Abstract

A new mineral species of the mica group, fluorluanshiweiite, ideally KLiAl1.5□0.5(Si3.5Al0.5)O10F2, has been found in the Nanyangshan LCT (Li, Cs, Ta) pegmatite deposit in North Qinling Orogen (NQO), central China. Fluorluanshiweiite can be regarded as the F-dominant analogue at the A site of luanshiweiite or the K-dominant analogue at the I site of voloshinite. It appears mostly in cookeite as a flaky residue, replaced by Cs-rich mica, or in the form of scale aggregates. Most individual grains are <1 mm in size, with the largest being ca. 1 cm, and the periphery is replaced by cookeite. No twinning is observed. The mineral is silvery white as a hand specimen, and in a thin section, it appears grayish-white to colorless, transparent with white streaks, with vitreous luster and pearliness on cleavage faces. It is flexible with micaceous fracture; the Mohs hardness is approximately 3; the cleavage is perfect on {001}; and no parting is observed. The measured and calculated densities are 2.94(3) and 2.898 g/cm3, respectively. Optically, fluorluanshiweiite is biaxial (–), with α = 1.554(1), β = 1.581(1), γ = 1.583(1) (white light), 2V(meas.) = 25° to 35°, 2V(calc.) = 30.05°. The calculated compatibility index based on the empirical formula is −0.014 (superior). An electron microprobe analysis yields the empirical formula calculated based on 10 O atoms and 2 additional anions of (K0.85Rb0.12Cs0.02Na0.03)Σ1.02[Li1.05Al1.44(□0.47Fe0.01Mn0.02)Σ0.5] Σ2.99(Si3.55Al0.45) Σ4O10F2, which can be simplified to KLiAl1.5□0.5(Si3.5Al0.5)O10F2. Fluorluanshiweiite is monoclinic with the space group C2/m and unit cell parameters a = 5.2030(5), b = 8.9894(6), c = 10.1253(9) Å, β = 100.68(1)°, and V = 465.37(7) Å3. The strongest eight lines in the X-ray diffraction data are [d in Å(I)(hkl)]: 8.427(25) (001), 4.519(57) (020), 4.121(25) (021), 3.628(61) (112), 3.350(60) (022), 3.091(46) (112), 2.586(100) (130), and 1.506(45) (312).

1. Introduction

A new mineral species of the mica group, KLiAl1.5□0.5(Si3.5Al0.5)O10F2, has been found in the Nanyangshan LCT pegmatite deposit in North Qinling Orogen (NQO), Central China (33°52′58″ N, 110°43′55″ E). It is named fluorluanshiweiite based on its relationship to luanshiweiite. It is characterized as F-dominant at the A site of luanshiweiite [1] or K-dominant at the I site of voloshinite [2]. The new mineral (IMA2019-053) has been approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association (IMA-CNMNC) [3]. The material was deposited in the mineralogical collection of the Geological Museum of China, No. 16, Xisi Yangrou Hutong, Xicheng District, Beijing 100034, People’s Republic of China (catalogue number: M16085). This paper describes the physical, chemical, and spectroscopic data of fluorluanshiweiite and its crystal structure.

2. Occurrence and Physical Properties

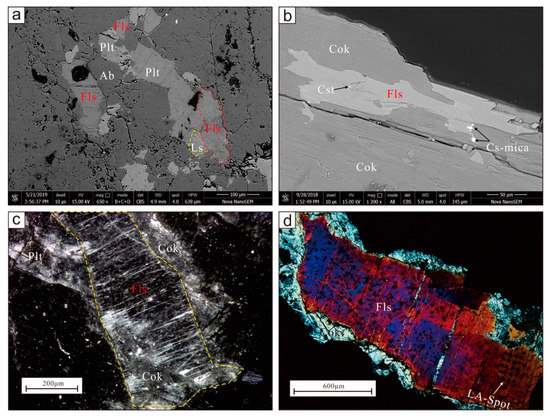

The Nanyangshan rare metal deposit is located in NQO, Western Henan Province, central China. The rare metal mineralization is hosted in granitic pegmatite [4]. According to the classification and revision by Černý [5] and Černý and Ercit [6], it is classified as LCT pegmatite. The Ar-Ar dating of muscovite revealed that the Nanyangshan pegmatite formed at 396–410 Ma [7], and the age coincides with the time of U-REE-rare metal mineralization (mean = 408 Ma) in NQO [8,9,10], shortly after 400–428 Ma (mean = 417 Ma), when the related intrusions formed, indicating that the mineral formed in the late stage of the evolution of a pegmatite-forming magmatic liquid. The new mineral is closely associated with luanshiweiite (first recorded locality [1]), polylithionite, cookeite, albite, quartz and an unknown Cs-rich mica (Figure 1a,b), and it is commonly found with spodumene, montebrasite, elbaite, fluorapatite, pollucite, and nanpingite. Tantalite-(Mn), columbite-(Mn), bismutotantalite, stibiotantalite, oxynatromicrolite (first recorded locality [11]), and fluornatromicrolite are some other associated minerals.

Figure 1.

(a) and (b) Backscattered electron images of mineral aggregates; (c) fluorluanshiweiite under binocular microscope; (d) grains for single-crystal X-ray analysis under cross-polarized light. Fls, fluorluanshiweiite; Ls, luanshiweiite; Plt, polylithionite; Cok, cookeite; Cst, cassiterite; Ab, Albite.

Fluorluanshiweiite occurs mostly in cookeite as a flaky residue, replaced by Cs-rich mica, or in the form of scale aggregates. Most individual grains are <1 mm in size, with the largest being ca. 1 cm, and the periphery is replaced by cookeite (Figure 1c,d). The mineral is silvery white as a hand specimen and grayish-white to colorless in a thin section, transparent with white streaks. In addition, it has vitreous luster and appears pearly on cleavage planes. It is flexible with micaceous fracture, the Mohs hardness is approximately 3, the cleavage is perfect on {001}, and no parting was observed. The measured and calculated densities are 2.94(3) and 2.898 g/cm3, respectively. Optically, fluorluanshiweiite is biaxial (–) with α = 1.554(1), β = 1.581(1), γ = 1.583(1) (white light), 2V (meas.) = 25° to 35°, 2V (calc.) = 30.05°. The calculated compatibility (1-KP/KC) is superior (−0.014) [12].

3. Chemical Composition

The chemical compositions of the fluorluanshiweiite and associated luanshiweiite and polylithionite were determined at the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology with a JXA-8100 electron microprobe at 15 kV and 10 nA with a beam diameter of 10 μm. The FKα was determined with an LDE1 crystal (JEOL, 2d ≈ 6 nm), which is suitable for the analysis of 6C–10Ne, and the P/B ratio is much higher than that of the TAP crystal for F. The standards include phlogopite for K, Fe and Al; pollucite for Rb and Cs; albite for Na; tantalite-(Mn) for Mn; sanidine for Si and fluorapatite for F. The fluorine migration and peak overlap have been fully considered in the factors affecting the accurate quantification of F in the EPMA process to ensure that the results are reliable. The lithium content analysis was carried out using an LA-MC-ICP-MS instrument (Neptune, Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a (ESI) NewWare 193 FX ArF Excimer laser ablation system with a 193-nm wavelength. The operating conditions were as follows: beam diameter = 30 μm, alongside a laser pulse rate of 8 Hz with an energy density of approximately 4 J/cm2; N = 20. The obtained results were consistent with the data (3.95% Li2O) determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). Scanning electron microscopy investigations were performed with an FEI Nova Nano scanning electron microscope (SEM) (10 μs; 15 kV). The anhydrous nature of the studied mineral was indicated by the absence of OH stretching vibration absorption in the ATR-FT/IR spectrum, as shown below.

Twenty electron microprobe point analyses for fluorluanshiweiite yielded an average composition (wt. %) of K2O 9.87, Rb2O 2.86, Cs2O 0.86, Na2O 0.26, FeO 0.26, MnO 0.43, Al2O3 23.65, SiO2 52.42, and F 9.35. The Li2O content analyses yielded an average composition of 3.85 wt % by LA-MC-ICP-MS, resulting in a total of 99.87. The empirical chemical formula calculated on the basis of 10 O2− and 2 F− apfu. is (K0.85Rb0.12Cs0.02Na0.03) Σ1.02[Li1.05Al1.44(□0.47Fe0.01Mn0.02)Σ0.5]Σ2.99(Si3.55Al0.45)Σ4O10F2. The ideal formula is K(LiAl1.5□0.5)(Si3.5Al0.5)O10F2, which requires K2O 11.88, Li2O 3.77, Al2O3 25.73, SiO2 53.07, F 9.59, O≡F −4.04, total 100 wt. %. Compared to polylithionite in the Nanyangshan LCT deposit, fluorluanshiweiite contains more Rb, less Si and more Al. The high fluorine content is a key feature that distinguishes fluorluanshiweiite from luanshiweiite (Table 1).

Table 1.

Chemical composition (wt. %) of fluorluanshiweiite and other lepidolite species in nanyangshan LCT deposit.

4. Spectroscopic Features

Spectroscopic analyses were performed at the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology. Infrared spectroscopic data of fluorluanshiweiite were obtained using a Bruker LUMOS spectrometer with an ATR model in the range 600–4000 cm−1. Raman spectra were recorded on a LabRAM HR Raman microscope with a laser excitation wavelength of 532 nm. The power of the excitation radiation was 20 mW, and the lateral resolution was estimated to be 1 μm. The results were acquired in the range 100–2000 cm−1.

4.1. Infrared Spectroscopy

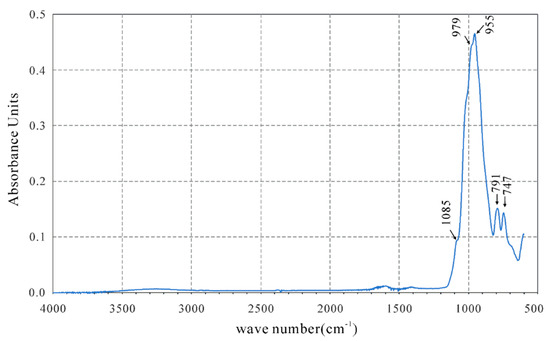

The vibrations of mica group minerals can be roughly separated into the vibrational region of hydroxyl groups and the lattice vibrational region, including the vibrations of Si(Al)O4 tetrahedra and octahedrally coordinated cations [13]. In the IR spectrum of fluorluanshiweiite (Figure 2), the bands at 747 and 791 cm−1 are due to the Al–O fundamental modes, and the bands at 955, 979, and 1085 cm−1 are due to the Si–O fundamental modes, resembling the spectrum of luanshiweiite (760, 798, 891, 988, and 1115 cm−1) [1] and similar to the infrared spectral reference cards (Sil59, Sil60) of the lepidolite series [14].

Figure 2.

Infrared spectra of fluorluanshiweiite.

There is no evidence for the high-energy OH stretching vibrations that commonly occur in the region from 3750–3550 cm−1 for mica group minerals. The defining characteristic of the infrared spectrum is the absence of the high-energy hydroxyl stretching vibration absorption band at −3620 cm−1 [1], which is the most significant difference between fluorluanshiweiite and luanshiweiite. The chemical analyses confirm that the A site in the new mineral is fully occupied by F (Table 1).

4.2. Raman Spectroscopy

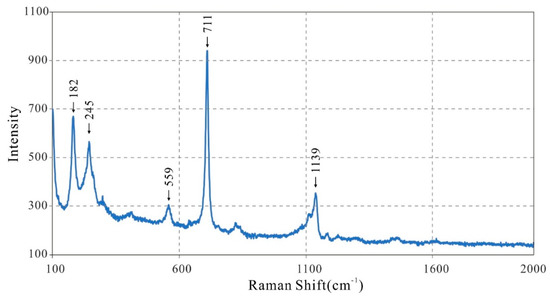

The resulting Raman spectrum of fluorluanshiweiite resembles that of a “Cs-bearing lepidolite” from lepidolite granite, Yichun, China (peaks: 181, 240, 710, and 1141 cm−1) [15], and is similar to the RRUFF Project database spectra of the lepidolite series (X050113, R040101.3, R050132.4). The typical peak for phyllosilicate minerals at ~700 cm−1 is well displayed for fluorluanshiweiite (711 cm−1), corresponding to both Si–O stretching and O–Si–O bending deformations. The peaks at approximately 559 and 1139 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching mode of the Si–O bond in SiO4 tetrahedra [16,17,18].

Raman spectra of mica minerals show several peaks in the low-wavenumber region: ~100, ~160, ~195, ~220, and ~240 cm−1, of which peaks at ~195 and ~240 cm−1 are generally strong in diocatahedral lepidolite [19]. On the basis of the previous results of Loh [20], the peaks at 182 and 245 cm−1 for fluorluanshiweiite may be assigned to the internal vibrations of the MO6 octahedron (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of fluorluanshiweiite.

5. Crystal Structure

Both powder and single-crystal X-ray diffraction data of fluorluanshiweiite were collected on a Rigaku Oxford diffraction XtaLAB PRO-007HF microfocus rotating anode X-ray source (1.2 kW, MoKα, λ = 0.71073 Å) and a hybrid pixel array detector single-crystal diffractometer using MoKα-radiation in the Laboratory of Crystal Structure, China University of Geosciences (Beijing, China).

X-ray powder diffraction data are given in Table 2. The reflection intensities are close to those of the theoretical pattern of lepidolite-1M (database ICDD, card no. 85-911). The strongest eight lines in the X-ray diffraction pattern are [d in Å(I)(hkl)]: 8.427(25) (001), 4.519(57) (020), 4.121(25) (021), 3.628(61) (112), 3.350(60) (022), 3.091(46) (112), 2.586(100) (130), and 1.506(45) (312). The powder X-ray diffraction data are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

X-ray powder diffraction data (d in Å) for fluorluanshiweiite (8 strongest lines are in bold).

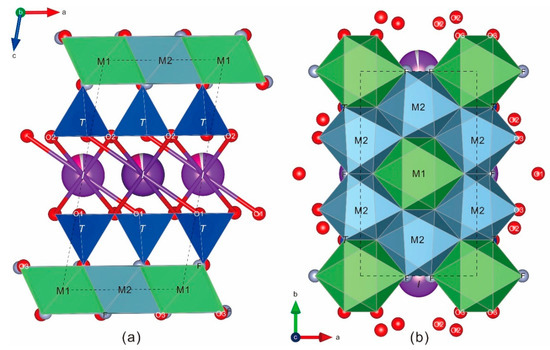

A colorless flake of fluorluanshiweiite was selected for the single-crystal X-ray diffraction data collection. All reflections were indexed on the basis of a monoclinic unit cell. The structure was solved and refined using SHELX Software [21] based on the space group C2/m. Unit-cell parameters were as follows: a = 5.2030(5), b = 8.9894(6), c = 10.1253(9) Å, β = 100.68(1)° and V = 465.37(7) Å3. Anisotropic refinement using all measured independent data and reflections with Fo ≥ 4σ resulted in an R1 factor of 0.091. The relatively large R1 could be due to the crystal quality being imperfect; such values for the R factor are relatively often reported for the lepidolite series. In addition, the high R1 factor of micas may also be affected by the Durovič effect [22]. The crystal structure refinement details for fluorluanshiweiite are reported in Table 3. A view of the structure is presented in Figure 4. Refined coordinates and anisotropic-displacement parameters are presented in Table 4 and Table 5, and selected bond lengths and angles are given in Table 6.

Table 3.

Crystallographic data and refinement results for fluorluanshiweiite.

Figure 4.

The crystal structure of fluorluanshiweiite: (a) view along the b axis and (b) view along the c axis. dark blue: Si tetrahedra(T); green: Li octahedra(M1); blue-gray: Al octahedra(M2); purple: I-site.

Table 4.

Atomic coordinates and isotropic displacement parameters (in Å2) for fluorluanshiweiite.

Table 5.

Anisotropic displacement parameters (in Å2) for fluorluanshiweiite.

Table 6.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for fluorluanshiweiite.

6. Discussion

The structure of fluorluanshiweiite is similar to that of other species of the mica group. The general formula of mica group minerals may be written as IM2–3□1−0T4O10A2 [23]; for fluorluanshiweiite, I is K, M is Li + 1.5Al + 0.5□, T is 3.5Si + 0.5Al, and A is 2F. Regarding the interlayer cation, the difference between the inner (mean 2.970 Å) and outer (mean 3.237 Å) <I–O> distances is similar to that in the luanshiweiite-2M1 structure (2.938 and 3.251 Å, respectively). The mean <M1–O> distance in fluorluanshiweiite is 2.108 Å, including the Li–O distance, 2.112 Å, and the Li-F distance, 2.101 Å. These distances are comparable to the sum of the ionic radii of Li+, O2− and F− (0.76, 1.40 and 1.38 Å, respectively) [24] and are slightly shorter than the luanshiweiite Li–O distance, 2.140 Å. The <M2–O> distance (mean 1.973 Å) is similar to that of luanshiweiite (mean 1.957 Å) and longer than the values given by Shannon and Prewitt [25] for Al–O (1.91 Å). The octahedral distance from the center of a vacant site to the nearest six oxygen atoms should be considered in reference to other mica minerals, e.g., montdorite and yangzhumingite [26,27,28,29]. In this case, the occurrence of 0.5 vacancies at the M2 site in fluorluanshiweiite must be considered. On the basis of the mean □−O distance in reported dioctahedral micas of 2.174 Å [30,31], the ideal <M2−O> distance in fluorluanshiweiite should be 1.976 Å, which is similar to the distance 1.973 Å observed. The mean <T−O> distance (1.626 Å) in fluorluanshiweiite is similar to that in luanshiweiite (mean 1.628 Å), longer than that in polylithionite (1.621 Å) [32] and shorter than that in trilithionite (1.638 Å) [33,34] due to substitution of smaller Si4+ and larger Al3+ in the tetrahedral layer, which is consistent with the occupancy of Si and Al at the T site in the lepidolite species above. Octahedral vacancies can be introduced by a substitution mechanism such as Li+ + 0.5Si4+ ↔ Al3+ + 0.5□.

Bond-valence analysis (BVS): The bond valence (vu) was calculated from the interatomic distance following the procedure of Brown and Altermatt [35]. The bond-valence sums for the I(K), M1(Li), M2(Al1.5□0.5), and T(Si3.5Al0.5) positions are 0.95, 0.97, 2.31, and 3.97 valence units (vu), respectively, which is in agreement with the expected values given that various cations are present at the same sites. The low BVS for M2 suggests that it has a vacant cation position. The bond-valence sums for the O1, O2, and O3 positions are 2.11, 2.12, and 2.06 vu, respectively. The bond-valence sum for the A site, which is occupied by a hydroxyl group in luanshiweiite [1], is 0.89 vu for F in fluorluanshiweiite. As shown in Table 7, all the resulting BVS values are comparable to ideal values, and the model basically matches the charge balance requirement.

Table 7.

Bond-valence (vu) analysis for fluorluanshiweiite.

In conclusion, fluorluanshiweiite is the third light mica with substantial lithium and a stoichiometry intermediate between diocatahedral and trioctahedral; only two other Li micas have this stoichiometry: luanshiweiite [1] and voloshinite [2]. Fluorluanshiweiite can be considered as the F-dominant analogue at the A site of luanshiweiite or a K-dominant analogue at the I site of voloshinite (Table 8).

Table 8.

Comparative characteristics of fluorluanshiweiite and other minerals of the lepidolite species having a similar structure.

Author Contributions

K.Q., X.S., G.L., G.F., and G.S. designed the experiments and wrote the paper; G.L. collected the single-crystal X-ray diffraction data and analyzed the crystal structure data; L.Q. obtained the IR spectra and analyzed IR and Raman data; Y.W., X.L., and Z.X. obtained the lithium content data; and G.F. and H.G. collected the electron-microprobe data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support for this research was received from the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC Grant 41502033) and the China Geological Survey Project (DD20160129-3, DD20190813, 1212011120771).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ritsuro Miyawaki, Chairman of the IMA-CNMNC, and the members of the IMA-CNMNC for their helpful comments on the data submitted for the new mineral proposal. The reviewers and editor are acknowledged for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fan, G.; Li, G.; Shen, G.; Xu, J.; Dai, J. Luanshiweiite: A New Member of Lepidolite Series. Acta Mineral. Sin. 2013, 33, 713–721, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Pekov, I.V.; Kononkova, N.N.; Agakhanov, A.A.; Belakovsky, D.I.; Kazantsev, S.S.; Zubkova, N.V. Voloshinite, a new rubidium mica from granitic pegmatite of Voron’i Tundras, Kola Peninsula, Russia. Geol. Ore Depos. 2010, 52, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Sima, X.; Li, G.; Fan, G.; Shen, G.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, G.; Qiu, L.; Wang, Y. Fluorluanshiweiite, IMA 2019-053. CNMNC Newsletter No. 52. Mineral. Mag. 2019, 83, 887–893. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, S.; Mao, Y.; Fan, L.; Wu, X.; Lin, J. Mineralization and Prospection of Rare Earth Metals in the Koktogay Area; Chengdu University of Science and Technology Press: Chengdu, China, 1995; pp. 66–194. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Černý, P. Rare-element granitic pegmatites. I. Anatomy and internal evolution of pegmatite deposits. Geosci. Can. 1991, 18, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Černý, P.A.; Ercit, T.S. The classification of granitic pegmatites revisited. Can. Mineral. 2005, 43, 2005–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9th Laboratory of Chengdu Institute of Geology. The isotopic dating of geological ages of granites and pegmatites in the eastern part of the Eastern Tsinling. Geochimica 1973, 3, 166–172, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Qu, K.; Sima, X.Z.; Zhou, H.Y.; Xiao, Z.B.; Tu, J.R.; Yin, Q.Q.; Liu, X.; Li, J.H. In situ LA-MC-ICP-MS and ID-TIMS U-Pb ages of bastnäsite-(Ce) and zircon from the Taipingzhen hydrothermal REE deposit: New constraints on the Later Palaeozoic granite-related U-REE mineralization in the North Qinling Orogen, Central China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 173, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.J.; Li, H.K.; Chen, Z.H. Brief Review of the Study of Qinling Complex, Qinling Orogenic Belt. Geol. Surv. Res. 2003, 26, 95–102, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Geng, J.Z.; Huang, Y.Q.; Jian, G.P.; Wu, L.; Zhu, R.; Yu, H.C.; Qiu, K.F. Zircon U-Pb age and Lu-Hf isotopes of the dacite from Zaozigou Au-Sb deposit, west Qinling, China. Geol. Surv. Res. 2019, 42, 166–173, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Ge, X.; Li, G.; Yu, A.; Shen, G. Oxynatromicrolite, (Na,Ca,U)2Ta2O6(O,F), a new member of the pyrochlore supergroup from Guanpo, Henan Province, China. Mineral. Mag. 2017, 81, 743–751. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarino, J.A. The Gladstone-dale relationship: Part The compatibility concept and its application. Can. Mineral. 1981, 19, 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Beran, A. Infrared spectroscopy of micas. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2002, 46, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V. Infrared Spectra of Mineral Species: Extended Library; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; p. 459. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.C.; Hu, H.; Zhang, A.C.; Huang, X.L.; Ni, P. Pollucite and the caesium-dominant analogue of polylithionite as expressions of extreme Cs enrichment in the Yichun topaz–lepidolite granite, southern China. Can. Mineral. 2004, 42, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, D.A.; Bell, M.I.; Etz, E.S. Raman spectra and vibrational analysis of the trioctahedral mica phlogopite. Am. Mineral. 1999, 84, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, D.A.; Bell, M.I.; Etz, E.S. Vibrational analysis of the dioctahedral mica: 2M1 muscovite. Am. Mineral. 1999, 84, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.L.; Freeman, J.; Kuebler, K.E. Raman Spectroscopic Characterization of Phyllosilicates. In Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIII; Document ID: 20020045549; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tlili, A.; Smith, D.C.; Beny, J.M.; Boyer, H. A Raman microprobe study of natural micas. Mineral. Mag. 1989, 53, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, E. Optical vibrations in sheet silicates. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1973, 6, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nespolo, M.; Ferraris, G. Effects of the stacking faults on the calculated electron density of mica polytypes—The Durovic effect. Eur. J. Mineral. 2001, 13, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, M.; Cavazzini, G.; D’yakonov, Y.D.; Frank-Kamenetskii, V.A.; Gottardi, G.; Guggenheim, S.; Müller, G.; Neiva, A.M.R.; Radoslovich, E.W.; Robert, J.L.; et al. Nomenclature of the micas. Can. Mineral. 1998, 36, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.T.; Prewitt, C.T. Effective ionic radii in oxides and fluorides. Acta Cryst. B 1969, 25, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toraya, H.; Iwai, S.; Makimo, F.; Kondo, R.; Daimon, M. The crystal structure of tetrasilicic potassium fluor mica, KMg2.5Si4O10F2. Z. Krist. 1976, 144, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, J.L.; Maury, R.C. Natural occurrence of a (Fe, Mn, Mg) tetrasilicic potassium mica. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1979, 68, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki, R.; Shimazaki, H.; Shigeoka, M.; Yokoyama, K.; Matsubara, S.; Yurimoto, H. Yangzhumingite, KMg2.5Si4O10F2, a new mineral in the mica group from Bayan Obo, Inner Mongolia, China. Eur. J. Mineral. 2011, 23, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schingaro, E.; Kullerud, K.; Lacalamita, M.; Mesto, E.; Scordari, F.; Zozulya, D.; Ermabert, M.; Ravna, E.J. Yangzhumingite and phlogopite from the Kvaløya lamproite (North Norway): Structure, composition and origin. Lithos 2014, 210, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigatti, M.F.; Kile, D.E.; Poppi, M. Crystal structure and crystal chemistry of lithium-bearing muscovite-2M1. Can. Mineral. 2001, 39, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drits, V.A.; Zviagina, B.B.; McCarty, D.K.; Salyn, A.L. Factors responsible for crystal-chemical variations in the solid solutions from illite to aluminoceladonite and from glauconite to celadonite. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, F.C.; Sokolova, E.; Agakhanov, A.A.; Pautov, L.A.; Karpenko, V.Y. The Crystal Structure of Polylithionite-1M from Darai-pioz, Tajikistan: The Role of Short-Range Order in Driving Symmetry Reduction in 1M Li-Rich Mica. Can. Mineral. 2019, 57, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigatti, M.F.; Caprilli, E.; Malferrari, D.; Medici, L.; Poppi, L. Crystal structure and chemistry of trilithionite-2M2 and polylithionite-2M2. Eur. J. Mineral. 2005, 17, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigatti, M.F.; Mottana, A.; Malferrari, D.; Cibin, G. Crystal structure and chemical composition of Li-, Fe-, and Mn-rich micas. Am. Mineral. 2007, 92, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I.D.; Altermatt, D. Bond-valence parameters obtained from a systematic analysis of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1985, 41, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I.D. Predicting bond lengths in inorganic crystals. Acta Crystallogr. B 1977, 33, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).