Abstract

Urban agriculture’s potential for food production and other social benefits is widely documented. However, the diversity of organisational structures and contextual factors that shape and drive the practice leads to a range of productivity levels. Yet, most studies estimate productivity using average production data, which compromises the reliability of the estimates. The objective of the study presented here is to develop a GIS-based spatial analytical framework that takes into account varying levels of productivity for four urban food garden types: Home, Community, Educational, and Commercial. We apply this analytical framework in Bogotá, Colombia, a city at the forefront of policies promoting urban agriculture, where we collected data from a sample of urban food gardens (i.e., produce yield, resource use, and social benefits). To increase the precision and reliability of the estimates, we perform a spatial Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis through several ArcGIS pro 3.1 functions. This allows the identification of suitable areas for each urban agriculture type, based on key spatial and social characteristics (location, proximity to roads and to rivers, private or public land, urban density, and socio-economic demographic conditions). Results suggest that 25% of Bogotá’s surface area (including vacant urban land and roofs) presents potential physical and social conditions for food growing, within which Home Gardens occupy the largest share of suitable land. This shows that land availability is not a key limiting factor to a possible expansion of urban agriculture, particularly at a household level. Resource consumption and educational benefits are also estimated, hence providing a comprehensive picture of the impact of urban food production at a city scale.

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, the change in the perception of urban agriculture from a food production activity to a form of socio-economic and environmental resilience has attracted interest at a local policy level. Increasingly recognised as a nature-based solution, urban agriculture offers a range of co-benefits including climate change mitigation and adaptation, food security, biodiversity, social interaction, and mental wellbeing [1,2,3].

This growing interest is reflected in international policy frameworks such as the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact [4], an international agreement involving more than 280 cities, which promotes urban agriculture as a key element to achieve equitable, sustainable, and resilient local food systems. Furthermore, urban agriculture is increasingly recognised for its positive contributions to public health. For instance, the National Health Service (NHS) England has endorsed nature-based approaches such as community gardening under Green Social Prescribing because of its therapeutic benefits for mental health [5]. As a result, cities are increasingly experimenting with integrated strategies that embed urban and peri-urban agriculture into broader planning and governance frameworks. The growing recognition given to urban agriculture goes hand in hand with an increase in the number of academic studies to quantify its impacts. However, existing analyses have often failed to address the full range of socio-ecological variables that influence its effectiveness.

Across the Global South, particularly in Latin America, urban agriculture often plays a crucial role in local food production and serves as an important supplement to household food supply [6]. In cities like Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, urban development is shaped both by top-down planning and informal and self-developed initiatives [7]. This top-down approach often overlooks cross-boundary dynamics, while also being characterised by widespread socio-economic inequality, spatial segregation, unequal urban environments, and a high degree of informal economic activities [8]. These spatial and economic conditions not only affect access to urban services and mobility, but they also influence the development of urban agriculture, which often emerges in response to limited livelihood opportunities, unequal access to land, and the need for food security and opportunities among lower-income populations in informally developed neighbourhoods [9].

Recent studies have addressed urban and peri-urban agriculture in Colombia and Bogotá. Feola et al. [10] explore peri-urban farming and gardening households of Sogamoso, a neighbouring city of Bogotá, through a survey. They conclude that these activities support local food security and community wellbeing, even though they are informal and often overlooked by planners. Similarly, Riaño-Herrera [11] examined the role of small-scale urban agriculture in supporting sustainable urban development in Bogotá, using a rooftop greenhouse as a case study. The author reported that these spaces can achieve high yields and can provide food independence for thousands of families. In a field study investigating plant diversity in domestic gardens across seven neighbourhoods in Bogotá, Sierra-Guerrero [12] reported that these play an important role in conserving plant diversity, and that families in lower-income localities commonly cultivate edible plants for food and medicinal purposes. Nevertheless, these studies are primarily based on localised surveys and do not adequately map the geographic extent, suitability, or impact potential required to support policy action and collaborative interventions. To date, a methodological approach to evaluate the multiple impacts of urban agriculture, which is sensitive to the complex urban morphological, social characteristics, and diverse practices, has not been developed.

Several studies have highlighted the need for methodological approaches that can address the multiple scales and dimensions of urban agriculture, particularly through spatially explicit methods [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are increasingly gaining importance as an essential tool for analysing qualitative and quantitative data at different scales [24,25]. GIS-based studies facilitate the development and comparison of impact scenarios, thereby enhancing an understanding of land use dynamics [26,27,28,29,30].

The main aim of this study is to develop a GIS-based analytical framework to map and assess the potential distribution of urban agriculture. The analytical framework is designed to identify the influence of morphological and social characteristics on the expansion of urban agriculture, and factor in varying productivity levels connected to each type of urban agriculture. To test its effectiveness and ascertain its limitations, we apply it to the city of Bogotá.

The analytical framework combines spatial regression techniques, ecological niche modelling, and fieldwork data to attain the objectives of (1) identifying local key drivers of urban agriculture distribution, (2) mapping the spatial distribution of urban food gardens (i.e., gardens and farms where edible crops are cultivated) based on their characteristics, productivity levels, and socio-economic contexts, and (3) generating a spatially explicit suitability index to estimate food production capacity. The integration of these data sources and methods allows for a comprehensive assessment of the environmental, social, and economic drivers of urban food production. It offers a robust scientific foundation to support informed urban planning and the development of sustainable food systems.

2. Methods

2.1. Profile of the Case Study on Bogotà

Latin America is the region with the fastest urbanisation rates on the planet, with 81% of its population living in cities [31]. The Pan American Health Organisation predicted in 2012 that Bogotá would be one of the six Latin American municipalities to be among the 30 largest cities in the world [32]; currently housing over 8 million people [33].

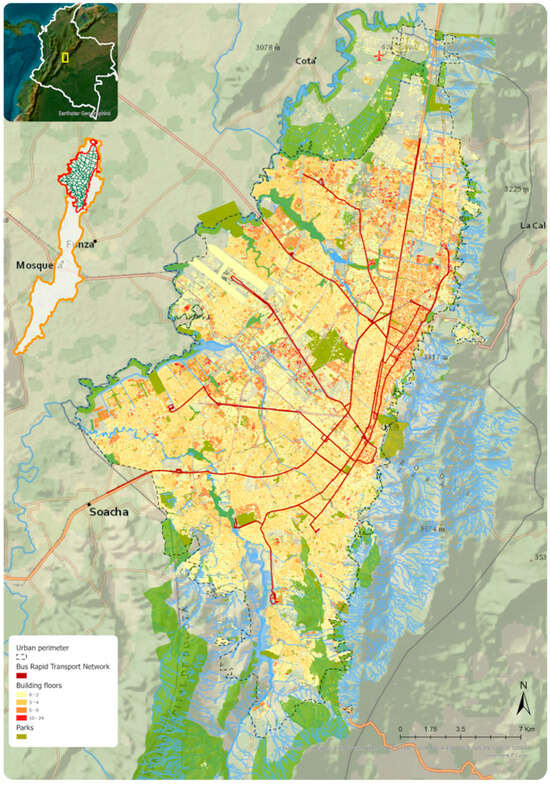

Bogotá (Figure 1) is located at 4.7110° N, 74.0721° W and an altitude of 2582 m.a.s.l. in the highland known as “La Sabana de Bogotá”. It is characterised by a cold and humid climate and is located within the intertropical zone of America [34]. This area is part of the Andean–Atlantic subsystem, with yearly precipitation of 797 mm [35] depending on the humid air masses from the Orinoco and Amazon regions. Its average annual temperature is 12.9 °C, ranging from 9.4 °C (min) to 18.3 °C (max) [36]. The southern area of the city is characterised by the presence of the Páramos, a type of high-Andean moorland that provides vital ecosystem services to the whole region, through water storage and collection of organic matter [37].

Figure 1.

Map of the city of Bogotá with main public transport routes, building height per block, green areas (including public parks and environmental infrastructure), and topography. The metropolitan area of Bogotá comprises 20 districts, while its urban core is composed of 112 Zonal Planning Units (see UPZ 3.2). Source: Elaborated by the main author using maps available on the open access portal IDEAC—https://www.ideca.gov.co/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

The city is organised in 20 administrative districts called Localidades covering an area of 1635 km2 (capital city area), which has been classified as 23% urban, 2% allocated for urban expansion, and 75% rural [38]. Bogotá houses roughly 16% [39] of the total inhabitants of Colombia (51,874,024 in 2022 [40]). Its population is expected to grow by 160,000 people per year [41]. Bogotá has recently attracted international interest for its cutting-edge policies for sustainable development [42]. Since 2004, the municipality has been steadily implementing programmes promoting urban agriculture [9]. Urban food gardens in Bogotá come in various forms, from raised beds on rooftops in the city centre to farms on the urban fringe, from fenced open-air classrooms to informal Community Gardens in public parks and riverbanks. Bogotá’s diverse population seems to be at the root of a varied interpretation of urban agriculture that goes beyond tackling food insecurity only [43]. In fact, it is also practiced for cultural and social reasons, including rural backgrounds, recreation, and political activism [9].

During the 20th century, a large share of the Colombian population migrated to the countryside and towards cities, either attracted by a flourishing urban economy or to escape the armed conflict devastating the rural areas [44,45]. In the last 60 years, Bogotá has been constantly battling with resource scarcity [40], with food insecurity affecting 24% of its households [32,39]. A World Bank report [46] suggests that as many as 8500 households within the city produced food for home consumption that could have cost between 2 and 5 dollars per day [43].

The municipality has acknowledged the positive impacts of urban agriculture and, in 2004, included this practice in Bogotá sin hambre, a programme that tackled the population’s undernourishment through a combined approach consisting of initiatives fostering economic development and social safety networks [47,48]. Within this programme, the Botanical Garden José Celestino Mutis coordinated Agricultura Urbana: Sostenibilidad ambiental sin indiferencia para Bogotá, a project with a range of educational/training initiatives to support new urban food gardens and existing networks of urban farmers [9]. The project was a success and was extended by the following administrations with the programmes: Bogotá bien alimentada and Bogotá te nutre [9,49]. As the municipal institution in charge of the urban agriculture programme [49], the Bogotá Botanical Garden monitors more than 20,000 people who work or volunteer in approximately 4000 urban food gardens [50].

The municipality has undertaken several initiatives to survey its urban food gardens, such as the online portal Bogotá es mi huerta [51] and a census carried out by the Bogotá Botanical Garden. However, to date, there are no studies that quantify the total productivity of urban food gardens in the Colombian capital. The Bogotá Botanical Garden has been supporting urban food gardens with workshops, equipment, and initiatives to connect farmers across the city. After each visit to a garden requesting assistance, the botanical garden officers annotate its location. A GIS shapefile reporting the location of 2555 urban gardens was published online in 2022. This database is a unique and invaluable resource that can be used to identify patterns of distribution across diverse neighbourhoods and more. However, the database only contains information on gardens requesting to register, hence not all existing gardens are included. Also, considering the informal and temporary character of many of these food gardens, especially in informal areas, this database would need to be regularly updated. Nevertheless, existing maps can be used to identify the social, physical, and environmental conditions necessary to start an urban food garden and use these to produce an estimate of their productivity and resource use.

2.2. Analytical Framework Outline

The analytical framework developed and applied to produce this estimate includes: (1) an analysis of existing maps to identify conditions enabling urban food gardens (i.e., drivers), leading to the development of a map of urban areas meeting such conditions; (2) definition of a typology of urban food gardens and an identification of physical and environmental characteristics associated with each type. This is followed by primary data collection on productivity and resource use from a sample of 15 urban food gardens that includes all types; and (3) suitability analysis within the areas determined in (1), which includes a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis and a Presence Suitability Index, leading to a final estimate of productivity. Data used to apply the framework and evaluate the potential for urban agriculture include: (a) datasets available on the online portal of the municipality of Bogotá, together with the urban food garden census dataset compiled by the Bogotá Botanical Garden; and (b) data collected from 15 case studies between February and May 2022.

2.3. Spatial Data Acquisition and Selection

All the shapefiles containing relevant information on the city of Bogotá and used for the GIS analysis were retrieved from the city’s two open-access official directories, Ideca [52] and Datos Abiertos [53], and from other online archives. The two directories contain, respectively, 393 and 509 maps that can be freely consulted and downloaded in GIS-compatible formats. The two directories were searched for maps containing information on urban agriculture and social, economic, environmental, and morphological urban features that could be connected to its presence.

A total of 81 maps from the two directories were examined and classified as social, environmental, economic, and spatial data (a list of maps can be found in the Supplementary Material to this article). Of these, 71 maps were deemed eligible for the study, as they mapped various urban features that could be linked to the presence of urban food gardens. An additional 20 maps were selected based on information gathered through bibliographic research and on-field observations. Finally, all shapefiles used in the analysis were checked for coordinate compatibility and unified to the WGS84 geographic coordinate system in ArcGIS.

To ascertain whether the distribution of urban gardens in Bogotá followed a pattern determined by specific factors, the map displaying the distribution of 2555 urban gardens in Bogotá provided by the Bogotá Botanical Garden was tested for autocorrelation. First, the geo-location of urban food gardens as displayed in the Bogotá Botanical Garden census was counted in three sets of polygons, describing different spatial subdivisions: the UPZ (the Unidades de Planeamento Zonal, the zonal planning units), the neighbourhoods, and a hexagonal grid with one square kilometre area tiles. Second, the spatial autocorrelation tool (Global Moran’s I) was run for the datasets reporting the number of gardens contained in the three sets of polygons, and for each of them, returned a clustered pattern. In all three cases, the z-score value indicated that there was less than a 1% likelihood that the clustering of gardens was causal (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Global Moran’s I analysis to determine the probability that the gardens’ clustered pattern is causal.

The Optimised Outlier Analysis tool in ArcGIS Pro 3.1 was employed to identify grid cells within the concentration (or dispersion) clusters with an incident count value that deviated from their surroundings. The maps obtained showed the areas with the highest (or lowest) concentrations of urban food gardens, and how urban agriculture varied within these clusters.

To identify the factors influencing the presence of urban food gardens in Bogotá, two methods of spatial regression were applied: Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR). The OLS method showed insufficient confidence levels, possibly due to the non-linearity of the correlation between drivers and the presence of food gardens, and to the fact that some of the data were non-parametric. The GWR tool was run using several combinations of the 20 maps selected during the initial phase of the analytical framework, with seven of them showing strong correlations with the urban food gardens’ presence (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the seven maps that showed strong correlation with and current location of urban food gardens.

The 7 maps identified as “drivers” for urban agriculture and the map locating 2555 urban food gardens in Bogotá were processed through the MaxEnt tool. This ArcGIS pro 3.1 function allows for mapping a phenomenon in its entirety by modelling the spatial correlation between a set of occurrence points and their explanatory variables.

The 7 maps were converted into raster format and employed to train the prediction algorithm of the MaxEnt tool and plot the presence of urban food gardens across Bogotá. To configure the MaxEnt model, the linear, quadratic, and product feature classes were selected to capture both additive and interactive effects among spatial predictors. The raster resolution was set to 25 × 25 m, and the urban perimeter of Bogotá defined the spatial extent of the analysis. The model was trained using the georeferenced locations of 2555 urban gardens and the seven explanatory layers identified through Geographically Weighted Regression. These layers were converted into raster format using either the Feature to Raster or Distance Accumulation tools, depending on whether the input data represented continuous or discrete spatial features. Model reliability was assessed through spatial autocorrelation diagnostics (Global Moran’s I), which confirmed a statistically significant clustered distribution of urban gardens across multiple spatial subdivisions. Additionally, visual inspection of the resulting probability map revealed coherent spatial patterns consistent with observed garden distributions, particularly in areas characterised by low social stratum index, informal settlements, and proximity to natural elements.

A map displaying the probability of the presence of urban food gardens throughout the city was generated. The map classified all the raster cells within the urban area on a scale from zero (no likelihood of presence) to one (strong likelihood of presence). Close cells with similar presence values produced visually recognisable patterns of distribution.

2.4. Typology of Food Gardens and Primary Data Collection

To accurately estimate the total productivity of urban agriculture in Bogotá, it was necessary to develop a typology of food gardens, as these have diverse agendas, which influence their consumption and productivity patterns [54]. Based on the main author’s observation during fieldwork as well as consultation with experts, a classification originally developed by the Bogotá Botanical Garden was revised. In particular, institutional gardens were merged with Educational Gardens because of their scarce presence and strict similarities with the latter (both designed to provide educational activities to students). A new type was created (Commercial Gardens), representing food gardens that commercialise their produce. The final typology included 4 types (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the 4 urban garden types and spatial characteristics associated such as location and proximity to roads. The footprint range is based on the surface area of the 15 case studies. Characteristics were functional to the identification of maps that were used for the MCDA.

Overall, 30 urban food gardens were initially contacted, with 22 identified from the Bogotá Botanical Garden database and 8 contacted through snowballing. A total of 15 food gardens representing the 4 types agreed to participate in the data collection, which took place between January and May 2022. Figure 2 shows an image of a food garden for each type.

Figure 2.

Photographs showing 4 case studies, one for each type of urban food gardens. Source: photographs of the main author.

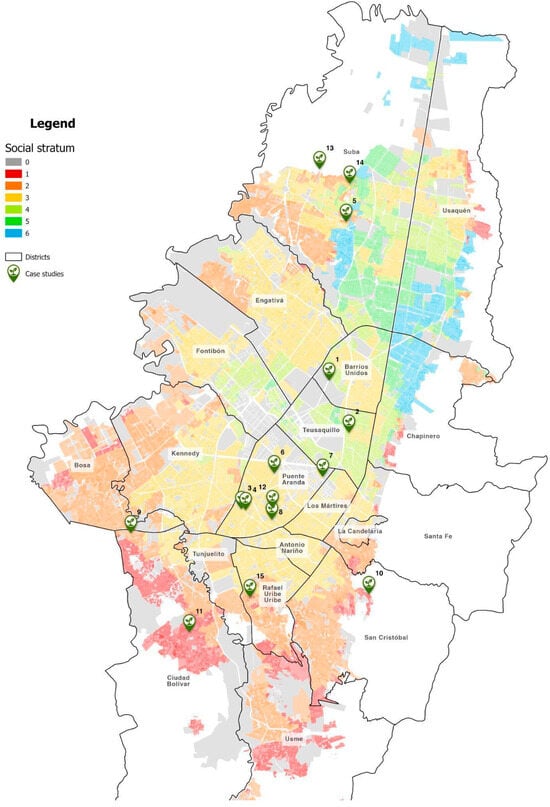

During the fieldwork, each case study was surveyed to identify physical characteristics (e.g., surface area), the profile of its gardeners, and the main objectives. Each case study was asked to record in a diary inputs (water, labour, compost, and fertiliser) and outputs (crops, crop variety, and social benefits related to wellbeing, education, diet, and community building). A map with the location of the case studies and the neighbourhoods of Bogotá characterised by social stratum is available in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Map of Bogotà with the location of case studies, the names of Bogotá’s neighbourhoods, and their social stratum. Source: Elaborated by the main author using maps available on the open access portal IDECA—https://www.ideca.gov.co/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

The information on each case study, the data on its productivity and consumption, together with measurements of site plans, were elaborated to estimate consumption and production values per m2 for each case study. The results were normalised over a standard period of three months (hence allowing a comparison between case studies with different data collection periods). The normalised data were clustered per garden type, and their characteristics were averaged.

2.5. MCDA and Presence Suitability Index

To evaluate concomitantly diverse characteristics of urban food gardens, we performed a spatial Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) using ArcGIS functions to identify suitable areas for each food garden type. MCDA is a method used to analyse complex problems by structuring, evaluating, and prioritising alternatives [55]. GIS-based MCDA has been studied since the 1990s, with applications in environmental studies, transportation planning, waste management, hydrology, agriculture, and forestry [56]. Each type of urban garden was described through 7 main spatial characteristics (i.e., location, proximity to roads, proximity to rivers, private or public land, minimum footprint range, urban density, and other peculiar features). The characteristics of each garden type can be found in Table 3.

Rasterisation was necessary to perform the two operations at the core of the MCDA, as they can only operate on raster formats. A total of 13 maps, representing the features of the 4 food garden types, were converted to raster format through 3 different tools, depending on the type of feature to display. The Feature to Raster tool was employed with data that had a continuous coverage on the urban territory, such as the social stratum index. The Distance Accumulation tool was used to describe the presence of individual features such as water bodies within the urban area. The Slope tool was employed to render the steepness of the terrain. All raster layers were generated with a pixel size of 5 × 5 m resolution, while the terrain map was set as the base surface for all the distance rasters.

Different garden types could sometimes share the same spatial features, such as the proximity to water bodies, while some maps contained information that needed to be further re-grouped to be optimally employed (e.g., the map “buildings”, which contained information on both height and footprint of the built environment). This led to a final list of 16 maps that were employed during the MCDA elaboration. All the values contained in the 16 raster maps were reclassified to fit a suitability scale from 1 to 10 (respectively, from worst to best). Since the scale of suitability was attributed and not calculated, this step entailed a certain level of subjectivity.

The last step of the MCDA procedure aimed at generating a suitability map for each garden type, based on the reclassified 16 raster maps. To attain this, the Weighted Sum tool was employed to combine the individual suitability rasters referring to the physical features of each garden type. The weighting of spatial variables in the MCDA was based on expert judgement informed by field observations and relevant literature [56], ensuring that local priorities and context guided the process.

2.6. Map Overlaying and Projection of Results

A Presence Suitability Index (PSI) was designed to express the coexistence of the two components describing the distribution of urban agriculture in Bogotá. These are the probability of presence and the suitability of the built environment for each of the 4 food garden types. To calculate this index, we combined the suitability maps for each of the four garden types and the map obtained in the first step of the development of the analytical framework (see Section 2.2). The locations for potential urban food gardens are characterised by the features specified in Table 3.

The Raster Calculator function (ArcGIS Pro 3.1) was used to generate an index map for each garden type through the formula “MCDAmap(garden_type)/*MAXENT map”. In the case of the commercial garden type, the formula changed to “MCDAmap(commercial garden) *MAXENT map*(building_presence)”, which multiplied the results by a binary raster, assigning a value of “0” to all the pixels containing buildings and “1” to the remaining pixels within the study area; this was performed to limit the results to the non-built areas.

The 4 index maps were reclassified into 10 classes of 1 range each, to facilitate the counting of pixels for each class. These final 4 maps were then processed through the Build Raster Attribute Table tool in ArcGIS Pro 3.1, which produced a table for each map (and therefore garden type) summarising the number of pixels for each range of the index. To calculate the areas occupied by each garden type at the city scale, the following steps were undertaken:

- In the corresponding map, the number of cells for each PSI was counted, and the total was multiplied by the area of a single cell (25.34 m2); this would give the total area for each PSI value.

- Each total area was multiplied by its corresponding PSI value, divided by ten; for example, 1/10 of the area for a PSI of 1, and 8/10 for a PSI of 8.

- The total areas for each PSI value were added together to obtain the total area for each garden type.

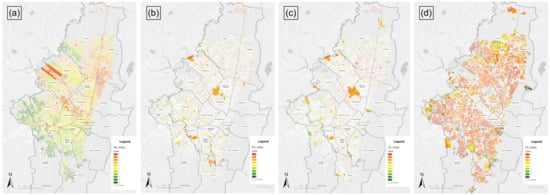

- The 4 Presence Suitability Index maps are shown in the Results section (Figure 4), while the detailed values and results for each garden type can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 4. Suitability Index maps for (a) Home Gardens; (b) Educational Gardens; (c) Community Gardens; and (d) Commercial Gardens, showing the maximised potential expansion for each type. Source: Elaborated by the main author using maps available on the open access portal IDEAC—https://www.ideca.gov.co/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

Figure 4. Suitability Index maps for (a) Home Gardens; (b) Educational Gardens; (c) Community Gardens; and (d) Commercial Gardens, showing the maximised potential expansion for each type. Source: Elaborated by the main author using maps available on the open access portal IDEAC—https://www.ideca.gov.co/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

Once the total area for each garden type was estimated, this was multiplied by the corresponding consumption and productivity values per m2 of each garden type. Consumption and productivity data were averaged per garden type over the 3-month period of the data collection. The total impacts of urban agriculture in Bogotá were obtained by summing the results of the 4 garden types.

3. Results

Results summarised in Table 4 show that in Bogotá, a total of 101,727,922 m2 is suitable for urban agriculture. This value corresponds to roughly 25% of the city’s urban extent (defined as urban and suburban built-up (about 397,230,000 m2 as of 2010 [57]) and is almost three times the space currently occupied by public parks within the city (38,218,538.78 m2).

Table 4.

Summary of the production/consumption estimates split per urban agriculture type over 3 months. Outreach impact comprises residents and participants in events. Estimates are based on the data gathered from the sample of urban food gardens (n = 15), split and averaged by type.

Table 4 shows that if we break down this value, we find that 53% of these spaces are for Home Gardens, 25% are for Commercial Gardens, followed by Educational and Community Gardens, both occupying around 11% of urban land, which is deemed suitable for urban agriculture. We can estimate the total number of food gardens for each type, based on a hypothetical but plausible surface area per type. Home Gardens have the highest number of units (564,430—based on a typical area of 100 m2). Comparing these data with the 2018 census by the National Administrative Department of Statistics of Colombia (DANE), which reported a total of 2,523,519 households within the city area, we estimate that 22% of households practice urban agriculture. The estimated number of Educational Gardens is 78,885 (based on a typical area of 150 m2). Such gardens are typically located next to community centres (e.g., Juntas de Acción Comunales-JAC) and next to schools. According to the geospatial information that was analysed for this study, there are 1377 JACs and 2278 schools within the urban territory of Bogotá, some of which could accommodate this type of garden. An estimated number of Community Gardens and productive gardens is, respectively, 76,548 (typical surface area of 150 m2) and 21,732 (typical surface area of 1200 m2). The estimated numbers should be treated as indicative, as the actual count may vary considerably depending on the real surface areas of the gardens. Table 3 shows that the surface area of the case studies has significant variability. We therefore assigned a typical surface area for each type, based on consultation with local experts.

Data gathered across the sample of 15 gardens suggest that Home Gardens are the most productive (1.28 kg/m2), followed by Commercial Gardens (0.84 kg/m2), Educational Gardens (0.78 kg/m2), and Community Gardens (0.44 kg/m2). If multiplied by the surface areas potentially suitable for each type, food produced could total, respectively, 72,166,972 kg, 21,982,282 kg, 9,299,898 kg, and 5,061,092 kg.

In Home Gardens, assuming a vegetarian diet based on a 2000 kcal daily intake, food for 167,666 people could be grown over three months, with a total of 30,180,001,355 kcal, sufficient for about 2.1% of city dwellers. The water used for irrigation would amount to 1,952,000,370 l, which corresponds to what is consumed by 4% of the total urban population in the same period. Overall, 66% of the compost used could be produced on site.

In Commercial Gardens, the estimated production could support the dietary needs of approximately 610,619 people, 8% of Bogotá’s total urban population. Under a vegetarian diet, these gardens could meet the demand of around 34,872 people over a 3-month period. Commercial Gardens would consume approximately 114,408,411 L of water, equivalent to the domestic use of 15,952 people, less than 1% of the city’s urban population. The compost generated by these gardens (12,176,491 kg) accounts for 38% of the total compost used (32,156,122 kg), indicating that the remaining 62% would need to be sourced externally by farmers.

Educational Gardens could produce up to 9,299,898 kg of food over a 3-month period. This output could meet the dietary requirements of approximately 258,330 people, 3% of Bogotá’s total urban population. Under a fully vegetarian diet, the estimated production amounts to 4,076,485,690 kcal, sufficient for around 22,647 individuals. The total water use during this period would be approximately 199,785,948 L, equivalent to the domestic use of 27,856 people (less than 1% of the urban population). The compost generated within Educational Gardens would total 70,077,061 kg, covering 36% of the total amount required, with the remaining 64% (196,855,422 kg) needing to be purchased by urban farmers.

Community Gardens could produce approximately 5,061,092 kg of food over a 3-month period. This output could meet the dietary requirements of about 2% of the city’s urban population. Under a fully vegetarian diet, the estimated production of 1,558,978,730 kcal would be sufficient to feed approximately 8661 people. The total water consumption of Community Gardens over three months would reach 237,814,707 L, equivalent to the domestic use of 33,158 people, less than 1% of the urban population. The amount of compost produced is considerably higher than in other garden types, approximately 23 kg/m2, compared to around 8 kg/m2 in Educational and Home Gardens.

In terms of resource use, Commercial Gardens are the most water efficient (4.38 L/m2), followed by Educational Gardens (16.88 L/m2), Community Gardens (20.71 L/m2), and Home Gardens (34.6 L/m2). Possibly, this is connected to the professional experience and knowledge of commercial farmers. It is also possible that crops grown in soil need less water than those grown in containers and raised beds, which are likely to be used in Home Gardens, Educational Gardens, and Community Gardens, in combination with in-soil cultivation. It is more difficult to explain the levels of compost produced and used, although it is worth noting that Community Gardens use composting as an educational tool (hence the high level of compost produced), and Educational, Community, and Home Gardens often grow in containers/raised beds that use great amounts of compost.

Data collected from the sample of urban food gardens included social events and the number of people involved in the management of food gardens. Extrapolating an average number of social events organised in the 15 case studies over 3 months, in our scaling-up exercise we estimated 1,607,517 events in Community Gardens (based on an average of 7.8 events organised), 2,839,860 events in Educational Gardens (based on an average of 35.5 events), and 173,861 events in Commercial Gardens (based on an average of 5 events). Finally, we estimated the number of people who may benefit from the food gardens by multiplying an average number of people involved in the management for each type, based on data collected from the case studies. We estimated 1,128,860 people involved in Home Gardens (considering an average of 2 per garden), and 1,071,176, 1,577,700, and 86,928 people involved in the management of, respectively, Community Gardens (14 people per unit), Educational Gardens (20 people per unit), and Commercial Gardens (4 people per unit). Here too, the number of events and people involved is indicative and could considerably change, considering that it is linked to a hypothetical number of food gardens.

4. Discussion

Estimates of the potential of urban agriculture in Bogotà as presented in the Results section are not fully reliable because they are based on a small sample size. Yet such estimates can be appreciated for their capability to point towards optimal conditions, or excessive resource use, or the relation between socio-ecological contextual conditions and productivity. This section elaborates on the results of our study and highlights potential benefits and drawbacks when scaling up urban agriculture in Bogotà.

The spatial analysis developed in this study reveals that approximately 25% of the city’s surface area meets the conditions suitable for urban agriculture. This finding addresses a significant knowledge gap in the literature, where the extent of land potentially available for food production in cities remains largely underexplored or inconsistently quantified [58]. While previous global estimates vary widely, from 1.4% to 36% depending on definitions and methods [24,59], our approach offers a context-sensitive assessment that integrates urban morphology, socio-economic stratification, and garden types. At the urban scale, Saha and Eckelman [60] found that 10% of Boston’s land area and 7.4% of its rooftops are suitable for urban agriculture. In Ilorin (Nigeria), this land area reaches 31.4% [61]. Our estimate for Bogotá, considering local morphology and garden types (Table 3), aligns with these findings.

According to this study, Home Gardens are expected to be the most frequent type of urban food garden in Bogotá, with higher concentrations in poorer areas such as the southern districts of Bosa, Kennedy, Ciudad Bolívar, Tunjuelito, Rafael Uribe, and San Cristóbal (see Figure 3). Pockets of concentration are also expected in other low-income areas, such as the northern part of Usme, the southern part of Suba, the areas surrounding the airport in Fontibón and Engativá, and the area between Los Mártires, La Candelaria, and Antonio Nariño. The estimated productivity of 1.28 kg/m2 is consistent with values reported in other studies, where yields range from 0.5 to 6.6 kg/m2, depending on factors such as climate, crops, garden type (e.g., allotments vs. rooftops), soil type, resource use, as well as the motivations and skills of the practitioners [54,62]. Although productivity can vary significantly, higher yields are generally more common in experimental plots and in the Global North, while in the Global South, productivity levels tend to be lower and more in line with the estimates reported in this study [63,64].

If we calculate the amount of food produced in the three low-income districts (which roughly cover an area of 13 km2) where there is a greater concentration of this type of garden (Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, Usme) we find that food for 26% of the population of these three areas can be grown there. According to the citizen perception survey Bogotá cómo vamos, 24% of 1500 respondents, 42% of whom belonged to the social strata 1 and 2, claimed to have consumed less than three daily meals in the month before their interview [65]. Hence, food production from Home Gardens can be a vital resource for a significant share of the population.

The estimated high productivity of Home Gardens compared to the other types suggests a maximised density of plants, possibly linked to the scarcity of space characterising informal residential areas, where the majority of potential Home Gardens are located.

Commercial Gardens are the second largest type, albeit with the lowest Presence Suitability Index. This means that there are fewer, larger plots of land that are deemed suitable for this type of garden. Commercial Gardens are more concentrated in the peripheral areas of Bogotá that have closer connections with rural areas, such as the districts of Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, Usme, Suba, and Fontibón. Pockets of concentration can also be found near San Luis, to the east of the district of Chapinero, and in the southern part of San Cristóbal.

The scaling-up exercise shows that Commercial Gardens in Bogotá could generate a revenue of GBP 35,837,085 over the course of three months, equivalent to 45,923 jobs (0.5% of Bogotá’s urban population) with a Colombian minimum wage standard. This number is roughly half of the people benefitting from this type of garden (86,928), considering an average of four farmers per garden multiplied by a total of 21,732 gardens of 1200 m2. If we consider the three districts with the highest concentration of these gardens (namely, Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, and Usme), the value generated is GBP 12,511,692 (9,132,622 m2 per GBP 1.37 over the course of three months), which in turn can provide jobs for 16,033 people. Although this value constitutes less than 1% of the population of these three districts (1,766,229 in 2021), it is worth noting that the expected concentration of Commercial Gardens in these districts is in line with estimates in the quality-of-life report Bogotá cómo vamos, which states that these areas have had the highest business recovery rates after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Educational Gardens appear geographically scattered and not very dense, as these are generally located in community buildings or on private properties. They are more frequent in low-income districts in the southern belt of the city (i.e., Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, Kennedy, and Usme) and also in the area of Santa Fe surrounding the Candelaria district. This is consistent with a greater concentration of buildings and public land in this historical central area.

The main purpose of Educational Gardens is to raise awareness of sustainability-related topics such as recycling, knowledge of local plant and animal species, vegetarian diets, and compost production. Hence, their main impact can be measured with the number of events organised (2,839,752) and the number of people involved in the management of gardens (1,577,700). In the three districts where their highest concentration (the low-income areas of Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, and Santa Fe), 282,272 people (19% of the population of these areas) could be reached by social activities.

Community Gardens were estimated to occupy the smallest area in Bogotá. However, their low coverage does not necessarily equate to low citizens’ participation. This type of garden is often located in public parks, with the highest concentrations in the southern districts of Kennedy, Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, San Cristóbal, as well as (albeit with lower concentration) in the central areas of the city and the northern district of Suba.

The purpose of Community Gardens is to strengthen community cohesion through urban agriculture, which explains the low amounts of food (and calories) produced. Observations during data gathering sessions suggested that composting is used as a community activity, with residents bringing their home waste and helping to process it. In Community Gardens, the compost produced corresponds to 89% of what is consumed, a considerable quantity, considering the high production levels. Once more, this may be explained through the engagement/social role of this activity. In fact, composting and soil enhancing were included in social events organised by five of the gardens in the sample.

Our estimate shows that these gardens could organise 1,607,424 social events. If we compare the number of social events to the 6456 cultural events that were held across Bogotá in 2022, according to the quality-of-life report Bogotá cómo vamos, we see that Community Gardens could become instrumental in increasing participation in the urban social life. If we consider the districts with a higher concentration of this type of garden (Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, and Kennedy), people reached through activities could be 346,458, which corresponds to 14% of their total population.

Overall, results indicate that the combined potential of Home Gardens, Commercial Gardens, Educational Gardens, and Community Gardens could meet approximately 40% of the dietary requirements. This figure is remarkably high in comparison to findings from other studies that consider ground-level plots [60,66]. Nevertheless, as emphasised by other studies, open-field urban agriculture is insufficient to achieve realistic food self-sufficiency, especially in densely populated urban areas [67,68,69]. These findings address a critical knowledge gap concerning the spatial extent and productivity potential of urban agriculture, particularly in rapidly growing cities of the Global South. The case of Bogotá highlights how integrating field studies and GIS-based spatial analysis can provide a robust estimate of urban agriculture’s capacity to contribute meaningfully to local food security and dietary needs, underscoring the importance of local conditions in shaping urban food systems.

Bogotà is not the only city in Colombia to deliver programmes on food security with urban agriculture as a key component. Medellin and Cali are delivering such programmes too [11]. An assessment on the impact of the programme claims that this led to the establishment of a network of farmers’ markets, food stores, and food banks that increased food security in a city where 25% of children are malnourished [70]. Another study based on the Bogotá Botanical Garden dataset suggests that urban food gardens can play an important role in strengthening soil quality and ecosystems functions in dense urban environments [71]. Against this backdrop, an initial application of the analytical framework presented in this study suggests areas where policy can further strengthen impact by supporting, for example, Home Gardens, which show great potential in terms of land availability. Comparable evidence from other Global South cities, such as Hawassa in Ethiopia [72] and Ilorin in Nigeria [58], confirms that urban agriculture contributes significantly to food security and socio-economic inclusion, reinforcing the broader applicability of the Bogotá case.

Within urban agriculture studies, many spatial analytical frameworks have been developed, with diverse scopes and aims. For example, many frameworks have been designed to evaluate productivity based on average data on urban agriculture or agricultural production and land availability [73]. Other spatial analysis frameworks use participatory mapping or interviews combined with GIS. For example, Nkosi et al. [74] developed weighted criteria to identify suitable land to be converted to urban agriculture through stakeholder consultation in Johannesburg.

Other frameworks combine the Analytical Hierarchy Process or Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, Suitability Analysis, and spatial analysis. For example, a framework based on the Analytical Hierarchy Process was designed to identify suitable areas for cultivation with criteria that include soil pollution [75]. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis was used for a framework developed by Kamali et al. [76] to identify suitable areas for promoting the production of urban fresh produce for different social groups with a view to advancing food justice and spatial equity. Our analytical framework is designed with a higher level of complexity as it combines Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis and spatial regression to identify drivers of expansion, as well as a more nuanced approach to determine levels of productivity.

5. Conclusions

To date, few studies have examined how context impacts the capability of urban agriculture to expand and produce. This study has demonstrated how key drivers enabling the implementation of urban food gardens can be identified, and how this, in turn, can lead to mapping all surface areas where urban agriculture can potentially be implemented. It has also demonstrated that productivity is influenced by the type of practice and that to be reliable, estimates must take into account the diverse levels of input/output corresponding to each type.

The application of the analytical framework to the city of Bogotá shows that approximately 25% of the city’s area could be used to grow food, with Home Gardens taking up more than half of such a surface area. In turn, this suggests that space may not be a limiting factor for the expansion of urban agriculture.

This analytical framework can support planning and urban policy in many ways. For example, the estimate showing Home Gardens as the type of urban food production occupying the largest share of suitable land for urban agriculture, is not only confirming that food growing is a consolidated practice for many households but also that programmes and investments on—say—water infrastructure are necessary and likely to lead to higher levels of food security in particular neighbourhoods. Moreover, although not explored in this study, the analytical framework can be used as a simulation tool by changing drivers and comparing results.

This study has some limitations. To demonstrate its application, we have used data collected from a small sample of urban food gardens. This may result in estimates that require further analysis to be considered fully reliable. The concept of potentially suitable land adopted here refers to areas that meet the characteristics of the four types of urban food gardens, rather than land that is immediately usable. Land ownership, rooftop structural suitability, or soil pollution are likely to reduce the surface area available for food growing. A comprehensive and reliable application of the framework would require evaluating a wider range of factors. Yet our findings point to reflections that can be valuable for the ongoing debate on productivity in urban agriculture.

This analytical framework can only be performed on spatialised data, hence limiting its applicability to cities that have such data. Furthermore, the choice and weighting of the different features for the Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis can substantially modify the outcomes of the estimate and, therefore, must carefully consider the local context and priorities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122398/s1, List of Layers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M., S.C., F.L. and G.P.; Methodology, V.M., S.C., F.L. and G.P.; Software, V.M., F.L. and G.P.; Validation, V.M.; Formal analysis, V.M.; Investigation, V.M.; Data curation, V.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, V.M., S.C., F.L., G.P. and J.H.-G.; writing—review and editing, V.M., S.C., F.L., G.P. and J.H.-G.; Visualisation, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: IDECA https://www.ideca.gov.co/buscador (accessed on 6 September 2024); and Datos Abiertos: https://datosabiertos.bogota.gov.co/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Artmann, M.; Sartison, K. The role of urban agriculture as a nature-based solution: A review for developing a systemic assessment framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chan, F.K.S.; Li, G.; Xu, M.; Feng, M.; Zhu, Y.G. Implementing urban agriculture as nature-based solutions in China: Challenges and global lessons. Soil Environ. Health 2024, 2, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, T.; Baptista, M.; Wilker, J.; Kanai, J.M.; Giusti, M.; Henderson, H.; Rotbart, D.; Espinel, J.-D.A.; Hernández-Garcia, J.; Thomasz, O.; et al. Valuation of urban nature-based solutions in Latin American and European cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 91, 128162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. Available online: https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- NHS England. Green Social Prescribing. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/social-prescribing/green-social-prescribing/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Hamilton, A.J.; Burry, K.; Mok, H.F.; Barker, S.F.; Grove, J.R.; Williamson, V.G. Give peas a chance? Urban agriculture in developing countries. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, J. Hábitat popular, un modo alternativo de producción de espacio para América Latina? In Estética de Los Mundos Posibles: Inmersión en la Vida Artificial, las Artes y las Prácticas Urbanas; Hernandez, I., Ed.; Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo, D.; Guzmán, L.A.; Oviedo-Dávila, N. Productive exclusion: Accessibility inequalities and informal employment in Bogotá. Geoforum 2025, 159, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, J.; Caquimbo-Salazar, S. Urban Agriculture in Bogotá’s informal settlements. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape and Food; Zeunert, J., Waterman, T., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Suzunaga, J.; Soler, J.; Wilson, A. Peri-urban agriculture as quiet sustainability: Challenging the urban development discourse in Sogamoso, Colombia. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaño-Herrera, D.A.; Varela-Martínez, D.A.; Chenet, J.G.; García-García, D.A.; Díaz-Verus, S.D.; Rodríguez-Urrego, L. Driving sustainable urban development: Exploring the role of small-scale organic urban agriculture in Bogotá, Colombia: A case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Guerrero, M.C.; Amarillo-Suárez, A.R. Socioecological features of plant diversity in domestic gardens in the city of Bogotá, Colombia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 28, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battersby, J.; Marshak, M. Growing Communities: Integrating the Social and Economic Benefits of Urban Agriculture in Cape Town. Urban Forum 2013, 24, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duží, B.; Frantál, B.; Rojo, M.S. The geography of urban agriculture: New trends and challenges. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, S.T. Multifunctional Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Land Use Planning in the United States. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2499–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B.; Mendes, W. Municipal Food Strategies and Integrated Approaches to Urban Agriculture: Exploring Three Cases from the Global North. Int. Plan. Stud. 2013, 18, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Clift, R.; Christie, I. Urban Cultivation and Its Contributions to Sustainability: Nibbles of Food but Oodles of Social Capital. Sustainability 2016, 8, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N. Why farm the city? Theorizing urban agriculture through a lens of metabolic rift. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, H.-F.; Williamson, V.G.; Grove, J.R.; Burry, K.; Barker, S.F.; Hamilton, A.J. Strawberry fields forever? Urban agriculture in developed countries: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. Nourishing the city: The rise of the urban food question in the Global North. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1379–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, F.; Pennisi, G.; Michelon, N.; Minelli, A.; Bazzocchi, G.; Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Gianquinto, G. Features and Functions of Multifunctional Urban Agriculture in the Global North: A Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 562513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornaghi, C. Critical geography of urban agriculture. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.A.; Hamm, M.W. A view from the south: Bringing critical planning theory to urban agriculture. In Global Urban Agriculture; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, N.; Stuhlmacher, M.; Miles, A.; Uludere Aragon, N.; Wagner, M.; Georgescu, M.; Herwig, C.; Gong, P. A Global Geospatial Ecosystem Services Estimate of Urban Agriculture. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermini, P.V.; Delprino, M.R.; Giobellina, B.L. Mapping of urban and peri-urban agriculture in the Santa Rosa-Toay metropolitan area: Methodological approaches for territorial reading. Rev. Investig. Agropecu. 2017, 43, 280–290. [Google Scholar]

- Fanfani, D.; Duží, B.; Mancino, M.; Rovai, M. Multiple evaluation of urban and peri-urban agriculture and its relation to spatial planning: The case of Prato territory (Italy). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelan, E. GIS-based multi-criteria analysis for sustainable urban green spaces planning in emerging towns of Ethiopia: The case of Sululta town. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafius, D.R.; Edmondson, J.L.; Norton, B.A.; Clark, R.; Mears, M.; Leake, J.R.; Corstanje, R.; Harris, J.A.; Warren, P.H. Estimating food production in an urban landscape. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, J.P.; Foster, A.; Borgman, M.; Meerow, S. Ecosystem services of urban agriculture and prospects for scaling up production: A study of Detroit. Cities 2022, 125, 103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Meerow, S.; Turner, B.L. Planning urban community gardens strategically through multicriteria decision analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Latin America & Caribbean: Urbanization from 2013 to 2023. Statista. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/699089/urbanization-in-latin-america-and-caribbean/#:~:text=Urbanization%20in%20Latin%20America%20&%20Caribbean%202023&text=Urbanization%20means%20the%20share%20of,in%20urban%20areas%20and%20cities (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Nail, S. Capítulo introductorio. Los alimentos y las ciudades. In Alimentar las Ciudades: Territorios, Actores, Relaciones; Publicaciones Universidad Externado de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018; pp. 19–62. [Google Scholar]

- Camara de Comercio de Bogota. Documento de Contexto Bogotá. 2025. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.ccb.org.co/items/1ff50376-3927-413d-820a-8c29780d6524 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- García, A.; Olivieri, F.; Larrumbide, E.; Ávila, P. Thermal comfort assessment in naturally ventilated offices located in a cold tropical climate, Bogotá. Build. Environ. 2019, 158, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEAM. 2018—Carácterísticas Climatológicas De Ciudades Principales Y Municipios Turísticos. Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales: 48. Available online: http://www.ideam.gov.co/documents/21021/418894/Características+de+Ciudades+Principales+y+Municipios+Turísticos.pdf/c3ca90c8-1072-434a-a235-91baee8c73fc%0Ahttp://www.ideam.gov.co/documents/21021/21789/1Sitios+turisticos2.pdf/cd4106e9-d608-4c29-91cc-16bee91 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Climate Data. Bogotá Climate—Colombia. 2025. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/south-america/colombia/bogota/bogota-5115/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Anselm, N.; Brokamp, G.; Schütt, B. Assessment of Land Cover Change in Peri-Urban High Andean Environments South of Bogotá, Colombia. Land 2018, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, Q.; Germán, A.; Kotilainen, J.; Salo, M. Reterritorialization Practices and Strategies of Campesinos in the Urban Frontier of Bogotá, Colombia. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Lee, M.I.; Burq, L. Santa Rosa siembra un sistema. In Alimentar las Ciudades: Territorios, Actores, Relaciones; Universidad del Externado: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Población, Total—Colombia. 2025. Available online: https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CO (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Duquino Rojas, L.G.; Vinasco Ñustes, F.A. Urbanización de tierras agrícolas de borde en la planeación urbana contemporánea de Bogotá. In Alimentar las Ciudades. Territorios, Actosres, Relaciones; Universidad del Externado de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018; pp. 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogotá. Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial_Bogotá Reverdece 2022–2035. Available online: https://bogota.gov.co/mi-ciudad/pot-bogota-reverdece-2022-2035/articulado-del-pot-bogota-reverdece-2022-2035 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- FAO. Growing Greener Cities in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2014. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/e246828b-e2bf-4a8e-b279-5115140760e8/content (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Leandro Hernandez, A.V. La Agricultura Urbana en Bogotá: Como Llegar a Tener un Modelo de Negocio [Programa de Administración de Empresas]; Universidad escuela de administración de Negocios: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Murillo, S.A. Eco territorios: Espacios resilientes de interacción rural y urbana. Res. Archit. 2018, 3, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.; Sebastian, A.R.; Perego, V.M.E. Future Foodscapes; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga Valencia, L.M.; Leal Celis, D.C. Agricultura Urbana en Bogotá. Una Evaluación Externa-Participativa; Universidad Del Rosario: Bogotá, Colombia, 2011; pp. 1–168. Available online: https://repository.urosario.edu.co/handle/10336/2880 (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Wurwarg, J. Urbanization and Hunger: Food Policies and programs responding to urbanization, and benefitting the urban food in three cities. J. Int. Aff. 2014, 67, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Rodriguez, J.N. Agricultura Urbana en América Latina y Colombia: Perspectivas y Elementos Agronómicos Diferenciadores. Bachelor’s Degree, Universidad Nacional Abierta Y A Distancia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas Urbanas: ¿Qué Son y Cuántas Hay en Bogotá? Available online: https://oab.ambientebogota.gov.co/huertas-urbanas-que-son-y-cuantas-hay-en-bogota/ (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Bogotá mi huerta. Bogotá Mi Huerta: El Hogar de la Agricultura Urbana—Este Sitio es un Espacio de Información de y Para todos Los Huerteros de Bogotá. Available online: https://bogotamihuerta.jbb.gov.co/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- IDECA. Available online: https://www.ideca.gov.co/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Datos Abiertos (No Date). Available online: https://datosabiertos.bogota.gov.co/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Dorr, E.; Hawes, J.K.; Goldstein, B.; Fargue-Lelièvre, A.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Specht, K.; Fedeńczak, K.; Caputo, S.; Cohen, N.; Poniży, L.; et al. Food production and resource use of urban farms and gardens: A five-country study. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, M.; Kuller, M.; Lacroix, S.; Vanrolleghem, P.A. A critical review of multicriteria decision analysis practices in planning of urban green spaces and nature-based solutions. Blue-Green Syst. 2023, 5, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.; Devillers, R.; Luther, J.E.; Eddy, B.G. GIS-Based Multiple-Criteria Decision Analysis. Geogr. Compass 2011, 5, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas of Urban Expansion, Bogotà. Available online: http://atlasofurbanexpansion.org/cities/view/Bogota#:~:text=2001%2D2010-,Urban%20Extent,urban%20extent%20was%2032%2C123%20hectares (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Thebo, A.L.; Drechsel, P.; Lambin, E.F. Global assessment of urban and peri-urban agriculture: Irrigated and rainfed croplands. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 114002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bren d’Amour, C.; Reitsma, F.; Baiocchi, G.; Barthel, S.; Güneralp, B.; Erb, K.H.; Haberl, H.; Creutzig, F.; Seto, K.C. Future urban land expansion and implications for global croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8939–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Eckelman, M.J. Growing fresh fruits and vegetables in an urban landscape: A geospatial assessment of ground level and rooftop urban agriculture potential in Boston, USA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduloju, O.T.B.; Akinbamijo, O.B.; Bako, A.I.; Anofi, A.O.; Otokiti, K.V. Spatial analysis of urban agriculture in the utilization of open spaces in Nigeria. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, R.; Kristiansen, P.; Rader, R. Small-scale urban agriculture results in high yields but requires judicious management of inputs to achieve sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Murakami, A.; Tsuchiya, K.; Palijon, A.M.; Yokohari, M. A quantitative assessment of vegetable farming on vacant lots in an urban fringe area in Metro Manila: Can it sustain long-term local vegetable demand? Appl. Geogr. 2013, 41, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, F.T.; Evans, D.L.; Falagán, N.; Hardman, C.A.; Kourmpetli, S.; Liu, L.; Marshall, R.; Mead, B.R.; Davies, J.A. How much food can we grow in urban areas? Food production and crop yields of urban agriculture: A meta-analysis. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2022EF002748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogotá Cómo Vamos. Encuesta de Percepción Ciudadana. 2022. Available online: https://bogotacomovamos.org/encuesta-percepcion-ciudadana-2022/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Pulighe, G.; Lupia, F. Multitemporal Geospatial Evaluation of Urban Agriculture and (Non)-Sustainable Food Self-Provisioning in Milan, Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.J.; Moskal, L.M. Urban food crop production capacity and competition with the urban forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 15, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, T.; Yang, A.; Hamm, M.W. Consolidating the current knowledge on urban agriculture in productive urban food systems: Learnings, gaps and outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1637–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpe, M.; Lachman, J.; Wang, L.; Marcelis, L.F.; Heuvelink, E. Potential for urban agriculture: Expert insights on sustainable development goals and future challenges. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 57, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citego. Bogotá Sin Hambre: Bogota Without Hunger. 2018. Available online: https://www.citego.org/bdf_fiche-document-1213_en.html#:~:text=Implementation,The%20program%20teaches%20and%20encourages%20participants%20to%20grow%20food%20in,reducing%20household%20spending%20on%20food (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Guzman-Molina, J.; Carrazana-Rosales, G.; Karthe, D.; Rodriguez, W.; Caucci, S. Sustainability Composite Indicator for the Assessment of Resilient Urban Agriculture and Urban Development. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, M.B.; Gelebo, G.; Girma, G. Urban expansion and agricultural land loss: A GIS-Based analysis and policy implications in Hawassa city, Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1499804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; McPhearson, T.; Sampei, Y.; McGrath, B. Assessing urban agriculture potential: A comparative study of Osaka, Japan and New York city, United States. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, D.S.; Moyo, T.; Musonda, I. Unlocking land for urban agriculture: Lessons from marginalised areas in Johannesburg, South Africa. Land 2022, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, F.; Hosseinpour, N. GIS-based land-use suitability analysis for urban agriculture development based on pollution distributions. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 106426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.I.; Nazari, R.; Karimi, M.; Nikoo, M.R. Mapping the future of urban agriculture: A GIS-based spatial framework for food equity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 131, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).