Abstract

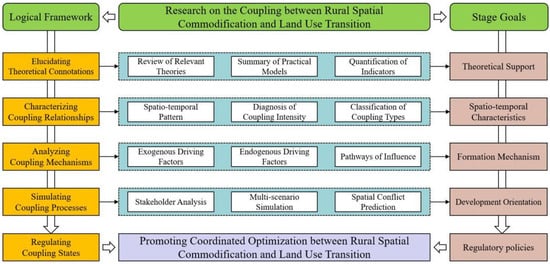

Rural spatial commodification serves as a vital pathway toward comprehensive rural revitalization. Its development is closely intertwined with land use transition, with each process exerting reciprocal influence on the other. Research on the coupling between these two systems has emerged as a cutting-edge interdisciplinary field bridging rural geography and land system science. Based on a systematic review of research advances in rural spatial commodification and land use transition, this paper summarizes the existing gaps in the literature and attempts to construct a coupling framework integrating rural spatial commodification and land use transition. The findings indicate that, although the academic community has amassed a substantial body of research on rural spatial commodification, land use transition, and their coupled relationship with rural transformation, several gaps persist. These encompass the absence of systematic indicator frameworks and quantitative validation methods for rural spatial commodification, insufficient exploration into the coupling mechanisms between rural spatial commodification and land use transition, and a notable scarcity of empirical studies examining land use optimization driven by rural spatial commodification. Future research on the coupling between rural spatial commodification and land use transition should follow the logical framework of “elucidating theoretical connotations, characterizing coupling relationships, analyzing coupling mechanisms, simulating coupling processes, and regulating coupling states”. It is essential to strengthen the interdisciplinary integration of rural geography and land system science, thereby providing scientific guidance for the allocation of resources in rural areas and the implementation of rural revitalization practices.

1. Introduction

Under the rapid advancement of industrialization and urbanization, along with sustained improvements in economic development and quality of life, the conceptual paradigm and perceptual imagery of rural areas have undergone a fundamental transformation. These areas have shifted from being associated with “poverty and backwardness” to embodying notions of “tranquility and leisure” [1]. This reconfigured rurality has progressively emerged as a crucial spatial domain for urban residents’ recreational and tourism activities. In economically developed regions, novel rural consumption patterns and innovative formats—including agritourism experiences, wellness-oriented homestays, and ecotourism initiatives—are now proliferating as pioneering models of rural revitalization.

Concurrently, guided by national strategies, the continuous influx of urban elements into rural areas has triggered a significant shift. This shift is characterized by a relative decline in agricultural production functions and a rise in non-material consumption capacities within rural spaces, ultimately steering rural development from a traditional “productivist” model toward a “post-productivist” and multifunctional paradigm [1]. Against this backdrop, both tangible assets (such as land, homestays, agricultural products, and natural landscapes) and intangible resources (including rurality, pastoral imagery, cultural heritage, and farming experiences) have increasingly been commodified [2]. This process is coalescing into the rapidly evolving phenomenon of rural spatial commodification. This transition reflects a global trend in rural restructuring, suggesting that rural spatial commodification holds universal relevance for sustainable rural development worldwide, beyond the Chinese context.

Rural spatial commodification, an emerging concept in rural geography, refers to the process by which urban capital transforms both tangible and intangible rural land-based resources into marketable commodities. This dynamic facilitates rural socio-economic transformation and leads to the reproduction of rural space [3]. The manifestations of rural spatial commodification are diverse, and its practical models complex. Given that land serves as both a core component and the fundamental spatial carrier for this process, the trajectory of commodification is intricately linked to the configuration of land resources. Scientifically conceived land-use configurations provide critical support for the diversified and synergistic development of various rural spatial commodification types, thereby making it indispensable for fostering coordinated and sustainable progress across rural economic, social, and ecological domains. Conversely, the misallocation of land resources not only exacerbates spatial conflicts among these commodification models but can also precipitate a protracted transformation of rural functions and a marked deficiency in endogenous drivers for revitalization.

Currently, the misallocation of land use functions, compounded by disordered spatial layouts, constrains the functional expansion and transformation of rural territories [4,5]. A salient paradox has emerged: while rural spatial commodification accelerates, it faces a critical constraint from vast tracts of inefficient and idle land that remain challenging to revitalize. It is foreseeable that the tension between rural spatial commodification and land resource allocation will persist for the future. This pressing reality necessitates the urgent development of a coupled framework integrating commodification with land use transition, alongside a comprehensive investigation into their interactive dynamics.

Hence, this paper systematically reviews extant research on rural spatial commodification and land use transition, synthesizes its limitations, and proposes a coupled framework structured around: elucidating theoretical connotations, characterizing coupling relationships, analyzing coupling mechanisms, simulating coupling processes, and regulating coupling states. In contrast to prior work, the study’s principal contributions are twofold: (1) a systematic synthesis of the literature, and (2) the innovative employment of “coupling” as an integrative methodological nexus. This framework is designed to advance interdisciplinary dialogue between rural geography and land system science, with the aim of guiding rural resource allocation and supporting revitalization practices.

2. Research Progress on Rural Spatial Commodification and Land Use Transition

Rural spatial commodification is an emerging and still nascent concept in rural geography. Current scholarship primarily focuses on its conceptual definition, typological classification, underlying processes, and socio-spatial impacts, while the coupling between rural spatial commodification and land use transition remains largely underexplored. Nevertheless, as a phenomenon derived from rural transformation, rural spatial commodification is inherently situated within this broader research domain. Accordingly, this review structures its literature survey around three core themes: rural spatial commodification, land use transition, and the coupled research on rural transformation and land use transition.

2.1. Rural Spatial Commodification and Its Associated Research Trajectories

2.1.1. The Conceptual Connotation of Rural Spatial Commodification

The study of rural spatial commodification originates in the functional transformation of rural space. Since the 1970s, Western developed nations have witnessed the emergence of significant social phenomena such as counter-urbanization, rural gentrification, and the deagrarianization of the rural economy [6]. While the agricultural function of rural spaces has progressively diminished, their roles in providing recreation, tourism, and cultural experiences have concurrently gained prominence. Driven by urban-derived elements such as population and capital, the countryside has thus completed an evolutionary trajectory from a “productivist” to a “post-productivist” and ultimately a multifunctional paradigm [7,8]. Under this evolving context, rural geographers in the 1990s introduced the concept of “rural spatial commodification” to characterize the nascent phenomenon wherein rural development shifted from a productivist economy toward a consumption-based economy. The British scholar Paul Cloke was instrumental in pioneering this conceptualization, defining the commodification of rural areas as “the process of developing rural environmental resources to satisfy contemporary consumption demands.” He authoritatively contended that the countryside had entered an era of “pay as you enter” accessibility [3].

Upon entering the 21st century, Western scholars represented by Woods and Perkins initiated more profound theoretical deliberations on the conceptual dimensions of rural spatial commodification. Woods posited that its essence lies in employing diversified modalities to facilitate the marketization of rural “commodities,” thereby achieving the fundamental objective of transacting rural resources within economic systems [9]. Perkins conceptualizes rural spatial commodification as a dynamic negotiation process among residents, producers, and tourists during the transition to a consumption-oriented economy [10]. The Japanese scholar Toshio introduced the concept of “rurality” to delineate the commodification process of rural elements. He theorized that rurality, through its material manifestations, constructs immaterial marketing attributes which strategically align with consumer imaginaries. This alignment endows rurality with significant exchange value, enabling its continual reconfiguration and repeated marketization [11]. Marsden further theorized a dual-scale analytical framework, positing that micro-level rural spatial commodification embodies processes where local actors navigate strategies of resistance, capital accumulation, and development. Conversely, macro-level commodification manifests the operational logics and patterns of capital as they become embedded within local contexts [12].

These later conceptualizations significantly refine and concretize Cloke’s earlier foundational work. In recent years, research on rural spatial commodification has gradually emerged in China. Scholars there have largely built upon these aforementioned perspectives while adapting them to the local context through modification and expansion. These adaptations encompass dimensions such as resource and environmental development, the interplay of power and capital, collective action and interest negotiation, as well as functional and economic restructuring [13,14]. Overall, research in the Chinese context emphasizes state-led initiatives within the collective ownership framework, devoting greater analytical attention to the interplay between national strategies and local implementation. In contrast, international scholarship on this phenomenon tends to focus more on the tensions between market forces and social movements.

2.1.2. The Typological Frameworks of Rural Spatial Commodification

To achieve a more profound understanding of this abstract concept, scholars have drawn upon empirical investigations across diverse regions to develop distinct typologies of rural spatial commodification from multiple analytical perspectives. Woods categorized rural spatial commodification into five distinct types: tourism activities and real estate investment, the repackaging of rural heritage, the construction of fictionalized rural landscapes, embodied rural experiences, and the marketing of agricultural products [9,15]. Based on rural practices in the UK, Perkins proposed that rural spatial commodification primarily encompasses four forms: traditional agriculture and horticultural products, new types of agricultural and horticultural products, counter-urbanization and rural gentrification, as well as leisure farming and rural tourism [10].

Furthermore, advocating for rural environmental conservation and cultural continuity, Akira refined the frameworks proposed by Woods and Perkins through empirical research in Japan, categorizing rural spatial commodification into: (Traditional/New) agricultural and aquatic product supply; consumption of rural space through counter-urbanization; rural leisure and tourism activities; and activities that enhance quality of life by preserving and managing natural environments and cultural landscapes, as well as recognizing and perpetuating traditional rural culture and folk customs [16]. Meanwhile, conceptualizes rural spatial commodification as a multifaceted phenomenon encompassing the entire transition of rural space—from its productive functions, through its consumption-oriented uses, to its ultimate conservation [17]. Building upon the framework of three-sector industry classification, the Chinese scholar Su Kangchuan has systematically categorized rural spatial commodification in China into five distinct types: land element commodification, agricultural product commodification, rural industrial commodification, rural tourism commodification, and rural trade commodification [2].

Despite the complexity and diversity of rural spatial commodification typologies, rural tourism stands out as the most paradigmatic and extensively studied modality. This prominence stems from its unique capacity to engage simultaneously with rural landscapes, cultural heritage, and lived experiences, thereby supporting the critical transition of rural space along the production-consumption-conservation continuum.

2.1.3. The Process Mechanism of Rural Spatial Commodification

The process of rural spatial commodification can be conceptualized across macro and micro dimensions, with the macro perspective emphasizing the historical trajectory of this transformation through the lens of divergent socio-economic developmental stages [18]. Chinese scholar Wang Pengfei, contextualizing his analysis within the trajectory of agricultural production mode transitions, has delineated the commodification of rural space in China into three distinct historical phases: the pre-1978 period (characterized by productivism under the “Grain as the Key Link” policy), the 1978–2005 era (marked by productivism within the framework of Reform and Opening-up), and the post-2005 period (defined by the progressive emergence of agricultural multifunctionality) [19]. At the micro level, the analysis of rural spatial commodification primarily relies on long-term observations of representative cases to decipher its developmental and evolutionary trajectory. Building upon this micro-level analytical framework, Canadian geographer Mitchell has conceptualized the commodification process in rural historic communities as progressing through six distinct stages: pre-commodification, initial commodification, advanced commodification, initial destruction, advanced destruction, and post-destruction [20].

Based on the established understanding of rural spatial commodification processes, scholarly inquiry has progressively extended to examining their underlying driving mechanisms, with a predominant emphasis placed on the pivotal role of capital accumulation as a primary catalyst. As Day critically examines, the sustained infusion of capital into rural territories ultimately culminates in the commodification of these spaces [21]. Gregory further contends that the penetration of urban capital fundamentally reconstitutes rural spatial configurations and social relations, thereby accelerating the commodification process [22]. Marden’s analysis elevates this understanding to the macro level, framing rural spatial commodification as the localized manifestation of broader capital operation logics and patterns [12]. Complementing this, Brenner argues that rapid tourism development transforms rural areas into consumption and recreational spaces, where capital mobility actively facilitates their commodification [23].

Chinese scholars, however, posit that the interplay of political power and capital constitutes a critical determinant shaping the trajectory of rural spatial commodification. Fan Lihui elucidates the dual role of the state as both driver and regulator in the process of rural spatial commodification. Specifically, she conceptualizes tourism-oriented commodification as an interactive process predicated upon distinctive resources and tourist flows, synergistically shaped by the core forces of governmental power and corporate capital [14]. Furthermore, her analytical framework identifies location, capital, power, innovation, and disruption as pivotal drivers conditioning agrarian rural spatial commodification [24].

2.1.4. The Impact Effect of Rural Spatial Commodification

The impact of rural spatial commodification manifests through both positive and negative dimensions, with scholarly attention predominantly focused on its constructive aspects. A prevailing academic consensus positions this commodification as a significant form of rural restructuring, functioning as a catalytic mechanism that drives socio-economic transformation across demographic, spatial, industrial, cultural, and institutional spheres [25,26,27,28]. As Mitchell posits, the commodification of rural cultural heritage serves to enhance systemic resilience in rural areas through the establishment of diversified livelihood systems and market-oriented institutions, thereby strengthening their capacity to withstand external shocks [29]. Fan Lihui systematically synthesized the multidimensional effects of rural spatial commodification, articulating its manifestations through resource innovation, landscape renewal, functional diversification of space, livelihood channel pluralization, and enhanced social and human habitats [14].

Indeed, the academic discourse has progressively acknowledged the adverse ramifications stemming from the excessive commodification of rural spaces in recent years. Since Mitchell’s seminal introduction of the “creative destruction” model in 1998, this framework has provided a critical theoretical lens for interpreting the complete trajectory of rural spatial commodification—from its emergence and development to its destructive phases—while simultaneously illuminating resultant challenges including landscape degradation and the erosion of placeness and authenticity [20]. The “creative destruction” effect inherent to rural spatial commodification has gained widespread scholarly recognition. In applying this theoretical framework to empirical case studies, researchers have observed that excessive commodification not only degrades primordial landscapes but also, through the sustained presence of substantial non-local populations, catalyzes the alienation of indigenous villagers’ place-based identity.

Nevertheless, a growing scholarly voice cautions against rigid adherence to the “creative destruction” paradigm in rural spatial commodification, advocating instead for greater academic attention to its potential for “creative enhancement”—a conceptualization emphasizing the transformative capacity of commodification to reconfigure rural spaces while potentially strengthening socio-ecological resilience and generating renewed value [30,31,32].

2.2. Land Use Transition and Its Associated Research Trajectories

2.2.1. The Connotation of Land Use Transition

The conceptual foundation of land use transition traces its origins to Mather’s Forest Transition Theory [33,34], with its earliest empirical application materializing in Walker’s seminal 1987 analysis of deforestation patterns in less developed countries [35]. The first substantive scholarly delineation of land use transition within geographical discourse was established by Grainger, a human geographer at the University of Leeds. Inspired by the Forest Transition Theory, Grainger conceptualizes land use transition as characterizing the shift in national land use morphology throughout socio-economic development processes. He further defines national land use morphology as the composite configuration of a nation’s land use categories and natural vegetation cover at a specific temporal juncture, quantitatively representable through land use structure matrices [36]. Following Grainger’s seminal 1995 conceptualization of land use transition through the lens of morphological change, this research domain has garnered substantial scholarly attention across European and North American academic circles.

The early 21st century witnessed the introduction of the “land use transition” framework into Chinese academic discourse by scholar Long Hualou [37]. Recognized as both a significant manifestation of Land Use and Cover Change (LUCC) and an innovative analytical approach that integrates temporal dimensions and historical contexts of socio-environmental change [38], land use transition research has been incorporated as a core scientific agenda within the Global Land Project. Since its introduction to China, this conceptual framework has progressively integrated with critical land use management challenges, expanding into research domains concerning cultivated land utilization transitions and urban–rural construction land transformations. This scholarly evolution has captured significant attention from both policy-making circles and theoretical communities, gradually coalescing into a distinctive theory of land use transition [39,40,41,42].

The conceptual core of land use transition posits that land use morphology undergoes directional shifts in correspondence with socio-economic development stages [43,44]. It represents a distinct, advanced manifestation within the evolution of LUCC, differentiated from conventional LUCC studies primarily by fundamentally divergent spatiotemporal scales and trajectory characteristics. Whereas LUCC research predominantly emphasizes short-to-medium term, localized conversions and transitional processes, land use transition analysis focuses on the structural evolution of land use patterns, functions, and governance regimes across extended temporal and broad spatial scales, as driven by socio-economic transformations. This shift in perspective reflects a more profound stage of human–natural system interaction, capturing deeper structural regularities within these coupled dynamics [45].

2.2.2. The Diagnosis of Land Use Transition

Given the intrinsic connotation of land use transition, the configuration of land use forms constitutes its core analytical focus. Therefore, the scientific construction of a land use form indicator system, coupled with the accurate identification of morphological change characteristics, is pivotal to the diagnosis of land use transition.

The academic community currently holds two principal perspectives regarding the classification of land use morphology. The first perspective distinguishes between explicit morphology and implicit morphology. Explicit morphology manifests in relatively straightforward terms, directly characterized by the scale of land use and spatial configuration. In contrast, implicit morphology, which is contingent upon explicit forms, presents greater challenges in articulation. It encompasses attributes such as land quality, property rights, operational modes, and input–output relationships [40,44]. The second perspective differentiates between spatial morphology and functional morphology. Spatial morphology encompasses elements such as land use landscape patterns and operational arrangements. Specifically, landscape patterns refer to the overall spatial configuration formed by the assemblage of land patches of varying scales and shapes within a defined geographic area. Operational arrangements denote the composite structure resulting from different management entities utilizing land within a specific region, representing the interaction between land and its stewards. Functional morphology, approached from an externalities perspective, focuses on the integrated configuration of land’s three primary functions: production, living, and ecological services [46,47]. Explicit and spatial morphologies primarily reflect quantitative transitions, emphasizing changes in land quantity and structural configuration. In contrast, implicit and functional morphologies predominantly manifest qualitative shifts, with attributes such as land quality and input–output capacity focusing more on production functions, while factors like property rights and management models exhibit significant regional variations [45].

Building upon the framework of the aforementioned land use morphology indicator system, the crux of diagnosing land use transition lies in employing scientific methodologies to precisely identify the trend-altering turning points within long-term morphological evolution. The inherent volatility and phased nature of land use morphological changes result in numerous mutation points throughout its evolutionary trajectory. Among these, the trend-altering turning point represents the most archetypal mutation point within a given period, signifying a fundamental shift in the direction or pattern of change. Consequently, the identification of trend-altering turning points in land use morphology can be approached through the detection of mutation points. Methods such as the sliding t-test, Yamamoto test, and Mann-Kendall test are typically employed to compare morphological characteristics before and after each mutation point, thereby enabling the discernment of the pivotal trend-altering turning point [45,48].

2.2.3. The Mechanism of Land Use Transition

The mechanism of land use transition primarily investigates the driving factors and their operational pathways underlying shifts in land use morphology. Land use transition is closely intertwined with LUCC, representing a directional shift in land use morphology that emerges at an advanced stage of LUCC evolution. Consequently, the analysis of land use transition mechanisms logically originates from the identification of LUCC driving factors. Currently, academic discourse on the driving factors of LUCC has converged into two broad categories. The first encompasses proximate drivers, which include human activities such as built-up area expansion, agricultural land appropriation, deforestation, as well as environmental and climatic changes. The second category comprises underlying drivers, such as natural location, socio-economic conditions, technological advancements, and institutional-cultural frameworks, which influence land use indirectly by shaping the proximate factors [49,50].

It is evident that the underlying logic of land use transition lies in the cascading effects of the aforementioned deep-seated factors along their pathways of influence. Thus, the crux of analyzing land use transition mechanisms resides in elucidating the precise pathways through which these underlying factors exert their impact [45]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that land use transition emerges from the complex interplay and synergistic driving forces of both natural environmental factors and socioeconomic determinants [51,52]. Natural environmental factors—such as topography, geomorphology, soil properties, hydrology, climate, and precipitation—serve as the foundational determinants of land use transition. These elements exhibit relative spatial clarity and generally remain stable over short-term periods. However, their influence as driving forces may diminish over time due to technological advancements and adaptive human interventions [53]. Socioeconomic factors, which exhibit distinct spatial heterogeneity and evolve at a relatively rapid pace, encompass variables such as population dynamics, economic development, technological progress, cultural norms, and institutional frameworks. These factors typically influence land use transition by shaping market supply and demand, altering the allocation of productive inputs, and modulating the scarcity or availability of land resources [54,55].

Moreover, Chinese scholar Song Xiaoqing posits that land use transition constitutes an interactive feedback loop between spatial transformation and functional transformation, jointly shaped by the aforementioned diverse driving factors [45]. This perspective reveals, at a more profound level, the reciprocal relationships between land use transition and social, political, economic, and ecological systems.

2.2.4. The Effects of Land Use Transition

The study of land use transition effects involves evaluating its performance, thereby providing foundational support for subsequent optimization and regulation of land use. Current research primarily examines the effects of land use transition through three dimensions: economic, social, and ecological. Among these, economic effects primarily focus on aspects such as economic growth, industrial restructuring, income levels, and agricultural production efficiency [56,57], while social effects emphasize food security, rural livelihoods, urban–rural integration, and poverty alleviation outcomes [58,59]. With the growing emphasis on ecological awareness, attention to the ecological impacts of land use transition has significantly increased. In the fields of humanities and social sciences, methods such as ecological environment indices, carbon emission indices, and ecosystem service function indices are often employed to analyze the environmental gains and losses associated with regional land use transition [60,61,62]. Furthermore, in recent years, with the escalating emphasis on food security and cultivated land protection, the economic, social, and ecological effects arising from the transition of cultivated land as a specific land-use category have also attracted considerable scholarly attention [63,64].

In summary, current academic research on the effects of land use transition largely follows the analytical perspectives and methodologies developed for studying LUCC. However, land use transition and LUCC differ significantly in terms of conceptual mechanisms, spatiotemporal scales, and trajectory characteristics. Therefore, the analysis of land use transition effects should further focus on the potential impacts of trend-driven shifts in spatial and functional land use forms on economic, social, and ecological systems [45].

2.3. Coupling Research on Rural Transformation and Land Use Transition

2.3.1. The Coupling Relationship of Rural Transformation and Land Use Transition

Rural transformation refers to the dynamic evolution of intrinsic elements—such as population, industry, economy, and society—that collectively reshape the socioeconomic morphology and territorial spatial structure of rural areas [65]. With the accelerating flow of urban and rural factors, profound changes have taken place in rural production patterns, lifestyles, and socioeconomic conditions. As the spatial projection of socioeconomic development, the morphological structure of rural land use is inevitably undergoing transition and reconfiguration [66].

Currently, it is widely acknowledged in academic discourse that an interactive and mutually reinforcing coupling exists between rural transformation and land use transition. On the one hand, rural transformation serves as a significant driver of land use transition, providing the demand-pull necessary for such shifts. The evolving structures of population, industry, and settlements during rural transformation directly influence changes in both the explicit and implicit forms of land use. Explicitly, this manifests as the reconfiguration of production-living-ecological spaces, while implicitly, it involves transformations in land use patterns, functions, and value dimensions [67,68]. On the other hand, land use transition provides the material foundation and spatial framework for rural socioeconomic development, serving as a key indicator of the quality of rural transformation. By making scientifically sound and temporally coordinated arrangements for land resource allocation—while balancing the needs of diverse stakeholders—it optimizes the morphological structure and development-conservation patterns of rural land across multiple dimensions. This not only supports rural socioeconomic progress but also offers a tangible spatial reflection of rural transformation itself [69]. In theoretical terms, the two processes continuously optimize the allocation of rural resource elements and enhance land use efficiency through their coupled interaction, jointly driving the comprehensive, coordinated, and sustainable development of rural areas.

However, in practice, the relative lag in land institutional reform often results in land use transition trailing behind rural transformation [66]. The issue of decoupling between rural transformation and land use transition is increasingly prominent, manifesting in complex and diverse forms. For example, the misalignment between rural development progress and the transition of cultivated land use has resulted in extensive utilization and abandonment of farmland. Similarly, the temporal mismatch between rural transformation and the transition of residential land use has led to idle homesteads and the emergence of “hollow villages.” Furthermore, the discord between rural ecological revitalization and the transition of ecological land use has hindered the realization of ecological resource value. Therefore, the decoupling of rural transformation and land use transition is regarded as a significant contributing factor to rural decline in certain regions [70].

2.3.2. The Coupling Mechanism of Rural Transformation and Land Use Transition

The essence of the coupled development between rural transformation and land use transition lies in the process through which relevant stakeholders, in response to changes in rural territorial elements, adjust the functional structure of rural areas, optimize the spatial allocation of land resources, and intervene in the morphological characteristics of land use [71]. The coupling relationship between rural transformation and land use transition exhibits gradient differences across spatial and temporal scales [72]. The state of this coupling is influenced by a range of factors, including the natural environment, socioeconomic conditions, macro-level policies, and the behaviors of key actors.

First, the natural environment plays a formative and constraining role in the coupling interaction between rural transformation and land use transition. For instance, topography serves as a fundamental basis for the spatial heterogeneity of coupling intensity. Different landforms fundamentally influence land use patterns, thereby shaping divergent rural development models. Climate conditions also significantly affect agricultural production and rural livelihoods, introducing heightened uncertainty into rural development and land use practices. A harmonized coupling process must fully respect and adapt to the vulnerabilities inherent in the natural environment [73].

Second, socio-economic dynamics—particularly the industrial restructuring and economic system changes driven by urbanization and industrialization—exert external systemic influences that propel the coupling interaction between rural transformation and land use transition. The accelerated processes of urbanization and industrialization have prompted the functional attributes of rural areas to gradually shift from purely agricultural production toward multifunctional development. The emerging rural industries and new economic formats not only drive the transition of land use but also provide structural support for rural transformation itself [74].

Third, macro-level policies—particularly spatial planning and the associated policy environment—play a critical role in constraining and regulating the coupling process between rural transformation and land use transition. Spatial planning, employing mechanisms such as “quotas + zoning,” clarifies the coupling relationships among different land types and functions at the micro level. In coordination with relevant rural development policies, it serves as a key framework guiding both rural transformation and the adjustment of land use morphology [75].

Furthermore, the coupling interaction between rural transformation and land use transition is constrained by the behaviors of multiple stakeholders, including local governments, social capital, rural collective economic organizations, and farming households. In recent years, factors such as the role positioning, value orientations, and operational capacities of these stakeholders have led to challenges in policy implementation at the grassroots level, including policy deviations and disconnects. Therefore, safeguarding the rights and interests of stakeholders and standardizing their actions should be integral to the entire process of coupled development between rural transformation and land use transition [47,72].

2.3.3. The Coupling Regulation of Rural Transformation and Land Use Transition

The coupled and coordinated process between rural transformation and land use transition is pivotal to advancing rural revitalization. As rural transformation constitutes a complex systemic project, it is often influenced by inherent developmental inertia. The acceleration of rural transformation has increasingly intensified regional human–land tensions, making it imperative to optimize and regulate the coupling coordination between the two processes based on their interrelationship and underlying mechanisms. Only through such an integrated approach can rural revitalization be effectively supported [76].

Against this backdrop, scholars both domestically and internationally have sought to propose coupling regulation strategies in terms of regulatory philosophies, technical methodologies, and optimization pathways. First, regarding the regulatory philosophy, the majority of scholars argue that, based on the trends of rural transformation and the demands for factor allocation, defining matching village typologies as well as rural development-utilization and protection models can effectively guide land use transition [77]. Second, regarding technical methods, some scholars employ mathematical statistics and System Dynamics models to analyze the inherent patterns of land use transition. They further utilize models such as Cellular Automata and Multi-Agent systems to simulate land use demand conflicts under different rural development scenarios. By integrating Multi-Objective Programming models, they propose strategies for the optimized allocation of land resources [78].

Finally, regarding optimization pathways, these can be categorized into two major types: engineering measures and policy instruments. Integrated land consolidation and ecological restoration projects serve as key mechanisms for optimizing land use structure and layout, thereby promoting high-quality rural transformation. For instance, the construction of high-standard basic farmland as part of agricultural land consolidation effectively facilitates large-scale agricultural operations. The reclamation of abandoned industrial and mining land and the revitalization of rural residential land through construction land consolidation optimize the rural industrial structure. Ecological restoration projects focused on water systems and forestlands significantly improve the rural ecological environment [79,80]. At the policy level, scholars have proposed measures to improve the market-based allocation of land resources and its associated income distribution mechanisms—covering areas such as farmland transfer, incentives for cultivated land protection, homestead withdrawal, market entry for collectively owned commercial construction land, ecological compensation, and the realization of ecological product value. These approaches aim to foster a mutually reinforcing coupling between rural transformation and land use transition [81].

3. Research Review

Existing literature has conducted a series of studies focusing on rural spatial commodification, land use transition, and the coupling between rural transformation and land use transition, which provides significant reference value for this paper. However, a review of the existing research reveals that the following three aspects still warrant further exploration.

First, research on rural spatial commodification lacks systematic indicator measurement and quantitative validation. Existing studies have initiated preliminary discussions on the conceptual connotations, typological classifications, process mechanisms, and impact effects of rural spatial commodification, yet they predominantly rely on qualitative descriptions and case analyses. There remains a notable absence of in-depth quantitative deconstruction and empirical analysis. This gap not only hinders a comprehensive understanding of the intrinsic characteristics of this geographical phenomenon and the formation of academic consensus, but also limits the capacity to provide precise, evidence-based guidance for the governance of rural spatial commodification and the implementation of rural revitalization strategies. Therefore, a promising direction for future research lies in constructing a multi-dimensional indicator system grounded in the theoretical essence of rural spatial commodification, thereby enabling the quantitative assessment of its developmental levels and spatial-temporal dynamics.

Second, research on the coupling between rural spatial commodification and land use transition remains underdeveloped. Existing studies have extensively discussed rural spatial commodification and land use transition from various perspectives, yet they predominantly focus on analyzing the conceptual dimensions, formation mechanisms, and impact effects of each theme in isolation. Critical questions remain largely unexplored: Does an intrinsic linkage exist between rural spatial commodification and land use transition? How can their interactive relationships and underlying mechanisms be systematically revealed? These gaps represent a significant weakness in current scholarship, highlighting an urgent need for integrated research on their dynamic interconnections. Therefore, future studies should adopt “coupling” as a methodological framework to systematically integrate the two systems—rural spatial commodification and land use transition—and delve deeply into their interactive dynamics and formative mechanisms.

Third, cases of land use optimization guided by rural spatial commodification remain scarce. Existing studies, which aim to promote the coordinated coupling between rural transformation and land use transition, have constructed land use optimization and regulatory strategies that provide a paradigmatic reference for this research. As a new issue and emerging trend derived from rural transformation, rural spatial commodification exhibits a high degree of dependence on land factors, while land use transition may also intensify spatial conflicts among different types of commodified rural spaces. There is thus an urgent need to advance land use optimization explicitly oriented toward rural spatial commodification. Therefore, future research should compare and simulate the coupling coordination states of the two under different scenarios, clarify the dominant directions of rural spatial commodification, and accordingly propose regulatory policies that foster the coordinated optimization of rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

4. A Coupling Framework for Rural Spatial Commodification and Land Use Transition

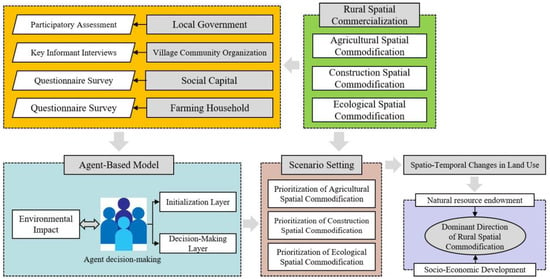

In summary, against the backdrop of the transition from rural “productivism” to “post-productivism” and multifunctional development stages, research on the coupling between rural spatial commodification and land use transition has emerged as a cutting-edge interdisciplinary frontier in rural geography and land system science. Looking ahead, future research should further focus on key themes such as the coupling mechanisms, evolutionary simulation, and optimization regulation of rural spatial commodification and land use transition. Following the logical progression of “elucidating theoretical connotations, characterizing coupling relationships, analyzing coupling mechanisms, simulating coupling processes, and regulating coupling states”, a comprehensive coupling framework integrating rural spatial commodification and land use transition should be systematically constructed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The coupling framework of rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

First, based on the theory of spatial production, the theoretical connotation of rural spatial commodification is elucidated, and a multidimensional quantitative indicator system is constructed in conjunction with typical practical models. Second, the spatiotemporal patterns of coordinated development in the coupling between rural spatial commodification and land use transition are revealed, characterizing their coupling relationships and dynamic features. Third, the influencing factors and their pathways of action within the coupled system of rural spatial commodification and land use transition are analyzed, clarifying the underlying coupling mechanisms. Building on this, by simulating and comparing the coupled coordination states of rural spatial commodification and land use transition under different development scenarios, the dominant direction of rural spatial commodification is clarified. Finally, regulatory policies aimed at promoting the coordinated optimization of rural spatial commodification and land use transition are proposed, addressing both explicit and implicit dimensions of land use morphology.

4.1. Theoretical Connotation, Practical Models, and Quantitative Deconstruction of Rural Spatial Commodification

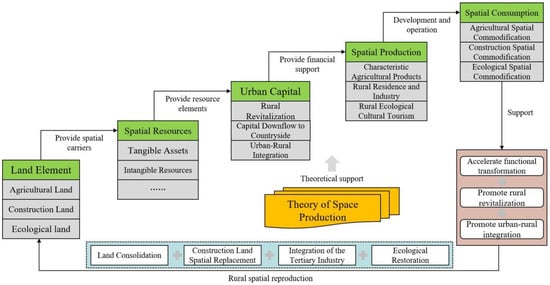

In the 1970s, French scholar Henri Lefebvre systematically articulated his “theory of the production of space” in his seminal work, The Production of Space. This framework transcends the conventional view of space as a static, material container, reconceptualizing it as both a crucial site and a product of social reproduction. Space is continuously produced, shaped, and contested through complex social processes, including policy regulation, capital investment, development practices, and social interactions.

As a pivotal extension of this theory, rural spatial commodification elucidates the logic by which capital facilitates value accumulation and reproduction through spatial mediation. Within a market economy, multiple dimensions of rural space—its physical environment, social relations, and cultural symbolism—are progressively incorporated into commodification processes. Driven by policy initiatives such as capital investment in rural sectors, rural revitalization, and urban–rural integration, rural space is transformed from a carrier of use value (e.g., for habitation or cultivation) into a commodity endowed with exchange value (e.g., via land transfers or tourism development). This transition reflects a functional shift from spaces of everyday life and production into tradable assets capable of value appreciation.

Therefore, grounded in the contemporary transition of rural areas from “productivism” to “post-productivism,” it is essential to first adopt the theory of space production as the logical starting point. This study integrates the multifunctional attributes of rural areas—encompassing both material production and non-material consumption—and examines the two-way flow of urban and rural resources; the analysis focusing on the entire process of rural spatial production, exchange, consumption, and preservation to elucidate the theoretical connotation of rural spatial commodification (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The connotation framework of rural spatial commodification.

Secondly, this study draws on Henri Lefebvre’s conceptualization of space as comprising three interrelated dimensions: material-functional, social-relational, and cultural-symbolic. Recognizing that the material-functional dimension serves as the tangible substratum for the two less tangible ones, and given that these intangible dimensions are embedded within and difficult to quantify directly, this research adopts a pragmatic approach. Our aim is to construct quantifiable indicators for rural spatial commodification and to establish a viable analytical coupling with land use transition. To this end, and building upon the typologies of rural spatial commodification elements proposed by scholars such as Woods, Perkins, and Wang Pengfei, this paper leverages the established material-functional classification of “Production-Living-Ecological Spaces.” We synthesize these foundations to propose a tripartite analytical framework—agricultural space, construction space, and ecological space—for systematically categorizing the manifestations of rural spatial commodification.

Based on this framework, we analyze the essential characteristics and specific manifestations of rural spatial commodification across these three spatial types. Agricultural spatial commodification aims to achieve scaled operations and industrial management. It is primarily realized through the market-driven transfer of farmland use rights and the commodification of agricultural products. Construction spatial commodification is functionally oriented toward accommodating non-agricultural economic activities and serving external consumption demand. It is reflected in the transfer and functional repurposing of rural construction land use rights. Ecological spatial commodification seeks to monetize rural ecological resources, chiefly expressed through the development of rural tourism and the marketization of ecological products. Building upon these analyses and considering the principles of scientific rigor and data availability, we construct an indicator system for commodifying these “three types” of rural space (Table 1). In subsequent empirical research, methods such as entropy weighting or the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) can be employed to determine the specific weights of each indicator.

Table 1.

The quantitative indicator system of rural spatial commodification.

4.2. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Coupled Coordinated Development Between Rural Spatial Commodification and Land Use Transition

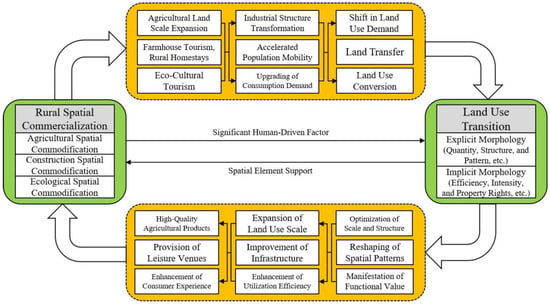

The interaction between rural spatial commodification and land use transition is characterized by mutual influence and interdependence. On one hand, rural spatial commodification serves as a significant human-driven factor in land use transition. By commodifying agricultural, construction, and ecological spaces—referred to as the “three types” of spatial commodification—it stimulates adjustments in the rural industrial structure, accelerates population mobility, and elevates consumption demands, thereby inducing shifts in land use requirements. Concurrently, to accommodate these evolving land demands, mechanisms such as land transfer markets and alterations in land use functions are activated, driving transformations in both the explicit and implicit forms of land use. On the other hand, land use transition provides essential spatial and material foundations for rural spatial commodification. Through pathways such as optimizing the scale and structure of land use, reshaping spatial patterns, and amplifying functional value, land use transition expands the availability of land resources, enhances infrastructure, and improves land use efficiency. These developments, in turn, enable rural spaces to offer differentiated services—such as high-quality agricultural products, comfortable leisure environments, and premium consumption experiences—ultimately shaping the trajectory and intensity of rural spatial commodification (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The coupling relationship of rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

Therefore, the analysis should first be grounded in land use transition theory, constructing measurement indicators from both the explicit and implicit dimensions of land use morphology. Explicit morphology focuses on quantitative changes in land use and spatial structure, while implicit morphology comprehensively considers aspects such as land use input output efficiency, intensity, and shifts in property rights.

Next, by integrating the quantitative indicator system for rural spatial commodification and utilizing multi-source data—including land use records, remote sensing imagery, socioeconomic statistics, and survey data—GIS-based spatial analysis methods are employed to quantify the developmental level of rural spatial commodification and the composite index of land use transition over extended time series.

Building on this, a coupling coordination degree model is applied to analyze the spatiotemporal patterns of coordinated development between the two systems—rural spatial commodification and land use transition. This approach reveals the differentiated responses and feedback mechanisms in their bidirectional coupling across different stages.

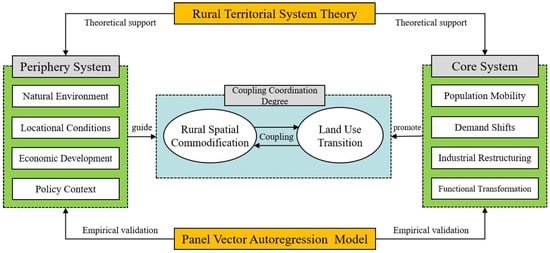

4.3. The Coupling Mechanism of Rural Spatial Commodification and Land Use Transition

The coupling relationship between rural spatial commodification and land use transition is influenced by a multitude of factors, including natural conditions and socioeconomic dynamics. Consequently, it manifests in diverse coupling patterns across different spatiotemporal scales and regional typologies. The theory of rural territorial systems provides crucial theoretical support for elucidating the formation mechanisms underlying this coupling relationship. It posits that a rural territorial system is a spatially organized rural entity formed through the interaction and integration of human, economic, resource, and environmental elements. It possesses distinct structures, functions, and interregional linkages, comprising two core subsystems: the periphery and the core. The periphery subsystem consists of external interventions and influences, such as the natural environment, external policies, and institutional frameworks, which exert pressures and inputs on the core. The core subsystem encompasses internal drivers of rural development, including rural population, land, and industries. These intrinsic factors interact dynamically with the periphery, co-shaping the evolutionary pathways and functional characteristics of rural territories. The continuous interaction and mutual adaptation between the periphery and the core collectively govern the systemic evolution and differentiation of rural territorial systems.

Therefore, on the basis of clarifying the coupling relationship and its phased characteristics between rural spatial commodification and land use transition, it is essential to further analyze the influencing factors and their pathways of action within the coupled system, thereby elucidating the formation mechanism of their coupling relationship.

First, drawing on rural territorial system theory, a theoretical explanatory framework for the coupling mechanism between rural spatial commodification and land use transition is constructed. This framework distinguishes driving factors at two levels: the periphery system and the core system. Periphery factors primarily include the natural environment, locational conditions, economic development, and policy context. Core factors encompass population mobility, demand shifts, industrial restructuring, and functional transformation. Theoretically, their interplay jointly determines the coupling mechanism between rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

Subsequently, a panel vector autoregression model is employed to empirically test this theoretical framework. This approach allows for the identification of the dominant drivers, their pathways of influence, and the strength of their effects in the coupling interaction between rural spatial commodification and land use transition, thereby clarifying the intrinsic mechanism underlying the formation of their coupling relationship (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The coupling mechanism of rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

4.4. Simulating the Evolution of Land Use Transition Based on Multi-Actor Demand in Rural Spatial Commodification

The essence of regional territorial space optimization lies in coordinating the allocation of spatial resources among different stakeholders. Against the backdrop of diverse and heterogeneous developmental trends in rural spatial commodification, clarifying the functional positioning and development orientation of rural territories can motivate stakeholders to adjust land use demands, thereby guiding the direction of land use transition and supporting the coordinated and sustainable development of both processes. Therefore, it is essential to incorporate the diverse demands of multiple stakeholders involved in rural spatial commodification into the simulation model of land use change. By comparing and simulating the coupled coordination states of rural spatial commodification and land use transition under different development scenarios, the analysis will provide precise and evidence-based support for subsequent optimization and regulation of their coupling relationship.

First, by defining scenarios for natural development and for the prioritized commodification of the “three types” of rural space (agricultural, construction, and ecological), and by integrating key coupling drivers, we construct an Agent-Based Model (ABM) to simulate land use change. The attributes and behavioral rules of key stakeholders—including local governments, village community organizations, social capital, and farming households—are defined using the Monte Carlo method. Within this framework, local governments primarily assume a macro-regulatory and coordinative role in land use change, with the intensity of their policy instruments and modes of response dynamically adapting to different scenarios. As proactive participants and passive adaptors in land use transitions, village community organizations, social capital, and farming households make decisions not only based on their objectives of maximizing their own benefits but also by incorporating mechanisms for responding to external environmental changes. For example, village community organizations weigh long-term returns against policy compliance in the process of introducing collective construction land into the market; the investment and withdrawal behaviors of social capital are influenced by market expectations, policy stability, and capital liquidity, while farming households comprehensively assess factors such as livelihood security, market price fluctuations, and policy risks in decisions regarding cultivated land transfer and residential land use.

On this basis, land use change transition rules are defined for different scenarios, and the model iteratively simulates the coupling of multi-agent decision-making processes, learning strategies, and adaptation mechanisms. This yields the land use scale-structure and spatial patterns under each scenario, based on which potential spatial conflicts in land use morphology during rural spatial commodification are identified.

Finally, by integrating regional natural resource endowments and socioeconomic development conditions, the functional positioning of rural territories and the dominant direction of rural spatial commodification are clarified. This provides a foundation for formulating regulatory policies aimed at promoting the coordinated optimization of rural spatial commodification and land use transition (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Simulation of land use transition based on multi-actor demand in rural spatial commodification.

4.5. Regulatory Policies for Promoting the Coordinated Optimization of Rural Spatial Commodification and Land Use Transition

Given the high dependency of rural spatial commodification on land resources and the exacerbation of spatial conflicts in the commodification of the “three types” of rural spaces by land use transition, it is essential to build upon the preceding research. Guided by the gap between the future dominant direction of rural spatial commodification and its current status, a differentiated policy system should be developed at both the explicit and implicit levels to promote the coordinated optimization of rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

At the explicit level, the focus lies on restructuring land use and optimizing spatial layouts. This involves establishing synergistic mechanisms among policies such as integrated land consolidation across entire regions, linkage between urban and rural construction land quotas, integration of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries, and ecological conservation and restoration. The aim is to explore land use balance policies oriented toward the developmental trajectory of rural spatial commodification. Concurrently, by leveraging tools such as territorial spatial planning and land use zoning regulations, these policies are designed to ensure that land use balance strategies effectively meet the land demands arising from regional rural spatial commodification.

At the implicit level, the focus shifts toward enhancing land use efficiency and optimizing socio-ecological benefits. Targeting prevalent issues such as farmland abandonment, idle rural homesteads, inefficient or vacant construction land, and ecological degradation, tailored strategies are proposed based on localized conditions. These integrate policy instruments including large-scale farmland transfer, rural homestead circulation and withdrawal mechanisms, market entry for collectively owned commercial construction land, and the monetization of ecological products. Through such a differentiated and context-sensitive policy mix, both the transformation and upgrading of rural spatial commodification and the optimized regulation of land use transition can be systematically advanced (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regulatory policies for promoting the coordinated optimization of rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

As rural areas transition from “productivism” to “post-productivism,” rural spatial commodification has emerged as a critical pathway toward comprehensive rural revitalization. This process is closely intertwined with and mutually influences land use transition. Based on a systematic review of research progress in both areas, this paper incorporates the emerging concept of rural spatial commodification into the analytical framework of land use transition to offer a novel perspective on their interconnected dynamic.

While existing studies have yielded substantial insights into rural spatial commodification, land use transition, and their coupled dynamics within broader rural transformation, research on the interplay between rural spatial commodification and land use transition—an emerging issue derived from ongoing rural restructuring—remains characterized by several notable gaps and limitations. These include: a lack of systematic indicator development and quantitative validation for rural spatial commodification, underdeveloped studies on the coupling between rural spatial commodification and land use transition, and a scarcity of empirical cases examining land use optimization guided by rural spatial commodification.

Therefore, future research on the coupling between rural spatial commodification and land use transition should follow the logical framework of “elucidating theoretical connotations, characterizing coupling relationships, analyzing coupling mechanisms, simulating coupling processes, and regulating coupling states.” It is essential to strengthen interdisciplinary integration between rural geography and land system science, thereby providing scientific guidance for rural resource allocation and revitalization practice.

This integrated framework advances through a five-step logical sequence: First, grounded in the theory of spatial production, we clarify the theoretical connotations of rural spatial commodification by examining the entire process of rural spatial production, exchange, consumption, and protection, and construct a multidimensional quantitative indicator system based on its typical practical models. Second, we employ a coupling coordination degree model to reveal the spatiotemporal patterns of coordinated development between the two phenomena, thereby characterizing their coupling relationships and dynamic evolution. Third, building on the theory of rural territorial systems, we establish a theoretical framework to explain their coupling mechanisms by analyzing the influencing factors and interaction pathways within the coupled system. Fourth, we extend the multi-agent model of land use change to incorporate the demands of diverse stakeholders. By simulating coupling coordination states under various scenarios, we clarify the dominant trajectory of commodification. Finally, we propose regulatory policies from both explicit and implicit dimensions to foster the coordinated optimization of rural spatial commodification and land use transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, F.L. (Fazhi Li) and F.L. (Fan Lu); writing—original draft preparation, Z.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; supervision, F.L. (Fan Lu); project administration, F.L. (Fazhi Li); funding acquisition, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Project of the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 24&ZD102.

Data Availability Statement

This study does not involve the creation of new data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Holmes, J. Impulses towards a multifunctional transition in rural Australia: Gaps in the research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.C.; Yang, Q.Y.; Yan, Y.; Yang, R.H.; Wang, D.; Zhou, L.L.; Zhang, B.L. Type characteristics, evolutionary stages and impact effects of rural spatial commodification. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, P.; Goodwin, M. Conceptualizing countryside change: From post-fordism to rural structured coherence. Transac-Tions Inst. Br. Geogr. 1992, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.N.; Qu, L.L. Multifunctional rural development in China: Pattern, process and mechanism. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.; Argent, N. Rural transitions in the Nambucca Valley: Socio-demographic change in a disadvantaged rural locale. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 48, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Cape York Peninsula, Australia: A frontier region undergoing a multifunctional transition with indigenous engagement. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.Z.; Zhou, G.P.; Qiao, W.F.; Yang, M.Q. Land use transition and rural spatial governance: Mechanism, framework and perspectives. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Ma, X.Y.; Chen, R.S.; Cai, Y.L. Marginalized countryside in a globalized city: Production of rural space of Wujing Township in Shanghai, China. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2019, 41, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes Responses and Experiences in Rural Restructuring; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Marsden, T.; Mooney, P. The Handbook of Rural Studies; Sage Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshio, K. The commodification of rurality in the Jike area, Yokohama City: The Tokyo metropolitan fringe. Tour. Sci. 2012, 5, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IIbery, B. The Geography of Rural Change; Addison Wes-ley Longman: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.F.; Ye, S.J.; Song, C.Q.; Gao, P.C. Logical process and mechanism of rural productive spatial reconstruction in Gannan plateau driven by rural spatial commercialization. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.H.; Su, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, P.F.; Zhang, X.B.; Liu, Z.G. Core forces’ superposition process and multi-dimensional effect of tourism-led rural space commodification: A case study of Zhuquan village in Yimeng mountain area. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 3007–3026. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. Performing rurality and practising rural geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 34, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, T. Commodification of rural space in Japan. Geogr. Rev. Jpn. Ser. A 2013, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabayashi, A.; Kikuchi, T.; Waldichuk, T. Commodification of rural spaces owing to the development of organic farming in the Kootenay Region, British Columbia, Canada. Geosp. Space 2019, 12, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.F. A study on commodification in rural space and the relationship between urban and rural areas in Beijing City. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2013, 68, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Entrepreneurialism, commodification and creative destruction: A model of post-modern community development. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.; Rees, G.; Murdoch, J. Social change, rural localities and the state: The restructuring of rural Wales. J. Rural Stud. 1989, 5, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D.; Lash, S.; Urry, J. Economies of signs and space. Contemp. Sociol. 1994, 23, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Theodore, N. Cities and Geographies of Actually Existing Neoliberalism. Antipode 2002, 34, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.H.; Wang, P.F.; Yu, W.; Zhao, Q.L.; Su, Z. Agriculture-type rural transformation in underdeveloped areas of China from the perspective of commercialization: A case study of Tang county in Hebei. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.L.; Cheng, L. Tourism-driven rural spatial restructuring in the metropolitan fringe: An empirical observation. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, D.; Van Dyck, C.; Verstraeten, G.; Segers, Y. The importance of the Great War compared to long-term developments in restructuring the rural landscape in Flanders (Belgium). Appl. Geogr. 2019, 111, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.R.; Xie, H.L. Rural spatial restructuring in ecologically fragile mountainous areas of Southern China: A case study of Changgang Town, Jiangxi Province. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Korzhenevych, A.; Hecht, R. Two decades of urban and rural restructuring in India: An empirical investigation along Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A.; De Waal, S.B. Revisiting the model of creative destruction: St. Jacobs, Ontario, a decade later. J. Rural Stud. 2009, 25, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Creative destruction or creative enhancement? Understanding the transformation of rural spaces. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorran, C. Understanding the ‘heritage’ in heritage tourism: Ideological tool or economic tool for a Japanese hot springs resort? Tour. Geogr. 2008, 10, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, N.; Mohamed, B.; Marzuki, A. Commodification stage of George town historic waterfront: An assessment. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A.S. Global Forest Resources; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mather, A.S. The forest transitiona. Area 1992, 24, 367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.T. Land use transition and deforestation in developing countries. Geogr. Anal. 1987, 19, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, A. National land use morphology: Patterns and possibilities. Geography 1995, 80, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Li, X.B. Analysis of regional land use transition: A case study in Transect of the Yangtze River. J. Nat. Resour. 2002, 17, 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.L.; Liu, Y.S. A brief background to rural restructuring in China: A forthcoming special issue of Journal of Rural Studies. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 1279–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.Z.; Long, H.L.; Zhang, Y.N.; Ma, L.; Li, T.T. Farmland transition and its influences on grain production in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Qu, Y. Land use transitions and land management: A mutual feedback perspective. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Ge, D.Z.; Yan, R.; Ma, Y.Y.; Sun, D.Q.; Lu, M.Q.; Lu, Y.Q. The evolution of the interactive relationship between urbanization and land-use transition: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2021, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Long, H.L. The economic and environmental effects of land use transitions under rapid urbanization and the implications for land use management. Habitat Int. 2018, 82, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuissl, H.; Haase, D.; Lanzendorf, M.; Wittmer, H. Environmental impact assessment of urban land use transitions: A context-sensitive approach. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Kong, X.B.; Hu, S.G.; Li, Y.R. Land use transitions under rapid urbanization: A perspective from developing China. Land 2021, 10, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.Q. Discussion on land use transition research framework. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 471–487. [Google Scholar]

- Spurgeon, D.J.; Keith, A.M.; Schmidt, O.; Lammertsma, D.R.; Faber, J.H. Land-use and land-management change: Relationships with earthworm and fungi communities and soil structural properties. BMC Ecol. 2013, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reenberg, A.; Fenger, N.A. Globalizing land use transitions: The soybean acceleration. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Dan. J. Geogr. 2011, 111, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, H.; Ho, P.; Hasfiati, L. Agricultural land conversion drivers: A comparison between less developed, developing and developed countries. Land Degrad. Dev. 2011, 22, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Liu, Y.Q.; Hou, X.G.; Li, T.T.; Li, Y.R. Effects of land use transitions due to rapid urbanization on ecosystem services: Implications for urban planning in the new developing area of China. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggering, H.; Dalchow, C.; Glemnitz, M.; Helming, K.; Müller, K.; Schultz, A.; Stachow, U.; Zander, P. Indicators for multifunctional land use: Linking socio-economic requirements with landscape potentials. Ecol. Indic. 2006, 6, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Hubacek, K.; Termansen, M. Underlying and proximate driving causes of land use change in district Swat, Pakistan. Land Use Policy 2013, 34, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliet, J.V.; Groot, H.L.F.D.; Rietveld, P.; Verburg, P.H. Manifestations and underlying drivers of agricultural land use change in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 133, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation. Bioscience 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction cost economics: How it works; where it is headed. De Econ. 1998, 146, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, E.A.; Meijaard, E.; Bryan, B.A.; Mallawaarachchi, T.; Wilson, K.A. Better land-use allocation outperforms land sparing and land sharing approaches to conservation in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 186, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defries, R.S.; Foley, J.A.; Asner, G.P. Land-use choices: Balancing human needs and ecosystem function. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldewijk, K.K.; Dekker, S.C.; Zanden, J.L.V. Per-capita estimations of long-term historical land use and the consequences for global change research. J. Land Use Sci. 2017, 12, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Land use transitions: Socio-ecological feedback versus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.S.; Kruska, R.L.; Muthui, N.; Taye, A.; Wotton, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Mulatu, W. Land-use and land-cover dynamics in response to changes in climatic, biological and socio-political forces: The case of southwestern Ethiopia. Landsc. Ecol. 2000, 15, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X. Carbon effects of land use transitions: A process-mechanism-future perspective. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, R.H.; Ojha, G.P.; Nepali, P.B.; Tiwari, U. Landscapes in transition: A study of agricultural land use change in Inner Terai of Nepal. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2025, 12, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Wu, W.X.; Li, Y.R. Effects of rural-urban development transformation on energy consumption and CO2 emissions: A regional analysis in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Long, H.L.; Cao, L.S. Construction of a research framework for coupling environmental and economic effects of land use transition under urbanization. Prog. Geogr. 2024, 43, 799–809. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.W.; Li, X.M.; Xiao, R.B.; Wang, Y. Effects of land use transition on ecological vulnerability in poverty- stricken mountainous areas of China: A complex network approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordway, E.M.; Naylor, R.L.; Nkongho, R.N.; Lambin, E.F. Oil palm expansion and deforestation in Southwest Cameroon associated with proliferation of informal mills. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Lu, S.S.; Chen, Y.F. Spatio-temporal change of urban-rural equalized development patterns in China and its driving factors. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; He, X.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Meng, Y. Functional evolution of rural housing land: A comparative analysis across four typical areas representing different stages of industrialization in China. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.C.; Fox, J.; Melick, D.; Fujita, Y.; Jintrawet, A.; Jie, Q.; Thomas, D.; Weyerhaeuser, H. Land use transition, livelihoods, and environmental services in montane mainland Southeast Asia. Mt. Res. Dev. 2006, 26, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C.; Grainger, A. The forest transition: Towards a more comprehensive theoretical framework. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]