Abstract

Environmental factors motivate migration across the globe, calling for better planning. Although the US experienced such movements during the COVID-19 pandemic, literature on population mobility and outcomes for receiving communities in the US is scarce. We use a mixed-methods case study approach to explore the COVID-era population movement trends in the US Northeast (NE) Region and their outcomes for receiving communities to draw lessons for strategic regional planning aiming to achieve sustainable and equitable outcomes of disaster-induced movements. Utilizing the Statistics of Income data and focus group data collected from 27 local experts in 22 rural counties of NE, which experienced the highest relative numbers of in-movers between 2016 and 2020, the findings revealed the top receiving counties were predominantly rural areas where urbanites moved from within NE. This movement challenged the housing market and services, disproportionately burdening socioeconomically disadvantaged groups in receiving communities. The COVID-19 experience opened a window of opportunity for regional planning to prepare desirable outcomes of such mobilities by addressing existing issues in receiving communities while incorporating pulse and slow population movements into the agenda. The right policy timing and communication among communities are keys to building trust and ensuring integration of newcomers into receiving communities.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unique conditions leading to rapid population movement from urban to rural and suburban areas, better documented internationally [1,2,3,4,5] than in the U.S., with a few in the planning literature addressing this period (see [6] as a counterexample). This movement of urban residents to rural areas—also referred to as counterurbanization—may bring economic and cultural liveliness to receiving communities [7]. It can be viewed as an opportunity for sustainable growth, especially in small towns when communities strategize for adaptive policies such as retrofitting existing buildings, integrating mixed-use zoning, and prioritizing demand-side management [8]. Receiving communities can even expand their capacity to address climate adaptation and mitigation through strategic planning that navigates this growth [6]. On the other hand, the influx may challenge the existing systems in rural communities that already struggle with higher poverty rates than urban areas and limited infrastructure, governance, housing, and resilience capacity [9]. While some slow-growth and declining areas welcome the prospects of newcomers replacing an aging and shrinking workforce, the sudden and large-scale influx of new people can tax environmental and human infrastructure systems. Rapid in-migration can also stress the socioeconomic well-being of the host communities by increasing costs and competition for housing and other scarce goods. Without preparatory planning, rapid in-migration brings greater pressure on existing social and built infrastructure and significant risks of landscape fragmentation and ecological harm [10]. For these reasons, it is crucial to understand what happened during the peak COVID-19 period—in terms of the numbers and locational choices of the movers—and explore the outcomes of these movements for receiving communities.

While COVID-19 was a singular event, increased and often rapid population movements are likely to grow over this century as climate change worsens [11]. In 2018, more than 16 million people globally were displaced due to weather-related disasters, including 1.2 million people in the US. Sea level rise (SLR) alone is projected to put 13.1 million US residents at risk of migration by 2100 [12]. An increasing number of people live in areas at growing risk from both extreme heat and wildfires [13]. Considering this growing number of movements driven by various hazards, we adopt a broader approach to the population mobility problem to better understand the dynamics and outcomes of mobilities under environmental change.

The Northeast region (NE) is an ideal case to explore the on-the-ground experience of COVID-era migration as an example of disaster-induced population mobility on a larger scale. Major metropolitan areas in the region—e.g., the New York Metro Area—experienced outmigration after the outbreak of the pandemic [14]. Studying this region is also important, as in the longer run the region is expected to receive migrants from SLR- and coastal flooding-experiencing areas [15] as well as from extreme heat-impacted communities [13,16]. Northern states—e.g., Vermont and upstate New York—are anticipated to be safer destinations for people who relocate due to climate-related disturbances [17], with cities such as Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo receiving media attention as climate havens or climate refuges [18,19,20].

This study adopts a holistic approach to the problem by analyzing peak COVID-19 years’ mobility through a mixed-methods case study. Our analysis first takes a retrospective approach to review the pre-COVID-19 years, starting from 2010 until 2020, when the outbreak began. Then we focus specifically on the COVID-19 years between the beginning of 2020 and summer 2023, when the immediate impacts faded, and the remaining impacts of population mobility could still be observed. It examines the population movement trends based on US federal Statistics of Income (SOI) data and presents ground-truth information acquired from focus groups with key informants (n = 27)—housing experts from highly impacted receiving communities in NE. The demographic modeling was over the whole region, while the focus groups centered on more rural areas that experienced rapid in-migration.

This article first reviews our current knowledge about drivers of COVID-era mobilities and potential outcomes observed in similar cases that have been reported in the literature and briefly introduces strategic regional planning. It then presents the two-stage research design, followed by the findings of migration trends in NE and the outcomes for receiving communities of these migrations. Our findings reveal significant challenges faced in receiving communities—i.e., housing crunch, overloaded infrastructure, and growing burden on socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. Taking these findings into account, we argue that the COVID-19 experience provides lessons for recent rapid-onset population mobility trends and their potential outcomes for receiving communities. Big cities and metro areas, the traditional hubs of resources, are no longer the only attraction points. Movements driven by various environmental disasters and repetitive or slow-onset environmental hazards, such as wildfires, drought, and socioeconomic factors (e.g., housing crises) may push populations towards destinations that are not historically accustomed to population influxes—smaller, more remote communities. These changes can significantly challenge the infrastructure and social systems in small communities that typically have limited resources to adapt. Receiving communities may benefit from regional planning that addresses already-existing problems in rural communities and understands evolving drivers and outcomes of population mobility.

We argue here that COVID-19-related migration can be understood as a specific instance of the broader category of environmental/disaster-related migration, which is a well-studied field [21,22] and historically important, with experiences such as the US Dust Bowl of the 1930s, which led to over 350,000 rural migrants moving to cities and towns largely in California [23]. There is potential for strategic regional planning to be an active voice in preparing for and responding to similar events. It may be difficult for municipalities to address potential disaster-related migration in their standard comprehensive plans, given the complexity and uncertainty inherent in disasters and the often legally specified nature of municipal comprehensive plans. Strategic planning, however, may provide an avenue for addressing this, in that it is designed to address a more specific set of issues to arrive at policy priorities [24,25], and can be used in policy and engagement arenas that center social and environmental justice [26]. A focus on justice is important for environmental and social disasters generally, as their impact is highly uneven based on socioeconomic status [27,28]. These issues were also apparent in COVID-19 impacts [29,30]. Strategic planning, with its more narrow focus compared to comprehensive plans, pairs well with the use of scenarios [31] as a way to manage uncertainty [32]. To date, the use of scenario planning for disaster-related migration has largely been at the national level (see, e.g., [33]), but there does not appear to be a particular reason why it could not be applied at a metropolitan or at least multi-state level, and examples of this exist [34]. Scenario planning at the regional, local or even census track scale is common (see, e.g., [35,36]). Strategic planning and scenario analysis rest on projecting possible future trends and understanding their impacts. Our findings below on the extent and impact of COVID-19 population mobility in the US Northeast provide helpful information for both goals.

Understanding Migration During the COVID-19 Era: What We Know and What We Do Not Know

For the last thirty years, urbanization has explained most migration [37]. City centers and metropolitan areas have been the predominant destinations of internal migrants across the world [37,38,39]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic transformed the population migration dynamics around the world [38,40], especially because the cities were more severely affected in the early stages of the pandemic [40]. Some manufacturing cities that have typically attracted migration (e.g., Dongguan, China) were reported to shrink during the COVID-19 years [41].

The pandemic greatly complicated existing mobility patterns. While international migration declined by 27% [42], the United States saw a notable shift where rural and peripheral areas became relatively more attractive to migrants fleeing metropolitan areas with higher infection and mortality rates [43,44,45]. The outbreak raised concerns around population density in cities—density in the home, neighborhood, and wider city [46]—which worsened infection and mortality rates, although lockdown policies alleviated the impacts [47]. As opposed to bigger cities, rural territories generally exercised lighter pandemic-imposed isolation and economic controls [45]. The availability of rural broadband was an important facilitator of remote work opportunities, enabling population spread [48]. Hence, rural counties and low-density, small communities experienced population growth and/or lower out-migration compared to their historical trends [49,50]. In the specific context of the New England region of the United States, studies (see, for example, [51]) reported notable population shifts from the metropolitan core areas to the micropolitan or noncore locations in late summer and fall 2020 [51,52].

An important consideration in disaster-related migration is the rate of return—how many households move permanently versus how many relocate temporarily. Some researchers found little to no support for a long-term major exodus from the cities [39], finding that trends returned to their pre-pandemic values in a couple of years [49,53]. In the first year after COVID, Rowe et al. (2023) viewed COVID’s effect on mobility as a “shock wave” leading to temporary changes rather than reshaping the existing structures in Britain [40]. Evidence from six countries, for example, revealed that the out-migration from cities seems to have been temporary, but some countries, such as Spain and Britain, faced persistent losses in highly dense areas [40]. In the specific case of the New England region, Nelson & Frost (2023), analyzing the data from mobile devices and a real estate brokerage website, Redfin, argued that rural areas in the region gained population, but the trends bounced back to their pre-pandemic conditions towards the end of 2020 [51]. The same study also warned us about the initiation of a new wave of rural gentrification, as rural areas have been experiencing an increase in real estate activity [51]. A key component of migration to rural areas is often the search by urbanites for lifestyle amenities [54,55,56]. To develop a deep understanding of the effects of these movements on receiving communities, our study adopts a mixed-methods approach by first modeling migration trends in NE at the peak of COVID-19 and then analyzing ground truth data collected from informed experts in highly impacted areas.

Regardless of whether the rural influx has been a short-lived trend or a sign of a more permanent change, literature is united on the toll it places on receiving communities. Scholars repeatedly found rising housing prices and saturated public services [49,57], and difficulty balancing the needs of current residents and newcomers [58] in receiving communities. The COVID-19 migrants, being typically on the wealthier side, brought higher sale prices into the housing market, leading to concerns about gentrification in rural communities [51]. It is fair to expect various social and cultural mismatches, considering that the movers typically have very limited and superficial interactions with the hosting communities (see, for example, [59]). On the other hand, the influx may also be seen as an opportunity for growth in rural areas’ income, employment, and business. As experienced in rural tourism after COVID-19—see, for example, [60,61]—a growing population may stimulate the economy of structurally disadvantaged rural communities, especially when initiatives are provided by the governments. Increased in-migration may help with the problem of population aging and loss of young, educated people in the countryside [37].

In light of these debates and research gaps, this study contributes to the existing literature by quantitatively and qualitatively exploring the ground truth of COVID-19-induced population movements in the US Northeast, their outcomes, and implications for regional planning. It addresses the following questions:

- R.Q.-1: What were the trends of COVID-era population movement in the NE region?

- R.Q.-2: What were the infrastructure-related and socioeconomic outcomes of COVID-era movements for receiving communities, based on housing experts’ perspectives in high-inflow areas of the region?

- R.Q.-3: What lessons can be drawn for regional planning efforts aiming to achieve sustainable and just outcomes of disaster-induced population mobilities?

2. Materials and Methods

This study uses a multi-stage research design. First, to provide an overview of mobility, we analyzed population trends in NE during 1999 and 2020—i.e., the year which we generally call the ‘peak COVID-19’ or COVID-19 era, comparing it to the previous years. Based on these trends, we identified highly impacted areas for further qualitative work, as described below.

2.1. Modeling

In this stage, we analyzed migration trends in the Northeastern U.S. immediately before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our primary goal was to identify places within the study area that had a higher-than-expected net in-migration during the COVID years. Our study area specifically encompasses seven states in NE: Connecticut (CT), Maine (ME), Massachusetts (MA), Rhode Island (RI), New Hampshire (NH), New York (NY), and Vermont (VT).

To identify in-migration “hot spots” within the Northeast, we calculated county in-migration (inflow) rates in total as the number of people who moved into each county between 2016 and 2020 [62], divided by its total population in 2020. Using this time frame was instrumental to identifying the hot spots, because some predominantly rural NE states (e.g., Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine) started showing a trend of net in-migration around 2016, which relapsed after the outbreak in the first quarter of 2020. Although our focus is on COVID-19 era migrations, we specifically covered the five-year period to better understand the longer-term experiences of receiving communities rather than merely capturing a “snapshot” of COVID-19 movements.

We also distinguish US migrants coming from outside the Northeast region. Our primary data source on domestic migration is the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) Statistics of Income (SOI) series [63].

The SOI series is commonly used in migration studies, as it is among the few public sources on the yearly movement of people between counties within the United States. Because it is based on tax returns, the SOI does not directly report the number of migrants, but rather the number of exemptions (a proxy for people) that filed a tax return in a different county from the previous year [63]. It also does not cover households that do not file taxes, such as those living solely off social security, and may undercount moves where the filer does not change their address on their return. This may be the case for those who viewed their move as temporary or changed their place of residence but continue to work in their former state. Because of these limitations, the SOI data is best interpreted as a proxy of the flow of people between counties rather than as a direct count of migrants. Population totals are taken from the 2020 Decennial Census [64].

Qualitative Data: Based on the methods above, we identified counties in the US Northeast (NE) with measurable growth in in-migration. Within these areas, we conducted focus groups and interviews with local experts to gauge their perception of the reasons behind the increased inflow and the impacts of new residents on their communities. The focus group discussions covered population mobilities in recent years, specifically the five years starting from 2016 to the end of 2020 [62]. Based on our preliminary analysis, some of these states had initially seen in-movers in 2016 and experienced a similar trend of movements in the first quarter of 2020. Hence, this time frame was selected to understand the long-term impacts on receiving communities in rural NE.

We focused on inland (non-coastal) counties in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York that were found to receive an unprecedented migration in recent years (Figure 1). We further refine our focus to rural, inland counties, as, respectively, identified through the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Rural-Urban Continuum Codes [65], and in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Coastal Shoreline Counties database [66]. This allowed us to concentrate on “outlier” communities that are likely to see a significant increase in-migration by virtue of their relatively small size.

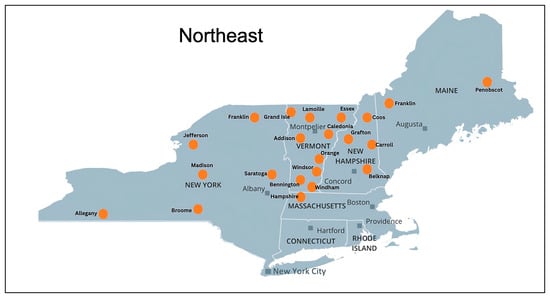

Figure 1.

Hotspots—Counties with highest inflow rate. The orange spots are the names of the counties. (Source: [62,63,64]; Authors’ calculations).

The final study area encompasses 22 rural, inland counties that either had total inflow rates of 8% or more overall or inflow in excess of 5% where more than 20% of movers came from outside the Northeast region (Table 1).

Table 1.

The List of Counties—22 rural inland hotspots for COVID-19-era in-migration.

2.2. Focus Groups

Within these 22 counties, we convened focus groups to understand more about patterns of, motivations for, and outcomes of in-migration. We adopted a purposive sampling design to identify focus group participants comprising local housing specialists. We identified prospective participants via web searches and contacted each potential participant up to three times via email. Out of a total outreach sample of n = 1647, there were a total of n = 27 confirmed focus group participants, including 22 real estate brokers, two county-level housing experts, and three state-level housing experts (Table 2). Despite our efforts, no mobile homeowners/managers agreed to the focus groups. This remains an important group to consider for future research.

Table 2.

Focus Group Participants by Role and Geography.

We conducted seven focus group events via Zoom video conferencing, each including from two to eight participants and lasting between 75 min to two hours. We asked participants 12 open-ended questions on topics including recent population movements and factors that motivated in-migration to the area, existing capacity of their communities, and the effect of migration. We videorecorded the focus groups with the permission of the participants, used Otter.ai Notetaker Web Version for initial transcription of the recordings, and manually corrected AI errors. The transcriptions were coded into NVivo14, based on pre-set codes from the research questions and those emerging from the discussion. To ensure intercoder reliability, two coders created a codebook prior to the coding process, collaboratively edited the codebook as they proceeded, and merged two separate full-coding files after completing the coding process, resolving differences collaboratively.

3. Results

3.1. RQ1 Modeling: Northeast US Migration Trends During COVID-19

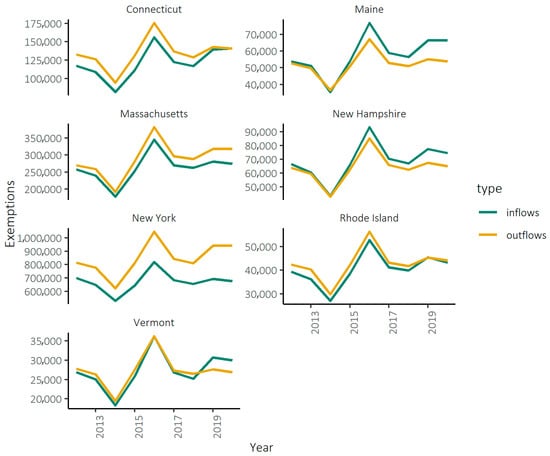

We find a clear distinction in recent migration trends between the most and least urbanized states (Figure 2). Most states in the Northeast have experienced net out-migration since 2011. This is particularly true for more populous states in the southern portion of the region, such as New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut (Figure 2). As the pandemic took hold in 2019 and continued into 2020, the gap between out- and in-migration widened in New York and Massachusetts. By contrast, the gap between outflows and inflows narrowed considerably in Rhode Island and Connecticut. Predominantly rural states had a different experience. In the years just prior to the pandemic, Maine and New Hampshire had slight net in-migration, while in Vermont, inflows and outflows were largely in balance. When the pandemic hit, these less populous states saw a notable influx of new residents, which continued into 2020.

Figure 2.

Populations Moved to a New County (Source: [63] and Authors’ calculations).

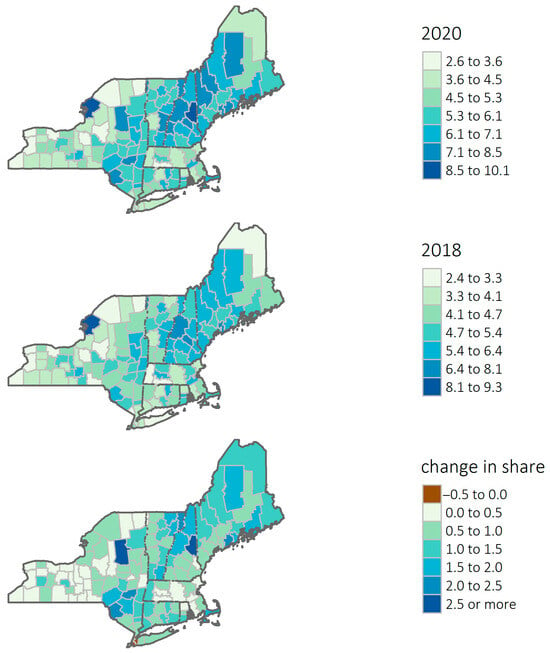

The top 75% of receiving counties hosted newcomers mainly (77%) from elsewhere in NE. A common explanation for these observed patterns is the exodus of residents from densely urbanized areas to more remote areas during the pandemic. There is some evidence to support this perspective. Counties with the largest relative influx of new residents during 2020 (peak-pandemic) tended to be rural, interior counties, such as Jefferson, New York; Carroll and Grafton, New Hampshire; Lincoln, Maine; and Grand Isle, Vermont (Figure 3, top panel). Nevertheless, the overall patterns of in-migration were similar to pre-pandemic (Figure 3, middle panel), although the number of migrants (in-migrants—we can clarify that here) increased for most areas. Looking at changes, Hamilton, New York; Carroll, New Hampshire; Essex, Vermont; and Lincoln, Maine had the greatest increase in-migration rates from 2018 to 2020 (Figure 3, bottom panel). Only three counties in New York City (Bronx, Queens, and Kings) had lower in-migration rates during the pandemic. It was typically interior areas that saw the most gains in in-migration during peak COVID-19, as well as several counties in mid-coast Maine (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

County In-migration Rates (inflows/population). (Source: [63] and Authors’ calculations).

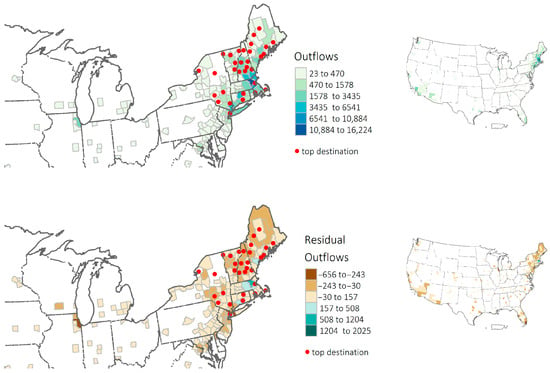

The top origin counties are also among the most populous counties in the study. We would therefore expect more out-migrants coming from these places by sheer virtue of their size. To account for the “typical” amount of out-migration between counties, we subtract the average annual pre-pandemic flows (2015 to 2018) from peak-pandemic (2020) levels. We refer to this as residual out-migration, where darker teals highlight areas with notably more out-migration compared to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 4, bottom panel). Dark browns indicate areas that had lower-than-expected levels of out-migration into a top destination during the pandemic. The lower panel of Figure 4 emphasizes that the noteworthy influx of new residents during the pandemic was really the consequence of people moving out of a relative handful of the most populous counties in the region: Kings, NY; New York, NY; Middlesex, MA; Suffolk, MA; Queens, NY; Worcester, MA; and Worcester, MA.

Figure 4.

Places of origin of migrants moving to top destination counties (Source: [63] and Authors’ calculations).

The models indicated that during the COVID-19 years, predominantly rural states—i.e., Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont—experienced a significant influx of incomers. Our county-level analysis supported the common expectation of “urban exodus” counties in mid-Coast Maine, which saw the most gains in in-migration during COVID-19 compared to pre-pandemic (2018) in-migration values. Moreover, the analysis of the origins of migrants revealed that this influx of new residents during the pandemic was predominantly the consequence of people moving out of some of the relatively most populous counties, including Kings, NY; New York, NY; Middlesex, MA; Suffolk, MA; Queens, NY; and Worcester, MA.

Our findings from focus group discussions supported that the in-migration towards rural communities during the COVID-19 years was extensive, and the newcomers were mostly from bigger cities and metro areas located within the NE region (e.g., Boston, New York City). The participants argued that the urbanites moved from metro areas mainly due to socioeconomic challenges—e.g., cost of living, public safety, and population density—they faced in bigger cities and the changes in lifestyles—i.e., the need for isolated living spaces and remote working opportunities that were accelerated during COVID. Rural areas offered housing affordability, i.e., lower price per square foot, high-quality social services (e.g., healthcare, schools), and natural amenities such as large lots and access to freshwater that attracted people—usually extended families—who were interested in permaculture. Some areas, such as the Five College Area in Massachusetts—the Connecticut River Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts, which houses five higher education institutions—were claimed to provide various employment opportunities, especially for those who had existing friendships or familial ties in the area.

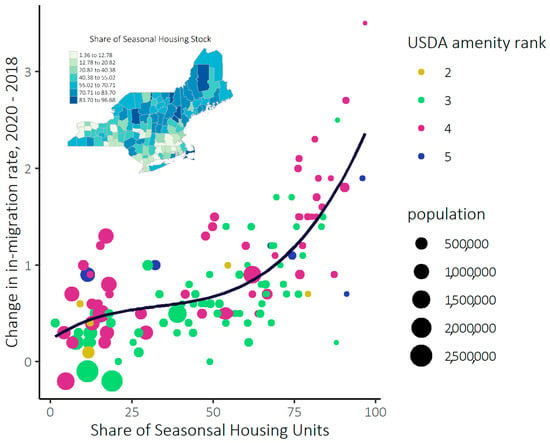

Common knowledge on “urban exodus” suggested that many city dwellers retreated to secondary residences in the more naturally pristine rural communities to wait out the pandemic or take advantage of the flexibility afforded by remote work [44]. To test this, we measure the change in in-migration rates from peak-pandemic to pre-pandemic (i.e., 2020 minus 2018) against each county’s share of seasonal/second homes (Figure 5). We find a curvilinear association between seasonal housing stock and the change in migration. For counties with relatively low shares of seasonal housing, the relationship with pandemic inflows was positive but rather mild. However, counties with high shares of seasonal housing (>60%) had a notably strong influx of new residents during the pandemic. Recipient counties also tend to be smaller (i.e., lower pre-pandemic population). Our findings support the general view of what happened—movers relocated to their second homes.

Figure 5.

Relationship between seasonal housing, population, and pandemic in-migration (Source: [63,64,67] and Authors’ calculations).

We used the Natural Amenities Scale for U.S Counties dataset, which provides a measure and rankings of the physical characteristics and environmental qualities (i.e., the six measures of climate, topography, and water) of a county area, introduced by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) [67]. The bubble sizes indicate the number of in-movers that the counties received. The amenities, as ranked by the USDA, did not have a strong association with the in-migration rate. This is because, in the Northeast at least, heavily populated coastal counties (sending areas) also rank high in natural amenities on the USDA amenity scale.

3.2. RQ2: Outcomes for Receiving Communities

Rural NE communities, accustomed to little (or no) population growth, were surprised by the rapid onset of newcomers and felt “tremendous” impacts specifically on the housing market, infrastructure, and socioeconomic conditions, according to our focus group participants. As summarized in Table 3, housing-related challenges included limited housing stock that could not keep up with the increasing demand—reported by n = 27 (100%) of the participants, the lack of affordable housing options—reported by n = 26 (96%), and the barriers to new development in the communities, reported by n = 21 (78%) of the participants. Infrastructure-related challenges included insufficient and aging physical infrastructure—reported by n = 15 (56%), and insufficient social services, reported by n = 14 (52%) of the participants. Socioeconomic challenges were displacement and gentrification—reported by n = 18 (67%), increasing homelessness—reported by n = 9 (33%), and lower income groups’ lower adaptive capacity to tackle changes in receiving communities—reported by n = 14 (52%) of the participants. The local experts’ recommendations on regional planning were summarized under three sub-themes: balancing their focus on existing issues in the communities and changing trends in regional population mobility—reported by n = 20 (74%) of the participants, collaboration between the levels of governments and stakeholders on monitoring and communicating these changes—reported by n = 19 (70%) of the participants, and adopting a proactive planning approach by developing a timeframe that introduces the right time for policy action—reported by n = 11 (41%) of the participants.

Table 3.

Focus Group Findings.

3.2.1. Housing-Related Challenges

Housing stock could not keep up with the increased demand for for-sale and rental properties. In some areas, inventory was so low that a property was sold “as soon as it gets on the market [...] unless it’s absurdly expensive.” Both first-time and step-up home buyers found it difficult to compete against typically wealthier newcomers for what little stock became available. A real estate professional from Hampshire County, Massachusetts, described the market as:

We’ve seen building lots that no one would have put on the market. Or they held on the market for years... because it’s next to a train track or because [it’s on] high water table. You have to put a raised septic system and that…costs you [...] 35-40 grand on top of everything on a hill. You know, that’s just really not desirable, cramped up. And they sell!!!

Rental inventory was similarly limited. As reported by a broker from Grand Isle, Vermont:

Last summer, I sold a property for this older woman. Her husband had passed away. Owning a house was just too much for her. I had been speaking to her for three years, she was ready to get out. And she just wanted a place to rent because she didn’t want to be a homeowner anymore. And [for] three years [...] I’m posting stuff on Front Porch forum [...], Putting stuff on Facebook saying “Does anybody know of a rental?” And nobody!!!

Construction costs became another significant barrier. The cost of materials, equipment, and labor all spiked during COVID, increasing the total costs of construction significantly. The region’s aging population and historic slow growth compounded difficulties finding laborers of skilled tradespersons. A broker in Windsor County, Vermont, shared that:

We have no labor! [...] You have people moving here because they want to be in the country. But there’s no one here to service them. Because there’s no lodging for service people. We have no tradespeople. The average age of tradespeople is 59 years old. There’s no young people to take over those positions. And I’d gladly welcome migrants to come here, with job skills, because there’s [an] endless amount of work, but there’s no place for them to live [...].

Short-term rentals, such as Airbnb and VRBO, also contributed to the rental crunch. Participants were concerned about the “frenetic increase” in short-term rentals since 2020 as year-round housing became limited for permanent residents, which might help “populate the schools and create a thriving community.”

Low-income housing experts were extremely frustrated. A director of a community trust in Vermont shared that “somebody getting a mortgage can’t compete with a cash buyer, let alone somebody trying to work through the land trust.” Another said their homeownership program had “ceased to function anymore,” both from the difficulty in finding existing homes and in patching together multiple and challenging funding sources for new construction. Alternative housing solutions (e.g., mobile houses, RVs) started to “pop up” in unusual places—such as next to existing farms—and stay longer than just seasonally. Others discussed the potential renovation of old mills and factory buildings into affordable (or at least attainable) housing.

3.2.2. Infrastructure-Related Challenges

As underlined by a broker from Hampshire County, MA, “it’s not just the lack of housing... [but] the lack of services to get people on their feet” in the communities impacted by migration. The participants argued that the infrastructure—specifically heating, electricity, wastewater, and stormwater treatment—was very old and limited for the existing population, even before in-migration. An influx of new residents would likely challenge the already-fragile electricity infrastructure, especially if coupled with increased electric use, such as through residential heat pumps, electric vehicles, and dependence on seasonal renewable energy sources (e.g., solar energy with lower production in winter). Renters cannot switch to more efficient electric heat pump systems, leaving many homes cold in winter and without air conditioning in summer. Similarly, the dependence on septic systems is a significant barrier to development in rural communities, given that septic requires large lots. Many homes on septic tanks also use well water, creating obvious hazards when systems fail.

Communities are also challenged by the lack of some of the services, especially technological services. Internet and cell service were reported to be “overwhelmingly” inadequate in some areas. The in-movers, often remote workers who relied heavily on internet connectivity, found the limited/unstable access severely insufficient, especially in more outlying settlements, despite some ongoing efforts such as the New NY Broadband Program [68]. Social infrastructure—i.e., schools, childcare, healthcare, nursing homes, and emergency services—is also poorly equipped to accommodate a population influx in rural NE communities. School buildings are old, some dating back to the 1970s or earlier, and many lack the staff or classroom space to absorb new students. For instance, a broker from Addison, VT, reported that her daughter’s school had “[enrolled] 100 new kids over the summer,” which had “a big impact” on school capacity in small communities. These rapid influxes are difficult to foresee and prepare for, especially in the towns where secondary houses or short-term rentals suddenly became permanent housing. While “overcrowding” was most prominent for high-rated school districts, it created a domino effect on regional school systems. Pressure in higher-rated school districts pushed lower-resourced families to more peripheral towns. This challenged outskirt towns’ housing markets as well as school resources (e.g., teachers, equipment, classes). The lack of affordable childcare services was also a significant problem for rural communities.

Sudden population growth also strained rural healthcare systems. Elderly care, an already-existing concern in rural communities due to the aging population, has become a growing issue fueled by the shortage of nursing homes. Many feared that sudden growth would spark the vicious cycle, whereby the lack of affordable housing leads to staffing problems. It was argued that the communities will fail to “replace and train in the generation that will take care of them” unless they build enough affordable housing for the service sector employees. Older homeowners were also reluctant to put their property on the market because there was no appropriate housing for them to move into.

Local emergency and fire departments lacked resources and equipment to respond to an emergency, especially in remote areas. Services for newcomers were limited. The participants noted an acute need for regional and local planners to “start looking at these issues [insufficient services].” In some areas, newcomers brought new politics to local decision-making. In Addison County, Vermont, for instance, newcomers reportedly took a position against having truck traffic on the main street, unlike most of the locals who were used to it.

3.2.3. Socioeconomic Challenges: Growing Pressure on Low-Income Populations and Businesses

Local experts repeatedly expressed concerns about the impact on disadvantaged communities. Low-income households have fewer resources and a lower capacity to adapt to changes in their community. As such, they face acute threats of displacement due to a range of challenges: an existing affordable housing crunch escalated by the influx of new residents, limited job opportunities, and low adaptive capacity of low-income populations to the changing climate and migration patterns.

The lack of affordable housing was widely discussed as a concern for low-income communities. It was viewed as the main reason why people were “finding themselves having to go further and further outside of the area” where they used to live. There has been little to no housing development in targeted communities due to construction costs and cumbersome permitting. What did get built was not affordable for the local first-time or even most step-up homebuyers. This problem, combined with the prevalence of second homes and short-term rentals, created a huge gap in the housing stock that can be rented or purchased by permanent residents (e.g., teachers, nurses, and small business employees). A broker from Caledonia County, VT, noted:

[We] had a problem with finding teachers, bus drivers, electricians… People to work at banks, people to work at the hotels, people to work at the ski mountain. It’s impossible to find, or very hard to find people to work… I think it’s similar to what our discussion was on the “to build affordable housing doesn’t make sense anymore.” It’s the same… We all want to have [small businesses] in our main street in the small towns. But if you can’t afford someone to come here to work there, it’s [a] challenge right now!

According to our experts, housing and rental prices nearly doubled in some areas within two years after peak COVID-19, contributing to “a steady increase in homelessness.” Vermont and Massachusetts saw a “crazy spike” in homelessness in areas where it was not common before. Unhoused populations are especially vulnerable to emergencies. For example, the flooding events in July 2023 severely impacted an encampment along the Connecticut River in the Northampton, MA area. Many from Western Massachusetts, Vermont, and Upstate New York underlined that the lower-income individuals in their communities were living within the floodplains, as the most affordable areas were typically the “most environmentally compromised locations.” A broker from Broome County, NY, explained how low-income communities ended up living in flood-impacted areas in Binghamton:

All the [flood-impacted] housing that was owner-occupied [after] the last two floods is no longer owner-occupied. Somebody has bought it. Somebody has smacked it back together. And now it’s rented out to the people that have the least options.

Lower-income groups have lower financial capacity to adapt to environmental and demographic changes in rural communities. Housing experts, mostly working with low- and moderate-income groups, shared that it was not easy for these populations “to pick up and move,” even though they were suffering. Even with some housing incentives, there was an increasing number of tenants in rural areas who could not afford other crucial services—e.g., electric bills reaching $500/month and heating costs. In case of losing their residences due to a natural hazard or eviction, the disadvantaged groups usually had “nowhere else to go” and might end up unhoused.

The housing experts noted that unless action was taken to improve lower-income people’s adaptive capacity, historic patterns would continue. The wealthier populations, companies, and land speculators would find “the easiest way to comfort” by increasing their resilience to change, while historically disadvantaged populations would remain more vulnerable. “Collective action” was one solution noted by our participants to prevent the private sector from taking over the development in rural areas, thereby continuing historical patterns and leaving disadvantaged communities behind. Communities, governments, the private sector, and other stakeholders need to work together to prevent further displacement from happening.

Rural areas, especially those offering amenities (e.g., natural, educational), may attract urbanites who escape from socioeconomic challenges faced in big cities and utilize technological changes such as remote working. These movements challenge various systems—housing, infrastructure, and socioeconomic equality—in receiving communities.

3.3. RQ3: Lessons for Strategic Regional Planning

The experts agreed on the key role of regional planning in guiding the efforts to turn population growth into opportunities for their communities. They argued that their communities were not suitable for population growth unless they altered the current policy approach, which lacks a broader vision of regional changes and is resistant to change in general. To them, these efforts first need to address already-existing issues that have been exacerbated by the population influx. They consistently discussed that planning for a longer horizon required policymakers to cultivate political will to understand changing drivers and outcomes of population mobility and get the “towns on board,” raising awareness on such problems. This innovative approach was argued to help regions achieve sustainable and balanced development, with communities better prepared for such movements.

The experts recommended revisiting plans to tackle the current “patchwork” of problems—i.e., the lack of affordable/attainable housing and insufficient/poor infrastructure—while also taking emerging socioeconomic inequalities into account. It was repeatedly underlined that the policies that are currently in place “can’t keep up with things today and let alone preparing for an influx of people.” The experts found the regulations—e.g., zoning regulations, large lots or frontage dimensions, and requirements about accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—too restrictive, which significantly hindered development in the towns. They understood the reasons behind these limitations, as well as their benefits for preserving their environmental resources and “small town spirit.” However, many argued that there is “an opportunity for them [policymakers]” to “recognize the housing crisis” in their communities and reassess their land use and zoning policies to increase the number of permits where necessary. Relaxing these strict requirements and incentivizing the development of affordable housing and rental units were found to be crucial to take “some pressure off our housing market” and better serve their communities that are already in need of affordable and attainable housing. As a housing expert from New Hampshire stated, the incentives need to include both the regulations and funding opportunities to help affordable housing developers function properly:

I’d say there’s a lot of policy, sort of, incentives that need to go. [...] We’ve touched on [...] points, or the financial feasibility piece with developers. [...] Whether that looks like grants or lower interest loans, or some of the other financial tools, that states can use to incentivize the specific types of development they need.

The common advice for planning efforts was to improve the “decaying” infrastructure in a way that also enhances resilience. The roadways, usually outdated and poorly maintained, needed to be improved and viably utilized. The experts argued that both existing residents and the newcomers aspire to live in less car-dominant settlements where they can safely walk or bike for their daily activities. They call for incentives to provide more sidewalks, bike lanes, and better public transportation opportunities to make these small towns more viable and sustainable. Similarly, current sewer systems, typically relying on septic tanks, need to be replaced by treatment systems to enable denser development. Some regulations to manage stormwater, such as introducing disincentives or taxing impermeable surfaces within properties near Lake Champlain, Vermont, were found to be useful for flood resilience. The discussions underlined the need for enhancing long-term resilience, as summarized by a housing official from New Hampshire:

[Planning should focus on] making sure that you [the towns] are building in places that are not in floodplains [...] at least to the best you can. So, the resiliency planning, that’s a [...] buzz topic for a lot of communities right now. It’s figuring out, “okay, well, what makes the most sense for our long-term plan? Where do we want to see growth? And then how do we incentivize the growth we want to see in the areas we want to see it?” And just to make sure that’s all worked in there, the population pieces, the environmental pieces, demographic pieces, transportation... All of it.

The participants stated that their governments are “the biggest hurdle to any sort of change.” Policymakers usually lack the political will to adopt a visionary perspective, and there is “no wiggle room” to “plan ahead” for future issues. As put by a housing expert from Maine, the communities needed to have “people elected who are aware” of the changes that are “beyond their political boundaries.” Policymakers need to look beyond “here and now” and work collaboratively with other affected jurisdictions to develop a comprehensive understanding of emerging drivers of population mobilities in their region.

Local experts were aware of the barriers that might prevent policymakers from developing a planning approach for the longer horizon and even addressing the existing issues. They stated governments functioned very slowly, especially at the local level, due to the lack of resources and red tape. They mentioned that “municipal planning staff were already overworked,” with employees having to do multiple jobs and, and lacking expertise in some areas. From the perspective of affordable housing developers, it would take them “from five to seven years to build the project,” as they needed to overcome many bureaucratic steps at the government level. As put by a housing expert from Massachusetts, who previously worked as a local government official:

Government moves slow. Sometimes at a snail’s pace, especially when you’ve got a gazillion people that need to check the box before you can do anything. [...] You need to have a plan, and then you have to find the money, and then you have to get city council approval, and it’s just a lot of steps to make anything happen.

Regional planning efforts may also be challenged by the fragmented structure of government authority in the NE. It was underlined that rural NE towns typically had a high level of authority in planning actions such as local land use and zoning decisions. The communities usually “stifle the growth” in rural areas by resisting the suggestions that would change their “quaint little” towns. Local officials typically serve for a long time, “run” the government through their long-established methods, and are usually reluctant to comply with state mandates, even simpler demands “such as trainings.” The residents “rallied against” higher density or commercial development due to “cultural biases” with a “NIMBY—not in my backyard” mentality against affordable housing. A housing expert from Vermont underlined the misconception of density, described the rural growth dilemma as a “chicken and egg” problem, and added:

We have declining school enrollment, and so the schools are closing, you know. We do need more people to pay into the system, but we also need to make those investments in housing and infrastructure. So that there’s this place for them to come. And you know, in Vermont, there, there are still contingents who think like, we’re actually out of space, or we’ll lose our rural character if we build any more. But Vermont could double its population density and still be less dense than Tennessee.

According to the local experts, regional planning for long-term population movements driven by environmental hazards requires planners to be on guard with the right timing, act in collaboration with state- and local-level governments and ensure community engagement. Planners should not “jump too quickly” and need to account for the right timing, as the demand for policy change is not high yet. On the other hand, if the communities wait too long without a “contingency plan,” it would be too late and costly to adapt to the changes in demand. State and local governments should seek consensus by working collaboratively on understanding the needs of the communities, identifying potential growth areas, and revisiting their strategies on a timely basis. A housing expert from New Hampshire underlined the need for community engagement, which was repeatedly described as key to communicating the risks and benefits, building trust, and making the change happen:

The community engagement piece is incredibly important. [...] People don’t like change, period. So, [...] if you can hear them talk about what they want to see and help visualize what sort of policy decisions can help them get there, you know, you can have some success. Because I think if you ask a lot of people, they will bring up the same topics. They’ll bring up the fact that they’re concerned about their community... That they won’t be able to live there; that their kids won’t be able to live there; that, you know, their coffee shop is shutting down as well. But then a specific development might come forward. And [they are] like, “well, that’s not the right place for that. [It] is really important, making sure people understand, sort of, what the benefit is. Because their biggest asset, if they’re a homeowner, is their home, and they’re nervous about anything that would potentially harm that.

4. Discussion

Our study contributes to the existing body of literature on COVID-19-related mobility by adopting a mixed-methods approach that models secondary data and also analyzes the first-hand qualitative data collected directly from affected communities. To our knowledge, it is the first study exploring the ground truth by collecting qualitative data in the communities impacted by peak COVID-19-induced population movements in the US context, with a specific focus on the implications for regional planning. Also, in the broader perspective, the findings of this study may alert planners and policymakers and guide planning efforts to achieve sustainable and just outcomes of such movements driven by similar environmental factors (e.g., extreme heat and flood risk).

This study supports findings by other studies that COVID-19 era movers were the urbanites who fled populous metro areas such as New York City and Boston in the NE region, and particularly second homeowners. The top receiving areas were predominantly rural states such as Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire at the peak of the pandemic in 2020. Our county-level analysis revealed that the majority of the movers were moving within the NE region, and there was an “urban exodus” from highly populous counties in metro areas when compared to pre-pandemic (2018) values. Natural amenities did not have a strong effect on the influx, probably because heavily populated coastal counties also rank high in natural amenities based on the USDA amenity scale.

Our case study data supported the worries about the increasing housing costs, leading to lower availability [49,57], and an imbalance between the purchasing power of current residents and newcomers [58]. Receiving communities were not able to sustain the availability of the housing market for the locals, as they no longer could compete in the market dominated by wealthier, often cash buyer urbanites outbuying the properties in the rural NE. Services such as primary education were overburdened. More importantly, locals were worried about their aging population and the shortage of workforce (especially nursery and childcare workers) to sustain the necessary services, which was an already-existing problem exacerbated by the lack of workforce-priced housing in the area. Rural NE towns were struggling with poor infrastructure capacity, particularly sanitary and stormwater systems, and emergency services, which were also being challenged by the Great Flood of July 2023, as well as many other unnamed flooding events.

The findings verified the warnings about disproportionate impacts of disaster-driven movements on disadvantaged populations in receiving communities [69]. The concerns about potential gentrification in rural NE (see, for instance, [51]) were also validated by our findings. Many NE rural communities experienced significant tension between the (generally) wealthier newcomers and locals. Some places have seen an increase in displaced and unhoused populations, which was connected to the housing crunch.

Based on our discussions with the experts, we argue that the pressure receiving communities faced during the COVID-19 era migration alerts us about future challenges that may arise in areas that receive migration driven by various environmental factors and, in particular, climate-related hazards. Environmental changes, both slow and rapid, are likely to push migration not only to traditional attraction points (big cities, metro areas) but also to rural areas, especially with the help of technological changes enabling remote work.

The good news is that communities can prepare for desired outcomes from the arrival of new residents if these changes are well understood and planned ahead of time. Regional planning has a key role in this regard, creating more opportunities for a smooth transition rather than a shock. Our focus group participants did not call out strategic planning or scenario planning by name as key steps, but the conditions they noted—uncertainty, the need for quick responses, and community engagement, as well as multi-scalar collaboration—are suited to the strengths of strategic planning, particularly as undertaken with scenario planning. This kind of proactive and preparatory planning requires an innovative approach involving a multi-step process accounting for the evolving nature of domestic migration (e.g., climate-induced migrations, socio-technological drivers) while also addressing entrenched problems in smaller communities, which can turn into crises with even slight increases in population. Experts think collaboration among various levels of government would help local planners, who typically lack resources and political will to plan for a longer horizon. Planning with longer time frames was seen as crucial, as the demand for policy changes on the problem is not yet high among the communities. Community education and engagement were recommended by the local experts to be able to build trust and act on the problem. Rural planning may benefit from planning with and for the communities by communicating the changes in migration trends and understanding their current needs and expectations in terms of receiving newcomers, which would guide the planning processes.

A good starting place may be revisiting existing planning tools, such as zoning and land-use regulations, rather than trying to reinvent the wheel. Planning for a longer horizon can guide the efforts to update local plans that might be outdated and fail to reflect the current and evolving needs of the communities. Incorporating, or at least monitoring, the impacts of larger-scale environmental change on regions and communities can make a difference in achieving sustainable outcomes in the long run. Such efforts can be channeled towards increasing the supply of and access to affordable housing, strengthening infrastructure capacity, and taking steps to otherwise increase climate resilience and offer the types of services that help integrate newcomers into a new community. Potential receiving communities may also need to extend their financial and staff capacity to better adapt aging infrastructure and public services to handle future natural catastrophes. Lower-income populations in receiving communities are especially vulnerable, with very limited adaptive capacity to either move out of harm’s way or cope with the changes in place. The communities with new—typically wealthier—taxpayers face the threat of becoming less and less socioeconomically diverse if they abide by their existing regulations that limit affordable and attainable housing.

Enhancing housing and infrastructure capacity may not be easy for small towns. Although some may perceive the countryside as almost limitless, reality paints a different picture in rural NE. Developable land in the Northeast is limited due to a combination of natural features, regulatory restrictions, and insufficient infrastructure. Many towns are located close to environmental conservation areas such as forests, water bodies, wetlands, and farmlands with restrictive zoning. Denser, newer subdivisions are difficult to site without sewage treatment plants. These conditions not only limit capacities to absorb incoming populations but also hinder innovative solutions such as affordable housing, rental units, and mixed-use areas, which may potentially increase climate resilience.

It is important to note that our case study findings mainly depend on the perspectives of a group of local housing experts who volunteered to participate in focus group discussions. Studies with a larger group of experts (e.g., regional planners, other infrastructure practitioners) in different research settings may further advance our knowledge on population mobility towards rural areas, environmental drivers, and outcomes of such movements, as well as their implications for regional strategic planning in affected areas.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigate the population movement trends during the peak COVID-19 years and their outcomes for the receiving communities through the eyes of local experts in the NE. We find that in the wake of COVID, urbanites from mainly bigger cities and metro areas moved to predominantly rural areas, and the influx took a significant toll on receiving communities. We argue that the COVID-19 experience illuminates potential outcomes of other sharp shocks for receiving communities. Big cities and metro areas, the traditional hubs of resources, are no longer the only attraction points. Movements—driven by various environmental hazards (e.g., disasters, repetitive or slow-onset environmental hazards such as wildfires, droughts) and socioeconomic factors (e.g., housing crises)—may push populations toward destinations that are not historically accustomed to population influx. These changes significantly challenge the infrastructure and social systems in small communities that may benefit from regional planning addressing already-existing problems and understanding evolving drivers and outcomes of population mobility.

Although we think that COVID-era movements are generally similar to what we might expect from other environmentally driven mobilities, we are cognizant of potential differences and other inferential biases. COVID-era migrants in the Northeast tended to be from upper or upper-middle-income households. Wealth affords one the ability to move. However, this does not mean that all types of future movements will induce movement from a similar group of population or will pose the exact same outcomes for the communities. Our research focuses on the initial phase of COVID-19 migration, whereas the return migration trends may reveal different results. Further research focusing on longer-term effects of such movements, exploring relocations of a more diverse population, is likely to reveal additional insights into the drivers and outcomes of such movements for receiving communities.

These findings, unfolding the experiences of receiving communities during an unprecedented influx toward rural areas, present a warning and an opportunity to prepare for a future of more mobility in response to hazards of many kinds. Rural communities have the potential to beneficially host movers only if they plan for just and sustainable outcomes now, which can carry forward to the future. Regional strategic planning that oversees and guides these efforts can prepare communities for sustainable and just outcomes in the long run. Through an innovative and proactive approach, regional planning can incorporate the evolving nature of domestic migration in demographic modeling and resulting policy choices, creating better outcomes for receiving communities and reducing burdens on socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. Meanwhile, addressing the existing challenges to attainable/affordable housing supply, increasing climate resilience, and enhancing the integration of newcomers into receiving communities could make the difference between crisis and opportunity (as discussed in [70]). Much of this we know how to do, even if implementation is imperfect at best. The rapid flux of the COVID-19 era highlights that other environmental drivers, such as climate-induced hazards, create greater uncertainty about the timing and amount of population that should be expected, and the ways that change may bring opportunities and challenges to areas outside of urban centers. Practices that incorporate uncertainty into longer-horizon planning efforts while working within the limited governance capacity of local and especially rural authorities are essential. COVID-19 was a unique moment, but it also brought a window into possible futures. Planning can use that window to prepare communities for a climate-changed future.

Author Contributions

O.D.K. confirms responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. E.I. confirms responsibility for the following: grant acquisition, study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. H.R. confirms responsibility for the following: grant acquisition, study conception and design, data analysis (i.e., demographic data), and manuscript preparation. P.S. confirms responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. E.H. confirms responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant 016949-00002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst Human Research Protection Office (HRPO) and Institutional Review Board (IRB) (IRB Approval 4378—Climate Migration in New England: Developing Infrastructural and Socioeconomic Capacity of Receiving Communities to Address Climate Migration).

Informed Consent Statement

The participants signed written consent (through electronic signature) prior to participating in focus group discussions.

Data Availability Statement

The data and codebook that support the findings of this study are available at University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, ScholarWorks@UMassAmherst (URL: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14394/54696, accessed on 17 January 2025, DOI: 10.7275/w4cf-nn19).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Argent, N.; Plummer, P. Counterurbanisation in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic in New South Wales, 2016–21. Habitat Int. 2024, 150, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzow, A. Exodus from Urban Counties Hit a Record in 2021; Economic Innovation Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haslag, P.H.; Weagley, D. From LA to Boise: How Migration Has Changed During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2022, 59, 2068–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Su, Y. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Demand for Density: Evidence from the U.S. Housing Market. Econ. Lett. 2021, 207, 110010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, A.; Bloom, N. The Donut Effect of COVID-19 on Cities (No. 28876); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28876 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Teicher, H.M.; Phillips, C.A.; Todd, D. Climate Solutions to Meet the Suburban Surge: Leveraging COVID-19 Recovery to Enhance Suburban Climate Governance. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, M. Record Wave of Americans Fled Big Cities for Small Ones in 2023. Bloomberg, CityLab. 7 May 2024. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-07/record-wave-of-americans-fled-big-cities-for-small-ones-in-2023 (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Schultz, J.; Elliott, J.R. Natural Disasters and Local Demographic Change in the United States. Popul. Environ. 2013, 34, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Wisconsin-Madison. Many Rural Americans Are Still “Left Behind”. University of Wisconsin–Madison, Institute of Research on Poverty. Available online: https://www.irp.wisc.edu/resource/many-rural-americans-are-still-left-behind/#_edn3 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Leichenko, R.M.; Solecki, W.D. Climate Change in Suburbs: An Exploration of Key Impacts and Vulnerabilities. Urban Clim. 2013, 6, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C. Who Are America’s “Climate Migrants,” and Where Will They Go? Urban Institute. Available online: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/who-are-americas-climate-migrants-and-where-will-they-go (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Hauer, M.E.; Evans, J.M.; Mishra, D.R. Millions Projected to Be at Risk from Sea-Level Rise in the Continental United States. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Nkonya, E.; Galford, G.L. Flocking to Fire: How Climate and Natural Hazards Shape Human Migration Across the United States. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2022, 4, 886545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K. People and Coastal Ecosystems Adapt to Relative Sea-Level Rise. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1510–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Dilkina, B.; Moreno-Cruz, J. Modeling Migration Patterns in the USA Under Sea Level Rise. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Lustgarten, A.; Goldsmith, J.W. New Climate Maps Show a Transformed United States; ProPublica: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lustgarten, A. How Climate Migration Will Reshape America. NY Times Magazine. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/09/15/magazine/climate-crisis-migration-america.html (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Coin, G. Upstate NY Cities Named Among Best ‘Climate Havens’ as the World Grows Hotter. Syracuse. Available online: https://www.syracuse.com/weather/2021/02/upstate-ny-cities-among-best-climate-havens-as-the-world-grow-hotter.html (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Jacobson, L. Americans are Fleeing Climate Change—Here’s Where They Can Go. CNBC. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/04/21/climate-change-encourages-homeowners-to-reconsider-legacy-cities.html (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Yoder, K. Fleeing Global Warming? ‘Climate Havens’ Aren’t Ready Yet. WIRED. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/fleeing-global-warming-climate-havens-arent-ready-yet/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Massey, D.S.; Arango, J.; Hugo, G.; Kouaouci, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Taylor, J.E. Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1993, 19, 431–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, H.; Castles, S.; Miller, M. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 6th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnifield, M.P. The Dust Bowl: Men, Dirt, and Depression; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C.J.L.; Piracha, A. Strategic Planning for Urban Sustainability. Land 2025, 14, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L.; Balducci, A.; Hillier, J. Situated Practices of Strategic Planning: An International Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Savini, F. Strategic Planning for Degrowth: What, Who, How. Plan. Theory 2025, 24, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infield, E.; Kuru, O.D.; Cotter, A.; Renski, H.C. Insights for Receiving Communities in Planning for Equitable and Positive Outcomes Under Climate Migration; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper; WP24EI1; Lincoln Institute for Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kuru, O.D.; Ganapati, N.E.; Marr, M. Perceptions of Local Leaders Regarding Post-Disaster Relocation of Residents in the Face of Rising Seas. Hous. Policy Debate 2022, 33, 1124–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid Uddin, K.A.; Piracha, A. Unequal COVID-19 Socioeconomic Impacts and the Path to a Sustainable City and Resilient Community: A Qualitative Study in Sydney, Australia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2474184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, H.; Maire, Q.; Cook, J.; Wyn, J. Liminality, COVID-19 and the Long Crisis of Young Adults’ Employment. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2023, 58, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, M.; Bandhold, H. Scenario Planning: The Link Between Future and Strategy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Krys, C. Scenario-Based Strategic Planning: Developing Strategies in an Uncertain World; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bijak, J. From Uncertainty to Policy: A Guide to Migration Scenarios; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zehner, E. How to Embrace and Navigate Uncertainty; Lincoln Institute for Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/2020-06-scenario-planning-pandemic-navigating-managing-uncertainty/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Goodspeed, R. Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions: Managing and Envisioning Uncertain Futures; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olgun, R.; Cheng, C.; Coseo, P. Nature-Based Solutions Scenario Planning for Climate Change Adaptation in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Land 2024, 13, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T.; Kliimask, J.; Kalm, K.; Zālīte, J. Did the Pandemic Bring New Features to Counter-Urbanisation? Evidence from Estonia. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsubo, M.; Nakaya, T. Trends in Internal Migration in Japan, 2012–2020: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incaltarau, C.; Kourtit, K.; Pascariu, G.C. Exploring the Urban-Rural Dichotomies in Post-Pandemic Migration Intention: Empirical Evidence from Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 111, 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, F.; Calafiore, A.; Arribas-Bel, D.; Samardzhiev, K.; Fleischmann, M. Urban Exodus? Understanding Human Mobility in Britain During the COVID-19 Pandemic Using Meta-Facebook Data. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Z.; Lang, W. Understanding Urban Growth and Shrinkage: A Study of the Modern Manufacturing City of Dongguan, China. Land 2025, 14, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN DESA (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs). International Migration 2020 Highlights. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/international_migration_2020_highlights_ten_key_messages.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Brouwer, A.E.; Mariotti, I. Remote Working and New Working Spaces During the COVID-19 Pandemic—Insights from EU and Abroad. In European Narratives on Remote Working and Coworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multidisciplinary Perspective; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- González-Leonardo, M.; Rowe, F.; Fresolone-Caparrós, A. Rural Revival? The Rise in Internal Migration to Rural Areas During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Who Moved and Where? J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidi, S.; Sabouri, S.; Ewing, R. Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic? Early Findings and Lessons for Planners. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2020, 86, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, C. Critical Commentary: Repopulating Density: COVID-19 and the Politics of Urban Value. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1548–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Compact Living or Policy Inaction? Effects of Urban Density and Lockdown on the COVID-19 Outbreak in the US. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1588–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, D. The Rural Migration Trend: What to Make of It, Why It’s Happening and Where It’s Headed. Available online: https://www.aem.org/news/the-rural-migration-trend-what-to-make-of-it-why-its-happening-and-where-its-headed (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Petersen, J.K.; Winkler, R.L.; Mockrin, M.H. Changes to Rural Migration in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rural Sociol. 2024, 89, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.L.; Petersen, J. Fewer People Are Moving Out of Rural Counties Since COVID-19. Amber Waves, 26 September 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, P.B.; Frost, W. Migration Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of New England Showing Movements down the Urban Hierarchy and Ensuing Impacts on Real Estate Markets. Prof. Geogr. 2023, 75, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumenti, N. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed Household Migration in New England. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Available online: https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/new-england-public-policy-center-regional-briefs/2021/how-the-covid-19-pandemic-changed-household-migration-in-new-england.aspx (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Kane, K. How Have American Migration Patterns Changed in the COVID Era? Growth Chang. 2024, 55, e12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C. Retaining Social and Cultural Sustainability in the Hudson River Watershed of New Yor, USA: A Place Based Participatory Action Research Study. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2022, 15, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevarez, L.; Simons, J. Small–City Dualism in the Metro Hinterland: The Racialized “Brooklynization” of New York’s Hudson Valley. City Community 2020, 19, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.; Tsai, T.-H. The Role of Amenities and Quality of Life in Rural Economic Growth. In Environmental Amenities and Regional Economic Development; Cherry, T., Rickman, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dimke, C.; Lee, M.C.; Bayham, J. COVID-19 and the Renewed Migration to the Rural West. West. Econ. Forum 2021, 19, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.A.; Rahe, M.L.; Van Leuven, A.J. Has COVID-19 Made Rural Areas More Attractive Places to Live? Survey Evidence from Northwest Missouri. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 520–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bański, J. Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland. Land 2025, 14, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Đoković, F.; Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Vukolić, D.; Mandarić, M.; Dašić, G.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Mićović, A. Pandemic Boosts Prospects for Recovery of Rural Tourism in Serbia. Land 2023, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F.; Castro, B. State-Led Tourism Infrastructure and Rural Regeneration: The Case of the Costa Da Morte Parador (Galicia, Spain). Land 2025, 14, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Dept. of Commerce; Bureau of the Census. County-to-County Migration Flows: 2016–2020 ACS. 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/geographic-mobility/county-to-county-migration-2016-2020.html (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Statistics of Income (SOI) Tax Stats—Migration Data. 2020. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-migration-data (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- U.S. Dept. of Commerce; Bureau of the Census. Decennial Census by Decade (1990, 2000, 2010, 2020). 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade.html (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Economic Research Service. Urban-Rural Continuum Codes. 2023. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA) Economics: National Ocean Watch (ENOW). Defining Coastal Counties. 2010. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/data/digitalcoast/pdf/defining-coastal-counties.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA Natural Amenities Scale. 2023. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/natural-amenities-scale (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- New NY Broadband Program. New York State. Available online: https://broadband.ny.gov/new-ny-broadband-program (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Marandi, A.; Main, K.L. Vulnerable City, recipient city, or climate destination? Towards a typology of domestic climate migration impacts in US cities. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 11, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, H.M.; Marchman, P. Integration as Adaptation: Advancing Research and Practice for Inclusive Climate Receiving Communities. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2024, 90, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]