of SACQ element. (a) Rectangular. (b) Single hypotenuse with a right angle. (c) Triple hypotenuse without a right angle. (d) Quadruple hypotenuse without right angle.

- There is only one boundary point on the time slice. This boundary point must be the node of SACQ at this time. On this time slice, the length of the spatial ANCF cable element is 0. So, the mass matrix of this time slice does not exist.

- Two boundary points are on the time slice. Under this circumstance, the boundary points can be calculated as follows:

- (a)

- The relative time of node A is higher than the time slice. On the contrary, nodes B, C, and D are lower than the time slice. The spatiotemporal boundaries are the AB line and the AD line.

- (b)

- The relative times of nodes A and B are higher than the time slice. Nodes C and D are lower than the time slice. The spatiotemporal boundaries are the BC line and the AD line.

- (c)

- The relative time of nodes A to C is higher than the time slice. Node D is lower than the time slice. The spatiotemporal boundaries are the BC line and the AD line.

- (d)

- Node A and node B are located on the time slice; both two nodes are boundary points.

- (e)

- Node A is on the time slice. Node B is higher than the time slice. Nodes C and D are lower than the time slice. A is the boundary point, and the BC line is the spatiotemporal boundary.

- (f)

- Node A is on the time slice. Nodes B and C are higher than the time slice. Node D is lower than the time slice. A is the boundary point, and the CD line is the spatiotemporal boundary.

If a spatiotemporal boundary is mentioned in any occasion above, the boundary point is calculated with the spatiotemporal boundary function at the time of the time slice. After two boundary nodes are determined, the mass matrix can be calculated with the Gauss numerical integration Equation (15)

where and are the left and right boundary points.

With the judgment method above, the time slice can be given at a random time. However, if the time slice is only calculated at the input/output time, the mass matrix can be degenerated with only occasion 1 and occasion 2e.

The third is the integration region for the nodal force or surface force integration, which depends on the space-time boundary of the element. If the boundary is parallel to the axis of time, its integral is only in the direction of time. If the boundary exists on both the time and space axes, the boundary is integrated along the boundary in both the time and space directions. As for the force at the boundary of the spatiotemporal boundary, the force vector should be integrated at the boundary. The number of spatiotemporal boundaries with external nodal force is from 1 to 3. Segmental integration should be used when the boundary number is more than 1.

The assembly and constrained variation scheme of SACQ is shown in Equation (16)

where is the global generalized coordinate, with Lagrange multipliers , is the initial value of the global generalized coordinate, is the derivation of element action with respect to , and are restrictions constructed by the Lagrange multiplier method.

A discrete scheme of Equation (16) can be derived with the p2 method [25]. It includes three parts, which are called the major solution part per Equation (17)

the replaceable constraint (RC) part per Equation (18)

and the supplementary constraint (SC) part per Equation (19)

The major solution part and the RC part are strictly needed in a solution process. The initial conditions are usually applied to the discrete scheme with the RC part, and the boundary conditions are applied with the SC part, but there is no clear boundary between the RC part and the SC part. In some specific conditions, the two parts can convert to each other.

Different from semi space-time discretization, there is a strong nonlinear relationship between the time of import and the time of export (corresponding to the calculation step size of the iterative method). The forward iterative algorithm cannot be constructed but can be replaced with the Newton–Raphson method to solve the equation. The Newton–Raphson iteration is shown in Equation (20)

where is the iteration of unknown vector , whose initial vector is . The vector is the dynamic equation is composed by Equations (17)∼(19); and the matrix is the Jacobian matrix of the equation .

In this section, a non-isoparametric coordinated SACQ element is established, and a method of establishing a non-isoparametric SACQ shape function is proposed. The correlation between the area integral in the discrete numerical integration and the Gauss quadrature method along the two lines is also explained. The consistency of the SACQ element and the SAC element in discrete format, assembly format, and solver is also pointed out.

4. The Solution Stability of SACQ Element

In this section, the deviation of energy calculation and the problem of stability under different space-time meshes are discussed. The stability and convergence regions of some space-time finite element methods are studied. When the Hamiltonian varying action is used, the accuracy and stability of the solution are directly related to the space-time dimension of the element. Stability is an important problem in SACQ, especially in the case of mesh slide problems.

A dimensionless method should be put forward to eliminate the influence of element size and material characteristics before the stability is studied. The discrete Equation (17) of the SACQ element can be written as the discrete format of Equation (21)

The bending process in this scheme gives the velocity of the transverse wave of the rod (transverse is used here because the shear wave is a diffuse bending wave). The tension-compression process gives the longitudinal wave velocity of the rod, which represents the maximum phase velocity. The shear wave velocity of the bar is usually lower than that of the longitudinal wave under the assumption of a slender beam. By studying the relation of reduced coordinates, the actual influence of L and H on the stability of the solution is judged, and the normalized parameters are determined as shown in Equation (22)

where E is Young’s modulus and is density in Equation (22); H is the calculated step size of the element; L is the length of the element, which, together with the wave velocity, establishes the Courant number . Both of them can calculate the velocity of the longitudinal wave in the bar.

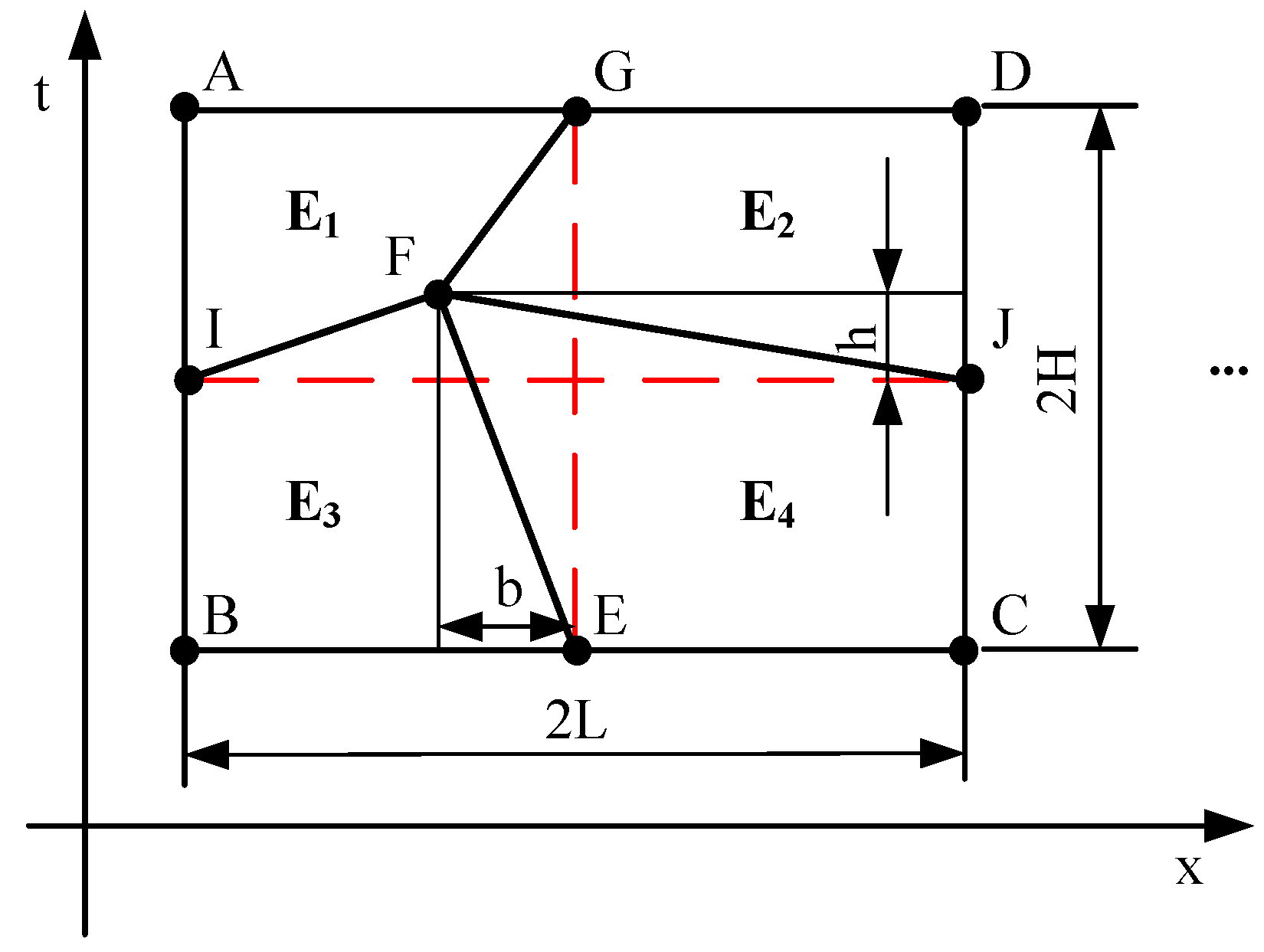

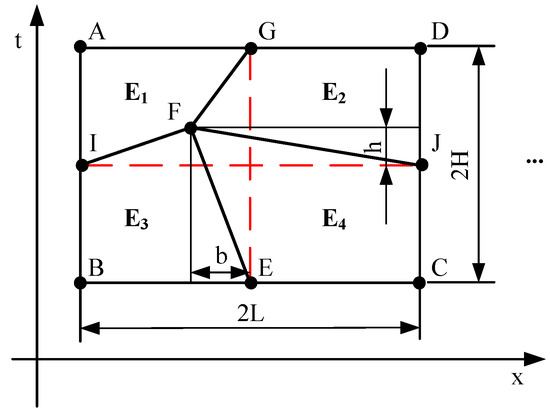

As shown in Figure 4, letter A to G is nodal codename. Node F is the dislocation node. to are 4 elements. h and b represent dislocation in the element length direction and time direction, respectively. The length-and time-oriented dislocation has some influence on the convergence. In this section, we mainly study the influence of two offsets and on the element convergence under the condition that Courant number is determined. In the paper of Bajer [28], the convergence of convex quadrilateral elements under analytic schemes is discussed. The Courant number serves as a reduction condition for wave velocity and the size of the spatiotemporal grid. It is typically used to limit the time step size, ensuring that the ratio of element length to width remains below the product of wave velocity and the Courant number to guarantee computational stability. When the Courant number is larger, it means that longer time steps can be used with the same spatial grid partitioning scheme.

Figure 4.

The structured and unstructured mesh grid of test elements.

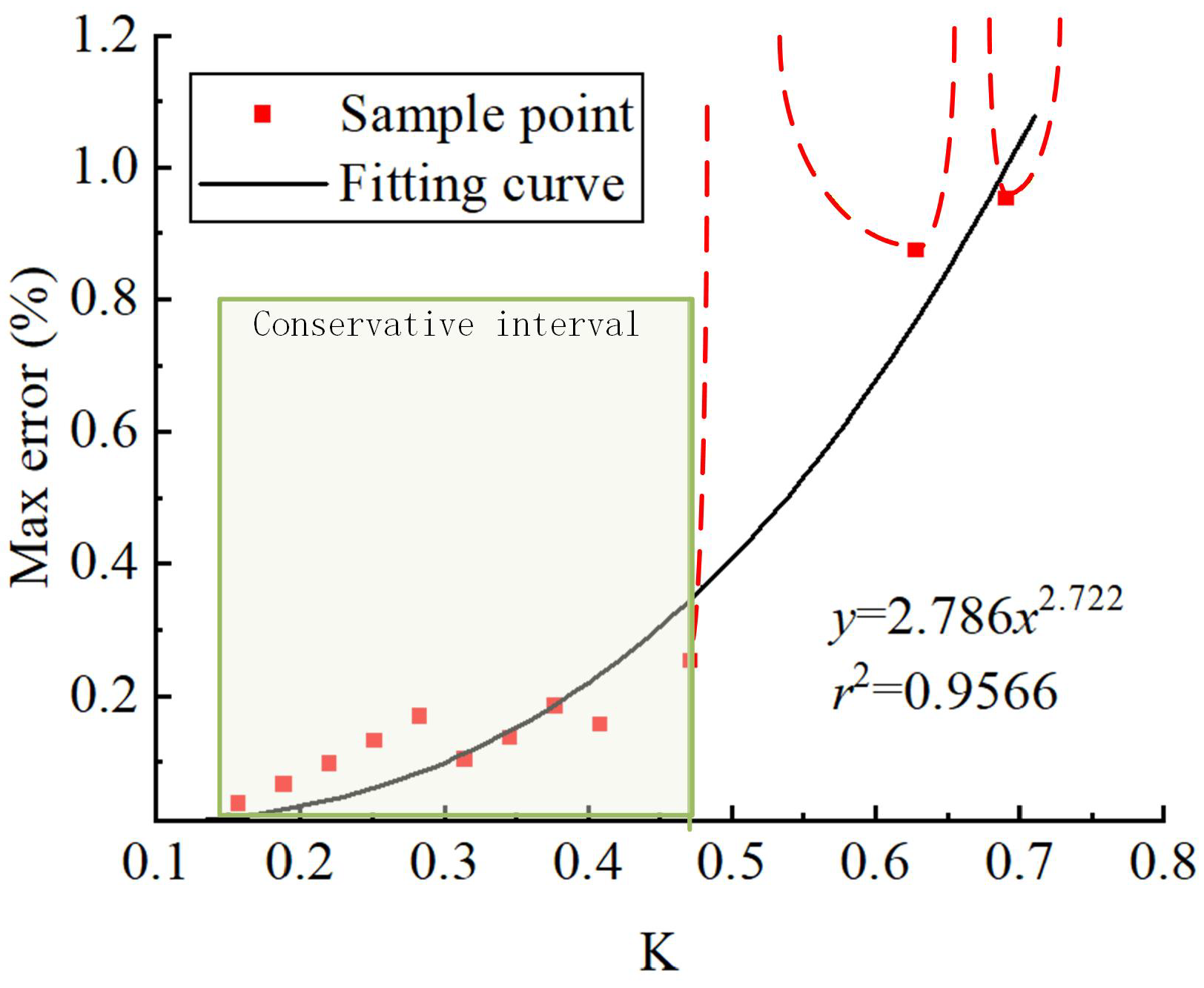

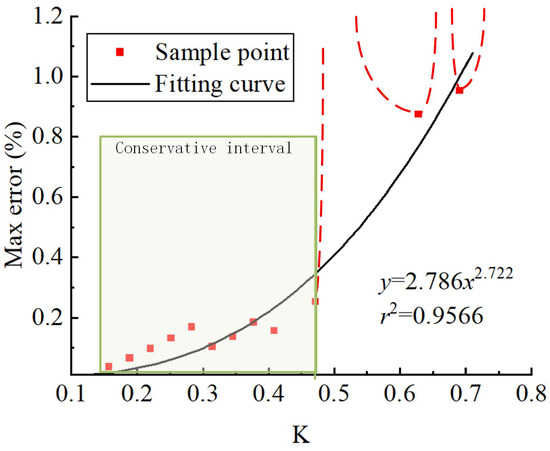

Because the solver does not satisfy the iterative scheme and the high nonlinearity of the SACQ element in the process of strain calculation, it is difficult to solve the analytic scheme; the influence of these variables can only be studied by numerical methods. The influence of Courant number on the stability of the solution on a straight grid is studied with a single-sided impact problem by evaluating its energy conservation properties. There is no nodal dislocation in this simulation, and the Courant number is varied by adjusting the time step. The simulation conditions are as follows: Young’s modulus E = 3.4 GPa, density kg/, and the longitudinal wave velocity can be calculated as 1570 m/s. The grid is like Figure 4, whose length is L = 0.5 m per element. At the starting point, is set as 0.1256. The reason for choosing this point as the starting point is that too short a step length will lead to the morbid condition of the potential energy matrix. At 0.02 s, the ratio of the maximum energy error to the initial energy is 0.003%. From K = 0.1256 to K = 0.758, energy deviation at 0.02 s was calculated at 20 sample points, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The relationship between the Courant number K and energy deviation.

Calculations reveal that the energy at the sample point exhibits significant dispersion. The maximum percentage of energy error ranges from 0.06% to 1.99 %, which implies that there exists one or some non-convergent segments. The red dashed line in Figure 5 illustrates the trend of energy error exceeding 1.2% at the sample point. The major conservation interval of K is 0.1256 < K < 0.471. Within this interval, all sample points exhibit an energy error not exceeding 0.25%. Except for a few isolated points, this energy error shows a gradual upward trend as the step size increases. Therefore, it is considered that Courant numbers within this range can be regarded as exhibiting good energy conservation properties.

In addition to one stable convergence region, two sample points also exhibit convergence during the solution process when K > 0.471. The first occurs at K = 0.628 with a maximum energy error of 0.875%, and the second at K = 0.691 with a maximum energy error of 0.953%. Although both points remain convergent in energy error during the 0.02 s solution, they still show gradual divergence over time as time increases. Their energy conservation properties are inferior to those of the aforementioned stable convergence region. So the sample points at 0.628 and 0.619 are not recommended for energy calculation. In practice, Courant numbers of 0.39 and below are usually used to ensure convergence accuracy.

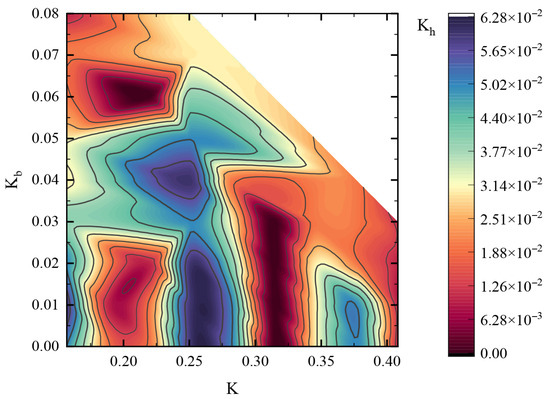

Unlike unstructured spatial grids, nodes in spatiotemporal finite element grids cannot be assembled arbitrarily. Under Lagrangian coordinates, the movement of spatiotemporal nodes implies continuous changes in element length. Excessively rapid changes, especially those exceeding the wave propagation speed, can significantly impair element convergence. and also influence the stability of the solution process. From the point of view of the energy error image, and are different from the oscillations around 0 when and are 0. At , = 2%, = 2%, and the maximum relative energy deviation generated by 0.02 s is . This is a 32-time difference from the 0.003% given earlier. This shows that and have an obvious influence on the convergence of the element. For different values, the energy deviation of and in 0.02 s was studied, respectively.

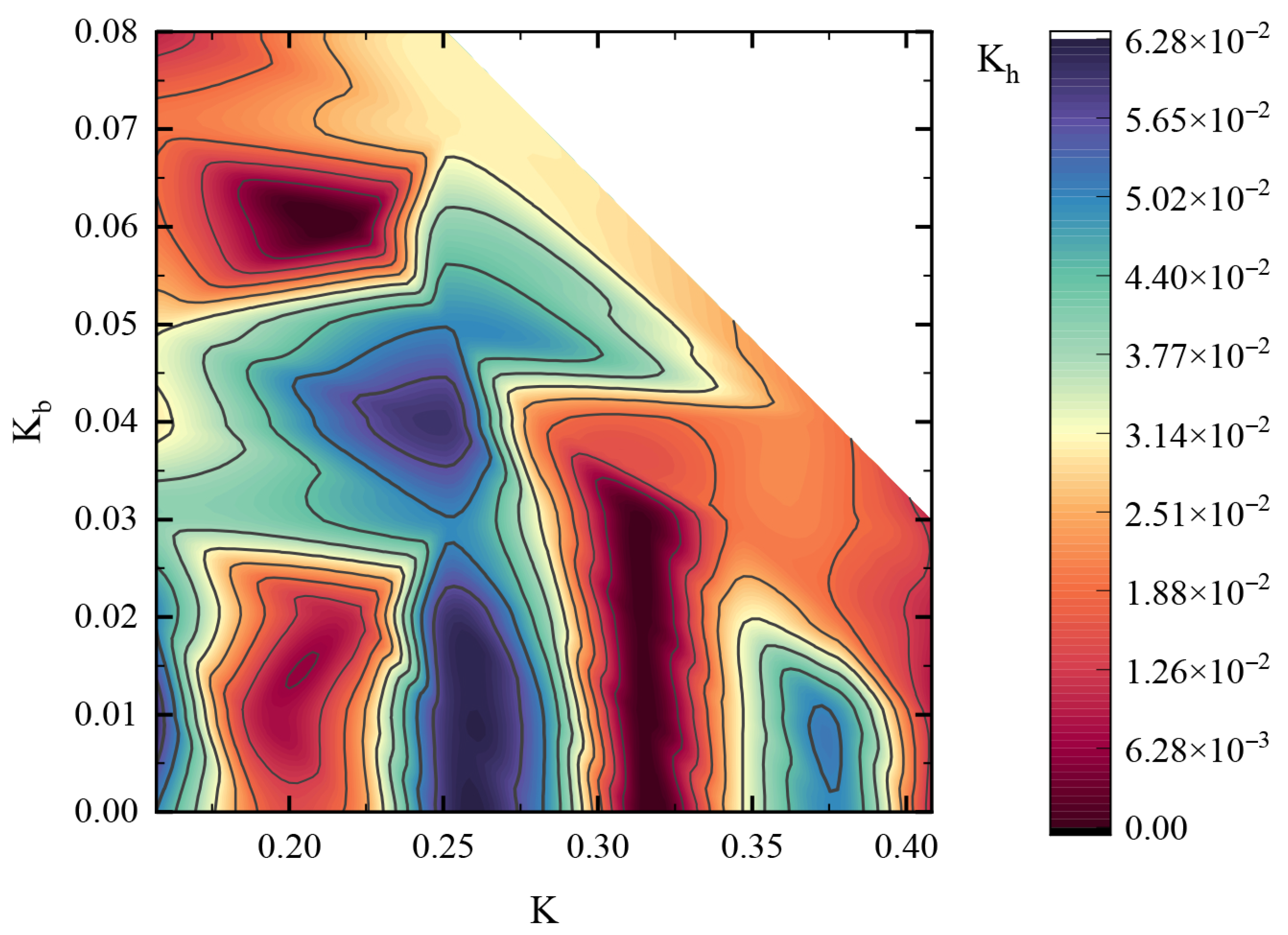

Figure 6 shows the node distribution with the energy deviation of 0.02 s less than 0.75% under different , , and . It can be seen from the diagram that the unit’s tolerance to and variations is quite different under different step sizes, which is caused by the nonlinearity of strain energy. No convergent solution with energy deviation less than 0.75% can be obtained outside the boundary equation. The blue area in the figure represents the smaller that is obtainable for a given and , which also means that it is less able to withstand – composite node movement. From the three-dimensional graph, it can be found that the capacity to withstand node changes in the space and time directions does not increase linearly with the increase in the value. When = 0.25∼0.27. The cell can bear the largest offset in both and directions, which is close to 1/4 sampling period. The maximum offset is 16% in the length direction and 10% in the time direction. Similarly, the offset tolerance is relatively small at the level. Therefore, the length of the element should be changed as the value of .

Figure 6.

The numerical convergence region influenced by , , and .

In this section, the normalized coordinate variables are presented, and the longitudinal wave velocity is chosen as the construction velocity of the Courant condition. It is concluded that the SACQ element has two convergent regions. In order to keep the energy stability, the element usually uses the Courant number between 0.15 and 0.41. In addition, the influence of and on energy deviation is investigated, and it is found that there is strong nonlinearity in the convergence interval. The inner envelope surface of the convergence interval is given by numerical calculation, and it is shown that and have little influence on the element convergence when the Courant number is 0.25–0.27.

5. Simulation and Verification

The SACQ element can describe a space-time variable grid, which is the major difference between it and the SAC elements. The appropriate use of the SACQ element can improve the solution efficiency and can simulate the dynamic problems with the sliding node. In this chapter, three examples are simulated, including the asynchronous solution, the wave propagation with a preloaded string, and a guyed mast dynamic simulation under impact transverse wave to demonstrate the possible usage of the SACQ element.

5.1. Asynchronous Solution

In Section 4, the value range of the Courant number was discussed. Stiffness, density, and the size of the element are related to the Courant number. Because of the material differences, the Courant number is different. The space domain can be divided into the long-step region and the small-step region. In this case, if the time step of the whole space domain is determined by the smaller Courant number, the solution efficiency is restricted in the long-step region. On the contrary, if the time step depends on the larger Courant number, it causes lower efficiency or even singularity. For balancing the accuracy and efficiency, the better solution strategy is to determine the step size of different regions according to the Courant number of different regions, and use transition elements between regions.

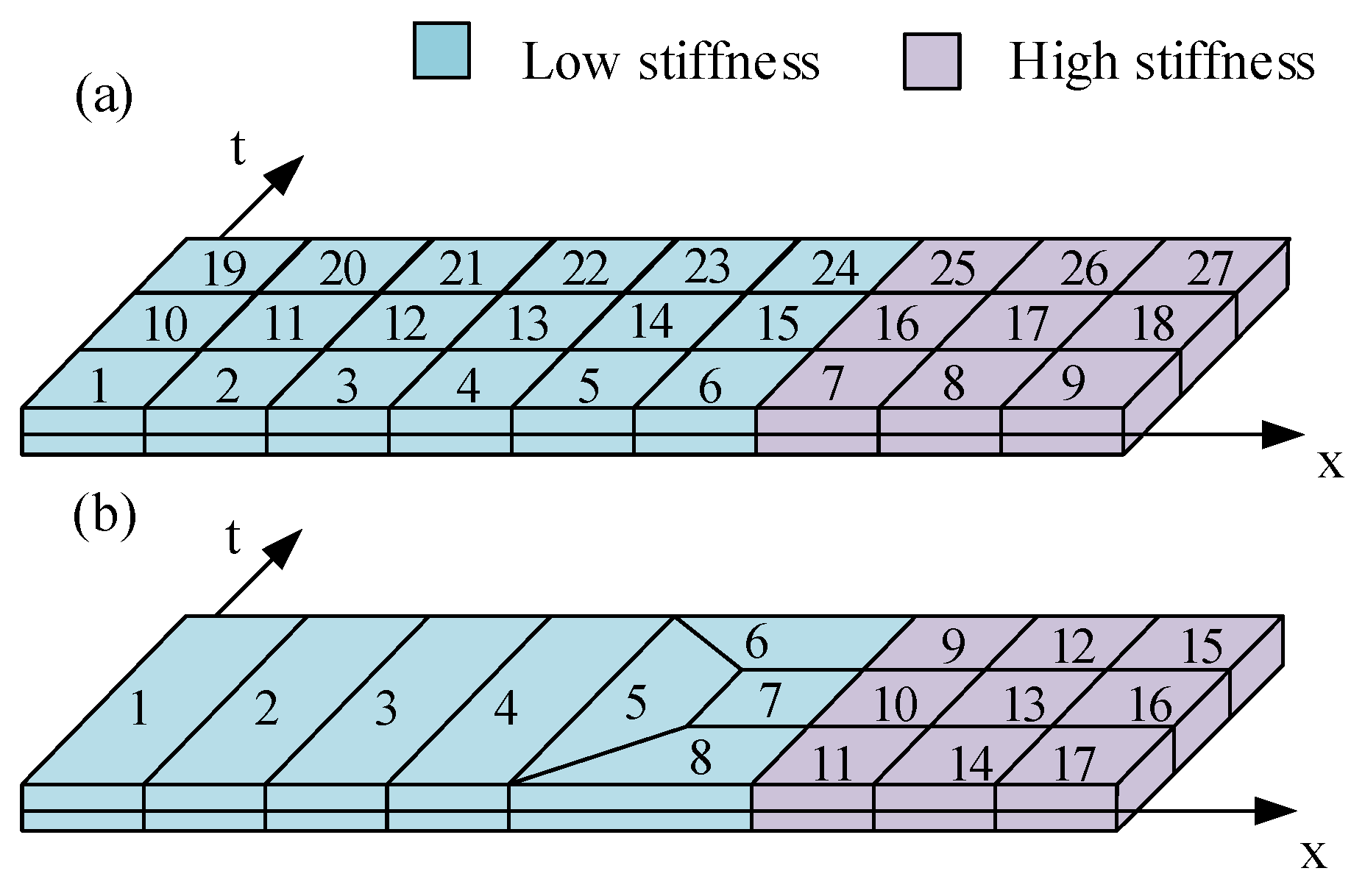

This example involves modeling a two-segment cable with different materials under the single-side velocity impact from the low stiffness end. The material properties of this element are shown in Table 1. The Courant numbers of two segments are 0.157 and 0.471, respectively. Meshes for this problem are depicted in Figure 7. Figure 7a is drawn with a structured grid; both the SAC element and the SACQ element can be used in this mesh. Figure 7b is drawn with an unstructured grid; only the SACQ element can be used in this mesh. Especially elements No. 5, 6, 7, and 8, called transition elements, which are deployed in the low stiffness zone for combining the two-segment cable. In one time slice, a total of 27 elements are used in Figure 7a compared with 17 elements in Figure 7b. In this case, the element number is reduced to 63%.

Table 1.

The material properties of the two-segment cable in single-side impact case.

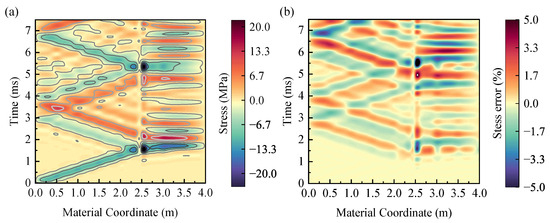

Figure 7.

The simulation of the two-segment cable. (a) Structured grid. (b) Unstructured grid.

In addition, due to differences in stiffness between the two segments of the cable, their Courant numbers also vary. In the low-stiffness region, the Courant number at a step size of 50 μs is 0.157, falling within the recommended convergence range. However, in the high-stiffness region, the Courant number at the same step size is 0.471, exceeding the recommended convergence range. Therefore, a three-layer time mesh must be employed to reduce the Courant number to 0.156 and achieve convergent results.

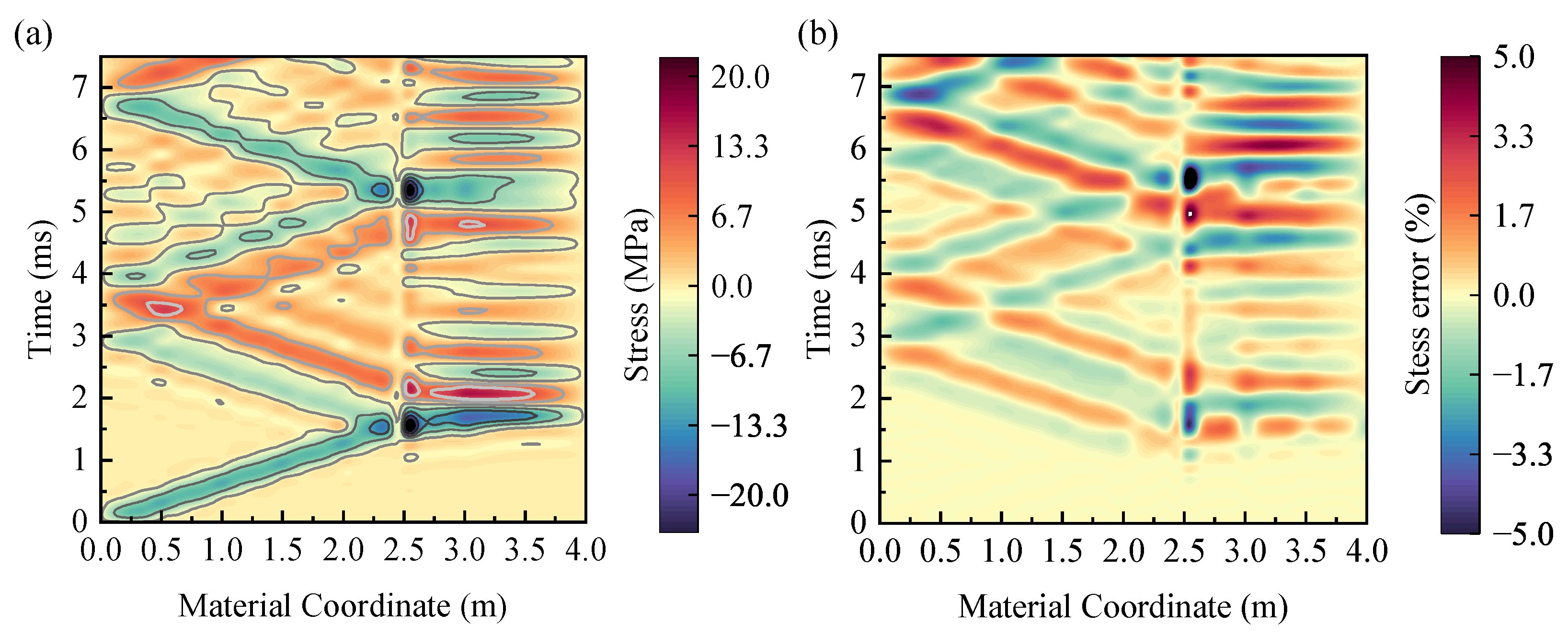

The stress distribution is depicted in Figure 8a, and the relative error between the structured grid and the unstructured grid is shown in Figure 8b. The slopes of two characteristic lines indicate the longitudinal wave velocity in two different materials, which are 1570 m/s and 4709 m/s, respectively. Between the boundaries of two segments, both methods show the transmission and reflection of the longitudinal wave. The transmission and reflection rates of elastic material are given in Equation (23)

In this case, is the damping coefficient which can be calculated with Equation (24)

The amplitude of the transmission wave and reflection wave in Figure 8a is in agreement with the amplitude calculated by Equation (23) and Equation (24). The maximum stress error shown in Figure 8b is less than 5%.

Figure 8.

The calculation result of the two-segment cable. (a) The stress distribution with an unstructured grid. (b) The relevant error between the structured grid and the unstructured grid.

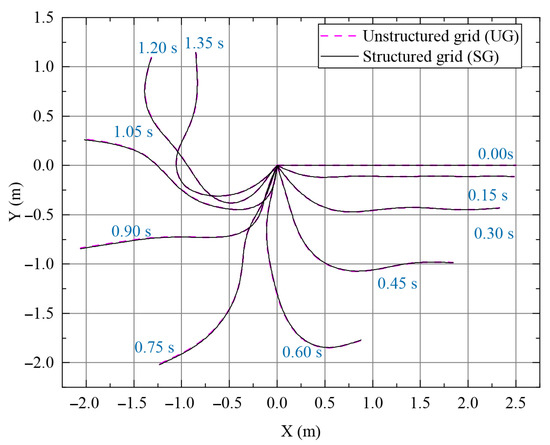

The flexible-free-pendulum is a practical example of ANCF cable and beam elements. It can also describe and evaluate the flexible deformation of segmented flexible cables. The length of flexible cable is 2.5 m in the example, whose material and the size of cross section are shown in Table 2. Because of the different stiffness, the left of the cable is a low-stiffness zone, and the right is a high-stiffness segment. The transition structure in Figure 5 can be used to partition structures with different stiffness in an unstructured grid. When the time slice span is 0.15 ms, SG requires 30 SACQ elements for partitioning, while UG requires 25 elements for partitioning, and the number of elements is reduced by 18.7%. The flexible cable is initially placed horizontally and hinged with the wall at the left end. It is released at t = 0 s and swings under the influence of gravity.

Table 2.

The material properties of the two-segment cable in free pendulum case.

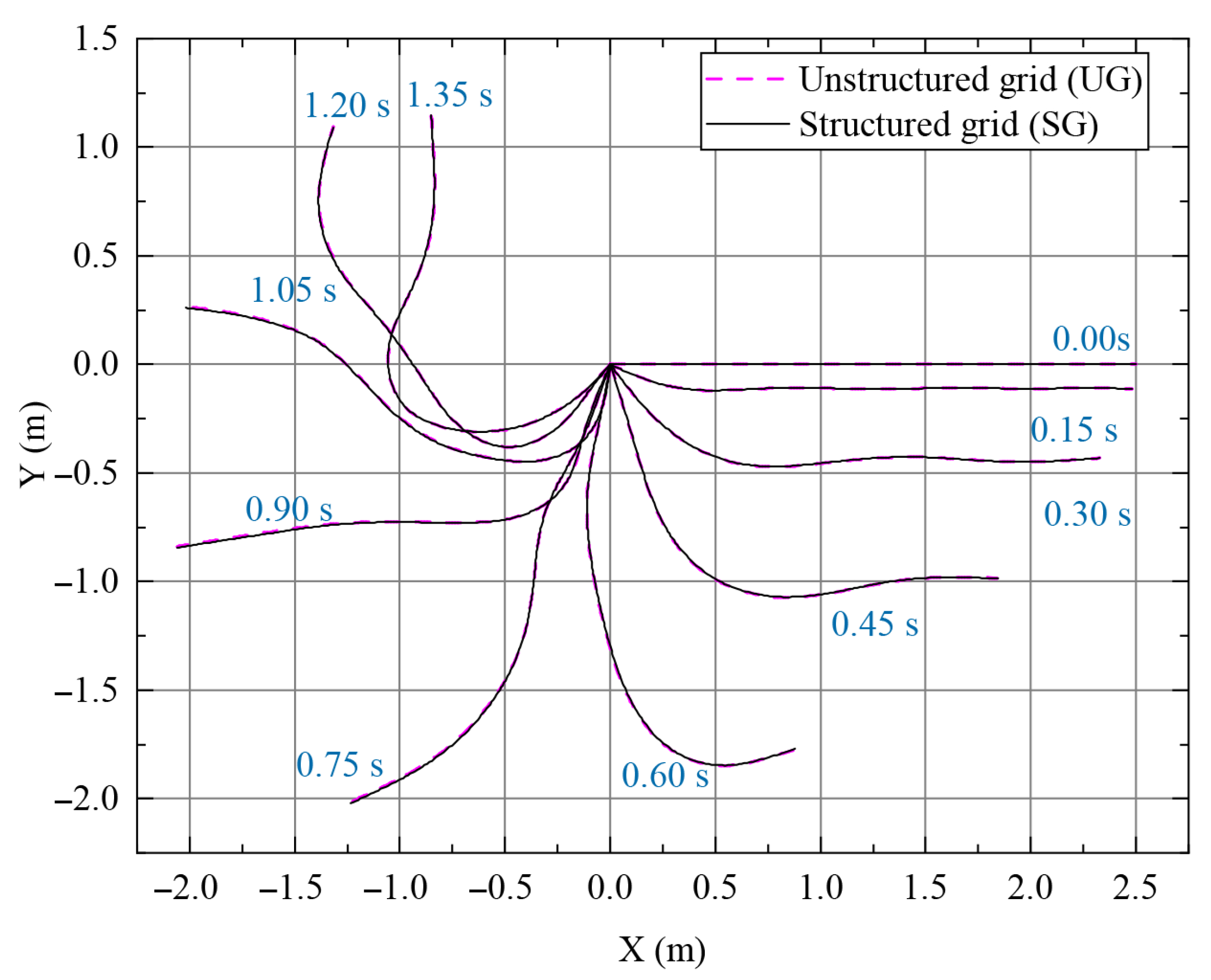

The dynamic response of the two-segment flexible free pendulum within 1.35 s is shown in Figure 9. It can be seen that the entire process of swinging, especially in the late-stage structure, exhibits obvious nonlinear dynamic phenomena, which are related to the pressure during the later part of the flexible cable motion. The results of SG and UG partitioning for solving the swinging are similar. The average calculation time per hundred steps using SG partitioning is 45.81 s, and using UG partitioning is 37.56 s, which reduces the calculation time by 18%.

Figure 9.

The structure response of free flexible pendulum with SG and UG per 0.15 s in 1.35 s.

Starting from 0.25 m, the root mean square error (RMSE) of the two partitioning methods is calculated every 0.25 m as shown in Table 3. The RMSE shows a trend of increasing with distance, which is related to the cumulative effect of deformation in the axial direction. The maximum value of RMSE is 2.37 mm, indicating that using UG partitioning significantly improves computational efficiency without significant changes in solution accuracy.

Table 3.

The nodal RMSE of free flexible pendulum.

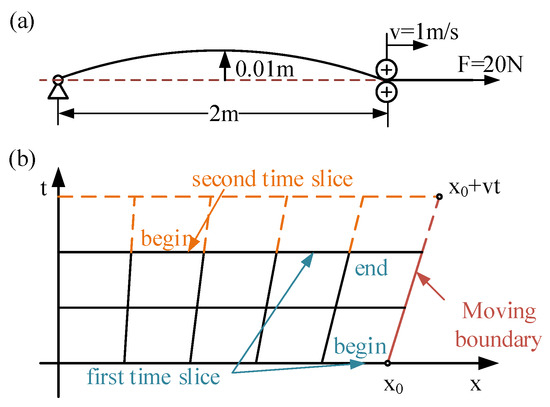

5.2. Taut-String with Variable Length

In this section, a dynamic model with a moving material coordinate boundary is studied. The simulation of a moving boundary can reflect the tracking of the performance of a quadrilateral space-time finite element for a sliding boundary.

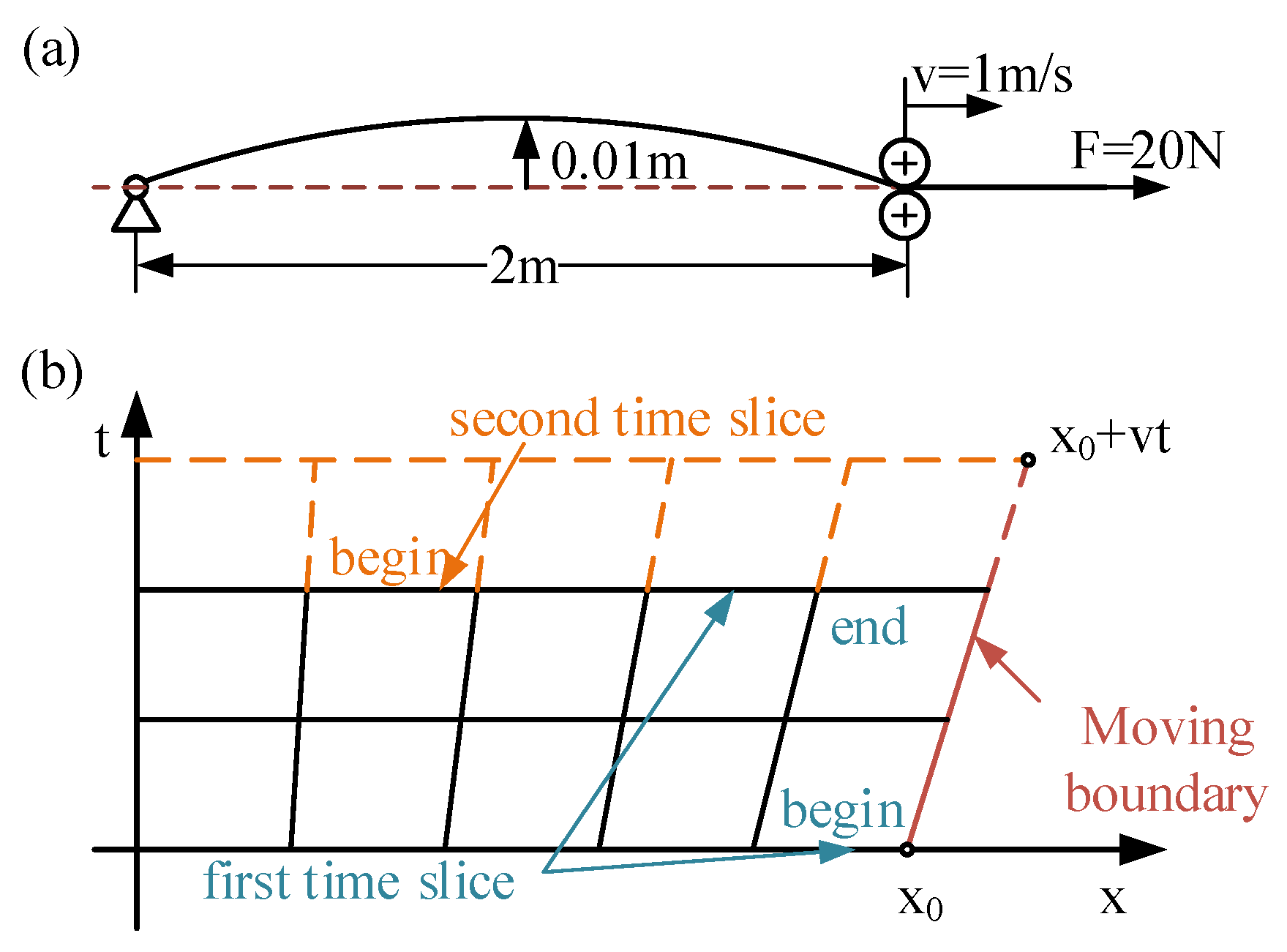

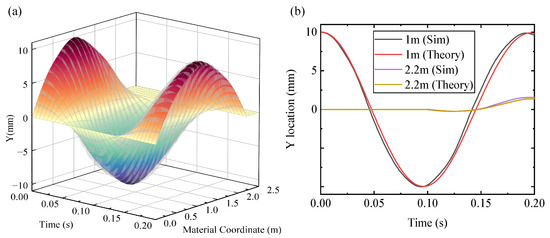

This example involves modeling a preloaded wire rope with one end hinged and one moving boundary. The problem is depicted in Figure 10a. The initial length of the string is 2 m. The string is initially bent into a sine curve, and the amplitude is 0.01 m. It is also stressed with a constant force of 2 N at the end with the moving boundary. The string is made of uniform material, for which the elastic modulus, density and area of the strings are 1.7 GPa, 1380 kg/ and m2, respectively.

Figure 10.

The physical model and mesh grid of taut string. (a) The physical model of the moving boundary of taut-string vibration. (b) The time-space finite element model.

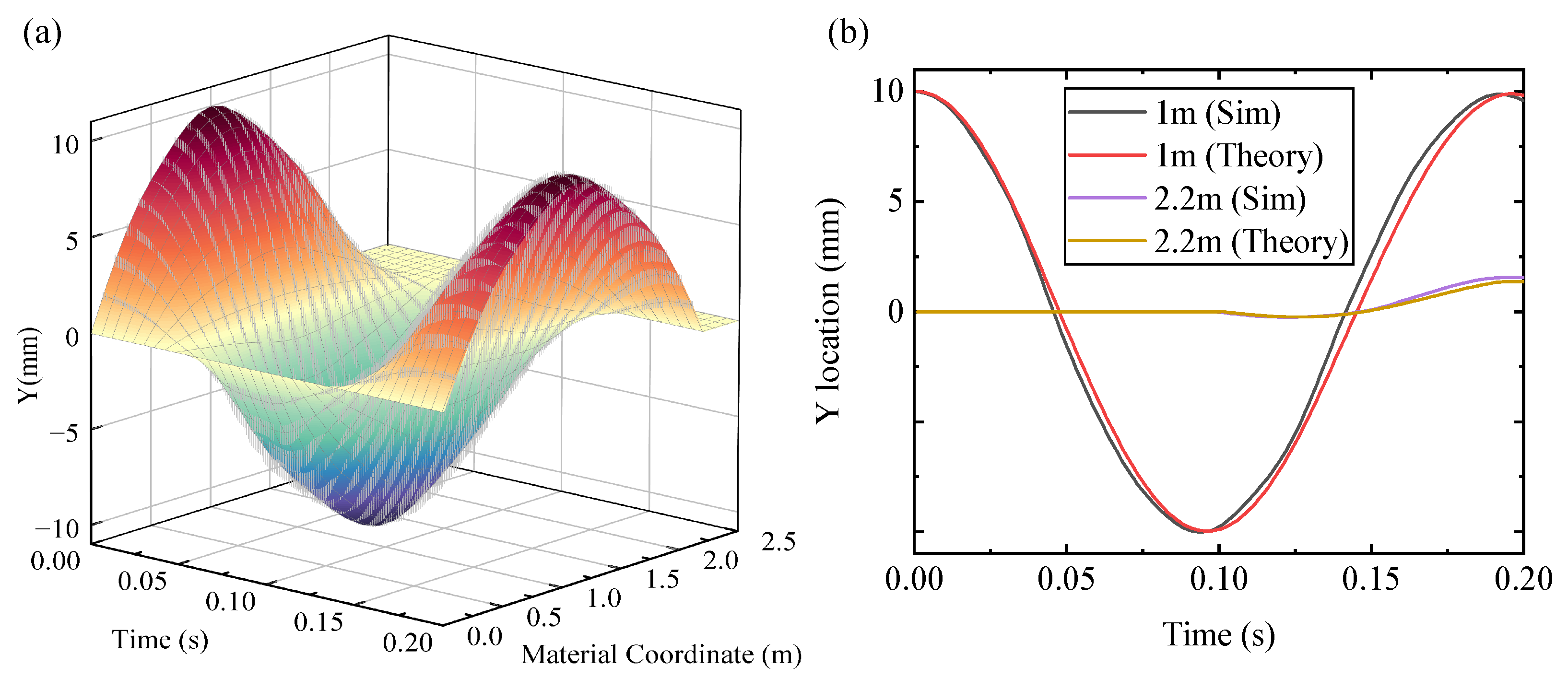

The string is released at , and the moving boundary moves at 1 m/s. The oscillation region extends from 2 m to 2.2 m in 0.2 s, which is around one period. The time step is 100 s, where K = 0.278. The wave velocity c is determined to be 21.48 m/s with the same initial configuration and material. The analytical solution of the equation is given by Balazs [33]. In Figure 11a, the colored surface shows the deflection of the string, and the gay error bars show the error compared with the analytical solution. The deflection at 1 m and 2.2 m in 0.2 s is shown in Figure 11b. Both two figures can indicate the SACQ has good solution accuracy.

Figure 11.

The simulation results of the taut sring. (a) The simulation results and error bars (gray). (b) The simulation and analytical solution at 1 m, 2.2 m in 0.2 s.

5.3. Simulation of Guyed Mast

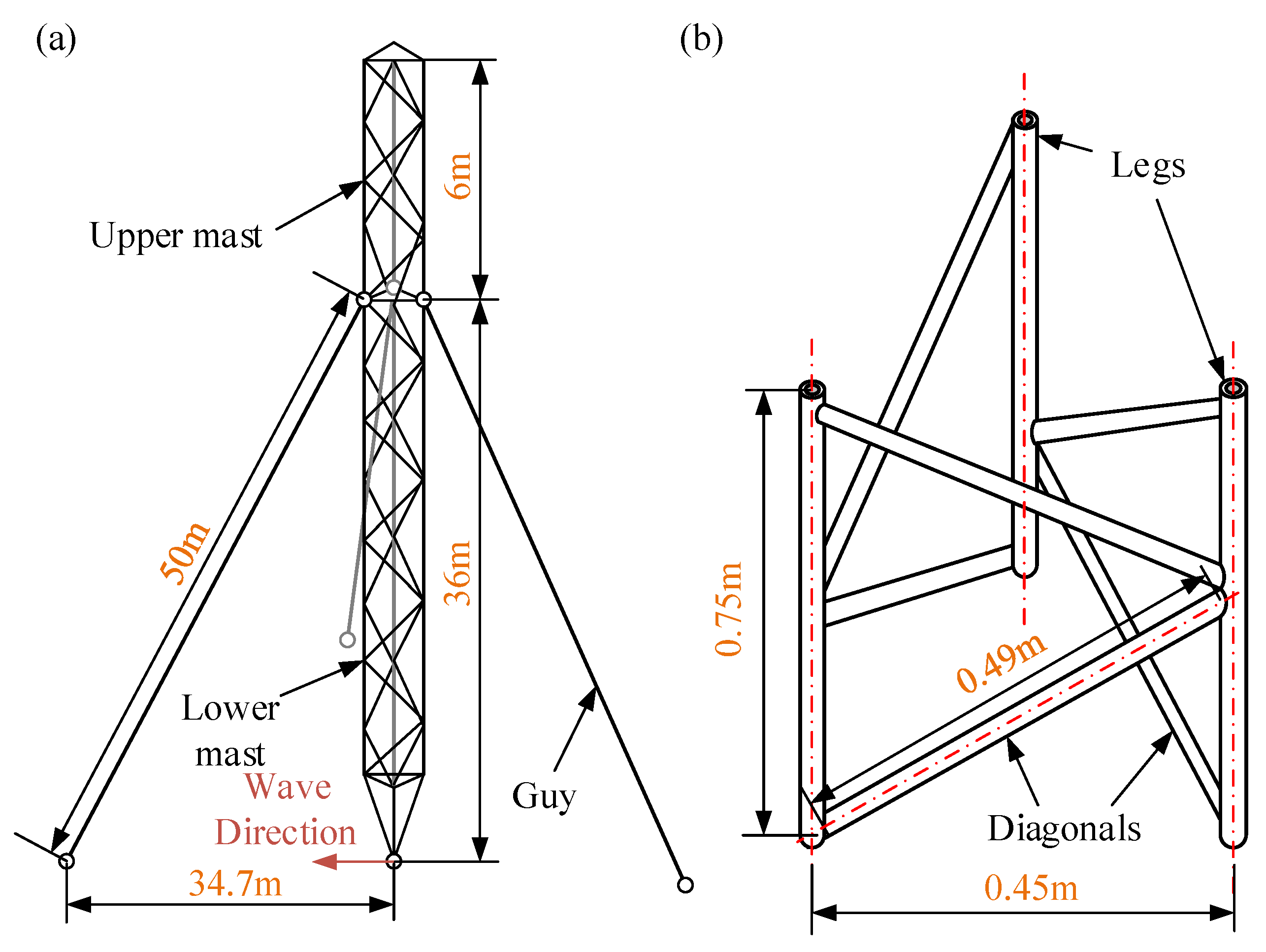

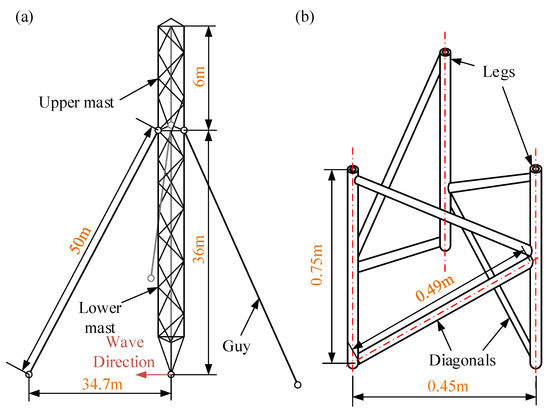

In this section, a dynamic response of a guyed mast with different guy stiffness is simulated with the SACQ element. This case shows that the SACQ mesh method can improve efficiency in response history analysis in this regard. Meanwhile, the dynamic response of guyed masts with different stiffness guys is also studied.

A space-deployable tower is illustrated in Figure 12, which is a typical guyed mast. The tower is composed of one lattice mast and three guys in uniform distribution on a circle, whose bottoms are fixed with one spacecraft. The standard section of lattice mast is a triangular prism with 0.75 m height, 3 legs and 6 diagonals. The spacing of two legs is equal to 0.45 m, and the angle α = 22.62°. The lattice mast can be simplified with the Guzman method [34] into a beam. The simplification algorithm is shown in Equation (25)

The material parameters with the lower label l are for the leg’s material, and the lower label d means the diagonal’s material. The lower label 0 means the simplified parameters. The materials for the lattice mast are shown in Table 4.

Figure 12.

The structure of (a) the guyed mast tower, (b) one section of lattice mast.

Table 4.

The material properties of the guyed mast.

The guys are made with two different materials; the simulation is labeled with No. 1 and No. 2 with different materials and can be further meshed with different space-time grids. The spatial size of the mast is 6 m, and the size of the guy element is 5 m. The time step of simulation is 6 ms. For the No. 1 simulation, the Courant number K is similar; thus, the tower is meshed with a structured grid (SG), which contains three temporal layers in one time slice. In each time layer, the structure is mashed with 37 elements, totaling 111 elements in one time slice. For the No. 2 simulation, the stiffness of the lattice mast is nines times that of the guy. So, both SG and unstructured grid (UG) can be used as Figure 7b. With this grid, there are only 60 elements in one time slice with the usage of an unstructured grid, which is 54.05% of the structured grid.

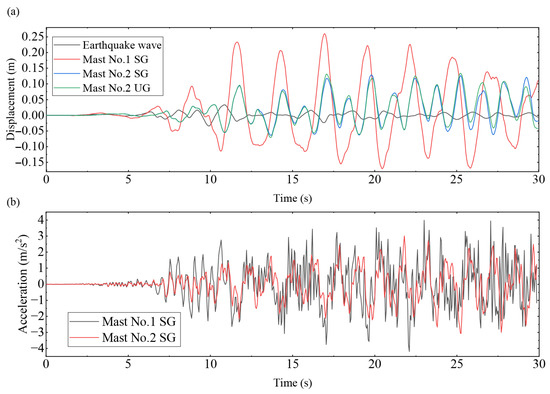

The transverse impact wave generated by the vibration of spacecraft can be applied on the structure in the acceleration form or the displacement constraint form. Because of the low lateral stiffness, it takes a transverse wave for simulation. In this case, the guyed mast structure has four nodes hinged to the ground, and the transverse wave can excite the structure by being applied on the hinged nodes.

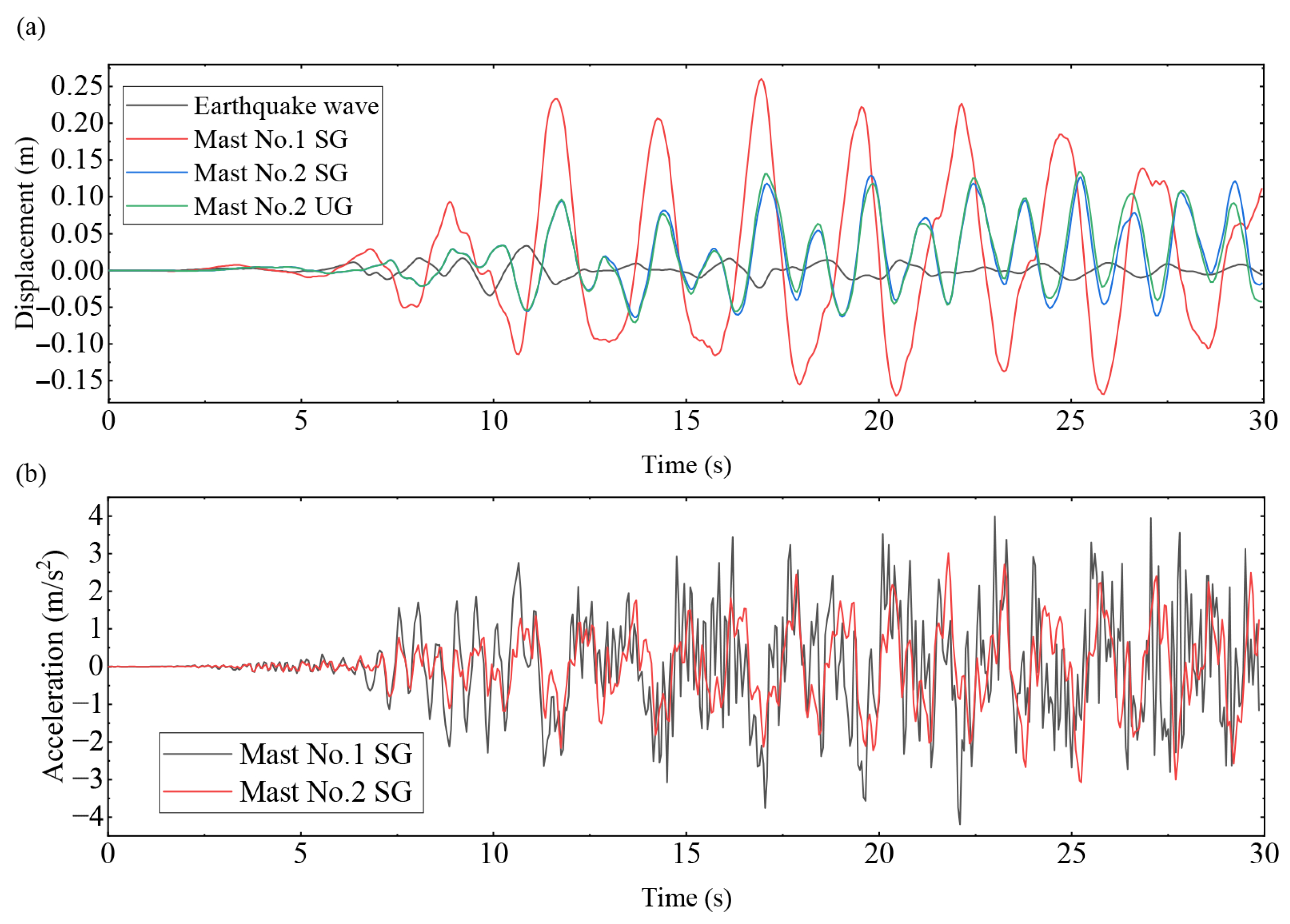

The failure of the guy and the communication facility at the top of the lattice mast are the major failure modes of a guyed mast. First, the response of guyed masts with different stiffness was analyzed, and the displacement responses of the mast top are extracted as shown in Figure 13a. Compared with the impact wave, higher displacement amplitude is shown at the mast top node. The maximum amplitude of the mast is 4.1 times in the No. 1 simulation and 1.68 times in the No. 2 simulation. The structure suffered a whiplash effect, but this phenomenon is reduced with lower guy stiffness. During the No. 2 simulation, SG and UG are used in the simulation, and both methods have similar displacement responses. Figure 13b shows acceleration responses of the mast top; a higher acceleration peak is shown in mast No. 1 due to the higher structure stiffness, and the maximum acceleration of the structure under different stiffness is 3.99 m/. It is not necessary to carry out the anti-impact requirement for the communication device.

Figure 13.

Nodal displacement and acceleration of the top node (a) Displacement of mast in material No. 1 and No. 2 excited by impact transverse wave. Mast No. 2 is meshed with a structured grid and an unstructured grid. (b) Acceleration of mast in material No. 1 and No. 2 simulation.

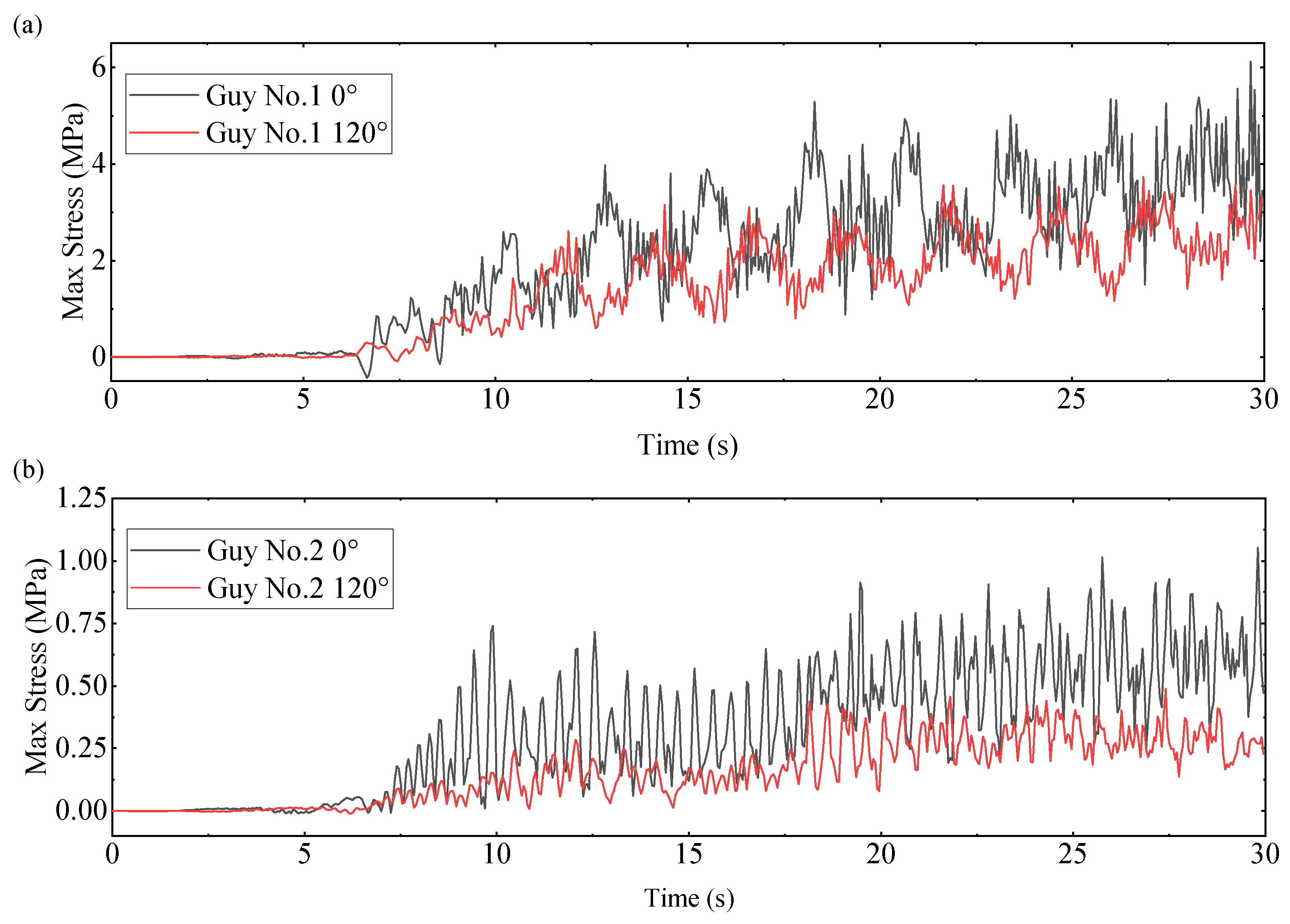

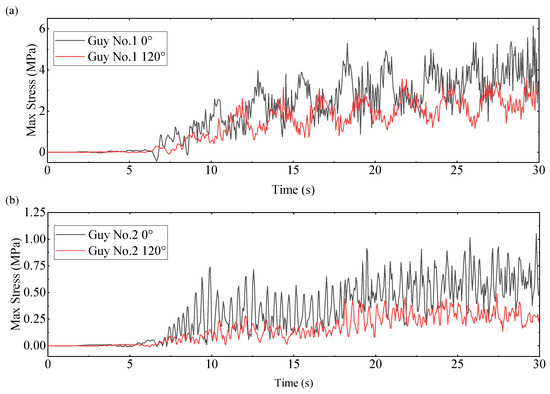

Second, the tensile failure due to the impact is studied. Figure 14 shows the maximum stress in the direction of the impact wave and 120° to the direction of the impact wave at material No. 1 and No. 2, respectively. The maximum stresses of No. 1 guy and No. 2 guy are 6.12 MPa and 1.05 MPa. It shows that stiffness has a great influence on the stress of the guy. The average stress of the guy in the 0° direction at different stiffnesses are all greater than the average stress in the 120° direction. In the area shown, the guy in the 0° direction is subjected to compressive stress in Figure 14 at 6 s∼7.5 s, which indicates that the guy will slacken under the action of transverse wave without preload. It is also related to the minus X direction displacement in Figure 14a. Material No. 1 undergoes a longer slackening process. The guy in a relaxed state will suffer an impact when suddenly tensed, which is not conducive to the life of the guy, so a certain tension needs to be applied in actual use to ensure that the guy is always in tension.

Figure 14.

(a) The maximum stress is in the No. 1 guys. Two guys are at 0° and 120° to the impact wave. (b) The maximum stress in is the No. 2 guys. Two guys are at 0° and 120° to the impact wave.

Different meshing has a great influence on solution accuracy and efficiency. For example, the average calculation time on each time slice is 78.60% of the use of the structured grid in material No. 2 after using the unstructured grid. The average calculation error of displacement accuracy is 4.7%, which means the usage of an unstructured grid can improve the computational efficiency under the guarantee of calculation accuracy. However, the improvement does not reach the level of decline in element number. The reason is that the convergence to the exact solution needs more iterations with the increase in an unstructured grid to increase the step size of the time slice. This prolongs the solution time to a certain extent.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the inverse method is proposed for the establishment of a high-order space-time quadrilateral ANCF cable (SACQ) element’s shape function. The integration algorithm based on the perspective transformation is proposed for action integration. The integration at the boundary of the element is categorized in two classes and discussed meticulously. The convergence of the SACQ element is proposed to be related to the Courant number and the dislocation of the spacetime nodes, and its numerical convergence domains on structured and unstructured grids are given by the single-side impact problem as an example of convergence. The single-side impact example shows good accuracy on unstructured grids using two-segment rods by calculating stress wave transformation and reflection. The free-flexible pendulum shows the SACQ elements have better solution efficiency by meshing with the unstructured grid. The comparison with the analytical solution in the taut-string case shows its ability to solve the fixed-speed slip boundary problem. For the simulation of a guyed mast under transverse wave impact, guys with different moduli can both keep low acceleration and will not cause fracture failure. A low stiffness guy can reduce the “whipping-effect” at the top of the mast and have lower maximum stress in the guy. Flexible cords of lower rigidity can be used to reduce the impact of transverse waves as much as possible within the allowable range.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.; methodology, D.C.; software, D.C.; validation, D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.; writing—review and editing, D.C. and J.F.; visualization, J.F.; supervision, N.H.; project administration, J.F. and Z.H.; funding acquisition, N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work is funded by the Independent Research and National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 12402473].

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, Z.; Jiang, X. Effects of Orbital Perturbations on Deployment Dynamics of Tethered Satellite System Using Variable-Length Element. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 22399–22407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housner, J.; Belvin, W. Dynamic response and collapse of slender guyed booms for space application. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 1986, 23, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; He, B.; Zhang, L. Deployment dynamics modeling and analysis for mesh reflector antennas considering the motion feasibility. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 91, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Gomes, S.; Pinheiro Gomes, S.C. A new dynamic model of towing cables. Ocean Eng. 2021, 220, 107653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, P.; Li, K.; Yu, Z. Computer implementation of piecewise cable element based on the absolute nodal coordinate formulation and its application in wire modeling. Acta Mech. 2019, 230, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. Guyed Masts Exposed to Guy Failure. In Proceedings of the Structures Congress 2006, St. Louis, MI, USA, 18–21 May 2006; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Banerjee, A. Coupled thermomechanical modelling of shape memory alloy structures undergoing large deformation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 220, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Cui, Y.; Lan, P.; Lu, N.; Xue, Y. A two-dimensional space-time absolute nodal coordinates cable element and its application in shape memory alloy. Acta Mech. 2023, 234, 3687–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstmayr, J.; Sugiyama, H.; Mikkola, A. Review on the Absolute Nodal Coordinate Formulation for Large Deformation Analysis of Multibody Systems. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2013, 8, 031016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Hedegaard, B.D. Absolute nodal coordinate formulation for dynamic analysis of reinforced concrete structures. Structures 2021, 33, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shabana, A.A. A two-dimensional shear deformable ANCF consistent rotation-based formulation beam element. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 87, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. Definition of the Slopes and the Finite Element Absolute Nodal Coordinate Formulation. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 1997, 1, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.; Yakoub, R. Three Dimensional Absolute Nodal Coordinate Formulation for Beam Elements: Theory. J. Mech. Des. 2001, 123, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstmayr, J.; Shabana, A.A. Analysis of Thin Beams and Cables Using the Absolute Nodal Co-ordinate Formulation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2006, 45, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, H.; Koyama, H.; Yamashita, H. Gradient Deficient Curved Beam Element Using the Absolute Nodal Coordinate Formulation. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2010, 5, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, M.; Gao, Q.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Sævik, S. Efficiency improvement on the ANCF cable element by using the dot product form of curvature. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 102, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, C.; Irani, R.A. Efficient semi-implicit numerical integration of ANCF and ALE-ANCF cable models with holonomic constraints. Comput. Mech. 2023, 71, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Luo, Q. Acoustoelastic effect simulation by time–space finite element formulation based on quadratic interpolation of the acceleration. Wave Motion 2020, 93, 102465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warzee, G. Finite element analysis of transient heat conduction application of the weighted residual process. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1974, 3, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, G.M.; Hughes, T.J.R. Space-time finite element methods for second-order hyperbolic equations. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1990, 84, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Gao, Q. Space-Time mixed FEM. J. Dyn. Control 2007, 5, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Peng, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, W. The symplectic algorithms for Hamiltonian dynamic systems based on a new variational principle part I: The variational principle and the algorithms. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 2013, 30, 461–467. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Peng, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, W. The symplectic algorithms for Hamiltonian dynamic systems based on a new variational principle part II: The proof of the symplecticity. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 2013, 30, 468–472. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Peng, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, W. The symplectic algorithms for Hamiltonian dynamic systems based on a new variational principle part III: The numerical examples. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 2013, 30, 473–478. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, J.C.; Sauer, R.A.; Ober-Blöbaum, S. C1-continuous space-time discretization based on Hamilton’s law of varying action. ZAMM-J. Appl. Math. Mech./Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 2017, 97, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.A.; Cockburn, B.; Nguyen, N.C.; Peraire, J. Symplectic Hamiltonian finite element methods for linear elastodynamics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 381, 113843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajer, C.I. Triangular and tetrahedral space-time finite elements in vibration analysis. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1986, 23, 2031–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajer, C.I. Adaptive mesh in dynamic problems by the space-time approach. Comput. Struct. 1989, 33, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajer, C.; Bogacz, R.; Bonthoux, C. Adaptive space-time elements in dynamic elastic-viscoplastic problem. Comput. Struct. 1991, 39, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, S.; Jourdan, F.; Madani, T. 4D Remeshing Using a Space-Time Finite Element Method for Elastodynamics Problems. Math. Comput. Appl. 2018, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, U.; Steinbach, O.; Tröltzsch, F.; Yang, H. Unstructured Space-Time Finite Element Methods for Optimal Control of Parabolic Equations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 43, A744–A771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, K.; Lu, N.; Lan, P. A Space-Time Absolute Nodal Coordinate Formulation Cable Element and the Study of Its Accuracy and Efficiency. Machines 2023, 11, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, N.L. On the solution of the wave equation with moving boundaries. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1961, 3, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guzmán, A.M.; Rosales, M.B.; Filipich, C.P. Continuous one-dimensional model of a spatial lattice. Deformation, vibration and buckling problems. Eng. Struct. 2019, 182, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).