Abstract

Emergency vehicles (EmVs) play a crucial role in providing prompt services to public rescue activities. However, due to the impacts of ordinary vehicles (OVs), EmVs are often blocked and cannot reach the rescue site in time. Therefore, a cooperative emergency vehicle priority driving scheme (CEVPDS) is proposed to ensure the EmVs’ travel efficiency. The proposed scheme is used for urban express roads under a vehicle-to-everything communications (V2X) environment and consists of two steps to ensure high-priority passage for the EmVs to reach the rescue accident site. The first step involves designing the EmV trajectory in advance. The second step requires the OVs to dynamically give way to the EmV by lane changing according to the EmV’s pre-planned trajectory established in the first step. Once the EmV trajectory is predefined, the relevant trajectory information is transmitted to surrounding OVs via V2X communication. OVs ahead of the EmV are then scheduled to provide adequate road space by lane changing, while the OVs behind it are prohibited from overtaking it. We conducted simulations using the SUMO platform. Compared with the Fixed-Lane Strategy (FLS), the proposed scheme achieves multiple improvements in multiple aspects: it drastically shortens the EmVs response time, significantly mitigates the impacts on OVs, and fewer lane changes for both EmVs and OVs. As a result, the scheme not only enhances the travel efficiency of EmVs but also guarantees the safety, symmetry, and efficiency of the overall urban traffic system.

1. Introduction

Emergency vehicles (EmVs), including ambulances, fire trucks, and police cars, play an important role in timely emergency rescue services. Their prompt arrival at an accident site is essential for rescuing victims and minimizing losses in emergency scenarios, such as natural disasters, traffic accidents, and fire incidents [1,2,3]. According to the World Health Organization, more than 5 million deaths occurred each year due to delayed trauma treatment by the end of 2018 [4]. After severe trauma, there are three distinct peaks of mortality. The initial peak, known as death at the scene, occurs within seconds or minutes after the trauma and accounts for approximately 50% of deaths. The second peak, referred to as early death, occurs within a few hours after the trauma and contributes to about 30% of deaths. The third peak, representing 10–20% of deaths, takes place 24 h after the trauma, typically within the first to fourth week following the injury [4]. Therefore, it is of great significance to ensure that emergency vehicles reach the accident site quickly and safely.

However, due to the rapid acceleration of urbanization, the number of vehicles has increased exponentially, so urban transportation is under great pressure, and traffic accidents and congestion happen occasionally. These bad road traffic conditions lead to the increment of EmVs’ rescue time. In order to improve the driving efficiency of both EmVs and OVs, particularly those of EmVs, lane changing is one of the most common schemes used [5,6,7]. Determining when and where EmVs and OVs should change lanes can efficiently enhance the overall driving efficiency.

Vehicle-to-everything communications (V2X), including vehicle-to-vehicle communication (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication (V2I), enable real-time communication between vehicles, allowing vehicles to dynamically plan routes based on real-time road conditions [8]. Most road traffic control-related schemes for road networks are based on V2X technology to obtain the real-time road condition data. For example, V2X communication combined with sensing sensors was used to collect real-time road condition data and further to warn OVs when EMVs approach [9] or announce their arrival [10], and also to notify drivers and passengers [11] via mobile applications integrated with such communication modules.

To ensure the efficiency of EmVs, many scholars have proposed many different solutions.

The authors in [12] proposed a fuzzy logic-based model to determine the degree of priority for emergency events, and some traffic signal control methods were employed to mitigate the adverse impacts on OVs and prevent grid-lock caused by emergency issues. Rosita et al. in [13] proposed a multi-criteria decision-making method that combined the vector normalization technique and Dijkstra’s algorithm. Wu et al. [14] formulated a cooperative driving problem as a mixed-integer nonlinear programming problem to potentially minimize disturbances to Connected Vehicles (CVs) based on an improved ant colony algorithm. Different from [14], Lin et al. [15] proposed an integer linear programming model to maximize Emv traffic efficiency and try to find trade-offs between interference with the OVs and smoothness of the EmV driving trajectories. Hannoun et al. [16] introduced an integer linear program (ILP) to facilitate EmV movement through transportation links. The ILP utilized V2V communications to identify the fastest intra-link path for EmVs, and it could easily be adapted to varying conditions. Authors in [17] aimed to identify the best lane for an EmV at a given time and then adjust its current position from the current lane accordingly. The authors in [18] proposed a control algorithm for platoons to yield to EmVs in the minimum time. Although various factors, including traffic density, platoon size, initial state, and speed limits, were taken into account in [18], the algorithm did not consider its adaptability to the environment. Ref. [19] proposed an Integrated Agile Decision-Making with Active and Safety-Critical Motion Planning System (IDEAM) that focused on enabling EmVs to actively achieve efficiency in dense traffic scenarios. In addition, a J2H approach [20] was proposed to control traffic signals and alert passers and vehicles, considering additional factors such as the number of lanes, emergency level, types of roads, and so on, to give the best way for the EmV to travel and reach its destination on time, which was based on V2X communication modules.

However, all the above-mentioned algorithms generate trajectories for EmVs by treating them as always running on a fixed lane, failing to account for the possible lane changes of EmVs. Such a limitation can result in frequent lane switches by OVs, potentially inducing road instability and safety incidents.

Cooperative driving, which is based on V2V information exchange beyond the sight of individual vehicles, is considered one of the useful ways for EmVs to pass the roadway quickly and safely [15]. In our previous works, we proposed a cooperative driving strategy called Safely Change Lane (SCL), which improved speed efficiency and successfully resolved traffic congestion caused by deadlock conditions based on V2V communications [21], and also proposed an overtaking function to improve vehicles’ travel efficiency by path planning according to cooperative driving [22]. Based on this, in this paper, we propose an efficient cooperative driving EmV priority scheme to further advance our previous research work. In this proposed scheme, EmV trajectory planning is performed and the relevant trajectory information is transmitted to OVs to facilitate the reservation of discontinuous lane spaces for EmV passage.

The primary objective of this paper is to ensure and enhance the passing priority of EmVs on urban express roads, while minimizing the impacts on OVs. Based on the V2X technology, this study enables cooperative driving available between EmVs and OVs, thereby improving the overall traffic efficiency of the entire road. Compared with current studies, this study presents two advantages. First, full consideration is given to minimizing the impact on OVs, so EmVs are not restricted to designated lanes, and they are allowed to make appropriate lane changes to reduce the impact on OVs’ lane changing. Second, a trade-off is achieved between improving EmV efficiency and reducing OVs’ lane changing frequency, and optimal entire road efficiency is obtained. This proposed scheme is suitable for urban express roads, and traffic signals were not considered. EmVs and OVs are not set into platoons or groups, but they cooperate with each other to realize a trade-off between EmV’s travel efficiency and less lane changes by OVs. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- We divide the road segment from the start to the destination into several cells and set the number of vehicles within a cell as the weight; thus, the road segment becomes a directed graph model. Based on the graph model, path planning for EmVs becomes more feasible.

- We propose an improved Dijkstra algorithm for planning paths to ensure the EmV’s priority. It integrates cell weight as the key factor to pre-plan the path for the EmV, then selects the path with the fewest lane changes of OVs, and the path of the EmV is not fixed to a specific lane but is adjusted by lane changing according to the actual cell weight conditions of the road segment, aiming to minimize the impact on OVs.

- A cooperative driving scheme for EmVs and OVs has been proposed. To ensure EmV passage efficiency, OVs need to provide road space for EmVds in a timely manner, and EmVs need to change lanes as required to minimize their impact on OVs, and thus, the overall efficiency of road traffic can be ensured.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the problem formulation and assumptions. Section 3 gives a detailed description of the proposed CEVPDS scheme. Section 4 gives the simulation and evaluation methodology and analyzes the results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Problem Statement and Assumptions

When emergency accidents occur, EmVs should arrive at the accident site as quickly as possible. Therefore, the urban express road without or with few traffic signals is the first choice for EmVs to travel with less time.

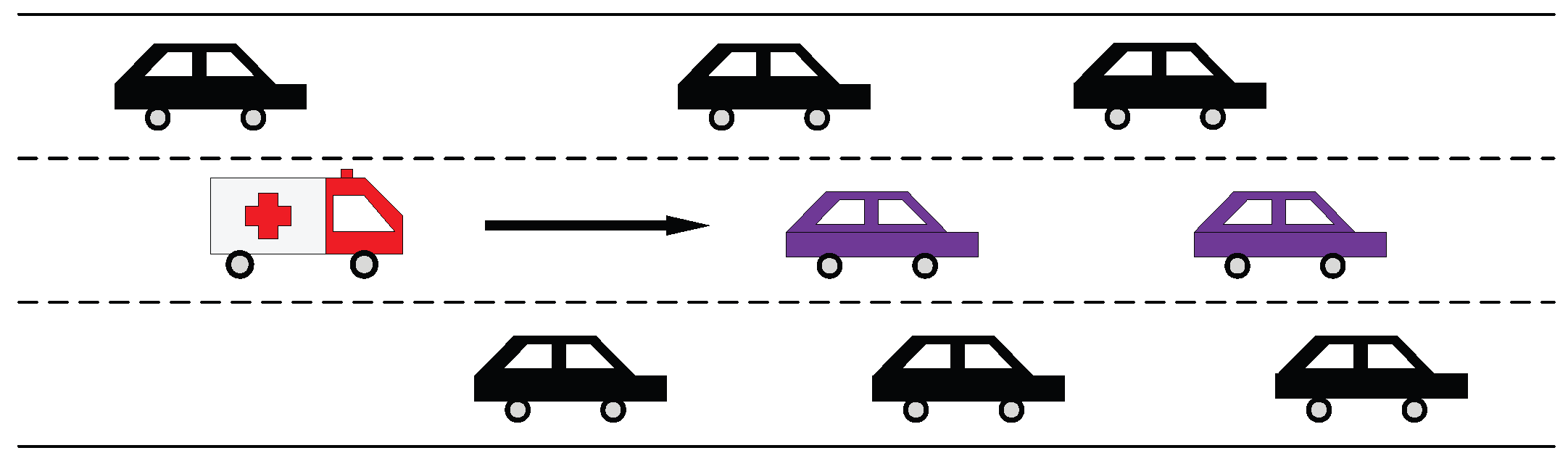

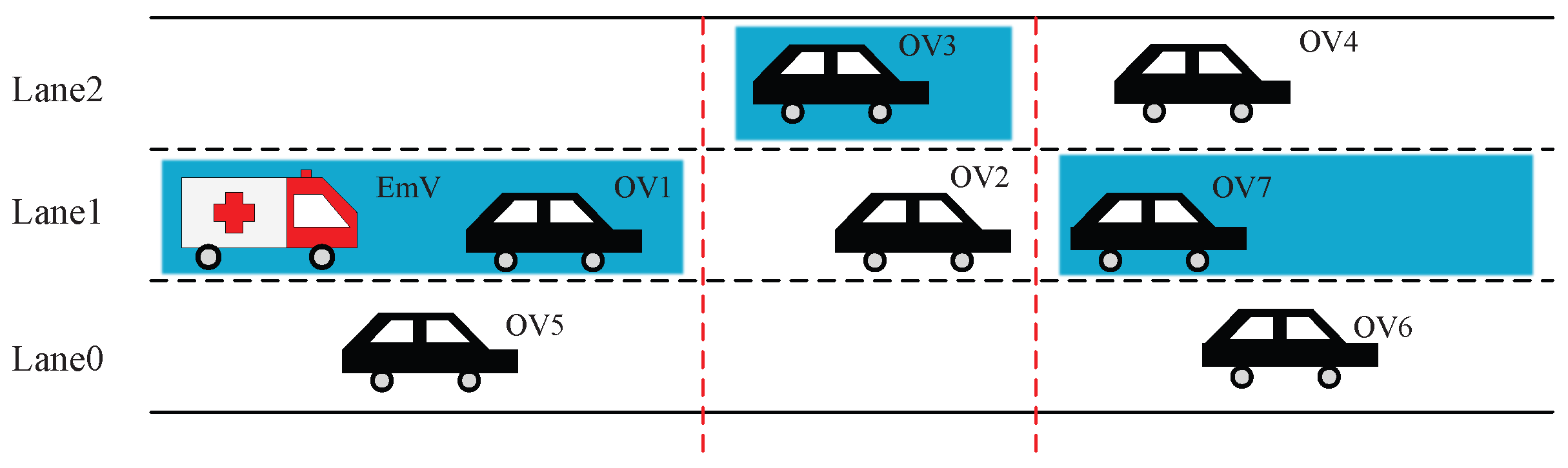

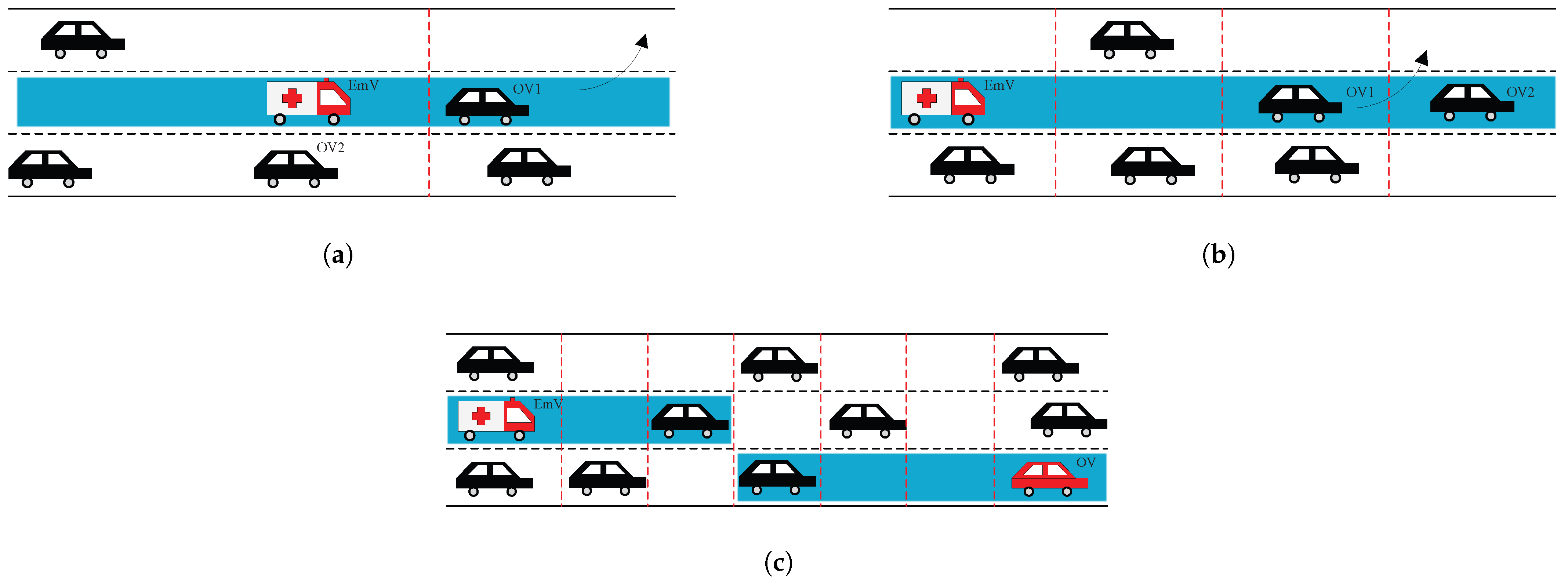

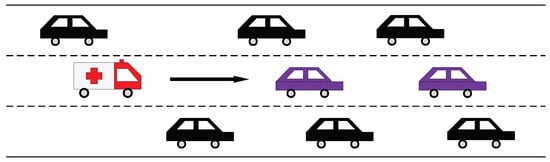

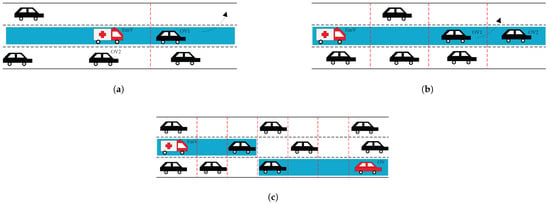

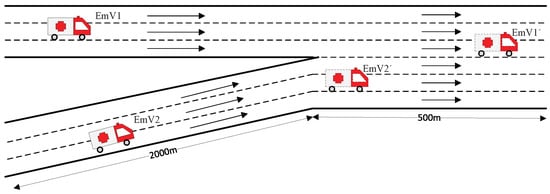

However, due to the effects of OVs, EmVs are easily blocked by low-speed OVs in the front, as shown in Figure 1. If there are no suitable traffic control strategies, traffic congestion may occur and EmVs will be blocked for a long time, because it is difficult for EmVs to get out of the deadlocked states, resulting in EmVs not being able to arrive at the accident site on time.

Figure 1.

An illustrative example of EmVs and OVs. The arrow in the figure indicate the moving directions of the vehicles.

To solve the above issue, we propose a cooperative emergency vehicle priority driving scheme, abbreviated as CEVPDS, based on V2X communication. With cooperation between EmVs and OVs, a suitable path planning algorithm is designed and feasible lane change schemes are performed between EmVs and OVs.

As shown in Figure 1, it is an urban express road segment. Vehicles move from left to right along the road. Two types of vehicles are considered: EmVs (which have time constraints to arrive at their destinations) and OVs (which do not have any travel time constraints). In Figure 1, the purple OVs obstruct the movement of the EmV, while being affected by surrounding OVs. This may trap the EmV in a deadlock, because it is difficult to overtake the two purple OVs to escape such a deadlock state without appropriate traffic strategies. To ensure that the EmV reaches the accident site promptly, it should be granted higher road access priority than the OVs.

Before introducing the proposed scheme, we make the following assumptions:

- Suppose that EmVs and OVs travel on urban express roads. To reach the accident site as quickly as possible, it is reasonable for the EmV to choose the urban express roads, as express roads typically have fewer traffic jams than urban ordinary roads. A similar assumption was adopted in [23], where pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles were not considered, as they can be adjusted within the reserved time according to real-time conditions.

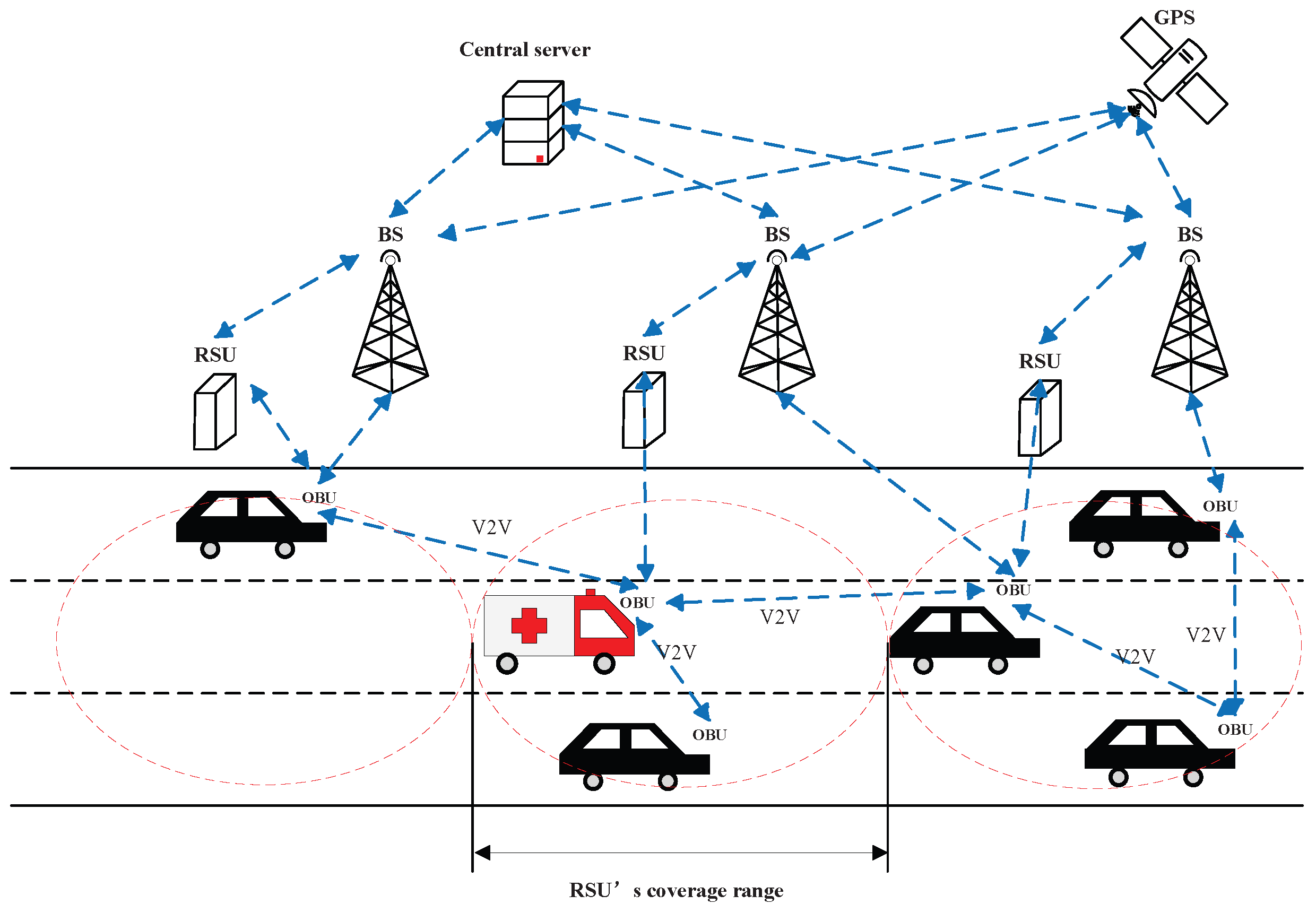

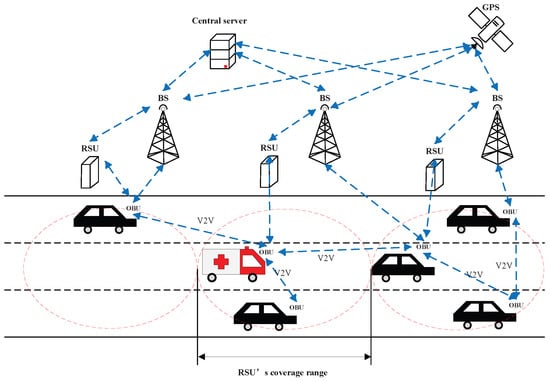

- Suppose all vehicles including EmVs and OVs are equipped with GPS and V2X communication models. Real-time road traffic conditions, such as each vehicle’s current position, speed, destination, acceleration, and directions, can be acquired via GPS [24,25] and shared among neighbor vehicles through V2X communication [26]. This assumption is reasonable because GPS models enable easy acquisition of vehicle speed, location, and destination, and V2X facilitates information sharing and updates between vehicles and traffic control centers, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. V2X communication for obtaining real-time road traffic information.

Figure 2. V2X communication for obtaining real-time road traffic information. - High-quality V2V and V2I communications are available, and the transmission data loss and delay in V2V and V2I connections are not considered [7]. The effects caused by V2X-related communication delay data loss will be considered in future work. As the transmission time for vehicular information to the surrounding vehicles is in milliseconds [27,28], compared to the driver’s reaction time in seconds [29], the transmission delay can be ignored.

- OVs that are behind the EmV are prohibited from overtaking it, while those in front of the EmV should give way to the EmV when feasible [30,31].

As shown in Figure 2, communication among the vehicles’ on board units (OBUs), road side units (RSUs), and base stations (BSs) is always available. The path planning algorithms will be done in RSUs in a distributed manner, and the real-time traffic data is saved and updated in the central server. Using this V2X communication structure, road traffic conditions and control results will be exchanged among vehicles.

3. The Proposed Cooperative Emergency Vehicle Priority Driving Scheme (CEVPDS)

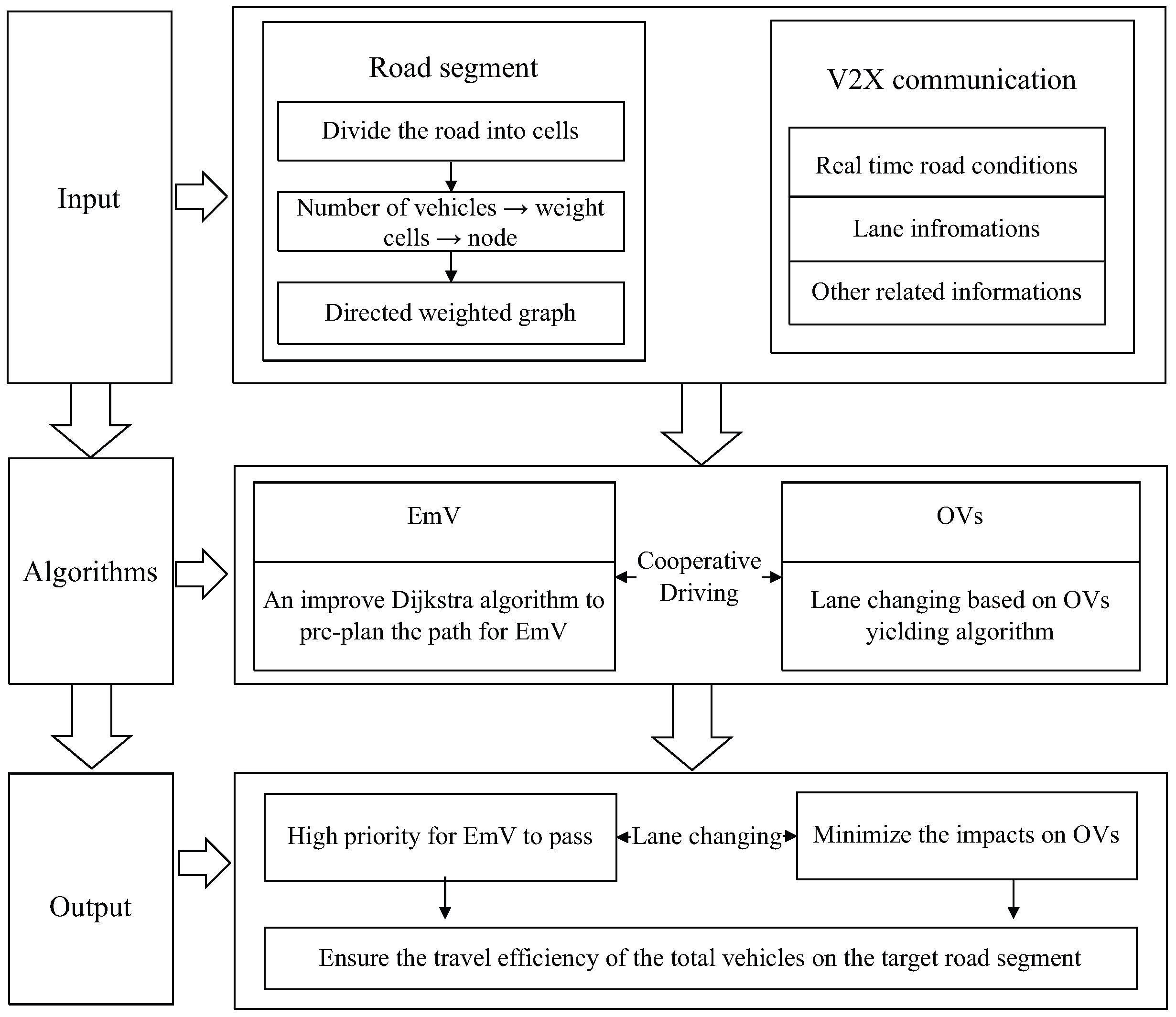

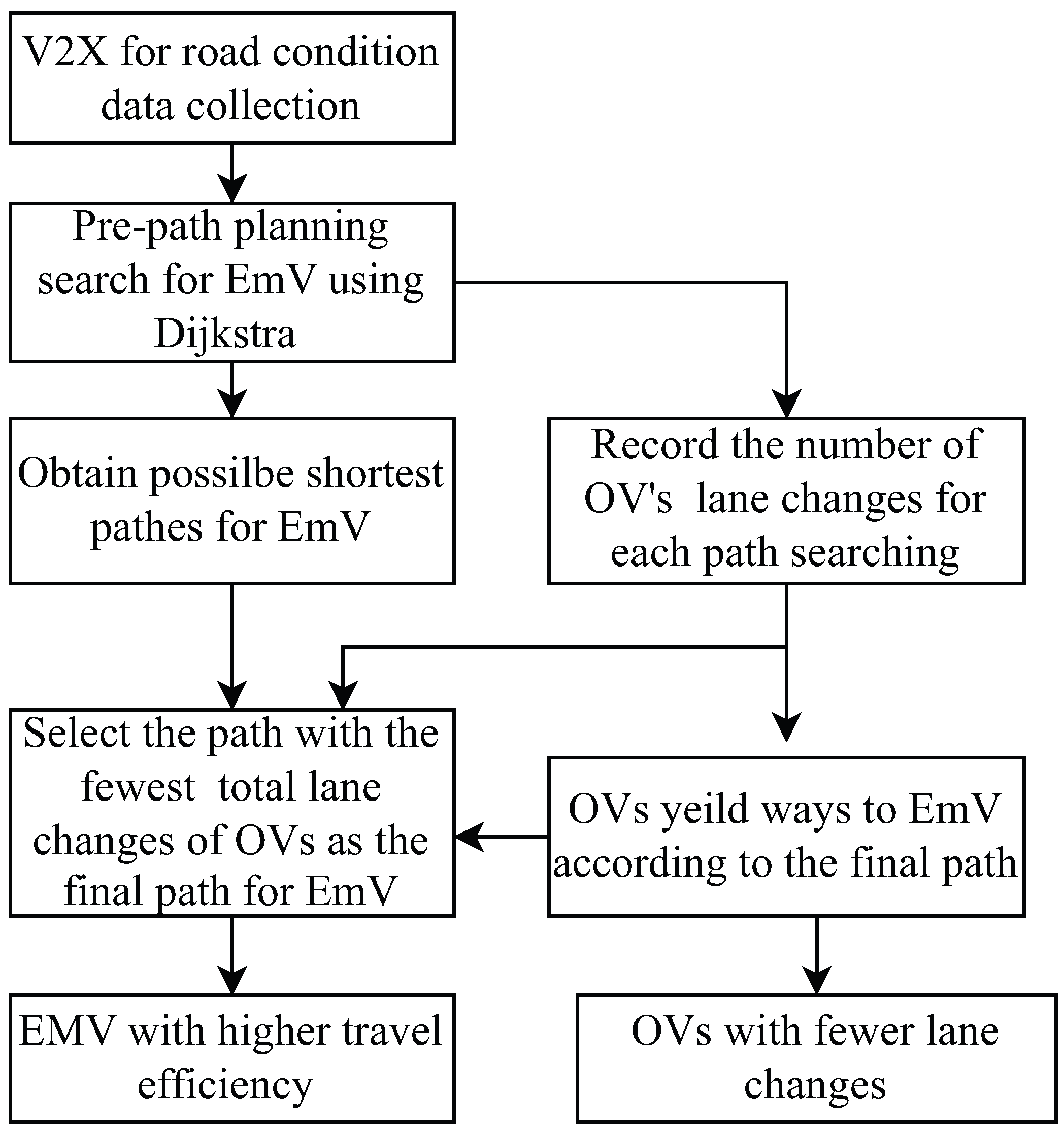

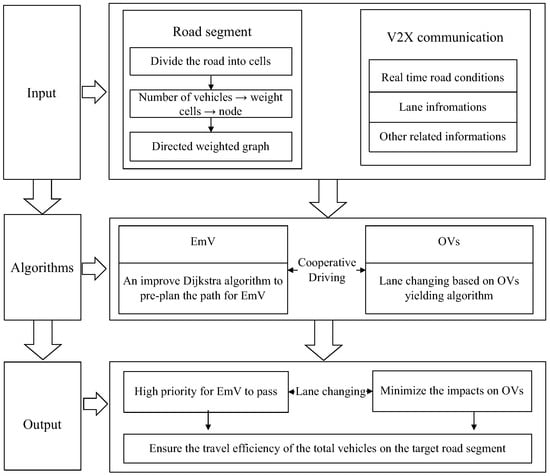

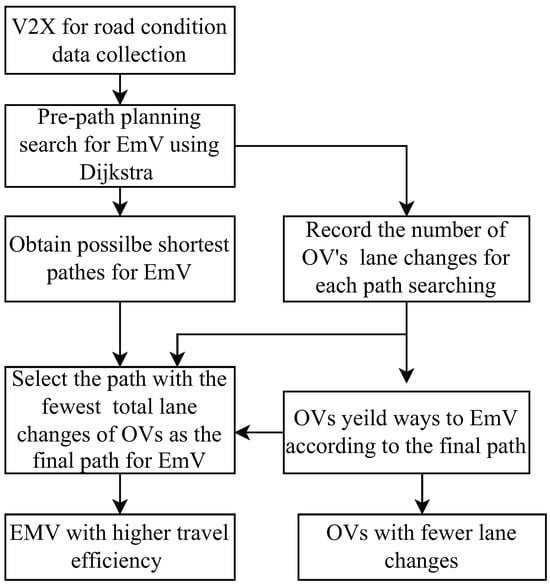

As mentioned in Section 2, the proposed CEVPDS is used for urban express roads to ensure the priority of EmVs. The proposed CEVPDS consists of three parts, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The construction of the proposed scheme.

The first part relies on V2X communication to acquire real-time road conditions and divide the road into cells. The number of vehicles in each cell is used as a weight to construct a weighted graph of the road.

The second part involves cooperative driving between EmV and OVs. Based on the road segment weighted graph established in the first part, an improved Dijkstra algorithm is used to find the shortest path for EmVs, and available road cells are released when OVs yield by lane changing.

The third part presents the output and results of the second part. The EmV is granted high priority to access as well as minimize impacts for OVs and ensures the travel efficiency of all vehicles on the target road segment.

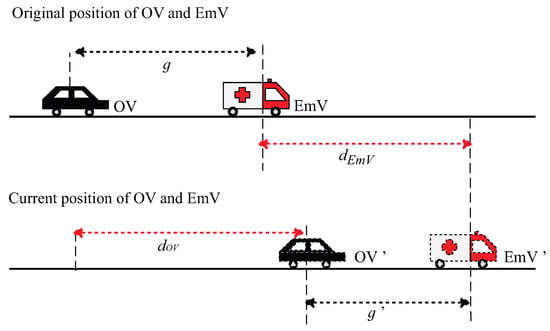

3.1. Cell-Based Trajectory Planning Algorithm for EmVs

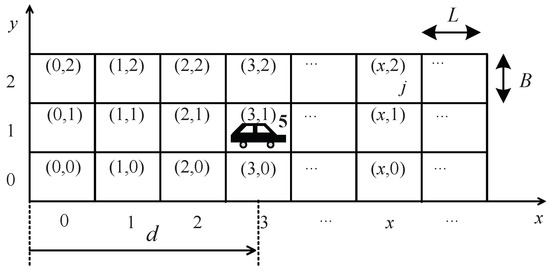

3.1.1. Discretizations of Road Network

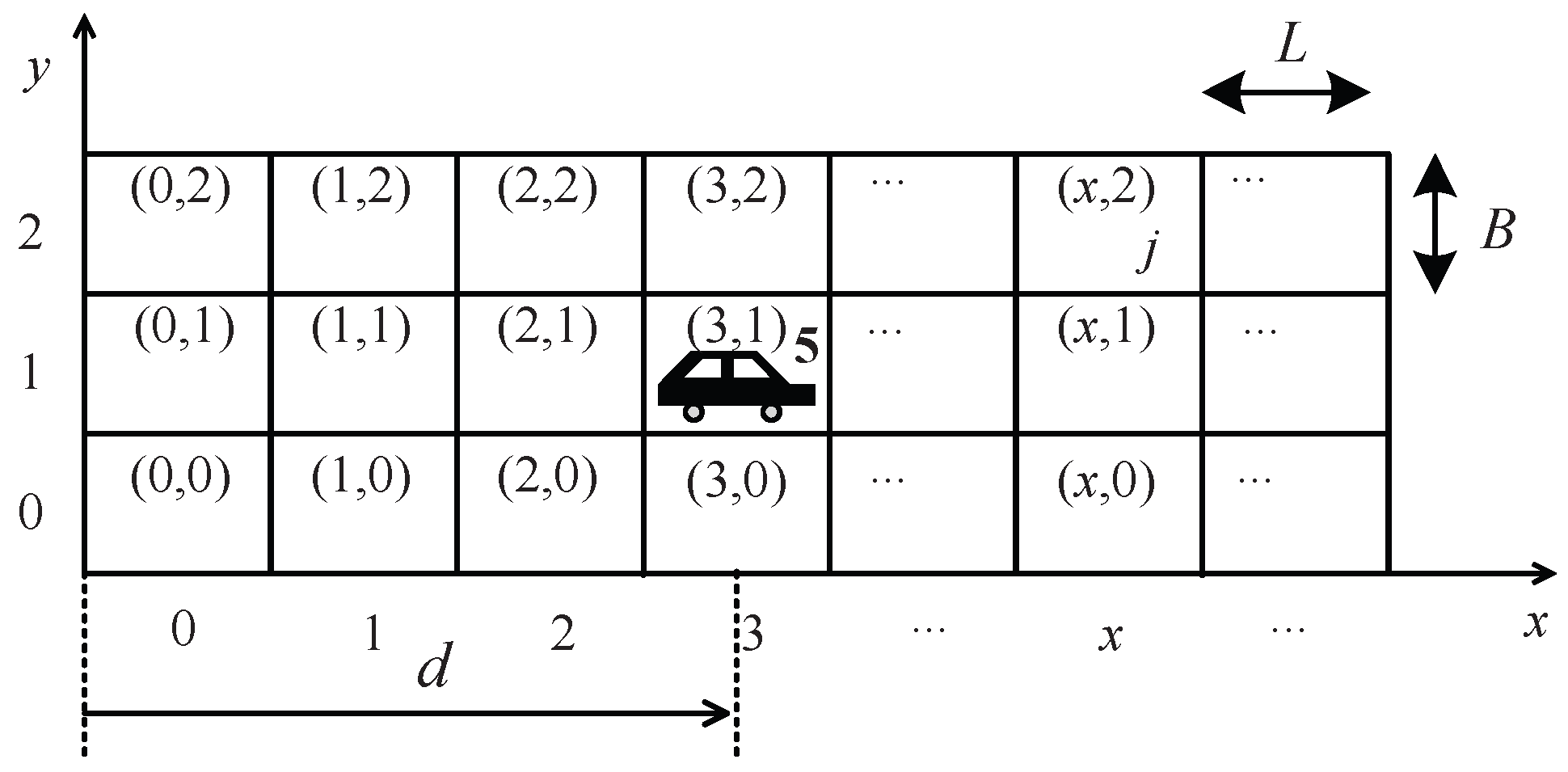

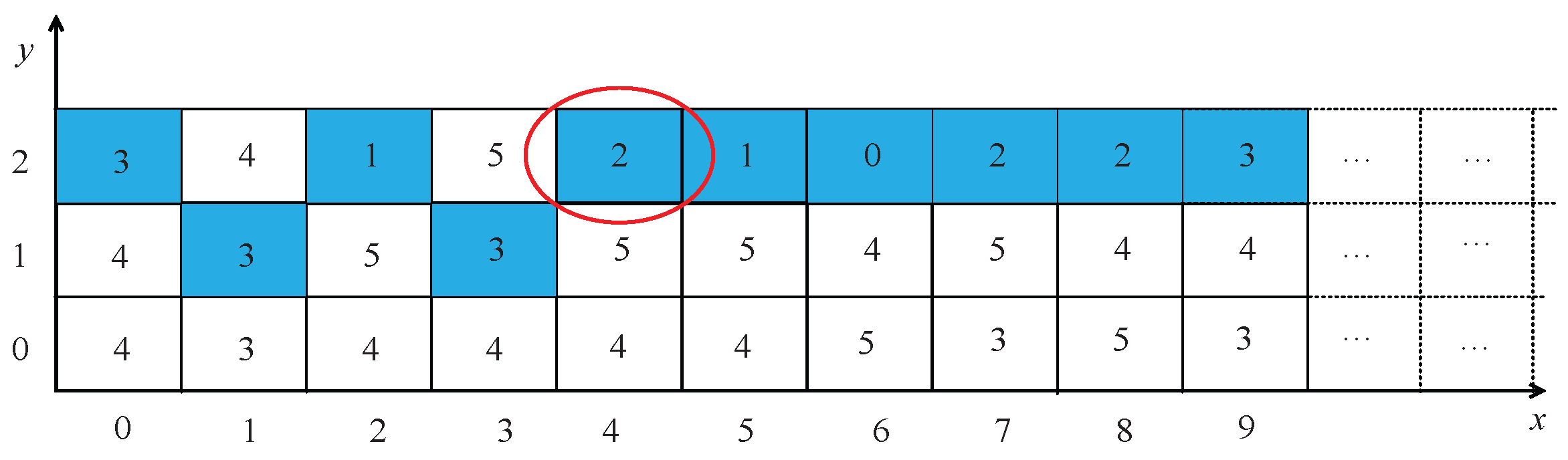

Take a 3-lane one-way road network as an example. A Cartesian Coordinate system is established where the vehicle’s driving direction is set as x-axis, and the lane extension direction as the y-axis. As shown in Figure 4, the road network is divided into several cells. The size of each cell is denoted as ×, where the width B is equal to the width of a signal lane, and the length L should be longer than the length of a vehicle . To prevent collisions during lane changes, L should be at least twice (). Parameter j is used to represent the number of OVs in each cell. Obviously, j meets inequality as . The coordinate of a cell is denoted as , where m is the horizontal index of the cell and n denotes the lane index where the vehicle is currently located. Taking C(0, 0) as the starting point, the horizontal distance d between C(0, 0) and the vehicle’s current position satisfies .

Figure 4.

Discretizations of roadway network.

Take the black vehicle illustrated in Figure 4 to explain the aforementioned content. This black vehicle is located in cell C(3, 1), indicating it is in the fourth cell of the second lane. And the number “5” means that there are 5 OVs in the cell C(3, 1). In addition, the distance d for this vehicle satisfies .

After discretizations of the road network, it is divided into numerous cells. From a macro perspective, each cell can be regarded as a fixed-position node. These nodes and the directed edges between them collectively form a directed graph, where the connecting directed edges represent the trajectories of vehicle movement. Thus, both the trajectory planning of the EmV and the lane-changing of OVs can be transformed into problems in graph theory.

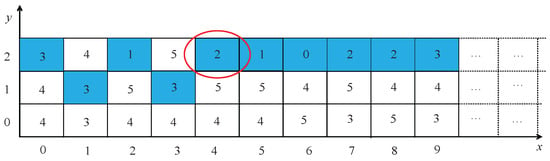

3.1.2. Directed Weighted Graph

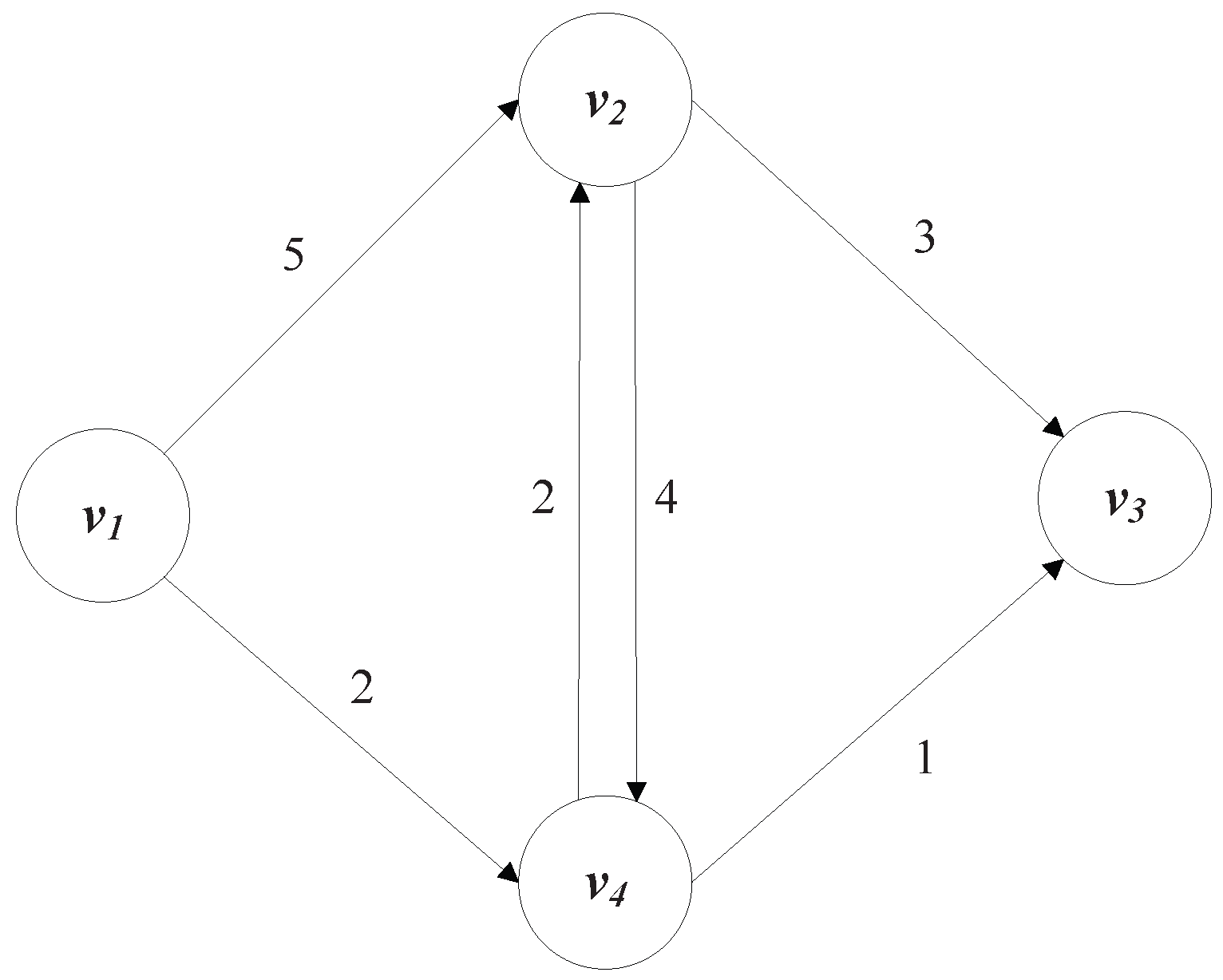

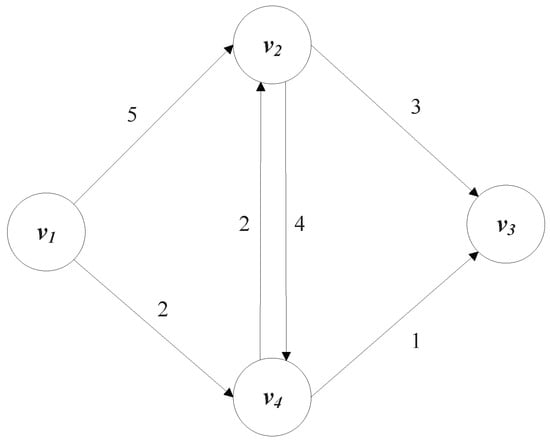

Define a directed weighted graph as , where V denotes a non-empty set of nodes; E is the set of edges corresponding to each link; and W represents a weight function mapping E to the set of positive real numbers. A directed edge in E is denoted by an ordered pair of nodes from V. If a directed edge , then node v is reachable from node u in E. The weight of edge is denoted by .

A path between two nodes and is a finite sequence , consisting of sequentially connected nodes, i.e., for all , . The weight of this path is given by . The shortest path from node u to v, denoted as , is defined as the minimum weight among all possible directed paths from the origin node u to the destination node v.

Take a simple graph presented in Figure 5 as an example. There are 4 nodes (, , , and ) on the directed graph. Each line represents a directed edge, and the data on each line indicates the weight. There are several paths from to , such as path with a weight of 8 (that is, 5 + 3 = 8), path with a weight of 10 (that is, 5 + 4 + 1 = 10), path with a weight of 3 (that is, 2 + 1 = 3), and path with a weight of 7 (that is, 2 + 2 + 3 = 7). So the shortest path from node to node is .

Figure 5.

A directed weighted graph.

Vehicle path planning will be designed among the cells based on graph theory. Before designing the path planning, the following rules are established to allow vehicles to move between cells.

- The number of vehicles in a cell depends on the cell size and road vehicle density. A cell can contain multiple vehicles, but each vehicle belongs to only one cell.

- For cells sharing the same x-coordinate, only one is selected as a candidate for the EmV’s pre-designed trajectory. For example, if cell is included in the EmV’s future trajectory, cell and become inaccessible, because vehicles cannot cross two lanes at once to avoid road accidents.

- Vehicles are prohibited from continuous lane changes. When a vehicle is in cell , it cannot directly access cell (if such cells exist) or , that is, no continuous lane changes cross three consecutive cells. For a three-lane case, this prohibits direct lane changes between the leftmost and rightmost lanes (and vice versa). Continuous lane changes force vehicles to decelerate, leading to rear vehicle accumulation, traffic congestion, and even collisions.

- Vehicles are only allowed to move forward, not backward. So directed edges can only be established between a cell and the cells ahead of it, not those behind.

3.1.3. Path Planning Algorithm for EmVs

In order to maintain the EmV’s high travel efficiency, we propose an improved Dijkstra algorithm based on road cells. The Dijkstra algorithm was a classic shortest path algorithm for single-source vertices [32], and its computational complexity depends on the number of nodes (n) and edges(m) in a graph. Consequently, the computation complexity in this paper is . The cell number n is the node number which is associated with the road length and number of lanes. The edge number m is determined by the number of vehicles in each cell. Therefore, the complexity in the proposed scheme is related to the road type and vehicle traffic density. Our path planning for EmVs is detailed below with the following steps:

- Step 1: Construct cell sets S and U. S stores cells with confirmed shortest paths, and U contains untraversed cells.

Set the source cell to be , and the destination cell is . Set three arrays: to store the minimum travel distance, initialize = ∞; to record the predecessor cells for subsequent path backtracking, initialize ; to account for the number of lances among cells, and initialize .

- Step 2: Traverse all cells in set U to find all the possible optimal paths from to .

If < , select as the next target source cell. Move from U to S and update , record , and count lane change times from current_cell to .

Repeat Step 2 until all the cell in U are traversed and moved to S.

- Step 3: Calculate the number of lane changes both for OVs and EmV for each shortest path , and select the path with the fewest lane changes as the final path for EmVs.

- Step 4: Output the shortest path result for EmVs.

The basic diagram for EmV path planning is presented in Figure 6. The Dijkstra algorithm is used to find the possible paths for EmVs, and when searching each possible path, the number of lane changes is recorded. Then, considering the lane change times, the EmV selects the path with the fewest as the final path, and other OVs will yield to the EmV according to the final path.

Figure 6.

Path planning diagram.

3.2. The Yielding Algorithm for OVs

As outlined above, the EmV’s pre-planned trajectory is generated in advance using the improved Dijkstra algorithm to ensure its higher priority over OVs. Consequently, OVs ahead must yield to the EmV, while those behind are prohibited from overtaking it.

3.2.1. When OVs Are in Front of the EmV

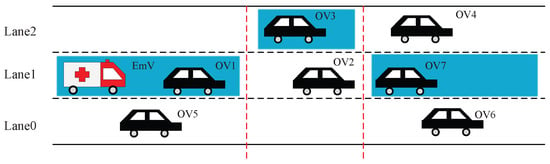

Figure 7 illustrates a 3-lane road segment divided into cells. When the EmV enters this segment from Lane 1, its path is planned using the improved Dijkstra algorithm, with the pre-planned route marked in blue.

Figure 7.

Path planning scenario.

OVs must take different actions based on their relative positions to the EmV to ensure its priority. Specifically, several OVs are ahead of the EmV with varying positions: OV1 is in the same cell as the EmV, OV3 and OV7 lie on the pre-planned path, OV2 is approaching the path, OV4 has just exited the path, and OV5 and OV6 remain distant from the path.

Thus, set the EmV as a reference node, and OV locations are simply categorized into three scenarios: in the EmV cell (e.g., OV1), not in the EmV cell but on the pre-planned route (e.g., OV2, OV3 and OV7), and outside the route (e.g., OV5 and OV6).

To facilitate smoother lane yielding and reduce vehicle lane changes, each OV’s position after time t must also be considered. For instance, OV7 may depart from the pre-planned route after a certain time and thus not affect the EmV when it arrives at this cell. Let d denote the current position (distance from the starting point in meters) and denote as the position after time t.

It is easy to obtain the as follows:

where and are the initial speed and acceleration for OV, respectively. So, the vehicle cell after time t is (), where = denotes the largest integer less than or equal to , L is the cell length, and y is the lane index.

The specific lane changing algorithms for OVs ahead of the EmV, corresponding to their different positions, are detailed in the following three cases.

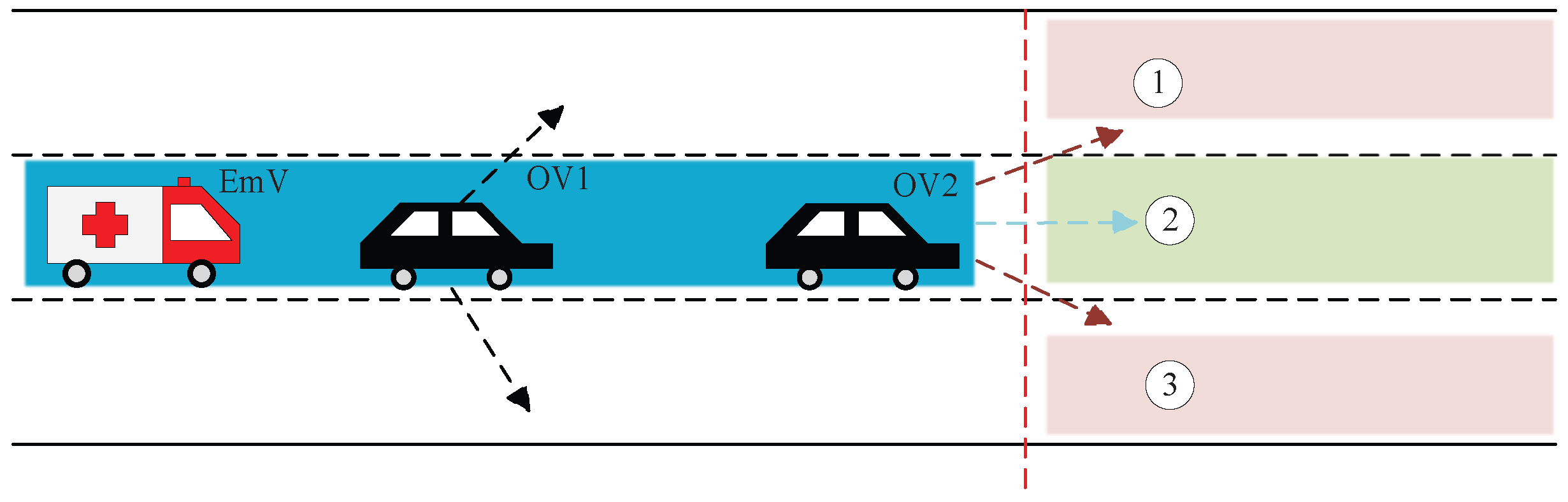

- Case 1: OVs and EmV in the same cell.

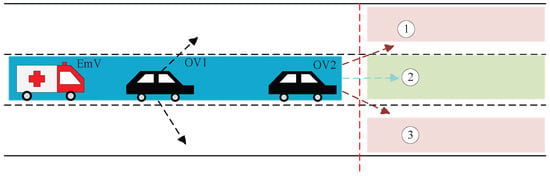

As shown in Figure 8, when OVs and EmV are located in the same cell, the maximum distance between them equals the cell length L. If the OV maintains a constant speed and remains in its current lane without any lane changes, the faster-moving EmV will be in a deadlocked state. Thus, the OVs have to change lanes to free up space for the EmV’s passage.

Figure 8.

Case 1: OVs and EmV in the same cell.

After t time, if the OV remains on the EmV’s pre-planned route, such as the case in the Figure 8, the OV1 that ahead of the EmV must yield.

If lane changing is feasible, the OV moves to an adjacent lane. If not, the vehicle priority is adjusted as follows: EmV > OVs in the Emv’s current cell > other OVs (which are nearby but not on the route). Lower-priority vehicles yield to higher-priority vehicles. As a result, in order to ensure the OV1 changes lanes successfully, other vehicles like OV2 must make space for OV1. For example, in Figure 8, if the EmV’s pre-planned path includes cell ①, OV2 leaves the current cell to the ahead cell ② after t, allowing OV1 to pass straight, and the EmV has enough space to move into the cell ①. However, if cell ② is part of the EmV’s pre-planned route, OVs cannot move to this cell ②, OV1 and OV2 must instead change lanes to cell ① or cell ③.

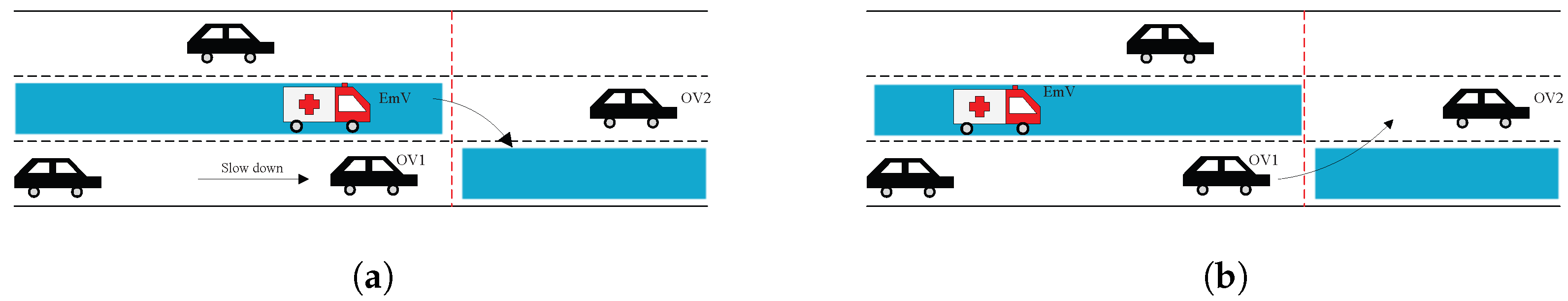

- Case 2: OVs on the pre-planned route (different cells from the EmV).

As shown in Figure 9, the blue path is the pre-planned route for the EmV. This case involves OVs not sharing the EmV’s cell with the EmV but lying on its potential pre-planned route (e.g., OV1 and OV2). This case can be divided into two scenarios: OVs close to the EmV (as shown in Figure 9a,b), and OVs far from the EmV (as shown in Figure 9c).

Figure 9.

Case 2: OVs on the pre-planned route (different cells from the EmV). (a) One cell away; (b) several cells away; (c) too far away.

As shown in Figure 9a, when OVs are one cell away from the EmV, the EmV’s typically higher speed means front-route OVs within a certain distance significantly impact its travel. These OVs must change lanes to yield the route for the EmV, so the front OV1 needs to immediately make space to avoid forcing the EmV to decelerate. If OVs are preparing to exit the route, they should accelerate through the current cell.

As shown in Figure 9b, OV1 is two cells away from the EmV, so it has a higher probability of successfully changing to adjacent lanes rather than other surrounding OVs. In addition, this scenario will transition to Figure 9a after a certain time.

As shown in Figure 9c, when OVs are on the pre-planned route but far away from the EmV, their impacts on the EmV are relatively small. These OVs need to pass through the current cell as quickly as possible until the scenario transitions to Figure 9b.

- Case 3: OVs not on the EmV’s pre-planned route (different cells from the EmV).

If OVs are not on the pre-planned route, they will not affect the EmV initially, but improper trajectory handling may lead to future interference. Thus, OVs within a certain distance still have some influence on the EmV. These OVs must stay clear of the pre-planned route to ensure the EmV’s smooth and timely passage. If OVs will not enter the route later, they maintain their current speed and direction. If they are to enter the route, actions are determined based on their entry location and time, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Case 3: OVs not on the EmV’s pre-planned route. (a) OV close to EmV, (b) OV far away from EmV.

In Figure 10a, OV1 will enter the pre-planned route just as the EmV prepares to enter the next cell, creating a potentially conflicting situation. To avoid collisions and ensure the EmV’s priority, OV1 must first slow down and then proceed to the next operation only after the EmV enters the corresponding cell.

In Figure 10b, OV1 plans to enter the pre-planned route soon, but the EmV stays in its current cell; OV1 only needs to change to the adjacent lane before the EmV arrives.

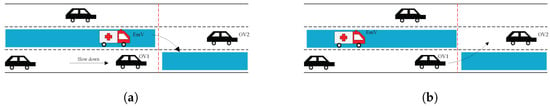

3.2.2. When OVs Are Behind an EmV

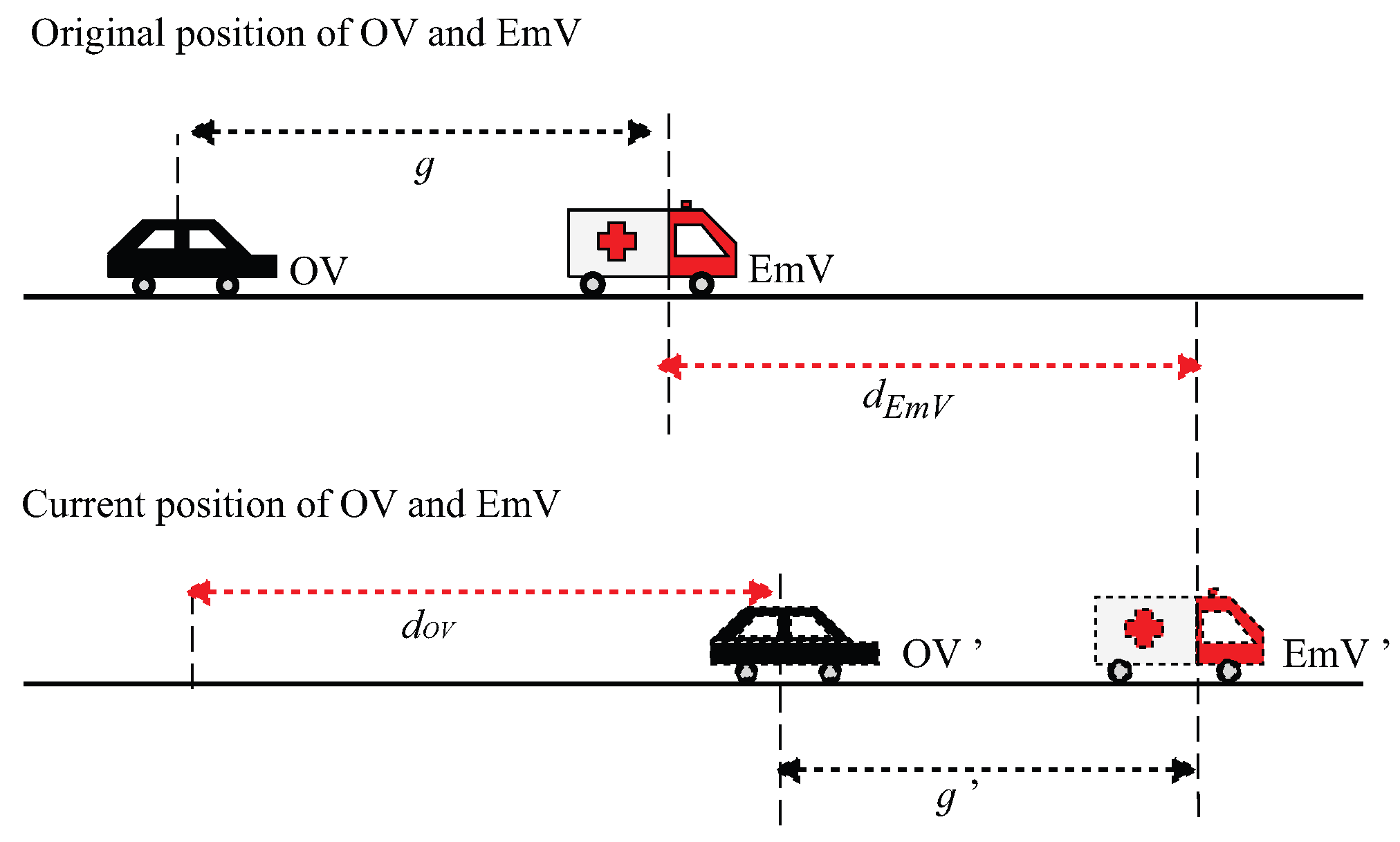

As shown in Figure 11, the OV follows the EmV in the same lane and route. After a certain time t, their new positions are denoted as OV’ and EmV’, respectively. Let g be the initial distance space between the OV and EmV, and denote the distances traveled by each during this period, and is the subsequent distance between OV’ and EmV’.

Figure 11.

Position relationship between the rear OV and the EmV.

Assuming both vehicles undergo uniformly accelerated straight line motion at time t, and are the initial speeds of OV and EmV, and represent the current speeds of OV and EmV, respectively, and and represent their accelerations.

After time t, the traveled distance for EmV and Ov can be obtained as follows:

The current speed of the OV after time t is

Take the square of both sides of Equation (4), and combine Equation (3), we derive the in term of as following equation.

According to the distance relationship depicted in Figure 11, Equation (7) for is obtained as follows.

The term is used to estimate the influence extent of the OV on the EmV. A sufficient but not essential condition for minimizing this influence is to ensure . That is the following in Equation (7).

that is

By combining Equations (5) and (8), the in-equation is derived as follows.

that is

Taking the square root of the both sides Equation (10),we get the following.

When the EmV is unaffected by other OVs, it will travel smoothly without acceleration. Hence, its acceleration . Let in Equation (2) be 0, and substitute Equation (2) for in Equation (11), then the speed of the OVs is expressed as follows.

According to the above (12), for OVs behind the EmV, their speed can be adjusted based on relative distance and EmV’s speed to slow down and avoid overtaking the EmV.

4. Simulation and Evaluations

In order to verify the performance of the proposed CEVPDS scheme, simulation evaluations are conducted using Python V3.10.9 and the SUMO V1.22.0 platform [33]. SUMO is utilized to construct street simulation scenarios, define the behaviors of EmVs and OVs, and generate relevant evaluation data by running simulations. Traffic flow is generated via SUMO’s vehicle demand generator following a Poisson distribution, matching the required traffic densities.

Two types of vehicles are configured: EmVs and OVs. The key parameters of these vehicles in the simulations are summarized in Table 1. Notably, the EmV’s speed exceeds the road’s maximum speed limit under the premise of safety, and EmVs are not restricted by driving routes, directions, speeds, or traffic signals [34]. All simulations use the Krauss model [35] to ensure vehicle safety, as it is a crash-free model where vehicles never exceed safe speeds [36].

Table 1.

Basic parameters of vehicles used in the simulation.

The road segment consists of three lanes, named Lane 2, Lane 1, and Lane 0, with the leftmost lane designated as the fast lane and the rightmost lane as the slow lane. The road conditions and simulation parameters are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Road condition parameters used in the simulation.

In the following simulation evaluation, three aspects are focused on. First, the performance of the proposed path planning algorithm is evaluated. Second, the traffic efficiency of a single EmV is presented; and third, the traffic efficiency of two interacting EmVs is analyzed. These aspects are discussed in the following.

4.1. Path Planning Algorithm Simulation

Several experiments are conducted under different traffic densities. The traffic flow is generated by a SUMO vehicle demand generator following a Poisson distribution to match the required traffic densities. The computational complexity of the proposed scheme is . Our simulation is done on a personal PC with an i7 processor. The results indicate that the proposed path planning algorithm still achieves an average execution time of 0.0015 s, even under different traffic densities. As reported in [29], the average driver reaction time is approximately 0.68 s. As the algorithm’s execution time is far shorter than the driver’s reaction time, it can be neglected in practical scenarios.

Taking a traffic density of 3500 veh/h as an example, the pre-planned route for the EmV is marked in blue in Figure 12, which is obtained by the improved Dijkstra algorithm. The data value in each cell represents the number of OVs when the EmV enters the road segment. For example, the blue cell encircled in red indicates a value of 2, indicating 2 OVs in that cell segment which the EmV will traverse.

Figure 12.

EmV path planning when at 3500 veh/h.

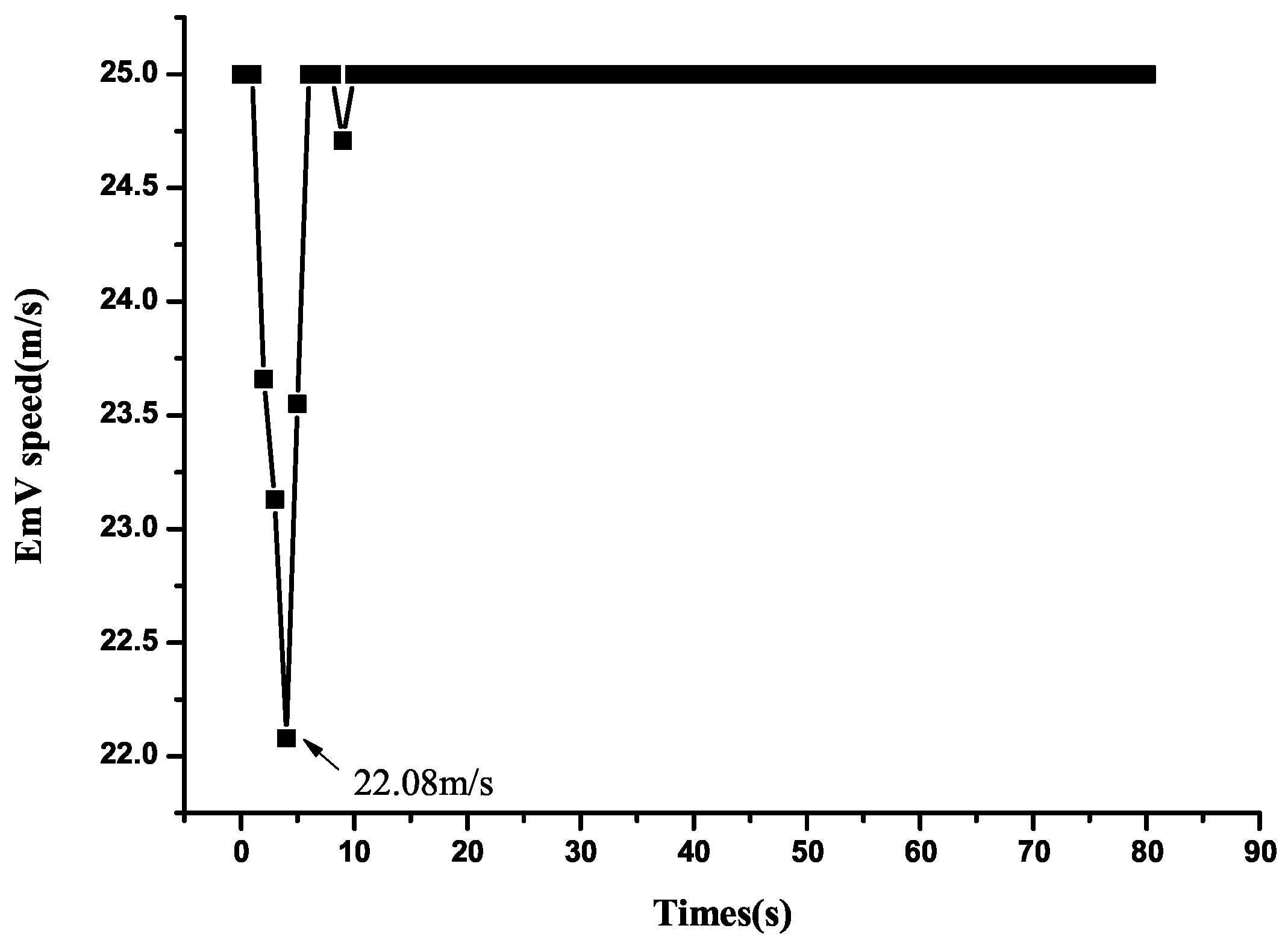

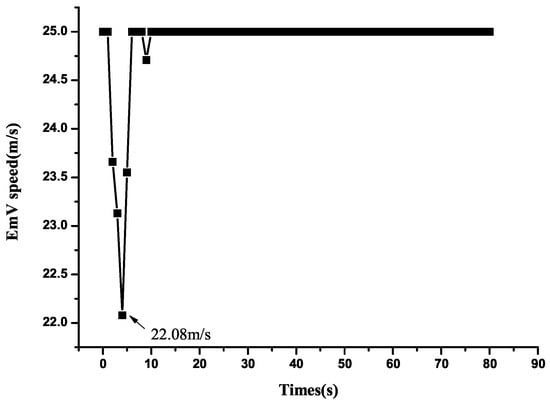

The EmV’s speed variation is shown in Figure 13. The results reveal that the EmV maintains a stable speed of approximately 25 m/s for most of the journey, but has a notable speed reduction to about 22.08 m/s. This speed fluctuation occurs because OVs ahead of the EmV fail to change lanes promptly due to surrounding conditions, so the EmV needs to decelerate moderately to maintain a safe distance.

Figure 13.

EmV speed variation under the CEVPDS algorithm at 3500 veh/h.

4.2. Performance Comparison for a Single-EmV Case

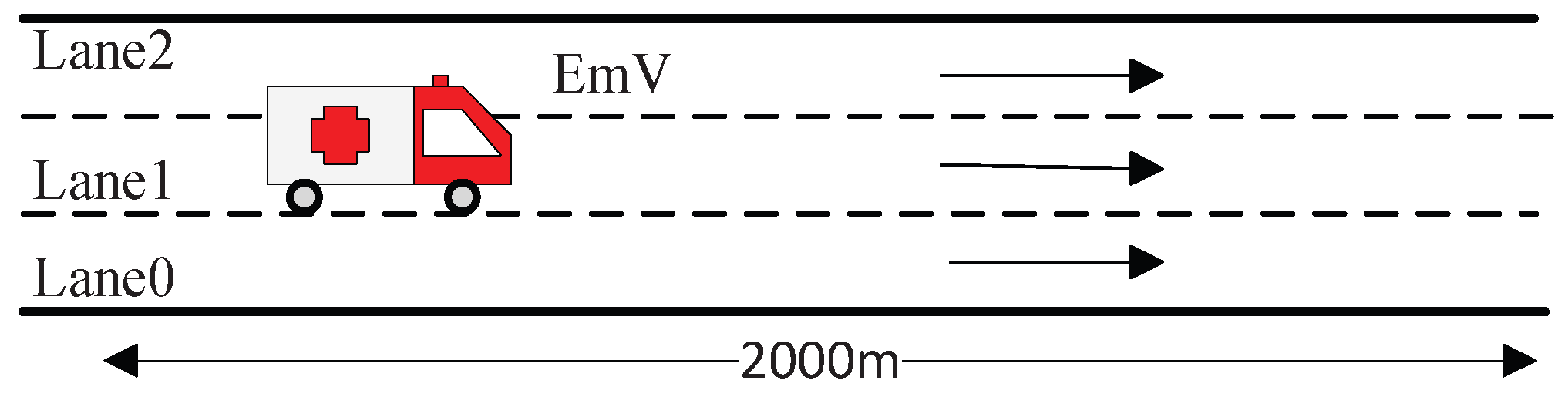

We compared the proposed scheme with the Fixed-Lane Strategy (FLS) proposed in [17]. In the FLS, the pre-planned trajectory of the EmV was fixed on a specific lane throughout its journey according to prior information. This fixed lane enables the EmV to travel faster compared to the other lanes [17]. Considering the scope of our current findings, we only conducted comparisons with the FLS scheme in this study, and a comparative analysis with other new recent baseline schemes will be undertaken in our future work. To evaluate the proposed scheme, four metrics are selected: average speed, response time of the EmV, lane change times of OVs, and EmV speed variance. The simulation scenario for a single EmV is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The road scene for the single-EmV case. The arrows in the figure indicate the moving directions of the vehicles.

- (1)

- Average speed of EmV

The average speed of EmV is a direct indicator of traffic efficiency and road smoothness. It is calculated as follows:

where denotes the speed of the EmV at the moment t, and T is the total travel time from the start to the destination.

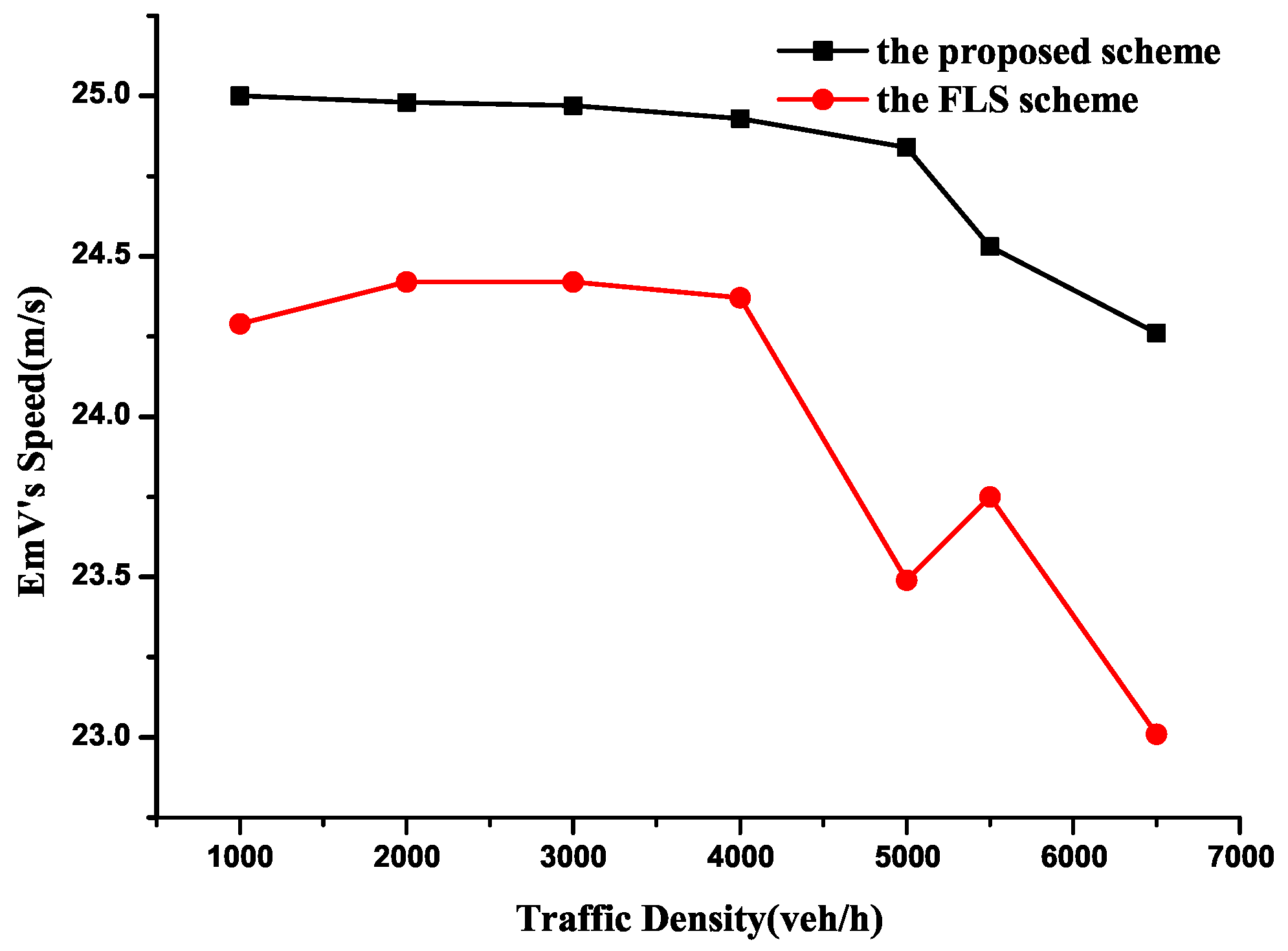

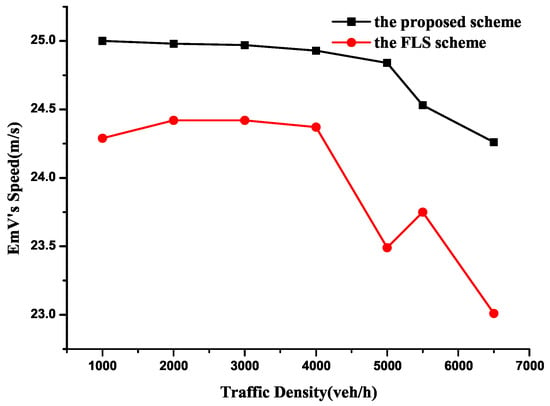

Figure 15 presents the average speed of EmV comparison between the proposed CEVPDS scheme and the FLS scheme. It is evident that the proposed CEVPDS scheme outperforms the FLS in terms of EmV average speed across different traffic densities, with the speed gap between the two schemes gradually widening as traffic density increases. When traffic density is below 4000 veh/h, the EmV speeds under both two schemes remain stable at approximately 24.9 m/s and 24.5 m/s, respectively. However, as densities exceed 4000 veh/h, the average speed variation curve is relatively fluctuated. Especially, at 5000 veh/h, the FSL’s red speed curve drops sharply, while the proposed scheme’s black speed curve is relatively smooth. The reason for this phenomenon is as follows: the road traffic congestion is likely to occur when density exceeds 5000 veh/h. Since OVs typically travel slower than EmVs, the EmV is easily blocked by preceding OVs under high-density conditions. For the FLS, the EmV is confined to a fixed lane without lane changing flexibility, forcing it to wait for preceding OVs to clear before escaping the congested state. Thus, this waiting period reduces the EmV’s speed and prolongs its travel time. In contrast, our proposed scheme grants the EmV higher priority than OVs, enabling it to quickly switch to alternative suitable lanes and depart the congested segment promptly. As a result, the EmV’s speed variation is minimized, and substantial waiting time is saved.

Figure 15.

Comparison of average speed.

- (2)

- Response time of EmV

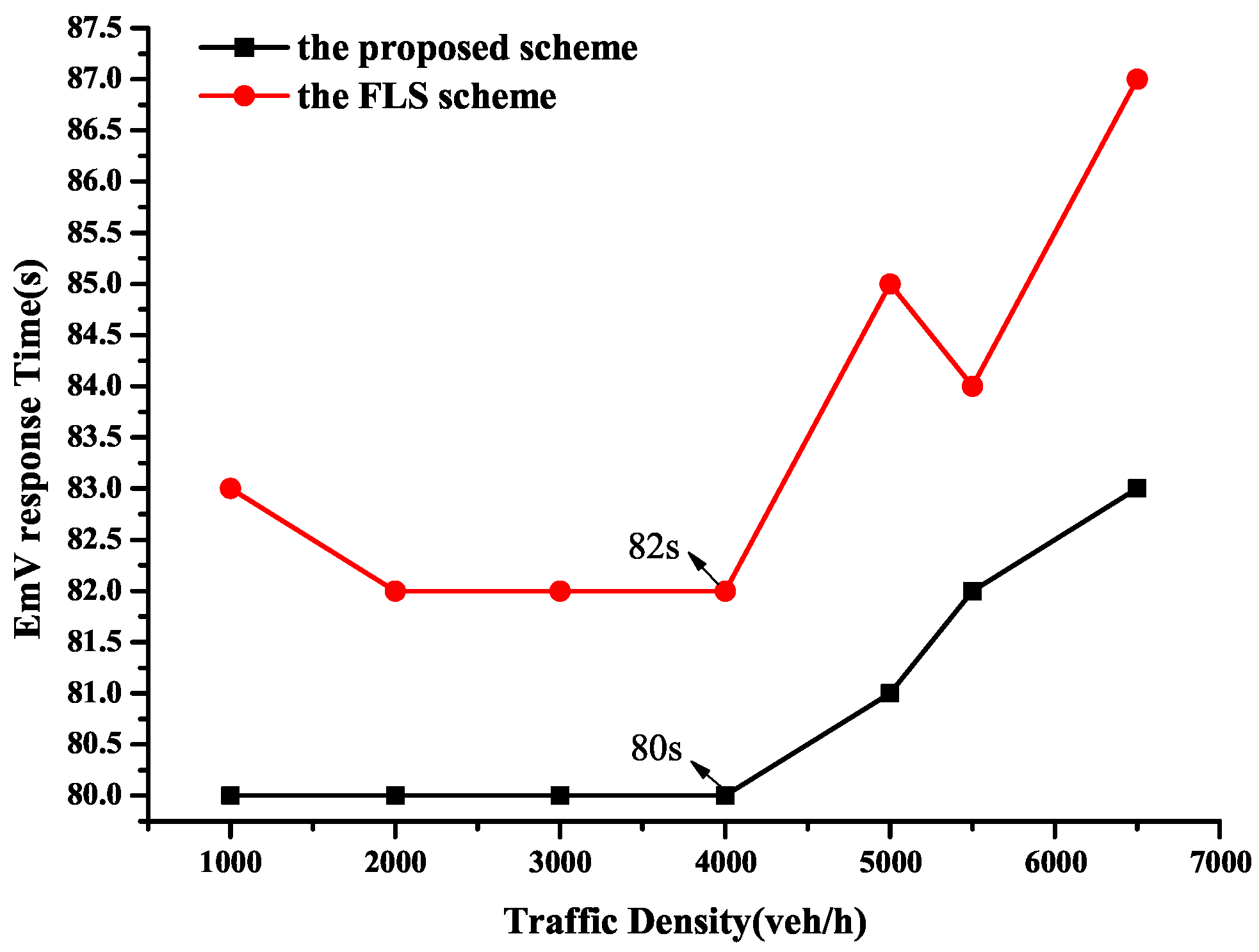

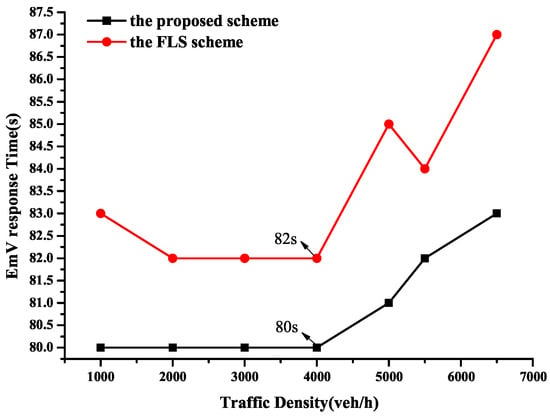

Response time refers to the total travel time from the start to the destination, and a shorter response time indicates higher travel efficiency.

As shown in Figure 16, when traffic density is below 4000 veh/h, the proposed scheme achieves a response time of approximately 80 s, which means the EmV travels the journey at its allowed maximum speed. By the FLS, the travel time is about 82 s. In comparison, at 4000 veh/h, the proposed scheme reduces the response time by 2.44% compared to the FLS scheme.

Figure 16.

Comparison of EmV’s response time.

When the traffic density exceeds 4000 veh/h, the FLS exhibits fluctuating increases in response time, whereas the proposed scheme maintains relative stability. This is because the FLS confines the EmV to a fixed lane, and the EmV has to wait for preceding OVs to yield, which results in prolonged waiting time. A detailed explanation of this mechanism is provided in the discussion of Figure 15 and is not repeated here.

Thus, the average speed and response time metrics demonstrate that the proposed CEVPDS scheme outperforms the FLS in terms of travel efficiency.

- (3)

- Speed variance of EmV

Speed variance is used to assess driving safety and comfort. Higher speed variations, especially significant speed fluctuations, indicate poor driving comfort. Frequent speed changes not only lead to discomfort but also increase potential accidents. This is particularly critical for EmVs, because frequent acceleration or deceleration may create an unstable environment that hinders medical staff from providing timely treatment to injured patients.

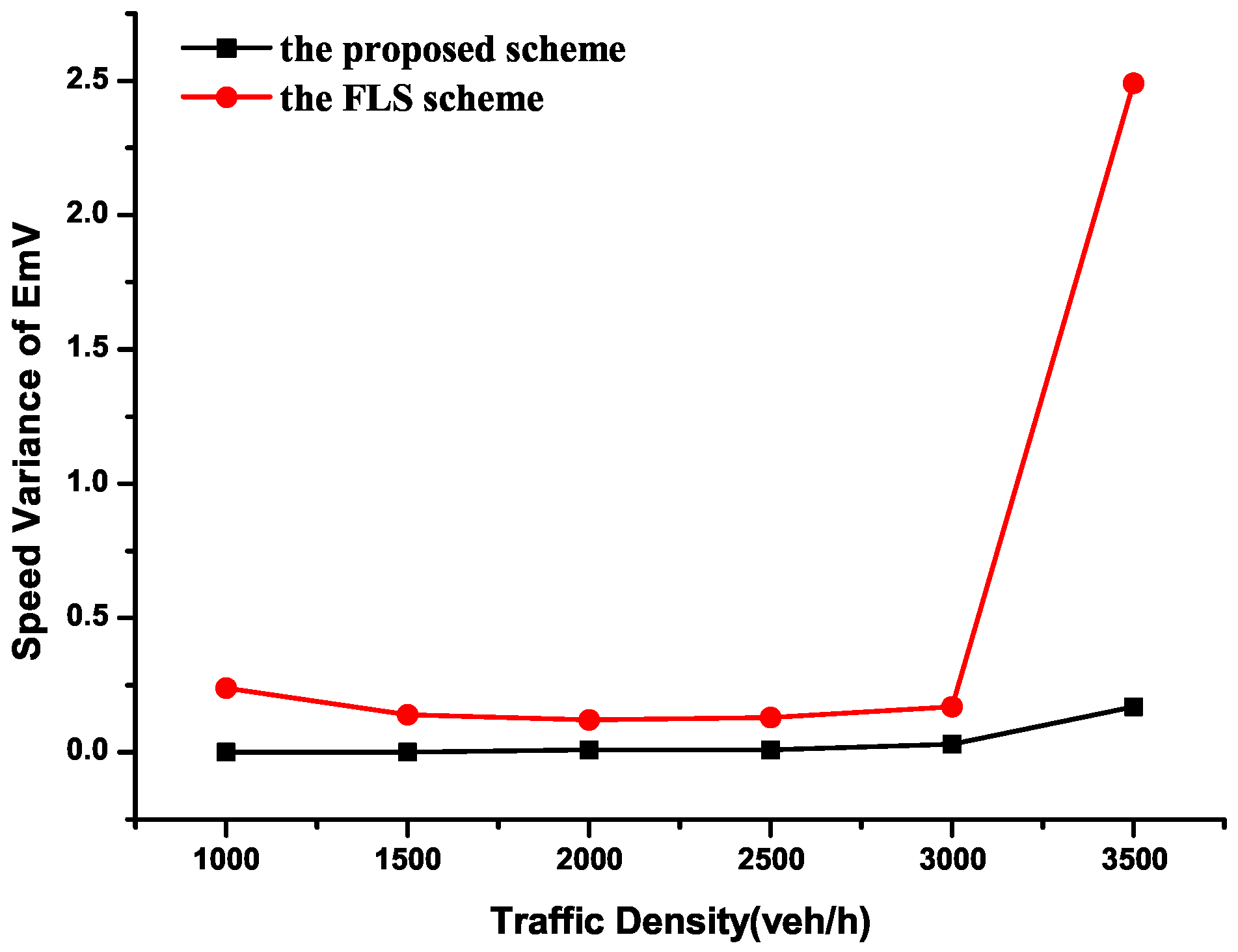

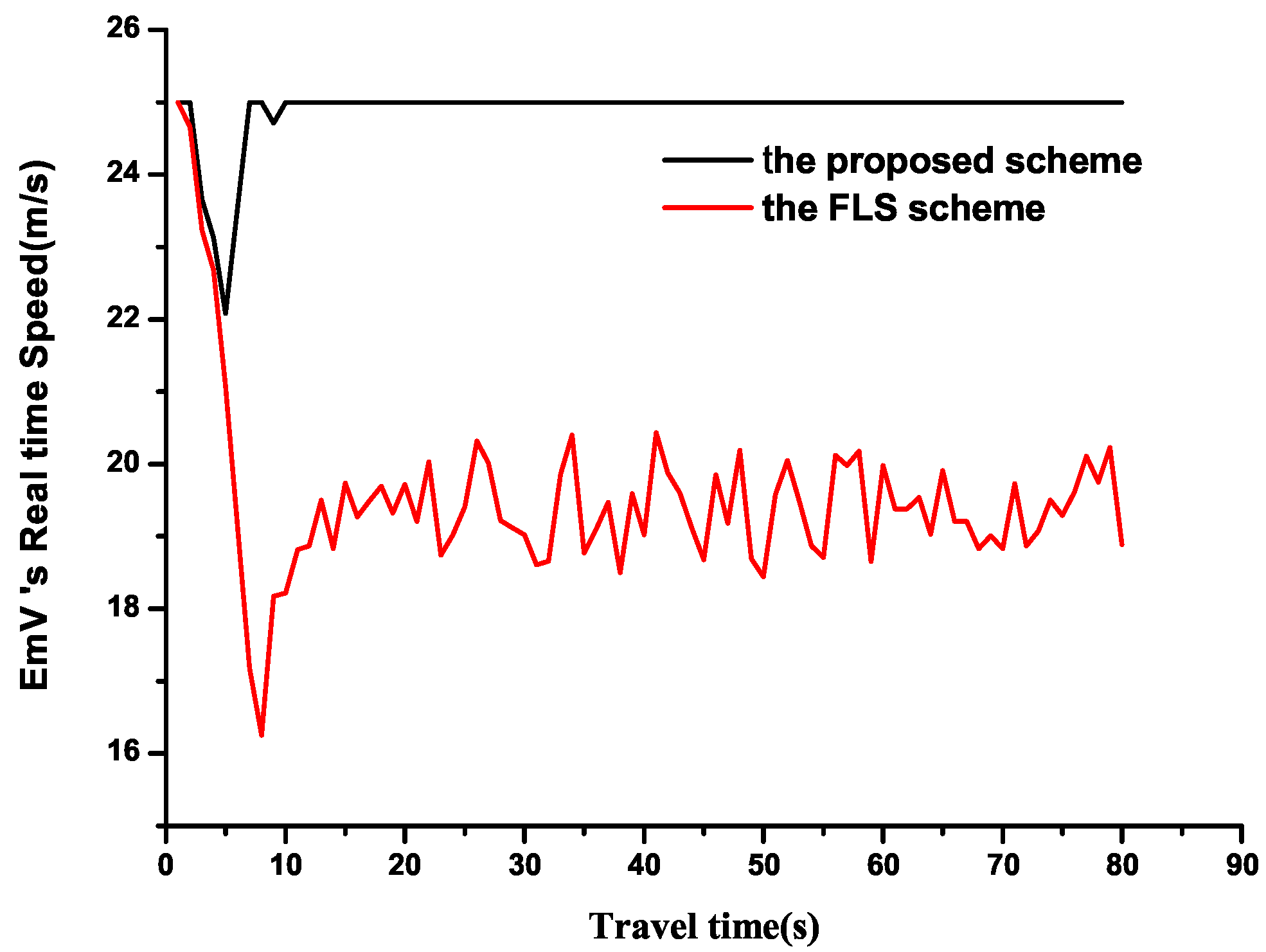

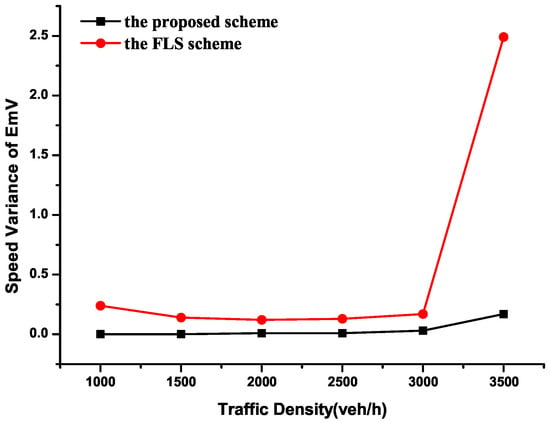

As shown in Figure 17, it depicts the speed variance of an EmV under different traffic densities. When traffic density is below 3000 veh/h, the proposed scheme achieves a near-zero speed variance, indicating minimal speed fluctuations and ensuring comfortable driving. When density exceeds 3000 veh/h, the proposed scheme maintains stable speed variance, just like keeping a constant speed, but the FLS scheme shows a sharp increase. This is because heavy traffic easily leads to congestion, and the EmV is confined to a fixed lane and must wait for preceding OVs to clear by the FLS. So the EmV keeps a stop–wait–go driving state that causes significant speed changes. In contrast, constant speed driving under the proposed scheme offers far better comfort than stop-and-go conditions under the FLs scheme.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the EmV speed variance.

To further demonstrate this, Figure 18 shows the EmV’s speed trends under two schemes at a density of 3500 veh/h with a 2 km road scenario. Both schemes experience sharp speed changes during the initial 5–10 s, the proposed scheme maintains a constant speed later, while the FLS continues to fluctuate due to a stop–wait–go driving state.

Figure 18.

EmV speed trends at 3500 veh/h.

- (4)

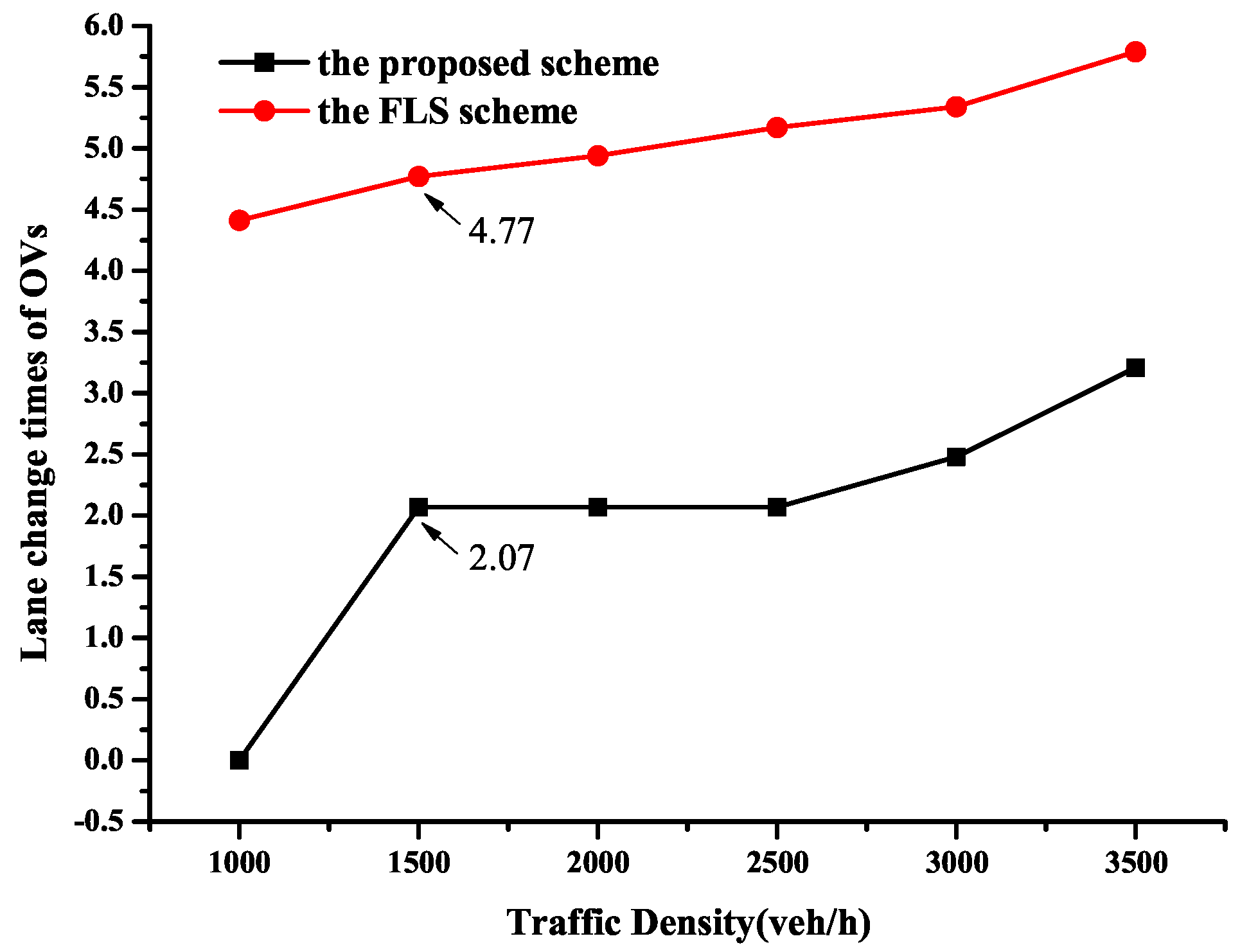

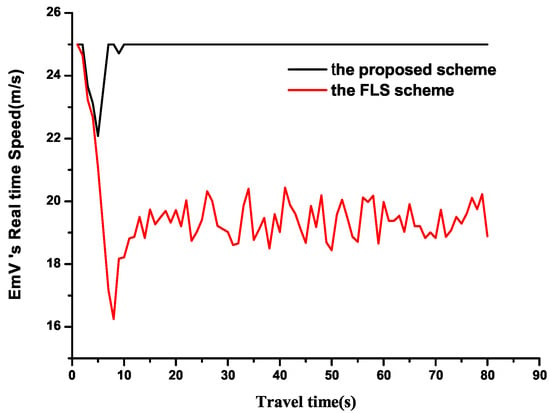

- Lane change frequency of OVs

The number of lane changes performed by OVs to yield to the EmV is a critical metric for evaluating the impact of EmV passage on surrounding vehicles. Frequent lane changes can disrupt adjacent vehicles, causing travel delays, reducing road capacity, and increasing traffic accident risks.

Figure 19 shows the trend of OVs’ lane change frequencies under two schemes with different traffic densities.The proposed CEVPDS scheme results in significantly fewer OV lane changes than the FLS, with the gap widening as traffic density increases. Specifically, when traffic density is 1000 veh/h, the lane changes in the proposed scheme are 0, while it is 4.5 in the FLS scheme. This indicates that our proposed scheme has no impacts on the OVs, and the OVs do not need to change lanes to give way to the EmV. In addition, when traffic density exceeds 1500 veh/h, the number of lane changes under our proposed scheme is 2.07, while in the FLS scheme, the number of lane changes is 4.77. The reason for such a better performance achieved by the proposed scheme can be summarized as follows: in the proposed scheme, the EmV has a pre-planned trajectory by the improved Dijkstra algorithm, and the OVs dynamically adjust and clear the lanes according to the pre-planned route. However, in the FLS scheme, the EmVs are fixed to a specific lane, and the OVs on that specific lane need to change to other lanes in advance to make way for the EmV to pass through.Therefore, the number of lane changes for OVs is greater than the proposed scheme.

Figure 19.

Comparison of the lane change times for OVs.

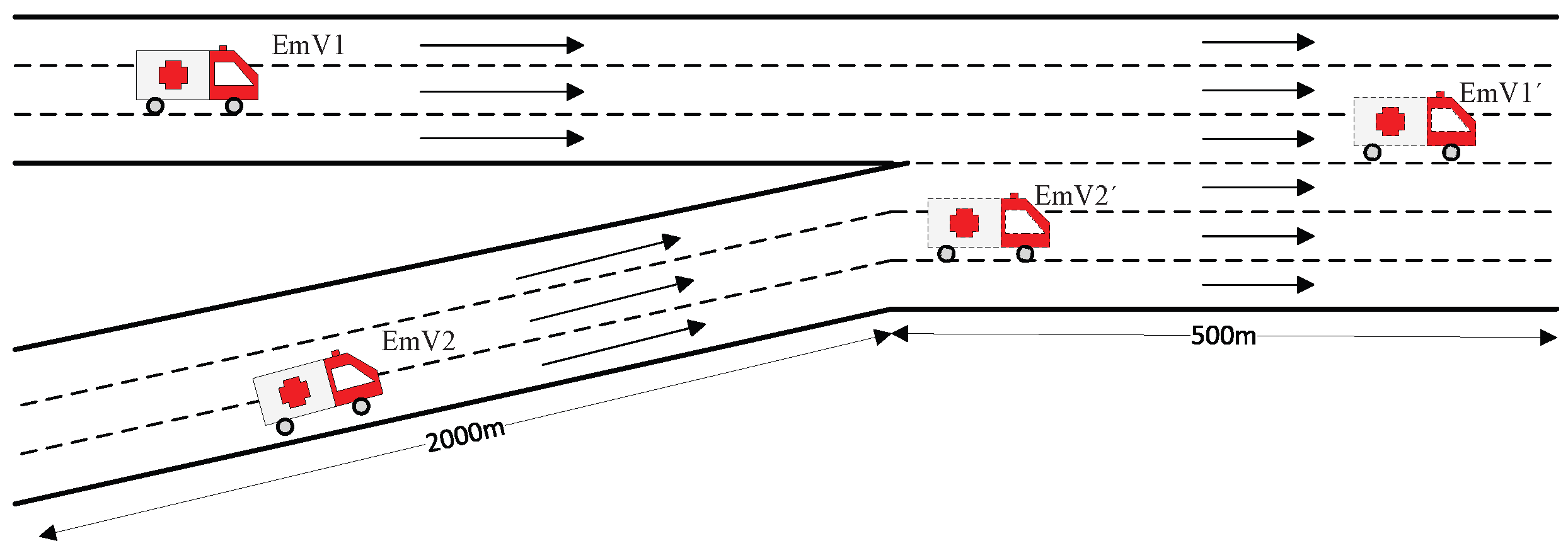

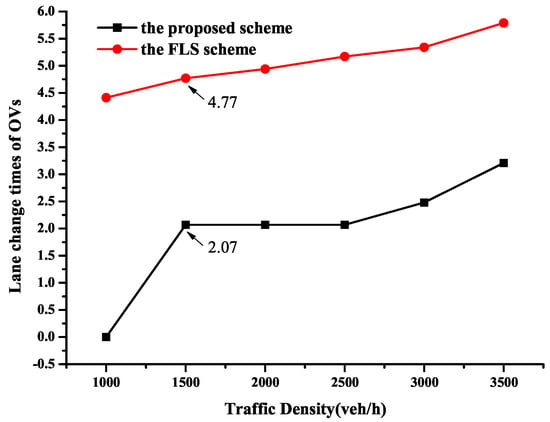

4.3. Performance Comparison of Two-EmVs Case

When multiple EmVs run on the road, inter-vehicle coordination is essential to minimize each EmV’s average travel time. Therefore, this involves collaboration between multiple EmVs and OVs. Here, we take two EmV cases to validate the superiority of the proposed scheme.

As presented in Figure 20, the simulation involves two EmVs merging onto the main road from two separate branches. If their arrival times at the main road differ significantly (e.g., by 10 min or more), the EmVs can be treated as independent entities with negligible mutual impact [37,38], allowing each to execute independent route planning. However, when arrival time differences are minimal, mutual interference becomes unavoidable, necessitating two alternative approaches. One approach is to maintain sequential travel in the same lane to minimize impacts on other OVs, and the second is the routing plan based on the averaged travel time of the two EmVs, balancing their individual estimated travel times.

Figure 20.

The road scene for two EmVs.

Compared with the FLS, the experimental results with two EmVs are presented in Table 3. From Table 3, in comparison to the FLS, the proposed scheme is able to reduce the frequency of lane changes and improve the EmV’s speed even in multiple-EmVs scenarios.

Table 3.

Results comparison for two EmVs.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, a cooperative emergency vehicle priority driving scheme (CEVPDS) is proposed to improve the traffic efficiency of EmVs on urban express roads in a V2X communication environment. By integrating road cell division and an improved Dijkstra algorithm, the proposed scheme is implemented in two steps. The first step involves designing the EmV trajectory in advance. The second step requires the OVs to dynamically yield to the EmV by lane changing in accordance with the pre-planned EmV trajectory established in the first step. Evaluated across two scenarios, simulation results demonstrate that compared with the FLS scheme, the proposed CEVPDS scheme outperforms much better performances. In the single-EmV case, the EmV can maintain a higher average speed, a shorter response time for driving, and more stable speed variations, while the OVs experience a mitigated impact from the EmV with lower lane changes times. For the two-Emvs case, the EmV’s response time shows a 2.44% reduction, and the total number of lane changes for all vehicles is decreased by 61.04%.

For future work, we will focus our research in three directions. First, we will fully account for the communication delay and data loss in V2X communication and analyze EmV and OV cooperative effects under imperfect communication scenarios. Second, we will consider or design some new AI- or learning-related methods for planning the EmV trajectories, and select new baseline schemes to evaluate the performances. Third, we will extend this work to multi-EmV cases under more complicated urban road scenarios with intersections or traffic lights and also validate this with empirical traffic datasets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.W. and M.Y.; Methodology: M.W. and M.Y.; Software: Y.W., M.W. and M.Y.; Validation: C.L., W.N., J.S. and H.W.; Formal Analysis: M.Y. and W.N.; Investigation: C.L., H.W.,W.N. and J.S.; Resources: C.L., J.S., W.N. and H.W. Writing—Original draft preparation: M.Y., M.W. and Y.W.; Writing—Review and editing: C.L., W.N. and H.W.; Funding acquisition: C.L. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education [grant number: 23YJAZH122], and Yangzhou University College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Fund Project [grant number: XCX20250416].

Data Availability Statement

All the data in the simulation was generated by SUMO V1.22.0 software, and the data has already contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI tool Deepseek V3.2 for language grammar checking and text polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEVPDS | Cooperative Emergency Vehicle Priority Driving Scheme |

| EmV | Emergency Vehicle |

| OV | Ordinary Vehicle |

| FLS | Fixed-Lane Strategy |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-everything |

References

- Li, J.; He, Q.; Wang, X.; Hawbani, A.; Yu, K.; Bi, Y.; Zhao, L. UAV-Assisted Microservice Mobile Edge Computing Architecture: Addressing Post-Disaster Emergency Medical Rescue. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2025, 74, 2635–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peelam, M.S.; Naren; Gera, M.; Chamola, V.; Zeadally, S. A Review on Emergency Vehicle Management for Intelligent Transportation Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 15229–15246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, L. Timing and Resource Analysis of Emergency Response Process Using Petri Nets. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 83361–83372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.-L.; Ge, W.-H.; Chen, J.-P.; Zhu, Y.-Q.; Huang, W. Prehospital index provides prognosis for hospitalized patients with acute Trauma. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, S.; Langari, R. Enhanced vehicle handling performance for an emergency lane changing controller in highway driving. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1–14 June 2017; pp. 334–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Ho, I.W.H.; Chung, E.; Fan, T. V2X and Deep Reinforcement Learning-Aided Mobility-Aware Lane Changing for Emergency Vehicle Preemption in Connected Autonomous Transport Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 7281–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yu, H.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, Z. A Collaborative Merging Strategy with Lane Changing in Multilane Freeway On-Ramp Area with V2X Network. Future Internet 2021, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. V2X-Based Autonomous Driving Control at Intersections and Pedestrian Collision Warning. Master’s Thesis, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, A.; Rito, P.; Luís, M.; Sargento, S. Mobility Sensing and V2X Communication for Emergency Services. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2023, 28, 1126–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaja, H.; Stoehr, J.M.; Beard, C. V2X-assisted emergency vehicle transit in VANETs. Simulation 2024, 100, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, F.; Landolfi, E.; Salzillo, G.; Massa, A.; D’Onghia, S.M.; Troiano, A. Implementation and Testing of V2I Communication Strategies for Emergency Vehicle Priority and Pedestrian Safety in Urban Environments. Sensors 2025, 25, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, W.; Yang, X. Development of degree-of-priority based control strategy for emergency vehicle preemption operation. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 2013, 283207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosita, Y.D.; Rosyida, E.E.; Rudiyanto, M.A. Implementation of Dijkstra algorithm and multi-criteria decision-making for optimal route distribution. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhou, S.; Xiao, L. Dynamic path planning based on improved ant colony algorithm in traffic congestion. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 180773–180783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Chen, Z.; Pei, M.; Ding, Y.; Qu, X.; Zhong, L. Multiple Emergency Vehicle Priority in a Connected Vehicle Environment: A Cooperative Method. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoun, G.J.; Murray, T.P.; Heaslip, K.; Chantem, T. Facilitating emergency response vehicles’ movement through a road segment in a connected vehicle environment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 3546–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Paruchuri, P. V2V communication for analysis of lane level dynamics for better EV traversal. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Gothenburg, Sweden, 19–22 June 2016; pp. 368–375. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Jia, H.; Wu, R.; Tian, J.; Wang, G. IoV-based mathematic model for platoon give way to emergency Vehicles Promptly. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 23, 16280–16289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, F. Agile Decision-Making and Safety-Critical Motion Planning for Emergency Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 13750–13766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikumar, K.S.; Prathiba, S.B.; Basheer, S.; Moorthy, R.S.; Dumka, A.; Rashid, M. V2X-Based Highly Reliable Warning System for Emergency Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, C.; Wu, W.; Qi, C. A cooperative lane change strategy for improving road safety through V2V communications. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 19–21 October 2022; pp. 1415–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Fan, C.; Wang, M.; Shen, J.; Liu, J. A Dynamic Shortest Travel Time Path Planning Algorithm with an Overtaking Function Based on VANET. Symmetry 2025, 17, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Lu, Z.; Wang, L.; Wen, X. Robust Autonomous Intersection Control Approach for Connected Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 124486–124502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, H.; Lai, K.K.; Zhang, R.; Iqbal, M.B. Scheduling Optimization of Mobile Emergency Vehicles Considering Dual Uncertainties. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Jiang, S.; Yan, G.; Shan, H.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zheng, X.; Song, J. Analysis of mixed vehicle traffic flow at signalized intersections based on the mixed traffic agent model of autonomous-manual driving connected vehicles. In Green Connected Automated Transportation and Safety: Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 775. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.E.; Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, L.-Y.; Zhang, H. Platoon control of connected vehicles from a networked control perspective: Literature review, component modeling, and controller synthesis. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayatian, M.; Mehrabian, M.; Shrivastava, A. RIM: Robust Intersection Management for Connected Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium (RTSS), Nashville, TN, USA, 11–14 December 2018; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lyamin, V.N.; Isachenkov, P. Modeling of V2V communications for C-ITS safety applications: A CPS perspective. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2018, 22, 1600–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Droździel, P.; Tarkowski, S.; Rybicka, I.; Wrona, R. Drivers’ reaction time research in the conditions in the real traffic. Open Eng. 2020, 10, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidestam, B.; Thorslund, B.; Selander, H.; Näsman, D.; Dahlman, J. In-Car Warnings of Emergency Vehicles Approaching: Effects on Car Drivers’ Propensity to Give Way. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Kaisar, S.; Khoda, M.E.; Naha, R.; Khoshkholghi, M.A.; Aiash, M. IoT-Based Emergency Vehicle Services in Intelligent Transportation System. Sensors 2023, 23, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyombo, M.E.; Liu, Y.K.; Mulenga, C.M.; Siamulonga, A.; Kabanda, M.C.; Shaba, P.; Xi, C.; Ayodeji, A. Optimal path planning in a real-world radioactive environment: A comparative study of A-star and Dijkstra algorithms. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 420, 113039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, P.A.; Behrisch, M.; Bieker-Walz, L.; Erdmann, J.; Flötteröd, Y.P.; Hilbrich, R.; Lücken, L.; Rummel, J.; Wagner, P.; Wießner, E. Microscopic Traffic Simulation using SUMO. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st international conference on intelligent transportation systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 2575–2582. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Jiang, R.; He, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, R.; Chen, X. Automated vehicle-involved traffic flow studies: A survey of assumptions, models, speculations, and perspectives. Transp. Res. Part C Emerging Technol. 2021, 127, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauß, S. Microscopic Modeling of Traffic Flow: Investigation of Collision Free Vehicle Dynamics; Hauptabteilung Mobilität und Systemtechnik des DLR Köln: Koeln, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.D. Collision free autonomous ground traffic: A model predictive control approach. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 4th International Conference on Cyber-Physical Systems, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 8–11 April 2013; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, W.; Xu, C. An Efficient On-Ramp Merging Strategy for Connected and Automated Vehicles in Multi-Lane Traffic. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 5056–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Feng, L. Priority of emergency vehicle dynamic right-of-way control method in networked environment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.