Abstract

This study takes the Jiangligou Plutonic Complex (JPC) in the Western Qinling tectonic belt as the research object and systematically investigates the crystallization age, magmatic genesis, and tectonic setting of the plutons. Results indicate that the Jiangligou Plutonic Complex was formed during the Triassic period (252–216 Ma, corresponding to the “Indosinian” regional tectonic stage in East Asia). Six plutons are recognized in the Jiangligou region. Plutons IV (246 ± 3 Ma) and V (252 ± 2 Ma) record Early Triassic magmatism, and Plutons I (238 ± 1 Ma), II (216 ± 2 Ma), III (216 ± 2 Ma), and VI (224 ± 2 Ma) correspond to Middle-Late Triassic magmatic activity. Furthermore, the data from this study indicate that a Th/U ratio > 0.4 serves as a more effective criterion for identifying reliable magmatic zircons. Our data indicate that the Jiangligou Plutonic Complex represents a multi-stage magmatic system generated in response to the tectonic evolution of the West Qinling, spanning from the late subduction of the Mianlue Ocean to the peak collision between the North China and Yangtze blocks during the Indosinian orogeny. The region is dominated by a collisional setting, with magmas primarily derived from crustal remelting. This study provides key chronological and geochemical constraints on the Indosinian tectonic–magmatic evolution of West Qinling.

1. Introduction

Granite is a major component of the continental crust. Studies on its formation, genetic mechanism, and tectonic setting are crucial for revealing deep processes and dynamic evolution within orogenic belts [1]. The West Qinling tectonic belt is a key area for the amalgamation of the North and South China blocks, and it records multi-stage tectonic–magmatic activities from the Paleozoic to Mesozoic [1]. This belt is an important area for studying the interaction between the Tethyan, a giant ocean–orogen system that existed between the northern hemisphere’s Laurasia and the southern hemisphere’s Gondwana during the Mesozoic Era [2]. This system captures the full tectonic evolution of the Paleo-Tethys, Meso-Tethys, and Neo-Tethys Oceans—from expansion and subduction to closure—ultimately forming the “Tethyan Orogenic Belt Group” that spans southern Eurasia. Additionally, the Paleo-Asian Tectonic Domain was a massive tectonic system in northern Eurasia during the Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic [2].

The West Qinling tectonic belt stretches roughly in the E–W direction [3]. The intrusive complex is distributed along a nearly EW-trending zone in the northern part of this belt. The West Qinling tectonic belt trends east–west. The associated intrusive zone follows this trend, connecting the Tongren-Xiahe area on the western end to the Zhashui-Baoji area on the eastern end [3].

The Western Qinling region underwent a crucial tectonic transition from the Late Paleozoic to the Mesozoic, shifting from an active continental margin setting associated with the subduction of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean to an intracontinental orogenic setting linked to the collision between the North China and Yangtze plates [1]. This transition is specifically manifested in two key aspects: the change in magmatic activity from arc-type granites to collision-type granites and the shift in tectonic deformation style from compressional shear to regional uplift [1]. Magmatism in the West Qinling spanned a large age range but was concentrated in the early Mesozoic, particularly the Triassic (~252–201 Ma). This constitutes a large-scale regional magmatic event [4]. Previous studies on West Qinling granites have utilized petrography, rock geochemistry, zircon U–Pb geochronology, and zircon Hf isotopes, focusing on time formation, genesis, and tectonic affinity [4,5]. The intrusive complex in the Jiangligou area, on the northwestern margin of West Qinling, shows multi-stage intrusive characteristics [6]. Its close relationship with regional tectonic events makes it important for studying the Late Paleozoic to Mesozoic tectonic transition in the West Qinling [1].

To clarify the geological definition of “Jiangligou,” this study defines it as a tectonic–magmatic zone at the northwestern margin of the Western Qinling Orogenic Belt (in Tongren City, Qinghai Province). The primary research object is the “Jiangligou plutonic Complex,” composed of six plutons. These plutons exhibit distinct lithologies and ages (252–216 Ma), collectively revealing a history of multi-stage magmatic activity. This definition significantly differs from the view of Xu et al. [6], who regarded Jiangligou merely as a single porphyritic monzogranite Pluton, thus failing to encompass the gabbro (Pluton I), granodiorites (Plutons IV–VI), and multi-stage magmatism identified in this study. Although previous research on this area has utilized zircon U–Pb dating and rock geochemistry [5,6,7], controversies remain regarding its crystallization age and genesis. For instance, Sun et al. [5] reported a crystallization age of late Middle Permian (264 ± 1 Ma) for the Jiangligou granite, which is inconsistent with the Triassic ages obtained in this study through high-precision zircon U–Pb dating, indicating that the crystallization age requires further verification [5].

Regarding petrogenesis, Lu et al. [7] were the first to systematically report Late Triassic crystallization ages (229–217 Ma) for the porphyritic biotite monzogranite, granite porphyry, and fine-grained granite in this area. Based on evidence from zircon Hf isotopes and other data, they proposed that the primary magmas were derived from the mixing of partial melts from the lithospheric mantle and the Meso–Neoproterozoic crust [7]. Subsequent studies further suggested that the complex ultimately formed from these hybrid magmas through intense fractional crystallization [3,8]. Although previous studies have contributed significantly to understanding the characteristics of the Jiangligou complex [6,7,9,10], considering its close spatial and temporal correlations with nearby intrusive bodies, this study treats it as a unified Plutonic Complex for investigation. To precisely constrain its formation timing and potential source components (e.g., crustal remelting vs. mantle mixing), we applied an integrated approach combining high-precision isotope dating with multi-method geochemical analyses. Specifically, this includes thin-section petrographic identification, whole-rock major and trace element analyses, zircon U–Pb dating, and in situ Lu-Hf isotope analysis. These comprehensive datasets allow us to accurately determine the crystallization ages of individual plutons in the complex, reconstruct their magmatic evolution and possible source rocks, and, combined with the regional tectonic setting, deeply discuss their tectonic environment and genetic mechanisms.

2. Geological Background

The study area is located in the Jiangligou area, Tongren City (located at the northwestern margin of the Western Qinling, adjacent to the South Qilian Tectonic Belt), Qinghai Province (Figure 1). Its tectonic position is on the northwestern margin of the West Qinling [5,6,7]. The plutons intruded into the Paleozoic–Mesozoic strata. It is located at the junction of the West Qinling and South Qilian tectonic belts, implying a complex tectonic evolution [5,6,7,11]. During the Early Paleozoic, this region experienced the expansion of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean, accompanied by seafloor spreading and plate subduction [2]. From the Late Paleozoic to the Mesozoic, the closure of the Mianlue Ocean—an ancient marine basin in central China and a key component of the eastern Tethyan tectonic domain—directly governed the final amalgamation of the North China and Yangtze plates, and this process played a critical role in the formation of the Central Orogenic Belt and led to intensified regional tectonic deformation [6]. The JPC consists of multiple intrusive phases, whose main lithologies include porphyritic biotite monzogranite, gabbro, granite porphyry, and fine-grained granite. Transitional phases of granodiorite and diorite are distributed toward the southern part of the complex. Mafic microgranular enclaves are common [5,6]. Among the samples investigated in this study, the enclaves are hosted by the pluton rather than by the individual sample JLG-07. Mafic microgranular enclaves (MMEs) are typically formed during the crust–mantle material mixing process, indicating the incorporation of mantle-derived materials in the magma source region [5,9]. Its formation is closely related to the collisional orogenic process following the closure of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean; it is a product of crust–mantle mixing followed by high-degree differentiation, contributing significantly to regional mineralization [1,7].

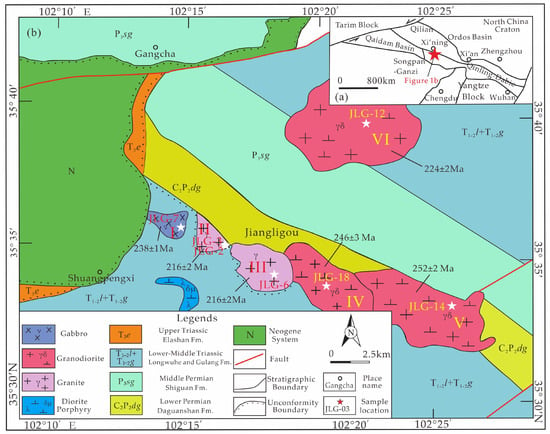

Figure 1.

(a) Simplified tectonic map of central–western China; (b) Regional geological map of the Jiangligou area (modified after Sun et al. [5]). From the lower left corner to the upper right corner, the Longwuhe Formation and Gulang Formation, Daguan Mountain Formation, Shiguan Formation, and Longwuhe Formation and Gulang Formation are developed in sequence. The study area exhibits an anticlinorium structure. Jiangligou Plutonic Complexes No. I, II, III, IV, V, and VI in the figure are our research targets, and they form a group of multi-stage intrusive complexes.

The study area lies within an NW–SE trending anticline (Figure 1b) [12]. The northern limb of the anticline exhibits a structural absence, specifically referring to the clastic rock strata of the Late Permian Daguan Mountain Formation (P3sg) [11]. Originally expected to be continuously distributed, these strata were disrupted and destroyed by the intense intrusion of Triassic granites. During the magmatic intrusion process, the high-temperature magma exerted dual effects of thermal erosion and mechanical compression on the strata of the northern limb: thermal erosion softened and melted parts of the rock, while mechanical compression further fractured and displaced the strata [11]. Consequently, a portion of the P3sg strata was either melted or replaced by the intruding magma, leaving only scattered rock fragments in the area, with the original continuous stratigraphic sequence completely disrupted by granite intrusion and subsequent modification [6,7]. The southern limb preserves a continuous stratigraphic sequence [11]. Structural deformation is mainly characterized by a densely developed fault system along both limbs of the anticline [13]. Magmatic intrusion is significant, dominated by Triassic Period granite–granodiorite series, forming the dominant intrusive assemblage (Figure 1b). The pluton contains multi-phase granitic bodies. Secondary small granite bodies often occur as parasitic stocks within the main pluton. They have a limited outcrop scale and a discrete spatial distribution [11].

Pluton I (Gabbro) is located in the northwestern part of the study area. It intrudes into the Longwuhe Formation and Gulang Formation (T1–2l + T1–2g) strata and is in contact with the Neogene strata in the west. Pluton II (Granite) is situated in the northwestern study area. It intrudes the Longwuhe Formation and Gulang Formation (T1–2l + T1–2g) strata, with contact to the Daguan Mountain Formation (C2P2dg) in the north. Pluton III (Granite) is distributed in the northwestern part of the study area. It intrudes the Longwuhe Formation and Gulang Formation (T1–2l + T1–2g) strata, contacting the Daguan Mountain Formation (C2P2dg) in the north and Pluton IV (Granodiorite) in the east. Pluton IV (Granodiorite) is located in the southeastern study area. It intrudes the Longwuhe Formation and Gulang Formation (T1–2l + T1–2g) strata, with northern contact to the Daguan Mountain Formation (C2P2dg), western contact to Pluton III (Granite), and eastern contact to Pluton V (Granodiorite). Pluton V (Granodiorite) is situated in the southeastern part of the study area. It intrudes the Longwuhe Formation, Gulang Formation (T1–2l + T1–2g), and Daguan Mountain Formation (C2P2dg) strata, contacting the Shiguan Formation (P3sg) in the north and Pluton IV (Granodiorite) in the west. Pluton VI (Granodiorite) is distributed in the northeastern study area. It intrudes the Longwuhe Formation, Gulang Formation (T1–2l + T1–2g), and Shiguan Formation (P3sg) strata.

Based on the analytical results of this study, we have made the following revisions to Figure 1, building upon previous work: The lithology of Pluton I has been revised to gabbro, Pluton III to granite, and Plutons IV, V, and VI to granodiorite. Pluton II represents a newly identified intrusive body in this area, recognized through field observations during this study. Pluton II and Pluton III may be interconnected; however, this potential connectivity remains unverified as the contact area is obscured by overlying strata.

3. Samples and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

Seven samples (JLG-06, JLG-12, JLG-14, JLG-02, JLG-03, JLG-07, and JLG-18) were collected for analysis. Samples were taken from gabbro, granodiorite, and granite bodies in the Jiangligou area (sampling locations in Figure 1, sample information in Table 1). Samples with weak alteration, fresh appearance, and good representativeness were collected from different locations. For discussion, the six plutons in the swarm in Jiangligou are numbered. The correspondence between sample names and pluton numbers is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample information from the Jiangligou area.

3.2. Methods

Thin section examination, whole-rock major and trace element analysis, zircon U–Pb dating, and in situ Lu–Hf isotope analysis were conducted on the seven samples. Thin section preparation and zircon separation were performed at the Laboratory of the Hebei Regional Geological Survey Team. Whole-rock major and trace element analysis, zircon U–Pb dating, and in situ Lu–Hf isotope analysis were conducted at the State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics, Northwest University, China.

Major whole-rock elements were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry (Rigaku RIX 2100, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with glass beads. A RIGAKU RIX2100 scanning automated X-ray fluorescence spectrometer was used. Analytical precision was better than 5%. Detailed instrument parameters and procedures are described in Wang et al. [14]. Whole-rock trace elements were analyzed using an Elan 6100DRC ICP-MS (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, USA). The analytical precision for Co, Ni, Ga, Zn, Rb, Hf, Zr, Y, Nb, Ta, and REE (except Hf and Lu) was better than 5%. Precision for other low-concentration elements ranged from 5% to 10%. The samples were pulverized to 200-mesh (<74 μm) using an agate jar planetary ball mill, which represents the standard pretreatment method for geological samples. The use of agate material effectively prevents heavy metal contamination, thereby ensuring the accuracy and long-term stability of trace element data in subsequent ICP-MS analysis and meeting the requirements of high-precision geochemical research. Sample preparation and analytical procedures follow Liu et al. [15]. Zircon U–Pb isotopic analysis was performed using LA-ICP-MS. An Agilent 7500a ICP-MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) coupled with a 193 nm ArF excimer laser was used. Helium was used as the carrier gas. Laser spot size was 32 μm. Laser pulse width was 15 ns. Detailed parameters and procedures are described in Yuan et al. [16]. U–Pb data were processed using ComPbCorr#3_15 for common Pb correction. 207Pb/206Pb, 206Pb/238U, 207Pb/235U, and 208Pb/232Th ratios were calculated using GLITTER (ver. 4.0, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia). Common Pb was corrected using the method of Andersen. [17]. Concordia diagrams and weighted mean calculations were performed using IsoplotR [18]. In situ Lu–Hf isotope analysis was conducted using a Nu Plasma HR multi-collector ICP-MS (Nu Instruments, Wrexham, UK). Analyses were performed on or near the spots used for U–Pb dating, guided by cathodoluminescence (CL) images. Instrument conditions, detailed analytical procedures, and data precision are the same as in reference [19]. Calculations for εHf(t), TDM1, TDM2, and fLu/Hf followed Wu et al. [20].

4. Results

4.1. Petrographic Characteristics

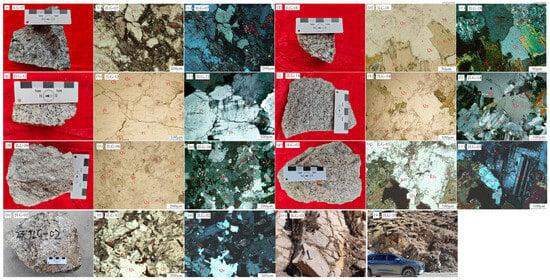

The JPC is located in the anticline axis. To the northwest outcrops a gabbro pluton (pluton I). A granite pluton (Pluton II, Pluton III) is exposed in the northwest, a granodiorite Pluton (Pluton VI) in the north, and granodiorite plutons (Pluton IV, Pluton V) in the southeast. Sample JLG-07 is a representative specimen of gabbro (Pluton I). Compared to other samples, its hand specimen exhibits a darker color with no distinct contrast between mafic and felsic minerals (Figure 2a). Plagioclase occurs as tabular euhedral to subhedral crystals (Figure 2b,c). Photomicrographs of sample JLG-07 reveal that the dominant mineral assemblage consists of plagioclase (Pl, ~60%), with clinopyroxene (Cpx, ~20%) as a minor phase. Biotite (Bt) is the principal mafic mineral, accounting for approximately 15% of the modal composition, while accessory minerals constitute approximately 5%. Samples JLG-18 (Pluton IV), JLG-14 (Pluton V), and JLG-12 (Pluton VI) are representative samples of granodiorite. Their hand specimens exhibit a clear contrast between dark- and light-colored minerals, and all display a medium- to coarse-grained texture (Figure 2d,g,j). Photomicrographs of sample JLG-18. Microscopic observations reveal a mineral assemblage of quartz (Qz, ~25%), plagioclase (Pl, ~45%), and biotite (Bt, ~25%). Quartz occurs as granular crystals, while biotite is present as flaky grains distributed within the plagioclase matrix. Accessory minerals constitute ~5% (Figure 2e,f). Photomicrographs of sample JLG-12. Microscopy shows the main mineral components are quartz (Qz, ~30%), plagioclase (Pl, ~40%), and biotite (Bt, ~25%). Biotite occurs as flaky grains with a preferred orientation. Accessory minerals account for 5% (Figure 2h,i). Photomicrographs of sample JLG-14. Under microscopy, the dominant minerals are quartz (Qz, ~35%), plagioclase (Pl, ~40%), and biotite (Bt, ~20%). Mineral grains are well-developed. Accessory minerals make up 5% (Figure 2k,l). Samples JLG-06 (Pluton III), JLG-03 (Pluton II), and JLG-02 (Pluton II) are representative samples of granite. Their hand specimens are predominantly light-colored overall, with distinctly visible reddish mineral grains, and all exhibit a medium- to coarse-grained texture (Figure 2m,p,s). Photomicrographs of sample JLG-06. Microscopic observations reveal the main mineral assemblage: quartz (Qz, ~35%), potassium feldspar (orthoclase, Kfs/Or, ~40%), and plagioclase (Pl, ~15%). Biotite (Bt, ~8%) occurs as flaky grains. Accessory minerals constitute ~2% (Figure 2n,o). Photomicrographs of sample JLG-03. Microscopy identifies the main minerals as quartz (Qz, ~30%), potassium feldspar (orthoclase, Kfs/Or, ~40%), and plagioclase (Pl, ~20%). Biotite (Bt, ~8%) is present as flaky grains. Accessory minerals account for ~2% (Figure 2q,r). Photomicrographs of sample JLG-02. Under microscopy, the main mineral components are quartz (Qz, ~35%), orthoclase (Or, ~30%), plagioclase (Pl, ~20%), and hornblende (Hb, ~10%). Mineral grains are well-formed. Accessory minerals make up ~5% (Figure 2t,u). The mineral compositions of the samples are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Hand specimens and photomicrographs of the Plutonic Complex in the Jiangligou area. (a) Hand specimen of sample JLG-07, (b) sample JLG-07 (−), (c) sample JLG-07 (+); (d) Hand specimen of sample JLG-18, (e) sample JLG-18 (−), (f) sample JLG-18 (+); (g) Hand specimen of sample JLG-12, (h) sample JLG-12 (−), (i) sample JLG-12 (+); (j) Hand specimen of sample JLG-14, (k) sample JLG-14 (−), (l) sample JLG-14 (+); (m) Hand specimen of sample JLG-06, (n) sample JLG-06 (−), (o) sample JLG-06 (+); (p) Hand specimen of sample JLG-03, (q) sample JLG-03 (−), (r) sample JLG-03 (+); (s) Hand specimen of sample JLG-02, (t) sample JLG-02 (−), and (u) sample JLG-02 (+). (v) Field geological outcrops of samples JLG-03; (w) Field geological outcrops of samples JLG-18; Pl: Plagioclase; Hb: Hornblende; Bt: Biotite; Kfs: K-feldspar; Qz: Quartz; Cpx: Clinopyroxene; and Or: Orthoclase. The “+/−” symbols indicate plane-polarized light and cross-polarized light.

Table 2.

Characteristics table of Jiangligou series samples.

The JPC as a whole displays a relatively distinct massive structure, accompanied by well-developed joints (i.e., fissures within the rock). Its surface remains relatively fresh, free from obvious coverage of weathered debris (Figure 2v,w).

4.2. Zircon U–Pb Dates and Hf Isotope Characteristics

To enhance data reliability, this study exclusively employs zircon age data that conform to systematically established morphological, textural, and geochemical criteria. The specific screening criteria include zircon crystals exhibiting euhedral to subhedral prismatic shapes, displaying typical magmatic oscillatory zoning in CL images, possessing Th/U ratios greater than 0.1, and plotting within the field of magmatic zircons in the La-(Sm/La)N diagram. These measures ensure that the obtained ages reliably represent the crystallization periods of the plutons.

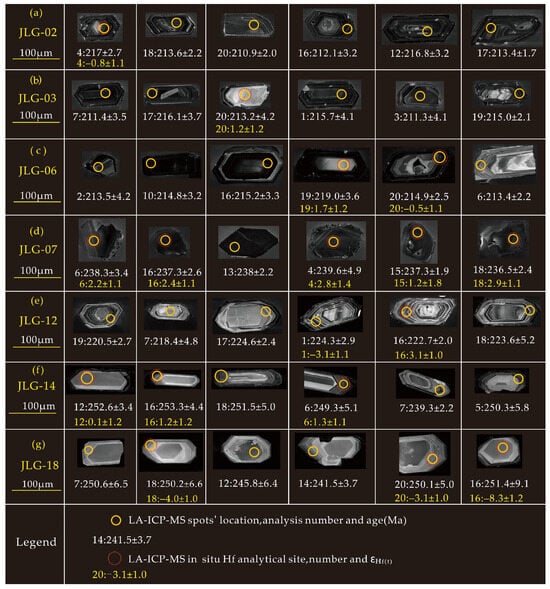

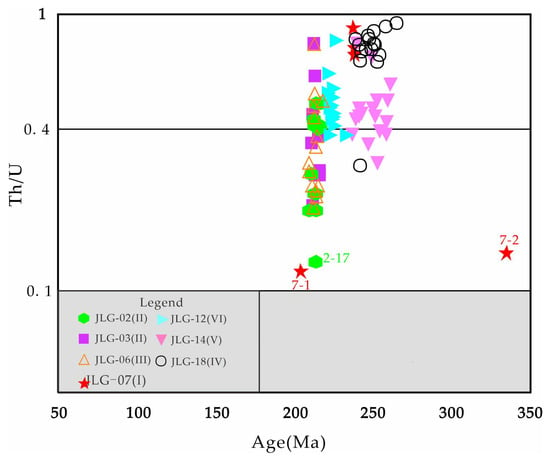

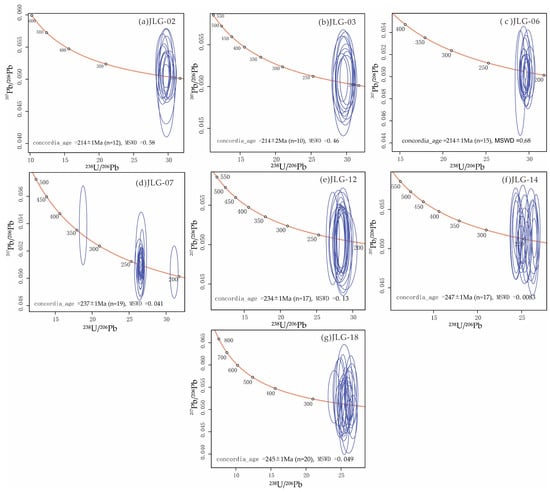

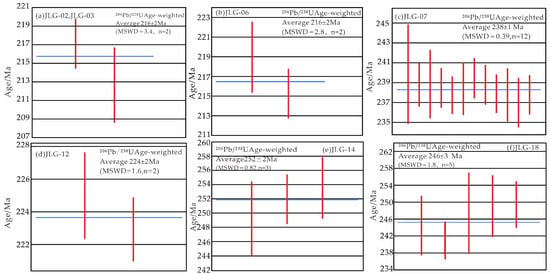

Zircon U–Pb dating was performed on seven samples (Supplementary Table S1). For Triassic samples, the 206Pb/238U ratio was primarily used for age calculations (Table S1). All obtained zircon dates were concordant (discordance ≤ 10%). Zircon grains are mostly euhedral prisms, 60–150 μm long and 40–70 μm wide, with aspect ratios of 1:1 to 2:1 (Figure 3). For JLG-02, JLG-03, JLG-06, and JLG-14, their lengths range from 70 to 150 µm, and their widths range from 50 to 60 µm. For JLG-07, JLG-18, and JLG-12, their lengths range from 60 to 110 µm, and their widths range from 40 to 70 µm. CL images show that most zircons have oscillatory zoning typical of magmatic origin (Figure 3), and their Th/U ratios are generally greater than 0.1 (Figure 4). Some zircons show sector zoning in CL images, with Th/U ratios between 0.1 and 0.4 (Figure 4). Some zircons have core–rim structures, exhibiting a “core + mantle” concentric structure, with rims showing weak luminescence in CL images (Figure 3f (18 spots)).

Figure 3.

Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of representative zircons (dates shown are 206Pb/238U ages after common Pb correction, and the uncertainties are reported at the 2σ).

Figure 4.

Plot of U–Pb age vs. Th/U ratio for analyzed zircons. Zircon JLG-07-1; Zircon JLG-07-2; Zircon JLG-2-17.

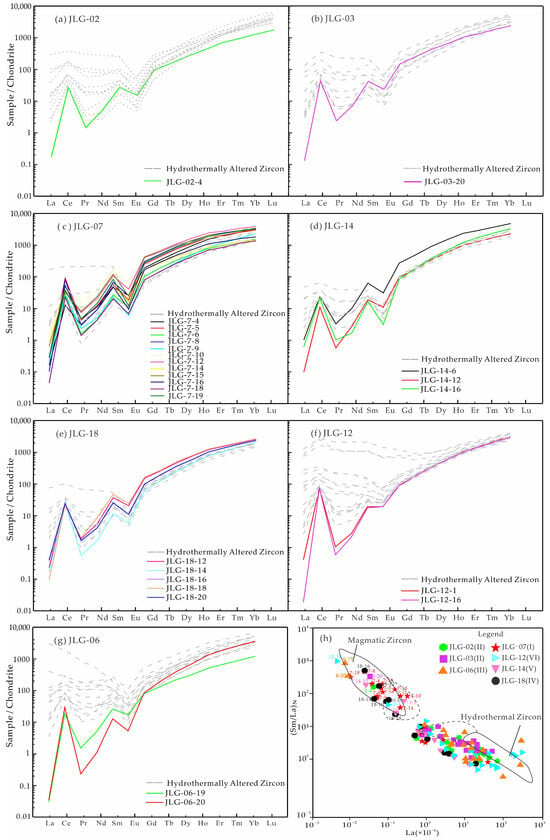

The rare earth element (REE) partitioning characteristics and genetic discrimination results of zircons in the study area (Figure 5). In the chondrite-normalized REE distribution patterns (Figure 5a–g). All zircon samples exhibit significant enrichment in heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) and depletion in light rare earth elements (LREEs), presenting a left-leaning pattern with pronounced positive Ce anomalies and negative Eu anomalies. Additionally, the patterns of most samples differ distinctly from the reference line for “hydrothermally altered zircons.” These partitioning characteristics correspond to the results in Figure 2h, where all sample points are concentrated within the “magmatic zircon” region and do not fall into the hydrothermal zircon field.

Figure 5.

(a–g) Chondrite-normalized REE patterns for zircons [21], (h) La vs. (Sm/La)N diagram for zircons (modified after Hoskin [22]).

For sample JLG-02 (Pluton II), twelve concordant zircon dates were obtained, ranging from 217.0 to 209.4 Ma. For sample JLG-03 (Pluton II), ten zircon spot analyses were conducted, ranging from 216.1 to 210.9 Ma. For sample JLG-06 (Pluton III), fifteen zircon spot analyses were conducted, ranging from 219.0 to 210.2 Ma. For sample JLG-07 (Pluton I), nineteen zircon spot analyses were conducted. Among them, two zircons had abnormal dates, with dates of 203.8 Ma and 334.8 Ma, respectively. The remaining concordant zircons yield ages ranging from 239.6 to 236.1 Ma. For sample JLG-12 (Pluton VI), seventeen zircon spot analyses were conducted, ranging from 232.2 to 218.4 Ma. For sample JLG-14 (Pluton V), seventeen zircon spot analyses were conducted, ranging from 261.3 to 237.1 Ma. For sample JLG-18 (Pluton IV), twenty zircon spot analyses were conducted, ranging from 257.7 to 238.5 Ma (Table 3). The zircon numbers are listed in Table S1. Concordant dates plot near or on the concordia curve (Figure 6).

Table 3.

LA-ICP-MS U–Pb isotopic data for concordant zircon spots from the Jiangligou area.

Figure 6.

Zircon U–Pb concordia diagrams for samples.

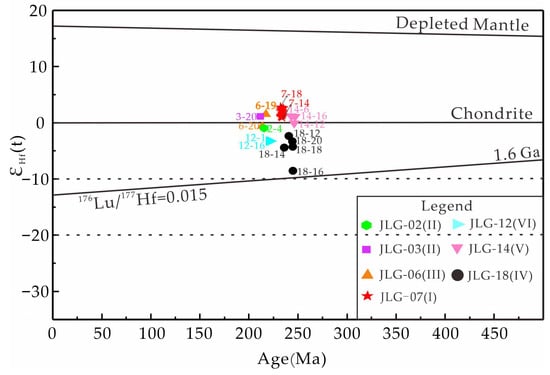

In situ Lu–Hf isotope analysis was performed on 26 zircons (Table S2). All zircon εHf(t) values range from −8.3 to 2.9 (Figure 7). Pluton II (JLG-02) has an εHf(t) value of −0.80 and a TDM2 age of 1299 Ma. Pluton II (JLG-03) yields an εHf(t) value of +1.23 and a TDM2 age of 1168 Ma. For Pluton III (JLG-06), εHf(t) values range from −0.52 to +1.67, with TDM2 ages between 1144 and 1280 Ma. Pluton I (JLG-07) shows εHf(t) values varying from +1.08 to +2.91 and TDM2 ages ranging from 1079 to 1196 Ma. Pluton VI (JLG-12) exhibits negative εHf(t) values of −3.13 and −3.09, with TDM2 ages approximately between 1448 and 1451 Ma. The Pluton V (JLG-14) has εHf(t) values ranging from +0.09 to +1.29 and TDM2 ages from 1191 to 1270 Ma. Pluton IV (JLG-18) demonstrates a relatively wide range of εHf(t) values, from −8.32 to −2.15, and corresponding TDM2 ages between 1406 and 1798 Ma. Based on a multi-interval classification scheme, within analytical uncertainty, the εHf(t) values are categorized as follows: negative interval (−8.3 to −2, 23% of analyzed zircons) with TDM2 model dates from 1448 to 1798 Ma (average 1538 Ma); transitional interval (−2 to 0, 23% of analyzed zircons) with TDM2 model dates from 1168 to 1406 Ma (average 1233 Ma); positive interval (0 to +2.9, 54% of analyzed zircons) with TDM2 model dates from 1079 to 1299 Ma (average 1160 Ma) (Figure 7 and Table S2).

Figure 7.

Plot of zircon U–Pb age vs. εHf(t). 7–18: zircon grain 18 from sample JLG-7.

The magmatic zircon dates selected (discussion in Section 5.1) in this study (252–216 Ma) can represent the formation period of the JPC and are applicable for investigating the Triassic tectonic–magmatic evolution of the West Qinling. The Hf isotopic data (εHf(t) = −8.3 to –2.9) can be used to constrain the crust–mantle mixing proportions of the magma source [23].

4.3. Major Element Characteristics

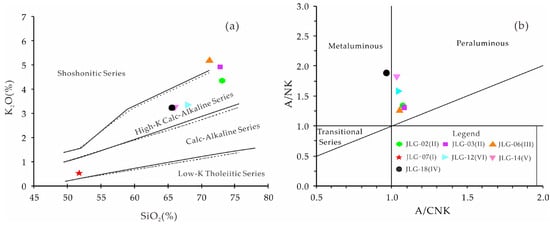

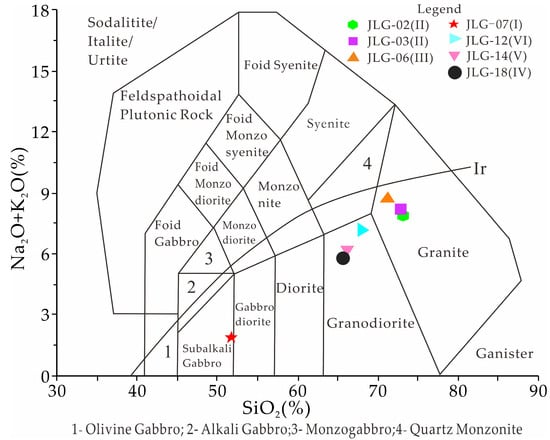

Results of major element analysis are listed in Table S2. SiO2 content of the intrusive complex ranges from 51.8% to 73.2%. Sample JLG-07 has relatively low SiO2 (51.8%), is alkali-poor (Na2O + K2O = 1.9%), has low K2O/Na2O (0.4), and high TiO2 and MgO. On the SiO2 vs. K2O diagram (Figure 8a), all samples except JLG-07 and JLG-06 plot in the high-K calc-alkaline series field. JLG-07 plots in the calc-alkaline field. JLG-06 plots in the shoshonite field. With increasing degrees of differentiation, mafic minerals (such as pyroxene and amphibole) crystallize and separate early from the magma, removing non-silicate components like MgO and CaO. This process leads to the relative enrichment of silica in the residual melt. For instance, in the undifferentiated sample JLG-07 (gabbro), the MgO and CaO contents are 9.8% and 13.9%, respectively, corresponding to a SiO2 content of only 51.8%. In contrast, the highly differentiated sample JLG-02 (granite) shows a significant decrease in MgO (0.5%) and CaO (1.5%), while its SiO2 content increases to 73.2%. Furthermore, SiO2 exhibits a strong negative correlation with both MgO and CaO (Table 4), consistent with the process of “mafic mineral crystallization to silica enrichment” during magmatic differentiation [24]. This may indicate magmatic fractional crystallization.

Figure 8.

(a) SiO2 vs. K2O diagram (base map after Rickwood et al. [25]); (b) A/CNK vs. A/NK diagram (after Maniar et al. [26]). In (a) solid lines indicate higher reliability, while dashed lines indicate lower reliability.

Table 4.

Statistical parameters of major, trace, and rare earth elements for samples.

On the A/CNK vs. A/NK diagram (Figure 8b), sample JLG-07 has an extremely high A/NK value (4.92) and A/CNK = 0.50, plotting outside the diagram area. Combined with the loss on ignition (LOI: 1.47%, Table 4) and thin-section observations (clay mineral content < 1%), intense weathering is ruled out. Sample JLG-07 exhibits distinct geochemical features, including the lowest SiO2 and Na2O contents, alongside a relatively high Sr content compared to other plutons (Table 4). JLG-18 has an A/CNK value of less than 1, falling within the metaluminous field (Table 4, Figure 8b). The other five samples plot in the peraluminous field. A/CNK ranges from 1.03 to 1.08. A/NK ranges from 1.27 to 1.84.

Pluton I (JLG-07) plots in the subalkaline gabbro field on the TAS diagram (Figure 9) and is characterized by low alkali and low sodium contents (Na2O + K2O = 1.89%, K2O/Na2O = 0.39), high MgO content (9.84%), and high CaO content (13.86%). Samples JLG-02, JLG-03, and JLG-06 are plotted in the granite field. They have relatively high SiO2 (71.3%–73.2%), are alkali-rich (Na2O + K2O = 7.9%–8.7%), have variable K2O/Na2O (0.24–1.51), and low TiO2 and MgO. Samples JLG-12, JLG-14, and JLG-18 plot in the granodiorite field (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

TAS classification diagram (modified from after Middlemost [27]).

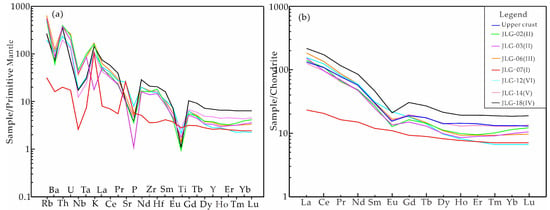

4.4. Trace Element and Rare Earth Element Characteristics

Trace element contents of the Plutonic Complex vary significantly (Figure 10a and Table 4). All seven samples are relatively enriched in strongly incompatible and large ion lithophile elements (LILE). They are depleted in high field strength elements (HFSE), notably Nb patterns show Rb, Th, and U peaks and Ti troughs. It may exhibit trace element characteristics indicative of a continental crustal material source [28]. The significantly lower trace and REE contents of sample JLG-07 (Figure 10a and Table S3) are consistent with its classification as subalkali gabbro in the TAS diagram (Figure 9). Its primitive mafic composition (low SiO2 and total alkali contents) and mantle-derived isotopic characteristics are fundamentally distinct from the acidic granitic and granodioritic plutons in the region.

Figure 10.

(a) Primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagrams; (b) Chondrite-normalized REE patterns (normalization values after Sun et al. [21], the upper continental crust normalization data after Taylor et al. [29]).

Gabbro samples (JLG-07) have low total REE (ΣREE, Table 4), (La/Yb)N = 3.237, and (La/Sm)N = 1.926. Neither light rare earth elements (LREEs) nor heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) are enriched (Table 4, Figure 10b). The total rare earth element (REE) contents of the granodiorite samples (JLG-12, JLG-14, JLG-18) vary over a wide range (134.381 ppm–233.056 ppm, Table 4). These samples are enriched in light rare earth elements (LREEs) and exhibit right-inclined REE distribution patterns with distinct Eu anomalies (Figure 10b). The total rare earth element (REE) contents of the granite samples (JLG-02, JLG-03, JLG-06) range from 136.705 ppm to 175.945 ppm (Table 4). These samples are enriched in light rare earth elements (LREEs) and display right-inclined REE distribution patterns with distinct Eu anomalies (Figure 10b).

5. Discussion

5.1. Zircon Geochemistry and Crystallization Ages of the Plutons

Magmatic zircons are key carriers of magmatic crystallization information, and their accurate identification is the basis for determining the crystallization age of the JPC. Combined with petrographic, geochemical, and isotopic evidence, the core discriminant criteria for magmatic zircons in this study are as follows: In terms of morphology and internal structure, magmatic zircons exhibit euhedral to subhedral prismatic shapes with sharp edges, lengths of 20–250 μm, and well-developed oscillatory zoning in CL images (Figure 3). This zoning is formed by the periodic enrichment and depletion of elements during magma crystallization, directly reflecting the continuous change in melt/fluid composition during zircon growth [30]. Their Th/U ratios are generally greater than 0.1 (most >0.4, Figure 4), which is a classic geochemical indicator of magmatic origin [31]. In contrast, hydrothermal zircons, which form from hydrothermal fluids or saturated residual melts at 300–600 °C [32], often have subhedral to anhedral, short prismatic, or equant shapes with blurred edges; their internal structures are porous, spongy, or dissolved, and CL images show blurred or no zoning (Figure 3f), closely related to fluid-rock interaction and physicochemical conditions of the hydrothermal system [33,34]. Metamorphic zircons are related to late magmatic hydrothermal activity [35], usually containing fluid inclusions, xenotime, and thorite, and their Th/U ratios are relatively low (<0.1), further distinguishing them from magmatic zircons [36].

The weighted mean age of magmatic zircons from the same sample is the direct basis for determining the crystallization age of the corresponding pluton. Zircon points plotting in the magmatic field on the La vs. (Sm/La)N diagram (Figure 5h) are identified as magmatic zircons [37]. For sample JLG-02 (Pluton II), only one zircon is magmatic, with an age of 217 ± 3 Ma (Figure 5h, Table 5); for JLG-03 (Pluton II), only one zircon is magmatic, with an age of 213 ± 4 Ma (Figure 5h, Table 5); for JLG-06 (Pluton III), two zircons were used for weighted mean age calculation, yielding a weighted mean age of 216 ± 2 Ma (Figure 11b, Table 5); for JLG-07 (Pluton I), twelve zircons were used for weighted mean age calculation, yielding a weighted mean age of 238 ± 1 Ma (Figure 11c, Table 5); for JLG-12 (Pluton VI), two zircons were used for weighted mean age calculation, yielding a weighted mean age of 224 ± 2 Ma (Figure 11d, Table 5); for JLG-14 (Pluton V), three zircons were used for weighted mean age calculation, yielding a weighted mean age of 252 ± 2 Ma (Figure 11e, Table 5); for JLG-18 (Pluton IV), five zircons were used for weighted mean age calculation, yielding a weighted mean age of 246 ± 3 Ma (Figure 11f, Table 5).

Table 5.

Data for magmatic zircons used for age interpretation.

Figure 11.

Weighted mean date plots for magmatic zircons from samples. The red line represents the age and its error distribution, the blue line represents the weighted mean age line, and the remaining black horizontal lines represent the scale markers.

In sample JLG-07, two analytical spots yielded highly discordant ages of 203.8 Ma and 334.8 Ma, which deviate significantly from the main magmatic age range of 236.1–239.6 Ma (Figure 6d, Table 5). Analytical spots 1 (203.8 ± 2.8 Ma) and 2 (334.8 ± 7.1 Ma) in the JLG-07 sample correspond to the rim and core of the same zircon grain, respectively. Analysis of the zircon’s cathodoluminescence (CL) images, transmitted light images, and reflected light images indicates that both spots may be located on or near fractures and inclusions, which could result in anomalously older or younger measured ages. Therefore, these age data are considered unreliable and should not be used to discuss the crystallization age of the rock, nor do they represent magmatic crystallization ages.

In summary, the granite swarm in the Jiangligou area formed during the Triassic period (252–216 Ma). Multi-stage magmatism resulted in different crystallization ages for granite Plutons II (JLG-02/JLG-03, 216 ± 2 Ma) and III (JLG-06, 216 ± 2 Ma). Their formation sequence is III = II. The gabbro of Pluton I formed at 238 ± 1 Ma. Pluton IV (granodiorite, JLG-18) formed at 246 ± 3 Ma. Pluton V (granodiorite, JLG-14) formed at 252 ± 2 Ma. The granodiorite of Pluton VI (JLG-12) formed at 224± 2 Ma. Therefore, the formation sequence of the six plutons from early to late is V > IV > I > VI > III = II.

5.2. Petrogenesis of the Plutons

Zircon Hf isotopes are effective tracers for magma source regions. The Hf isotopic composition of the JPC exhibits a systematic spatial distribution: the JLG-18 (Pluton IV) displays the most depleted source characteristics (εHf(t) as low as −8.32, with the oldest TDM2 of 1798 Ma), representing an end-member dominated by ancient crustal components. The JLG-12 (Pluton VI) (εHf(t) = −3.1, TDM2 = 1451 Ma) also indicates a significant contribution from ancient crust. The JLG-02 and JLG-06 Plutons exhibit transitional characteristics (εHf(t) ranging from −0.8–+1.67, TDM2 between 1280 and 1144 Ma), revealing a crust–mantle mixing process. In contrast, the JLG-07, JLG-03, and JLG-14 Plutons constitute relatively depleted end-members (all with positive εHf(t) values, up to +2.91, and the youngest TDM2 of 1079 Ma), reflecting a greater input of juvenile mantle-derived material.

Overall, the εHf(t) values of the entire JPC range from −8.3 to +2.9, which closely overlaps with the characteristic values of the Songpan–Ganzi Orogen (−7 to +3 [38]), indicating that both orogenic belts have hybrid crust–mantle source regions. The negative εHf(t) values (represented by the JLG-12 and JLG-18 Plutons, −8.3 to −2) correspond to TDM2 ages mainly concentrated between 1400 and 1800 Ma, with an average of 1538 Ma, consistent with the Paleoproterozoic basement age of the West Qinling [1], revealing the contribution of ancient crustal materials. The transitional εHf(t) values (represented by the JLG-02 and JLG-06 Plutons, −2 to 0) have an average TDM2 age of 1233 Ma, interpreted as a mixture of the aforementioned ancient crustal source and a younger mantle-derived component. The positive εHf(t) values (mainly represented by the JLG-03, -07, and -14 Plutons, 0 to +2.9), accounting for 54% of the total, have an average TDM2 age of 1160 Ma, corresponding to a Late Neoproterozoic mantle enrichment event [39], confirming significant input of juvenile mantle-derived materials into the magma source region.

The gabbro sample JLG-07 (Pluton I) exhibits major element compositions indicative of a mantle-derived origin, characterized by low SiO2 (51.8%), high MgO (9.84%), and high CaO (13.86%). These features, particularly MgO > 8% and CaO > 10%, are consistent with magmas derived from the partial melting of the lithospheric mantle [40]. This interpretation is further supported by the positive zircon εHf(t) values ranging from +1.1 to +2.9 and a young TDM2 model age averaging 1125 Ma, which collectively suggest the input of juvenile mantle-derived materials into the magma source [39]. However, certain geochemical anomalies indicate that the primary mantle-derived magma experienced crustal contamination during its ascent. Specifically, the Sr content of JLG-07 (550 ppm) is significantly higher than that of typical mantle-derived gabbro (usually <400 ppm), and its Al2O3 content (13.9%) is slightly elevated compared to typical mantle-derived magmas (generally <13%). These deviations suggest that the magma likely incorporated upper crustal materials—such as partial melts from Paleozoic sedimentary or metamorphic rocks—during its emplacement. Consequently, the gabbro is interpreted to represent a hybrid magma system dominated by mantle sources but modified by crustal contamination. For this sample, the low SiO2 and Na2O contents, along with the relatively high Sr content combined with its primitive mineral assemblage (dominantly plagioclase and clinopyroxene, Table 2) and mantle-like isotopic signature (positive εHf(t) values, Table S2), are interpreted to primarily reflect its mantle-derived origin with possible crustal assimilation during ascent, rather than pervasive hydrothermal alteration [29,31]. The low K2O/Na2O (0.39, Table 4) ratio and specific elemental signature may be inherent to the magma source or result from early-stage crystal fractionation [41]. The absence of widespread secondary minerals in thin sections further supports that the bulk-rock composition largely preserves magmatic signatures.

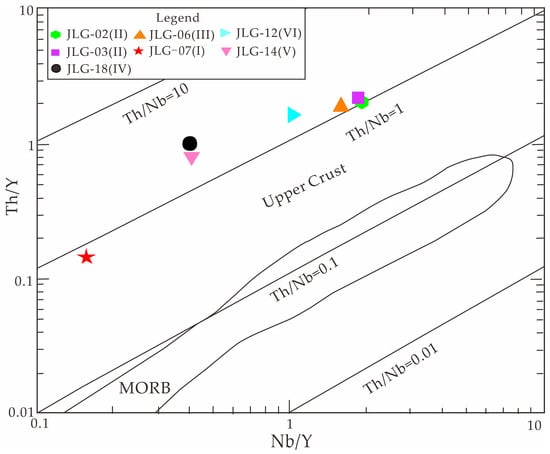

The Nb/Y vs. Th/Y diagram indicates the samples were mainly derived from the upper crust (Figure 12). Among these, Pluton I (JLG-07) plots in the upper crust field. This feature does not indicate that the magma was directly derived from the remelting of the upper crust but rather reflects the intense interaction between mantle-derived magma and upper crustal materials: during the late stage of Mianlue Ocean subduction (~237.7 Ma, the crystallization age of Pluton I), fluids released from the subducting slab metasomatized the lithospheric mantle, promoting the partial melting of the mantle to form primary mantle-derived magma. As this magma ascended along fractures, it underwent assimilation with the widely distributed upper crustal metamorphic rocks (e.g., Paleozoic Daguan Mountain Formation clastic rocks) in the northwestern margin of the West Qinling Mountains. The incorporation of crustal materials led to an increase in the contents of elements such as Th and Nb in the magma, ultimately causing the samples to shift toward the “upper crust field” in the Nb/Y–Th/Y diagram.

Figure 12.

Discriminant diagram for source materials of the Jiangligou Plutonic Complex (after Boztug et al. [40]).

In addition, the MMEs commonly developed in Pluton I—whose nature as products of crust–mantle mixing has been confirmed by previous studies [6,7]—further corroborate the genetic model of “mantle-derived magma + crustal contamination.” This process records key information about crust–mantle material circulation in the West Qinling region under the background of Mianlue Ocean subduction during the early Triassic period, providing direct evidence for crust–mantle interaction prior to plate collision.

The traditional positive/negative dichotomy in the εHf(t) values can only provide a preliminary distinction between crustal and mantle end-member contributions. In this study, 85% of the εHf(t) values are concentrated within the −2 to +2.9 range (encompassing both the transitional and positive intervals), indicating that the magma source was predominantly characterized by “crust–mantle mixing.” The contribution from a single end-member (either purely crustal or purely mantle) is extremely limited, with only 23% of the values (falling within the −8.3 to −2 range) representing an ancient crustal end-member (Table S2).

5.3. Tectonic Setting and Its Implications for the Tectonic Evolution of the West Qinling

5.3.1. Multi-Stage Magmatism and Tectonic Significance

In the Jiangligou area, Pluton IV (JLG-18), Pluton V (JLG-14), and Pluton VI (JLG-12) are all granodiorites, yet they exhibit significant differences in crystallization ages (252–224 Ma). This may reflect multiple phases of magmatic intrusion activities, complex deep-seated processes, and the evolution of tectonic environments in this area. This is closely related to the closure of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean and subsequent continental collision. Multi-stage intrusions mean the pluton group formed from multiple independent magma pulses emplaced over a long geological time, not a single event [42,43]. The similar geochemical composition but distinct crystallization ages of the granodioritic Plutons V (252 ± 2 Ma), IV (246 ± 3 Ma), and VI (224 ± 2 Ma) can be explained by an open-system magma chamber model. During the Indosinian (Triassic), the Western Qinling underwent a transition from late subduction of the Mianlue Ocean to collision between the North China and Yangtze blocks [1]. Metasomatism by subduction zone fluids/melts provided continuous mantle-derived inputs to the deep magma chamber, establishing the foundation for multi-stage magma evolution. Throughout the Indosinian, the magma chamber received repeated replenishment of lithospheric mantle-derived magmas. This recharge sustained high temperatures and, through magma mixing, counteracted the compositional evolution of the residual melt from fractional crystallization. This is consistent with regional patterns: zircon εHf(t) values of Indosinian granitoids (237–219 Ma) in the eastern Western Qinling show negative to positive fluctuations (−6.3 to +2.2), indicating contributions from both ancient crust and juvenile mantle sources [44]. Such multi-stage magmatism can produce compositionally similar yet temporally distinct intrusions.

5.3.2. Geochemical Evidence for Tectonic Setting

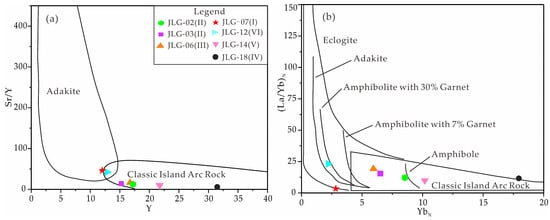

On the Y vs. Sr/Y diagram (Figure 13a), samples from Plutons II (JLG-02, JLG-03), III (JLG-06), IV (JLG-18), and V (JLG-14) plot in the classic island arc rock field. They have low LREE/HREE fractionation ((La/Yb)N = 3.24–22.92, average 13.1, Figure 13b and Table 4), high Sr (210 ppm–550 ppm, average 309 ppm) and Sr/Y ratios (7–45.8, average 19.5), and high Y (>12 ppm) and Yb (>6.64 ppm) contents. These features display the geochemical characteristics of classic island arc rocks to some extent [45]. This is similar to the tectonic setting inferred from their crystallization ages: subduction of the Mianlue Ocean and initial collisional orogeny.

Figure 13.

(a) Y vs. Sr/Y diagram; (b) YbN vs. (La/Yb)N diagram (base maps after Castillo [46]; fields for adakite and classic island arc rocks from Defant et al. [47] and Petford et al. [45]).

Adakite is a type of acidic to intermediate-acidic igneous rock with specific geochemical characteristics, typically closely related to partial melting in high-pressure environments [45]. Typical major element characteristics include SiO2 ≥ 56%, Al2O3 > 15% (aluminous), low MgO content, generally sodium-rich with Na2O/K2O ratios mostly greater than 2, and belonging to the calc-alkaline series [2,45]. Its trace elements are markedly characterized by high Sr (>400 ppm), low Y (<18 ppm), and low heavy rare earth elements (e.g., Yb < 1.9 ppm), indicating the presence of a garnet residual phase in the source region—garnet can retain Y and HREE under high-pressure conditions, thereby enriching the melt in Sr [45,46]. Furthermore, adakites feature high Sr/Y ratios (often >40–50), strong enrichment in LREE, (La/Yb)N > 10, significant depletion in high field strength elements such as Nb, Ta, Ti, and insignificant Eu anomalies [2,47]. These geochemical indicators collectively suggest that they may originate from the partial melting of subducted oceanic crust or thickened lower crust under high-pressure conditions [48,49].

Among the samples from the JPC involved in this study, JLG-07 (Pluton I) and JLG-12 (Pluton VI) show obvious adakitic affinities. JLG-07 has SiO2 of 51.8%, which is relatively low, but its Al2O3 reaches 14%, with extremely high Sr content, very low Y content, a high Sr/Y ratio of 45.83, and (La/Yb)N of 3.24 (some indicators fall within the adakite range) [50]. The adakitic geochemical signatures of JLG-07 and JLG-12 (e.g., high Sr/Y, low Y) are interpreted as primarily magmatic in origin [2,47], reflecting partial melting of a thickened lower crust or interaction between mantle-derived melts and crustal materials in a collisional setting [4,51]. While localized mineral alterations (e.g., hornblende to chlorite) are observed under the microscope, they are considered secondary and limited in scale, not significantly overprinting the primary magmatic geochemical signatures used for tectonic discrimination [52]. Therefore, the adakitic characteristics are robust indicators of a high-pressure melting environment during the Late Triassic continental collision [1,4,51]. JLG-12 (SiO2 = 68%, Al2O3 = 15.6%) exhibits high Sr (inferred value corresponding to the high Sr/Y = 42.03 in the table) and low Y characteristics. Its Sr/Y and (La/Yb)N (22.92) both fall within the adakite scale, while on discriminant diagrams it plots in the overlapping field of adakite and island arc rocks, reflecting its potential geochemical affinity with both rock types [4].

From a regional tectonic perspective, the North China and Yangtze blocks underwent continent–continent collision during the Late Triassic, causing large-scale crustal shortening and thickening [1]. The partial melting of this thickened lower crust (>50 km) under high-temperature conditions can generate igneous rocks with adakitic signatures, such as high Sr/Y and low Y [53]. The Y–Sr/Y geochemical compositions of samples JLG-07 (Pluton I, gabbro) and JLG-12 (Pluton VI, granodiorite) from the Jiangligou area show certain similarities with the adakite model formed by high-pressure melting of thickened crust (high Sr/Y, low Y), which supports the interpretation that this region was in an intracontinental orogenic stage during the Late Triassic, rather than a typical oceanic plate subduction environment [54]. However, it must be clarified that their genetic mechanisms are fundamentally distinct: Pluton VI (JLG-12, 224 ± 2 Ma) has a crystallization age within the peak collision period (224–210 Ma) and exhibits characteristics such as high Sr (inferred), low Y, high Sr/Y ratio (42.03), and (La/Yb)N (22.92), consistent with the adakite model involving partial melting of thickened lower crust under high pressure. The retention of garnet in the source leads to depletion of Y and heavy rare-earth elements in the melt. Its negative εHf values (−3.13~−3.09) further indicate that the magma originated from partial melting of ancient crustal material, representing a geochemical response to crustal thickening during collisional orogeny. The origin of Pluton I (JLG-07, gabbro) cannot be explained by the partial melting model of thickened crust, as gabbroic compositions are not typical products of crustal melting. Based on its geochemical features and regional geological setting, a more plausible explanation is contamination of mantle-derived magma by adakitic melt. Mafic magma generated by partial melting of the lithospheric mantle ascended and mixed with adakitic melts produced by partial melting of the lower crust. This process preserved the mantle-derived material basis required for gabbro (high MgO, CaO, and positive εHf values of +1.1~+2.9) while acquiring adakite-like geochemical signatures, such as high Sr, low Y, and high Sr/Y ratio (45.83) through contamination. In summary, these two types of rocks with “adakitic affinity” represent different responses to crustal thickening and crust–mantle interaction during collisional orogeny: Pluton VI records the partial melting of thickened lower crust, while Pluton I reflects contamination of mantle-derived magma by crustal melts. Together, they provide key evidence for the Late Triassic tectonic evolution of the northern margin of the West Qinling [55,56].

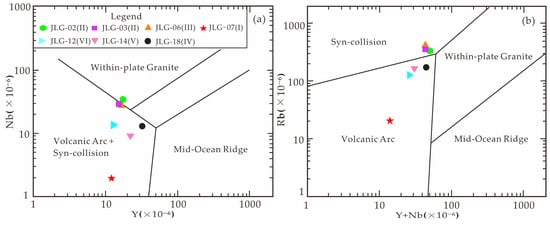

On the Y–Nb diagram (Figure 14a), Pluton II (JLG-02) plots in the “within-plate” field. This may indicate a local post-collisional extensional environment or magmatism under crustal extension. It could also result from the incorporation of enriched mantle components during crustal melting. Other samples plot in the “volcanic arc + syn-collision” field (Figure 14a). This reflects magmatism possibly controlled by both subduction (volcanic arc) and post-collisional compression (syn-collision) [57].

Figure 14.

(a) Y vs. Nb diagram; (b) (Y + Nb) vs. Rb diagram for the Jiangligou Plutonic Complex (after Pearce et al. [57]).

On the Y + Nb vs. Rb diagram (Figure 14b), Plutons I (JLG-07), IV (JLG-18), V (JLG-14), and VI (JLG-12) plot in the volcanic arc field. This is related to the melting of a mantle wedge metasomatized by subduction zone fluids, representing a typical active continental margin or island arc environment. Plutons II (JLG-02, JLG-03) and III (JLG-06) plot in the syn-collision field (Figure 14b). This reflects magmas formed by crustal melting after plate collision, typically related to compressional backgrounds of continent–continent or arc–continent collision [57]. Under a compressional setting, the Plutonic Complex exhibits geochemical characteristics including high K2O/Na2O ratios (0.39–1.51, Table 4) and a calc-alkaline affinity (plotting in the calc-alkaline/high-K calc-alkaline field on the SiO2–K2O diagram) (Figure 8) [25,58]. In terms of trace elements, it is enriched in large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs: Rb, Th) and depleted in high-field-strength elements (HFSEs: Nb, Ti, Figure 10), which is also consistent with the genetic attribute of I-type granites—i.e., “crust–mantle mixing or partial melting of the lower crust” [59,60].

5.3.3. Regional Tectonic Evolution Model

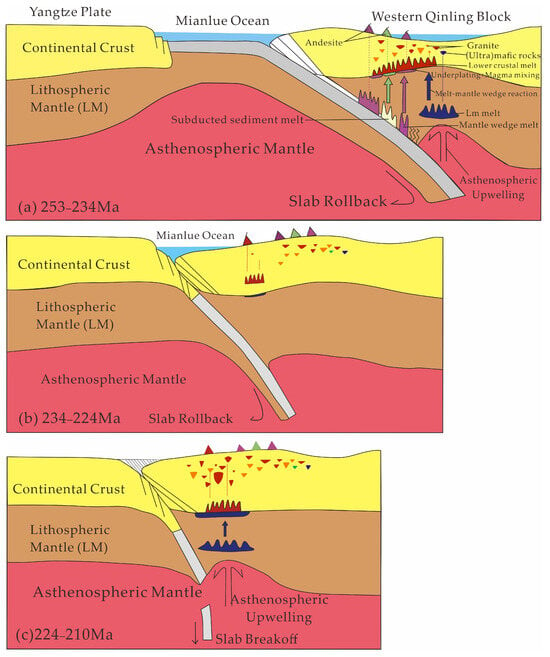

During the period of 253–210 Ma, the Yangtze Plate subducted northwestward, and the West Qinling block, acting as a transitional zone, underwent a multi-stage tectonic–magmatic evolution (Figure 15) [61]. This evolutionary process is closely linked to the formation setting of the JPC in West Qinling [1].

Figure 15.

Schematic diagram illustrating the tectonic evolution model of the West Qinling orogenic belt during the Indosinian period. (a) Late Mianlue Ocean subduction, 253–234 Ma: The Yangtze Plate subducts northwestward, and the Mianlue Oceanic crust undergoes slab rollback → Asthenospheric upwelling induces mantle melting. (b) Initial collision, 234–224 Ma: The Mianlue Ocean gradually closes, initial collision occurs between the North China and Yangtze plates, with ongoing slab rollback. (c) Peak collision stage, 224–210 Ma: Intense continental collision leads to slab breakoff → Asthenospheric upwelling induces melting of the thickened crust.

From 253 to 234 Ma, corresponding to the early Indosinian (late-stage subduction of the Mianlue Ocean), the Yangtze Plate subducted northwestward, accompanied by slab rollback. The rollback induced asthenospheric upwelling. The upwelling asthenospheric material melted the lithospheric mantle of the West Qinling block. The resulting mantle-derived magmas assimilated with upper crustal materials of the West Qinling during their ascent, ultimately forming the early-stage magmatic rocks in the West Qinling region (Figure 15a). Plutons V, IV, and I of the Jiangligou cluster record the magmatic activity characteristics of this stage, which were dominated by mantle-derived signatures with crustal contamination [62]. The negative εHf(t) values of Pluton IV could be due to crustal contamination of the mantle-derived magma by ancient crustal materials or because the mantle component acted mainly as a heat source, triggering melting of the ancient crust without significantly contributing to its Hf isotope signature.

The period from 234 to 224 Ma represents the middle Indosinian (initial plate contact and collision). Slab rollback continued, and the influence of the Yangtze Plate subduction on the West Qinling block intensified further. Magmatic activity during this stage was still influenced by slab rollback, but compared to stage a, the depth of magma generation and the interaction with the crust changed, laying the foundation for the evolution of subsequent magmatism (Figure 15b). Pluton VI of the Jiangligou cluster records the characteristics of the magmatic activity in this stage [63].

From 224 to 210 Ma, during the late Indosinian (peak collision period), slab breakoff occurred, leading to another episode of asthenospheric upwelling. Following the breakoff, upwelling of deep hot material caused partial melting of the mid-lower crust of the West Qinling block under high-temperature conditions, generating magmas predominantly derived from crustal remelting (Figure 15c). This is represented by Pluton II and Pluton III of the Jiangligou cluster [55]. Plutons II and III have A/CNK values greater than 1.0, indicating peraluminous characteristics (Figure 8). They exhibit significant enrichment in light rare earth elements (LREE) and depletion in heavy rare earth elements (HREE), evidenced by high (La/Yb)N ratios, and their REE patterns are typically right-sloping (Figure 10). Their geochemical features clearly indicate a crustal remelting origin [26]. This sequence illustrates the tectonic–magmatic evolution of the West Qinling block under the subduction context of the Yangtze Plate, transitioning from early mantle melting with crustal contamination to late-stage crustal remelting. The εHf(t) values of Plutons II and III range from positive to slightly negative within analytical uncertainty (Table S2). This variation may result from the incorporation of minor amounts of juvenile mantle-derived material during crustal melting. The input of such young mantle components could have elevated the εHf(t) values, while the predominantly crustal signature of the melt was preserved.

6. Conclusions

(1) The JPC was formed during the Triassic period (252–216 Ma) and exhibits multi-stage intrusion characteristics. Among them, Pluton IV (granodiorite, 246 ± 3 Ma), Pluton I (gabbro, 238 ± 1 Ma), and Pluton V (granodiorite, 252 ± 2 Ma) formed in the Early Triassic and correspond to the tectonic setting of the late subduction stage of the Mianlue Ocean. Pluton II (216 ± 2 Ma), Pluton III (216 ± 2 Ma), and Pluton VI (224 ± 2 Ma), formed in the Middle-Late Triassic, respond to the peak collision period of the North China–Yangtze blocks. This revises the previous conclusion of “formation in the late Middle Permian” and improves the spatiotemporal framework of Triassic magmatic activities in the northwestern margin of the West Qinling.

(2) The JPC represents a multi-stage magmatic response to tectonic activities in the West Qinling from the late subduction stage of the Mianlue Ocean to the peak collision period of the North China–Yangtze blocks during the Indosinian period, with a collisional tectonic setting as the main one. Early Triassic plutons were formed in an island arc environment with slight collision influence, recording magmatic activities from the late subduction of the Mianlue Ocean to the initial collision of the blocks. Middle-Late Triassic plutons were formed in a collisional environment, corresponding to the peak collision period of the blocks, fully revealing the tectonic–magmatic evolution process of the West Qinling region from early “crust–mantle mixing” to late “intracontinental collision.”

(3) The zircon geochemical data from this study demonstrate that using a Th/U ratio > 0.4 (instead of the conventional threshold > 0.1) as a core geochemical criterion for selecting magmatic zircons, combined with typical oscillatory zoning structures, can more effectively identify zircons that represent primary magmatic crystallization events, thereby yielding more reliable ages for pluton formation. This provides a stricter data-filtering basis for the precise delineation of multi-stage magmatic activities within orogenic belts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min16010021/s1, Table S1: Zircon LA-ICP-MS U–Pb isotope data; Table S2: Lu–Hf isotope data; Table S3: Trace and Rare Earth Elements data. Table S4: Chondrite-normalized Rare Earth Element (REE) Data of Zircons.

Author Contributions

Data curation, L.M., W.Z., W.M. (Weiming Ma), C.W., X.Q. and Z.Z.; software, L.M., Z.J., J.S., X.Q., Y.M., W.M. (Wenzhi Ma) and J.M.; Writing—original draft, L.M., Z.J. and C.L.; Writing—review and editing, Z.J., C.L. and J.M.; Supervision, Z.J., C.L. and J.M.; funding acquisition, C.L., Z.J., J.M. and W.M. (Wenzhi Ma). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the “Research on Tracking and Planning Deployment of Mineral Exploration in Qinghai Province” of the China Geological Survey (Project No. DD20230349), the “Research on Strategic Mineral Exploration Deployment in Qinghai Province” of the Qinghai Provincial Geological Exploration Special Fund Project (Project No. 2023085028ky003), the Xining City Land Surveying and Planning Research Institute Co., Ltd. Research project (GHYXM2023-018), and the Applied Basic Research Project of the Qinghai (China) Provincial Science and Technology Department (2023-ZJ-781).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding authors of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the journal editor and reviewers for their contributions to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Changhai Luo, Weiming Ma, Chengyong Wang, Juan Shen, and Yanjing Ma were employed by the Qinghai Provincial Geological Survey Bureau, Technology Innovation Center for Exploration and Exploitation of Strategic Mineral Resources in Plateau Desert Region, Ministry of Natural Resources. Authors Jinhai Ma and Wenzhi Ma were employed by the Qinghai General Team of China Building Materials Industry Geological Exploration Center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dong, Y.P.; Zhang, G.W.; Neubauer, F.; Liu, X.M.; Genser, J.; Hauzenberger, C. Tectonic evolution of the Qinling orogen, China: Review and synthesis. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H. Adakitic magmas: Modern analogues of Archaean granitoids. Lithos 1999, 46, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Li, T.; Chen, J.L.; Li, P. The Granitic Magmatism and Mineralization in West Section of the Western Qinling, NW China. Northwestern Geol. 2012, 45, 76–82, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, P.R. Adakite petrogenesis. Lithos 2012, 134, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.P.; Xu, X.Y.; Chen, J.L.; Gao, T.; Li, T.; Li, X.B.; Li, X.Y. Geochemical Characteristics and Chronology of the Jiangligou Granitic Pluton in West Qinling and Their Geological Significance. Acta Geol. Sin. 2013, 87, 330–342, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.Y.; Chen, J.L.; Gao, T.; Li, P.; Li, T. Granitic Magmatism and Tectonic Evolution in the Northern edge of the Western Qinling terrane, NW China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 371–389, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.Y.; Ye, H.S.; Cao, J.; Qi, L.Z.; Wang, P.; Chao, W.W. LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb ages, Hf isotopic compositions, geochemistry characteristics and its geological significance of Jiangligou composite granite, West Qingling Orogen. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 942–962, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ni, C.Y.; Jiang, Y.H. Petrogenesis and Tectonic Implications of the Indosinian Fengxian Pluton, Western Qinling Orogeny. Geol. J. China Univ. 2023, 29, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.C.; Hu, G.H.; Hu, F.F.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Genetic links of crustal radiogenic heating to peraluminous granites. Lithos 2025, 504–505, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, M.A.; Fan, W.M.; Zhang, M. Palaeozoic and Cenozoic lithoprobes and the loss of >120 km of Archaean lithosphere, Sino-Korean craton, China. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1993, 76, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.Y.; Ye, H.S.; Yu, M.; Cao, J.; Tan, J.; Tian, J. Geological features and molybdenite Re-Os isotopic dating of the Jiangligou W-Cu-Mo polymetallic deposit, West Qinling. Acta Geol. Sin. 2015, 89, 731–746. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, R.J.; Groves, D.I. Orogenic gold: Common or evolving fluid and metal sources through time. Lithos 2015, 233, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, D.I.; Santosh, M.; Deng, J.; Wang, Q.F.; Yang, L.Q.; Zhang, L. A holistic model for the origin of orogenic gold deposits and its implications for exploration. Miner. Depos. 2020, 55, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Liu, X.M. Proficiency Testing of the XRF Method for Measuring 10 Major Elements in Different Rock Types. Rock Miner. Anal. 2016, 35, 145–151, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.M.; Hu, Z.C.; Diwu, C.R.; Yuan, H.L.; Gao, S. Evaluation of Accuracy and Long-Term Stability of Determination of 37 Elements in Geological Samples by ICP-MS. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 1203–1210, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.L.; Gao, S.; Liu, X.M.; Li, H.M.; Günther, D.; Wu, F.Y. Accurate U-Pb Age and Trace Element Determinations of Zircon by Laser Ablation-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 2004, 28, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. Correction of common lead in U-Pb analyses that do not report 204Pb. Chem. Geol. 2002, 192, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeesch, P. IsoplotR: A free and open toolbox for geochronology. Geosci. Front. 2018, 9, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.L.; Gao, S.; Dai, M.N.; Zong, C.L.; Günther, D.; Fontaine, H.G.; Liu, X.M.; Diwu, C.R. Simultaneous determinations of U-Pb age, Hf isotopes and trace element compositions of zircon by excimer laser-ablation quadrupole and multiple-collector ICP-MS. Chem. Geol. 2008, 247, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Li, X.H.; Zheng, Y.F.; Gao, S. Lu-Hf Isotopic System and Its Petrological Applications. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 185–220, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. In Magmatism in the Ocean Basins; Saunders, A.D., Norry, M.J., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Special Publications: London, UK, 1989; Volume 42, pp. 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskin, P.W.O. Trace-element composition of hydrothermal zircon and the alteration of Hadean zircon from the Jack Hills, Australia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvel, C.; Blichert-Toft, J. A hafnium isotope and trace element perspective on melting of the depleted mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 190, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, I.D.; Tilley, C.E. Iron enrichment and pyroxene fractionation in tholeiites. Geol. J. 1964, 4, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, P.C. Boundary lines within petrologic diagrams which use oxides of major and minor elements. Lithos 1989, 22, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniar, P.D.; Piccoli, P.M. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1989, 101, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.D.; Chung, S.L.; Cawood, P.A.; Niu, Y.; Liu, S.A.; Wu, F.Y.; Mo, X.X. Magmatic record of India-Asia collision. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vavra, G.; Schmid, R.; Gebauer, D. Internal morphology, habit and U-Th-Pb microanalysis of amphibolite-to-granulite facies zircons: Geochronology of the Ivrea Zone (Southern Alps). Contrib. Min. Petrol. 1999, 134, 380–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, W.L.; Pearson, N.J.; Belousova, E.; Jackson, S.E.; van Achterbergh, E.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Shee, S.R. The Hf isotope composition of cratonic mantle: LAM-MC-ICPMS analysis of zircon megacrysts in kimberlites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2000, 64, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, T.; Rashwan, A.A.; Rahn, M.K.W.; Poller, U.; Zwingmann, H.; Pidgeon, R.T.; Schleicher, H.; Tomaschek, F. Low-temperature hydrothermal alteration of natural metamict zircons from the Eastern Desert, Egypt. Mineral. Mag. 2003, 67, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, M.L.; Tassinari, C.C.G.; Matos, F.M.V.; Sato, K.; Huhn, S.; Ferreira, S.N.; Medeiros, C.A. Tracking hydrothermal events using zircon REE geochemistry from the Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil. J. Geochem. Explor. 2021, 221, 106679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskin, P.W.O.; Ireland, T.R. Rare earth element chemistry of zircon and its use as a provenance indicator. Geology 2000, 28, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskin, P.W.O.; Schaltegger, U. The composition of zircon and igneous and metamorphic petrogenesis. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 53, 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudie, D.J.; Fisher, C.M.; Hanchar, J.M.; Crowley, J.L.; Ayers, J.C. Simultaneous in situ determination of UlPb and Sm–Nd isotopes in monazite by laser ablation ICP–MS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2014, 15, 2575–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bai, J.; Wang, Y.; Han, H.; Song, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, W. Petrogenesis and Tectonic Implication of Late-Triassic Granitoids in the West-Central Part of Songpan-Ganze Block. Northwestern Geol. 2023, 56, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, G.; Dong, X.J.; Li, S.C.; Zhao, Q.Y. Geochronology and geochemistry of Late Triassic intrusions in the Liaodong Peninsula, eastern North China Craton: Implications for post-collisional lithospheric thinning. Int. Geol. Rev. 2022, 64, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Jin, G.D.; Liao, S.Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, P. Geochemical and Sr-Nd-Hf isotopic constraints on the origin of Late Triassic granitoids from the Qinling orogen, central China: Implications for a continental arc to continent-continent collision. Lithos 2010, 117, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boztuğ, D.; Harlavan, Y.; Arehart, G.B.; Satir, M.; Avci, N. K-Ar age, whole-rock and isotope geochemistry of A-type granitoids in the Divriği-Sivas region, eastern-central Anatolia, Turkey. Lithos 2007, 97, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, T.L.; Kinzler, R.J.; Bryan, W.B. Fractionation of mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB). Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 1992, 71, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. Isoplot/Ex v. 3, a geochronological tool kit for Microsoft Excel: Berkeley. Calif. Geochronol. Cent. Spec. Publ. 2003, 4, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Lino, L.M.; Vlach, S.R.F. Textural and geochemical evidence for multiple, sheet-like magma pulses in the Limeira intrusion, Paraná Magmatic Province, Brazil. J. Petrol. 2021, 62, egab011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Li, Y.S.; Dong, G.C.; Lv, X.; Xia, Q. Indosinian granitic magmatism and tectonic evolution in the eastern segment of the West Qinling: Constraints from geochemistry, zircon U-Pb geochronology and Hf isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2021, 37, 1691–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Petford, N.; Atherton, M. Na-rich partial melts from newly underplated basaltic crust: The Cordillera Blanca Batholith, Peru. J. Petrol. 1996, 37, 1491–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, P.R. Origin of the adakite-high-Nb basalt association and its implications for postsubduction magmatism in Baja California, Mexico. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2008, 120, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, M.J.; Drummond, M.S. Derivation of some modern arc magmas by melting of young subducted lithosphere. Nature 1990, 347, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, R.W. Aleutian magnesian andesites: Melts from subducted Pacific Ocean crust. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1978, 4, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.S.; Defant, M.J. A model for trondhjemite–tonalite–dacite genesis and crustal growth via slab melting: Archean to modern comparisons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1990, 95, 21503–21521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, M.P.; Petford, N. Generation of sodium-rich magmas from newly underplated basaltic crust. Nature 1993, 362, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.L.; Liu, D.; Ji, J.; Chu, M.F.; Lee, H.Y.; Wen, D.J.; Lo, C.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, Q. Adakites from continental collision zones: Melting of thickened lower crust beneath southern Tibet. Geology 2003, 31, 1021–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, A.; Hofmann, A.W. Alteration and geochemical patterns in the 3.7–3.8 Ga Isua greenstone belt, West Greenland. Precambrian Res. 2003, 126, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, S.; Schmidt, M.W. Petrology of subducted slabs. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2002, 30, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.R.; Zhang, G.W. Geologic framework and tectonic evolution of the Qinling orogen, central China. Tectonophysics 2000, 323, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Rudnick, R.L.; Yuan, H.L.; Liu, X.M.; Liu, Y.S.; Xu, W.L.; Ling, W.L.; Ayers, J.; Wang, X.C.; Wang, Q.H. Recycling lower continental crust in the North China craton. Nature 2004, 432, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.L.; Wang, Q.H.; Wang, D.Y.; Guo, J.H.; Pei, F.P. Mesozoic adakitic rocks from the Xuzhou-Suzhou area, eastern China: Evidence for partial melting of delaminated lower continental crust. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2006, 27, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Harris, N.B.W.; Tindle, A.G. Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks. J. Petrol. 1984, 25, 956–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.J.R.; Chappell, B.W. Petrographic discrimination of low–and high–temperature I–type granites. Resour. Geol. 2004, 54, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, J.F.; Jian, P.; Bao, Z.W.; Zhao, Z.H.; Li, C.F.; Xiong, X.L.; Ma, J.L. Petrogenesis of adakitic porphyries in an extensional tectonic setting, Dexing, South China: Implications for the genesis of porphyry copper mineralization. J. Petrol. 2006, 47, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevin, P.L.; Chappell, B.W. Chemistry, origin, and evolution of mineralized granites in the Lachlan fold belt, Australia; the metallogeny of I-and S-type granites. Econ. Geol. 1995, 90, 1604–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J. Indosinian tectonic setting, magmatism and metallogenesis in Qinling Orogen, China. Geol. China 2010, 37, 854–865. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.D.; Jiang, Z.W.; Liu, X.S.; Luo, J.L.; Fan, L.Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Du, Y.F. Formation age and genesis of Early Mesozoic intrusive dikes in the southwestern Ordos Basin. Geol. Bull. China 2023, 42, 1098–1117, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratschbacher, L.; Hacker, B.R.; Calvert, A.; Webb, L.E.; Grimmer, J.C.; McWilliams, M.O.; Ireland, T.; Dong, S.W.; Hu, J.M. Tectonics of the Qinling (Central China): Tectonostratigraphy, geochronology, and deformation history. Tectonophysics 2003, 366, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.