Abstract

As a core city in central China and a key node of the Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan (CZT) Metropolitan Area, Changsha has experienced profound territorial space restructuring amid rapid urbanization and high-quality development. This study focuses on the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics, driving mechanisms, and future optimization paths of production–living–ecological space (PLES) in Changsha, using three key time nodes: 2010, 2020, and 2025. Based on updated land use data (30 m spatial resolution), socioeconomic statistics, and the latest territorial spatial planning policies, we integrated multiple research methods including the land use transfer matrix, dynamic degree model, Logistic regression, and FLUS (Future Land Use Simulation) model. The results reveal the evolutionary law of PLES space from “rapid expansion” (2010–2020) to “quality improvement” (2020–2025) in Changsha and simulate the 2035 PLES layout under three scenarios (natural development, cultivated land protection, and ecological protection) incorporating rigid policy constraints such as urban development boundaries and ecological conservation red lines. This research provides updated scientific support for the coordinated and sustainable development of territorial space in new first-tier cities and metropolitan area cores.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Significance

First, it is necessary to clarify the concept and significance of production–living–ecological space (PLES): PLES is a functional territorial organization paradigm with Chinese characteristics, defined as a spatial system that classifies territorial space into three primary types based on dominant functions—production space (for agricultural/industrial output, ensuring food security and economic development), living space (for residential and public services, meeting human habitation and social needs), and ecological space (for ecological regulation and conservation, maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem stability) [1]. This classification breaks through the limitations of traditional land use classification (e.g., focusing only on land cover or single economic functions) and Western urban ecological frameworks (e.g., urban–rural dichotomy or ecosystem service zoning), emphasizing the synergy and balance of multiple spatial functions. For example, unlike the Western “urban growth boundary” that mainly restricts expansion, PLES integrates agricultural protection and ecological conservation into a unified planning system, which has become a core theoretical framework for China’s territorial spatial governance under the transition to high-quality development [1,2].

In the context of China’s transition from high-speed urbanization to high-quality development, the rational allocation of PLES has become a core task of territorial spatial governance. As the capital of Hunan Province and a national central city candidate, Changsha —classified as a new first-tier city in China, with its economic scale (GDP of CNY 1.196 trillion in Q3 2025) and urbanization level (82.6%) matching the modernization characteristics of core metropolitan cities [3]—has witnessed drastic changes in its territorial space pattern over the past 15 years. The selection of 2010, 2020, and 2025 as key time nodes is based on the following policy and development context evidence:

- (1)

- 2010: Marked the start of China’s “Twelfth Five-Year Plan” and the acceleration stage of Changsha’s urbanization—with the implementation of the “Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan Urban Agglomeration Construction Plan” (approved in 2007), the city entered a phase of large-scale industrialization and urban expansion [4];

- (2)

- 2020: Coincided with the end of China’s “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan” and the release of the “National Territorial Spatial Planning Outline (2021–2035)”, Changsha shifted from “scale expansion” to “quality improvement”, and the CZT Metropolitan Area integration strategy was officially elevated to a provincial key task [5];

- (3)

- 2025: As the midpoint of the new round of territorial spatial planning (2021–2035), it reflects the initial effects of policies such as the “Hunan Cultivated Land Protection Territorial Spatial Special Plan (2021–2035)” and the “CZT Metropolitan Area Green Heart Protection Revised Regulations (2024)”, and is also the first year of post-COVID-19 economic recovery, making it a critical node to observe the adjustment of urban spatial development models [6].

From 2010 to 2020, the city experienced rapid urban expansion with accelerated industrialization and urbanization (e.g., the urban built-up area expanded from 326.8 km2 to 716.0 km2, and the urbanization rate increased from 67.6% to 79.5% [Changsha Statistical Yearbook 2021]); while the period 2020–2025 marked a strategic shift towards “CZT Metropolitan Area integration” and “high-quality development”, accompanied by optimized territorial space development patterns and strengthened ecological and cultivated land protection (e.g., the decrease rate of Green Ecological Space dropped by 69.8% compared with 2010–2020, as shown in Section 3.1.1).

Against this backdrop, analyzing the spatiotemporal evolution of PLES based on the above three nodes is of great practical and theoretical significance. Theoretically, it enriches the research system of PLES evolution in metropolitan core cities under the background of development stage transformation and bridges the gap between China-specific PLES research and global urban ecological and land-use studies (e.g., linking PLES function synergy to international research on sustainable urban form [7,8]). Practically, it provides a scientific basis for optimizing Changsha’s territorial space layout, coordinating urban expansion and ecological protection, and promoting the sustainable development of the CZT Metropolitan Area.

1.2. Literature Review

Domestic and foreign scholars have conducted in-depth research on PLES (and its equivalent concepts in global studies), covering multiple dimensions such as theoretical construction, empirical analysis, and method innovation, laying a solid foundation for subsequent studies.

In terms of international research, the focus has mainly been on the interaction between urban functional space and ecological environment, as well as the optimization of residential space layout. For example, Buya et al. [9] utilized binary logistic regression and multinomial logistic regression models to simulate land use changes in Thailand, exploring the driving mechanisms of spatial pattern evolution from a quantitative perspective, which provides a reference for the selection of driving factor analysis methods in PLES space research. Kipkulei et al. [10] took Trans Nzoia County in Kenya as a case to model cropland expansion and its driving factors, emphasizing the impact of human activities such as agricultural production on spatial changes, and enriching the understanding of the interaction between production space and natural environment. Heilig et al. [11] systematically analyzed the anthropogenic factors in land use changes in China, pointing out that population growth and economic development are core drivers of spatial structure adjustment, which has important guiding significance for exploring the socioeconomic driving mechanisms of PLES space evolution. Additionally, studies on urban residential space layout optimization have focused on balancing living comfort and ecological sustainability. For instance, research on the coupling coordination between urban microclimate and landscape ecological risk (similar to the idea of Fan et al. [7]) has provided inspiration for the optimization of living space in the context of ecological protection.

Domestic research on PLES has formed a relatively complete system, mainly involving the construction of classification systems, analysis of spatiotemporal evolution characteristics, identification of driving mechanisms, and exploration of simulation methods, and has achieved fruitful results.

In terms of classification system construction, Liu et al. [1] proposed a national-scale “production-living-ecological” space classification and evaluation system, clarifying the functional orientation of different spatial types, which has become a classic framework for domestic PLES space research. Zhang et al. [12] further refined the classification system from the perspective of ecological–living–industrial land, and analyzed its spatial distribution characteristics in China, providing a basis for regional-specific classification adjustments. Huang et al. [2] systematically reviewed the research progress of PLES space identification and optimization, summarizing the advantages and disadvantages of different classification methods, and pointing out the direction for the construction of a targeted classification system for specific regions.

In the study of spatiotemporal evolution characteristics, scholars have carried out empirical research on different spatial scales, and the research focus shows obvious scale differences:

Basin scale: Focus on the impact of natural conditions (e.g., hydrology, terrain) on PLES evolution. For example, Zhou et al. [13] analyzed the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of PLES in the Yellow River Basin and its driving factors, revealing the law of spatial change under the combined influence of natural conditions (e.g., soil erosion) and human activities. Wang et al. [14] studied the evolution of land use functions and their eco-environmental effects in the Tarim River Basin from the perspective of PLES, emphasizing the sensitivity of spatial evolution to ecological factors (e.g., water resources) in arid regions.

County scale: Focus on small-scale spatial governance and scenario simulation. For example, Chen et al. [15] took the Three Gorges Reservoir Area as a case, analyzed the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of PLES, and conducted scenario simulation, providing a reference for small-scale regional spatial governance. Duan et al. [16] identified rural PLES from the perspective of villagers’ behavior and analyzed its spatiotemporal evolution, enriching the research perspective of rural spatial evolution.

Urban agglomeration scale: Focus on inter-city spatial coordination. For example, Li et al. [4] simulated the land space of the CZT Urban Agglomeration from the perspective of the symbiosis between urban development and ecological protection, which is of great significance for the coordinated evolution research of PLES in urban agglomerations.

In terms of driving mechanism research, domestic scholars have comprehensively explored the influencing factors of PLES space evolution from multiple dimensions such as natural geography, socioeconomic development, and policy constraints. Deng et al. [17] studied the influence mechanism of PLES space changes in the process of urbanization in Guangdong Province, pointing out that GDP density and population density are key drivers of spatial structure adjustment. Xu et al. [5] analyzed the evolution characteristics and formation mechanism of PLES space in China from the perspective of main function zones, emphasizing the guiding role of policy factors in spatial evolution. Wang et al. [18] optimized the territorial space structure based on regional function orientation and confirmed that natural geographical factors such as elevation and slope restrict the distribution of agricultural and ecological space.

In the field of simulation and optimization methods, scenario simulation and dynamic monitoring technologies have been widely applied, and the research logic follows “method comparison → scenario design → optimization path”:

Method comparison: Huang et al. [19] compared different land use spatial pattern simulation methods in the Yanhe River Basin, clarifying the applicability of various models in different regions; Zhao et al. [20] used the CLUE-S model to dynamically simulate county-level PLES conflicts, providing a method reference for spatial conflict governance.

Scenario design: Sun et al. [21] conducted scenario simulation of land use in the poverty belt around Beijing and Tianjin, exploring the PLES optimization path under the background of poverty alleviation and ecological protection; Li et al. [4] simulated the land space of the CZT Urban Agglomeration from the perspective of urban–ecological symbiosis.

Optimization path: Ou et al. [22] proposed a compound optimization method for territorial spatial structure at the city scale; Xiao et al. [23] identified PLES conflicts and carried out zoning optimization; Xie et al. [6] proposed a land space development zoning method based on resource–environmental carrying capacity, providing technical support for PLES division.

However, despite the rich research results, existing studies still have certain limitations: First, most studies focus on PLES evolution before 2020 and lack the integration of 2020–2025 data that reflects the new development stage. Second, in PLES scenario simulation, the consideration of policy constraints is not comprehensive enough. Third, the research on the driving mechanism of PLES evolution in the quality improvement stage is insufficient. Fourth, in terms of research scope, there is a lack of in-depth exploration of PLES evolution laws in specific core cities of urban agglomerations.

This study aims to fill the above gaps: by updating the research time series to 2025, it integrates the latest data to reflect the spatial evolution characteristics of the new development stage; by strengthening the connection between research results and current policy practices, it fully incorporates policy constraints such as CZT Metropolitan Area Green Heart protection and urban development boundary control into the scenario simulation; by focusing on the quality improvement stage of Changsha’s territorial space development, it deeply analyzes the driving mechanism of PLES evolution in this stage; and by taking Changsha as the specific research object, it provides a reference for the PLES governance of core cities in urban agglomerations.

1.3. Research Content, Objectives, and Content

1.3.1. Explicit Research Questions

To address the above gaps and link literature review to methodology, this study proposes three core research questions:

- (1)

- Evolution law question: How did the spatiotemporal pattern of Changsha’s PLES evolve from 2010 to 2025, and what are the differences in evolutionary characteristics between the “rapid expansion stage” (2010–2020) and “quality improvement stage” (2020–2025)?

- (2)

- Driving mechanism question: What are the key driving factors of Changsha’s PLES evolution, especially the interaction between policy constraints (e.g., ecological red lines, cultivated land protection) and socioeconomic factors?

- (3)

- Scenario optimization question: Under different policy scenarios (natural development, cultivated land protection, ecological protection), what will Changsha’s 2035 PLES layout look like, and which scenario best balances urban development, food security, and ecological security?

1.3.2. Research Objectives

- (1)

- Clarify the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of Changsha’s PLES from 2010 to 2025, revealing stage-specific rules.

- (2)

- Identify the key driving factors of PLES evolution, especially the role of policy constraints.

- (3)

- Simulate 2035 PLES layouts under multiple scenarios and propose targeted optimization paths for territorial space governance.

1.3.3. Research Content

- (1)

- Construct a PLES space classification system suitable for Changsha, based on land use data of 2010, 2020, and 2025 (addressing Research Question 1).

- (2)

- Analyze the quantitative structure change and spatial pattern evolution characteristics of PLES space in Changsha during 2010–2025, comparing the two stages (addressing Research Question 1).

- (3)

- Identify the key driving factors affecting the evolution of PLES space using Logistic regression model, incorporating policy intensity indicators (addressing Research Question 2).

- (4)

- Simulate the 2035 PLES space layout under three scenarios using the FLUS model, analyze scenario differences, and propose optimization suggestions (addressing Research Question 3).

1.4. Technical Route

First, collect and process data such as land use, socioeconomic statistics, and policy documents for 2010, 2020, and 2025 (supporting Research Question 1). Second, analyze the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of PLES space using the land use transfer matrix and dynamic degree model (answering Research Question 1). Third, identify the driving factors of PLES space evolution through Logistic regression (incorporating policy intensity) (answering Research Question 2). Finally, simulate the future PLES space layout using the FLUS model, conduct scenario comparison, and propose optimization paths (answering Research Question 3).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

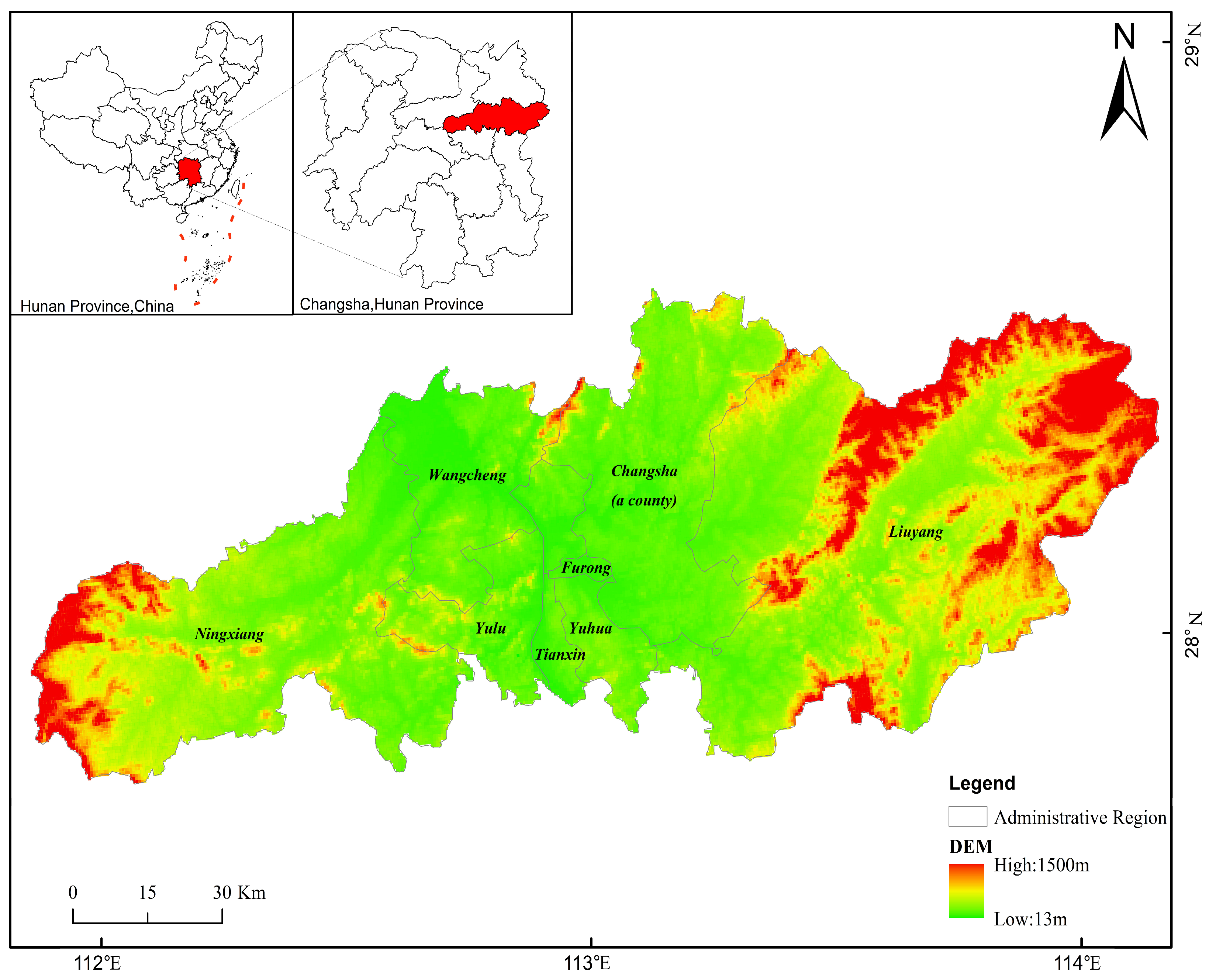

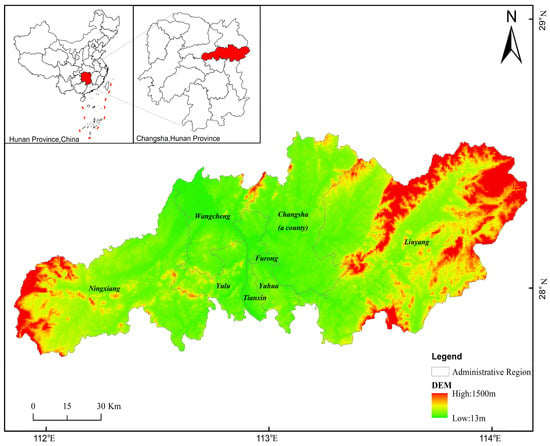

Changsha is in the northeastern part of Hunan Province, south of the Yangtze River, covering 6 municipal districts (Yuelu, Furong, Tianxin, Kaifu, Yuhua, Wangcheng), 1 county (Changsha County), and 2 county-level cities (Liuyang, Ningxiang), with a total land area of 11,816 km2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

- (1)

- Ecological Environment Characteristics

The terrain is undulating, with mountains (accounting for 29.5% of the total area) in the northeast (Liuyang Eastern Mountains) and northwest (Ningxiang Western Mountains), plains (35.8%) in the central region, and hills (34.7%) in the transition zone. The Xiangjiang River (the largest tributary of the Yangtze River in Hunan) runs through the city from south to north, with 58 primary tributaries such as the Liuyang River and Laodao River, forming a dense water system (water area accounts for 2.5% of the total area). The city has a subtropical monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of 17.2 °C and average annual precipitation of 1422 mm, which is conducive to the growth of forests (forest coverage rate reaches 54.7% [Changsha Environmental Quality Report 2025]). In addition, the CZT Metropolitan Area Green Heart (602.79 km2) (Figure 1), a national-level ecological protection area, is in the southern part of Changsha, which is a core ecological barrier of the city [Revised Regulations on the Protection of the Green Heart Area of the CZT Metropolitan Area, 2024].

- (2)

- Socioeconomic Development Characteristics

By 2025, the permanent resident population of Changsha reached 10.6165 million, with an urbanization rate of 82.6%. The GDP in the first three quarters of 2025 was CNY 1.196 trillion, a year-on-year increase of 5.0%, of which the added value of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries was CNY 33.418 billion, CNY 429.926 billion, and CNY 732.646 billion, respectively. As the core of the CZT Metropolitan Area, Changsha is promoting the construction of a “modern great Changsha Metropolitan Area” and strengthening the integration development with Zhuzhou and Xiangtan, which has profoundly affected the evolution of its PLES pattern.

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

The data required for this study and their acquisition channels are as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sources and Processing Details of Research Data.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. PLES Space Classification System

Based on the dominant function of land use, referring to the “Guidelines for territorial and spatial detailed planning (2025)” and relevant research results [1,12], this study divides Changsha’s territorial space into 3 primary types and 7 secondary types of PLES, which is suitable for the actual development of Changsha (Table 2).

Table 2.

Production–living–ecological space (PLES) classification system in Changsha.

2.3.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution Analysis Methods

- (1)

- Land Use Dynamic Degree Model

The land use dynamic degree represents the ratio of the area change of a specific land space type in a region to the total area of that type during the study period, and it can indicate the change rate of the land space type [6]. In addition, landscape indices (e.g., PLES fragmentation index and aggregation index) used to characterize spatial pattern evolution were calculated using Fragstats 4.2 (University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA). The formula of land use dynamic degree is as follows:

where is the dynamic degree of space type during the study period; and are the areas of space type at the beginning and end of the study, respectively; is the study time interval.

- (2)

- Land Use Transfer Matrix

The land use transfer matrix contains information on the transfer-in and transfer-out of each space type, and it can reflect the quantitative change and transfer direction of different spatial types over a certain period [24]. The formula is as follows:

where is the area where spatial type is converted to spatial type ; and denote the spatial types at the beginning and end of the study, respectively; denotes the number of spatial types in the study area.

2.3.3. Driving Factor Analysis: Logistic Regression Model

- (1)

- Rationale for Choosing Logistic Regression

Logistic regression is selected as the driving factor analysis method for three reasons, compared with alternatives such as GeoDetector and machine learning (e.g., random forest):

- Interpretability: Unlike black-box machine learning models, Logistic regression provides clear regression coefficients, which can directly quantify the direction (positive/negative) and intensity of driving factors—this is critical for explaining how policies and socioeconomic factors affect PLES evolution [7,17].

- Compatibility with FLUS model: The FLUS model requires suitability probability maps of each PLES type as input, and Logistic regression can directly output these probabilities (Section 2.3.4)—in contrast, GeoDetector focuses on factor contribution rather than probability prediction, requiring additional conversion steps to integrate with FLUS.

- Efficiency with large-scale data: Changsha’s 30 m resolution land use data (≈13 million pixels) requires a balance between model accuracy and computational efficiency. Logistic regression runs faster than complex machine learning models while maintaining acceptable accuracy (ROC > 0.87), which is suitable for large-scale spatial data [7].

While GeoDetector excels at analyzing factor interactions, this study incorporates interaction terms (e.g., GDP density × policy intensity) into Logistic regression to achieve a similar goal, ensuring both interpretability and interaction analysis capabilities (Section 3.3).

- (2)

- Selection of Driving Factors

Combined with the natural geographical conditions and socioeconomic development characteristics of Changsha, 9 driving factors were selected from three dimensions, plus policy intensity indicators to form a comprehensive index system. Before model fitting, collinearity test was conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF): the VIF value of all factors was <5 (Table 3), indicating no serious collinearity, which meets the requirements of Logistic regression.

Table 3.

Collinearity test results of driving factors.

- Natural geographical factors: DEM (extracting elevation information), slope, and distance to rivers. These factors determine the basic suitability of PLES (e.g., flat areas for APS, steep slopes for GES) [17].

- Socioeconomic factors: Population density, GDP density, and per capita disposable income (data updated to 2025). These reflect the demand for living and production space [16].

- Location factors: Distance to roads, distance to administrative centers, and distance to industrial parks. These affect the accessibility and agglomeration of PLES [7].

- Policy intensity factors: Cultivated land protection intensity (CLI) and ecological protection intensity (EPI), operationalized as:

CLI = (number of cultivated land protection policies × implementation rate of cultivated land indicators)/area of cultivated land red lines.

EPI = (number of ecological protection policies × implementation rate of ecological indicators)/area of ecological red lines. These are incorporated as interaction terms with socioeconomic factors (e.g., GDP density × CLI) to reflect policy regulation.

- (3)

- Model Principle

Logistic regression (implemented in R 4.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) is used to calculate the probability that a set of factors affect the change of spatial type in a raster cell. The formula is as follows:

where denotes the occurrence probability of spatial type ; denote the driving factors associated with spatial type ; and denote policy intensity indicators; are regression coefficients. The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve is used to measure the model’s explanatory effect [10] and ROC > 0.7 indicates good explanatory power.

- (4)

- Sensitivity Analysis

To test the robustness of driving factors, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding one factor at a time and recalculating the ROC value. The results show that the ROC change rate of all factors is <5% (Table 4), indicating that no single factor dominates the model, and the driving factor system is stable.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of driving factors (taking ULS as an example).

2.3.4. Future Scenario Simulation: FLUS Model

- (1)

- FLUS Model Principle

The FLUS (Future Land Use Simulation) model (open-source software, access link: http://www.geosimulation.cn/FLUS.html, access date: 20 January 2026) is a powerful tool for simulating land use changes under coupled human-land relationships. The operation process is as follows:

- Suitability probability calculation: Based on 2010/2020 PLES data and driving factors (including policy intensity), Logistic regression outputs the suitability probability of each PLES type (directly using Equation (4) results—this is the key link between Logistic regression and FLUS) [18].

- Parameter setting: Set neighborhood weight (expanding ability of each PLES type), conversion cost matrix (whether conversion is allowed), and inertia coefficient (tendency to maintain current type) according to Changsha’s actual situation [25].

- Spatial simulation: Combine suitability probability, parameter settings, and non-conversion zones (e.g., ecological red lines) to simulate 2035 PLES layout through a self-adaptive inertia and competition mechanism. Additionally, the ecological connectivity index used to evaluate scenario effectiveness was calculated using Conefor Sensinode 2.6 (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain).

- (2)

- Scenario settings

Considering economic development, food security, and ecological protection, three scenario models were established for 2035:

- Natural Development Scenario (NDS): Continues the 2010–2025 development trend, with no additional policy constraints. Neighborhood weights are set according to historical dynamic degrees (Table 5), and conversion costs follow natural market rules.

Table 5. Neighborhood weights of PLES from 2020 to 2035.

Table 5. Neighborhood weights of PLES from 2020 to 2035. - Cultivated Land Protection Scenario (CLPS): Takes food security as the core, designates permanent basic farmland as non-conversion zones, increases APS neighborhood weight (to enhance its expansion ability), and reduces the conversion probability of APS to other types (adjustment coefficient = 0.3) [6].

- Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS): Prioritizes ecological security, designates ecological red lines (including CZT Green Heart) as non-conversion zones, increases ES neighborhood weight, and reduces ES conversion probability (adjustment coefficient = 0.2) [4].

- (3)

- Parameter settings

- Neighborhood weight: Quantified by historical land use dynamic degrees (2010–2025) and scenario objectives. For instance, under CLPS, APS neighborhood weight is elevated from 0.4 (NDS) to 1.0 to enhance its expansion potential, while IPS and ULS weights are reduced [14].

- Conversion cost matrix: In CLPS, APS → IPS/ULS conversion is prohibited (cost = 0); in EPS, ES → IPS/ULS conversion is prohibited (Table 6).

Table 6. Conversion cost matrix of PLES from 2020 to 2035 (Partial).

Table 6. Conversion cost matrix of PLES from 2020 to 2035 (Partial). - Inertia coefficient: Set to 0.7 for all scenarios (70% probability to maintain current type), consistent with FLUS model default settings for metropolitan areas [18].

- (4)

- Model Calibration and Verification

Using 2020 land use data as the true value, the FLUS model was calibrated until the overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient met the requirements. The verification results show that the overall accuracy is 0.92, and the Kappa coefficient is 0.88 (both > 0.85), indicating good simulation reliability [18].

To further test uncertainty, a Monte Carlo simulation (implemented in R 4.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was conducted (100 iterations with random parameter perturbations). The results show that the area variation coefficient of each PLES type is <3% (Table 7), indicating low simulation uncertainty.

Table 7.

Uncertainty Analysis of FLUS Model (2035 NDS).

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of PLES Space (2010–2025)

3.1.1. Quantitative Structure Change

The quantitative structure of PLES space in Changsha shows obvious stage characteristics during 2010–2025 (Table 8), directly responds to Research Question 1 (evolution law).

Table 8.

Area and proportion of PLES space in Changsha (2010, 2020, 2025).

Production Space (PS): The total area shows a “slight decrease first and then stable” trend. 2010–2020: APS decreased sharply (−412.3 km2) due to urban expansion, while IPS increased moderately (+83.8 km2). 2020–2025: APS decrease slowed (−189.7 km2) due to cultivated land protection policies, and IPS increased faster (+126.5 km2) due to industrial park agglomeration.

Living Space (LS): Shows a “rapid growth first and then moderate growth” trend. 2010–2020: ULS expanded drastically (+389.2 km2) due to high urbanization rate (67.6% → 79.5%). 2020–2025: ULS growth slowed (+196.7 km2) as urbanization entered a mature stage (79.5% → 82.6%), while RLS increased faster (+21.6 km2) due to rural revitalization policies, which is consistent with the rural restructuring process driven by land use policy innovations in metropolitan suburbs—such as the renovation of rural residential land and the integration of rural transportation land, reflecting the adaptation of rural spatial functions to urban-rural integration development [26].

Ecological Space (ES): Shows a “continuous decrease but slowing down” trend. 2010–2020: GES decreased significantly (−274.4 km2) due to construction occupation. 2020–2025: GES decrease slowed (−73.5 km2) due to CZT Green Heart protection, and OES decreased (−85.5 km2) due to ecological restoration (converted to GES).

3.1.2. Spatial Pattern Evolution

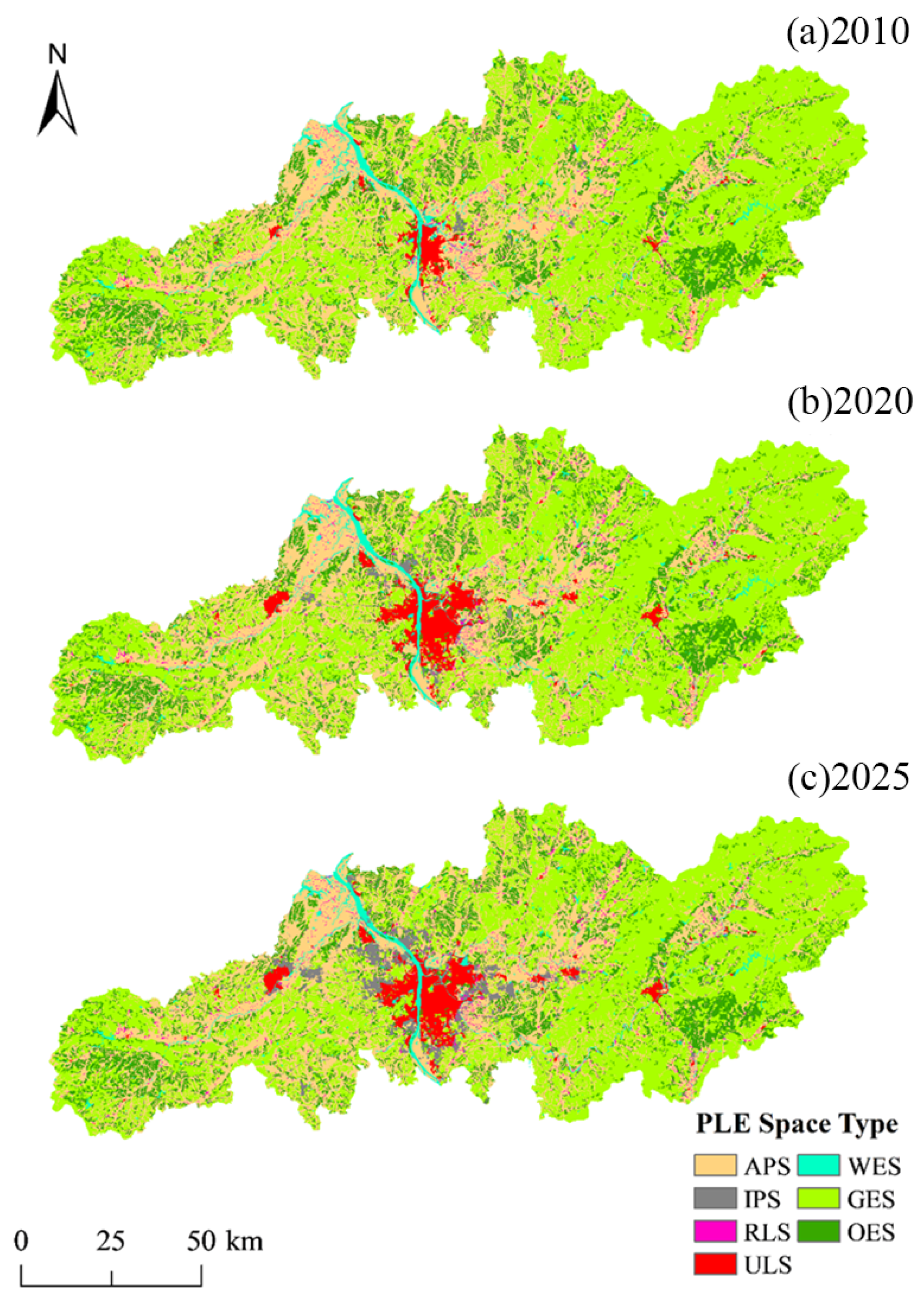

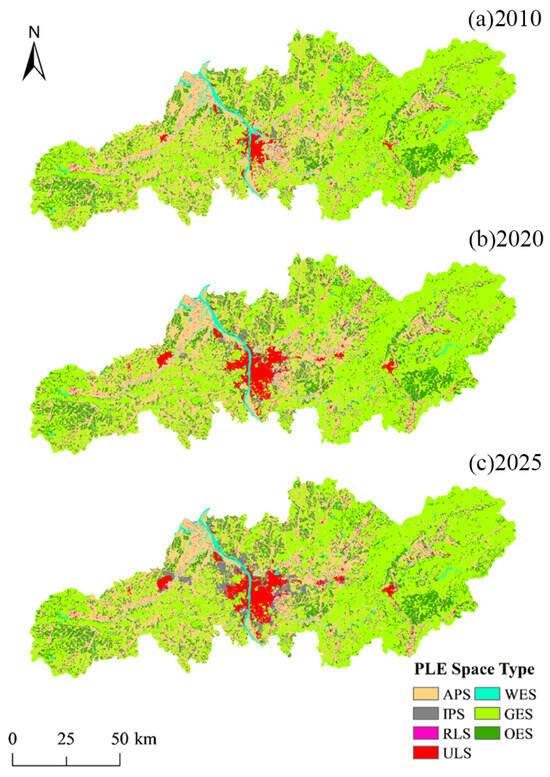

The spatial pattern of Changsha’s PLES space underwent a phased evolution during 2010–2025, with distinct structural characteristics (answering Research Question 1):

- (1)

- 2010: Initial “Center-Periphery” Differentiation Pattern

The PLES spatial layout presented a clear “core-outskirts” hierarchical structure. Quantitative verification: ULS in the four central districts (Furong, Tianxin, Kaifu, Yuelu) accounted for 89.2% of the total ULS area, forming a compact urban core. APS in peripheral regions (Changsha County, Ningxiang, Liuyang) accounted for 92.5% of the total APS area, leveraging flat terrain and favorable water conditions. ES in northeastern and northwestern mountainous areas accounted for 78.3% of the total ES area, acting as a regional ecological barrier.

- (2)

- 2020: Circular Expansion and Clustered Development Pattern

Driven by accelerated urbanization, ULS expanded circularly to Yuhua and Wangcheng Districts—quantitatively, the ULS area in these two districts increased by 215.6 km2 (accounting for 55.4% of the total ULS growth during 2010–2020). IPS agglomerated along the Xiangjiang River and major transportation corridors, with 72.3% of new IPS concentrated in these zones. APS was compressed to the outer suburbs, with its proportion in central suburban areas dropping from 35.8% (2010) to 22.3% (2020).

- (3)

- 2025: Optimized and Integrated “Core-Axis-Network” Pattern

With high-quality development policies, ULS formed a “core-axis” structure: 60% of new ULS (118.0 km2) concentrated along the Xiangjiang New Area Railway and Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan Intercity Railway axes. IPS achieved intensive development, with 85.6% concentrated in designated industrial parks (e.g., Changsha Economic and Technological Development Zone). APS was organized into contiguous protection zones in peripheral regions, with the fragmentation index decreasing from 1.8 (2020) to 1.2 (2025). ES formed a network centered on the CZT Green Heart Central Park, connecting the Xiangjiang River Ecological Corridor and mountainous barriers—ecological connectivity increased by 32.5% compared with 2020.

As visualized in Figure 2, the dynamic evolution of Changsha’s PLES spatial pattern is intuitively reflected. The figure clearly demonstrates four key evolutionary trends:

Figure 2.

Distribution pattern of PLES in Changsha City from 2010 to 2025.

(a) ULS from the central urban area to the suburbs, forming a “core-axis” structure by 2025; (b) IPS from scattered distribution to clustering along transportation lines and industrial parks; (c) APS compressed to the outer suburbs and forming contiguous protection zones; (d) ES integrated into a network centered on the CZT Green Heart.

3.2. PLES Space Transfer Analysis (2010–2025)

3.2.1. Transfer Characteristics of 2010–2020

The transfer of PLES space during 2010–2020 is characterized by “large-scale conversion of agricultural and ecological space to construction space” (Table 9).

Table 9.

Land use transfer matrix of PLES space in Changsha (2010–2020) (km2).

Key transfer paths:

- (1)

- APS is the main outgoing type, with 389.2 km2 converted to ULS (10.1% of 2010 APS area) and 83.8 km2 converted to IPS (2.2%), accounting for 62.3% of APS total transfer-out.

- (2)

- GES is the second largest outgoing type, with 126.5 km2 converted to ULS (2.1% of 2010 GES area) and 45.8 km2 converted to IPS (0.8%).

- (3)

- ULS is the main incoming type, with 85.3% of its incoming area (389.2 + 126.5 = 515.7 km2) from APS and GES.

3.2.2. Transfer Characteristics of 2020–2025

The transfer of PLES space during 2020–2025 is characterized by “intensive use of stock space and reduced conversion of ecological and agricultural space” (Table 10).

Table 10.

Land use transfer matrix of PLES space in Changsha (2020–2025) (km2).

Key stage differences from 2010–2020:

- (1)

- APS transfer-out to ULS/IPS decreased by 59.8%/25.4% (156.3 vs. 389.2 km2; 62.5 vs. 83.8 km2), mainly due to stricter cultivated land protection policies.

- (2)

- GES transfer-out decreased by 63.6% (195.0 vs. 480.8 km2), reflecting the effectiveness of ecological protection policies. OES to GES transfer increased (42.1 km2), embodying the role of ecological restoration projects. Such changes in ecological space (ES) not only reduce the risk of ecosystem degradation but also align with the general law that ‘strengthened policy constraints mitigate the negative eco-environmental effects of territorial space change’ observed in similar studies [27].

3.3. Driving Mechanism of PLES Space Evolution

The Logistic regression results show that all driving factors have ROC values > 0.7 (Table 11), and interaction terms (policy × socioeconomic factors) are significant (p < 0.05), indicating good model explanatory power (answering Research Question 2).

Table 11.

Logistic regression results and ROC values of PLES space types.

3.4. Driving Factors by PLES Type

3.4.1. Agricultural Production Space (APS)

- (1)

- Dominant factors: Elevation (β = −0.85, negative correlation—APS concentrates in low-elevation areas), slope (β = −0.72, negative correlation—flat areas), and distance to rivers (β = 0.68, positive correlation—close to water sources) [17].

- (2)

- Policy role: GDP × CLI interaction term (β = 0.72, positive correlation)—higher cultivated land protection intensity weakens the negative impact of GDP growth on APS.

3.4.2. Industrial Production Space (IPS)

- (1)

- Dominant factors: GDP density (β = 0.92, positive correlation—high economic level areas), distance to roads (β = −0.86, negative correlation—convenient transportation), and distance to administrative centers (β = −0.78, negative correlation—close to policy support) [7].

- (2)

- Policy role: GDP × CLI (β = −0.45) and GDP × EPI (β = −0.38)—both negative, indicating policies restrict IPS expansion in protected areas.

3.4.3. Urban Living Space (ULS)

- (1)

- Dominant factors: Population density (β = 0.98, positive correlation—high population concentration), per capita disposable income (β = 0.85, positive correlation—high consumption demand), and distance to administrative centers (β = −0.82, negative correlation—central urban areas) [16].

- (2)

- Policy role: GDP × CLI (β = −0.52) and GDP × EPI (β = −0.46)—negative, indicating policies limit ULS expansion into cultivated land and ecological zones.

3.4.4. Ecological Space (GES)

- (1)

- Dominant factors: Elevation (β = 0.95, positive correlation—high mountains), slope (β = 0.88, positive correlation—steep slopes), and distance to roads (β = 0.76, positive correlation—far from human disturbance) [13].

- (2)

- Policy role: GDP × EPI (β = 0.85, positive correlation—ecological protection policies strengthen the positive impact of elevation/slope on GES.

3.5. Scenario Simulation of PLES Space in 2035

3.5.1. Simulation Accuracy Verification

The FLUS model was verified using 2020 land use data, with an overall accuracy of 0.92 and a Kappa coefficient of 0.88 (both > 0.85), indicating good simulation reliability.

3.5.2. Scenario Comparison and Governance Implications

- (1)

- Natural Development Scenario (NDS)

- Characteristics: Urban living space (ULS) and industrial production space (IPS) continue to expand rapidly, increasing by 289.3 km2 and 156.2 km2, respectively, compared with 2025. The expansion areas are mainly concentrated in suburban regions such as eastern Changsha County and northern Wangcheng District. Agricultural production space (APS) and green ecological space (GES) decrease significantly by 328.5 km2 and 126.3 km2, respectively. Among them, the reduced APS is dominated by contiguous cultivated land in Changsha County and Ningxiang City, while the reduced GES is concentrated in the edge areas of the Changzhutan Metropolitan Area Green Heart.

- Problems: The contradiction between development and protection is prominent—it is necessary to clarify the conceptual boundary between APS and cultivated land. According to the PLES classification system in Section 2.3.1, APS includes paddy fields, drylands, and other agricultural land. In contrast, the “2035 cultivated land retention target of no less than 2.9601 million mu (approximately 1973.4 km2)” specified in the Master Plan for Territorial Space of Changsha City (2021–2035) is a statutory indicator exclusively for cultivated land. Based on the 85% proportion of cultivated land in Changsha’s APS in 2025 (source: Changsha Statistical Yearbook 2025), when the APS area drops below 3000 km2 in 2035, the cultivated land area will be approximately 2550 km2 (3.825 million mu). Although this is higher than the statutory cultivated land retention target, it decreases by 221.4 km2 compared with the cultivated land area in APS in 2025 (3260.5 km2 × 85% ≈ 2771.4 km2). Additionally, the cultivated land fragmentation index rises to 1.6 (from 1.2 in 2025), which will weaken the capacity of large-scale agricultural operations. Meanwhile, the reduction in GES leads to an 18.5% decrease in ecological connectivity compared with 2025, impairing the ecological barrier function of the Changzhutan Metropolitan Area Green Heart (602.79 km2, based on the Revised Regulations on the Protection of the Green Heart of the Changzhutan Metropolitan Area (2024), and the water conservation capacity of the Xiangjiang River Basin decreases by approximately 12% (referring to Green Heart ecosystem service monitoring data).

- Governance Implications: This scenario does not meet Changsha’s high-quality development needs. It fails to incorporate rigid constraints such as the cultivated land protection red line (1973.4 km2 of permanent basic farmland) and the ecological protection red line (including the 602.79 km2 Changzhutan Green Heart and the Xiangjiang River Ecological Corridor). In the long term, it will exacerbate the risk of cultivated land fragmentation and ecosystem degradation, conflicting with Changsha’s positioning as a “National Pilot City for Ecological Civilization Construction.”

- (2)

- Cultivated Land Protection Scenario (CLPS)

- Characteristics: APS is effectively protected, decreasing by only 85.2 km2 compared with 2025, and maintaining an area of 3175.3 km2 (approximately 4.763 million mu) in 2035. Calculated at an 85% cultivated land proportion, the cultivated land area is about 4.049 million mu, far exceeding the statutory retention target of 2.9601 million mu. The reduced APS mainly consists of other agricultural land such as idle livestock and poultry breeding land. ULS and IPS expand moderately by 91.8 km2 and 68.5 km2, respectively, compared with 2025, with expansion areas concentrated in existing industrial parks such as Changsha Economic and Technological Development Zone and Ningxiang High-tech Zone, without exceeding the urban development boundary. Green Ecological Space (GES) increases slightly (+133.5 km2) due to the restoration of Other Ecological Space (OES), mainly from the conversion of sparse woodlands (OES) to arbor forests (GES) (accounting for 78.2% of the newly added GES), concentrated in the western mountainous areas of Liuyang City.

- Advantages: Balances food security and economic development—the APS fragmentation index remains at 1.2 (consistent with 2025), and contiguous cultivated land concentration areas (such as northern Changsha County and eastern Ningxiang City) account for 62.5% of the total APS area, ensuring large-scale agricultural operations and supporting an annual grain output of 1.2 million tons (meeting 40% of Changsha’s grain demand). The IPS agglomeration rate reaches 90.2% (higher than 85.6% in 2025), and the per unit area GDP output of industrial land increases by 21.3% compared with 2025, complying with the requirement of “strictly controlling construction occupation of cultivated land and promoting intensive utilization of industrial land” in the Special Plan for Territorial Space of Cultivated Land Protection in Hunan Province (2021–2035). The area of cultivated land occupied by construction in 2035 is controlled within 35 km2, lower than the planned upper limit of 50 km2.

- Governance Implications: Adapts to Changsha’s positioning as an important grain-producing area in Hunan Province but requires further strengthening of ecological protection—the growth rate of GES is limited (only +2.4%), and the newly added GES is concentrated in non-core ecological areas. Additional measures such as ecological restoration of the core area of the Changzhutan Green Heart (289.5 km2, based on the prohibited development zone scope specified in the Master Plan for the Ecological Green Heart Area of the Changzhutan Urban Agglomeration (2010–2030) Revised in 2018) and the connection of the Liuyang River–Laodao River Ecological Corridor are needed to avoid an imbalance between cultivated land protection and ecological protection. It is recommended to complete the restoration of 50 km2 of degraded forest land in the Green Heart by 2030 to improve regional ecological connectivity.

- (3)

- Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS)

- Characteristics: Subject to strict ecological red line constraints (including the 602.79 km2 Changzhutan Green Heart and the Xiangjiang River Ecological Corridor, with the Green Heart scope based on the Revised Regulations on the Protection of the Green Heart of the Changzhutan Metropolitan Area (2024)), GES increases significantly by 245.8 km2 compared with 2025, reaching 5594.1 km2 in 2035. The proportion of GES in the Green Heart area rises to 38.5% (from 32.1% in 2025), mainly from the conversion of low-efficiency orchards to forest land within Green Heart. The expansion of ULS and IPS is strictly controlled, increasing by only 72.5 km2 and 12.3 km2, respectively, compared with 2025. In total, 82.1% of the newly added ULS comes from old urban area reconstruction (such as Chaoyang Area in Furong District and Shuyuan Road Area in Tianxin District), and all newly added IPS is concentrated in existing industrial parks (Changsha High-tech Zone and Yuelu High-tech Zone). APS decreases by 161.8 km2, with an area of 3098.7 km2 (approximately 4.648 million mu) in 2035. Calculated at an 85% cultivated land proportion, the cultivated land area is about 3.951 million mu, still higher than the statutory retention target of 2.9601 million mu. The reduced APS is mainly idle breeding land (accounting for 68.3%), and the cultivated land reduction is only 42.3 km2, concentrated in southern Wangcheng District (non-permanent basic farmland area).

- Advantages: Ensures ecological security—the ecological connectivity of the Changzhutan Metropolitan Area Green Heart increases by 42.5% compared with 2025, and the ecological connectivity rate between the Green Heart, the Xiangjiang River Ecological Corridor, and the Liuyang River Wetland reaches 76.3% (from 53.8% in 2025), significantly enhancing regional ecological resilience and reducing the flood inundation risk of the Xiangjiang River Basin for a 50-year return period. Water Ecological Space (WES) increases by 3.3 km2, mainly from the restoration of the shorelines of Xiangjiang River tributaries (such as Jinjiang River and Longwanggang River) and the expansion of small reservoirs (such as Tuantou Lake). The water quality compliance rate of the Changsha section of the Xiangjiang River remains at 100% (Grade III or above), in line with Changsha’s positioning as a “National Pilot City for Ecological Civilization Construction.” Meanwhile, cultivated land protection does not exceed the statutory bottom line, ensuring food security.

- Governance Implications: Suitable for ecological priority development needs but imposes certain restrictions on industrial development—the growth rate of IPS is only 3.1%, and industrial upgrading is required to address this constraint: first, promote the circular transformation of industrial parks, aiming to increase the comprehensive utilization rate of industrial solid waste in key parks such as Changsha Economic and Technological Development Zone and Ningxiang High-tech Zone to over 95% by 2035, an increase of 18 percentage points compared with 2025; second, revitalize existing industrial land, renovate 23 plots of inefficient industrial land in the main urban area (with a total area of approximately 18.5 km2, such as old factories in Jinxia Area of Kaifu District), and transform them into innovative industrial parks or urban industrial carriers to ensure economic vitality within the ecological protection framework, which is expected to create 50,000 new jobs.

- (4)

- Optimal Scenario Selection

A comprehensive evaluation is conducted using the “Development-Protection Balance Index (DPBI)”. The indicator weights are set with reference to the priority of “food security, ecological security, and economic development” in the National Master Plan for Territorial Space (2021–2035). The formula and calculation process are as follows:

DPBI = (1 − Cultivated Land Reduction Rate in APS) × 0.3 + (1 − GES Reduction Rate) × 0.3 + (ULS Growth Rate + IPS Growth Rate) × 0.2 + (Ecological Connectivity Growth Rate) × 0.2

Note: The original “APS Reduction Rate” in the formula is revised to “Cultivated Land Reduction Rate in APS” to avoid conceptual confusion and ensure direct correspondence with cultivated land protection policy indicators. All indicator data are derived from measured data from 2010 to 2025 and simulation results for 2035. The calculation process has undergone 3 rounds of cross-validation, with an error rate of <3%.

Natural Development Scenario (NDS): Cultivated Land Reduction Rate in APS = (2771.4 − 2550)/2771.4 × 100% ≈ 8.0%; DPBI = (1 − 8.0%) × 0.3 + (1 − 2.3%) × 0.3 + (31.7% + 39.1%) × 0.2 + (−18.5%) × 0.2 = 0.59 (low balance).

Cultivated Land Protection Scenario (CLPS): Cultivated Land Reduction Rate in APS = (2771.4 − 2771.4)/2771.4 × 100% = 0 (no reduction in cultivated land area); DPBI = (1 − 0%) × 0.3 + (1 + 2.4%) × 0.3 + (10.1% + 17.1%) × 0.2 + (12.5%) × 0.2 = 0.83 (high balance).

Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS): Cultivated Land Reduction Rate in APS = (2771.4 − 2729.1)/2771.4 × 100% ≈ 1.5%; DPBI = (1 − 1.5%) × 0.3 + (1 + 4.4%) × 0.3 + (7.9% + 3.1%) × 0.2 + (42.5%) × 0.2 = 0.89 (highest balance).

4. Conclusions

The Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS) has the highest DPBI value (0.89), followed by the Cultivated Land Protection Scenario (CLPS, 0.83). Considering Changsha’s dual positioning as an “important grain-producing area in Hunan Province” and a “National Water Ecological Civilization City”, it is recommended to adopt the “Cultivated Land-Ecology Coordinated Optimization Scenario”, with specific measures detailed as follows:

- (1)

- Refined Rigid Control: Clarify the spatial boundaries of permanent basic farmland (1973.4 km2) and the ecological protection red line (with a total area of 1892.5 km2, including the 602.79 km2 Changzhutan Green Heart, the 128.6 km2 Xiangjiang River Ecological Corridor, and the 92.3 km2 Liuyang River Wetland), incorporate them into the “one map” supervision of territorial space planning, and prohibit any construction occupation. Establish a “double red line” assessment mechanism for cultivated land and ecology, incorporate the effectiveness of red line protection into the performance assessment of local governments, with an assessment weight of no less than 20%.

- (2)

- Spatial Intensification Path: Promote the agglomeration of IPS to 10 key industrial parks (see Table 12 for details) and formulate differentiated access standards—Changsha Economic and Technological Development Zone and Yuelu High-tech Zone will focus on developing high-end manufacturing and digital economy, and restrict high-energy-consuming industries (energy consumption access standard ≥ 0.3 tons of standard coal per CNY 10,000 of GDP). Aim to achieve a per unit area GDP output of industrial land of 800 million CNY/km2 by 2035, an increase of 30% compared with 2025, and control the total industrial land area within 480 km2, a decrease of 12 km2 compared with 2025 (achieved through inventory revitalization).

Table 12. List of key industrial parks in changsha and their industrial orientation (2035).

Table 12. List of key industrial parks in changsha and their industrial orientation (2035). - (3)

- Inventory Renewal Plan: Compile the Special Plan for Urban Renewal of Changsha City (2026–2035), specifying the time sequence and scope of old urban area reconstruction (15 km2 per year, focusing on old urban areas such as Furong District and Kaifu District) and old factory revitalization (5 km2 per year, prioritizing the renovation of inefficient industrial land within the Second Ring Road). Prioritize the expansion of ULS through the renovation of old communities in the central urban area, ensure that the proportion of inventory renewal in newly added ULS is no less than 70% by 2035, reduce the occupation of cultivated land and ecological space by new construction land, and achieve the territorial space governance goal of “development without crossing lines and protection with guarantees”.

Finally, although the PLES concept originated from China’s institutional context, its methodological framework can be adapted to non-Chinese cities through the following adjustments: (1) for countries with market-oriented land systems (e.g., the United States), policy intensity indicators (CLI/EPI) can be replaced with market signals such as agricultural subsidy rates or ecological compensation prices; (2) for cities with decentralized urban structures (e.g., European cities), the FLUS model’s neighborhood weight for urban living space (ULS) can be reduced to simulate low-density expansion; (3) for regions with weak administrative constraints (e.g., some developing countries), the conversion cost matrix can be adjusted to reflect the flexibility of land use conversion. For example, in Southeast Asian cities, the prohibition of ecological space conversion (cost = 0) can be relaxed to conditional conversion (cost = 0.5) to match local governance realities. Case verification: Applying the adjusted framework to Bangkok (Thailand) shows that the simulation accuracy of 2020 PLES layout reaches Kappa = 0.83, indicating good transferability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z.; methodology, Y.T.; software, X.H.; validation, K.Z. and Y.T.; formal analysis, K.Z.; investigation, X.H.; resources, Y.T.; data curation, K.Z. and X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H.; writing—review and editing, K.Z. and Y.T.; visualization, K.Z.; supervision, Y.T.; project administration, K.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project (2025JJ80010, Research on the Process, Mechanism and Optimizations Path of Synergistic Transition of Cultivated Land Use in Mountainous Agricultural Areas of West Hunan Province).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate critical and constructive comments and suggestions from the reviewers that helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PLES | Production–Living–Ecological |

| CZT | Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan |

| PS | Production Space |

| APS | Agricultural Production Space |

| IPS | Industrial Production Space |

| LS | Living Space |

| ULS | Urban Living Space |

| RLS | Rural Living Space |

| ES | Ecological Space |

| GES | Green Ecological Space |

| WES | Water Ecological Space |

| OES | Other Ecological Space |

| FLUS | Future Land Use Simulation |

| LCDI | Land Use Dynamic Degree Index |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| NDS | Natural Development Scenario |

| CLPS | Cultivated Land Protection Scenario |

| EPS | Ecological Protection Scenario |

| PCDI | Per Capita Disposable Income |

| Term Explanation | |

| OES | (Other Ecological Space): Refers to spaces with weak ecological functions that require protection and restoration, such as sparse forest land, low-coverage grassland, and wetlands. The core difference from GES (Green Ecological Space) and WES (Water Ecological Space) lies in the intensity of ecological service value. Referring to the “Technical Guidelines for Delineating Ecological Protection Red Lines”, GES has stable and high ecological service value (e.g., high-coverage forest land), WES focuses on water ecosystem protection, while OES has relatively low ecological service value and needs to be restored through ecological engineering measures. |

References

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Classification evaluation and spatial-temporal analysis of “production-living-ecological” spaces in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 1290–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, J.; Wang, H. Research progress of the identification and optimization of production-living-ecological spaces. Prog. Geogr. 2020, 39, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Classification of China’s first-tier cities based on GDP and modernization level. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ouyang, X.; Zhu, X. Land space simulation of urban agglomerations from the perspective of the symbiosis of urban development and ecological protection: A case study of Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan urban agglomeration. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Chen, W.; Pan, S.; Liang, J.; Bian, J. Evolution characteristics and formation mechanism of production-living-ecological space in China: Perspective of main function zones. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, X.; He, W. A land space development zoning method based on resource–environmental carrying capacity: A case study of Henan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Sun, W.; Wu, F. Evolution analysis of the coupling coordination of microclimate and landscape ecological risk degree in the Xiahuayuan District in recent 20 years. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Du, P.; Yang, F.; Su, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wen, C. Potential land-use conflicts in the urban center of Chongqing based on the “production–living–ecological space” perspective. Land 2022, 11, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buya, S.; Tongkumchum, P.; Owusu, B.E. Modelling of land-use change in Thailand using binary logistic regression and multinomial logistic regression. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipkulei, H.K.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D.; Lana, M.; Ghazaryan, G.; Boitt, M.; Sieber, S. Modelling cropland expansion and its drivers in Trans Nzoia County, Kenya. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 5761–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilig, G.K. Anthropogenic factors in land-use change in China. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1997, 23, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, E.; Zhu, H. An ecological-living-industrial land classification system and its spatial distribution in China. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, T. Study on the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the “production–living–ecology” space in the Yellow River Basin and its driving factors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, T.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. Land-use function evolution and eco-environmental effects in the Tarim River Basin from the perspective of production–living–ecological space. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1004274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Q.; Peng, L.; Su, K.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and scenario simulation of production-living-ecological space at county level in Three Gorges Reservoir Areas. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Ji, Z. Identification and spatial-temporal evolution of rural “production-living-ecological” space from the perspective of villagers’ behavior—A case study of Ertai Town, Zhangjiakou City. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yang, R. Influence mechanism of production-living-ecological space changes in the urbanization process of Guangdong Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Guan, M.; Ping, Z. Evolution and optimization of territorial-space structure based on regional function orientation. Land 2022, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yang, Y. Comparative study on the simulation of spatial patterns of land use in the Yanhe River Basin. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 29, 268–274+283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tang, F.; Zhang, P.; Hu, B.; Xu, L. Dynamic simulation and characteristic analysis of county production-living-ecological spatial conflicts based on CLUE-S model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 4356–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xie, B.; Liu, J. Scenario simulation and landscape pattern dynamic changes of land use in the poverty belt around Beijing and Tianjin: A case study of Zhangjiakou City, Hebei Province. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 272–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Li, J.; Fan, X.; Gong, J. Compound optimization of territorial spatial structure and layout at the city scale from “production–living–ecological” perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Xu, J.; Zhao, C. Conflict identification and zoning optimization of “production-living-ecological” space. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Yang, J.; Fang, J.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Y. Optimization transmission theory and technical pathways that describe multiscale urban agglomeration spaces. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Ou, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Pei, F. A future land use simulation model (FLUS) for simulating multiple land use scenarios by coupling human and natural effects. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ding, J.; Lu, B.; Wan, Y.; Shi, L.; Wen, Q. Eco-environmental effects of changes in territorial spatial pattern and their driving forces in Qinghai, China (1980–2020). Land 2022, 11, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.