Experimental Validation and Dynamic Analysis of Additive Manufacturing Burner for Gas Turbine Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

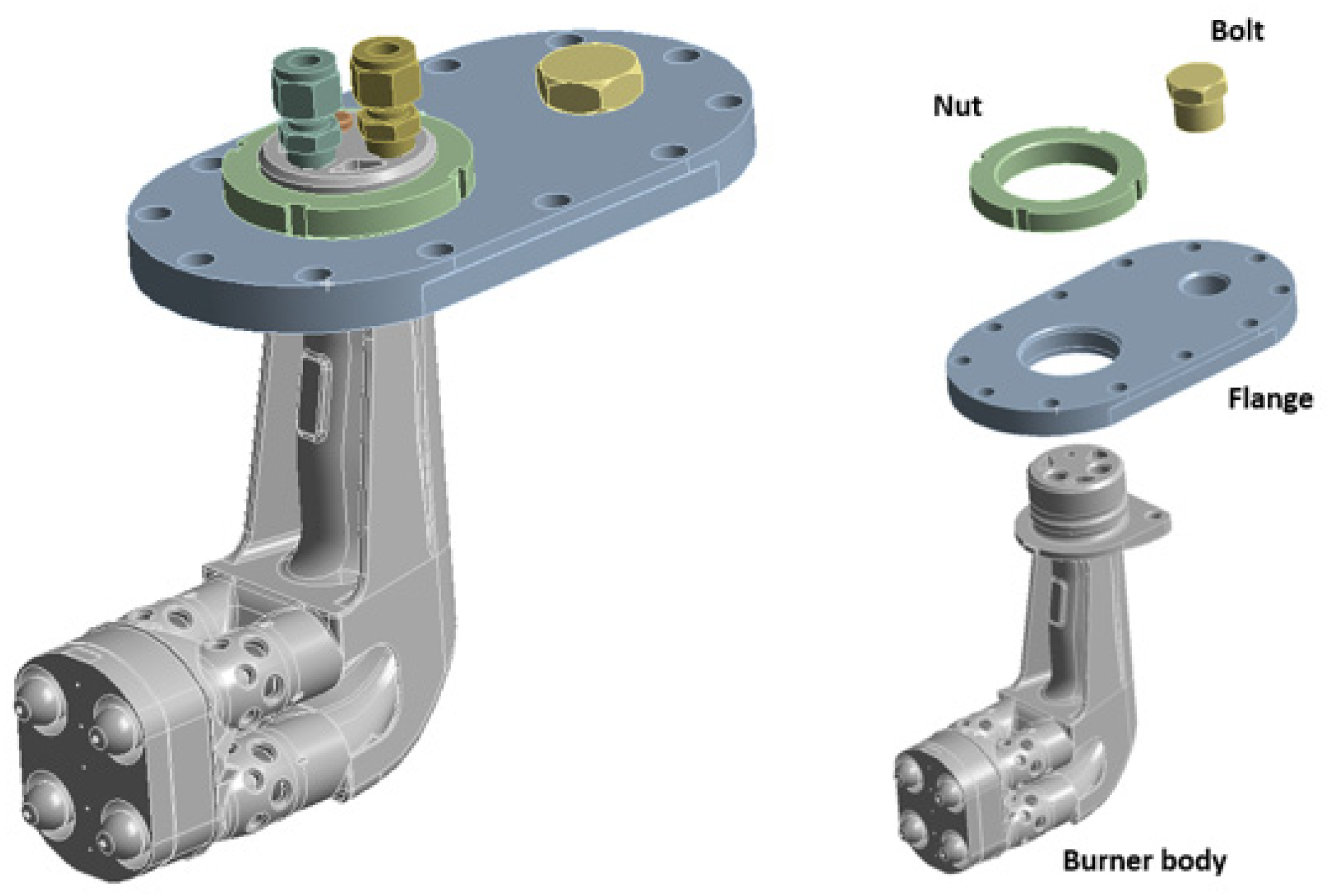

2.1. Burner Design for Additive Manufacturing

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Structural Dynamics Verification of AM Burner

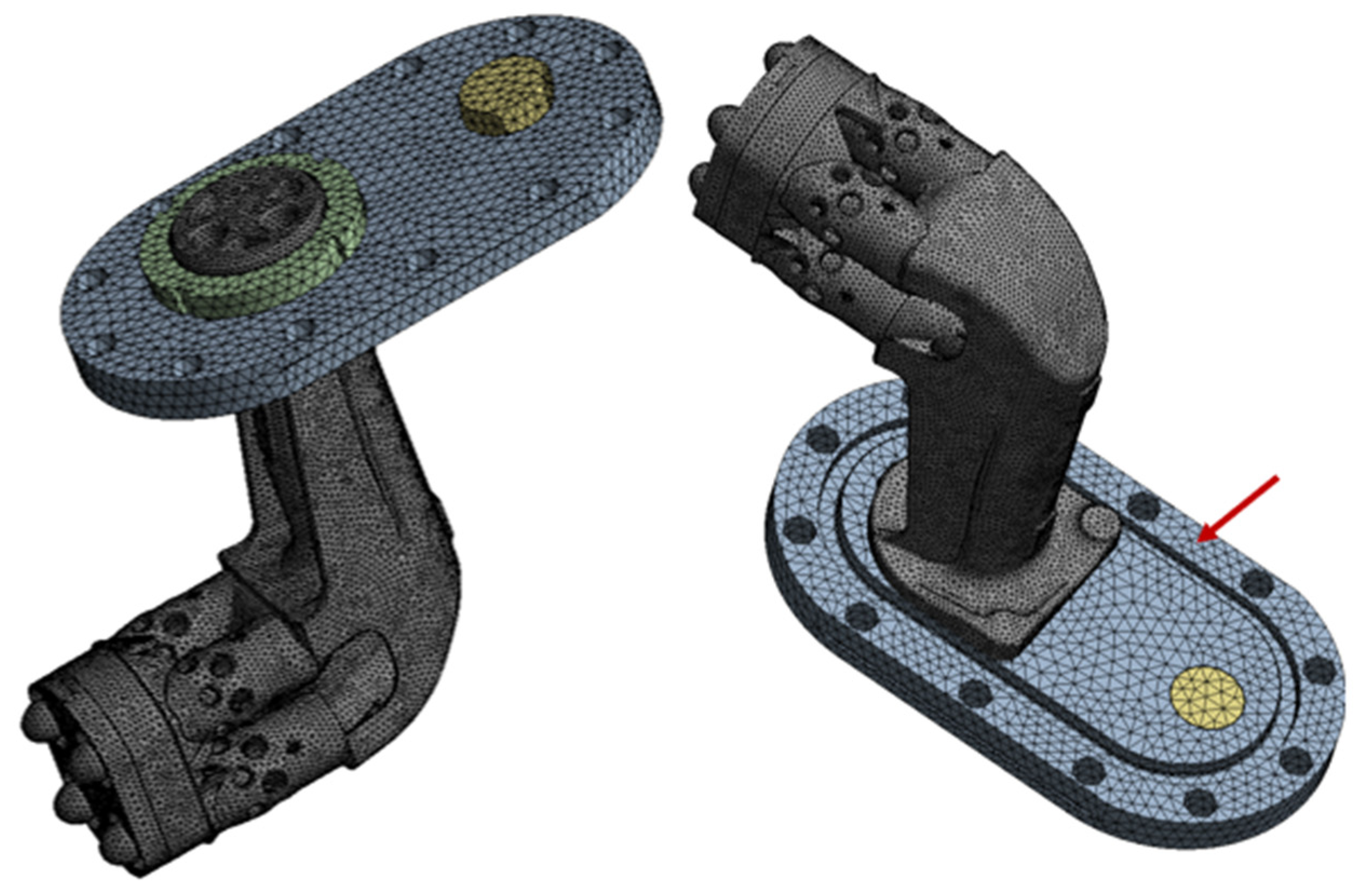

2.3.1. Finite Element Model

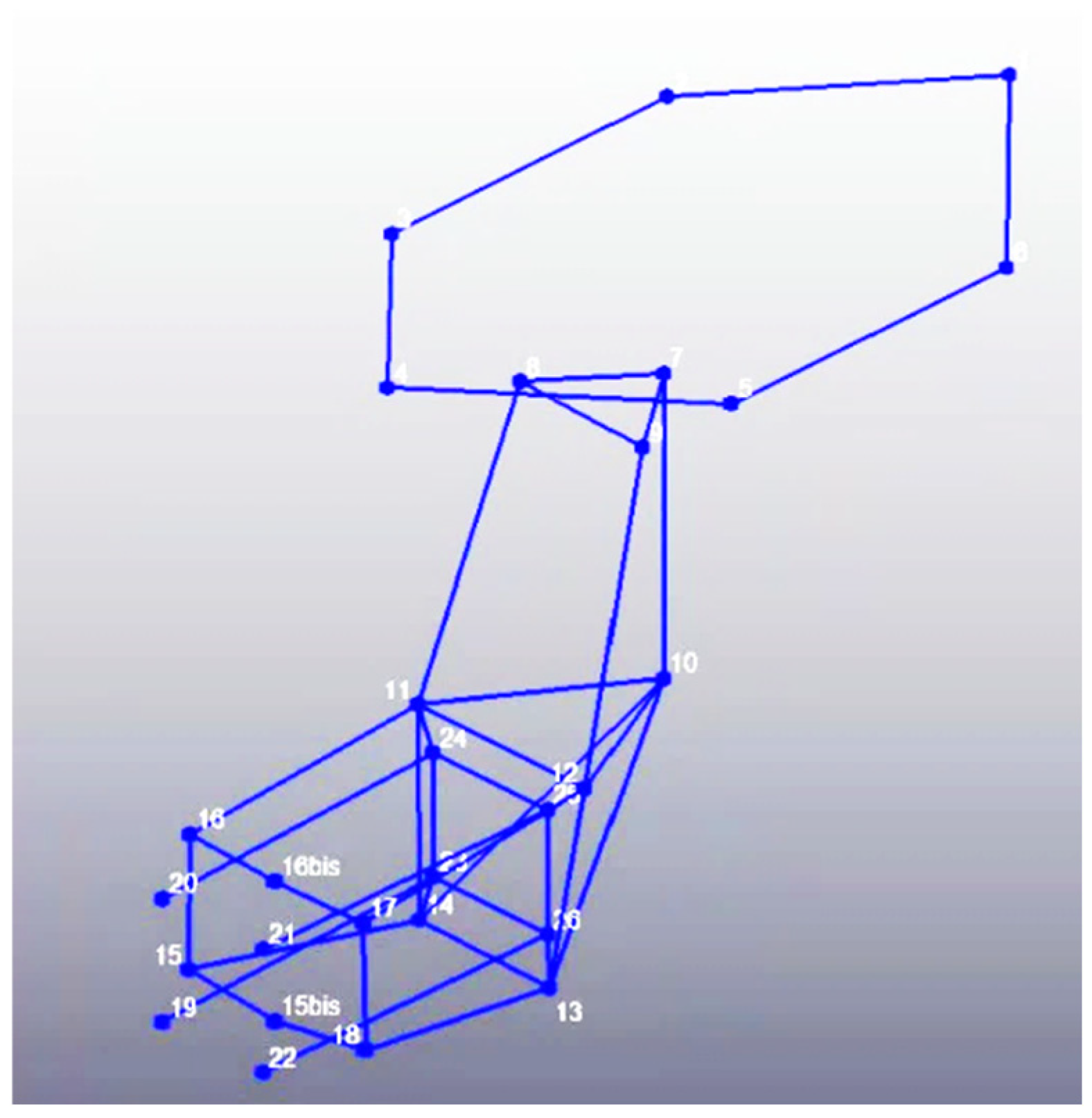

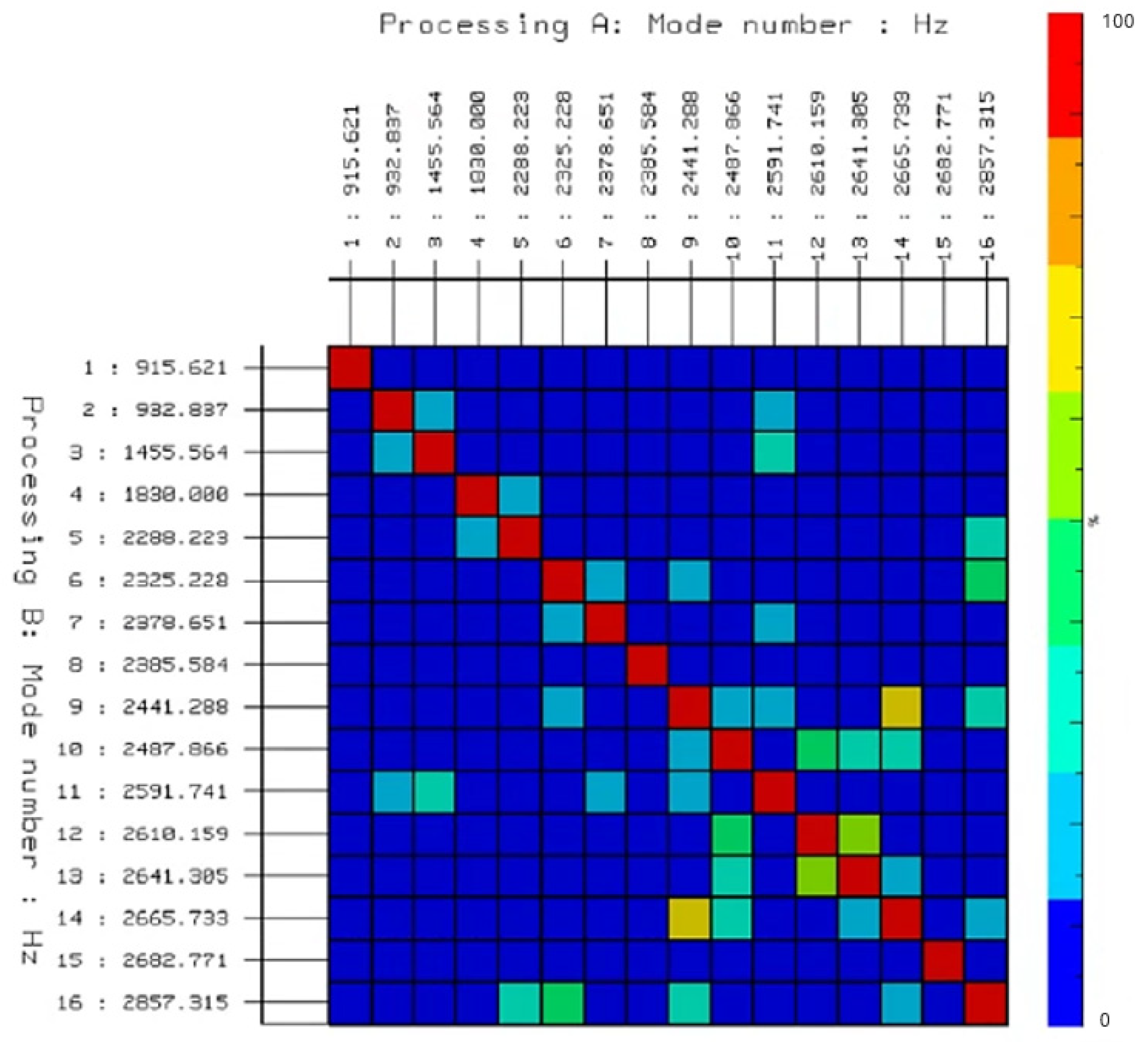

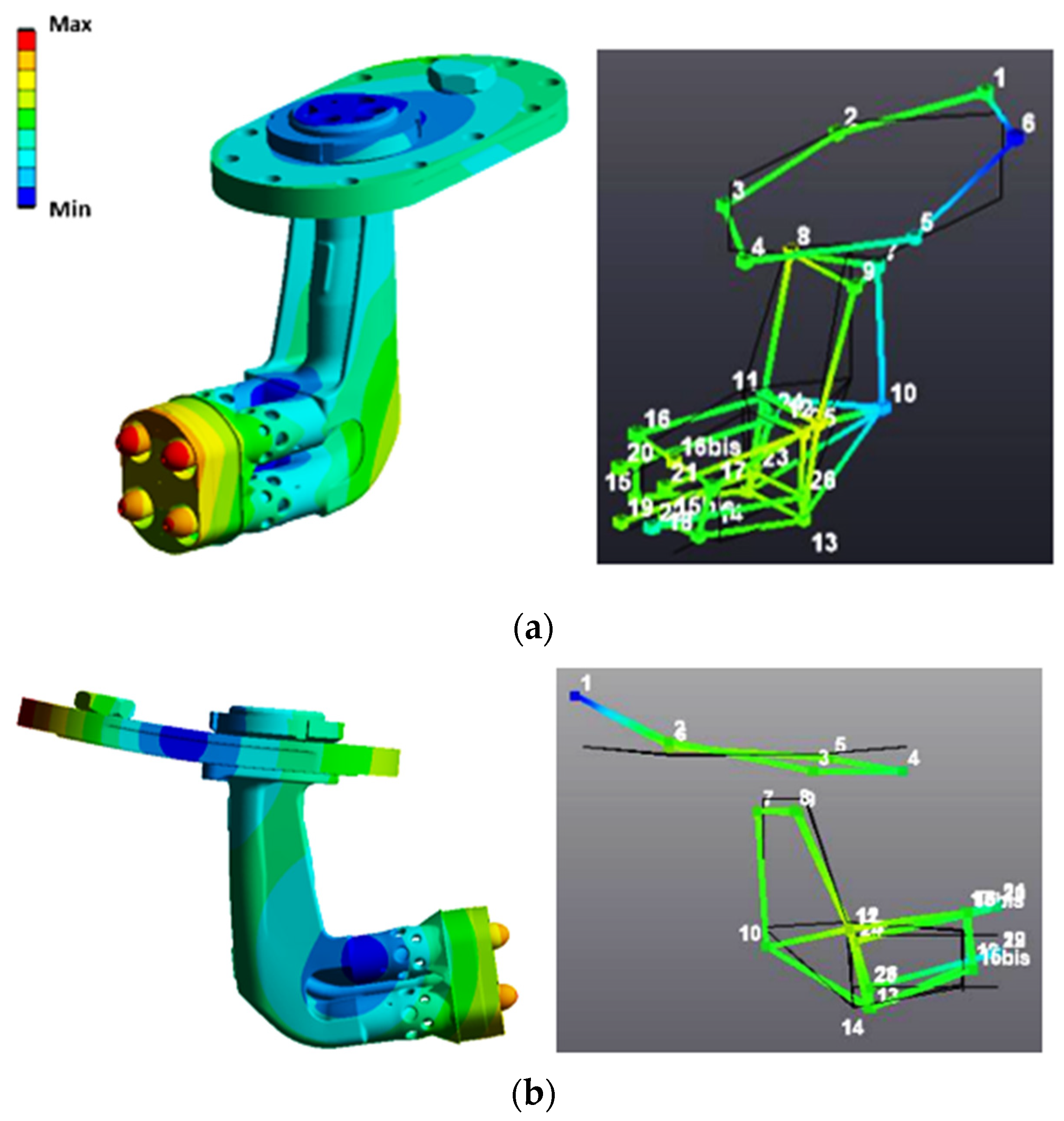

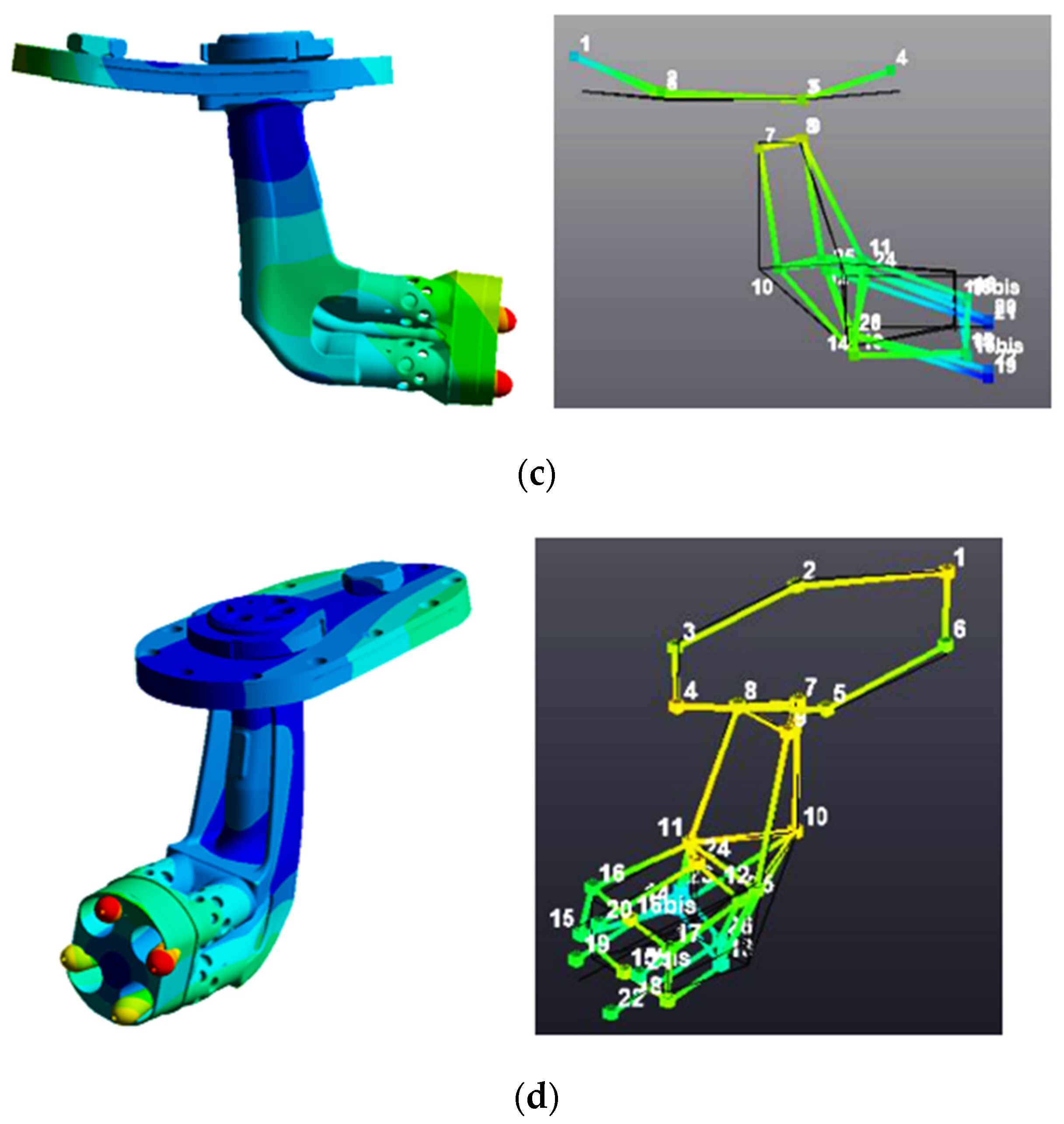

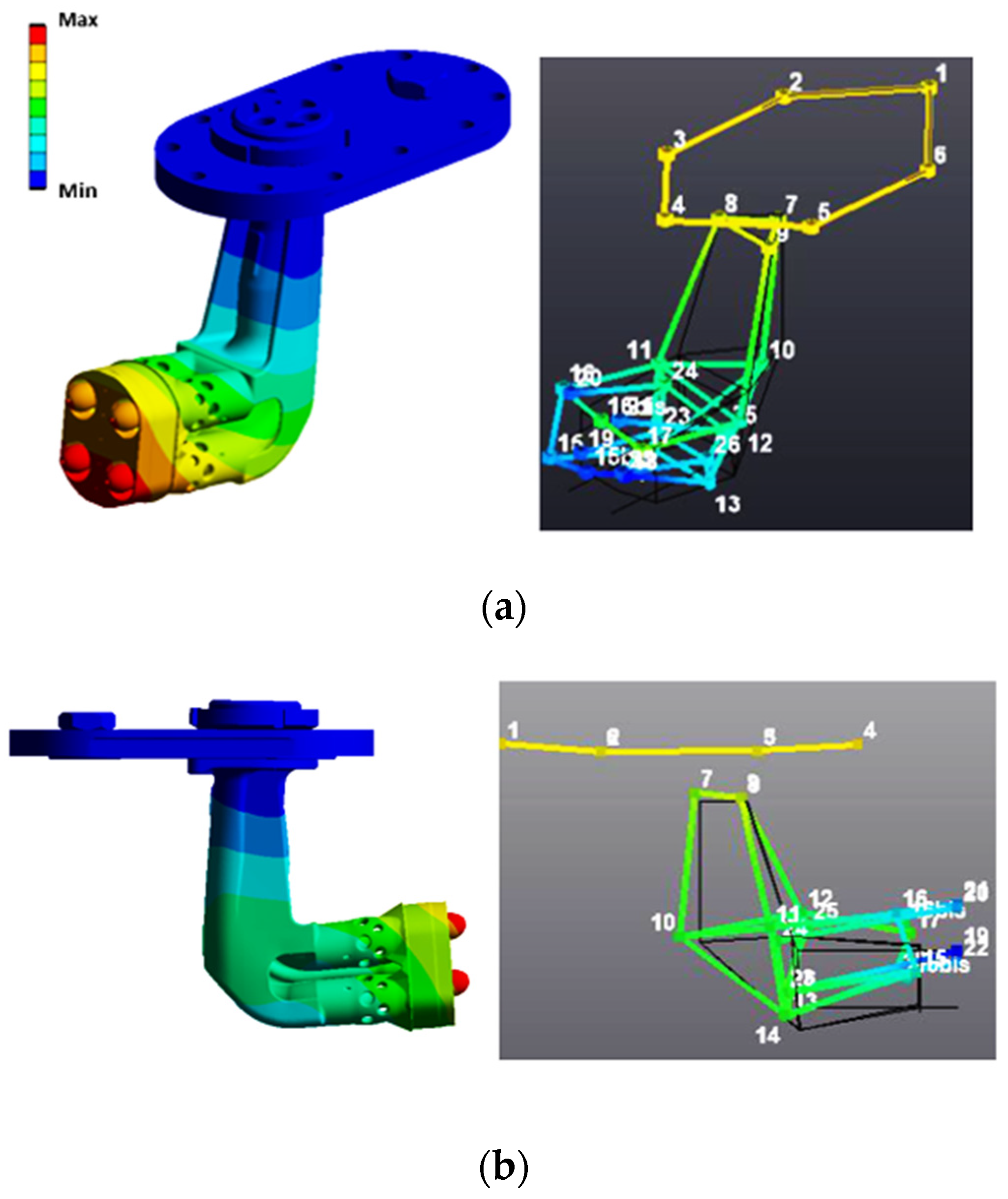

2.3.2. Numerical Pre-Test

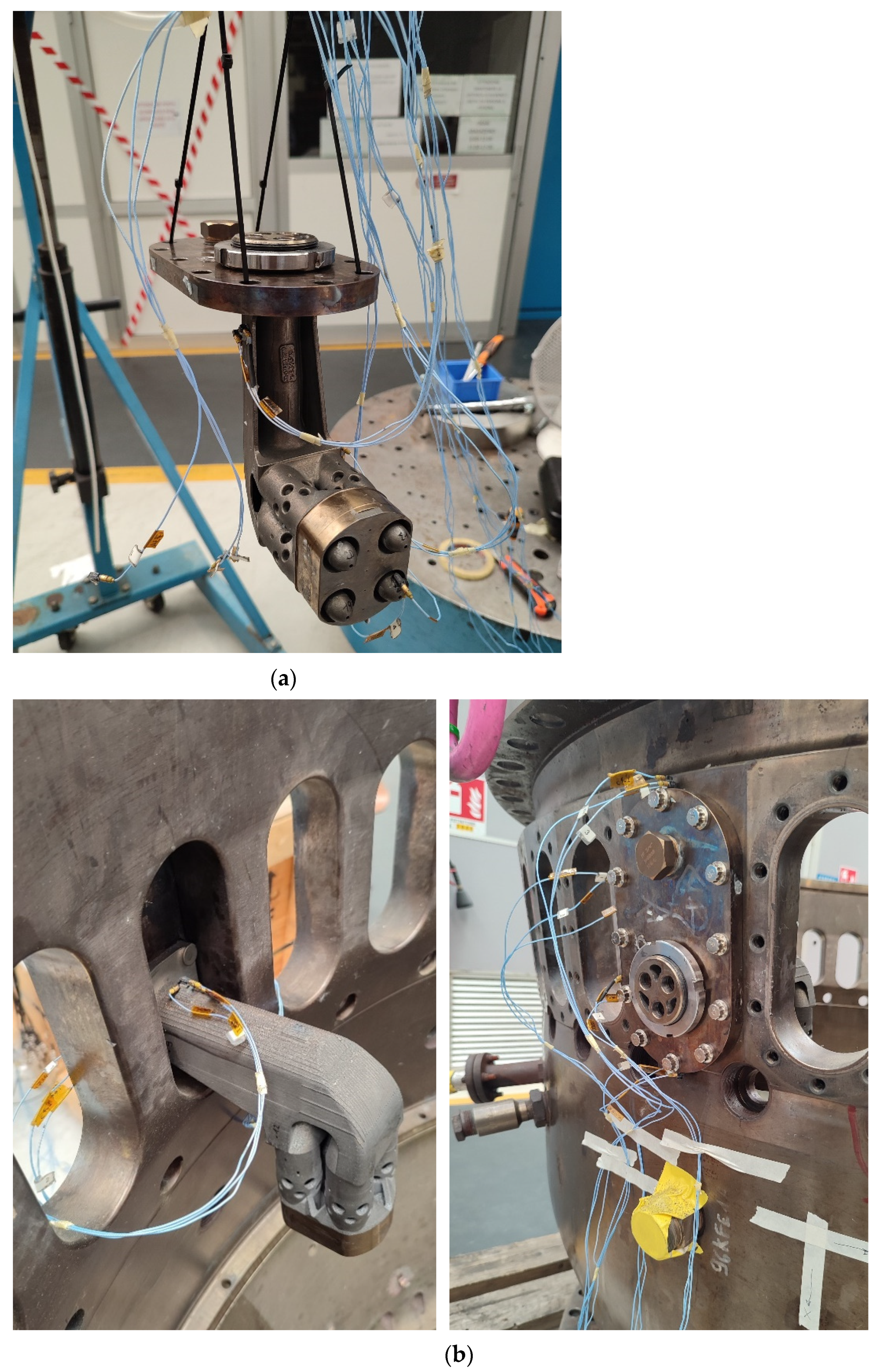

2.3.3. Experimental Ping Test Setup

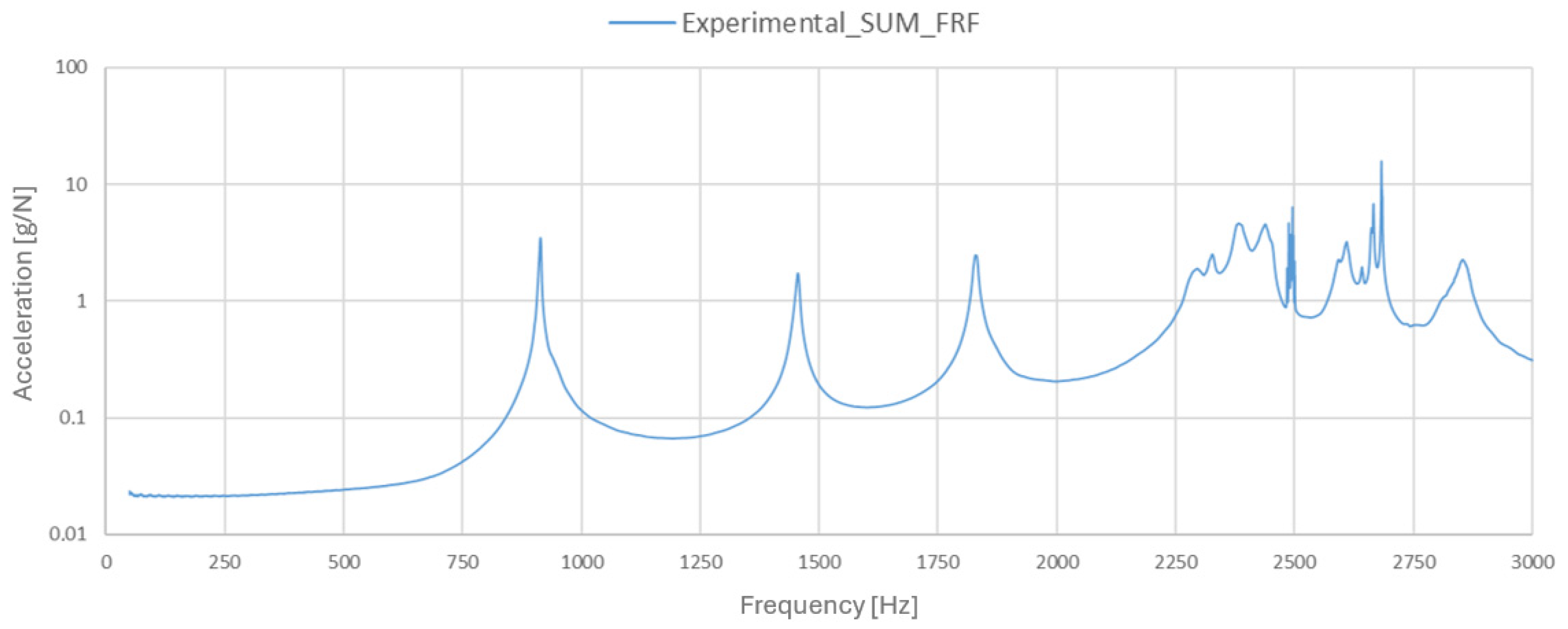

3. Results

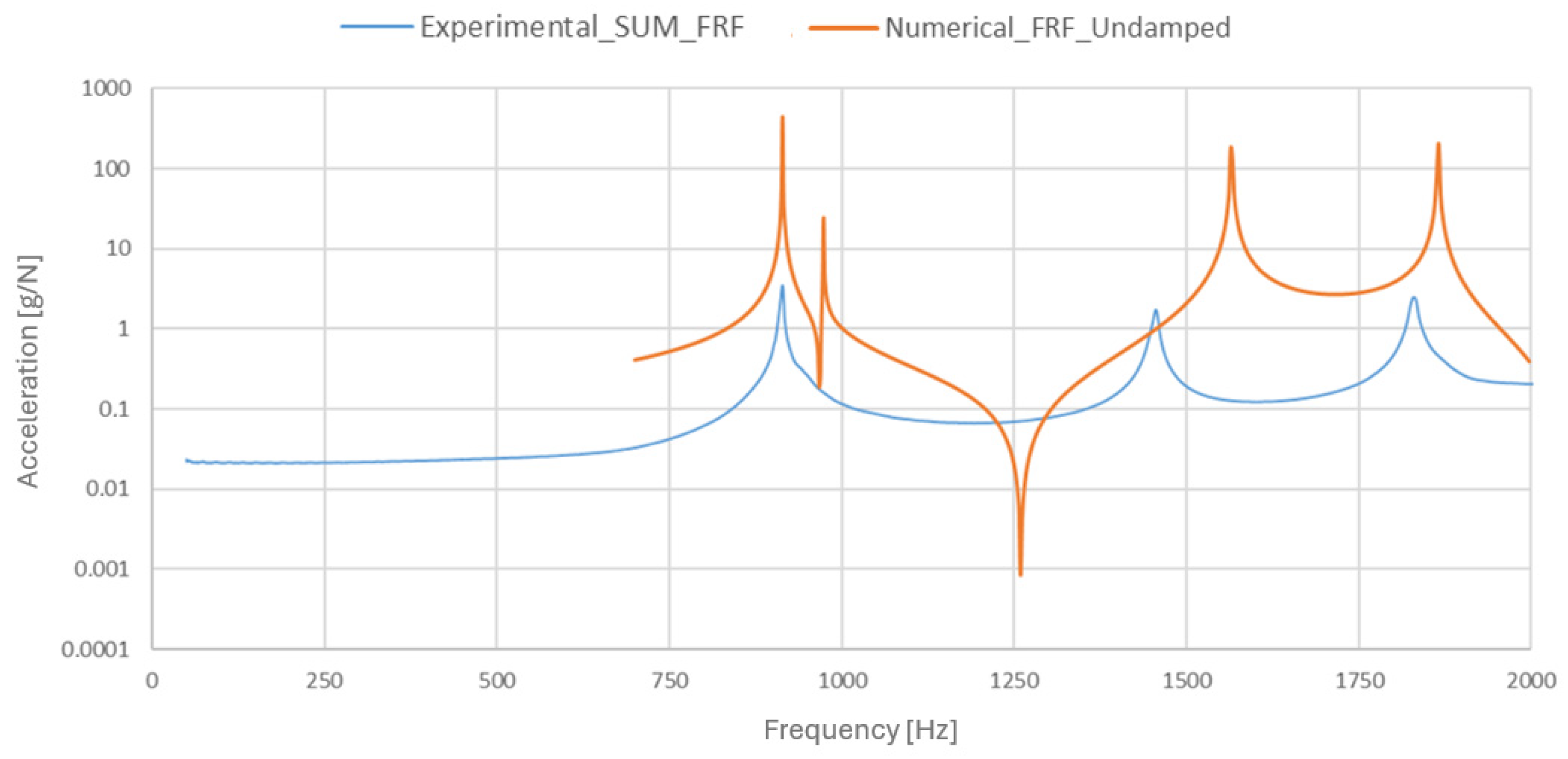

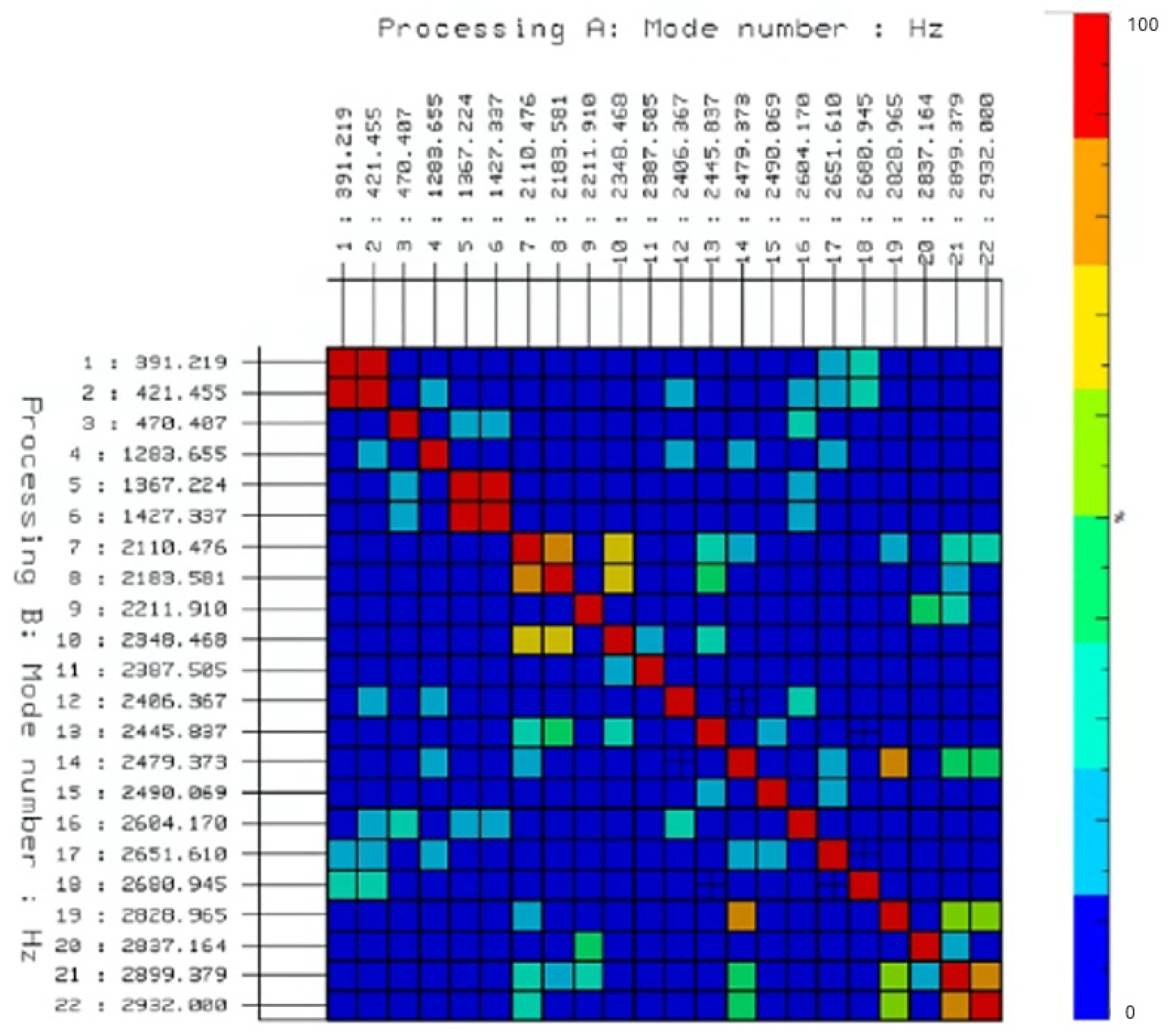

3.1. Preliminary Verification of the Burner Digital Twin

3.1.1. Free-Free Configuration

3.1.2. Constrained Configuration

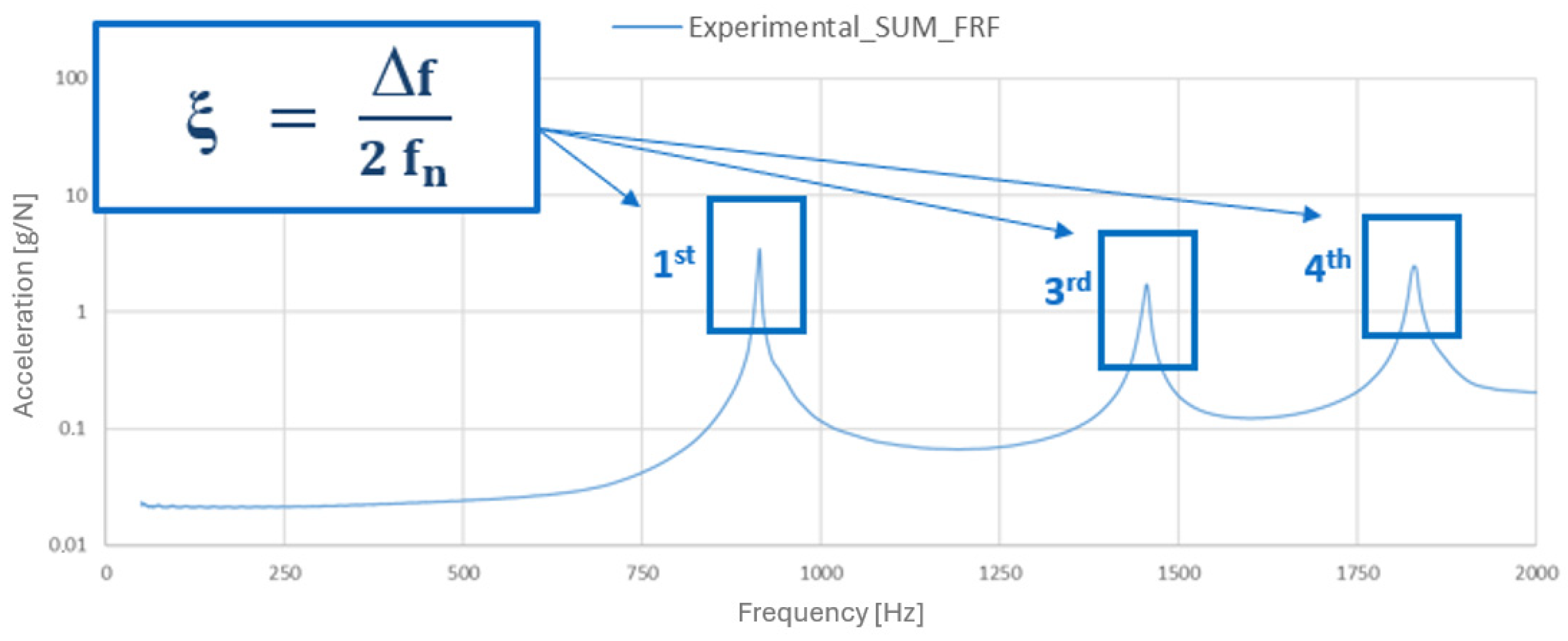

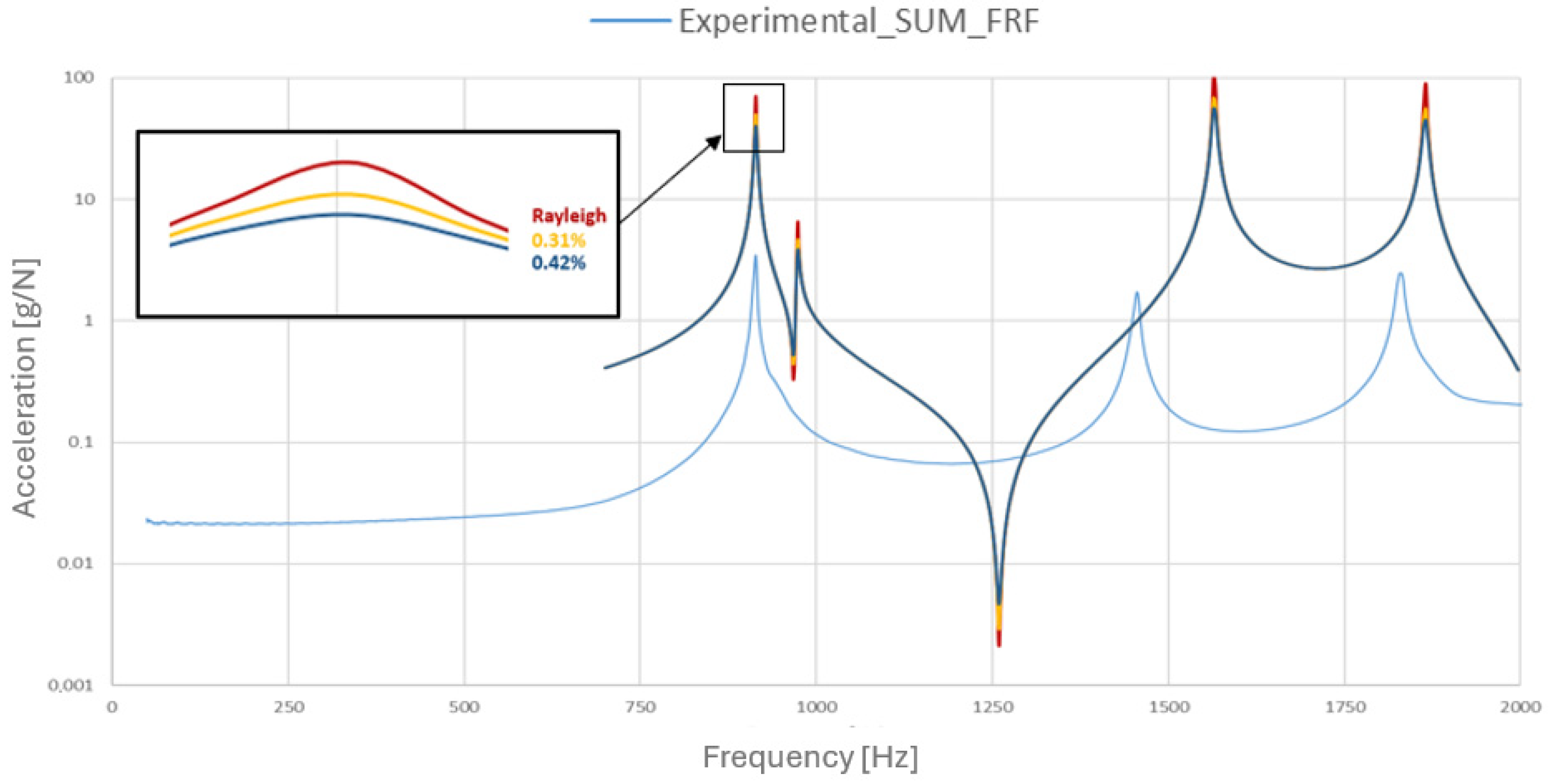

3.2. Structural Damping Estimation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clean Hydrogen Joint Undertaking. Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda 2021–2027; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking. Hydrogen Roadmap Europe: A Sustainable Pathway for the European Energy Transition; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. The Future of Hydrogen; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ETN Global. The Path Towards a Zero-Carbon Gas Turbine; ETN Global: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cocchi, S.; Provenzale, M.; Cinti, V.; Carrai, L.; Sigali, S.; Cappetti, D. Experimental Characterization of a Hydrogen Fuelled Combustor with Reduced NOx Emissions for a 10 MW Class Gas Turbine. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2008: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Berlin, Germany, 9–13 June 2008; Volume 3, pp. 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, M.; Pucci, E.; Romano, C.; Dabiru, V.R. Development of an Hydrogen Fueled Gas Turbine Combustion System From Conceptual Through Full Scale Verification Test. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2023: GT2023-102502, Boston, MA, USA, 26–30 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, D.R.; Zhang, Q.; Shareef, A.; Toothle, J.; Meyers, A.; Lieuwen, T. Syngas Mixture Composition Effects Upon Flashback and Blowout. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2006: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Barcelona, Spain, 8–11 May 2006; Volume 1, pp. 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, J.C.; Smith, T.D.; Kundu, K. Low Emission Hydrogen Combustors for Gas Turbines Using Lean Direct Injection. In Proceedings of the 41st IAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Tucson, AZ, USA, 13 July 2005; ASME. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20080002274 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Dodo, S.; Asai, T.; Koizumi, H.; Yoshida, S.; Inoue, H. Combustion Characteristics of a Multiple-Injection Combustor for Dry Low-NOx Combustion of Hydrogen-rich Fuels Under Medium Pressure. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 Turbo Expo: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–10 June 2011; Volume 2, p. 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, H.H.W.; Boerner, S.; Keinz, J. Experimental and Numerical Characterization of the Dry Low NOx Micromix Hydrogen Combustion Principle at Increased Energy Density for Industrial Hydrogen Gas Turbine Application. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2013: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 June 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, M.; Giannini, N.; Ceccherini, G.; Meloni, R.; Matoni, E.; Romano, C.; Riccio, G. Dry Low NOx Emissions Operability Enhancement of a Heavy-Duty Gas Turbine by Means of Fuel Burner Design Development and Testing. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2018: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Oslo, Norway, 11–15 June 2018; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti, M.; Cocchi, S.; Modi, R.; Sigali, S.; Bruti, G. Hydrogen Fueled Dry Low NOx Gas Turbine Combustor Conceptual Design. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2014: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Düsseldorf, Germany, 16–20 June 2014; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Meloni, R.; Cerutti, M.; Zucca, A.; Mazzoni, M. Numerical Modelling of NOx Emissions and Flame Stabilization Mechanisms in Gas Turbine Burners Operating with Hydrogen and Hydrogen-Methane Blends. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2020: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Online, 21–25 September 2020; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajadatz, M.; Güthe, F.; Freitag, E.; Ferreira-Providakis, T.; Wind, T.; Magni, F.; Goldmeer, J. Extended Range of Fuel Capability for GT13E2 AEV Burner With Liquid and Gaseous Fuels. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2019, 141, 051017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, R.; Babazzi, G.; Giannini, N.; Castellani, S.; Nassini, P.C.; Galeotti, S.; Picchi, S.; Becchi, R.; Andreini, A. Thickened Flame Model Extention For Dual Gas GT Combustion: Validation Against Single Cup Atmospheric Test. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 Turbo Expo: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, London, UK, 24–28 June 2024. GT2024-122234. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, N.; Orsino, S.; Meloni, R.; Pucci, E.; Castellani, S.; Andreini, A.; Valera-Medina, A. Large-Eddy Simulation of a Non-Premixed Ammonia-Hydrogen Flame: NOx emission and Flame Characteristics Validation. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 Turbo Expo: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, London, UK, 24–28 June 2024. GT2024-129248. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Lewis, E.; McDonell, V. Flameholding Tendencies of Natural Gas and Hydrogen Flames at Gas Turbine Premixer Conditions. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2014: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Dusseldorf, Germany, 16–20 June 2014; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, M.; Carta, R.; Cerutti, M.; Pucci, E.; Grosso, M.; Romano, C.; Sarti, G. NovaLTTM16 H2 Gas Turbine test campaign up to 100% H2. In Proceedings of the Gastech 2024 Technical Conference and Exposition, Houston, TX, USA, 17–20 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blakey-Milner, B.; Gradl, P.; Snedden, G.; Brooks, M.; Pitot, J.; Lopez, E.; Leary, M.; Berto, F.; Plessis, A.D. Metal additive manufacturing in aerospace: A review. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmon, J.; Raeisi, S.; Tovar, A. Review of additive manufacturing technologies and applications in the aerospace industry. Addit. Manuf. Aerosp. Ind. 2019, 209, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Yadaiah, N.; Prakash, C.; Ramakrishna, S.; Dixit, S.; Gupta, L.R.; Buddhi, D. Laser powder bed fusion: A state-of-the-art review of the technology, materials, properties & defects, and numerical modelling. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 2109–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.G. Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Process: State of the Art. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Tech. 2021, 8, 703–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, P.D.; Vijayananth, S.; Natarajan, M.P.; Jayabalakrishnan, D.; Arul, K.; Jayaseelan, V.; Elanchezhian, J. A current state of metal additive manufacturing methods: Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 59, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, M.E.; Gschweitl, M.; Ferrari, M.; Vernon, R.; Madera, I.J.; Yancey, R.; Mouriaux, F. Additive manufacturing of lightweight, optimized, metallic components suitable for space flight. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2017, 54, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caujolle, M. First Titanium 3D-Printed Part Installed into Serial Productionaircraft. 2017. Available online: https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2017-09-first-titanium-3d-printed-part-installed-into-serial-production#related-assets (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Bandini, A.; Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Pinelli, L.; Marconcini, M. Improving Aeromechanical Performance of Compressor Rotor Blisk with Topology Optimization. Energies 2024, 17, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, T.; Rimple, A.; Pelton, R.; Moore, J.; Wilkes, J.; Wygant, K. Manufacturing and testing experience with direct metal laser sintering for closed centrifugal compressor impellers. Turbomach. Pump Symp. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y. 3D-printing process design of lattice compressor impeller based on residual stress and deformation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, D.; Bichnevicius, M.; Lynch, S.; Simpson, T.W.; Reutzel, E.W.; Dickman, C.; Martukanitz, R. Design and evaluation of an additively manufactured aircraft heat exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 138, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, D.; Wits, W.W. The utilization of selective laser melting technology on heat transfer devices for thermal energy conversion applications: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 420–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Lin, X.; Kang, N.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Dang, C.; Huang, W. Solidification microstructure evolution and its correlations with mechanical properties and damping capacities of Mg-Al-based alloy fabricated using wire and arc additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 144, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M. Additive Manufacturing Technologies, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diegel, O.; Nordin, A.; Motte, D. A Practical Guide to Design for Additive Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, M.; Binda, M.; Harčarik, T. Modal Assurance Criterion. Procedia Eng. 2012, 48, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proso, U.; Slavič, J.; Boltežar, M. Vibration-fatigue damage accumulation for structural dynamics with non-linearities. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2016, 106, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraccini, M.; Di Sante, R. Measurement of nonlinear vibration response in aerospace composite blades using pulsed airflow excitation. Measurement 2018, 130, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozia, Z.; Zdanowicz, P. Simulation assessment of the half-power bandwidth method in testing shock absorbers. Open Eng. 2021, 11, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannopoulos, G.A.; Hatzigeorgiou, G.D. On the use of the half-power bandwidth method to estimate damping in building structures. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.S. A correction of the half-power bandwidth method for estimating damping. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2014, 85, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcenter Testlab Software. Available online: https://plm.sw.siemens.com/it-IT/simcenter/physical-testing/testlab/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Irvine, T. Effective Modal Mass and Modal Participation Factors. 2013. Available online: http://www.vibrationdata.com/tutorials2/ModalMass.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Waters, T. Vibration testing. In Fundamentals of Sound and Vibration; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 469–508. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, B.; Van Der Linden, P.; De Veuster, C. Performance of miniature shakers for vehicle component testing. In Proceedings of the IMAC, Dearborn, MI, USA, 19–22 January 2004; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, M.A.; Bono, R.W.; Avitabile, P. Effects of shaker, stinger and transducer mounting on measured frequency response functions. In Proceedings of the ISMA 2012 International Conference on Noise and Vibration Engineering, Leuven, Belgium, 17–19 September 2012; pp. 1475–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Gorman, D.G. Formulation of Rayleigh damping and its extensions. Comput. Struct. 1995, 57, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wang, D. Comparison of damping parameters based on the half-power bandwidth methods of viscous and hysteretic damping models. J. Vib. Control 2021, 29, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, T. The half power bandwidth method for damping calculation. Vibrationdata 2005, 1–8. Available online: https://www.vibrationdata.com/tutorials2/half_power_bandwidth.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

| FREE-FREE CONFIGURATION | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode Number | Numerical Frequency | Experimental Frequency | Relative Error |

| [-] | [Hz] | [Hz] | [%] |

| 1 | 914 | 915 | 0 |

| 2 | 973 | 932 | 4 |

| 3 | 1565 | 1455 | 7 |

| 4 | 1864 | 1830 | 2 |

| 5 | 2378 | 2288 | 4 |

| 6 | 2467 | 2325 | 6 |

| 7 | 2475 | 2378 | 4 |

| 8 | 2479 | 2385 | 4 |

| 9 | 2479 | 2441 | 2 |

| 10 | 2482 | 2487 | 0 |

| CONSTRAINED CONFIGURATION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical Modes | Numerical Frequency | Experimental Modes | Experimental Frequency | Error |

| [-] | [Hz] | [-] | [Hz] | [%] |

| Mode 1 | 425 | Mode 2 | 422 | 1 |

| Mode 2 | 487 | Mode 3 | 470 | 3 |

| Mode 3 | 1315 | Mode 4 | 1284 | 2 |

| Mode 4 | 1463 | Mode 5 | 1367 | 7 |

| Mode 5 | 2240 | Mode 7 | 2184 | 3 |

| Mode 13 | 2905 | Mode 21 | 2899 | 0 |

| FREE-FREE CONFIGURATION | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Frequency | Experimental ξ | HBM ξ |

| [-] | [Hz] | [%] | [%] |

| 1 | 915 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| 2 | 932 | 1.09 | - |

| 3 | 1455 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| 4 | 1830 | 0.21 | 0.33 |

| 5 | 2288 | 0.47 | - |

| 6 | 2325 | 0.19 | - |

| 7 | 2378 | 0.37 | - |

| 8 | 2385 | 0.34 | - |

| 9 | 2441 | 0.17 | - |

| 10 | 2487 | 0 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A.; Pucci, E.; Matoni, E. Experimental Validation and Dynamic Analysis of Additive Manufacturing Burner for Gas Turbine Applications. Machines 2025, 13, 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121111

Cascino A, Meli E, Rindi A, Pucci E, Matoni E. Experimental Validation and Dynamic Analysis of Additive Manufacturing Burner for Gas Turbine Applications. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121111

Chicago/Turabian StyleCascino, Alessio, Enrico Meli, Andrea Rindi, Egidio Pucci, and Emanuele Matoni. 2025. "Experimental Validation and Dynamic Analysis of Additive Manufacturing Burner for Gas Turbine Applications" Machines 13, no. 12: 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121111

APA StyleCascino, A., Meli, E., Rindi, A., Pucci, E., & Matoni, E. (2025). Experimental Validation and Dynamic Analysis of Additive Manufacturing Burner for Gas Turbine Applications. Machines, 13(12), 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121111