Abstract

Global change represents one of the most pressing threats to ecosystems, profoundly influencing habitats and redefining management and conservation priorities. Rising temperatures, altered precipitation regimes, invasive species and the increasing frequency of extreme events, such as prolonged droughts and wildfires, are modifying the composition, structure, and resilience of forests. Often, these changes result in habitat fragmentation, which isolates populations and diminishes their ability to adapt. This situation calls for an urgent reassessment of traditional protected area management practices. In response to climate change, it is essential to prioritize conservation strategies that focus on adaptation and maintaining biodiversity, while combating the spread of invasive species. For this reason, this study aims to analyze the impact of global changes on forest vegetation within protected areas, using Aspromonte National Park, a highly biodiverse region, as a case study. It evaluates the transformations in habitat cover and fragmentation over twenty years by comparing the 2001 vegetation map of Aspromonte National Park with the Map of Nature of the Calabria region, to quantify spatial and temporal habitat variations using QGIS 3.42.3 software. Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) and FRAGSTATS v4.2 were employed to evaluate habitat fragmentation. The results indicate that most forest habitats have experienced a slight increase in area over the past 20 years. However, the area occupied by Pinus nigra subsp. laricio forests (Habitat 42.65) has decreased significantly, most likely due to repeated fires in previous years. In conclusion, this study establishes a scientific foundation for guiding conservation policies in the protected area and promoting the resilience of native plant communities against global change. This is essential for ensuring their survival for future generations while mitigating both habitat fragmentation and the introduction and spread of non-native species.

1. Introduction

Climate change, along with habitat fragmentation and destruction, constitutes the primary driver of current threats to global ecosystems. These stressors act synergistically to trigger species migration and extinction, compromise ecosystem services, and alter structural integrity, ultimately culminating in widespread biodiversity loss [1,2].

Consequently, global change necessitates a shift in management and conservation priorities. Current literature [3,4] has extensively evaluated the impact of protected area (PA) management on ecological efficiency, with a specific focus on ecological connectivity and forest cover dynamics [5]. As essential pillars for maintaining biodiversity and habitat integrity, PAs are increasingly analyzed through a unified strategic lens [6,7]. This approach provides policymakers with a holistic overview of conservation trends, facilitating targeted interventions to mitigate climate-induced impacts and biodiversity loss [8,9]. Changes in land use can significantly impact ecosystem dynamics. Understanding these impacts is essential for the effective management and conservation of ecosystems [10,11].

Research into land-use change examines environmental challenges stemming from both natural processes, such as ecological succession, and various anthropogenic disturbances. The land-use change analysis, including deforestation, degradation [12], biodiversity loss [13], and urban expansion [14], enhances our understanding of environmental transformations and informs sustainable management frameworks.

When assessing temporal changes, it is important to consider that biodiversity comprises many components (e.g., wealth, relative abundance, composition and the presence of key species) which influence ecosystem characteristics in different ways [15]. These ongoing changes cause higher rates of species extinction [16] and a general loss of biodiversity [17,18]. To predict future threats, it is necessary to understand how the anthropogenic impact on habitats determines the new and different dynamics of species distribution.

Monitoring and assessing land-cover transitions and landscape configuration is fundamental for understanding management dynamics and their subsequent effects on natural ecosystems [19,20,21].

Diachronic analyses serve as robust tools for tracking structural shifts in the landscape [22,23], elucidating the underlying drivers of change, and evaluating the conservation status of critical habitats [24,25,26,27].

Currently, forest cover dynamics represent a pivotal area of research, given their profound influence on essential ecosystem services, such as climate regulation, hydrological cycles, biodiversity maintenance, and carbon sequestration [28,29,30]. Furthermore, habitat fragmentation induces significant ecological pressures, notably increased isolation and a reduction in core habitat area [31,32]. Within protected areas, addressing forest fragmentation remains a critical challenge, necessitating the development of novel methodologies for sustainable biodiversity management [33].

In forest ecosystems, fragmentation is often caused by inadequate forest management techniques and some socio-economic challenges [34] as well as by fires, pest attacks [35], agricultural conversion and urbanization [36].

Today, thanks to the combination of historical cartography and remote sensing data, it is possible to easily develop new solutions or environmental monitoring, land-use planning and the definition of conservation strategies [37].

Adopting a diachronic approach facilitates a comprehensive understanding of habitat dynamics, plant communities, and land-use transitions within protected areas. Such insights are critical for refining protection measures and meeting conservation targets. This study evaluates habitat distribution shifts within the Aspromonte National Park as a case study. By comparing habitat maps from 2001 and 2023, we analyze changes over a two-decade period also to assess the long-term effectiveness of local conservation policies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

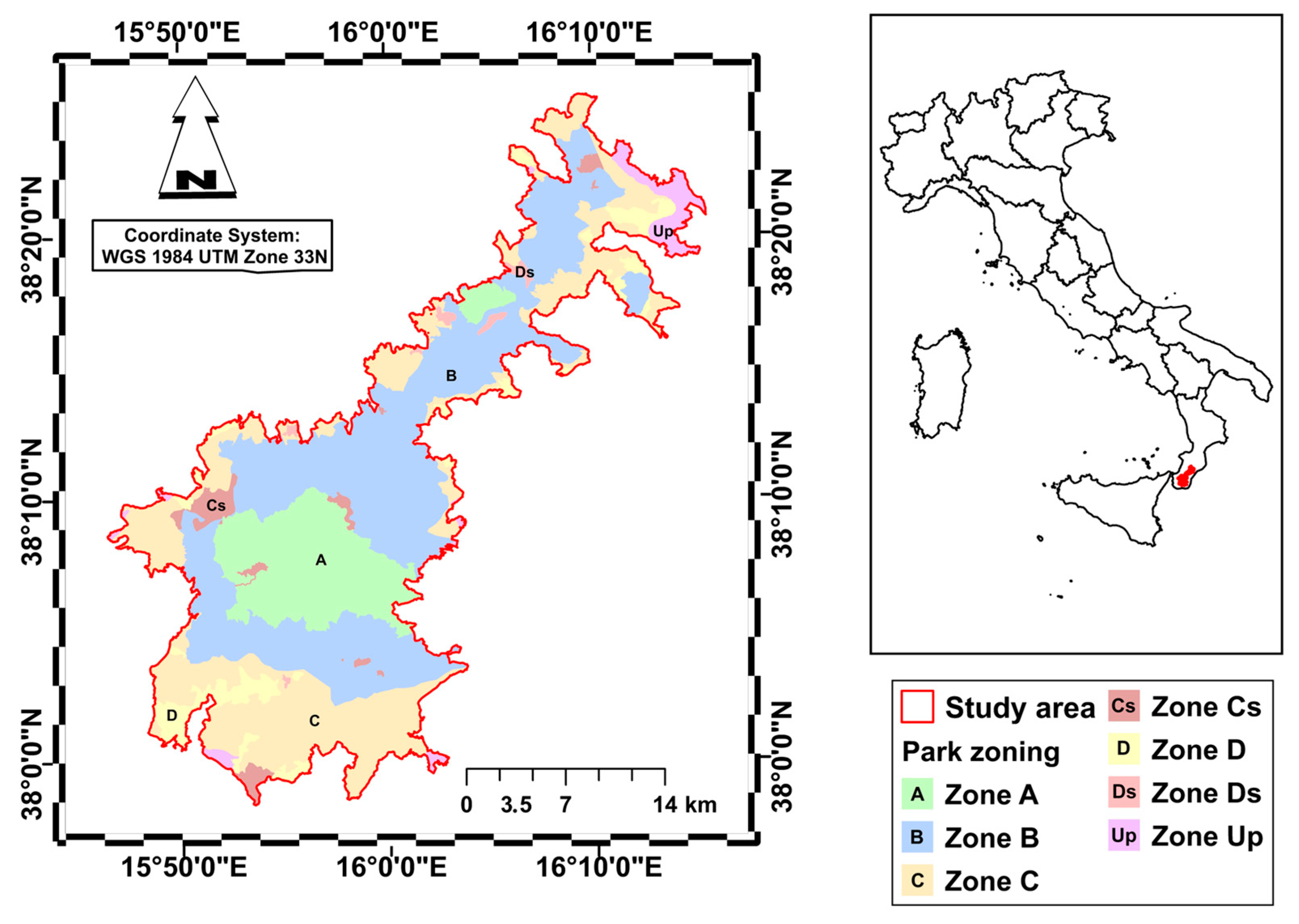

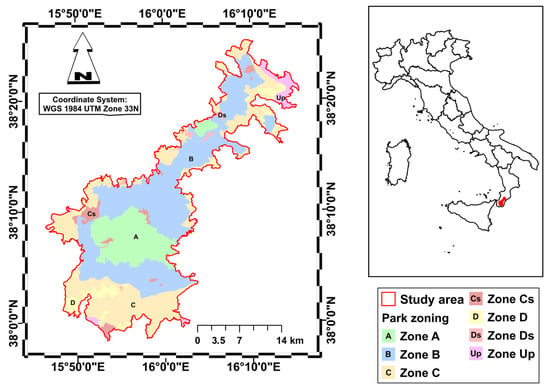

As a study area, we used Aspromonte National Park, established in 1994 and covering a total area of 64,647.46 hectares. The park is located in the far south of the Italian peninsula (Calabria Region, Italy) and its altitudes range from 100 m to 1956 m above sea level, with the highest peak being Monte Montalto (Figure 1). The mountain belt, characterized by a supra-temperate bioclimate, is dominated by extensive forests of Fagus sylvatica, while silver fir (Abies alba) generally plays a subordinate role within these forests. On the Ionian side, at altitudes between 1100 and 1500 m a.s.l., the steepest and sunnier areas are home to Pinus nigra subsp. laricio forests, which replace the beech forests. In localized xeric soil, mixed with beech trees, forests of Quercus petraea subsp. austrotyrrhenica can be found. The lower mountain belt, situated between 700 and 1000 m above sea level, has a sub-Mediterranean bioclimate and is characterized by scattered forests of Quercus pubescens or Quercus frainetto. These latter are predominantly found on the eastern slopes of the Aspromonte massif. In the hilly and sub-mountainous belt between 300 and 700 m above sea level, which has a meso-mediterranean bioclimate, there are widespread Quercus ilex forests. In the shadier and cooler valleys, these are replaced by ravine forests with Acer obtusatum, Ostrya carpinifolia and Corylus avellana. Quercus suber forests are mainly found on the north-eastern slopes at the outcrop of highly altered granite substrates. Secondary formations linked to the destruction of the original forest vegetation are widespread in hilly areas, such as steppe grasslands with Ampelodesmos mauritanicus and scrubland with Cytisus infestus and Erica arborea [38]. The protected area has planning tools (park plan and regulations) that have been in effect for approximately 20 years, which serve as territorial management tools required by Italian law for protected areas (Law 394/91) to define how to organize, use, protect and enhance the territory, establishing rules for land use, services, infrastructure and the conservation of habitat, flora and fauna, to balance environmental protection and sustainable development.

Figure 1.

Study area and zoning of the Aspromonte National Park. (Zone A: Strict Reserves; Zone B: General Oriented Reserves; Zone C: Partial Reserve; Zone D: Economic and Social Promotion Areas; Cs and Ds: Special Zones; Up: Unprotected Zones).

2.2. Diachronic Analysis

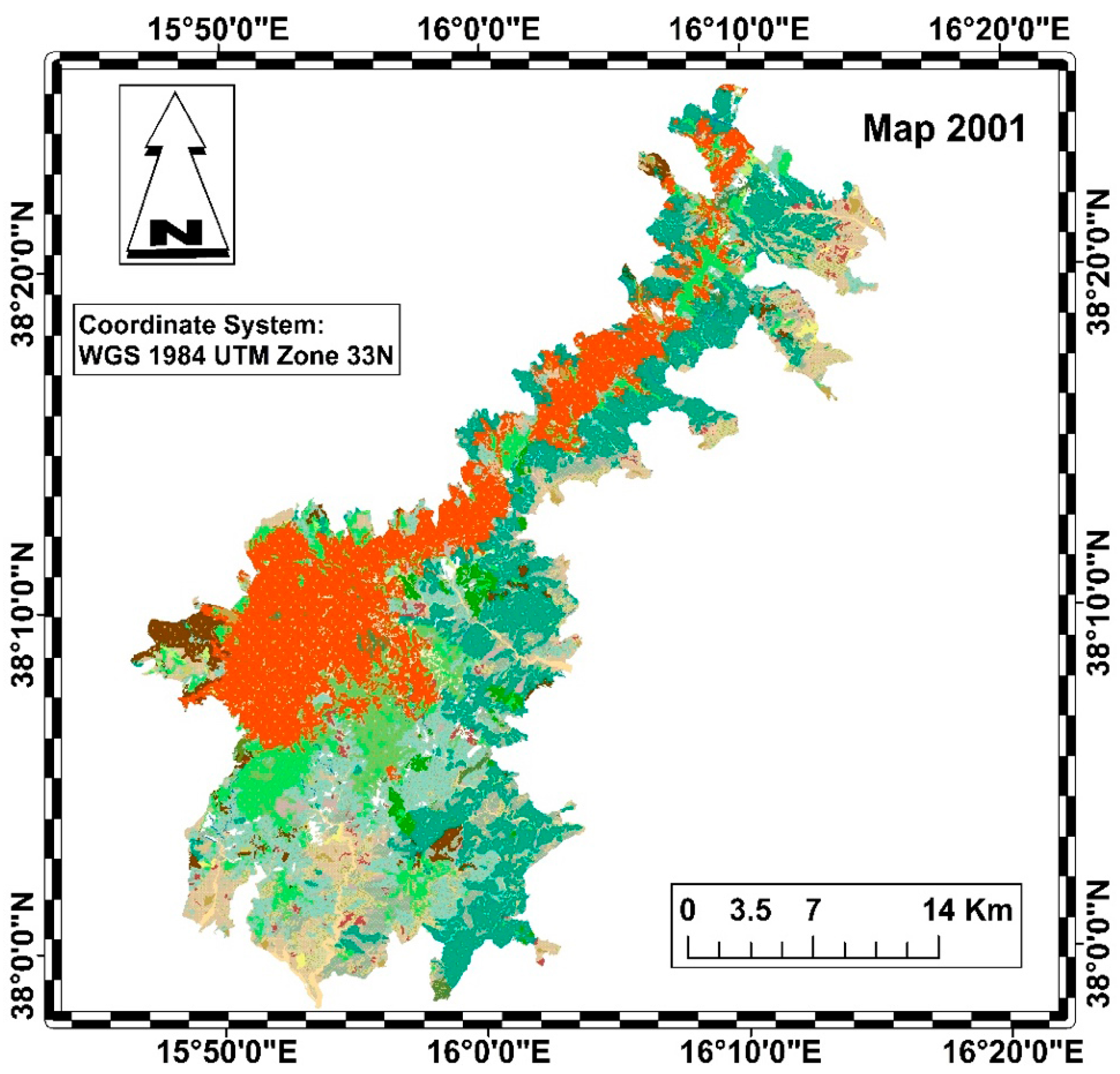

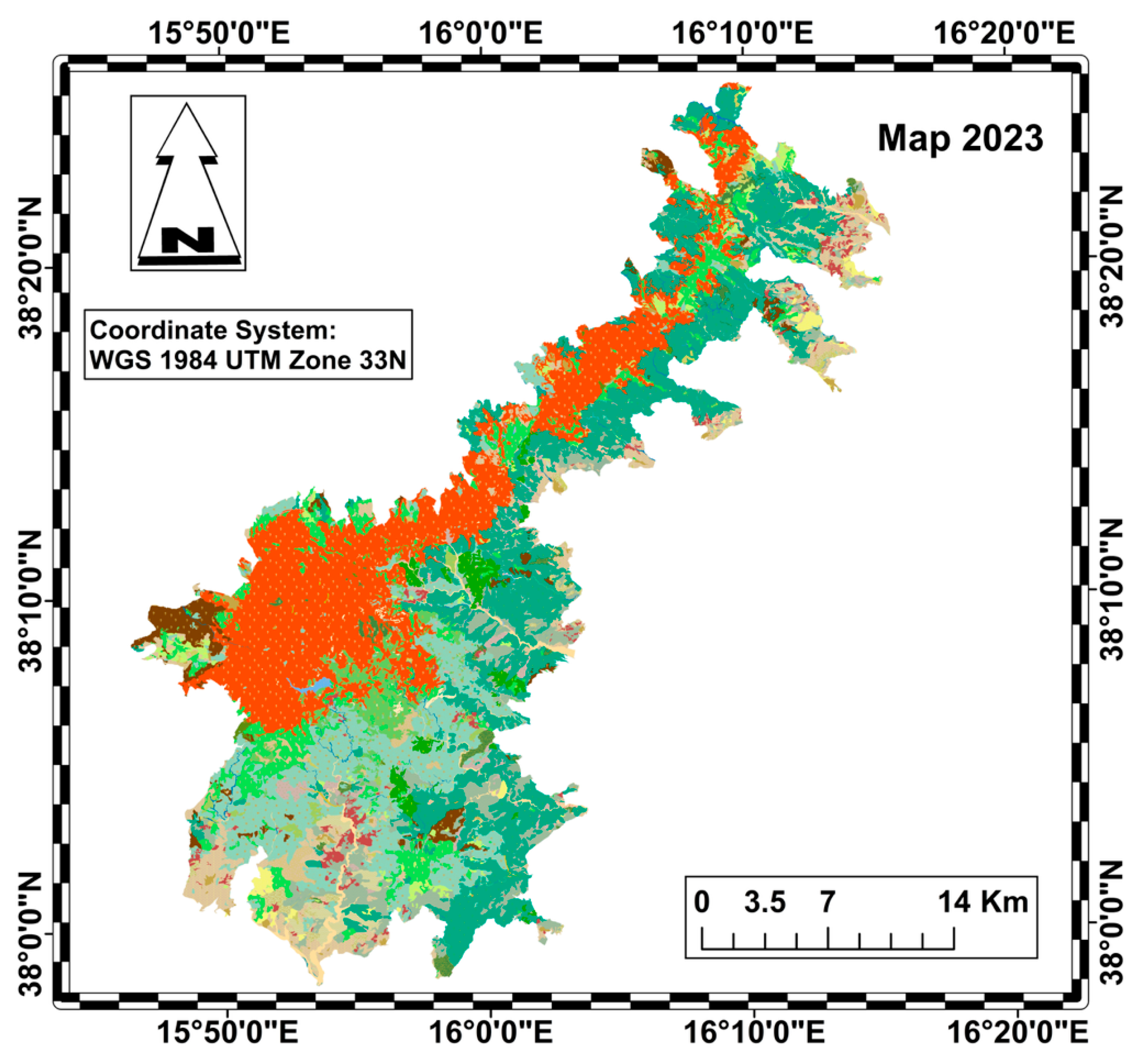

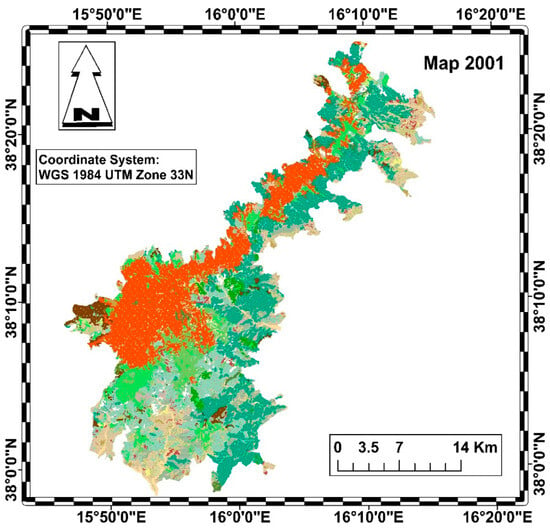

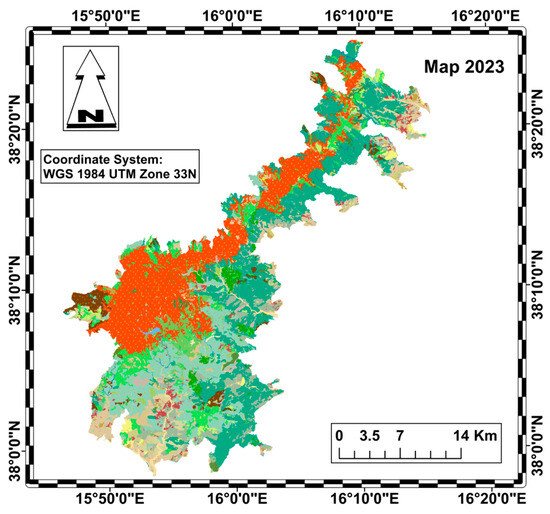

The diachronic analysis was carried out using QGIS, taking into account the 2001 vegetation map of Aspromonte National Park (Figure 2) and the 2023 Nature Map of Calabria (Figure 3) [39,40].

Figure 2.

Habitat map of the Aspromonte National Park in 2001 (legend in Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Habitat map of the Aspromonte National Park in 2023 (legend in Figure 4).

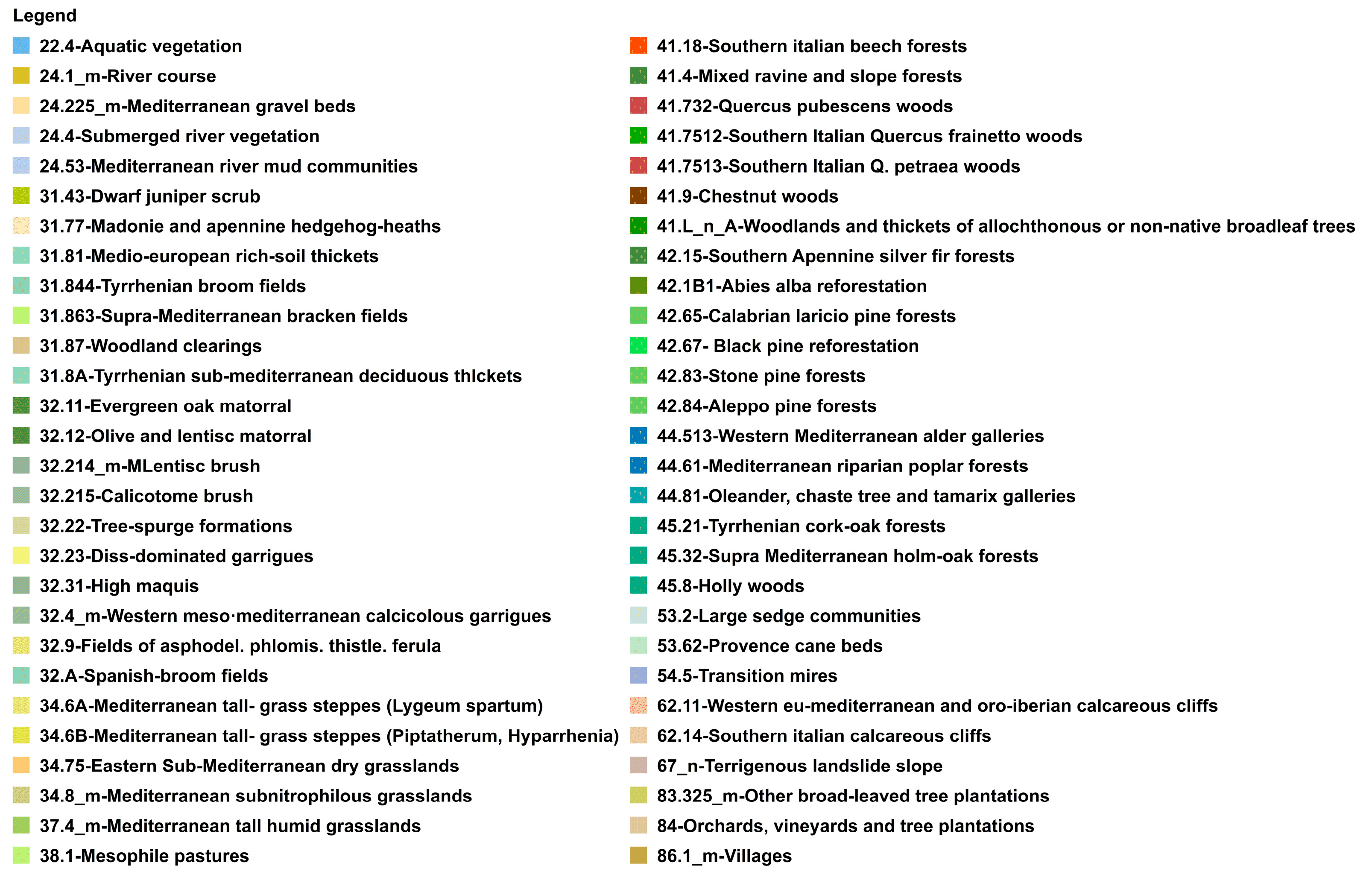

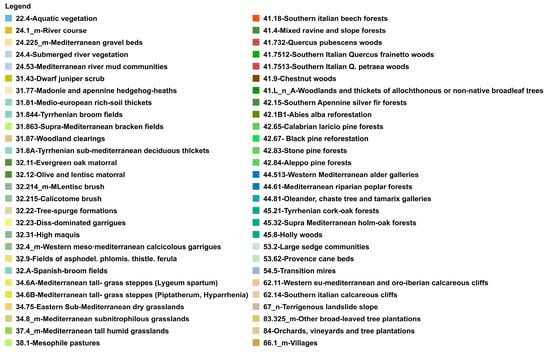

Both maps were standardized according to the Nature Map legend, based on the CORINE biotope classification system (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Legend of Nature Map habitats.

To this end, the vegetation units shown on the 2001 map were reclassified. To verify the accuracy of the polygonal units and their correspondence with the habitats mapped in 2001 and 2023, aerial photographs and satellite images from the reference year were imported into the GIS.

The analysis was performed at a scale of 1:25,000, consistent with the level of detail of the source data and validation tools using the WGS84/UTM Zone 33N (EPSG:32633) coordinate reference system.

2.3. Habitat Change Analysis

Changes to the territory were highlighted by comparing the areas occupied by various habitat types in 2001 and 2023. The vector datasets were converted into raster format with a spatial resolution of 10 m. Each habitat type was assigned a unique numerical code to ensure consistency between the two periods. Changes were quantified using raster-based overlap analysis (Figure 2 and Figure 3, Supplementary Materials Table S1). Using the ‘Tabulate Area’ tool in ArcMap 10.7.1, a transition matrix (42 × 54) was generated where the rows represent the initial state (2001) and the columns represent the final state (2023) (see Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials). The data were processed in R Core Team 4.4.3 [41] to quantify the contraction or expansion of habitat area by analysis of:

- -

- Persistence: the area of a specific category that remained unchanged between 2001 and 2023 (diagonal elements of the transition matrix);

- -

- Gross loss: area of the category in 2001 minus its persistence.

- -

- Gross gain: area of the category in 2023 minus its persistence.

- -

- Net change: the difference between total gains and total losses, indicating whether a category has expanded or contracted.

- -

- Transition areas: for each flow, the area (in hectares) that underwent a change was identified and reported.

To ensure the robustness of the transition analysis, changes greater than 3 hectares were considered to minimize cartographic noise when overlaying the 2001 and 2023 maps. This methodology ensures that the quantification of transformations accurately reflects the actual dynamics of the landscape, without taking into account polygon tracing errors.

2.4. Landscape Composition Change Analysis

The fragmentation was analyzed at class level for both 2001 and 2023 using FRAGSTATS software (version 4.2.1) [42,43]. This software was created to calculate a wide range of landscape parameters to understand fragmentation [44,45,46]. To assess fragmentation, this study considered several categories of landscape parameters to quantify the configuration and composition of forest habitats (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition and configuration metrics used in this study.

The analysis of landscape metrics to assess habitat diversity and its variation between 2001 and 2023 took into consideration the metrics reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Landscape diversity metrics used in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Habitat Change

The comparison between the geodatabases relating to the 2023 and 2001 habitat map made it possible to process and quantify the landscape dynamics in the Aspromonte National Park.

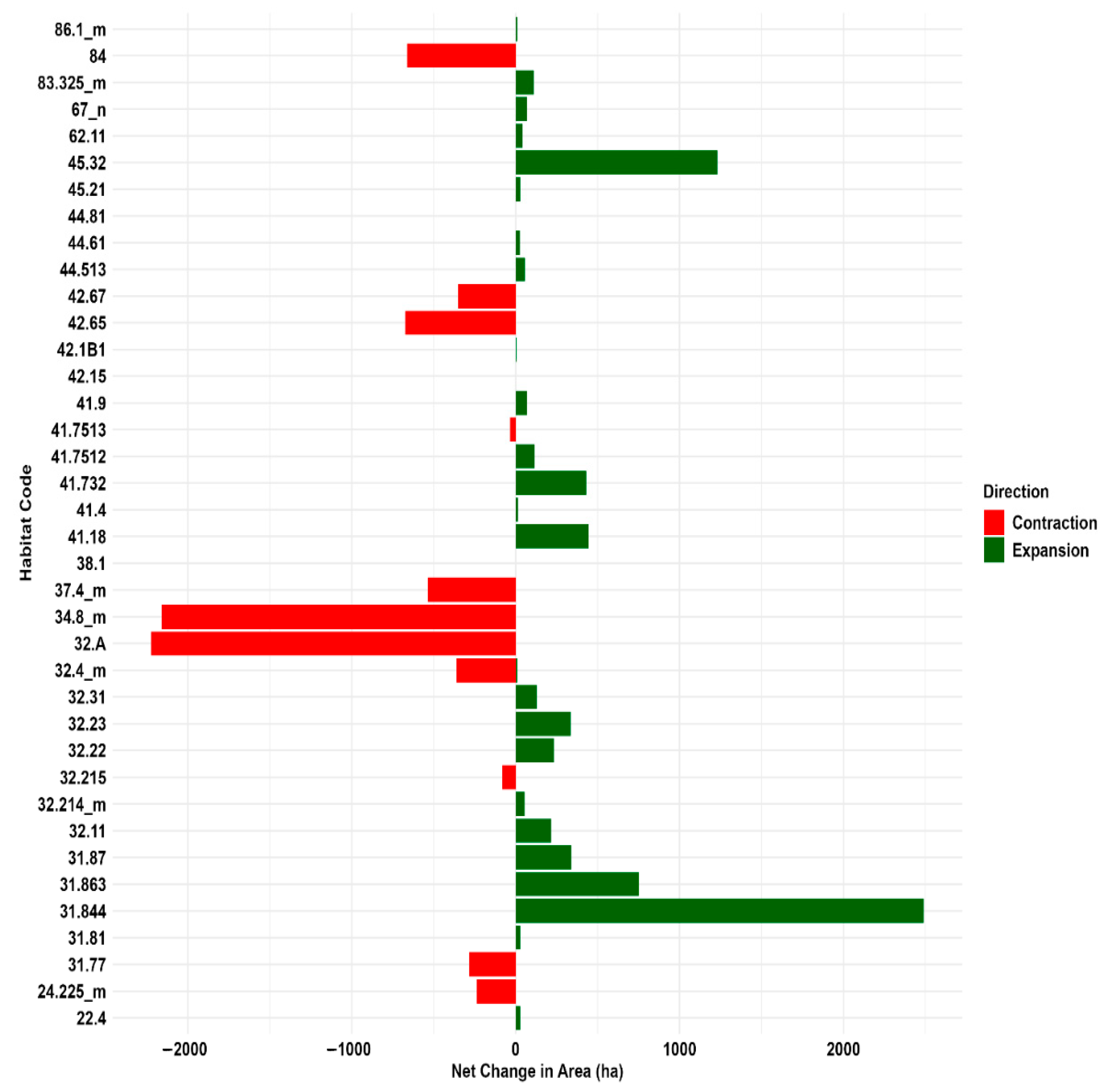

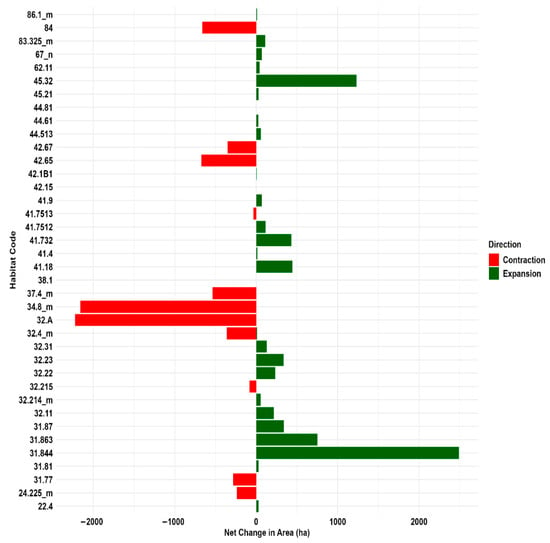

Between 2001 and 2023, habitat dynamics in the Aspromonte National Park (Figure 5; Table S3) indicate an increase in forest habitats, particularly 45.32 “Supra-Mediterranean holm oak forests” (+45.3%) and 41.18 “Southern Italian beech forests” (+41.2%). Conversely, “Calabrian laricio pine forests” (42.65) and “Southern Italian Quercus petraea woods” (41.7513) suffered a significant decline (−43% and −40%, respectively). As a result of the expansion of forests, herbaceous habitats showed a marked decrease, particularly “Mediterranean sub-nitrophilous grasslands” (34.8_m), decreased by 77.2%, followed by “Madonie and Apennine hedgehog-heaths” (31.77), decreased by 67%, and “Mediterranean tall humid grasslands” (37.4_m), less 61.6%.

Figure 5.

Habitat area extent changes (ha) in Aspromonte National Park: 2001 vs. 2023 contraction and expansion trends. The labels on the axes refer to habitat types (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

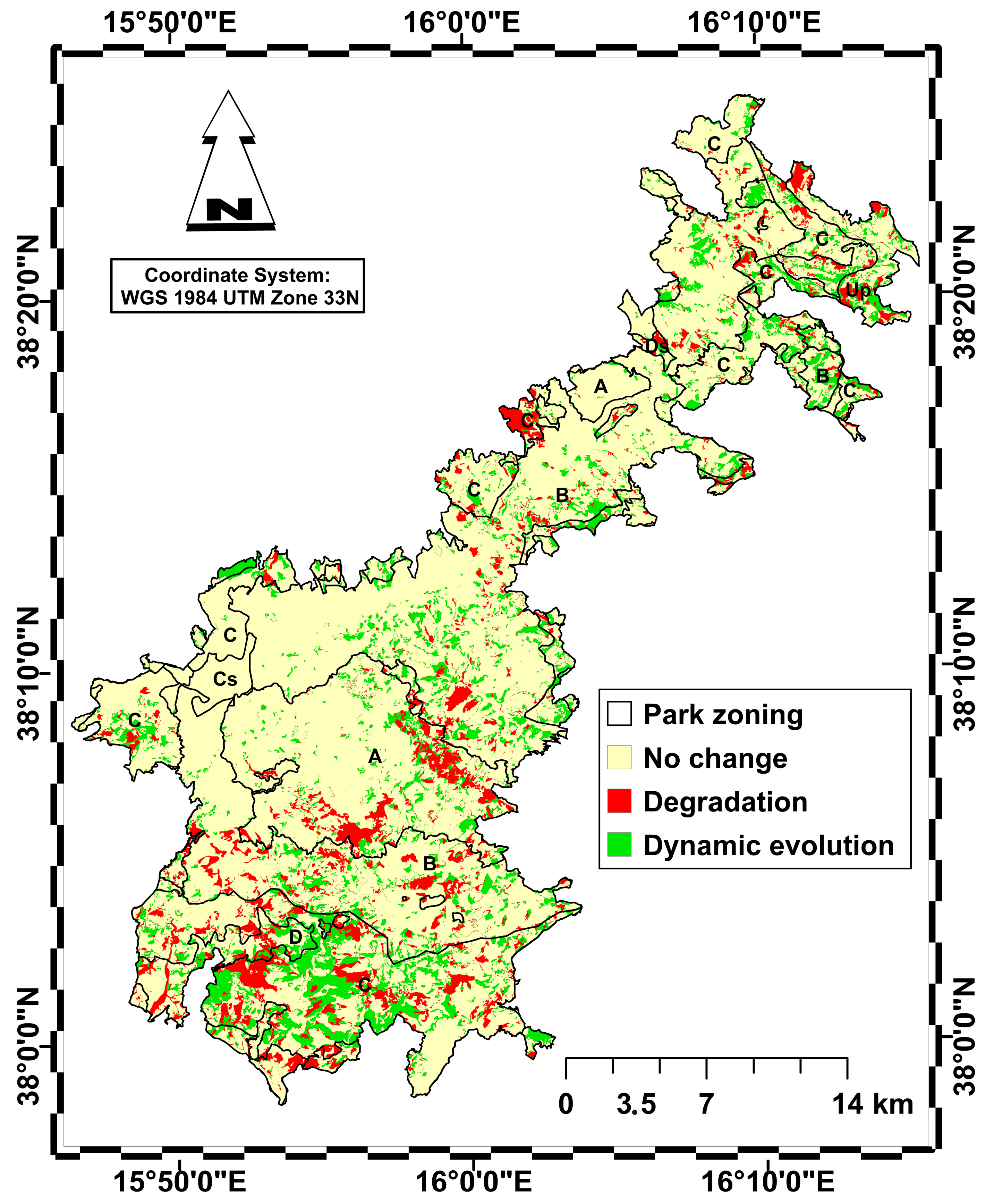

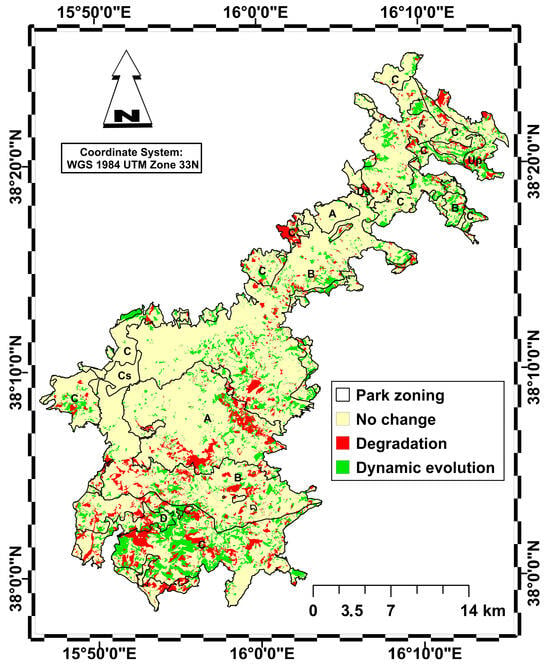

Table 3 and Figure 6 show, in percentage terms, how much the habitat area within the Park’s zoning (Zone A: Strict Reserves; Zone B: General Oriented Reserves; Zone C: Partial Reserve; Zone D: Economic and Social Promotion Areas; Cs and Ds: Special Zones; Up: Unprotected Zones) has changed between 2001 and 2023.

Table 3.

Percentage values of changes in habitat area in the zone of the protected area.

Figure 6.

Map of habitat area change between 2001 and 2023 distinguishing between no change (yellow), habitat degradation (red) and habitat dynamic evolution towards more complex and stable types (green). Park zoning is represented as in Figure 1.

It should be noted that 77% of the area has not undergone any changes, remaining stable in both zones, while 9.3% of the habitat area has undergone a decline with the establishment of regression plant communities, affecting 3.6% of zone C, 2.5% of zone B and 1.5% of zone A, with smaller areas affected in the other zones. Finally, 13.6% of the habitat area has seen a gradual dynamic evolution towards more advanced stages of vegetation, with 5.8% affecting zone C, 4.5% affecting zone B and only 1.1% affecting zone A.

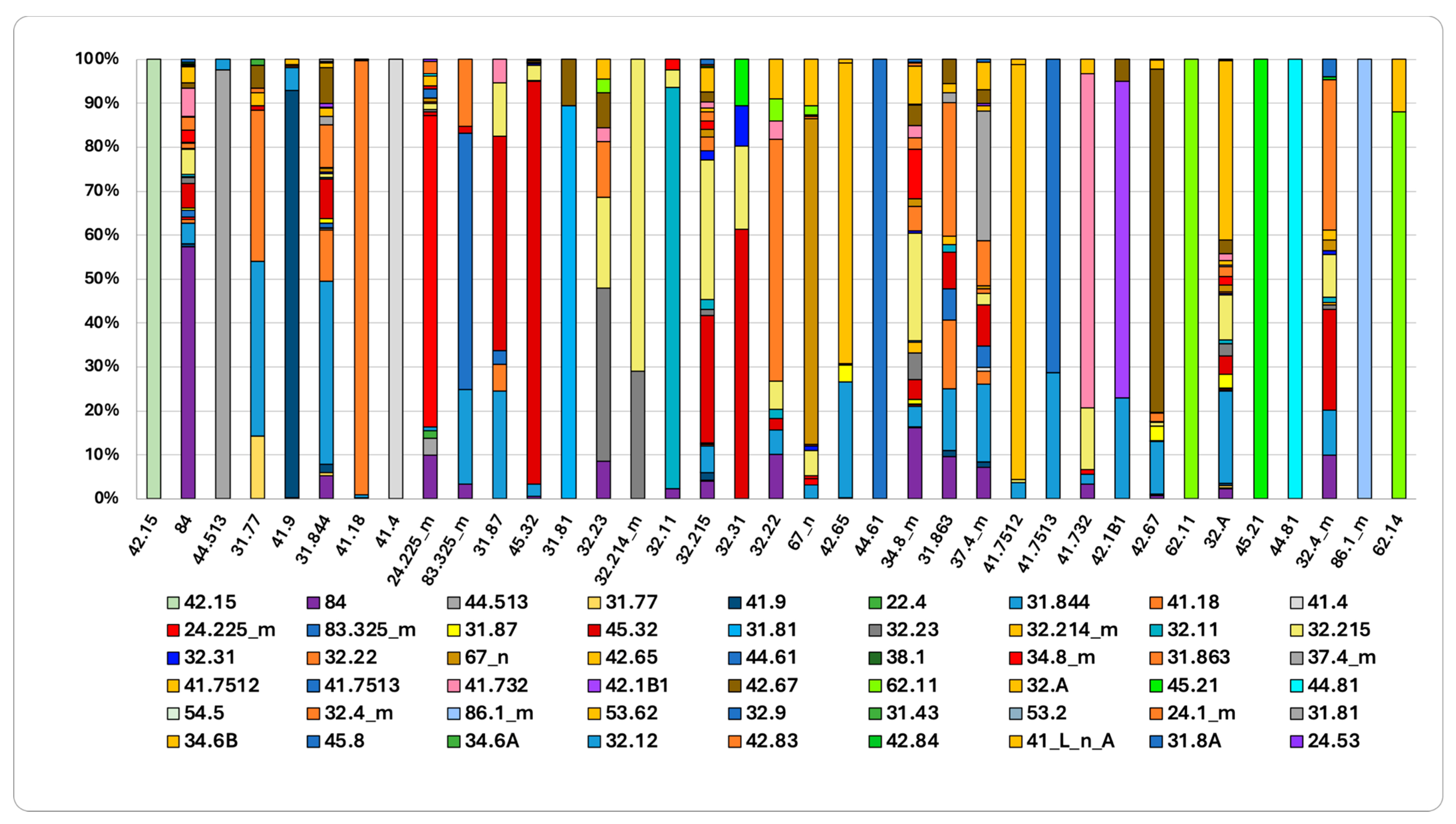

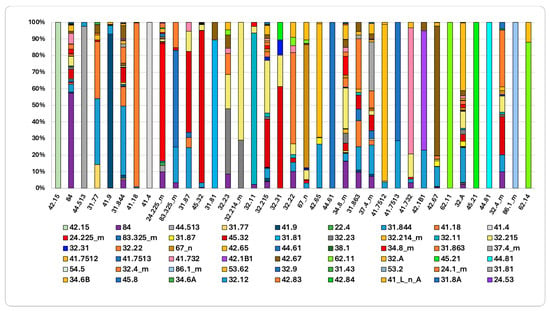

The directional flows and stability of the various habitats are shown in the graphs in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Figure 7 shows the habitat change between 2001 and 2023. Habitats characterized by greater persistence, indicating high stability, include “Southern Italian beech forests” (41.18), “Southern Apennine silver fir forests” (42.15), “Mixed ravine and slope forests” (41.4), and “Supra-Mediterranean holm oak forests” (45.32). Conversely, “Calabrian black pine forests” (42.65) have shrunk by 30%: 26% of their area was replaced by “Tyrrhenian broom fields” (31.844) and 4% by “Woodland clearings” (31.87). The contraction of the “Calabrian black pine forests” habitat is primarily driven by shrub replacement following fire disturbances. Similarly, “Southern Italian Q. petraea forests” (41.7513), which decreased, are being replaced by Tyrrhenian broom fields (31.844), suggesting structural regression triggered by fire events. “Madonie and Apennine hedgehog-heaths” (31.77) have undergone an even greater contraction: 34% of their area was replaced by “Southern Italian beech forests”, indicating natural ecological succession; meanwhile, 40% was replaced by Tyrrhenian broom fields (31.844), indicating disturbance regimes. Finally, the analysis shows that “Mediterranean tall humid grasslands” (37.4_m) have contracted: 18% of their area was replaced by “Tyrrhenian broom fields” (31.844), 10% by “Supra-Mediterranean bracken fields (31.863), and 3% by “Southern Italian beech forests” (41.18). Similarly, a significant portion of the “Mediterranean subnitrophilous grasslands” (34.8_m) habitat has been replaced: 25% by “Calicotome brush shrub formations” (32.215), 9% by “Spanish broom fields” (32.A), and 5% by “Tree spurge formations” (32.22).

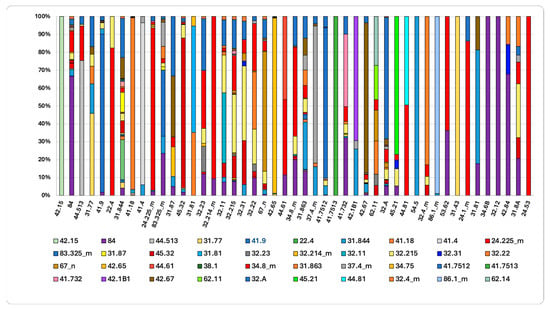

Figure 7.

Initial habitat status and trajectories of change (2001–2023). The columns represent different habitat types. For more detail, see Supplementary Material Table S1 for habitat name and Table S2 for the transition matrix.

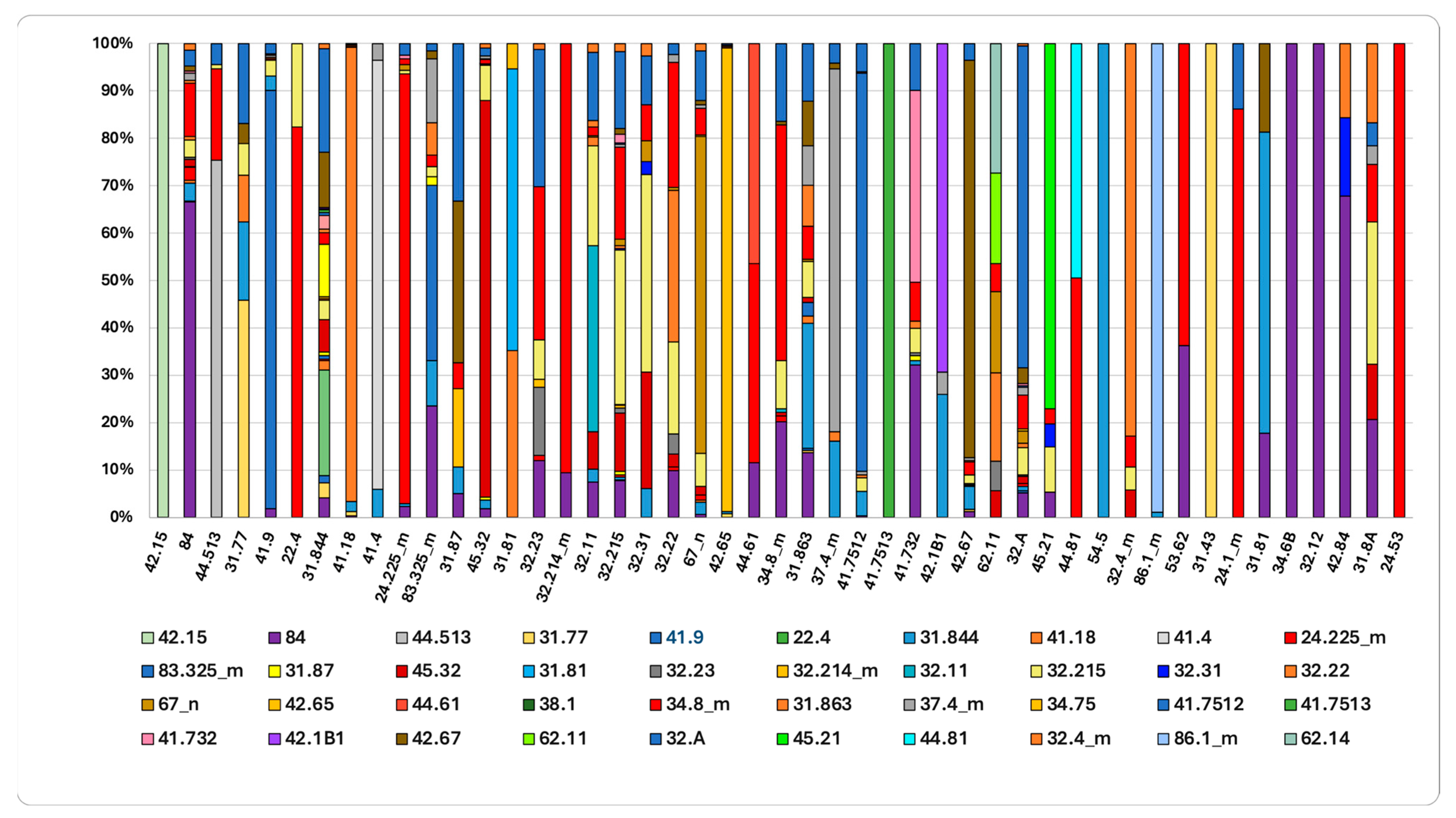

Figure 8.

The final habitat status in 2023 and the contribution of source flows since 2001 are shown. Complete habitat name in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials and Table S2 for the transition matrix.

The final state of habitat in 2023, compared to 2001 (Figure 8), reveals that 42% and 19% of the area currently occupied by “Mediterranean riparian poplar forests” (44.61) and “Western Mediterranean alder galleries” (44.513) originated from “Mediterranean gravel beds (24.225). This indicates a marked ecological succession toward more mature and stable forest formations. Supra-Mediterranean holm-oak forests (45.32) demonstrate high stability, with expansion driven by the colonization of areas previously occupied by “Calicotome brush” (32.215) (7%), “Spanish-broom fields” (32.A) (2%), and “Tyrrhenian broom fields” (31.844) (2%).

The increase in “Quercus pubescens woods” (41.743) is primarily due to the colonization of open and semi-natural areas following the abandonment of rural mosaics, including “Orchards, vineyards and tree plantations” (84), which account for 32% of this increase. Additionally, expansion of “Quercus pubescens woods” occurred over “Spanish-broom fields” (32.A) (10%), “Mediterranean subnitrophilous grasslands” (34.8_m) (8%), and “Calicotome brush” (32.215) (5%). These data confirm a landscape-wide dynamic process, characterized by forest expansion following the cessation of agricultural activities. This dynamic is further evidenced by the expansion of “Evergreen oak matorral” (32.11), which increased by 21% through the colonization of less evolved formations as “Calicotome brush” (32.215) and former agricultural land “Orchards, vineyards and tree plantations” (7%).

3.2. Analysis of Composition Metrics and Configuration of Individual Types

The fragmentation analysis took several parameters into account. Table 4 shows the calculated metric values for each forest habitat in Aspromonte National Park in 2001 and 2023.

Table 4.

Values of forest habitat composition metrics in 2001 and 2023. (PLAND—Percentage of Landscape; NP—Number of Patches; PD—Patch Density; LPI—Largest Patch Index; LSI—Landscape Shape Index; AREA_MN—Mean Patch Area).

The results indicate a minor change in the landscape’s configuration from 2001 to 2023. The Percentage of Landscape (PLAND) value increased significantly for almost all forest habitats compared to 2001. ‘Quercus pubescens woods’ (41.732), ‘supra-Mediterranean holm oak forests’ (45.32) and ‘Southern Italian beech forests’ (41.18) underwent significant expansion. Conversely, ‘Calabrian laricio pine forests’ (42.65%) and ‘Southern Italian Q. petraea woods’ (41.75%) shrank significantly.

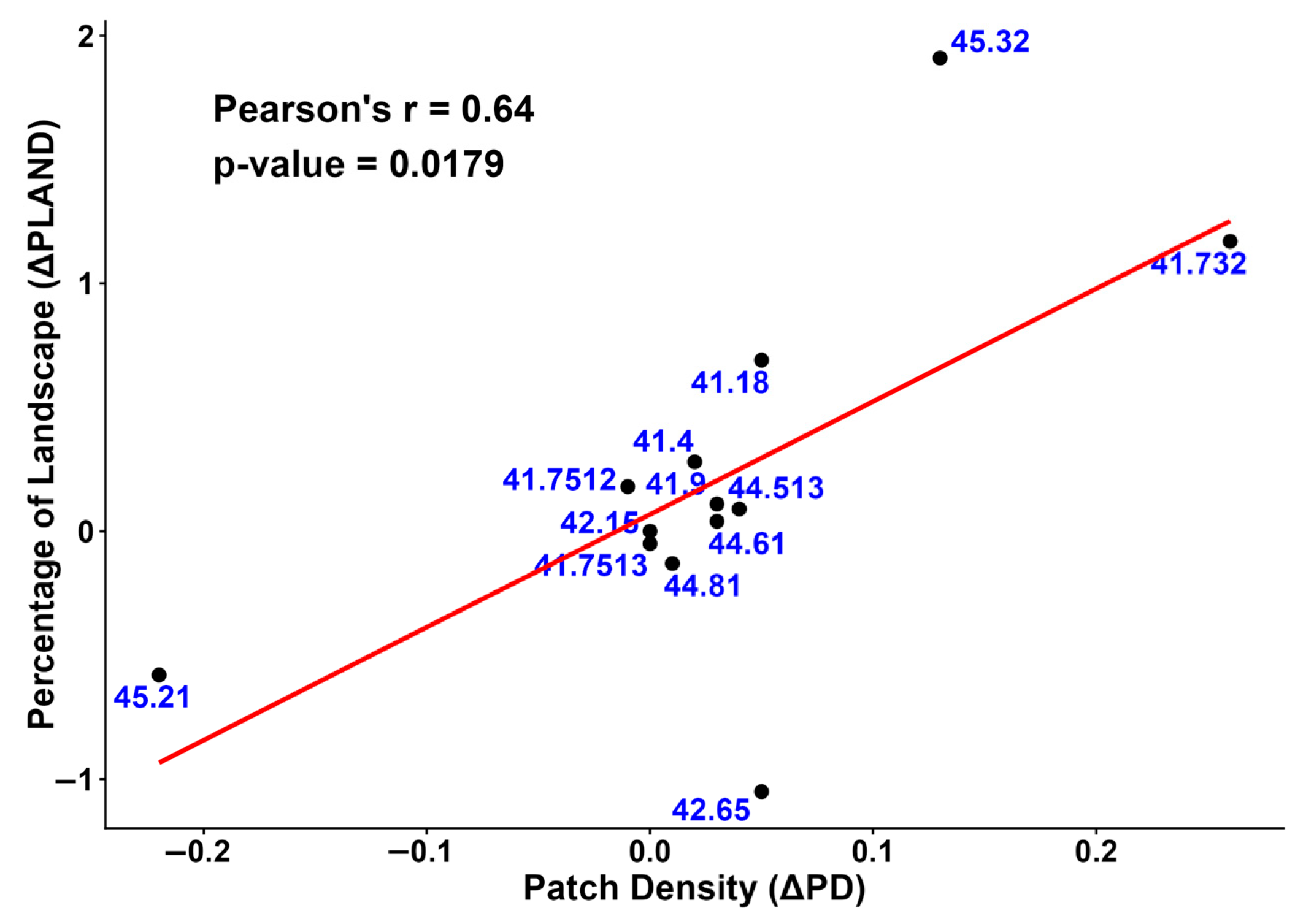

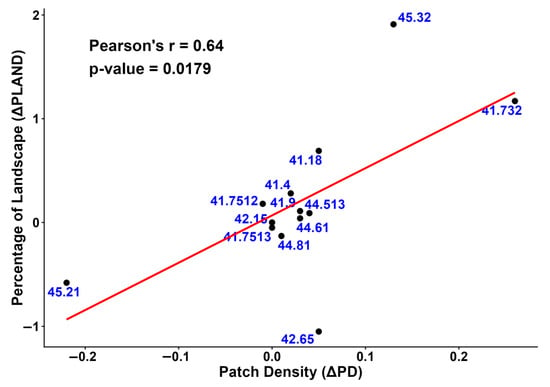

The expansion of ‘Quercus pubescens woods’, ‘Supra-Mediterranean holm oak forests’ and ‘Southern Italian beech forests’ is statistically correlated with higher Patch Density (PD) values, indicating a slight increase in fragmentation compared to 2001 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The relationship between the change in landscape percentage (ΔPLAND) and the change in patch density (ΔPD) from 2001 to 2023 is shown in this scatter plot. The red line is the regression line.

The slight fragmentation observed is linked to an increase in the number of patches that are regular in shape. This is evident from the lower Landscape Shape Index (LSI) values in 2023 compared to 2001.

In particular, Calabrian laricio pine forests (42.65) are characterized by greater fragmentation compared to 2001. This is confirmed by higher Number of Patches (NP) and Patch Density (PD) values, indicating that the habitat has been divided into smaller and more numerous fragments. The overall shape of these patches is irregular and complex, with a Landscape Shape Index (LSI) higher than that of other habitats.

Conversely, Southern Apennine silver fir forests (42.15) exhibit the lowest fragmentation, as evidenced by a reduction in Number of Patches (NP) and Patch Density (PD) compared to 2001, suggesting a stabilization of these habitats. Similar trends, with minor variations, are observed in Mediterranean riparian poplar forests (44.61) and Southern Italian Quercus frainetto woods (41.7512). The Mean Patch Area (AREA_MN) of Calabrian laricio pine forests has decreased significantly since 2001, confirming that fragments have become smaller and more numerous. Minor changes are evident in Southern Italian beech forests (41.18) and Supra-Mediterranean holm oak forests (45.32), where recent expansion has created new, smaller patches.

In contrast, Tyrrhenian cork oak forests (45.21), mixed ravine and slope forests (41.4), and Southern Italian Quercus frainetto woods (41.7512) recorded a significant increase in Mean Patch Area (AREA_MN). This confirms the increased continuity and compactness of these habitats, achieved through the merging of smaller patches into larger, more cohesive units.

3.3. Analysis of Landscape-Level Diversity Metrics

This analysis assessed how the diversity of the landscape of the Aspromonte National Park changed between 2001 and 2023 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Landscape diversity indices for the Aspromonte National Park: Temporal variation between 2001 and 2023. PR—Patch Richness; PRD—Patch Richness Density; SHDI—Shannon’s Diversity Index; SIDI—Simpson’s Diversity Index; MSIDI—Modified Simpson’s Diversity Index; SHEI—Shannon’s Evenness Index.

The results indicate that the study area has become more heterogeneous compared to 2001. This is explained by the increase in Patch Richness (PR) and Patch Richness Density (PRD), which indicates a greater variety of ecosystems. This trend is also explained by the slight increase in the Shannon diversity index (SHDI), which rose from 2.53 in 2001 to 2.56 in 2023, suggesting an improvement in the overall diversity of the study area.

In contrast, habitat distribution has become less uniform, thanks to a slight decrease in Shannon’s Evenness Index (SHEI) compared to 2001. This is explained by the fact that fewer habitats have acquired a larger portion of the landscape.

Finally, the stability of the Simpson’s Diversity Index (SIDI) and Simpson’s Evenness Index (SIEI) values between the two periods confirms that the composition of the dominant habitats has not undergone significant changes.

4. Discussion

Research conducted in the Aspromonte National Park shows that 77.2% of the area occupied by habitats remained stable between 2001 and 2023. The remaining part, on the other hand, exhibits ecological dynamics that reveal a significant qualitative and structural transformation of the existing habitats. To interpret these results, the discussion focuses on three key issues: the factors that determine habitat change and stability; changes in the structural configuration of forest types; and the evolution of overall diversity at a landscape level.

The primary drivers of this landscape transformation are the expansion of deciduous forests at the expense of grasslands and scrub habitats, a limited increase in riparian habitat, and the decline of pine forests damaged by fire. These processes impact the habitat fragmentation and biodiversity of the protected area.

An intense process of recolonization of forest habitats has been documented across many mountainous regions of Europe and the Mediterranean basin [47,48,49,50,51,52], significantly influencing landscape structure and functions [53,54,55]. The increase in forest habitat area, mainly at higher altitudes, may be linked to the depopulation of mountain villages [56] and the abandonment of traditional land management practices [57]. Although an increase in forest area is positive from an ecological and landscape stability point of view, it can harm biodiversity conservation in certain habitats, such as those with herbaceous or shrubby structures that are home to specific flora and fauna [58,59]. The transition from semi-natural habitats listed in the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) to forest habitats covered by the same directive can, in some cases, indeed lead to a reduction in biodiversity.

Although our study focuses on landscape parameters rather than direct species monitoring, the observed trends provide crucial information on potential changes in biodiversity. The loss of open habitats, such as “Mediterranean tall humid grasslands” (37.4 m) and “Madonie and Apennine hedgehog-heaths” (31.77 m), due to forest encroachment, suggests a potential threat to specialized taxa [60,61].

Semi-natural transitional habitats, such as grasslands and scrubland, often serve as biodiversity hotspots for vascular plants because they mix species from adjacent ecosystems and create unique environmental gradients (humidity, light, soil) that support a mix of specialized and generalist species, leading to high species richness and peculiar flora [62]. Therefore, despite increased carbon storage [63], the homogenization of the landscape towards closed-canopy forests could lead to a decline in the Park’s overall floristic richness.

The expansion of riparian forest habitats, such as ‘Western Mediterranean alder galleries’ (44.513) and Mediterranean riparian poplar forests (44.61), has been modest, probably due to the rivers’ torrential hydrological regime in the Aspromonte area. Unlike the more stable river basins of Central Europe, recurrent flash floods and the subsequent instability of sediments act as mechanical disturbances that prevent mature riparian forests from colonizing the area, thus maintaining riparian vegetation at the shrub or pioneer stage [64,65].

The management zoning proved to be a decisive factor; the strict protection area (Zone A) demonstrated superior ecological resilience, maintaining structural stability with only negligible alterations in the aftermath of wildfire events [66]. This underscores that the restriction of anthropogenic activities is a primary driver in mitigating regressive ecological processes. Conversely, Zone C proved to be the most dynamic, characterized by the highest rates of habitat contraction and expansion. Such variability reflects the direct impact of permitted land uses, such as grazing and silvicultural practices, which accelerate landscape turnover [67]. The expansion of forest habitats is primarily a result of progressive natural secondary succession, driven by the abandonment of agricultural land and pastures. This process facilitates the encroachment of shrub and tree species, ultimately leading to the development of more mature ecosystems [68,69]. Conversely, wildfires have acted as the primary catalyst for regressive successional trajectories. Notably, mature forests dominated by Pinus nigra subsp. laricio (42.65) have experienced a significant decline, transitioning into pioneer shrublands such as ‘Tyrrhenian broom fields’ (31.844) and ‘Spanish broom fields’ (32.A). These dynamics align with broader Mediterranean trends, where high-intensity fire regimes frequently trigger the replacement of black pine forests with fire-adapted shrub communities [70].

The increase in Percentage of Landscape (PLAND) for “Quercus pubescens woods” (41.732), “Supra-Mediterranean holm oak forests (45.32), and Southern Italian beech forests (41.18) was accompanied by increased fragmentation, as indicated by high Patch Density (PD) values. This aligns with other studies [71,72] and may be attributed to the fact that the increase in forest cover was primarily the result of land abandonment and the succession of secondary forests on agricultural lands. An increase in the Patch Index (LPI) indicates that the dominant core is enlarging and becoming more cohesive, thereby strengthening its internal structure. Meanwhile, higher Patch Density (PD) values reflect the growth of several small fragments linked to natural succession in marginal areas [73].

Mean Patch Area (AREA_MN) increased for “Southern Italian Quercus frainetto” woods (41.7512) and “Tyrrhenian cork-oak forests” (45.21) compared to 2001. This expansion is associated with low Patch Density (PD) and Landscape Shape Index (LSI) values, which contribute to the creation of larger and more continuous habitat areas. This process contributes to ensuring greater habitat availability and connectivity, facilitating the movement of organisms within the landscape [74]. The increase in the size of patches of various habitat types leads to a greater presence of rare, specialized and nemoral species, in accordance with the literature [75,76].

Riparian habitats showed an improvement in structural quality with an increase in Percentage of Landscape (PLAND), Mean Patch Area (AREA_MN), and shape complexity (LSI) towards more elongated patches [77].

The conservation of riparian habitats is essential for the structural connectivity of the territory, given their importance as ecological connectors [78,79]. These habitats support high levels of biodiversity and provide essential ecosystem services [80].

The results of the landscape analysis show that, compared to 2001, the percentage of landscape (PLAND) occupied by the ‘Calabrian laricio pine forests’ habitat (42.65) underwent a drastic reduction in 2023, while the number of patches (NP) and patch density (PD) increased. This loss of surface area has resulted in high fragmentation, which is closely linked to the severity of the fires recorded in Aspromonte National Park [81,82].

In fact, Pinus nigra subsp. laricio is a species highly susceptible to intense forest fires, which are typical of this habitat [83]. This is consistent with the study by Johnstone et al. (2011) [84], which found that coniferous forests create environmental and ecological conditions that intensify fires. The observed rapid transition to pioneer shrub formations highlights the vulnerability of this non-serotine conifer [85]. Unlike Mediterranean pines that are adapted to fire (e.g., Pinus halepensis), which activate seed banks in the canopy for rapid post-fire recolonization [86], the entities of Pinus nigra group are vulnerable to high temperatures, with heat being lethal to its seeds. As a result, the survival of Pinus nigra relies on the presence of adult trees. After a fire, “Calabrian laricio pine forests” experience significant difficulty recolonizing affected areas and dominating the post-fire vegetation composition [87]. This dynamic of degradation and floristic change is consistent with observations in black pine forests in Turkey, where fire disturbance triggered habitat replacement processes like those highlighted in our study [88]. Furthermore, this result is consistent with the dynamics observed in the Mediterranean basin, where significant losses of coniferous forests in Spain and Portugal have been linked to forest fires affecting large areas of woodland [89].

In this context, the combination of forest cover loss and the absence of a seed bank allows pioneer shrub species to dominate in the long term. The landscape analysis highlights that Patch Richness (PR) and Patch Richness Density (PRD) indices have increased slightly since 2001. This indicates greater landscape heterogeneity and diversity [90], and consequently an increase in habitat availability and landscape connectivity [91]. This trend is further confirmed by a slight increase in Shannon’s Diversity Index (SHDI), indicating a greater variety of habitat types within the study area [92].

Nevertheless, the values of diversity and uniformity in the study area remained relatively high, suggesting a complex and diverse landscape with some dominant features. Despite the accuracy of the macro-changes, the limitations of this research imply reduced sensitivity to micro-transformations. This reduction was necessary to filter out geometric misalignment and minimize cartographic noise between the two maps (produced in different contexts) for 2001 and 2023, which show variations of a few meters in the tracing of polygons.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the methodology adopted in this study offers a distinctive approach to transition analysis. Unlike many diachronic studies [93,94,95,96,97,98,99] that operate at the level of broad macro-categories (e.g., ‘forest’ or ‘agricultural’), this research utilizes a high-resolution habitat-level analysis achieving greater accuracy. This approach provides a more detailed understanding of progressive and regressive succession dynamics, ensuring greater ecological resolution. It enables a more detailed analysis of the processes leading to structural landscape fragmentation, thereby supporting targeted management and conservation decisions within the protected area

5. Conclusions

The comparison between the habitat maps for 2001 and 2023 enables a diachronic reconstruction of the vegetation and habitat landscape change in the study area, highlighting the changes that have occurred.

The results of this study show an increase in almost all forest habitats in the Aspromonte National Park, a phenomenon linked to the decline in agriculture, grazing and deforestation. Against the trend, “Calabrian laricio pine forests” have suffered a decrease in their extent due to the extensive fires that affected the Park in 2021. Although these areas are currently characterized by shrubland, the general expansion of broad-leaved forests elsewhere in the park suggests an emerging trend of ecological succession.

Replacing coniferous forests with broadleaved forests could create a landscape that is naturally less susceptible to fires, thanks to the latter’s higher moisture content and lower flammability. This transition could enhance the long-term ecological resilience of Aspromonte National Park.

Understanding the dynamics of forest habitats is crucial for promoting the conservation of overall biodiversity [99], but it also has implications for species conservation [100].

For planning purposes, one of the most effective strategies could be to connect fragmented habitats, promoting the creation of new corridors and stepping stones to ensure greater connectivity [74,97], through targeted interventions such as reforestation with native species using potential natural vegetation as a model.

These measures are crucial for ensuring greater availability of habitats for various animal and plant species, as well as for supporting ecosystem resilience and strengthening their ability to adapt to environmental changes. This supports the goals of Agenda 2030, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the IPCC strategy for combating climate change.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15020235/s1. Table S1: Crosswalk table among Habitat Nature Map (code and name), habitat types in the Directive (92/43) and the Corine Land Cover class; Table S2: Transition matrix; Table S3: Percentage change in habitat area between 2001 and 2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., G.S. and D.C.; methodology, A.M., G.S. and D.C.; software, A.M., G.S. and D.C.; investigation, A.M., G.S. and D.C.; data curation, A.M. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, A.M., G.S. and D.C.; project administration, G.S.; funding acquisition, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by “Nature Map System” project signed between the AGRARIA Department—Mediterranean University of Reggio Calabria and the Territory and Environment Department of Calabria Region, Sector 5, Parks and Protected Natural Areas, under the Regional Operational Program (ROP) 2014/2020—Action 6.5.A.1—Actions provided for in the Prioritez Action Framework (PAF) in the Natura 2000 Network Management Plans, scientific manager Giovanni Spampinato.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Walther, G.R. Community and ecosystem responses to recent climate change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2019–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, J.; Barber, I.; Boag, B.; Ellison, A.R.; Morgan, E.R.; Murray, K.; Booth, M.; Pascoe, E.L.; Sait, S.M.; Wilson, A.J. Global change, parasite transmission and disease control: Lessons from ecology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmann, J.; Coad, L.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.D.; Hockings, M.; Knights, K.; Leverington, F.; Cuadros, I.C.; Zamora, C.; Woodley, S.; et al. Changes in protected area management effectiveness over time: A global analysis. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.L.; Hill, S.L.; Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Borger, L.; Contu, S.; Hoskins, A.J.; Ferrier, S.; Purvis, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.W. Local biodiversity is higher inside than outside terrestrial protected areas worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M.H.; Larrosa, C.; Burgess, N.D.; Balmford, A.; Jonhston, A.; Mbilinyi, B.P.; Platts, P.J.; Coad, L. Deforestation in an Africa biodiversity hotspot: Extent, variation and the effectiveness of protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 164, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, L.; Campbell, A.; Miles, L.; Humphries, K. The Costs and Benefits of Protected Areas for Local Livelihoods: A Review of the Current Literature; UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Butchart, S.H.; Walpole, M.; Collen, B.; Van Strien, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Almond, R.E.; Watson, R.; Baillie, J.M.; Bomhard, B.; Brown, C.; et al. Global biodiversity: Indicators of recent declines. Science 2010, 328, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldmann, J.; Barnes, M.; Coad, L.; Craigie, I.D.; Hockings, M.; Burgess, N.D. Effectiveness of terrestrial protected areas in reducing habitat loss and population declines. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 161, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, T.M.; Bakarr, M.I.; Boucher, T.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Hoekstra, J.M.; Moritz, T.; Olivier, S.; Parrish, J.; Pressey, R.L.; et al. Coverage provided by the global protected-area system: Is it enough? Bioscience 2004, 54, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiolini, C.; Bonari, G.; Landi, M. Focal plant species and soil factors in Mediterranean coastal dunes: An undisclosed liaison? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 211, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, S.S. The challenge to manage the biological integrity of nature reserves: A landscape ecology perspective. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 2613–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y. Determination of land degradation causes in Tongyu County, Northeast China via land cover change detection. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2010, 12, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, M.L.; Frate, L.; Acosta, A.T.; Hoyos, L.; Ricotta, C.; Cabido, M. Measuring forest fragmentation using multitemporal remotely sensed data: Three decades of change in the dry Chaco. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 47, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertes, C.M.; Schneider, A.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Tatem, A.J.; Tan, B. Detecting change in urban areas at continental scales with MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 158, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Chapin, F.S.; Ewel, J.J.; Hector, A.; Inchausti, P.; Lavorel, S.; Wardle, D.A. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: A consensus of current knowledge. Monogr. Ecol. 2005, 75, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.M.; Joppa, L.N.; Gittleman, J.L.; Stephens, P.R.; Pimm, S.L. Estimating the normal background rate of species extinction. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.D.; Cameron, A.; Green, R.E.; Bakkenes, M.; Beaumont, L.J.; Collingham, Y.C.; Erasmus, B.F.; De Siqueira, M.F.; Grainger, A.; Hannah, L.; et al. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 2004, 427, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Barnosky, A.D.; García, A.; Pringle, R.M.; Palmer, T.M. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbati, A.; Corona, P.; Salvati, L.; Gasparella, L. Natural forest expansion into suburban countryside. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Gitas, I.; Bajocco, S. Spatial determinants of land-use changes in an urban region (Attica, Greece) between 1987 and 2007. J. Land Use Sci. 2015, 10, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiraglia, D.; Ceccarelli, T.; Bajocco, S.; Perini, L.; Salvati, L. Unraveling landscape complexity: Land use/land cover changes and landscape pattern dynamics (1954–2008) in contrasting peri-urban and agro-forest regions of northern Italy. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 916–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandii, M.G.; Prisco, I.; Acosta, A.T.R. Hard times for Italian coastal dunes: Insights from a diachronic analysis based on random plots. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 27, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hédl, R.; Kopecký, M.; Komárek, J. Half a century of succession in a temperate oakwood: From species-rich community to mesic forest. Divers. Distrib. 2010, 16, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, M.; Hédl, R.; Szabó, P. Non-random extinctions dominate plant community changes in abandoned coppices. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignatti, E.; Pignatti, S. Plant Life of the Dolomites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 550. [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio, S.; Prisco, I.; Acosta, A.T.; Stanisci, A. Changes in plant species composition of coastal dune habitats over a 20-year period. AoB Plants 2015, 7, plv018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, D.; Attorre, F.; Venanzoni, R.; Acosta, A.T.R.; Agrillo, E.; Aleffi, M.; Zitti, S.; Alessi, N.; Allegrezza, M.; Angelini, P.; et al. A methodological protocol for Annex I Habitats monitoring: The contribution of Vegetation science. Plant Sociol. 2016, 53, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Xi, Y.; Lu, C. Spatio–temporal changes of forests in northeast China: Insights from landsat images and geospatial analysis. Forests 2019, 10, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Hansen, K.; Li, Q.; Wei, X. The Cumulative Effects of Forest Disturbance and Climate Variability on Streamflow in the Deadman River Watershed. Forests 2019, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, W.S.W.M.; Maulud, K.N.A.; Kamarulzaman, A.M.M.; Raihan, A.; Sah, S.M.; Ahmad, A.; Saad, S.N.M.; Azmi, A.T.M.; Syukri, N.K.A.J.; Khan, W.R. The influence of forest degradation on land surface temperature—A case study of Perak and Kedah, Malaysia. Forests 2020, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van Eysenrode, D. Decision tree algorithm for detection of spatial processes in landscape transformation. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barima, Y.S.S. Dynamique, Fragmentation et Diversité Végétale des Paysages Forestiers en Milieux de Transition Forêt-Savane dans le Département de Tanda, Côte d’Ivoire. Doctoral Dissertation, Free University of Brussels, Brussles, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soverel, N.O.; Coops, N.C.; White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A. Characterizing the forest fragmentation of Canada’s 259 national parks. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 164, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Roy, P.S. Forest fragmentation in the Himalaya: A central Himalayan case study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2007, 14, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coops, N.C.; Wulder, M.A.; White, J.C. Identifying and describing forest disturbance and spatial pattern: Data selection issues. In Understanding Forest Disturbance and Spatial Pattern: Remote Sensing and GIS Approaches; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Ürker, O.; Günlü, A.; Ataol, M. Use of GUIDOS to analyze fragmentation features and test corridor creation for a fragmented forest ecosystem in Northern-Central Turkey. Austrian J. For. Sci. 2023, 140, 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, F.; Praticò, S.; Piovesan, G.; Chiarucci, A.; Argentieri, A.; Modica, G. Characterizing historical transformation trajectories of the forest landscape in Rome’s metropolitan area (Italy) for effective planning of sustainability goals. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 4708–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullo, S.; Scelsi, F.; Spampinato, G. La Vegetazione dell’Aspromonte (Studio Fitosocilogico); Laruffa Editore: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Spampinato, G.; Camerieri, P.; Caridi, D.; Crisafulli, A. Carta della Biodiversità Vegetale del Parco Nazionale dell’Aspromonte (Italia meridionale). Quad. Bot. Amb. Appl. 2008, 19, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aramini, G.; Bernardo, L.; Spampinato, G. (Eds.) Carta Natura; Geografia degli Habitat; Monografia Calabria; Arti Grafiche Cardamone: Decollatura, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- McGarigal, K.; Ene, E. FRAGSTATS: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Categorical Maps, Version 4.2; Computer Software Program Produced by the Authors at the University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.fragstats.org (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- McGarigal, K.; Marks, B.J. FRAGSTATS: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Quantifying Landscape Structure; Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-351; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 1995; 122p.

- Paudel, S.; Yuan, F. Assessing landscape changes and dynamics using patch analysis and GIS modeling. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 16, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, S.; Petropoulos, G.P.; Singh, S.K.; Szabó, S.; Bachari, N.E.I.; Srivastava, P.K.; Suman, S. Quantifying land use/land cover spatio-temporal landscape pattern dynamics from Hyperion using SVMs classifier and FRAGSTATS. Geocarto Int. 2018, 33, 862–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Reddy, C.S.; Pasha, S.V.; Dutta, K.; Saranya, K.R.L.; Satish, K.V. Modeling the spatial dynamics of deforestation and fragmentation using Multi-Layer Perceptron neural network and landscape fragmentation tool. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 99, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roura-Pascual, N.; Pons, P.; Etienne, M.; Lambert, B. Transformation of a Rural Landscape in the Eastern Pyrenees between 1953 and 2000. Mt. Res. Dev. 2005, 25, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, S.; Di Pasquale, G.; Mulligan, M.; Di Martino, P.; Rego, F.C. (Eds.) Recent Dynamics of the Mediterranean Vegetation and Landscape; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzakis, I.N.; Pungetti, G.; Mannion, A.M. (Eds.) Mediterranean Island Landscapes: Natural and Cultural Approaches; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Verburg, P.H.; van Berkel, D.B.; van Doorn, A.M.; van Eupen, M.; van den Heiligenberg, H.A. Trajectories of land use change in Europe: A model-based exploration of rural futures. Landsc. Ecol. 2010, 25, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, M.; Carranza, M.L.; Moravec, D.; Cutini, M. Reforestation dynamics after land abandonment: A trajectory analysis in Mediterranean mountain landscapes. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 2459–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameztegui, A.; Morán-Ordóñez, A.; Márquez, A.; Blázquez-Casado, Á.; Pla, M.; Villero, M.B.; García, D.; Errea, M.P.; Coll, L. Forest expansion in mountain protected areas: Trends and consequences for the landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 216, 104240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K.; McComb, W.C. Relationships between landscape structure and breeding birds in the Oregon Coast range. Ecol. Monogr. 1995, 65, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, G.; Oberhuber, W.; Gruber, A. Effects of climate change at treeline: Lessons from space-for-time studies, manipulative experiments, and long-term observational records in the Central Austrian Alps. Forests 2019, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryn, A. Recent forest limit changes in south-east Norway: Effects of climate change or regrowth after abandoned utilisation? Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2008, 62, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcucci, A.; Maiorano, L.; Boitani, L. Changes in land-use/land-cover patterns in Italy and their implications for biodiversity conservation. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geri, F.; Rocchini, D.; Chiarucci, A. Landscape metrics and topographical determinants of large-scale forest dynamics in a Mediterranean landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrascano, S.; Chytrý, M.; Kuemmerle, T.; Giarrizzo, E.; Luyssaert, S.; Sabatini, F.M.; Blasi, C. Current European policies are unlikely to jointly foster carbon sequestration and protect biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 201, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temperton, V.M.; Buchmann, N.; Buisson, E.; Durigan, G.; Kazmierczak, Ł.; Perring, M.P.; Overbeck, G.E.; de Sa Dechoum, M.; Veldman, J.W. Step back from the forest and step up to the Bonn Challenge: How a broad ecological perspective can promote successful landscape restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2019, 27, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodka, Š.; Konvička, M.; Čížek, L. Habitat preferences of oak-feeding xylophagous beatles in a temperate woodland: Implications for forest history and management. J. Insect Conserv. 2009, 13, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Moran-ordonez, A.; Garcia, J.T.; Calero-Riestra, M.; Alda, F.; Sanz, J.; Suarez-Seoane, S. Current landscape attributes and landscape stability in breeding grounds explain genetic differentiation in a long-distance migratory bird. Anim. Conserv. 2021, 24, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Ci, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Cao, G.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Thornhill, A.H.; Conran, J.G.; et al. Transitional Areas of Vegetation as Biodiversity Hotspots Evidenced by Multifaceted Biodiversity Analysis of a Dominant Group in Chinese Evergreen Broad-Leaved Forests. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, E.; Pulido, F.; Moreno, G.; Zavala, M.Á. Targeted policy proposals for managing spontaneous forest expansion in the Mediterranean. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, J.C.; Rodríguez-González, P.M.; Dufour, S.; Bendix, J. Riparian vegetation research in Mediterranean-climate regions: Common patterns, ecological processes, and considerations for management. Hydrobiologia 2013, 719, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombino, G.; Zema, D.A.; Denisi, P.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Labate, A.; Zimbone, S.M. Assessment of riparian vegetation characteristics in Mediterranean headwaters regulated by check dams using multivariate statistical techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richiardi, C.; Siniscalco, C.; Garbarino, M.; Adamo, M. Unravelling decades of habitat dynamics in protected areas: A hierarchical approach applied to the Gran Paradiso National Park (NW Italy). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, R.C.; Iaria, J.; Moretti, G.; Amendola, V.; Cassola, F.M.; Cerretti, P.; Chiarucci, A.; Di Musciano, M.; Francesconi, L.; Frattaroli, A.R.; et al. EU2030 biodiversity strategy: Unveiling gaps in the coverage of ecoregions and threatened species within the strictly protected areas of Italy. J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 79, 126621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assini, S.; Filipponi, F.; Zucca, F. Land cover changes in an abandoned agricultural land in the Northern Apennine (Italy) between 1954 and 2008: Spatio-temporal dynamics. Plant Biosyst.-Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2015, 149, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandra, F.; Vitali, A.; Urbinati, C.; Garbarino, M. 70 years of land use/land cover changes in the Apennines (Italy): A meta-analysis. Forests 2018, 9, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavgacı, A.; Balpınar, N.; Öner, H.H.; Arslan, M.; Bonari, G.; Chytrý, M.; Čarni, A. Classification of forest and shrubland vegetation in Mediterranean Turkey. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2021, 24, 12589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Kuemmerle, T.; Elbakidze, M.; Ozdogan, M.; Radeloff, V.C.; Keuler, N.S.; Prishchepov, A.V.; Kruhlov, I.; Hostert, P. Patterns and drivers of post-socialist farmland abandonment in Western Ukraine. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, J.; Ziółkowska, E.; Vogt, P.; Dobosz, M.; Kaim, D.; Kolecka, N.; Ostafin, K. Forest-cover increase does not trigger forest-fragmentation decrease: Case Study from the Polish Carpathians. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neel, M.C.; McGarigal, K.; Cushman, S.A. Behavior of class-level landscape metrics across gradients of class aggregation and area. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 19, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S.; Bodin, Ö.; Fortin, M.-J. Stepping stones are crucial for species’ long-distance dispersal and range expansion through habitat networks. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 51, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, L.; Fipaldini, M.; Marignani, M.; Blasi, C. Effects of fragmentation on vascular plant biodiversity in a Mediterranean forest archipelago. Plant Biosyst. 2010, 144, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolastri, A.; Bricca, A.; Cancellieri, L.; Cutini, M. Understory functional response to different management in the Mediterranean beech forest (central Apennine, Italy). For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 400, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, F.; Lausch, A.; Müller, E.; Thulke, H.H.; Steinhardt, U.T.A.; Lehmann, S. Landscape metrics for assessment of landscape destruction and rehabilitation. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, V.; Velázquez, J.; Pascual, Á.; Herráez, F.; Gómez, I.; Gutiérrez, J.; Sánchez, B.; Hernando, A.; Santamaría, T.; Sánchez-Mata, D. Connectivity of Natura 2000 potential natural riparian habitats under climate change in the Northwest Iberian Peninsula: Implications for their conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, A.; Velázquez, J.; Caridi, D.; Spampinato, G. Analysis of the Connectivity and Biodiversity of the Natura 2000 Network, a Case Study in Calabria (Southern Italy). Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5149311 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Mckergow, L.A.; Matheson, F.E.; Quinn, J.M. Riparian management: A restoration tool for New Zealand streams. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2016, 17, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombino, G.; Barbaro, G.; Pérez-Cutillas, P.; D’Agostino, D.; Denisi, P.; Foti, G.; Zimbone, S.M. Use of Logs Downed by Wildfires as Erosion Barriers to Encourage Forest Auto-Regeneration: A Case Study in Calabria, Italy. Water 2023, 15, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombino, G.; D’Agostino, D.; Marziliano, P.A.; Pérez Cutillas, P.; Praticò, S.; Proto, A.R.; Manti, L.M.; Lofaro, G.; Zimbone, S.M. A Nature-Based Approach Using Felled Burnt Logs to Enhance Forest Recovery Post-Fire and Reduce Erosion Phenomena in the Mediterranean Area. Land 2024, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, D.; Deni, B. Remote sensing and GIS-based forest fire risk zone mapping: The case of Manisa Turkey. Turk. J. For. 2020, 21, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, J.F.; Rupp, T.S.; Olson, M.; Verbyla, D. Modeling impacts of fire severity on successional trajectories and future fire behavior in Alaskan boreal forests. Landsc. Ecol. 2011, 26, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanner, R.M. Seed dispersal in Pinus. In Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kavgacı, A.; Örtel, E.; Torres, E.; Safford, H. Early postfire vegetation recovery of Pinus brutia forests: Effects of fire severity, prefire stand age, and aspect. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2016, 40, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Llovet, J.; Rodrigo, A.; Vallejo, R. Are wildfires a disaster in the Mediterranean basin? A review. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş, E.S.; Kavgacı, A. Anadolu karaçamı (Pinus nigra J.F. Arnold subsp. pallasiana Lamb. Holmboe) Ormanlarında Yangın Sonrası Vejetasyon Dinamiği (Post-Fire Vegetation Dynamics in Anatolian Black Pine (Pinus nigra J.F. Arnold subsp. pallasiana Lamb. Holmboe) Forests). Ph.D. Thesis, Karabük University, Karabük, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Leite, F.; Bento-Gonçalves, A.; Vieira, A.; Nunes, A.; Lourenço, L. Incidence and recurrence of large forest fires in mainland Portugal. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 1035–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.P.C.; Goslee, S.C. Landscape Diversity. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 3, pp. 645–658. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Ecological Responses to Habitat Fragmentation Per Se. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelaru, D.; Oiste, A.; Mihai, F. Quantifying the changes in landscape configuration using open source GIS. Case study: Bistritasubcarpathian valley. In SGEM Conference Proceedings, Proceedings of the 14th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference on Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation SGEM 2014, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; SGEM World Science Publishing House: Vienna, Austria, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 557–565. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Reyes, U.J.; Niño-Maldonado, S.; Barrientos-Lozano, L.; Treviño-Carreón, J. Assessment of land use-cover changes and successional stages of vegetation in the natural protected area Altas Cumbres, Northeastern Mexico, using Landsat satellite imagery. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, B.; Zhang, L.; Keshtkar, H.; Haack, B.N.; Rijal, S.; Zhang, P. Land use/land cover dynamics and modeling of urban land expansion by the integration of cellular automata and markov chain. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouvardas, D.; Karatassiou, M.; Tsioras, P.; Tsividis, I.; Palaiochorinos, S. Spatiotemporal changes (1945–2020) in a grazed landscape of northern Greece, in relation to socioeconomic changes. Land 2022, 11, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xofis, P.; Spiliotis, J.A.; Chatzigiovanakis, S.; Chrysomalidou, A.S. Long-term monitoring of vegetation dynamics in the Rhodopi Mountain Range National Park-Greece. Forests 2022, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacka, M.; Żywica, P.; Subirós, J.V.; Bródka, S.; Macias, A. How do the surrounding areas of national parks work in the context of landscape fragmentation? A case study of 159 protected areas selected in 11 EU countries. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parracciani, C.; Gigante, D.; Mutanga, O.; Bonafoni, S.; Vizzari, M. Land cover changes in grassland landscapes: Combining enhanced Landsat data composition, LandTrendr, and machine learning classification in google earth engine with MLP-ANN scenario forecasting. GIScience Remote Sens. 2024, 61, 2302221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquer-Rodríguez, M.; Torella, S.; Gavier-Pizarro, G.; Volante, J.; Somma, D.; Ginzburg, R.; Kuemmerle, T. Effects of past and future land conversions on forest connectivity in the Argentine Chaco. Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 30, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, M.L.; Hoyos, L.; Frate, L.; Acosta, A.T.; Cabido, M. Measuring forest fragmentation using multitemporal forest cover maps: Forest loss and spatial pattern analysis in the Gran Chaco, central Argentina. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.