Abstract

Infrared spectroscopic analysis of palygorskite clay from the Dashkovskoye and Borshchevskoye deposits yielded key insights into the sedimentation conditions prevailing in the study area. In this paper, the composition, structure, and adsorption properties of smectite–palygorskite clays from the Steshevian sub-stage of the Lower Carboniferous (Russia) are investigated. The study applied X-ray diffraction, infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, assessment of cation exchange capacity by adsorption of [Cu(trien)2+], assessment of Cs sorption, and particle size analysis. It is demonstrated that the Al–palygorskite of the Dashkovskoye deposit was formed by sedimentation from suspended matter in a shallow-water basin in the Steshevian sub-age, despite a different genesis (chemogenic in the case of the palygorskites, clastic/redeposited in the case of the smectites). The palygorskites of the Borschovskoye deposit have a complex terrigenous genesis and were formed from redeposited chemogenic Al–palygorskites transported into the basin from the surrounding region of the Dashkovskoye deposit. With increasing depth of the basin in the Steshevian sub-age, the volume of incoming palygorskite material decreases, and the proportion of smectite material increases. The Fe–palygorskites entered the Borschovskoye deposit due to the redeposition of sediments from soils upstream of water flows. All the studied clays have considerable adsorption properties (32–49 mg-eq/100 g) and can be used in various industries.

1. Introduction

Smectite and palygorskite clays of the Moscow and Kaluga regions have been studied since the 1960s because they have high sorption capacity, colloidal properties, and good heat resistance. As is typical in geological research, particular attention was paid to the stratigraphic correlation and interpretation of the paleogeographic features of the Moscow syneclise [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The mineral composition was also considered in the works mentioned above. In particular, the study [6] employed an integrated approach with consideration of the mineralogical and technological characteristics of smectite and palygorskite clays. However, despite a detailed examination of the occurrences of the smectite and palygorskite outcrops, some aspects of the structure of these clay minerals were not covered in these studies. The current state of research equipment enables a fresh examination of the composition and structure of these clays, offering new insights into the genesis of the palygorskite and smectite clay deposits.

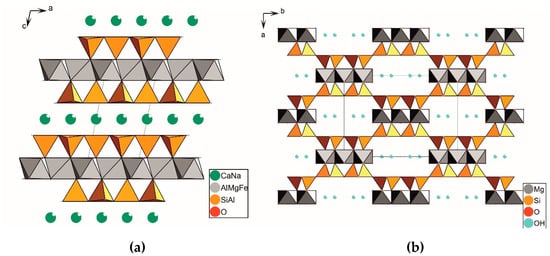

Smectite belongs to layered silicates. An elementary 2:1 layer of smectites consists of two tetrahedral sheets and an octahedral sheet enclosed between them (Figure 1a). A negative charge of the layer comes from isomorphic substitutions of cations in the octahedral sheet and, to a lesser extent, in the tetrahedral sheets. This negative charge is then neutralized by exchangeable interlayer cations (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, etc.), usually in a hydrated form [7,8,9]. Smectite is formed in various geological settings. It is most frequently the product of exogenous processes, such as the weathering of acidic eruptive rocks (predominantly volcanic ash) in an alkaline environment, as well as in various marine and continental conditions, in soils on various parent materials, etc. [10,11,12].

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the structure of smectite (a) and palygorskite (b). The dotted line defines the boundaries of the unit cell.

Palygorskite is a clay mineral with a ribbon-like and fibrous structure [13,14,15]. The basis of its structure consists of double silicon-oxygen tetrahedron chains, which are turned toward each other by their vertices (Figure 1b). These silicon-oxygen chains are connected into ribbons by means of the cations Al3+, Mg2+, Fe3+, and Fe2+, which have octahedral coordination [16,17,18,19,20]. This structural configuration of palygorskite results in the formation of channels. These channels have a cross-section of 3.7 × 6.4 Å and are typically filled with water molecules [13]. Palygorskite has a predominantly authigenic origin. Its formation typically occurs in closed basins enriched with Si, Al, and Mg [21,22].

The detailed composition and structure of palygorskite clays of the Moscow and Kaluga regions are less studied than those of smectitic clays and therefore deserve priority attention in this work. Authigenic palygorskite is far more common in geological formations than allothigenic palygorskite, which is rarely preserved. Therefore, the study of the peculiarities of the clay’s composition and structure makes it possible to identify the features of the formation of the studied deposits.

The main method for studying the crystal structure of clay minerals is usually X-ray diffraction. However, methods of infrared spectroscopy have emerged over the last few years. This makes it possible to obtain new data on isomorphic substitutions in the structure of palygorskites. The studies [23,24,25,26] provide extensive summary material, including data on palygorskites of various chemical compositions and geneses. They also introduce a new methodological approach proposed at the Theoretical and Physical Chemistry Institute (National Hellenic Research Foundation, Greece). This method makes it possible to determine the chemical composition of the octahedral sheets in the presence of possible mineral impurities (smectite and hydroxides of Al, Mg, and Fe). Such impurities can be used to clarify the genesis of palygorskite clays.

Smectite and palygorskite clays are known for their high adsorption properties. This leads to their widespread use as sorbents and isolation materials for highly toxic (including radioactive) wastes [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Although smectite–palygorskite mixed clays are of limited use, the central location of their deposits in the Moscow and Kaluga regions makes their use promising for a number of regional industries.

The main aim of the present study is to ascertain the genesis of the clays of the Steshevian sub-stage based on a detailed study of their mineral structure, as well as to evaluate their adsorption properties for industrial applications.

2. Geological Position of the Considered Deposits

The studied smectite–palygorskite mixed clays of the Russian Platform (Moscow and Kaluga regions), which belong to the Steshevian sub-stage of the Serpukhovian stage of the Lower Carboniferous, are overlain with nonconformity by argillaceous sandstones and dolomites of the Protvian and Zapaltyubian sub-stages of the Serpukhovian stage.

The Serpukhovian is developed on the East European Platform and belongs to the “Russian” stages of the international stratigraphic scale. The bed boundary of this stage and its paleogeographic interpretation are still not fully elucidated. The stratigraphic relationships of the known sections of the Serpukhovian stage and the problems associated with the correlation of their boundaries are described in detail [5]. The identification of the sedimentation features in the Steshevian sub-stage is important for the purpose of clarifying environmental processes. This importance stems from [37], who identified this period as marking a transition to high-amplitude, glacioeustatic sea-level fluctuations. Through a comparative analysis of the lithological and mineral composition, as well as the fossil record from the three most complete sections of the Serpukhovian stage of the East European Platform, the detailed work [5] makes important conclusions about the existence of a relatively shallow water basin with strong terrigenous migration. This migration is characterized by flowing rather than stagnant hydrodynamic regimes. In contrast, other earlier works reported the predominance of lagoonal conditions [38].

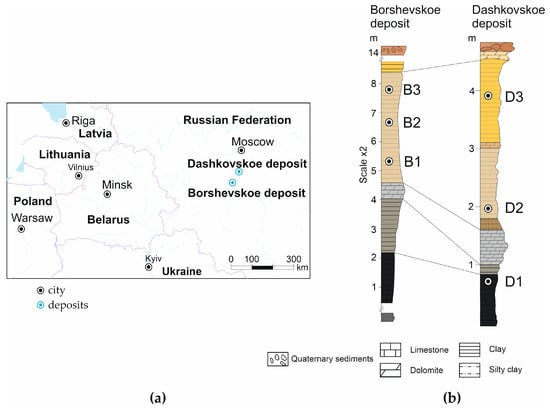

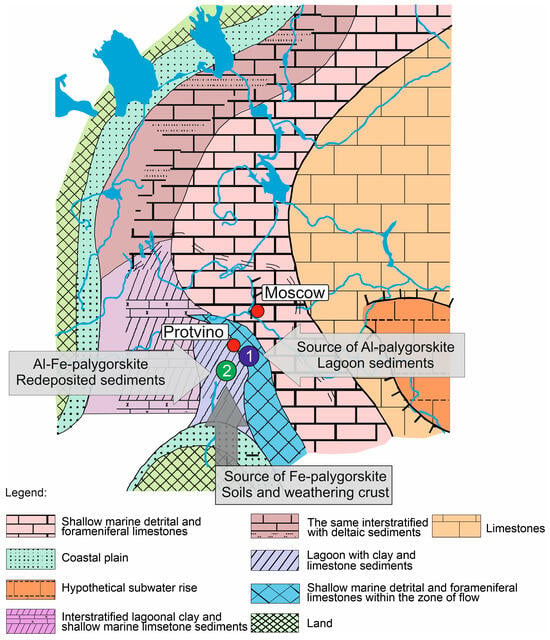

The Steshevian sub-stage is a stratum of clays with smectite predominant in the lower part, which is chocolate to dark gray and black in color. In the upper part, there is a relatively high content of palygorskite. The clay stratum has a light red to grayish yellow color with interlayers of dolomites. Generally, in the middle part of the section, there are variegated clays of mixed composition with interlayers of dolomites and limestones varying from several millimeters up to half a meter thick. The clays occur subhorizontally. The thickness of the layers varies from 2 to 4 m, reaching a total of 15 m. The boundaries with the overlying and underlying rocks are quite clearly traced by the change in the mineral and grain size composition. The features of changes in the mineral composition between the Dashkovskoye deposit in the Moscow region and the Borschovskoye deposit in the Kaluga region can be considered in more detail (Figure 2a). These deposits are in sufficient proximity to each other (approximately 100 km apart) to allow this comparison.

Figure 2.

Location of the studied deposits of smectite–palygorskite clays (a) and the lithological section of the Steshevian sub-stage of the Lower Carboniferous of the Moscow Oblast in the mining area of the Borschovskoye and Dashkovskoye deposits (b). The color matches the color of the rocks.

The Dashkovskoye deposit was exploited from the early 1970s for the extraction of smectite and palygorskite raw material. The quarry is now closed, and its operation has ceased. The bulk of the products made from the clay material were bentonite raw material for the production of drilling mud, as well as iron ore pellets.

The study of the Borschovskoye deposit also started in 1970. At that time, its explored reserves were estimated at seven million tons. Geological exploration carried out by the Lafarge Company in 2007 showed that the deposit’s reserves exceed ten million tons [6].

3. Materials and Methods

Samples from the Dashkovskoye (D) deposit were collected from cleared quarry walls during several field expeditions. For mineralogical studies, samples were taken vertically at intervals of 20–30 cm, maintaining natural moisture. Samples from the Borschovskoye (B) deposit were provided by the company “Lafarge SA” in the form of core material from different boreholes in sealed packaging.

In total, about 40 samples taken from the Dashkovskoye field and about 20 from the Borschovskoye field were studied. Based on the research results, 6 samples were selected that most fully characterize the various types of clays found in the deposits (Figure 2, Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the samples selected for detailed studies.

Determination of grain size distribution was carried out using sedimentation. Sample preparation was carried out according to the method of P.F. Melnikov (rubbing with sodium pyrophosphate) as described in [39].

Particle size distribution analysis in the fine fraction of clay samples was carried out using an ANALYSETTE 22 MicroTec Plus (Fritsch GmbH, Idar-Oberstein, Germany) laser analyzer in cooperation with the Moscow representative office of Fritsch. Before imaging with the laser analyzer, the samples were pre-dispersed by ultrasound for 5 min at a frequency of 44 kHz. For each sample, the measurements were repeated 20 times at intervals of several seconds, during which the samples were exposed to additional sonication for 10 s directly in the container of the device.

The microstructure of the clay samples was studied using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) LEO 1450VP (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). To preserve the natural structure of the samples, they were frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently vacuum freeze-dried. An electrically conductive thin film of gold (10–20 nm thick) was applied to investigate the surface of the finished samples using IB-3 (Eiko Engineering, Hitachinaka, Japan). This helps to avoid any charging effects on the sample during SEM analysis.

X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained using a Rigaku Ultima-IV X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) (Cu-Kα, detector D/Tex-Ultra, scan range 3–65° 2θ) from textured and untextured preparations. To obtain oriented samples, the suspension (fraction < 2 μm) was applied to a glass slide. The analysis of the results was carried out according to the recommendations described in [40]. Quantitative mineral analysis of bulk samples was carried out by the Rietveld method [41] in the PROFEX GUI software, 5.2.8 version package for BGMN [42].

The features of the crystal-chemical structure of the clay samples were studied using near- and mid-infrared (NIR and MIR) spectroscopy. The methods of NIR spectroscopy are the most sensitive for minerals with a fibrous structure, such as palygorskites, sepiolites, etc. The optimal temperature for the dehydration of zeolitic water from the channels in the structure of palygorskites is in the range of 80–100 °C. After the loss of this water, the structure contracts (“folds“), and a shift of the bands in the NIR spectra can be expected. This is the basis of the principle of studying palygorskites using dehydration, which was developed at the Theoretical and Physical Chemistry Institute [25]. NIR spectra were obtained using a Vector 22N FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA, USA), equipped with an external integrating sphere. The study sample was placed directly on a quartz window of the outer sphere and was protected from external influences by a box in the presence of P2O5. The use of a strong magnifying glass and a conventional incandescent lamp makes it possible to simulate heating conditions in the sample box. This leads to the loss of zeolitic water from palygorskite. Spectra are collected every minute until dehydration stabilizes. Some of the absorption bands in the NIR spectrum of palygorskites and other clay minerals, as well as oxides and hydroxides, are superimposed on each other or are in close spectral regions. As the sample dehydrates, the absorption bands from the changing structure of palygorskites shift, while the bands from the structure of other clay minerals present (in the case of the present study, smectites) only decrease in intensity. Thus, it is possible to confidently study the crystal-chemical features of the palygorskites mixed with other minerals (both clayey and non-clayey, such as iron oxides). The absorption bands in the near range have wide profiles; therefore, the second derivative of the absorption feature is used for a more correct determination of the position of the bands. The spectroscopy research experiments were carried out at the Theoretical and Physical Chemistry Institute, National Hellenic Research Foundation (Athens, Greece).

The cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined by the method of adsorption of methylene blue and a triethylene tetramine complex of copper (II) ([Cu(trien)]2+) [43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

The determination of the absorption properties with respect to Cs+ was carried out under static conditions on powdered samples with a particle size of <0.25 mm. The experiments were carried out in two parallel repetitions. Solutions of cesium nitrate (CsNO3) were prepared for the experiment at cesium concentrations of 50, 200, 350, 500, 700, 800, 900, 1000, and 1100 mg/L. Then, 200 mL of each solution of the aforementioned corresponding concentrations were poured into a series of flasks each containing a weighed quantity of the study sample weighing 2 g. The flasks with the resulting solutions were periodically mixed during the day. It was experimentally found that the optimal duration of contact of the adsorbent with the solutions of varying concentrations of cesium nitrate is one day (24 h). After the reaction time, solutions were filtered using blue ribbon filter paper. Measurement of the Cs concentrations in the original and equilibrium solutions was carried out on an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer Thermo Scientific Element 2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Adsorption isotherms were plotted after measurements.

4. Results

4.1. Mineral Composition

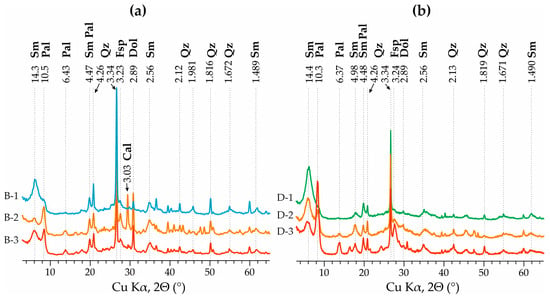

The content of smectite and palygorskite in the samples of the considered deposits is 20%–57% and 5%–55%, respectively (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Several patterns can be observed based on the detailed section of the Dashkovskoye deposit. The ratio of smectite and palygorskite varies along the section, from the predominance of smectite in the lower part (up to 82%) to the predominance of palygorskite in the upper part of the section (Figure 2 and Figure 3; Table 2). Smectite is present throughout the section. Simultaneously with an increase in smectite content, small amounts of illite impurity appear. Quartz, dolomite, calcite, and feldspars were noted as non-clay minerals. An admixture of quartz is present throughout the section, with its content fluctuating between 10% and 40%. Meanwhile, the content of quartz and palygorskite in the dolomite interbeds decreases sharply, while smectite is present in only trace amounts.

Figure 3.

Typical X-ray diffraction patterns of clay samples from the Steshevian sub-stage of the Dashkovskoye (a) and Borschovskoye (b) deposits.

Table 2.

Mineral composition of samples from typical clay layers.

The mineral composition of the clays from the Borschovskoye deposit is more heterogeneous (Table 2, Figure 3). This is reflected in a high content of quartz (25%–37%) and dolomite (up to 11%), calcite (up to 8%), and feldspars (up to 2%). The content of clay minerals is not constant and varies both laterally in different boreholes of the Borschovskoye deposit and vertically within the layers in the same borehole. The lithological differences identified at the Dashkovskoye deposit are also not regularly traced. This mineral composition refutes the hypothesis of the predominant chemogenic genesis of palygorskites in the area of the Borschovskoye deposit and suggests a redeposited origin of these clays.

The variation in mineral associations indicates a change in the conditions of sedimentation at the Steshevian sub-stage. Along with the prevalence of smectite, trace amounts of quartz, illite, and kaolinite are also present in the lower parts of the section. This may be the result of an intensification of the action of terrigenous migration. Although illite is found in small amounts, it clearly shows a correlation with the content of smectite and quartz: In strata with an increase in smectite, the content of quartz, illite, and kaolinite is also increased. Such an association of minerals indicates an intensification of the action of terrigenous outwash of material. At the same time, with an increase in the content of palygorskite, the presence of other clay minerals is suppressed. This is the result of a change in the conditions of sedimentation.

The MgO content changes in the same direction, which directly depends on the concentration of palygorskite in the clays. Such a significant increase in the MgO content in the paleobasin provides an opportunity for the chemogenic synthesis of palygorskite. With a continued increase in the MgO content and a decrease in the SiO2 content in the aquatic environment of the paleobasin, the conditions for the synthesis of palygorskite become unfavorable and the formation of chemogenic dolomite begins. In lithological terms, such dolomites are massive, uniform granular interbeds, similar in structure to poorly cemented sands. This was observed in the Dashkovskoye deposit quarry.

4.2. Crystal-Chemical Structure of Clay Minerals

Pure smectite or palygorskite was not detected in any of the analyzed samples from the deposits. Instead, all samples were composed of a mixture of different minerals. Obtaining fine fractions of different sizes (from 1 to 0.1 μm) also did not allow us to achieve mono-mineral samples. IR spectroscopy studies were carried out to clarify the crystal-chemical characteristics, such as the occupancy of octahedral and tetrahedral positions of palygorskites and smectites.

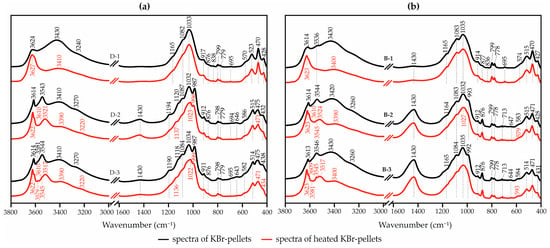

Investigations of the samples in the MIR spectrum allowed the confirmation of the conclusion about their mineral composition made on the basis of diffractometric analysis. The position of the Al–Al–OH bands in the range from 912 to 914 cm−1 (Figure 4) indicates the dioctahedral structure of both smectite and palygorskite [24,50]. Against the background of distinct bands of the matrix and in the region of hydroxyl groups, the bands of adsorbed water (~3400 and 1650 cm−1) stand out in the spectrum of the predominantly smectite sample (red line). The characteristic bands of zeolitic water in the structure of palygorskite are found in the range of 3270–3385 cm−1. Palygorskite can be characterized as low-magnesium (band at 3616 cm−1), dioctahedral, with a predominance of aluminum in octahedral positions (band at 3627 cm−1), and with a small amount of iron substitution in octahedral positions.

Figure 4.

Typical IR spectra of clay samples from the Steshevian sub-stage of the Dashkovskoye (a) and Borschovskoye (b) deposits of palygorskite and smectite samples.

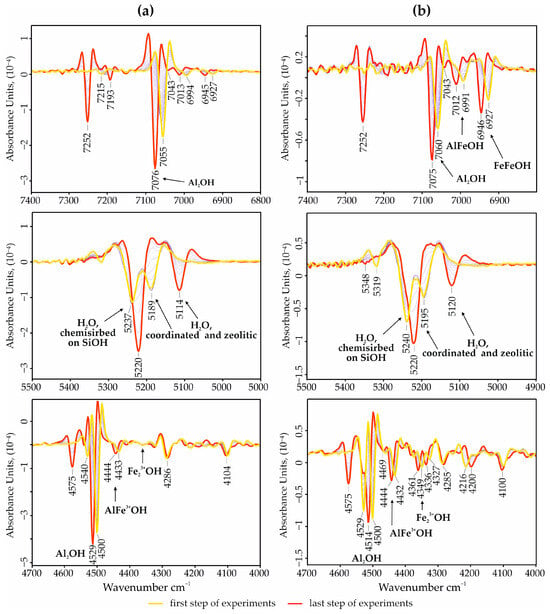

NIR spectroscopy studies of palygorskites make it possible to analyze a clay’s crystal-chemical composition, in particular, the isomorphic substitutions of Fe and Al in the structure of palygorskites. The relationship between zeolitic and coordination water and the nature of their behavior during heating is clearly illustrated in Figure 5. The Al–Al–OH bands are detected in the regions of 7075 and 4514 cm−1; Al–Fe–OH at 7012 and 4444 cm−1; and Fe–Fe–OH at 6946 and 4361 cm−1, respectively [23]. The ratio of the intensities of these bands allows us to assess the features of the distribution of iron in the octahedral positions. It turned out that in the palygorskites D-3, octahedral sites are mainly occupied by Al3+, while the content of isomorphic Fe3+ is insignificant. This indicates the homogeneity of all the studied palygorskites from this deposit. The palygorskites B (Figure 5b) belong to the aluminum–ferruginous variety, with a relatively high content of isomorphic Fe in the octahedral sheets. This is demonstrated by the relatively strong absorption bands of Fe–Fe–OH and Al–Fe–OH.

Figure 5.

The second derivative of the absorption spectra in the near-IR region of palygorskite-rich samples from the deposits: (a)—Dashkovskoye, (b)—Borschovskoye.

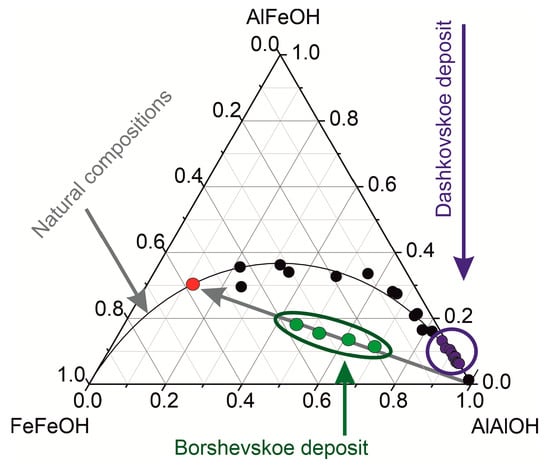

Based on the ratios of the intensities of Fe–Fe–OH, Al–Al–OH, and Al–Fe–OH bands, their relative abundances were calculated (assuming that the sum of the intensities I (Al–Al–OH), I (Al–Fe–OH), and I (Fe–Fe–OH) equals 1). The results are plotted on a triangular diagram (Figure 6). According to [25], the distribution of Al3+ and Fe3+ in the octahedral positions of all natural palygorskites follows a particular type of curve. It would be reasonable to assume that the samples that do not fall within this curve represent mechanical mixtures.

Figure 6.

Diagram of the ratio of Fe–Fe–OH, Al–Fe–OH, and Al–Al–OH bonds in palygorskite.

The palygorskites from the Dashkovskoye deposit follow this curve, meaning they represent pure natural Al–dioctahedral varieties without the presence of a significant admixture of other palygorskite varieties (of a different genesis). Based on the stability of the crystal-chemical composition of palygorskites along the section during the entire period of formation of the layer up to the Vereiskian time, we can conclude that the conditions for the chemogenic synthesis and deposition of clay material in the Steshevian sub-age in a shallow-water basin were stable.

In contrast to the palygorskites from the Dashkovskoye deposit, which were described above, all the compositions of the palygorskites from the Borschovskoye deposit are below the curve of natural compositions. By analyzing the locations of the Borschovskoye deposit points on the curve, it can be concluded that there are mainly Al–natural palygorskites and Fe–Al–palygorskites, with a significant predominance of isomorphic iron. Al–palygorskites were most likely formed under conditions similar to those of the Dashkovskoye deposit, and they likely have a chemogenic origin. Fe–Al–palygorskites have a distinctly different origin and were possibly formed in pedogenic conditions. Both of them were apparently transported to the sedimentation basin of the Borschovskoye deposit. Taking into account that the grain size distribution of the samples studied, it can be concluded that different sources of material were transported into the sedimentation basin. It is likely that the palygorskites in question came from different sources via different migration paths.

4.3. Grain Size Composition

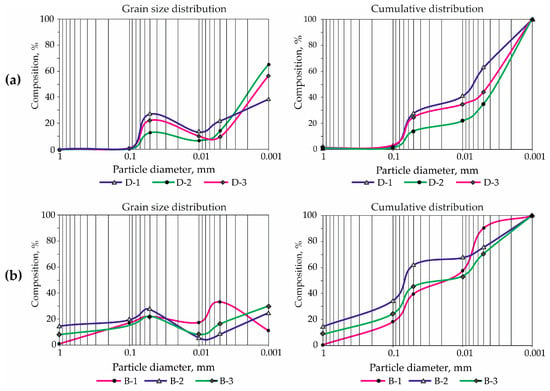

Despite the different mineral composition, the grain size composition of the D clays is uniform throughout the section. Specific convex cumulative curves are prevalent (Figure 7a), which correspond to slow sedimentation from a unidirectional water flow. These cumulative curves are characteristic of marine hemipelagic sediments on the continental slope, as well as of sediments in the deep-water part of deltas and lagoon basins with medium hydrodynamics [51].

Figure 7.

Grain size distribution and cumulative curves of the studied clays: (a)—Dashkovskoye deposit, (b)—Borschovskoye deposit.

The content of particles in the clay fraction (<5 µm) in samples D is more than 50% (Table 3). Particle size distribution across all three samples exhibits a consistent bimodal pattern, with a predominant mode in the fine clay fraction range. Nevertheless, there are clear regularities for different samples: in the predominantly smectite clay (D-1), the fine-silty mode is more pronounced, whereas the clay-fraction mode is less prominent. Conversely, the predominantly palygorskite clay exhibits a weaker fine-silty mode, but a stronger mode in the fine clay fractions. The smectite–palygorskite clay is characterized by the middle position of the fine-silt clayey mode (Figure 7).

Table 3.

Grain size composition of the studied clays.

The cumulative curves also show a high degree of similarity and appear as concave lines with a clear «plateau» in the silt-size area and a steep slope towards the fine fraction. Such a distribution of fractions in the D clay indicates the preservation of hydrodynamic conditions in the paleobasin during the formation of the deposits. At the same time, the gentle shapes of the cumulative curves indicate slow sedimentation and the action of a single factor in the sedimentation process. This could take place in a shallow basin, where fine terrigenous material is introduced by slow-flowing water, and the process of chemo-deposition of palygorskite minerals occurs.

The grain size composition of B clays exhibits specific differences, characterized primarily by a polymodal distribution with modes in the sandy, silty, and clay fractions, as well as by raised cumulative curves with numerous inflections. This pattern reflects the redeposited genesis of the sediments in the Borschovskoye deposit. The most prominent among the others is the stratum rich in palygorskite material, which came from a different source than the other clay and non-clay materials.

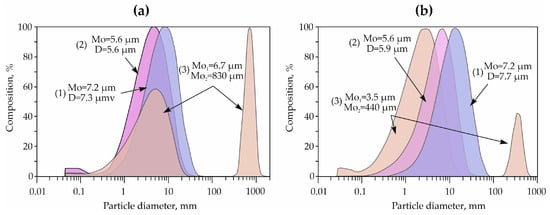

For a detailed study of the grain size composition of the finely dispersed part using laser diffraction, fractions < 5 μm from samples D-3 (predominantly palygorskite clay) and D-1 (predominantly smectite clay) were selected. The distribution of particles of the clay component in the samples D is characterized by a monomodal log-normal distribution, with an average particle diameter of 7.3 µm for the predominantly palygorskite sample and 7.7 µm for the predominantly smectite sample (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Features of the distribution of the grain size composition of the studied clays: (a)—sample of predominantly smectite clay D-1, (b)—sample of predominantly palygorskite clay D-3; Mo—mode, D—average size. 1—start of measurements, 2—measurements after 10 min of exposure to ultrasound, 3—measurements after 20 min of ultrasound.

Particles of clay minerals are sensitive to any mechanical treatment, including ultrasonic treatment, which is well evidenced by changes in the behavior of the spectra of the fractional composition (Figure 8). During several repetitions with additional sonication for 10 minutes, the prevailing average particle size (mode size) decreases from 7.3 to 5.6 μm for the predominantly palygorskite clay sample (D-3) and from 7.7 to 5.9 μm for the predominantly smectite clay sample (D-1). The number of particles < 0.3–0.5 µm in size also increases. With an increase in the time of ultrasound exposure to 20 minutes or more, the number of particles in the range of 5–7 μm decreases, and a second mode appears in the spectrum with an average diameter of 440–830 μm. This behavior of the spectra indicates that, under short exposure to ultrasound (10 min), there is a partial destruction of relatively low-strength large microaggregates ranging in size from 8 to 20 μm, resulting in the enrichment of the specimen with primary particles. Meanwhile, with an increase in the duration of ultrasound treatment, aggregation occurs with the formation of large secondary aggregates due to an increase in the static charge on the surface of the particles.

4.4. Micromorphology of Clays

The sample D-1 is characterized by the prevalence of smectite and by a predominantly laminar microstructure with elements of turbulence, which is clearly seen in Figure 9(a1,a2). The microstructure is represented by anisometric sheet microaggregates with a thickness of 2–10 μm and a length of 10 μm or more. The microaggregates are in contact according to the edge-to-edge type, merge into each other along the layering, and are composed of sharply anisometric sheet particles 30–50 nm thick and 1–4 μm long, also contacting according to the edge-to-edge type. The edges of the particles are ragged and curved. The void space of the sample is mainly represented by elongated intra-aggregate pores and, to a lesser extent, inter-microaggregate pores. The microstructure of sample B-1 was found to have many similarities with sample D-1. Nevertheless, Figure 9(b1) shows that B-1 contains substantially smaller microaggregates with less distinct particle features. Morphologically, the particles are less pronounced in B-1 than in D-1. Such differences in smectite micromorphology suggest that the B-1 clay is of redeposited origin.

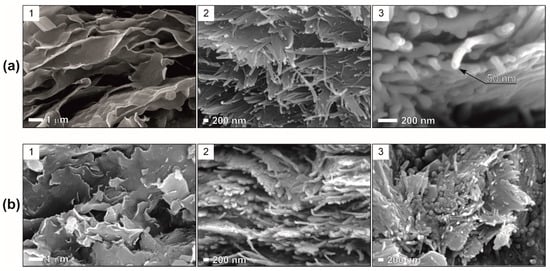

Figure 9.

Microstructure of samples of the Steshevian sub-stage, Moscow region: (a)—Dashkovskoye, (b)—Borschovskoye deposits. The predominant minerals are: 1—smectite, 2, 3—palygorskite.

The microstructure of the predominantly palygorskite clays (D-3 and B-3) (Figure 9(a2,a3)) is characterized by more noticeable laminarity. The size of the palygorskite particles in cross-section is 50–100 nm. Due to the tangled fibers, it is difficult to estimate the length of the particles precisely; the apparent length of individual particles reaches 1–10 μm. Elongated interaggregate pores are prevalent in the palygorskite samples. Furthermore, the proportion of intra-microaggregate pores is much lower than in the predominantly smectite clays. The main difference between the particles of palygorskite B is that the particles (aggregates of particles) are smaller, with less distinct morphology, and are often characterized by a shorter length when compared to the particles of palygorskite D.

Characterizing the microstructure of the samples studied in general, it should be noted that they are similar at relatively low magnifications (up to 1000×). Most likely, this is due to the fact that the sediment had an almost identical dispersed composition and underwent diagenetic transformations of the same nature. This is likely responsible for the similarity of the microstructure.

4.5. Adsorption Properties

The ability of clay materials to absorb various cations (including technogenic ones) is often used in industry to obtain various sorbents. Based on this, it is reasonable to evaluate the sorption properties of materials that can be used in industrial conditions. The clays of the Dashkovskoye deposit were previously mined in an open-pit operation and have the potential to be mined again; they are easily available on the mineral raw materials market and are distinguished by a relatively uniform mineral composition with a predominance of smectite or palygorskite. Therefore, they were chosen for the adsorption experiments presented below.

Determination of the CEC has several conventions that make the application of different methods fairly subjective [49]. For the selected samples, the CEC value was measured by adsorption of methylene blue (MB) and by [Cu(trien)]2+. Additionally, measurements were made for the clay fraction of the samples using the MB adsorption method (Table 4).

Table 4.

Indices of the sorption properties of the studied clays.

According to Table 4, the CEC values determined by the MB adsorption method are higher than those obtained with [Cu(trien)]2+. This is attributed to the polymerization of MB during the short interaction period. Although this process overestimates adsorption values, it simultaneously facilitates a more thorough characterization of sorption capacity in clay minerals, predominantly of the smectite group. Regardless of the analytical method employed, the CEC value of the studied samples is predominantly controlled by smectite content [46,52]. It can be expected that the relatively large MB molecules, being in an aggregated state, are unable to penetrate the channels of palygorskite; therefore, low CEC values tend to be observed in predominantly palygorskite clays.

At the same time, the specific surface area significantly increases in strata enriched in palygorskite, which is explained by the more developed inner surface of palygorskites (Table 4).

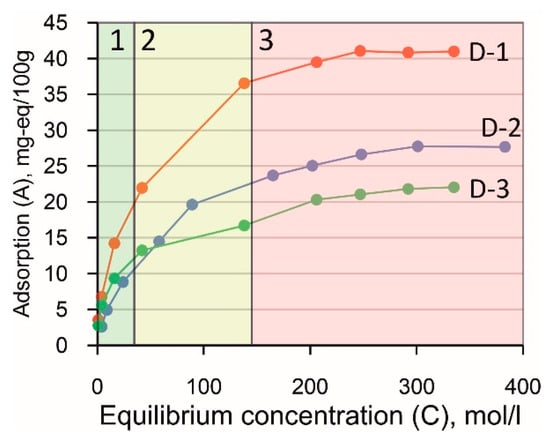

Experiments on the adsorption of Cs+ cations from aqueous solutions made it possible to reveal differences in the sorption properties of the selected samples. Three characteristic areas can be distinguished on the graphs (Figure 10):

- A linear part at low concentrations of the occluded cation;

- A non-linear transition section at intermediate concentrations;

- A curve that flattens off at high concentrations, corresponding to almost complete saturation of the adsorbent.

Figure 10.

Isotherms of Cs+ adsorption on clay samples from the Dashkovskoye deposit.

Thus, the isotherm of adsorption can be satisfactorily described within the framework of Langmuir’s theory of monomolecular adsorption. As a first approximation, the sample with the highest content of smectite (D-1) has the highest adsorption capacity. At the same time, adsorption capacity decreases with a decrease in the content of smectite. In order to calculate the value of the maximum adsorption (Amax) more accurately, it is necessary to graphically solve the Langmuir equation, for which the isotherms were plotted in the coordinates A/Cequiv = f(Cequiv).

Although CEC and Amax values show slight divergence, both decrease with declining smectite content. Higher CEC values should be associated with the tendency of MB cations to undergo multilayer adsorption on the surface of clay minerals. This is confirmed by spectrometric studies of the kinetics of its sorption, as well as by other studies [51]. In contrast, judging by the nature of the obtained isotherms, the Cs+ cations are prone to monolayer adsorption on these samples. The values of the adsorption equilibrium constant K characterize the interaction energy of the adsorbate with the adsorbent; in other words, the chemical affinity between them. Thus, we can conclude that the interaction of the Cs+ cations is energetically more favorable with the surface of smectite than that of palygorskite.

5. Discussion

The integration of all the results mentioned above made it possible to significantly supplement the history of the geological development of the region in the Steshevian sub-age (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Scheme of the distribution of precipitation and fauna during the Steshevian sub-age: 1—Dashkovskoye deposit, 2—Borschovskoye deposit, ref. [53] with additions.

An open sea covered the eastern part of the Russian platform (Volga–Ural region) throughout the Carboniferous period, while the Moscow syneclise constituted its western marginal zone, separated by islands or underwater uplifts. Increasing crustal uplift intensified the isolation of the Moscow syneclise basin, ultimately transforming it into a large lagoon [53]. The Steshevian sub-age was marked by significant changes in the conditions of sedimentation in the area under consideration. A stagnant lagoon with a relatively higher salinity formed in the southern part of the Moscow syneclise basin. It accumulated clay and dolomite silts. The lagoon was isolated from the open sea by shoals. Pronounced climatic aridization also impacted sedimentation: It affected the sedimentary dolomites in the lagoon, the palygorskite clay composition, and, according to [53], there was a decrease in TiO2 content in clays and the cessation of coal formation.

In the Steshevian sub-age, the basin was very shallow and turbid due to a large amount of incoming clayey matter. This statement is supported by specific faunal species found in sections of the same age in the Moscow region [4,5]. The introduction of smectite material prevailed at the initial stage of the formation of the basin. The terrigenous genesis of the layers with increasing smectite is confirmed by the simultaneous increase in quartz and illite.

Due to the intensity of the climactic aridity and the proportion of MgO, the active formation of palygorskite began. The clay minerals were deposited simultaneously and formed dense aggregates, which are clearly visible by SEM. With an increase in aridity and, as a consequence, shallowing of the basin, the supply of smectite ceased, and palygorskite predominated in the upper part of the section. Over time, as the aridity continued to increase, the MgO content significantly prevailed over Al2O3 and SiO2. As a result of this, layers of chemogenic dolomite were formed. By the end of the Steshevian sub-age, the basin had become extremely shallow throughout; the conditions of sedimentation changed, and terrigenous sedimentation began to prevail.

Following the end of the Steshevian sub-age, during the subsequent Protvian time, calcareous sediments accumulated in the southern part of this area, while sedimentary dolomites formed in the northwestern part [53]. Then calcareous marine sediments began to be deposited almost everywhere. At the turn of the Early and Middle Carboniferous epochs, the region dried up again for a long time. Lower Carboniferous carbonate strata underwent prolonged weathering and erosion. At an early stage of the Bashkirian age, the basal surface of the Lower Namyurian (Protvian sub-stage) deposits was probably covered by the sea. However, it is unknown how widely this basin was spread.

In the last few years, based on the results of a detailed study of paleontological remains, the features of sedimentation in the Lower Carboniferous have been clarified. The “Steshevian basin” was probably formed by a moderate input of thin terrigenous material ahead of the delta front and was not essentially a “lagoonal” basin [5]. The main difference in the opinion of the above authors is that the basin was not stagnant, as previously assumed by many authors, but had quite good mixing, with the inflow of oxygen and nutrients for the favorable development of organisms. At the end of the Steshevian sub-age, the Steshevian basin was practically filled in. At the same time, the continuing aridization of the climate increased the concentration of Mg and Si by evaporation in the shallow clay basin, which led to the deposition of palygorskite material.

A detailed study of the crystal-chemical structure of palygorskites (in particular the amount of isomorphic iron) made it possible to detail the scheme of the formation of palygorskites in the Moscow basin. It was revealed that Al varieties of the clay were formed as a result of chemical synthesis in a shallow saline basin, while Fe varieties were probably formed in soils and transferred to the sedimentation basin by rivers and water streams.

Thus, based on the studied clays, some refinements can be made to the previously described sedimentation schemes [5,6,53]. In addition, there were basins with a mixed type of sediments. As a result of the development of soil formation processes (as, for example, described for other basins of a similar age in [1,2,5]), palygorskites with a high Fe content in octahedral positions could form. Such palygorskites can be defined as end members in a series of mixtures of palygorskites of different composition in the Borschovskoye deposit. While most of the clay material in the sediments of the Dashkovskoye deposit has a local in situ origin, the clays of the Borschovskoye deposit were formed by sediment mixing with Al–palygorskites, which were carried in from the lagoon areas, and Fe–Al–palygorskites eroded from the surrounding soils. At the same time, the directions of the flows that brought the material could also differ quite significantly (Figure 11). Material enriched in Fe–Al–palygorskites has been transported by river flows from the nearby southern land, while material enriched in Al–palygorskite has come from the west as a result of seasonal fluctuations in sea level.

6. Conclusions

Comprehensive studies of the composition, structure, and properties of smectite–palygorskite clays of the Russian Platform (using sections of the Steshevian sub-stage of the Dashkovskoye and Borschovskoye deposits as examples) made it possible to detail their genesis and evaluate the prospects for their use as sorbents.

The content of smectite in the lower parts of the Steshevian sub-stage reaches 55%–57%. Homogeneous particle size distribution, micromorphological features, and an increase in the proportion of quartz and illite indicate that the smectite has a predominantly terrigenous genesis.

At the same time, palygorskites in the studied area are distinguished by various types of genesis:

1—the predominantly Al–palygorskites are characterized by chemogenic synthesis and would have formed in situ in lagoon conditions;

2—the Fe–(Fe–Al)–palygorskites also have a chemogenic genesis, but they were formed in pedogenic conditions in the presence of microbial communities.

In the sections of the Dashkovskoye deposit, only Al–palygorskites are found, and thus, it can be argued that this basin served as a source of chemogenic palygorskite. Meanwhile, palygorskites of mixed composition are encountered in the sections of the Borschovskoye deposit.

IR spectroscopy studies in the near-IR region allowed us to conclude that these palygorskites are represented by a mixture of Al–palygorskites and Fe–(Fe–Al)–palygorskites. That is, the clays of this basin have a terrigenous genesis, and the material came from different sources: from the erosion of material from the coastal areas of the lagoons with Al–palygorskites and from the erosion of soil areas with Fe–(Fe–Al)–palygorskites carried in by water flows.

It should be noted that the studied clays are quite old for bentonite and, despite this, retain a considerable sorption capacity. These clays could be utilized as sorbents in the future, but their properties are not yet comparable to those of established bentonite deposits (e.g., those in the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan [32,44]). The advantage of using smectite–palygorskite clays is convenient logistics and proximity to nearby enterprises located in the central part of the country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: V.K., S.Z. and O.Z.; Methodology: S.Z., O.Z. and V.K.; Formal analysis and investigation: S.Z., O.Z., M.C., I.M. and T.K.; Writing—original draft preparation: S.Z., O.Z. and V.K.; Writing—review and editing: M.C., O.Z. and T.K.; Funding acquisition: V.K.; Resources: V.K.; Supervision: V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The experimental studies were partially performed using equipment acquired with the funding of Moscow State University Development Program (X-ray Diffractometer Ultima-IV, Rigaku and Scanning Electron Microscope LEO 1450VP, Carl Zeiss). Mineral composition was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (project 16-17-10270). Investigation of adsorption properties was performed under a state assignment conducted by the Institute of Ore Geology, Petrography, Mineralogy and Geochemistry, Russian Academy of Science.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to JSC “Keramzit” https://www.zao-keramzit.com (accessed on 11 January 2026) and Lafarge SA for their assistance in conducting the work and in collecting samples for research. The authors thank Vassilis Gionis and Georgios Chryssikos (Theoretical and Physical Chemistry Institute, National Hellenic Research Foundation) for studying the samples using near-IR spectroscopy and for providing valuable comments on the text of the article; Vyacheslav N. Sokolov (Geological Faculty of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University) for his help in investigations of microstructure; Boris V. Pokidko (IGEM RAS) for his help in conducting research on the dispersion of clays; Ekaterina A. Tyupina (Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia) for her help in investigating surface properties, and Margarita L. Kuleshova and Zoya P. Malashenko for their help in the Cs adsorption experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| MIR | Mid-infrared |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| IR | Infrared spectroscopy |

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| MB | Methylene blue |

References

- Alekseeva, T.V.; Alekseev, A.O.; Kabanov, P.B.; Zolotareva, B.N.; Alekseeva, V.A.; Gubin, S.V. Carboniferous paleosols of the Moscow syneclise: Humic substances, mineralogical and geochemical properties. In Paleosols and Indicators of Continental Weathering and Biosphere History; Series “Geo-biological systems in the past”; PIN RAS: Moscow, Russia, 2010; pp. 76–94. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Alekseeva, T.V.; Alekseev, A.O.; Gubin, S.V. Paleosol Complex in the Uppermost Mikhailovian Horizon (Viséan, Lower Carboniferous) in the Southern Flank of the Moscow Syneclise. Paleontol. J. 2016, 50, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, T.V.; Alekseev, A.O.; Gubin, S.V.; Kabanov, P.B.; Alekseeva, V.A. Palaeoenvironments of the Middle—Late Mississippian Moscow Basin (Russia) from multiproxy study of palaeosols and palaeokarsts. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016, 450, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, P.B.; Alekseeva, T.V.; Alekseeva, V.A.; Alekseev, A.O.; Gubin, S.V. Paleosols in Late Moscovian (Carboniferous) marine carbonates of the East European Craton revealing “Great calcimagnesian plain” Paleolandscapes. J. Sediment. Res. 2010, 80, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, P.B.; Alekseeva, T.V.; Alekseev, A.O. Serpukhovian stage (Carboniferous) in type area: Sedimentology, mineralogy, geochemistry, and section correlation. Stratigr. Geol. Correl. 2012, 20, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasedkin, V.V.; Boeva, N.M.; Belousov, P.E.; Vasiliev, A.L. Geology, mineralogy, and genesis of palygorskite clay from Borshchevka deposit in the Kaluga region and outlook for its technological use. Geol. Ore Depos. 2014, 56, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenheim, S.; Adams, J.M.; Bain, D.C.; Bergaya, F.; Brigatti, M.F.; Drits, V.A.; Formoso, M.L.L.; Galan, E.; Kogure, T.; Stanjek, H. Summary of recommendations of Nomenclature Committees relevant to clay mineralogy: Report of the Association Internationale Pour L’etude des Argiles (AIPEA) nomenclature committee for 2006. Clays Clay Miner. 2006, 54, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.J. Rock-forming minerals. In Sheet Silicates: Clays Minerals; The Geological Society: London, UK, 2013; p. 724. [Google Scholar]

- Brindley, G.W.; Brown, G. Crystal Structures of Clay Minerals and Their Identification; The Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland: Twickenham, UK, 1980; p. 496. [Google Scholar]

- Belousov, P.; Chupalenkov, N.; Christidis, G.E.; Zakusina, O.; Zakusin, S.; Morozov, I.; Chernov, M.; Zaitseva, T.; Tyupina, E.; Krupskaya, V. Carboniferous bentonites from 10Th Khutor deposit (Russia): Composition, properties and features of genesis. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 215, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousov, P.E.; Krupskaya, V.V. Bentonite clays of Russia and neighboring countries. Georesursy 2019, 21, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, G.E. Genesis and compositional heterogeneity of smectites. Part III: Alteration of basic pyroclastic rocks—A case study from the Troodos Ophiolite Complex, Cyprus. Am. Mineral. 2006, 91, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Heaney, P.J. Synchrotron powder X-ray diffraction study of the structure and dehydration behavior of palygorskite. Am. Mineral. 2008, 93, 667–675. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.F.; Galan, E. Sepiolite and palygorskite. In Hydrous Phyllosilicates; Baily, S.W., Ed.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1988; Volume 19, pp. 631–674. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo, M.; Calvo, J.P. An overview of authigenic magnesian clays. Minerals 2018, 8, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, C.L.; Hathaway, J.C.; Hostetler, P.B.; Shepard, A.O. Palygorskite: New X-ray data. Am. Mineral. 1969, 54, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Drits, V.A.; Sokolova, G.V. Structure of palygorskite. Crystallography 1971, 16, 183–185. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, J.E. Powder diffraction patterns and structural models for palygorskite. Can. Mineral. 1992, 30, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Artioli, G.; Galli, E. The crystal structure of orthorhombic and monoclinic palygorskite. Mater. Sci. Forum 1994, 166–169, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan, E.; Carretero, I. A new approach to composition limits for sepiolite and palygorskite. Clays Clay Miner. 1999, 47, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, F.; Ammous, A.; Tlili, A.; Kallel, N. Geological setting, geochemical, textural, and genesis of palygorskite in Eocene carbonate deposits from Central Tunisia. Carbonates Evaporites 2024, 39, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefiev, M.P.; Shchepetova, E.V.; Pokrovskaya, E.V.; Shkurskii, B.B.; Nurgalieva, N.G.; Batalin, G.A.; Gareev, B.I. Palygorskite Mineralization in the Induan Sediments of the Moscow Syneclise as an Effect of Regional and Global Paleogeographic Changes at the Permian–Triassic Boundary. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2024, 519, 2196–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chryssikos, G.D.; Gionis, V.V.; Kacandes, G.H.; Stathopoulou, E.T.; Suárez, M. Octahedral cation distribution in palygorskite. Am. Mineral. 2009, 94, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, M.; Garcia-Romero, E. FTIR spectroscopic study of palygorskite: Influence of the composition of the octahedral sheet. Appl. Clay Sci. 2006, 31, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chryssikos, G.D.; Gionis, V.V. On the structure of palygorskite by mid- and near-infrared spectroscopy. Am. Mineral. 2006, 91, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Gionis, V.; Kacandes, G.H.; Kastritis, I.D.; Chryssikos, G.D. Combined near-infrared and X-ray diffraction investigation of the octahedral sheet composition of palygorskite. Clays Clay Miner. 2007, 55, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selin, P.; Leupin, O.X. The use of clay as an engineered barrier in radioactive-waste management—A review. Clays Clay Miner. 2013, 61, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, L.; Liang, W.; Chen, K.; Li, K.; Yan, R. Adsorption properties of cesium by natural Na-bentonite and Ca-bentonite. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2024, 333, 5347–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoueian, F.; Hosseini, S.F.; Seddighian, H.H.; Abdi, S.; Jalalian, Y.; Mashhadi, Y.B.; Oskoueian, E.; Karimi, E.; Jahromi, M.F.; Shokryazdan, P.; et al. Biological properties of activated bentonite vs. non-activated bentonite in mice fed an aflatoxin-contaminated diet: A comparative investigation. Mycotoxin Res. 2025, 41, 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Liang, D.; Yang, Z.; Gao, C.; Xie, J. Study on the influence of thermal aging on the swelling properties of GMZ bentonite. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupskaya, V.; Novikova, L.; Tyupina, E.; Belousov, P.; Dorzhieva, O.; Zakusin, S.; Kim, K.; Roessner, F.; Badetti, E.; Brunelli, A.; et al. The influence of acid modification on the structure of montmorillonites and surface properties of bentonites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 172, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupskaya, V.; Zakusin, S.; Zakusina, O.; Belousov, P.; Pokidko, B.; Morozov, I.; Zaitseva, T.; Tyupina, E.; Koroleva, T. On the Question of Finding Relationship Between Structural Features of Smectites and Adsorption and Surface Properties of Bentonites. Minerals 2025, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, Q. An efficient and recyclable palygorskite-supported palladium catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions in water at room-temperature. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2024, 137, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Matu, R.R.; Avilés, F.; Gonzalez-Chi, P.I. Water absorption kinetics of palygorskite nanoclay/polypropylene composite foams. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 4149–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyupina, E.; Kozlov, P.; Pryadko, A.; Krupskaya, V. Radioiodine Sorption on AgCl-modified Bentonite and its Stability in different Environments. Open Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 19, e18741231403108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.F.; Al-Bidry, M.A.; Wasiti, A.A. Investigation and evaluation of palygorskite microstructure following acid pretreatment and its potential use as an adsorbent for copper. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, W.J.; Montanez, I.P.; Gulbranson, E.L.; Brenckle, P.L. The onset of mid-Carboniferous glacio-eustasy: Sedimentologic and diagenetic constraints, Arrow Canyon, Nevada. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2009, 276, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zchus, I.D. Palygorskite from the Steshevsky horizon of the Moscow region basin. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1956, 107, 5. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- GOST 12536-79; Soils. Methods of Laboratory Granulometric (Grain-Size) and Microaggregate Distribution. Gosstandart of the USSR: Moscow, Russia, 1980.

- Moore, D.M.; Reynolds, R.C., Jr. X-ray Diffraction and the Identification and Analysis of Clay Minerals, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- Post, J.E.; Bish, D.L. Rietveld refinement of crystal structures using powder X-ray diffraction data. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 1989, 20, 277–308. [Google Scholar]

- Doebelin, N.; Kleeberg, R. Profex: A graphical user interface for the Rietveld refinement program BGMN. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufhold, S.; Dohrmann, R.; Ufer, K.; Meyer, F.M. Comparison of methods for the quantification of montmorillonite in bentonites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2002, 22, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousov, P.E.; Pokidko, B.V.; Zakusin, S.V.; Krupskaya, V.V. Quantitative methods for quantification of montmorillonite content in bentonite clays. Georesursy 2020, 22, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujdák, J.; Komadel, P. Interaction of Methylene-blue with reduced charge montmorillonite. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 9065–9068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czímerová, A.; Bujdák, J.; Dohrmann, R. Traditional and novel methods for estimating the layer charge of smectites. Clay Sci. 2006, 34, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, R.; Kaufhold, S. Three new, quick CEC methods for determining the amounts of exchangeable cations in calcareous clays. Clays Clay Miner. 2009, 57, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, P.; Meier, L.; Kahr, G. Determination of the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of clays minerals using the complexes of copper (II) ion with triethylenetetramine and tetraethylenepentamine. Clays Clay Miner. 1999, 47, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, R.; Genske, D.; Karnland, O.; Kaufhold, S.; Kiviranta, L.; Olsson, S.; Plötze, M.; Sandén, T.; Sellin, P.; Svensson, D.; et al. Interlaboratory CEC and exchangeable cation study of bentonite buffer materials: I. Cu(II)-triethylenetetramine method. Clays Clay Miner. 2012, 60, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russel, J.D.; Fraser, A.R. Chapter 2. Infrared methods. In Clay Mineralogy: Spectroscopic and Chemical Determinative Methods; Wilson, M.J., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1994; pp. 11–67. [Google Scholar]

- Krupskaya, V.V.; Andreeva, I.A.; Sergeeva, E.I. Clay minerals in bottom sediments of the Medvezhii Island region, Norwegian Sea. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 2004, 39, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching-Hsing, Y.; Newton, S.Q.; Norman, M.A.; Miller, D.M.; Schafer, L.; Teppen, B.J. Molecular dynamics simulation of the adsorption of methylene blue at clay mineral surfaces. Clays Clay Miner. 2000, 48, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipova, A.I.; Belskaya, T.N. On facies and paleogeography of the Serpukhov time in the Moscow basin. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 1965, 5, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.