Abstract

This study builds on a previously developed typo-morphological method used for the rural architecture of the “Capo Due Rami” area and tests its transferability to the northern sector of Sabaudia within the Pontine reclamation system. Beyond the historical, typological, and landscape dimensions explored earlier, this research adds a further analytical component focused on the relationship between settlement form and territorial planning. This extension represents the major methodological contribution of the study, allowing the repetitive structure of Opera Nazionale Combattenti farm units to be interpreted not only as a building system but also as an implicit territorial-planning device. The case study, located in the northern sector of Sabaudia, explores the relationships between the colonial settlements of the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC), the agrarian framework, and the reclamation infrastructures, interpreting the repetition of settlement models as an implicit form of territorial planning. Using an integrated framework based on field surveys, archival materials, and multiscale cartographic analyses, the observation sheets show how architectural features, land-division schemes, and reclamation infrastructures are structurally interrelated. The results show that this new analytical dimension enhances the method’s interpretative capacity, highlighting the role of typological standardization in shaping the spatial and cultural structure of the reclaimed landscape. They reveal the morphological and functional consistency between architecture and landscape. Overall, the investigation confirms the coherence and replicability of the expanded approach. It shows that rural architecture is not only the material expression of a productive model but also an active agent in constructing and regulating the Pontine agrarian territory. Rural building emerges not only as the material outcome of a productive model but also as an active agent in shaping the agrarian territory. The research helps establish a comparative framework for interpreting Italian rural landscapes, supporting the valorization of vernacular heritage and reflection on the implicit planning principles embedded in typological architecture.

1. Premise

This study advances an analytical framework previously applied to the rural architecture of the “Capo Due Rami” area [1]. The approach was originally formulated within a broader research trajectory investigating the interrelations between vernacular constructions and agrarian landscapes, a line of inquiry initially developed through the case of winery architecture in Tuscany [2]. The present work extends this methodological framework to the Pontine reclamation, testing its applicability within a distinct territorial context and refining its interpretative capacity. This extension is not intended as a mere replication of the previous investigation; rather, it constitutes a necessary step for assessing the epistemic robustness of the method and for evaluating how its analytical structure performs when applied to a more complex territorial configuration, such as that of the Pontine reclamation.

Building on previous applications of the typological verification method and on research into the relationship between vernacular architecture and agrarian landscape transformations, the present study widens the analytical scope. It examines another case of particular relevance within Italian rural architecture: the reclamation area of Sabaudia and the buildings constructed by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC). In doing so, the study introduces an additional analytical dimension that was not addressed in the earlier work—namely, the intermediate scale of the farm-unit system—which enables a systematic examination of the relationships among building form, plot organization, access hierarchies, and the broader reclamation infrastructures. The original morphotype of these structures represents the archetype and reference model for much of Italy’s historical rural building tradition.

In this perspective, the repetition of the experiment is not treated as a merely applicative exercise. Rather, it functions as a cognitive device for testing, in a different rural context, the method’s ability to interpret typological repetition as a generative principle of the landscape. This replication thus assumes the form of a controlled scientific test, allowing the invariant elements of the method to be distinguished from those that emerge only when the analytical model is applied to broader and more complex agrarian structures. Building on these premises, Section 2 outlines the conceptual and geographical framework required to situate the investigation within the wider discourse on rural and agrarian landscapes.

2. Introduction

This study builds on the investigation carried out in the “Capo Due Rami” area south of Rome, where a typological analysis method was applied to a selected group of rural dwellings. The extension of the research to the northern sector of Sabaudia is not intended as a simple repetition of that work, but as a methodological advancement. Within this broader and more structured reclamation context, the study tests the transferability of the typological method and refines it through the introduction of an intermediate analytical scale, enabling a more articulated interpretation of the relationships between rural architecture, agrarian organization, and territorial structure.

From this perspective, the investigation focuses on the northern area of Sabaudia, a portion of high environmental and cultural value within the territory of the city of Latina, south of Rome, in the Lazio Region. Its specific features represent a paradigmatic expression of the Pontine reclamation system. The aim of this research is to verify the coherence and transferability of the aforementioned typological analysis method while simultaneously identifying the transformation processes affecting vernacular architecture and the agrarian landscape system. For this purpose, the following section—which is necessarily extensive—introduces the framework of definitions and theoretical premises that delimit the research domain and set forth the hypotheses and thesis to be validated.

Clarifying these premises is essential before introducing the theoretical framework of the study. This clarification also outlines the overall structure of the article, which moves from the theoretical foundations to the analytical model and, finally, to the multi-scalar application of the method in the Sabaudia case study.

2.1. International Theoretical Foundations of Rural and Agrarian Landscapes

Over the past century, scholarly interpretations of rural territories and agrarian landscapes have progressively converged towards a holistic and multi-scalar view of the rural environment, conceived as the outcome of long-term interactions among natural systems, settlement forms, agricultural practices, and socio-cultural dynamics [3]. Understanding this evolution is essential for situating the present study within a consolidated yet still evolving scientific debate.

This contemporary perspective builds on a stratified tradition of studies whose roots extend to the early twentieth century. The first systematic attempts to interpret rural buildings as expressions of territorial organization—though still based on tentative geographical models—were significantly advanced by Giuseppe Pagano and Daniel Guarnerio in their work for the VI Milan Triennale [4]. There, dispersed rural architecture was framed not merely as a vernacular phenomenon but as a cultural and spatial construct inseparable from agrarian life and productive rhythms [5]. These early reflections laid the cultural and methodological foundations for subsequent systematic research.

A decisive step towards methodological systematization was achieved shortly afterwards with Renato Biasutti’s CNR series “Ricerche sulle dimore rurali in Italia” (launched in 1938), which introduced the first rigorous criteria for analyzing rural dwellings within their geographical and agrarian contexts [6]. The thirty volumes that followed—culminating in the synoptic text edited by Barbieri and Gambi—consolidated a multidisciplinary approach that combined geography, anthropology, architecture, and agrarian sciences, and remain a fundamental reference for typological and territorial studies [7]. This consolidation enabled further methodological developments in the second half of the twentieth century.

During this period, research expanded considerably, progressively integrating construction studies, territorial analysis, and architectural interpretation. The works of Di Giulio, Zaffagnini, and Mambriani [8] exemplify this widening of perspectives, which increasingly recognized rural architecture as a complex territorial artifact shaped by environmental matrices and socio-productive structures. As the debate matured, new scholarship revisited earlier contributions through updated interpretative lenses.

From the 1990s onwards, further studies refined these themes. In this context, Bilò’s work reframed the aesthetic and perceptual interpretation of rural landscapes, emphasizing the documentary value of historical investigations and their early sensitivity to visual and environmental dimensions [9].

Parallel developments in European literature also contributed to redefining the conceptual boundaries of rural and agrarian landscapes. Donadieu’s notion of the “process of agricultural land use” [10]—describing the decline of cultivated areas alongside expanding urbanization and re-naturalization—offers a useful lens for interpreting contemporary dynamics, including those affecting the Pontine territory. More recently, Gkartzios, Gallent, and Scott have challenged planning orthodoxies that treat rural areas as “residual and subordinate spaces,” proposing instead a framework grounded in the interaction of four forms of rural capital—built, economic, land-based, and socio-cultural—whose evolution drives rural transformation [11]. In this study, the concept of landscape is employed in its scientific sense, as a dynamic system shaped by long-term interactions between natural and anthropogenic components, whose identity stems from the structural relations among settlement forms, productive practices, and environmental frameworks.

This broader European reflection resonates with long-standing Italian debates on the relationship between built form and territorial identity. Within the Italian context, this evolution is closely tied to efforts to clarify the conceptual foundations of the built environment. As Gregotti argued, architectural form cannot be understood in isolation but must be interpreted through the morphological, environmental, and functional relationships that define its spatial condition [12,13]. Similarly, territorialist scholarship—especially in the work of Magnaghi—has emphasized the coevolution of settlement systems, productive practices, and environmental structures, interpreting rural landscapes as expressions of territorial capital and cultural identity [14].

2.2. Rural Architecture as a Structural Component of the Landscape

Historically framed through an aesthetic–picturesque lens, here, rural architecture is interpreted as a structural component of the spatial organism, expressing functional, morphological, and cultural values that contribute to the identity and long-term evolution of agrarian landscapes. Within this multilayered conceptual setting, the Italian regulatory framework provides a definition of landscape that is both operational and non-aesthetic.

According to the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape (Legislative Decree 42/2004) [15], landscape is the portion of territory whose character derives from the interaction between natural and human factors. This formulation, which understands landscape as a “product of civilization” [16], affirms the structural interdependence of natural and built components. Applied to rural territories, the agrarian system can therefore be understood as land predominantly used for agricultural, pastoral, or forestry purposes, whose physiognomy is shaped by the morphological transformations produced by human productive practices [17].

Within this framework, rural territories emerge as long-term products of the interaction among agricultural practices, settlement structures, and environmental systems. Rural buildings thus form an integral part of landscape identity, not only because they embody productive functions and local construction cultures, but also because they materially shape the spatial and perceptual organization of the territory [18].

Since the landscape results from the coevolution of human activities and environmental matrices, built forms actively shape its structure and meaning, contributing to the ecological, functional, and symbolic relationships that characterize rural space. In this perspective, rural architecture—whether originally designed for residential, agricultural, or zootechnical purposes—constitutes a structural component of both the agrarian system and the socio-economic fabric of the countryside. Its forms operate as material markers of territorial organization, expressing the stratified relationships among settlements, land use practices, and infrastructural networks. These considerations provide the basis for interpreting historically planned rural landscapes such as the Pontine territory.

On this basis, the Pontine reclamation and the rural settlements constructed by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti—at the center of the present study—offer a privileged field of observation for understanding how the formal configuration of rural buildings contributes to the construction and long-term evolution of the agrarian system. The ONC model provides an exemplary case in which architectural types, land-division schemes, and reclamation infrastructures were conceived as parts of a coherent territorial device, offering concrete evidence of the deeply stratified cultural and planning lineage outlined above.

This lineage of studies converges toward a contemporary view of the landscape as a multi-scalar socio-spatial construct, within which rural architecture operates both as material evidence and as an organizational device. It is within this interpretative framework that the present investigation is situated.

2.3. The Case of Sabaudia and the Territorial Organization of the ONC

In continuity and coherence with the theoretical framework outlined above, the focus of the research is placed on the area of the Agro Pontino, adopted as the geographical and historical context of reference. This choice does not merely respond to a criterion of localization but reflects the intention to explore a territory in which the relationship between agrarian planning, rural architecture, and the construction of the landscape manifests itself in an exemplary and still recognizable way [19]. Within this structural relationship, the Pontine reclamation provides a historically unique example of coordinated rural planning.

The Agro Pontino offers an exemplary context in which the relationships among agrarian planning, rural architecture, and landscape construction remain clearly legible. Within this territory, the interventions of the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC) generated a coherent system of land division, hydraulic infrastructures, and settlement patterns that profoundly shaped the morphology of the reclaimed plain, as documented in historical sources and cartographic reconstructions [20].

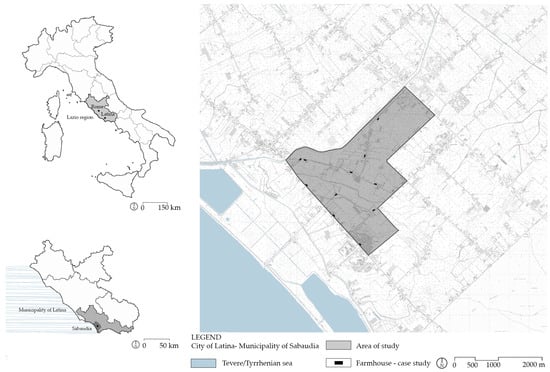

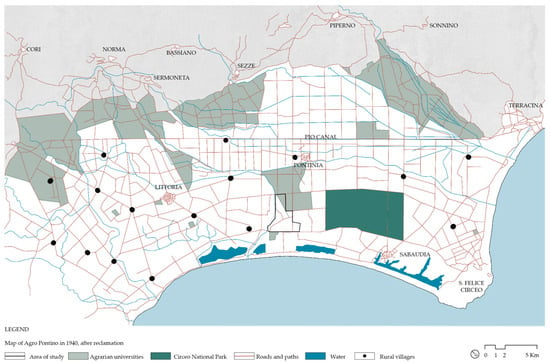

The northern sector of Sabaudia—shown in Figure 1—constitutes one of the most representative portions of this system. Its regular agrarian grid, the alignment of farm plots with drainage and irrigation canals, and the distribution of ONC farmhouses reveal a unified spatial design that integrates productive, settlement, and environmental components. This configuration provides the spatial framework within which the present study applies and further develops the previously established typological method.

Figure 1.

Northern Area of Sabaudia: Delimitation of the Study Field within the Context of the Pontine Reclamation. © Authors, 2025.

The regular structure of the farm plots, the articulation of drainage and irrigation infrastructures, the layout of the road network, and the distribution of rural nuclei delineate a unified and functional territorial system, an expression of an “integrated planning” [21] that harmonizes productive, settlement, and environmental needs.

In this perspective, the Sabaudia case offers an ideal context for examining how the repetition of rural building types interacts with the agrarian structure and the reclamation network, shaping both the formation and persistence of the Pontine landscape. This territorial coherence provides the basis for testing the methodological advancement proposed in this study.

2.4. Research Thesis and Hypotheses

The rural architecture produced by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC) demonstrates a coherent relationship among building typology, agrarian layout, and reclamation infrastructures. The repetition of farm units, the regularity of the land-division system, and the integration of hydraulic and road networks indicate that the ONC interventions functioned as a form of integrated rural planning, operating well beyond the architectural scale. From this perspective, the research advances the thesis that the building typology, when integrated with the agrarian structure and the infrastructural system of the reclamation, operates as a planning device capable of shaping the configuration of the agrarian Landscape system beyond the architectural scale.

On these grounds, the research formulates three hypotheses that articulate the multi-scalar nature of the ONC settlement system. Based on this premise, the research advances three complementary hypotheses:

- Morphological Hypothesis–The repetition of building types and farm layouts generates a coherent settlement structure capable of organizing the agrarian landscape according to principles of productive rationality.

- Territorial Hypothesis–The farm units, integrated with the hydraulic and road networks of the reclamation, constitute an infrastructural framework operating at the landscape scale.

- Interpretative Hypothesis–The combined reading of architectural, settlement, and infrastructural components redefines rural architecture as an active device in the construction and structuring of the Pontine agrarian landscape.

The objective of this research is to verify the coherence of the hypotheses through the typological and morphological analysis of the northern area of Sabaudia, taking the farmhouses of the ONC as an interpretative key to understanding the processes of formation, transformation, and persistence of the Pontine agrarian Landscape.

The study verifies these hypotheses through a typological and morphological analysis of the northern area of Sabaudia, using the ONC farmhouses as an interpretative key. In doing so, it extends the method previously applied to the “Capo Due Rami” case study [1], adapting it to a broader and more structured reclamation context. The three research questions guiding this investigation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questions the research aims to address—© authors, 2025.

Once the epistemic framework has been established, the case study introduced, and the research hypotheses formulated, the article proceeds with the following sections. Section 3 (Background) outlines the theoretical references that informed the development of the methodological model. Section 4 (Materials and Methods) presents the case study and describes the use of observation sheets for the morpho-typological analysis of the ONC farmhouses in the Sabaudia area. Section 5 (Results and Discussion) reports the outcomes of the analysis and offers the related critical interpretation, while Section 6 (Conclusions) summarizes the main findings and identifies future research directions.

3. Background

This section outlines the methodological and bibliographic framework of the investigation, clarifying the continuity with the model previously applied to the “Capo Due Rami” case study and the elements that characterize its extension to the northern area of Sabaudia. The theoretical references guiding the development of the methodological model are summarized, providing the framework for the analytical structure adopted in the following sections. Before presenting the analytical model, it is necessary to contextualize the institutional and territorial framework within which the ONC intervention was conceived.

3.1. The Comparative Framework Underlying Typological Observation

The method is organized through a set of Macro-Groups that structure the observation indicators and allow a multiscale reading of the relationships among architecture, settlement, and landscape. Specifically, MG-01 addresses the landscape and settlement structure, including the agrarian grid, infrastructural axes, and the spatial organization of rural nuclei. MG-02 examines the constitutive features of the architectural organism, identifying typological constants, construction techniques, and material characteristics [22]. MG-03 analyses the integration of the building within the landscape system, reconstructing the interactions among the architectural unit, the productive structure, and the environmental framework [23].

In the case of the northern area of Sabaudia, the research adopts these analytical tools as a validated methodological basis, with the aim of verifying their transferability and extending their application to a reclamation context of broader reclamation scale. However, the territorial complexity of Sabaudia required an additional analytical dimension capable of capturing the planning logics embedded in the ONC system.

For this purpose, an additional Macro-Group of investigation is introduced. MG-04 focuses on relationships between rural planning framework and Settlement Type, which constitutes the innovative element of the present study. This fourth Macro-Group deepens the analysis of the relationship between the systematic reiteration of the settlement models developed by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti and the construction of the Pontine Landscape as the outcome of a planning process. MG-04 therefore bridges the gap between architectural observation and territorial interpretation, enabling a reading of rural settlements as components of a deliberate spatial strategy.

The objective is to interpret the repetition of farm units, the hierarchical organization of rural nuclei, and the infrastructural network of the reclamation as operative components of an integrated spatial project at the rural scale, which is capable of translating the productive, social, and environmental logics of the Pontine agrarian Landscape into spatial form.

3.2. Definition of the Qualifying and Characterizing Elements of the Topic

Without reiterating the selection of reference literature already discussed in previous investigations [1], it is useful to recall its systematization, which continues to provide a valid and consolidated framework for the typological and landscape-based analysis of rural architecture.

The main results of that review are summarized in Table 2, which reproduces the taxonomy of the qualifying criteria developed in that context and organized into the three investigative Macro-Groups (MG-01, MG-02, MG-03).

Table 2.

Synthetic classification of the characterizing elements of the topic derived from scientific literature. © Authors, 2025.

The analytical framework was expanded through the introduction of a fourth category, MG-04: Relationships between Territorial Planning and Settlement Type, which constitutes the principal methodological innovation of this study. This category deepens the analysis of the relationship between the replication of ONC settlement models and the construction of the Pontine landscape as the outcome of a coherent process of rural planning framework, in line with the relevant literature.

This extension was necessary to capture the multi-scalar coherence of the ONC system, particularly its capacity to translate productive, environmental, and social logics into spatial form. The indicators associated with MG-04 allow the regularity of farm units, the hierarchy of rural nuclei, and the reclamation infrastructure to be interpreted as integrated components of a planned spatial system, in which architectural, agrarian, and territorial scales converge within a unified design logic. In this perspective, MG-04 reinforces the methodological structure of the research, broadens its interpretative scope, and offers new insights into the processes underlying the construction of the Pontine agrarian landscape.

The method is thus re-proposed as a replicative experiment aimed at verifying the stability of the results already obtained in the Roman case and demonstrating, in a comparative perspective, how typological reiteration produces effects comparable to a form of spatial planning. This methodological continuity ensures the coherence of the research process, from the theoretical framework of the landscape to its morphological representation.

3.3. Classification of Evaluation Indicators and Definition of the Investigative Method: Typological Observation Sheets

The typological observation sheet previously tested in the “Capo Due Rami” case study is reused here as the operational tool for verifying the transferability of the method. Its updated structure allows the systematic and comparable representation of the collected data, drawing on analytical models already validated in similar Italian and international research (Table 2).

The observation sheets were revised to incorporate an expanded set of analytical indicators consistent with the new methodological framework and the introduction of MG-04, which integrates variables relating settlement type and territorial planning. In this configuration, the sheets operate as a multi-scalar matrix that connects architectural evidence to broader territorial dynamics. In this logic, the sheets function became a tool for synthesizing and validating the method, enabling a multiscale reading of the relationships among architecture, landscape, and territorial organization. The indicators employed are summarized in Table 3, which illustrates their interpretative function and the criteria for their application within the analytical model.

Table 3.

Classification of indicators derived for the evaluation sheets applied to the typological analysis. © Authors, 2025.

The methodological expansion responds to the need to verify the role played by the repetition of ONC models and by the agrarian structure in shaping the Pontine landscape as the product of a rural planning process. From this perspective, this method adopts the landscape as an interpretative key, understood as the dynamic synthesis of the relationships among rural architecture, reclamation infrastructures, and agrarian organization.

While the indicators associated with MG-01, MG-02, and MG-03 are directly applied in the evaluation sheets, those of MG-04 are addressed at a theoretical level, as they pertain to the broader domain of rural planning. Their conceptual role nonetheless remains essential for interpreting the ONC system as an integrated planning device. The method therefore combines analytical and interpretative dimensions, allowing verification of the thesis that the repetition of ONC settlement models—together with the reclamation infrastructures—operates as a planning device influencing the form and identity of the Pontine agrarian landscape. This framework informs the applied analysis presented in the following section.

4. Materials and Methods

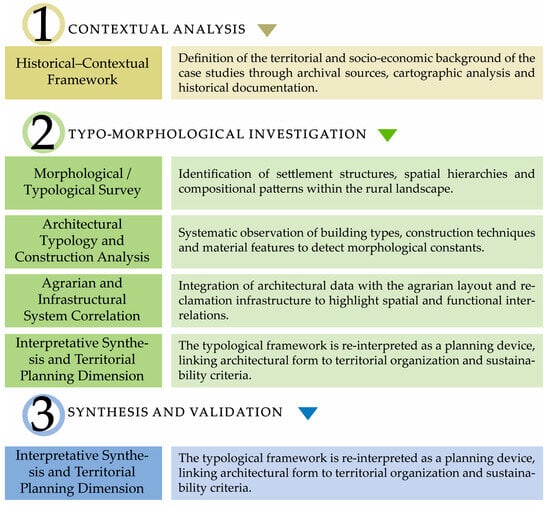

In continuity with the theoretical and methodological framework outlined in Section 3, this research, by applying the typological analysis model previously tested in the “Capo Due Rami” case study, identifies the Agro Pontino as an ideal context in which to assess the transferability of the methodological model and to deepen the analysis of the relationships between rural architecture and the agrarian landscape system. The investigation is thus configured as a controlled methodological replication aimed at testing the method’s ability to capture, within an agrarian environment of broader territorial scale, the multiscale relationships among building type, agrarian structure, and landscape configuration. This section therefore illustrates the operational phases of the method, organized in the collection and systematization of data, the definition of typological–morphological indicators, and the preparation of the observation sheets. This structure, summarized in Figure 2, represents the analytical process carried out in the northern area of Sabaudia, where the methodological model is tested from a comparative perspective.

Figure 2.

Methodological framework applied in the investigation. © Authors, 2025.

4.1. Presentation of the Case Study

As indicated in Section 2, the case study selected for typological observation and methodological experimentation corresponds to the northern rural area of Sabaudia, located within the Pontine reclamation territory in the southern part of the Lazio Region, not far from Rome (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Location of the northern rural area of Sabaudia within the Pontine reclamation territory, Lazio Region, Italy. © Authors, 2025.

This territorial area, organized according to the agrarian system developed by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC), constitutes one of the most significant examples of twentieth-century agrarian planning and represents an ideal context in which to verify the transferability and evolution of the typological analysis method previously tested in the “Capo Due Rami” case study. The selection of this area also assumes methodological and historical continuity: the vernacular architecture previously analyzed in the aforementioned Roman district can be interpreted, in fact, as a direct evolution of the architectural and settlement models originally tested by the ONC in the Sabaudia area.

The Pontine case therefore constitutes the original matrix of a rural language whose diffusion and subsequent transformation progressively contributed to defining the morphology of the landscape of central Italy.

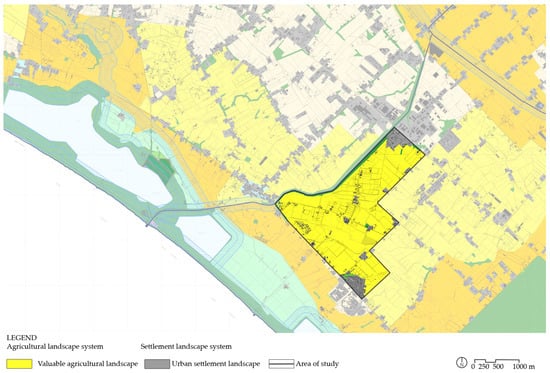

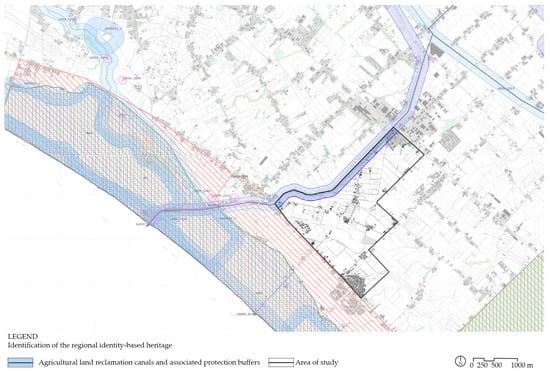

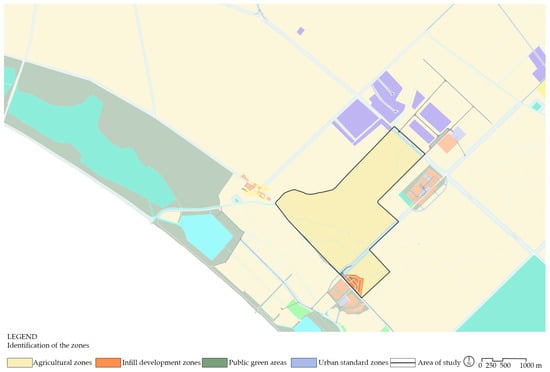

It should be noted that the area under examination is particularly representative of the historical and environmental specificities of the Pontine territory, as it falls within the zone classified as an “agrarian landscape of significant value” and is partially subject to protection under Article 36 of the current Technical Implementation Rules of the Regional Landscape Territorial Plan (PTPR), due to the presence of watercourses safeguarded by regional legislation (Figure 4 and Figure 5). This planning instrument, the most recent regulatory framework approved by the Lazio Region in implementation of Legislative Decree 42/2004—the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape referred to in the introduction—constitutes the regulatory reference framework that defines, from the outset, the concept of landscape adopted in the present research.

Figure 4.

Perimeter of the northern area of Sabaudia within the Regional Landscape Territorial Plan (PTPR). Extract from “Map A”. Modified by the authors. © Authors, 2025. Original documentation available at: https://geoportale.regione.lazio.it, last accessed on 16 October 2025.

Figure 5.

Perimeter of the northern area of Sabaudia within the Regional Landscape Territorial Plan (PTPR). Extract from “Map B”. Modified by the authors. © Authors, 2025. Original documentation available at: https://geoportale.regione.lazio.it, last accessed on 16 October 2025.

From an urban planning perspective, the study area falls, according to the current General Regulatory Plan (PRG) of the Municipality of Latina, within the agricultural zone located north of Sabaudia. This area, already characterized by the widespread presence of farmhouses built by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti and by the historical reclamation infrastructures, is classified as a basic agricultural area, although it lies in proximity to sectors designated for urban standards and to zones identified as equipped public green areas (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Piano Regolatore Generale of the Municipality of Latina. Modified by the authors. © Authors, 2025. The original documentation is available at: https://www.urbismap.com/piano/piano-regolatore-generale-di-latina, Last accessed on 16 October 2025.

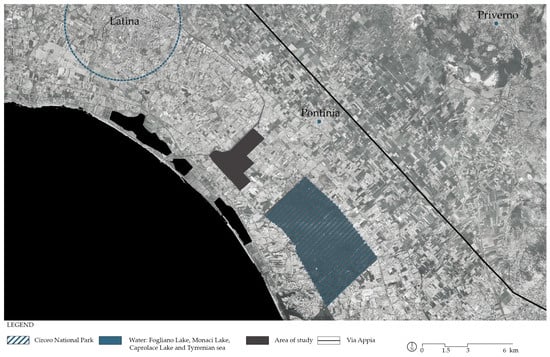

The specificity of the Sabaudia context becomes even clearer when the study area is interpreted within the wider environmental framework that characterizes this sector of the Pontine plain. As shown in Figure 7, the northern fringe of Sabaudia lies within a uniquely stratified landscape system shaped by the proximity of the Circeo National Park, the coastal waterfront, and the pair of coastal lakes that organize the ecological and perceptual setting.

Figure 7.

Sabaudia’s environmental context: park, lakes, waterfront, and rural fringe. © Authors, 2025.

The farmhouses examined in this study occupy the transitional belt between these highly sensitive natural areas and the anthropic territorial systems associated with the inland municipal settlements. This position generates a hybrid territorial identity in which agricultural production, ecological corridors, and settlement infrastructures coexist within a tightly interdependent system. Such environmental complexity not only shapes the morphological layout of the plots and the alignment of rural roads but also influences the spatial logic of the ONC settlement model, whose architectural and agrarian components had to respond to the constraints and opportunities of this distinctive landscape mosaic.

It is therefore a privileged territorial condition that places the area in direct dialogue between “city and countryside” [36], conferring upon it a peri-urban character that extends beyond its specific landscape classification. The current agricultural designation recognizes and preserves the permanence of the original agrarian layout and the testimonial value of rural architectures, reinforcing the productive vocation of the area and safeguarding its historical settlement structure [37] as an integral component of the Pontine Landscape. In coherence with the definition of landscape adopted in the present study—understood as the outcome of the interaction between natural and human factors and as an expression of cultural identity—the northern area of Sabaudia exemplifies the unity of meaning between the natural environment and the built fabric.

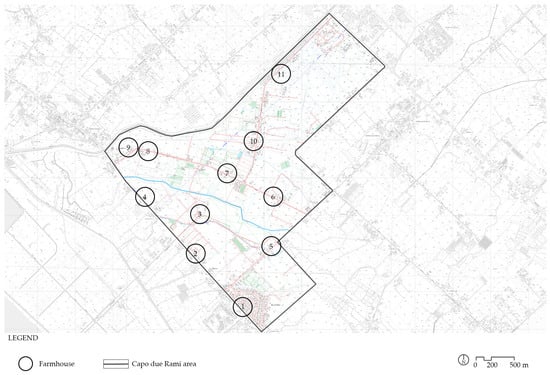

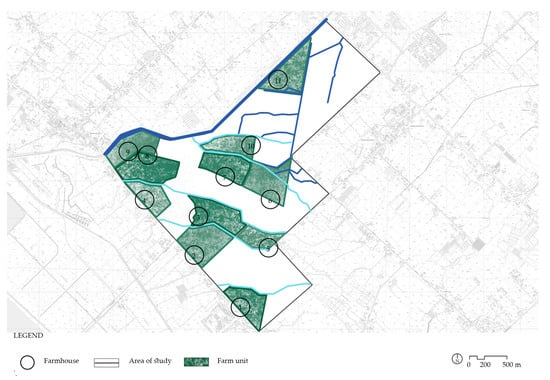

The historical agrarian grid, still clearly legible, retains eleven farmhouses of the Opera Nazionale Combattenti distributed along the main road axis and aligned with the directions of the reclamation canals (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Identification of the eleven ONC farmhouses still present in the northern rural area of Sabaudia, within the reference perimeter of the study. © Authors, 2025.

The hydraulic network, the flat morphology, and the vegetational features are integrated with the settlement layout, generating a coherent environmental and territorial system in which the productive dimension merges with the aesthetic and perceptual one, re-establishing the full continuity between rural architecture and the agrarian landscape system.

The value of this area lies in its dual nature: on one hand, the ecological and environmental dimension, which reflects the physical and climatic peculiarities of the Pontine plain; on the other, the historical and anthropic dimension, which bears witness to the long process of agrarian transformation and territorial organization achieved through reclamation works. In this sense, the landscape of Sabaudia can be interpreted as an authentic product of civilization, in which the construction of the agricultural space takes shape simultaneously as a technical, cultural, and identity-driven act. It therefore assumes an emblematic representative value of the materialization of the theoretical principles defining the epistemic framework on landscape outlined in Section 2 of this work.

4.2. Historical, Typological, and Landscape Analyses: The Characterizing Elements of the Observation Sheets

The analysis of the eleven ONC farmhouses located within the study area requires the integrated assessment of multiple aspects, following a multidisciplinary approach consistent with the complex nature of the topic, as outlined in the introductory section. In continuity with the previously described method, the investigation is based on materials derived from historical, typological, and landscape analyses, organized within the reference Macro-Groups (Table 2 and Table 3).

The objective is to understand the territorial transformations and the ways in which they are reflected in the architectural configuration of the farmhouses, understood as expressions of the unified process of reclamation and rural planning. This approach makes it possible to refine and update the instruments of typological observation, verifying their transferability and practical validity within the context of the Pontine Landscape.

4.2.1. Historical and Historical-Documentary Analyses

The northern rural area of the Sabaudia territory represents one of the most coherent testimonies of the transformation process of the Pontine Landscape. The current landscape configuration results from a long sequence of reclamation and agrarian reorganization interventions that, between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, progressively redefined the relationship between the natural environment and the productive infrastructure.

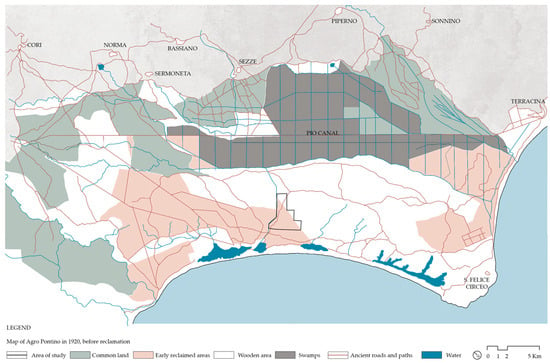

The first phase of systematic organization of the Pontine territory dates back to the reclamation works undertaken under Pope Pius VI (1777–1794), promoted as part of a broader policy for the rehabilitation of the Pontine marshes and entrusted to engineers Gaetano Rappini and Antonio Galanti. The main works involved the construction of the Pio VI Canal, traced along the Via Appia, and the creation of a network of transversal drainage channels directed toward the coastal lakes and the sea, as illustrated in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9.

Historical map of the Agro Pontino prior to the reclamation works of the 1920s, highlighting the marsh areas and the early hydraulic layouts that were later transformed. Authors’ elaboration based on historical cartographic sources. © Authors, 2025.

This system, conceived primarily for hydraulic and sanitary purposes, represented the first systematic attempt to control the water regime and constituted the morphological basis for subsequent modern reclamation operations [38]. Despite technical limitations—mainly due to the absence of pumping stations and the lack of stable agrarian management—the pontifical reclamation introduced a principle of geometric rationalization of the territory: the landscape was interpreted as a measurable whole, organized by regular lines and by a hydrographic structure capable of ordering space. As stated in the Circeo National Park Plan [39], this canal system formed the foundation for the reclamation interventions of the 1920s and 1930s, since the layouts of the Pio Line and the “migliare” divisions were reused as references for the later comprehensive reclamation of the twentieth century. The “migliare” divisions—regular land partitions spaced roughly one Roman mile apart—served as reference lines for the later reclamation grid.

The comprehensive reclamation, launched in 1923 under the direction of Arrigo Serpieri, marked a radical transformation of the Pontine plain, combining hydraulic rehabilitation with agrarian colonization and settlement planning. The intervention, carried out by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC), produced a unified territorial system based on an orthogonal grid of rectangular farms, delimited by canals and connected by a dense network of rural roads, as shown in Figure 10 below.

Figure 10.

Map of the Agro Pontino in 1940, following the comprehensive reclamation works, highlighting the new agrarian grid, the hydraulic network, and the main rural nuclei built by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti. Authors’ elaboration based on historical cartographic sources. © Authors, 2025.

The works carried out were of an impressive scale: over 9800 km of drainage channels, 1960 km of roads, and more than 2000 farmhouses transformed the Agro Pontino into a productive and inhabited territory [40,41]. This territorial structure, organized according to the “Migliare” system—a network of canals and roads perpendicular to the Pio Line and spaced approximately one mile apart—reflected a principle of functional rationality and land control that endowed the plain with a coherent and measurable morphological configuration [42].

The architectural and agrarian planning undertaken by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC) found one of its most accomplished expressions in the foundation of Sabaudia (1933–1934), designed by Luigi Piccinato, Gino Cancellotti, Eugenio Montuori, and Alfredo Scalpelli. The urban plan was based on the triad “farm–village–city”, expressing the intention to construct a stable social and productive structure rooted in a hierarchical settlement system, where the farms represented the productive units, the villages served as service centers, and the city functioned as the administrative and symbolic core of the territory [43].

The comprehensive reclamation was conceived as an extensive territorial transformation process that combined hydraulic works with land reorganization, the construction of rural infrastructures, and the creation of new rural nuclei, as established by Royal Decree No. 215 of 13 February 1933 on the new rules for comprehensive reclamation [44]. In the northern area of Sabaudia, the construction of the reclamation system reflects the intention to integrate urban planning with agrarian organization. The “Città di Fondazione” of the Pontine region embody the aim of building a unified landscape in which the relationship between environment and settlement is part of an overarching ordering vision [45]. In Sabaudia, this vision materializes in the correspondence between the regularity of the agrarian grid and the urban structure, organized along two main axes—the cardo and decumanus—which define the overall territorial layout [46].

The intervention of the ONC helped shape an integrated productive system, where the network of canals, inter-farm roads, and rural buildings defined a morphologically and functionally coherent landscape. Archival sources report that more than two hundred projects were developed for the Pontine area alone, concerning reclamation, farm structuring, and the construction of urban and rural centers, demonstrating the scale and scope of the intervention [47]. The diffusion of rural farmhouses, a typical element of the new agrarian structure, fits within this logic of territorial rationalization. As Cazzola observes, the constructions built following the reclamation laws “tended to assume structural features closer to urban typologies, producing buildings that balanced the needs of agricultural activity with hygienic standards” [48]. The standardization of building types and the placement of farmhouses at the center of the plots thus constituted not only a functional device but also a means of representing the modern landscape.

Within this balance between architecture, hydraulic infrastructure, and agriculture, the identity of the Sabaudia territory is defined: a planned landscape expressing the technical and symbolic rationality of comprehensive reclamation, where city and countryside merge into a single design. The traces of territorial transformations generated by the reclamation interventions are clearly visible in the 1954 maps of the Istituto Geografico Militare - Italian Military Geographic Institute (IGM), which document an ongoing process of agrarian planning. The evolution of the territory was analyzed through a multitemporal comparative reading of historical aerial photographs of the northern area of Sabaudia, referring to the years 1954, 1988, 1994, 2000, 2006, and 2012. The comparison of these images made it possible to precisely identify the persistence of the original agrarian pattern, the stability of the reclamation network, and the marginal transformations of the agricultural fabric, highlighting the remarkable morphological coherence of the landscape over time. The results of this comparison are illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the northern rural area of Sabaudia through the multitemporal comparison of historical aerial photographs (1954, 1988, 1994, 2000, 2006, and 2012). The images highlight the persistence of the original agrarian layout, the reclamation hydraulic network, and the progressive transformations of the agricultural fabric. Authors’ elaboration based on aerophotogrammetric data. © Authors, 2025. Sources: G.A.I. Aerial Survey 1954–https://geoportale.regione.lazio.it/layers/1954_VOLO_GAI_COG:geonode:1954_VOLO_GAI_COG (accessed on 15 October 2025); Orthophotos 1988–2012–http://www.pcn.minambiente.it/viewer/. Last accessed: 16 October 2025.

Although no photographic documentation exists from the early phases of the reclamation, the combination of cartographic reconstructions from the Istituto Geografico Militare, historical aerial photographs, and archival data from museums and specialized literature has made it possible to reliably reconstruct and systematize the different phases of the territorial transformation process. The integration between architecture, land organization, and hydraulic infrastructure was, in fact, a determining factor in shaping the Pontine agrarian landscape, whose subsequent transformations—illustrated in Figure 12—represent a coherent, progressive, and still clearly legible evolution over time.

Figure 12.

Representative images of the current rural landscape layout, as shaped by the reclamation and land parceling operations carried out since the 20th century. © Authors, 2025.

It is precisely the cartographic and documentary sources that make it possible to define with precision the period of construction of the farmhouses built by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti, situating it within the chronological interval identified through the analyzed evidence. It should be specified that the analytical approach adopted—although based on the integration of historical data and updated cartographic materials—did not include direct cadastral verification, deemed non-essential to the objectives of typological observation, though still useful for the geographical localization of the buildings [49], due to the limited reliability of national registries for earlier periods.

As highlighted throughout this research, the territorial transformations documented in cartographic sources have had a decisive influence on the formation of the building fabric and the broader settlement structure, contributing over time to the definition of a new landscape identity. The area, progressively consolidated as an organized agricultural zone, abandoned its previous productive functions related to the saltworks, becoming a full expression of the reclamation system.

This vision anticipates a coherent and meaningful mode of development [50], which finds full confirmation in the case of Sabaudia: the architectural typology of the ONC farmhouses emerges not only as a functional response to productive needs but also as a direct expression of a planning logic that has gradually shaped the form and identity of the Pontine agrarian landscape.

4.2.2. The Farm Unit as Intermediate Landscape Scale

Interpreting the Pontine rural landscape requires the introduction of an intermediate analytical scale, positioned between the territorial framework of the reclamation grid and the architectural features of the ONC farmhouse. This scale corresponds to the farm unit, which is understood as the spatial and functional organism that integrates the rural dwelling, its pertinent plot, and the hydraulic and road infrastructures that structure the reclaimed territory. As shown in Figure 13, the farmhouse is never an isolated architectural element but the nodal component of a wider system in which built structures, agricultural surfaces, and infrastructural corridors converge to form coherent spatial sequences.

Figure 13.

Intermediate-scale view of the farm unit: farmhouse, pertinent plot, and infrastructural connections. © Authors, 2025.

The new cartographic analysis clarifies the precise allocation of each farmhouse within its assigned plot, showing that the morphology of the pertinent areas derives directly from the geometry and orientation of the irrigation canals. The elongated configuration of the fields—shaped by the linear hydraulic system—typically places the dwelling along the long side of the lot, where it benefits from efficient access via the tangential rural road and direct proximity to the canal. This arrangement ensures both accessibility and hydro-agricultural efficiency, while allowing the remaining surface—although often fragmented by the drainage network—to be largely dedicated to cultivation.

The interpretative value of this intermediate scale is further illustrated in Figure 14, which offers a taxonomic synthesis of the farm unit as the superposition of distinct yet interdependent layers: the farmhouse, the pertinent plot, the access road, and the irrigation canal.

Figure 14.

Taxonomic diagram of the intermediate-scale multi-scalar relations between farmhouse, pertinent plot, access road, and reclamation canals. © Authors, 2025.

The combination of these elements forms a coherent spatial device that clarifies the operational logic of the ONC system and makes explicit the functional interaction between built and unbuilt components. The farm unit thus emerges as the morphological and organizational matrix through which the architectural type acquires meaning within the landscape.

This configuration reflects not only spatial and functional criteria but also the socio-economic program promoted by the ONC. The rural dwelling embodies a model of productive self-sufficiency and social organization that shaped the daily life of settler families, expressing the “honest” and “truthful” architecture praised by Pagano [4]. In this framework, architectural form derives from necessity, rationality, and the ethical dimension of rural labor, while the landscape functions as the operational field in which these values materialize.

Integrating this intermediate scale within the typological analysis is therefore essential for interpreting the ONC farmhouse not simply as a building type but as a hybrid architectural–agrarian construct embedded within the territorial landscape of the Pontine plain.

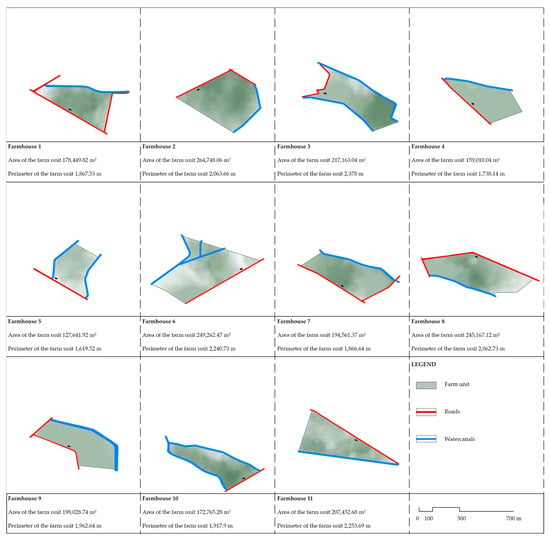

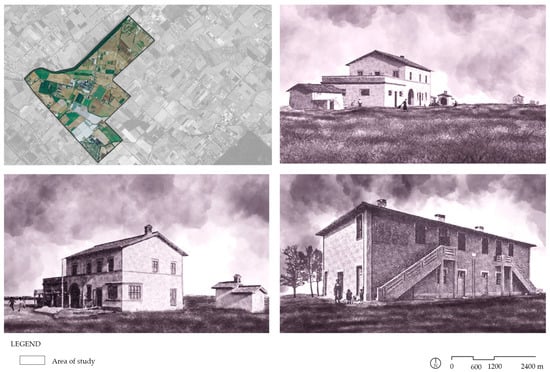

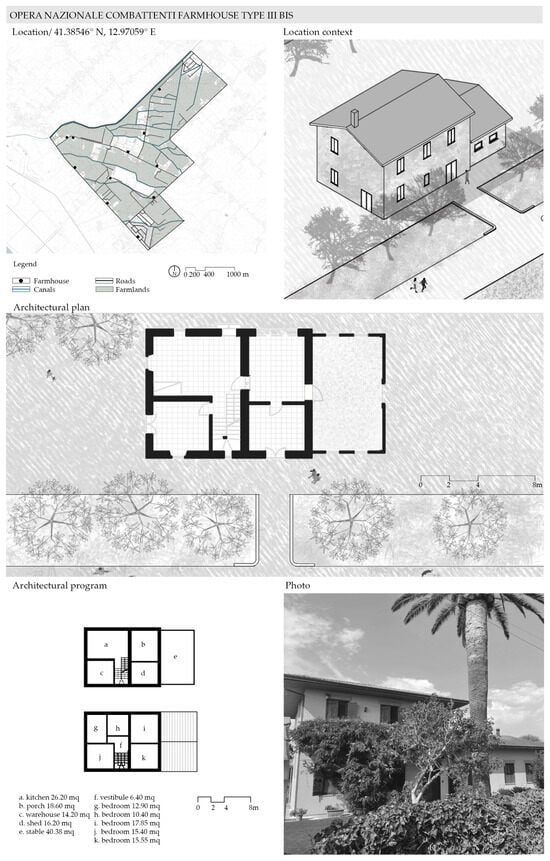

4.2.3. Architectural Typology of the ONC Farmhouse

Regarding the presence of rural buildings within the area, their typological configuration clearly reflects the construction and distribution principles developed by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC) during the phases of reclamation and agrarian colonization. Although some variations can be attributed to local specificities and subsequent changes in use, the ONC farmhouses in the northern area of Sabaudia exhibit a clear morphological and settlement coherence, corresponding to a standardized and functional building model common to the entire Pontine rural system, whose formal outcome is summarized in Figure 15 below.

Figure 15.

Examples and graphic representations of the farmhouses built by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC) in the Ostia area, near Sabaudia. Images reworked by the authors, originally published in the almanacs of “La Conquista della Terra—Rassegna dell’Opera Nazionale per i Combattenti”, July 1930 issue. © Authors, 2025.

The investigation, carried out in the archives of ARSIAL (Regional Agency for the Development and Innovation of Agriculture in Lazio), which preserves the historical documentation of the Opera Nazionale Combattenti (ONC), was based on the analysis of the original plans concerning the distribution of agricultural plots and the construction of the farmhouses. The study began with the first buildings erected in the Sabaudia area—including farmhouse “No. 3”—and was later extended to the territory of Latina, where the agrarian system and settlement network maintain substantial continuity with the original model.

The archival survey made it possible to establish correspondence between design data and actual configurations, confirming the coherence and repetitiveness of the building type across the territory. In order to highlight the constants and variations within the theme, it should be noted that the analyzed building type—attributable to the farmhouses built by the ONC due to their constructive affinity and authorial replication of the archetypal model shown in Figure 16—was originally characterized by a spatial and functional layout closely connected to the performance and practical needs of rural architecture of the time [51].

Figure 16.

Representation of the rural dwelling typology built in the area. Archetypal Model. © Authors, 2025.

The planimetric configuration reveals a clear distinction between productive and residential areas, consistent with the rational logic characteristic of agrarian reclamation planning. The ground floor concentrates the spaces dedicated to agricultural activities—stables, storage rooms, and service areas—often opening onto a covered portico used as a workspace and shelter. Adjacent to this, the kitchen with its fireplace serves as the domestic core and gathering point for the farming family.

The upper floor is reserved for living quarters, organized according to linear or symmetrical distribution schemes designed to accommodate large family units or seasonal workers. This functional hierarchy of spaces, combined with structural simplicity and the use of local materials (plastered brick masonry, pitched roofs, wooden floors), gives the building type strong morphological coherence and high adaptability to the agrarian context [52].

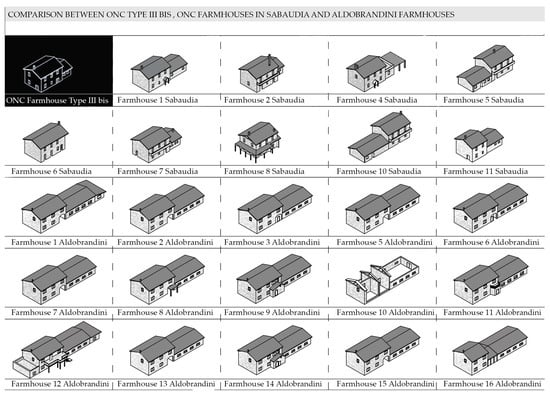

These characteristics show that the ONC farmhouse typology constitutes a rational and replicable model capable of meeting both productive and residential needs while shaping the architectural identity of the Pontine reclamation system. When viewed through the intermediate landscape scale introduced in this study, the typological framework reveals a wide range of variations generated by the combined influence of infrastructural layouts, plot morphology, and environmental constraints. As illustrated in Figure 17, the comparative analysis between the canonical ONC farmhouse, the morphotype identified in the Capo Due Rami study [01], and the variants documented in the present research demonstrates how differences in access routes, the positioning of the dwelling within the plot, and the geometric configuration of the pertinent areas—often conditioned by the hydrological and agrarian structure of the territory—produce distinct yet internally coherent architectural outcomes.

Figure 17.

Comparative architectural typology of ONC Type 3 (ARSIAL), the Capo Due Rami morphotype, and the Sabaudia variants. © Authors, 2025.

In this regard, it is important to note that all the examined configurations derive, to a large extent, from the ONC archetype classified as “Type 3” in the archival taxonomy established by ARSIAL. Its widespread presence across the Pontine territory attests to its adaptability to varying environmental and infrastructural conditions. Figure 17 synthesizes this multi-scalar reading by illustrating the typological correspondences and divergences across the three contexts, confirming that the ONC model functions as a flexible generative matrix rather than a rigid architectural schema.

4.2.4. From Reclamation to Planning: Relationships Between Territorial Structure and Building Type

The analysis has shown that the ONC farmhouses were effectively built within a regular land-allotment system, in which each agricultural plot was defined not only according to its cultivable surface but also in relation to its spatial connection with the reclamation canals and the rural road network (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Identification of the area with the numerical listing of the casali addressed in the typological observation model. The numbering identifies the farmhouses analyzed. © Authors, 2025.

The first farmhouses built by the Opera Nazionale Combattenti, located near waterways and drainage canals according to a settlement logic integrated with the hydraulic infrastructure, established a structural relationship between architecture, the reclamation network, and the agrarian grid. The systematic reiteration of this relationship progressively acquired a planning value, becoming an implicit form of territorial planning and an identity matrix of the Pontine agrarian landscape [53].

5. Results and Discussion

The analytical method tested in Section 4, based on the systematic correlation of heterogeneous data organized within a unified framework and represented through typological observation sheets, has produced the results illustrated here. These findings are presented in relation to the preliminary hypotheses and research questions formulated in the introductory section, through an interpretative analysis of the case study articulated into three main domains—historical, typological, and landscape. The methodological recursiveness thus operates both as a verification tool and as an interpretative key for assessing the typological capacity to generate recognizable planning effects within the Pontine agrarian landscape.

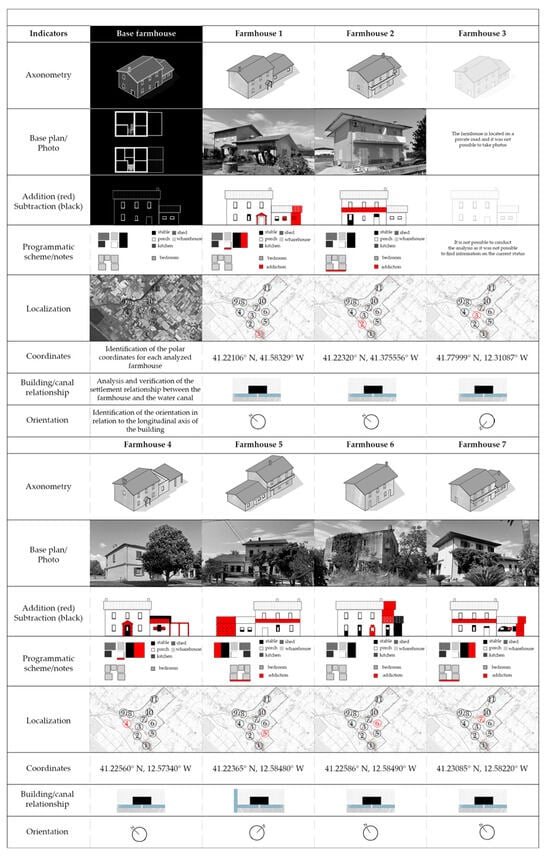

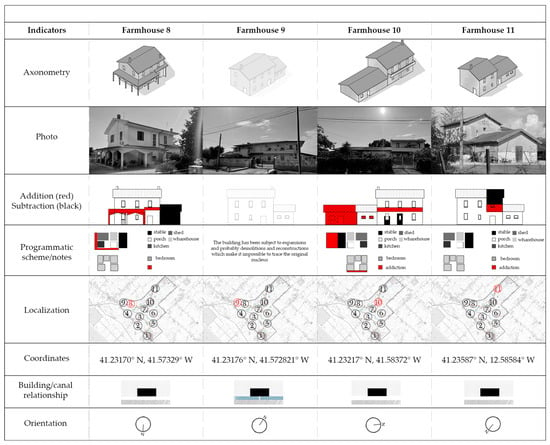

5.1. Application and Replication of the Experimental Model of Typological Analysis

As previously noted, the design of the observation sheets is based on the need to coherently integrate the evaluation indicators identified in Table 2, derived from the scientific literature analyzed in Section 3. The structure of the sheets, replicated and adapted from the previously developed experimental model, has been recalibrated to verify its transferability to the territorial setting of Sabaudia. In their updated version, they retain the original framework but include new indicators related to the relationships between settlement type and territorial planning (MG-04), in response to the specific objectives of this research. Although the architectural typology of the ONC farmhouse is a fundamental component of the settlement system, the building cannot be interpreted independently of the agricultural plot to which it belongs. The ONC design explicitly conceived the farm unit as an integrated spatial, functional, and economic system composed of the house, the service courtyard, the cultivated fields, and the connections to drainage canals and the road network. This intermediate scale—situated between the territorial layout and the architectural organism—is essential for understanding the landscape logic of the reclamation: the farmhouse functions as a node within a wider productive and infrastructural system rather than as an isolated architectural entity.

The adopted approach thus broadens the methodological debate on the typological interpretation of rural architecture, grounding it in historically, cartographically, and morphologically contextualized data. The observation sheets (Figure 19 and Figure 20) systematically describe the elements identified through the reference literature and archival materials, paying particular attention to geographic, morphological, and settlement aspects, as well as to the relationships between rural architecture and the environment transformed by the reclamation processes that shaped the territory of Sabaudia.

Figure 19.

Representation of the rural dwelling typology built by the ONC, corresponding to building types numbered 1 to 7. © Authors, 2025.

Figure 20.

Representation of the rural dwelling typology built by the ONC, corresponding to building types numbered 8 to 11. © Authors, 2025.

5.2. Rural Architecture and the Construction of the Agrarian Landscape System

Rural architecture, which characterizes the Italian agrarian environment, represents a form of construction that is intrinsically connected to the natural and anthropic context in which it developed. It is the result of an evolutionary process in which productive needs, local resources, and environmental conditions converge to define a unified architectural language founded on functionality and adaptation to the territory [54]. This balance is expressed in the ability of rural buildings to integrate residential and productive spaces within a coherent system, where local materials, climatically favorable orientations, and distributive solutions respond to criteria of efficiency and environmental compatibility. In this sense, rural architecture does not possess a purely aesthetic value but constitutes a structural component of the territory, contributing to the morphological and identity definition of the landscape [55].

Its sustainability lies in vernacular constructive knowledge, which is capable of translating environmental conditions into architectural rules and ensuring durability, economy of means, and technical coherence. The repetition of compositional and constructive schemes—typical of rural production and of the Opera Nazionale Combattenti farmhouses—does not imply uniformity but rather a rationality applied to territorial planning: a way of landscape construction based on the reiteration of the building type and the agrarian parcel. This process confirms the interpretative hypothesis that typology, beyond responding to functional needs, acts as a device for territorial organization capable of generating planning effects recognizable over time [56].

In conclusion, rural architecture emerges as a true territorial device in which constructive tradition, agrarian economy, and landscape planning intertwine. The analysis shows that the original agrarian structure continues to shape the territory, preserving the legibility of the relationship between agricultural use, hydrographic network, and settlement—a tangible sign of a landscape built through the rationality of type and the continuity of rural inhabitation.

5.3. Typological Variations Across Territorial and Intermediate Scales

The comparative phase constitutes the concluding stage of the experimental validation, allowing the results obtained in the Pontine area to be related to those from the original “Capo Due Rami” case study. The comparison demonstrates that methodological and typological repetition conceptually converge: the former consolidates the method, while the latter reveals its planning substance, generating a circular coherence between the analytical process and the observed phenomenon.

In both experiences, the methodological matrix based on Macro-Groups MG-01, MG-02, and MG-03 proved effective in identifying morphological and typological constants while also recognizing the environmental and constructive specificities characterizing different agrarian landscapes. The main element of divergence lies in the scale of the transformation process: whereas in the Roman case the relationship between buildings and the hydraulic network represents an embryonic experimentation, the Pontine reclamation constitutes its accomplished and planned outcome. The replication of building types and their systematic distribution throughout the territory testify to the maturation of a design awareness in which typological repetition becomes the ordering principle of the landscape [57].

The landscape–cartographic analysis shows that each farmhouse is positioned according to a clear logic of functional integration with its assigned agricultural plot and the reclamation infrastructures. The alignment of the houses along canals and roads ensured access, irrigation, drainage, and mobility within the productive system. The agricultural plot was not conceived as a neutral background but as a designed extension of the house, organized through a hierarchy of cultivated areas, service zones, and movement corridors. This built–unbuilt integration—house, plot, canal, and road—defines the operational identity of the farm unit and is key to interpreting the Pontine agrarian landscape as a multi-scalar system.

The relationship between the house and the drainage canal is particularly significant. The canal enabled the productive viability of the plot, regulated water levels, and supported irrigation practices. At the same time, it determined the position and orientation of the farmhouse, often placed at the field’s edge with service façades facing the canal to facilitate access to water and maintenance. This reciprocal interaction demonstrates that the architectural typology is inseparable from the hydrological structure of the landscape.

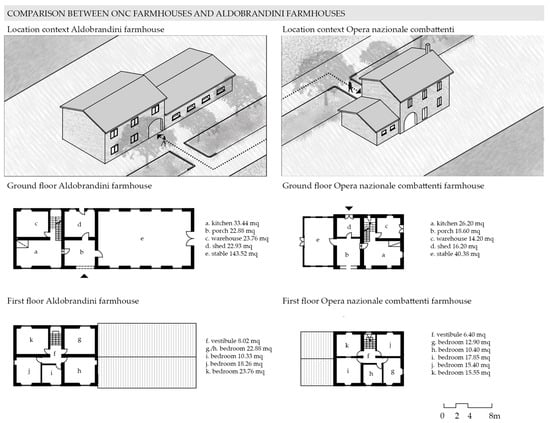

Although the architectural differences among the examined farmhouses are minimal—with the Aldobrandini morphotype identified in the Capo Due Rami study and the examples analyzed in Sabaudia all deriving from the ONC Type 3 archetype—the comparative analysis shows that their variations arise primarily at the territorial and intermediate scales, rather than at the architectural one (Figure 21).

Figure 21.

Comparative architectural typologies of the Capo Due Rami morphotype and the Sabaudia farmhouse variants. © Authors, 2025.

The most significant divergences concern the orientation and configuration of the access system, the positioning of the dwelling within the agricultural plot, and the geometric articulation of the pertinent areas. These variations depend on the specific land morphology, the hierarchy of irrigation canals, and the parcel structure imposed by the reclamation process. Together, these factors generate distinct spatial arrangements that appear as subtle yet coherent typological variants at the architectural scale.

This evidence confirms that a multi-scalar analytical approach—progressing from the territorial framework, through the intermediate farm-unit scale, and finally to the architectural organism—is essential for interpreting the genesis and meaning of such variants. In these rural contexts, architectural form cannot be separated from the agrarian and infrastructural logics that determine its placement, orientation, and functional relations. The typological differences observed between the Aldobrandini farmhouse and the Sabaudia examples therefore emerge as spatial expressions of multiple environmental, infrastructural, and socio-productive determinants, reaffirming the necessity of an integrated multiscale methodology for studying ONC rural architecture.

5.4. Typology, Planning Logics, and Landscape Policy Framework

This set of findings reinforces the need to interpret typological variation not as a purely architectural phenomenon but as the outcome of multi-scalar territorial logics, thereby providing the conceptual bridge toward the broader planning perspective formalized through MG-04.

The introduction of Macro-Group MG-04 made it possible to extend this interpretation theoretically, linking the results of typological analysis to the dynamics of territorial planning. This perspective shows how architectural typology, when distributed according to productive and infrastructural logics, acquires a planning significance: the building type becomes a tool for territorial organization capable of generating identity and morphological continuity [58]. Within this framework, the observation sheet—reinterpreted through the lens of MG-04—allows for a multiscale reading of the interrelation among built form, agrarian structure, and reclamation infrastructure, attributing to vernacular architecture the value of both cultural legacy and cognitive device.

The regulatory framework outlined by the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape (Legislative Decree 42/2004) [15] confirms the need for an integrated and multiscale approach to managing rural transformations.

From this perspective, the indicators of morphological coherence, ecological continuity, and perceptual quality derived from the observation sheets can serve as objective parameters for landscape and environmental assessment, guiding design choices towards greater landscape compatibility. In the Italian context, the agrarian landscape system holds not only environmental and productive significance but also a formally recognized cultural value, as defined by the national legislative framework. Within the Pontine reclamation area, the ONC settlement system constitutes a historically stratified territorial artifact in which architectural form, agrarian layout, and reclamation infrastructures converge to shape a coherent cultural landscape.

Acknowledging this dimension reinforces the relevance of the proposed methodological framework for contemporary policies on landscape protection and rural heritage enhancement. The interpretative structure developed in this study thus supports not only morphological and typological analysis but also the identification of cultural values that remain central to current debates on the preservation, regeneration, and adaptive reuse of rural settlements in Italy.

In conclusion, the building typology, understood as the material and identity expression of the landscape, is configured not only as an object of morphological analysis but as a true device of implicit planning. Consistent with this perspective, the study also achieves a secondary yet significant goal: contributing to the description and valorization of vernacular architecture and of the Italian experiences that have, over time, shaped the form and identity of the national agrarian landscape.

This potential extension also allows the typological reflection to be connected to themes of constructive and environmental sustainability. The rural architectures of the Mediterranean basin—built with local materials and passive systems for climatic regulation—are undeniably coherent examples of integration among form, function, and context [59,60,61]. In the reclamation villages, this coherence translates into a sustainable settlement logic founded on productive proximity and the continuity between architecture and landscape, anticipating principles that are now central to the ecological planning of the territory [62].

6. Conclusions

This study confirms the methodological coherence of the proposed approach by applying the typological method to a broader and more complex landscape context. The replication of the experiment in the Pontine area has demonstrated that both the reiteration of the building type and the consistency of the analytical method generate ordering effects at the territorial scale.

The comparative analysis highlights the coherent morphological and distributive features of the ONC settlement system, confirming its relevance for understanding the formation and persistence of the Pontine agrarian landscape. The ONC building morphotype reflects the relationship between productive needs, land management, and settlement form, offering a representative model within Italian rural architecture.

Consistent with the initial hypotheses, the investigation identifies, in the repetition of the ONC model, not merely a typological device but a true instrument of territorial planning. The results obtained, summarized in Table 4, confirm the validity of the experimental method and its transferability to agrarian contexts characterized by analogous historical and landscape dynamics.

Table 4.

Responses to the questions posed at the foundation of the investigation based on the activities conducted. © Authors, 2025.

This research demonstrates that typological repetition, beyond the architectural dimension, constitutes a principle of territorial planning capable of contributing to the material and cultural construction of the agrarian landscape.

The results confirm the robustness of the method and the effectiveness of the observation sheets as tools for interpreting rural architecture and its territorial implications. The successful transfer of the model to the Pontine context demonstrates its potential applicability to other Italian reclamation areas, supporting the development of a systematic and comparable framework for the study of rural settlements. The proposed approach also provides a replicable foundation for landscape-oriented planning strategies, contributing to the interpretation and enhancement of historical agrarian landscapes. Future research may extend this comparative methodology to other rural territories, enabling a broader multidisciplinary exploration of the themes identified in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and M.L.S.; methodology, S.B.; software, S.B. and M.L.S.; validation, S.B., M.L.S., A.I.D.M. and A.M.; formal analysis, S.B. and M.L.S.; investigation, S.B. and M.L.S.; resources, S.B. and M.L.S.; data curation, S.B. and M.L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B. and M.L.S.; writing—review and editing, S.B., M.L.S. and A.I.D.M.; visualization, S.B. and M.L.S.; supervision, S.B., A.I.D.M. and A.M.; project administration, S.B. and A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bigiotti, S.; Santarsiero, M.L.; Del Monaco, A.I.; Marucci, A. A Typological Analysis Method for Rural Dwellings: Architectural Features, Historical Transformations, and Landscape Integration: The Case of “Capo Due Rami”, Italy. Land 2025, 14, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigiotti, S.; Costantino, C.; Santarsiero, M.L.; Marucci, A. A Methodological Approach for Assessing the Interaction Between Rural Landscapes and Built Structures: A Case Study of Winery Architecture in Tuscany, Italy. Land 2025, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, P. What Do We Mean by Sustainable Landscape? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2008, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Guarniero, D. Architettura Rurale Italiana; Quaderni della Triennale, Ed.; Ulrico Hoepli Editore: Milano, Italy, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amia, G. Giuseppe Pagano e l’architettura rurale. Territorio 2013, 66, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, R. Per lo studio dell’abitazione rurale in Italia. Riv. Geogr. Ital. 1926, 33, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, G.; Gambi, L. (Eds.) La Casa Rurale in Italia. In Ricerche sulle Dimore Rurali in Italia; No. 29; Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche; Leo S. Olschki Editore: Firenze, Italy, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giulio, R.; Zaffagnini, T. Case Sparse. Paesaggi Agrari tra Ferrara e Bologna: Strategie per la Valorizzazione e il Riuso del Patrimonio Rurale; FrancoAngeli Editore: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bilò, F. Valori estetici e paesaggio contemporaneo. In Conferenza Nazionale per il Paesaggio. Lavori Preparatori; Cavezzali, D., Palombi, M.R., Eds.; Gangemi Editore: Roma, Italy; pp. 141–144. ISBN 978-88-492-0132-1.

- Donadieu, P. Scienze del Paesaggio. Tra Teorie e Pratiche; Edizioni ETS: Bologna, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-88-4673-7106. [Google Scholar]

- Gkartzios, M.; Gallent, N.; Scott, M. (Eds.) Rural Places and Planning: Stories from the Global Countryside; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregotti, V. La nozione di “contesto”. Casabella 1981, 465, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Gregotti, V. Il Territorio dell’Architettura; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 1966; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A. (Ed.) Il Territorio Bene Comune; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2012; ISBN 978-88-6655-131-7 (print), 978-88-6655-134-8 (online). [Google Scholar]

- Italian Government. Legislative Decree of January 22, 2004, No. 42, Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape; pursuant to Article 10 of Law No. 137 of July 6, 2002; Italian Government: Rome, Italy, 2004.

- Cecchi, R. I Beni Culturali. Testimonianza Materiale di Civiltà; Spirali Edizioni: Milano, Italy, 2006; ISBN 978-88-7770-742-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sereni, E. Storia Del Paesaggio Agrario Italiano, 3rd ed.; Edizioni Laterza: Bari, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-88-581-4074-1. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Government. Legislative Decree of April 3, 2006, No. 152, Environmental Code; Amended by Legislative Decree of January 16, 2008, No. 4; Italian Government: Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Secchi, R. Progetto di paesaggio, progetto evolutivo? In Paesaggio e Ambiente Nelle Trasformazioni Urbane; Aracne editrice Srl: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, S.; Catania, P.; Greco, C.; Ferro, M.V.; Vallone, M.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G. Rural Landscape Transformation and the Adaptive Reuse of Historical Agricultural Constructions in Bagheria (Sicily): A GIS-Based Approach to Territorial Planning and Representation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, C. La grande bonifica della Piana Pontina. L’Acqua—Rivista dell’Associazione Idrotecnica Italiana. Sezione “Opere e Sistemi”. 2016. Available online: https://www.idrotecnicaitaliana.it/lacquaonline/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Masullo-LA-BONIFICA-della-PIANURA-PONTINA.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Trapani, F. Verso La Pianificazione Territoriale Integrata. Il Governo Del Territorio A Confronto Delle Politiche Di Sviluppo Locale; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-568-0463-8. [Google Scholar]

- De Montis, A. Measuring the Performance of Planning: The Conformance of Italian Landscape Planning Practices with the European Landscape Convention. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A.; Ledda, A.; Serra, V.; Noce, M.; Barra, M.; De Montis, S. A Method for Analysing and Planning Rural Built-up Landscapes: The Case of Sardinia, Italy. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, E.; Iaccarino, S. An Historically-Informed Approach to the Conservation of Vernacular Architecture: The Case of the Phlegrean Farmhouses. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 44, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmi, D.H.; Tamimi, S. Traditional Domestic Architecture in the Rural Cultural Landscape of Borobudur, Indonesia. ISVS E-J. 2023, 10, 182–200. [Google Scholar]