Abstract

This study examines how platformized e-commerce logistics reshapes urban land use at the neighborhood scale, using Shanghai as an empirical case. It argues that last-mile logistics infrastructure operates through two intertwined mechanisms: as physical service nodes that generate localized pedestrian flows sustaining neighborhood retail, and as neighborhood-level execution points within a digitally coordinated logistics system that produces citywide substitution pressures and restructures commercial spaces, particularly community-oriented shopping malls. Theoretically, the study advances platform and logistics urbanism by reconceptualizing last-mile infrastructure as a dual-role urban system with scale-dependent land-use effects. Methodologically, it combines street-segment regression analysis with shopping-mall case studies to link logistics proximity to fine-grained spatial outcomes. Empirically, the findings reveal complementary effects for street retail alongside accelerated restructuring and functional repurposing in community malls—patterns not captured by uniform displacement models. Planning analysis further identifies a governance mismatch in Shanghai’s 2017–2035 Master Plan, underscoring the need for platform-responsive planning to address emerging hybrid commercial–logistics spaces.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, cities worldwide have witnessed the rapid proliferation of e-commerce and its associated logistics infrastructures. Distribution centers, parcel lockers, neighborhood delivery stations, and micro-fulfillment hubs have become common features of the urban landscape, forming a new layer of facilities that mediate the circulation of goods between digital marketplaces and consumers. These spatial nodes are closely intertwined with the rise of digital platforms that manage transactions, logistics coordination, and real-time data flows. As a result, the boundaries between online and offline commerce are increasingly blurred, and new types of spaces devoted to storage, sorting, and delivery have emerged across urban neighborhoods [1,2,3,4,5].

E-commerce originally referred to the digitalization of retail transactions. As digital firms evolved into platforms coordinating transactions, logistics, and data across multiple actors, e-commerce became embedded within the broader platform economy—a new organizational logic of capitalism in which value derives from managing digital infrastructures, algorithms, and multi-sided networks rather than direct production [1,4]. Within this framework, platformized e-commerce—exemplified by Alibaba, JD.com, and Pinduoduo—integrates logistics, payment systems, data analytics, and user management into a socio-technical system that reorganizes economic and spatial processes. The resulting land-use changes, including retail decline and the proliferation of logistics hubs, are thus outcomes of platform-mediated spatial organization, a defining feature of platform urbanism [6,7].

Recent scholarship increasingly examines how the platform economy reshapes spatial structures, regulatory geographies, and urban land-use systems. Studies show that the diffusion of e-commerce is uneven, shaped by infrastructure quality, income, and population density, with coastal or economically advanced regions hosting higher concentrations of digital logistics facilities [8,9]. Research on rural and peri-urban China further demonstrates that digital commerce accelerates the conversion of agricultural land into mixed industrial–commercial uses, drives rural industrial upgrading, and supports urban–rural spatial integration [7,10,11,12,13]. Collectively, this work shows that the platform economy functions as a spatial mechanism channeling goods, capital, and labor in ways that reshape land allocation and functional zoning.

At the urban scale, scholars have documented how platform ecosystems such as Amazon, Alibaba, and JD.com transform retail geographies, logistics landscapes, and urban form. Online retail reduces demand for malls and high-street retail while expanding warehouses, fulfillment centers, and delivery hubs [14,15,16]. These shifts redirect land demand from central commercial cores to suburban and peri-urban areas, producing hybrid retail–logistics spaces. Such transformations signal a broader shift in urban spatial logic—from site-based production to flow-based organization—enabled by platform infrastructures and data logistics [1,6,7].

Despite growing research on the spatial restructuring of logistics and retail under e-commerce, most studies remain at the regional or macro scale. Little is known about how last-mile facilities affect neighborhood-scale land use and retail vitality. Moreover, although the decline of traditional retail has been widely observed, the relationship between platform logistics and the transformation of large shopping malls remains largely unexplored. Addressing these gaps, this study focuses on Shanghai, China. The rapid growth of platformized e-commerce logistics in Shanghai has intensified a series of emerging land-use challenges, including shifting street-level retail dynamics, increasing hybrid commercial–logistical activities, and the functional restructuring of community shopping malls. As one of China’s most advanced platform economies, Shanghai offers a representative and analytically significant case for examining neighborhood-scale land-use transformations under platform urbanism [17,18]. The city thus provides a representative setting for examining how the expansion of platform infrastructures reshapes micro-scale urban retail landscapes.

The main research question is two-fold. First, how does the spatial expansion of platformized e-commerce logistics—represented by Cainiao last-mile delivery stations and parcel networks—reshape neighborhood-level land use and retail vitality in Shanghai? Second, how can urban planning better anticipate and adapt to the spatial transformations driven by platform logistics, ensuring a more balanced and sustainable integration of retail, residential, and logistical functions within the framework of the Shanghai City Master Plan (2021–2035)?

To capture the full spatial consequences of platformized e-commerce logistics, this study examines both street-level retail segments and community-oriented shopping malls. These two commercial forms represent distinct positions within the urban commercial hierarchy and therefore interface with platform logistics through different mechanisms: neighborhood retail streets interact closely with everyday parcel pickup and delivery flows, whereas shopping malls encounter platform-driven competition for standardized goods and experience deeper shifts in consumption behavior. Analyzing both scales allows the study to uncover differentiated mechanisms through which digital platforms reorganize commercial land use and reshape neighborhood-level spatial dynamics. Using spatial analysis of street-level vacancy and qualitative investigation of mall adaptation, this study links platform logistics with neighborhood land-use transformation through the lens of platform urbanism, combining insights from logistics urbanism and land-use transformation theory. This study develops a conceptual framework that explains how digital infrastructures reorganize urban space by introducing platform-induced spatial substitution and hybrid spatiality—mechanisms that explain how e-commerce logistics reshape retail, residential, and logistical interfaces.

Extending this framework, the paper incorporates the idea of platform-responsive planning, emphasizing how urban planning can adapt zoning and land-use policy to the hybrid spatial forms emerging from platformized urban development. We focus on the Master Plan because it is the authoritative strategic planning document guiding Shanghai’s urban transformation during the period studied and therefore offers the most appropriate basis for evaluating how planning responds to platformized e-commerce logistics. Methodologically, this study departs from previous macro-scale analyses of e-commerce and land use, which rely mainly on provincial or city-level datasets. It introduces a micro-scale, mixed-method approach that combines field-observed street-segment data on retail vacancy with GIS-based measures of proximity to platform logistics facilities and qualitative case studies of shopping malls, directly linking platform logistics to neighborhood land-use transformation.

This paper argues that platformized e-commerce logistics reshapes urban land use through two intertwined mechanisms: Cainiao stations act simultaneously as physical service nodes that generate localized pedestrian flows sustaining neighborhood retail, and as neighborhood-level execution points within a digitally coordinated logistics system that produces citywide substitution pressures and restructures community shopping malls. This dual mechanism explains the divergent, multi-scalar spatial transformations observed in Shanghai and advances theoretical understandings of platform urbanism beyond a uniform displacement model. It further contends that current planning frameworks remain poorly aligned with these emerging spatial dynamics, underscoring the need for platform-responsive planning tools that recognize hybrid commercial–logistics spaces and digitally coordinated delivery systems.

2. Theoretical Framework: Platformized E-Commerce, Land-Use Transformation, and Planning Responses

2.1. Conceptualizing the Platformized E-Commerce Economy

The rise of platformized e-commerce marks a major shift in how production, exchange, and spatial organization are coordinated in the digital era. Scholars conceptualize the platform economy as a new mode of economic organization in which digital intermediaries restructure flows of goods, information, and services across diverse actors and territories. Kenney and Zysman [1] describe platforms as a data-driven coordination system that replaces firm-based organization by mediating multi-sided interactions and controlling the infrastructures through which value is created and captured. Rather than producing goods, platforms profit by managing flows and positioning themselves as essential nodes in digital ecosystems. Srnicek [4] characterizes this as “platform capitalism,” where control over data, algorithms, and network effects forms the basis of rentier accumulation.

A growing body of work highlights the spatial and infrastructural implications of this transformation. Plantin et al. [6] argue that platforms function as infrastructural systems whose digital coordination requires tangible spatial extensions such as data centers, warehouses, and delivery networks. Nahiduzzaman et al. [16] similarly conceptualize e-commerce as a spatial coordinator that redistributes land demand, while Wang, Xu, and Liu [7] describe the platform economy as a techno-spatial formation embedding digital infrastructures within territorial and social contexts. Taken together, these perspectives show that platformized e-commerce is not only a technological or retail innovation but a spatial–economic system integrating digital and material infrastructures, shifting urban organization from site-based production to flow-based logistics.

In this paper, platformized e-commerce is understood as the spatial expression of this platform logic: a system fusing digital intermediation with physical distribution. Platforms such as Alibaba’s Cainiao mediate consumption while producing logistics infrastructures that reshape urban space. This dual role—informational coordination and material production—underpins the study’s analytical focus on how last-mile logistics facilities influence neighborhood retail vitality and land-use patterns in Shanghai.

2.2. Hypothesizing the Impact of Platformized E-Commerce on Land Use in Chinese Cities

2.2.1. Platform Urbanism

This framework is first grounded in platform urbanism, which conceptualizes cities as spaces increasingly structured by digital platforms that mediate flows of goods, information, and people [19,20]. Visser & Lanzendorf [21], a precursor to later “platform urbanism” research, illustrate a continuity from ICT-enabled e-commerce to today’s platform-mediated land-use transformations, which is characterized by digitally coordinated systems that reshape the flows of goods, people, and information, thereby reorganizing land demand for logistics, warehousing, and related urban functions. Visser & Lanzendorf [21] summarize these processes using mechanistic pathways. First, functional substitution occurs as traditional retail floor space is replaced by distribution depots and fulfillment facilities that serve online markets. Second, spatial reallocation takes place as commercial activity shifts from centrally located retail districts toward suburban or peripheral logistics zones, reflecting the changing geography of accessibility and land value. Finally, an accessibility divergence emerges, wherein urban consumers benefit from enhanced convenience and rapid delivery, while rural and remote areas face relative exclusion from these digital service networks.

The concept of platform urbanism emerges from critical urban geography to describe a new phase in the relationship between technology, capital, and the city, marked by the growing power of digital platforms to mediate urban life. Platforms are not merely technological innovations but socio-technical intermediaries and business arrangements that “automate market exchanges and mediate social action” [3,22,23]. Unlike earlier “smart city” systems designed for top-down oversight, platform urbanism is directly consumer-oriented, rapidly scalable through network effects and venture capital, and venture capital, and often antagonistic to government regulation [23,24].

Digital platforms such as Alibaba, Uber, or Airbnb exemplify this shift by transforming the everyday infrastructures of urban services—mobility, accommodation, and logistics—into data-driven, market-mediated operations. As Sadowski [23] notes, platforms have become an urban phenomenon precisely because they thrive in dense, heterogeneous urban environments where social interactions and transactions can be continuously mediated, monitored, and monetized. Cities, in turn, are reshaped as platforms insert themselves into the production and circulation of space, recasting urban systems as reservoirs of latent, underutilized assets waiting to be valorized.

From this perspective, platform urbanism is a new mode of spatial production, where digital coordination reshapes material space. Platforms simultaneously create digital and physical infrastructures that organize the circulation of goods, data, and capital [23]. Their value lies not in landownership but in mediating flows, turning urban environments into logistical networks. This logic drives the spatial restructuring seen in platformized e-commerce, as parcel stations, lockers, and micro-fulfillment nodes become embedded in neighborhood landscapes.

Taken together, these studies show that platform urbanism offers a unifying lens for understanding the spatial consequences of platformized e-commerce. It links global theories of digital capitalism with China’s distinctive urban restructuring, where density, planning institutions, and state–platform collaboration intensify the material footprint of digital infrastructures.

2.2.2. Land-Use Transformation and Logistics Urbanism

Technological regimes increasingly reshape the spatial organization of economic activities [25,26]. Within platform urbanism, this study introduces platform-induced spatial substitution and hybrid spatiality to explain how platform infrastructures reconfigure retail functions and blur boundaries between commercial, residential, and logistical land uses. Nahiduzzaman et al. [16] argue that platformized e-commerce restructures land-use patterns by shifting demand away from central retail toward warehousing, fulfillment, and logistics facilities, altering land-price gradients and driving suburban expansion as dispersed fulfillment nodes replace concentrated retail centers.

In China, recent studies clarify these dynamics by integrating platform economy theory with China-specific transformations in retail geography. Platforms reorganize land demand—through warehousing, dark stores, and parcel lockers—and reshape retail hierarchies [10,27,28]. Earlier, Zhang et al. [29] showed that platforms such as Taobao, Tmall, and JD.com coordinate flows of goods and consumers, restructuring commercial hierarchies and redefining physical retail. Their work underscores that e-commerce does not eliminate space but creates hybrid online–offline forms integrated into material structures. Rising land and housing costs further push firms to peripheral areas, producing new logistics hubs and e-commerce clusters [8].

Logistics urbanism provides an essential complement to this perspective [30,31]. Hesse [32] conceptualizes logistics urbanism as urbanization driven by circulation rather than proximity, with containerization and similar innovations producing logistics landscapes—warehouses, freight hubs, and airports—that extend urban economies. Danyluk [33] similarly describes the “logistical city” as a political-economic and spatial formation organized around the movement of goods, people, and information, with infrastructures of flow—ports, warehouses, transport corridors—forming dispersed yet connected nodes optimized for speed and efficiency [34,35]. Srnicek [4] further argues that platforms extract value by controlling digital and physical infrastructures, meaning contemporary land-use change increasingly reflects logistics and distribution imperatives rather than traditional retail or industrial logics.

In Chinese cities, these tendencies manifest through the deep interdependence between cyberspace and physical infrastructure, as digital flows depend on tangible networks of roads, warehouses, and delivery nodes, blurring urban–rural boundaries and embedding digital economies into material landscapes [8]. A central dimension of the platformized urban economy is the hybridization of land use, with logistics functions increasingly embedded within residential and commercial environments. He and Sun [36] show that express delivery stations exemplify this integration: embedded in high-density consumption areas, they intensify land use and transform neighborhoods into logistics-active spaces. Likewise, Ding et al. [9] highlight smart parcel lockers as material manifestations of platform logistics, embedding collection and delivery functions directly into residential settings and further blurring the boundaries between residential, commercial, and logistical land uses.

2.2.3. Planning Responses to the Platformized and Logistics-Oriented Urban Economy

The concept of platform-responsive planning extends the framework toward governance, arguing that spatial regulation must shift from fixed, function-based zoning to adaptive, network-aware, and data-informed approaches. Across the literature, several convergent directions define this emerging paradigm.

First, planning must evolve from static regulation to anticipatory and flow-based governance. Scholars emphasize that accelerating e-commerce and logistics flows make traditional land-use categories inadequate for managing hybrid, rapidly changing urban spaces [37]. Nahiduzzaman et al. [16] and Mohamad et al. [15] argue that planners should govern relationships among retail, logistics, and housing rather than fixed functions. Portwood [14] and Zhang et al. [29] similarly call for planning models that reflect the fluid spatial logic of platform economies, reframing accessibility around network connectivity within digital–logistical infrastructures.

Second, land-use flexibility and mixed-use adaptation are essential for accommodating hybrid commercial–industrial typologies. A wide body of work—including Portwood [14], Zhang [8], Wang et al. [10], and Xiao et al. [27]—demonstrates how platform urbanism blurs distinctions between commerce, logistics, and production. These studies argue for flexible zoning, adaptive land-use codes, and temporary-use permissions to support emerging spaces such as vertical logistics hubs, omnichannel centers, and livestreaming studios, positioning municipal flexibility as the institutional foundation of platform urbanism.

Third, digital indicators and institutional coordination are central to data-informed planning. Wang et al. [10], Nahiduzzaman et al. [16], and Jia [38] stress that platform economies cannot be governed without integrating real-time data on logistics demand, consumption flows, and platform activity into land-use monitoring systems. Effective governance also requires coordination across commerce, transport, and land-resource sectors to prevent spatial fragmentation and support balanced urban–rural development.

Fourth, planning must address the integration of logistics within everyday urban environments. As logistics functions penetrate residential and commercial fabrics, Visser and Lanzendorf [21] and Ding et al. [9] highlight the need for coordinated land-use and transport strategies that combine peripheral logistics hubs with embedded micro-logistics infrastructure such as parcel lockers and delivery stations. Xiao et al. [27] and Alizadeh and Farid [39] likewise show how platform logistics reorganize urban form, requiring updated zoning and infrastructure frameworks to manage traffic, environmental externalities, and service accessibility.

Fifth, platform-responsive planning must integrate sustainability and digital governance into land management. Cheng et al. [13] and Wang et al. [10] argue that digital participation can support sustainable land-use practices when combined with strong planning institutions, calling for reduced regulatory barriers, integration of digital data into environmental monitoring, and region-specific sustainability targets tied to digital logistics systems. Nahiduzzaman et al. [16] and Jia [38] extend this to urban governance, showing that digital transparency and traceability function as informal regulatory tools aligning platform activities with ecological goals.

Finally, planners must address both visible and invisible infrastructures of platform capitalism. Plantin et al. [6], Jia [38], and Xiao et al. [27] show that platform economies generate layered infrastructures—physical (warehouses, fulfillment and data centers) and informational (algorithms, fiber networks, governance systems)—that jointly shape spatial structure. Planning must therefore engage with these systems holistically, recognizing digital infrastructure as a determinant of land demand, logistics geography, and urban morphology, alongside traditional transport and land-use systems.

2.3. Developing Operational Hypotheses, Variables, and Frameworks

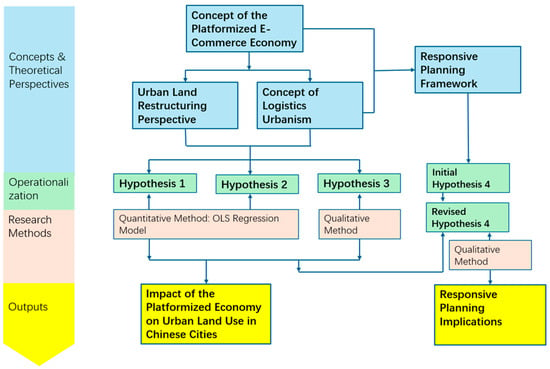

Drawing on the insights of platform urbanism, the urban land restructuring perspective, the concept of logistics urbanism, and the responsive planning framework, this study establishes a platformized and logistics-oriented hybrid framework. To operationalize this framework and test its applicability, a structured workflow was designed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research Workflow: Examining the Impact of Platformized E-Commerce on Urban Land Use and Planning Responses.

The analysis begins with the concept of the platformized e-commerce economy (Section 2.2.1), extended through the Urban Land Restructuring Perspective and Logistics Urbanism (Section 2.2.2), which together explain how technological change and logistics flows reorganize urban land functions and spatial form. Based on this framework, three hypotheses (H1–H3) examine the spatial effects of e-commerce logistics: H1 and H2 use OLS regression to test how proximity to last-mile facilities correlates with retail vitality, while H3 uses qualitative methods to assess impacts on shopping malls and neighborhood retail.

The Responsive Planning Framework (Section 2.2.3) informs a fourth hypothesis (H4) on planning responses to platform-driven spatial change. Developed conceptually and refined through findings from H1–H3, H4 is evaluated qualitatively to identify adaptive strategies and governance implications. Overall, this workflow integrates conceptual, empirical, and policy analysis to link platform and logistics urbanism with planning responses to the platform economy’s effects on urban land use in Chinese cities.

2.3.1. Developing Hypotheses 1–3 and Variables

This research adopts a micro-scale, neighborhood-based design: street segments (≈100 m) serve as observational units, with retail vacancy measured through field surveys and modeled against GIS-derived indicators of proximity to Cainiao service stations, road hierarchy, and accessibility. Neighborhood fixed effects provide local controls, allowing near–far comparisons within the same context. Complementary qualitative case studies of large shopping malls integrate foot-traffic counts and observations of functional repurposing, producing a mixed-method framework that bridges macro analyses of e-commerce with fine-grained, on-the-ground land-use change.

In this study, Cainiao Yizhan (Cainiao Stations) are used as spatial indicators of platform-mediated e-commerce infrastructure. As community-level logistics nodes, they perform intertwined functions that link digital retail flows to the material urban landscape. Operationally, they act as last-mile logistics facilities that centralize parcel collection, storage, pickup, and return services, reducing door-to-door delivery and increasing efficiency in the final segment of the e-commerce supply chain. Embedded within residential neighborhoods, commercial streets, university campuses, and township centers, these micro-scale sites (typically 10–30 m2) also operate as everyday community service spaces, offering conveniences such as bill payment, printing, and public announcements. At a broader systems level, they constitute a crucial layer of Alibaba’s platform infrastructure, connecting online marketplaces with physical logistics networks. Their spatial distribution and density therefore serve as a measurable proxy for the penetration and territorial reach of platformized e-commerce within Chinese cities. We have developed research problems and Hypotheses 1–2:

Research Problem 1: Does proximity to Cainiao last-mile logistics (stations/lockers) correlate with higher vacancy in traditional street-level retail?

Hypothesis 1. Street segments closer to a Cainiao station exhibit higher vacancy rates than segments farther away, controlling for accessibility and street hierarchy.

Research Problem 2: How do neighborhood characteristics—such as urban form (inner-ring vs. outer-ring) and the spatial concentration of Cainiao service stations (high-density cluster vs. low/none)—influence the relationship between platform logistics and retail vacancy?

Hypothesis 2a. The positive association between proximity to Cainiao stations and retail vacancy is stronger in inner-ring neighborhoods than in outer-ring neighborhoods.

Hypothesis 2b. The positive association between proximity to Cainiao stations and retail vacancy is stronger in neighborhoods with high Cainiao station density than in neighborhoods with few or no stations.

The proposed operational model is

In this model, if : segments near parcel stations have higher vacancy, suggesting substitution (delivery replaces walk-in shopping). If : segments near stations have lower vacancy, suggesting complementarity (stations draw foot traffic).

The dependent variable is the vacancy rate, which measures retail vitality or land-use activity on a street segment.

The independent variables, their meanings, data tape and references are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Independent variables and their associated information.

Research Problem 3: Has the expansion of platformized e-commerce logistics (represented by Cainiao service stations and parcel delivery ecosystems) contributed to the transformation or decline of large-scale shopping malls in Shanghai?

Hypothesis 3. The growth of platform logistics infrastructure corresponds with a visible reduction in the operational vitality of nearby large-scale shopping malls, reflected in partial closures, functional repurposing, or declining foot traffic.

2.3.2. Operationalizing the Responsible Planning Framework

Research Problem 4: How can urban planning respond to the land-use transformations and spatial restructuring induced by the expansion of platformized e-commerce logistics in Chinese cities?

Hypothesis 4. Urban planning in Chinese cities has not yet fully adapted to the hybrid land-use forms and decentralized spatial patterns generated by platformized e-commerce. Integrating insights from platform and logistics urbanism, responsive planning should evolve toward flexible, adaptive mechanisms that accommodate mixed commercial–logistical uses and neighborhood-scale digital infrastructures.

Based on Section 2.2.3, we have developed Table 2, listing planning issues, the practical implications for Shanghai’s master plan and the evaluation methods.

Table 2.

Initial Framework for Evaluating Planning Responses to Platformized E-Commerce in Shanghai’s 2017–2035 Comprehensive Plan.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Data Sources

This study integrates geospatial, statistical, and field-collected data to examine how platformized e-commerce logistics reshape land-use patterns and retail vitality in Shanghai. The core dataset consists of the geographic distribution of Cainiao’s last-mile service stations in 2020 and 2025, obtained from the official logistics data provider (iecity.com) and geocoded in Python 3.11. Subdistrict boundary data were initially acquired through a resale listing on the Xianyu platform; however, for the present study, all spatial boundary files have been verified and replaced with the official versions published by the Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. These authoritative district-level unit plans [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54] provide the legally valid subdistrict boundaries used for spatial mapping and ensure the accuracy and reliability of all subsequent analyses. Four spatial indicators were derived: stations per subdistrict, station density (per km2), percentage of land within 300-m buffers, and distance to the nearest station-free strip (≥300 m from any station).

To contextualize spatial accessibility and urban form, road networks, metro, and subdistrict base maps were incorporated. These quantitative datasets were complemented by field observations and photographic documentation at street and shopping-mall scales, enabling a mixed-methods approach that links platform logistics infrastructures with micro-scale land-use transformations.

3.2. Sampling Method

A stratified sampling strategy captured variation in Shanghai’s urban morphology and levels of platform logistics exposure. GIS overlay analysis identified twelve candidate subdistricts across Shanghai’s inner, middle, and outer ring roads, representing both historic mixed-use areas and newer residential compounds. Subdistricts were classified by Cainiao station density and buffer coverage into four types:

- (1)

- high-density clusters (≥4 stations and ≥40% of land within 300 m);

- (2)

- moderate/isolated exposure (1–2 stations or 10–40% coverage);

- (3)

- low/no exposure (≥80% of land beyond 500 m);

- (4)

- transitional frontier zones with sharply declining buffer coverage.

From these categories, four representative neighborhoods were selected—two with strong exposure and two with minimal or no exposure (Table 3). Within each neighborhood, 100-m street segments with active ground-floor commercial frontages served as observation units. Each neighborhood contributed fifteen to twenty-five segments, yielding a total sample of roughly one hundred. This design enables comparison between areas inside and outside the 300-m station influence radius while controlling for neighborhood heterogeneity using fixed-effects modeling.

Table 3.

Spatial characteristics of Cainiao station distribution across four sampled subdistricts in Shanghai; data source: calculated by the authors.

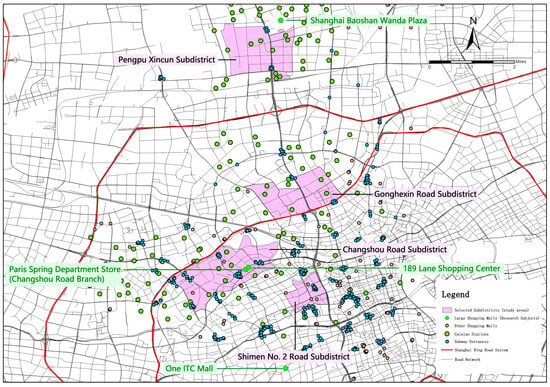

The four selected shopping malls capture Shanghai’s spatial and functional diversity across inner and outer rings, old and new urban forms, and varying levels of Cainiao exposure and metro access. Baoshan Wanda Plaza (988 Yierba Memorial Rd.) represents an outer-ring new-town mall with high Cainiao exposure and strong metro connectivity. 189 Lane Shopping Center (189 Changshou Rd., Putuo) is an inner-ring mall in an older mixed-use district with dense logistics presence and excellent metro access. Paris Spring Department Store (155 Changshou Rd., Putuo), which also has an inner-ring design and is currently under renovation, illustrates how traditional malls adapt to platform-driven consumption. One ITC Mall (1901 Huashan Rd., Xuhui) provides a contrast as an inner-ring, high-end center with low Cainiao exposure. Figure 2 illustrates the four selected neighborhoods and shopping malls, together with their associated Cainiao stations and related logistics infrastructure.

Figure 2.

Locations of the four sampled subdistricts and shopping malls in Shanghai, overlaid with Cainiao station points and metro entrances. The map illustrates spatial variation in last-mile logistics exposure across Shanghai’s ring road system (map produced by the authors).

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

Section 3.1 outlines the data sources; this section describes how those data were collected during fieldwork. Street-segment observations were conducted in a two-week campaign in 2025 following a standardized protocol. For each segment selected through the sampling strategy in Section 3.2, researchers carried out on-site verification of business status, documented commercial frontage conditions, and recorded parcel-related activities using geotagged photographs. Pedestrian flows were measured through two timed manual counts (weekday evening and weekend late morning), and the nearest Cainiao facility was confirmed on site, including distance and operational characteristics.

For shopping malls, data were collected through structured 45–60-min visits in both high- and low-exposure zones. Researchers followed a unified recording template to document unit occupancy, visible repurposing, logistics integration (e.g., pickup points, parcel lockers), and rider activity. Foot-traffic counts were conducted at main entrances during peak and off-peak periods. Brief interviews with tenants, customers, and mall staff supplemented observational data by providing contextual insights into leasing dynamics and the perceived effects of e-commerce logistics.

3.4. Data Analysis

The analysis proceeded through four stages—spatial analysis, statistical modelling, shopping-mall assessment, and planning document review—linking neighborhood-scale retail patterns with broader planning responses. First, ArcGIS 10.8 was used to geocode Cainiao stations, overlay them with subdistrict and street layers, and generate exposure indicators such as 300-m buffers, station density, and distance-to-station measures; street segments were spatially joined to the nearest facility. Second, street-level data (vacancy, retail mix, road class, accessibility, and neighborhood identifiers) were compiled for OLS regression in R to test whether logistics exposure predicts vacancy, with controls for metro and mall proximity, road hierarchy, and neighborhood fixed effects. VIFs and model-fit statistics guided specification. Third, shopping-mall analysis combined descriptive metrics—vacancy, tenant turnover, retail composition, footfall, and e-commerce activity—with coded interview and observation data to identify patterns of decline, repurposing, experiential consumption, and logistics integration. Fourth, Shanghai’s Master Plan 2017–2035 was evaluated using an eight-dimensional responsive-planning framework, coding plan provisions as present, partially present, implied, or absent. District and subdistrict plans for Jing’an and Putuo enabled cross-comparison of institutional adaptation and remaining gaps in responding to platform-driven land-use change.

4. Shanghai’s Platform E-Commerce Policies and the Development of Cainiao Stations

Shanghai—widely regarded as China’s premier global city—has long positioned itself at the forefront of cultivating new industries, stimulating the new economy, and shaping a competitive, innovation-friendly business environment. This trajectory has been extensively documented across a series of studies [55,56,57,58], each examining different phases of Shanghai’s institutional strategies, cultural–economic policies, and governance reforms that enabled its transformation into a national leader in creative industries, innovation-led development, and globally oriented urban competitiveness. Collectively, these works demonstrate that Shanghai’s long-standing policy orientation toward economic modernization provides essential context for understanding the rise of platformized e-commerce logistics in the city today.

Municipal policy has played a central enabling role in this process. The “Implementation Opinions on Promoting Coordinated Development of E-Commerce and Express Logistics” issued in 2019 articulate Shanghai’s strategic commitment to integrating e-commerce logistics into urban development [59]. The document highlights the need for coordinated planning of logistics facilities, the incorporation of express delivery infrastructure into statutory land-use systems, and the flexible adaptation of existing buildings for warehousing, distribution, and community-level service functions. It also formally recognizes parcel lockers, community depots, and service stations as essential public facilities and calls for embedding such infrastructures within neighborhood service networks.

Academic analyses show that these policies have accelerated a spatial restructuring of Shanghai’s logistics system. Logistics facilities have increasingly dispersed away from the urban core toward suburban and peri-urban areas, guided both by market forces—such as rising e-commerce demand and improved transport accessibility—and by planning interventions that support logistics industrial parks and transport–logistics corridors [60].

Within this broader institutional and spatial context, Cainiao, Alibaba’s logistics arm, has become a defining actor. Its dense portfolio of community-level service stations, smart parcel lockers, and micro-fulfillment nodes has woven a fine-grained logistics layer into residential compounds, commercial blocks, and neighborhood shopping centers. Cainiao’s rapid scaling reflects both Shanghai’s policy commitment to the digital economy and the city’s large, diversified consumer base, which together foster high-frequency parcel circulation and data-driven logistical coordination.

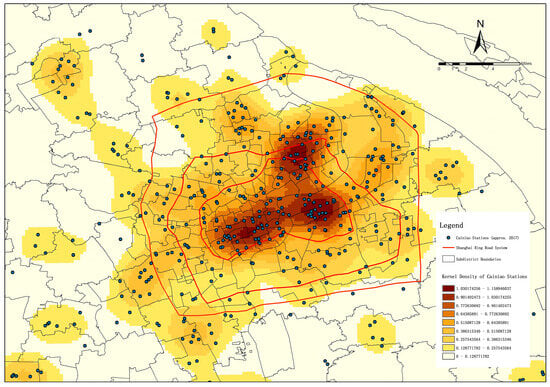

Cainiao Stations have experienced major spatial and organizational shifts in Shanghai, shaped by changes in China’s platformized e-commerce logistics. Around 2015–2017, Cainiao rapidly expanded by partnering with convenience-store chains such as FamilyMart and Nonggongshang. These stores handled parcel pickup and temporary storage, enabling dense coverage within the Inner Ring Road [61,62].

The 2017 map reflects this early model: station clusters were heavily concentrated in central districts where convenience stores were abundant (Figure 3). However, by 2017, many convenience stores began withdrawing from the partnership due to rising labor and rental costs, inadequate parcel-handling compensation, privacy concerns, and the overwhelming volume of e-commerce deliveries. Some imposed strict daily limits, while others exited entirely, prompting media descriptions of a “last-mile challenge” and forcing Cainiao to restructure its station network [61,62].

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution and kernel density of Cainiao stations in Shanghai (circa 2017). The map visualizes the early-stage pattern of station deployment, highlighting areas of emerging concentration (Mapped by the authors using data from the official Cainiao platform).

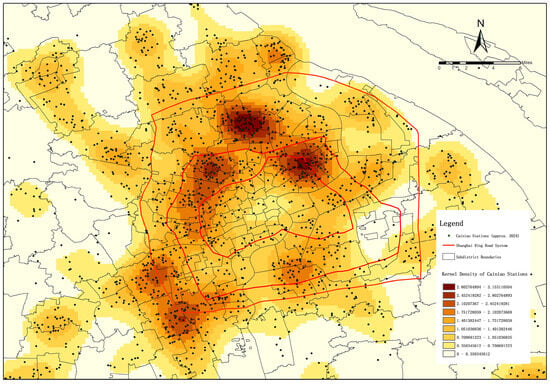

In response, Cainiao shifted toward independently operated “Cainiao Yizhan” outlets located within residential communities. This transition occurred amid escalating competition from JD, Hive Box, and other logistics platforms, as well as shrinking profit margins across the delivery sector. Station operators faced thin earnings—often needing to process 600–800 parcels per day to break even—while costs for rent, labor, and utilities continued to rise. Although Cainiao experimented with additional services such as community group-buying pickup and recycling, these efforts only partially offset operational pressures [63].

These industry dynamics produced a marked spatial reconfiguration. By 2024, Cainiao Stations had largely migrated outward, with new clusters concentrated beyond the Middle and Outer Ring Roads. The 2024 kernel-density map shows a thinning presence in the urban core and intensified clustering in suburban residential districts where rents are lower and population density supports high parcel volumes (Figure 4). This outward shift—from convenience-store-based urban stations to dedicated community logistics outlets—captures Cainiao’s strategic adaptation to changing partnership conditions, operational costs, and competitive pressures within China’s rapidly evolving last-mile delivery system.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution and kernel density of Cainiao stations in Shanghai (circa 2024). Compared with 2017, the map shows intensified station clustering and expanded coverage across the metropolitan region (Mapped by the authors using data from the official Cainiao platform).

5. Results

5.1. OLS Results

This section presents the empirical findings of the study (Figure 5 and Figure 6), analyzing how proximity to Cainiao’s last-mile logistics infrastructure influences street-level retail vacancy and neighborhood land-use dynamics in Shanghai.

Figure 5.

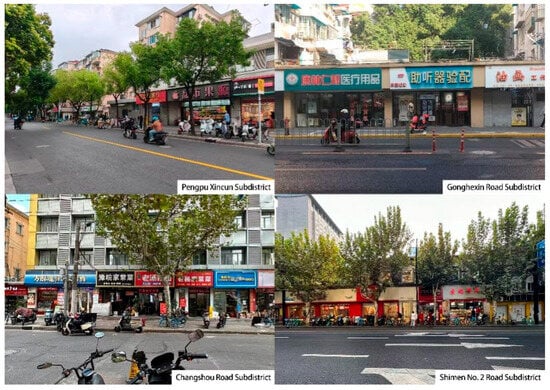

Street-front retail stores in the four selected subdistricts for study, photos by the authors.

Figure 6.

The four sampled shopping malls included in this study; photos by the authors.

Table 4 reports descriptive statistics for the street-segment dataset collected from the four selected subdistricts in Shanghai, summarizing key indicators related to retail vacancy, logistics proximity, and local built-environment conditions.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of collected street-segment data from four selected subdistricts in Shanghai. Data source: authors’ compilation.

The results are organized around two ordinary least squares (OLS) models—Model A (Table 5) and Model B (Table 6)—that test the hypothesized relationships between retail vitality and key spatial variables derived from the conceptual framework.

Table 5.

OLS Regression Results: Street-Level Retail Vacancy (Model A); produced by the authors.

Table 6.

OLS Regression Results: Street-Level Retail Vacancy (Model B).

Model A tests the relationship between street-level retail vacancy and proximity to Cainiao’s last-mile logistics facilities using the full set of station-age categories.

Model A achieves modest explanatory power (Adj. R2 = 0.089; F(12, 94) = 1.87; p = 0.048), suggesting that the included predictors jointly account for a limited but statistically meaningful share of variation in retail vitality. The most significant variables are station_age2 (3–4 years) (β = 0.177; p = 0.047) and distance_to_station (β = 2.57 × 10−4; p = 0.007), indicating that segments farther from logistics nodes—and those near stations established during the mid-development phase—tend to have higher vacancy rates. This pattern supports the idea that logistics proximity can enhance local retail performance, particularly once stations are mature enough to attract steady user flows.

Other predictors—including recent or older station age, metro and mall proximity, street hierarchy, and neighborhood fixed effects—show no significant effects. VIF values (≤7.3) indicate only moderate collinearity. Overall, Model A suggests a localized positive association between Cainiao facilities and retail vitality, aligning with the hypothesis that last-mile logistics nodes generate neighborhood-scale complementarities under platform urbanism, rather than uniformly substituting for traditional commerce.

Based on the VIF result (Table 7), we combined station_age2 and station_age3, and built an updated model: Model B.

Table 7.

The VIF results for Model A and Model B, produced by the authors.

We compared model fit with AIC/BIC and tested whether the two “age” coefficients can be collapsed using R.

An F-test (p = 0.29) indicated no significant difference between mid- and long-established stations, so these categories were merged into a single “mature station” variable to reduce multicollinearity while retaining explanatory power. Model B is therefore the more efficient specification: it remains theoretically meaningful, improves stability, and does not worsen model fit.

Model comparison shows only marginal gains in Model A, which distinguishes the two age groups (Adj. R2 = 0.089 vs. 0.074; AIC –82.4 vs. –81.5) (Table 8). The F-test confirms the categories are statistically indistinguishable, justifying consolidation in Model B. We therefore use Model B as the parsimonious specification while confirming that Model A yields consistent results.

Table 8.

Model comparison statistics for Model A and Model B, including AIC, BIC, R2, and adjusted R2 values.

Model B assesses retail vacancy after consolidating station ages. It shows modest explanatory power (Adj. R2 = 0.074; F(11,95) = 1.77; p = 0.07). Distance to the nearest Cainiao station is the only significant predictor (β = 2.49 × 10−4; p = 0.0097), indicating vacancy rises with increasing distance—suggesting localized agglomeration effects in which Cainiao stations help sustain nearby retail by generating pedestrian and consumer flows.

Other predictors—station age, metro and mall proximity, street hierarchy, and neighborhood fixed effects—are insignificant, implying that retail outcomes are shaped primarily by proximity to last-mile logistics infrastructure rather than broader accessibility. All VIFs remain below 4.4, confirming low multicollinearity.

The insignificant station_buffer_300 dummy and the significant distance_to_station coefficient reflect a continuous spatial relationship rather than a threshold effect. Retail vitality does not shift sharply at 300 m; instead, Cainiao’s influence decays gradually with distance. This aligns with spatial interaction theory, indicating that last-mile logistics exert diffuse, distance-sensitive impacts rather than discrete, boundary-based effects.

5.2. Shopping Mall Investigation Outcome

The assessment of four shopping malls—Baoshan Wanda Plaza, 189 Lane Shopping Center, Paris Spring Department Store, and One ITC Mall—reveals clear patterns of structural transformation under platformized e-commerce (Table 9 and Supplementary Material).

Table 9.

Characteristics of the four sampled shopping malls. The appendix summarizes scoring criteria and formulas used to calculate daily foot traffic and the Foot-Traffic Intensity Index (FII). Data source: authors’ fieldwork and calculations.

These results are generated through a standardized evaluation framework incorporating vacancy counts, five-year turnover estimates, tenant classification, public-space vitality scoring, 5:2 weighted foot-traffic counts (weekday/weekend), flow-intensity calculations adjusted for 1 km population catchments, and e-commerce participation indices. Together, the findings demonstrate a consistent pattern: platformized e-commerce does not produce large visible vacancies but instead drives a gradual reconfiguration of mall functions, commercial stability, and customer flows, with community-serving malls most affected and upmarket, experiential malls showing relative resilience.

5.3. Alignment of Shanghai Master Plan (2017–2035) with Platform-Era Spatial Transformations

Evaluation of Shanghai’s 2017–2035 Master Plan across the four subdistricts reveals a consistent pattern: although the plan strongly supports mixed-use, adaptive, and anticipatory development, it does not address the spatial impacts of platformized e-commerce and last-mile logistics (Table 10). All subdistricts—Pengpu Xincun, Gonghexin Road, Changshou Road, and Shimen No. 2 Road—promote mixed-use layouts, commercial optimization, and improved public-service land, aligning with the first dimension of the analytical framework.

Table 10.

Assessment of Shanghai’s Master Plan (2017–2035) across four sampled subdistricts; produced by the authors.

However, responsiveness to logistics- and platform-driven change is limited. Only Changshou Road shows partial alignment through its logistics and digital-industry designation; the other subdistricts lack flexible zoning or provisions for micro-warehousing, livestreaming, or hybrid commercial–logistics uses. The plan also omits digital indicators such as parcel flows and delivery frequency and makes no reference to parcel lockers, community depots, or last-mile corridors. Fieldwork shows these hybrid retail–logistics spaces are widespread, yet the plan offers no tools to manage them. Sustainability and governance sections similarly overlook the environmental and infrastructural impacts of digital logistics, with Changshou Road again the only area explicitly recognizing digital and logistics infrastructures.

Although Shanghai’s Master Plan serves as the empirical basis for evaluating planning responsiveness, the identified gaps—lack of recognition for micro-logistics infrastructures, absence of digital indicators, and insufficient zoning flexibility—are not unique to Shanghai. These issues reflect broader structural challenges facing Chinese cities as platformized e-commerce reshapes land-use patterns. The evaluation framework developed in this study thus provides a transferable tool for other municipalities seeking to integrate platform-era spatial dynamics into comprehensive planning.

6. Discussions

6.1. Response to Research Problems 1 & 2/Hypotheses 1 & 2

Hypothesis 1 proposed that proximity to Cainiao stations would correlate with higher retail vacancy. The regression results only partially support this, and the relationship emerges in the opposite direction. In both Model A and Model B, distance_to_station is positive and significant, indicating that vacancy increases as the distance from a Cainiao station increases. Street segments closer to stations therefore show lower vacancy, suggesting that Cainiao nodes may reinforce rather than weaken local retail vitality—a pattern consistent with field observations showing that parcel pickup and return activities generate steady pedestrian flows that spill over into nearby shops.

Descriptive statistics help clarify this gradient effect. Mean distance to the nearest Cainiao station is 493.94 m, ranging from 33 to 1372 m, indicating substantial spatial variation. This helps explain why station_buffer_300 is insignificant: retail responses are spread across a broad distance band rather than concentrated within a 300-m radius. The weak threshold effect reinforces the interpretation that platform impacts diffuse continuously through neighborhood space.

Vacancy patterns show similar heterogeneity. The mean vacancy rate is 0.22, with a large standard deviation (0.16) and a wide range (0–0.87), making it difficult for a single proximity measure to capture all variation in retail conditions. Even so, the consistent significance of the distance variable indicates that Cainiao proximity remains a meaningful predictor despite noise in the dependent variable.

Hypotheses 2a and 2b expected spatial variation in this relationship across inner vs. outer rings and across neighborhoods with differing station density. However, neighborhood fixed effects are insignificant in both models, and descriptive statistics for neighborhood dummies (neighborhood_a, b, c) show no strong mean differences and moderate variation without clustering. This suggests that the proximity–vacancy relationship is broadly consistent across the sampled areas. Platform logistics thus function as a citywide infrastructure whose land-use effects transcend traditional inner–outer ring divisions and localized station-density differences.

These findings point to a plausible causal mechanism underlying the observed relationship between logistics proximity and retail vitality. Cainiao stations generate repeated micro-flows of pedestrian activity through routine parcel pickup and return, creating small but steady streams of movement that sustain convenience-oriented street retail. This mechanism helps explain why vacancy increases with distance and why proximity continues to matter across broad spatial bands. At the same time, the insignificance of other spatial variables—including metro access, mall proximity, street hierarchy, and neighborhood categories—aligns with Hesse’s [32] argument that contemporary logistics urbanism is driven less by physical transport infrastructures and more by the circulation of commodities across extended urban networks. Under platformized e-commerce, the influence of logistics is diffused through consumption flows rather than concentrated in fixed infrastructures, meaning that it is the pervasive reach of digital–logistical circulation—not the physical attributes of streets, districts, or transport systems—that shapes neighborhood retail outcomes. In this sense, the citywide penetration of platform logistics renders many conventional predictors less relevant, while distance to the nearest logistics node remains the strongest spatial signal of retail performance.

6.2. Response to Research Problem 3/Hypothesis 3

Hypothesis 3 posits that the expansion of platformized e-commerce logistics undermines shopping-mall vitality through rising tenant turnover, functional restructuring, and reduced foot traffic. Evidence from the four studied malls generally supports this claim, though outcomes differ depending on mall positioning and tenant adaptability.

Although formal vacancy rates remain low (0–14.44%), all malls exhibit a clear “silent decline.” Five-year tenant turnover is exceptionally high—63% at Wanda, 96.72% at 189 Lane, 97.78% at Paris Spring, and 87.23% at One ITC—indicating sustained instability. Interviewees echoed this pattern: a Wanda receptionist noted “constant turnover,” while a Paris Spring boutique reported increasingly unstable sales that were “getting worse year by year.” Tenants across malls described fluctuating customer flows and rising uncertainty.

This instability is accompanied by substantial functional restructuring. Retail has become a minority land use in the three community malls: 9.43% at 189 Lane, 24.68% at Paris Spring, and 30.43% at Wanda. Dining, tutoring, leisure, beauty, and gym uses now dominate. Field observations recorded former fashion units converted into classrooms and activity rooms and consistently weak boutique patronage. Tenants often attributed this to online substitution; customers likewise reported visiting mainly for dining, leisure, or parcel pickup rather than shopping.

Foot-traffic intensity is similarly weak. Entrance and escalator counts show low to medium-low flows, with public spaces underused even during peak hours. Staff at 189 Lane described foot traffic as “very low lately,” and long-time employees noted clear declines compared with earlier months. The rise of pickup and delivery further reduces browsing: Wanda staff observed sharply increased in-store pickup, while a fast-food shop at 189 Lane reported only 10 dine-in versus 20–30 delivery orders per day.

Patterns across the four malls show that platformized e-commerce pressures all malls to some extent, but their responses differ according to positioning and tenant mix. One ITC Mall, despite being located in an area with few nearby Cainiao stations, is not insulated from platform substitution: it also exhibits a high rate of tenant turnover, and many retailers report declining sales due to online competition. Yet the mall maintains strong overall vibrancy because visitors are drawn not primarily for shopping but for the experiential qualities it offers—premium brands, aesthetic interior design, cafés, and social spaces that create a destination environment. In contrast, Paris Spring’s weak foot traffic is further depressed by renovation activities, while Wanda and 189 Lane—serving community-oriented markets—experience more visible erosion of traditional retail as platform logistics outperform them in price, convenience, and product diversity. These contrasting cases demonstrate that while platform e-commerce imposes pressures across all mall types, experiential malls retain relative resilience by offering functions that digital platforms cannot easily substitute.

6.3. Response to Research Problem 4/Hypothesis 4

Hypothesis 4 suggests that Chinese urban planning has not yet adapted to the hybrid land-use forms and decentralized spatial patterns generated by platformized e-commerce logistics. The planning evaluation supports this claim. Although Shanghai’s Master Plan (2017–2035) emphasizes mixed-use development, public-service improvement, and overall urban vitality, it remains largely disconnected from the spatial transformations driven by last-mile logistics, parcel lockers, and platform-mediated consumption.

First, all four subdistricts—Pengpu Xincun, Gonghexin Road, Changshou Road, and Shimen No. 2 Road—align with general principles of mixed-use and anticipatory planning, but this reflects continuity with traditional planning rather than a response to platform-induced change. The plan promotes commercial–residential integration and jobs–housing balance, yet does not acknowledge the hybrid commercial–logistics environments now common along retail streets and within community compounds. Fieldwork confirms that parcel stations and delivery nodes are deeply embedded in everyday spaces, but these facilities remain absent from formal planning instruments.

Second, only Changshou Road shows partial recognition of logistics-oriented development through its smart-logistics designation. Elsewhere, the plan lacks mechanisms—flexible zoning, adaptive reuse, overlay districts—to accommodate micro-warehousing, parcel pickup, self-collection points, or livestreaming studios. These omissions highlight the gap between the spatial demands of platform and logistics urbanism and a regulatory framework that still treats commerce, logistics, and residential uses as separate categories.

Third, the evaluation shows no integration of digital-economy indicators or micro-logistics infrastructures into planning. Metrics such as parcel flows, delivery frequency, or platform-generated mobility are not used, nor are parcel lockers, depots, or delivery nodes recognized as facilities requiring planned locations, design standards, or environmental management. Consequently, logistics functions proliferate informally in street edges, lobbies, and leftover spaces without oversight.

Finally, last-mile transport is not incorporated. Although the plan provides guidance on metro expansion and road hierarchy, it omits courier e-bikes, delivery corridors, or neighborhood-level freight circulation, indicating a continued focus on passenger mobility rather than emerging logistics flows.

Taken together, these findings show that Shanghai’s planning system has not yet adjusted to the hybridized, decentralized, and data-driven spatial patterns produced by platformized e-commerce. The deepening integration of platform and logistics urbanism requires more responsive tools—flexible zoning, performance-based regulation of hybrid spaces, formal recognition of micro-logistics facilities, and the use of digital indicators in neighborhood-scale planning. These results confirm Hypothesis 4 and underscore the need for planning frameworks to evolve alongside platform-mediated urban spatial logics.

7. Conclusions

This study advances empirical and theoretical understanding of how platformized e-commerce logistics reshape urban land use at the neighborhood scale. The paper demonstrates that platform logistics transform urban space through two intertwined mechanisms: localized complementarity, whereby physical service nodes generate pedestrian flows that sustain neighborhood retail, and citywide logistical substitution, whereby digitally coordinated delivery systems restructure and repurpose community-oriented shopping malls.

First, Cainiao stations function as physical service nodes that attract steady pedestrian flows for parcel pickup and returns. These localized micro-flows generate complementary commercial activity in their immediate surroundings: retail vacancy declines as distance to a station decreases, revealing that last-mile nodes create new everyday foot-traffic ecologies. The spatial relationship between logistics proximity and retail vitality is therefore broad, continuous, and citywide rather than confined to narrow radii or specific urban zones.

Second, Cainiao stations operate as neighborhood-level execution points within a digitally coordinated logistics system. Upstream algorithms determine parcel routing and flow, while stations simply materialize these digital processes on the ground, making platform logistics visible in everyday urban space. This circulation system permeates all neighborhood types, regardless of location, age, or transit access. Its effects are most pronounced in community-oriented shopping malls, where platform logistics exert a restructuring—rather than complementary—force. Malls face direct substitution pressure for standardized goods, accelerating tenant turnover and pushing them away from traditional retail functions. Their core value proposition—product variety, brand verification, and on-site browsing—is precisely what platformized e-commerce replaces most efficiently, rendering such malls structurally vulnerable.

Together, these dynamics flatten the previous hierarchy of commercial spaces. Instead of a tiered retail landscape ranging from local shops to mid-range malls, platformization produces a bifurcated system: (1) neighborhood retail streets sustained by logistics-driven everyday flows and (2) a new class of malls that survive not through retailing but through experiential, leisure, and service-oriented functions. Community malls increasingly reposition themselves as multifunctional community-care or lifestyle centers, while high-end malls rely on unique spatial design attributes and immersive place qualities that cannot be replicated by digital platforms.

At the same time, the assessment of Shanghai’s Master Plan (2017–2035) shows that current planning instruments have yet to fully engage with these spatial transformations. Despite strong commitments to mixed-use development and urban vitality, the plan remains largely disconnected from last-mile delivery flows, parcel-locker networks, data-driven consumption patterns, and the emergence of hybrid commercial–logistics spaces. This disconnect underscores the need for platform-responsive planning capable of addressing the new land-use configurations produced by digital logistics systems. Theoretically, this paper advances platform and logistics urbanism by reconceptualizing last-mile e-commerce infrastructure as a dual-role urban system. Building on Zhang’s [8] cyber–physical view of logistics and Zhang et al.’s [29] account of commercial restructuring, the study shows that platform logistics produces differentiated land-use effects across spatial scales. At the neighborhood retail scale, logistics proximity generates diffuse, complementary effects that sustain street-level commerce, while at the shopping-mall scale—especially in community malls—it accelerates displacement, tenant turnover, and functional repurposing. This reveals that platformization does not merely flatten commercial hierarchies but reclassifies urban commercial space into product-oriented retail vulnerable to substitution and experience-oriented places that depend on design, leisure, and social functions. Together, these findings extend existing theory by specifying how digital coordination translates into scale-dependent spatial outcomes in platformized cities. Methodologically, existing studies of e-commerce and land use have largely relied on macro-scale panel or spatial analyses at the provincial, municipal, or county level, or on descriptive mappings of logistics facilities. This study instead adopts a micro-scale design centered on street segments and individual shopping malls. By integrating field-observed vacancy rates with GIS-based proximity measures, neighborhood fixed-effects models, and mall-level case studies combining quantitative vitality indicators with qualitative observations, it directly links last-mile logistics exposure to neighborhood-scale land-use outcomes. This mixed-method approach bridges macro-level platform analyses with the fine-grained spatial transformations unfolding in everyday urban space.

Empirically, the evaluation of Shanghai’s 2017–2035 Master Plan reveals a clear governance mismatch between rapid platform-logistics expansion and existing planning frameworks. While the plan promotes mixed-use redevelopment and technological upgrading, it lacks tools to manage hybrid commercial–logistics spaces, integrate last-mile delivery into transport planning, accommodate micro-logistics infrastructure, or incorporate digital-economy indicators into spatial monitoring. By operationalizing a planning-evaluation framework grounded in platform and logistics urbanism, this study offers a practical method for diagnosing these gaps and guiding more adaptive, flexible, and data-informed planning responses to platform-driven spatial restructuring in Chinese cities and beyond.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15010004/s1, Notes for Table 9.

Author Contributions

J.Z.: conceptualization, theorization, research design, writing, revision, validation, resource, project supervision, funding; Y.Z.: investigation, project supervision, validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shanghai University under Grant No. J.07-0113-25-201. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was also funded by Shanghai University under the same grant.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were compiled by the authors through field surveys, spatial mapping, and the integration of publicly available planning documents and point-of-interest (POI) information. Due to privacy considerations and the contextual nature of neighborhood-level observations, the full dataset is not publicly available. Aggregated data and methodological details supporting the findings of this study are included within the article. Additional information may be provided by the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Zhao Yongchen for assistance with data scraping from the Cainiao website. We also thank Liu Hanqi and Cheng Zhuling, undergraduate students in the School of Fine Arts at Shanghai University, each of whom conducted field data collection in one of the study neighborhoods.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. The rise of the platform economy. Issues Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. The platform economy: Restructuring the space of capitalist accumulation. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2020, 13, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, P.; Leyshon, A. Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalisation of digital economic circulation. Finance Soc. 2017, 3, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnicek, N. Platform Capitalism; Wiley: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Plantin, J.-C.; Lagoze, C.; Edwards, P.N.; Sandvig, C. Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y. Platform ruralism: Digital platforms and the techno-spatial fix. Geoforum 2022, 131, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Investigation of e-commerce in China in a geographical perspective. Growth Change 2019, 50, 1062–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Ullah, N.; Grigoryan, S.; Hu, Y.; Song, Y. Variations in the spatial distribution of smart parcel lockers in Tianjin before and after COVID-19. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Q. The impact of farmers’ e-commerce adoption on land transfer. Land 2024, 13, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, X.; Li, Y. Effect of e-commerce popularization on farmland abandonment: Evidence from China. Land 2023, 12, 1014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Li, M.; Cao, X. Empowering rural development: Evidence from China on the impact of digital village construction on farmland scale operation. Land 2024, 13, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Lü, H.; Wang, Z. Enhancing environmental sustainability in transferred farmlands through rural e-commerce: Insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 25388–25405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portwood, P. Assessing the Flexibility of Commercial Land Use in Eugene, Oregon: Planning for E-Commerce. Master’s Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, A.H.; Hassan, G.F.; Abd Elrahman, A.S. Impacts of e-commerce on planning and designing commercial activities centers: A developed approach. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Aldosary, A.S.; Mohammed, I. E-commerce induced shifts in urban spatial structure. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2019, 145, 04019006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, H. Spatial structure of China’s e-commerce logistics network. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Express Delivery Market|2019–2030 (CEDM). Available online: https://www.kenresearch.com/china-express-delivery-market (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Leszczynski, A. Glitchy vignettes of platform urbanism. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2020, 38, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. Data Lives: How Data Are Made and Shape Our World; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, E.-J.; Lanzendorf, M. Mobility and accessibility effects of B2C e-commerce: A literature review. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2024, 95, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.A. Platform logic: An interdisciplinary approach to the platform-based economy. Policy Internet 2017, 9, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, J. Cyberspace and cityscapes: On the emergence of platform urbanism. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barns, S. Platform Urbanism: Negotiating Platform Ecosystems in Connected Cities; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lyster, C. Learning from Logistics: How Networks Change Our Cities; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin, L.; Vieira, J.G.V.; de Oliveira, R.L.M.; de Oliveira, L.K.; de Miranda Vieira, H.E.; Dablanc, L. The geography of warehouses in São Paulo. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, Y.; Sun, X. Logistics space reorganization under e-commerce. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100300. [Google Scholar]

- Harun, I.; Yigitcanlar, T. Urban land use and value in the digital economy: A scoping review of disrupted activities, behaviours, and mobility. Land 2025, 14, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, P.; Ye, Y. The effects of e-commerce on the demand for commercial real estate. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amling, A.; Daugherty, P.J. Logistics and distribution innovation in China. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2020, 50, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysen, N.; Fedtke, S.; Schwerdfeger, S. Last-mile delivery concepts: A survey from an operational research perspective. OR Spectr. 2021, 43, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, M. Cities and flows: Re-asserting a fundamental relationship. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 29, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danyluk, M. Supply-chain urbanism: Constructing and contesting the logistics city. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2021, 111, 2149–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, C.; Danyluk, M.; Cowen, D.; Khalili, L. Turbulent circulation: Building a critical engagement with logistics. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2018, 36, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, D. The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Sun, S. Examining influencing factors of express delivery stations’ spatial distribution using the gradient boosting decision trees: A case study of Nanjing, China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, M.; Sanyal, R. Platform economies and urban planning: Airbnb and regulated deregulation in London. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3353–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L. Spatialization of digital platforms. Soc. Media Soc. 2025, 11, 20563051251320696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, T.; Farid, R. Exploring the impacts of e-commerce on urban planning. Cities 2019, 95, 102379. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Baoshan District (Central City Sector). 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20231013/a07e313f6fe6496eb248ba8ef97697da.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for the Southern Sector of Minhang Main City Area. 2023. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/67d91ed9b8274b15a80831d1277c5b05.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for the Central Sector of Minhang Main City Area. 2023. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/1717ce2fe02b4af6ba3b5faa9cdbce2a.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Songbao Unit Plan (Baoshan Sector of Shanghai’s Main City Area). 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20231013/73f11a45a0e7451199b0b504b750967b.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Huangpu District, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/775f4583263746beb5c148d158edb751.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Jing’an District, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/1e90cef7e5eb474da6caeb82c36a72c5.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Xuhui District, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/bdb498c0269749a1876670596eedb809.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Changning District, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/3d50b03329a64a1285d734319a6cc16d.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Putuo District, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/8f95099c59344e31a18d7e95d369270c.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Hongkou District, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/74446e054a704c5182d20d43bb9b5167.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Yangpu District, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/9e36951eb8c74e8d96c406bd3e670694.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Lujiazui–Expo Unit Plan of Pudong New Area, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/945b76c0c19d42b2a8b167d75a8f7c34.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Zhangjiang Unit Plan of Pudong New Area, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/bc7c72311d5a45cfaa6365fd374a3ce5.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Jinqiao–Waigaoqiao Unit Plan of Pudong New Area, Shanghai. 2022. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/a2f2987c01504d6d8b6f1af312551fa0.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Unit Plan for Hongqiao Main City Area, Shanghai. 2020. Available online: https://ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcdygh/20230925/fd9d033178624818af84e10d770febae.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Zheng, J. The “entrepreneurial state” in “creative industry cluster” development in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. “Creative industry clusters” and the “entrepreneurial city” of Shanghai. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 3561–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. Contextualizing public art production in China: The urban sculpture planning system in Shanghai. Geoforum 2017, 82, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chan, R. The impact of “creative industry clusters” on cultural and creative industry development in Shanghai. City Cult. Soc. 2014, 5, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]