Abstract

Spatial heterogeneity of species distributions modulates local interactions and dynamics, playing a key role in the development of diversity and ecosystem functioning during secondary succession. Here, we tested the cycling heterogeneity hypothesis, which predicts fluctuating spatial beta diversity, i.e., alternating periods of high and low heterogeneity during succession, driven by the changes in the abundance of dominant species. We analyzed long-term monitoring data collected annually along 52 m long permanent transects over 15 years in abandoned fields. Recovery of grassland vegetation was fast due to the humus-rich chernozem soil, the rich species pool, and the fast colonization of native grassland species from adjacent natural meadow steppe. Heterogeneity was quantified by spatial beta diversity as the mean pairwise dissimilarity among sampling units. Incidence-based (Jaccard) and abundance-based (Bray–Curtis) indices were used. We found large temporal fluctuations in spatial heterogeneity, with amplitudes reaching 80–100% of the total beta diversity range across the successional gradient. Two major beta diversity peaks were identified: maximum heterogeneity occurred during transitions between successional phases, whereas periods of minimum heterogeneity coincided with the sequential dominance of a few particular species. Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca were the most important species driving heterogeneity. Similar patterns were recorded at two monitoring sites. Changing the sampling unit size computationally, varying the dissimilarity indices, or excluding dominant species had little influence on the results. Using null models, we removed the effects of species richness and abundance and found an increasing degree of spatial dependence as succession progressed. However, the corresponding beta deviations also showed non-linear, fluctuating patterns. Our results support the cycling heterogeneity hypothesis in secondary grassland succession. Increasing understanding of heterogeneity patterns provides new opportunities to optimize the temporal and spatial design of grassland restoration measures.

1. Introduction

Heterogeneity is a fundamental concept in ecology [1,2]. Evidence indicates that environmental heterogeneity promotes species diversity, while spatial heterogeneity strongly influences species coexistence [3,4,5,6,7]. Recent theoretical syntheses have integrated the concepts of spatial heterogeneity with diversity, ecosystem stability and functioning within the framework of the metacommunity theory [8,9]. Spatial heterogeneity is particularly important in non-equilibrium communities of sessile organisms [10]. Such heterogeneity emerges when the local rates of natural processes vary within a community and when biotic interactions are spatially limited [1,4,11].

Plant communities recovering after agricultural abandonment are typical examples of non-equilibrium systems. During the self-organization of recovering vegetation, spatial heterogeneity emerges spontaneously [12,13,14,15,16]. However, the detailed mechanisms and patterns driving this process remain poorly understood.

Community-level spatial heterogeneity is often quantified by beta diversity, which reflects the spatial variability of species composition [17,18,19]. It has long been recognized that the degree of spatial beta diversity (i.e., the degree of spatial heterogeneity) is scale-dependent [20,21,22]. Most studies have found a negative relationship between beta diversity and plot size [21,22,23]. However, when analyses have been extended to very fine spatial resolutions (below 1 m scale), a quadratic relationship (unimodal maximum curve) has been observed, with beta diversity peaking at intermediate scales [20,24,25].

The scale dependence of spatial beta diversity can be understood through the combined perspectives of the species–area relationship and the minimum-area concept. The minimum-area concept [21,26,27] posits that plant communities become relatively homogeneous at a certain coarser spatial scale, where most core species occur within each sampling unit. At this scale, compositional variability among units—and thus spatial beta diversity—is minimized. As sampling unit size decreases, species richness declines according to the species–area relationship [28,29], and different species are increasingly absent from individual units. Consequently, compositional differences and beta diversity rise. At very fine scales, however, beta diversity may decline again when many small units become empty or contain only the same dominant species [25,30]. Such scaling patterns are typical of natural communities with stationary vegetation structure [20,23,25], the scaling behavior of non-equilibrium, successional systems is far less predictable and requires explicit empirical evaluation [30].

Most studies of beta diversity during old-field succession have been conducted at the landscape scale and typically address whether the composition of successional communities becomes more similar as recovery progresses [31,32]. Case studies have documented both increased between-field similarity over time (convergence [33,34]) and the opposite trend (divergence [35,36,37]), while other studies have revealed non-linear (both unimodal and multimodal) patterns [24,38,39,40].

In contrast, only a few studies explored beta diversity in succession at the within-stand scale. These investigations typically found divergence of species composition among plots sampled within-stand [34,35,41], although non-linear trends have also been reported [24,40,42,43,44,45]. Comparisons across spatial scales suggest that fine-scale plots often exhibit more stochastic dynamics and greater divergence, whereas coarser-scale plots tend to reveal more deterministic patterns and convergence [20,34,46].

The heterogeneity cycles model proposed by Armesto et al. [43] was developed to explain the non-linear patterns of beta diversity observed during succession. The model proposes that periods of high and low spatial heterogeneity alternate during vegetation succession based on the assumption that rates of species immigration and extinction are not constant over time. Heterogeneity increases when species invasions and establishments dominate over species extinctions, whereas it decreases during periods of mass extinction. These patterns are driven by the life cycle and spatial pattern development of a few dominant species. At their peak abundance, the spatial distribution of these species become more homogeneous as patches coalesce, while other species become suppressed or extinct. In contrast, in the earlier stage of the establishment and stand development of dominants, or later during their decline, more open spaces are available allowing the colonization and establishment of other species, which leads to higher microhabitat diversity. Early successional stages are typically dominated by short-lived species with high reproductive rates and strong dispersal abilities, while later stages are characterized by longer-lived, slower-spreading species that may co-dominate and form spatial mosaics. Consequently, the model predicts that as succession progresses, the wavelength of heterogeneity cycles increases, while their amplitude gradually decreases.

Only limited empirical evidence supports the heterogeneity cycles model. Most of the cases reviewed by Armesto et al. [43] were indirect, relying on diversity patterns as surrogates for spatial heterogeneity. Rejmánek and Rosén [22] later criticized these generalizations and emphasized the need for methodological improvement for more accurate testing. They argued that proper evaluation of the model requires long-term, continuous, permanent plot data and they also demonstrated the need for using different plot sizes. In the absence of strong empirical support we therefore refer to it as the hypothesis of cyclic heterogeneity in succession.

Vegetation recovery is a slow process, often taking several decades or even centuries [40,47,48,49]. Consequently, most studies have employed a space for the time substitution approach, reconstructing successional dynamics from independent sites of different ages [50,51,52]. However, such chronosequence data are unsuitable for testing the hypothesis of cyclic heterogeneity because they lack temporal continuity and provide only coarse temporal resolution. Studies based on old-field chronosequences have typically focused on robust general trends and disregarded the fine-scale variability and contingencies of data [35,40,44]. In contrast, permanent plot studies have revealed substantial interannual variability and dependence [13,53]. High-resolution monitoring data that are continuous in both space and time provide the most suitable framework for capturing spatial and temporal processes with variability and dependencies necessary to evaluate cyclic heterogeneity in succession.

The aim of this study was to describe the spatiotemporal dynamics of fine-scale species compositions during the first 16 years of a secondary grassland succession. Specifically, we tested the cyclic heterogeneity hypothesis, whether temporal patterns of beta diversity in recovering grassland vegetation exhibit distinct peaks and troughs over time. We used high-resolution monitoring data collected annually along permanent transects. Our study is novel in several aspects: (1) the hypothesis was tested in the context of grassland succession; (2) high-resolution spatial data allowed analyses across multiple spatial scales; and (3) null models were applied to disentangle the effects of species richness, relative abundances, and total abundances from structural constraints. The collected data also allowed the construction of space-time maps of various population and community characteristics for visual interpretation.

We set up the following hypotheses:

H1.

Within-stand spatial beta diversity shows overall increase during succession, reflecting divergence among local species compositions.

H2.

Beta diversity increase is not monotonic. We expect multiple temporal peaks indicating heterogeneity cycles in succession. Temporal fluctuations are expected to be large and spatially synchronized among sampling units.

H3.

Minimum heterogeneity is predicted to occur during the dominance of a particular species, driven by their competitive effect, which can result in mass extinctions of subordinate species. During this period, the abundances of subordinate species are expected to decrease, accompanied by corresponding declines in local species richness and evenness. Therefore, the temporal patterns of these characteristics are predicted to be synchronized with the pattern of spatial heterogeneity.

H4.

Beta diversity is scale-dependent, showing stronger fluctuations at finer spatial resolutions.

H5.

Abundance-based beta diversity exhibits clearer cyclic patterns than incidence-based measures, which are expected to appear more stochastic and they may not show cyclic patterns in some cases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

We studied two spontaneously recovering loess old fields abandoned in 2009 in the Great Hungarian Plain, at Tompapuszta (46.360° N, 20.980° E), near the town of Battonya in Hungary (CE Europe) (Supplementary Figure S1). The climate of the region is warm temperate with a sub-Mediterranean influence, characterized by a mean annual precipitation of 500–550 mm and a mean annual temperature of 10–11 °C (based on 30-year meteorological data from 1960 to 1990). The soil is humus-rich chernozem developed on a loess substrate. Monitoring sites were established in open, flat areas (without shrubs or trees) at similar elevations (99 m a.s.l.). The sites were physiognomically homogeneous without microtopographical or microclimatic variation. Disturbed patches (e.g., old roads) and small depressions were avoided during site selection. The old fields were located directly adjacent to a primary loess meadow steppe (‘Tompapusztai-löszgyep’). The grassland has remained in well-preserved condition and is therefore designated as a protected area, forming part of the Körös–Maros National Park. The dominant grass species in the natural grassland was Festuca valesiaca. Other common graminoid species included Poa angustifolia, Alopecurus pratensis, Carex praecox, and Elymus hispidus, while the high cover of perennial forbs, such as Teucrium chamaedrys, Galium verum, Fragaria viridis, Thymus pannonicus, and Salvia nemorosa, was also typical of the grassland [16,54,55]. Due to short distances between old fields and natural grasslands, most of these species colonized our monitoring sites during the study period. Both old fields were managed by a brush cutter between 2009 and 2016. Since 2017, the management changed to annual mowing [55].

2.2. Field Sampling

At each old field, a 52 m long permanent belt transect was established in a rectangular layout, creating a topologically circular sampling arrangement (see Supplementary Figure S2, for further details, see [16]). Species presence was recorded along the transects in 5 cm × 5 cm sampling units. Sampling took place annually in late May to early June, during the phenological optimum of the communities, for 15 consecutive years from 2011 to 2025. We chose this high-resolution, extensive sampling design, as it has been shown to effectively capture spatial variability and heterogeneity in grasslands [30]. In addition, the topologically circular arrangement of contiguous microquadrats along the transects is suitable for computerized sampling [30,56,57] and the application of various randomization approaches in null model analyses [58,59]. Six 2 m × 2 m permanent plots were also established near the permanent transects (Supplementary Figure S2). The percentage cover of vascular plant species was estimated in these quadrats, and the data were used to identify the dominant species. Since our monitoring started in the second year of old-field succession, we additionally sampled a 1-year-old stand in 2024, also adjacent to the natural grassland, collecting supplementary data at the earliest opportunity using the same methods as in the other fields (Supplementary Figure S2).

2.3. Data Analysis

The baseline transect data were resampled into evenly spaced segments, and species abundances were calculated for each segment by summing the recorded species presences within it. Three segment sizes (50 cm, 1 m, and 2 m) were used to represent three spatial scales (resolutions). These rescaled data were used in subsequent analyses. These scales were selected because previous studies identified the greatest variability of species combinations within this range [30], and they correspond to commonly used plot sizes in old-field and grassland vegetation surveys.

Beta diversity within old fields was quantified as the mean pairwise dissimilarity among sampling units [24,34,43]. Both incidence-based and abundance-based data were analyzed using Jaccard and Bray–Curtis dissimilarity indices, respectively [17,18,19]. Heterogeneity estimates from a 1-year-old stand are presented in the figures; however, these data were not included in the statistical analyses, which required temporally contiguous datasets.

These types of beta diversity measures reflect the spatial heterogeneity of vegetation in a given year. By repeating these analyses over time we aimed to explore the temporal changes in spatial heterogeneity to evaluate our first two hypotheses (H1 and H2).

To identify potential drivers of beta diversity, additional vegetation characteristics, such as the abundance of dominant species, species richness, evenness, and the total abundance of subordinate species, were also calculated for each segment [60].

According to our third hypothesis (H3), the temporal minima of spatial heterogeneity (i.e., minima of beta diversity) should occur when strong competitive effects of dominant species trigger mass extinctions of subordinate species. Such events are expected to reduce species abundances, richness, and evenness. As a consequence of mass extinctions, species abundances, species richness, and evenness will decrease as well. Therefore, the parallel changes in vegetation attributes and beta diversity provide evidence for the effects of strong competition.

Relationships between the temporal patterns of beta diversity and the temporal patterns of other vegetation characteristics were tested using synchrony analyses. To measure the synchrony of temporal fluctuations between two time series i and j, we applied a simple index proposed by Buonaccorsi et al. [61,62]. This index is defined as the ratio of the number of concurrent increases and decreases over time divided by the number of transitions. The synchrony of multiple series was expressed by the average of all pairwise measures. The significance of the observed synchrony was evaluated using null models randomizing the observed values among dates [63,64]. Strong synchrony between changing beta diversity and changing vegetation characteristics is expected if they all are driven by the strong competitive effects of dominant species.

To further test if observed heterogeneity (spatial beta diversity) was driven by the changes of species abundances, species richness, and evenness, Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) was processed. Using MLR we evaluated the relationship between the dependent variable (observed heterogeneity) and three potential predictor variables: total abundance of subordinates, number of species, and evenness. The analysis was performed using ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation to identify the best-fitting linear model. Model performance was evaluated through the coefficient of determination (R2), adjusted R2, F-statistic, and associated p-values to assess the significance of predictor variables, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Species abundances, species richness, and evenness characterize the vegetation at stand scale. They are classified as textural attributes to distinguish them from other more detailed structural vegetation attributes which provide information about the fine-scale spatial patterns (aggregations and associations) of species within plant communities [23,27,65]. To address our third hypothesis (H3) we evaluated the relative importance of textural and structural attributes for driving beta diversity patterns.

To distinguish the effects of textural constraints (i.e., the effects of total and relative abundance of species and species richness) from the effects of spatial patterns (i.e., aggregations and associations), we used null model analyses. Random assemblages were generated by randomizing the species presence along transects while maintaining the observed species richness and abundances (complete spatial randomness model, CSR). By this, we simulated a stochastic assembly process without dispersal limitations, priority effects, species interactions and habitat filtering. The procedure was repeated 2,500 times to obtain a null distribution of beta diversity for each field [66,67]. The standardized effect size (beta deviation) was calculated as the difference between the observed and mean expected beta diversity, divided by the standard deviation of expected values [34,68,69]. Zero beta deviation indicates that the observed pattern does not differ from the null model. Statistical significance was assigned using the criteria that beta deviation > 1.96 or beta deviation < −1.96 [69,70]. To further investigate the role of dominant species, all analyses were repeated after the exclusion of dominant species from the dataset.

In line with our fourth hypothesis (H4), we examined temporal patterns of beta diversity at three spatial scales (50 cm, 1 m, and 2 m). Relationships between temporal patterns of beta diversity recorded at different scales were tested using synchrony analyses. If the trends of temporal beta diversity patterns are scale-dependent, we expect low or absent synchrony among these patterns.

To test our fifth hypothesis (H5), we compared standardized effect sizes derived from null model analyses. H5 predicts that incidence-based beta diversity (Jaccard index) will show more stochastic temporal patterns and therefore yield consistently smaller effect sizes than abundance-based beta diversity (Bray–Curtis index).

JNP-model 2.0 software [71] was used to perform the randomizations and the computerized sampling. Dissimilarity indices were calculated with SYN-TAX 5.0 software package [72]. All other statistical analyses were conducted using Past v5.2.1 software package [73].

3. Results

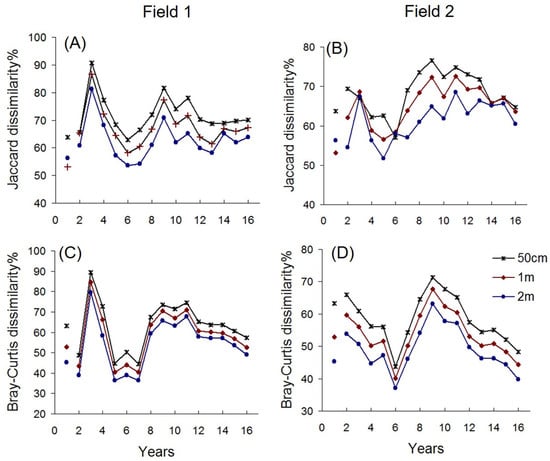

Mean compositional dissimilarity showed pronounced temporal fluctuations during the first 16 years of secondary grassland succession (Figure 1) with alternating periods of high and low spatial heterogeneity.

Figure 1.

Temporal trends in beta diversity at three spatial scales. Beta diversity was measured as incidence-based (Jaccard index) and abundance-based (Bray–Curtis index) dissimilarities. Continuous lines show results from monitoring between 2011 and 2025 in permanent transects. Separate points show a one-year old field sampled separately in 2024.

Two distinct heterogeneity cycles were detected: an early peak in 2–3-year old fields and a second peak around years 8–12. The two peaks were separated by a period of minimum dissimilarity in years 5–7. These patterns were consistent across both study sites (Field 1 and Field 2), robust to variation in spatial scale (Table 1), and stable across analytical methods (Figure 1). Abundance-based data (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity) indicated a decline in heterogeneity after 12 years, a trend also visible in the incidence-based data (Jaccard dissimilarity) from Field 2.

Table 1.

Synchrony of beta diversity time series recorded at different scales. Corrected p-values were adjusted by the Bonferroni–Holm method. Bold numbers indicate significant associations.

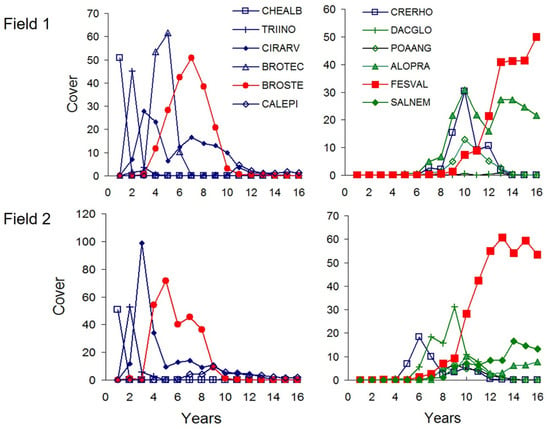

The period of minimum heterogeneity (in years 5–7) between the two cycles coincided with the dominance of Bromus species (particularly Bromus sterilis), while the subsequent decline in heterogeneity between years 12 and 16 corresponded to the increasing dominance of Festuca valesiaca (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean percentage cover of dominant species recorded in 2 m × 2 m permanent monitoring plots between 2011 and 2025. First year data represent an old field sampled separately in 2024. Abbreviations: CHEALB, Chenopodium album; TRIINO, Tripleurospremum inodorum; CIRARV, Cirsium arvense; BROTEC, Bromus tectorum; BROSTE, Bromus sterilis; CALEPI, Calamagrostis epigejos; CRERHO, Crepis rhoeadifolia; DACGLO, Dactylis glomerata; POAANG, Poa angustifolia; ALOPRA, Alopecurus pratensis; FESVAL, Festuca valesiaca; SALNEM, Salvia nemorosa. Weed species characteristic to early succession are marked by blue color. Green color represents grassland species from more advanced stages of succession. The two most important dominant species, Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca, are highlighted in red color.

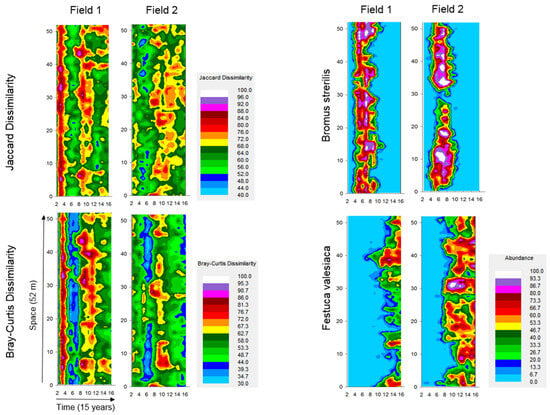

Fine-scale space-time maps supported these relationships (Figure 3), revealing spatially synchronized patterns of compositional heterogeneity with clear temporal periodicity. Bromus sterilis became widespread during years 4–8.

Figure 3.

Fine-scale spatiotemporal patterns of beta diversity measured as incidence-based (Jaccard index) and abundance-based (Bray–Curtis index) dissimilarities and abundances of two dominant species, Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca, estimated in 1 m long segments. Local dissimilarity in a segment is the mean dissimilarity between pairs of the particular segment and all other segments in a year. Abundances are sum of presences in 1 m segment, scaled between 0 and 100. Space-time maps are results from monitoring between 2011 and 2025 in permanent transects.

Abundance-based data showed a spatially synchronized decrease in heterogeneity in the period between years 12 and 16, parallel with the spread and increasing dominance of Festuca valesiaca. Other abundant species exhibited more localized, patchy distributions (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure S3). Overall, Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca were associated with low or declining compositional heterogeneity, while aggregated patterns of other species corresponded to periods of maximum heterogeneity.

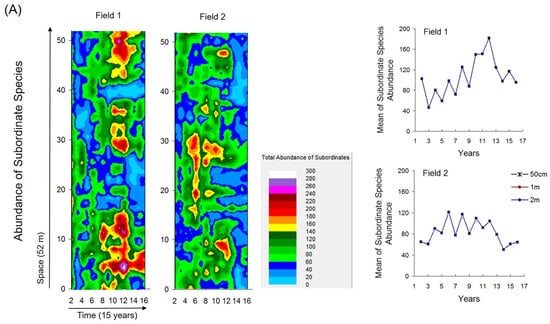

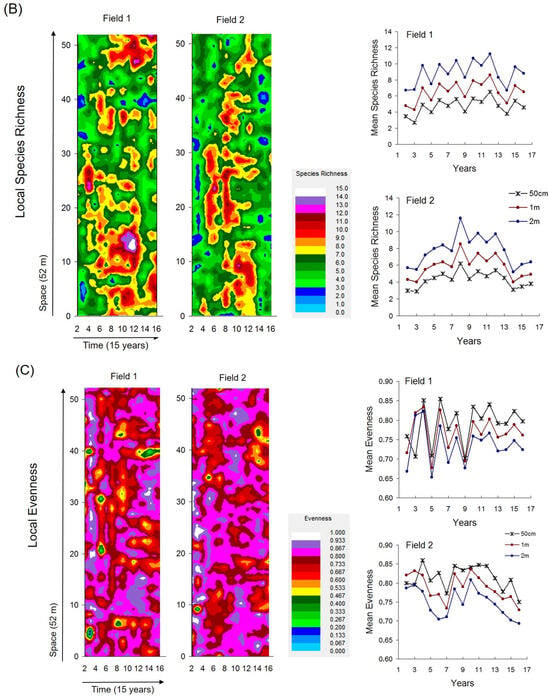

Fine-scale spatiotemporal maps of selected coenostate characteristics (i.e., local abundance of subordinate species, local species richness, and local evenness) revealed distinct spatial and temporal dynamics (Figure 4A–C).

Figure 4.

Fine-scale spatiotemporal patterns of local community characteristics estimated at 1 m scales and mean community characteristics over time at three scales. (A) Abundances of subordinate species (total abundance after excluding Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca). (B) Species richness. (C) Evenness.

These maps reflected self-organized patch dynamics that were largely independent of the heterogeneity cycles. The highest local abundances and species richness occurred during mid-successional stages, following unimodal temporal patterns, whereas local evenness showed strong spatiotemporal variability without a clear trend. These characteristics varied separately and were not significantly correlated with compositional heterogeneity (Supplementary Tables S1–S5).

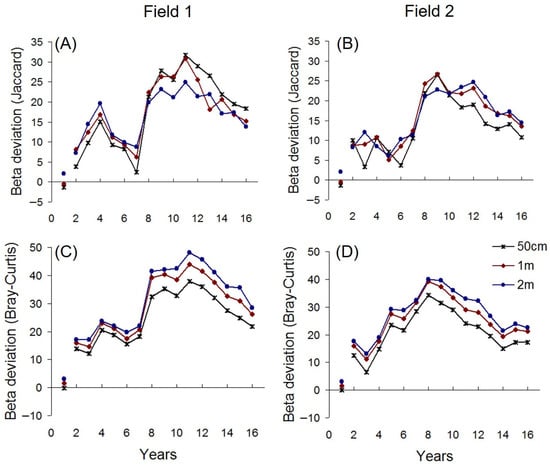

After controlling for textural constraints, i.e., after removing the effects of species richness, total abundance, and relative abundance on the compositional dissimilarity, the resulting beta deviation still displayed similar heterogeneity cycles. Although the first peak was smaller, both cycles of beta deviation were clearly present in Field 1, while the first peak disappeared in Field 2 (Figure 5). These patterns were consistent across scales at both sites (Field 1 and Field 2) (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Temporal trends of beta deviation at three spatial scales. The standardized effect size (beta deviation) shows the magnitude of deviation between observed beta diversity and the values generated by null models. Positive values > 1.96 indicate higher beta diversity than in random assemblages. Continuous lines show results from monitoring (2011–2025) in permanent transects. Separate points show a one-year old field sampled separately in 2024.

Table 2.

Synchrony of beta deviation time series recorded at different scales. Corrected p-values were adjusted by the Bonferroni–Holm method. Bold numbers indicate significant associations.

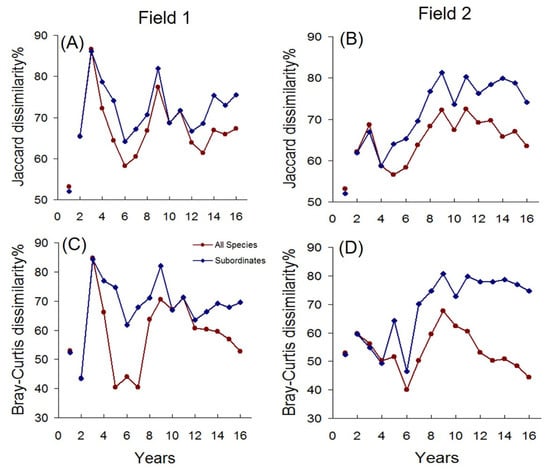

To test whether the observed heterogeneity cycles reflected community-level phenomena or were primarily driven by the spatial dynamics of dominant species, we removed Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca from the dataset and repeated the analyses. As heterogeneity patterns were highly synchronized across scales, we performed these analyses at only one scale (with 1 m segment sizes). After removing the two dominant species, the compositional heterogeneity of subordinate species still exhibited cycling patterns (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Temporal trends in beta diversity at 1 m spatial scale after excluding the two dominant species (Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca) from the analyses. Beta diversity was measured as incidence-based (Jaccard index) and abundance-based (Bray–Curtis index) dissimilarities. Continuous lines show results from monitoring (2011–2025) in permanent transects. Separate points show a one-year old field sampled separately in 2024.

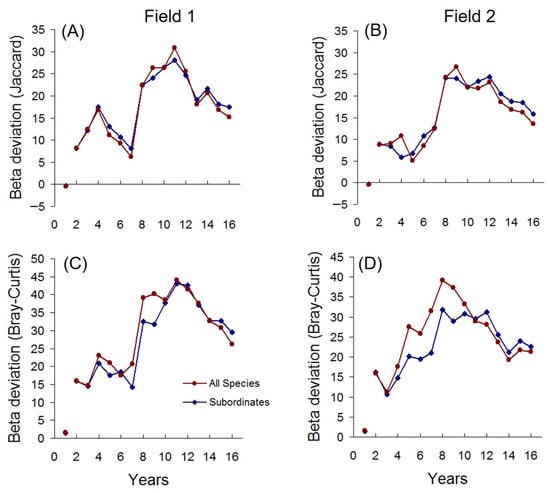

The position of the minimum between heterogeneity peaks remained consistent, although with slightly higher values. However, the declining phase after the second maximum (at year 9) disappeared. Comparison of beta deviation patterns between datasets with and without dominant species showed nearly identical values (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Temporal trends of beta deviation at 1 m spatial scale after excluding the two dominant species (Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca) from the analyses. The standardized effect size (beta deviation) shows the magnitude of deviation between observed beta diversity and the values generated by null models. Positive values > 1.96 indicate higher beta diversity than in random assemblages. Continuous lines show results from monitoring (2011–2025) in permanent transects. Separate points show a one-year old field sampled separately in 2024.

Synchrony tests did not reveal significant relationships between the temporal variations in dissimilarities and the temporal variations in total abundances, species richness, and evenness (Supplementary Tables S1–S4). Nevertheless, removing dominant species provided indirect evidence for the role of textural constraints: dissimilarities increased after the removal of dominants. (Figure 6). In contrast, beta deviations remained largely unchanged (Figure 7), indicating that the overall aggregation and association structure of subordinate species persisted despite the removal of dominants.

4. Discussion

We analyzed spatial heterogeneity patterns during secondary grassland succession using long-term monitoring data collected along two permanent transects over 15 years. Our results revealed considerable temporal fluctuations in spatial beta diversity. In particular, two distinct peaks were detected during transitions between successional phases, while periods of minimum heterogeneity coincided with the dominance of certain species. These patterns were robust across spatial scales and dissimilarity indices and varied little after excluding the dominant species and removing the effects of species richness and abundance in null models. These findings support the cycling heterogeneity hypothesis in secondary grassland succession. Null model analyses further indicated that the first cycle (occurring during the transition between the pioneer and early successional phases) was mainly driven by textural constraints (species richness and abundances), whereas the second cycle (during the transition between the early- and mid-successional phases) was more strongly influenced by structural constraints (spatial aggregations and associations).

4.1. Heterogeneity Cycles in Secondary Grassland Succession

When spatial heterogeneity was analyzed within stands of recovering plant communities, most previous studies reported increasing dissimilarity of local species composition among sampling units during old-field succession [34,35,41]. In contrast, our study did not reveal this expected trend of divergence, leading us to reject our first hypothesis (H1). However, the observed temporal fluctuations support our second hypothesis (H2) about the existence of heterogeneity cycles in succession. The magnitude of these fluctuations (i.e., the amplitude of cycles) was high, ranging between 80% and 100% of the total heterogeneity detected over the 16 years of succession. We applied the same methods as in earlier studies to allow for a direct comparison of results. Theoretically, both the Jaccard and the Bray–Curtis indices range from 0% to 100%. Secondary succession begins on bare soil, typically following the abandonment of agriculture, and develops into a recovered vegetation. During this successional process, we expect an overall increase in total abundance, diversity, and heterogeneity [2,49]. In our study, the Jaccard index (at 1m scale) varied between 53.1% and 86.6%, while the Bray–Curtis index ranged from 40.0% to 84.6%. It is important to note that expecting 0% or 100% heterogeneity in the observed patterns would be unrealistic. Even in the first year of secondary succession, some heterogeneity (ca. 40–50%) emerged due to the spatial heterogeneity of seed bank and microhabitat conditions, local disturbances (e.g., by small mammals), and stochastic effects during propagule dispersal and establishment. When comparing the observed values from our study to those reported in other studies that used similar methods and spatial scales, the ranges of beta diversities were surprisingly similar. For example, the Jaccard index varied between 50% and 75% and the Bray–Curtis index between 30% and 80% over 50 years of secondary forest succession in New Jersey, USA [34], while in another study on grassland succession on a Minnesota sand plain, USA, the Jaccard index ranged from 47% to 75% over 56 years [35]. The study by Inouye et al. [35] was based on a space-for-time substitution approach (i.e., they sampled separate fields of different ages). Therefore, their data cannot be used to estimate interannual heterogeneity changes. In contrast, Li et al. [34] used permanent plots, making their results directly comparable to ours (cf. Figure 2. in Li at al. [34]). In their study, the range of heterogeneity changes during succession was similar to that observed in our results. However, the magnitude of temporal fluctuations was small, accounting for less than 10% of the total range. In our study, conducted in a xeric old-field succession in Hungary, the magnitude of temporal fluctuations varied between 80% and 100% of the range, depending on the monitoring site, spatial scale, and dissimilarity index. Thus, while heterogeneity cycles did not occur during the forest succession investigated in New Jersey, their presence was clearly evident in our study.

In their original paper, Armesto et al. [43] reported a single cycle lasting 8 years (between years 2 and 10 of succession). The amplitude of this cycle (i.e., the difference between maximum and minimum heterogeneity) was 20% (the Jaccard index varied between 38% and 58%). In this short-term dataset, the range of heterogeneity variation and the amplitude of the cycle were equal, meaning that the size of temporal fluctuations was 100% of the range. Armesto et al. [43] suggested that heterogeneity cycles were driven by a few dominant species. In their case study of a mesic secondary old-field succession in central New Jersey, USA, Ambrosia artemisiifolia (an annual herb) was the first dominant species occupying the entire field and creating homogeneity at the beginning of succession. The second dominant species, Solidago canadensis (a tall perennial clonal herb), became abundant after ca. 10 years. According to the model of Armesto et al., dominant species generated homogeneity by suppressing diversity through strong competition with other species. Between these two homogeneous states, a heterogeneity cycle developed. Armesto et al. [43] predicted that in later successional stages Juniperus virginiana and Acer rubrum would create similar homogeneous phases, so that these four dominant species together would generate three heterogeneity cycles during succession. In our study, the first dominant species to occupy the entire field were segetal weeds, Tripleurospermum inodorum and Chenopodium album (two annual forbs). The next dominant species was a ruderal weed, Bromus sterilis (an annual grass) developing after 5–8 years. This was followed by Festuca valesiaca (a perennial grass, the dominant species of the original meadow steppe community), which became abundant after 10–12 years. These three dominant species created two heterogeneity cycles: the first peak appeared in the overlap between pioneers and early successional species, while the second peak occurred during the transition between the early and middle stages of succession.

The cycling heterogeneity model was expected to be relevant in forest succession, where there are well-defined stages characterized by distinct life forms (annuals, herbaceous perennials, shrubs and vines, pioneer trees, early successional trees, and late successional trees). In contrast, the existence of cycles is less obvious in grassland succession, where changes occur more gradually and dominant species have similar life forms, as most are perennial herbs. However, in our study, we identified two clear heterogeneity cycles evident from our long-term dataset. To our knowledge, these results provide the first strong evidence supporting the cycling heterogeneity hypothesis. Heterogeneity cycles can be interpreted as alternating periods of divergence and convergence. Other studies reporting alternating periods of divergence and convergence during succession may also have recorded evidence of cyclic heterogeneity [38,40,44]. However, these studies did not use permanent plots, and therefore could not prove directly the existence of fluctuating heterogeneity during succession. The model of Armesto et al. predicted decreasing amplitudes and increasing wavelength of heterogeneity cycles over succession due to changes in the life history of dominant species. In our study, the first dominants were annuals, later replaced by a perennial. The wavelength of the first cycle was shorter, lasting two years (between years 2 and 4 of succession), whereas the second cycle was longer, beginning in the 7th year and still not reaching a clear minimum by the end of our study (by the 16th year). In contrast, we did not find any differences between the amplitudes of the first and the second cycles.

4.2. Drivers of Heterogeneity Changes

How do dominant species influence the compositional heterogeneity of the whole community? Early studies on the development of spatial patterns described a general trend of changing heterogeneity during the stand development of a single species [74,75,76]. In the early stages of colonization and establishment, species form nearly random patterns, which gradually shift to aggregated patterns as the population size increases. Maximum heterogeneity occurs when a species occupies half of the area (i.e., its frequency is 50%). As its abundance increases further, patches tend to coalesce, and the spatial pattern becomes more homogeneous. These changes in spatial pattern during the dynamics of a single species suggest the existence of a single heterogeneity cycle. During succession, when several dominant species replace one another, multiple heterogeneity cycles may develop and potentially interfere.

The model of cyclic heterogeneity predicts strong competitive effects between the dominant and the subordinate species. Spatial beta diversity (heterogeneity) decreases when the dominant species is present in the majority of sampling units. During peak abundances, the dominant species excludes many other species. As a consequence, local species richness and the local abundance of subordinates will decrease, further reducing spatial heterogeneity. Local evenness also declines due to the local extinction of subordinates. If mass exclusion of subordinate species occurs during the heterogeneity minimum, temporal patterns of beta diversity should correlate with the temporal patterns of local species richness, local evenness, and local abundance of subordinates. However, in our study, we did not find such correlations. Subordinate abundances and local species richness followed typical unimodal temporal patterns, consistent with many other studies [77,78]. Local evenness showed considerable temporal fluctuations, but these were not synchronized with the patterns of heterogeneity. Therefore, we must reject our third hypothesis (H3). The lack of correlations suggests that competitive exclusions may not play a prominent role in the pattern development and the spatial organization of this system. Li et al. [79] reported similar results and concluded that the pattern of colonization is more important than the pattern of competitive exclusion during community organization in old-field succession.

An alternative “neutral” explanation may account for the observed patterns of heterogeneity minima. Beta diversity might decrease simply due to the increasing abundance of dominant species, without affecting the patterns of other species. This explanation is plausible because the minimum beta diversity coincided with the maximum abundance of dominant species. To test this explanation, we removed dominant species from the dataset and repeated the beta diversity analyses including only subordinate species. If heterogeneity cycles were driven exclusively by fluctuations in the abundance of dominants, the cycling pattern should disappear. Our results partially support the neutral explanation, as spatial heterogeneity increased following the removal of dominant species. However, the fluctuating temporal patterns of heterogeneity cycles persisted, and the beta deviation patterns remained largely invariant. The observed changes in dissimilarity patterns highlight the neutral contributions of Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca, although other abundant species also contributed. Certain co-dominant species (Bromus tectorum, Poa trivialis, and Veronica arvensis at Field 1 and Poa trivialis and Crepis setosa at Field 2) were abundant enough to maintain the heterogeneity minimum in year 6. Later in succession (between years 12 and 16), Poa angustifolia, Alopecurus pratensis, and Galium verum at Field 1, Alopecurus pratensis, Galium verum, and Salvia nemorosa at Field 2 likely played a similar role. The detected patterns of significant beta deviations and the invariance of beta deviation patterns after removing Bromus sterilis and Festuca valesiaca indicate that structural constraints were also important, with their influence increasing over the progress of succession. These results show that both textural constraints (total abundance, relative abundance, and species richness) and structural constraints (spatial aggregations and species associations) shape beta diversity patterns. Compositional heterogeneity in the first year of succession was generated entirely by textural constraints, as beta deviation was not significant in this pioneering stage. Between years 2 and 6, textural constraints remained more influential, while structural constraints gradually became increasingly important in subsequent years. Local minima in the temporal patterns of beta deviations indicate periods of partial disassembly of spatial patterns. Overall, the mechanisms driving beta diversity patterns are probably more complex than originally suggested by Armesto et al. [43]. For example, many studies reported the negative effects of dominant species in secondary succession [80,81,82,83,84]. However, Akatov et al. [85] demonstrated that competitive effects of dominant species operate locally at the patch scale and are often masked or disappear at the field scale.

4.3. Scale Dependence of Beta Diversity Patterns

Rejmánek and Rosén [22] found different successional patterns at different scales: beta diversity increased at fine scales but remained nearly constant at coarser scales. Other studies reported opposite trends in succession, with increases at fine scale and decreases at coarser scale over time [20,46]. These scale-dependent temporal trends appeared within the same stand and they were similar to the trends found in another study [34] comparing within- versus between-field patterns. Li et al. [34] observed increasing dissimilarity between sampling units within fields (i.e., divergence at fine scale) and decreasing dissimilarity between sampling units across fields (i.e., convergence at coarse scale). In contrast, the beta diversity patterns in our study were very similar across scales with significant synchrony of temporal fluctuations. Dissimilarities were slightly larger at finer scale but the ranges of variation were almost identical, i.e., independent of scale. Therefore, we have to reject our fourth hypothesis (H4). The synchrony between scales in our study can be explained by the relatively small sizes of sampling units and by the small differences between scales (50 cm, 1 m, 2 m). We chose these scales to correspond to the plot sizes used in the majority of earlier studies. However, as the sizes of these sampling units were smaller than the typical sizes of vegetation patches [16], they indicated similar patterns.

We expected more stochastic patterns with incidence-based data (Jaccard index), particularly at the finer scale (H5). Although the cyclic patterns were slightly more pronounced using abundance-based data of the observed beta dissimilarity (Bray–Curtis index), these differences were minor and did not depend on scale. However, after applying null model analysis, deviations from the null model were smaller with incidence-based data and also smaller at finer scales, indicating more stochastic patterns and supporting our fifth hypothesis (H5). Table 3. Summarizes the five hypotheses and the related results.

Table 3.

Summary of results.

4.4. Limitations and Perspectives

Why have so few case studies tested the cyclic heterogeneity hypothesis? As Rejmánek and Rosén [22] noted, the proper and rigorous testing of this hypothesis requires long-term, annually sampled permanent plot data. They further stressed the importance of monitoring at multiple spatial scales with different plot sizes; however, implementing more than one plot size substantially increases the necessary sampling efforts. One practical alternative to reduce cost and labor is to use permanent grids or transects and apply computerized resampling of the baseline data at different plot sizes [30,56,86,87,88]. More recently, measuring beta diversity through remote sensing seems to provide a promising approach [89,90]. For example, hyperspectral imaging enables the assessment of the spatial patterns of dominant species without laborious field sampling [91]. In our study, we found that only a few abundant species largely determined the variability of beta diversity. The resulting patchwork of dominant species can be effectively assessed by remote sensing. We illustrate this potential by a space-time map of the locally dominant species created from the cover data of our 2 m × 2 m permanent plots (Supplementary Figure S4) and by photos about representative stages of vegetation development (Figure A1). Minimum heterogeneity, characterized by single or few dominant species, occurred in years 2 and 6, while maximum heterogeneity, with several dominant species, appeared in years 3 and 9. These simple, visually recognizable patterns correspond well with the results obtained from detailed sampling and beta diversity analyses.

The temporal extent of such studies is also critical. Although a large number of studies used permanent plots to document vegetation dynamics [92,93], few have lasted longer than five years [94]. In the original publication by Armesto et al. [43], eight years of data were analyzed and only a single cycle was detected. Our study was based on 16 years of permanent plot data and revealed two cycles. The spatial extent is another unexplored dimension. For practical reasons, most studies estimate the state of vegetation at the field level. However, the parcel of an abandoned field does not represent a natural unit. In contrast, during spontaneous re-assembly, vegetation organizes into dynamic hierarchic patchworks [95,96]. Fitting sampling designs that align with the natural scales of these patchworks would provide more accurate estimates of heterogeneity. For example, Akatov’s [85] results showed that the negative effects of dominant species manifest locally at the patch scale. Testing cycles of heterogeneity at this scale would offer more detailed results, potentially detecting more heterogeneity cycles.

In this study, we used the same methods (Jaccard and Bray–Curtis indices) as previous studies to assess the within-stand heterogeneity. However, a wide range of alternative beta diversity measures exist [19,27,97,98,99,100,101]. Exploring heterogeneity patterns with multiple-site measures and decomposing heterogeneity into its components [26,98,102,103,104,105] would help to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

In this study we focused on potential biotic drivers of spatial heterogeneity in line with the hypothesis of Armesto et al. [43]. Nonetheless, weather variability (particularly extremely dry or wet years) may also influence heterogeneity. Previous work showed that annual species richness declines in exceptionally dry years in natural grasslands [64]. At our site, 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2022 were notably dry, yet minima in spatial heterogeneity did not correspond consistently with annual precipitation minima. Strong temporal contingencies arising from the intrinsic dynamics of plant populations likely mask any detectable effects of weather variability in this system.

The existence of cyclic heterogeneity in secondary succession has important practical implications. Temporal fluctuation in heterogeneity reflects changes in microhabitat diversity. We argue that restoration practices (e.g., sowing seeds) would be more effective if applied during periods of maximum spatial heterogeneity and maximum microhabitat diversity [65,106]. When microhabitat diversity is high, seeds had higher chance to find safe microhabitats for germination and establishment. In addition, high spatial heterogeneity (e.g., aggregated spatial arrangements of dominant species) increases the probability of the survival of subordinate species [106]. Therefore, collecting information on the changing heterogeneity during vegetation recovery could improve the effectiveness of habitat restoration.

Since Watt’s seminal paper [107], the linkage between pattern and process has become a central theme in the coarse-scale landscape ecology [108,109]. These concepts, however, are equally applicable to fine-resolution spatial patterns within plant communities. From a plant’s-eye perspective and by approaching vegetation at the scale of individual plants [110,111,112], similar questions and approaches used in traditional landscape ecology can be applied at much smaller spatial grains [102]. Although numerous theoretical models highlight the importance of fine-scale spatial structure in driving vegetation dynamics (e.g., [113,114,115,116,117,118]), empirical tests remain rare due to limited availability of spatially explicit field data (but see [119,120]).

In our study, we recorded fine-scale vegetation maps over 15 years that provide a unique dataset for future analyses of how the spatial arrangement of dominant individuals shapes key temporal processes—such as changes in subordinate species and local immigration and extinction rates—that ultimately govern coexistence within plant communities.

5. Conclusions

After monitoring the spatial pattern development of recovering grassland vegetation during old-field succession for 15 years, we were able to test the cyclic heterogeneity hypothesis that was proposed more than 30 years ago but has rarely been tested. Rigorous testing required data that were continuous over both space and time. High spatial resolution and continuity were essential for the accurate estimation of spatial beta diversity, which can be underestimated at too coarse spatial resolutions. Contiguous data also enabled spatial scaling by resampling the original high-resolution data at different scales. Likewise, high temporal resolution and temporal continuity were necessary for detecting trends of interannual changes and the high-frequency temporal variation. We recorded annually the presence of plant species in 5 cm × 5 cm contiguous microquadrats along 52 m permanent transects. This sampling design combined the high spatial resolution with the high spatial extent, optimizing the monitoring for estimating the dynamics of spatial heterogeneity.

We found strong temporal fluctuations of spatial heterogeneity with two peaks forming two cycles. Our results provide rigorous evidence supporting the cyclic heterogeneity hypothesis. By using null models, we were able to separate the effects of textural constraints (species richness and abundances) from the effects of structural constraints (spatial aggregations and associations). The relative importance of structural constraints increased over succession; however, temporal fluctuations in species abundances remained the primary driving factor. Minimum spatial heterogeneity occurred in periods when the maximum abundance of certain species exceeded a threshold, leading to their dominance.

The non-linear temporal patterns and high variability of beta diversity found in this study have important practical implications. We suggest that timing restoration measures could be critical, as practices are likely to be more effective when applied in years of increased spatial heterogeneity. We further recommend the annual monitoring of vegetation patterns during restoration to forecast spatial heterogeneity and optimize management strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122381/s1, Figure S1: Location of the study areas; Figure S2: Sampling design; Figure S3: Fine-scale spatiotemporal patterns of the abundances of selected species; Figure S4: Space-time map of dominant species. Tables S1–S4: Synchrony between beta diversity and other coenological characteristics; Table S5: Multiple Linear Regressions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., S.C. and A.I.C.; methodology, S.B.; software, S.B. and S.C.; validation, A.I.C. and S.B.; formal analysis, S.C. and S.B.; investigation, D.P., J.H., Z.Z., Z.E.G., S.C., G.S. and A.I.C.; data curation, A.I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B. and S.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, S.B.; supervision, A.I.C.; project administration, A.I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the FLAGSHIP RESEARCH GROUPS PROGRAMME 2024 of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request. Data available on request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank András János Csathó, Csaba Molnár, Melinda Juhász, Róbert Kun, Zsuzsanna Sutyinszki, Szilárd Szentes, Klára Virágh, and Cecília Komoly for their help in data collection. We thank the Körös–Maros National Park Directorate for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

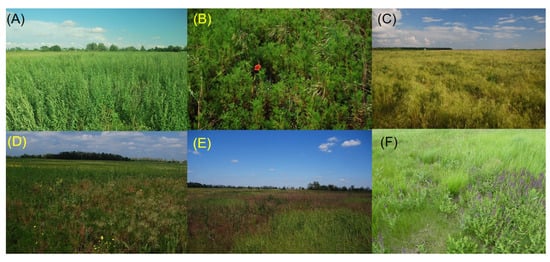

Figure A1.

Typical states of recovering vegetation in old-field succession near Battonya in Hungary. Homogeneous stands: (A) 1-year-old stand dominated by Chenopodium album; (B) 2-year-old stand dominated by Tripleurospermum inodorum; and (C) 6-year-old stand dominated by Bromus sterilis. Heterogeneous stands representing vegetation transitions: (D) 3-year-old stand with Tripleurospermum inodorum and Bromus spp.; (E) 10-year-old stand with Bromus strerilis, Calamagrostis epigejos, and Alopecurus pratensis; and (F) 14-year-old stand with Festuca valesiaca, Salvia nemorosa, and Alopecurus pratensis. (Photo from S. Bartha).

References

- Kolasa, J.; Pickett, S.T.A.; Allen, T.F.H. (Eds.) Ecological Heterogeneity; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- Begon, M.; Towsend, C.R. Ecology: From Individuals to Ecosystems, 5th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 864. [Google Scholar]

- Amarasekare, P. Competitive coexistence in spatially structured environments: A synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolker, B.M.; Pacala, S.W.; Neuhauser, C. Spatial dynamics in model plant communities: What do we really know? Am. Nat. 2003, 162, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, J.T. Plant species diversity and environmental heterogeneity: Spatial scale and competing hypotheses. J. Veg. Sci. 2009, 20, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamme, R.; Hiiesalu, I.; Laanisto, L.; Szava-Kovats, R.; Pärtel, M. Environmental heterogeneity, species diversity and co-existence at different spatial scales. J. Veg. Sci. 2010, 21, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, T.; Wang, X.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Bourg, N.A.; Cao, M.; Ci, X.; Davies, S.J.; Hao, Z.; Howe, R.W.; Kress, W.J.; et al. Consequences of spatial patterns for coexistence in species-rich plant communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Germain, R.M.; Srivastava, D.S.; Filotas, E.; Dee, L.E.; Gravel, D.; Thompson, P.L.; Isbell, F.; Wang, S.; Kéfi, S.; et al. Scaling-up biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loreau, M.; Barbier, M.; Filotas, E.; Gravel, D.; Isbell, F.; Miller, S.J.; Montoya, J.M.; Wang, S.; Aussenac, R.; Germain, R.; et al. Biodiversity as insurance: From concept to measurement and application. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 2333–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czárán, T. Spatiotemporal Models of Population and Community Dynamics; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1998; p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Szolnoki, A.; Perc, M. Biodiversity in models of cyclic dominance is preserved by heterogeneity in site-specific invasion rates. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepš, J.; Burianek, V. Interspecific associations in old field succession. In Spatial Processes in Plant Communities; Krahulec, F., Agnew, A.D.Q., Agnew, S., Willems, J.H., Eds.; SPB Publ: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Bartha, S. Implications from Buell-Small Succession Study for vegetation restoration. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2001, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaplata, M.K.; Winter, S.; Fischer, A.; Kollmann, J.; Ulrich, W. Species-driven phases and increasing structure in early-successional plant communities. Am. Nat. 2013, 181, E17–E27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, W.; Zaplata, M.K.; Winter, S.; Schaaf, W.; Fischer, A.; Soliveres, S.; Gotelli, N.J. Interspecific interactions and random dispersal rather than habitat filtering drive community assembly during early plant succession. Oikos 2016, 125, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, S.; Házi, J.; Purger, D.; Zimmermann, Z.; Szabó, G.; Guller, Z.E.; Csathó, A.I.; Csete, S. Fine-Scale Organization and Dynamics of Matrix-Forming Species in Primary and Secondary Grasslands. Land 2025, 14, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H. A diversity of beta diversities: Straightening up a concept gone awry. Part 2. Quantifying beta diversity and related phenomena. Ecography 2010, 33, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Crist, T.O.; Chase, J.M.; Vellend, M.; Inouye, B.D.; Freestone, A.L.; Sanders, N.J.; Cornell, H.V.; Comita, L.S.; Davies, K.F.; et al. Navigating the multiple meanings of diversity: A roadmap for the practicing ecologist. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; De Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: Dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász-Nagy, P.; Podani, J. Information theory methods for the study of spatial processes and succession. Vegetatio 1983, 51, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, J. The determination of minimal area of phytocoenoses. Folia Geobot. Phytotax. 1973, 8, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejmanek, M.; Rosen, E. Cycles of Heterogeneity during Succession: A Premature Generalization? Ecology 1992, 73, 2329–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podani, J.; Czárán, T.; Bartha, S. Pattern, area and diversity: The importance of spatial scale in species assemblages. Abstr. Bot. 1993, 17, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bartha, S.; Canullo, R.; Chelli, S.; Campetella, G. Unimodal Relationships of Understory Alpha and Beta Diversity along Chronosequence in Coppiced and Unmanaged Beech Forests. Diversity 2020, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gillet, F.; Bartha, S.; Alato, J.M.; Biurrun, I.; Dembicz, I.; Grytnes, J.-A.; Jaunatre, R.; Pielech, R.; Van Meerbeek, K.; et al. Scale dependence of species–area relationships is widespread but generally weak in Palaearctic grasslands. J. Veg. Sci. 2021, 32, e13044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász-Nagy, P. Spatial dependence of plant populations. Part 2. A family of new models. Acta Bot. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1984, 30, 363–402. [Google Scholar]

- Juhász-Nagy, P. Notes on compositional diversity. Hydrobiologia 1993, 249, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrhenius, O. Species and area. J. Ecol. 1921, 9, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengler, J.; Matthews, T.J.; Steinbauer, M.J.; Wolfrum, S.; Boch, S.; Chiarucci, A.; Conradi, T.; Dembicz, I.; Marcenò, C.; García-Mijangos, I.; et al. Species–area relationships in continuous vegetation: Evidence from Palaearctic grasslands. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, S.; Campatella, G.; Canullo, R.; Bódis, J.; Mucina, L. On the importance of fine-scale spatial complexity in vegetation restoration. Int. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2004, 30, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lepš, J.; Rejmánek, M. Convergence or Divergence: What Should We Expect from Vegetation Succession? Oikos 1991, 62, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, C.L.; Drake, J.A. Divergent perspectives on community convergence. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1997, 12, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prach, K. Succession of vegetation in abandoned fields in Finland. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 1985, 22, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.-p.; Cadotte, M.W.; Meiners, S.J.; Pu, Z.; Fukami, T.; Jiang, L. Convergence and divergence in a long-term old-field succession: The importance of spatial scale and species abundance. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, R.S.; Huntly, N.J.; Tilman, D.; Tester, J.R.; Stillwell, M.; Zinnel, K.C. Old-Field succession on a Minnesota Sand Plain. Ecology 1987, 68, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Jírová, A.; Doležal, J. Pattern of succession in old-field vegetation at a regional scale. Preslia 2014, 86, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.T.; Knops, J.M.H.; Tilman, D. Contingent factors explain average divergence in functional composition over 88 years of old field succession. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, N.L.; Peet, R.K. Convergence during Secondary Forest Succession. J. Ecol. 1984, 72, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Shao, H.-B.; Shan, L.; Liang, Z.-S.; Shao, M.-A. Secondary succession and its effects on soil moisture and nutrition in abandoned old-fields of hilly region of Loess Plateau, China. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 58, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelli, S.; Tsakalos, J.L.; Zhu, Z.; De Benedictis, L.L.M.; Bartha, S.; Canullo, R.; Borsukevych, L.; Cervellini, M.; Campetella, G. The diversity of within-community plant species combinations: A new tool for assessing changes in forests and guiding protection actions. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, L.; Llambí, L.; Escalona, A.; Marquez, N. Vegetation patterns, regeneration rates and divergence in an old-field succession of the high tropical Andes. Plant Ecol. 2003, 166, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, R.K.; Christensen, N.L. Changes in species diversity during secondary forest succession on the North Carolina Piedmont. In Diversity and Pattern in Plant Communities; During, H.J., Werger, M.J.A., Willems, J.H., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Armesto, J.J.; Pickett, S.T.A.; McDonnell, M.J. Spatial heterogeneity during succession: A cyclic model of invasion and exclusion. In Ecological Heterogeneity; Kolasa, J., Pickett, S.T.A., Allen, T.F.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 256–269. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Chai, Z.; Liu, G.; Xue, S. Changes in species diversity patterns and spatial heterogeneity during the secondary succession of grassland vegetation on the loess plateau, China. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, J.; Brandl, R.; Klotz, S. Plant communities converge to resource-dependent transient states during succession on old fields. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogeweg, P.; Hesper, B.; van Schaik, C.P.; Beeftink, W.G. Patterns in vegetation succession, an ecomorphological study. In The Population Structure of Vegetation; White, J., Ed.; Dr. W. Junk Publishers: Dordreht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 637–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, V.A.; Hobbs, R.J.; Standish, R.J. What’s new about old fields? Land abandonment and ecosystem assembly. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Durigan, G.; Fennessy, S.; Overbeck, G.E.; Torezan, J.M.; Murphy, S.D. A primer on choosing goals and indicators to evaluate ecological restoration success. Restor. Ecol. 2019, 27, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Walker, L.R. Comparative Plant Succession Among Terrestrial Biomes of the World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, S.T.A. Space-for-time substitution as an alternative to long-term studies. In Long-Term Studies in Ecology; Likens, G.E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, Z.; Botta-Dukát, Z. Improved space-for-time substitution for hypothesis generation: Secondary grasslands with documented site history in SE-Hungary. Phytocoenologia 1998, 28, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.R.; Wardle, D.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; Clarkson, B.D. The use of chronosequences in studies of ecological succession and soil development. J. Ecol. 2010, 98, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A. Population patterns through twenty years of oldfield succession. Vegetatio 1982, 49, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csathó, A.J.; Csathó, A.I. The floralist of the Külső-gulya meadow of Battonya-Tompapuszta (SE Hungary). Crisicum 2009, 5, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Guller, Z.E.; Házi, J.; Bartha, S.; Molnár, C.; Purger, D.; Szabó, G.; Zimmermann, Z.; Csathó, A.I. Grassland Reconstruction of a loess old-field by sowing the dominant grass besides other target species. Tájökológiai Lapok—J. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 20 (Suppl. S2), 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podani, J. Analysis of mapped and simulated vegetation patterns by means of computerized sampling techniques. Acta Bot. Hung. 1984, 30, 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Podani, J. Computerized sampling in vegetation studies. Coenoses 1987, 2, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.W.; van der Maarel, E. Variance in species richness, species association, and niche limitation. Oikos 1995, 73, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakalos, J.L.; Chelli, S.; Campetella, G.; Canullo, R.; Simonetti, E.; Bartha, S. Comspat: An R package to analyze within-community spatial organization using species combinations. Ecography 2022, 2022, e06216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podani, J. Introduction to the Exploration of Multivariate Biological Data; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2000; p. 407. [Google Scholar]

- Buonaccorsi, J.P.; Elkinton, J.S.; Evans, S.R.; Liebhold, A.M. Measuring and testing for spatial synchrony. Ecology 2001, 82, 1668–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebhold, A.; Koenig, W.D.; Bjornstad, O.N. Spatial synchrony in population dynamics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, S.; Meiners, S.J.; Pickett, S.T.A.; Cadenasso, M.L. Plant colonization windows in a mesic old field succession. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2003, 6, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, S.; Szabó, G.; Csete, S.; Purger, D.; Házi, J.; Csathó, A.I.; Campetella, G.; Canullo, R.; Chelli, S.; Tsakalos, J.L.; et al. High-Resolution Transect Sampling and Multiple Scale Diversity Analyses for Evaluating Grassland Resilience to Climatic Extremes. Land 2022, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, S.; Házi, J.; Purger, D.; Zimmermann, Z.; Szabó, G.; Guller, Z.E.; Csathó, A.I.; Csete, S. Beta Diversity Is Better—Microhabitat Diversity and Multiplet Diversity Offer Novel Insights into Plant Coexistence in Grassland Restoration. Diversity 2024, 16, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, B.F.J. Randomization, Bootstrap and Monte Carlo Methods in Biology, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1997; p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, A.C.; Hinkley, D.V. Bootstrap Methods and Their Application; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; p. 582. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, J.M.; Kraft, N.J.B.; Smith, K.G.; Vellend, M.; Inouye, B.D. Using null models to disentangle variation in community dissimilarity from variation in alpha-diversity. Ecosphere 2011, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, N.J.B.; Comita, L.S.; Chase, J.M.; Sanders, N.J.; Swenson, N.G.; Crist, T.O.; Stegen, J.C.; Vellend, M.; Boyle, B.; Anderson, M.J.; et al. Disentangling the drivers of beta diversity along latitudinal and elevational gradients. Science 2011, 333, 1755–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, N.G.; Anglada-Cordero, P.; Barone, J.A. Deterministic tropical tree community turnover: Evidence from patterns of functional beta diversity along an elevational gradient. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2011, 278, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, S.; Czárán, T.; Podani, J. Exploring plant community dynamics in abstract coenostate spaces. Abstr. Bot. 1998, 22, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Podani, J. SYN-TAXpc. Version 5.0. User’s Guide; Scientia Publishing: Budapest, Hungary, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw, K.A. Pattern in vegetation and its causality. Ecology 1963, 44, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig-Smith, P. Pattern in vegetation. J. Ecol. 1979, 67, 755–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig-Smith, P. Quantitative Plant Ecology, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Sci. Pub.: London, UK, 1983; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, V.K.; Southwood, T.R.E. Secondary succession: Patterns and strategies. In Colonization, Succession and Stability; Gray, A.J., Crawley, M.J., Edwards, P.J., Eds.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK,, 1987; pp. 315–338. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn-Lewin, D.C.; van der Maarel, E. Patterns and processes of vegetation dynamics. In Plant Succession: Theory and Prediction; Glenn-Lewin, D.C., Peet, R.K., Veblen, T.T., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1992; pp. 188–214. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.-p.; Cadotte, M.W.; Meiners, S.J.; Hua, Z.-s.; Jiang, L.; Shu, W.-s. Species colonisation, not competitive exclusion, drives community overdispersion over long-term succession. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCain, K.N.S.; Baer, S.G.; Blair, J.M.; Wilson, G.W.T. Dominant grasses suppress local diversity in restored tallgrass prairie. Restor. Ecol. 2010, 18, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Házi, J.; Bartha, S.; Szentes, S.; Wichmann, B.; Penksza, K. Seminatural grassland management by mowing of Calamagrostis epigejos in Hungary. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 145, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentes, S.; Sutyinszki, Z.; Szabó, G.; Zimmermann, Z.; Házi, J.; Wichmann, B.; Hufnágel, L.; Penksza, K.; Bartha, S. Grazed pannonian grassland beta-diversity changes due to C4 yellow bluestem. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2012, 7, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anibaba, Q.A.; Dyderski, M.K.; Woźniak, G.; Jagodziński, A.M. The inhibitory tendency of Calamagrostis epigejos and Solidago spp. depends on the successional stage in postindustrial vegetation. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2024, 36, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akatov, V.V.; Akatova, T.V.; Eskina, T.G.; Sazonets, N.M.; Chefranov, S.G. Dominants in plant communities: The nature of impact on biomass determines the thresholds of impact on local species richness. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2025, 15, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akatov, V.V.; Akatova, T.V.; Chefranov, S.G. Impact of Solidago canadensis L. on Species Diversity of Plant Communities at Different Spatial Scale. Russ. J. Biol. Invasions 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, B.; Collins, S.L. Multiscale monitoring of a multispecies case study: Two grass species at Sevilleta. Plant Ecol. 2005, 179, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Xia, Y. Long-term dynamics and hotspots of change in a desert grassland plant community. Am. Nat. 2015, 185, E30–E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehmi, J.S.; Bartolome, J.W. A grid-based method for sampling and analysing spatially ambiguous plants. J. Veg. Sci. 2001, 12, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Luque, S.; Pettorelli, N.; Bastin, L.; Doctor, D.; Faedi, N.; Feilhauer, H.; Fére, J.-B.; Foody, G.M.; Gavish, Y.; et al. Measuring β-diversity by remote sensing: A challenge for biodiversity monitoring. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarretta, N.; Harrison, P.; Bailey, T.; Potts, B.; Lucieer, A.; Davidson, N.; Hant, M. Monitoring forest structure to guide adaptive management of forest restoration: A review of remote sensing approaches. New Forests 2020, 51, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, H.; Gamon, J.A.; Helzer, C.J.; Cavender-Bares, J. Multi-temporal assessment of grassland α- and β-diversity using hyperspectral imaging. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herben, T. Permanent plots as tools for plant community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 1996, 7, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.P.; Ollf, H.; Willems, J.H.; Zobel, M. Why we need permanent plots in the study of long-term vegetation dynamics. J. Veg. Sci. 1996, 7, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bello, F.; Valencia, E.; Ward, D.; Hallett, L. Why we still need permanent plots for vegetation science. J. Veg. Sci. 2020, 31, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Glenn, S.M.; Roberts, D.W. The hierarchical continuum concept. J. Veg. Sci. 1993, 4, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Loucks, O.L. From balance of nature to hierarchical patch dynamics: A paradigm shift in ecology. Q. Rev. Biol. 1995, 70, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podani, J. With a machete through the jungle: Some thoughts on community diversity. Acta Biotheor. 2006, 54, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A.; Jiménez-Valverde, A.; Niccolini, G. A multiple-site similarity measure independent of richness. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podani, J.; Schmera, D. A new conceptual and methodological framework for exploring and explaining pattern in presence—Absence data. Oikos 2011, 120, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Condit, R. Spatial and temporal analysis of beta diversity in the Barro Colorado Island forest dynamics plot, Panama. For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roswell, M.; Dushoff, J.; Winfree, R. A conceptual guide to measuring species diversity. Oikos 2021, 130, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.; Milne, B.T. Scaling of ’landscapes’ in landscape ecology, or, landscape ecology from a beetle’s perspective. Land. Ecol. 1989, 3, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, L. Partitioning diversity into independent alpha and beta components. Ecology 2007, 88, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the Turnover and Nestedness Components of Beta Diversity. Global Ecol. Biogeog. 2010, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. The relationship between species replacement, dissimilarity derived from nestedness, and nestedness. Global Ecol. Biogeog. 2012, 21, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, K.P.; Lowe, A.J.; Breed, M.F.; Paton, D.C. Spatially designed revegetation—Why the spatial arrangement of plants should be as important to revegetation as they are to natural systems. Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, A.S. Pattern and Process in the Plant Community. J. Ecol. 1947, 35, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G. Landscape Ecology: The Effect of Pattern on Process. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1989, 20, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G.; Gardner, R.H.; O’Neill, R.V. Landscape Ecology in Theory and Practice: Pattern and Process; Springer: New York, NY, US, 1999; p. 482. [Google Scholar]

- Aarssen, L.W. Competitive ability and species coexistence: A ‘plant’s eye’ view. Oikos 1989, 56, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purves, D.W.; Law, R. Fine-scale spatial structure in a grassland community: Quantifying the plant’s-eye view. J. Ecol. 2002, 90, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, A.J.; Stephens, K.A.; Schamp, B.S.; Aarssen, L.W. What does body size mean, from the “plant’s eye view”? Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 7344–7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvertown, J.; Holtier, S.; Johnson, J.; Dale, P. Cellular automaton models of interspecific comperition for space—The effect of pattern on process. J. Ecol. 1992, 80, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. Competition and biodiversity in spatially structured habitats. Ecology 1994, 75, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrett, R.; Levin, S. Spatial aspects of interspecific competition. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1998, 53, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolker, B.M.; Pacala, S.W. Spatial moment equations for plant competition: Understanding spatial strategies and the advantages of short dispersal. Am. Nat. 1999, 153, 575–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, D.J.; Purves, D.W.; Law, R. Uniting pattern and process in plant ecology. Tree 2001, 16, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneitel, J.M.; Chase, J.M. Trade-offs in community ecology: Linking spatial scales and species coexistence. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 7, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herben, T.; During, H.J.; Krahulec, F. Spatiotemporal dynamics in mountain grasslands: Species autocorrelations in space and time. In Species Coexistence in Temperate Grasslands; Krahulec, F., Goldberg, D.E., Willems, J.H., Eds.; Opulus Press: Uppsala, Sweden, 1995; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Silvertown, J.; Wilson, J.B. Spatial interactions among grassland plant populations. In The Geometry of Ecological Interactions: Simplifying Spatial Complexity; Dieckman, U., Law, R., Metz, J.A.J., Eds.; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 28–47. [Google Scholar]