Abstract

The progressive depletion of high-grade ore bodies has shifted attention toward the exploitation of lower-grade deposits as viable sources of value. In recent years, there has been growing emphasis on mining and processing methods that incorporate sustainability by addressing both environmental and socio-economic considerations. To maximize resource recovery, integrated strategies that combine exploration, grade control drilling, mine planning, and processing are essential. Within this framework, particle sorting has emerged as an effective coarse separation method that can upgrade low-grade feed prior to the more energy-demanding milling and subsequent processing stages. Incorporating screening before particle sorting not only assists in identifying the distribution of metals but also determines the most suitable particle size ranges for sorting performance. This study reports on the applicability of sensor-based sorting technologies to low-grade gold and nickel ores from Australia, with a focus on grade deportment by particle size. The results demonstrate that substantial upgrading of low-grade ores is possible, achieving 70%–80% metal recovery within approximately 30%–40% of the original mass through the use of induction and XRT sensors. Overall, the findings indicate that both induction and XRT sorting methods are broadly effective across ore types, offering enhanced upgrading capability and improved processing efficiency.

1. Introduction

Centuries of intensive mining have significantly reduced the availability of high-grade mineral deposits, shifting the focus toward exploiting lower-grade resources as viable alternatives for value generation [1,2]. In response, increasing emphasis is being placed on sustainable mining and processing methods that balance resource efficiency with socio-economic and environmental considerations. To maximize resource utilization, integrated strategies encompassing exploration, grade control drilling, mine planning, and processing are applied to reduce environmental impact, improve water and energy efficiency, and minimize tailings generation [3,4]. A major contributor to the sector’s energy footprint is comminution, which accounts for around 36% of onsite energy use and represents 4%–9% of Australia’s overall energy demand [5]. Reducing grinding requirements for low-grade ores offers opportunities for optimization [6]. In addition, comminution consumes over 413 gigalitres of water annually, roughly 2.2% of national water usage [7].

Coarse particle gangue rejection (CPGR) has emerged as a valuable pre-concentration strategy, selectively removing low-density waste material at an early stage while limiting recovery losses [8]. For commodities such as gold, copper, and nickel, CPGR is particularly advantageous when processing marginal or sub-economic ores, where reduced recovery can be offset by higher feed grades and improved metal output. Realizing this potential requires identifying key ore attributes such as mineralogy, breakage characteristics, particle morphology, and liberation behavior that govern suitability for coarse gangue rejection flowsheets. When implemented effectively, CPGR delivers tangible benefits, including lower energy demand and enhanced overall recovery efficiency [9,10]. Moreover, mass pull refers to the proportion of the total feed mass that reports to the product stream during sorting, and it reflects the selectivity and efficiency of the separation process. A lower mass pull indicates that a smaller mass fraction is retained while still achieving high metal recovery, which is a key objective in the coarse gangue rejection (CGR) process.

Within this context, particle sorting has become a recognized separation method that eliminates low-grade material before energy-intensive grinding stages [11]. These systems employ sensor-based technologies on properties such as particle density, conductivity, and color to determine whether to retain or reject particles [12,13]. However, the benefits of conducting prior grade-by-size analysis are often overlooked. Screening before sorting can provide insights into the natural distribution of valuable minerals across size fractions, ensuring better sample representation and reducing the risk of misinterpreting results when high-grade fines are overlooked by sorting equipment. This step may also enable early upgrading by identifying whether value is concentrated in either coarse or fine fractions, which can then be separated by screening. Screening as a preparatory stage has long been applied; Burns and Grimes (1986), for example, documented its use in copper ore pre-concentration at Bougainville [14]. More recently, comprehensive grade-by-size testing methods supported by global Response Ranking (RR) frameworks have been developed to refine such approaches [15,16]. The present study investigates the potential advantages of integrating screening with particle sorting as a combined pre-concentration strategy for upgrading low-grade Australian gold and nickel ores. It also examines how geological features and mineralogical characteristics influence ore response to coarse gangue rejection techniques, namely screening and sensor-based sorting.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sampling Procedure

Five ore domains classified as A, B, C, D and E were selected from three mining sites in Western Australia. Site 1: gold ore (Open-Pit Gold Mine, Western Australia near Kalgoorlie), site 2: nickel ore (Underground Mine, Western Australia near Leonora), and site 3: gold ore (Gold Mine in the Goldfields region of Western Australia). Approximately 50 ton of run-of-mine (ROM) ore that passed through a mobile crusher with a top size of ~180 mm and made to a single cone-like pile was collected from each domain (Figure 1a). In order to gain as representative a sub-sample as possible, a cone and quartering sampling method was applied where quarters were created from the initial stockpile, and two quarters were taken to make up a new pile. This procedure was repeated until a sub-sample of 2–3 tons was left (Figure 1b). In the next step, the 2–3 ton sub-samples from each ore domain were then screened to produce +110 mm, −110 + 70 mm, −70 + 45 mm, and −45 mm size fractions using a custom-made screening rig (Figure 1c). The −45 mm material was then screened by using 26.5 mm and 9.5 mm sieve apertures, creating −45 + 26.5 mm, −26 + 9.5 mm, and −9.5 mm size fractions.

Figure 1.

(a) 50-ton stockpile, (b) cone and quartering sampling, and (c) screening of sub-sampled material.

2.2. Grade-by-Size Assay

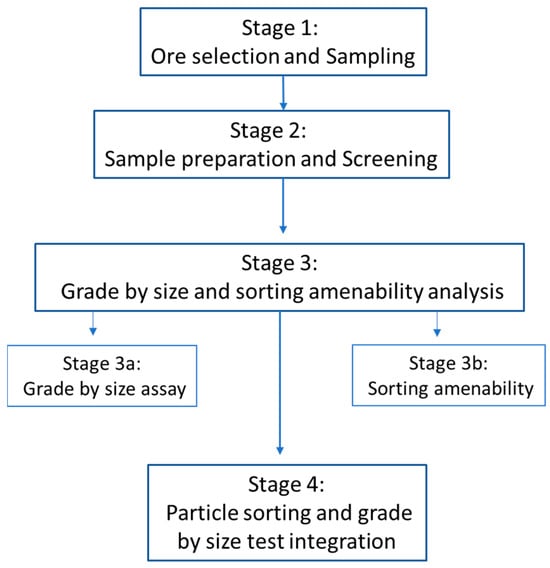

All size fractions were sent for grade by size analysis to determine the mean grade of each size fraction for each ore domain. The effective range for particle sorting lies between ~10 mm and ~100 mm in the current sorting technology. Thus, the middle 4 fractions (−110 + 70, −70 + 45, −45 + 26.5 and −26.5 + 9.5 mm) were sampled for particle sorting test work. The grade of each size fraction was determined through a mass of rock taken from each size fraction, while individual assays were conducted on rocks subsequent to particle sensing. The overall tasks and procedures completed to achieve the objectives is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Scheme for tasks completed for the screening and ore sorting stages.

2.3. Quantitative X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD) Analysis

The primary mineral phases present in the ores were characterized through XRD analysis. Samples from various size fractions and ore domains were micro-milled for 10 min using ethanol as the milling medium. The ground material was then gently compacted into a back-packed holder for examination. Mineral phases were identified using X’Pert High-Score Plus software (Version 5.3) in combination with manual reference files where required. Quantitative Rietveld analysis of the diffraction data was carried out with High-Score Plus version 4.7, employing the ICSD crystal structure database.

2.4. Measured Particle Sorting Yield Method

The measured particle sorting yield curve was generated by individually assaying a population of particles (i.e., 100 particles from each domain) to obtain metal grade. The assay results were used to determine whether a given particle was a waste rock or valuable. Theoretical yield curves were then calculated based upon the intrinsic sortability of the ore particles assuming perfect (ideal) separation. The results are, therefore, a function of the ore and can be replicated as completely independent measurements that can be used to compare with actual sorting yield curves to assess the efficiency of sensing and sorting technology.

2.5. Individual Particle (Actual) Sorting Procedure

For the sorting part of the project, 100 individual rocks from each ore domain and 4 size fractions (−26.5 + 9.5, −45 + 26, −70 + 45, and −110 + 70 mm) were tested. A number of sensors were considered to exploit variations in the physical properties and mineralogy of particles [17,18]. The following sensor technologies were utilized in this work:

- X-ray Transmission (XRT): evaluates variations in atomic density.

- 3D Laser: assesses particle dimensions and morphology, along with laser diffraction and brightness characteristics.

- Induction: detects and quantifies the electrical conductivity of metallic components.

- Color Camera: identifies and records differences in particle color.

The procedure adopted for sorting is as follows:

- Ore samples from 5 different domains for each site were sized and 100 particles per size fraction for each domain were cleaned, photographed, weighed, and labeled.

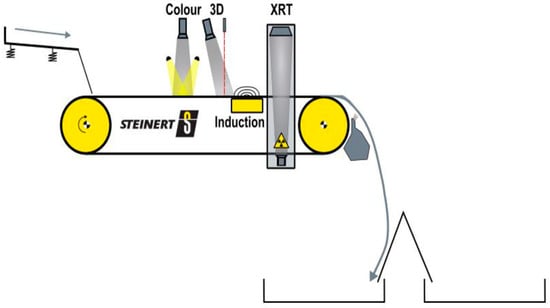

- Each rock was scanned once through our High Resolution KSS FLI XT sensor sorting machine (see schematic in Figure 3) to record the data from the sensors.

Figure 3. A schematic showing scanning only through KSS FLI XT (STEINERT).

Figure 3. A schematic showing scanning only through KSS FLI XT (STEINERT). - After scanning, all 100 rocks from −26 + 9.5 mm, −45 + 26 mm, −70 + 45 mm, and −110 + 70 mm rocks were sent for assays to confirm the grades of Au and Ni.

- Assay results were received and analyzed to complete the full evaluation using scans and their corresponding grades.

3. Results and Discussion

This paper provides a summary of results obtained through screening, individual particle sensing, and bulk sorting findings from one nickel mining site and two free-milling gold mining sites, investigating 15 low-grade ore domains in total.

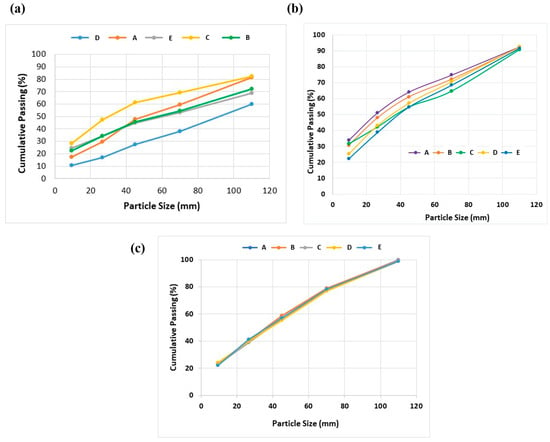

3.1. Particle Size Distribution (PSD) Analysis

The particle size distribution of each ore domain obtained after screening from site 1 is shown in Figure 4a. Results indicate that the ore domain (C) exhibits the highest proportion of fines, while the domain (D) displays a comparatively coarser size distribution. (A), (B), and (E) show relatively similar size distributions. Similarly, PSD of each ore domain obtained after screening from sites 2 and 3 is illustrated in Figure 4b,c, respectively. Figure 4b depicts a fairly consistent output size from the crusher for all samples, with the particle sizes varying from 79 to 90 mm and similar mass distributions between each size fraction across the samples. Likewise, Figure 4c also suggests that all ore domains show relatively similar size distributions. The similarities in PSD observed could be attributed to the similarities in the intrinsic hardness of the ores, while any differences in PSD observed could be due to any variations in the mining methods employed at different sites [19].

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution (PDS) of sub-sampled material for all ore domains; (a) site 1, (b) site 2, and (c) site 3.

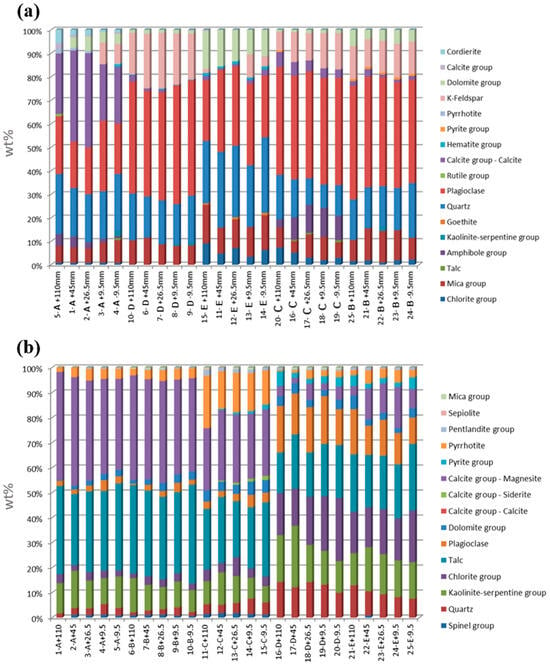

3.2. Main Mineral Phases

Figure 5a presents the quantitative XRD analysis of crystalline phases from Site 1. In all ore domains, plagioclase ((Na, Ca)Al(Al, Si)Si2O8) was identified as the main mineral phase, accounting for 45%–50% in some cases. The other main phases identified were quartz, K-Feldspar, and the mica group. It can be seen from Figure 5a that the variation in mineral abundance with particle size is neither systematic nor significant for all ore domains. Similarly, quantitative XRD analysis (crystalline phases) of site 2 is also shown in Figure 5b. In ore domains A-C, calcite group (magnesite) and talc (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2) were identified as the two main phases accounting for >70% in A and B, and about 50% in C. The other main phases identified were quartz, K-Feldspar, and the mica group. Kaolinite-serpentine group and pyrrhotite are the other main phases in A-C. Quartz, kaolinite-serpentine group, chlorite group, talc, and plagioclase appear to be evenly distributed in D and E. For a given ore domain, the variation in mineral abundance with particle size is not substantial. These results suggest that there may be limited sorting potential with particle size. However, there is significant mineralogical variation and some mineralogical differences from one ore domain to the other for reported sites 1 and 2, respectively, and thus, each ore domain may respond differently to ore sorting.

Figure 5.

Quantitative XRD results for 5 size fractions and 5 ore domains, (a) site 1 and (b) site 2.

3.3. Grade-by-Size Analysis

The amount of sampling and assay work conducted as part of this research project has provided a range of data sets for useful comparison and analysis. The average grade of the particles used in individual testing can be compared to the bulk sample assaying for direct grade by size, in addition to the bulk sample splits and triplicate assay. In addition to indicating the grade by size potential of the sampled ore domains, these sets provide insight into how representative samples may be and the degree of sampling and assay required for different ore types. Bulk samples (~30–50 kg) were taken from each size fraction for splitting and grade by size analysis. The exceptions to this were the −110 +70 mm fractions, as the individual rock analysis was deemed to represent enough mass to reflect the average grade of the fraction, and the +110 mm size fractions from site 3, as they were insufficient in mass to be considered. The average grade determined from each sample and size fraction is given in Table 1. The metal grade showed some differences with particle size for any given ore domain. However, grades tend to vary more significantly with particle size for gold ores in comparison with the nickel ore. This may partly be due to the so-called “nugget effect” derived from sampling inconsistencies, which may spike Au concentrations in some samples [20]. Moreover, according to Gy’s sampling theory, a low average grade combined with large particle-level variability inherently produces high relative variance in assay results for gold ores. Nevertheless, no systematic and reliable trend in grade was observed with decreasing or increasing particle size. In addition, although there are differences in mineralogy from one ore domain to the other, the varied mineralogy does not appear to lead to different grade-by-size deportment (Table 1). It is evident that grade by size alone is unlikely to result in significant value generation for the ores investigated. Thus, particle size-based separation would result in only a minor upgrade in the material and may lead to rejection of significant proportions of metal.

Table 1.

Average Au and Ni head grade for each size fraction used in the study.

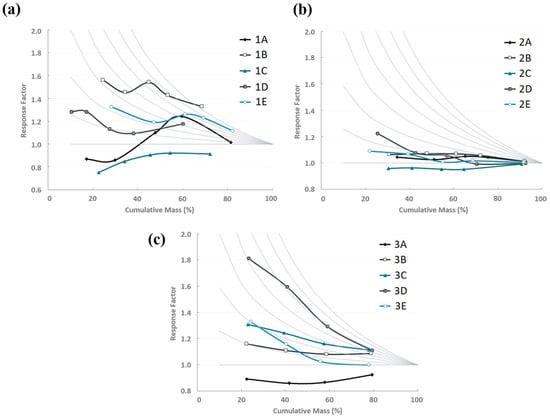

Response Rankings (RRs) were calculated for all samples tested and indicate the propensity for grade to deport to finer fractions during breakage. A larger RR relates to greater deportment to the fines, while a negative RR is either indicative of either deportment to the coarser sizes or erratic data. The standard deviation displays how well the data fits the RR model and thus the confidence in the RR value generated, <0.1 for most metals is desired, while <0.2 for Au is acceptable. As can be seen from the response factor (RF) values presented in Figure 6, the gold operations have far more varied results from each domain than seen in the nickel samples. This correlates well with both expectations and previous investigations due to the sporadic distribution of gold and the significant variance in association between ore domains and geological structures. Likewise, nickel deportment tends to be far more predictable and consistent as the distribution and mineral associations are more uniform. A further guide to screening amenability is that RRs between 50 and 80 represent a moderate response, while those above 80 represent a high response [21]. The nickel samples produced a very weak deportment of grade to the finer fractions, suggesting little benefit to screening alone. In contrast to gold ore, nickel minerals are finely and uniformly distributed, chemically bound, and do not concentrate predominantly by size during crushing and grinding cycles. Additionally, host gangue minerals (e.g., talc, serpentine, or chlorite) and nickel sulfide minerals may have similar physical characteristics such as hardness and density, which minimizes selective breakage or size-based separation of nickel minerals during milling or grinding processes. Among the gold ore domains, 3C displayed a moderate response, and 1B, 1E, and 3D showed high screening potential, while the remaining domains returned either limited deportment of metal to the fines (small positive values) or the coarser fractions (small negative values) (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Response factor plots for the bulk samples of sites, (a) 1, (b) 2, and (c) 3.

Table 2.

RRs generated from the two assay data sets for each sample.

With respect to the average grades returned from the individual rock samples, some showed very similar values (<5% difference) compared to those from the specific grade-by-size samples, while others varied greatly (>100% difference). The differences across size fractions illustrate the variability between the two methods. As would be expected, the correlation of the finer size fractions (where 100 particles represent less total mass) was generally poorer, although this was not always the case. In many cases, the +45 mm size fractions generated a significant difference between the values, even though the total rock mass was more than 25 kg. Equally, the split values and triplicate assays in the grade-by-size samples displayed significant variance. While these impacts were generally more severe in the gold samples, similar trends were observed in the nickel samples. These observations suggest grade-by-size data must be specifically collected to ensure confidence but also underline the importance of a targeted and thorough sampling protocol. Where sampling interferes with the representativeness of the data, it severely compromises the value of the exercise. Interestingly, while there were significant and inconsistent differences between the two grade data sets, using either did not have a major impact on the indicated grade by size amenability. This may be that only a single data source was used for the coarsest (+110 and −110 + 70 mm) and finest size fractions (−9.5 mm) as these would have the greatest impact. Table 2 contains the RRs (RR = ∑(Gi × Si)) generated from each data set for each sample. While the magnitude varied, the region of the RR spectrum that each sample fell under remained the same.

3.4. Individual Particle Sorting

External ores sorting vendors were engaged in the individual and bulk particle sorting tests. The test works were conducted on each ore domain and size fraction to establish amenability to particle sorting. Yield–Recovery curves were compared against each sensor used (including XRT, 3D Laser, Induction, and Color Camera), and programs that resulted in better outcomes were selected. Overall, Induction and XRT were found to be suitable for most ores, as they provided improved sorting efficiency and higher upgrade potential.

For one of the gold mining participants (site 1), all ore domain and size fractions investigated showed high potential upgrade to sensor-based sorting (ranging from 1.45–4.20×), suggesting more than double the feed Au grade could be achieved in the product in most cases (Table 3). Au recoveries of 70%–80% were achieved in about 30%–40% of the mass for the 5 ore domains, although no obvious trend in upgrade with particle size was observed. The theoretical sorting amenability data shows a high potential for samples A-D as can be seen from Table 3. Sample E was predicted to respond poorly to sorting, although the actual sorting results suggest a reasonable upgrade. This could be partly due to the low head grade of the material, with the product stream grade expected to be lower than the cut-off grade.

Table 3.

Comparisons of measured (ideal) sorting for each ore domain with actual sensor-based single-particle sorting for site 1.

The individual particle sorting results show that the nickel ore sample sets (site 2) possess significant upgrade potential using either induction or XRT systems (Table 4). Both XRT and induction worked well for all samples, with one being slightly better than the other in most cases. Different size fractions from the same sample responded similarly, there was no significant trend in sorting amenability by size, although a slight upgrade may be seen for finer size fractions (Table 4). Some samples displayed mildly better results than others, but overall, all of them showed significant potential for sorting. Generally, the actual single particle sorting indicates that the average product grade was more than 2 times that of the feed for most ore domains and size fractions. XRT appears to be the best sensor for ore domains A–C, while induction is more suited for domains D and E. These results show some correlation with the mineralogical data obtained by XRD.

Table 4.

Comparisons of measured (ideal) sorting for each ore domain with actual sensor-based single-particle sorting for site 2.

Comparisons of measured theoretical sorting (based on 100 rocks) and actual single-particle sensor-based sorting results for each ore domain and 4 size fractions (for site 3) are shown in Table 5. Individual particle sorting showed poor correlation between sensor response and gold grade for all ore domains. Although no meaningful grade-recovery curve could be obtained for the sensor-based single-particle sorting, the theoretical amenability results suggest high potential. These outcomes need to be re-investigated further to establish why there are discrepancies between theoretical and actual amenability outcomes.

Table 5.

Comparisons of measured (ideal) sorting for each ore domain with actual sensor-based single-particle sorting for site 3.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the amenability of various ores from various operations to screening and particle sorting was investigated. The screening data revealed that metal grade varied to some extent, albeit not systematic with particle size for the ores investigated. Grade-by-size analysis suggested the nickel samples produced a very weak deportment of grade to the finer fractions, suggesting little benefit to screening alone. Among the gold ore domains, one ore type (3C) displayed a moderate response and three others (1B, 1E, and 3D) showed high screening potential, while the remaining domains returned either limited deportment of metal to the fines (small positive values) or the coarser fractions (small negative values). It is demonstrated that screening alone is unlikely to result in significant savings/value generation from these ore domains. The sorting test works indicated varying degrees of ore amenability to coarse gangue rejection depending on ore type. Among the two gold ore participants, better results were obtained for one site (No. 1), in which case all ore domain and size fractions investigated showed high potential upgrade of up to 4× that may lead to significant savings. In the case of the samples from the other gold mining participant (site No. 3), poor correlation between sensor response and gold grade was observed for most ore domains. This suggests that all samples from this site showed little amenability to particle sorting. On the other hand, the nickel ores (site No. 2) tested in this study responded remarkably well to sorting, indicating significant economic benefits. Generally, the average product Ni grade was more than 2× that of the feed for most ore domains and size fractions studied. It has been concluded that induction and XRT sensor technologies are suitable for most ores, as they deliver improved sorting efficiency and higher upgrade potential. In nickel ores, induction sorting is effective due to the strong conductivity of sulfides like pyrrhotite, while XRT also performs well where density contrasts exist between nickel minerals and the talc–serpentine gangue. In the gold ores, XRT provides clear discrimination based on density differences between gold-bearing phases and surrounding silicates, and induction is effective where gold is associated with conductive sulfides.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D. and B.T.; methodology, L.D. and B.T.; formal analysis, L.D., B.T. and G.S.; investigation, B.T. and G.S.; resources, L.D.; data curation, G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S. and B.T.; writing—review and editing, B.T. and L.D.; supervision, B.T. and L.D.; project administration, B.T. and L.D.; funding acquisition, L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The financial assistance of the Cooperative Research Centre for Optimizing Resource Extraction (CRC ORE) grant number KH-007 and Curtin University, Australia, is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbadi, A.; Mucsi, G. A review on complex utilization of mine tailings: Recovery of rare earth elements and residue valorization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larona, S.T.; Tsuyoshi, A. Future availability of mineral resources: Ultimate reserves and total material requirement. Miner. Econ. 2023, 36, 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.E.; Razo, I.; Lazaro, I. Water footprint for mining process: A proposed method to improve water management in mining operations. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 8, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edraki, M.; Baumgartl, T.; Manlapig, E.; Bradshaw, D.; Franks, D.M.; Moran, C.J. Designing mine tailings for better environmental, social and economic outcomes: A review of alternative approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromans, D. Mineral comminution: Energy efficiency considerations. Miner. Eng. 2008, 21, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, R.A. Step change in the context of comminution. Miner. Eng. 2013, 44, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, P. Australian Water Commission, Framework for Assessing Local and Cumulative Effects of Mining on Groundwater Resources; Report 7; National Water Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.J.; Bearman, R.A. Coarse waste rejection through size-based separation. Miner. Eng. 2014, 62, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siong, J.; Duffy, K.; Valery, W.; Tabosa, E.; Pyle, L. Integrating pre-concentration technologies to maximise resource and eco-efficiency. In Proceedings of the 63rd Conference of Metallurgists, COM 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, G.; Hilden, M.; Powell, M. Early rejection of gangue—How much energy will it cost to save energy? In Comminution ’12; Wills, B., Ed.; Mineral Engineering: Cape Town, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Salter, J.D.; Wyatt, N.P.G. Sorting in the minerals industry: Past, present and future. Miner. Eng. 1991, 4, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, B.A.; Napier-Munn, T. Chapter 14—Ore sorting. In Wills’ Mineral Processing Technology: An Introduction to the Practical Aspects of Ore Treatment and Mineral Recovery; Napier-Munn, B.A.W., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wotruba, H.; Harbeck, H. Sensor-based sorting. In Ullmans Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, R.; Grimes, A. The application of pre-concentration by screening at Bougainville copper limited. In Proceedings of the AusIMM Mineral Development Symposium, Madang, Papua New Guinea, 3–13 November 1986. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, T.D.H.; Eksteen, J.J.; Bode, P. Assessing the amenability of a free milling gold ore to coarse particle gangue rejection. Miner. Eng. 2018, 120, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C. Revision of the current methodology for characterizing grade by size responses. In CRC ORE Technical Report TR22; CRC for Optimizing Resource Extraction: Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bellusci, N.; Taylor, P.R.; Spiller, D.R.; Braman, V. Coarse beneficiation of Trona ore by sensor-based sorting. Min. Metall. Explor. 2022, 39, 2179–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kroell, N.; Feil, A.; Greiff, K. Sensor-based sorting. In Handbook of Recycling; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wikedzi, A.; Saquran, S.; Leißner, T.; Peuker, U.A.; Mutze, T. Breakage characterization of gold ore components. Miner. Eng. 2020, 151, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominy, S.C. Predicting the unpredictable—Evaluating high-nugget effect gold deposits. In Mineral Resource and Ore Reserve Estimation; The AusIMM: Carlton South, Australia, 2014; pp. 659–678. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, S.G. Driving Productivity by Increasing Feed Quality Through Application of Innovative Grade Engineering® Technologies; Cooperative Research Centre for Optimising Resource Extraction (CRC ORE): Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.