1. Introduction

Bentonites are natural clay deposits composed mainly of smectite group minerals, which are a group of 2:1 layered phyllosilicates, defined as two tetrahedral sheets of silicon oxide sandwiching one octahedral sheet, usually made of aluminium oxide, as in the case of montmorillonite (Mt). Mt is the main mineral type, responsible for the high swelling and exchange capacity in bentonite clay [

1], making it one of the most versatile industrial clays, categorized into swelling and non-swelling types based on their hydration behaviour. Swelling bentonites are particularly important industrially, as they can expand up to twenty times their original volume when in contact with water [

2]. They are widely used as binders for mineral fines, thixotropic agents in drilling fluids, and rheological modifiers in aqueous systems [

2,

3]. However, other clay minerals can also be found in bentonites and are called clay mineral accessories, making their variability highly variable. Kaolinite (Kao), for example, is another common clay mineral, composed of one sheet of silicon oxide and another of aluminium oxide. It is a non-swelling clay mineral, inert and stable.

At first, most bentonite applications relied on their hydrophilic character. However, subsequent studies on clay–organic interactions [

4,

5,

6,

7] led to the development of organophilic clays, obtained by exchanging interlayer inorganic cations with organic cations, typically quaternary ammonium salts [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. This process, also known as organophilization, replaces hydrophilic sites with hydrophobic domains, allowing the clay to disperse and swell in organic media [

4]. The organophilization process enhances compatibility with nonpolar media by replacing exchangeable Na

+ or Ca

2+ ions with organic ammonium cations. This modification increases the interlayer spacing and introduces hydrophobic and van der Waals interaction sites, promoting the adsorption of nonpolar organic molecules. The arrangement of the intercalated surfactant depends on the layer charge density and alkyl chain length, producing monolayer, bilayer, pseudo-trimolecular, or paraffinic configurations [

4,

14,

15]. Longer alkyl chains favour more ordered arrangements, while shorter chains yield disordered structures [

16]. The resulting basal spacing (d

001), determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD), is a key indicator of intercalation efficiency and molecular organization [

17].

The resulting materials, known as organoclays, exhibit swelling behaviour similar to that of natural bentonites in water, but toward organic liquids rather than water. Their properties depend on both the chemical structure of the surfactant and the type of clay mineral, allowing the design of organoclays with specific plasticity, viscosity, and sorption capacity [

18,

19]. This is the reason why organophilic smectites have been widely employed as rheological additives in paints, lubricants, cosmetics, and oil-based drilling fluids [

4,

7,

20,

21]. Their use also expanded to polymer–clay nanocomposites [

8,

20,

21,

22,

23] and environmental remediation, particularly for hydrocarbon adsorption [

5,

10,

24,

25]. Montmorillonite is the main mineral responsible for these behaviours due to its high cation exchange capacity (CEC), layered structure, and large surface area, which enable efficient intercalation and adsorption processes [

18].

In recent years, organophilic montmorillonites (OMt) have garnered increasing attention as low-cost, eco-friendly alternatives to activated carbon for hydrocarbon adsorption [

6,

26]. These materials have shown adsorption capacities reaching up to seven times their own mass, depending on the surfactant type and clay characteristics [

27]. In environmental remediation, organoclays improve filtration efficiency, prevent pore blockage, and reduce the mobility of nonionic organic contaminants (NOCs), thus mitigating hydrocarbon pollution from oil spills, industrial effluents, and pipeline leaks [

5,

6,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Hydrocarbon contamination remains one of the main causes of surface and groundwater degradation worldwide, generating persistent films that hinder oxygen transfer and threaten aquatic ecosystems [

6,

33,

34].

Although many studies have optimized surfactant loading, chain length, or intercalation degree to enhance adsorption [

5,

27], few have systematically addressed the influence of the clay’s intrinsic surface properties—particularly its specific surface area—on solvent adsorption performance. Understanding this relationship is essential to design more efficient, structure-guided sorbents for environmental use.

The present work aims to evaluate the effect of specific surface area on the adsorption of organic solvents by organoclays derived from sodium bentonites. Two clays with similar pore volumes (0.081 and 0.089 cm

3/g) but distinct surface areas (30 and 50 m

2/g) were modified with three quaternary ammonium salts of increasing molar mass and alkyl chain length. The resulting organoclays were characterized by FTIR, XRD, TGA, and SEM, and their swelling and sorption behaviours toward gasoline, diesel, and kerosene were evaluated. These solvents were selected as representative hydrocarbons of different polarities and aromatic contents, typical of real contamination scenarios. In this work, the swelling capacity is described as the increase in volume of a specified mass of clay when placed in contact with a particular liquid (ASTM D5890-19 [

35]). Sorption capacity is the amount of a liquid that can be incorporated in a specific mass of clay (ASTM F726-17 [

36]). These tests have been extensively used in the literature [

9,

27,

37].

The results demonstrate that combining a higher specific surface area with long-chain surfactants enhances interlayer expansion and adsorption efficiency. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to directly correlate bentonite surface area with solvent sorption capacity, providing new insights into the design of high-performance, low-cost organoclays for hydrocarbon remediation.

2. Materials and Methods

Two sodium bentonites were employed in this study to evaluate their oil adsorption performance. The first was a commercial bentonite, Cloisite Na

+ (CL) (Southern Clay Products, Gonzales, TX, USA), and the second was a natural bentonite from Argentina, designated VL. Our group previously reported the detailed mineralogical and physicochemical characteristics of these clays as well as their mineralogy composition by using PDF-2 (ICDD) and ICSD databases [

38]. In that study, we demonstrated that CL consists predominantly of smectite (montmorillonite), whereas VL contains smectite together with kaolinite, quartz, and calcite as accessory minerals. The standard cards used to identify each of the clay minerals can be seen at

Table 1.

The N

2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of both clays exhibited H

3-type hysteresis loops, indicating aggregates of plate-like particles that form slit-shaped pores. The pore volumes, determined by the BET equation, were 0.081 cm

3/g for CL and 0.088 cm

3/g for VL. The BET surface areas were measured as 30 and 50 m

2/g, respectively. The CEC of CL was previously reported as 113 meq/100 g [

39], consistent with typical montmorillonite clays. The CEC of VL was not determined in this work, but its similar adsorption and textural properties suggest a comparable exchange capacity. These clays were selected for their interlayer spacing (1.24 nm) and comparable textural properties, enabling a meaningful comparison of their mineralogical influence on adsorption performance. Clay’s interlayer distance is related to the degree of hydration of the interlayer cations [

40], and since both clays have sodium as exchangeable cation and were prepared and stored in the same way, it is expected that they have the same interlayer distance.

A summary of their main characteristics is presented in

Table 2.

Three quaternary ammonium salts were selected as organomodifiers. Their commercial names are Sunquart CT 50 (Polytechno, Guarulhos, Brazil), Arquad PC (AkzoNobel, Itupeva, Brazil), and Armosoft E (AkzoNobel, Itupeva, Brazil). Their IUPAC names, suppliers, and chemical structures are summarized in

Table 3. These salts were selected for their varying alkyl chain lengths and head-group structures, enabling evaluation of the influence of surfactant chemistry on organophilization efficiency and adsorption performance.

The adsorption experiments were conducted using commercially available Brazilian fuels: gasoline (Shell, São Paulo, Brazil), diesel (Shell, Brazil), kerosene (Apache Ltda., Brazil), toluene (>95%, Química Nova Ltda., Araçatuba, Brazil), and xylene (>98.5%, Química Nova Ltda., Araçatuba, Brazil). All solvents were used as received, without further purification. Deionized water (resistivity ≥ 18 MΩ·cm) was used for all washing and dilution procedures.

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Clay Organophilization

A 20% (w/v) aqueous dispersion of each clay was prepared by dispersing 20 g of clay in 1 L of deionized water under mechanical stirring for 30 min. Subsequently, a quantity of quaternary ammonium salt corresponding to 100 meq/100 g of clay was added to each dispersion, and the dispersions were stirred for an additional 30 min. This proportion was chosen to ensure an excess of surfactant relative to the typical CEC, thus guaranteeing complete replacement of the exchangeable cations. The modification was carried out at room temperature (25 °C) using a mechanical stirrer operating at 1500 rpm.

The dispersions were allowed to rest overnight to facilitate adsorption and ion exchange. The resulting suspensions were then vacuum-filtered, thoroughly washed with distilled water, dried at 60 °C, ground, and sieved through a 200-mesh (75 µm) sieve. Six different organoclays were obtained, and their designations are listed in

Table 4. The resulting solids were stored in desiccators until further characterization.

2.1.2. Characterization

Chemical interactions between the clay and the salts were investigated by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR); basal spacing was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD); morphology was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM); the amount of salt incorporated into the organoclays was quantified by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA); and particle size distribution was determined by laser scattering diffraction.

FTIR: ATR–FTIR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet iS5 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in the range 4000–600 cm−1 with a resolution of 2 cm−1.

XRD: X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained using a MiniFlex 600 diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), operating at 30 kV and 10 mA, scanning from 2θ = 2° to 30° at 2° min−1. The diffraction patterns were also used to calculate the interlayer distance (d001) using Bragg’s law, as in Equation (1), where n is the reflection order, λ is the wavelength of copper irradiation, and θ is the diffraction angle:

SEM: Morphological analyses were carried out using a Cambridge Stereoscan 4040 microscope (FEI Company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) equipped with secondary and backscattered electron detectors.

TGA/DTA: Thermogravimetric and differential thermal analyses were performed on a Pyris Diamond TG/DTA system (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) using platinum crucibles, under an airflow of 100 mL min−1, and a temperature range of 50–800 °C.

Laser Scattering Diffraction was performed using a Mastersizer 2000 Ver, 5.54 (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK), with water as the dispersant and sodium hexametaphosphate, and after sonification, to measure the particle size distribution and specific surface area of pristine clays. Water was chosen as the dispersant because of its interaction with clay particles, as reported in other papers in the literature [

41,

42]. The use of organic solvents can lead to aggregation and particle precipitation, leading to misinterpretation.

2.1.3. Swelling Test (ASTM D5890-19)

The swelling behavior of the clays and organoclays was evaluated according to the Standard Test Method for the Swell Index of Clay Mineral Component of Geosynthetic Clay Liners, D5890-19 [

35], also known as the Foster Swelling Test [

28]. This test was used to evaluate the increase in clay volume after exposure to an organic solvent.

In this test, 1.0 g of each material was slowly added to 50 mL of each of the following organic solvents: gasoline, diesel, kerosene, toluene (99.5%), and xylene (98.5%)—all in a graduated cylinder. The mixtures were allowed to stand for 24 h without stirring, after which the swelling volume of the clay or organoclay was recorded. The systems were then gently stirred to homogenize the dispersions, and the final swelling volume was measured again after an additional 24 h of rest.

2.1.4. Adsorption Capacity Test (ASTM F726-17)

The oil adsorption capacity of the clays and organoclays was determined following the Standard Test Method for Sorbent Performance of Adsorbents for Use on Crude Oil and Related Spills, F726-17 [

36]. This procedure evaluates the mass of liquid adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent and was performed using gasoline, diesel, and kerosene as representative organic solvents. These fuels were selected because they are commercially available and commonly involved in petroleum spill scenarios in terrestrial and aquatic environments; therefore, toluene and xylene were excluded from this test.

Approximately 1.0 g of clay or organoclay was placed in a #200 stainless steel sieve basket, which was then submerged in the respective organic solvent for 15 min. The basket was removed, drained for a few seconds to remove excess solvent, and weighed. The adsorption capacity (A) was calculated as the ratio between the mass of the solvent retained and the initial mass of the dry adsorbent, as shown in Equation (2):

where

and

correspond to the initial (dry) and final (wet) weights of the sample, respectively.

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The adsorption capacity and swelling index values were calculated from the average of three independent measurements to ensure reproducibility.

2.1.5. PROMETHEE Method

The Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluation (PROMETHEE) is a nonparametric multicriteria decision-making (MCDM) method used to rank alternatives based on multiple performance criteria. In this study, the PROMETHEE method was employed to evaluate and rank the organoclays based on their swelling capacity and adsorption performance in various organic solvents.

The analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel, where the PROMETHEE calculations were implemented manually according to the method’s mathematical formulation. The model parameters include the preference function, preference direction, and criterion weights. The parameters used in this study are summarized in

Table 5.

A V-shaped preference function was selected, transforming the difference in performance between two alternatives into a degree of preference. This linear function assumes that larger performance differences correspond to stronger preferences. Both swelling and adsorption capacity were treated as maximization criteria, with higher values indicating better performance. Equal weights were assigned to both criteria, giving identical importance to swelling and adsorption capacities across all solvents.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Particle Size Distribution and Surface Area

As noted in the

Section 2, both clays have a similar interlayer distance of 1.24 nm, while their surface areas differ by more than 65%. This is expected, since N

2 adsorption surface area analysis only measures the external basal and edge surfaces, not the interlayer space. However, the equipment does not give an error associated with the measurements; the experimental conditions, as well as the sample mass and preparation, will affect the results [

43]. Another critical point is that smectites have a large specific surface area, ranging from 10 to 700 m

2/g [

40], which is related to their texture, stacking, greater platelet separation, additional exposed edge surfaces, or smaller particle-size fractions [

40,

43].

Figure 1 displays the particle size distribution curves of the pristine clays, along with their specific surface areas and characteristic diameters (d

0.1, d

0.5, d

0.9). Both clays exhibited monomodal distributions, with CL showing a broader curve and larger mean size, consistent with greater particle aggregation. The d

0.5 values were 18.2 µm for CL and 6.4 µm for VL, while the d

0.1–d

0.9 range was significantly narrower for VL, suggesting a more homogeneous dispersion. The smaller particle size and higher surface area of VL (

Table 2) may arise from its heterogeneous mineral composition, which favors weaker aggregation and greater mechanical disintegration during dispersion.

3.2. FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy is one of the most important techniques for identifying the key chemical characteristics of clays and organoclays. Based on spectral bands, information on the chemical composition and type of clays, as well as their interactions with other components, such as organic salts, can be investigated.

Figure 2 presents the FTIR spectra of the pristine clays (CL and VL) and their corresponding organoclays. Both clays exhibit similar spectral profiles, consistent with their classification as trioctahedral smectites predominantly containing Na

+ as the exchangeable cation.

A distinct absorption band observed near 3625 cm

−1 for both pristine and modified clays corresponds to the stretching vibration of structural Fe–OH–Fe groups [

24]. The broad band around 3410 cm

−1 is assigned to the O–H stretching vibration of interlayer water molecules [

24]. This band markedly decreases or disappears after organophilization, indicating that the incorporation of organic cations reduced the hydrophilicity of the clays and displaced water from the interlayer region [

44]. Similarly, the band near 1635 cm

−1, associated with the bending vibration of interlayer water (H–O–H) [

10,

24], also decreases in intensity, confirming the partial dehydration induced by surfactant intercalation. A slight shift in the Si–O stretching band toward lower wavenumbers in the organoclays suggests a modification of the local environment of the silicate layers, consistent with cation exchange and intercalation of organic moieties between the lamellae [

45].

In contrast to CL, VL exhibits a band near 840 cm

−1, which can be associated with calcite [

46]. The characteristic sharp OH-stretching peak of kaolinite at ~3690 cm

−1 [

42] is not observed, suggesting that kaolinite is present only in trace amounts, below the FTIR detection limit. Moreover, many vibrational modes of kaolinite, quartz, calcite, and smectite overlap extensively in the 1200–400 cm

−1 region [

46], which limits FTIR’s ability to unambiguously identify minor accessory phases. For this reason, FTIR is commonly used in combination with complementary techniques, such as XRD, to provide a more reliable mineralogical characterization of clay samples.

The intensity of CH

2 stretching vibrations increased with the alkyl chain length of the surfactant, indicating higher organic loading and greater interlayer hydrophobicity. The presence of strong CH

2 stretching bands corroborates the successful incorporation of the surfactant molecules [

44], later confirmed by the mass loss in the 200–400 °C range observed in the TGA.

New absorption bands appear in the spectra of the organoclays around 722 cm

−1 (vibration of deformation out of the plane of the CH

2 group), 1470–1464 cm

−1 (CH

2 scissoring vibrations and indicator of C-N presence), 2843 cm

−1 (symmetric CH

2 stretching), and 2930 cm

−1 (asymmetric CH stretching) [

10,

24,

28,

44], which confirms the presence of alkyl chains from the quaternary ammonium salts.

The characteristic smectite bands at 996, 1002, 1112, 1117, and 3637 cm

−1 remain unchanged after modification, corresponding to the Si–O stretching, Al

2OH deformation, and Fe–OH–Fe stretching vibrations, respectively [

24,

28]. These persistent structural bands indicate that the clay layers retained their silicate framework following organophilization. The relative intensities of the CH

2 stretching bands vary slightly among the organoclays, reflecting differences in the alkyl chain length and packing density of the intercalated surfactants.

3.3. XRD Analysis

XRD analysis is one of the most important methods for characterizing both pristine clays and organoclays. It is used to determine the presence of clay minerals and to identify interlayer displacement after the incorporation of organocations into clays. The first peak in the diffractogram pattern is referred to as the basal peak (001), and it is used to calculate the interlayer distance using Bragg’s law [

44].

Figure 3 presents the XRD patterns of the pristine and organophilic clays. This technique provides information about the crystalline structure and mineral composition of pristine clays, enabling the identification of structural modifications following surfactant intercalation. Both clays (CL and VL) exhibited the characteristic basal reflection of sodium montmorillonite at 2θ ≈ 7°, corresponding to an interlayer spacing (d

001) of approximately 1.24 nm, as calculated by Bragg’s law [

12,

24,

25]. The main difference between the two pristine samples lies in the presence of accessory minerals in VL, including kaolinite, quartz, and calcite, while CL consists almost exclusively of montmorillonite, as previously reported by our group [

38]. These peaks were validated by identification as described in

Table 1 and by ICDD code identification, and were observed by other groups’ studies as well [

47,

48]. The additional reflection at 2θ ≈ 12°, corresponding to a d-spacing of 0.75 nm, is attributed to kaolinite [

49,

50,

51]. This peak disappeared after organophilization, suggesting partial delamination of kaolinite induced by surfactant insertion and mechanical stirring [

52].

After modification, both clays showed a shift in the (001) reflection toward lower diffraction angles (2θ ≈ 3–4°), indicating an increase in interlayer spacing due to the intercalation of quaternary ammonium salts between the clay lamellae [

24]. The extent of this shift depended on both the type of clay and the surfactant. For example, Sun-modified clays exhibited basal spacings of 1.75 nm (CL) and 1.81 nm (VL), consistent with a bilayer arrangement of surfactant molecules within the galleries [

4]. In contrast, Arq modification produced interlayer distances of 1.90 nm (CL) and 2.12 nm (VL), suggesting a transition toward a pseudo-trimolecular configuration, while Arm yielded spacings of 2.40 nm (CL) and 2.56 nm (VL), characteristic of a trimolecular or pseudo-paraffinic arrangement [

4,

11,

17,

24,

37,

53,

54].

In addition to the (001) reflection, a downshift in the (110) plane from 2θ ≈ 29° to ≈24° was observed for CL, corresponding to an increase in the lattice spacing from 0.31 nm to approximately 0.37 nm, further supporting the structural expansion caused by surfactant intercalation [

44]. Other studies have also shown that the exfoliation of kaolinite is caused by the intercalation of n-alkylamines [

40]. The persistence of quartz and calcite peaks in VL after modification indicates that these phases remained inert during organophilization, as expected for non-swelling minerals. The larger interlayer spacing and partial delamination observed in VL-based organoclays suggest greater accessibility of organic molecules to the interlayer regions, which likely enhances their adsorption performance compared to CL.

The corresponding basal spacings (d

001) for each clay–surfactant system are summarized in

Table 6. Two main trends were identified: (i) the interlayer distance increased with the molar mass of the surfactant, and (ii) VL consistently exhibited larger interlayer expansions than CL. The latter can be attributed to VL’s higher specific surface area, which facilitates greater surfactant accessibility and intercalation efficiency [

5]. The interlayer spacings of 1.7–1.9 nm correspond to bilayer configurations, while spacings above 2.2 nm indicate pseudo-trimolecular or paraffinic arrangements, consistent with the alkyl chain lengths of the surfactants used [

4].

3.4. Thermal Analysis (TGA and DTA)

Figure 4 shows the thermogravimetric (TGA and DTG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) curves of the pristine and organophilic clays. The thermal decomposition of clays generally occurs in three main mass-loss stages, which are clearly observed for the pristine samples. The first stage (up to 200 °C) corresponds to the loss of physically adsorbed surface water. The second stage (200–575 °C) involves the removal of interlayer water molecules, while the third stage (575–800 °C) involves dehydroxylation of structural hydroxyl groups. Beyond 800 °C, no significant mass loss was detected, confirming the completion of dehydroxylation. Among these stages, the second exhibited the lowest mass loss, consistent with the limited amount of interlayer water in sodium bentonites [

24].

Both clays exhibited similar thermodegradation profiles, which is expected for smectite-rich materials. Although VL contains accessory phases such as kaolinite, calcite, and quartz, their contribution to the TGA curves is minimal. Quartz is thermally stable and does not undergo mass loss under standard TGA conditions, as it contains no volatile species. Kaolinite and calcite, in turn, decompose within temperature ranges that partially overlap with the broad dehydroxylation and structural water-loss events of smectite [

47,

48]. As a result, the mass-loss steps associated with these accessory minerals are not clearly distinguishable or quantifiable in the thermal analysis, and the overall thermogravimetric behaviour is dominated by the smectite fraction.

The organoclays displayed similar profiles but showed distinct thermal behaviours depending on the surfactant type. In agreement with the FTIR results, all organoclays exhibited a marked reduction in surface water loss, decreasing from 1.4% in the pristine clays to 0.2% in the modified samples. This reduction reflects the decreased hydrophilicity of the clays and the partial replacement of interlayer water by organic cations. Minor variations in this region may be attributed to volatile components in the surfactants and their interactions with the clay layers. Overall, the total mass loss of organoclays increased by 6–7% compared to their pristine counterparts, confirming the incorporation of organic matter.

In the 200–700 °C range, the decomposition of the intercalated surfactant overlapped with the dehydroxylation process, producing broad and complex mass-loss regions [

29,

37]. The magnitude of this loss depended on the type of organic salt: organoclays with larger interlayer spacings (particularly those modified with Arm) exhibited greater overall mass loss, consistent with higher surfactant content and the stronger C–H stretching bands observed in the FTIR spectra.

The DTG curves (

Figure 4) further clarify these thermal events. Surfactant decomposition occurred primarily around 300 °C, where the maximum mass-loss rate was observed. For CL, the dehydroxylation peak shifted from 650 °C to 580 °C and became broader, reflecting the overlap of structural dehydroxylation and organic salt degradation. The VL organoclays displayed two partially resolved peaks at 580 °C and 700 °C, attributed to the same overlapping phenomena.

The DTA curves (

Figure 4) corroborate the TGA findings. The pristine clays exhibited two endothermic peaks at 100–200 °C and around 650 °C, corresponding to the removal of surface water and dehydroxylation, respectively. In contrast, these peaks disappeared in the organoclays due to their reduced hydrophilicity and the dominance of overlapping decomposition processes. Instead, two exothermic peaks appeared at approximately 350 °C and 650 °C, corresponding to two stages of surfactant oxidation: the first associated with the external organic chains and the second with the chains intercalated within the interlayer galleries.

Figure 4 shows the TGA curves of both pristine clays and organophilic clays. In general, the TGA curves of clays show three major weight-loss steps, as seen in the Pristine clays, which exhibit similar curves. The first step involved surface water loss (up to 200 °C), followed by the loss of interlayer water molecules (up to 575 °C), and finally, dehydroxylation, after which no weight loss is observed in the samples up to 800 °C. As shown, the second step resulted in the lowest weight loss compared to surficial water and dehydroxylation.

The organoclays’ curves showed similar profiles, reflecting the organic salt with which they were modified. Following the FTIR results, which showed a reduction in surficial water after organophilization, all organoclays exhibited a significant reduction in surficial water loss, varying from 1.4% to 0.2%. The variance in weight loss may be related to the volatiles present in the salt compositions and their interactions with the clay. This resulted in a 6–7% reduction in clay weight compared to its respective pristine clay. The organoclays’ second and third stages are mixed due to the overlapping of salt decomposition and the dehydroxylation processes (from 200 to 700 °C) [

9,

37]. During these stages, organoclays exhibited greater weight loss than pristine clays due to the presence of organic cations. Following the XRD results, organoclays with the highest interlayer distance, prepared using Arm salt, exhibited the highest weight loss, as well as the highest intensity of the C-H bond bands in the FTIR spectra.

The detailed mass-loss values and corresponding temperature ranges for each decomposition stage are summarized in

Table 7. For consistency, the same temperature intervals were applied to all samples: (1) 50–200 °C for surface water removal, (2) 200–575 °C for interlayer water release and surfactant decomposition, and (3) 575–800 °C for dehydroxylation and residual organic degradation. In the first stage (50–200 °C), the mass loss decreased from approximately 7% in the pristine clays to 0.2–1.4% in the organoclays. This marked reduction confirms the decreased hydrophilicity following surfactant intercalation, as observed in the FTIR spectra. Minor differences among the organoclays may arise from residual volatiles or solvents associated with the surfactants. In the second stage (200–575 °C), the trend was reversed: the organoclays exhibited significantly higher mass losses (19–28%), whereas the pristine clays showed only about 1.5%. This region corresponds to the combined thermal decomposition of the intercalated surfactant molecules and the release of remaining interlayer water.

During the third stage (575–800 °C), both pristine clays underwent dehydroxylation, resulting in mass losses of 3.1% (CL) and 2.5% (VL). The corresponding organoclays exhibited higher losses (around 7%), attributed to the concurrent dehydroxylation and oxidation of residual organic species.

The amount of incorporated surfactant was estimated by summing the mass losses in stages 2 and 3 for each organoclay and subtracting the intrinsic dehydroxylation loss of the corresponding pristine clay [

24,

55]. The results reveal a consistent trend across both clays: VL incorporated more surfactant than CL, and the amount incorporated increased with the surfactant’s molar mass. Specifically, the total mass gain relative to pristine clay was approximately 6% for Sun-modified samples and up to 11% for Arq-modified ones. These findings align with the XRD results, which also showed a proportional increase in interlayer spacing with surfactant chain length and molar mass.

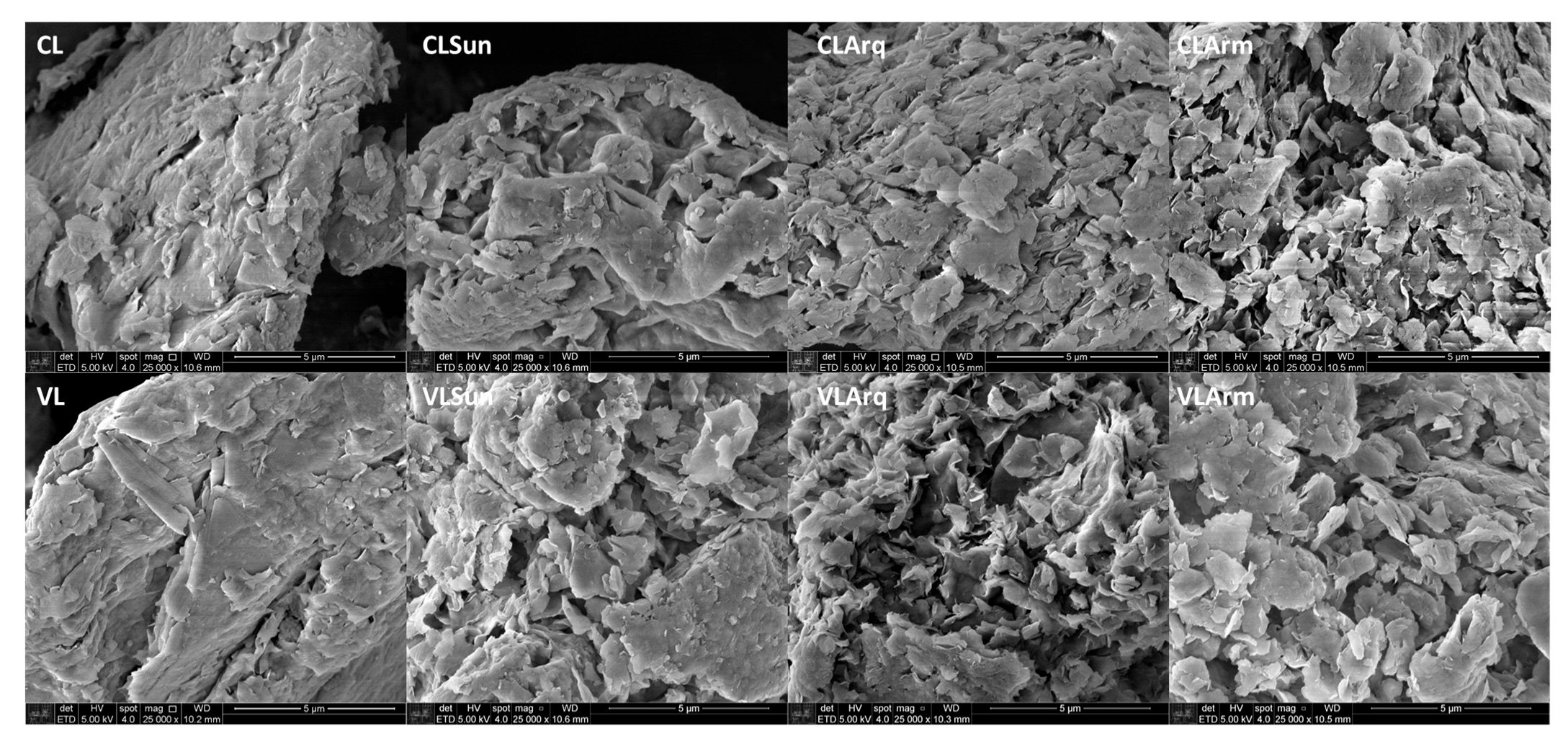

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Figure 5 shows the surface morphology of the pristine and organophilic clays. Both pristine clays (CL and VL) exhibit the typical montmorillonite morphology, characterized by stacked lamellar structures forming tactoids and aggregates [

24]. Smectitic particles are composed of thin platelets that overlap to form tactoids, which in turn assemble into larger agglomerates [

56]. In the pristine clays, the surfaces appear relatively compact, with closely packed aggregates and few visible pores, suggesting limited exfoliation.

After organophilization, a clear decompaction of the aggregates was observed, consistent with reports in the literature [

44]. The lamellar structures became more distinguishable, and interparticle porosity increased, indicating partial separation of the clay platelets. The morphological transformation was more pronounced for clays modified with Sun, Arq, and Arm surfactants, in that order, producing increasingly “cornflake-like” structures and a flaky, open-textured surface. Similar results were also found in the literature [

44].

This morphological evolution is consistent with the XRD results, which showed an increase in the interlayer spacing after surfactant intercalation. The expanded and more porous structures likely facilitate the diffusion and adsorption of organic molecules, correlating with the improved oil sorption capacity discussed later (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

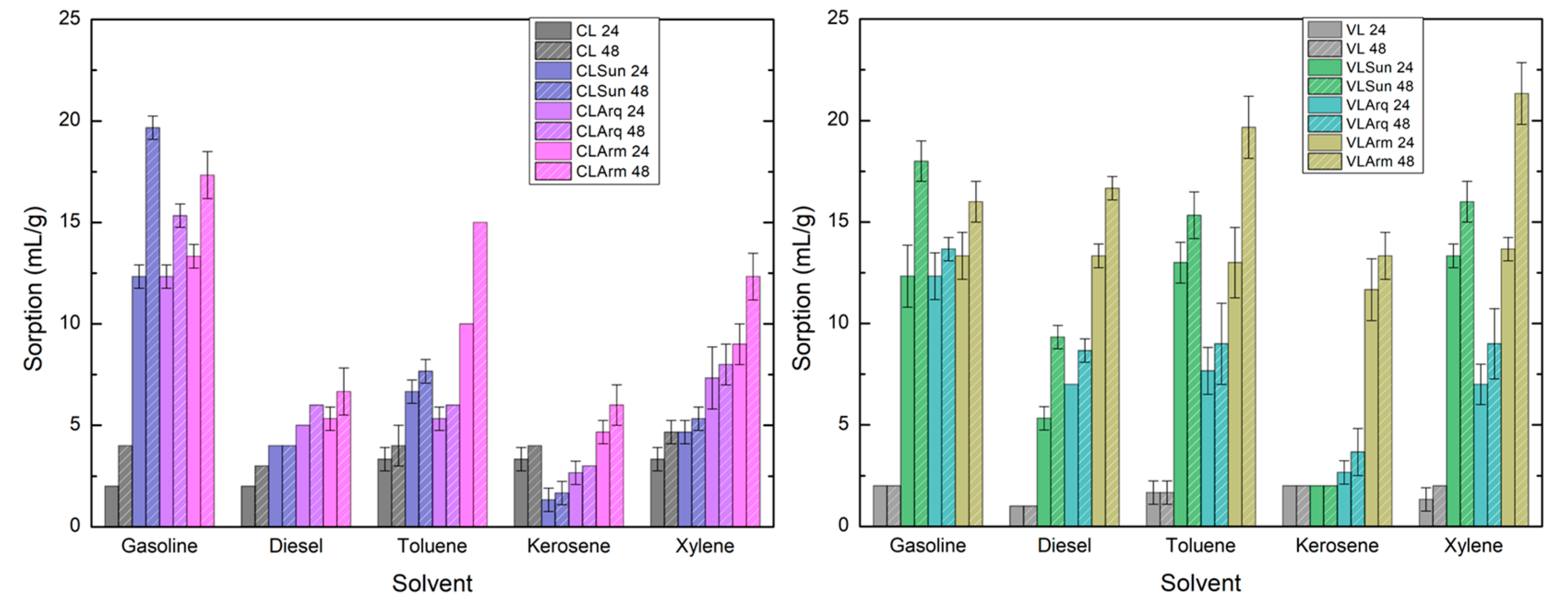

3.6. Swelling Test (ASTM D5890)

Figure 6 presents the swelling volumes of the pristine and organophilic clays in various organic solvents. Among the pristine clays, CL exhibited higher swelling volumes than VL in all solvents, both before and after stirring. This behavior can be attributed to the fact that CL is composed almost exclusively of montmorillonite, whereas VL contains accessory minerals such as kaolinite, quartz, and calcite, which reduce its swelling ability.

After organophilization, this trend reversed. The VL organoclays exhibited greater swelling capacities than their CL counterparts across all tested solvents. This improvement is likely related to VL’s larger specific surface area, which enhances interaction with surfactant molecules and facilitates better intercalation.

The type of organic salt strongly influenced the swelling behavior of both clays. In general, the organoclays modified with Arm—the surfactant of highest molar mass—showed the greatest swelling capacities, exceeding 13 mL/g in all solvents after stirring. This result aligns with the findings of TGA and XRD, which indicate that Arm-modified clays exhibit the highest surfactant content and the largest interlayer spacings. The increased interlayer distance and the enhanced lipophilic character of the organoclays promoted stronger interactions with the organic solvents, resulting in higher swelling volumes.

Swelling capacity also increased after stirring and prolonged contact (48 h), indicating a time-dependent equilibrium between solvent diffusion and interlayer expansion. The values obtained here were higher than those reported in similar studies [

28,

29,

57], confirming the efficiency of the modification process and the strong affinity of these organoclays toward nonpolar solvents.

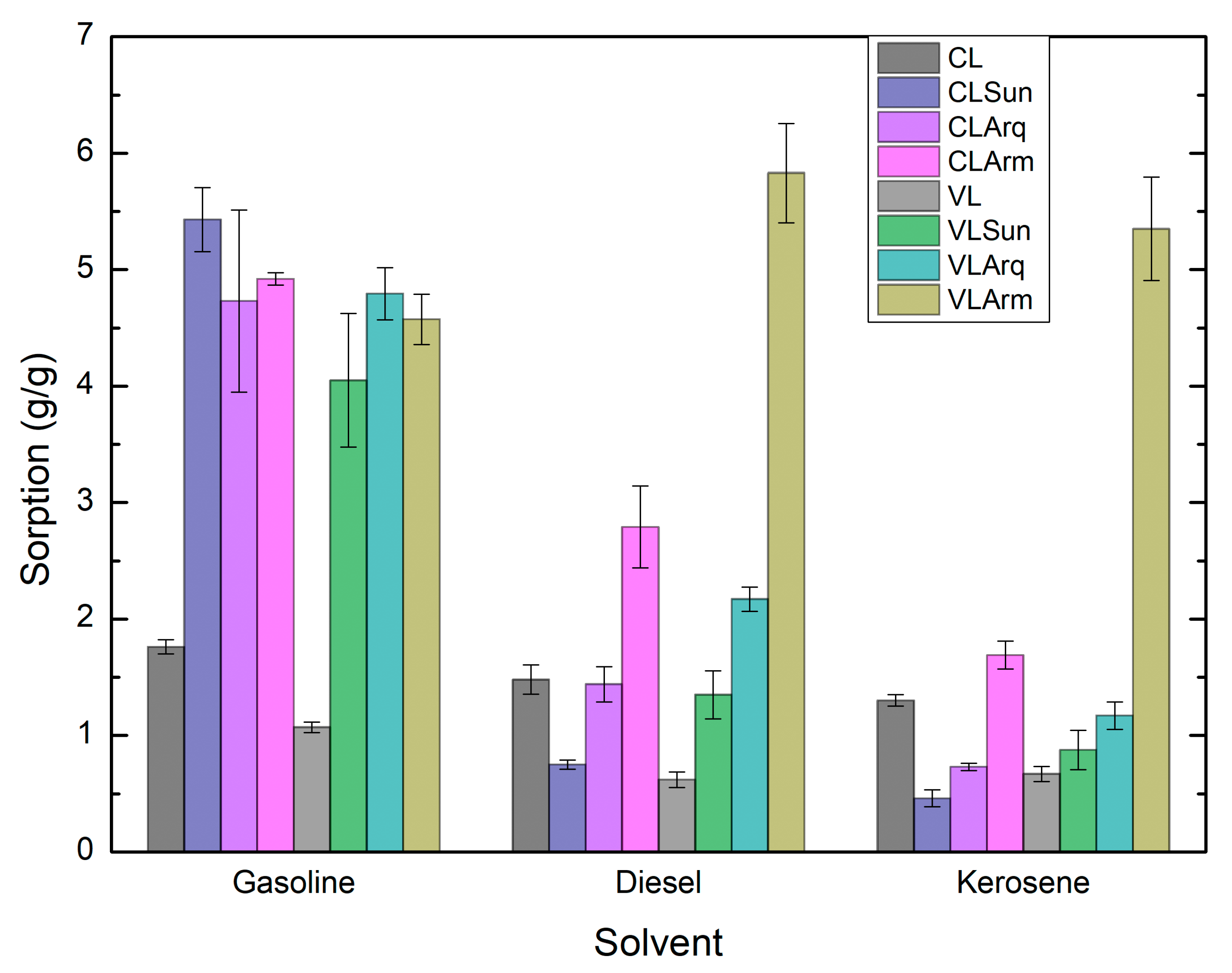

3.7. Adsorption Capacity Test (ASTM F726-17)

Figure 7 presents the oil adsorption capacities of the pristine clays and organoclays. According to the Forster test (ASTM D5890-19 [

35]), the Arm-modified organoclays exhibited the highest swelling index, which was also observed in the adsorption capacities among all samples (ASTM F726-17 [

36]). For diesel, kerosene, and gasoline, their sorption values ranged from 4.6 to 6.0 g/g, indicating that these materials can adsorb up to six times their own weight in oil. Only one study in the literature has reported a higher value for diesel adsorption (7 g/g).

The adsorption performance was not uniform across all solvents; however, VLArm consistently showed high capacities in every medium, suggesting it is the most effective sorbent. This superior performance is attributed to VL’s larger surface area and higher surfactant loading, which enhance the material’s hydrophobicity and promote stronger interactions with nonpolar solvents.

The adsorption capacities obtained in this study are notably higher than those reported for most other organoclays and related adsorbents. For instance, previously reported organoclays incorporating p-nitrophenol adsorbed only around 50 mg/g, nearly three orders of magnitude lower than the present results. Although p-nitrophenol differs chemically from the petroleum-based compounds tested here, this comparison underscores the remarkable oil-uptake potential of the VLArm system, especially for applications involving BTEX compounds [

12].

Furthermore, VLArm exhibited toluene adsorption capacities surpassing those of activated carbon, organophilized zeolites, montmorillonite, and sericite. Interestingly, another study reported montmorillonite samples with interlayer spacings > 3 nm that still displayed lower adsorption capacities than those observed here, suggesting that interlayer expansion alone is not the dominant factor governing adsorption efficiency [

58].

Overall, the results demonstrate that the Arm-modified VL organoclay outperforms many conventional and modified adsorbents reported in the literature [

27,

59]. Its combination of enhanced surface area, optimal interlayer structure, and balanced hydrophobicity makes it a promising material for environmental remediation and oil spill recovery applications.

3.8. Multi-Criteria Analysis (PROMETHEE Ranking)

Based on the PROMETHEE ranking results presented in

Table 8. The VLArm sample was identified as the most effective organoclay for sorbing organic solvents. This ranking was derived from the combined evaluation of swelling capacity, adsorption capacity, and their aggregated performance across all solvents. These results clearly highlight VLArm’s superior efficiency and its potential for practical applications in oil and solvent remediation.

The comparison between swelling and adsorption capacities revealed that a high swelling volume does not necessarily correspond to enhanced sorption performance. For instance, VLSun exhibited the second-highest swelling capacity overall but ranked lowest in adsorption capacity, indicating that excessive expansion does not guarantee greater solvent uptake. This distinction emphasizes the importance of considering multiple performance parameters simultaneously when assessing sorbent materials.

When the adsorption capacity criterion was analyzed independently, the type of surfactant exerted a greater influence on performance than the nature of the pristine clay. Among the modifiers studied, Arm was the most effective, while Sun was the least efficient. Notably, VLArm exhibited a preference index nearly three times higher than the next-best organoclay, underscoring its outstanding overall performance.

These findings are consistent with the FTIR, XRD, and TGA results, which collectively indicate that VLArm contains the highest surfactant loading, the largest interlayer expansion, and enhanced hydrophobicity. Together, these structural and compositional features account for its superior behavior in both swelling and solvent adsorption, confirming VLArm’s suitability as a highly efficient sorbent for organic solvent removal. The positive and negative preference flows (Φ+ and Φ−) confirmed VLArm’s dominance, with a net flow (Φ) significantly higher than that of all other samples.

4. Conclusions

In this study, two sodium bentonites, Cloisite Na+ (CL) and a natural Argentinian clay (VL), with specific surface areas of 30 and 50 m2/g, respectively, were selected to evaluate their potential as sorbents for organic solvents. Both clays were modified with three quaternary ammonium salts of increasing molar mass, designated Sun, Arq, and Arm.

The FTIR spectra confirmed successful organophilization. XRD analysis revealed an increase in the basal spacing (d001), confirming the intercalation of the organic cations into the smectite layers. SEM images revealed that organophilization led to the decompaction of aggregates, increased porosity, and partial exfoliation of lamellae. These morphological and structural changes account for the higher solvent uptake observed in the organoclays compared to the pristine clays. The swelling and adsorption experiments demonstrated that both the clay type and the surfactant strongly influenced performance. The VL samples generally showed higher sorption capacities than CL, attributed to their larger surface area and greater surfactant incorporation, as confirmed by TGA. Among the surfactants, Arm, with the highest molar mass and longest alkyl chain, produced the most effective organoclays, combining large interlayer expansion with improved solvent affinity. The VLArm sample exhibited adsorption capacities exceeding 5 g/g for all organic solvents tested, highlighting its broad efficiency, structural stability, and low cost. The exceptionally high adsorption capacities achieved, which significantly surpass most values reported in the literature, confirm that VLArm is a promising, sustainable material for environmental remediation, particularly for the removal of hydrocarbon pollutants and oil spill recovery.

Future work will focus on optimizing surfactant loading, evaluating reusability under dynamic conditions, and expanding the study to other classes of organic contaminants to further assess the versatility and environmental applicability of these organoclays.