Characteristics of Pore–Throat Structures and Impact on Sealing Capacity in the Roof of Chang 73 Shale Oil Reservoir, Ordos Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Basic Geological Characteristics

3. Samples and Methods

3.1. XRD

3.2. SEM

3.3. HPMI and N2 Adsorption

- r—pore–throat radius (μm),

- σ—surface tension of mercury (0.485 N/m),

- θ—contact angle between mercury and the rock surface (140°),

- P—applied pressure (MPa).

3.4. Gas Breakthrough Pressure

4. Results

4.1. Mineralogical Characteristics of the Overlying Strata

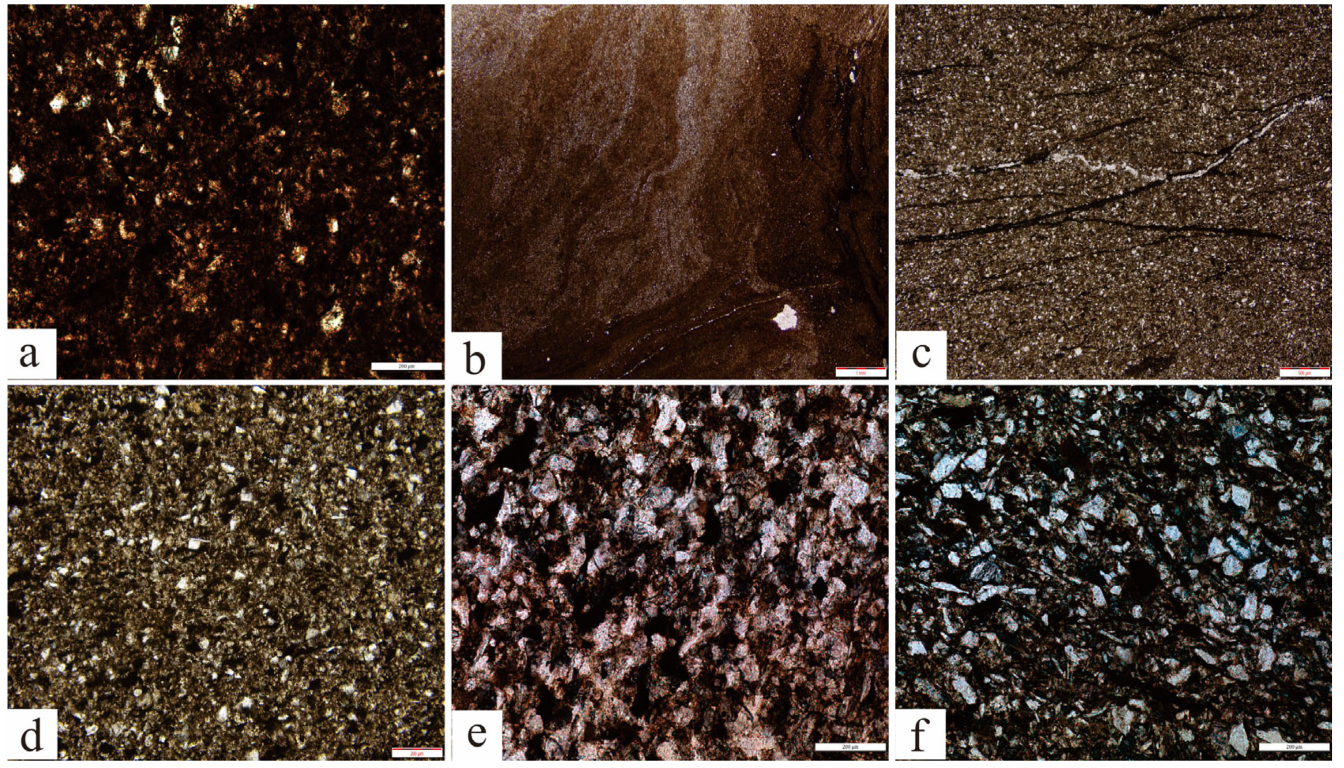

4.1.1. Lithological Composition and Structural Characteristics

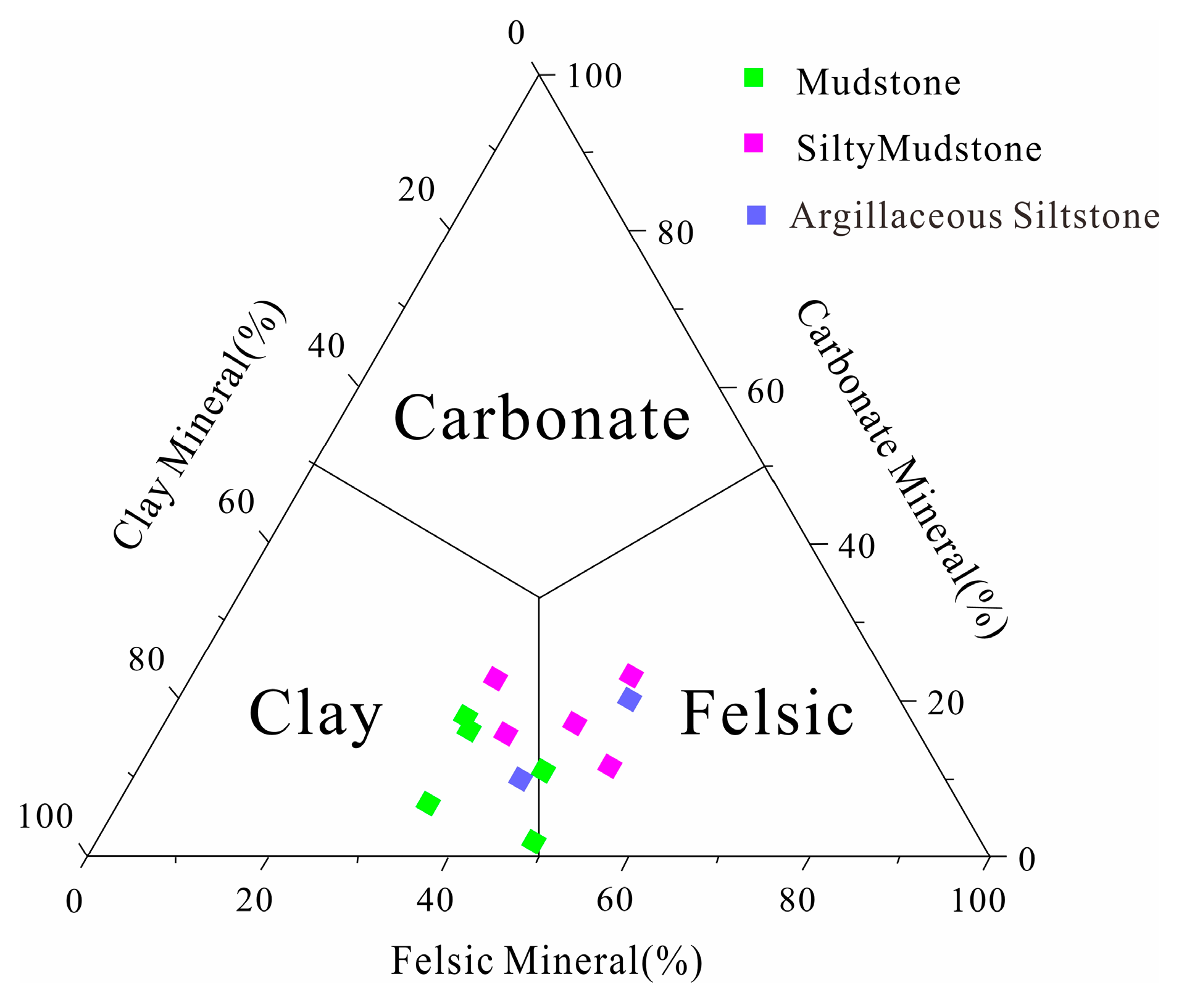

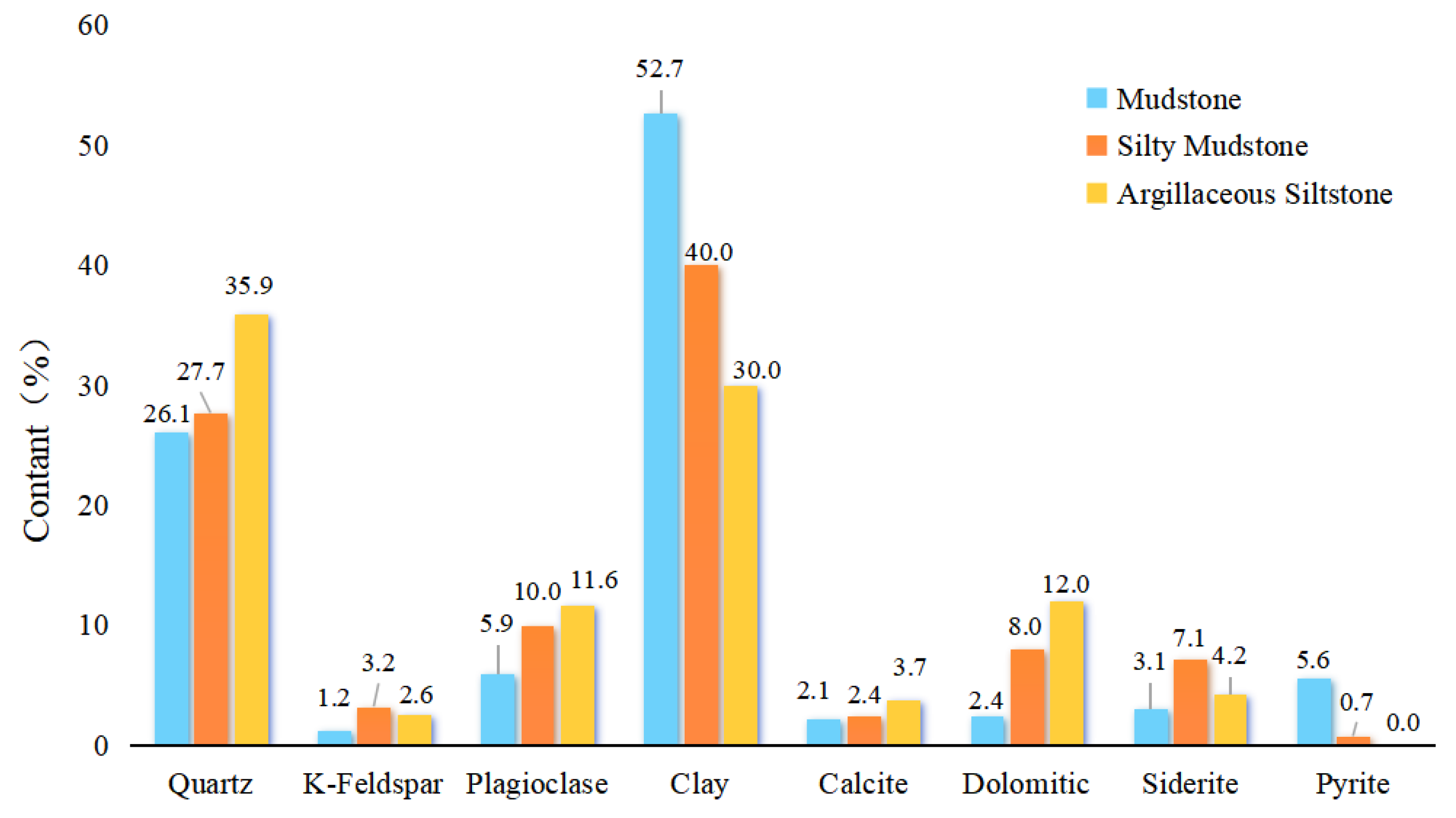

4.1.2. Mineralogical Characteristics of the Rock

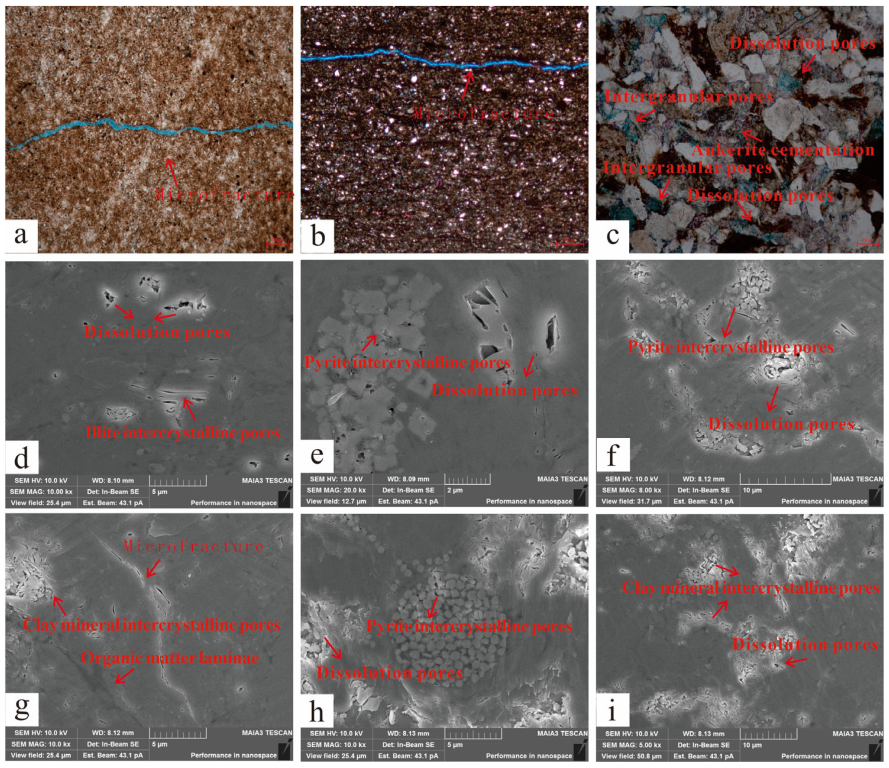

4.2. Pore–Throat Structural Characteristics of the Overlying Strata

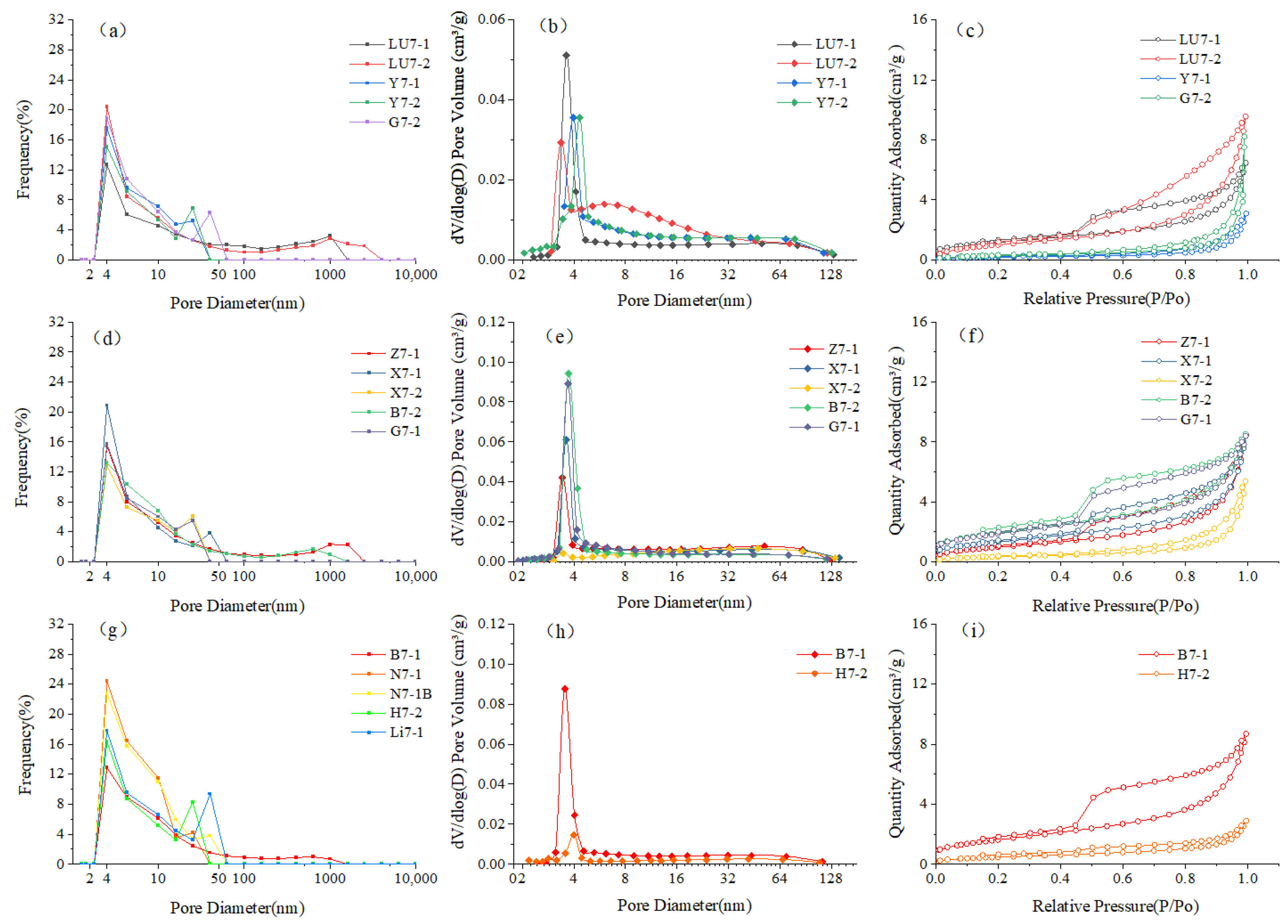

4.2.1. Laminated Mudstone

4.2.2. Laminated Silty Mudstone

4.2.3. Argillaceous Siltstone

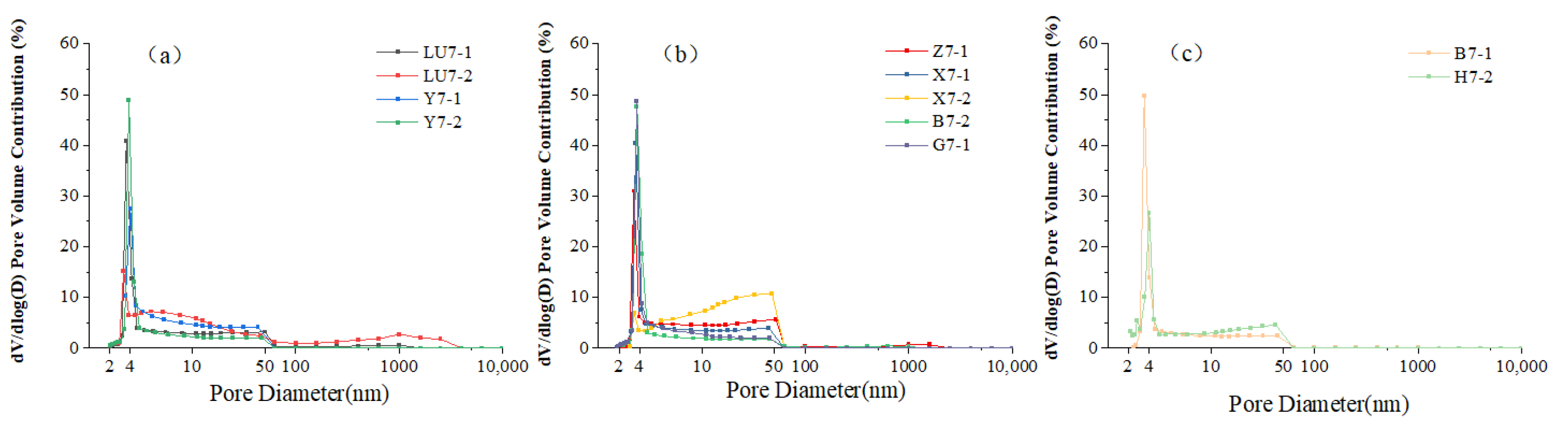

4.3. Integration of HPMI and N2 Adsorption for Full-Range Pore-Size Distribution

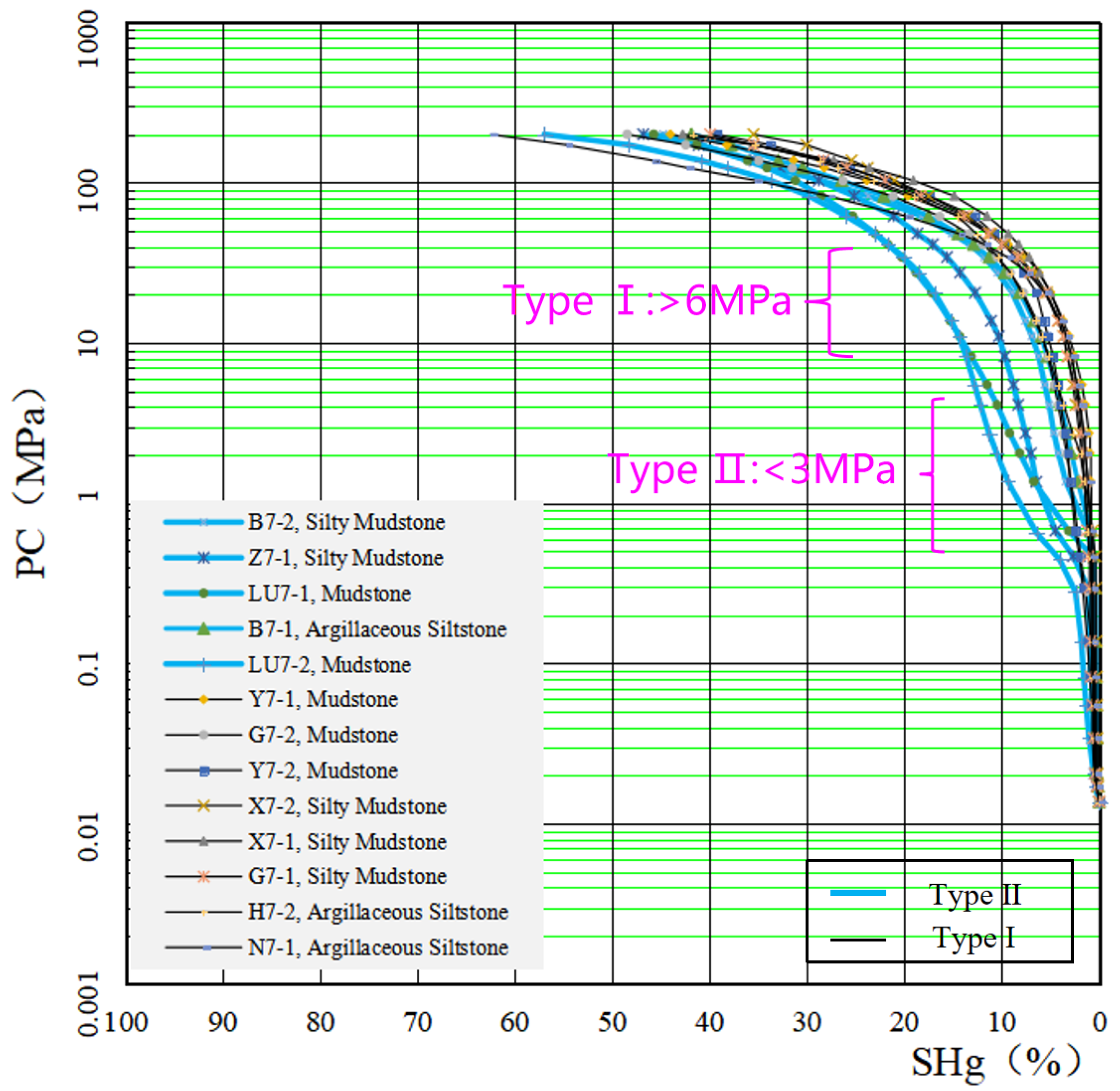

4.4. Breakthrough Pressure

5. Discussion

5.1. Influence of Pore–Throat Structure on Sealing Capacity

5.1.1. Displacement Pressure

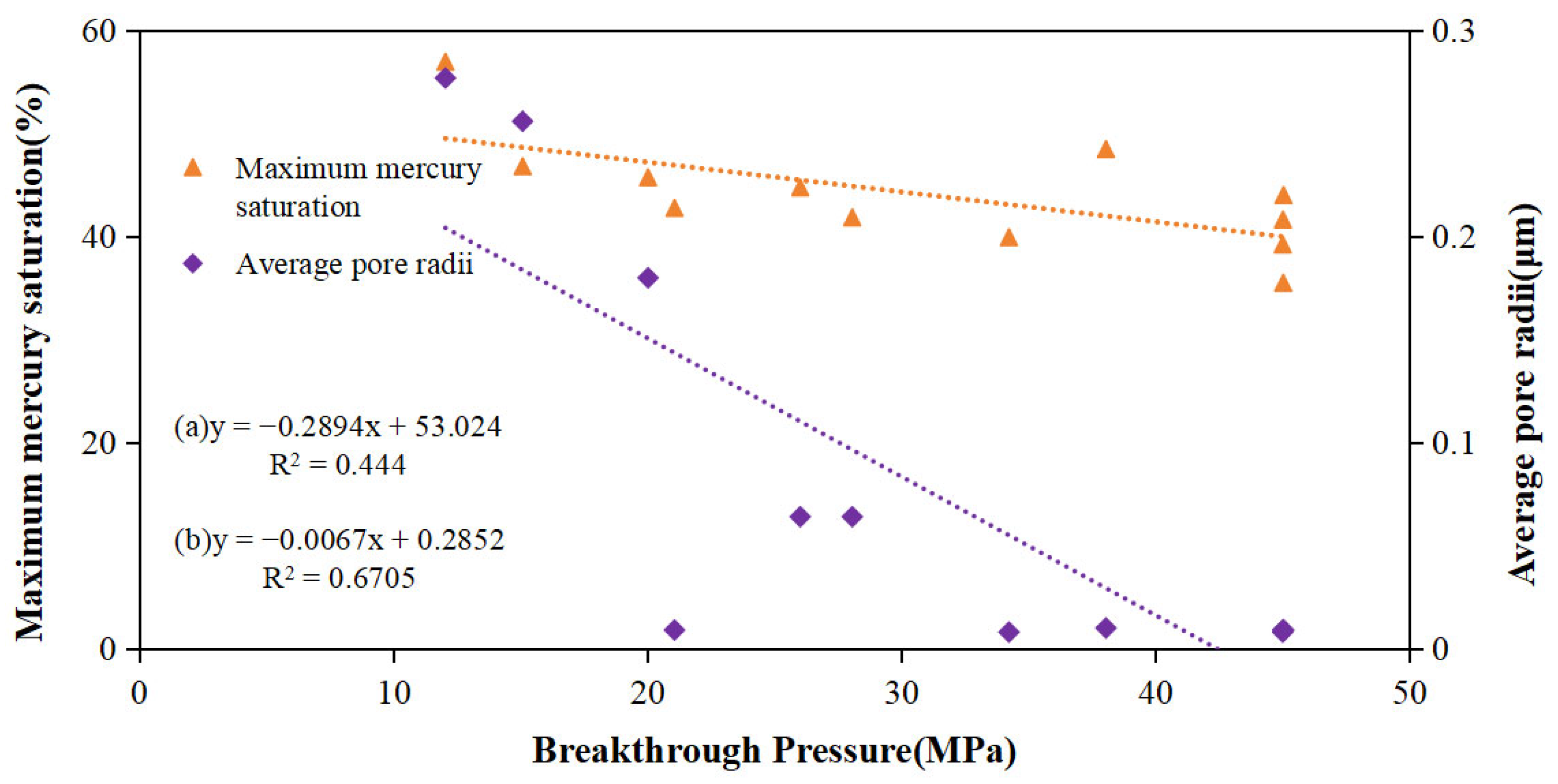

5.1.2. Correlation

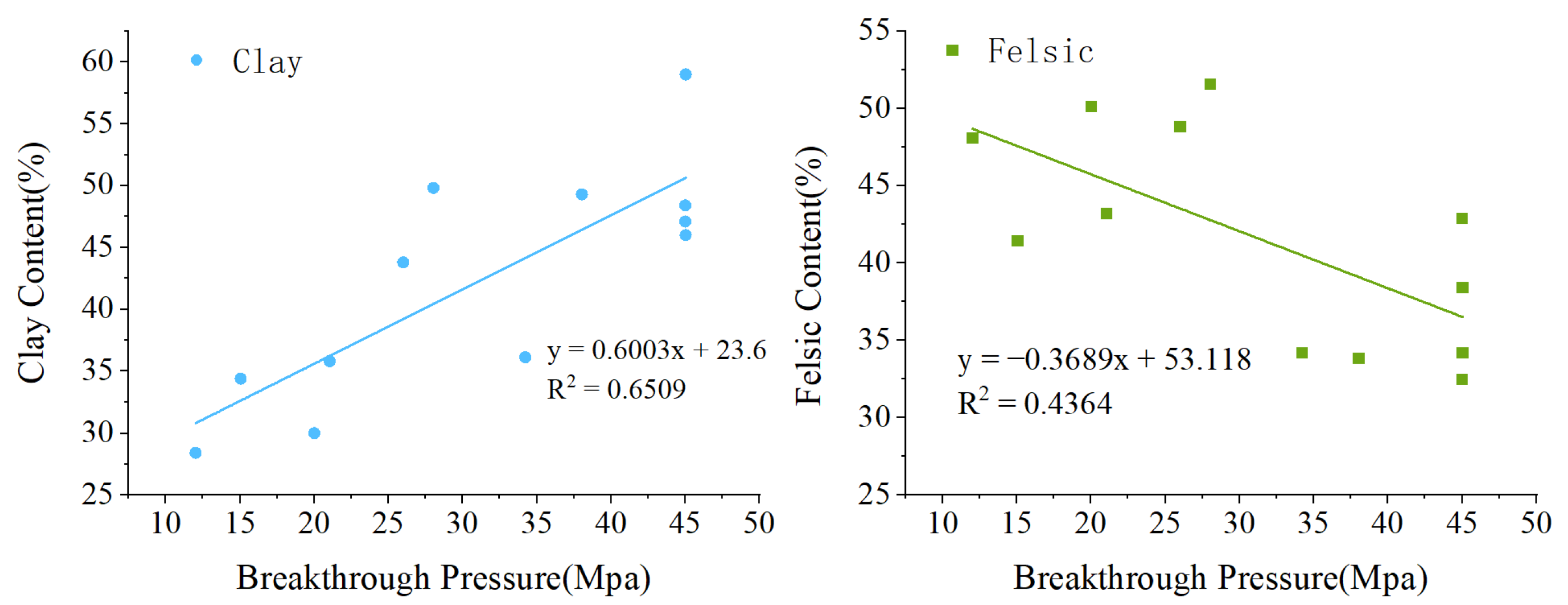

5.2. Influence of Mineral Composition on Sealing Capacity

- (1)

- Clay Mineral Composition

- (2)

- Felsic Mineral Components

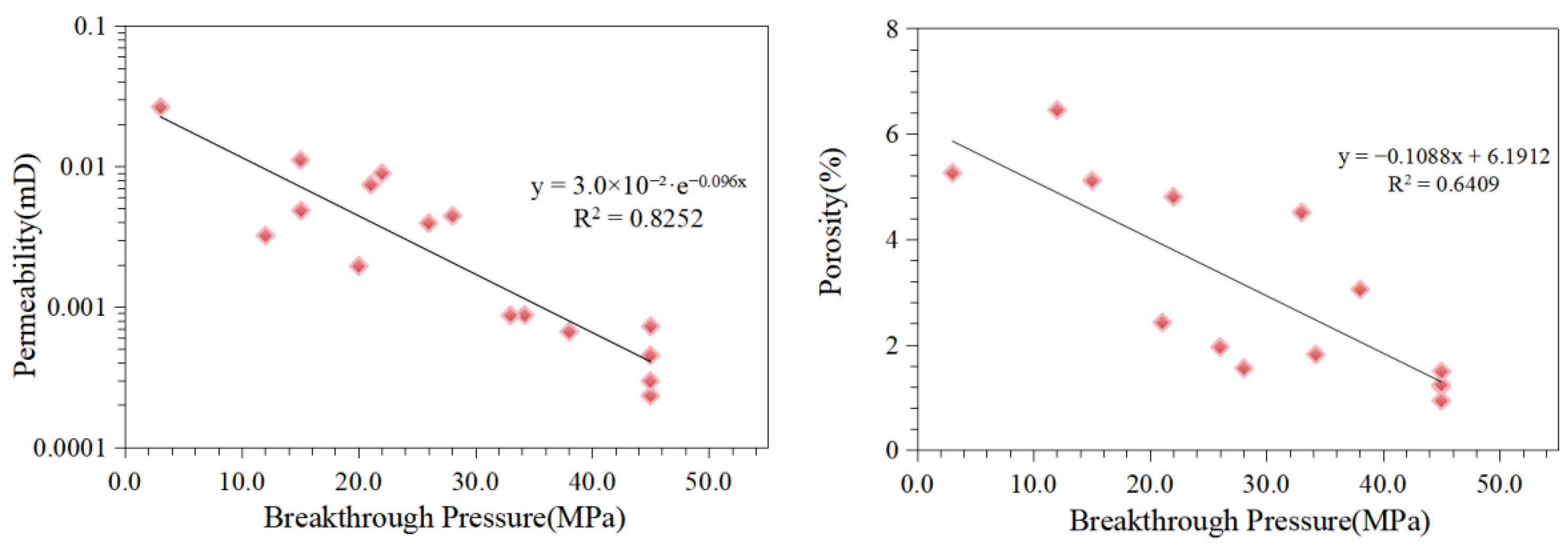

5.3. Influence of Petrophysical Properties on Overlying Strata Sealing Capacity

5.4. Uncertainty and Limitations

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The lithofacies of the overlying strata in the Chang 73 shale oil interval of the Ordos Basin can be classified into three types: mudstone, silty mudstone, and muddy siltstone. Based on mineral composition, these strata are primarily composed of clay-rich rocks and quartz–feldspar-rich rocks.

- (2)

- The pore types observed in the study area samples are classified into organic and inorganic pores. Inorganic pores include five subtypes: dissolution pores, intergranular pores, clay mineral interlayer pores, intragranular pores, and microfractures. The pore size distribution is relatively narrow, dominated by mesopores (2–50 nm) with a minor presence of macropores. Pore morphologies are primarily plate-like and wedge-shaped slit pores, exhibiting poor connectivity, which hinders hydrocarbon migration.

- (3)

- The average breakthrough pressures of the three lithologies in the Chang 73 shale oil overlying strata exceed 15 MPa, indicating strong sealing capacity. Correlation analyses between breakthrough pressure and pore–throat structure, mineral composition, diagenetic processes, and petrophysical properties reveal that the porosity-enhancing effect caused by the dissolution of siliceous–feldspathic minerals compromises the sealing ability. In contrast, complex pore–throat structures, compaction and cementation of clay minerals, and poor petrophysical properties lead to densification of the overlying strata, providing effective hydrocarbon sealing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Gao, B.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Liang, X.; Wang, R. Research progress and key scientific issues of continental shale oil in China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2021, 42, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hu, S.; Hou, L.; Yang, T.; Li, X.; Guo, B.; Yang, Z. Types and resource potential of continental shale oil in China and its boundary with tight oil. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Lyu, C.; Feng, S.; Zhou, Q.; Xin, H.; Xiao, Y.; Li, C.; Dan, W. Lamina combination characteristics and differential shale oil enrichment mechanisms of continental organic-rich shale: A case study of Triassic Yanchang Formation Chang 73 sub-member, Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liu, C. Characteristics and exploration targets of Chang 7 shale oil in Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, F.; Zou, C.; Yang, Z. Geological theory and exploration & development practice of hydrocarbon accumulation inside continental source kitchens. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Niu, X.; Dan, W.; Feng, S.; Liang, X.; Xin, H.; You, Y. The geological characteristics and the progress on exploration and development of shale oil in Chang7 Member of Mesozoic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2019, 24, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Li, S.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Li, S. Breakthrough of risk exploration for Class II shale oil in Chang 7 member of the Yanchang Formation and its significance in the Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2020, 25, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yang, W. Discovery and resource potential of shale oil of Chang 7 member, Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2021, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Niu, X.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J. Breakthrough and significance of risk exploration in the 3rd Sub-member, 7th Member of Yanchang Formation in Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2022, 43, 760–769, 787. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Shi, B.; Guo, C.; Chao, G.; Fenfei, B.; Gang, L.; Jintao, Y.; Jie, X. Characteristics of shale oil reservoir and exploration prospects in the third sub-member of the seventh member of the Triassic Yanchang Formation in Fuxian area, Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2023, 28, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, Q.; Pan, S.; Zhou, X.; Guo, R. Influence of intrasource micro-migration of hydrocarbons on the differential enrichment of laminated type shale oil: A case study of the third sub-member of the seventh member of the Triassic Yanchang Formation in Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2023, 28, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, D.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Geological understanding and exploration potential of shale oil in the third submember of the seventh member of Yanchang Formation in Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2024, 29, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, W.; Bian, C.; Liu, X.; Pu, X.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, S. Role of preservation conditions on enrichment and fluidity maintenance of medium to high maturity lacustrine shale oil. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Bian, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Dong, J.; Wang, K.; Zeng, X. Organic matter transformation ratio, hydrocarbon expulsion efficiency and shale oil enrichment type in Chang 73 shale of Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhu, R.; Liang, X.; Shen, Y. Several issues worthy of attention in current lacustrine shale oil exploration and development. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Yang, W.; Wang, Q.; Zuo, R.S.; Cai, J.F.; Cui, Z.J.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Gu, X.M. Sealing property of roof and floor of Wufeng Formation-Longmaxi Formation and its influence on shale gas differential enrichment in Sichuan Basin and its surrounding areas. Mar. Orig. Pet. Geol. 2020, 25, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, W.; Su, Y.; Zeng, X.; Fu, X.; Guan, M.; Li, S. Sealing capacity evaluation of the roof and floor for the Qingshankou Formation in the Qijia-Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin and its preservation of shale oil. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2025, 36, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Hu, D.; Yu, L.; Lu, L.; He, C.; Liu, W.; Lu, X. Study on the micro mechanism of shale self-sealing and shale gas preservation. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2023, 45, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fan, T.; Gao, Z.; Gu, Y.; Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Meng, M.; et al. Identification and characteristic analysis of carbonate cap rock: A case study from the Lower-Middle Ordovician Yingshan Formation in Tahe oilfield, Tarim Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 164, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Jin, Z.; Bian, R. The “source-cap hydrocarbon-controlling” enrichment of shale gas in Upper Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation of Sichuan Basin and its periphery. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, R.; Hu, S.; Hou, L.; Wu, S. Accumulation contribution differences between lacustrine organic-rich shales and mudstones and their significance in shale oil evaluation. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1160–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wu, T.; Lyu, Y.; Liu, S.; Tian, H.; Lu, M. Research status and development trend of the reservoir caprock sealing properties. Oil Gas Geol. 2018, 39, 454–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, J.E.; Dewers, T.A.; McPherson, B.J.; Petrusak, R.; Chidsey, T.C., Jr.; Rinehart, A.J.; Mozley, P.S. Pore networks in continental and marine mudstones: Characteristics and controls on sealing behavior. Geosphere 2011, 7, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, D. Comprehensive review of caprock-sealing mechanisms for geologic carbon sequestration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Wu, H.; Leung, C.; Tian, J. A multiphysical-geochemical coupling model for caprock sealing efficiency in CO2 geosequestration. Deep. Undergr. Sci. Eng. 2023, 2, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Fahimpour, J.; Ali, M.; Keshavarz, A.; Iglauer, S. Capillary sealing efficiency analysis of caprocks: Implication for hydrogen geological storage. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 4065–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, P.J.; Faulkner, D.R.; Worden, R.H.; Aplin, A.C.; Butcher, A.R.; Iliffe, J. Experimental measurement of, and controls on, permeability and permeability anisotropy of caprocks from the CO2 storage project at the Krechba Field, Algeria. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2011, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Lin, C.; Dong, C.; Elsworth, D.; Wu, S.; Wang, X.; Sun, X. Determination of the critical flow pore diameter of shale caprock. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 112, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, D.N.; Santamarina, J.C. CO2 breakthrough—Caprock sealing efficiency and integrity for carbon geological storage. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2017, 66, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R.F.; Kaldi, J.G. Evaluating Seal Capacity of Cap Rocks and Intraformational Barriers for CO2 Containment; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Vilarrasa, V.; Makhnenko, R.Y. Laboratory-scale assessment of CO2 sealing potential of heterogeneous caprock. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2025WR040339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Sun, Y. Tectonic background of Ordos Basin and its controlling role for basin evolution and energy mineral deposits. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2009, 27, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, S. Upper Triassic–Jurassic sequence stratigraphy and its structural controls in the western Ordos Basin, China. Basin Res. 2000, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Jin, Z.; Van Loon, A.J.; Han, Z.; Fan, A. Climatic and tectonic controls of lacustrine hyperpycnite origination in the Late Triassic Ordos Basin, central China: Implications for unconventional petroleum development. Aapg Bull. 2017, 101, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, M. Temporo-spatial coordinates of evolution of the Ordos Basin and its mineralization responses. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. Ed. 2008, 82, 1229–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Hui, X.; Cheng, D. Progress and prospects of shale oil exploration and development in the seventh member of Yanchang Formation in Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2023, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ma, Y. Geology of the Chang 7 Member oil shale of the Yanchang Formation of the Ordos Basin in central north China. Pet. Geosci. 2020, 26, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhu, R.; Mao, Z.; Li, S. Accumulation of unconventional petroleum resources and their coexistence characteristics in Chang7 shale formations of Ordos Basin in central China. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 13, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, K.; Li, K.; Cao, Y.; Lin, M.; Niu, X.; Zhu, R.; Wei, X.; You, Y.; Liang, X.; Feng, S. Laminae combination and shale oil enrichment patterns of Chang 73 sub-member organic-rich shales in the Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SY/T 5163–2018; Analytical Method for Clay Minerals and Common Non-Clay Minerals in Sedimentary Rocks. National Energy Administration: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 16594–2008; General Rules for Measurement of Length in Micron Scale by SEM. Standardization Administration of China/State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 29171–2012; Rock capillary pressure measurement. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China & Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB/T 19587–2017; Determination of the Specific Surface Area of Solids by Gas Adsorption Using the BET Method. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- GB/T 21650.2-2008; Pore Size Distribution and Porosity of Solid Materials by Mercury Porosimetry and Gas Adsorption—Part 2: Analysis of Mesopores and Macropores by Gas Adsorption. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- SY/T 5748–2013; Specification for Division of Diagenetic Stages of Clastic Rocks. National Energy Administration: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Picard, M.D. Classification of fine-grained sedimentary rocks. J. Sediment. Res. 1971, 41, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; Liu, X.; Jin, Z.; Lai, J. The heterogeneity of pore structure in lacustrine shales: Insights from multifractal analysis using N2 adsorption and mercury intrusion. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 114, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Chen, H.; Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; Bao, Y. Evaluation standard of mudstone caprock combining specific surface area and breakthrough pressure. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2011, 33, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiltinan, E.J.; Espinoza, D.N.; Cockrell, L.P.; Cardenas, M.B. Textural and compositional controls on mudrock breakthrough pressure and permeability. Adv. Water Resour. 2018, 121, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulin, P.F.; Bretonnier, P.; Vassil, V.; Samouillet, A.; Fleury, M.; Lombard, J.M. Sealing efficiency of caprocks: Experimental investigation of entry pressure measurement methods. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2013, 48, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lü, X.; Quan, H.; Qian, W.; Mu, X.; Chen, K.; Wang, Z.; Bai, Z. Influence factors and an evaluation method about breakthrough pressure of carbonate rocks: An experimental study on the Ordovician of carbonate rock from the Kalpin area, Tarim Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 104, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Pan, Z.; Connell, L.D.; Liu, B.; Fu, X.; Xue, Z. Gas breakthrough pressure of tight rocks: A review of experimental methods and data. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 81, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, Q.; Tan, Y.; Yu, T.; Li, X.; Li, X. Experimental measurements and characterization models of caprock breakthrough pressure for CO2 geological storage. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 252, 104732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Y. Breakthrough pressure anisotropy and intra-source migration model of crude oil in shale. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 135, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, Q. CO2 breakthrough pressure and permeability for unsaturated low-permeability sandstone of the Ordos Basin. J. Hydrol. 2017, 550, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, M. A critical review of breakthrough pressure for tight rocks and relevant factors. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 100, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ning, Z.; Kong, D.; Liu, H. Pore Structure of Shales from High Pressure Mercury Injection and Nitrogen Adsorption Method. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2013, 24, 450–455. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; Fang, Q.; Li, A.; Li, Z.; Han, J.; Dang, X.; Han, W. Accurate characterization of full pore size distribution of tight sandstones by low-temperature nitrogen gas adsorption and high-pressure mercury intrusion combination method. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Sun, W.; Tao, R.; Luo, B.; Chen, L.; Ren, D. Pore–throat structure and fractal characteristics of tight sandstones in Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 120, 104573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Meng, X.; Pu, R. Impacts of mineralogy and pore throat structure on the movable fluid of tight sandstone gas reservoirs in coal measure strata: A case study of the Shanxi formation along the southeastern margin of the Ordos Basin. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2023, 220, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fan, T.; Gomez-Rivas, E.; Travé, A.; Cao, Q.; Gao, Z.; Wang, S.; Kang, Z. Impact of diagenesis on the pore evolution and sealing capacity of carbonate cap rocks in the Tarim Basin, China. AAPG Bull. 2022, 106, 2471–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shi, W.; Xie, X.; Zhang, W.; Qin, S.; Liu, K.; Busbey, A.B. Clay mineral content, type, and their effects on pore throat structure and reservoir properties: Insight from the Permian tight sandstones in the Hangjinqi area, north Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 115, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiu, B.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; He, M. Influence of clay minerals and cementation on pore throat of tight sandstone gas reservoir in the eastern Ordos Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 87, 103762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Z. Breaking pressure of gas cap rocks. Oil Gas Geol. 2000, 21, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Bian, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, K.; Liu, W.; Zhang, B.; Lei, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. Enrichment factors of movable hydrocarbons in lacustrine shale oil and exploration potential of shale oil in Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lithology | Description | Clay Content (%) | Silt Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mudstone | Dark gray to grayish-black mudstone | >65 | <35 |

| Silty Mudstone | Dark gray silty mudstone | 50–65 | 35–50 |

| Argillaceous Siltstone | Drgillaceous siltstone | 35–50 | 50–65 |

| Sample | Φ (%) | K (×10−3 μm2) | Pb (Mpa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mudstone | LU7-1 | 0.817 | 0.00195 | 20.02 |

| LU7-2 | 6.453 | 0.00321 | 12.04 | |

| Y7-1 | 1.204 | 0.000451 | >45 | |

| Y7-2 | 1.240 | 0.000233 | >45 | |

| G7-2 | 3.046 | 0.000665 | 38.05 | |

| Silty Mudstone | X7-1 | 2.419 | 0.007394 | 21.06 |

| X7-2 | 0.936 | 0.000296 | >45 | |

| G7-1 | 1.813 | 0.000873 | 34.23 | |

| B7-2 | 1.953 | 0.00394 | 26.01 | |

| Z7-1 | 1.342 | 0.00484 | 15.08 | |

| Argillaceous Siltstone | H7-2 | 1.490 | 0.000726 | 45.02 |

| Li7-1 | 5.110 | 0.01108 | 15.03 | |

| N7-1 | 5.257 | 0.02634 | 3.05 | |

| N7-1B | 4.804 | 0.00892 | 22.01 | |

| B7-1 | 1.551 | 0.00444 | 28.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ).

Share and Cite

Jia, W.; Du, G.; Bian, C.; Dang, W.; Dong, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, L.; Wen, Y.; Pan, B. Characteristics of Pore–Throat Structures and Impact on Sealing Capacity in the Roof of Chang 73 Shale Oil Reservoir, Ordos Basin. Minerals 2026, 16, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010012

Jia W, Du G, Bian C, Dang W, Dong J, Wang H, Zhu L, Wen Y, Pan B. Characteristics of Pore–Throat Structures and Impact on Sealing Capacity in the Roof of Chang 73 Shale Oil Reservoir, Ordos Basin. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Wenhao, Guichao Du, Congsheng Bian, Wei Dang, Jin Dong, Hao Wang, Lin Zhu, Yifan Wen, and Boyan Pan. 2026. "Characteristics of Pore–Throat Structures and Impact on Sealing Capacity in the Roof of Chang 73 Shale Oil Reservoir, Ordos Basin" Minerals 16, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010012

APA StyleJia, W., Du, G., Bian, C., Dang, W., Dong, J., Wang, H., Zhu, L., Wen, Y., & Pan, B. (2026). Characteristics of Pore–Throat Structures and Impact on Sealing Capacity in the Roof of Chang 73 Shale Oil Reservoir, Ordos Basin. Minerals, 16(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010012